Information retrieval in pharmacy practice

How to categorize health- and medicine-related information

How to categorize health- and medicine-related information

Relevant search and retrieval processes

Relevant search and retrieval processes

Introduction

The current era is characterized by man’s inordinate ability to store, retrieve and transmit large volumes of information using computer technology. Albert Einstein proposed that the secret of success is ‘to know where to find the information and how to use it’. Most pharmacists would probably agree. This chapter aims to provide the reader with a theoretical understanding of how to source health- and medicines-related information in the present information age. While the quality of retrieved information is considered, guidance on the detailed evaluation of what is known broadly as ‘clinical evidence’ is found elsewhere (see Ch. 20).

In the GPhC’s Standards of conduct, ethics and performance, the knowledge and provision of health- and medicines-related information, specifically, is considered in the following manner. In relation to their own knowledge and competence, pharmacists must develop their skills in-line with their area of expertise, keeping up-to-date with relevant progress through CPD (see Ch. 6). In relation to the provision of medicines-related information to those who want or need it, pharmacists are expected to be able to provide accurate, reliable, impartial, relevant and up-to-date information.

Yet with thousands of medicinal products, dressings and appliances on the UK market, pharmacists are highly unlikely to hold in-depth knowledge of all health- and medicines-related issues at all times. Therefore, the ability to retrieve relevant health- and medicines-related information in a timely and efficient manner becomes central to the practice of all pharmacy professionals (Box 16.1).

Where does information exist and how can it be retrieved?

Information retrieval is the tracing and recovery of stored information. Information can range from patient information to drug monographs, to more sophisticated health technology assessments. It can exist in many forms from the archives of a drug company to the worldwide web. Effective information retrieval requires an understanding of the range of relevant information available, where it exists and how it might be sourced.

Pharmacists sourcing information are likely to use the internet at some point during their search. The expanse of information on the Web and its apparent accessibility has integrated the internet into most work routines. While, on the whole, the seemingly endless material may not suit most pharmacists’ information needs, there are specific online resources that pharmacists can browse. These include websites operated by governments, professional, practice, regulatory or academic bodies, as well as websites belonging to patient groups and the pharmaceutical industry. However, the fluid nature of the internet, the vast array of information available, plus the variable nature of each query will probably involve pharmacists in some degree of internet searching. This necessitates an understanding of search engines and search strategies. There are databases on the net and on CD-ROM which act as directories for scientific papers and other publications and, as such, can be used to search for available material.

Before widespread use of the internet, the principal source of health-related information was the printed book. Books still contain a vast array of indispensable information and reputable ones play a vital role in information management. Although individual pharmacies may not keep the full range of essential books, specialist centres will have access to these and to other resources.

The internet

The internet in its current form came into being in 1983 and the web came into widespread use from the mid-1990s onwards. From the beginning, it acted as a place where large numbers of files and documents could be stored for download, circulation, discussion and communication. These days, many thousands of documents and other items are added to the web every hour and so it is not possible to create a comprehensive directory of the web. Most people create their own directory of useful websites or search the internet for the information they need.

The web address

The term ‘website’ is used to denote a set of themed, linked web pages, usually accessed via a ‘homepage’. Web pages are written in hypertext markup language (htm/html). A web page is a collection of text, graphics, sounds and/or video that corresponds to a single window of scrollable material. Web pages are stored on a web server, which hosts the website and ‘dispenses’ the pages in response to a web browser. The web browser displays web pages after communicating with the server. There are a large number of browsers.

Each page on the web has a distinct web address known as the uniform resource locator (URL). The URL can be a good clue as to the quality of the information found on a website. The ‘locator’ in URL can also give an indication of where one is within a website and indicate the source of the information being viewed.

A web address or website name appears on the address bar. All website names are part of the domain name system (DNS) and look similar to this: http://www.dh.gov.uk/.

Box 16.2 breaks down this address and examines the individual parts.

