9 PATTERNS IN 21ST CENTURY LUNG INFECTIONS

In this chapter we describe CXR features that occur with:

PNEUMONIA1,2

Pneumonia: An acute lower respiratory tract infection together with new radiographic shadowing1.

A patient who is diagnosed with pneumonia in primary care will receive antibiotic treatment. In most instances treatment of an uncomplicated community acquired pneumonia is relatively straightforward1,2. Amoxicillin is currently the antibiotic of choice because the causative organism is likely to be gram positive. The severity of the pneumonia will dictate whether a more complex antimicrobial regime is instituted.

A patient who is diagnosed with pneumonia in primary care will receive antibiotic treatment. In most instances treatment of an uncomplicated community acquired pneumonia is relatively straightforward1,2. Amoxicillin is currently the antibiotic of choice because the causative organism is likely to be gram positive. The severity of the pneumonia will dictate whether a more complex antimicrobial regime is instituted. A hospital acquired pneumonia is usually due to a gram negative organism and intravenous broad spectrum cephalosporins are usually recommended.

A hospital acquired pneumonia is usually due to a gram negative organism and intravenous broad spectrum cephalosporins are usually recommended. Sometimes the CXR appearances will raise the suspicion that the pneumonia may be caused by an unusual organism. This can alert the physician and may influence the choice of a particular antibiotic.

Sometimes the CXR appearances will raise the suspicion that the pneumonia may be caused by an unusual organism. This can alert the physician and may influence the choice of a particular antibiotic. This chapter highlights a few selected points in relation to the value of a CXR—i.e. beyond confirming that pneumonic consolidation is present.

This chapter highlights a few selected points in relation to the value of a CXR—i.e. beyond confirming that pneumonic consolidation is present.SOME GENERAL RULES

The typical CXR patterns of bronchopneumonia and lobar pneumonia are described on pp. 32–35 and 42–44.

MIGHT THE PNEUMONIA BE ATYPICAL?

This refers to an atypical organism—usually Mycoplasma or Legionella. If this is considered to be likely then a macrolide antibiotic will be introduced.

| Clinical/laboratory | CXR |

|---|---|

STAPHYLOCOCCAL PNEUMONIA

This is usually acquired within the hospital. If the causative organism is Staphylococcus aureus then flucloxacillin is introduced. Several CXR features are not specific but are nevertheless suggestive of this organism:

Development of a pneumatocoele. This occurs most commonly in children.

Development of a pneumatocoele. This occurs most commonly in children.

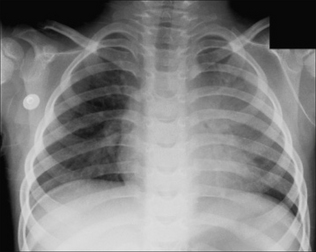

A pneumatocoele is a gas filled space in the lung adjacent to an area of consolidation. On the CXR it appears as a round lucent area (Fig. 9.3). A pneumatocoele is a transient CXR appearance.

A pneumatocoele is a gas filled space in the lung adjacent to an area of consolidation. On the CXR it appears as a round lucent area (Fig. 9.3). A pneumatocoele is a transient CXR appearance.

Figure 9.3 Severe chest infection. The round lucent area adjacent to the left lower lobe consolidation is a pneumatocoele. Pneumatocoeles are distended air spaces that are characteristically transient—i.e. they disappear fairly quickly. Pneumatocoeles do not represent areas of cavitation. Staphylococcal pneumonia.

ASPIRATION PNEUMONIA

This may result from inhalation of gastric or oropharyngeal fluids, pus from infected sinuses, or inhalation of external fluid. If aspiration is the likely cause of the pneumonia then intravenous cephalosporin/metronidazole is added to the antimicrobial treatment. The following are suggestive of aspiration:

PNEUMONIA WITH CAVITATION

This can occur with an acute bacterial pneumonia. The most common causative organisms are Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, Pseudomonas aeroginosa, Klebsiella, Escherichia coli. (See pp. 134–137 for tuberculosis.)

