Chapter 2 Preadmission and preoperative patient care

Introduction

Preoperative care encompasses the unique holistic physical, psychological, emotional and spiritual preparation of patients prior to their surgery. Adequate preoperative preparation can lead to optimal outcomes for the surgical patient. Preoperative care is a complex and dynamic field; however, much of the literature and clinical guidelines lacks evidence. This leaves room for debate on what constitutes optimal patient care (Solca, 2006). The perioperative nurse plays a critical role with patient assessment, preparation, management and evaluation of care.

This chapter explores the preadmission and preoperative care of the perioperative patient. Specifically, elements of preoperative assessment are identified and discussed. Preoperative care of the patient, once in a health care organisation, starts in the preoperative ward and continues into the preoperative holding area. The increasing role of the preadmission clinic is presented, along with the development of nurse-led clinics. The importance of patient education is highlighted. Preoperative tests and examinations and the effects of preoperative smoking are discussed. Discussion includes the importance of the preoperative check for the surgical patient.

Preadmission

The preadmission stage of a patient’s surgical journey is critical in the preparation of the patient for surgery. The requirement to increase the number of patients receiving surgery (maximising theatre utilisation) and reduce waiting lists and waiting times has determined the need for patients to be fully prepared, thus minimising the risk of cancellations or delays (Beck, 2007). The need for increased efficiency has been driven largely by government and policy, such as the New Zealand Health Strategy (Hodgson, 2006) and those developed by the Australian Department of Health and Ageing (2007). The effectiveness of preadmission clinics is demonstrated in an associated reduction in cancellation of cases, shortened length of hospital stay related to increased patient well-being and improved patient satisfaction (Correll et al., 2006; Ferschl et al., 2005; Halaszynski et al., 2004). The preassessment clinic plays an important role in minimising cancellations by having the patient appropriately assessed, investigated and prepared for the surgery (Rai & Pandit, 2003).

Preoperative assessment

Preoperative assessment is the clinical investigation that precedes anaesthesia for surgical or non-surgical procedures and which provides data for the selection of an appropriate anaesthetic strategy (van Klei et al., 2004). Preoperative assessment may be required for surgery that takes place in a variety of practice settings, including, hospitals, clinics, doctors’ rooms and dentists’ rooms, both in the public and private settings.

Traditionally, patients were visited on the wards by the anaesthetist the day before surgery. However, if significant comorbidities were present, this could result in cancellation of surgery. A late cancellation is distressing for the patient and results in under-utilisation of the operating room as it may not be possible to schedule another patient (Van Klei et al., 2002). The provision of preoperative/preadmission clinics has enabled an opportunity to manage comorbidities, provide quality safe perioperative care and reduce cancellations. Box 2-1 outlines the objectives of preoperative assessment.

Box 2-1 Preoperative assessment objectives

The principles of assessment vary and include ensuring that the consultation occurs at an appropriate time and place. The environment should provide adequate privacy for the patient, such as a single-bed consulting room, and the consultation should occur without interruption. Ideally, the consultation should occur several weeks before surgery. This is particularly important if there are significant comorbidities requiring management, special laboratory tests or procedures to be ordered, or planning/management of any anaesthetic concerns, and to allow time for patient education (Barnett, 2005; Garcia-Miguel et al., 2003). Each patient is unique and requires the opportunity to express concerns, ask questions and be supported in their decision-making, even if that means changing their minds as to the intended surgical procedure.

The Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists acknowledges that it is not always possible to plan early consultation and assessment of patients, particularly in cases of emergency; however, it stresses that the consultation must not be modified except when the overall welfare of the patient is at risk (ANZCA, 2003). It also recommends that the assessment of patients prior to anaesthesia is the primary responsibility of the anaesthetist and, where practical, is to be conducted by the anaesthetist who is to perform the anaesthesia (ANZCA, 2003). This differs from Europe and the United States, where nurse anaesthetists or anaesthetic non-physician practitioners may also take part in the preoperative assessment and provide anaesthetic services to patients under the direct supervision of a consultant anaesthesiologist. Wilkinson (2007, p 168) describes the non-physician practitioner role requirement to:

… assess the patients preoperatively, identify any co-morbidity that would render the patient unsuitable for care by an anaesthetic practitioner; form a plan for the anaesthetic in discussion with their supervisor; induce anaesthesia under supervision; maintain the anaesthetic and hand the patient over to recovery staff with a plan for their immediate postoperative care.

However, nurse-led clinics are developing and provide competent preoperative assessments of patients. A study by Kinley et al. (2003) concluded that preoperative assessments by qualified nurses were equal in quality to assessment by pre-registration medical residents. Further discussion on nurse-led clinics is given below.

A number of different health care professionals may be involved in the care and preparation of the patient prior to surgery; for example, preadmission nurse, anaesthetist, dietician, physiotherapist, pharmacist, social worker or occupational therapist. Assessment involves a two-way preadmission interview between the patient and health practitioner so that the patient is assessed physically, psychologically and socially for surgery (Walsgrove, 2006). The preadmission interview is scheduled once the patient returns a completed medical/health questionnaire, and provides the opportunity for information sharing and for education to occur.

The preadmission nurse plays a vital role in the assessment and preparation of the patient for surgery. Assessment by the preadmission nurse includes clarification of the medical/health questionnaire; taking a nursing history; recording of baseline observations; recording of height and weight and the patient’s body mass index (BMI); ordering of preoperative diagnostic and other tests, such as spirometry and electrocardiography (ECG); review of the patient’s current medication, including the use of herbal and complementary medicines; and referral to the anaesthetist or other consultant if required. Venepuncture accreditation for registered nurses allows the preadmission nurse to collect blood samples ordered for required testing.

Nurse-led clinics

Preadmission clinics may be staffed by nurses whose role includes patient preoperative screening. This may detect medical or physical conditions that may generate a referral to the surgeon or anaesthetist, as discussed above (Finegan et al., 2005). Within nurse-led clinics, policies and protocols provide guidance as to when referral may be made to others within the multidisciplinary health care team. Nurse-led clinics may prevent inappropriate admission of unfit patients and reduce late cancellations (Hilditch et al., 2003; Kinley et al., 2003).

The responsibilities and activities of the preadmission nurse may vary between different health care agencies. A major responsibility is to ensure that patients are available and prepared for their allocated surgery. This includes communicating with patients by telephone regarding preoperative diagnostic tests, organisation of the preoperative assessment consultation and detailed patient education so that the patient is prepared for the planned surgery. A study by van Klei et al. (2002) demonstrated that the preadmission nurse can undertake the patient’s health assessment independently, provided the anaesthetist is available to perform additional assessment for patients who are categorised as requiring further assessment.

