Chapter 104 Adolescent Development

See also Part XII and Chapters 555 and 556.

104.1 Adolescent Physical and Social Development

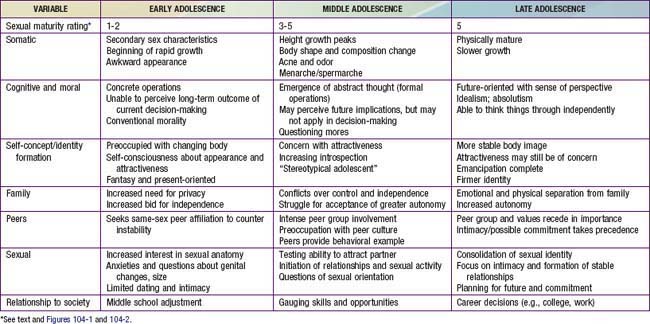

Young people undergo rapid changes in body structure and physiologic, psychological, and social functioning between the ages of approximately 9 to 10 and 20 yr. Adolescence consists of 3 distinct periods—early, middle, and late—each marked by a characteristic set of biologic, psychological, and social issues (Table 104-1). Hormones set this developmental agenda together with social structures designed to foster the transition from childhood to adulthood. Although individual variation is substantial, in both the timing of somatic changes and the quality of the experience, pubertal changes follow a predictable sequence. Gender and subculture profoundly affect the developmental course, as do physical and social stressors.

Early Adolescence

Biologic Development

Adolescence is defined as a period of development; puberty is the biologic process in which a child becomes an adult. These changes include appearance of the secondary sexual characteristics, increase to adult size, and development of reproductive capacity. Adrenal production of androgen (chiefly dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate [DHEAS]) may occur as early as 6 yr of age, with development of underarm odor and faint genital hair (adrenarche). Levels of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) rise progressively throughout middle childhood without dramatic effect. Rapid pubertal changes begin with increased sensitivity of the pituitary to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH); pulsatile release of GnRH, LH, and FSH during sleep; and corresponding increases in gonadal androgens and estrogens. The triggers for these changes are incompletely understood, but may involve ongoing neuronal development throughout middle childhood and adolescence.

Data regarding the timing for the onset of puberty in girls are controversial (Table 104-2). Several studies from 1948 to 1981 identified the average age for the onset of breast development to range from 10.6-11.2 yr of age. Multiple reports since 1997 suggest a significantly earlier onset of breast development, ranging from 8.9-9.5 yr in African-American girls and 10.0-10.4 yr in white girls. There also appears to be a small secular trend toward decreasing ages for the onset of pubic hair development and menarche. The reasons for the larger decrease in age for breast development may include the epidemic of childhood obesity as well as exposure to estrogen-like toxins in the environment that include certain pesticides, plastics, phytoestrogens, and industrial compounds along with beef fattened with subcutaneous estrogen pellets.

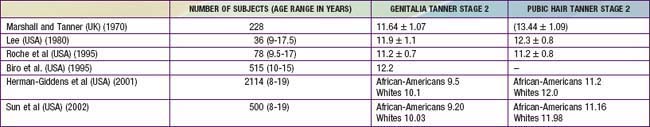

It is less clear whether there is also a secular trend for decreasing age for onset of puberty in boys (Table 104-3). It appears that, over the past 40 yr, the average age for the onset of genital and pubic hair development may have decreased by about a year. The onset of puberty in African-American boys precedes that in white boys by at least 6 mo.

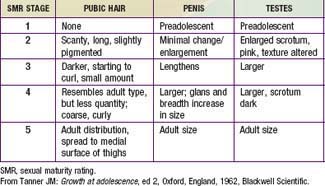

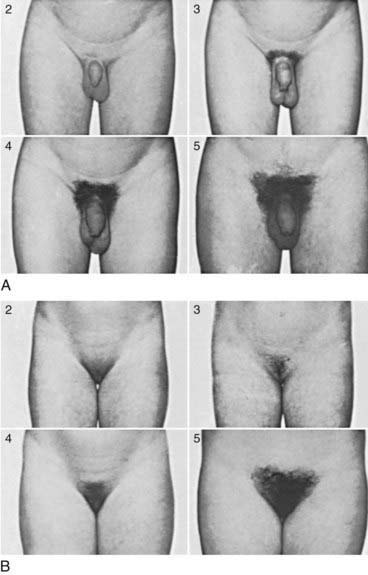

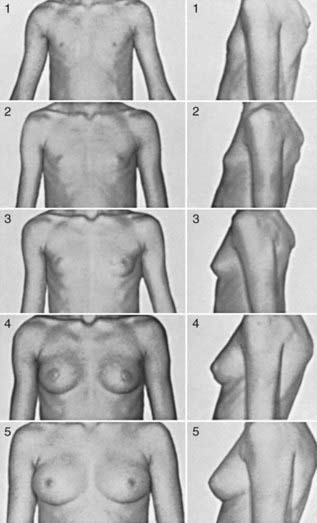

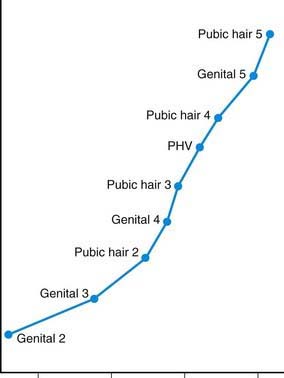

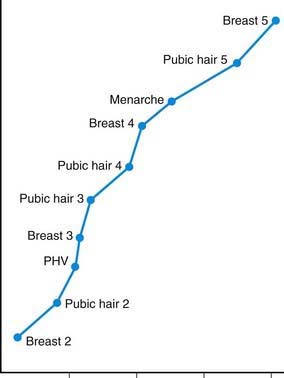

Once the onset of puberty has begun, the resulting sequence of somatic and physiologic changes gives rise to the sexual maturity rating (SMR), or Tanner stages. Figures 104-1 and 104-2 depict the somatic changes used in the SMR scale; Tables 104-4 and 104-5 also describe these changes. Figures 104-3 and 104-4 depict the typical sequence of pubertal changes in boys and girls, respectively. The range of normal progress through sexual maturation is wide.

