Chapter 4 Patient safety

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

Introduction

Patient safety is a paramount consideration of all nurses, but nowhere is this a greater priority than in the perioperative environment. This is due to the vulnerability of the surgical patient and the nature of the environment itself. This chapter explores several key concepts and issues that are directly relevant to patient safety prior to (preoperatively), during (intraoperatively) and immediately following (postoperatively) anaesthesia and surgery. These include patient-specific issues, such as correct patient identification, appropriate preoperative patient assessment and correct patient positioning for the intended surgery. Pertinent anatomical and physiological aspects are also included, with nursing interventions aimed at keeping patients unharmed.

The perioperative environment and related technologies, such as the use of tourniquets, pose their own unique risks; these are explored, along with methods to eliminate, reduce or control them. The risk that surgery poses should not be underestimated, with adverse events occurring more commonly among surgical patients than other patient cohorts. Several of these originate in the perioperative environment.

Patient positioning

To ensure the safety of the patient and surgical team members during patient transfer, a planned approach is needed, and one which takes into consideration patient assessment, the surgical position required and the transfer method to be used.

Patient transfer

Before patient transfer from a trolley or bed to the operating table (and vice versa) the following must be considered:

These factors will influence the team’s preparation and the equipment required to carry out the transfer. The patient’s age and mobility have a bearing on the resources required; for example, a well, mobile patient may be able to move to the operating table unaided. In contrast, an elderly, frail or less mobile patient will require greater assistance from the surgical team and equipment. Particular care, planning and/or equipment is required to manage frail, elderly patients (those over 80 years of age) or obese patients, especially the morbidly obese (Phillips, 2007). The latter require specialised lifting equipment (e.g. ‘hover mats’) and purpose-designed operating tables and fittings to accommodate them safely intraoperatively, and to protect staff.

Care must be taken when transferring patients with intravenous (IV) cannula(s), IV infusions, drains, catheters or other items already in place. Their dislodgement can create discomfort (or worse) and replacing them is time-consuming. The planned procedure, patient condition, and staff and equipment availability will determine whether the initial transfer occurs while the patient is conscious or following induction of anaesthesia. Additionally, consideration must be given for patients who need repositioning intraoperatively (e.g. during bilateral hip replacement), as disorganised or unplanned movements during repositioning increase the risk of damage to the initial operative site, or can result in airway compromise.

Surgeon, anaesthetist and other staff requirements for patient access need to be considered. At all times, the anaesthetist must be able to ensure ventilatory adequacy, have IV access and address requirements for haemodynamic monitoring. The surgeon needs access to the surgical site and the instrument nurse needs to be able to maintain a sterile field throughout the procedure (Fell & Kirkbride, 2007). Consequently, the patient’s position is often a compromise between competing demands for surgical access balanced against the patient’s need for safety and protection (Hamlin, 2005a).

Transfer methods and rationales

All surgical team members have equal responsibility for maintaining patient safety during transfer. The anaesthetist, who has responsibility for the patient’s airway, generally coordinates the lift (Heizenroth, 2007). The duty of the registered nurse (RN) is to assess the surgical environment and patient, and ensure that the most appropriate transfer equipment, positional aids and staff are available. During the transfer a team leader, usually (but not always) the anaesthetist, directs the team, including the patient if he or she is conscious. When the patient is anaesthetised and/or unconscious, this role will normally revert to the anaesthetist, as maintenance of a patent airway and ventilation are the main priorities (Fell & Kirkbride, 2007).

When conscious patients participate in the move, interventions needed to secure a safe transfer include:

Prior to and at each stage of the transfer of a fully conscious patient who is participating in the move, clear directions and explanations are necessary. The staff member instructing patients should direct patients to feel for the sides of the operating table as they move across, so they can be confident they are centrally located. The trolley or bed should not be moved away until the patient is securely positioned and confirms this. If the patient has reduced mobility and cannot move independently, then equipment such as patient slide boards, patient slide sheets or mechanical devices (e.g. hover mat) is needed. These devices enable patient transfer while reducing the risk of injury to staff members. A minimum of four staff members are generally required for the safe transfer of these patients, using the safety precautions described above.

When transferring unconscious or anaesthetised patients, the anaesthetist manages the patient’s airway and supports the head. As the patient has no muscle control, limbs need safeguarding so they do not overhang the operating table, predisposing them to injury.

Arms are secured across patients’ chest or by their side and legs are supported and moved in alignment with the body. These patients will have IV access and monitoring devices established and care must be taken not to obstruct or dislodge these.

Complications

Injuries associated with patient transfer include skin tears, joint dislocations, muscle and/or nerve damage, obstruction or dislodgement of IV infusion tubing or catheters, and patient falls (Phillips, 2007). Additionally, staff members risk injury. These incidents occur when:

All surgical team members require manual handling training, as well as in-service education when new lifting equipment is commissioned. They must also be aware of the potential adverse events associated with transferring and positioning patients so that they can enact prevention strategies and lessen the risk of such events.

Patient positioning

Correct patient positioning is essential to performing a safe and unconstrained surgical procedure. The required position can place patients at risk of injury, particularly if the procedure is lengthy and/or requires general anaesthesia. Patients are positioned so that:

Patients are immobile during surgery and, because they are no longer able to change and control their body position, they are at an increased risk of developing decubitus ulcers, venous thromboembolism and pulmonary dysfunction (Fulbrook & Grealy, 2007). Additionally, unconscious, immobile patients cannot change an uncomfortable position or complain of discomfort or pain related to their position.

Anatomical and physiological considerations for patient positioning

A patient’s tolerance of the stresses imposed by the surgical intervention depends significantly on the normal functioning of the vital systems, and each body system must be considered when planning the patient’s position for surgery. The goals of positioning include the prevention of injury from pressure, crushing, stretching, pinching or obstruction (Phillips, 2007). The development of such injuries is influenced by the:

Integumentary system

The integumentary system can be injured as a result of the physical forces used to maintain the surgical position, as well as the way the patient is moved. These physical forces include pressure, shear and friction (Heizenroth, 2007).

Pressure

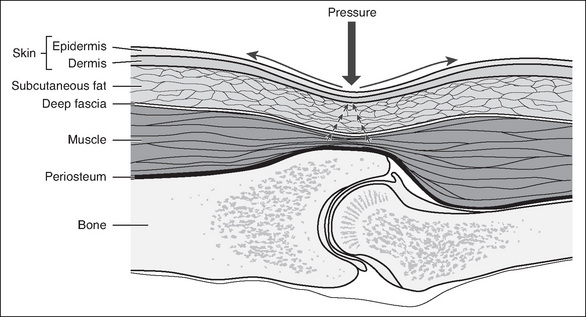

Pressure is the force placed on the patient’s underlying tissues. In order to avoid injury, normal capillary interface pressure (23–32 mmHg) must be maintained (Phillips, 2007). Above these levels, blood flow and tissue perfusion become restricted (see Fig 4-1). Pressure can be created by the patient’s own body weight as gravity presses it downwards. It can also be the weight of devices that are placed on or against the patient, such as instruments, drills or Mayo stands, or surgical team members leaning on the patient. Additionally, bed attachments or positioning aids can press against or pinch parts of the patient’s body.

