Chapter 40 Pediatric Palliative Care

According to the World Health Organization, “Palliative care for children is the active total care of the child’s body, mind and spirit, and also involves giving support to the family…Optimally, this care begins when a life-threatening illness or condition is diagnosed and continues regardless of whether or not a child receives treatment directed at the underlying illness.” Provision of palliative care applies not only to children with cancer or cystic fibrosis but also those with diagnoses such as complex or severe cardiac disease, neurodegenerative diseases, or trauma with life-threatening sequelae (Table 40-1). While palliative care is often mistakenly understood as equivalent to end-of-life care, its scope and potential benefit extend before and well after end-of-life care and is applicable throughout the illness trajectory. Palliative care emphasizes optimization of quality of life, communication, and symptom control, aims that may be congruent with maximal treatment aimed at sustaining life.

Table 40-1 CONDITIONS APPROPRIATE FOR PEDIATRIC PALLIATIVE CARE

CONDITIONS FOR WHICH CURATIVE TREATMENT IS POSSIBLE BUT MAY FAIL

CONDITIONS REQUIRING INTENSIVE LONG-TERM TREATMENT AIMED AT MAINTAINING THE QUALITY OF LIFE

PROGRESSIVE CONDITIONS IN WHICH TREATMENT IS ALMOST EXCLUSIVELY PALLIATIVE AFTER DIAGNOSIS

CONDITIONS INVOLVING SEVERE, NONPROGRESSIVE DISABILITY, CAUSING EXTREME VULNERABILITY TO HEALTH COMPLICATIONS

Adapted from Himelstein BP, Hilden JM, Boldt AM, et al: Pediatric palliative care, N Engl J Med 350:1752–1762, 2004.

Such comprehensive physical, psychologic, social, and spiritual care requires an interdisciplinary approach. Worldwide this is possible with creative use of professional and community providers. Organizations such as the Children’s International Project on Palliative/Hospice Services share existing clinical and scientific knowledge in an attempt to establish international standards for palliative care. In the USA, the American Academy of Pediatrics has delineated essential elements of pediatric palliative care. The National Consensus Project released its second edition of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, endorsed by 39 medical, nursing, and social work organizations as well as the International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care.

Approximately 54,000 children (birth to 19 yr) died in 2005 in the USA. This number has remained relatively unchanged over the past several years, and half of the deaths occur in acute-care hospitals. Among children who die from cancer, about 50% die in the hospital and 50% at home. Approximately 65% of childhood AIDS deaths occur in the hospital. In many developing countries, the majority of pediatric deaths occur at home, with or without palliative care.

Pediatric palliative care should be provided across settings, including the hospital, outpatient settings, the home, and sometimes in hospice programs. In the USA, the insurance structure and frequent use of medical technology (e.g., home ventilatory support) precludes formal enrollment of a child on the hospice benefit. A growing number of home care agencies offer palliative care programs that serve as a bridge to hospice services. Some freestanding hospice houses will accept children, although many families and children prefer to be at home, if at all possible, through the end of life. Despite establishment of such programs, provision of palliative care for children is often limited by the availability of clinicians who have training or experience in caring for seriously ill children.

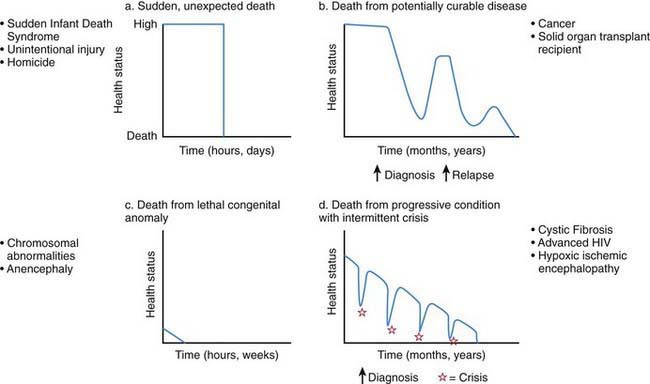

The mandate of the pediatrician and other health care providers to oversee children’s physical, mental, and emotional health and development includes the practice of palliative care for those children who live with a significant possibility of death before adulthood (Fig. 40-1). Many pediatric subspecialists care for children with life-threatening illnesses.

Figure 40-1 Typical illness trajectories for children with life-threatening illness.

(From Field M, Behrman R, editors: When children die: improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families, Washington, DC, 2003, National Academies Press, p 74.)

Compared with adult palliative care, pediatric palliative care has:

Medical and technological advances have resulted in an increase in the number of children who live longer, often with significant dependence on new and expensive technologies. These children have complex chronic conditions across the spectrum of congenital and acquired life-threatening disorders (Chapter 39). Children with complex chronic conditions may benefit from simultaneous palliative and curative therapies. These children, who often survive near-death crises followed by the renewed need for rehabilitative and life-prolonging treatments, are best served by a system that is flexible and responsive to changing needs.

Care Settings

Home care for the child with a life-threatening illness requires 24 hr per day accessibility to experts in pediatric palliative care, a team approach, and an identified coordinator who serves as a link between hospitals, the community, and specialists and who may assist in preventing and/or arranging for hospital admissions, respite care, and increased home care support as needed. Adequate home care support and respite care, though sorely needed, is often not readily available. Furthermore, families may feel using respite care is a personal failure, or they may worry that others cannot adequately care for their child’s special needs.

