4 PNEUMONIA AND THE SILHOUETTE SIGN

The CXR is excellent for detecting the presence and extent of most pneumonias. All the same, on the CXR some pneumonias are furtive and secretive and do their best to hide. Fortunately there is help at hand—the silhouette sign. If you look for the silhouette sign then you will be able to detect these hidden pneumonias.

PNEUMONIA

| “Words, like eyeglasses, blur everything that they do not make clearer”1 | |

| Bronchitis: | Acute or chronic inflammation of the lining of a bronchus. |

| Pneumonia: | An inflammation, usually due to infection, involving the alveoli. |

| Lobar pneumonia: | Pneumonia involving a large part of a lobe. Sometimes the entire lobe is involved. |

| Bronchopneumonia: | Pneumonia plus bronchitis. The involvement of the bronchi and bronchioles dominates over the alveolar inflammation2. The pathological process occurring in bronchopneumonia is frequently unappreciated. |

| Lung consolidation: |

The term “consolidation” is often used to describe pneumonic changes on a CXR. This can lead to misunderstandings because consolidation refers not only to infection, but to any pathological process that fills the alveoli with either pus, blood, fluid, cells… even lunch or pondwater.

Pneumonia is by far the commonest cause of an area of CXR consolidation. Consequently, some physicians use the two words—pneumonia and consolidation—synonymouslybut incorrectly. You need to be aware of this tendency. We favour using the word “consolidation” only when its generic meaning is implicit.

|

| Alveolar shadowing: | The generally accepted term when describing the CXR appearances of lung consolidation (see Chapter 3, pp. 32–35). Air space shadowing = alveolar shadowing. The two terms are used synonymously. |

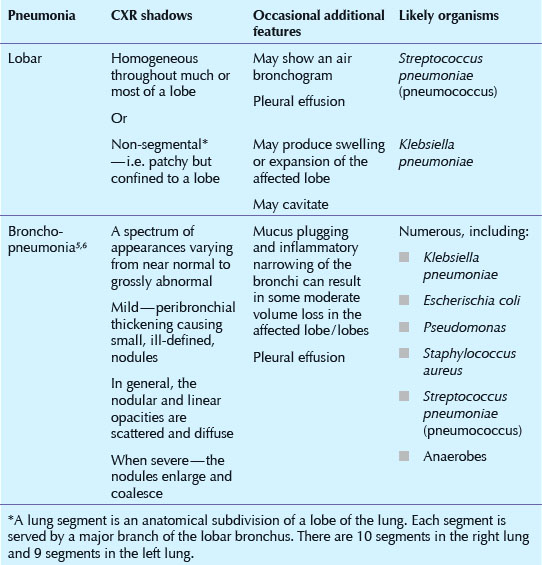

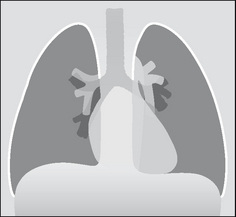

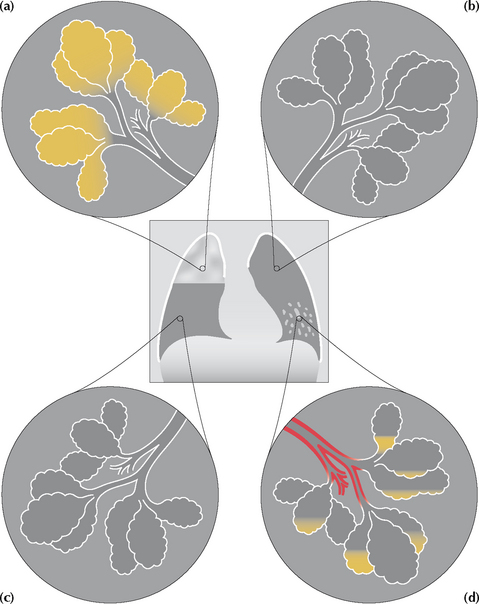

Figure 4.1 (a) Lobar pneumonia; right upper lobe. The alveoli are stuffed full of pus. (b) and (c) Normal lung; the alveoli are healthy and full of air. (d) Bronchopneumonia; left lower lobe. The bronchial walls, bronchioles, and the alveolar walls are inflamed and some pus has accumulated in the alveoli. Note: with bronchopneumonia it is the inflammation involving the bronchi and the bronchioles that predominates.

THE CXR AND PNEUMONIA

The CXR appearances of a lobar pneumonia, essentially an alveolar filling process, are usually obvious.

The CXR appearances of a lobar pneumonia, essentially an alveolar filling process, are usually obvious. A very early bronchopneumonia, when the inflammation is mainly affecting the bronchi and bronchioles, can be difficult to detect.

