Chapter 20 Psychosomatic Illness

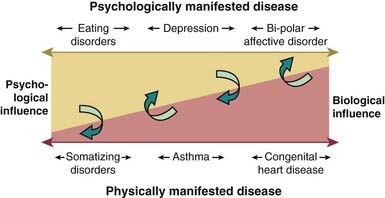

Psychosomatic medicine deals with the relation between physiologic and psychologic factors in the cause or maintenance of disease. Physical illnesses have accompanying emotional symptoms, and psychiatric illnesses commonly have associated somatic or physical symptoms. It is important for health care providers to avoid the dichotomy of approaching illness using a medical model in which diseases are considered either organic or psychologically based. A biobehavioral continuum of disease characterizes illness as occurring across a spectrum ranging from a biologic etiology on one end to predominantly a psychosocial etiology on the other (Fig. 20-1). Using the biopsychosocial approach, biologic, psychologic, social, and developmental realms are integrated into an understanding of an individual patient’s presentation.

Figure 20-1 Biobehavioral continuum of disease.

(From Wood BL: Physically manifested illness in children and adolescents: a biobehavioral family approach, Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 10:543–562, 2001.)

The interplay of physiologic and psychosocial factors is readily seen in children experiencing stressful life events. During periods of stress, neuroregulatory mechanisms undergo changes that render the body more vulnerable to infection and other disorders. The pathophysiologic basis of these changes can include immune activation with release of hormonal immune factors (cytokines) in response to acute stress as well as a decrease in the number and activity of natural killer cells in situations of more chronic stress. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis may be affected, resulting in an excess secretion of cortisol, which can produce structural damage to various organ systems. Under acute stress, the sympathomimetic effects of catecholamines can cause elevated blood pressure and tachycardia.

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), the diagnosis psychological factors affecting general medical conditions acknowledges the influence of emotional and behavioral factors on the onset and course of physical illness, including stress-related physiologic responses. This diagnosis requires physical findings of disease (e.g., asthma, diabetes, gastric ulcer, migraine headache, or ulcerative colitis) and evidence that psychologic factors are temporally related to the appearance, exacerbation, and/or maintenance of the physical symptoms.

The DSM-IV-TR defines the category of Somatoform Disorders, which are on the end of the continuum where predominantly psychologic factors contribute to the presentation of somatic symptoms. Somatization may be defined as the process whereby distress is experienced and/or expressed in physical modalities (recurrent abdominal pain, headache, and various neurologic symptoms). In children, recurrent poorly explained physical complaints generally fall into 4 distinct symptom clusters: cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, pain, and neurologic. In patients presenting with somatoform disorders, the physical findings are insufficient to explain the symptoms and/or the complaints are in excess of what would normally be expected based on the underlying physical illness.

The DSM-IV-TR category of somatoform disorders includes Somatization Disorder, Conversion Disorder, and Pain Disorders Associated with Both Psychological Factors and a General Medical Condition (Tables 20-1 to 20-4). Somatoform Disorder Not Otherwise Specified includes presentations with disabling somatic symptoms that do not meet the full DSM-IV-TR criteria for any of the aforementioned disorders. Hypochondriasis and Body Dysmorphic Disorder occur rarely in childhood.

Table 20-1 DSM-IV-TR DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR SOMATIZATION DISORDER

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association, p 490.

Table 20-2 DSM-IV-TR DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR UNDIFFERENTIATED SOMATOFORM DISORDER

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association, p 492.

Table 20-3 DSM-IV-TR DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR CONVERSION DISORDER

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association, p 498.

Table 20-4 DSM-IV DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR PAIN DISORDER

Code as Follows:

307.80 Pain Disorder Associated with Psychological Factors: psychological factors are judged to have the major role in the onset, severity, exacerbation, or maintenance of the pain. (If a general medical condition is present, it does not have a major role in the onset, severity, exacerbation, or maintenance of the pain.) This type of Pain Disorder is not diagnosed if criteria are also met for Somatization Disorder.

Specify If:

Specify If:

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association, p 503.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that somatic complaints are seen in adolescents at a rate of 4.5-10% in boys and 10-15% in girls. Conversion Disorder has prevalence rates that vary between 0.5% and 10%. Headaches, recurrent abdominal pain, limb pain, and chest pain have been reported as having prevalence rates ranging from 7-30% in community and clinical samples.

Risk Factors

Family and Environmental

Sociocultural

Youngsters of lower socioeconomic status or those who live in rural areas have higher rates of somatoform disorders. Local cultural ideas about acceptable and credible ways to express psychologic distress might play a role in the expression of somatic symptoms. Conversion symptoms have also been reported more commonly in non-Western clinical settings.

