Chapter 63 NURSING MANAGEMENT: musculoskeletal problems

1. Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, multidisciplinary care and nursing management of osteomyelitis.

2. Describe the types, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and multidisciplinary care of bone cancer.

3. Differentiate between the causes and characteristics of acute and chronic low back pain.

4. Describe the conservative and surgical therapy of intervertebral disc damage.

5. Describe the postoperative nursing management of a patient who has undergone spinal surgery.

6. Explain the aetiology and nursing management of common foot disorders.

7. Describe the aetiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and collaborative and nursing management of osteomalacia, osteoporosis and Paget’s disease.

Osteomyelitis

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Osteomyelitis is a severe infection of the bone, bone marrow and surrounding soft tissue. The most common infecting microorganism is Staphylococcus aureus. A variety of microorganisms can cause osteomyelitis (see Table 63-1);1 these can either be aerobic Gram-negative bacteria alone or present with Gram-positive organisms as well. The widespread use of antibiotics in conjunction with surgical treatment has significantly reduced the mortality rate and complications associated with osteomyelitis.

TABLE 63-1 Causative organisms in osteomyelitis

| Organism | Possible predisposing problem |

|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | Pressure ulcer, penetrating wound, open fracture, orthopaedic surgery, vascular insufficiency disorders (e.g. diabetes, atherosclerosis) |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Indwelling prosthetic devices (e.g. joint replacements, fracture fixation devices) |

| Streptococcus viridans | Abscessed tooth, gingival disease |

| Escherichia coli | Urinary tract infection |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Tuberculosis |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Gonorrhoea |

| Pseudomonas | Puncture wounds, intravenous drug use |

| Salmonella | Sickle cell disease |

| Fungi, mycobacteria | Immunocompromised host |

The infecting microorganisms can invade by indirect or direct entry. The indirect entry (haematogenous) of microorganisms in osteomyelitis most frequently affects growing bone in boys less than 12 years old and is associated with their higher incidence of blunt trauma. The most common sites of indirect entry in children are the distal femur, proximal tibia, humerus and radius.2 Adults with vascular insufficiency disorders (e.g. diabetes mellitus) and genitourinary and respiratory infections are at higher risk of a primary infection to spread via the blood to the bone. The pelvis, tibia and vertebrae—the vascular-rich sites of bone—are the most common sites of infection.

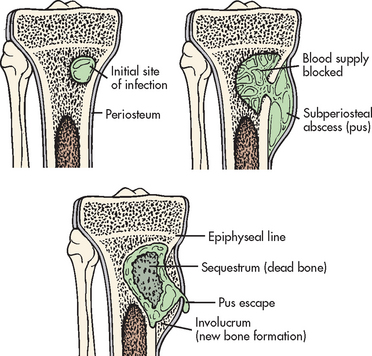

Direct entry osteomyelitis can occur at any age when there is an open wound (e.g. penetrating wounds, fractures) and microorganisms gain entry to the body. Osteomyelitis may also occur in the presence of a foreign body such as an implant or an orthopaedic prosthetic device (e.g. plate, total joint prosthesis). After gaining entrance to the bone by way of the blood, the microorganisms then lodge in an area of bone in which circulation slows, usually the metaphysis. The microorganisms grow, resulting in an increase in pressure because of the non-expanding nature of most bone. This increasing pressure ultimately leads to ischaemia and vascular compromise of the periosteum. Eventually the infection passes through the bone cortex and marrow cavity and results in cortical devascularisation and necrosis. Once ischaemia occurs, the bone dies. The area of devitalised bone eventually separates from the surrounding living bone, forming sequestrum. The part of the periosteum that continues to have a blood supply forms new bone called involucrum (see Fig 63-1).

Once formed, a sequestrum continues to be an infected island of bone, surrounded by pus and difficult to reach by blood-borne antibiotics or white blood cells (WBCs). The sequestrum may enlarge and serve as a site for microorganisms that spread to other sites, including the lungs and brain. It can also move out of the bone and into the soft tissue. Once outside the bone, the sequestrum may revascularise and then undergo removal by normal immune processes. Another possibility is that the sequestrum can be surgically removed through debridement of the necrotic bone. If the necrotic sequestrum is not resolved naturally or surgically, it may develop a sinus tract, resulting in a chronic, purulent cutaneous drainage.

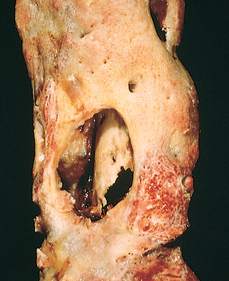

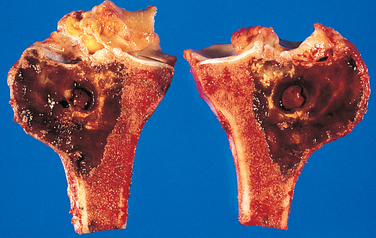

Chronic osteomyelitis is either a continuous, persistent problem (a result of inadequate acute treatment) or a process of exacerbations and remission (see Fig 63-2). Over time, granulation tissue turns to scar tissue. This avascular scar tissue provides an ideal site for continued microorganism growth and is impenetrable to antibiotics.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Acute osteomyelitis refers to the initial infection or an infection of less than 1 month in duration. The clinical manifestations of acute osteomyelitis are both systemic and local. Systemic manifestations include fever, night sweats, chills, restlessness, nausea and malaise. Local manifestations include constant bone pain that is unrelieved by rest and worsens with activity; swelling, tenderness and warmth at the infection site; and restricted movement of the affected part. Later signs include drainage from sinus tracts to the skin and/or the fracture site.

Chronic osteomyelitis refers to a bone infection that persists for longer than 1 month or an infection that has failed to respond to the initial course of antibiotic therapy. Systemic signs may be diminished, with local signs of infection more common, including constant bone pain and swelling, tenderness and warmth at the infection site.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A bone or soft-tissue biopsy is the definitive way to determine the causative microorganism. The patient’s blood and/or wound cultures are frequently positive for the presence of microorganisms. An elevated WBC and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may also be found. Radiological signs suggestive of osteomyelitis usually do not appear until 10 days to weeks after the appearance of clinical symptoms, by which time the disease will have progressed. Radionuclide bone scans (gallium and indium) are helpful in diagnosis and are usually positive in the area of infection. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans may be used to help identify the extent of the infection, including soft-tissue involvement.3

Multidisciplinary care

Vigorous and prolonged intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy is the treatment of choice for acute osteomyelitis, as long as bone ischaemia has not yet occurred. Cultures or a bone biopsy should be done if possible before drug therapy is initiated. If antibiotic therapy is delayed, surgical debridement and decompression are often necessary.

Treatment for osteomyelitis previously involved an extended hospital stay for IV antibiotic treatment. Today, patients are often discharged to ‘hospital-in-the-home’ under the care of skilled nurses, with IV antibiotics delivered via a central venous catheter or a peripherally inserted central catheter. IV antibiotic therapy may initially be started in the hospital and continued at home for 4–6 weeks or as long as 3–6 months. A variety of antibiotics may be prescribed depending on the microorganism.4 These drugs include penicillin, neomycin, vancomycin, cephalexin, cefazolin, cefoxitin, gentamicin and tobramycin.

In adults with chronic osteomyelitis, oral therapy with a fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin) for 6–8 weeks may be prescribed instead of IV antibiotics. Oral antibiotic therapy may also be given after acute IV therapy is complete to ensure resolution of the infection. The patient’s response to drug therapy is monitored through bone scans and ESR tests.

Surgical treatment for chronic osteomyelitis includes removal of the poorly vascularised tissue and dead bone and the extended use of antibiotics. Antibiotic-impregnated polymethylmethacrylate bead chains may be implanted to aid in combating the infection.5 After debridement of the devitalised and infected tissue, the wound may be closed and a suction irrigation system inserted. Intermittent or constant irrigation of the affected bone with antibiotics may also be initiated. Protection of the limb or surgical site with casts or braces is frequently done. Negative pressure (Wound Vac) over the site of the infection may be used to draw the wound together (see Ch 12).

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy of 100% oxygen may be administered as an adjunct therapy in refractory cases of chronic osteomyelitis. This therapy is thought to stimulate circulation and healing in the infected tissue (see Ch 12). Orthopaedic prosthetic devices, if a source of chronic infection, must be removed. Muscle flaps or skin grafting provide wound coverage over the dead space (cavity) in the bone. Bone grafts may help to restore blood flow. Amputation of the extremity may be indicated when there is extensive bone destruction and it is necessary to preserve the person’s life and/or improve quality of life.

