Chapter 39 Chronic Illness in Childhood

Epidemiology

Patterns of chronic illness in childhood are both complex and dynamic. Compared to chronic disease in adults, serious chronic illness in children is less common and widely heterogeneous. This has profound implications for the organization of children’s health services, as pediatricians have the difficult task of identifying and caring for children with unusual and varied conditions. Accordingly, child health services have become far more reliant on standardized screening programs and formal systems of referral to regional specialty care programs than are health care systems for adults. Pediatrics has been characterized by rapid progress in preventing serious acute illnesses and in extending the lives of children who previously would have succumbed to their illness early in life. These factors have made the epidemiology of childhood far more dynamic than that of the adult world.

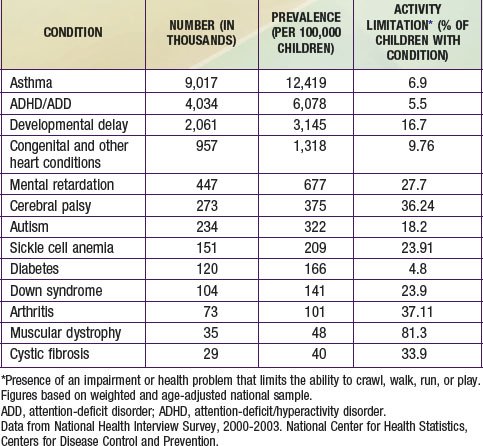

National survey data suggest that 30% of all children have some form of chronic health condition (Table 39-1). If allergies, eczema, minor visual impairments, and other conditions not likely to generate serious consequences are excluded, then between 15% and 20% of all children have a chronic physical, learning, or developmental disorder. Boys have higher rates of chronic illness than do girls. There is considerable variation in the nature and severity of chronic illnesses in children (Table 39-2). The most common serious chronic condition is asthma, with 12% of children having received a diagnosis of asthma at some time in their lives; half of these children were reported to have experienced asthma symptoms in the prior 12 mo (Chapter 138). Mental health and behavioral conditions represent a large and growing number of children with chronic illness. It has been estimated that almost 21% of U.S. children between 9 and 17 yr of age have a diagnosable mental or addictive disorder associated with some impairment; approximately 11% had significant impairment. Estimates suggest that 5% had major depression (Chapter 23) and approximately 6% have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Chapter 30). Overweight is not usually defined as a chronic health condition; however, in 2008 12% of 2-5 yr olds, 17% of 6-11 yr olds, and nearly 18% of all children aged 12 through 19 yr have a body mass index above the 95th percentile (Chapter 44). Co-morbid conditions such as hypertension and a variety of metabolic disorders may exist.

Table 39-1 PREVALENCE AND ACTIVITY LIMITATION FOR SELECTED CHRONIC DISEASES IN CHILDREN <18 YEARS OF AGE: UNITED STATES, 2000-2003

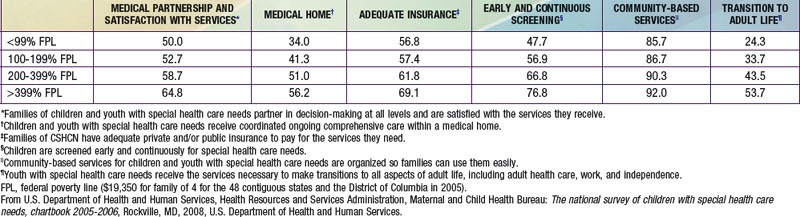

Table 39-2 QUALITY MEASURES FOR HEALTH CARE RECEIVED BY CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL HEALTH CARE NEEDS (CSHCN) BY FAMILY INCOME: UNITED STATES, 2005-2006 (PERCENT MEETING QUALITY MEASURE)

The severity and impact of chronic illnesses can vary significantly. Approximately 9% of all children have activity limitations due to one or more chronic illnesses, which has been relatively stable since 2001. Of these children, 40% have developmental or learning disorders, 35% have chronic physical conditions, and 25% report chronic mental health disorders. Approximately 2% of children have chronic conditions and activity limitation severe enough to meet eligibility criteria for the Supplemental Security Income program. Between 12% and 18% of all children meet the chronic illness and elevated service needs of the children with special health care needs (CSHCN) definition, depending on the data set that is examined.

These current prevalence figures represent a substantial increase in childhood chronic illness in the past several decades. While approximately 9% of children were reported to have a chronic health condition that limited their activities in 2005, the comparable figure in 1960 was only 2%. Although the increase in childhood chronic illness is likely due in part to changes in survey methodologies, improvements in diagnosis, and expanded public awareness of behavioral and developmental disorders, there is strong evidence that the prevalence of certain important chronic child health conditions has increased. Asthma rates rose from <4% in 1980 to 9% in 2007, with the highest rates among the poorest children. The prevalence of ADHD (Chapter 30) and autism (Chapter 28) has also increased considerably. Although improvements in the survival of infants and young children from prematurity, congenital anomalies, and genetic disorders have also contributed to the rising prevalence rates, this source accounts for only a small portion of all chronic illness in childhood.