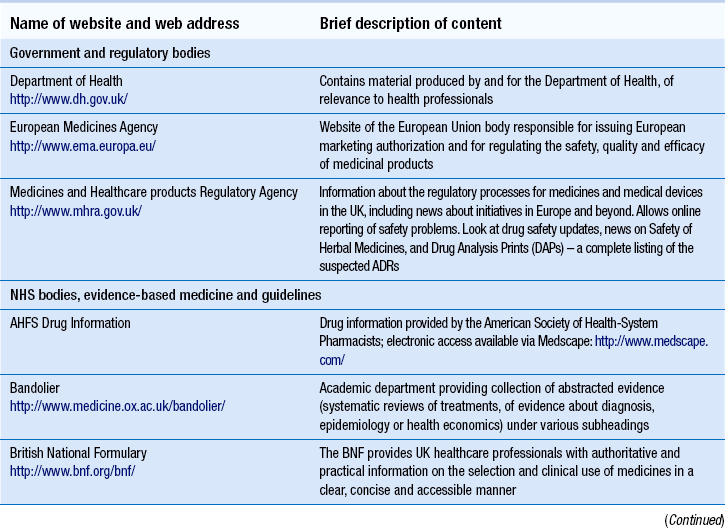

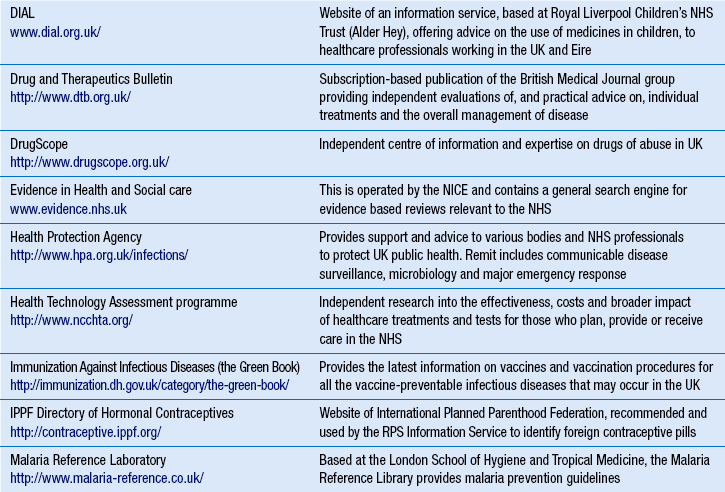

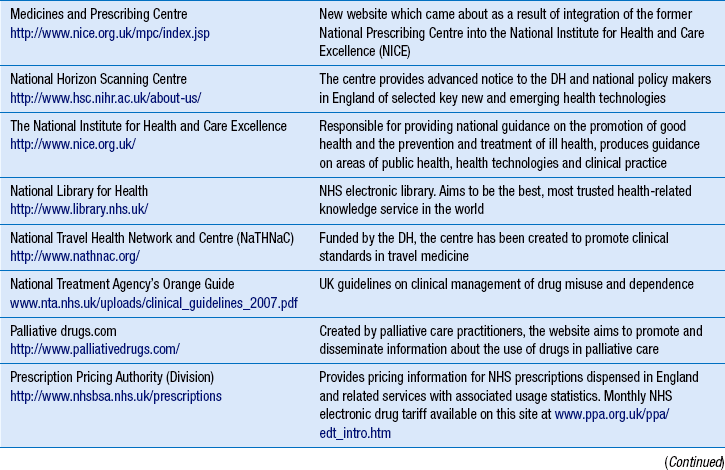

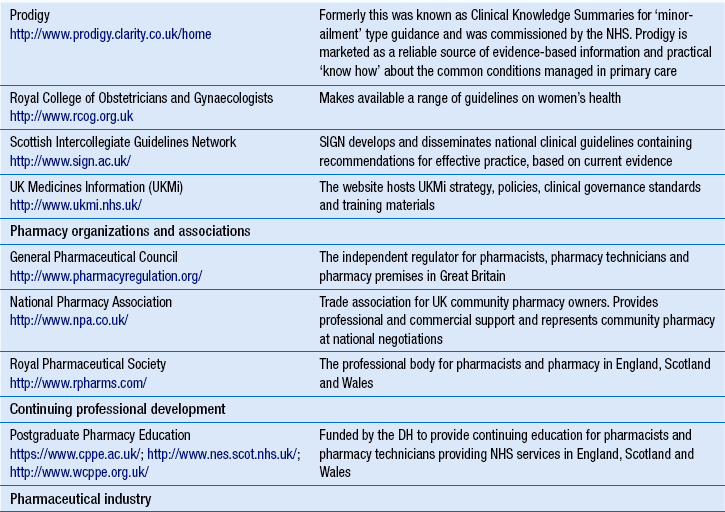

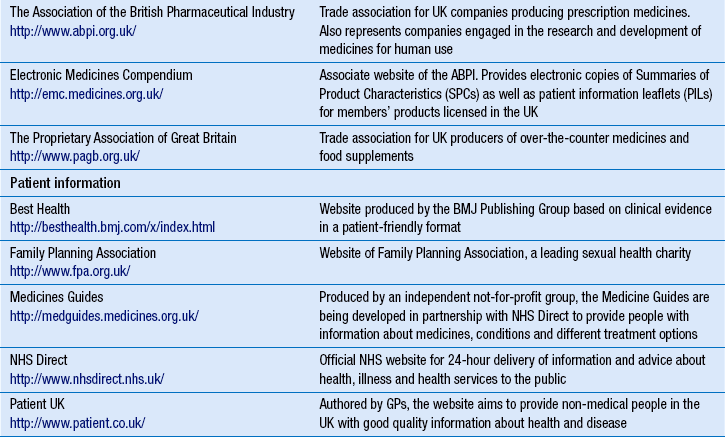

Directory of useful websites

Table 16.1 provides a list of some of the established health-related websites, although web addresses or pathnames can change or more useful sites can be created. To help order the directory, similar websites are grouped together. The list is not exhaustive and it should be used as a starting point.