Long-term and mostly rare complications of osteomyelitis include septicaemia, septic arthritis, pathological fractures and amyloidosis.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: OSTEOMYELITIS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: OSTEOMYELITIS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

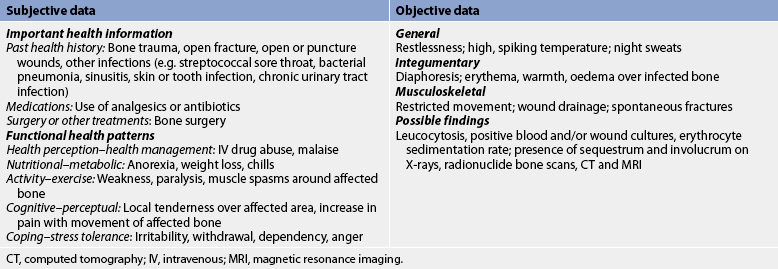

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from an individual with osteomyelitis are presented in Table 63-2.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

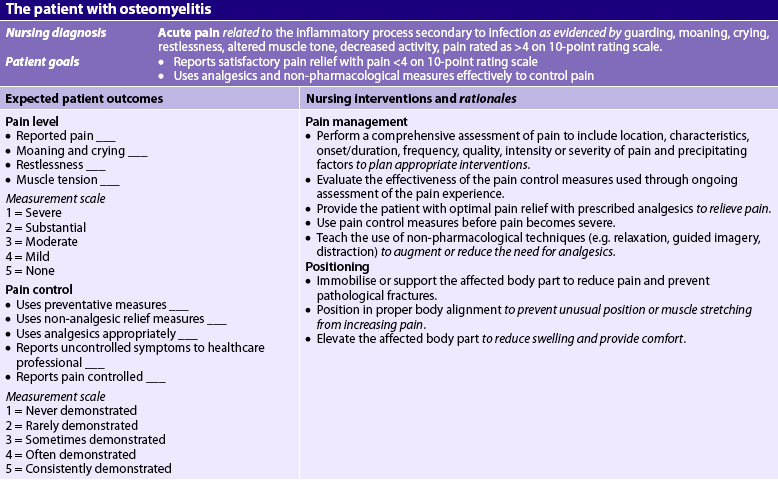

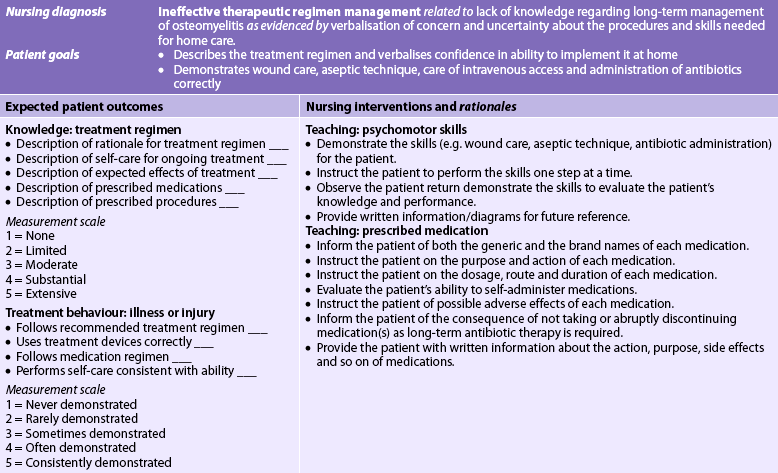

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with osteomyelitis may include, but are not limited to, those presented in NCP 63-1.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with osteomyelitis will: (1) have satisfactory pain and fever control; (2) not experience any complications associated with osteomyelitis; (3) cooperate with the treatment plan; and (4) maintain a positive outlook on the outcome of the disease.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

The control of infections already in the body (e.g. urinary tract, respiratory tract) is important in preventing osteomyelitis. Adults who are immunocompromised, have orthopaedic prosthetic devices and/or have vascular insufficiencies are especially susceptible. These patients should be instructed regarding the local and systemic manifestations of osteomyelitis. Families should also be aware of their role in monitoring the patient’s health. Symptoms of bone pain, fever, swelling and restricted limb movement should be reported immediately to the healthcare provider.

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

Some immobilisation of the affected limb (e.g. splint, traction) is usually indicated to decrease pain. The involved limb should be handled carefully to avoid excessive manipulation, which increases pain and may cause pathological fracture. An important nursing responsibility is to assess the patient’s pain. Minor-to-severe pain may be experienced with muscle spasms. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioid analgesics and muscle relaxants may be prescribed to provide patient comfort. Non-pharmacological approaches to pain relief (e.g. guided imagery, hypnosis) may also be encouraged.

Dressings are used to absorb the exudate from draining wounds and to debride devitalised tissue from the wound site when removed. Types of dressings used include dry, sterile dressings; dressings saturated in saline or antibiotic solution; and wet-to-dry dressings. Soiled dressings should be handled carefully to prevent cross-contamination of the wound or spread of the infection to other patients. When the dressing is changed, sterile technique is essential.

The patient is frequently on bed rest in the early stages of the acute infection.6 Good body alignment and frequent position changes prevent complications associated with immobility and promote comfort. Flexion contracture, especially of the hip or knee, is a common sequela of osteomyelitis of the lower extremity because the patient frequently positions the affected extremity in a flexed position to promote comfort. The contracture may then progress to a deformity. Footdrop can develop quickly in the lower extremity if the foot is not correctly supported in a neutral position by a splint or if there is excessive pressure from a splint, which can injure the peroneal nerve. The patient should be instructed to avoid any activities that increase circulation and swelling and serve as stimuli to the spread of infection, such as exercise or heat application. Uninvolved joints and muscles should continue to be exercised.

The patient should also be taught the potential adverse and toxic reactions associated with prolonged and high-dose antibiotic therapy. These reactions include hearing deficit, fluid retention and neurotoxicity, which can occur with the aminoglycosides (e.g. tobramycin, neomycin), and jaundice, colitis and photosensitivity from the extended use of the cephalosporins (e.g. cefazolin). Peak and trough blood levels of most antibiotics must be carefully monitored throughout the course of therapy to avoid these adverse effects. Lengthy antibiotic therapy can also result in an overgrowth of Candida albicans in the genitourinary and oral cavities, especially in immunosuppressed and older patients. The nurse should instruct the patient to report any whitish, yellow, curd-like lesions to the healthcare provider.

The patient and family are often frightened and discouraged because of the serious nature of the disease, the uncertainty of the outcome and the lengthy course of treatment. Continued psychological and emotional support is an integral part of nursing management.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

With the introduction of various intermittent venous access devices, IV antibiotics can be administered to the patient in a specialty nursing facility or home setting. If at home, the patient and family must be instructed on the proper care and management of the venous access device. They must also be taught how to administer the antibiotic when scheduled and the need for follow-up laboratory testing. The importance of continuing to take antibiotics after the symptoms have subsided should be stressed. Periodic home nursing visits from the community nurse provide the family with support, which helps to reduce anxiety. If there is an open wound, dressing changes are often necessary. The patient and family may require supplies and instruction in the technique. Family members also need to understand that the infection is not contagious.

If the osteomyelitis becomes chronic, patients need physical and psychological support for a prolonged period. They may become suspicious and angry towards healthcare providers when treatment plans do not result in a cure. Well-informed patients are better able to participate in decisions and cooperate in treatment plans.

Bone tumours

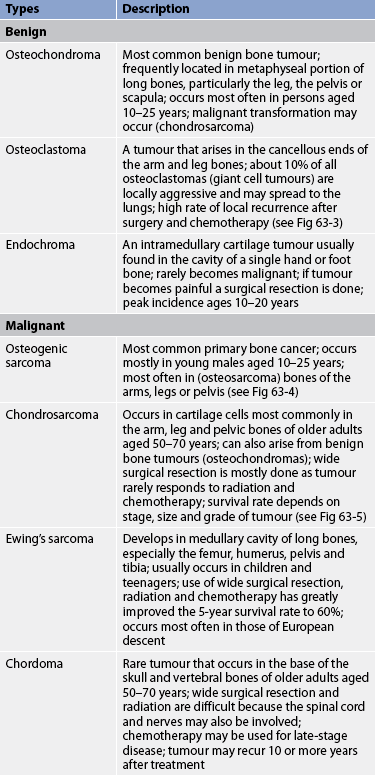

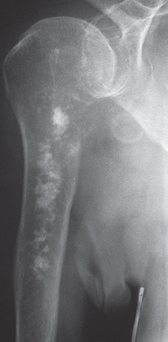

Primary bone tumours, both benign and malignant, are relatively rare in adults. Metastatic bone cancer in which the cancer has spread from another site is a more common problem. The name given to the tumour is based on the area of bone and surrounding tissue that is affected and from the type of cells forming the tumour. The main types of benign tumours include osteochondroma, osteoclastoma (see Fig 63-3) and endochroma (see Table 63-3). These types of tumours are often cured by surgery and are more common than primary malignant tumours.

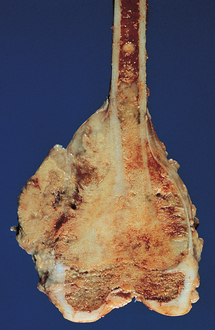

Primary bone cancer is called sarcoma. Sarcomas can also develop in cartilage, muscle fibres, fatty tissue and nerve tissue.7 The more common types of bone cancer are osteogenic sarcoma (see Fig 63-4), chondrosarcoma (see Fig 63-5), Ewing’s sarcoma and chordoma (see Table 63-3). While sarcoma is still relatively rare, in Australia the projection for cancers of bone and connective tissue show increasing rates for women (especially in the older age groups) and for men. The number of new cases for women is projected to increase 50% from 427 in 2001 to 639 in 2011 and new cases for men are projected to increase 32% from 401 in 2001 to 529 in 2011.8 Primary malignant tumours occur most often during childhood through to young adulthood. They are characterised by their rapid metastasis and bone destruction.

OSTEOCHONDROMA

Osteochondroma is a primary benign bone tumour that is characterised by an overgrowth of cartilage and bone near the end of the bone at the growth plate. Osteochondromas can occur in any bone where cartilage assists in forming bone. It is more commonly found in the long bones of the leg, pelvis or scapula. One form of the disease is hereditary, with multiple tumours forming before age 10.

Clinical manifestations include a painless, hard and immobile mass, lower-than-normal-height for age, soreness of muscles in close proximity to the tumour, one leg or arm longer than the other and pressure or irritation with exercise. Patients may also have no symptoms. Diagnosis is confirmed from X-ray, CT scan and MRI.

No treatment is necessary for asymptomatic osteochondroma. If the tumour is causing pain or neurological symptoms due to compression, surgical resection is usually done. As long as the entire cartilage cap is removed, the tumour should not recur. Patients with many large osteochondromas should have regular screening examinations to detect early malignant transformation.