Shear

Shear is the movement of underlying tissue when the skeletal structure moves while the skin remains stationary. A parallel force creates shear. This occurs when, for example, the head of the operating table is lowered and the patient is placed in a head-down, supine position (Trendelenburg). As gravity pulls the skeleton down, the underlying tissues are stretched, folded or torn as they move with it. This can result in vascular occlusion as well as damaging the (static) skin (Heizenroth, 2007; Phillips, 2007).

Friction

Friction is the force produced when two surfaces rub against each other. Friction to the patient’s skin occurs when the body is dragged across the operating table rather than lifted; this can abrade, burn or tear the patient’s skin and encourage the development of decubitus ulcers (Hamlin, 2008).

The use of a pressure sore risk assessment tool preoperatively can assist in determining the degree of individual patient risk; however, there is limited evidence of the use of such tools (or other preoperative assessment activities) by perioperative nurses, although their use by ward staff may be indicated on the patient’s preoperative checklist (Hurley & McAleavy, 2006).

Musculoskeletal system

During surgery and anaesthesia, normal protective reflexes (e.g. pain and pressure receptors) are depressed in the patient and muscle tone is lost as a result of the action of the pharmacological agents used. Consequently, patients are no longer able to respond normally if, during positioning and surgery, their muscles, tendons and/or ligaments are overstretched, twisted or strained, or body alignment is not maintained. Injury can also occur if dependent limbs fall over the edge of the operating table. It is advisable to use a body strap/safety belt to secure the patient to the operating table.

Nervous system

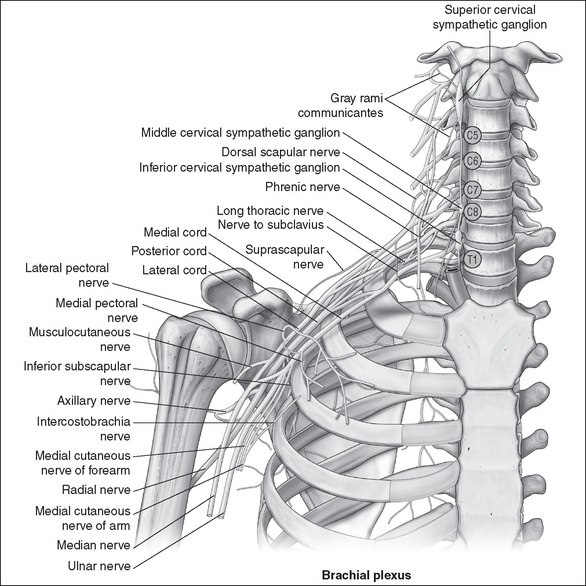

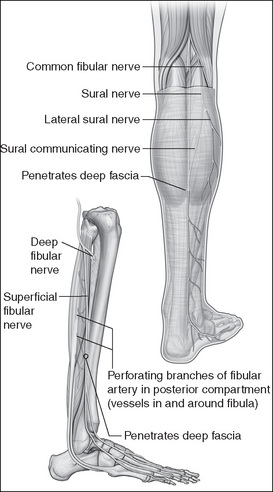

The action of anaesthetic agents, which cause a loss of sensation and protective reflexes, increases the likelihood of nerve injury occurring. In most cases these injuries occur due to the formation of lesions, secondary to damage incurred by undue pressure, stretching, twisting and pinching of nerves. The ulnar nerve is the nerve most frequently injured during the perioperative period (Rank, 2008). Table 4-1 outlines nerves that are commonly injured and the causes (Heizenroth, 2007).

Table 4-1 Peripheral nerves at risk of injury

| Nerve involved | Cause of damage |

|---|---|

| Brachial plexus | |

| Median, radial and ulnar nerves | |

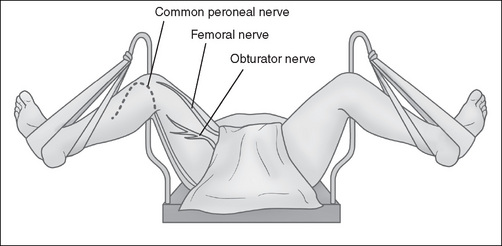

| Femoral nerve |

• Inappropriate positioning of the patient in the lithotomy position, resulting in over-stretching of the nerve (see Fig 4-3)

|

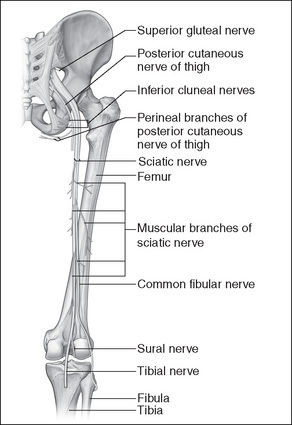

| Sciatic nerve |

• Hyperflexion of the hip joint, particularly when patient’s legs are lifted incorrectly during surgery (see Fig 4-4)

|

| Common peroneal nerve |

Cardiovascular system

Anaesthetic agents can affect the cardiovascular system by causing peripheral vasodilation and subsequent pooling of blood in the extremities, resulting in hypotension (Heizenroth, 2007). Patient positioning can further affect this phenomenon; for example, a head-up, supine (reverse Trendelenburg) position will cause blood to pool in the lower extremities. Consequently, the movement of patients into and out of these positions must be measured and unhurried. Pregnant patients and those with large abdominal masses are particularly at risk of supine hypotensive syndrome (Fell & Kirkbride, 2007).

Adequate arterial circulation is necessary to perfuse tissue, and occlusion or pressure on peripheral vessels, such as might be caused by positioning devices or safety belts/ straps, must be avoided (Phillips, 2007). For example, patients who are placed in the lithotomy position are at risk of compartment syndrome in their lower limb(s), which occurs when perfusion pressure falls below tissue pressure in a closed anatomical space or compartment (Wilde, 2004). This can occur when patients are in this position for extended periods of time. Compartment syndrome develops via a combination of prolonged tissue ischaemia and subsequent reperfusion of muscle within a tight osseofascial compartment and, untreated, leads to necrosis and functional impairment (Dua et al., 2002).

Additionally, there is increased potential for thromboembolic episodes. Different positions, such as lithotomy, the time spent in these positions and the devices used to maintain them (e.g. safety belts, stirrups or other leg-holding devices) contribute to venostasis and the formation of thrombi.

Respiratory system

Respiratory function can also be compromised, particularly when a patient is positioned head-down, supine (Trendelenburg), which causes the abdominal viscera and organs to shift up towards the diaphragm, subsequently affecting inspiratory and expiratory tidal volumes. This is especially so for patients who are obese, pregnant or have pre-existing respiratory disease (Heizenroth, 2007). The prone position also impedes respiratory function. Ideally, patients should spend as little time as possible in these positions. Excessive pressure caused by positional aids or the placement of the patients’ arms on the chest area should also be avoided (Heizenroth, 2007).