Chronic illness accounts for a growing portion of child health care expenditures, serious illness, hospitalizations, and deaths among children in the USA. Children with a chronic illness are hospitalized approximately 4 times more often and spend more than 7 times as many days in the hospital as children without a chronic illness. Estimates suggest that chronic illness accounts for the majority of all nontraumatic hospitalizations for children, a figure that has more than doubled in the past 4 decades, and children with chronic illnesses are experiencing increasing lengths of stay. Multiple admissions in any given year have also risen substantially. The majority of all non–trauma related deaths in children are now due to chronic disorders. This historical shift in the distribution of pediatric hospitalization and mortality reflects not only the rise in the prevalence of childhood chronic illness, but also marked reductions in the incidence of serious acute pediatric illness.

Chronic illness is also contributing more profoundly to social disparities in child health. There are somewhat conflicting data on the association of poverty and the prevalence of chronic disorders in children, although most studies suggest a moderate elevation among poor children. Children enrolled in welfare cash assistance programs are more likely to have a chronic illness, and poor and African-American children have greater limitations in activity due to chronic conditions. Latino school-aged children have rates of chronic illness that are similar to non-Latino whites; however, there remains little information on the prevalence and impact of chronic illness and its functional impact among the different subgroups of Latino children as well as subgroups of Asian and Pacific Islanders.

Enhanced Needs of Children with Chronic Illness and Their Families

Although the nature and severity of chronic illness in children is quite heterogeneous, there are important clinical considerations that are common to virtually all such conditions regardless of their specific diagnosis or specialty group.

Financial Costs

The care required by children with serious chronic illnesses is usually associated with high financial costs. Most states have some mechanism to facilitate health insurance coverage for children, although the nature and scope of these programs can vary considerably. A growing number of private and public health insurance plans require deductibles and copayments, which can accumulate rapidly for a child with a chronic illness. Some plans offer coverage up to a designated cost, period of hospitalization, or for a certain number of specialty visits. Once this cap has been reached, a larger portion or all of the costs may be borne by the family. The Family Opportunity Act of 2005 allows families of children with disabilities who are not eligible for Medicaid because their income is too high to buy into the Medicaid program on a sliding scale. This program was created to fill the gap when children are underinsured due to private insurance limiting essential services, such as durable medical equipment and uncovered prescription drugs. The implementation of this program varies widely by state.

Of great importance for children with serious chronic disorders, many new procedures, medications, or therapeutic regimens may be considered “experimental” by some insurers and not covered. Insurance coverage policies often generate strong incentives for hospital rather than outpatient care, even if the latter is indicated. Frequent medical visits and hospitalizations can interfere with parental employment and undermine job performance and security.

Complex Clinical Management

Children with serious chronic disorders usually require intense clinical management both in community and hospital settings. Close surveillance of disease progression, symptoms and functioning, and adverse medication effects often necessitate frequent communication and office visits. Managing hospital admissions and discharge planning may also prove complex and involve a variety of clinicians and community resources. As pressure to reduce hospitalization has grown, the burden on outpatient systems has increased accordingly. An uncoordinated approach to the multitude of required clinical visits can prove highly burdensome to the family and can undermine even the most committed family’s attempts to comply.

Pain

Many seriously ill children suffer from chronic pain (rheumatoid arthritis, spastic cerebral palsy [CP]), recurrent pain during exacerbations of underlying disease (inflammatory bowel diseases, sickle cell anemia), or acute pain related to procedures, surgeries, or diagnostic tests. This pain can alter a child’s affect and influence their academic and social development, while also decreasing the family’s quality of life (Chapter 71). Assessing pain in young children or those with developmental disorders can be difficult and should always consider sociocultural and psychologic factors as well as developmental stage. Because serious, chronic pain is relatively unusual in children, its management may require the involvement of pediatric pain subspecialists who may practice with multidisciplinary teams in regional centers. The emotional toll on parents of children experiencing chronic pain can also be profound and require close attention by medical personnel.

Behavioral and Adjustment Issues

Although chronic illness in children elevates the likelihood that they will experience psychologic and behavioral problems, most children with chronic illness will experience the same level of psychologic and behavioral issues as other children their age. Behavioral and adjustment problems are more likely to occur the earlier the onset of the illness, particularly if it emerges in infancy. The risk of psychologic and behavioral problems does not appear to be associated with the severity of the chronic illness per se. These effects can occur across all diagnoses, although they are more profound for disorders that affect the central nervous system, including cerebral palsy, head trauma, and treatment-related complications that affect the brain, such as chemotherapy for cancer. Children with higher levels of cognitive ability appear to be less likely to develop serious behavioral or adjustment problems. Familial strife and mental illness, particularly depression in the mother, have been associated with an enhanced risk for psychologic and behavioral consequences.