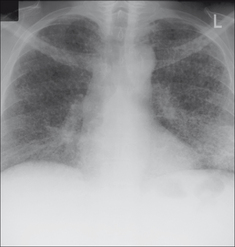

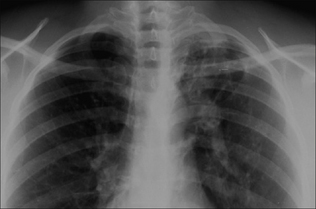

Figure 9.1 Child with a chest infection. Fluffy/confluent homogeneous shadowing in the left upper lobe. Lobar pneumonia. See pp. 42–44.

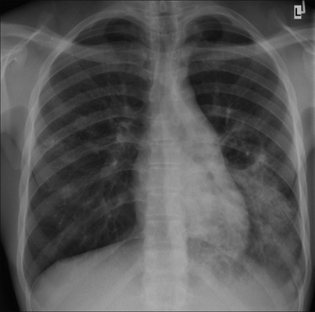

Figure 9.2 Chest infection. The linear and nodular shadows in both lower zones represent the typical pattern of a bronchopneumonia (see pp. 42–44). This was a viral pneumonia.

PULMONARY TUBERCULOSIS3

CLASSIC PATTERNS

Pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) is often suspected by the physician when a patient from a particular at-risk group (e.g. socio-economic/demographic) has minimal clinical symptoms and an abnormal CXR. If a patient is outside a generally accepted at-risk group then even a classic CXR PTB pattern may be misinterpreted and tuberculosis not considered.

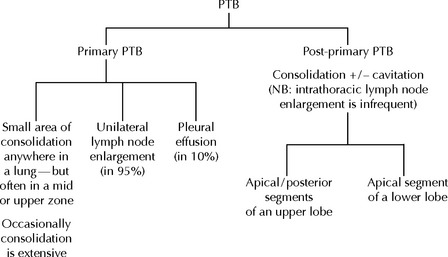

It is important to recognise CXR patterns that raise the suspicion of PTB (Table 9.2). As a general rule, the distribution and position of PTB shadows differs between primary and post-primary disease.

Table 9.2 The most common CXR appearances.

|

Pitfall. CXR changes in post-primary PTB have a strong predilection for the apical or posterior segments of the upper lobes and also for the apical segments of the lower lobes. Sometimes post-primary tuberculosis shadowing will occur in the anterior segment of an upper lobe or in a basal segment of a lower lobe. This distribution may lead to the assumption that the shadows are not due to PTB. However, an apparently atypical position for shadowing in post-primary disease is usually accompanied by shadowing in the classical segments. The message: if post-primary PTB is clinically possible you must always check out the classical segments on both the frontal and lateral CXRs3.

MILIARY PTB

This represents haematogenous spread of the bacilli. It is most commonly associated with primary PTB but it can occur with post-primary PTB. The term “miliary” refers to the millet-seed appearance of the tiny nodules scattered throughout the lungs. To be truly miliary the small densities will all be of the same size (0.5–2.0 mm in diameter), sharply defined, and will usually involve the lung apices.

The visibility of these tiny nodules on the CXR is the result of superimposition of hundreds of the tiny foci one on top of another. If the number of foci are not yet in their hundreds and thousands then they will not be detectable. Consequently, a patient may have miliary PTB and yet the CXR may appear normal.

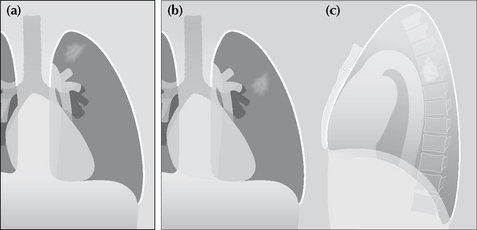

Figure 9.5 Classic patterns in post-primary PTB. Lung shadowing that favours the apical or posterior segments of an upper lobe (a); or involving the apical segment of a lower lobe (b, c).

Figure 9.6 Unilateral hilar lymph node enlargement (and, incidentally, the azygos node is also enlarged). Primary PTB.