At the end of life, children and families may need intensive support. This may be provided in the home, hospital, or hospice house. Families need to feel safe and well cared for and given permission, if possible, to choose location of care. In tertiary care hospitals, most children die in the neonatal and pediatric intensive care units (ICUs). The philosophy of palliative care can be successfully integrated into a hospital setting, including the ICU, when the focus of care also includes the prevention or amelioration of suffering and improving comfort and quality of life. All interventions that affect the child and family need to be assessed in relationship to these goals. This proactive approach asks the question “What can we offer that will improve the quality of this child’s life?” instead of “What therapies are we no longer going to offer this patient?” Staff need education, support, and guidance since pediatric palliative care, like other types of intensive care, is an area of specialty. Comprehensive palliative care also requires an interdisciplinary approach that may include nurses, physicians, psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, religious counselors, child-life specialists, and trained volunteers.

Communication, Advance Care Planning, and Anticipatory Guidance

Although accurate prognostication is a particular challenge in pediatrics, the medical team often recognizes a terminal prognosis before the prognosis is understood by parents. This time delay may impede informed decision-making about how the child lives at the end of life. Given the inherent prognostic uncertainty of a life-limiting diagnosis, discussions concerning resuscitation, symptom control, and end-of-life care planning should be initiated when the physician recognizes that a significant possibility of patient mortality exists. These conversations should not happen during a crisis, but should occur well in advance of the crisis or when the patient has recovered from a crisis, but is at high risk for others. Patients and families are most comfortable being cared for by physicians and other care providers with whom they have an established relationship; these individuals may not have had the benefit of palliative care training. The services of a palliative care team or hospice program can be consultative to the primary or subspecialty care team and/or the patient and family, and help alleviate physician discomfort in discussions regarding advanced care planning. A consultative palliative care team provides the family with an opportunity to engage in sensitive conversations that they may feel less comfortable having with their primary team, at least initially. Perhaps resulting from long-standing and highly connected relationships, primary providers and families can be mutually protective of one another, and may not engage in conversations that are perceived as promoting hopelessness. The palliative care team can help to begin conversations about difficult and emotional topics in a manner that concurrently promotes hopefulness.

The population of children who die before reaching adulthood includes a disproportionate number of nonverbal and preverbal children who are developmentally unable to make autonomous care decisions. Although parents are legally the primary decision-maker in most situations in the USA, children should be as fully involved in discussions and decisions about their care as appropriate for their developmental status. Utilizing communication experts, child life therapists, chaplains, social workers, psychologists, or psychiatrist to allow children to express themselves through art, play, music, talk, and writing will enhance the provider’s knowledge of the child’s understanding and hopes. Tools such as “Five Wishes” and “My Wishes” have proven to be useful in helping to gently introduce advance care planning to children, adolescents, and their families (www.agingwithdignity.org/index.php).

The Parents

For parents, compassionate communication with medical providers who understand their child’s illness, treatment options, and family preferences and goals is the cornerstone of caring for children with life threatening illness. During this period of time, one of the most significant relationships is that with the child’s pediatrician, who often has an enduring relationship with the child and family, including healthy siblings. Parents need to know that their child’s pediatrician will not abandon them as the goals of care shift to include palliative care. A family’s goals may shift and change with the child’s evolving clinical condition and other variable factors. A flexible approach rooted in ongoing communication and guidance that incorporates understanding of the family’s values, goals, and religious, cultural, spiritual, and personal beliefs is of paramount importance.

Pediatricians should recognize the important role they have in continuing to care for the child and family as the primary goal of treatment simultaneously may be prolongation of life and comfort, relief of suffering and promoting quality of life. Regular meetings between caregivers and the family are essential in order to reassess and manage symptoms, explore the impact of illness on immediate family members, and provide anticipatory guidance. At these meetings, important issues with lifelong implications for parents and their child may be discussed. Such discussions should be planned with care, ensuring that adequate time for in-depth conversation is allotted; a private, physical setting is arranged; and that both parents and/or others who might be identified by the family as primary supports are present. These meetings should first and foremost elicit what parents are thinking or worried about. Included is a review of what was previously discussed, listening to other concerns and issues as they are revealed, having parents repeat back what was said to ensure clarity, and responding with honest, factual answers in areas of uncertainty. By offering medical recommendations based on family goals and the clinical reality, the team can decrease the burden of responsibility for decision-making that parents carry.

Families may look to their pediatrician for assurance that all treatment options have been explored. Assisting a patient’s family to arrange a second opinion may be helpful. Listening to families and children speak about the future even in the face of poor prognosis may help keep the focus on living even while the child may be dying. Hoping for a miracle can coexist for parents even as they are facing and accepting the more likely reality of death.

Parents also need to know about the availability of home care, respite services, web-based support and information, educational books and videotapes, and support groups. Responding to parent requests or need for counseling referrals for themselves, other children, or family is essential.