Impact on Families

Like all children, a child with a chronic illness usually brings a mix of challenges and joy to a family. The presence of a chronic illness can add extra burdens, which can be expressed in a variety of forms. First, the daily requirements of care should never be underestimated, particularly when the child is unable to perform tasks such as bathing, dressing, using the toilet, and feeding. Second, the care required by the child with chronic illness may divert needed attention from siblings and strain normal family dynamics. Third, the ultimate burden faced by families of children with a chronic illness is the emotional toll exacted by the daily struggles, pain, and, occasionally, early death that chronic illness can imply. Fourth, among the most difficult attributes of childhood chronic illness is the inherent unpredictability of its course and ultimate impact. Clinicians should be sensitive to how difficult it can be living with a child whose condition can worsen at any moment and without apparent cause. Fifth, children with serious chronic illness and their parents may harbor powerful hopes for new breakthroughs or divine intervention. Clinicians should understand the importance of these hopes for the families under their care and should explore related hopes for lesser, more incremental steps, such as attending school, playing sports, or taking a special trip.

Comprehensive Care and the Medical Home

All children require a clinician who takes responsibility for their comprehensive health care needs. To meet this responsibility, the coordinated implementation of a series of essential practice components, often termed the medical home, is recommended. These services should be provided within a broader system of care that emphasizes partnering in decision-making between the family and medical providers, coordination of services among medical and community service providers, adequate health insurance coverage, ongoing screening for special health care needs, critical educational and community-based services, and special attention to the needs of older children as they transition to adult life and health care systems. Evidence suggests that the extent to which these care requirements are being met for families with children with special health care needs is highly variable (see Table 39-1). Though essential for all children, these practice elements take on special importance for children with chronic disorders and are outlined as follows.

Preventive Services

Primary, preventive care is an essential component of health care for children with chronic disease. Although overall, CSHCN use preventive medical and dental services at rates similar to those of other children, primary preventive services can easily be overlooked in addressing the more specialized needs of these patients. The most common unmet health care need for CSHCN is dental care. Children with chronic disorders are commonly less well immunized than their healthy counterparts. Well child care may be disrupted by visits for acute exacerbations of the chronic disorder and clinicians should carefully evaluate whether the chronic illness or its symptoms are contraindications to immunization. A family’s reliance on specialty services can be so great that the need for primary care services is overlooked. Special effort may be required to ensure the provision of high-quality primary care to children with chronic illness.

Continuity of Care

Children with chronic illnesses are particularly dependent on a stable, ongoing relationship with clinicians and the health care system. The duration and complexity of chronic illness in children require that the clinician responsible for coordinating the child’s care have a good understanding of the child’s clinical history, including patterns of exacerbation and response to medications and other interventions. Continuity of care also serves as a basis for building trust and effective communication between affected families and clinicians, a prerequisite for high-quality care. Practice structures, therefore, should ensure the identification of a principal clinical provider and facilitate the provider’s involvement in all necessary care. Transitioning of care as the child reaches adulthood requires planning and coordination and recognition of the emotional bonds that likely have developed between the child (and his or her family) and the practitioner, which now must be transferred to another provider (Chapter 106.4).

Access to Urgent Care

Clinicians should expect that children with chronic illness will have enhanced requirements for urgent consultation, emergency care, and hospitalization. Practice mechanisms that ensure rapid access to medical consultation both by telephone and office visitation are essential. Procedures for urgent referral to appropriate facilities for emergency evaluation and hospitalization should also be established. This is particularly important in managed care systems that may require primary care referral or approval for care at referral sites.

Access to Specialty Care

Children with chronic illness commonly require specialized care. The need for specialty referral is particularly important in pediatrics because serious disorders are relatively rare in children. In many countries including the USA, there is a shortage of many pediatric subspecialists. Regional systems of specialty referral and hospitalization have been formalized in the past several decades, particularly for perinatal care, pediatric trauma, and children with serious chronic illness. These systems of “regionalized” specialty care have been shown to reduce dramatically morbidity and mortality among affected children. The heavy reliance on specialty care referral enhances the importance of the medical home. Responsive communication between primary care practices and specialty programs is essential, particularly in conveying the reasons for referral, patient history, the nature and findings of the specialty evaluation, hospital course, and the collaborative development of a follow-up management plan.