To be effective, this advanced role requires clinical nurse specialists to be educated to a Master’s level, with skills and knowledge in anatomy, clinical assessment and decision-making (Ormrod & Casey, 2004). Some authors argue that the role is not one of a nurse specialist but rather that of an advanced Nurse Practitioner. The Nurse Practitioner has similar educational qualifications; however, the scope of practice in a speciality field is generally broader (Barnett, 2005). Nurse Practitioners must be able to collect, identify and interpret important information. They provide preoperative information and education, order and review diagnostic test results, perform physical examinations and take medical histories independently, and work collaboratively with other health care providers, such as anaesthetists (Barnett, 2005).

Even though most preoperative assessments are carried out in clinics, some aspects are completed over the telephone. Trials in Britain have demonstrated success in telephone assessment of patients, with the result that more patients can be assessed in a timely manner (Digner, 2007). Strict selection criteria are required to identify patients who are suitable to be assessed via telephone. Suggested criteria include:

The format, policy and protocol of the telephone assessment should be the same as for face-to-face assessment. Consent must also be obtained for telephone assessment, and identification of the correct patient confirmed using unique patient identifiers, such as mother’s maiden name or date of birth.

The types of questions asked during consultation may vary and Table 2-1 provides some examples of preoperative questions. Following consultation, a written summary is included in the patient’s health record.

Table 2-1 Preoperative assessment questions

| Preoperative assessment questions | Rationale |

| History | |

| Knowledge of problems with a previous anaesthetic enables the anaesthetist to prepare for such problems. | |

| 3. Have you or any member of your family had any problems with an anaesthetic? | This may be indicative that the patient may have the same problem. |

| 4. Have you had any previous surgery? | Provides a baseline for education. |

| 5. Do you ever get any chest pain or shortness of breath? | May require the patient to undergo diagnostic tests prior to surgery. |

| Taking of illicit drugs and/or excessive alcohol intake may necessitate increased amounts of anaesthetic agents. | |

| 8. Do you smoke? If so how much, how often? | Smoking effects on pulmonary function. |

| Will affect choice of medications given. | |

| Certain medications, including herbal and complementary therapies, may have consequences for the anaesthetic or surgical procedure. | |

| 13. Do you have any medical problems? | Certain comorbidities require specific preparation before surgery. Prior history may indicate potential medical problems or undiagnosed diseases. |

| Physical | |

| 1. Do you have any dentures or loose teeth, caps or crowns? | Necessary knowledge for induction of anaesthesia and intubation. |

| Provides data for body mass index (BMI) calculation for anaesthetic. | |

| Psychosocial | |

| 1. Do you have any cultural beliefs that we should be particularly aware of, such as Jehovah’s witness? | Ensures cultural safety is observed. |

| 2. Do you have any questions or would you like me to discuss any aspect of the anaesthetic? | Alleviates/minimises anxieties and fears. |

| 3. Is there anything else your surgeon or anaesthetist should know? | Provides opportunity to identify outstanding issues or concerns. |

Adapted from Solca (2006)

The American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) physical status classification system is commonly used to assist in preoperative assessment of patients (Table 2-2). Devised in 1941, the system was meant to assess the degree of sickness or the physical state of a patient prior to selecting the anaesthetic or prior to performing surgery. It is not a tool to be used to determine or measure operative risk (ASA, 2002).

Table 2-2 ASA physical status classification system

| ASA category | Preoperative health status | Comments/examples |

| ASA 1 | A normal healthy patient | Patient able to walk up one flight of stairs without distress. Little or no anxiety. Little or no risk. |

| ASA 2 | A patient with mild disease | Patient able to walk up one flight of stairs but will need to stop after completion of exercise due to distress. History of well-controlled disease states, including non-insulin-dependent diabetes, pre-hypertension, epilepsy, asthma or thyroid conditions |

| ASA 3 | A patient with severe systemic disease | Patients able to walk up one flight of stairs but will have to stop en route because of distress. History of angina pectoris, myocardial infarction (MI), cerebrovascular accident (CVA), heart failure (HF) over 6 months ago. |

| ASA 4 | A patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life | Patient unable to walk up one flight of stairs. History of unstable angina pectoris, MI, CVA, HF within last 6 months. |

| ASA 5 | A moribund patient who is not expected to survive without the operation | Generally, hospitalised, terminally ill patients. |

| ASA 6 | A declared brain dead patient whose organs are being removed for donor purposes | – |

American Society of Anesthesiologists (2007)

While preoperative assessment cannot claim to be the answer to all of the potential problems faced by elective surgical patients, it is vital that health care professionals involved in patient care prepare and coordinate their efforts to ensure the best possible outcome for the patient. Box 2-2 highlights the importance of assessment before admission for surgery.

Box 2-2 Preadmission care of the patient

A systematic review identified two major findings that are useful in suggesting practices to improve the preadmission process for both patients and the day surgery unit. These were the use of preoperative telephone screening or questionnaires, and a preadmission appointment a few days prior to admission. Both of these measures were used to prepare patients for their upcoming operation, whether adults or children, and to create an opportunity for nurses to screen those in whom surgery should be postponed.

Preoperative investigations

In the past, all patients received standard testing regardless of their physical condition. Tests that were directly, indirectly or even remotely related to the planned surgery were ordered. While the tests proved useful as baseline values for those caring postoperatively for the patient, in the current era of cost containment, such testing is not financially practical (Halaszynski et al., 2004). Furthermore, current evidence supports the view that change in patient management rarely occurs as a result of routine testing (Bryson et al., 2006; Johnson & Mortimer, 2002).

Evidence-based guidelines have been developed which rationalise the use of preoperative tests, leading to a reduction of tests ordered with no compromise to patient safety occurring, and the added benefit of reducing costs to both the patient and the health care system (Ferrando et al., 2005; Finegan et al., 2005; Johnson & Mortimer, 2002). Even in patients who are older than 70 years, routine preoperative testing has been shown to be of little benefit (Bryson et al., 2006). Although some authors suggest that routine testing can be completely eliminated, others propose that testing should be based on the patient’s medical condition (Yaun et al., 2005). Each health care institution should develop policies and procedures regarding preoperative assessment and screening.

Medical history

A complete medical history of the individual is required. This includes details of past surgical history, family medical history and current intake of medication. Social history must also be examined, noting alcohol intake, smoking habits, use of illicit drugs and use of non-prescription medications and/or complementary medications. Also noted are the support systems available to the patient following surgery, such as family, church or other community groups (van Klei et al., 2004).

Chest X-rays

The benefit of chest X-ray examinations as part of the preoperative examination is unproven; even when abnormalities are detected the information is not necessarily useful. Furthermore, routine chest X-rays are ineffective in detecting asymptomatic tuberculosis or cancer. Therefore, a preoperative chest X-ray is not recommended in asymptomatic patients, regardless of age (Finegan et al., 2005; Joo et al., 2005).