While broaching the topic may seem daunting, exploration of how parents envision their child’s death, addressing their previous loss experiences (most often with death of an adult relative) and any misconceptions they may have, is often a great relief to parents. Learning about cultural, spiritual, and family values regarding pain management, suffering, and the preferred place of end-of-life care is essential before death. Even raising the thoughts about funeral arrangements, the possibility of autopsy, and tissue donation can be helpful to give parents choices and know that these things can be discussed without fear. A major worry of many parents is in how to involve and communicate with siblings as well as the child about the fact that most likely death is going to occur.

Ratings of high satisfaction with physician care have been directly correlated with receiving clear communication around end-of-life issues, delivered with sensitivity and caring; such communication included speaking directly to the child when appropriate. Communication is complicated by an assumed need for mutual protection in which the child wants to protect his or her parents and likewise the parents want to protect their child from painful information or sadness. Honoring the family’s communication style, values, spirituality, and culture, which may be impacted by the child’s personality style, is critical in these highly sensitive conversations. Evidence shows that parents who have open conversations with their child about death and dying do not regret having done so.

In communications with the child and family, the physician should avoid giving estimates of survival length, even when the child or family explicitly asks for them. These predictions are invariably inaccurate because population-based statistics do not predict the course for individual patients. A more honest approach may be to explore ranges of time in general terms (“weeks to months,” “months to years”). The physician can also ask parents what they might do differently if they knew how long their child would live and then assist them in thinking through the options relating to their specific concerns (suggest celebrating upcoming holidays/important events earlier in order to take advantage of times when the child may be feeling better). It is generally wise to suggest that relatives who wish to visit might do so earlier rather than later, given the unpredictability of the time course of many illnesses.

For the child and family, the integration of bad news is a process, not an event, and when done sensitively does not take away hope or alter the relationship between the family and physician. The physician should expect that some issues previously discussed may not be fully resolved for the child and parents (do-not-resuscitate [DNR] orders, artificial nutrition or hydration) and may need to be revisited over time. Parents of a child with chronic illness may reject the reality of an impending death because past predictions may not have been accurate. Whether they are parents of a child with a chronic illness or of a child whose death is the result of accident or sudden catastrophic illness, they may experience great anxiety, guilt, or despair.

The Child

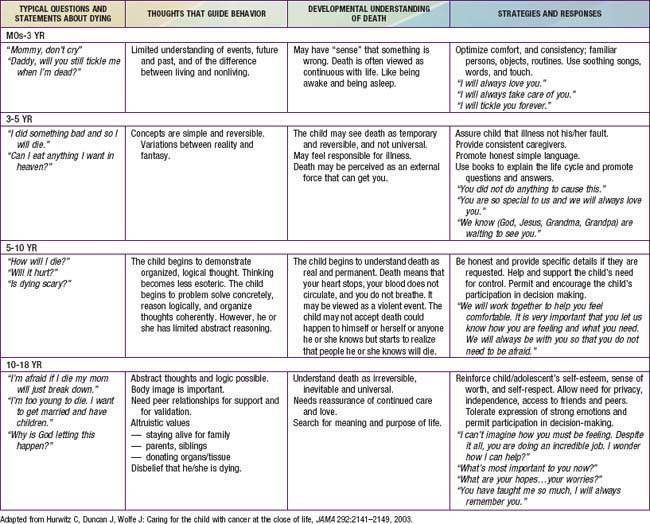

Truthful communication that takes into account the child’s developmental stage and unique lived experience can help to address the fear and anxiety commonly experienced among children with life-threatening illness. Responding in a developmentally appropriate fashion (Table 40-2) to a child’s questions about death, such as “What’s happening to me?” or “Am I dying?” requires a careful exploration of what is already known by the child, what is really being asked (the question behind the question), and why the question is being asked at this particular time and in this setting. It may signal a need to be with someone who is comfortable listening to such unanswerable questions. Many children find nonverbal expression much easier than talking; art, play therapy, and storytelling may be more helpful than direct conversation.

A child’s perception of death depends on his or her conceptual understanding of universality (that all things inevitably die), irreversibility (that dead people cannot come back to life), nonfunctionality (that being dead means that all biologic functions cease), and causality (that there are objective causes of death).

Very young children may struggle with the concepts of irreversibility and nonfunctionality. For young school-aged children, who are beginning to understanding the finality of death, worries may include magical thinking in which their thoughts, wishes, or bad behavior might be the underlying cause for their illness. Older children seek more factual information to gain some control over the situation.

Children’s fears of death are often centered on the concrete fear of being separated from parents and other loved ones and what will happen to their parents rather than themselves. This can be true for teens and young adults as well. This fear may be responded to in different ways: some families may give reassurance that loving relatives will be waiting, while others use religious figures to refer to an eternal spiritual connection.

While adolescents may have a conceptual understanding of death similar to that of adults, working with the adolescent with life-threatening illness presents unique concerns and issues. The developmental work of adolescence includes separating from their parents, developing strong peer relationships, and moving towards independent adulthood. For this particular population, the teenager’s developmental need to separate is complicated by the often increasing dependence both physically and emotionally on their parents. At the same time, adolescents are often asked to be part of the decision-making process without always having the emotional experience to fully understand the impact.