Surgical positions

There are several standard surgical positions, with a range of variations, and standard operating tables are designed to accommodate this range. Positions commonly used include:

Supine position

In the supine position, patients lie on their back with their arms either secured at their sides or placed out on an arm board. This commonly used position provides access to the abdominal, peritoneal and cardiothoracic cavities, the extremities and the head and neck. Table 4-2 shows nursing interventions and rationales for this position.

Table 4-2 Supine position—nursing interventions and rationales

| Nursing intervention | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Padded operating table mattress—gel mattress or air support surface overlay. | 1. Padding or special mattress overlays protect occiput, scapulae, olecranon, vertebrae, sacrum, coccyx and calcaneus from undue pressure. |

| 2. Padding or gel pads placed on extensions or other positional aids as required (arm boards, J boards). | 2. Protects ulnar nerve from pressure-induced damage. |

| 3. Heels may require padding/sheepskin bootees, especially if the patient is elderly or malnourished. | 3. Padding/bootees protect the heels from undue pressure. |

| 4. Keep arm board(s) level with the operating table and at an angle of 90° (or less). Arm(s) must be loosely secured to the board. | 4. Protects peripheral vasculature and nerves from damage, including the brachial plexus and ulnar nerve. |

| 5. Legs remain uncrossed at the ankle. | 5. Relieves undue pressure, decreasing risk of venous thrombosis. |

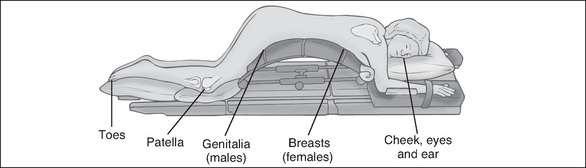

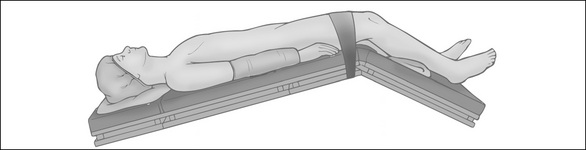

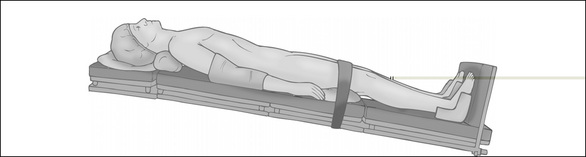

Prone position

In the prone position, patients lie face down. This position is used when surgical access to the spine, rectum or dorsal areas of the extremities is required. It can be achieved on a standard operating table or it may require a specially designed table or table fittings (e.g. a laminectomy frame); the choice is determined by the particular surgical intervention.

The patient is anaesthetised in the supine position prior to transfer, and the airway is secured using a reinforced, flexible endotracheal tube (ETT), which will not kink. The ETT is secured with tape by the anaesthetist. The patient is then lifted and placed with the abdomen down on the operating table, and the face turned to one side. This transfer requires a minimum of four people to be executed safely, with one member of the team, usually the anaesthetist, supporting the patient’s head and neck and safeguarding the airway at all times. The position requires additional padding (often in the form of multiple pillows or rolls on the operating table) to protect vulnerable areas, such as patient’s ear and cheek on the dependent side, the breasts (females), genitalia (males), patellae and toes (see Fig 4-6). Table 4-3 shows nursing interventions and rationales for the prone position.

Table 4-3 Prone position—nursing interventions and rationales

| Nursing intervention | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Padded operating table mattress—gel mattress or pillows/rolls (or gel pad over laminectomy frame, if used). | 1. Extra padding needed to protect vulnerable areas, such as the dependent cheek, ear, breasts (female), genitalia (males), patellae and toes. |

| 2. Padding placed on extensions as required (arm boards, J boards). Arms should be secured loosely, palm down on padded arm boards and kept in natural alignment. They should not be allowed to hang over the edge of the operating table. | 2. Arms are moved down and forward and placed on the arm board slowly and carefully to minimise the risk of damage to the brachial plexus. Arms hanging over the table edge can sustain damage to the radial nerve. |

| 3. Eye ointment placed in both eyes, eyelids are then securely taped closed. | 3. The eyes are vulnerable to corneal abrasion. |

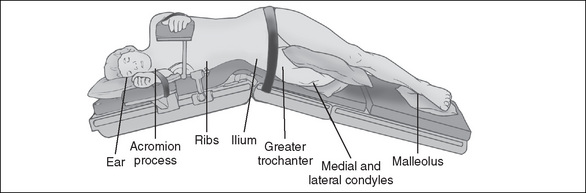

Lateral position

In the lateral position, which is used for procedures involving the chest, kidney or hip joint, the patient lies on the non-operative (dependent) side, with the operative side uppermost. It requires a selection of positional aids to secure the patient because there is a risk of the patient rolling forward or backwards intraoperatively or even falling off the table. The patient is anaesthetised in the supine position and then transferred or turned onto the dependent (non-operative) side. Positional aids include specially designed, padded arm rests (e.g. Carter Brain arm rest) to support the upper arm and keep it away from the operative area; table/safety straps and pliable bean bags are used to hold the patient securely to the operating table and maintain the position throughout surgery (Fig 4-7). Alternatively, padded table attachments (lateral supports or kidney braces), one at the patient’s back and a larger one supporting the abdomen, can be used. Table 4-4 shows nursing interventions and rationales for the lateral position.

Table 4-4 Lateral position—nursing interventions and rationales

| Nursing intervention | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Padded operating table mattress and padding placed on extensions as required (arm boards and arm supports) and pillow for head. | 1. Protection of pressure points on the dependent side—the ear, shoulder, hip, ankle. |

| 2. Pillow is placed between the patient’s knees. | 2. Knees will rub against each other, damaging the skin; additionally, undue pressure can damage the peroneal nerve. |

| 3. Spine is kept in alignment by placing a pillow under the patient’s head. | 3. The spine is vulnerable to misalignment and twisting; this misalignment can place pressure on the dependent brachial plexus. |

| 4. Patient needs securing by the use of either lateral supports (kidney braces) (padded) at the abdomen and back, or the use of devices such as bean bags or a Vac-Pac and a safety belt/ table strap over the patient’s upper thigh. | 4. Prevents the patient from falling off the operating table. The use of these devices also ensures the patient does not move intraoperatively. |

| 5. Ensure the patient’s shoulder on the non-operative (dependent) side is not over-extended and the lower arm is protected, usually by securing it to an arm board. The upper arm is placed on a lateral arm support. | 5. Prevents damage to the brachial plexus and ulnar nerve. |

| 6. Kidney surgery requires access to the retroperitoneal area of the flank. In this case, the patient is positioned so that the lower iliac crestis below the lumbar break where the kidney bridge is located on operating table. The latter is subsequently elevated (slowly) and the operating table flexed to lower the patient’s upper torsoand legs. | 6. Prevents the dependent flank area from compression and subsequent pooling of blood in the lower extremities. |

