Chapter 21 Rumination, Pica, and Elimination (Enuresis, Encopresis) Disorders

21.1 Rumination Disorder

Rumination disorder is defined as the repeated regurgitation and rechewing of food for a period of at least 1 mo following a period of normal functioning. The rumination is not due to an associated gastrointestinal illness or other general medical condition (e.g., esophageal reflux). It does not occur exclusively during the course of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. Malnourishment with resultant weight loss or growth delay is a hallmark of this disorder. If the symptoms occur exclusively during the course of mental retardation or a pervasive developmental disorder, they must be sufficiently severe to warrant independent clinical attention.

Epidemiology

Rumination is a rare disorder that is potentially fatal, and some reports indicate that 5-10% of affected children die. In otherwise healthy children, this disorder typically appears in the 1st yr of life, generally between the ages of 3 and 6 mo. The disorder is more common in infants with severe mental retardation than in those with mild or moderate mental retardation.

Etiology and Differential Diagnosis

Proposed causes of rumination disorder include a disturbed relationship with primary caregivers; lack of an appropriately stimulating environment; and learned behavior reinforced by pleasurable sensations, distraction from negative emotions, and/or inadvertent reinforcement (attention) from primary caregivers. The differential diagnosis includes congenital gastrointestinal system anomalies, pyloric stenosis, Sandifer’s syndrome, increased intracranial pressure, diencephalic tumors, adrenal insufficiency, and inborn errors of metabolism.

Treatment

Treatment begins with a behavioral analysis to determine if the disorder serves as self-stimulation or is socially motivated. The behavior might begin as self-stimulation, but it subsequently becomes reinforced by the social attention given to the behavior. Treatment is generally directed at reinforcing correct eating behavior and minimizing attention to rumination. Aversive conditioning techniques (e.g., withdrawal of positive attention) are useful when a child’s health is jeopardized. Successful treatment requires the child’s primary caregivers to be involved in the intervention. The caretakers need counseling around responding adaptively to the child’s behavior as well as altering any maladaptive responses. There is no current evidence supporting a psychopharmacologic response to these disorders.

21.2 Pica

Pica involves the persistent eating of nonnutritive substances (e.g., plaster, charcoal, clay, wool, ashes, paint, earth). The eating behavior is inappropriate to the developmental level (e.g., the normal mouthing and tasting of objects in infants and toddlers) and not part of a culturally sanctioned practice.

Epidemiology

Pica appears to be more common in children with mental retardation, pervasive developmental disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and other neuropsychiatric disorders (e.g., Kleine-Levin syndrome, schizophrenia). It usually remits in childhood but can continue into adolescence and adulthood. Geophagia (eating earth) is associated with pregnancy and is not seen as abnormal in some cultures (e.g., rural or preindustrial societies in parts of Africa and India). Children with pica are at increased risk for lead poisoning (Chapter 702), iron-deficiency anemia (Chapter 449), obstruction, dental injury, and parasitic infections.

Etiology

Numerous etiologies have been proposed but not proved, ranging from psychosocial causes to physical ones. They include nutritional deficiencies (e.g., iron, zinc, and calcium), low socioeconomic factors (e.g., lead paint), child abuse and neglect, family disorganization (e.g., poor supervision), psychopathology, learned behavior, underlying (but undetermined) biochemical disorder, and cultural and familial factors.

Treatment

A combined medical and psychosocial approach is generally indicated for pica. The sequelae related to the ingested item can require specific treatment (e.g., lead toxicity, iron-deficiency anemia, parasitic infestation). Ingestion of hair can require medical or surgical intervention for a gastric bezoar (Chapter 326). Nutritional education, cultural factors, psychologic assessment, and behavior interventions are important in developing an intervention strategy for this disorder.