OSTEOGENIC SARCOMA

Osteogenic sarcoma (osteosarcoma) is a primary bone tumour that is extremely aggressive and rapidly metastasises to distant sites. It usually occurs in the metaphyseal region of the long bones of the extremities, particularly in the regions of the distal femur, proximal tibia and proximal humerus, as well as the pelvis (see Fig 63-4). Osteogenic sarcoma is the most common malignant bone tumour affecting children and young adults; the highest incidence is in males in the 10–25-year-old age group. Secondary osteosarcoma is known to occur in adults over age 60 and is most commonly associated with Paget’s disease.9

Clinical manifestations of osteogenic sarcoma are usually associated with the gradual onset of pain and swelling, especially around the knee. A minor injury does not cause the neoplasm but may bring the pre-existing condition to medical attention. The neoplasm can restrict joint motion if the tumour is close to a joint structure. The diagnosis is confirmed by tissue biopsy, elevation of serum alkaline phosphatase and calcium levels and findings on X-ray, CT or positron emission tomogram (PET) scans and MRI. Metastasis is present in 10–20% of individuals on diagnosis, with the lung being the most frequent site.

Major advances continue to be made in the treatment of osteogenic sarcoma. Preoperative chemotherapy is used to decrease tumour size. As a result, limb-salvage procedures, including a wide surgical resection of the tumour, are being used more often. Limb-salvage procedures are considered when there is a clear 6–7 cm margin surrounding the lesion. Limb salvage is contraindicated if there is major neurovascular involvement, pathological fracture, infection, skeletal immaturity or extensive muscle involvement.10 Quality-of-life considerations are also factors in the decision of limb salvage compared with amputation. Current use of adjunct chemotherapy following amputation has increased the projected 5-year survival rate to 60%,11 and a 55–77% survival rate has been reported with combined intraarterial and intravenous agents.12 Chemotherapeutic agents include methotrexate, doxorubicin, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, bleomycin, dactinomycin and ifosfamide.

METASTATIC BONE CANCER

The most common type of malignant bone tumour occurs as a result of metastasis from a primary tumour. Common sites for the primary tumour include the breast, prostate, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, lungs, kidneys, ovaries and thyroid.13 Metastatic cancer cells travel to other sites from the primary tumour to the bone via the lymph and blood supply. The metastatic bone lesion is commonly found in the vertebrae, pelvis, femur, humerus or ribs. Pathological fractures at the site of metastasis are common because of a weakening of the involved bone. High serum calcium levels result as calcium is released from damaged bones.

Once a primary lesion has been identified, radionuclide bone scans are often done to detect the presence of metastatic lesions before they are visible on X-ray. It is important to note that metastatic bone lesions may occur at any time (even years later) following diagnosis and treatment of the primary tumour. Metastasis to the bone should be suspected in any patient who has local bone pain and a past history of cancer. Treatment may be palliative and consist of radiation and pain management (see Ch 9). Surgical stabilisation of the fracture may be indicated if there is a fracture or pending fracture. Prognosis depends on the extent of metastasis and the location.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: BONE CANCER

NURSING MANAGEMENT: BONE CANCER

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

The patient with bone cancer should be assessed for the location and severity of pain. Weakness caused by anaemia and decreased mobility may also be noted. Swelling at the involved site and decreased joint function, depending on the tumour site, should also be monitored.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with bone cancer may include, but are not limited to, the following:

• acute pain related to the disease process or inadequate pain medication or comfort measures

• impaired physical mobility related to the disease process, pain, weakness and debility

• disturbed body image related to possible amputation, deformity, swelling and effects of chemotherapy

• anticipatory grieving related to poor prognosis of the disease

• risk of injury related to the disease process, possible pathological fracture or inadequate handling or positioning of affected body part.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with bone cancer will: (1) have satisfactory pain relief; (2) maintain preferred activities as long as possible; (3) demonstrate acceptance of body image changes resulting from chemotherapy, radiation and surgery; (4) be free from injury; and (5) verbalise a realistic idea of disease progression and prognosis.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

Nurses should teach the public to recognise the warning signs of bone cancer, including swelling, bone pain of unexplained origin, limitation of joint function and changes in skin temperature. As with all forms of cancer, health promotion should stress the importance of periodic screening and health examinations.14,15

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

Nursing care of the patient with a malignant bone neoplasm does not differ significantly from the care given to the patient with a malignant disease of any other body system (see Ch 15). However, special attention is required to reduce the complications associated with prolonged bed rest and to prevent falls and pathological fractures. Careful handling and support of the affected extremity and logrolling for those on bed rest is important to prevent pathological fractures.16 The patient is often reluctant to participate in therapeutic activities because of weakness from the disease and treatment and fear of pain. Regular rest periods should be provided between activities.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

The nurse must be able to assist the patient and family in accepting the guarded prognosis associated with bone neoplasms. Inability to accomplish age-specific developmental tasks can increase the frustrations with this condition. General principles related to cancer nursing are applicable (see Ch 15). Special attention is necessary for the problems of pain and disability, chemotherapy and specific surgery such as spinal cord decompression or amputation.

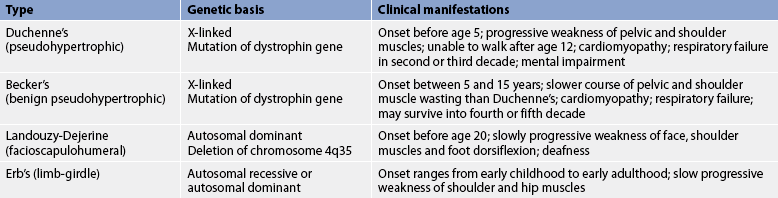

Muscular dystrophy

Muscular dystrophy (MD) is a group of genetically transmitted diseases characterised by progressive symmetrical wasting of skeletal muscle without evidence of neurological involvement. In all forms of MD an insidious loss of strength occurs with increasing disability and deformity. The types of MD differ in the groups of muscles affected, age of onset, rate of progression and mode of genetic inheritance.17 Types of MD are presented in Table 63-4.

Duchenne’s MD and Becker’s MD are sex-linked recessive disorders usually seen only in males. In these disorders there is a genetic mutation of the dystrophin gene. Dystrophin in normal muscle cells helps to attach skeletal muscle fibres to the basement membrane. Abnormalities in dystrophin can lead to defects in the plasma membrane of muscle fibre with subsequent muscle fibre degeneration.

HEALTH DISPARITIES

Clinical implications

• Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy is present at birth but does not usually become clinically apparent until at least age 3.

• Very few individuals with the disease live to adulthood.

• Genetic testing and counselling should be considered in individuals with a family history of Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy.

• Because there are many types of muscular dystrophy with different genetic bases, establishing the type of muscular dystrophy is important to determine treatment and possible genetic counselling recommendations.

Diagnostic studies for MD include muscle serum enzymes (especially creatine kinase), electromyogram (EMG) testing, muscle fibre biopsy, electrocardiogram abnormalities reflective of cardiomyopathy and genetic pedigree (see Ch 13). Muscle biopsy confirms the diagnosis with classic findings of fat and connective tissue deposits, degeneration and necrosis of muscle fibres, and a deficiency of the muscle protein dystrophin.

Presently, no definitive therapy is available to stop the progressive wasting of MD. Corticosteroid therapy may significantly halt the disease progression for up to 3 years.18,19 The goal of treatment is to preserve mobility and independence through exercise, physiotherapy and orthopaedic appliances. The nurse should encourage communication among all family members to cope with the emotional and physical strains of MD.20 An emphasis should be placed on teaching the patient and family range-of-motion exercises, nutrition and signs of progression. Genetic testing and counselling may be recommended for individuals with a family history of MD.

Nursing care should focus on keeping the patient active for as long as possible. Prolonged bed rest should be avoided because immobility can lead to further muscle wasting. As the disease progresses, the focus will shift to teaching the patient to limit sedentary periods when skin integrity or respiratory complications could develop. Ongoing medical and nursing care will be required throughout the individual’s lifetime.

LOW BACK PAIN

Disability from low back pain is a growing public health problem in New Zealand, Australia and other developed countries and is one health issue targeted by the World Health Organization (WHO) in its Bone Joint Decade, 2000–2010.21 Although episodes of acute back pain are mostly short-lived, back complaints still constitute the second most common reason (after upper respiratory tract complaints) for visits to the general practitioner. Furthermore, disability from back pain places a significant socioeconomic burden on the individual and the community as it is the leading specific musculoskeletal cause of health system expenditure in Australia and New Zealand.22

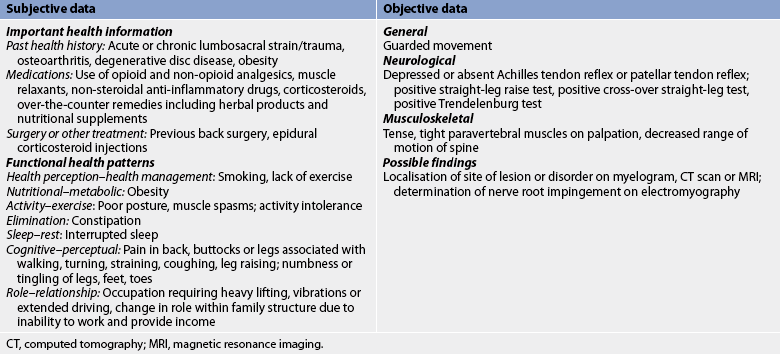

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Low back pain is a common problem because the lumbar region: (1) bears most of the weight of the body; (2) is the most flexible region of the spinal column; (3) contains nerve roots that are vulnerable to injury or disease; and (4) has an inherently poor biomechanical structure. Several risk factors are associated with low back pain, including lack of muscle tone and excess body weight, poor posture, cigarette smoking and stress. Jobs that require repetitive heavy lifting, vibration (such as a jackhammer operator) and prolonged periods of sitting are also associated with low back pain. Low back pain is most often due to a musculoskeletal problem. The causes of low back pain of musculoskeletal origin include: (1) acute lumbosacral strain; (2) instability of lumbosacral bony mechanism; (3) osteoarthritis of the lumbosacral vertebrae; (4) degenerative disc disease; and (5) herniation of the intervertebral disc.