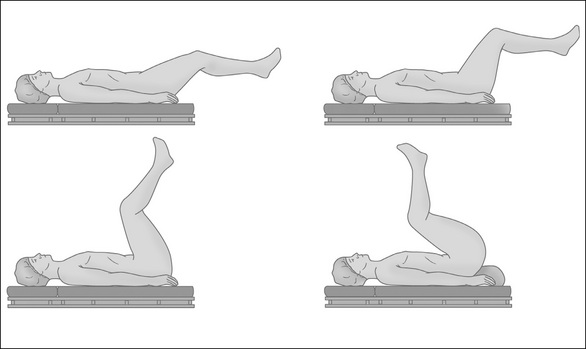

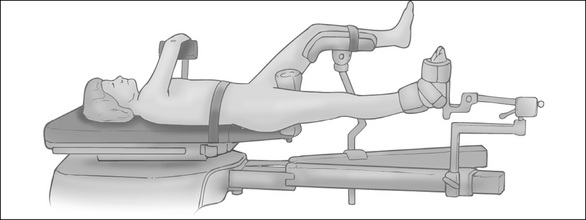

Lithotomy position

For patients undergoing gynaecological and urological surgery, the lithotomy position is required. This position involves the patient lying supine with their legs raised, abducted and secured in leg positioning devices (stirrups) to expose the perineal area. Depending on the surgical access required, the patient’s legs can be held at various angles to the trunk—in a low, standard or high lithotomy position. These positions are maintained with the use of a range of stirrups, which are chosen after considering the type of surgery and proposed length of time for the procedure (Figs 4-8, 4-9). One of the most important precautions to consider while placing a patient in this position is the high risk of nerve damage and hip dislocation if the legs are not raised simultaneously, slowly and at the same angle and height at all times. Table 4-5 shows nursing interventions and rationales for the lithotomy position.

Table 4-5 Lithotomy position—nursing interventions and rationales

| Nursing intervention | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Secure stirrups/leg-holding devices at an equal level and height. | 1. Ensures stirrups do not dislodge during surgery, and that patient’s hips and legs are kept in alignment. |

| 2. Bring the patient’s legs up into the stirrups simultaneously and slowly, keeping them at an equal height and angle at all times. | 2. Maintains hip alignment and prevents dislocation of the hip joint and overstretching of the femoral nerve. Moving them slowly prevents blood pressure fluctuations. |

| 3. The patient’s buttocks should remain on the table at all times and not allowed to overhang. | 3. Reduces the risk of lumbosacral strain and sciatic nerve damage. |

| 4. Ensure the patient’s fingers are not in the way of the stirrups when altering the height and position of the latter. | 4. Fingers can be crushed in the stirrup joints. |

| 5. Ensure the stirrup poles and foot rests are padded. | 5. Padding decreases the risk of thrombus formation or compartment syndrome and protects the posterior tibial and common peroneal nerves. |

| 6. Observe precautions for venous thrombosis during longer procedures. | 6. Pressure on veins from the stirrups can increase the risk of thrombosis formation. |

Trendelenburg position and reverse Trendelenburg position

These positions are variations of the supine position, with patients lying in a dorsal recumbent position (i.e. on their back). The operating table is tilted head down for the Trendelenburg position, which is used for lower abdominal or pelvic surgery (Fig 4-10). In the reverse Trendelenburg position, the patient is head-up, feet down, supine; this position is used for head and neck surgery and minimally invasive, upper abdominal procedures (Fig 45-11). An important factor to consider for these positions is the potential for shearing forces to occur. Thiscan be avoided by flexing the table at the position of the patient’s knees, decreasing the gravitational pull towards the head in the Trendelenburg position. In the reverse Trendelenburg position, a padded table attachment can be fitted to the foot of the operating table on which the patient’s feet rest. Tables 4-6 and 4-7 show nursing interventions and rationales for these positions.

Table 4-6 Trendelenburg position—nursing interventions and rationales

| Nursing intervention | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Observe the same precautions as for the supine position. | 1. This is a supine position variation. |

| 2. Break the table slightly, at the position of the knees. | 2. Helps prevent the effects of shearing forces as it counteracts gravitation pull. |

| 3. Observe respiratory function closely. | 3. Severe angled tilts diminish the patient’s lung capacity due to the pressure of the abdominal organs on the diaphragm, resulting in compression of the lung bases. |

| 4. Observe lower extremity circulation. | 4. May be diminished due to blood pooling in the head and upper torso. |

| 5. Tilt patient in and out of the position slowly. | 5. Avoids sudden blood pressure shifts. |

Heizenroth (2007); Phillips (2007)

Table 4-7 Reverse Trendelenburg position—nursing interventions and rationales

| Nursing intervention | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Observe the same precautions as for the supine position. | 1. This is a supine position variation. |

| 2. Tilt patient in and out of the position slowly. | 2. Avoids sudden blood pressure shifts. |

| 3. Ensure a padded foot rest is secured to the foot of operating table. | 3. Prevents the patient slipping off the table. |

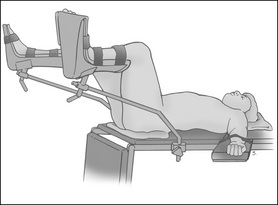

Fracture table position

Some orthopaedic procedures require the use of a specialised fracture table. Indications for use include correcting fractured neck of femurs, as well as performing some femoral procedures, because the table permits rotation and manipulation of the operative limb. Patients are anaesthetised prior to transfer onto this table. They are placed supine on the fracture table with the pelvis stabilised against a well-padded perineal post to protect against genital injury (Fig 4-12). If needed, traction is achieved by restraining the injured limb in a well-padded, boot-like device that is part of the table’s movable traction arm. The non-operative leg is placed on a support attachment and kept out of the way of the operative limb. The patient’s arms are also secured away from the operative field. Nursing interventions associated with the supine position apply. Additionally, the distal lower extremity pulses should be assessed before, during and on case completion.

Fowler’s/semi-Fowler’s position

The patient placed in the Fowler’s/semi-Fowler’s position is secured in an upright (sitting) position. This position is used for surgery involving the ears, nose, shoulders, abdomen, breasts and for some cranial procedures. In the latter case, the patient’s head is held in a brace or supported with a head support attachment. Initially, the patient is placed in the supine position and, once anaesthetised, the table is manipulated so that the patient assumes a sitting position. The angle of this position (Fowler’s or semi-Fowler’s) will vary according to the type of surgery and access required. Arms must be secured so they do not fall by the side of the body. They can rest on a pillow on the lap. A padded footboard prevents foot drop. This position can cause pelvic pooling or venous stasis, resulting in cardiovascular instability, orthopaedic injury and tissue pressure injury/necrosis (Fell & Kirkbride, 2007). It can also cause an air embolus to enter the right atrium, necessitating immediate repositioning of the patient to a left lateral position, placement of the table into steep Trendelenburg and insertion of a central venous catheter to withdraw the air bubble (Phillips, 2007).