Electrocardiography

The ordering of a routine 12-lead ECG has been common practice for all adult patients before an operation involving regional or general anaesthesia but there is growing consensus that it is of little benefit and only needed for a subset of patients with cardiac signs and older patients (Ho, 2007). Commonly, an ECG is not routinely needed for asymptomatic males younger than 45 years and females younger than 50 years, and should be based on the clinical needs of the patient. Abnormalities on preoperative ECGs in older patients are common but are of limited value in predicting postoperative cardiac complications (Lui et al., 2002).

Obtaining preoperative ECGs based on an age cut-off alone may not be indicated because ECG abnormalities in older people are prevalent but non-specific and less useful than the presence and severity of comorbidities in predicting postoperative cardiac complications. However, in the elderly, silent myocardial infarction is not uncommon and the availability of a baseline ECG is helpful in the subsequent diagnosis and management of any suspected cardiac event (Finegan et al., 2005; Yuan et al., 2005).

Blood investigations

Traditionally, routine blood tests prior to surgery have been carried out for all patients. This has included a full blood count (FBC), urea, electrolytes and glucose. This practice was expensive for individuals and health care institutions, and offered little advantage to the patient. A study by Johnson and Mortimer (2002) found that, commonly, results were not in the patient’s notes on arrival at the operating room and, when abnormalities were detected, there was little change in patient management.

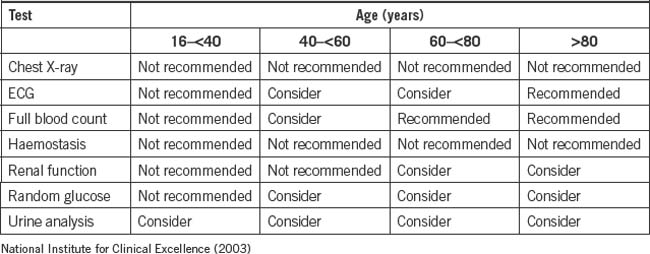

To ensure appropriate ordering of tests, it is recommended that a detailed history and physical examination is performed. For major surgery, a blood group test and screen will also be required to ensure the availability of blood should a transfusion be required. Informed consent is required from patients for authorisation of a blood transfusion prior to a surgical procedure. Documentation of such is recorded in the patient’s health record and/or on the surgical Consent/Agreement to Treatment form. Table 2-3 lists the tests recommended by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence.

Smoking

An assessment of patient smoking habits is ascertained well before surgery and is undertaken by the primary person making the surgical referral. Smoking is a risk factor for postoperative wound dehiscence, wound infections and delayed healing (Warner, 2005b). Smoking also results in a higher incidence of perioperative respiratory and cardiovascular complications compared to non-smoking (Kuri et al., 2005; Warner, 2005a). The optimum length of time a smoker should cease smoking prior to surgery remains unclear; times range from 12 hours to several weeks, with all such cessation showing improvement in, for example, rates of postoperative wound healing (Kuri et al., 2005; Warner 2005a, 2005b). However, there is no absolute evidence that cessation of smoking before surgery reduces complications (Box 2-3).

Box 2-3 Interventions for preoperative smoking cessation

The results of a systematic review showed that preoperative smoking interventions are effective for changing smoking behaviour perioperatively. Direct evidence that reducing or stopping smoking reduces the risk of complications is based on two small trials with differing results. The impact on complications may depend on how long before surgery the smoking behaviour is changed, whether smoking is reduced or stopped completely, and the type of surgery.

Opportunity may be taken by the preoperative health professional to encourage total smoking cessation. For the patient about to undergo surgery, health care professionals need to stress the importance of smoking cessation and provide an explanation of the possible consequences of not stopping smoking. Box 2-4 provides examples of the type of educational information that may be provided to patients preoperatively by health care professionals.

Box 2-4 Preoperative information that may be provided to patients who smoke

Want to stay smoke-free for life?

It is tough to quit but surgery is a great time to try because:

The governments of both New Zealand and Australia have produced strategies and reviews to reduce overall smoking in the general population (Australian Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy, 2004; NZ Ministry of Health, 2004; Wilson, 2007). Options for patients coming into the hospital environment may include nicotine gum, lozenges or patches, which have been found to be effective in helping smokers quit the habit (Shiffman, 2007; Shiffman et al., 2002). All health care organisations are now smoke-free. To assist the patient, health professionals may check their local organisation’s policy regarding the availability of nicotine patches, free of charge to patients who normally smoke, during hospitalisation. Advice available to the patient may take the form of written information or speaking with nurses who specialise in smoking cessation.

Other perioperative considerations

It is necessary to check if the patient has any special needs during the perioperative period (e.g. an interpreter or presence of a carer or significant other). Supporting the patient’s unique needs protects their dignity and allows consumers of health care to maintain control over what is happening to them.

Patient education and information

Preoperative education supports patients by giving a clear and consistent message of the impending surgery from all members of the multidisciplinary health team. Patient education allows informed decisions to be made, with time to reflect on information already given, and provides opportunities to ask questions. Providing preoperative information also helps decrease postoperative pain, reduce length of stay, decease anxiety and increase patient satisfaction (Garretson, 2004).

Fear of the unknown and anxiety are common feelings for many patients and these fears may be eliminated, or at least minimised, with patient education and teaching. Familiarisation with the hospital environment, equipment, procedures, anaesthesia, surgical routine and postoperative expectations provide a locus of control for the patient. This reduces vulnerability, increases confidence and provides an improved overall experience and better outcomes. Patient involvement may also mean ensuring that caregivers and family are briefed on what to expect. A systematic review of knowledge retention from preoperative patient information identified that preadmission teaching is more effective compared to post-admission teaching and knowledge retention (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2000). Group teaching is just as effective as individual teaching and has the added advantage that it is more efficient for health care workers. However, Johansson et al. (2005) argue that a lack of systematic evidence exists about the quality and effectiveness of patient education.

Patient teaching can take several forms, for example, from informal sitting down and conversing with a patient at admission to the ward/perioperative unit, to more formalised, structured teaching/information sessions. Nursing staff play a vital role in the provision of education to the patient. Follow-up communication may be by telephone to ensure that the patient understands all of the preparation requirements, such as fasting or specific surgical preparations.

It is important that the education/information is provided at an appropriate health literacy level for the patient. In other words, it is important to speak clearly without the use of medical jargon, while using active listening skills. A variety of media and tools may be used to provide patient information, including written pamphlets (provided in a variety of languages), videos and practical sessions with equipment, talks, visits and website instruction. A systematic review published by The Joanna Briggs Institute (2000) suggested that the use of pamphlets was particularly beneficial in terms of knowledge of the condition and surgical procedure, exercise or skills performance and the time taken to learn the exercises or skills. Coupled with verbal information provided prior to admission, pamphlets are vital tools in the resources available to empower patients. Notwithstanding the importance of written material, there are disadvantages—they are costly to print, cumbersome to file and store, and hard to keep up to date. Some organisations have moved to developing electronic patient education materials, allowing staff to download and print this or e-mail it to patients (Agre, 2007). Table 2-4 summarises a patient and family teaching guide for preoperative preparation.