In addition to developmental considerations, understanding related to the child’s life experiences, the length of the child’s illness, the understanding of the nature and prognosis of the illness, the child’s role in the family (peacemaker, clown, troublemaker, the “good” child) should be considered in communication with children.

Parents have an instinctive and strong desire to protect their children from harm. When facing the death of their child, many parents attempt to keep the reality of impending death hidden from their child with the hope that the child can be “protected” from the harsh reality. Although it is important to respect parental wishes, it is also true that most children already have a sense of what is happening to their bodies even when it has been purposely left unspoken. Children may blame themselves for their illness and the hardships that it causes for their loved ones. Perpetuating the myth that “everything is going to be all right” takes away the chance to explore fears and provide reassurance. Honest communication also allows opportunities for memory and legacy making and saying goodbye.

School is the “work” of childhood and is important in optimizing quality of life for a child seeking “normalcy” in the face of illness. Finding ways to help children and their families to maintain these connections through modification of the school day and exploring options to promote educational and social connections into the home or into the hospital room can be meaningful in the event that a child is not well enough to attend school.

As with the younger child, finding ways to help the adolescent maintain peer relationships and school based programming can be important in maximizing quality of life.

The Siblings

Brothers and sisters are at special risk both during their sibling’s illness and after the death. Because of the extraordinary demands placed on parents to meet the needs of their ill child, healthy siblings may feel that their own needs are not being acknowledged or fulfilled. These feelings of neglect may then trigger guilt about their own good health and resentment toward their parents and ill sibling. Younger siblings may react to the stress by becoming seemingly oblivious to the turmoil around them. Some younger siblings may feel guilty as a result of “wishing” the affected child would die so they could get their parents back (“magical thinking”). Parents need to know that these are normal responses, and siblings should be encouraged to maintain the typical routines of daily living. Siblings who are most involved with their sick brothers or sisters before death usually adjust better both at the time of and after the death. Acknowledging and validating sibling feelings, being honest and open, and appropriately involving them in the life of their sick sibling provide a good foundation for the grief process.

The Staff

Inadequate support for the staff providing palliative care can result in depression, emotional withdrawal, and other symptoms. Offering educational opportunities and emotional support for staff at various stages of caring for a child with life-threatening illness can be helpful in bettering patient/family care and preventing staff from experiencing long-term repercussions, including the possibility of leaving the field.

Decision-Making

In the course of a child’s life-limiting illness, a series of difficult decisions need to be made in relation to location of care, medications with risks and benefits, withholding and or withdrawing life-prolonging treatments, experimental treatments in research protocols, and the use of complementary therapies (Chapter 3). Such family decisions are greatly facilitated by opportunities for in-depth and guided discussions around goals of care for their child. This is often accomplished by asking open-ended questions that explore the parent’s and child’s hopes, worries, and family values. Goals of care conversations include what is most important for them as a family, considerations of their child’s clinical condition, and their values and beliefs, including cultural, religious, and spiritual considerations.

Decision-making should be focused on the goals of care, as opposed to limitations of care; “This is what we can offer” instead of “This is what we can no longer do.” Instead of meeting specifically to discuss “withdrawing support” or a DNR order, a more general discussion centered on the goals of care will naturally lead to considering which interventions are in the child’s best interests.

Resuscitation Status

Many parents do not understand the legal mandate requiring attempted resuscitation for cardiorespiratory arrest unless a written DNR order is in place. In broaching this topic, rather than asking parents if they want to forgo cardiopulmonary resuscitation for their child (and placing the full burden of decision-making on them), it is preferable to discuss whether or not resuscitative interventions are likely to benefit the child. It is important to make recommendations based on overall goals of care and medical knowledge of potential benefit and/or harm of these interventions. Once the goals of therapy are agreed upon, the physician is required to write a formal order; it is also extremely beneficial to write a letter delineating decisions regarding resuscitation interventions and supportive care measures to be undertaken for the child. The letter should be as detailed as possible, including recommendations for comfort medications and contact information for caregivers best known to the patient. Such a letter, given to the parents, with copies to involved caregivers and institutions, can be a useful communication aid, especially in times of crisis. Many states have out of hospital DNR verification forms, which if completed on behalf of the child, affirm that rather than initiating resuscitative efforts, emergency response teams are obligated to provide comfort measures when called to the scene.

Conflicts in decision-making can occur within families, within health care teams, between the child and family, and between the family and professional caregivers (Chapter 3). For children who are developmentally unable to provide guidance in decision-making (neonates, very young children, or children with cognitive impairment), parents and health care professionals may come to different conclusions as to what is in the child’s best interests. Decision-making around the care of adolescents presents specific challenges, given the shifting boundary that separates childhood from adulthood. In some families and cultures, truth telling and autonomy are much less valued compared with family integrity (Chapter 4). Although frequently encountered, differences in opinion are often manageable for all involved when lines of communication are kept open, team and family meetings are held, and the goals of care are clear (Chapters 3, 12, and 106).

Symptom Management

Intensive symptom control is another cornerstone of pediatric palliative care. Alleviation of symptoms reduces suffering of the child and family, and allows them to focus on other concerns and participate in meaningful experiences. Despite increasing attention to symptoms, and pharmacologic and technical advances in medicine, children often suffer from multiple symptoms. Key elements and general approaches to managing symptoms are provided in Table 40-3.

