CHAPTER 89

Adhesive Capsulitis

CHARLES L. GETZ, MD AND JASON PHILLIPS, MD

CRITICAL POINTS

▪ Capsule irritation precedes motion loss.

▪ Passive range of motion and active range of motion are symmetrical in all stages.

▪ Loss of motion is initially in external rotation and then progresses to loss in all planes.

▪ Treatment is aimed at decreasing inflammation.

▪ For patients with residual motion loss, manipulation with arthroscopic release can be effective at restoring function.

Frozen shoulder is poorly defined as a clinical condition with painful, restricted active and passive range of motion. Frozen shoulder syndrome was first described by Duplay1 in 1872; however, it would not be until 1934 in the classic article by Codman2 that the term frozen shoulder would be officially introduced into the orthopedic literature. In 1945, Neviaser3 suggested that “the essential pathology is a thickening and contraction of the capsule which becomes adherent to the humeral head.” With these findings, Neviaser suggested that a more descriptive term based on the pathologic features be used, coining the term adhesive capsulitis.

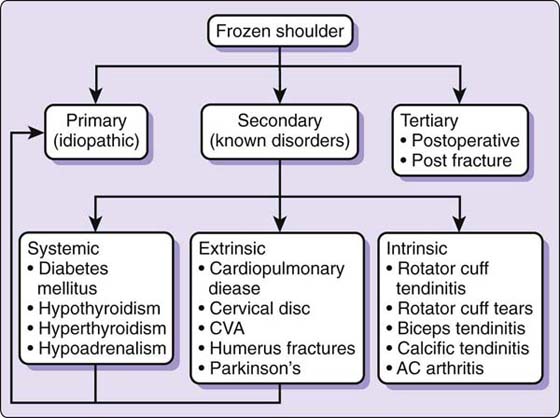

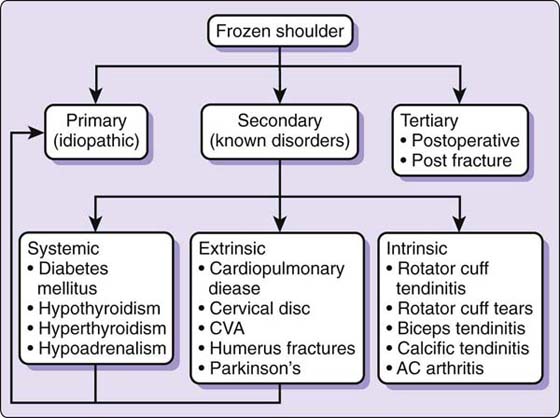

Lundberg4 further classified adhesive capsulitis into primary (idiopathic) and secondary adhesive capsulitis, i.e., that which can be attributed to a known intrinsic, extrinsic, or systemic cause. Cuomo and Holloway5 recently defined primary adhesive capsulitis as an unexplainable loss of active and passive shoulder motion for which no intrinsic shoulder pathology can be identified. Secondary adhesive capsulitis is that which is associated with a known cause (Fig. 89-1). Three classes of secondary adhesive capsulitis exist: intrinsic, extrinsic, and systemic. The intrinsic class includes rotator cuff pathology, biceps pathology, glenohumeral arthritis, and acromioclavicular joint arthritis. The extrinsic class includes proximal humerus fractures, cervical spine disease, stroke, and Parkinson’s disease. The systemic class includes hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, hypoadrenalism, and most notably diabetes mellitus, which can also result in adhesive capsulitis.

Figure 89-1 Proposed pathways for the development of adhesive capsulitis. (Copyright © 2007 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Iannotti JP, Williams GR Jr, eds. Disorders of the Shoulder: Diagnosis & Management, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007.) AC, acromioclavicular; CVA, cerebral vascular accident,

Pathology

The glenohumeral joint is an unconstrained joint with a capsular surface area that is almost twice that of the humeral head. Such a large capsular volume is necessary to allow the glenohumeral motion required during activities of daily living. At any one moment, only one fourth to one third of the humeral articular surface is covered by the glenoid.6 As such, the shoulder relies heavily on soft structures for stabilization during range of motion. Thus, contracture of any of the soft tissue stabilizers, be they the glenohumeral ligaments, the coracohumeral ligament, the shoulder capsule, or the rotator cuff musculature and tendons, can result in constriction of glenohumeral motion, resulting in the clinical picture of adhesive capsulitis.