Ellis CR, Schnoes CJ. Eating disorder, rumination, 2006 (website). http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/916297-overview. Accessed February 12, 2010

21.3 Enuresis (Bed-Wetting)

Enuresis is defined as the repeated voiding of urine into clothes or bed at least twice a week for at least 3 consecutive months in a child who is at least 5 yr of age. The behavior is not due exclusively to the direct physiologic effect of a substance (e.g., a diuretic) or a general medical condition (e.g., diabetes, spina bifida, a seizure disorder). Diurnal enuresis defines wetting while awake and nocturnal enuresis refers to voiding during sleep. Primary enuresis occurs in children who have never been consistently dry through the night, whereas secondary enuresis refers to the resumption of wetting after at least 6 months of dryness. Monosymptomatic enuresis has no associated daytime symptoms (urgency, frequency, daytime enuresis), and nonmonosymptomatic enuresis, which is more common, often has at least one subtle daytime symptom. Monosymptomatic enuresis is rarely associated with significant organic underlying abnormalities.

Normal Voiding and Toilet Training

Urine storage consists of sympathetic and pudendal nerve–mediated inhibition of detrusor contractile activity accompanied by closure of the bladder neck and proximal urethra with increased activity of the external sphincter. The infant has coordinated reflex voiding as often as 15-20 times per day. Over time, bladder capacity increases. In children up to the age of 14 yr, the mean bladder capacity in ounces is equal to the age (in years) plus 2.

At 2-4 yr, the child is developmentally ready to begin toilet training. To achieve conscious bladder control, several conditions must be present: awareness of bladder filling, cortical inhibition (suprapontine modulation) of reflex (unstable) bladder contractions, ability to consciously tighten the external sphincter to prevent incontinence, normal bladder growth, and motivation by the child to stay dry. The transitional phase of voiding is the period when children are acquiring bladder control. Girls typically acquire bladder control before boys, and bowel control typically is achieved before bladder control.

Epidemiology

Prevalence estimates vary significantly. At age 5 yr, 7% of boys and 3% of girls have enuresis; by age 10 yr the percentages are 3% and 2%, respectively: by age 18 yr, 1% for men and less than 1% for women. Primary enuresis accounts for 85% of cases. Enuresis is more common in lower socioeconomic groups, in larger families, and in institutionalized children. There is an estimated spontaneous cure rate of 14-16% annually. Diurnal enuresis is more common in girls and rarely occurs after the age of 9 yr; overall, 25% of children have diurnal enuresis.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Secondary etiologies of urinary incontinence include urinary tract infections (UTIs), chronic kidney disease, hypercalcemia, hypokalemia, chemical urethritis, constipation, diabetes mellitus or insipidus, sickle cell anemia, seizures, pinworm infection, spinal dysraphism, neurogenic bladder, hyperthyroidism, sleep-disordered breathing, drugs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, valproic acid, clozapine) and giggle or stress incontinence. Children with combined nocturnal and diurnal enuresis are more likely to have abnormalities of the urinary tract, making ultrasonography or uroflowmetry indicated. Otherwise, anatomic abnormalities are rarely associated with either nocturnal or diurnal enuresis such that invasive studies are generally contraindicated. Urinalysis and urine culture will rule out infectious causes and the elevated urine osmolality associated with diabetes mellitus.

Etiology

The cause of enuresis likely involves biologic, emotional, and learning factors. Compared with a 15% incidence of enuresis in children from nonenuretic families, 44% and 77% of children were enuretic when one or both parents, respectively, were themselves enuretic. Twin studies show a marked familial pattern, with documented concordance rates of 68% in monozygotic twins and 36% in dizygotic twins. Linkage studies have implicated several chromosomes with varying patterns of transmission.

Children with nocturnal enuresis might hyposecrete arginine vasopressin (AVP) and may be less responsive to the lower urine osmolality associated with fluid loading. Many affected children also appear to have small functional bladder capacity. There is some support for a relationship among sleep architecture, diminished capacity to be aroused from sleep, and abnormal bladder function. A subgroup of patients with enuresis has been identified in whom there is no arousal to bladder distention and an unusual pattern of uninhibited bladder contractions before the enuretic episode. One specific sleep disorder, sleep apnea, has been associated with enuresis (Chapter 17). Although the mechanism is unknown, central nervous system immaturity with delays in motor and language milestones appears to be a relevant etiology of enuresis for some children.