Bookmarking

Once a number of relevant websites have been identified and authenticated for inclusion, these can be stored as a saved text file, using hyperlinks to connect each typed URL address in the document to the address bar on the browser and therefore the desired web destination. Hyperlinks are, usually, in a different colour to the rest of the document or are underlined and can be activated by a mouse click.

Hyperlinks provide a way of finding and bookmarking useful websites. Websites normally have a directory of related websites as ‘links’.

An accepted method of bookmarking relevant pages is to use an internet browser with functions such as ‘Favourites’. A marker points at a website which then enables the user to quickly return to that site without having to remember and type in its URL. Browsers usually offer the facility for organizing the bookmarks into folders and subfolders.

There are also innovations such as the social bookmarking website http://delicious.com/, which provides a means of storing personal bookmarks online instead of within the browser, thus enabling bookmark information to be accessed and shared online.

Searching the internet

Accessing a list of useful websites and following the links therein is one approach to finding information on the internet, but is unlikely to be productive unless the query falls specifically within the remit of a known website. With the web containing over 40 billion pages, at some point it is likely that the website containing the required information is simply unknown to the user and it has not been possible to reach it via ‘browsing’ the internet. For that reason, it is essential to have a good appreciation of internet search options.

Commercial search engines

The internet is not controlled or owned by any individual or organization, and plays host to a multitude of material with limitless authors. The manner in which information is stored on the internet is quite unique. There is no central catalogue of the internet.

A variety of websites concentrate on providing internet search facilities. Some are set up as web portals with the aim of providing a complete resource for everything on the web that they consider to be worthwhile. Portals display their own editorial material, news headlines and other up-to-date information, as well as links to commercial partners and paid advertisements. They are good for general or commercial information but most will fail to identify websites for non-profit organizations, such as the NHS. Web portals also provide a search facility. Search engines attempt to search all the text on all the pages of the web. Software seeks out and indexes web pages, storing the results in sizeable databases. When a user types a query, the search engine searches its database for pages that contain words matching the query and displays the results as a list of links (Box 16.3). Each search engine ranks results according to its own criteria and so different search engines can give different results for the same query.

Effective use of search engines

Before beginning a new search, the user should take time to consider what they already know, knowledge gaps and information required. It is advisable to have a plan that focuses the search. The user should select a set of keywords that best reflect the information need and narrow the search to a particular subject or topic. Results should be compared to the original information need. If appropriate material is found on the first page of the search then the activity need go no further. It is important to know when to stop searching, especially when there is limited time.

When, however, the results do not match the information need, it is advisable to pause and reflect. The user should consider what they are searching for; can the search be refined by changing keywords, perhaps adding, taking away or replacing them? The keywords must match the information needed. One additional approach is to subtract any redundant words from the search query. These include words such as ‘a’, ‘an’, ‘the’, ‘and’, etc. It might also be helpful to rearrange the search so that the more important search terms are placed first, to give more influence when the results are ranked.

Boolean terms for academic databases are described in more detail later. In Google™, the Boolean terms AND and NOT are not used in the traditional sense. Google™ will automatically link a series of words using the AND operator, instead of NOT, to eliminate a word from the results. A space should be left after the word that is needed and a minus sign (−) should be typed immediately before the word that is to be excluded. The term OR can, however, be used in Google™ by typing OR between the words. Google™ can also be forced to link words by using a plus sign (+), especially where one of the words is a common word that might normally be ignored. The search engine can also be asked to search for a string of words in a particular order, e.g. ‘Community-acquired pneumonia’. The user should examine search engine tools to make the most of any advanced features. Sometimes, the search engine itself may need to be changed or the basis of the search re-examined.

It is important to recognize that search engines do not necessarily index the whole of each document they retrieve. A search engine may upload each page in full, but it may only use the first few thousand characters for indexing and so vital information further down the web page will escape being indexed. Where a search engine does return a link to a site, sometimes it is not possible to access the content if the user is behind their organization’s ‘firewall’. Search engines do not locate everything on the web first-hand. It might be that a general search engine finds another site that is a more appropriate starting point, for example a health services directory. In that way, the search is narrowed automatically.

Some public web pages are protected from search engines through use of a file (robots.txt) that blocks access to the robot. This normally relates to personal, sensitive, interactive, timely or premium (subscription, or paid for) content. Another place that search engines cannot always reach is commercial data collections, or collections of valuable, copyrighted content, such as subscription-based academic journal databases and other specialized databases, information in professional directories, patents and news articles.

Assessing the quality of information on the web

There is no restriction on what is placed on the web or by whom. There is certainly no process of editorial or peer review for material placed on the web. Apart from the Advertising Standards Authority, which recently gained the authority to regulate marketing material on UK websites, no UK organization is currently responsible for regulating health- and medicines-related information on the internet. Under these conditions, there is always the danger that an internet site contains incomplete, inaccurate, irrelevant, obsolete or even hoax information. As a result, the utmost care should be taken in making use of health-related information from the internet. An informed approach must include a system for evaluating the quality of the information found against the intended use of that information. Factors listed below can all affect the quality of an information source; they are not mutually exclusive and must be considered in combination (see Table 16.2).

