Sleep and Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a condition of recurrent unprovoked seizures, whereas a seizure is a paroxysmal event as a result of sudden excessive discharge of cerebral cortical neurons. There is a reciprocal relationship between sleep and epilepsy: Sleep triggers seizures, and seizures disrupt sleep architecture. The estimated frequency of nocturnal seizures varies between 7.5% and 45%, reflecting the heterogeneity of such seizures. Some types of epileptiform syndromes are prone to recur exclusively or frequently during sleep. Examples of predominantly sleep (nocturnal) seizures include the following: benign partial epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes or occipital paroxysms; nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy (this includes nocturnal paroxysmal dystonia, paroxysmal arousals, and episodic nocturnal wanderings); autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy; juvenile myoclonic epilepsy; generalized tonic-clonic seizures on awakening; nocturnal temporal lobe epilepsy (a subgroup of partial complex seizure of temporal lobe origin); tonic seizure (as a component of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome); epilepsy with continuous spike and waves during non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep (CSWS); and Landau-Kleffner syndrome, probably a variant of CSWS.

The spectrum of nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy includes four major manifestations characterized by stereotyped motor behavior arising out of NREM sleep lasting usually for less than a minute with brief postictal confusion and occurring often in clusters ![]() (see Video Vignette 14):

(see Video Vignette 14):

1. Paroxysmal arousals and awakenings

2. Hypermotor syndrome with choreoathetoid, ballismic, bipedal, bimanual, cycling movements (originally termed nocturnal paroxysmal dystomia)

3. Asymmetric tonic and dystonic posturing

4. Epileptic nocturnal wandering resembling agitated somnambulism

Ictal electroencephalograms (EEGs) are normal in more than 50% of patients, and EEGs may not show epileptiform spikes or sharp waves in the frontocentral region. About 25% to 30% are drug resistant but may show good response after surgical treatment. The most common histological abnormality is Taylor-type focal cortical dysplasia. An interesting observation is a history of high frequency of arousal parasomnias in the patients and their relatives.

Most interictal epileptiform discharges are triggered during NREM stages 1 and 2 but occasionally in stage 3 sleep. In epileptic patients NREM sleep acts as a convulsant, causing excessive synchronization and activation of seizure in an already hyperexcitable cortex. In contrast, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep generally behaves like an anticonvulsant because of inhibition of thalamocortical synchronizing mechanism and tonic reduction of interhemispheric impulse transmission through the corpus callosum. Overnight polysomnography (PSG) using multiple channels of EEG recording combined with simultaneous video recording is the single most important test for evaluating nocturnal seizure. For recognition of epileptiform patterns in the EEG and CSWS see Chapter 2. In this section of the atlas we provide several case vignettes along with overnight EEG and PSG segments showing characteristic patterns (Figs. 11.1 to 11.21).