Table 40-3 KEY ELEMENTS OF EFFECTIVE SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT

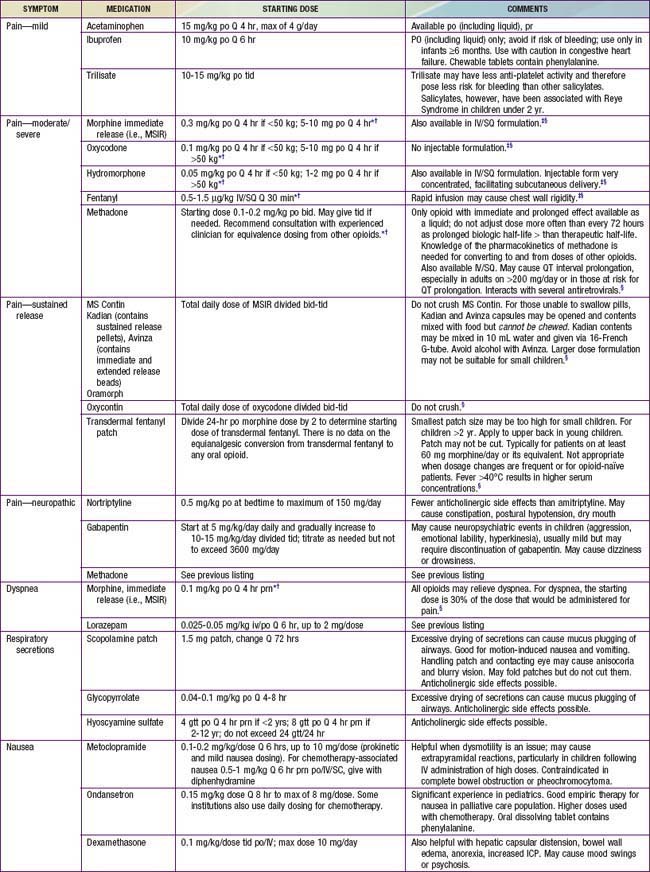

Pain is a complex sensation triggered by actual or potential tissue damage and influenced by cognitive, behavioral, emotional, social, and cultural factors. Effective pain relief is essential to prevent central desensitization, a central hyperexcitation response that may lead to escalating pain, and to diminish a stress response that may have a variety of physiologic effects. Assessment tools include self-report tools for children who are able to communicate their pain verbally, as well as tools based on behavioral cues for children who are unable to do so because of developmental or cognitive limitations. Management of pain is addressed in Tables 40-4 and 40-5 (Chapter 71). Many children with life-threatening illness require opioids for pain at some point in their illness trajectory. Though a stepwise approach to pain is recommended, the step consisting of “weak opioids” is often skipped. The primary opioid in this category, codeine, should generally be avoided because of its side effect profile and lack of superiority over nonopioid analgesics. Furthermore, relatively common genetic polymorphisms in the CYP2D6 gene lead to wide variation in codeine metabolism. Specifically, 10-40% of individuals carry polymorphisms causing them to be “poor metabolizers” who cannot convert codeine to its active form, morphine, and therefore are at risk for inadequate pain control; others are “ultra metabolizers” who may even experience respiratory depression from rapid generation of morphine from codeine. It is therefore preferable to use a known amount of the active agent, morphine.

Table 40-4 GUIDELINES FOR PAIN MANAGEMENT

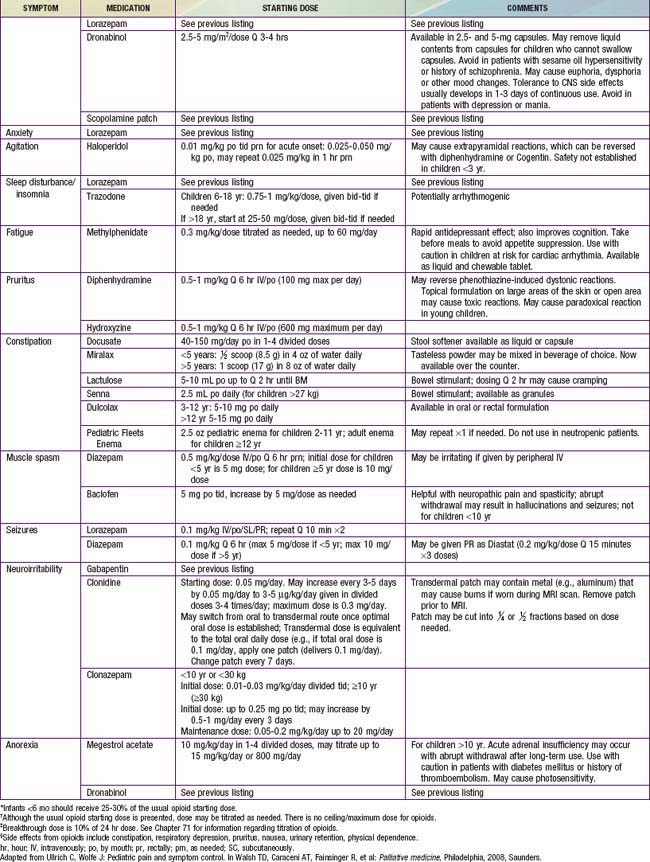

Table 40-5 PHARMACOLOGIC APPROACH TO SYMPTOMS COMMONLY EXPERIENCED BY CHILDREN WITH LIFE-THREATENING ILLNESS

It is important to explore with families, as well as members of the care team, misconceptions that they may have regarding addiction, dependence, the symbolic meaning of starting morphine and/or a morphine drip, and the potential for opioids to hasten death. There is no association between administration or escalation of opioids and length of survival. Evidence supports longer survival in individuals with symptoms that are well controlled.