Prevention and management of inadvertent hypothermia

Inadvertent (or unplanned) hypothermia is a commonly reported complication in surgical patients (Bellamy, 2007; Bitner et al., 2007). It is defined as the unintentional drop ofa patient’s core body temperature to below 36°C during surgery (American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses, 2001; Welsh, 2002), although this figure is disputed. (Note: Planned hypothermia is an aspect of some cardiopulmonary and neurosurgical procedures.)

The development of a hypothermic state occurs due to the effect of anaesthetic agents on the metabolic rate and on hypothalamic function, resulting in a loss of normal physiological responses (e.g. shivering and vasoconstriction). Extrinsic factors, such as inadequately clothed surgical patients and a low ambient operating room temperature (which is normally 18–20°C), compound the risk, as does lengthy surgery, prolonged exposure of major abdominal/thoracic organs, and the use of cool IV and irrigating fluids (Hardman, 2007).

Patients who are at greater risk of developing inadvertent hypothermia include:

Hypothermia is categorised as mild (32–35° C), moderate (30–32° C) or severe hypothermia (< 30° C), with various symptoms that transpire in each of these classifications (Bellamy, 2007; Saullo, 2007).

Complications

The consequences of inadvertent hypothermia, which are dependent on the change in core temperature, include:

Management strategies

Hypothermia can be prevented if the appropriate strategies are employed. These include patient assessment, regular temperature monitoring of susceptible patients and, if necessary, active warming during the perioperative period. Some evidence suggests that preoperative (or pre-induction) active warming of patients prevents or decreases hypothermia (due to heat redistribution) and is easier to implement and more efficacious than intraoperative warming (Bitner et al., 2007; Kiekkas & Karga, 2005); however, this is disputed (Mahajan, 2007) and is not a widespread practice. Prior to the commencement of surgery the nurse should assess the patient, environment and procedure to be performed in order to establish appropriate preventive measures. These measures may include:

Tourniquets

Tourniquets are often used during surgery on limbs and digits to constrict their blood flow, resulting in a bloodless field at the distal surgical site. These devices may be mechanical (e.g. a blood pressure cuff), or electronic or pneumatic, which utilise a heavier, more secure type of blood pressure cuff, for use on the arms or legs (Phillips, 2007). Pneumatic tourniquets consist of an inflatable cuff connected via tubing to a pressure regulator, compressed gas supply and display unit. Simpler devices, such as rubber tubing or bands, are used on digits.

Recommendations for the safe use of tourniquets include the correct application of the cuff, use of the correct amount of pressure, accurate patient observation and documentation of use, and directions for cleaning and decontamination of cuffs. As there are several differing (and complex) types of tourniquets, specific manufacturer’s recommendations should guide use, in conjunction with departmental policy and procedures.

The use of tourniquets is associated with significant risk (McEwen, 2007; O’Connor & Murphy, 2007). Tourniquets compress underlying soft tissue, as well as deprive the area of blood supply. Consequently, they have been linked to soft tissue injuries involving skin, muscle, nerves and vasculature; additionally, their use can have systemic sequelae (Tuncali et al., 2003). Complications include:

Tourniquet use

When selecting a cuff, the length and width should be individualised for each patient (AORN, 2007). This will depend on the shape and diameter of the extremity and the particular procedure the patient is undergoing (AORN, 2007). The widest cuff possible within any given length should be selected because wider cuffs occlude blood flow at lower pressures. The length of the cuff also needs to be considered; it should overlap by at least 7.5 cm but no more than 15 cm, as excessively long cuffs increase pressure on the underlying tissue and wrinkle the underlying skin. The choice of site of the cuff remains subject to debate (O’Connor & Murphy, 2007).

Prior to tourniquet inflation, an Esmarch’s (rubber) bandage is wrapped around the operative limb to exsanguinate it. To avoid skin damage, soft, wrinkle-free padding is wrapped around the limb before applying the tourniquet cuff. To prevent skin preparation solutions from collecting under the cuff and causing skin maceration or burns, an impervious, U-shaped drape is placed around the cuff. The requisite cuff (or inflation) pressure varies, depending on the patient’s limb occlusion pressure (LOP) (Table 4-8). Ideally, LOP is determined using a Doppler stethoscope (AORN, 2007; O’Connor & Murphy, 2007).

Table 4-8 Tourniquet inflation pressures (adults)

| Limb occlusion pressure (LOP) | Pneumatic cuff pressure |

|---|---|

| < 130 mmHg | Add 40 mmHg pressure |

| 131–190 mmHg | Add 60 mmHg pressure |

| > 190 mmHg | Add 80 mmHg pressure |

For paediatric patients, adding 50 mmHg to LOP is recommended (AORN, 2007).

The use of pneumatic tourniquets is contraindicated in patients with vascular disease, impaired limb circulation, or in the presence of an arteriovenous access fistula because of the increased risk of injury and paralysis (McEwen, 2007). Complications from tourniquet use arise due to excessive cuff pressures and/or length of inflation time. However, there is an apparent paucity of evidence to determine safe time periods of tourniquet ischaemia; recommendations vary from 1 to 2 hours, with a 10–15 minute release of pressure before reinflation (AORN, 2007; McEwen, 2007). In general, upper limbs tolerate shorter periods of ischaemia compared to lower limbs (AORN, 2007).

Newer, automated tourniquets now incorporate pressure-control devices that measure the LOP. These devices stop inflating the cuff once the minimum pressure necessary to occlude the arterial blood flow, distal to the cuff, is reached. Non-automated tourniquets still require the operator of the unit to pre-set the inflation pressure. The use of rubber bands or tubing (e.g. a Penrose drain) on digits precludes the use of pressure monitoring devices. However, as with pneumatic tourniquets, the operative digit should be assessed before and after application, and tourniquet use documented.

The circulating nurse should assess the use of the pneumatic tourniquet regularly to:

Ensuring correct patient/site of surgery

A safe environment for surgical patients requires a planned and systematic approach to perioperative care delivery. Such an approach requires the implementation of policies and procedures that define the actions of staff. A key aspect of surgical patient safety is to ensure that the right patient undergoes the intended surgical intervention. However, humans err, mistakes are made and patients undergo the wrong surgery, or the wrong site or side is operated on. Rogers et al. (2004) identified several common factors that are associated with these particular adverse events. These factors included emergency cases, procedures performed under time pressures, uncommonly seen patient characteristics, procedures being performed by multiple surgeons or numerous procedures being performed on the one patient concurrently. While the incidence and causes of these adverse events are discussed in detail in Chapter 11, it is sufficient to say here that what is known about these adverse events, notwithstanding that such knowledge is imperfect, has led to the collaborative development and implementation of a five-step protocol to reduce or eliminate the incidence of wrong patient/site/side surgeries. Table 4-9 describes the protocol.