Genetic

A possible genetic etiology in somatization disorders is suggested by findings of a 29% concordance rate in monozygotic twins and 10-20% of first-degree relatives of patients meeting criteria for this disorder. There is also a familial link between somatization disorders and other psychiatric disorders (e.g., higher rates of anxiety and depression in the family members).

Symptom Model

Children may be more prone to adopt somatic symptoms to express emotional distress if they observe their parents or other family members using similar strategies. Parental medical illness is associated with childhood somatization.

Family Factors

Parents of children with somatoform disorders might present with a persistent fear of disease and a conviction about its presence. Other common family factors include achievement-oriented families with high expectations for their children, psychologically inarticulate families, a pattern of overinvolved or enmeshed family interactions, and role reversal in which the child adopts a parental role.

Stressful Life Events

Significant temporally related correlations are found between somatic symptoms and psychosocial stressors, including children subject to high academic expectations, social pressures, family conflict, physical injury, family illness, parental absence, and other significant losses.

Individual

Childhood Physical Illness

There is a connection between childhood physical illness and the later development of somatization. Children who tend to somatize might have a tendency to experience normal somatic sensations as intense, noxious, and disturbing, referred to as somatosensory amplification. Children with somatoform disorders often have histories of disabling and poorly explained physical symptoms.

Temperament and Coping Styles

Somatic symptoms are more common in children who are conscientious, sensitive, insecure, and anxious and in those who strive for high academic achievement. Somatization can also occur in youngsters who are unable to verbalize emotional distress. Somatic symptoms are often seen as a form of psychologic defense against intrapsychic distress that allows the child to avoid confronting anxieties or conflicts, a process referred to as primary gain. Primary gain is obtained by keeping the conflict from consciousness and minimizing anxiety. The symptoms can also lead to secondary gain if the symptom results in the child’s being allowed to avoid unwanted responsibilities or consequences.

Learned Complaints

Somatic complaints may be reinforced, for example, through a decrease in responsibilities or expectations by others and/or through receiving attention and sympathy as a result of the physical symptoms. Many youngsters have an antecedent true underlying general medical condition that may then be reinforced by parental and/or peer attention as well as additional medical attention in the form of unnecessary tests and investigations.

Assessment

Medical

The medical evaluation of suspected psychosomatic illness should include an assessment of biologic, psychologic, social, and developmental realms both separately and in relation to each other. A comprehensive medical work-up to rule out serious physical illness must be carefully balanced with efforts to avoid unnecessary and potentially harmful tests and procedures. Although the likelihood of finding physical illness in patients with somatoform disorders at initial diagnosis is less than 10%, certain physical illnesses should be considered, such as Lyme disease (Chapter 214), systemic lupus erythematosus (Chapter 152), multiple sclerosis (Chapter 593), infectious mononucleosis (Chapter 246), irritable bowel syndrome (Chapter 334), migraine (Chapter 588.1), and seizure disorders (Chapter 586).

The presence of a physical illness does not exclude the possibility of somatization having an important role in the child’s presentation. Somatic symptoms early in a disease course that can be directly attributed to a specific physical illness (e.g., acute respiratory illness) can evolve into psychologically based symptoms, particularly in situations in which the child experiences benefit from adopting the sick role. Somatic symptoms can also occur in excess of what would be expected of the symptoms experienced in true physical illness. Physical findings can occur secondary to the effects of a somatoform disorder (e.g., disuse atrophy).

Psychologic

Assessment of psychosomatic illness should consider inconsistent findings in the medical evaluation, the presence of psychosocial stressors, the presence of comorbid depressive or anxiety disorders, a past history of somatization in the child and/or family, a symptom model of illness behavior in the family, and the presence of secondary gain or reinforcement of physical illness. The presence of any one risk factor does not conclusively prove the presence of a somatoform disorder; psychiatric and social risk factors can increase the diagnostic likelihood.

If somatization is suspected, psychiatric consultation should be included early in the diagnostic workup. The reason for consultation should be carefully explained to the family to help avoid the parents’ perception that their child’s symptoms are not being taken seriously by the pediatric team (i.e., “it’s in her head”). It should be explained that the goal of the psychiatric consultation is to understand the origins of the child’s distress, why the child uses somatization as a way to express the distress, what perpetuates it, and which treatments are likely to be most effective.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Conversion disorder denotes the loss or alteration of physical functioning without demonstrable organic pathology (see Table 20-3). It occurs in adolescence or adulthood, although numerous childhood cases have been reported. Conversion reactions usually start suddenly, can often be traced to a precipitating environmental event, and can end abruptly after a short duration. Voluntary musculature and organs of special sense are the most common target sites for expressions of conversion reactions. Such reactions can take the form of blindness, paralysis, diplopia, and postural or gait disturbances. Pseudoseizures are a common manifestation of a conversion disorder.