Children also often experience a multitude of nonpain symptoms. A combination of both pharmacologic (see Table 40-5) and nonpharmacologic approaches (Table 40-6) is often optimal. Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms in children with advanced illness. Children may experience fatigue as a physical symptom (e.g., weakness or somnolence), a decline in cognition (e.g., diminished attention or concentration), and/or impaired emotional function (e.g., depressed mood or decreased motivation). Because of its multidimensional and incapacitating nature, fatigue can prevent children from participating in meaningful or pleasurable activities, thereby impairing quality of life. Fatigue is usually multifactorial in etiology. A careful history may reveal contributing physical factors (uncontrolled symptoms, medication side effects), psychologic factors (anxiety, depression), spiritual distress, or sleep disturbance. Interventions to reduce fatigue include treatment of contributing factors, exercise, pharmacologic agents, and behavior modification strategies. Challenges to effectively addressing fatigue include the common belief that fatigue is inevitable, lack of communication between families and care teams about it, and limited awareness of potential interventions for fatigue.

Table 40-6 NONPHARMACOLOGIC APPROACH TO SYMPTOMS COMMONLY EXPERIENCED BY CHILDREN WITH LIFE-THREATENING ILLNESS

| SYMPTOM | APPROACH TO MANAGEMENT |

|---|---|

| Pain | Prevent pain when possible by limiting unnecessary painful procedures, providing sedation, and giving pre-emptive analgesia prior to a procedure (e.g., including sucrose for procedures in neonates) |

| Address coincident depression, anxiety, sense of fear or lack of control | |

| Consider guided imagery, relaxation, hypnosis, art/pet/play therapy, acupuncture/acupressure, biofeedback, massage, heat/cold, yoga, transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation, distraction | |

| Dyspnea or air hunger | Suction secretions if present, positioning, comfortable loose clothing, fan to provide cool, blowing air |

| Limit volume of IV fluids, consider diuretics if fluid overload/pulmonary edema present | |

| Behavioral strategies including breathing exercises, guided imagery, relaxation, music | |

| Fatigue | Sleep hygiene |

| Gentle exercise | |

| Address potentially contributing factors (e.g., anemia, depression, side effects of medications) | |

| Nausea/vomiting | Consider dietary modifications (bland, soft, adjust timing/volume of foods or feeds) |

| Aromatherapy: peppermint, lavender; acupuncture/acupressure | |

| Constipation | Increase fiber in diet, encourage fluids |

| Oral lesions/dysphagia | Oral hygiene and appropriate liquid, solid and oral medication formulation (texture, taste, fluidity). Treat infections, complications (mucositis, pharyngitis, dental abscess, esophagitis). |

| Orophayngeal motility study and speech (feeding team) consultation. | |

| Anorexia/cachexia | Manage treatable lesions causing oral pain, dysphagia, anorexia. Support caloric intake during phase of illness when anorexia is reversible. Acknowledge that anorexia/cachexia is intrinsic to the dying process and may not be reversible. |

| Prevent/treat coexisting constipation | |

| Pruritus | Moisturize skin |

| Trim child’s nails to prevent excoriation | |

| Try specialized anti-itch lotions | |

| Apply cold packs | |

| Counterstimulation, distraction, relaxation | |

| Diarrhea | Evaluate/treat if obstipation |

| Assess and treat infection | |

| Dietary modification | |

| Depression | Psychotherapy, behavioral techniques |

| Anxiety | Psychotherapy (individual and family), behavioral techniques |

| Agitation/terminal restlessness | Evaluate for organic or drug causes |

| Educate family | |

| Orient and reassure child; provide calm, nonstimulating environment |

From Sourkes B, Frankel L, Brown M, et al: Food, toys, and love: pediatric palliative care, Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 35:345–392, 2005.

Dyspnea (the subjective sensation of shortness of breath) is due to a mismatch between afferent sensory input to the brain and the outgoing motor signal from the brain. It may stem from respiratory causes (e.g., airway secretions, obstruction, infection) or other factors (e.g., cardiac), and may also be influenced by psychologic factors (e.g., anxiety). Respiratory parameters such as respiratory rate and oxygen saturation correlate unreliably with the degree of dyspnea present. Therefore, giving oxygen to a cyanotic or hypoxic child who is otherwise quiet and relaxed may relieve staff discomfort while having no impact on patient distress. Dyspnea can be relieved with the use of regularly scheduled plus as-needed doses of opioids. Opioids work directly on the brainstem to reduce the sensation of respiratory distress, as opposed to relieving dyspnea via sedation. The dose of opioid needed to reduce dyspnea is as little as 25% of the amount that would be given for analgesia. Nonpharmacologic interventions, including guided imagery or hypnosis to reduce anxiety, or cool, flowing air, aimed toward the face, are also frequently helpful in alleviating dyspnea. While oxygen may relieve hypoxemia-related headaches, it is no more effective than blowing room air in reducing the distressing sensation of shortness of breath.