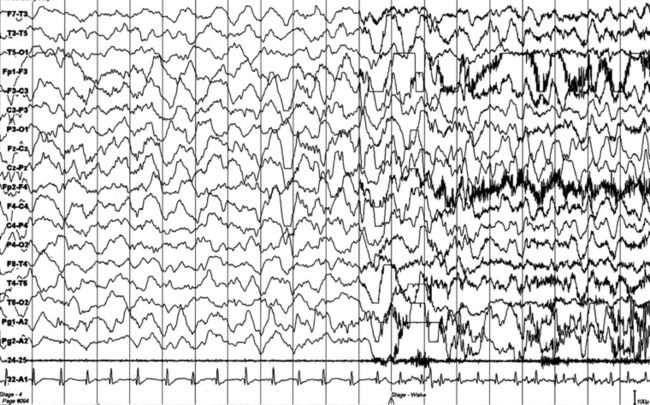

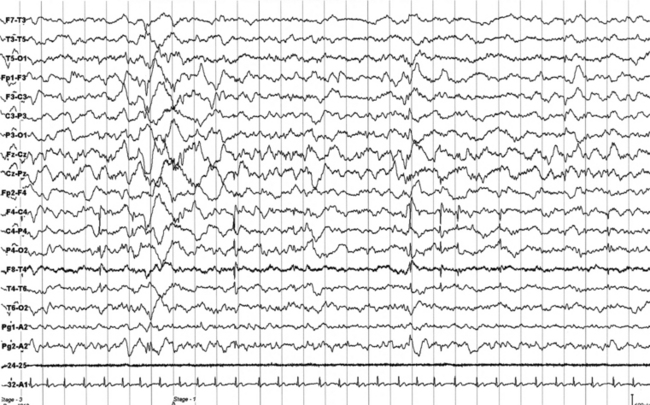

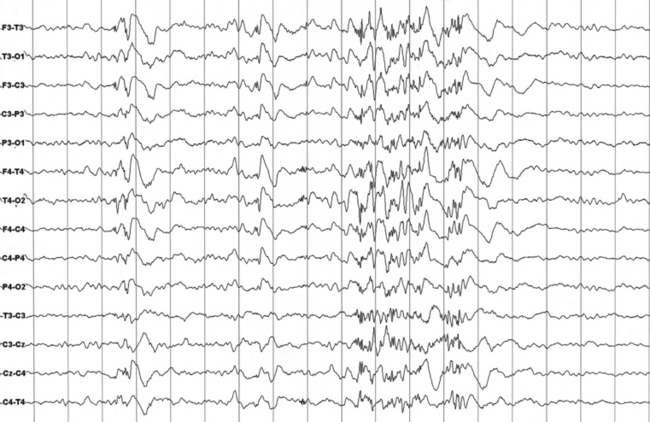

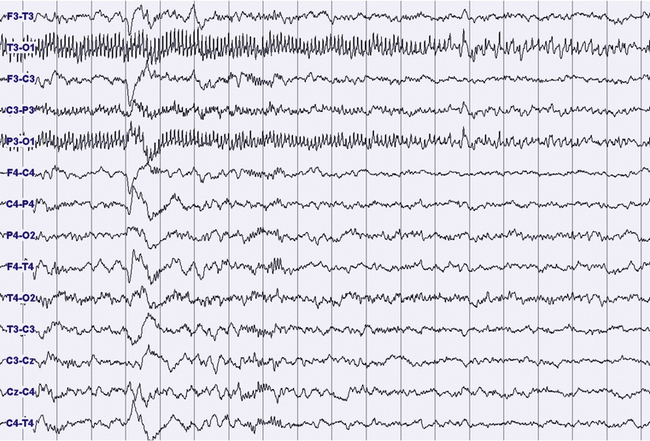

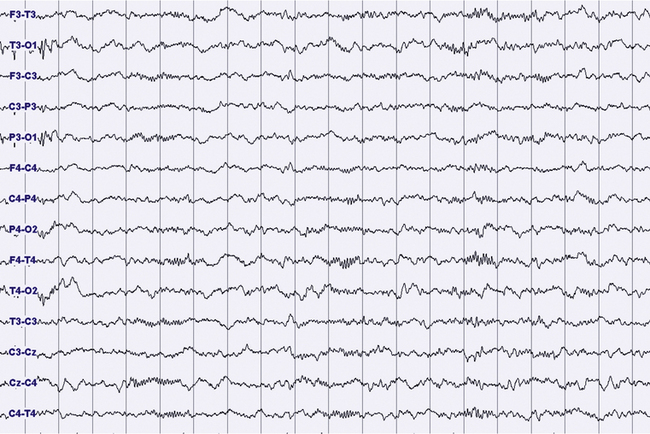

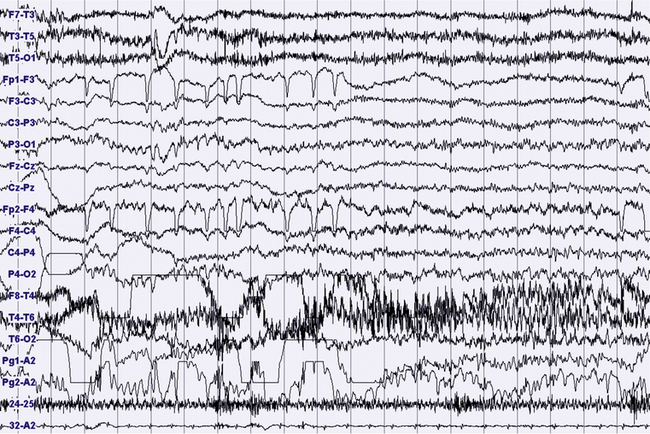

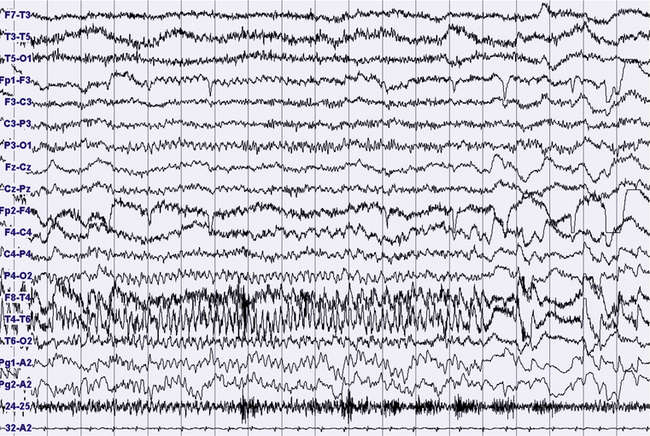

FIGURES 11.1 TO 11.3 Polysomnographic (PSG) sequence of a nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy seizure in a 10-year-old boy with onset of episodes during sleep at the age of 6½ years and characterized by arousal with sudden elevation of head and trunk, sitting, fearful expression, sometimes jumping ahead or ambulating, and rare similar episodes during wakefulness. Wake electroencephalogram (EEG) is normal, and sleep EEG shows rare sharp waves on Fz-Cz channel. Duration, less than 15 to 20 seconds, sometimes 30 seconds for prolonged episodes; frequency, 7 to 10 per night, with similar morphological characteristics and stereotypical features; good response to carbamazepine. The montage of PSG is EEG (top 16 channels), ROC (Pg 1-A2), LOC (Pg 2-A2), submental electromyogram (24-25), and electrocardiogram (32-A1). Epoch is 20 seconds.