Physical examination often fails to reveal objective abnormalities. Histories might reveal a close relationship with someone who exhibited similar symptoms or had a recent episode of acute illness. Findings inconsistent with organic pathology are often seen. Deep tendon reflexes can be elicited in a paralyzed limb, or pupillary responses to light can be elicited in patients who report blindness. Video electroencephalography and postictal serum prolactin levels (elevated in true seizures) are useful in diagnosing pseudoseizures. Abasia-astasia is a conversion disorder manifest as an inability to stand or walk.

Vulnerability to conversion disorders is not clearly linked to any specific cause, although anxiety and family disturbance can be factors. Children with conversion disorders are highly suggestible, which often helps in treatment. Cultural background affects how illness and distress are expressed and should be considered before diagnosing conversion disorder. Follow-up studies indicate that about 30% of children with a diagnosis of conversion disorder are later found to have a medical disorder that can explain the original symptoms.

In somatoform pain disorder, pain is the primary physical symptom (see Table 20-4). These disorders are characterized by reoccurrence. Prevalence studies suggest that 11% of boys and 15% of girls have ongoing somatic symptoms. Recurrent abdominal pain accounts for 2-4% of all pediatric visits and headaches for an additional 1-2%. Most of these children do not have any positive clinical findings.

The primary differential diagnosis of psychosomatic illness is between that of somatoform disorder and a physical illness. Mood and anxiety disorders often include the presence of physical symptoms that tend to remit with treatment of the primary mood or anxiety symptoms and that appear distinct from physical complaints seen in somatoform disorders.

Additional diagnoses to consider include malingering and factitious disorders. Malingering, which is very rare in the pediatric setting, can be distinguished from somatoform disorders by looking at the motivation for the symptoms. Persons who are malingering will intentionally produce or exaggerate physical symptoms to receive some external reward. Persons with factitious disorder on the other hand are not motivated by external rewards but instead have an intrapsychic need to remain in the sick role (Table 20-5). Factitious disorders cause somatic and/or psychologic symptoms that are deliberately fabricated in the absence of any potential gain to the patient, other than the benefit of assuming the sick role (see Table 20-5). Munchausen syndrome is an example of a chronic factitious disorder typically seen in adults who persist in seeking medical treatments, including surgery, despite the lack of any real disease. Factitious disorder by proxy is a variant in which parents induce physical symptoms in their children in order to assume the sick role by proxy (Chapter 37.2). In such cases infants and young children can present with fractures, poisonings, persistent episodes of apnea, and other unusual ailments. It is considered a form of child abuse, which can be lethal, and must be reported to the appropriate authorities.

Table 20-5 CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF FACTITIOUS DISORDER

CODE BASED ON TYPE

From Kliegman RM, Marcdante KJ, Jenson HB, et al, editors: Nelson essentials of pediatrics, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2006, Elsevier/Saunders, p 84.

Treatment

It is generally believed that effective treatment needs to incorporate a number of different treatment modalities to target the factors that are believed to be associated with the development of somatization. Given the “diagnostic uncertainty” in these disorders, a multidisciplinary approach is recommended, including a stepwise plan for developing an integrated medical and psychiatric treatment strategy to somatoform disorders (Table 20-6).

Table 20-6 STEPWISE APPROACH TO DEVELOPING AN INTEGRATED MEDICAL AND PSYCHIATRIC TREATMENT APPROACH TO SOMATOFORM DISORDERS

COMPLETE MEDICAL AND PSYCHIATRIC ASSESSMENTS

CONVENE AN INFORMING CONFERENCE WITH THE FAMILY

IMPLEMENT TREATMENT INTERVENTIONS IN BOTH MEDICAL AND PSYCHIATRIC DOMAINS

Modified from DeMaso DR, Beasley PJ; The somatoform disorders. In Klykylo WM, Kay JL, Rube DM, editors: Clinical child psychiatry, ed 2, London, 2005, John Wiley & Sons, p 481, Table 26.3.