Table 2-4 Patient and family teaching guide for preoperative preparation

| Sensory information |

| Procedural information |

| Process information |

| Information about general flow of surgery |

| Where families wait during surgery |

Preoperative visiting

Commonly, patients come into hospitals on the day of surgery, which reduces opportunities for perioperative staff to spend time with patients to ensure that their concerns or issues are addressed. Patient notes and files are generally unavailable until the patient arrives at the operating suite. One of the main advantages of preoperative visiting is the opportunity it provides to plan individual patient care. A preoperative visit allows information to be gained regarding the patient’s physical or mental status, for example, obese patients may require extra or different types of equipment, such as used for positioning, or instruments for their surgery. With preoperative visiting, a collaborative strategy and management of care can be achieved with members of the health care team.

In emergency situations, preoperative visiting becomes a low priority; however, a visit to the emergency department may provide essential information, such as the extent of the injuries, thus allowing planning time for case requirements and estimated time of arrival to the operating room (Wicker & O’Neill, 2006). Management of the care of a trauma patient is vital in order to provide the most efficient and effective treatment to allow maximum chances of outcome and survival.

The concept of preoperative visiting has been considered an important aspect of the perioperative nurse’s role and a way of articulating the patient-centred focus. Although the importance of preoperative visiting is recognised, it is rarely, if ever, undertaken. Advancing technology, changes in the health care system, changing models of care and the predominance of ‘day of surgery’ admission have negated the opportunity for the perioperative nurse to undertake a preoperative visit (Richardson-Tench, 2002).

Preoperative surgical site preparation

Surgical site infection (SSI) is a serious complication of surgery and can be the cause of long illness and, less frequently, death among surgical patients. Preventing a postoperative SSI through preoperative skin preparation has a long history. Bathing with an antiseptic solution and hair removal are two procedures currently undertaken preoperatively to reduce or prevent an SSI.

Preoperative bathing

Preoperative bathing has been practised since the 19th century for the purpose of removing debris and residues and reducing the flora around the surgical site (Seal & Paul-Cheadle, 2004; Webster & Osborne, 2007). The provision of an antiseptic solution to patients for preoperative bathing is widely practised in the belief that it reduces the incidence of SSI. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that patients shower or bathe with an antiseptic agent the night before the operative day, as a nine-fold reduction in skin microbial colony counts has been shown as a result (Seal & Paul-Cheadle, 2004). However, a systematic review conducted by Webster and Osborne (2007) found that six trials, including over 10,000 patients, did not show clear evidence of benefit for the use of chlorhexidine solution over other wash products in the prevention of SSI.

Preoperative hair removal

The removal of hair from the intended surgical wound site has been accepted practice, with different hair-removal methods recommended throughout the world. The CDC guidelines strongly recommend that hair should not be removed preoperatively unless it obscures the incision site. If this is the case, clipping is recommended as shaving causes micro-abrasions, which provides a portal of entry for microorganisms. Furthermore, the CDC recommends that preoperative hair removal takes place as close as reasonable to the time of surgery, preferably less than 2 hours prior to surgery to lessen the opportunity for SSI (CDC, 1999). These guidelines have not been updated.

A systematic review conducted by Kjønniksen et al. (2002) found that there was no strong evidence to advocate against hair removal. However, there was strong evidence to recommend that when hair removal is considered necessary, shaving should not be performed. Instead, a depilatory cream or electric clipping, preferably immediately before surgery, should be used. The findings of Kjønniksen et al. (2002) are supported by the findings of the systematic review by Tanner et al. (2006), who suggest that there is insufficient evidence to state whether removing hair affects SSI rates or when is the best time to remove hair. However, if it is necessary to remove hair, then either clipping or depilatory creams result in fewer SSIs than shaving using a razor. Debate continues regarding hair removal from the intended surgical site.

Preoperative care in the operating suite

Hospital policy designates the exact procedure that should be followed when admitting the patient to the holding area and the operating suite. A general routine includes initial greeting, extension of human contact and warmth, and proper identification. Accompanying documentation, such as the patient’s health record and diagnostic results (e.g. blood and urine testing, chest X-ray and ECG results) are reviewed. Box 2-5 presents the requirements for admission to the operating suite. Detailed admission procedures are discussed below.

Box 2-5 Requirements for preoperative admission

Admission to the preoperative holding room

The preoperative holding area is an area specifically allocated for receiving patients. Characteristically, the environment is quiet, provides privacy and is staffed by an appropriately qualified registered nurse (RN) with skills in patient assessment, decision-making and an understanding of perioperative process and procedure. Some preoperative areas may provide calm, quiet music to minimise patient anxiety. A reassessment of the patient should take place, with time allowed for last-minute questions. A warm blanket, pillow or position adjustment is provided if the patient is uncomfortable (Duncan, 2008).

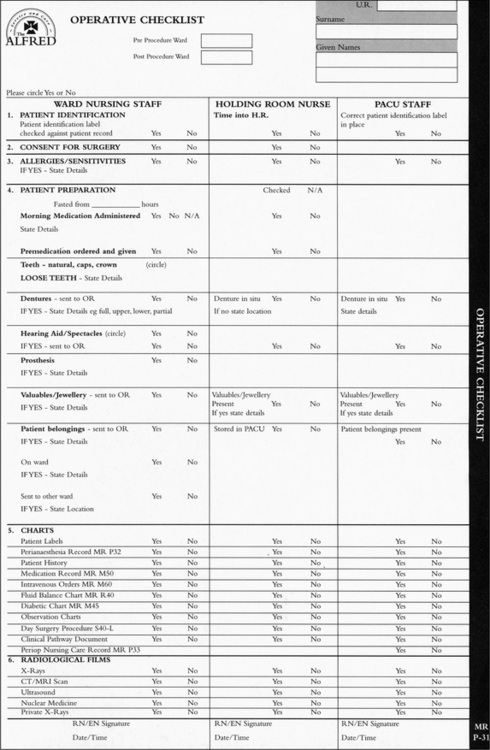

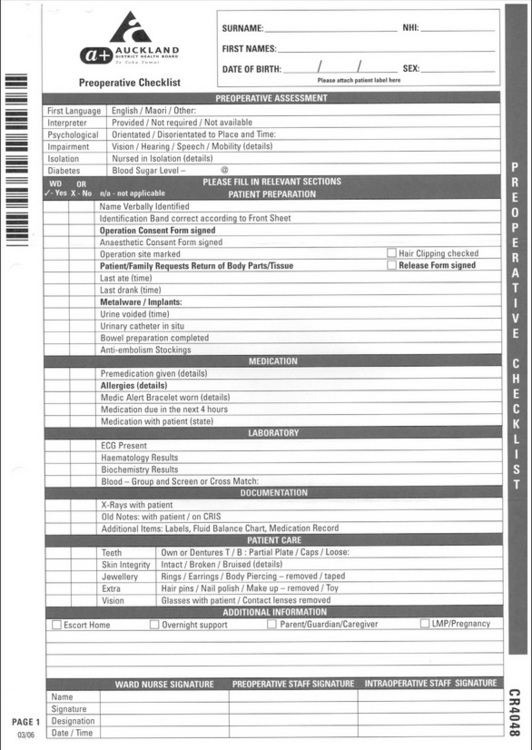

It is the responsibility of the RN, enrolled nurse (EN) or Registered Anaesthetic Technician (AT) (in New Zealand) to ‘check in’ patients prior to surgical procedures. The perioperative nurse or AT will introduce themselves to the patient and receive the handover from the ward nurse, systematically working through the preoperative checklist to ensure that the patient is ready for surgery. Figure 2-1 shows a patient being checked into an operating suite.