Neviaser7 noted during surgical dissection of patients with adhesive capsulitis that the capsule was markedly thickened, there was a paucity of synovial fluid within the joint, and the capsule was in fact adherent to the humeral head. Arthrograms showed that patients diagnosed with adhesive capsulitis had a decreased joint volume with an obliteration of the axillary recess. Histologic evaluation of the capsule showed fibrotic changes with chronic inflammation as evidenced by perivascular inflammation with mononuclear cells.3

Arthroscopic evaluation of patients with primary adhesive capsulitis revealed a reduction in joint capacity with patchy synovitis, most consistently located in the rotator interval, but not the adhesions and axillary recess contractures that were present in the study by Neviaser.8,9 Open exploration of patients with chronic adhesive capsulitis revealed thickening of the coracohumeral ligament and rotator interval tissues. Histologic analysis of the resected tissues revealed fibrosis and fibroid degeneration.10 Immunocytochemical analysis has suggested that the underlying pathologic process is active fibroblastic proliferation, mimicking the findings seen in Dupuytren’s disease.11 This is further evidenced by the presence of mRNA encoding for fibrogenic growth factors similar to that seen in Dupuytren’s tissue.12 Evaluation of the synovium has revealed marked increases in several cytokines, suggesting an up-regulation of capsular fibroblasts, resulting in new collagen deposition.13 In fact, a strong association between adhesive capsulitis and Dupuytren’s disease has been suggested because patients with primary adhesive capsulitis have been shown to have an eightfold increase in Dupuytren’s disease compared with the general population.14 Mast cells have also been found to be present in diseased tissue, and as regulators of fibroblast proliferation, these cells may play an important role in the pathogenesis of adhesive capsulitis.15

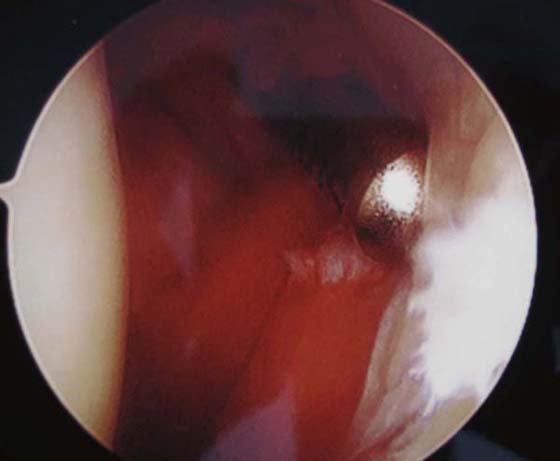

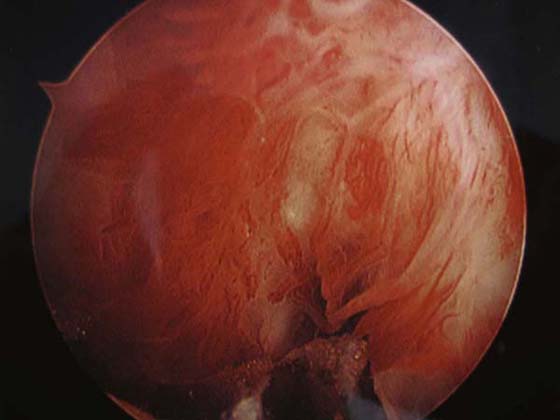

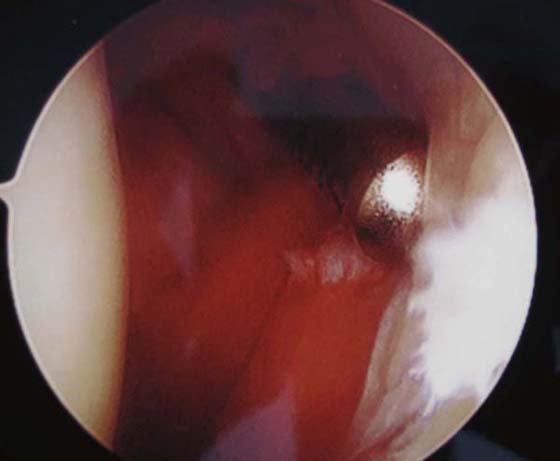

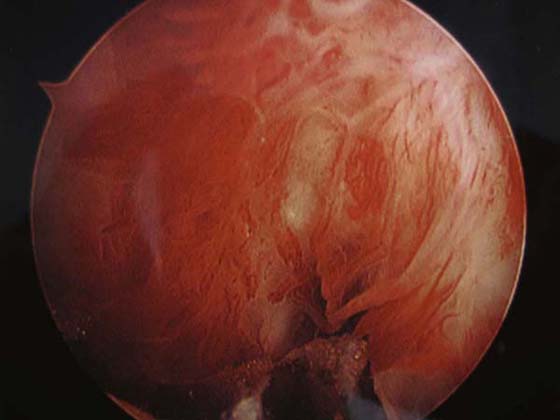

Adhesive capsulitis has been divided into four stages.16 Stage 1, preadhesive stage, presents as pain with active or passive range of motion with a progressive loss of motion. Pain is described as achy at rest and sharp at end-range of motion, particularly at the end of external rotation with the arm at the patient’s side.17 Symptoms typically have been present for less than 3 months. Arthroscopic examination reveals a diffuse hypervascular synovitis, most commonly in the region of the rotator interval (Fig. 89-2). In stage 2, the “freezing” stage, patients present with a further loss of range of motion secondary to capsular contracture and painful, proliferative synovitis. Arthroscopic evaluation reveals a dense, tight capsule and hypertrophic synovium (Fig. 89-3). Stage 3 is the “frozen” stage because patients show a marked loss of range of motion, but a decrease in pain. Arthroscopic examination reveals a very thick, dense, low-volume capsule with limited synovitis. Stage 4, the “thawing” stage, is the gradual resolution of symptoms with progressive improvements in range of motion with minimal pain. The increased range of motion is secondary to capsular remodeling and reestablishment of normal capsular volume.