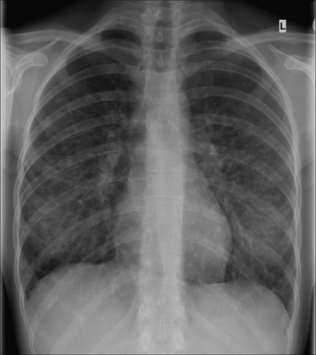

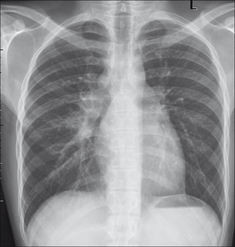

Figure 9.8 Diffuse shadowing in both lungs with cavitation. A lateral CXR showed the apical segments of both lower lobes to be involved. Post-primary PTB. You might wish to remind yourself of the superior extent of both lower lobes on the reference images at the front of the book (p. viii.)

ARE THE CXR SHADOWS DUE TO ACTIVE OR INACTIVE PTB?

A recurring dilemma. A CXR shows PTB scarring—but are there any features to suggest that it could be active? Table 9.3 provides some guidelines which will help to make the assessment.

Table 9.3 Active or Inactive PTB?

| Active | Probably inactive | Apply the precautionary principle: |

|---|---|---|

Figure 9.10 Note the well-defined (“hard”) shadowing at the apex of the left lung with elevation of the left hilum. These features suggest old inactive PTB affecting the upper lobe.

Figure 9.11 Ill-defined shadowing at the right lung apex. Active post-primary PTB. NB: the lung apices are where tuberculous shadows commonly occur…and they can hide behind the overlapping ribs and clavicle. On this CXR compare and contrast the appearance of the right lung apex with the entirely normal left apex.

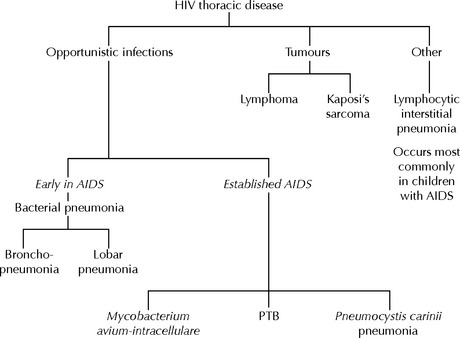

HIV RELATED OPPORTUNISTIC LUNG INFECTIONS4

The Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) first appeared as a devastating epidemic during the 1980s. The cause of the syndrome is infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Affected patients are immunocompromised. Consequently they are vulnerable to secondary infection with other organisms. Debilitating and life-threatening lung infections (Table 9.4) are common.

Table 9.4 HIV-related lung infections.

|

MYCOBACTERIUM AVIUM-INTRACELLULARE

The CXR appearances are non-specific. They include: hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement; and/or nodular lung shadows; and/or areas of alveolar consolidation.

PNEUMOCYSTIS CARINII PNEUMONIA (PCP)

With confirmed PCP infection the CXR is abnormal in the majority of cases. The reported incidence of a normal CXR varies in different series (5–30% of cases). The common CXR patterns:

With confirmed PCP infection the CXR is abnormal in the majority of cases. The reported incidence of a normal CXR varies in different series (5–30% of cases). The common CXR patterns:

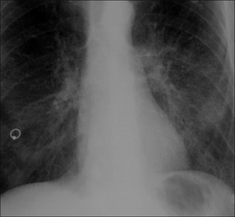

Figure 9.12 Young male. Breathless. Lower zone reticular densities create a basal ground glass (i.e. a rather hazy) appearance. PCP. This is an early CXR finding and is often very subtle. Rapid progress to extensive areas of alveolar consolidation usually occurs. (Incidental body piercing artefact through the right nipple.)

1. Hoare Z, Lim WS. Pneumonia: update on diagnosis and management. BMJ. 2006;332:1077-1079.

2. Woodhead M, Blasi F, Ewig S, et al. Guidelines for the management of adult respiratory tract infections. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:1138-1180.

3. Woodring JH, Vandiviere HM, Fried AM, et al. Update: The radiographic features of pulmonary tuberculosis. AJR. 1986;146:497-506.

4. O’Neil KM. The changing landscape of HIV-related lung disease in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Chest. 2002;122:768-771.