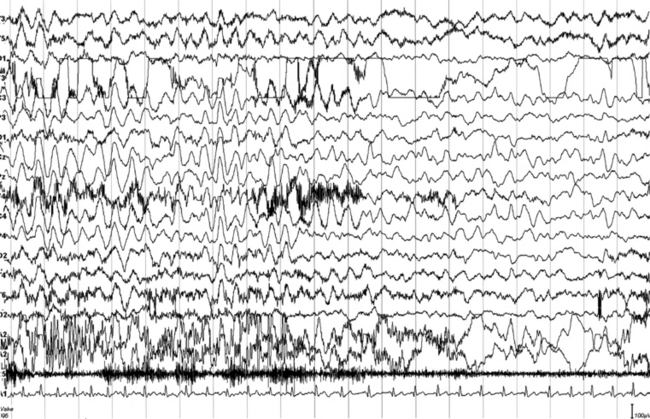

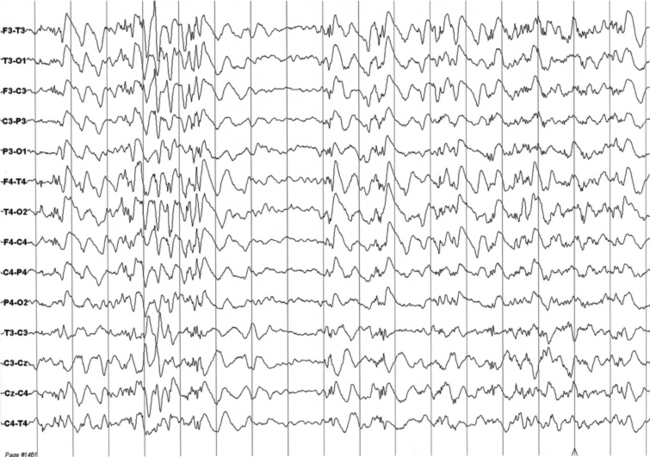

FIGURES 11.4 TO 11.6 A seizure during sleep probably arising from frontal lobe emerging from slow wave sleep (SWS) and characterized by awakening followed by choking sensation. We recorded two episodes in that night. PSG shows an awakening from SWS followed after 10 seconds by an epileptiform discharge probably starting from frontotemporal leads (right), spreading bilaterally in the electroencephalogram (EEG). The patient’s episodes had been misdiagnosed as panic attack in the past. He is a 23-year-old man whose episodes started at 12 to 13 years of age. There is no family history of epilepsy. The montage is only EEG and electrocardiogram, and we recorded the episode during a morning video-PSG after sleep deprivation the night before.

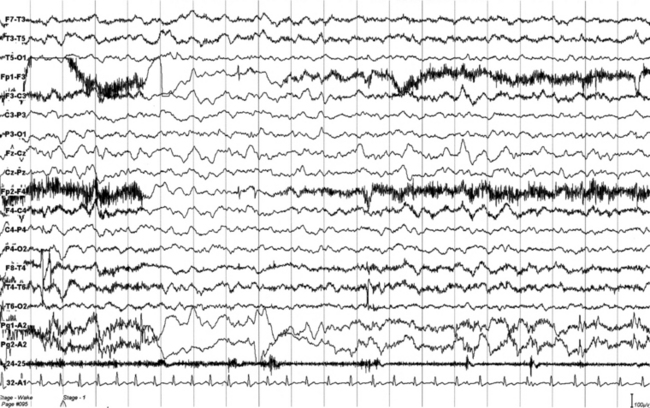

FIGURES 11.7 AND 11.8 Interictal epileptic paroxysms originating from right frontal region in a 9½-year-old boy with episodes of parasomnia-like behavior during sleep, starting at age 6, and clinically characterized by eyes opening, but without contact, sometimes crying or sleeptalking (stereotyped, frequency of two per week), and rare episodes of sudden arising in the bed, screaming, and pavor-like behavior (two to three episodes). He has a family history of parasomnia-like episodes. The montage is similar to that in Figures 11.1 to 11.3. Note interictal spikes at C4 and T4.

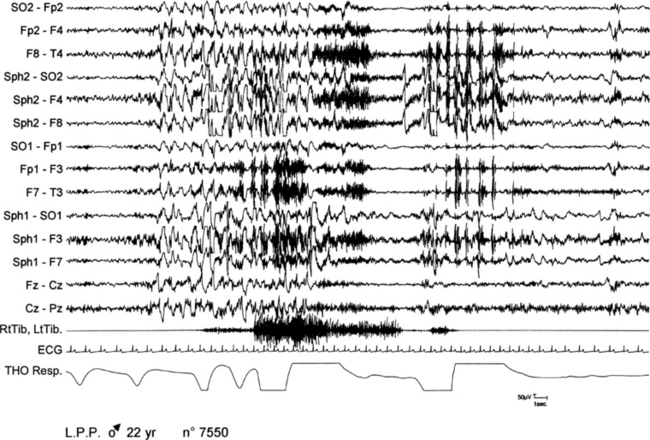

FIGURE 11.9 Paroxysmal arousals in nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy.

A 22-year-old woman presented with epileptic seizures only during nocturnal sleep or a few minutes after waking up. Motor manifestation consisted of raising her arms and stretching her legs with jerks and dystonic postures of the four limbs. Seizures recurred one to two times per night. Polysomnographic (PSG) recordings show a paroxysmal arousal arising from stage II of sleep during which the patient presents a sudden abduction and extension of lower limbs with an abduction of upper limbs, tachycardia, and modification of respiration. Ictal electroencephalogram is characterized by a paroxysmal activity of diffuse slow waves. SO, Supraorbital electrode; Sph, sphenoidal electrode; RtTib, LtTib, right and left tibialis anterior; THO Resp, thoracic respiration.