Table 4-9 Protocol for ensuring correct patient, correct site, correct procedure

| Step 1 | Check the consent form or procedure request form is correct |

| Step 2 | Mark the site for the surgery or other invasive procedure |

| Step 3 | Confirm identification with the patient |

| Step 4 | Take team ‘time out’ in the operating room, treatment or examination area |

| Step 5 | Ensure appropriate diagnostic images and implants are available |

Australian Commission for Safety and Quality in HealthCare (2004)

‘Time out’ procedure

The confirmation of the patient and procedure happens at several stages of the patient’s perioperative journey, with the final check occurring in the operating room immediately prior to surgery. The ‘time out’ procedure is initiated in the presence of the patient and involves all members of the surgical team, who must be present and must cease all other activities at this juncture. ‘Time out’ requires participating staff to verbally confirm the presence of the correct patient, the marking of the surgical site (when applicable), the planned procedure and the availability of surgical implant(s), if needed. Documentation of this procedure is necessary, although it differs between health care facilities. It is the individual nurse’s responsibility to follow the facility’s process for ‘time out’ and document this.

The surgical count

The purpose of the surgical count is to ensure that all items used during a surgical procedure are removed and can be accounted for on completion of the procedure. This activity is performed to reduce the risk of injury to the surgical patient associated with the inadvertent retention of a surgical item (ACORN, 2006) and is considered the ‘gold standard’ to manage this risk (Gibbs, 2003). The count is the responsibility of the perioperative RN in charge of the case.

Perioperative nursing standards guide the conduct of a count (ACORN, 2006; Perioperative Nurses College [NZNO], 2003). These standards identify roles and responsibilities, spell out a detailed process for conducting a count and provide rationales. They also describe actions to take in emergency surgery or in the event of an incorrect surgical count being recorded. In Australia, the use of the Australian College of Operating Room Nurses’ (ACORN) counting standard has been established in common law as the standard for the practice of counting (Staunton & Chiarella, 2008). However, counting is not always sufficient to prevent the inadvertent retention of surgical items (Gibbs,2003; Gibbs & Auerbach, 2001; Hamlin, 2005b) and other ways to prevent this, which take a systems approach to error reduction, are being developed or trialled; for example, electronic tagging (Fabian, 2005) or the insertion of radiofrequency identification chips in surgical sponges and instruments. The latter has proven successful in pilot studies (Hamlin, 2005b; Macario et al., 2006).

The count

Even though there are minor differences in the published practice standards, the ACORN standard, S3: Counting of accountable items used during surgery (2006) or that published by the Perioperative Nurses College [NZNO], 2003 both provide a comprehensive approach to the surgical count.

Although not all surgical items must be counted per se, the RN in charge of the case is accountable for them. Those items that must be counted include:

Other items can be counted at the discretion of the RN in charge and/or the instrument nurse (ACORN, 2006).

General principles, and roles and responsibilities of staff

All facilities should formulate a policy that outlines a standardised approach to counting and ensure that their surgical teams comply with it.

If an accountable item is opened by the anaesthetic team during the surgical procedure, it is the responsibility of that team member to inform the instrument nurse and/or circulating nurse, who must sight the item and document it on the count sheet.

Undertaking the surgical count

Prior to doing the count, the following actions are needed:

The counting procedure

The counting procedure is as follows:

Limitations with the count standard/procedure

The key weaknesses of the counting standard are the prescriptive nature of the procedure, the lack of clarity about what constitutes an ‘accountable’ item and the Standard’s failure to take into account current technologies and the use of plastics and other non-X-ray detectable items (Hamlin, 2005b). Nonetheless, until emerging technologies and other systematic ways to manage the risk of inadvertent retention of surgical items are developed, counting remains a key activity for perioperative nurses to ensure that no items are unaccounted for at the end of a case.

Incorrect count

According to Rothrock (2007), an incorrect count occurs when the items recorded on the count sheet do not match the actual number of items counted in the final count. If there is a discrepancy, the instrument nurse notifies the surgeon, anaesthetist and the nurse in charge of the operating suite. Such an eventuality requires an immediate search of the surgical environment, including the surgical wound, surgical field, drapes and linen, the floor and garbage receptacles. If the missing item is not located, an X-ray is obligatory prior to the patient leaving the operating room (unless contraindicated by the patient’s condition) and the outcome documented. If the missing item is not located, the count sheet must reflect this. Additionally, a record of the incident, including actions taken to address it, is necessary in line with facility policy.

Research into the incidence of miscounts and incorrect counts has identified that some of these are errors of documentation (Butler et al., 2003). Documentation errors are associated with nursing staff changes intraoperatively and occur more frequently during elective cases. This research also uncovered some evidence of complacency among operating room staff regarding the count, which has been identified by others (Hamlin, 2005b).

Emergency situations

In an emergency and when the patient’s condition is critical, normal counting procedures are waived and an X-ray is performed at the end of the surgical intervention (or when the patients’ condition is sufficiently stable) (ACORN, 2006; Perioperative Nurses College [NZNO], 2003). This practice was appropriate when established decades ago (i.e. before the advent of micro-needles and micro-instrumentation); however, it continues in many operating rooms today (Jackson & Brady, 2008) notwithstanding the limitation of X-rays, which fail to identify many surgical items used in practice currently (Macilquham et al., 2003). The surgeon must be informed when a count is not completed and participate in actions to redress the consequences.

Care and handling of specimens

Many surgical procedures involve the collection of a specimen for pathology testing. The removal of a tissue specimen frequently necessitates an invasive process and it can be potentially devastating if mishandling/loss of the specimen occurs (Watson & Gregory Crum, 2005). Cases of specimen mishandling have resulted in misdiagnoses and, in some instances, patients have been required to undergo additional surgery to remove more tissue for pathology (Watson & Gregory Crum, 2005). In other cases, patients have received inappropriate or aggressive forms of treatment because it has not been possible to provide a satisfactory diagnosis with the remaining tissues (Watson & Gregory Crum, 2005). As a result, it is important to establish clear and unambiguous processes for the collection and transportation of specimens. Additionally, perioperative nurses need to be empowered to manage instances of tissue/specimen mishandling (e.g. if a surgeon drops a tissue sample) via a formal incident reporting system (Espin et al., 2007).

Recommended practices provide guidance for the handling, containment, identi- fication, labelling and transporting of specimens within the perioperative environment and beyond. These are outlined in Table 4-10.

Table 4-10 Correct handling and transportation of specimens

While guidelines such as these are useful, they must be used in conjunction with other practices, such as those associated with infection control and the use of personal protective equipment, and the management of specimens subjected to regular audit.