Figures 2-2 and 2-3 show examples of a preoperative checklist. While these differ between hospitals, their aim is the same: to ensure patient safety and timely care.

Patient identification

The preoperative nurse is required to ensure the correct identity of the patient. The identification process includes asking patients to state their name, their surgeon’s name, and the operative procedure and location. This information is checked against the patient health record plus their patient identification bracelet/s. Preoperative nurses need to ensure that they are admitting the:

Consent

Informed consent is the process whereby a patient is fully informed regarding their surgery. Patients require balanced information about the procedure, risks involved and alternatives to having surgery. The need for informed consent springs from the legal and ethical right of patients to have total control over what happens to their body (Staunton & Chiarella, 2008) and from the ethical duty of doctors to involve patients in their own health care (Association for Perioperative Practice, 2007; Health and Disability Commissioner, 2007; PNCNZNO, 2005). Ideally, surgical and anaesthetic consent is signed prior to the patient entering the operating suite. It is undesirable for consent to treatment to be gained in the preoperative area. Patient consent is not required in an emergency. Any discrepancies regarding the Consent/Agreement to Treatment form must be queried with the surgeon or anaesthetist prior to transfer to the operating room.

The Consent/Agreement to Treatment form is written in plain English. Interpreter services must be available for patients whose first language is other than English. Only recognisable and agreed upon abbreviations, identified by local policy, may be used to describe procedures. The side of the operation must be written in full, for example, ‘right’ must not be abbreviated to ‘R’ (Queensland Health, 2005). This form is signed by the surgeon, anaesthetist and patient or legal representative. The concept of informed consent is discussed further in Chapter 11.

Allergies and sensitivities

Any allergies or sensitivities that a patient reveals require listing, with the type of reaction noted on the preoperative check-in sheet. This should include non-drug as well as drug reactions/sensitivities. All care is taken during the perioperative continuum to avoid contact with or administration of these allergens. It is common practice for patients to wear an identifying bracelet to highlight any such conditions. The patient with a history of any allergic responsiveness has a greater potential for demonstrating hypersensitivity to drugs administered during anaesthesia (Naismith, 2008). Previous unfavourable reactions to anaesthesia, blood transfusions, latex, iodine and tapes are noted.

Latex allergy

The incidence of latex allergy has increased significantly as the use of rubber gloves in health care settings has increased. Airborne latex particles that adhere to the cornstarch used to powder gloves are a major cause of respiratory symptoms and a source of sensitisation. Those at high risk of latex allergy include health care workers and those undergoing repeated surgeries, especially early in life. Symptoms of latex allergy may progress rapidly and unpredictably to anaphylaxis. All patients coming to the operating rooms are assessed with purposeful questions to identify the risk of latex allergy. If the patient is identified as being at risk, the following steps are required:

Preoperative fasting

Preoperative fasting is an essential component of patient preparation. The rationale of fasting preoperatively is to empty the stomach and, therefore, reduce the risk of the stomach contents being regurgitated and then aspirated into the lungs (Baril & Portman, 2007), which is a rare but dangerous and potentially fatal complication of anaesthesia.

The Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (2006) recommendations for fasting times in adults who are having day surgery are that limited solid food may be taken up to 6 hours prior to anaesthesia and unsweetened clear fluids of not more than 200 mL in adults may be taken up to 2 hours prior to anaesthesia.

Body fluid depletion due to excessive fasting should be avoided. However, it is not unusual for the patient to be fasted from midnight before the surgery, regardless of whether they are first on the list or booked in for the afternoon. In a ‘healthy’ adult having elective (planned) surgery, this is unnecessary and can cause dehydration, headaches, irritability, electrolyte imbalance and malaise (Napoli, 2002). Unrestricted free fluids given 3 hours prior to surgery do not significantly increase gastric volume or affect the stomach pH. There is no indication that the volume of fluid permitted during the preoperative period results in a different outcomes from those participants that follow standard fasting regimens. Flexible and suitable fasting times in relation to scheduled operating times have been identified as improving patients’ postoperative recovery (Brady et al., 2003).

On assessment, some people may be considered to be more likely to regurgitate while under anaesthetic, such as those who are pregnant, on opioids, are obese, or have a neurological deficit, a hiatus hernia or abdominal disorder (Brady et al., 2003). Also, patients who are acutely ill or have been involved in some unexpected event, such as a car accident, requiring them to have surgery, will be treated as though they have a full stomach. The assessment of risk to the patient is made by the anaesthetist, who needs to be fully informed by the preoperative nurse of exactly what the patient has recently had to eat and drink.

Findings from a recent systematic review indicated that, for local and general anaesthesia, a majority of anaesthetists would allow a patient undergoing general anaesthesia to consume clear liquids up to 2 hours before surgery, a light breakfast 6 hours before surgery and solid food up to 8 hours before surgery.

Surgical site marking

If the patient is to undergo surgery on a limb, or any other body part where the potential for operating on an incorrect site exists, such as a kidney, breast or digit, the patient may not proceed to the operating room unless the surgical site is clearly marked (Carney, 2006). The surgeon marks the site with a single-use indelible pen. Alternatively, a variety of commercially produced marking tools are available. The marking consists of an arrow close to, but not directly on, the site of the incision, which must remain visible to the operating room staff when the patient has been draped. If the details of the intended operative procedure differ between the operating list and Consent/Agreement to Treatment form, surgical site marking on the patient or patient opinion, the surgeon is informed prior to transfer to the operating room. When the Consent/Agreement to Treatment form has been completed prior to admission to hospital, the surgeon or delegated registrar is to mark the surgical site of the operation before the patient is moved to the operating room (ACORN, 2006; The Joint Commission, 2003).

Premedication and medications

Special consideration needs to be given to the patient who has been administered a premedication as they may need close observation and surveillance. Once the premedication has been administered on the ward, the Consent/Agreement to Treatment form cannot be amended. Also, if the patient is due other medications while in the operating suite, this needs to be communicated to the operating room staff to ensure timely administration. Regular medications taken orally may be continued unless documented by the anaesthetist (Association for Perioperative Practice, 2007).