Acute low back pain

Acute low back pain lasts 4 weeks or less. Acute low back pain is usually associated with some type of activity that causes undue stress (often hyperflexion) on the tissues of the lower back. Often the symptoms do not appear at the time of injury but develop later because of a gradual increase in paravertebral muscle spasms. Few definitive diagnostic abnormalities are present with paravertebral muscle strain. One test is the straight-leg raise. This test is positive for disc herniation when radicular pain occurs. MRI and CT scans are generally not carried out unless trauma or systemic disease (e.g. cancer, spinal infection) is suspected.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

If the acute muscle spasms and accompanying pain are not severe and debilitating, the patient may be treated as an outpatient with a combination of the following: (1) analgesics, such as NSAIDs;23 (2) muscle relaxants (e.g. diazepam); (3) massage and back manipulation; and (4) the alternating use of heat and cold compresses.24 Severe pain may require a brief course of opioid analgesics.25

A brief period (1–2 days) of rest at home may be necessary for some people, with most patients doing better with a continuation of their regular activities.26 The effectiveness of invasive treatments, such as epidural corticosteroid injections and implanted devices that deliver pain medication, are reserved for patients with chronic back pain who are refractory to the usual therapeutic options.27 During this time, all patients should avoid activities that aggravate the pain, including lifting, bending, twisting and prolonged sitting. Most cases improve within 2 weeks.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ACUTE LOW BACK PAIN

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ACUTE LOW BACK PAIN

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from the patient with low back pain are summarised in Table 63-5.

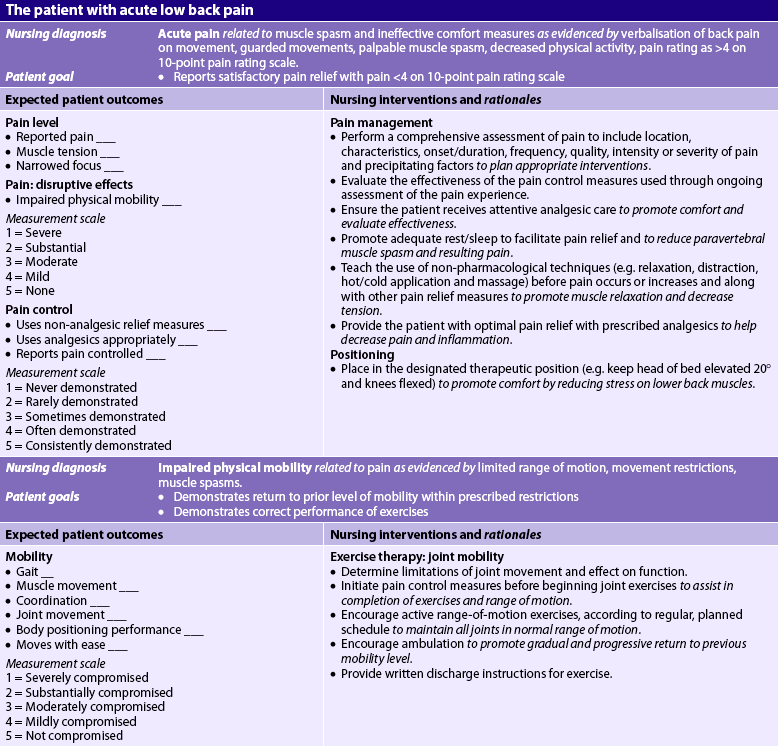

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with acute low back pain may include, but are not limited to, those presented in NCP 63-2.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with acute low back pain will: (1) have satisfactory pain relief; (2) avoid constipation secondary to medication and immobility; (3) learn back-sparing practices; and (4) return to the previous level of activity within prescribed restrictions.

HEALTH PROMOTION

• Do not sleep in a prone position.

• Sleep on side with knees flexed and a pillow between the knees.

• Avoid cigarette smoking and tobacco products.

• Obtain regular physical activity, including strength and endurance training.

• Use proper body mechanics to avoid low back strain (e.g. when lifting heavy objects, bend at the knees, not at the waist, and stand up slowly while holding object close to your body).

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

The nurse is a significant role model and teacher for patients with low back problems. As a role model, the nurse should use proper body mechanics at all times. This should be a primary consideration when teaching patients and healthcare providers transfer and turning techniques. The nurse should assess the patient’s use of body mechanics and offer advice when activities that could produce back strain are used (see Box 63-1).

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

Do not

• Lean forward without bending knees

• Lift anything above level of elbows

• Stand in one position for a prolonged period of time

• Sleep on abdomen or on back or side with legs out straight

• Exercise without consulting healthcare provider if having severe pain

• Exceed prescribed amount and type of exercises without consulting healthcare provider

Do

• Prevent lower back from straining forward by placing a foot on a step or stool during prolonged standing

• Sleep in a side-lying position with knees and hips bent

• Sleep on back with a lift under knees and legs or on back with 30-cm high pillow under knees to flex hips and knees

• Exercise 15 min in the morning and in the evening regularly; begin exercises with a 2- or 3-min warm-up period by moving arms and legs, by alternately relaxing and tightening muscles; exercise slowly with smooth movements

• Maintain appropriate body weight

Some healthcare providers refer patients with back pain to outpatient programs where appropriate educational and preventative back care programs are provided. These programs are designed to teach patients how to minimise back pain and avoid repeat episodes of low back pain. Tips for prevention of back injury are listed in Box 63-1. Exercises to strengthen the back are presented in Box 63-2.

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

Simple leg lift

Elbow props (to extend lower back)

• Lie face down with your arms beside your body and your head turned to one side.

• Stay in this position for 2–5 minutes, making sure that you relax completely.

• Remain face down and prop yourself on your elbows.

• Hold this position for 2–3 minutes.

Source: Canobbio MM. Mosby’s handbook of patient teaching. 3rd edn. St Louis: Mosby; 2006.

Patients are also advised to maintain appropriate body weight. Excess body weight places extra stress on the lower back and weakens the abdominal muscles that support the lower back. Flat shoes and/or shoes with low heels and shock-absorbing shoe inserts are recommended for women.

The position assumed while sleeping is also important in preventing low back pain. Sleeping in a prone position should be avoided because it produces excessive lumbar lordosis, placing excessive stress on the lower back. A firm mattress is recommended. The patient should sleep in a supine or side-lying position with the knees and hips flexed to prevent unnecessary pressure on support muscles, ligamentous structures and lumbosacral joints. Patients should be educated about the necessity to avoid or cease smoking. Nicotine has been shown to decrease circulation to the vertebral discs and a causal relationship exists between smoking and some types of low back pain.

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

The primary nursing responsibilities in acute low back pain are to assist the patient to maintain activity limitations, promote comfort and educate the patient about the health problem and appropriate exercises. Other nursing interventions are summarised in NCP 63-2. The use of analgesics, NSAIDs, muscle relaxants and thermotherapy (ice and heat) while avoiding continued bed rest is incorporated into the plan of care.

Muscle stretching and strengthening exercises may be part of the management plan. Although the actual exercises are generally taught by the physiotherapist, it is the nurse’s responsibility to ensure that the patient understands the type and frequency of exercise prescribed, as well as the rationale for the program.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

The goal of management is to make an episode of acute low back pain an isolated incident. If the lumbosacral mechanism is unstable, repeated episodes can be anticipated. The lumbosacral spine may be unable to meet the demands placed on it without strain because of factors such as obesity, poor posture, poor muscular support, advancing age or local trauma. Intervention is aimed at strengthening the supporting muscles by exercise. The use of a corset limits extremes of movement and may increase the risk of back pain if used for prolonged periods.28

Persistent use of poor body mechanics may also result in repeated episodes of low back pain. If the strain is work related, occupational counselling may be necessary. The frustration, pain and disability imposed on the patient with low back pain require emotional support and understanding care by the nurse.

Evaluation

Evaluation

The expected outcomes for the patient with acute low back pain are presented in NCP 63-2.

COMPLEMENTARY & ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Acupuncture is a traditional Chinese medicine practice of inserting very fine needles into the skin to stimulate specific anatomical points in the body (called acupoints) for therapeutic purposes. Acupuncture is used to regulate the flow of Qi (life force or energy). The acupuncture needles unblock the obstruction of Qi through the meridians (see Ch 7).

Clinical uses

• Postoperative and chemotherapy-associated nausea and vomiting

• Addiction, asthma, menstrual cramps, menopausal symptoms and stroke rehabilitation

Box 7-1 lists other conditions that may benefit from acupuncture.

Chronic low back pain

Chronic low back pain lasts more than 3 months or occurs as repeated incapacitating episodes. The causes of chronic low back pain include degenerative disc disease, lack of physical exercise, prior injury, obesity, structural and postural abnormalities, and systemic disease. Osteoarthritis of the lumbar spine is found in patients over 50, whereas in younger patients with osteoarthritis chronic back pain usually involves the thoracic or lumbar spine. Periods of inactivity, particularly on awakening or after long periods of sitting, increase the discomfort.

Spinal stenosis is a narrowing of the vertebral canal or nerve root canals caused by encroachment of bone on the space. The stenosis may be congenital or more typically it is acquired through degenerative or traumatic changes to the spine. When it occurs in the lumbar area of the spine, it is a common cause of chronic or recurrent low back pain. Compression of the nerve roots can result with subsequent disc herniation. The pain associated with lumbar spinal stenosis often starts in the low back and then radiates to the buttock and leg.29 It worsens with walking and, in particular, standing without walking.