Psychosocial stressors may be contributory. Children generally have secondary enuresis in the context of significant life stress or traumatic experiences (e.g., divorce, school trauma, physical or sexual abuse, hospitalization). Psychologic factors can be central in the rare instance in which family disorganization or neglect has resulted in there never having been a reasonable effort made at toilet training. Children with enuresis have a higher incidence of psychiatric disorders than those without enuresis, although no single disorder accounts for the difference. There is some support for enuresis being a cause of psychologic disturbance, rather than an effect of the disturbances, as emotional and behavioral functioning tends to improve significantly once enuresis resolves.

Children during their early years must master the learning task of controlling the reflexive behavior of urination. Children with enuresis have difficulty in learning this control.

Children with enuresis should be evaluated with a detailed history and physical exam, taking into consideration the underlying organic causes of secondary enuresis (see earlier). Particular attention should be paid to manifestations of UTIs; chronic kidney disease; spinal cord disorders; constipation; and the thirst, polyuria, and polydipsia associated with both type of diabetes. Laboratory evaluation should include a urinalysis to check for glycosuria or a low specific gravity; in children with daytime symptoms, bladder ultrasonography should be performed when the bladder is perceived to be full and after voiding.

Treatment

Given the steady progression in the spontaneous remission rate of enuresis each year, there is some question as to whether enuresis should be treated. Family conflict, parent-child antagonism, and/or peer teasing due to the enuresis are good reasons to institute treatment for enuresis with resultant beneficial effects on a child’s well-being and self-esteem. Daytime wetting, abnormal voiding (unusual posturing, discomfort, straining, and/or a poor urine stream), a history of UTIs and/or evidence of infection on urinalysis or culture, and genital abnormalities are indications for urologic referral and treatment.

The treatment of monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis should be marked by a conservative, gentle, and patient approach. Treatment can begin with parent-child education, charting with rewards for dry nights, voiding before bedtime, and night awakening 2-4 hr after bedtime, while at the same time making sure that parents do not punish the child for enuretic episodes (Table 21-1). In addition, the child should be encouraged to avoid holding urine and to void frequently during the day (to avoid day wetting). These children also need ready access to school toilets. Furthermore, if constipation and fecal impaction are problems (Chapter 22.4), children should be encouraged to have a daily bowel movement and taught optimal relaxation of pelvic floor muscles to improve bowel emptying.

Table 21-1 TREATMENT REGIMEN FOR MONOSYMPTOMATIC NOCTURNAL ENURESIS

From Chandra MM: Enuresis and voiding dysfunction. In Burg FD, Ingelfinger JR, Polin RA, et al, editors: Current pediatric therapy, ed 18, Philadelphia, 2006, Elsevier/Saunders, p 591.

If this approach fails, urine alarm treatment is recommended. Application of an alarm for a period of 8-12 wk can be expected to result in a 75-95% success in the arrest of bedwetting. The underlying conditioning principle likely lies in the alarm’s being an annoying awakening stimulus that causes the child to awaken in time to go to the bathroom and/or retain urine in order to avoid the aversive stimulus. Urine alarm treatment has been shown to be of equal or superior effectiveness when compared to all other forms of treatment. Relapse rates are approximately 40%, with the simplest response being a second alarm course as well as considering the addition of intermittent schedules of reinforcement or the use of overlearning (drinking just before bedtime).