Figure 104-1 Sexual maturity ratings (2 to 5) of pubic hair changes in adolescent boys (A) and girls (B) (see Tables 104-4 and 104-5).

(Courtesy of J.M. Tanner, MD, Institute of Child Health, Department for Growth and Development, University of London, London, England.)

Figure 104-2 Sexual maturity ratings (1 to 5) of breast changes in adolescent girls.

(Courtesy of J.M. Tanner, MD, Institute of Child Health, Department for Growth and Development, University of London, London, England.)

Table 104-4 CLASSIFICATION OF SEXUAL MATURITY STATES IN GIRLS

| SMR STAGE | PUBIC HAIR | BREASTS |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Preadolescent | Preadolescent |

| 2 | Sparse, lightly pigmented, straight, medial border of labia | Breast and papilla elevated as small mound; diameter of areola increased |

| 3 | Darker, beginning to curl, increased amount | Breast and areola enlarged, no contour separation |

| 4 | Coarse, curly, abundant, but less than in adult | Areola and papilla form secondary mound |

| 5 | Adult feminine triangle, spread to medial surface of thighs | Mature, nipple projects, areola part of general breast contour |

SMR, sexual maturity rating.

From Tanner JM: Growth at adolescence, ed 2, Oxford, England, 1962, Blackwell Scientific.

Figure 104-3 Sequence of pubertal events in males. PHV, peak height velocity.

(From Root AW: Endocrinology of puberty, J Pediatr 83:1, 1973.)

Figure 104-4 Sequence of pubertal events in females. PHV, peak height velocity.

(From Root AW: Endocrinology of puberty, J Pediatr 83:1, 1973.)

In girls, the 1st visible sign of puberty and the hallmark of SMR2 is the appearance of breast buds, between 8 and 12 yr of age. Menses typically begins 2- yr later, during SMR3-4 (median age, 12 yr; normal range, 9-16 yr) (see Fig. 104-4). Less obvious changes include enlargement of the ovaries, uterus, labia, and clitoris, and thickening of the endometrium and vaginal mucosa.

yr later, during SMR3-4 (median age, 12 yr; normal range, 9-16 yr) (see Fig. 104-4). Less obvious changes include enlargement of the ovaries, uterus, labia, and clitoris, and thickening of the endometrium and vaginal mucosa.

In boys, the 1st visible sign of puberty and the hallmark of SMR2 is testicular enlargement, beginning as early as  yr. This is followed by penile growth during SMR3. Peak growth occurs when testis volumes reach approximately 9-10 cm3 during SMR4. Under the influence of LH and testosterone, the seminiferous tubules, epididymis, seminal vesicles, and prostate enlarge. The left testis normally is lower than the right. Some degree of breast hypertrophy, typically bilateral, occurs in 40-65% of boys during SMR2-3 due to a relative excess of estrogenic stimulation.

yr. This is followed by penile growth during SMR3. Peak growth occurs when testis volumes reach approximately 9-10 cm3 during SMR4. Under the influence of LH and testosterone, the seminiferous tubules, epididymis, seminal vesicles, and prostate enlarge. The left testis normally is lower than the right. Some degree of breast hypertrophy, typically bilateral, occurs in 40-65% of boys during SMR2-3 due to a relative excess of estrogenic stimulation.

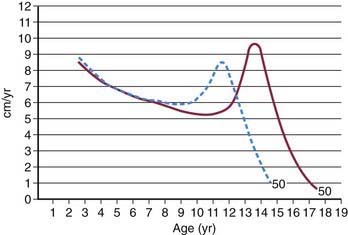

Growth acceleration begins in early adolescence for both sexes, but peak growth velocities are not reached until SMR3-4. Boys typically peak 2-3 yr later than girls, begin this growth at a later SMR stage (Fig. 104-5), and continue their linear growth for approximately 2-3 yr after girls have stopped. The asymmetric growth spurt begins distally, with enlargement of the hands and feet, followed by the arms and legs, and finally, the trunk and chest, giving young adolescents a gawky appearance. Rapid enlargement of the larynx, pharynx, and lungs leads to changes in vocal quality, typically preceded by vocal instability (voice cracking). Elongation of the optic globe often results in nearsightedness. Dental changes include jaw growth, loss of the final deciduous teeth, and eruption of the permanent cuspids, premolars, and finally, molars (Chapter 299). Orthodontic appliances may be needed, secondary to growth exacerbations of bite disturbances.

Figure 104-5 Height velocity curves for American boys (solid line) and girls (dashed line) who have their peak height velocity at the average age (i.e., average growth tempo).

(From Tanner JM, Davies PSW: Clinical longitudinal standards for height and height velocity for North American children, J Pediatr 107:317, 1985.)

Cognitive and Moral Development (See Also Chapter 6)

While adolescence has traditionally been described as the time of transition from concrete operational thinking to formal logical thinking (abstract thought), other processes include the important but distinct contributions of reasoning (cognitive abilities) and judgment (the process of thinking through the consequences of alternative decisions or actions). Because these processes may develop at very different rates, young adolescents may be able to apply formal logical thinking to schoolwork, but not to personal dilemmas. When emotional stakes are high, adolescents may regress to more concrete operational and/or magical thinking. This can interfere with higher-order cognition and ultimately affect the ability to perceive long-term outcomes of current decision-making. The development of moral thinking roughly but imperfectly parallels cognitive development. Whereas younger children view relationships with adults in terms of power and fear of punishment, preadolescents begin to perceive right and wrong as absolute and unquestionable. During mid-adolescence most adolescents become more multidimensional in their thinking and are better able to contemplate hypothetical situations and the relationship between varied actions or decisions and differing outcomes. Despite their increasing abilities for complex decision-making, adolescent decision-making remains particularly susceptible to emotions.