An assessment of all current medications and their schedules is undertaken in the preoperative area. Special attention is given to antihypertensive, antianginal, antiarrhythmic, anticoagulant, anticonvulsant and insulin medications (Keglovitz & Kraft, 2002). An assessment of when these medications were last given and next due is prudent and included in the handover to operating room staff.

Diabetic patients who have been fasting preoperatively are monitored closely to ensure they maintain stable perioperative glucose control. The aims of management of diabetic patients are:

Implants

All implants within the patient must be documented on the preoperative form and highlighted during handover. This ensures that the perioperative nurse is alerted to their presence when considering electrosurgical unit (ESU) pad placement. Some implants are large and will have scar tissue encircling them. Scar tissue is high in resistance and placing a return electrode (diathermy plate) over this area may result in a temperature increase underneath the pad (Valleylab, 2003). If the patient has an internal or external pacemaker, bipolar diathermy may need to be used, as monopolar diathermy interferes with the pacemaker signals, potentially causing it to enter an asynchronous mode or block the pacemaker entirely. If the patient has an internal cardiac defibrillator, the cardiologist may need to be consulted (Valleylab, 2004). Consideration is also required with patients with cochlear implants. Diathermy must never be used over the implant as this can cause tissue damage or permanent damage to the implant.

Return of body parts or hair

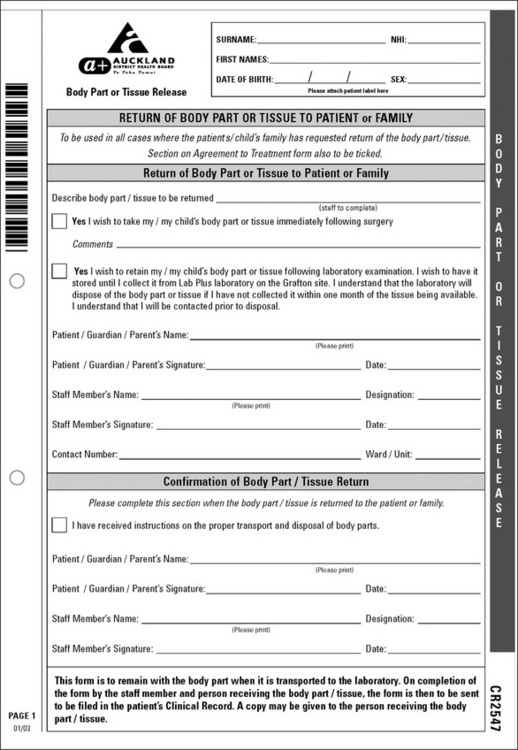

The patient must give informed consent prior to the surgical procedure for the removal of any body part/tissue. Although not commonplace in Australia, it is routine in New Zealand that in every case where hair, specimens or tissue are removed, patients are offered the opportunity to have their body part returned to them on completion of histology or other required testing. The wish to have their body part returned must be clearly documented on the preoperative check form and tissue return form (Fig 2-4). When patients choose to have their body part/tissue returned to them, staff will ensure that the body part/tissue is returned with written instructions if preserved in formalin. In the case of emergency surgery where no wishes have been noted, any body part/tissue removed is retained for subsequent return to the patient.

Jewellery and piercings

The presence of body piercing and jewellery requires attention from the perioperative nurse during the preoperative assessment period and ideally should be removed. This is to minimise the risk of infection, traumatic removal or loss of jewellery. If the jewellery remains in place, such as a wedding band, it needs to be taped to prevent its loss. All mouth, tongue, nasal and facial jewellery must be removed as they create a risk to patients undergoing anaesthetic and operative procedures. Other body jewellery is removed if it is within the operative field or is at risk of being traumatically removed, causing pressure damage, or if it provides an alternate pathway for ESU current. Genital piercing does not have to be removed if the surgery is elsewhere on the body (Association for Perioperative Practice, 2007). If there are any doubts, these should be discussed with the anaesthetist and surgeon. Removed jewellery is given to a family member or labelled and locked away in the ward or hospital safe.

Prevention of deep vein thrombosis

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a clot within a vein, usually occurring in the leg. DVT can occur in surgical patients as a result of their inability to move and change position during anaesthesia compounded with reduced mobility during the postoperative period. A consequence of reduced mobility is the impaired physiological mechanisms for returning blood to the heart from the peripheral circulation. This can lead to stasis of blood in the deep leg veins and the potential development of a DVT. Fragment clots can dislodge and lead to pulmonary or cerebral emboli. These complications are associated with a high rate of morbidity and mortality (Byrne, 2002; Heizenroth, 2003).

To encourage venous return during the perioperative period, anti-embolism stockings are put on the patient preoperatively. This is discussed in detail in Chapter 4.

Preoperative patient warming

All patients have their temperature measured and recorded prior to admission to the operating suite to act as a baseline. Preoperative management of normothermia involves assessing the patient for risk factors of unplanned (inadvertent) perioperative hypothermia. Risk factors include a temperature lower than 36°C on admission, the very young and very old (Association for Perioperative Practice, 2007; Wagner et al., 2006). Inadvertent hypothermia may have detrimental effects on the patient undergoing surgery and has been associated with:

It also interferes with the perception of comfort during patients’ perioperative experience. A further discussion is detailed in Chapter 4.

Conclusion

This chapter has explored the preadmission and preoperative care of the patient through the perioperative continuum. Specifically, elements of preoperative assessment have been identified and discussed. Discussion has included activities undertaken in the preoperative period and the potential consequences for the patient.

The importance of the preoperative phase becomes crucial in the provision of effective and efficient patient care within the environment of shorter hospital stays, an increasing complexity of surgery and comorbidities, longer waiting lists and fiscal constraints.

Critical thinking exercises

1 Preadmission anxiety

At the preadmission clinic Mrs Heath states that she is feeling anxious about the upcoming planned surgery and has a number of questions to ask.

2 Improving patient understanding

Mr Chang has come into the preoperative area with the ward nurse. English is Mr Chang’s second language and he is unable to answer your questions in a way that demonstrates he understands them.

Australian Department of Health and Ageing www.health.gov.au

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence www.nice.org.uk

New Zealand Health and Disability Commissioner www.hdc.org.nz

New Zealand Ministry of Health http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/wpg_Index/Publications-Index

ACORN. ACORN standards for perioperative nursing including nursing roles, guidelines, position statements and competency standards. PS6. Ensuring correct patient, correct site, correct procedure. Adelaide: Australian College of Operating Room Nurses; 2006. (pp. 1–3)

Agre P. Downloading patient-education materials. American Journal of Nursing. 2007;107(7):66-69.