A very early bronchopneumonia, when the inflammation is mainly affecting the bronchi and bronchioles, can be difficult to detect.PNEUMONIA CAN HIDE: THE SILHOUETTE SIGN

BEN FELSON’S SILHOUETTE SIGN7,8

Silhouette: the outline of a solid object. Also the representation of such an outline, but filled solely with black or colour and used as a picture. It is oftenclaimed that the word owes its origin—because of the lack of any filling—to Etienne de Silhouette, a notoriously miserly finance minister to King Louis XV of France.

Silhouette sign: an intrathoracic lesion touching a border of the heart, aorta, or diaphragm will obliterate that border on the CXR. An intrathoracic lesion not anatomically contiguous with a border will not obliterate that border.

Misnomer: The term “silhouette sign” is a deliberate misnomer—convenient shorthand. The silhouette sign principle actually refers to the loss of part of the silhouette.

Ben Felson: a ground-breaking twentieth-century American radiologist and a wonderful teacher. He was not the first person to describe the silhouette sign but the description is invariably associated with his name.

On a normal CXR the well-defined borders of the heart and the domes of the diaphragm are visualised because the adjacent normal lung provides a flawless interface. If a pneumonia (i.e. pus-filled alveoli/inflamed bronchioles) abuts one of these interfaces then the sharp margin (heart or diaphragm) is lost. The CXR appearance of a blurred or missing interface is referred to as the silhouette sign7,8.

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS OF THE SILHOUETTE SIGN

APPLICATION 1

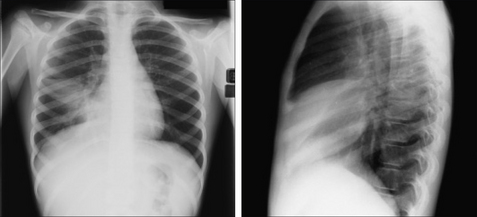

Whenever infection is suspected it is essential that evaluation of the CXR always includes checking whether a silhouette sign is present. Loss of part of the silhouette of the heart border or of the diaphragm may be the only abnormal feature on the CXR. This allows the precise position of the abnormality to be deduced (Fig. 4.4).

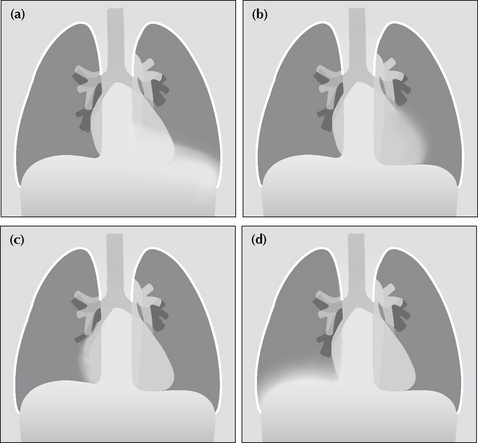

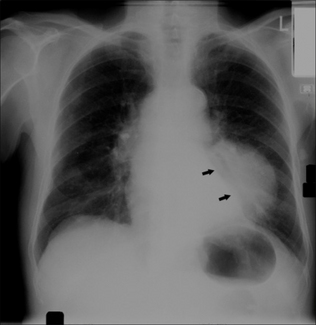

Figure 4.4 Four patients present with a cough and fever. The silhouette sign tells us that there is consolidation (pneumonia) in: (a) the left lower lobe—because the left dome of the diaphragm is blurred; (b) the lingular segments of the upper lobe—because the left heart border is blurred; (c) the middle lobe—because the right heart border is blurred;(d) the right lower lobe—because the right dome of the diaphragm is blurred.

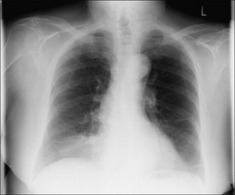

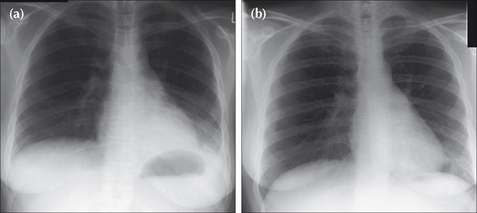

Figure 4.6 Cough and fever. (a) The left dome of the diaphragm is ill-defined…and so is the lateral margin of the descending aorta. These features indicate left lower lobe pneumonia. (b) Following treatment, a repeat CXR obtained six weeks later shows that all of the normal sharp borders and margins have returned.

APPLICATION 2

The silhouette sign is not solely applicable to pneumonia. It can be applied to any water density lesion that is in contact with the mediastinum or the diaphragm. Examples: lobar collapse, lung tumour, mediastinal mass.

Figure 4.8 Another example of the silhouette sign. A mass lesion overlies the right hilum. The right border of the heart is obliterated—i.e. it is not sharply defined. Note that the right dome of the diaphragm remains well-defined. These findings indicate that the lesion is intimately related to the margin of the heart. This was a benign mass—a pericardial cyst.