Neuroimaging has enabled greater insight into changes in developing brains that help explain variations in decision-making capacities. Some theorists argue that the transition from concrete to formal operations follows from quantitative increases in knowledge, experience, and cognitive efficiency rather than from a qualitative reorganization of thinking. Consistent with this view is a steady rise in cognitive processing speed from late childhood through early adulthood, associated with a reduction in synaptic number (pruning of less-used pathways) and continued myelination of neurons. Adolescents also experience the development of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the superior temporal gyrus, areas responsible for higher-order associations, including the ability to inhibit impulses, weigh the consequences of decisions, prioritize, and strategize. It is unclear whether the hormonal changes of puberty directly affect cognitive development. Related to neurobehavioral maturation, adolescents may experience an increased intensity of emotion and/or greater inclination to seek experiences that create such high-intensity emotions. Cognitive development also differs by gender, with girls developing at earlier ages than boys.

Self-Concept

Self-consciousness increases exponentially in response to the somatic transformations of puberty. Self-awareness at this age centers on external characteristics, in contrast to the introspection of later adolescence. It is normal for early adolescents to be preoccupied with their body changes, scrutinize their appearance, and feel that everyone else is staring at them (Elkind’s imaginary audience).

The media, with its overrepresentation of sex, violence, and substance use, has a profound influence on cultural norms and an adolescents’ sense of identity. Adolescents use, on average, 7 hr of media per day (e.g., television, Internet). Over half of all high school students have a television in their bedrooms, 70% live in homes with a personal computer, and the proportion with Internet access is approximately 75%. The advent (and ubiquity) of cell phones with texting capability and social networking sites have greatly enhanced communication among adolescents of all ages.

This exposure may cause girls to develop a distorted sense of femininity, and they may be at risk for viewing themselves as overweight, leading to eating disorders and depression (Chapter 26). Similarly, boys may have difficulties with self-image. Images of masculinity may be confusing, leading to self-doubt, insecurity, and misleading conceptions about male behavior. Adolescents who develop earlier than their peers, especially girls, may have higher rates of school difficulty, body dissatisfaction, and depression. These adolescents look like adults and may have adult expectations placed on them, but are not cognitively or psychologically mature.

Relationships with Family, Peers, and Society

In early adolescence, young teens become less interested in parental activities and more interested in the peer group, typically with peers of the same sex. Early adolescents often disregard parents’ advice about safety, appearance, etiquette, and overall comportment and display markedly different values, tastes, and interests. Superficial differences may spark conflicts that are truly about power or difficulty accepting separation. Other core individual characteristics, like sexual identity, might become a source of conflict with potentially damaging and long-lasting consequences for the entire family. Adolescents also seek more privacy, which may contribute to family discord.

The trend toward separation from family often involves selecting adults outside of the family as role models and developing close relationships with particular teachers or the parents of other children. Organizations such as scouting or sports teams can also provide an important sense of extrafamilial belonging.

Early adolescents often socialize in same-sex peer groups. Deepening relationships with peers contributes importantly to their gradual individuation and independence from families of origin. Indicative of increasing sexual awareness, teasing directed against the other gender, homophobic comments and acts, and sexually-related gossip are common, albeit inappropriate, means to cope with personal insecurities and seek social approval. Belonging is all important. In one-to-one friendships, boys and girls differ in important ways. Female friendships may center on emotional intimacy, whereas male relationships may focus more on activities.

An early adolescent’s relationship to society centers on school. The shift from elementary school to middle school or junior high school entails giving up the protection of a single classroom in exchange for the additional stimulation and responsibility involved in moving from class to class. This change in school structure mirrors and reinforces the changes involved in separating from the family.

Sexuality

Anxiety and interest in sex and sexual anatomy increase during early puberty. It is normal for young adolescents to compare themselves with others. In boys, ejaculation occurs for the 1st time, usually during masturbation and later as nocturnal emissions, and may be a cause of anxiety. Early adolescents sometimes masturbate together; isolated incidents of mutual sexual exploration are not necessarily a sign of homosexuality. The prevalence of other forms of sexual behavior, other than masturbation, varies by culture but generally are less common in early adolescents.

Implications for Pediatricians and Parents

Parents may have concerns that they are hesitant to discuss. Parents can be interviewed separately from the adolescent to avoid undermining the adolescent’s trust. When interviewing and examining an adolescent, health care providers should keep in mind that physical maturation correlates with sexual maturity, whereas psychosocial development correlates more closely with chronological age. Early adolescents typically need reassurance that the somatic changes they are experiencing are common and normal.

The pediatrician needs to help parents differentiate between the normal discomforts of the age and truly concerning behaviors. Bids for autonomy, such as avoiding family activities, demanding privacy, and increasing argumentativeness, are normal; extreme withdrawal or antagonism may be dysfunctional. Bewilderment and dysphoria at the start of junior high school are normal; continued failure to adapt several weeks to months later suggests a more serious problem. Risk-taking is limited in early adolescence; escalation of risk-taking behaviors is problematic. Parents must adapt discipline measures to the changing abilities of the adolescent, who can think through problems, assess consequences, and problem solve. Thus, the development of negotiation strategies is critical. Children and adolescents raised by parents who use negotiating as part of child rearing have more positive outcomes than those raised by parents who use more authoritarian or permissive styles.