Table 16.2

Evaluating the quality of an internet-based website for health- and medicines-related information

| Activity | Purpose |

| Follow internal links | To find out as much as possible about the resource, e.g. the scope of the material; the intended audience and coverage; the origin of the information; who is responsible for the content; involvement of others in the production of material; any access restrictions |

| Analyse the URL | To find out where the information comes from and to judge if they are qualified to provide the information, e.g. the individual or group that has taken responsibility for the website |

| Examine the information contained | To find out the subjects and types of materials covered; comprehensiveness of coverage; notable omissions; notable indicators of accuracy; editorial procedures; research basis to the information; creation date; the frequency and/or regularity of any updating |

| Consider the presentation | To find out if the resource is frequently unavailable or noticeably slow to access; any access restrictions (e.g. by geographical region, hardware/software requirements); whether there is a registration procedure and whether this is straightforward; whether the available content is free or subscription based; the copyright statement and copyright restrictions; whether the site is particularly difficult or easy to use; presence or absence of user support facilities and/or help information |

| Obtain additional information | To find out if an individual or group has taken responsibility for the website; whether they are qualified to provide this information; whether the resource is well known (e.g. recommended via links), reviewed and/or heavily used |

| Compare with other similar websites | To find out if a resource is unique in terms of content or format and any differences between mirror and original sites for the same materials |

Context of the website

The user must identify the scope of the website (what it aims to cover), as well as the intended audience (at whom the information is aimed). Knowledge of URL nomenclature helps to contextualize the information found. For example, information on a product licensed in the USA may not be applicable in the UK market.

The user should also assess the authority and reputation of the author(s) and website providing the information. Authority is based primarily on the perceived knowledge, qualifications and expertise of the author(s) as well as the reputation of the parent organization.

Reputation is created when others endorse the value of a website by using it. The user should consider and draw inferences from the popularity of a website. Establishing the provenance of a source can also help assess its potential quality, for example, knowing when the website was first established. A final consideration is how the website compares with rival material and whether it offers anything unique.

Content of the website

The reputation and popularity of a site, or even the expertise of an author, do not guarantee the quality of content. Here, the key questions relate to the accuracy, currency and coverage of the health-related information found. The likely accuracy of a website is inextricably linked to its perceived authority. Users will rely on a number of markers to judge accuracy, including: whether the information has been edited or peer reviewed; the basis of the information; possible bias and the overall impression provided by a website.

It is important to find out when the information found was produced (and updated) and whether the frequency of updates can provide up-to-the-minute information. A final consideration is the coverage provided by material found on the website. The relevance of this factor depends very much on the user’s information needs. The quality of coverage includes the comprehensiveness of a resource and links to further information.

Format of the website

As well as a marker of immediate usefulness, the format of a website is important when considering its potential use. Three distinct factors can be considered here; accessibility, presentation and usability. In relation to accessibility, some resources are not available to the public; may require special software or hardware for accessing content; require subscription; some websites contain material with copyright restrictions; and some are not written in English. Also, overwhelming demand, server unreliability and heavy use of graphics can all impede access to an otherwise good website.

Most probably, users will intuitively form an impression of a website based on its design and interface. This might be based on such factors as sensible use of hypertext links and other navigation aids, indexes, menus and search facilities. Usability is, of course, related to accessibility and presentation. A good website should allow the user to navigate the site and find the required information. Another important consideration, nowadays, is the presentation of a website on mobile devices.

User-generated content

Recent times have seen an upsurge in what is known as user-generated content on the internet. Users have no difficulty publishing their output if they can find a way to put it on the internet, where it is instantly available to a global audience and where it can be found by search engines. Many kinds of user-generated content exist. A particular example is a wiki, a type of website that allows the visitors to easily add, remove, edit and change some available content, sometimes without the need for registration. An important example is Wikipedia. This is a vast online reference work that is written and edited by its users. It can be changed at will by anyone, so cannot be an authoritative reference source. Yet, because it is easily accessible and provides wide coverage, students will (erroneously) use websites such as Wikipedia in preference to good, authoritative textbooks.