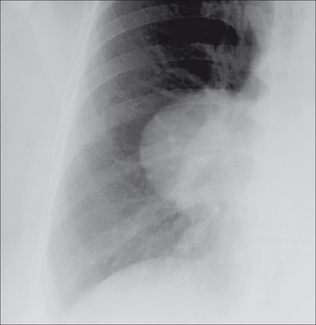

Figure 4.7 Middle-aged patient with a chronic cough. The CXR shows an ill-defined left dome of the diaphragm but a normal left border of the heart (arrows). In addition, note the increased density projected over the left side of the heart. These features indicate pathology in the left lower lobe. The lateral view showed a large lower lobe mass. Bronchial carcinoma.

Caution: some common pitfalls8

APPLICATION 3

The absence of a silhouette sign can tell you where a shadow (consolidation or mass) is not situated (Fig. 4.11).

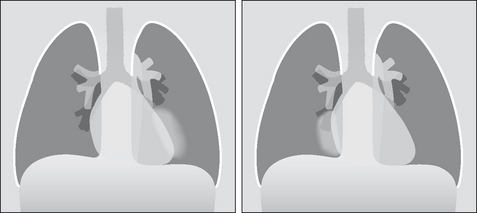

Figure 4.11 The patient on the left has consolidation in the left lung…but the left heart border remains sharp and clear. This consolidation must be in the lower lobe; it is not in a lingular segment of the upper lobe. The patient on the right has consolidation in the right lung…but the right heart border remains sharp and clear. This consolidation must be in the lower lobe; it is not in the middle lobe.

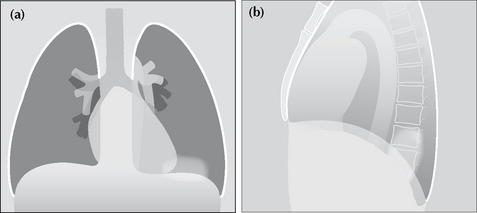

Figure 4.12 Silhouette sign…not infallible. Sometimes consolidation will be seen on the frontal CXR and the dome of the diaphragm remains sharp and clear (a). Yet a lateral CXR (b) shows that the consolidation is situated in the lower lobe. This can occur when the consolidation is situated far posteriorly—well below the highest point of the dome of the diaphragm.

PNEUMONIA—A SIX-WEEK RULE

Sometimes an important question will be raised—could there be an underlying bronchial carcinoma in this patient who has CXR evidence of pneumonia? If there are no specifically worrying social (e.g. smoking), clinical, or radiological features then the following approach is recommended:

There is no need to rush to repeat the CXR if the patient is clinically well or improving. In approximately 73% of patients with a community acquired pneumonia the CXR will be clear at six weeks5. Some simple pneumonias take even longer to clear6.

There is no need to rush to repeat the CXR if the patient is clinically well or improving. In approximately 73% of patients with a community acquired pneumonia the CXR will be clear at six weeks5. Some simple pneumonias take even longer to clear6. Adopt the six-week CXR rule: following the initial CXR in a patient who is now well, do not repeat the CXR before six weeks. If the CXR is not clear at six weeks then: (a) If the patient is still well and there are no worrying features, obtain CXRs at four-weekly intervals in order to ascertain that clearing is continuing; (b) For all smokers older than 40 years, and for any patient with another risk factor or clinical feature for lung cancer, then arrange bronchoscopy6 or CT.

Adopt the six-week CXR rule: following the initial CXR in a patient who is now well, do not repeat the CXR before six weeks. If the CXR is not clear at six weeks then: (a) If the patient is still well and there are no worrying features, obtain CXRs at four-weekly intervals in order to ascertain that clearing is continuing; (b) For all smokers older than 40 years, and for any patient with another risk factor or clinical feature for lung cancer, then arrange bronchoscopy6 or CT.1. Joseph Jonbert. French essayist and moralist (1754–1824).

2. Glossary of terms for thoracic radiology: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the Fleischner Society. AJR. 1984;143:509-517.

3. Reed JC. Chest Radiology: Plain Film Patterns and Differential Diagnosis, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby, 2003.

4. Itoh H, Tokunaga S, Asamoto H, et al. Radiologic–pathologic correlations of small lung nodules with special reference to peribronchiolar nodules. AJR. 1978;130:223-231.

5. Mittl RL, Schwab RJ, Duchin JS, et al. Radiographic resolution of community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:630-635.

6. Johnson JL. Slowly resolving and nonresolving pneumonia. Postgraduate Medicine. 2000;108:115-122.

7. Felson B, Felson H. Localization of intrathoracic lesions by means of the postero-anterior roentgenogram: The silhouette sign. Radiology. 1950;55:363-374.

8. Felson B. Chest Roentgenology. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1973.

9. Hollman AS, Adams FG. The influence of the lordotic projection on the interpretation of the chest radiograph. Clin Radiol. 1989;40:360-364.

10. Zylak CJ, Littleton JT, Durizch ML. Illusory consolidation of the left lower lobe: a pitfall of portable radiography. Radiology. 1988;167:653-655.