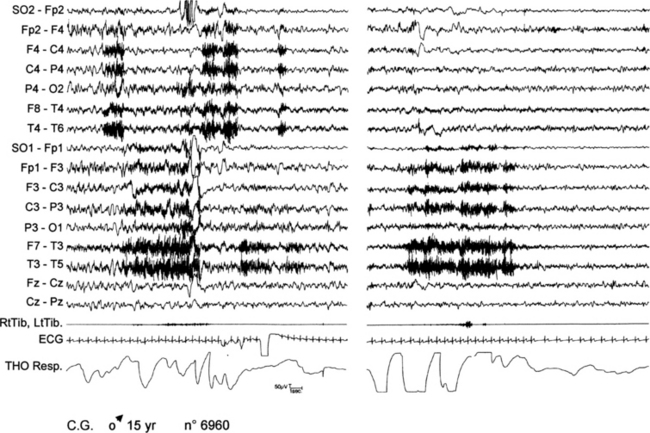

FIGURE 11.10 Two paroxysmal arousals in nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy.

A 15-year-old boy presented with nocturnal seizures since age 13, during which he suddenly opened his eyes and stretched his four limbs with a twist of upper limbs and oral automatisms. Sometimes he jumped out of bed and walked around with repetitive gestural automatisms. More than one seizure appeared nightly, almost every night. The figure shows the polygraphic recording of two different arousals in the same night arising from non–rapid eye movement sleep. Note the absence of clear-cut electroencephalographic abnormalities. During both episodes, tachycardia and modification of respiration are evident. SO, Supraorbital electrode; RtTib, LtTib, right and left tibialis anterior; THO Resp, thoracic respiration.

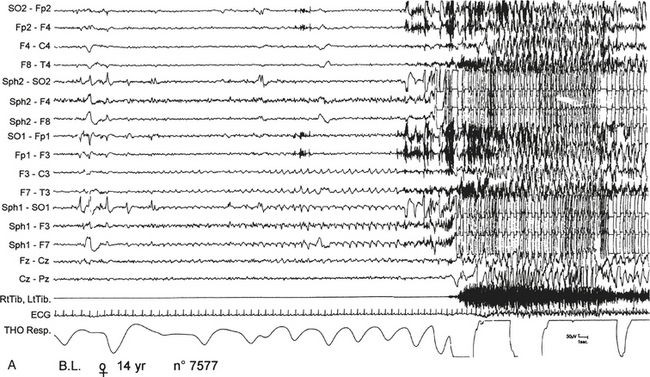

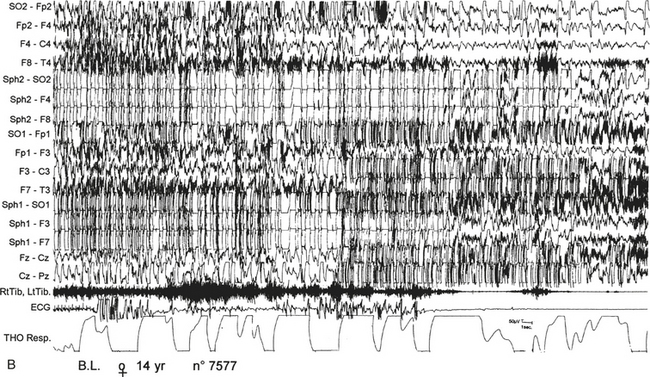

FIGURE 11.11 Nocturnal paroxysmal dystonia in nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy.