Figure 89-2 Synovitis within the rotator interval.

Figure 89-3 Proliferative synovitis extending into the posterior capsule, encompassing the entire glenohumeral joint.

Secondary adhesive capsulitis has many causative factors and can be generalized into three categories: extrinsic, intrinsic, and systemic. Specifically, diabetic patients have been reported to have a fourfold increased risk of the development of adhesive capsulitis.18 It also appears that the duration of diabetes is an independent risk factor for the development of secondary adhesive capsulitis.18,19 There also appears to be an association between the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus with current antiretroviral therapies and the development of secondary adhesive capsulitis.20,21

Patients with previous shoulder fracture or shoulder surgery with stiffness represent an entire spectrum of shoulder pathology. Some patients have pure capsular stiffness from scarring or stiffening of the capsule. Other patients have stiffness from joint incongruency, prominent hardware, malunion, or scarring between the deltoid and humerus (scapulohumeral interval).22

History and Physical Examination

The diagnosis of primary adhesive capsulitis is a diagnosis of exclusion based on thorough history taking, physical examination, and appropriate imaging. Pain is overwhelmingly the chief symptom on presentation. Motion loss may also be a symptom, but many times, even with profound stiffness, patients do not realize that they have lost motion. They simply believe that they cannot move the arm because it is painful. A history of trauma, both major and minor, can be an inciting factor; however, many patients do not recall any specific event. Nighttime pain and pain when reaching behind the back or away from the body are extremely common. Acute left-sided shoulder pain may be a symptom originating from cardiac ischemia and should be considered during the evaluation.

Physical examination should include the cervical spine for referred pain secondary to radiculopathy, spondylosis, or other sources.

The shoulder examination begins with inspection of the patient, both at rest and with motion. Atrophy, previous scars, and active motion can be observed for both shoulders to allow comparison of the involved side with the uninvolved side. Glenohumeral motion is measured in planes of elevation, external rotation with the arm at the side, and internal rotation with the arm at the side, as a minimum. The tracking of the scapula during elevation can also be observed and compared with the normal side. After active motion is observed, passive motion is measured. True evaluation of glenohumeral motion requires scapular stabilization, eliminating any compensatory scapulothoracic motion and thoracic extension.

The hallmark of adhesive capsulitis on examination is a loss of both active and passive range of motion in multiple planes, especially in stages 2 and 3. However, no matter what stage of the disease process the patient presents with, active range of motion equals passive range of motion.

Patients presenting in early stages of adhesive capsulitis will have pain on palpation of the shoulder. Range of motion, particularly end-range of motion in external rotation, is painful secondary to the synovitis present within the rotator interval. The differentiating factor between stages 1 and 2 is that patients in stage 1 will have nearly normal glenohumeral motion, whereas stage 2 patients will show a loss of glenohumeral motion in multiple planes. Stage 3 patients have continued limitations in glenohumeral motion; however, stage 3 is characterized by a decrease in, but not absence of, pain. Stage 4 patients will begin to gradually regain their shoulder function, with continued improvements in glenohumeral motion as the capsular contracture begins to resolve (Table 89-1).

Table 89-1 Stages and Physical Examination Findings in Adhesive Capsulitis

Stage |

Physical Examination |

1 |

Near-normal range of motion |

|

Pain at end points of motion |

2 |

Marked loss of motion |

|

Pain at end points of motion |

3 |

Marked loss of motion |

|

Painless range of motion |

4 |

Improved glenohumeral motion |

|

Painless range of motion |

Differentiating early primary adhesive capsulitis from other pathologic conditions, such as rotator cuff pathology, can be quite difficult. However, the presence of signs of capsular irritation during the physical examination will help differentiate primary adhesive capsulitis from other underlying conditions.17 Placing the arm at the patient’s side and gently externally rotating the arm past the normal end point of motion will result in capsular stretching. In the presence of capsular pathology, this will reproduce the patient’s pain, but will not be seen if cuff pathology is the true underlying pain generator. Another technique to distinguish between cuff pathology and adhesive capsulitis is to perform a subacromial injection of local anesthetic. Injection of local anesthetic into the subacromial space should alleviate pain and improve motion if cuff pathology is present, but will do little to improve motion caused by capsular contracture.

Postsurgical and post-traumatic stiffness can be complex to evaluate. Fractures of the proximal humerus, clavicle, or any of the other bony structures can lead to shoulder stiffness. Shoulder surgery of any type can also lead to shoulder stiffness. The cause of the stiffness may be from glenohumeral capsule contracture, scarring of the scapulohumeral interval, malunion, nonunion, avascular necrosis, prominent hardware, post-traumatic arthritis, infection, nerve palsy, and chronic dislocation. Although the underlying pathology is wide ranging, evaluation begins with inspection and observation of range of motion, both active and passive. An assessment of rotator cuff strength and deltoid function is made. The quality of the glenohumeral motion is determined, i.e., the presence or absence of crepitus during motion and whether the pain occurs throughout the range of motion. The presence or absence of instability is also determined.