Middle Adolescence

Biologic Development

Growth accelerates above the prepubertal rate of 6-7 cm (3 in) per year during middle adolescence. In the average girl, the growth spurt peaks at 11.5 yr at a top velocity of 8.3 cm (3.8 in) per year and then slows to a stop at 16 yr (see Fig. 104-5). In the average boy, the growth spurt starts later, peaks at 13.5 yr at 9.5 cm (4.3 in) per year, and then slows to a stop at 18 yr. Weight gain parallels linear growth, with a delay of several months, so that adolescents seem first to stretch and then to fill out. Muscle mass also increases, followed approximately 6 mo later by an increase in strength; boys show greater gains in both. Lean body mass, approximately 80% in the average prepubertal child, increases to 90% in boys and decreases to 75% in girls as subcutaneous fat accumulates.

Boys with SMR3 pubic hair and SMR4 genitals normally have their peak growth spurts ahead of them; girls at the same SMR are usually past their peaks (see Figs. 104-3 and 104-4). Widening of the shoulders in boys and the hips in girls is also hormonally determined. Other changes include a doubling in heart size and lung vital capacity. Blood pressure, blood volume, and hematocrit rise, particularly in boys. Androgenic stimulation of sebaceous and apocrine glands results in acne and body odor. Physiologic changes in sleep patterns and requirements may be mistaken for laziness; adolescents have difficulty falling asleep and waking up, especially for early school start times as opposed to typical self-regulated or preferred sleep schedules.

Menarche is achieved by 30% of girls by SMR3 and by 90% by SMR4 (95% of girls reach menarche at 10.5-14.5 yr of age). Menarche usually follows approximately 1 yr after the growth spurt begins. It is very common for cycles to be anovulatory during the 1st 2 yr after menarche (approximately 50%). The timing of menarche, which is not completely understood, appears to be determined by genetics as well as by factors such as adiposity, chronic illness, nutritional status, type and amount of exercise, and emotional well-being. Before menarche, the uterus achieves a mature configuration, vaginal lubrication increases, and a clear vaginal discharge appears (physiologic leukorrhea). In boys, the phallus lengthens and widens during SMR3, and sperm are usually apparent in semen.

Cognitive and Moral Development

With the transition to formal logical thinking, middle adolescents start to question and analyze extensively. Young people now have the cognitive ability to understand the intricacy of the world they live in, self-reflect, see beyond themselves, and to begin to understand their own actions in a moral and legal context. Questioning of moral conventions fosters the development of personal codes of ethics, which may be similar to or different from those of their parents. An adolescent’s new flexibility of thought can have pervasive effects on relationships with the self and others.

Self-Concept

Middle adolescents are more accepting of their own body changes and become preoccupied with idealism in exploring future options. Affiliation with a peer group is an important step in confirming one’s identity and self-image. It is normal for middle adolescents to experiment with different personas, changing styles of dress, groups of friends, and interests from month to month. Many philosophize about the meaning of life and wonder, “Who am I?” and “Why am I here?” Intense feelings of inner turmoil and misery are common. Girls may tend to characterize themselves and their peers according to interpersonal relationships (“I am a girl with close friends”), whereas boys may focus on abilities (“I am good at sports”). Adolescents of both genders, but especially boys, who develop later than their peers may experience poorer self-image and have higher rates of difficulty in school.

Relationships with Family, Peers, and Society

Middle adolescence refers to “stereotypical adolescence.” Relationships with parents become more strained and distant due to redirected energies toward peer relationships and separation from the family. Dating can become a lightning rod for parent-child battles, in which the real issue may be the separation from parents rather than the particulars of “with whom” or “how late.” The majority of teenagers progress through adolescence with minimal difficulties rather than experiencing the stereotypical “storm and stress.” It is the minority of adolescents (approximately 20-30%) who do experience stress and struggle through this period who require support. Adolescents with visible differences are also at risk for problems, such as not developing adequate social skills and confidence and having more difficulty establishing satisfying relationships.

As part of middle adolescents’ exploration of future options, they begin to think seriously about what they want to do as adults, a question that formerly had been comfortably hypothetical. The process involves self-assessment and exploration of available opportunities. The presence or absence of realistic role models, as opposed to the idealized ones of earlier periods, can be crucial.

Sexuality

Dating becomes a normative activity as middle adolescents assess their ability to attract others. The degree of sexual activity and its onset vary widely by race, ethnicity, and nation. In the USA, by age 17 yr about 30% of Asians (females 28%, males 33%), about 50% of whites (58% females, 53% males) and Hispanic females (59%), and about 75% of African-Americans (74% females, 82% males) and Hispanic males (69%) have initiated sex. Among youth in rural Africa the median age of sexual debut was 18.5 yr for women and 19.2 yr for men; age at 1st sexual intercourse among Rwandan youth is 20 yr for both males and females. Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender youth often acknowledge their attractions and sexual identity during this period.

In addition to sexual orientation, middle adolescents begin to sort out other important aspects of sexual identity, including beliefs about love, honesty, and propriety. Relationships at this age are often superficial and emphasize attractiveness and sexual experimentation rather than intimacy. Adolescents tend to follow several characteristic patterns of sexual behavior: abstinence, serial monogamy, or polyamory. Most have some knowledge of the risks of pregnancy, HIV, and other sexually transmitted infections, but knowledge does not consistently control behavior. Many sexually active adolescents use condoms consistently with or without other contraceptives; up to 70% of adolescents used some form of contraception or prophylaxis for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) at their 1st intercourse.

Implications for Pediatricians and Parents

Middle adolescence is a time when the opportunity to talk confidentially with a nonjudgmental, informed adult can be particularly appreciated and helpful in the midst of significant psychologic and biologic change.