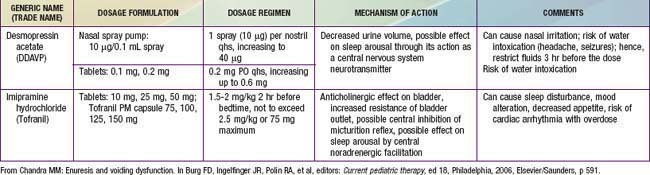

Pharmacotherapy for nocturnal enuresis is second-line treatment (Table 21-2). Desmopressin acetate (DDAVP) is a synthetic analog of the antidiuretic hormone (ADH) vasopressin, which decreases nighttime urine production. The fast action of DDAVP suggests a role for special occasions (e.g., sleepovers), when rapid control of bedwetting is desired. Unfortunately, the relapse rate is high when DDAVP is discontinued. DDAVP is also associated with rare side effects of hyponatremia and water intoxication, with resulting seizures. Although imipramine has some usefulness, less than 50% of children respond, and most relapse when the medication is discontinued. Bothersome side effects and potential lethality in overdose also limit this medication’s usefulness. Much less commonly used, oxybutynin and tolterodine are antimuscarinic drugs, which may be effective by reducing bladder spasm and increasing bladder capacity.

Diurnal Incontinence

Daytime incontinence not secondary to neurologic abnormalities is common in children. At age 5 yr, 95% have been dry during the day at some time and 92% are dry. At 7 yr, 96% are dry, although 15% have significant urgency at times. At 12 yr, 99% are dry during the day. The most common cause of daytime incontinence is a pediatric unstable bladder (also termed uninhibited or overactive bladder, bladder spasms).

Important points in the history include the pattern of incontinence, including the frequency, the volume of urine lost during incontinent episodes, whether the incontinence is associated with urgency or giggling, whether it occurs after voiding, and whether the incontinence is continuous. The frequency of voiding and whether there is nocturnal enuresis, a strong, continuous urinary stream, or sensation of incomplete bladder emptying should be assessed. A diary of when the child voids and whether he or she was wet or dry is helpful. Other urologic problems such as UTIs, reflux, neurologic disorders, or a family history of duplication anomalies should be assessed. Bowel habits also should be evaluated, because incontinence is common in children with constipation and/or encopresis. Diurnal incontinence can occur in girls with a history of sexual abuse.

Physical examination is directed at identifying signs of organic causes of incontinence: short stature, hypertension, enlarged kidneys and/or bladder, constipation, labial adhesion, ureteral ectopy, back or sacral spinal anomalies, and neurologic signs. A urinalysis and/or culture should be performed to check for infection. In some cases, assessing the postvoid residual urine volume or urinary flow rate is appropriate. Imaging is reserved for children who have significant physical findings, a family history of urinary tract anomalies, or UTIs, and for those who do not respond to therapy appropriately. A renal ultrasonogram with or without a voiding cystourethrogram is indicated. Urodynamics should be performed if there is evidence of neurologic disease and may be helpful if empiric therapy is ineffective.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with enuresis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1540-1550.

Butler RJ, Heron J. The prevalence of infrequent bedwetting and nocturnal enuresis in childhood. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2008;42:257-264.

Humphreys M, Reinberg Y. Contemporary and emerging drug treatments for urinary incontinence in children. Pediatric Drugs. 2005;7:151-162.

Jackson EC. Is lack of bladder inhibition during sleep a mechanism of nocturnal enuresis? J Pediatr. 2007;151:559-560.

Lane W, Robson M. Evaluation and management of enuresis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1429-1436.

Rocha MM, Costa NK, Silvares EF. Changes in parents’ and self-reports of behavioral problems in Brazilian adolescents after behavioral treatment with urine alarm for nocturnal enuresis. Int Braz J Urol. 2008;34:749-757.

Schulz-Juergensen S, Rieger M, Schaeffer J, et al. Effect of 1-desamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin on prepulse inhibition of startle supports a central etiology of primary monosymptomatic enuresis. J Pediatr. 2007;151:571-574.