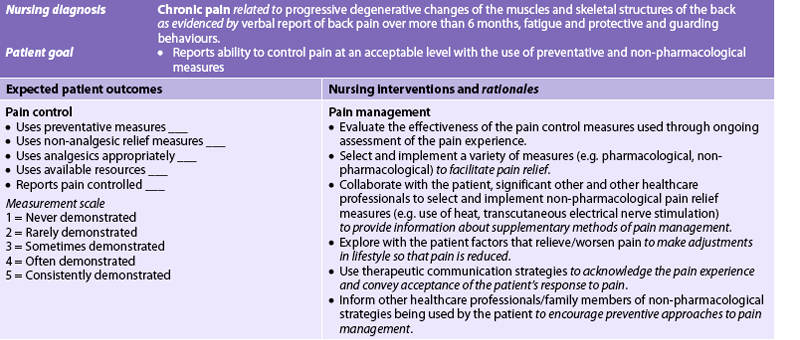

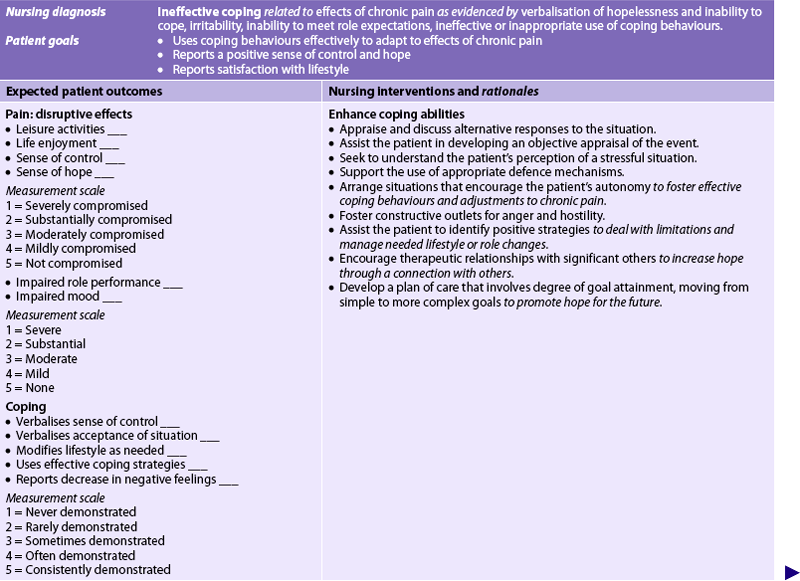

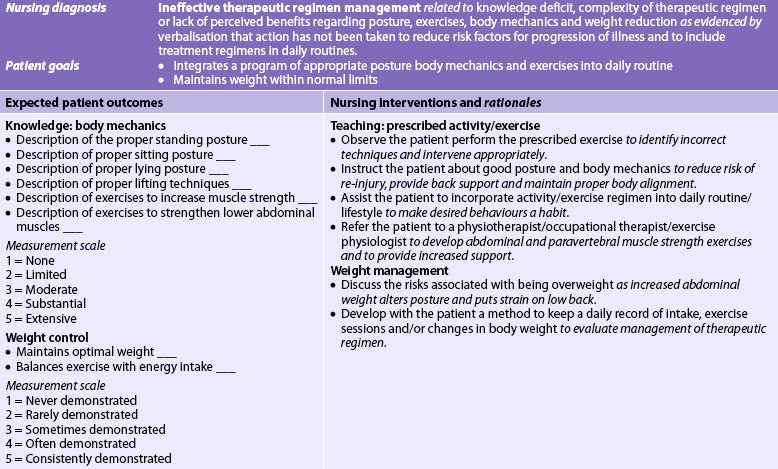

Treatment regimens for chronic back pain are much the same as for acute low back pain, except that patients with chronic pain may be referred to a pain clinic if one is available nearby (see NCP 63-3, which describes the nursing management of chronic pain). Pain clinics provide a multidisciplinary approach to the assessment and treatment of chronic low back pain. The goals of treatment include a reduction in the pain associated with daily activities, a formal back pain program and ongoing multidisciplinary care. Cold, damp weather aggravates the back pain but can be relieved with rest and local heat application. Relief of pain and stiffness by the use of mild analgesics, such as NSAIDs, is integral to the daily comfort of the individual with chronic low back pain. Weight reduction, sufficient rest periods, local heat or cold application and exercise and activity throughout the day help to keep the muscles and joints mobilised. Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g. sertraline) have been shown to improve the symptoms of chronic low back pain.30

What complementary therapies are used for back pain?

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Clinical question

Do ambulatory patients with back pain (P) use complementary and alternative therapies (I) in addition to conventional medical care for managing back pain (O)?

Critical appraisal and synthesis of evidence

• 103 studies of patients with back pain.

• Chiropractic manipulation is the most frequently used therapy, followed by massage and acupuncture.

• Therapy use was reported least often for thoracic spine pain and most often for lower back pain.

• Massage use was similar in frequency for patients with neck pain and lower back pain.

P, patient population of interest; I, intervention or area of interest; O, outcome(s) of interest.

Surgical intervention may be indicated in patients with severe chronic low back pain who do not respond to conservative care and/or who have continued neurological deficits. (Surgery for low back pain is discussed on p 1803.)

Intervertebral lumbar disc damage

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

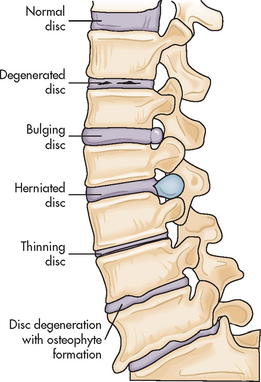

An intervertebral disc is interposed between the vertebrae from the cervical axis to the sacrum. Structural degeneration of the lumbar disc is often caused by degenerative disc disease (DDD) (see Fig 63-6). This progressive degeneration is a normal process of ageing and results in the intervertebral discs losing their elasticity, flexibility and shock-absorbing capabilities. Thinning of the discs occurs as the nucleus pulpous (gelatinous centre of the disc) starts to dry out and shrink.31 Most people by the age of 60 have some degree of DDD. Compression of the nerve roots and cord may then occur. Damage to the spine by DDD contributes to osteoarthritis of the spine by the formation of osteophytes (bone spurs).

An acute herniated intervertebral disc (slipped disc) can be the result of natural degeneration with age or repeated stress and trauma to the spine. The nucleus pulposus may first bulge and then it can herniate, placing pressure on nearby nerves. The most common sites of rupture are the lumbosacral discs, specifically L4–5 and L5–S1. Disc herniation may also occur at C5–6 and C6–7. Disc herniation may be the result of spinal stenosis, in which narrowing of the spinal canal creates a bulging of the intervertebral disc.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The most common feature of lumbar disc damage is low back pain. Radicular pain, which radiates down the buttock and below the knee, along the distribution of the sciatic nerve, generally indicates disc herniation. (Specific manifestations for lumbar disc herniation are summarised in Table 63-6.) The straight-leg raise test may be positive, indicating nerve root irritation. Back or leg pain may be reproduced by raising the leg and flexing the foot at 90°. Low back pain from other causes may not be accompanied by leg pain. Reflexes may be depressed or absent, depending on the spinal nerve root involved. Paraesthesia or muscle weakness in the legs, feet or toes may be reported by the patient. Multiple nerve root (cauda equina) compression may be manifested as bowel and bladder incontinence or impotence.

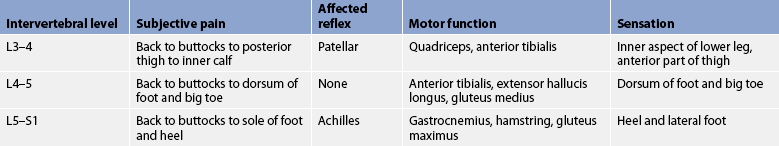

TABLE 63-6 Neurological assessment of herniated intervertebral disc*

* A disc herniation can involve pressure on more than one nerve root.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

X-rays are done to note any structural defects. A myelogram, MRI or CT scan is helpful in localising the damaged site. An epidural venogram or discogram may be necessary if other methods of diagnosis are unsuccessful. An EMG of the extremities can be performed to determine the severity of nerve irritation or to rule out other pathological conditions, such as peripheral neuropathy.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

The patient with suspected disc damage is usually managed first with at least 4 weeks of conservative therapy (see Box 63-3). This includes limitation of extremes of spinal movement (brace, corset or belt), local heat or ice, ultrasound and massage, traction and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. Drug therapy includes NSAIDs, short-term opioids and muscle relaxants. Epidural corticosteroid injections may be effective in reducing inflammation and relieving acute pain. If the underlying cause remains, the pain tends to recur. Conservative treatment can result in a healing over of the damaged area if not due to DDD, with a concomitant decrease in pain. Once the symptoms subside, back strengthening exercises are begun twice a day and are encouraged for a lifetime. The patient should be taught the principles of good body mechanics. Extremes of flexion and torsion are strongly discouraged.

BOX 63-3 Intervertebral lumbar disc damage

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Collaborative therapy

Surgical

Intradiscal electrothermoplasty (IDET)

Radiofrequency discal nucleoplasty

Interspinous process decompression system (X stop)

Laminectomy with or without spinal fusion

Artificial disc replacement (Charité disc)

Spinal fusion with (e.g. plates, screws) or without instrumentation

CT, computed tomography; EMG, electromyogram; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Most patients initially recover with a conservative treatment plan. However, if conservative treatment is unsuccessful, radiculopathy (nerve root pain) becomes progressively worse or loss of bowel or bladder control (cauda equina) is documented, surgery may then be indicated.