The sequence of information

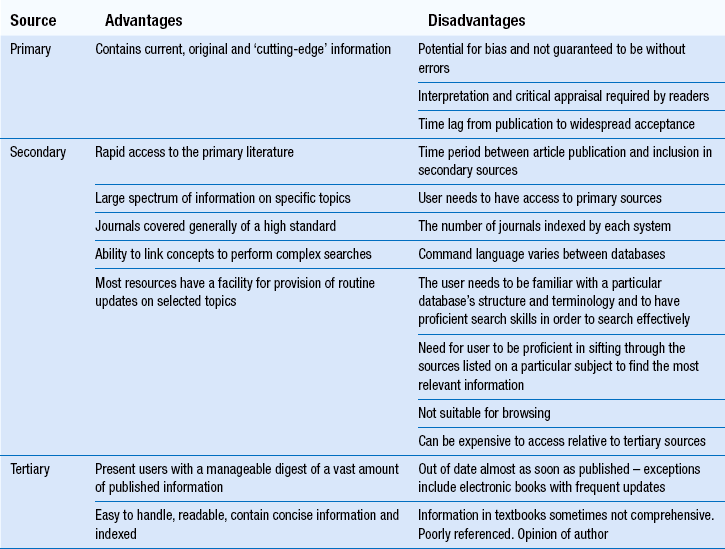

Information is often repackaged, re-versioned and developed for different audiences and different uses. Health-related information has by tradition been categorized on the basis of an accepted chronology of inception and development. As such, information is labelled, as belonging to a primary, secondary or tertiary reference source. Primary reference sources are those in which new information is published, usually in the form of research, such as papers in biomedical journals. Secondary reference sources, such as academic databases, act to index and/or abstract literature from primary sources. Tertiary sources provide an overview of a topic in a condensed readable form and include textbooks, drug compendia and formularies; with authors drawing on the primary literature for material. An awareness of this can help pharmacists identify where to look for the most appropriate type of information for their particular information needs (see Table 16.3).

Primary reference sources

The primary literature is the basis of the information hierarchy. The term primary literature is used in essence to refer to original publications and normally entails research papers published in journals, although it can include other material. Preliminary research findings are sometimes presented at conferences and a record of these is normally published in the conference abstract book or the conference website.

The publication of research papers

Primary research enters the public domain once the researchers write and submit their work to a primary reference source, such as a journal publication. Authors aim to create accurate, clear and easily accessible reports of their studies that can be considered for publication. Each journal is headed by an editor who is the person responsible for its entire editorial content, although some journals also have an independent editorial advisory board to help establish and maintain editorial policy.

Most health-related research papers based on empirical methods, such as observational and experimental studies, follow a conventional style, such as that advocated by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). The text of these papers is usually divided into sections with the headings: Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion, and sometimes Conclusion. This so-called ‘IMRAD’ structure is not an arbitrary publication format, but rather a direct reflection of the process of scientific discovery. Specific research designs have additional reporting requirements (see Table 16.4).

Table 16.4

Reporting guidelines for specific study designs

| Initiative | Type of study | Source |

| CONSORT | Randomized controlled trials | http://www.consort-statement.org/ |

| STARD | Studies of diagnostic accuracy | http://www.stard-statement.org/ |

| PRISMA | Systematic reviews and meta-analyses | http://www.prisma-statement.org/ |

| STROBE | Observational studies in epidemiology | http://www.strobe-statement.org/ |

| MOOSE | Meta-analyses of observational studies in epidemiology | http://www.consort-statement.org/resources/downloads/other-instruments/ |

Abstracts and keywords merit a special note, since abstracts are the only substantive portion of articles indexed in many electronic databases and the only portion many readers read. Keywords assist indexers in cross-referencing the article. Abstracts should reflect the content of the article accurately and provide the context or background for the study, stating the study’s purposes, basic procedures, main findings and principal conclusions. The abstract should emphasize new and important aspects of the study or observations. Terms from the medical subject headings (MeSH) list of Index Medicus should be used if available or current terminology may be used.

Once a manuscript is received, a process known as ‘peer review’ is used by editors to help decide which manuscripts are suitable for their journals. Peer review also helps authors and editors in their efforts to improve the quality of reporting. A peer reviewed journal is one that has submitted most of its published research articles for outside review. However, even the ‘best’ journals contain some material that has not been refereed.

The quality of health-related journals is variable. Some journals do not adopt a peer-review process and can publish studies that are not scientifically robust. High-impact factor journals such as the British Medical Journal and the New England Journal of Medicine are considered prestigious publications. Primary reference sources of particular relevance to pharmacy practice include the Pharmaceutical Journal and the International Journal of Pharmacy Practice.

Because a primary reference source presents the paper in its original form, the reader has the opportunity to critically appraise and analyse the study or article in order to develop a conclusion on its merits.

Open access academic information

Traditionally, authors write-up their research into a paper and submit it to a journal, the paper is peer-reviewed to ensure quality, and the publisher then publishes the paper in the journal. An alternative to this model now exists in the form of open access publishing. In this publishing model, the authors make the research available on the web, via a repository or in a freely accessible journal, with authors paying for this privilege. This process bypasses the publisher completely. There are differing views on whether open access publishing is a good thing or not.

Additionally, universities in the UK are now expected to maintain an open archive of the peer-reviewed literature they have produced.

Secondary reference sources

Secondary reference sources are searchable resources that index and/or abstract from the primary literature. Some are equipped with alerting systems, which scan selected journals as soon as they are published and send summarized abstracts directly to users to help them maintain knowledge of new developments from a large pool of journals. Nowadays, the data format used for providing users with frequently updated content is known as a web feed. A recent addition to web feeds is the RSS (really simple syndication) feed, which contains either a summary content from an associated website or the full text.