Prevention and management of venous thromboembolism

The development of venous thrombosis and subsequent pulmonary embolus (PE) make up two components of the condition of venous thromboembolism (VTE). VTE is a mostly preventable surgical complication, yet remains a significant cause of postoperative morbidity and mortality (White, 2003). The factors postulated by Virchow (Mahajan, 2007) as contributing to venous thrombi (and therefore PE) are:

Patients at increased risk of developing VTE are:

Intraoperative risks for the development of VTE include:

Use of a tourniquet may also contribute to VTE (Buggy, 2007; Heizenroth, 2007; McEwen, 2007; Phillips, 2007).

Between 70% and 90% of patients with VTE are asymptomatic (Cantrell et al., 2007; Mahajan, 2007). The symptoms that may develop are summarised in Table 4-11. A greater risk to the patient occurs if a thrombus breaks off and travels via the venous system to the right ventricle, and from there to the pulmonary artery or one of its branches, resulting in a PE, which can be life-threatening. Most PE originate in the lower limb or pelvic veins (Mahajan, 2007).

Table 4-11 Signs and symptoms of VTE

| Deep vein thrombosis | Pulmonary embolism* |

|---|---|

| Calf tenderness and pain, especially on dorsiflexion (positive Homan’s sign) | Tachycardia |

| Swelling and warmth of the affected limb | Dyspnoea |

| Low-grade fever | Chest pain |

| Skin colour changes (erythema) | Hypotension |

| Hypoxaemia | |

| Acute decrease in end-tidal carbon dioxide concentration | |

| Cardiovascular collapse/sudden death |

* Intraoperative and postoperative complication.

Cantrell et al. (2007); Mahajan (2007)

Management

Both pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies and actions can be used to prevent VTE. These are outlined inTable 4-12.

| Phases | Management | |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological | Non-pharmacological | |

| Preoperative | ||

| Intraoperative | ||

| Postoperative | ||

Bryant & Knights (2007); Heizenroth (2007); Mahajan (2007); Phillips (2007)

Pre-emptive management of at-risk patients or immediate treatment of a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) may prevent the subsequent development of PE. However, appropriate, local VTE risk-assessment guidelines are essential so that prophylactic measures are used in the correct at-risk group but are avoided in low-risk groups (Illingworth & Timmons, 2007).

Conclusion

This chapter has provided information pertinent to patient safety within the perioperative setting. It has outlined basic anatomical and physiological considerations related to patient transfer and positioning, the potential sequelae for incorrectly positioned patients and the interventions necessary to avoid them. Common complications related to surgery, such as inadvertent (unplanned) hypothermia and venous thromboembolism, and the measures used to prevent or ameliorate them, have been explored, and their limitations in practice noted. This chapter has also examined the policies, procedures and standards that underpin correct site surgery and the surgical count, and presented some of the research that highlights the weaknesses of them. Nonetheless, these practices and their underpinning standards provide guidance for perioperative nursing care, and they evolve continuously. Best practice related to the care and handling of tissue specimens has been addressed, along with caring for patients when tourniquets are used to facilitate surgery.

Although trite, it is true that no health care professional sets out to do harm; however, humans err, mistakes are made and patients experience adverse events. The sections covered in this chapter have provided rationales for the interventions commonly used to prevent these adverse events and ensure the patient is provided with the safest possible care.

Critical thinking exercises

1 Patient transfer

You are the circulating nurse working in an orthopaedic operating room. Your patient has been wheeled into the operating room by the anaesthetist and you are preparing to transfer her onto the operating table.

2 Pressure area care

Your patient is undergoing a laminectomy and has been anaesthetised and placed in the prone position on a laminectomy frame on the operating table.

3 Inadvertent (unplanned) hypothermia

You are allocated the role of anaesthetist nurse for a hemicolectomy procedure on a 72-year-old female. Two hours into the procedure, you notice that the patient’s temperature has dropped from a baseline of 36.5°C to 35°C.

American Association of Nurse Anesthetists www.aana.com

American Society of periAnesthesia Nurses www.aspan.org

Anesthesiology www.anesthesiology.org

Association for Perioperative Practice www.afpp.org.uk

Association of periOperative Registered Nurses www.aorn.org

Australian College of Operating Room Nurses www.acorn.org.au

Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists www.anzca.edu.au

International Federation of Nurse Anesthetists www.ifna-int.org

International Federation of Perioperative Nurses www.ifpn.org.uk

Operating Room Nurses Association of Canada www.ornac.ca

ORNursesDownUnder http://www.angelfire.com/nd/ornursesdownunder

Patient Safety Institute www.ptsafety.org

Perioperative Nurses College of the New Zealand Nurses Organisation www.pnc.org.nz

Preoperative education http://www.aorn.org/patient

Preop Surgery Centre www.preop.com

ACORN. ACORN standards for perioperative nursing including nursing roles, guidelines, position statements and competency standards. Adelaide: Australian College of Operating Room Nurses; 2006.

American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses. Patient temperature: an introduction to the clinical guideline for the prevention of unplanned perioperative hypothermia. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing. 2001;15(3):151-155.

AORN. Standards, recommended practices and guidelines. Recommended practices for handling specimens in the perioperative practice setting. Denver, CO: Association for periOperative Registered Nurses; 2006.

AORN. Standards, recommended practices and guidelines. Recommended practices for the use of the pneumatic tourniquet in the perioperative practice setting. Denver, CO: Association for periOperative Registered Nurses; 2007.

Australian Commission for Safety and Quality in HealthCare. (2004). Charting the safety and quality of healthcare in Australia. Retrieved November 16, 2007, from http://www.safetyandquality.org/internet/safety/publishing.nsf/Content/F1AB7CD29C037EFBCA25716F00033691/$File/chartbk.pdf

Bellamy C. Inadvertent hypothermia in the operating theatre: an examination. Journal of Perioperative Practice. 2007;17(1):18-25.

Bitner J., Hilde L., Hall K., Duvendack T. A team approach to the prevention of unplanned postoperative hypothermia. AORN Journal. 2007;85(5):921-929.

Buggy D. Metabolism, the stress response to surgery and perioperative thermoregulation. In Aitkenhead A., Smith G., Rowbotham D., editors: Textbook of anaesthesia, (5th ed.), Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2007. (pp. 400–415)

Butler M., Boxer E., Sutherland-Fraser S. The factors that contribute to count and documentation errors in counting: a pilot study. ACORN Journal. 2003;15(1):10-14.

Bryant B., Knights K. Pharmacology for health professionals, (2nd ed.). Sydney: Elsevier; 2007.

Cantrell S., Ward K., Van Wicklin S. Translating research on venous thromboembolism into practice. AORN Journal. 2007;86(4):590-604.

Drake R., Vogl W., Mitchell A. Gray’s anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005.

Drake R., Vogl W., Mitchell A., et al. Gray’s atlas of anatomy. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2008.