Radiographic Studies

Plain radiographs including true anteroposterior, axillary lateral, and a scapular Y-views are required for standard workup of shoulder pain regardless of the etiology. The primary reason for obtaining plain radiographs for patients with idiopathic adhesive capsulitis is to evaluate the glenohumeral joint space. Osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint can be quite painful and may limit glenohumeral range of motion, thus making this the primary differential diagnosis when evaluating a patient with a stiff, painful shoulder. Plain radiographs will also allow evaluation for other secondary causes of adhesive capsulitis, such as fractures, calcifying tendinitis, and cuff tear arthropathy. Advanced imaging studies are not necessary to make the diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis; they can, however, aid in ruling out many secondary causes. MRI will allow for better evaluation of possible soft tissue pathology that may be the underlying cause of restricted glenohumeral motion, such as rotator cuff tears and biceps pathology. MRI will also allow evaluation of the articular cartilage of both the glenoid and the humeral head, providing insight as to whether the underlying pathology is joint degeneration. Sher and colleagues23 showed that performing MRI will often result in a change in the primary diagnosis and the ultimate treatment plan.

CT scans will allow detailed evaluation of the glenohumeral joint, which will provide information regarding prominent hardware, bone loss, loose bodies within the joint, fracture malunion, and fracture nonunion. The use of CT is not required for the evaluation or treatment of primary adhesive capsulitis, but may be of value in postsurgical and postfracture stiffness.

Treatment

Nonoperative

Nonoperative measures are the first line of treatment for primary adhesive capsulitis. The natural history of primary adhesive capsulitis has been the subject of much debate. Hand and colleagues24 looked at a total of 269 shoulders that were on average 4 years removed from being diagnosed with idiopathic adhesive capsulitis. They showed that greater than 50% of the patients achieved nearly normal shoulder function, and 35% of the patients had continued symptoms consisting of mild pain and loss of function. Only 6% of the patients reported severe chronic symptoms. In contrast, Shaffer and colleagues25 showed that the natural history may not have as benign a course as is traditionally taught. They showed that 60% of the patients had measurable restriction of shoulder motion at an average of 7 years of follow-up and that 30% of the patients had restricted motion compared with the contralateral, unaffected shoulder. In all, only 11% of the patients reported mild functional limitations. A more recent study by Diercks and colleagues26 prospectively studied the effects of primary adhesive capsulitis in patients treated with standard physical therapy and a capsular stretching program compared with those treated with patient-directed range of motion based on pain threshold. The patients treated with a formal physical therapy program had a worse constant score, and there was no difference in range of motion after 24 months between the two groups. These studies highlight the difficulties in studying the effects of treatment of adhesive capsulitis because good patient controls are often limited and the natural history of the disease is one that progresses toward the resolution of symptoms.

The goals of nonoperative management are twofold: pain relief and restoration and maintenance of glenohumeral motion. Adequate pain relief and physical therapy should be a part of all treatment regimens. Lee and colleagues27 showed that patients who took analgesics combined with a physical therapy program fared better than those patients who did not receive oral analgesics.

Physical therapy is very much dependent on the stage in which the patient presents. Patients presenting with stage 1 have not had a substantial loss in glenohumeral motion, but do have significant amounts of pain due to the synovitis present within the glenohumeral joint. As such, physical therapy programs for patients presenting with stage 1 disease focus on pain relief through modalities and patient education for arm positioning. Patients presenting with stage 2 disease have pain but also have greater limitations in glenohumeral motion. Therefore, physical therapy for these patients focuses not only on pain relief, but also includes capsular stretching as a means to achieve increasing amounts of glenohumeral motion.28 Griggs and colleagues29 prospectively studied the effects of a shoulder stretching program in 75 patients who presented with stage 2 idiopathic adhesive capsulitis. Their results showed that 90% of the patients reported a satisfactory outcome and that only 7% required further treatment consisting of either manipulation under anesthesia and/or arthroscopic capsular release. There were also significant improvements in pain scores, both at rest and during activity. Shoulder range of motion improved in active forward flexion, active external rotation, passive internal rotation, and abduction. Vermeulen and colleagues30 showed that there may be some added benefit to implementing a high-grade physical therapy program that includes extension of passive stretching and range-of-motion exercises that go beyond the end points of pain-free range of motion. The high-grade treatment group showed slight improvements in shoulder external rotation and abduction compared with the low-grade group in whom passive movements were limited to those within a pain-free zone of motion. There was, however, no difference in shoulder outcome scores between the two groups.

Several nonoperative treatment modalities have been advocated for the management of adhesive capsulitis. Dogru and colleagues31 studied the effects of therapeutic ultrasound as a treatment for adhesive capsulitis. Both groups received superficial heat and an exercise program. The treatment group received therapeutic ultrasound, whereas the control group received a sham ultrasound. After treatment, there was no difference when comparing the two groups in terms of range of motion and patient satisfaction scales. Much of the nonoperative management has focused on minimizing the inflammation within the glenohumeral joint to prevent further capsular fibrosis and synovial hypertrophy. Sodium hyaluronate has been shown to prevent peritendinous adhesions after flexor tendon injuries, which is thought to be secondary to its ability to minimize the inflammatory response.32 However, Blaine and colleagues33 studied the effects of intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid compared with saline solution injections, and no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups when comparing range of motion as an outcome measure.