Secondary reference sources are, generally, searchable electronically but may also be available in hard-copy format. Secondary reference sources include commercial academic databases, resource gateways (collections of sites that have been reviewed), as well as the more recent academic search offerings of internet search engines such as Google™, Scholar and Microsoft® Live Academic.

Academic databases

An academic database is a well-designed catalogue created and maintained by trained personnel. A database, in essence, is a set of searchable records. Nowadays, records are commonly maintained as a set of virtual cards in a computer database. Two main categories of academic database exist: the ‘bibliographic’ database contains information in summary form (the abstract); the ‘full-text’ database provides access to electronic versions of the full text of documents.

The purpose of an academic database is to enable users to systematically search the records so that specific search terms can ultimately ‘unearth’ relevant items. In the case of a scientific paper, for example, its record might contain details of title, authors, journal name, date of publication, keywords, abstract and so on. Each of these categories in a database is called a ‘field’. The record then is a collection of several fields of information about the item, be it a book or a journal article. The process of creating and adding records to an academic database is known as indexing and each record is called a citation.

Some journals ask for submitting authors to provide a set of ‘keywords’, usually corresponding to MeSH headings, for the purpose of indexing and classification. MeSH is the National Library of Medicine’s controlled vocabulary thesaurus. It consists of sets of terms naming descriptors in a hierarchical structure that permits searching at various levels of specificity. MeSH descriptors are arranged in both an alphabetical and a hierarchical structure. At the most general level of the hierarchical structure, are very broad headings such as ‘Anatomy’ or ‘Mental Disorders’. More specific headings are found at more narrow levels of the 11-level hierarchy, such as ‘Ankle’ and ‘Conduct Disorder’.

Many academic databases now exist, and although their search interfaces might at first look very different, similar tools are usually found on each. To the novice user, academic search interfaces can appear somewhat intimidating; the form looks quite complex and appears as an advanced search screen. But the format of the academic database search screen enables the user to simultaneously search for something specific (e.g. the keywords) in any of the database’s fields. Sometimes, each text entry box in the interface corresponds to a field. For example, restricting the keywords to particular fields such as the title or abstract can help focus the search by returning only those articles where the keywords are a prominent feature. A new database resource can be explored by examining helpful features that enhance efficiency (see Box 16.4).

Boolean logic defines logical relationships between terms in a search. The conventional Boolean search operators are AND, OR and NOT. They can be used to create a very broad or very narrow search (see Box 16.5). To make better use of Boolean operators, one can use parentheses to nest query terms within other query terms, as they specify the order in which they are interpreted. The information within parentheses is read first, followed by the information outside the parentheses. For example, when one enters (aspirin OR ibuprofen) AND analgesic, the search engine retrieves results containing the word aspirin or the word ibuprofen together with the word analgesic in the fields searched by default.

Once a search is conducted and results returned, most databases offer a facility for marking and exporting useful records. Users can then decide which references are worth retrieving as full papers. Most databases, traditionally classified as ‘bibliographic’, will automatically help retrieve the full paper through icons such as ‘Check for Full Text’ and ‘View Full Text’.

Citation indexes and impact factors

As referred to above, citation indexes and impact factors can be used to help assess the quality of a publication. A citation in a paper is the formal acknowledgement of intellectual debt to previously published research. It generally contains sufficient bibliographical information to uniquely identify the cited document. An obvious example of a citation is a reference listed at the end of a scientific research paper.

Citation and article counts are taken to be important indicators of how frequently current researchers are using individual journals. The impact factor in brief is the average number of times that articles from the journal published in a specific period have been cited by others. The notion, well accepted in the scientific community, is that the higher the impact factor, the ‘better’ the journal.

Box 16.6 lists some relevant databases.