Dua R., Bankes M., Dowd G., Lewis A. Compartment syndrome following pelvic surgery in the lithotomy position. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2002;84(3):170-171.

Espin S., Regehr G., Levinson W., et al. Factors influencing perioperative nurses’ error reporting preferences. AORN Journal. 2007;83(3):527-543.

Fabian C. Electronic tagging of surgical sponges to prevent their accidental retention. Surgery. 2005;137(3):298-301.

Fell D., Kirkbride D. The practical conduct of anaesthesia. In Aitkenhead A., Smith G., Rowbotham D., editors: Textbook of anaesthesia, (5th ed.), Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2007. (pp. 297–314)

Fulbrook P., Grealy B. Essential nursing care of the critically ill patient. In: Elliot D., Aiken L., Chaboyer W., editors. ACCCN ’s critical care nursing. Sydney: Elsevier, 2007. (pp. 187–214)

Gibbs, V. (2003). Retained surgical sponge. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Morbidity & Mortality Rounds on the Web. Retrieved April 8, 2008, from http://www.webmm.ahrq.gov/cases.aspx.

Gibbs, V., & Auerbach, A. (2001). The retained surgical sponge. In K. Shojania, B. Duncan, K. McDonald, R. Wachter (Eds.). Making healthcare safer: a critical analysis of patient safety practices (pp. 255–257). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Retrieved April 8, 2008, from http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/ptsafety/chap22.htm

Hamlin L. Perioperative concepts and nursing management. In: Farrell M., editor. Smeltzer and Bare’s medical-surgical nursing. Sydney: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2005. (pp. 400–465)

Hamlin, L. (2005b). Setting the standard: the role of the Australian College of Operating Room Nurses. University of Technology, Sydney, unpublished doctoral thesis

Hamlin L. Perioperative nursing. In Wilson V., Hillege S., French J., editors: Taylor’s fundamentals of nursing, (7th ed.) (in press), Sydney: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

Hardman J. Complications of anaesthesia. In Aitkenhead A., Smith G., Rowbotham D., editors: Textbook of anaesthesia, (5th ed.), Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2007. (pp. 367–399)

Heizenroth J. Positioning the patient for surgery. In Rothrock J., McEwen D., editors: Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery, (13th ed.), Louis: St Mosby, 2007. (pp. 130–157)

Hurley C., McAleavy J. Preoperative assessment and intraoperative care planning. Journal of Perioperative Practice. 2006;16(1):187-914.

Illingworth C., Timmons S. An audit of intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) in the prophylaxis of asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Journal of Perioperative Practice. 2007;17(11):522-528.

Jackson S., Brady S. Counting difficulties: retained instruments, sponges and needles. AORN Journal. 2008;87(2):315-321.

Kiekkas P., Karga M. Prewarming preventing intraoperative hypothermia. British Journal of Perioperative Nursing. 2005;15(10):444-451.

Macario A., Morris D., Morris S. Initial clinical evaluation of a handheld device for detecting retained surgical gauze sponges using radiofrequency identification technology. Archives of Surgery. 2006;141:659-662.

Macilquham M., Riley R., Grossberg P. Identifying lost surgical needles using radiographic techniques. AORN Journal. 2003;78(1):73-78.

Mahajan R. Postoperative care. In Aitkenhead A., Smith G., Rowbotham D., editors: Textbook of anaesthesia., (5th ed.), Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2007. (pp. 484–509)

McChlery S. The perioperative care of a super morbidly obese pregnant woman: a case study. Journal of Perioperative Practice. 2007;17(11):530-534.

McEwen, J. (2007). Complications and preventative measures. Retrieved March 4, 2008, from http://www.tourniquet.org.

O’Connor C., Murphy S. Pneumatic tourniquet use in the perioperative environment. Journal of Perioperative Practice. 2007;17(8):391-397.

Parnaby C. A new anti-embolism stocking. Journal of Perioperative Practice. 2004;14(7):302-307.

Perioperative Nurses College (NZNO). (2003). Standards and guidelines for safe practice. Retrieved January 13, 2008, from http://www.pnc.org.nz/Site/Sections/Colleges/Perioperative/About.aspx

Phillips N. Berry & Kohn’s operating room technique, (11th ed.). St Louis: Mosby; 2007.

Rank D. Patient positioning an OR team effort. OR Nurse. 2004;2(1):21-23.

Rogers M.L., Cook R.I., Bower R., et al. Barriers to implementing wrong site surgery guidelines: a cognitive work analysis. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics. 2004;34(6):757-763.

Rothrock J. Patient and environmental safety. In Rothrock J., McEwen D., editors: Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery, (13th ed.), Louis: St Mosby, 2007. (pp. 15–42)

Saullo D. Trauma surgery. In Rothrock J., McEwen D., editors: Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery, 13th ed., Louis: St Mosby, 2007. (pp. 1165–1197)

Staunton P., Chiarella M. Nursing and the law, (6th ed.). Sydney: Elsevier; 2008.

Tuncali B., Karci A., Bacakoglu A.K., et al. Controlled hypotension and minimal inflation pressure: a new approach for pneumatic tourniquet application in upper limb surgery. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2003;97:1529-1532.

Turpie G.G., Chin B.S.P., Lip Y.H. ABC of antithrombotic therapy. Venous thrombroembolism treatment strategies. British Medical Journal. 2002;325:948-950.

Watson D.S., Gregory Crum B.S. Improving specimen practices to reduce errors. AORN Journal. 2005;82(6):1051-1054.

Welsh T. A common sense approach to hypothermia. American Association of Nurse Anesthetists Journal. 2002;70(3):227-231.

White R. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;17(suppl 1):14-18.

Wilde S. Compartment syndrome: the silent danger related to patient positioning and surgery. British Journal of Perioperative Nursing. 2004;14(12):546-554.

Aitkenhead A.R., Smith G., Rowbotham D.J., editors. Textbook of anaesthesia, 5th ed., Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2007.

AORN. Recommended practices for the prevention of unplanned perioperative hypothermia. AORN Journal. 2007;85(5):972-988.

Brown J., Feather D. Surgical equipment and materials left in patients. British Journal of Perioperative Nursing. 2005;15(6):259-265.

Caprini, J. (2005). Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. American Journal of Medicine—Continuing Medical Education Series, 1–10.

Drain C.B. Perianesthesia nursing a critical care approach, 5th ed. St Louis: Saunders; 2008.

Kehl-Pruett W. Deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients: a review of evidence-based guidelines for prevention. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 2006;25(2):53-61.

Martin J., Warner M. Positioning in anesthesia and surgery, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1997.

Miller R. Miller’s anesthesia, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2004.

Tetro A.M., Rudan J.F. The effects of a pneumatic tourniquet on blood loss in total knee arthroplasty. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 2001;44(1):33-38.

Van Wicklin S., Ward K., Cantrell S. Implementing a research utilization plan for prevention of deep vein thrombosis. AORN Journal. 2006;83(6):1353-1368.