Steroids have long been used in the treatment of adhesive capsulitis secondary to their strong anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects. Buchbinder and colleagues34 showed that a short course of oral steroids resulted in improved pain scores, range of motion, and overall shoulder function. A Cochrane Database review that analyzed the use of oral steroids for treatment of adhesive capsulitis showed “silver” level evidence that oral steroids provide significant short-term benefits in terms of pain relief and improved range of motion; however, no evidence could be gathered to prove that this effect was maintained beyond 6 weeks.35

Many physicians favor the use of intra-articular steroid injections in an attempt to prevent the systemic side affects seen with oral steroid administration. A study comparing intra-articular steroid injections alone with physiotherapy alone showed that patients who received injections had better outcomes at 7 weeks, but that there was no difference between the two groups at 26 and 52 weeks of follow-up.36 Additionally, Carett and colleagues37 showed that the addition of intra-articular steroids to a physiotherapy regimen resulted in statistically significant improvements in range of motion and patient satisfaction outcome measures. In contrast, Kivimaki and Pohjolainen38 prospectively studied the effects of manipulation under anesthesia with and without intra-articular steroid injection and found that there was no improvement in outcome measures with the addition of a steroid injection.

Capsular distention or brisement has also been used as a means to treat adhesive capsulitis. Corbeil and colleagues39 performed a double-blinded, prospective study that looked at the effects of intra-articular steroid injections with and without distention arthrography. Early pain relief was reported by 80% of the patients, but at 3-month follow-up, they did not find any improvements in range of motion or pain relief in the capsular distention group. Likewise, Tveita and colleagues40 found no benefit with the combination of intra-articular steroids and capsular distention compared with steroids alone 6 weeks after treatment. Conversely, Gam and colleagues41 showed that patients who received intra-articular steroids and capsular distention had improved range of motion compared with steroids alone. Vad and colleagues42 prospectively evaluated the effects of capsular distention in patients who presented with stage 2 or 3 disease over a 2-year period. Patients who were in stage 2 showed statistically significant improvements in range of motion; however, patients who presented in stage 3 failed to show any significant improvements, suggesting that brisement be reserved for patients presenting in the early stages of the disease process. Watson and colleagues43 showed that capsular distention may also have a role in treating patients with secondary adhesive capsulitis resulting from underlying rotator cuff pathology. A 2008 Cochrane Database review gave “silver” level evidence that arthroscopic distention with saline solution and steroids provides short-term benefits in pain, range of motion, and overall function in adhesive capsulitis. However, the authors could not conclusively find any long-term benefits.44

Manipulation Under Anesthesia

Manipulation under anesthesia is a commonly used treatment for patients with adhesive capsulitis in whom conservative, nonoperative measures fail. Placzek and colleagues45 studied 31 patients who were treated with manipulation and followed them for 14 months. The patients showed a mean improvement in range of motion of 84 degrees in abduction, 63 degrees in forward flexion, 58 degrees in external rotation, and 47 degrees in internal rotation. Patients also reported significantly improved pain scores, and there were no reported complications. Farrell and colleagues46 looked at the long-term results of manipulation under anesthesia, with a mean follow-up of 15 years. Patients had an average range of motion improvement of 64 degrees in forward elevation and 44 degrees in external rotation. Of the 19 shoulders reviewed, 13 had no pain and 3 had only slight pain. The benefits of manipulation under anesthesia are often seen relatively early, allowing for restoration of glenohumeral motion and improved functionality. In a 5-year follow-up study, Farrell46 showed that patients who benefited from manipulation obtained their 5-year follow-up range of motion within the first 6 months after the procedure. Dodenhoff and colleagues47 prospectively assessed the effects of manipulation under anesthesia on early recovery and return to activity. They found that patients had an increase of 60 degrees in abduction, 30 degrees in external rotation, and 40 degrees in internal rotation at 6 weeks of follow-up. In addition, patients had statistically significant improvements in their constant scores. Overall, 94% of the patients were satisfied with the procedure. However, Kivimaki and colleagues48 performed a blinded, randomized trial with 1-year follow-up in which they compared manipulation under anesthesia with home exercises. They found that there was no statistical difference between the two groups, suggesting that patients properly instructed on how to perform a home exercise program will have the same outcome as those treated with a formal manipulation.