Adolescents vary greatly in their rate of physical and social progress and in the resolution of central conflicts about autonomy and self-esteem. Questions about family and peer relationships can help locate a child along the developmental continuum and facilitate individualized counseling. Early- and late-maturing adolescents are at risk for psychologic problems. Anticipatory guidance with parents or guardians and appropriate referral to mental health professionals of these adolescents may be warranted.

In asking about dating and sex, do not assume heterosexuality; this approach is sure to preempt further discussion of sexual identity and any associated questions or concerns. Intention to have sex and whether close friends are sexually active are good indications that a youth may be initiating sexual activity shortly. Parental connectedness and close supervision or monitoring of the youth’s activities and peer group can be protective against early onset of sexual activity and involvement in other risk-taking behaviors, and can foster positive youth development. Parents should also assume an active role in their adolescent’s transition to adulthood to ensure that their child receives appropriate preventive health services.

Late Adolescence

Biologic Development

The somatic changes in this period are modest by comparison to earlier periods. The final stages of breast, penile, and pubic hair development occur by 17-18 yr of age in 95% of males and females. Minor changes in hair distribution often continue for several years in males, including the growth of facial and chest hair and the onset of male pattern baldness in a few. Acne occurs in the majority of adolescents, particularly males.

Psychosocial Development

Slowing physical changes permit the emergence of a more stable body image. Cognition tends to be less self-centered, with increasing thoughts about concepts such as justice, patriotism, and history. Older adolescents are more future-oriented and able to act on long-term plans, delay gratification, compromise, set limits, and think independently. Older adolescents are often idealistic but may also be absolutist and intolerant of opposing views. Religious or political groups that promise answers to complex questions may hold great appeal. With impending emancipation, older adolescents begin the transition to adult roles in work and their relationships.

They also have more constancy in their emotions. The peer group and peer values recede in importance. Individual, particularly intimate relationships take precedence, providing an important component of identity for many older adolescents. In contrast to the often superficial dating relationships of middle adolescence, these relationships increasingly involve love and commitment. Career decisions become pressing because an adolescent’s self-concept is increasingly bound up in his or her emerging role in society.

Implications for Pediatricians and Parents

Erikson identified the crucial task of adolescence as the establishment of a stable sense of identity, including emotional and physical separation from the family of origin, initiation of intimacy, and realistic planning for economic independence. The relationship changes from one of parent-child to an adult-adult model. In lieu of equal treatment under the law, adolescents who do not identify as heterosexual face structural barriers in transition to adulthood, such as formal exclusion or discrimination in the military service and in many workplaces and faith-based organizations, legislation prohibiting marriage of same-sex partners, and ineligibility for associated legal and financial benefits in health care and insurance, workers’ compensation, family medical leave, foster- and adoptive-parenting, and consumer benefits for heterosexual families. When no such barriers exist, lack of progress toward adult autonomy may indicate a need for professional counseling. Adolescents who become parents may have the added difficulty of achieving appropriate developmental milestones prior to assuming adult responsibilities.

Afifi TD, Joseph A, Aldeis D. Why can’t we just talk about it? J Adolesc Res. 2008;23:689-721.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care. The initial reproductive health visit. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):240-243.

Campbell IG, Feinberg I. Longitudinal trajectories of non-rapid eye movement delta and theta EEG as indicators of adolescent brain maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5177-5180.

Carey WL, Coleman WL, Elias ER, et al, editors. Developmental-behavioral pediatrics, ed 4, Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier, 2009.

Carswell JM, Stafford DEJ. Normal physical growth and development. In: Neinstein LS, Gordon CM, Katzman DK, et al, editors. Adolescent health care: a practical guide. ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:3-26.

Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, et al. Age of sexual debut among U.S. adolescents. Contraception. 2009;80:158-162.

Euling SY, Herman-Giddens ME, Lee PA, et al. Examination of U.S. puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findings. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl 3):S172-S191.

Kambam P, Thompson C. The development of decision-making capacities in children and adolescents: psychological and neurological perspectives and their implications for juvenile defendants. Behav Sci Law. 2009;27:173-190.

Manlove J, Ikramullah E, Mincieli L, et al. Trends in sexual experience, contraceptive use, and teenage childbearing: 1992–2002. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:413-423.

McGrath N, Nyirenda M, Hosegood V, et al. Age at first sex in rural South Africa. Sex Trans Infect. 2009;85(Suppl 1):i49-i55.

Radzik M, Sherer S, Neinstein LS. Psychosocial development in normal adolescents. In: Neinstein LS, Gordon CM, Katzman DK, et al, editors. Adolescent health care: a practical guide. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:27-31.

Slyper AH. The pubertal timing controversy in the USA and a review of possible causative factors for the advance in the timing of onset of puberty. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2006;65:1-8.

Steinberg L, Monahan K. Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Dev Psychol. 2007;43:1531-1543.

104.2 Sexual Identity Development

Terms and Definitions

Sex and Sexual Identity

Sex is multifaceted and has at least 9 components: chromosomal sex, gonadal sex, fetal hormonal sex (prenatal hormones produced by the gonads), internal morphologic sex (internal genitalia), external morphologic sex (external genitalia), hypothalamic sex (sex of the brain), sex of assignment and rearing, pubertal hormonal sex, and gender identity and role. Sexual identity is a self-perceived identification distilled from any or all aspects of sexuality, and has at least 4 components: sex assigned at birth, gender identity, social sex role, and sexual orientation.

Sex Assigned at Birth

A newborn is assigned a sex before (ultrasound) or at the time of birth based on the external genitalia. In case of a disorder of sex development, these genitalia may appear ambiguous, and additional components of sex (e.g., chromosomal, gonadal, hormonal sex) are assessed. In consultation with specialists, parents assign the child a sex that they believe is most likely to be consistent with gender identity, which cannot be assessed until later in life (Chapter 582).

