3 ALVEOLAR DISEASE VERSUS INTERSTITIAL DISEASE

An area of diffuse shadowing on a CXR requires careful analysis. In large part the analysis depends upon relating the shadowing to the clinical details obtained from the history and the physical examination. However, on occasion this will not be enough on its own and it is the evaluation of the shadow pattern which will allow a particular diagnosis or group of diagnoses to be considered.

This chapter aims to help you to recognise two common disease patterns: alveolar and interstitial. There are aspects of alveolar disease, interstitial disease, consolidation and pneumonia which are all closely related. Please read this chapter and Chapter 4 together.

THE ALVEOLI AND THE INTERSTITIUM

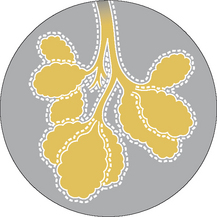

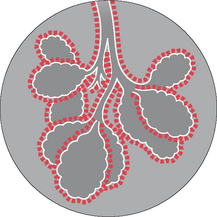

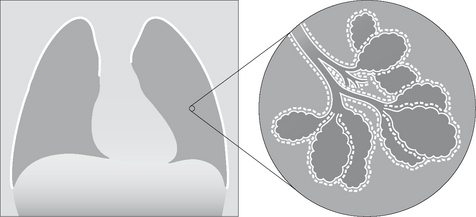

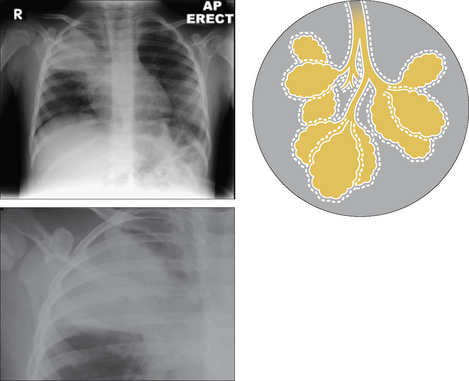

Figure 3.1 illustrates the normal relationship between the alveoli and the interstitium.

Figure 3.1 Normal lung. The terminal bronchioles give rise to alveolar ducts which terminate in small air sacs (alveoli). The millions of thin walled alveoli are responsible for gas exchange…carbon dioxide out of the capillaries, oxygen into the capillaries. The interstitium of the lung surrounds both the alveoli and the terminal bronchioles. The interstitium has a most important mechanical function: it acts as a scaffold supporting the alveolar walls. It also has a dynamic function: fluid, cells and nutrients pass into and out of the interstitium.

ALVEOLAR AND INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASE1,2

| Alveolar disease: | The filling of alveolar air spaces with abnormal material. That material may be blood, pus, water, protein, cell debris — or a combination of two or more of these. |

| Interstitial disease: | Affects the supporting tissues of the lung parenchyma (i.e. the interstitium) including the alveolar walls. |

Some disease processes affect mainly the alveoli, or mainly the interstitium. Some diseases involve the alveoli and the interstitium just about equally.

The pathological process consequent on most lung injuries can be summarised as follows: the insult causes the cellular lining of the alveolar walls and/or the capillaries in the interstitium to become leaky. The oedema that leaks out accumulates in the alveoli or in the interstitium. Sometimes the injury continues to progress and causes extensive necrosis with the production of fibrin and cell debris. These necrotic products fill the alveolar air spaces or thicken the tissues in the interstitium.

THE CXR: ALVEOLAR VERSUS INTERSTITIAL DISEASE1-4

When a CXR shows an area of diffuse shadowing—whether localised or widespread—then the shadow pattern needs to be analysed carefully. It is worth emphasising: the CXR shadow pattern represents the underlying pathological process. The CXR features to look for are listed in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1 CXR features to look for.