American Society of Anesthesiologists. (2002). Using the ASA physical status classification may be risky business. Retrieved November 5, 2007, from http://www.asahq.org/Newsletters/2002/9_02/vent_0902.htm.

American Society of Anesthesiologists. (2007). ASA physical status classification system. Retrieved November 5, 2007, from http://www.asahq.org/clinical/physicalstatus.htm.

ANZCA. (2003). Professional documents of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. PS7. Recommendations on the pre-anaesthetic consultation. Retrieved November 5, 2007, from http://www.anzca.edu.au/resources/professional-documents/professional-standards/ps7.

ANZCA. (2006). Professional documents of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. PS15. Recommendations for the perioperative care of patients selected for day care surgery—2006. Retrieved November 20, 2007, from http://www.anzca.edu.au/resources/professional-documents/professional-standards/ps15.html/?searchterm=fastingadults.

AORN. Latex guidelines. AORN Journal. 2004;79(3):653-672.

Association for Perioperative Practice. (2007). Standards and recommendations for safe perioperative practice. Retrieved November 5, 2007, from www.afpp.org.uk.

Auckland District Health Board. (2003). Clinical guidelines: Diabetic patients—management of. Retrieved November 5, 2007, from http://www.adhb.govt.nz/_vti_bin/shtml.dll/search/search.htm.

Australian Department of Health and Ageing. (2007). National demonstration hospitals program (NDHP). Retrieved November 6, 2007, from http://www.health.gov.au/internet.wcms/publishing.nsf/Content/health-hospitals-dem.

Australian Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy. (2004). National tobacco strategy, 2004–2009: the strategy. Canberra: AMCDS.

Baril P., Portman H. Preoperative fasting: knowledge and perceptions. AORN Journal. 2007;86(4):609-617.

Barnett J.S. An emerging role for nurse practitioners—preoperative assessment. AORN Journal. 2005;82(5):825-834.

Beck A. Nurse-led preoperative assessment for elective surgical patients. Nursing Standard. 2007;21(51):35-38.

Brady, M., Kinn, S., Stuart, P. (2003). Preoperative fasting for adults to prevent perioperative complications. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4, CD004423.

Brown D., Edwards H., editors. Lewis’s medical–surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems, (2nd ed.), Sydney: Elsevier, 2008.

Bryson G.L., Wyand A., Bragg P.R. Preoperative testing is inconsistent with published guidelines and rarely changes management. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2006;53(3):236-241.

Byrne B. Deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis: the effectiveness and implications of using below-knee or thigh-length graduated compression stockings. Journal of Vascular Nursing. 2002;20(2):53-59.

Carney B.L. Evolution of wrong site surgery prevention strategies. AORN Journal. 2006;83(5):1115-1118. 1121–1122

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1999). Guidelines for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Retrieved March 24, 2008, from www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/guidelines/SSI.pdf.

Correll D.J., Bader A.M., Hull M.W., et al. Value of preoperative clinic visits in identifying issues with potential impact on operating room efficiency. Anesthesiology. 2006;105(6):1254-1259.

Davis B. Perioperative care of patients with latex allergy. AORN Journal. 2002;72(1):47-54.

Digner M. At your convenience: preoperative assessment by telephone. Journal of Perioperative Practice. 2007;17(7):294-301.

Duncan A. Nursing management: intraoperative care. In Brown D., Edwards H., editors: Lewis’s medical–surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems, (2nd ed.), Sydney: Elsevier, 2008. (pp. 393–409)

Ferrando A., Ivaldi C., Buttiglier A., et al. Guidelines for preoperative assessment: impact on clinical practice and cost. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2005;17(4):323-329.

Ferschl M.B., Tung A., Sweitzer B.J., et al. Preoperative clinics visits reduce operating room cancellations and delays. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(4):855-859.

Finegan B.A., Rashiq S., McAlister F.A., O’Connor P. Selective ordering of preoperative investigations by anesthesiologists reduces the number and cost of tests. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2005;52(6):575-580.

Garcia-Miguel F.J., Serrano-Aguilar P.G., Lopez-Bastida J. Preoperative assessment. Lancet. 2003;362(9397):1749-1757.

Garretson S. Benefits of preoperative information programmes. Nursing Standard. 2004;4(18):33-37.

Halaszynski T.M., Juda R., Silverman D.G. Optimizing postoperative outcomes with efficient preoperative assessment and management. Critical Care Medicine. 2004;32(4 suppl):S76-S86.

Health and Disability Commissioner. (2007). Your rights when using a health or disability service in New Zealand and how to make a complaint. Retrieved November 10, 2007, from http://www.hdc.org.nz/complaints.

Heizenroth P.A. Positioning the patient for surgery. In Rothrock J., editor: Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery, 12th ed., St Louis: Mosby, 2003. (pp. 159–186)

Hilditch W.G., Asbury A.J., Crawford J.M. Preoperative screening: criteria for referring to anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:117-124.

Ho C. An audit of the value of pre-operative electrocardiograms before surgery (general anaesthetic) in a day surgery unit. Scottish Medical Journal. 2007;52(2):28-30.

Hodgson, P. (2006). Implementing the New Zealand health strategy 2006. Wellington: NZ Ministry of Health, Wellington. Retrieved November 16, 2007, from http://www.picosearch.com/cgi-bin/ts.pl.

Joanna Briggs Institute. Best practice: knowledge retention from preoperative patient information. Joanna Briggs Institute. 2000;4(6):1-6.

Johansson K., Nuutila L., Virtanen H., et al. Preoperative education for orthopaedic patients: systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;50(2):212-223.

Johnson R.K., Mortimer A.J. Routine preoperative blood testing: is it necessary? Anaesthesia. 2002;57:914-917.

Joo H.S., Wong J., Naik V.N., Savoldelli G.L. The value of screening preoperative chest X-rays: a systematic review. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2005;52(6):568-574.

Keglovitz L., Kraft M. Evaluating the patient before anaesthesia. In Hurford W.E., Bailin M.T., Davison J.K., et al, editors: Clinical anesthesia procedures of the Massachusetts General Hospital, (7th ed.), Philadelphia: Lippincott, Wilkins & Williams, 2002. (pp. 3–15)

Kinley H., Czoski-Murray C., George S., et al. Effectiveness of appropriately trained nurses in preoperative assessment: randomised controlled equivalence/non-inferiority trial. British Medical Journal. 2003;325:1323-1326.

Kjønniksen I., Anderson B.M., Søndenaa V.G., Segadal L. Preoperative hair removal—a systematic literature review. AORN Journal. 2002;75(5):928-938. 940

Kuri M., Nakagawa M., Tanaka H., et al. Determination of the duration of preoperative smoking cessation to improve wound healing after head and neck surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:92-96.

Lui L., Dzankic S., Leung J. Preoperative electrocardiogram abnormalities do not predict postoperative cardiac complications in geriatric surgical patients. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 2002;50:1186-1191.