Tertiary reference sources

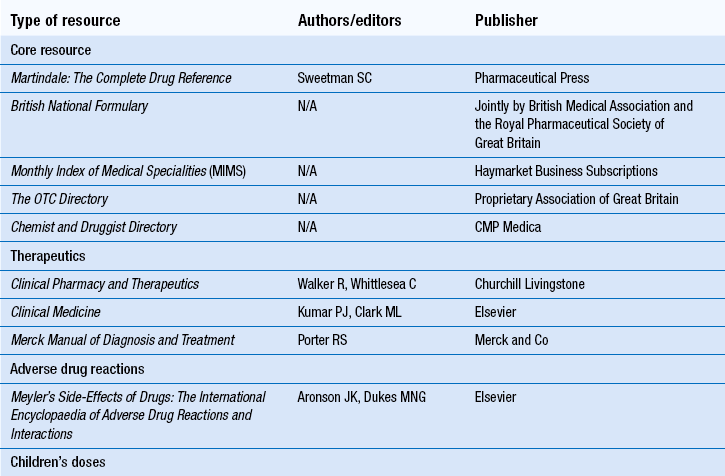

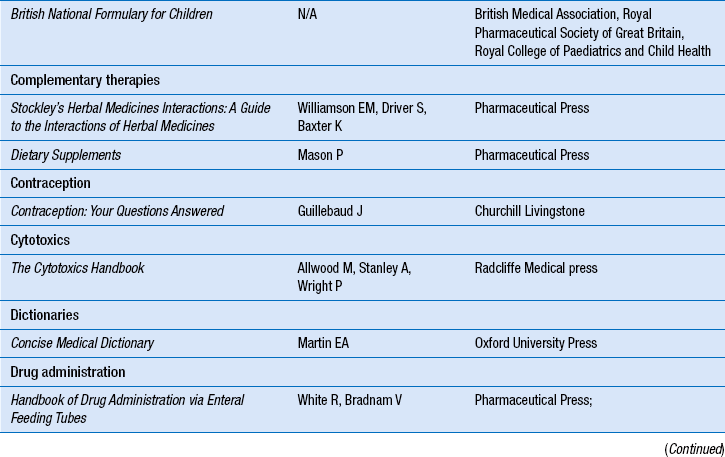

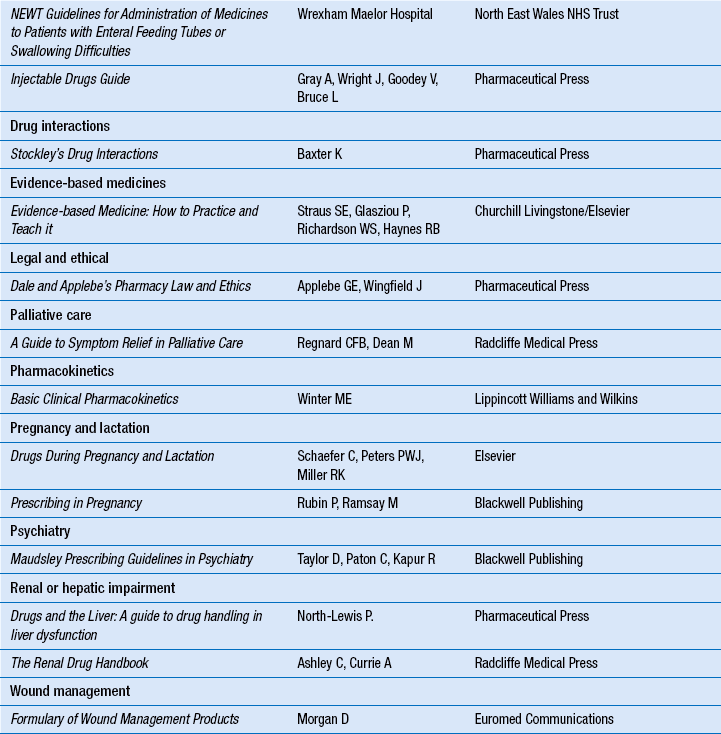

Information from primary reference sources, perhaps retrieved using a secondary reference source, can in due course come to be included in textbooks and similar tertiary publications. As mentioned above, tertiary reference sources provide an overview of a topic in a condensed readable form with authors drawing on the primary literature for material. Examples are textbooks, drug compendia and formularies. Key publications include Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference, and the British National Formulary (BNF). There are also textbooks covering specific subject areas. Table 16.5 lists some of the key tertiary drug information resources for practising pharmacists in the UK.

Table 16.5

Key tertiary drug information sources for pharmacy inquiries (further details available on publishers’ websites)

Textbooks are important for locating established knowledge or information that is not rapidly changing. The information in a tertiary source is updated against new information or knowledge documented in the primary literature only once every 3–4 years, when the book is updated and published as a new edition. Thus it can take 5 years or more for new research findings to filter into medical textbooks. In addition, most books are out of date almost as soon as they are published. Because the knowledge base in many areas of therapeutics is rapidly changing, the information contained in textbooks may be too old to be useful. This problem does not apply usually to those textbooks available in electronic full texts. Another important exception is the BNF, which is updated and published as a new edition every 6 months.

Tertiary references should be the starting point when trying to find background information on a subject. With the advent of the electronic age, it is easy to forget that information can be found quickly and easily in a book. Books are easy to handle, readable, contain concise information and are indexed.

Having said that, the reader must also be aware that the information presented in a textbook is subject to the opinion, evaluation and bias of the author. It is often assumed that what is written in a textbook must be accurate; in fact, the author(s) may not have comprehensively searched, analysed or interpreted all information. The information contained in textbooks may also not be as comprehensive as the reader would like. But, especially in comparison to user-generated websites such as Wikipedia, good textbooks are an important and reliable resource and they should not be overlooked.

Organizing and citing references

For academic work, it is often necessary to store a relatively large number of retrieved citations. It is always advisable to implement some system for keeping track of the information amassed. Bibliography management systems exist for this purpose including, but not exclusively, RefWorks, EndNote®, Reference Manager® and ProCite®. These products help users create personal databases for written academic work such as projects, reports and papers.