Arthroscopic Surgery

Surgical treatment for adhesive capsulitis is reserved for those patients in whom at least 6 months of nonoperative treatment have failed. Manipulation under anesthesia has been shown to be quite effective; however, it does not allow for a controlled release of the pathologic tissue. Contraindications and relative contraindications to manipulation include a previous failed attempt at manipulation in which the patient’s range of motion or pain has not improved, rotator cuff tears, chronic insulin-dependent diabetes, and osteopenia due to the fear of a humeral shaft fracture during the manipulation.49 In these instances, arthroscopic surgery provides an excellent alternative that allows complete inspection of the glenohumeral joint and will allow selective capsular releases to address the true underlying capsular pathology. Warner and colleagues50 showed that patients who were refractory to closed treatments and manipulation under anesthesia demonstrated statistically significant improvements in patient outcome scales and range of motion after arthroscopic anterior capsular release. Ogilvie-Harris and Myerthall51 performed an arthroscopic capsular release for diabetic patients with adhesive capsulitis and found statistically significant improvements in pain, external rotation, abduction, and overall shoulder function. Ogilvie and colleagues52 also compared manipulation under anesthesia with arthroscopic capsular release. Both groups showed similar improvements in range of motion; however, the arthroscopic capsular release group had significantly better pain relief and restoration of shoulder function. Nicholson53 prospectively studied the effects of arthroscopic release for adhesive capsulitis based on etiology. All groups showed significant improvements in forward elevation, external rotation, internal rotation, and patient outcome scales, suggesting that the etiology does not have an effect on the outcome after arthroscopic capsular release. Berghs and colleagues54 followed 25 patients after they underwent arthroscopic capsular release and found significant improvements in range of motion and patient outcome scales immediately after surgery, and, more importantly, these results were maintained at a mean of 14.8 months after surgery. Ide and Takagi55 confirmed that the improvements in motion and shoulder scoring systems that were seen in the first several months postoperatively were maintained at a mean of 7.5 years of follow-up. Holloway and colleagues56 studied the effects of arthroscopic capsular release in idiopathic, postfracture, and refractory postoperative shoulder stiffness. All groups showed statistically significant improvements in patient outcome scales and range of motion. However, the refractory postoperative stiffness group showed the least amount of improvement compared with the other groups.

Author’s Preferred Treatment

A patient diagnosed with adhesive capsulitis oftentimes can be frustrated at the prospects of just having to wait until his or her symptoms resolve. At the time of the initial diagnosis, much time is spent counseling the patient so he or she can understand the process. A treatment plan is then developed, making the waiting more tolerable. Treatment modalities include oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), activity modification, intra-articular steroid injections, and a gentle stretching program.

An NSAID can act both to relieve pain and to decrease inflammation. To maximize the anti-inflammatory action, the drug is prescribed for 1 to 2 weeks as a standing order. A typical dose would be either 600 mg Motrin (ibuprofen) three times daily or 500 mg Naprosyn (naproxen) twice daily. The patient can continue using the medication after that time if effective. In patients with a history of ulcers or bleeding disorders, a cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitor can be used instead.

Modification of the patient’s activity works on the principle of decreasing inflammation as the first stage of treatment. Activity by the patient is allowed as tolerated. A patient is instructed to use the arm until pain occurs. If, when the patient stops an activity because of pain and the pain quickly dissipates, there is likely no increase in inflammation. If the pain continues for hours after the offending activity, then the inflammation has likely increased in the shoulder. This is also a good rule to follow during therapy so as to be appropriately aggressive with stretching.

Intra-articular injections of steroid are given as a means to control pain and to decrease synovitis within the glenohumeral joint. The injections are often effective for a short period of time and can be repeated for a total of three times. Although the risk of infection is small, this must be discussed with patients before the procedure.

Physical therapy is based on a gentle stretching of the capsule and modalities to relieve inflammation and decrease muscle guarding. Too vigorous of a program can cause increased inflammation and pain. The choice to work with a therapist or to perform a home stretching program is determined with the patient. Even those patients who work with a therapist are to perform daily stretching as part of the program. See Chapter 90 for a detailed discussion of therapist’s management of the frozen shoulder.

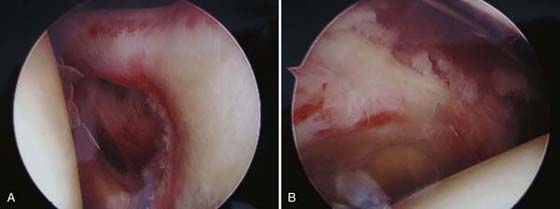

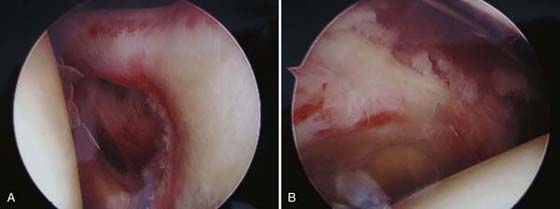

As stated earlier in the chapter, the vast majority of patients have improvement of shoulder pain and stiffness if given enough time. A small percentage will continue to have dysfunction from loss of motion. For those patients who have persistent loss of shoulder range of motion and a decrease in joint irritation, an examination under anesthesia with manipulation and arthroscopic capsular release is performed. During the procedure, the patient’s passive motion is recorded and then the shoulder is gently manipulated. If full, symmetrical range of motion is achieved, the procedure is completed. If any plane of motion continues to be restricted, arthroscopy of the patient’s shoulder is performed. During arthroscopy, areas of the capsule that remain tight are incised to achieve full passive motion (Fig. 89-4).