Moller A., Villebro N. Interventions for preoperative smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005;3:1-14. CD002294

Napoli, M. (2002). Preoperative fasting: rules changed. Retrieved November 16, 2007, from http://www.medicalconsumers.org/pages/newsletter_excerpts.html.

Moores A., Pace N.A. The information given by patients prior to giving consent to anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:703-706.

Naismith C. Nursing management: preoperative care. In Brown D., Edwards H., editors: Lewis’s medical–surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems, (2nd ed.), Sydney: Elsevier, 2008. (pp. 376–392)

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. (2003). Preoperative tests: the use of routine preoperative tests for elective surgery. Retrieved November 16, 2007, from www.nice.org.uk.

Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2005). Guidelines for cultural safety, the Treaty of Waitangi and Māori health in nursing education and practice. Retrieved November 16, 2007, from http://www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/CulturalSafety.pdf.

NZ Ministry of Health. Clearing the smoke: a five year plan for tobacco control in New Zealand 2004–2009. Wellington: NZ Ministry of Health; 2004.

Oakley M. Preoperative assessment. In Pudner R., editor: Nursing the surgical patient, (2nd ed.), London: Elsevier, 2005. (pp. 3–16)

Ormrod G., Casey D. The educational preparation of nursing staff undertaking pre-assessment of surgical patients: a discussion of the issues. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24:256-262.

Pearson A., Richardson M., Peels S., Cairns M. The pre admission care of patients undergoing day surgery: a systematic review. Health Care Reports. 2004;2(1):1-20.

Perioperative Nurses College of New Zealand Nurses Organisation (PNCNZNO). (2005). Recommended standards, guidelines, and position statements for safe practice in the perioperative setting. Retrieved December 5, 2007, from http://www.nzno.org.nz/Site/Sections/Colleges/Perioperative/Standguide.aspx.

Queensland Health. (2005). Queensland health policy statement: ensuring intended surgery. Retrieved December 5, 2007, from http://www.health.qld.gov.au/patientsafety/eis/documents/26961.pdf.

Rai M.R., Pandit J.J. Day of surgery cancellations after nurse-led pre-assessment in an elective surgical centre: the first 2 years. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:684-711.

Ramsden, I.M. (2002). Cultural safety and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu. Victoria University, Wellington, unpublished doctoral dissertation

Richardson-Tench, M. (2002). Unmasked! The discursive practice of the operating room nurse: a Foucauldian feminist analysis. Unpublished thesis. Melbourne: Monash University.

Richardson-Tench M., Pearson A., Cairns M. The changing face of surgery: the use of systematic reviews to establish best practice guidelines for day surgery units. British Journal of Perioperative Nursing. 2005;15(8):240-248.

Seal L.A., Paul-Cheadle D. A systems approach to preoperative surgical patient skin preparation. American Journal of Infection Control. 2004;32(2):57-62.

Shiffman S., Rolf C., Hellebusch S., et al. Real-world efficacy of prescription and over-the-counter nicotine replacement therapy. Addiction. 2002;97:505-516.

Shiffman S. Use of more nicotine lozenges leads to better success in quitting smoking. Addiction. 2007;102:809-814.

Solca M. Evidence based preoperative evaluation. Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology. 2006;20(2):231-236.

Staunton P., Chiarella M. Nursing and the law, (6th ed.). Sydney: Elsevier; 2008.

Tanner, J., Woodings, D., Moncaster, K. (2006). Preoperative hair removal to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2, CD004122.

The Joint Commission. (2003). Universal protocol for preventing wrong site, wrong procedure, wrong person surgery. Retrieved March 5, 2008, from http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/E3C600EB-043B-4E86-B04E-CA4A89AD5433/0/universal_protocol.pdf.

Valleylab. (2003). Clinical information hotline. Electrosurgery safety update: patient return electrode warming. Retrieved November 16, 2007, from http://www.valleylab.com/education/hotline/pdfs/hotline_0303.pdf.

Valleylab. (2004). Clinical information hotline. General cautions and warnings for patient and operating room safety. Retrieved November 16, 2007, from http://www.valleylab.com/education/hotline/pdfs/hotline_0408.pdf.

Van Klei W.A., Hennis P.J., Moen J., et al. The accuracy of trained nurses in preoperative health assessment: results of the open study. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:971-978.

Van Klei W.A., Moons K.G.M., Rutten C.L.G., et al. The effect of outpatient preoperative evaluation of hospital inpatients on cancellation of surgery and length of hospital stay. Anesthesia Analgesia. 2002;94:644-649.

Wagner D., Byrne M., Kolcaba K. Effects of comfort warming on perioperative patients. AORN Journal. 2006;84(3):427-448.

Walsgrove H. Putting education into practice for preoperative patient assessment. Nursing Standard. 2006;20(47):35-39.

Warner D.O. Preoperative smoking cessation: the role of the primary care provider. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2005;80(2):252-258.

Warner D.O. Preoperative smoking cessation: how long is long enough? Anesthesiology. 2005;102:883-884.

Webster, J., & Osborne, S. (2007). Preoperative bathing or showering with skin antiseptics to prevent surgical site infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2, CD004985.

Wicker P., O’Neill J. Caring for the perioperative patient. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2006.

Wilkinson D. Non-physician anaesthesia in the UK: a history. Journal of Perioperative Practice. 2007;17(4):162-170.

Wilson, N. (2007). Review of the evidence for major population-level tobacco control interventions. Wellington: NZ Ministry of Health. Retrieved December 5, 2007, from http://www.moh.govt.nz/tobacco.

Yaun H., Chung F., Wong D., Edward R. Current preoperative testing in ambulatory surgery are widely disparate: a survey of CAS members. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2005;52(7):675-679.

ACORN. ACORN standards for perioperative nursing. Adelaide: Australian College of Operating Room Nurses; 2006.

Barnes P.K., Emerson P.A., Hajnal S., et al. Influence of an anaesthetist on nurse-led, computer-based preoperative assessment. Anaesthesia. 2000;55:576-589.

Berry M. Herbal medicines: considerations for the perioperative setting. Day Surgery Australia. 2007;6(2):10-16.

M. de Chesnay, R. Wharton, C. Pamp. Cultural competence, resilience and advocacy. de Chesnay M., editor. Caring for the vulnerable: perspectives in nursing theory, practice and research. Jones & Bartlett, Sudbury, MA, 2005;31-41.

NZ Ministry of Health. (2004). Clearing the smoke: a five year plan for tobacco control in New Zealand 2004–2009. Retrieved November 16, 2007, from http://www.moh.govt.nz/tobacco.

NZ Ministry of Health. (2007). New Zealand smoking cessation guidelines. Retrieved November 16, 2007, from http://www.moh.govt.nz/tobacco.

Ziolkowski L., Strzyzewski N. Perianesthesia assessment: foundation of care. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing. 2001;16(6):359-370.