Gender Identity, Gender Role, and Social Sex Role

Gender identity refers to a person’s basic sense of being a boy/man, girl/woman, or other gender (e.g., transgender). Gender role refers to one’s role in society, typically either the male or female role. Gender identity needs to be distinguished from social sex role (also referred to as gender role behavior), which refers to characteristics in personality, appearance, and behavior that are, in a given culture and time, considered masculine or feminine. Gender role is about one’s presentation as a boy/man or girl/woman, whereas social sex role is about the masculine and/or feminine characteristics one exhibits in a given gender role. Both boys/men, girls/women, and transgender persons can be masculine and/or feminine to varying degrees; gender identity and social sex role are not necessarily congruent. A child or adolescent might be gender role nonconforming, that is, a predominantly feminine boy or a predominantly masculine girl.

Sexual Orientation and Behavior

Sexual orientation refers to attractions, behaviors, fantasies, and emotional attachments toward men, women, or both. Sexual behavior refers to any sensual activity to pleasure oneself or another person sexually.

Gender Variant and Transgender

Gender variant refers to any gender identity or role that varies from what is typically associated with one’s sex assigned at birth. Sometimes the term gender variant identity is used to refer to variation in gender identity and in that case is synonymous with transgender. Transgender people are a diverse group of individuals who cross or transcend culturally defined categories of gender. They include transsexuals (who typically live in the cross-gender role and seek hormonal and/or surgical interventions to modify primary or secondary sex characteristics); cross-dressers or transvestites (who wear clothing and adopt behaviors associated with the other sex for emotional or sexual gratification and may spend part of the time in the cross-gender role); drag queens and kings (female and male impersonators); and individuals identifying as bigender (both man and woman) or gender queer (gender variant). Transgender individuals may be attracted to men, women, or other transgender persons.

Factors That Influence Sexual Identity Development

During prenatal sexual development, a gene located on the Y chromosome (XRY) induces the development of testes. The hormones produced by the testes direct sexual differentiation in the male direction resulting in the development of male internal and external genitalia. In the absence of this gene in XX chromosomal females, ovaries develop and sexual differentiation proceeds in the female direction resulting in female internal and external genitalia. These hormones may also play a role in sexual differentiation of the brain. In disorders of sex development, chromosomal and prenatal hormonal sex varies from this typical developmental pattern and may result in ambiguous genitalia at birth (Chapter 582).

Gender identity develops early in life and is typically fixed by 2-3 yr of age. Children first learn to identify their own and others’ sex (gender labeling), then learn that gender is stable over time (gender constancy), and finally learn that gender is permanent (gender consistency). What determines gender identity remains largely unknown, but it is thought to be an interaction of biologic, environmental, and sociocultural factors.

Some evidence has been found for the impact of biologic and environmental factors on social sex role and gender role behavior, while their impact on gender identity remains less clear. Animal research has shown the influence of prenatal hormones on sexual differentiation of the brain. In humans, prenatal exposure to unusually high levels of androgens in girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) has been associated with more masculine gender role behavior, gender variant identity, and same-sex sexual orientation, but cannot account for all of the variance found (Chapter 570). Research on environmental factors has focused on the influence of sex-typed socialization. Social sex role stereotypes develop early in life. Until later in adolescence, boys and girls are typically socially segregated by gender, reinforcing sex-typed characteristics such as boys’ focus on rough-and-tumble play and asserting dominance, and girls focus on verbal communication and creating relationships. Parents, other adults, teachers, peers, and the media serve as gender socializing role models and agents by treating boys and girls differently.

For information on the development of sexual orientation, see Chapter 104.3.

Gender Variance/Gender Role Nonconformity Among Children and Adolescents

Prevalence

Gender variance and gender role nonconformity need to be distinguished from a gender variant or transgender identity. The former operate on the level of social sex role, whereas the latter is about variation in core gender identity. Gender role nonconformity is more common among girls (7%) than boys (5%), but boys are referred more often than girls for concerns regarding gender identity and role. This is likely due to parents, teachers, and peers being less tolerant of gender variant behaviors in boys than in girls.

Gender variance as part of exploring one’s gender identity and role is part of normal sexual development. Gender variance in childhood may or may not persist into adolescence. Marked gender variance in adolescence often persists into adulthood. Only a minority of gender variant children develop an adult transgender identity; most develop a gay or lesbian identity and some, a heterosexual identity.

Etiology of Gender Variant Behavior

Prenatal hormones play a role in the development of gender role nonconformity, but cannot completely account for all of the variance. In addition, a heritable component of gender variant behavior exists, but twin studies indicate that genetic factors do not account for all of the variance. Family of origin factors hypothesized to play a role in the development of gender variance lack empirical support. Maternal psychopathology and emotional absence of the father are the only factors shown to be associated with gender variance, yet it is unclear whether these factors are cause or effect.

Stigma, Stigma Management, and Advocacy

Children with gender variance are subject to ostracism from peers, which may negatively impact their psychosocial adjustment and lead to social isolation, loneliness, low self esteem, and behavioral problems. To assist children and families, individual stigma management strategies as well as interventions to change the environment can be offered. Stigma management might involve consultation with a health professional to provide support and education, normalizing the gender variant behavior and encouraging the child and family to build on the child’s strengths and interests to foster self esteem. It might also involve making choices about certain preferences (e.g., a boy who likes to wear head bands) to limit these to times and environments that are more accepting. Most health professionals agree that too much focus on curtailing gender variant behavior leads to increased shame and undermines the child’s self esteem.