Education of the Patient and Family

With completion of the medical and psychologic assessments, it is crucial to present the findings to the patient and his or her family. The etiology of the child’s symptoms should be reframed in a broader biopsychosocial understanding through an “informing conference” where the findings are conveyed to the family. It is critical to give both a physical and emotional interpretation of the child’s symptoms in a supportive and nonjudgmental manner. It is important for the family to directly hear from the pediatric practitioner that the symptoms are not solely the result of a physical condition, thereby facilitating acceptance of the role of psychologic factors.

It is not unusual for parents to be doubtful or rejecting of the formulation and proposed treatment. In these instances it is helpful to gently explore the source of the parent’s resistance. Common reasons include previous errors on the part of health care providers leading to lack of trust, the family’s past experience of serious physical illness that can create a pattern of anxiety and hypervigilance, and concerns about the stigma of being labeled with a mental health illness. It is particularly important not to come across as dismissive of the family’s concerns or the child’s symptoms or suffering. It may be extremely beneficial to devote extra time to further discussion, clarification, education, and normalization of the child’s presentation.

Regular team meetings should be encouraged to maintain close communication between health care providers and minimize inconsistencies and miscommunications that have the potential to increase the patient’s and family’s mistrust and frustration.

Implementing a Rehabilitation Model

A rehabilitation model approach provides a useful framework for the treatment that shifts the focus away from finding a cure for symptoms and instead emphasizes a return to normal adaptive functioning. This includes increased activities of daily living, improved nutrition, enhanced mobility, return to school, and socialization with peers. It is generally counterproductive to adopt a confrontational approach or try to talk patients into giving up their symptoms. Unlike malingering and factitious disorders, somatoform symptoms are not consciously produced and they are experienced as “real suffering” by the patient. Any implication that the symptoms are not real can lead to increased frustration and escalation of symptoms.

Treatment approaches include the use of intensive physical and occupational therapies that emphasize the recovery of function. Behavioral modification approaches include increasing attention and reward for adaptive functioning as well as reducing environmental reinforcers and unnecessary medical interventions to minimize the sick role. Relaxation strategies, biofeedback, hypnosis, and/or integrative therapies (e.g., acupuncture and massage therapy) are also useful.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy, individual psychotherapy, and/or family therapy can help a child adjust to the stress of the illness and to learn new coping strategies. Individual psychotherapy can play an important role in helping change a child’s erroneous cognitions about his or her ability to resume functioning. Patients are encouraged to express their underlying emotions and to develop alternative ways to express their feelings of distress.

Psychotropic interventions may be beneficial if there is evidence of underlying or co-morbid depression or anxiety.

When the child is being managed as an outpatient, regularly scheduled visits to the pediatric practitioner can help alleviate anxiety and potentially reduce the frequency of unnecessary emergency department visits, diagnostic work-ups, and inpatient hospitalizations. It is also important to establish regular contact and liaison with key school personnel to provide guidance and education on how to address the child’s physical symptoms and complaints in the school setting. Collaborative models of health care that integrate mental health consultation within the primary care setting may be especially helpful for this group of patients and families.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Beasley PJ, DeMaso DR. Conversion and pain disorders. In: Zaoutis LB, Chang VW, editors. Comprehensive pediatric hospital medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007:1051-1055.

Campo J, Shafer S, Lucas A, et al. Managing pediatric mental disorders in primary care: a stepped collaborative care model. J Am Psych Nurses Assoc. 2005;11(5):1-7.

Dahlquist L, Switkin M. Chronic and recurrent pain. In: Roberts MC, editor. Handbook of pediatric psychology. ed 3. New York: Guilford; 2003:198-215.

DeMaso DR, Martini DR, Cahen LA, et al. Work Group on Quality Issues: Practice parameter for the psychiatric assessment and management of physically ill children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc. 2009;48:213-233.

DeMaso DR, Beasley PJ. The somatoform disorders. In: Klykylo WM, Kay JL, editors. Clinical child psychiatry. London: John Wiley & Sons; 2005:471-486.

Shaw RJ, Dayal S, Hartman JK, et al. Factitious disorder by proxy: a pediatric falsification condition. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 2008;16:215-224.

Spratt EG, DeMaso DR. Somatoform disorder, somatization (website). http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/918628-overview. Accessed February 12, 2010

Shaw RJ, DeMaso DR. Mental health consultation with physically ill children and adolescents. In: Shaw RJ, DeMaso DR, editors. Clinical manual of pediatric psychosomatic medicine. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2006.

Wood BL. Physically manifested illness in children and adolescents: a biobehavioral family approach. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2001;10:543-562.