Figure 89-4 A, Arthroscopic debridement of the synovitis with capsular release of the rotator interval and anterior capsule. B, Arthroscopic debridement of the synovitis with posterior capsular release revealing the underlying muscle belly of the rotator cuff.

Patients begin daily therapy after undergoing manipulation and release. After a release, although decreasing inflammation is a priority, mobilization of the joint can be more aggressive than before surgery. The final outcome after release is achieved at different times for different patients but likely the motion achieved by 6 months is the final motion.

Summary

Adhesive capsulitis is a clinical condition characterized by painful and restricted active and passive range of motion. The essential pathology of adhesive capsulitis is thickening and contracture of the glenohumeral joint capsule, which becomes adherent to the humeral head. Primary or idiopathic adhesive capsulitis refers to an unexplainable onset of shoulder pain and loss of passive and active range of motion for which no intrinsic shoulder pathology can be identified. Secondary adhesive capsulitis is that which is associated with a known cause such as rotator cuff pathology, fractures of the proximal humerus, or diabetes mellitus. Treatments include therapy, steroid injections, capsular distention or brisement, manipulation under anesthesia, and arthroscopic surgery.

REFERENCES

1. Duplay S. De la péri-arthrite scapulo-humérale et des raideurs de l’épaule qui en sont la consequéce. Arch Gen Méd. 1872;20:513–542.

2. Codman EA. The Shoulder. Rupture of the Supraspinatus Tendon and Other Lesions In or About the Subacromial Bursa. Boston, privately printed 1934. 216-224

3. Neviaser JS. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. A study of the pathological findings in periarthritis of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg. 1945;27:211–222.

4. Lundberg BJ. The frozen shoulder. Clinical and radiographical observations. The effect of maipulation under general anesthesia. Structure and glycosaminoglycan content of the joint capsule. Local bone metabolism. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1969;119:1–59.

5. Cuomo F, Holloway GB. Diagnosis and management of the stiff shoulder. In: Iannotti JP, Williams GR, eds. Disorders of the Shoulder: Diagnosis and Management. 2nd ed Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:541–559.

6. Cole BJ, Rios CG, Mazzocca AD, Warnerd JP. Anatomy, biomechanics, and pathophysiology of glenohumeral instability. In: Iannotti JP, Williams GR, eds. Disorders of the Shoulder: Diagnosis and Management. 2nd ed Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:281–312.

7. Neviaser JS. Arthrography of the shoulder. Study of the findings in adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1962;44:1321–1359.

8. Wiley AM. Arthroscopic appearance of frozen shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1991;7(2):138–143.

9. Uitvlugt G, Detrisac DA, Johnson LL, et al. Arthroscopic observations before and after manipulation of frozen shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(2):181–185.

10. Ozaki J, Nakagawa Y, Sakurai G, Tamai S. Recalcitrant chronic adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(10):1511–1515.

11. Bunker TD, Anthony PP. The pathology of frozen shoulder. A Dupuytren-like disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(5):677–683.

12. Bunker TD, Reilly J, Baird KS, Hamblen DL. Expression of growth factors, cytokines, and matrix metalloproteinases in frozen shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(5):768–773.

13. Rodeo SA, Hannafin JA, Tom J, et al. Immunolocalization of cytokines and their receptors in adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. J Orthop Res. 1997;15(3):427–436.

14. Smith SP, Devaraj VS, Bunker TD. The association between frozen shoulder and Dupuytren’s disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(2):149–151.

15. Hand GC, Athanasou NA, Matthews T, Carr AJ. The pathology of frozen shoulder. J Bone Joint Surgery Br. 2007;89:928–932.

16. Hannafin JA, Chiaia TA. Adhesive capsulitis. a treatment approach. Clin Orthop. 2000;372:95–109.

17. Getz CL, Ramsey ML, Glaser DL, Williams GR. Adhesive Capsulitis. In: Blaine T, Levine W, eds. Shoulder Arthroscopy Monograph Series. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2006.

18. Thomas SJ, McDougall C, Brown ID, et al. Prevalence of symptoms and signs of shoulder problems in people with diabetes mellitus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(6):748–751.

19. Arkkila PE, Kantola IM, Viikari JS, Rönnemaa T. Shoulder capsulitis in type I and II diabetic patients: association with diabetic complications and related diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(12):907–914.

20. Grasland A, Ziza JM, Raguin G, et al. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder and treatment with protease inhibitors in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: report of 8 cases. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(11):2642–2646.

21. DePonti A, Viganò MG, Taverna E, Sansone V. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients during highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(2):188–190.

22. Romeo AA, Loutzenheiser T, Rhee YG, et al. The humeroscapular motion interface. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1998;350:120–127.

23. Sher JS, Iannotti JP, Williams GR, et al. The effect of shoulder magnetic resonance imaging on clinical decision making. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(3):205–209.

24. Hand C, Clipsham K, Rees JL, Carr AJ. Long-term outcome of frozen shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:231–236.