Enhanced Information Systems

Children with chronic illness often require careful monitoring of their clinical status and the rapid evaluation of exacerbations. On-call and related coverage systems must include immediate access to up-to-date medical record information for children with complex histories and management regimens. Electronic medical records and systems that permit parent or other caretakers routine access to computerized medical record information may also prove useful. Access to current medical information, laboratory results, as well as clinical protocols and decision support algorithms could prove particularly helpful for children with complex health care requirements.

Linkage to Schools, Support Groups, and Community Services

Children with chronic illnesses often have special educational needs and may require the active participation of teachers and school health personnel in medical care plans. An important first step in creating a care plan is to assess the level of medical expertise available at the school site because many schools no longer have a nurse present. Special mechanisms should be established to ensure close coordination with schools, including provisions for collaborative evaluations of needs, monitoring of educational performance and social interactions, and the ongoing refinement of medical and educational management regimens. Clinicians can prevent the isolation many families feel by connecting them to support and advocacy groups composed of other parents with similarly affected children. Such connections have been facilitated by use of the Internet, which can link children and families over wide geographic areas.

Logistic Access

The difficulties that families can experience in transporting children with serious physical or behavioral disorders should never be underestimated. Particularly for older children or those requiring wheelchairs or other equipment, urban public transportation systems may be seriously impractical. In suburban and rural areas, transportation may involve traveling over great distances. For parents who have daytime employment, extended clinic hours may be required. Many communities have implemented innovative transportation programs for families in need of health and social services, particularly when available means of travel to clinical facilities is deemed unsafe or if it requires specially equipped vehicles or the assistance of trained personnel. In a growing number of areas, a variety of forms of telemedicine have enhanced access to medical and particularly, specialty care consultation.

Cultural Sensitivity and Language Concordance (Chapter 4)

Clinicians must possess a basic understanding of the meaning of illness and traditions of healing in the communities they serve. While such cultural competence of individual providers is important, access also depends on creating clinical programs that respond to local perceptions and social institutions. Cultural competence not only reduces the likelihood of misunderstandings and medical errors, but also helps ensure that clinical programs can take full advantage of the many strengths that exist in culturally defined communities.

The most basic element of communication between clinicians and families of children with a chronic illness is that they share a common language. Clinicians should not overestimate their own or a parent’s basic command of a language and must ensure that conveyed information is well understood. Children should not be used as interpreters despite the fact that they often have a better command of English than do their parents. Given the complex issues chronic illness can generate, it is far more useful to integrate trained interpreters into programs for chronically ill children in locations characterized by diverse language groups.

Nondiscrimination in Access and Clinical Decision-Making

Clinicians who care for children with chronic illness must recognize the power of social status to define access to care. A history of inadequate service provision or different levels of service for distinct social groups can generate deep resentment and distrust for the medical system. Many studies have suggested that even when patients have adequate health insurance, poor and minority patients are less likely to be offered recommended diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. While the precise reasons for these observations remain unclear, it is important that provider preconceptions do not replace a careful consideration of the true desires and capabilities of families, particularly in association with new, specialized, or home-based interventions. Strategies to confront these issues include the training and recruitment of minority health providers, educational programs for clinicians, and the active assessment of clinical decision-making and family experiences at clinical facilities.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Council on Children with Disabilities. Care coordination in the medical home: integrating health and related systems of care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1238-1244.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Children with Disabilities. The role of the pediatrician in transitioning children and adolescents with developmental disabilities and chronic illnesses from school to work or college. Pediatrics. 2000;106:854-856.

Bethell CD, Read D, Blumberg SJ, et al. What is the prevalence of children with special health care needs? Toward an understanding of variations in findings and methods across three national surveys. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12:1-14.

Gordon JB, Colby HH, Bartelt T, et al. A tertiary care–primary care partnership model for medically complex and fragile children and youth with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:937-944.

Homer CJ, Klatka K, Romm D, et al. A review of the evidence for the medical home for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e922-e937.

Kastner TA, American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Children with Disabilities. Managed care and children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1693-1698.

Newacheck PW, Kim SE. A national profile of health care utilization and expenditures for children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:10-17.

Palfrey JS, Sofis LA, Davidson EJ, et al. The pediatric alliance of coordinated care: evaluation of a medical home model. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1507-1516.

Perrin JM, Bloom SR, Gortmaker SL. The increase of childhood chronic conditions in the United States. JAMA. 2007;297:2755-2759.

Stein REK, editor. Caring for children with chronic illness. New York: Springer, 1989.

Strickland B, McPherson M, Weissman G, et al. Access to the medical home: results of the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1485-1492.

Van Cleave J, Davis MM. Preventive care utilization among children with and without special health care needs: associations with unmet need. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8:305-311.

Wise PH. The transformation of child health in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;23:9-25.