Surgical therapy

Surgery for a damaged disc is generally indicated when diagnostic tests indicate that the problem is not responding to conservative treatment and the patient is in constant pain and/or has a persistent neurological deficit. Surgery should be carefully considered, as some patients, for unknown reasons, do not improve after surgery and symptoms may worsen.32

An intradiscal electrothermoplasty (IDET) is a minimally invasive outpatient procedure that may help in treating back and sciatica pain.33 The procedure involves the insertion of a needle into the affected disc with the guidance of an X-ray. A wire is then threaded down through the needle and into the disc. The wire is heated, which denervates the small nerve fibres that have grown into the cracks and invaded the degenerating disc. The heat also partially melts the annulus, which triggers the body to generate new reinforcing proteins in the fibres of the annulus. Although some patients have reported a large reduction in pain with IDET, long-term studies are still needed.34

Another outpatient technique is radiofrequency discal nucleoplasty (coblation nucleoplasty). This procedure involves the insertion of a needle into the disc, similar to IDET. Instead of a heating wire, however, a special radiofrequency probe is used. The probe generates energy, which breaks up the molecular bonds of the gel in the nucleus. The result is that up to 20% of the nucleus is removed, which decompresses the disc and reduces the pressure on both the disc and the surrounding nerve roots. Relief from pain varies among patients. Additional study is needed to determine the effectiveness of this procedure.

A third procedure is the use of an interspinous process decompression system (X stop). This device is made of titanium and fits onto a mount that is placed on vertebrae in the lower back. The X stop is indicated for use in patients with pain due to lumbar spinal stenosis. The device works by pushing open the spinal cord by pressing against parts of either side of the vertebrae. The effect is similar to and less invasive than a laminectomy.35

A laminectomy is a traditional and common surgical procedure for lumbar disc disease. It involves the surgical excision of part of the posterior arch of the vertebra (referred to as the lamina) to gain access to part of or the entire protruding disc to remove it. A minimal hospital stay is usually required after the procedure.

A discectomy is another common type of surgical procedure that may be performed to decompress the nerve root. Microsurgical discectomy is a version of the standard discectomy in which the surgeon uses a microscope to allow better visualisation of the disc and disc space during surgery to aid in the removal of the damaged portion. This helps maintain the bony stability of the spine. A percutaneous laser discectomy is an outpatient surgical procedure using a tube that is passed through the retroperitoneal soft tissues to the lateral border of the disc with local anaesthesia and the aid of fluoroscopy. A laser is then used on the damaged portion of the disc. Small stab wounds are used and minimal blood loss occurs during the procedure. The procedure is effective and safe and decreases rehabilitation time.

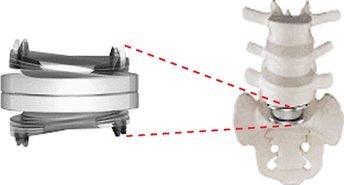

The Charité disc is used in patients with disc damage associated with DDD.36 The disc is made up of a high-density core sandwiched by two cobalt–chromium end plates (see Fig 63-7). This device is surgically placed in the spine through a small incision below the umbilicus after the damaged disc is removed. The disc allows for movement at the level of the implant.

Figure 63-7 The Charité artificial disc, which is used in degenerative disc disease to replace a damaged intervertebral disc. The Charité artificial disc consists of two cobalt–chromium alloy end plates sandwiched around a movable high-density plastic core. The design of the disc helps align the spine and preserve its natural ability to move.

A spinal fusion may be performed if an unstable bony mechanism is present. The spine is stabilised by creating an ankylosis (fusion) of contiguous vertebrae with a bone graft from the patient’s fibula or iliac crest or from a donated cadaver bone. Metal fixation with rods, plates or screws may be implanted at the time of spinal surgery to provide more stability and decrease vertebral motion. A posterior lumbar interbody fusion may be performed in patients to provide extra support for bone grafting or a prosthetic device. The InFuse Bone Graft/LT-CAGE is used to eliminate the need to use bone from the patient in grafting. The device contains genetically engineered protein that stimulates the body to grow new bone at the spinal fusion site.37

NURSING MANAGEMENT: SPINAL SURGERY

NURSING MANAGEMENT: SPINAL SURGERY

Postoperative nursing interventions focus on maintaining proper alignment of the spine at all times until healing has occurred. Depending on the extent and type of surgery, bed rest may be maintained for 1–2 days. Logrolling patients when turning is essential to maintain proper body alignment. Pillows can be used under the thighs of each leg when supine and between the legs when in the side-lying position to provide comfort and ensure alignment. The patient often fears turning or any movement that increases pain by straining the surgical area. The nurse must offer reassurance to the patient that the proper technique is being used to maintain body alignment. Sufficient staff should be available to move the patient without undue pain or strain on staff members or the patient. Depending on the type and extent of surgery and the surgeon’s preference, the patient may be able to dangle their legs at the side of the bed, stand or even ambulate the first day after surgery.

Postoperatively, most patients require opioids such as morphine IV for 24–48 hours. Patient-controlled analgesia allows for optimal analgesic levels and is the preferred method of continued pain management during this time. Once oral fluids have been tolerated, the patient may be prescribed oral drugs, such as paracetamol with codeine or tramadol. Diazepam may be prescribed for muscle relaxation. The nurse should monitor and document pain management and its effectiveness after surgery.

Because the spinal canal may be entered during surgery, there is potential for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage. Severe headache or leakage of CSF on the dressing should be reported immediately. CSF appears as clear or slightly yellow drainage on the dressing. It has a high glucose concentration and will be positive for glucose when a dipstick test is done. The amount, colour and characteristics of drainage should be noted.

Frequent monitoring of peripheral neurological signs of the extremities is a routine postoperative nursing responsibility after spinal surgery. Movement of the arms and legs and assessment of sensation should be unchanged when compared with the preoperative status. Box 63-3 summarises a lumbar laminectomy assessment appropriate for the patient who has undergone back surgery. These assessments are repeated every 2–4 hours during the first 48 hours after surgery and findings are compared with the preoperative assessment. Paraesthesias may not be relieved immediately after surgery. Any new muscle weakness or paraesthesias should be documented and reported to the surgeon immediately. Extremity circulation should be assessed by temperature, capillary refill and pulses.

Paralytic ileus and interference with bowel function may occur for several days and may manifest as nausea, abdominal distension and constipation. The nurse should assess whether the patient is passing flatus, has bowel sounds in all quadrants and has a flat, soft abdomen. Stool softeners (e.g. docusate) may aid in relieving and preventing constipation.

Adequate bladder emptying may be altered because of activity restrictions, opioids or anaesthesia. If allowed by the surgeon, men should be encouraged to dangle the legs at the side of the bed or stand to urinate. Patients should use the commode or ambulate to the bathroom when allowed to promote adequate emptying of the bladder. The nurse should ensure that privacy is maintained. It is necessary to clarify whether the patient can be allowed up to the bathroom without the corset or brace. Intermittent catheterisation or an indwelling catheter may be necessary for patients who have difficulty urinating. Loss of sphincter or bladder tone may indicate nerve damage. Incontinence or difficulty evacuating the bowel or bladder must be monitored closely and reported to the surgeon.

Postoperative activity programs vary with surgeons, but the patient who has had spinal surgery usually ambulates early in the postoperative period. It is a nursing responsibility to know the specific orders related to activity for individual patients.

In addition to the nursing care appropriate for a patient who has had a laminectomy, there are other nursing responsibilities if the patient has also had a spinal fusion. Because a bone graft is usually involved, the postoperative healing time is prolonged when compared with that of a laminectomy. Immobilisation over an extended period of time may be necessary. A rigid orthosis (thoracic–lumbar–sacral orthosis or chairback brace) is often used during the period of immobilisation. Some surgeons require that the patient be taught to put it on and take it off by logrolling in bed, whereas others allow their patients to apply the brace in a sitting or standing position. The nurse should verify the preferred method before initiating this activity. The extended immobilisation required by a spinal fusion carries with it all the potential problems related to immobility.

In addition to the primary surgical site, the donor site for the bone graft must be assessed regularly. The posterior iliac crest is the most commonly used donor site, although the fibula may also be used. The donor site usually causes greater postoperative pain than the fused area. The donor site is bandaged with a pressure dressing to prevent excessive bleeding. If the donor site is the fibula, neurovascular assessments of the extremity are a postoperative nursing responsibility.

As the bone graft heals, the patient must adjust to the permanent immobility at the graft or fusion site. Instruction in proper body mechanics is essential and should be evaluated during the hospital stay. The patient should be instructed to avoid sitting or standing for prolonged periods. Activities that should be encouraged include walking, lying down and shifting weight from one foot to the other when standing. The patient should learn to consciously think through an activity before starting any potentially injurious task such as bending, lifting or stooping. Any twisting movement of the spine is contraindicated. The thighs and knees, rather than the back, should be used to absorb the shock of activity and movement. A firm mattress or bed board is essential.

NECK PAIN

Neck pain may occur almost as frequently as low back pain, affecting up to 90% of adults at some point in their life.38 Neck pain may be the result of many conditions, both benign (e.g. poor posture) and serious (e.g. traumatic injury; see Box 63-4).

Cervical neck sprains and strains occur from hyperflexion and hyperextension injury. Patients have symptoms of stiffness and neck pain and possible pain radiating into the arm and hand. Pain may also radiate into the head, anterior chest, thoracic spine region and shoulders. Cervical nerve root compression from stenosis, DDD or herniation may be indicated by weakness or paraesthesia of the arm and hand. Diagnosing the cause of neck pain is done by history, physical examination, X-ray, MRI, CT scan and myelogram. An EMG of the upper extremities is done to diagnose cervical radiculopathy.

Conservative treatment for neck pain that commonly occurs in patients without an underlying disorder includes: head support via soft cervical collars, heat and ice applications, massage, rest until symptoms subside, physiotherapy, ultrasound and NSAIDs. Most neck pain resolves without surgical intervention. Indications for cervical spine surgery are similar to those for the lower back. Types of surgery are also similar, including a discectomy, laminectomy and spinal fusion. If surgery is performed on the cervical spine, the nurse must be alert for symptoms of spinal cord oedema, such as respiratory distress and a worsening neurological status of the upper extremities. An orthosis or halo vest may be necessary after surgery depending on the degree of spinal stabilisation. After surgery the patient’s neck is immobilised in either a soft or a hard cervical collar.