A 14-year-old girl presented with nocturnal episodes since age 12, characterized by head rising and complex motor automatism involving both legs, arms, and trunk with dystonic postures. Seizures recurred several times a night, two to three times per month. Video-polysomnographic recordings showed that at the beginning of the seizure the patient opens her eyes, presents a deep inspiration while raising her head, then abducts her hyperextended upper limbs and presents rhythmical movements of limbs and trunk with back arching. A, Polygraphic tracing shows this seizure arising from sleep stage II. The motor manifestation is preceded for 10 to 15 seconds by repetitive sharp waves on left anterior electroencephalographic (EEG) channels. B, then paroxysmal EEG activity is almost completely masked by muscle artifacts. During the seizure, tachycardia and modification of respiration occur. SO, Supraorbital electrode; Sph, sphenoidal electrode; RtTib, LtTib, right and left tibialis anterior; THO Resp, thoracic respiration.

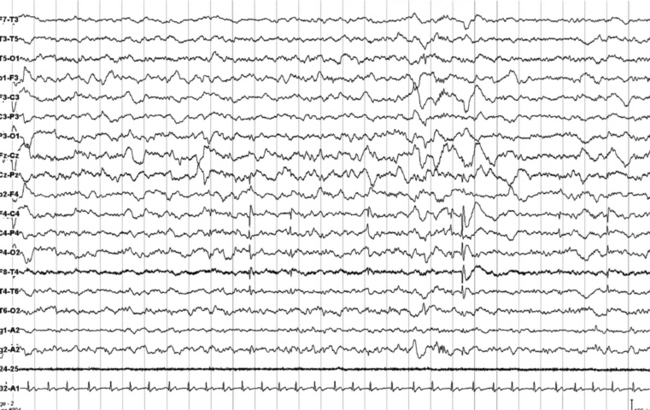

FIGURES 11.12 AND 11.13 Stage N2 sleep with generalized spike and waves and multiple spike and wave bursts during a 24-hour ambulatory electroencephalographic (EEG) recording. This is a 24-year-old woman with a drug-resistant partial idiopathic epilepsy, with psychomotor seizures (alteration of consciousness and flexion of the head with automatisms and sometimes secondary generalization). The seizures appear in cluster. EEG during wake shows rare generalized paroxysms (slow spike and wave) with left hemispheric prevalence. EEG during sleep shows activation of generalized epileptiform discharges as described earlier, both during stage N2 (Figure 11.12) and stage N3 (Figure 11.13).