25. Shaffer B, Tibone JE, Kerlan RK. Frozen shoulder: A long term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(5):738–746.

26. Diercks RL, Stevens M. Gentle thawing of the frozen shoulder: A prospective study of supervised neglect versus intensive physical therapy in sevety-seven patients with frozen shoulder syndrome followed up for two years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(5):499–502.

27. Lee M, Haq AM, Wright V, Longton EB. Periarthritis of the shoulder: a controlled trial of physiotherapy. Physiotherapy. 1973;59(10):312–315.

28. Sheridan MA, Hannafin JA. Upper extremity: emphasis on frozen shoulder. Orthop Clin N Am. 2006;37:531–539.

29. Griggs S, Ahn A, Green A. Idiopathic adhesive capsulitis. A prospective functional outcome study of nonoperative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(10):1398–1407.

30. Vermeulen HM, Rozing PM, Obermann WR, et al. Comparison of high-grade and low-grade mobilization techniques in the management of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2006;86(3):355–368.

31. Dogru H, Basaran S, Sarpel T. Effectiveness of therapeutic ultrasound in adhesive capsulitis. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75(4):445–450.

32. Liu Y, Skardal A, Shu XZ, Prestwich GD. Prevention of peritendinous adhesions using a hyaluronan-derived hydrogel film following partial-thickness flexor tendon injury. J Orthop Res. 2008;26(4):562–569.

33. Blaine T, Moskowitz R, Udell J, et al. Treatment of persistent shoulder pain with sodium hyaluronate: a randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(5):970–979.

34. Buchbinder R, Hoving J, Green S, et al. Short course prednisolone for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder or stiff painful shoulder): a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1460–1469.

35. Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM, Johnston RV. Oral steroids for adhesive capsulitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006. Issue 4: CD006189. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006189

36. Van der windt DAWM, Koes BW, Devillé W, et al. Effectiveness of corticosteroid injections versus physiotherapy for treatment of painful stiff shoulder in primary care: randomized trial. Br Med J. 1998;317:1292–1296.

37. Carett S, Moffet H, Tardif J, et al. Intraarticular corticosteroids, supervised physiotherapy, or a combination of the two in the treatment of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. Arth Rheum. 2003;48(3):829–838.

38. Kivimaki J, Pohjolainen T. Manipulation under anesthesia for frozen shoulder with and without steroid injection. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:1188–1190.

39. Corbeil V, Dussault RG, Leduc BE, Fleury J. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: a comparative study of arthrography with intra-articular corticotherapy and with or without capsular distention. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1992;43:127–130.

40. Tveita EK, Tariq R, Sesseng S, et al. Hydrodilation, corticosteroids and adhesive capsulitis: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculskeletal Dis. 2008;9:53.

41. Gam AN, Schydlowsky P, Rossel I, et al. Treatment of “frozen shoulder” with distension and glucorticoid compared with glucorticoid alone. A randomized controlled trial. Scand J Rheum. 1998;27:425–430.

42. Vad VB, Sakalkale D, Warren RF. The role of capsular distention in adhesive capsulitis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1290–1292.

43. Watson L, Bialocerkowski A, Dalziel R, et al. Hydrodilatation (distention arthrography): a long-term clinical outcome series. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(3):167–173.

44. Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM, et al. Arthrographic distension for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008. Issue 1: CD007005. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007005

45. Placzek JD, Roubal PJ, Freeman DC, et al. Long-term effectiveness of translational manipulation for adhesive capsulitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;356:181–191.

46. Farrell CM, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Manipulation for frozen shoulder: long term results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(5):480–484.

47. Dodenhoff RM, Levy O, Wilson A, Copeland S. Manipulation under anesthesia for primary frozen shoulder: effect on early recovery and return to activity. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(1):23–26.

48. Kivimaki J, Pohjolainen T, Malmivaara A, et al. Manipulation under anesthesia with home exercises versus hom exercises alone in the treatment of frozen shoulder: a randomized, controlled trial with 125 patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(6):722–726.

49. Harryman DT, Lazarus MD. The stiff shoulder. In: Rockwood CA JR, Matsen FA III, eds. The Shoulder. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2004:1121–1172.

50. Warner JP, Allen A, Marks PH, Wong P. Arthroscopic release for chronic, refractory adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(12):1808–1816.

51. Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Myerthall S. The diabetic frozen shoulder: arthroscopic release. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(1):1–8.

52. Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Biggs DJ, Fitsialos DP, MacKay M. The resistant frozen shoulder. Manipulation versus arthroscopic release. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;319:238–248.

53. Nicholson GP. Arthroscopic capsular release for stiff shoulders: effect of etiology on outcomes. J Arthroscopy. 2003;19(1):40–49.

54. Berghs BM, Sole-Molins X, Bunker TD. Arthroscopic release of adhesive capsulitis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(2):180–185.

55. Ide J, Takagi K. Early and long-term results of arthroscopic treatment for shoulder stiffness. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(2):174–179.

56. Holloway GB, Schenk T, Williams GR, et al. Arthroscopic capsular release for the treatment of refractory postoperative or post-fracture shoulder stiffness. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(11):1682–1687.