The health professional and family can also assist the child or adolescent to find others with similar interests (within and beyond the gender related interests) to strengthen positive peer support. Equally important are interventions in school and society to raise awareness and promote accepting and positive attitudes, take a stand against bullying and abuse, and implement anti-bullying policies and initiatives. Gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and straight alliance groups are helpful in providing a haven for gender variant youth as well as recognizing them as part of diversity to be respected and embraced within the school system.

Gender Variant Identity/Transgender Children and Adolescents

Prevalence

About 1.3% of parents of 4-5 yr old boys report that their son wished to be of the opposite sex, and 0% for 12-13 yr olds; for girls these percentages are 5% for 4-5 yr olds and 2.7% for 12-13 yr olds.

Boys are referred by caregivers more often than girls for concerns regarding gender identity. Only a minority of children’s gender identity concerns persist into adolescence (20% in 1 study of boys). Persistence of gender identity concerns from adolescence into adulthood is higher; the majority identify as transgender in adulthood and may pursue sex reassignment. On the basis of adults enrolled in a national sex reassignment program in the Netherlands, the prevalence of adult transsexualism is estimated at 1 : 11,900 for male-to-females and 1 : 30,400 for female-to-males.

Etiology of a Gender Variant Identity

The etiology of a gender variant or transgender identity remains unknown. Factors hypothesized to play a role in the development of a gender variant identity include environmental and biologic factors. Gender variant children seem to have more trouble than other children with basic cognitive concepts concerning their gender. They may experience emotional distance from their father. Whether these factors are cause or effect remains unclear. Another hypothesis that has been examined is that boys with a gender variant identity are more physically attractive and hence solicit a different response from parental identification figures.

There may be an influence of prenatal and perinatal hormones on sexual differentiation of the brain. Some girls with CAH develop a male gender identity, yet most do not. The size of the sex-dimorphic central part of the red nucleus of the stria terminalis (BSTc) in the hypothalamus of male-to-female transsexuals is smaller than in males and within the range of nontranssexual women; the opposite is true for a female-to-male transsexuals. This structure is regulated by hormones in animals, but in humans no evidence yet exists of a direct relationship between prenatal and perinatal hormones and the sexually dimorphic nature of this nucleus.

Clinical Presentation

Children with a gender variant identity may experience 2 sources of stress: distress inherent to the incongruence between sex assigned at birth and gender identity (gender dysphoria) or distress associated with social stigma. The 1st source of distress is reflected in discomfort with the developing primary and secondary sex characteristics and the gender role assigned at birth. The 2nd source of distress relates to feeling different, not fitting in, peer ostracism, and social isolation, and may result in shame, low self-esteem, anxiety, or depression.

Boys with a gender variant identity may at an early age identify as a girl, expect to grow up female, or express the wish to do so. They may experience distress about being a boy and/or having a male body, prefer to urinate in a sitting position, and express a specific dislike of their male genitals and even want to cut off their genitals. They may dress up in girls’ clothes as part of playing dress up or in private. Girls may identify as a boy, expect or wish to grow up male. They may experience distress about being a girl and/or having a female body, pretend to have a penis, or expect to grow one. Girls may express a dislike of feminine clothing and hairstyles. In early childhood, children may spontaneously express these concerns, yet depending on the response of the environment, these feelings may go “underground” and be kept more private. The distress may intensify by the onset of puberty; the physical changes of puberty are described by many transsexual adolescents and adults as traumatic.

Children and adolescents with a gender variant identity may struggle with a number of general behavior problems. Both boys and girls have a predominance of internalizing (anxious and depressed) as opposed to externalizing behavioral difficulties. Compared to controls, gender variant boys are more prone to anxiety, have more negative emotions and a higher stress response, and are rated lower in self-worth, social competence, and psychologic well-being. Gender variant children have more peer relationship difficulties than controls. Both femininity in boys and masculinity in girls are socially stigmatized, although the former seems to carry a higher level of stigma. Boys have been shown to be teased more than girls; teasing for boys increases with age. Poor peer relations is the strongest predictor of behavior problems in both boys and girls who are gender variant.

Gender variant adolescents may struggle with a number of adjustment problems as a result of social stigma and lack of access to transgender-specific health care. Gender variant youth, especially those of color, are vulnerable to verbal and physical abuse, academic difficulties, school dropout, illicit hormone and silicone use, substance use, difficulty finding employment, homelessness, sex work, forced sex, incarceration, HIV/STIs, and suicide. Parental support can buffer against psychologic distress, yet many parents still react negatively to their child’s gender variance, although mothers tend to be more supportive than fathers.

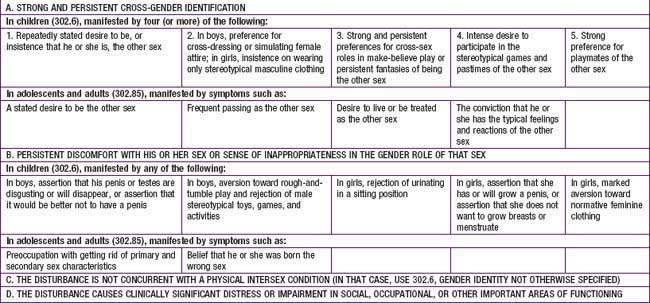

The Diagnosis of Gender Identity Disorder: Criteria and Critique

Gender identity disorder is classified as a mental disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and International Classification of Diseases, which, particularly for children, is controversial. Diagnostic criteria conflate gender variant identity with gender variant behavior. A child could receive the DSM diagnosis without having indicated “a repeated stated desire to be or insistence that he or she is, the other sex,” because only 4 of the 5 A category criteria need to be met (Table 104-6). Critics have argued that the distress children experience is mainly the result of social stigma rather than “a manifestation of a behavioral, psychological, or biological dysfunction in the individual” and hence would not meet the definition of a mental disorder. Critics have also expressed concern about children with normal variation in gender role being labeled with a mental disorder perpetuating social stigma, yet there is a tendency of clinicians to underdiagnose rather than overdiagnose children whose gender variance goes beyond behavior and who report gender dysphoria. These children could potentially benefit from the diagnosis to receive early treatment in the form of support, education, advocacy, and, in case of persistent and severe gender dysphoria, puberty-delaying hormone therapy as a reversible precursor to feminizing or masculinizing hormone therapy.