A number of referencing styles exist for citing retrieved information. Most academic institutions and publications have standardized requirements. Whatever style is used, accuracy, clarity and consistency are the key factors when citing information sources.

Avoiding plagiarism

As discussed, a citation is the formal acknowledgement of intellectual debt to previously published research. Therefore, referencing is a way of ensuring that due credit is given to other people’s work. While common knowledge does not need a citation or reference, taking someone’s work and not indicating where it came from is termed plagiarism and is regarded as an infringement of copyright. Higher education institutions invest in plagiarism detection software to scan assessment material.

Information services

Pharmacists are expected to be able to provide accurate, reliable, impartial, relevant and up-to-date information on a wide range of issues. A number of organizations exist to help. Unlike libraries, pharmacy information services can provide tailor-made answers to specific enquiries using analysis and interpretation. In the UK, the best known facility is the Medicines Information (MI) service based in NHS hospital pharmacies.

Most information services will work to standardized procedures to ensure quality in enquiry answering. Pharmacists working in any sector of the profession should follow similar methods. The same basic information should be collected from the enquirer (see Box 16.7). Ideally, the full manner in which enquiries are handled should be documented to provide an audit trail for quality assurance purposes. Clear and comprehensive documentation is necessary for legal and ethical reasons, in order to ascertain exactly what information was provided, by whom and what resources were used. Appropriate documentation also ensures that an enquiry can be located at a later date, to save time in dealing with future enquiries.

Medicines information services

The NHS MI service is provided by a network of 220 local MI centres based in the hospital trust pharmacy departments, as well as 14 regional centres and two national centres (Northern Ireland and Wales). The aim of MI is to support the safe, effective and efficient use of medicines through the provision of evidence-based information and advice on therapeutic use of medicines. The centres are staffed by pharmacists and technicians with clinical expertise. Centres provide an enquiry answering service, to patients and healthcare professionals, on all aspects of drug therapy. Over half a million enquiries are handled by the service each year.

In addition, the UK Medicines Information (UKMi) network produces a range of resources available through its own internet site (www.ukmi.nhs.uk/) or that of the National electronic Library of Medicines (NeLM) (http://www.nelm.nhs.uk/en/).

RPS information centre

This is based at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) in London and comprises the Library and Technical Information Service, providing a service for members. The information pharmacists can help answer scientific and technical questions relating to pharmacy practice or continuing education from members. The subject scope includes advice on the usage and availability of proprietary and other medicinal products, adverse drug reactions and interactions, and the identification of medicines from overseas.

NPA information services

The National Pharmacy Association (NPA) has an information service for members only. The department is a complete reference centre, skilled at assisting members with a wide range of pharmacy practice-related questions. In addition, the NPA information department includes a specialist library of British and foreign reference books and a range of technical CD-ROMs.

Conclusion

The ability to retrieve relevant health-related information in a timely and efficient manner is central to the practice of all pharmacy professionals. The advent of the electronic age and the expanse of available information can make information retrieval appear a daunting task. However, categorizing information, developing an understanding of search and retrieval processes, knowing who to approach for help, as well as groundwork and deliberation can all help facilitate the process.

Key Points

As part of their work, pharmacists handle a large amount of information. In order to do so efficiently they must know how to find and evaluate information sources

As part of their work, pharmacists handle a large amount of information. In order to do so efficiently they must know how to find and evaluate information sources

While the internet gives access to a vast resource, but of variable reliability, printed books still play an important role

While the internet gives access to a vast resource, but of variable reliability, printed books still play an important role

Commercial search engines give access to web pages, but to use them effectively it is necessary to understand their operators

Commercial search engines give access to web pages, but to use them effectively it is necessary to understand their operators

No search engine will give access to all relevant websites

No search engine will give access to all relevant websites

There is no control over material placed on the web, so its reliability must be evaluated by the user

There is no control over material placed on the web, so its reliability must be evaluated by the user

User-generated websites, such as Wikipedia, are less reliable

User-generated websites, such as Wikipedia, are less reliable

Information sources are classified as primary, secondary or tertiary

Information sources are classified as primary, secondary or tertiary

Primary reference sources are original research publications which normally follow a conventional layout style

Primary reference sources are original research publications which normally follow a conventional layout style

Secondary sources are searchable indices or abstracts which lead to primary sources

Secondary sources are searchable indices or abstracts which lead to primary sources

Keywords are often used for searching, especially in academic databases

Keywords are often used for searching, especially in academic databases

Tertiary sources present an overview of a topic

Tertiary sources present an overview of a topic

Textbooks are quick and easy to use, but are inevitably out of date and may be subject to bias or be incomplete

Textbooks are quick and easy to use, but are inevitably out of date and may be subject to bias or be incomplete

NHS information services are based, mainly, in hospital pharmacies in the UK

NHS information services are based, mainly, in hospital pharmacies in the UK

The UK Medicines Information (UKMi) network produces resources which are available through its website

The UK Medicines Information (UKMi) network produces resources which are available through its website