As death approaches, a buildup of secretions may result in noisy respiration sometimes referred to as a “death rattle.” Patients at this stage are usually unconscious, and noisy respirations are often more distressing for others than for the child. It is often helpful to discuss this anticipated phenomenon with families in advance, and if it occurs, to point out the child’s lack of distress from it. If treatment is needed, an anticholinergic medication, such as hyoscine, may reduce secretions.

Neurologic symptoms include seizures that are often part of the antecedent illness but may increase in frequency and severity toward the end of life. A plan for managing seizures should be made in advance and anticonvulsants should be readily available in the event of seizure. Parents can be taught to use rectal diazepam at home. Increased neuroirritability accompanies some neurodegenerative disorders; it may be particularly disruptive because of the resultant break in normal sleep-wake patterns and the difficulty in finding respite facilities for children who have prolonged crying. Such neuroirritability may respond to gabapentin. Judicious use of sedatives, benzodiazepines, clonidine, or methadone may also reduce irritability without inducing excessive sedation; this combination can dramatically improve the quality of life for both child and caregivers. Increased intracranial pressure and spinal cord compression are most often encountered in children with brain tumors or metastatic and solid tumors. Depending on the clinical situation and the goals of care, radiation therapy, surgical interventions, and steroids are potential therapeutic options.

Feeding and hydration issues can raise ethical questions that evoke intense emotions in families and medical caregivers alike. Options that may be considered to artificially support nutrition and hydration in a child who can no longer feed by mouth include nasogastric and gastrostomy feedings or intravenous nutrition or hydration (Chapter 3). These complex decisions require evaluating the risks and benefits of artificial feedings and taking into consideration the child’s functional level and prognosis. At times, it may be appropriate to initiate a trial of tube feedings with the understanding that they may be discontinued at a later stage of the illness. A commonly held but unsubstantiated belief is that artificial nutrition and hydration are “comfort measures,” without which a child may suffer from starvation or thirst. This may result in well-meaning but disruptive and invasive attempts to administer nutrition or fluids to a dying child. In dying adults, the sensation of thirst may be alleviated by careful efforts to keep the mouth moist and clean. There may also be deleterious side effects to artificial hydration in the form of increased secretions, need for frequent urination, and exacerbation of dyspnea. For these reasons, it is important to educate families about anticipated decreases in appetite/thirst and therefore little need for nutrition and hydration as the child approaches death. In addition, exploring the meaning that provision of nutrition and hydration may hold for families, as well alternative ways that they may love and nurture their child, may be a helpful way to approach this issue.

Nausea and vomiting may be due to a variety of causes, including medications/toxins, irritation to or obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract, motion, and emotions. Drugs such as metoclopramide, 5-hydroxytryptamine antagonists, steroids, and aprepitant may be used, and should be chosen depending on the underlying pathophysiology and neurotransmitters involved. Vomiting may accompany nausea but may also occur without nausea, such as in the instance of increased intracranial pressure. Constipation is commonly encountered in children with neurologic impairment or children receiving medications that impair gastrointestinal motility (most notably, opioids). Stool frequency and quantity should be evaluated in the context of the child’s diet and usual bowel pattern. Children on regular opioids should routinely be placed on stool softeners (docusate) in addition to a laxative agent (e.g., senna). Diarrhea may be particularly difficult for the child and family and may be treated with loperamide and opioids. Paradoxical diarrhea, a result of overflow resulting from constipation, must also be considered.

Hematologic issues include consideration of anemia and thrombocytopenia or bleeding. If the child has symptomatic anemia (weakness, dizziness, shortness of breath, tachycardia), red blood cell transfusions may be considered. Platelet transfusions may be an option if the child has symptoms of bleeding. Life-ending hemorrhage is disturbing for all concerned, and a plan involving the use of fast-acting sedatives should be prepared in advance if such an event is a possibility.

Skin care issues include primary prevention of problems by frequent turning and repositioning and alleviating pressure wherever possible (e.g., elevating heels with pillows). Pruritus may be secondary to systemic disorders or drug therapy. Treatment includes avoiding excessive use of drying soaps, using moisturizers, trimming fingernails, and wearing loose-fitting clothing, in addition to administering topical or systemic steroids. Oral antihistamines and other specific therapies may also be indicated (e.g., cholestyramine in biliary disease). While opioids can cause histamine release from mast cells, this does not account for most of the pruritus caused by opioids. A trial of diphenhydramine may provide relief; alternatively, switching opioids or instituting a low dose of opioid antagonist may be needed for refractory pruritus.