It is important to prevent benign neck pain, a condition that occurs due to everyday activities such as prolonged sitting at a computer or television, sleeping in non-alignment spinal positions or jarring movements during exercise. Preventative strategies can begin by practising good posture and maintaining neck flexibility (see Box 63-5).

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

1. Bend your head backwards until you are looking up at the ceiling. Repeat slowly 5 times. Stop if experiencing dizziness.

2. Bring your head forwards so that your chin touches your chest and your face is looking down at the floor. Repeat slowly 5 times.

3. Keep your head facing forwards and bend your ear down to one shoulder. Alternate this movement with your other ear. Repeat slowly 5 times on each side.

4. Turn your head slowly around to one side as far as it will go. Repeat on the other side. Repeat the exercise 5 times on each side.

FOOT DISORDERS

The foot is the platform that provides support for the weight of the body and absorbs considerable shock in ambulation. It is a complicated structure composed of bony structures, muscles, tendons and ligaments. It can be affected by: (1) congenital conditions; (2) structural weakness; (3) traumatic injuries; and (4) systemic conditions such as diabetes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis. As the population ages the incidence of abnormalities of the foot is increasing; it is estimated that one in three people over the age of 65 years suffer from foot abnormalities. Much of the pain, deformity and disability associated with foot disorders can be directly attributed to or accentuated by improperly fitting shoes, which cause crowding and angulation of the toes and inhibition of the normal movement of foot muscles.

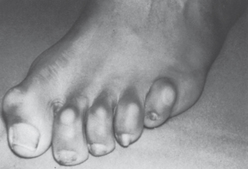

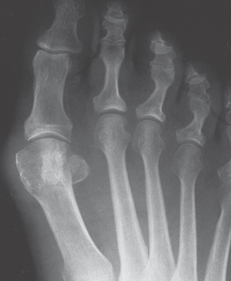

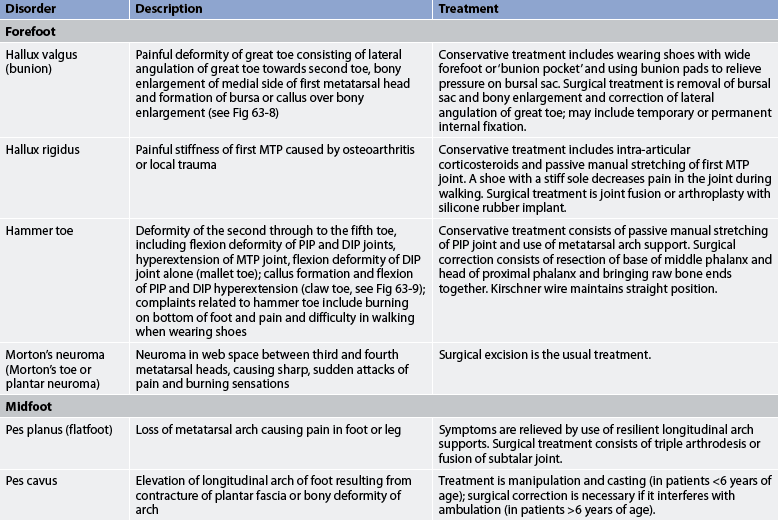

The purpose of footwear is to: (1) provide support, foot stability, protection and shock absorption and act as a foundation for orthotics; (2) increase friction with the walking surface; and (3) treat foot abnormalities. Table 63-7 summarises common foot disorders. One of the most common forefoot disorders is a bunion (see Fig 63-8). A lateral deviation of the great toe, termed hallux valgus, occurs with a bunion.39

TABLE 63-7 Common foot disorders

DIP, distal interphalangeal; MTP, metatarsophalangeal joint; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PIP, proximal interphalangeal.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: FOOT DISORDERS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: FOOT DISORDERS

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

Well-constructed and properly fitted shoes are essential for healthy, pain free feet. Fashion styles, especially for women, often influence selection of footwear instead of considerations of comfort and support (see Fig 63-9). Patient teaching should stress the importance of having a shoe that conforms to the foot rather than to current fashion trends. The shoe must be long enough and wide enough to prevent crowding of the toes and forcing of the great toe into a position of hallux valgus. At the metatarsal head, the width of the shoe should be sufficient to allow free movement of the foot muscles and permit bending of the toes. The shank (narrow part of sole under the instep) of the shoe should be rigid enough to give optimal support. The height of the heel should be realistic in relation to the purpose for which the shoe is worn. Ideally, the heel of the shoe should not rise more than 2.5 cm higher than the forefoot support.

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

Many foot problems require referral to a podiatrist. Depending on the problem, conservative therapy is usually tried first (see Table 63-7). These therapies include NSAIDs, shock-wave therapy, ice, physiotherapy, alterations in footwear, stretching, warm soaks, orthotics, ultrasound and corticosteroid injections. If these methods do not offer relief, surgery may then be recommended.

When surgery is performed, the foot is usually immobilised by a bulky dressing, short leg cast, slipper (plaster) cast or a platform ‘shoe’ that fits over the dressing and has a rigid sole (known as a bunion boot). The foot should be elevated with the heel off the bed to help reduce discomfort and prevent oedema. Neurovascular status should be assessed frequently during the immediate postoperative period. Depending on the type of surgery, pins or wires may extend through the toes or a protective splint that extends over the end of the foot may be in place. Care must be taken not to jar these devices and cause pain. The devices may interfere with or preclude assessment for movement. The nurse should be aware that sensation may be difficult to evaluate because postoperative pain can interfere with the patient’s ability to differentiate pain caused by the surgical procedure from the pain resulting from nerve pressure or circulatory impairment.

The type and extent of surgery determines the degree of ambulation allowed. Crutches, a walker or a cane may be necessary. The patient may experience pain or a throbbing sensation when starting to ambulate. The nurse should reinforce instructions given by the physiotherapist and ensure that the patient does not develop a faulty gait pattern, such as walking on the heels, in an attempt to avoid excessive pain or pressure. The nurse must also reinforce the importance of walking with an erect posture and with proper body weight distribution. Dysfunction of gait or continued pain should be reported to the doctor. The nurse should instruct the patient on the importance of taking frequent rest periods with the foot elevated.

Gerontological considerations: foot problems

The older adult is prone to developing foot problems because of poor circulation, atherosclerosis and decreased sensation in the lower extremities. This is especially a problem for older adults with diabetes mellitus, who may develop an open wound but not feel it because of altered sensation.40 This may be the due to peripheral vascular disease or diabetic neuropathy. Older adults should be instructed to inspect their feet daily and report any open wounds or breaks in the skin to their healthcare provider. If left untreated, wounds may become infected, lead to osteomyelitis and require surgical debridement. If the infection becomes widespread, lower limb amputation may be necessary.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

Foot care should include daily hygienic care and the wearing of clean stockings. Stockings should be long enough to avoid wrinkling and the risk of developing pressure areas. Trimming toenails straight across helps prevent ingrown toenails and reduces the possibility of resulting infection. People with impaired circulation or diabetes mellitus require detailed instruction to prevent serious complications associated with blisters, pressure areas and infections (see Ch 48).

METABOLIC BONE DISEASES

Normal bone metabolism is affected by hormones, nutrition and hereditary factors. When there is dysfunction in any of these conditions, a generalised reduction in bone mass and strength may result. Metabolic bone diseases include osteomalacia, osteoporosis and Paget’s disease.

Osteomalacia

Osteomalacia is a rare condition of adult bone associated with vitamin D deficiency, resulting in decalcification and softening of bone. This disease is the same as rickets in children except that the epiphyseal growth plates are closed in the adult. While it is still a rare condition, the incidence in Australia is thought to be on the increase as people are using strong ‘block-out’ creams to protect themselves from the harmful ultraviolet rays of the sun which, while protecting them from skin cancer, results in decreased vitamin D absorption. Vitamin D, with its complex actions and method of synthesis, is required for the absorption of calcium from the intestine. Insufficient vitamin D intake can interfere with the normal mineralisation of bone, causing failure or insufficient calcification of bone, which results in bone softening. Aetiological factors in the development of osteomalacia include: lack of exposure to ultraviolet rays (which is needed for vitamin D synthesis), GI malabsorption, extensive burns, chronic diarrhoea, pregnancy, kidney disease and drugs such as phenytoin.

HEALTH PROMOTION

The beneficial effects of vitamin D on fracture risk are attributed to two explanations: (1) the decrease in bone loss in older persons; and (2) the increase in muscle strength and balance mediated through vitamin D receptors in muscle tissue.

In addition, vitamin D has been correlated with a significant reduction (22%) in the risk of falling in older people. Pooled analyses reveal that higher doses of 700–800 IU/day are better for reducing fractures than 400 IU/day. Previously, the recommendation for vitamin D in middle-aged and older adults was 400–600 IU/day. With new data and the uncertainty of intake recommendations, higher doses may be more effective (i.e. 700–800 IU/day). However, because calcium was administered in combination with vitamin D in all but one of the higher-dose vitamin D trials, the independent effects of vitamin D alone could not be determined. We still need further research into whether and in what dose calcium adds value to fracture prevention with vitamin D.

Source: Bischoff-Ferrari HA et al. Fracture prevention with vitamin D supplementation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2005; 293:2257–2264.

The most common clinical features of osteomalacia are localised bone pain, and difficulty rising from a chair and walking.41 Other clinical manifestations include low back and bone pain; progressive muscular weakness, especially in the pelvic girdle; weight loss; and progressive deformities of the spine (kyphosis) or extremities. Fractures are common and demonstrate delayed healing when they occur. Mineralisation may take 2–3 months as opposed to the normal 6–10 days.

Laboratory findings commonly associated with osteomalacia are decreased serum calcium or phosphorus levels, decreased serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and elevated serum alkaline phosphatase. X-rays may demonstrate the effects of generalised bone demineralisation, especially loss of calcium in the bones of the pelvis and the presence of associated bone deformity. Looser’s transformation zones (ribbons of decalcification in bone found on X-ray) are diagnostic of osteomalacia. However, significant osteomalacia may exist without changes noted on X-ray.