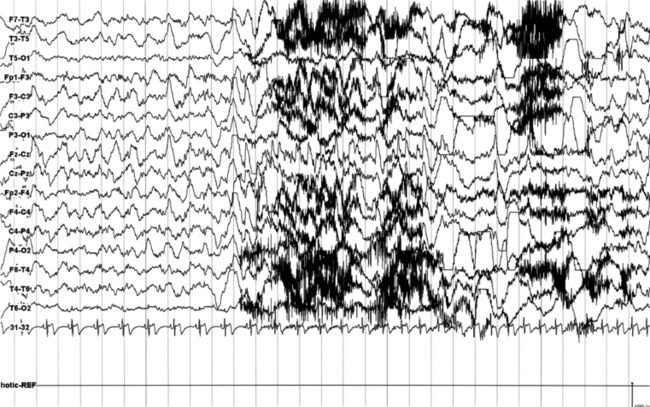

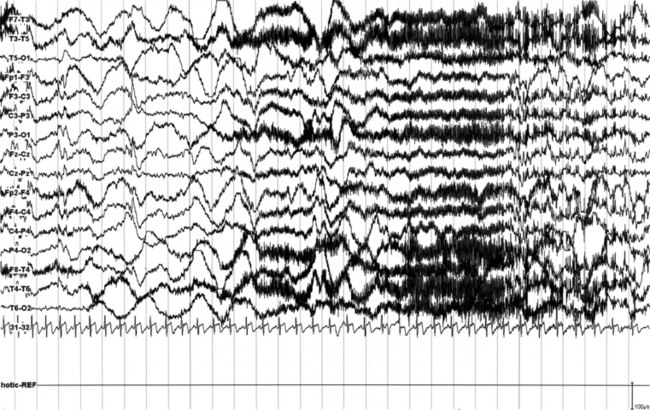

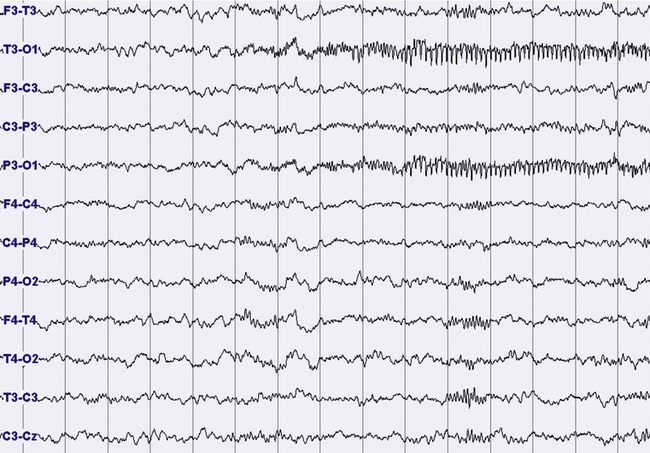

FIGURES 11.14 TO 11.17 Electrical focal (occipital) seizure.

A 14-year-old boy with a history of rare nocturnal secondary generalized seizures, started at 12 years of age. During sleep five focal electrical seizures have been recorded, all emerging from non–rapid eye movement sleep. The seizures started from the occipital leads with a fast sharp activity at 7 to 8 Hz (Fig. 11.14), increasing in amplitude for around 20 second (Figs. 11.15 and 11.16), followed by a decrease in frequency and a rapid ending, without sign of arousal during the same stage of sleep (N2) (Figs. 11.16 and 11.17). No evident clinical findings during the seizure. Some interictal epileptic isolated discharges in both the temporo-occcipital leads. Montage: electroencephalogram.