| Alveolar changes | Interstitial changes | |

|---|---|---|

| Usual shadows | ||

| Sometimes …additonally |

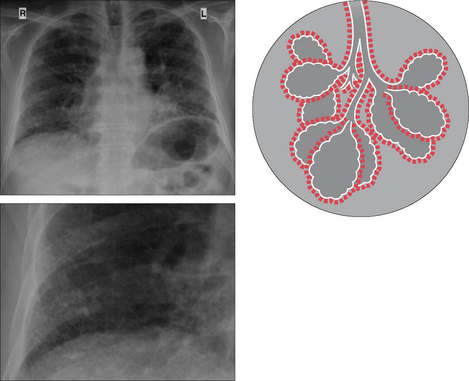

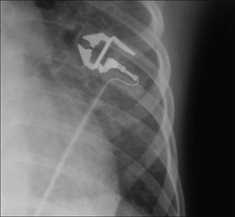

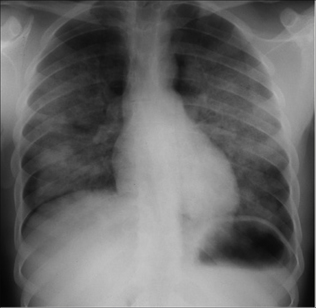

Figure 3.4 Alveolar disease. The alveoli are (in this case) stuffed with pus, giving a fluffy homogeneous pattern which has coalesced. (Pneumonia.)

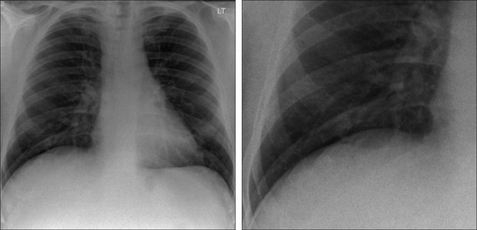

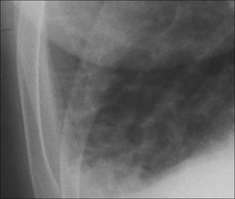

Septal lines = fine thread-like lines produced by fluid or thickening of the septa between the lobules of the lung. Several different types of septal lines have been described1,2,4, but much the most common are those referred to as Kerley B lines. Septal lines = fine thread-like lines produced by fluid or thickening of the septa between the lobules of the lung. Several different types of septal lines have been described1,2,4, but much the most common are those referred to as Kerley B lines. Kerley B lines = fine horizontal lines approximately 1 cm long, situated perpendicular to the lateral pleural surface. They are most commonly seen just above the costophrenic angles on a frontal CXR (see pp. 158–159). Kerley B lines = fine horizontal lines approximately 1 cm long, situated perpendicular to the lateral pleural surface. They are most commonly seen just above the costophrenic angles on a frontal CXR (see pp. 158–159). |

INTERSTITIAL SHADOWING—ARE YOU SURE?

A regular problem when evaluating a CXR is determining whether the lungs are actually clear and normal. Sometimes the lung markings (i.e. the normal vessels) are rather prominent and the question is raised—is there anything else there? Could some of these markings be fine linear interstitial shadows? This usually relates to a lower zone.

Normal lungs on the CXR should show nothing other than vessels and occasionally a lung fissure. Normal bronchial walls are only visualised if they are seen end on. Normal alveoli, normal interstitium, normal lymphatics—none of these are visible.

So, is there anything there? When in doubt apply these two rules:

| Rule 1 | Look at the lung immediately adjacent to the costophrenic angle — it should be clear. If this particular part of the lung shows prominent markings then interstitial disease at the lung base is likely. This rule is particularly helpful in females when part of the lung projects just lateral to the overlying breast shadow because the breast density sometimes mimics lung pathology. |

| Rule 2 |

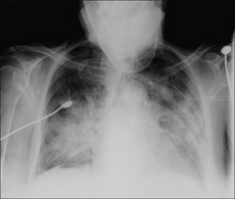

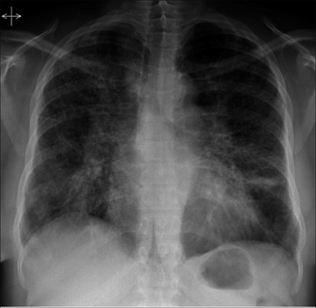

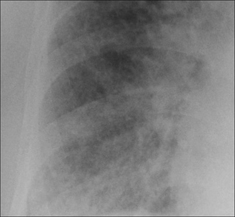

THE CXR: NOT ALWAYS EASY TO ASSESS

Sometimes there is an “emperor’s new clothes” approach to the implied ease with which the distinction can be made between alveolar disease and interstitial disease on a CXR. Take such claims with a pinch of salt. In a number of instances you will find that it is very difficult to decide whether the classic features (Table 3.1) are actually present (Figs 3.9 and 3.10). All the same it is often possible, following a careful analysis, to recognise a particular pattern. If a particular pattern can be identified then a legitimate differential diagnosis can be suggested (Table 3.3).

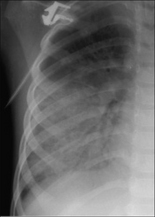

Figure 3.9 The pattern is difficult to categorise. Neither classically alveolar nor classically interstitial. We are not able to pigeonhole the shadow pattern in this case.