Multidisciplinary care of osteomalacia is directed towards correction of the vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D3 (chole-calciferol) and vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) can be supplemented and the patient often shows a dramatic response. Calcium salts or phosphorus supplements may also be prescribed. Dietary ingestion of eggs, low-fat milk, fish and vegetables is encouraged. Limited (in Australia) exposure to sunlight (and ultraviolet rays) is also valuable, along with weight-bearing exercise.

Osteoporosis

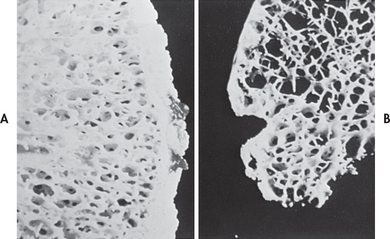

Osteoporosis or porous bone (fragile bone disease) is a chronic, progressive metabolic bone disease characterised by low bone mass and structural deterioration of bone tissue, leading to increased bone fragility (see Fig 63-10). It is known as the ‘silent thief’ because it slowly and insidiously robs the skeleton of its banked resources over many years. Bones can eventually become so fragile that they cannot withstand normal mechanical stress. In Australia, approximately 2 million people suffer osteoporosis (75% of them women), and with the projected increase in life expectancy, this number will grow. It is estimated that by the year 2021 in Australia someone will be admitted to hospital with an osteoporotic fracture every 8–10 minutes.42 Currently, the cost burden of osteoporosis (including factors such as carers and lost income) is estimated at A$7 billion per year, or $20 million per day.43 Figures in New Zealand show that osteoporosis affects more than half of the women and one-third of the men over the age of 60 years, and it is responsible for staggering health costs to the community of NZ$1.15 billion per year.44 Worldwide, osteoporosis is responsible for more hospital days for women over 45 years than any other disease.45

There are several reasons why osteoporosis is more common in women than in men: (1) women tend to have lower calcium intake than men throughout their lives (men aged between 15 and 50 years consume twice as much calcium as women); (2) women have less bone mass because of their generally smaller frame; (3) bone resorption begins at an earlier age in women and is accelerated at menopause; (4) pregnancy and breastfeeding deplete a woman’s skeletal reserve unless calcium intake is adequate; and (5) longevity increases the likelihood of osteoporosis. Despite this disparity, it is important to realise that men can also develop osteoporosis.

Women aged 65 and older should be routinely screened for osteoporosis. Screening should begin by age 60 for women at increased risk of osteoporotic fractures (see Box 63-6). No general recommendations for screening have been made for women who are younger than age 60 or for women aged 60–65 who are not at increased risk of osteoporosis.46

BOX 63-6 Risk factors for osteoporosis

• Family history of osteoporosis

• Long-term use of corticosteroids, thyroid replacements, heparin, long-acting sedatives or antiseizure medications

• Postmenopausal, including early or surgically induced menopause

• History of anorexia nervosa or bulimia, chronic liver disease or malabsorption syndromes

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Risk factors for osteoporosis are female gender, increasing age, family history of osteoporosis, European or Asian descent, small stature, early menopause, a history of anorexia or oophorectomy, sedentary lifestyle and insufficient dietary calcium. Increased risk is associated with cigarette smoking and alcoholism. Decreased risk is associated with regular weight-bearing exercise and fluoride and vitamin D ingestion.45 Low testosterone levels are a major risk factor in men.45

Peak bone mass (maximum bone tissue) is mainly achieved before age 20. It is determined by a combination of four major factors: hereditary, nutrition, exercise and hormone function. Heredity may be responsible for up to 70% of a person’s peak bone mass. Bone loss from midlife (age 35–40 years) onwards is inevitable, but the rate of loss varies. At menopause, women experience rapid bone loss when the decline in oestrogen production is the sharpest. This rate of loss then slows and eventually matches the rate of bone lost by men 65–70 years old.

Bone is continually being deposited by osteoblasts and resorbed by osteoclasts, a process called remodelling. Normally the rates of bone deposition and resorption are equal to each other so that the total bone mass remains constant. In osteoporosis, bone resorption exceeds bone deposition. Although resorption affects the entire skeletal system, osteoporosis occurs most commonly in the bones of the spine, hips and wrists. Over time, wedging and fractures of the vertebrae produce gradual loss of height and a humped back known as dowager’s hump, or kyphosis. The usual first signs are back pain or spontaneous fractures. The loss of bone substance causes the bone to become mechanically weakened and prone to either spontaneous fractures or fractures from minimal trauma. A person who has one spinal vertebral fracture due to osteoporosis has a 25% chance of having a second vertebral fracture within 1 year.47

Specific diseases associated with osteoporosis include intestinal malabsorption, kidney disease, rheumatoid arthritis, hyperthyroidism, chronic alcoholism, cirrhosis of the liver, hypogonadism and diabetes mellitus. Many drugs can interfere with bone metabolism, including corticosteroids, antiseizure drugs (e.g. sodium valproate or phenytoin), aluminium-containing antacids, heparin, certain cancer treatments and excessive thyroid hormones.48 At the time a drug is prescribed, the patient should be informed of this possible side effect. Long-term corticosteroid use is a major contributor to osteoporosis. When a corticosteroid is taken, there is a disproportionate loss of bone resulting from the inhibition of new bone formation.48

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Osteoporosis is a silent disease: bone loss occurs without symptoms. People may not know they have osteoporosis until their bones become so weak that a sudden strain, bump or fall causes a hip, vertebral or wrist fracture. Collapsed vertebrae may initially be manifested as back pain, loss of height or spinal deformities such as kyphosis or severely stooped posture.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Osteoporosis often goes unnoticed because it cannot be detected by conventional X-ray until more than 25–40% of calcium in the bone is lost. Serum calcium, phosphorus and alkaline phosphatase levels are usually normal, although alkaline phosphatase may be elevated after a fracture. Bone mineral density (BMD) measurements are typically used to measure bone density. BMD assesses the mass of bone per unit volume, or how tightly the bone is packed. (BMD measurements are presented in Table 61-6.) Quantitative ultrasound (QUS) measures bone density with sound waves in the heel, kneecap or shin.49 One of the most common BMD studies is dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), which measures bone density in the spine, hips and forearm (the most common sites of fractures resulting from osteoporosis). DEXA studies are also useful to evaluate changes in bone density over time and to assess the effectiveness of treatment. DEXA results are frequently reported as T-scores.

Osteoporosis is quantitatively defined as a BMD of at least 2.5 standard deviations below the mean BMD of young adults. Osteopenia is defined as bone loss that is more than normal (a T-score less than or equal to a range of 1.0–2.5), but not yet at the level for a diagnosis of osteoporosis. Millions of women over the age of 50 suffer osteopenia. Bone biopsy is also used to differentiate the diagnosis of osteoporosis from osteomalacia.

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: OSTEOPOROSIS

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: OSTEOPOROSIS

Multidisciplinary care of osteoporosis focuses on proper nutrition, calcium supplementation, exercise, prevention of fractures and drug therapy (see Box 63-7). Women who are menopausal are most at risk. Treatment is recommended for osteoporosis for postmenopausal women who have: (1) a T-score less than or equal to –2.5; (2) a T-score less than or equal to –1.5 with additional risk factors (see Box 63-6); or (3) a prior history of a hip or vertebral fracture.50,51

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Collaborative therapy

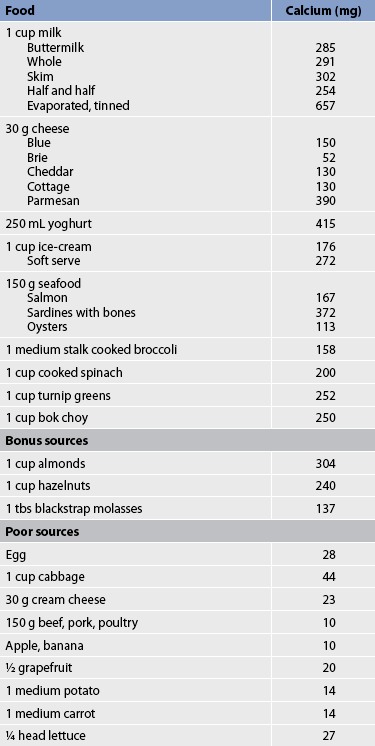

Diet high in calcium (see Table 63-8)

Calcium supplements (see Table 63-9)

Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis focuses on adequate calcium intake (1000 mg per day in premenopausal women, 1300 mg per day for postmenopausal women).52 If dietary intake of calcium is inadequate, supplementary calcium may be recommended. Foods that are high in calcium content include whole and skim milk, yoghurt, turnip greens, cottage cheese, ice-cream, sardines and spinach (see Table 63-8). The amount of elementary calcium varies in different calcium preparations (see Table 63-9). Calcium supplementation inhibits age-related bone loss; however, no new bone is formed.

TABLE 63-9 Elemental calcium content of various oral calcium preparations

| Calcium preparation | Elemental calcium content |

|---|---|

| Calcium carbonate | 500 mg/tablet |

| Calcium gluconate | 40 mg/500 mg |

| Calcium lactate | 80 mg/600 mg |

| Calcium citrate | 40 mg/300 mg |

Vitamin D is important in calcium absorption and function and may have a role in bone formation. Most people get enough vitamin D from the diet or naturally through synthesis in the skin from exposure to sunlight. Being in the sun more than 20 minutes per day is generally enough. In Australia, it is recommended that residents obtain a minimum of 5–15 minutes of exposure to sunlight four to six times per week to prevent deficiency.53 However, in New Zealand, where there is less sun throughout the year, supplementary vitamin D may be required for older adults, for those who are homebound and for those who get minimal sun exposure. Also, supplementary vitamin D (800–1000 IU per day) has been shown to reduce the risk of injury from falls by 30% among people in residential care.54