Children with life-threatening illness may experience psychologic symptoms such as anxiety and depression. Such symptoms are frequently multifactorial, and sometimes interrelated with uncontrolled symptoms such as pain and fatigue. Diagnosing depression in the context of serious illness may pose challenges since neurovegetative symptoms may not be reliable indicators. Instead, expressions of hopelessness, helplessness, worthlessness, and guilt may be more useful. While psychopharmacologic agents may improve psychologic symptoms, psychologic interventions and opportunities for children to explore worries, hopes, and concerns in an open, supportive, and nonjudgmental setting are equally if not more important. Skilled members from a variety of disciplines, including psychology, social work, chaplaincy, child life, expressive therapy, among others, may help children and their families in this regard. Such opportunities may in fact create positive moments in which meaning, connection, and new definitions of hope are found.

When discussing possible therapies or interventions with adolescent patients or with the parents of any ill child, it is important to raise the issue of complementary or alternative medicine. Many families use some form of alternative medicine therapy but do not bring it up with their physician unless explicitly asked (Chapter 59). Although largely unproven, some therapies are inexpensive and provide relief to individual patients. Other therapies may be expensive, painful, intrusive, and even toxic. By initiating conversation and inviting discussion in a nonjudgmental way, the physician can offer advice on the safety of different therapies and may help avoid expensive, dangerous, or burdensome interventions.

Intensive Symptom Management

When intensive efforts to relieve the symptom have been exhausted, or when efforts to address suffering are incapable of providing relief with acceptable toxicity/morbidity or in an acceptable time frame, palliative sedation may be considered. Palliative sedation may relieve suffering from refractory symptoms by reducing a child’s level of consciousness. It is most often used for intractable pain, dyspnea, or agitation, but is not limited to these distressing indications.

The principle of double effect is often invoked to justify escalation of symptom-relieving medications or palliative sedation for uncontrolled symptoms at the end of life. Use of this principle emphasizes the risk of hastening death posed by escalating opioids or sedation, which is theoretical and unproven. There is mounting evidence that patients with well-controlled symptoms live longer.

The Terminal Phase

As death seems imminent, the major task of the physician and team are to help the child have as many good days as possible and not suffer. Gently preparing the family for what to expect and offering choices, when possible, will allow them a sense of control in the midst of tragic circumstances. Before death, it can be very helpful to discuss:

Families will inform the provider of what they can tolerate thinking about. It may help to let the family know this is not about whether the child will die but how the child may die.

Families gain tremendous support from having a physician who will continue to stay involved in the child’s care. If the child is at home or hospitalized, regular phone calls or visits, assisting with symptom management, and offering emotional support is invaluable for families.

In an intensive care setting, where technology can be overwhelming and put distance between the child and parent, the physician can offer discontinuation of that which is not benefiting the child or adding to quality of life. Parents may be afraid to ask about holding or sleeping next to their child. They may need reassurance and assistance in holding, touching, and speaking with their child, despite tubes and technology, even if the child appears unresponsive.

It is believed that hearing and the ability to sense touch is often present until death; all family members should be encouraged to continue interacting with their loved one through the dying process. Parents may be afraid to leave the bedside so that their child will not die alone. In most instances the moment of death cannot be predicted. Some propose that children wait to die until parents are “ready,” an important event has passed, or until they are given permission. Caregivers need not dispute this, nor the hope for a miracle often held by families until the child takes the very last breath.

For the family, the moment of death is an event that is recalled in detail for years to come, and so enhancing opportunity for dignity and limited suffering is essential. Families may find solace in having a clinician present. After death, they should be given the option of remaining with their child for as long as they would like. During this time, physicians and other professionals may ask permission to “say goodbye.” The family may be invited to bathe and dress the body as a final act of caring for the child.

The physician’s decision to attend the funeral is a personal one. Participation may serve the dual purpose of showing respect as well as helping the clinician cope with a personal sense of loss. If unable to attend services, families report highly valuing the importance of receiving a card or note from the physician. To know that their child made a difference and will not be forgotten is incredibly important to families in their bereavement.

The Pediatrician

While optimal palliative care for children entails caregivers from a variety of disciplines, pediatricians are well-positioned to support children and their families, particularly if they have a long-standing relationship with multiple family members. A pediatrician who has cared for a family over time may already know and care for other family members, understand pre-existing stressors for the family, and may be familiar with coping strategies used by family members. Pediatricians are familiar with the process of eliciting concerns and providing anticipatory guidance for parents, as well as developmentally appropriate explanations for children.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Palliative care for children. Pediatrics. 2000;106:351-357.

Berde CB, Sethna NF. Analgesics for the treatment of pain in children. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1094-1103.

Contro NA, Larson J, Scofield S, et al. Hospital staff and family: perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1248-1252.

Field MJ, Behrman RE, editors. When children die: improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003.

Kolarik RC, Walker G, Arnold RM. Pediatric resident education in palliative care: a needs assessment. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1949-1954.

Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdóttir U, Onelöv E, et al. Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1175-1186.

Liben S, Papadatou D, Wolfe J. Paediatric palliative care: challenges and emerging ideas. Lancet. 2008;371:852-864.

Smith AK, Sundore RL, Pérez-Stable EJ. Palliative care for Latino patients and their families. JAMA. 2009;301:1047-1057.

Sourkes B, Frankel L, Brown M, et al. Food, toys, and love: pediatric palliative care. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2005;35:345-392.

Stroebe M, Schut H, Strobe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. 2007;370:1960-1972.

Wolfe J, Hammel JF, Edwards KE, et al. Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: is care changing? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1717-1723.