Table 3.3 Differential diagnosis.

| Dominant alveolar/airspace pattern | Dominant interstitial pattern |

|---|---|

| Adults: | |

| Infants: |

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS1-4

Frequently, a classical alveolar or interstitial CXR pattern is dominant (Table 3.3). A dominant pattern allows a selective differential diagnosis to be considered. When linked to the clinical history, physical examination, and laboratory tests, then the likely diagnosis usually emerges (Figs 3.11-3.14).

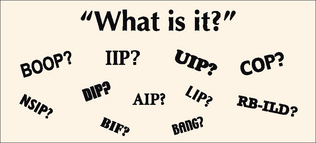

CONFUSION: INTERSTITIAL FIBROSIS & ALL THOSE ACRONYMS

Very often the cause of a chronic interstitial pattern (or a honeycomb appearance) on the CXR will be obvious because of a particular clinical history and the age-old principle: common things occur commonly.

Very often the cause of a chronic interstitial pattern (or a honeycomb appearance) on the CXR will be obvious because of a particular clinical history and the age-old principle: common things occur commonly. When the diagnosis remains obscure then CT will frequently suggest the probable cause 5–11. In some patients a lung biopsy will still be necessary.

When the diagnosis remains obscure then CT will frequently suggest the probable cause 5–11. In some patients a lung biopsy will still be necessary.The CXR

Various classifications/descriptions of interstitial fibrosis are in use. The numerous acronyms can be very confusing. The confusion started after the histopathologists separated out several of the different disease processes. Chest physicians and CT radiologists then sought to match and mirror the microscopic findings with the CT patterns. Some of the acronyms are those used by histopathologists, some are those used by radiologists, and some are used incorrectly.

Remember, the CXR is a plain, simple, and very modest examination. It recognises its limitations and leaves the sophisticated separation of the BIFs from the BANGs to CT or to a lung biopsy.

In a patient with dyspnoea and a chronic interstitial CXR pattern, we use the following approach. The CXR shadows will represent either (A) or (B):

(A) True interstitial fibrosis.

| Either: | A complication or residuum of an already known disease or consequent on an extrinsic stimulus. Examples include: granulomatous diseases (tuberculosis, sarcoid); collagen-vascular diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, progressive systemic sclerosis); gastro-intestinal disease (aspiration pneumonitis); iatrogenic — radiotherapy or drug-related (Amiodorone, Nitrofurantoin, Methotrexate, Bleomycin); occupational disease (asbestosis, silicosis); extrinsic allergic alveolitis (bird fancier’s lung, farmer’s lung). |

| Or: | Aetiology unknown, i.e. cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis (idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis). The histopathologists call this usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). |

(B) Lung disease that can mimic the CXR appearance of interstitial fibrosis.

This includes: lymphangitis carcinomatosa; eosinophilic pneumonia; Langerhan’s cell histiocytosis; bronchiolitis obliterans with organising pneumonitis (BOOP); lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

1. Felson B. Chest Roentgenology. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1973.

2. Reed JC. Chest Radiology: Plain Film Patterns and Differential Diagnosis, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby, 2003.

3. Schapiro RL, Musallam JJ. A radiologic approach to disorders involving the interstitium of the lung. Heart Lung. 1977;6:635-643.

4. Collins J, Stern EJ. Chest Radiology: The Essentials. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 1999.

5. Padley SPG, Hansell DM, Flower CDR, et al. Comparative accuracy of high resolution computed tomography and chest radiography in the diagnosis of chronic diffuse infiltrative lung disease. Clin Radiol. 1991;44:222-226.

6. Green SJ, Khan SS, Desai SR. “Aunt Minnies” of thoracic high-resolution CT. Radiology Now. 2004;21:20-24.

7. Travis WD, King TE, the multidisciplinary core panel. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary consensus classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:277-304.

8. American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement. American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:646-664.

9. Screaton NJ, Hiorns MP, Lee KS, et al. Serial high resolution CT in non-specific interstitial pneumonia: prognostic value of the initial pattern. Clin Radiol. 2005;60:96-104.

10. Flaherty K, Toews G, Travis W, et al. Clinical significance of histological classification of interstitial idiopathic pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:275-283.

11. Mueller-Mang C, Grosse C, Schmid K, et al. What every radiologist should know about idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Radiographics. 2007;27:595-615.