Wang QW, Wen JG, Zhang RL, et al. Family and segregation studies: 411 Chinese children with primary nocturnal enuresis. Pediatr Int. 2007;49:618-622.

21.4 Encopresis

The definition of encopresis requires the voluntary or involuntary passage of feces into inappropriate places at least once a month for 3 consecutive months once a chronologic or developmental age of 4 yr has been reached. Encopresis is not diagnosed when the behavior is due exclusively to the direct effects of a substance (e.g., laxatives) or a general medical condition (except through a mechanism involving constipation). Subtypes include retentive encopresis (with constipation and overflow incontinence) representing 65-95% of cases, and nonretentive encopresis (without constipation and overflow incontinence). Encopresis can persist from infancy onward (primary) or can appear after successful toilet training (secondary).

Clinical Manifestations

Children with encopresis often present with reports of underwear soiling, and many parents initially presume that diarrhea, rather than constipation, is the cause. In retentive encopresis, associated complaints of difficulty with defecation, abdominal or rectal pain, impaired appetite with poor growth, and urinary (day and/or night) incontinence are common. Children often have large bowel movements that obstruct the toilet. There may also be retentive posturing or UTIs.

Nonretentive encopresis is more likely to occur as a solitary symptom and have associated primary underlying psychologic problems. Children with encopresis can present with poor school performance and attendance that is triggered by the scorn and derision from schoolmates because of the child’s offensive odor.

Epidemiology

Functional encopresis does not begin before age 4 yr. The prevalence of encopresis is approximately 4% in 5-6 yr olds and 1.5% in 11-12 yr olds. Encopresis is 4-5 times more common in boys than in girls and tends to decrease with age.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The first priority in evaluating a child with fecal incontinence is to rule out a general medical condition (e.g., tethered cord, Chapter 598.1) causing the problem. The presence of fecal retention should then be determined. A positive finding on rectal examination is sufficient to document fecal retention, but a negative finding requires plain abdominal films (Fig. 21-1). Additional diagnostic studies are rarely indicated.

Etiology

The etiology of encopresis lies in a combination of biologic, emotional, and learning factors. Although by definition encopresis is fecal incontinence based on a functional disorder, abnormal gastrointestinal mobility or sensation, hereditary predispositions, and developmental delays have been postulated as playing an etiologic role in encopresis. Although most children with encopresis do not have an emotional problem, a great deal of turmoil and conflict within the family is commonly found. Whether this turmoil is an effect or the cause is unclear; nevertheless, the common accompanying feelings of distress and low self-esteem improve with successful treatment.

Manipulative soiling appears to follow a reinforcement model. Complaints may lead to being excused from stressful circumstances. Stress and anxiety, along with an inherited tendency to react with intestinal distress, can lead to impaired bowel control and to loss of previously learned toileting behavior. Poor dietary choices and failure to establish good toilet habits can further contribute to the development of encopresis.

Treatment

The standard medical treatment of retentive encopresis involves the clearance of impacted fecal material followed by the short-term use of mineral oil or laxatives to prevent further constipation (Tables 21-3 and 21-4). There needs to be a focus on adherence with regular postprandial toilet sitting and adoption of a balanced diet. Once impacted stool is removed, the combination of constipation management and simple behavior therapy is successful in the majority of cases, although it is often a period of months before soiling stops completely. Compliance can wane, and failure of this standard treatment approach sometimes requires more intensive intervention, with a special emphasis on adherence to a high-fiber diet and family support for behavioral change. Keeping records of the child’s progress is necessary. In cases where behavioral or psychiatric problems are evident, group or individual psychotherapy may be necessary.