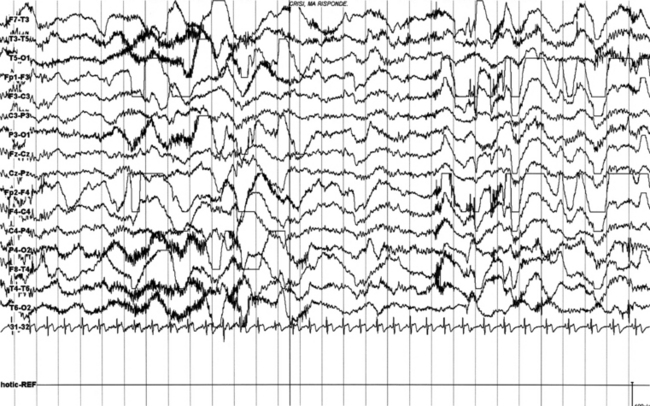

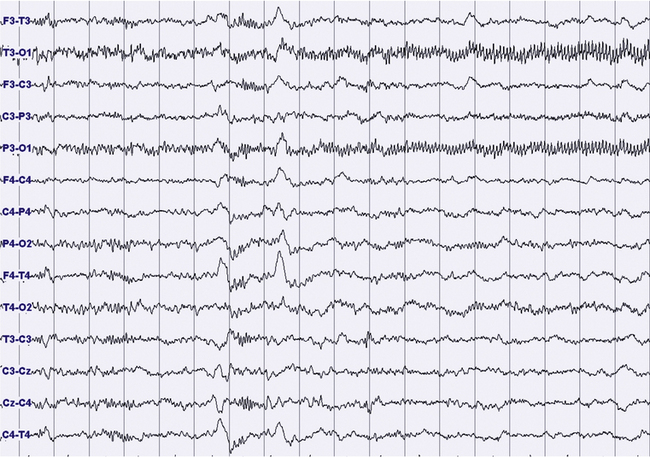

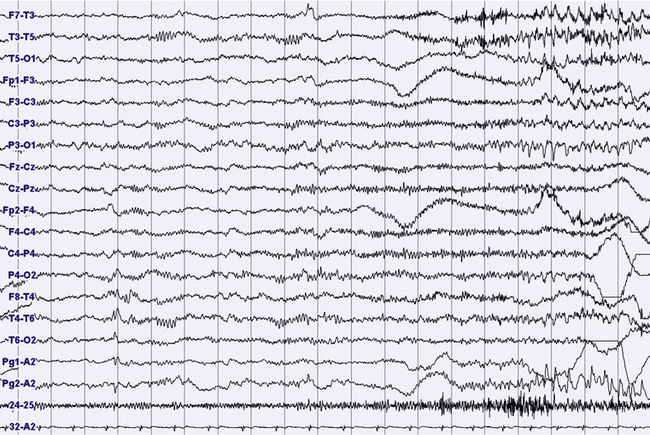

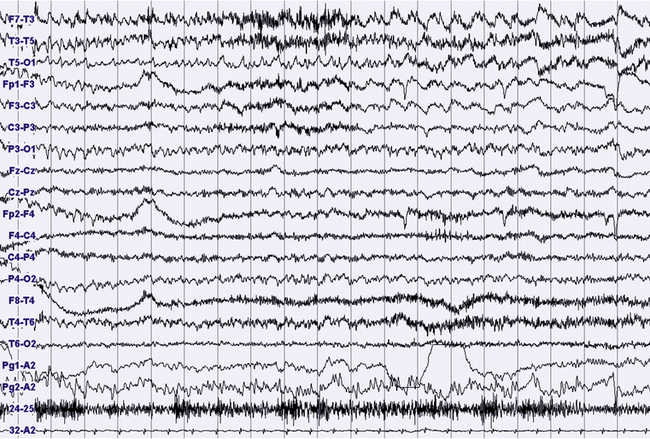

FIGURES 11.18 TO 11.21 Nocturnal focal seizure.

A 53-year-old woman with nocturnal seizures since age 20, apparently focal with secondary generalization, caused by a neoplastic lesion (pylocytic astrocytoma surgically removed) in right frontotemporal lobes with a malacic residual lesion. The patient is taking the antiepileptic drugs gabapentin, lamotrigine, and clonazepam. The figures show an epileptic focal seizure emerging from N2 stage and starting in left hemisphere (temporal) with a depression of electroencephalographic (EEG) activity in frontotemporal leads, followed by theta activity with spikes (Fig. 11.18), and slowing of activity diffused to the posterior zone and to the contralateral temporal leads (Fig. 11.19). In the next figures (Figs. 11.20 and 11.21) rhythmical and high-amplitude spike and wave complexes are seen on the right temporal leads for almost 50 seconds. Clinically the seizure starts with moaning, opening of the eyes and fearful expression, sudden elevation of head and trunk, and clonic-dystonic movements in the right arm. Note left interictal temporal spikes in Figure 11.18. Polysomnographic montage: EEG ( top 16 channels), ROC and LOC (Pg1-A2 and Pg2-A2), submental electromyogram (24-25), and electrocardiogram (32-A2).

Bazil, C., Malow, B., Sammaritano, M. Sleep and Epilepsy: The Clinical Spectrum. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science B. V; 2002.

Chokroverty, S., Montagna, P. Sleep and epilepsy. In Chokroverty S., ed. : Sleep Disorders Medicine: Basic Science, Technical Considerations and Clinical Aspects, 3rd ed., Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier, 2009.

Dinner, D. S., Luders, H. O. Relationship of epilepsy and sleep: an overview. In: Dinner D. S., Luders H. O., eds. Epilepsy and Sleep: Physiological and Clinical Relationships. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001:2–18.

Malow, B. Paroxysmal events in sleep. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2002; 19:522–534.

Provini, F., Plazzi, G., Tinuper, P., et al. Nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy: a clinical and polygraphic overview of 100 consecutive cases. Brain. 1999; 122:1017–1031.

Scheffer, I. E., Bhatia, K. P., Lopes-Cendes, I., et al. Autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy: a distinctive clinical disorder. Brain. 1995; 118:61–73.