Table 21-3 SUGGESTED MEDICATIONS AND DOSAGES FOR DISIMPACTION

| MEDICATION | AGE | DOSAGE |

|---|---|---|

| RAPID RECTAL DISIMPACTION | ||

| Glycerin suppositories | Infants and toddlers | |

| Phosphate enema | <1 yr | 60 mL |

| >1 yr | 6 mL/kg bodyweight, up to 135 mL twice | |

| Milk of molasses enema | Older children | (1 : 1 milk : molasses) 200-600 mL |

| SLOW ORAL DISIMPACTION IN OLDER CHILDREN | ||

| Over 2-3 Days | ||

| Polyethylene glycol with electrolytes | 25 mL/kg bodyweight/hr, up to 1000 mL/h until clear fluid comes from the anus | |

| Over 5-7 Days | ||

| Polyethylene without electrolytes | 1.5 g/kg bodyweight per day for 3 days | |

| Milk of magnesia | 2 mL/kg bodyweight twice/day for 7 days | |

| Mineral oil | 3 mL/kg bodyweight twice/day for 7 days | |

| Lactulose or sorbitol | 2 mL/kg bodyweight twice/day for 7 days | |

From Loening-Baucke V: Functional constipation with encopresis. In Wyllie R, Hyams JS, Kay M, editors: Pediatric gastrointestinal and liver disease, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2006, Elsevier/Saunders, p 183.

Table 21-4 SUGGESTED MEDICATIONS AND DOSAGES FOR MAINTENANCE THERAPY OF CONSTIPATION

| MEDICATION | AGE | DOSE |

|---|---|---|

| FOR LONG-TERM TREATMENT (YEARS): | ||

| Milk of magnesia | >1 mo | 1-3 mL/kg body weight/day, divide in 1-2 doses |

| Mineral oil | >12 mo | 1-3 mL/kg body weight/day, divided in 1-2 doses |

| Lactulose or sorbitol | >1 mo | 1-3 mL/kg body weight/day, divide in 1-2 doses |

| Polyethylene glycol 3350 (MiraLax) | >1 mo | 0.7 g/kg body weight/day, divide in 1-2 doses |

| FOR SHORT-TERM TREATMENT (MONTHS): | ||

| Senna (Senokot) syrup, tablets | 1-5 yr | 5 mL (1 tablet) with breakfast, max 15 mL daily |

| 5-15 yr | 2 tablets with breakfast, maximum 3 tablets daily | |

| Glycerin enemas | >10 yr | 20-30 mL/day (1/2 glycerin and 1/2 normal saline) |

| Bisacodyl suppositories | >10 yr | 10 mg daily |

From Loening-Baucke V: Functional constipation with encopresis. In Wyllie R, Hyams JS, Kay M, editors: Pediatric gastrointestinal and liver disease, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2006, Elsevier/Saunders, p 185.

From the outset, parents should be actively encouraged to reward the child for adherence to a healthy bowel regimen and to avoid power struggles. In addition, they should be instructed not to respond to soiling with retaliatory or punitive measures, because children are likely to become angry, ashamed, and resistant to intervention.

Whereas around 80% of children become continent on the above regimen, many relapse when removed from the protocol. Children with behavioral problems are particularly prone to treatment failure, necessitating referral for psychologic intervention and behavioral management (e.g., behavior programs and/or biofeedback).

For children with chronic diarrhea and/or irritable bowel syndrome where stress and anxiety play a major role, stress reduction and learning effective coping strategies can play an important role in responding to the encopresis. Relaxation training, stress inoculation, assertiveness training, and/or general stress management procedures can be helpful.

In the infrequent case where the child is using soiling as a way of manipulating the environment, a combination of behavioral and family therapy is indicated. Reinforcement for soiling behavior needs to be identified and removed, and family counseling and intervention are required to do so.

Boners ME, Tabbers MM, Benninga MA. Functional nonretentive fecal incontinence in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:5-13.

Reid H, Bahar RJ. Treatment of encopresis and chronic constipation in young children: clinical results from interactive parent-child guidance. Clin Pediatr. 2006;45:157-164.

Voskuijl WP, Reitsma JB, van Ginkel R, et al. Longitudinal follow-up of children with functional nonretentive fecal incontinence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:67-72.