Transgender Identity Development

A stage model of “coming out” might be helpful to understand the experience and potential challenges transgender youth might face. In the pre–coming out stage, the individual is aware that their gender identity is different from that of most boys and girls. In addition to a gender identity that varies from sex assigned at birth, some of these children are also gender role nonconforming while others are not. Those who are also gender role nonconforming cannot hide their transgender identity, are noticed for who they are, and may face teasing, ridicule, abuse, and rejection. They must learn to cope with these challenges at an early age and usually proceed quickly to the next stage of coming out. Children who are not visibly gender role nonconforming are able to avoid stigma and rejection by hiding their transgender feelings. They often experience a split between their gender identity cherished in private and expressed in a fantasy world, and a “false self” presented outwardly to fit in and meet gendered expectations. These individuals often times proceed to coming out later in life.

Coming out involves acknowledging one’s transgender identity to self and others (parents, other caregivers, trusted health providers, peers). An open and accepting attitude is essential; rejection can perpetuate stigma and its negative emotional consequences. By accessing transgender community resources, including peer support (either online or offline), the transgender youth can then proceed to the exploration stage. This is a time of learning as much as possible about being transgender, getting to know similar others, and experimenting with various options for gender expression. Changes in gender role are carefully considered, as are medical interventions to masculinize or feminize the body to alleviate dysphoria. Successful resolution of this stage is a sense of pride in being transgender and comfort with gender role.

Once gender dysphoria has been alleviated, the individual can proceed with other human development tasks, including dating and relationships in the intimacy stage. As a result of social stigma and rejection, transgender individuals may struggle with feeling unlovable. Sexual development has often been compromised by gender and genital dysphoria. Now that greater comfort has been achieved with gender identity and role, dating and sexual intimacy have a greater chance of succeeding. Finally, in the integration stage, transgender is no longer the most important signifier of identity but one of several important parts of overall identity.

Interventions and Treatment

Health providers can assist gender variant children, adolescents, and their families by directing them to resources and by helping them to make informed decisions about changes in gender role and the available medical interventions to reduce intense and persistent gender dysphoria. To alleviate socially induced distress, interventions focus on stigma management and stigma reduction. It might be in the child’s best interest to set reasonable limits on gender variant expression contributing to teasing and ridicule. The main goal of these interventions is not to change the child’s gender variant behavior but to assist families, schools, and the wider community to create a supportive environment in which the child can thrive and safely explore his or her gender identity and expression. Decisions to change gender roles, particularly in school, are not to be taken lightly and are best carefully anticipated and planned in consultation with parents, child, teachers, school counselor, and other providers involved in the adolescent’s care. Medical interventions are available as early as Tanner Stage 2. Such treatment is guided by the Standards of Care set forth by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Although some controversy still exists about the appropriateness of early medical intervention, follow up studies of adolescents treated in accordance with these guidelines show it to be effective in alleviating intense and persistent gender dysphoria. Care needs to be taken not to foreclose the child’s exploration of identity.

Pediatricians who encounter transgender youth in their practice should be careful not to make assumptions about gender and sexual identity, but rather ask youth how they would describe themselves. This includes asking if they like being a boy or girl, have ever questioned this, or wished they were born the other sex; have a preferred nickname or pronoun (he or she; if not sure, avoid pronouns); and how they feel about their maturing body and sex characteristics, and what they would change about that if they could. Extra caution should be exercised during physical and genital exams because transgender youth may be particularly uncomfortable with their anatomy. When considering contraceptive options for female-to-males, alternatives to feminizing agents should be explored. For transgender-specific medical interventions, transgender youth should be referred to specialists in the treatment of gender dysphoria (see World Professional Association for Transgender Health, www.wpath.org). For other health concerns, ensure referral to transgender or gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgendered (GLBT) friendly providers, especially in the case of gender segregated treatment facilities. Advocates for Youth (www.advocatesforyouth.org) and Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (www.pflag.org) offer excellent support resources for transgender youth and their families.

Biro FM. Puberty. Adolesc Med. 2007;18:425-433.

Bockting WO, Goldberg JM, editors. Guidelines for transgender care. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Medical Press, 2007.

Cohen-Kettenis PT, Pfäfflin F. Transgenderism and intersexuality in childhood and adolescence: making choices. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003.

2004 Frankowski BL and the Committee on Adolescence: Sexual orientation and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1827-1832.

Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis P, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, et al. Endocrine treatment of transsexual persons: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3132-3134.

Lee PA, Houk C, Ahmed SF, et al. International consensus conference on intersex organized by the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society and the European Society for Paediatrics Endocrinology. Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. Pediatrics. 2006;118:814-815.

Meyer WIII, Blocking W, Cohen-Kettenis PT, et al. The standards of care for gender identity disorders, sixth version. J Psychol Hum Sexuality. 2001;13:130.

Olson J, Forbes C, Belzer M. Management of the transgender adolescent. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(2):171-176.

104.3 Adolescent Homosexuality

Sexual orientation is a persistent pattern of physical and/or emotional attraction to members of the same or the opposite sex. It encompasses different aspects of sexuality, including sexual fantasy, emotional attraction, sexual behavior, self-identification, and cultural affiliation. The heterosexual or homosexual direction of these different dimensions may be inconsistent, defying the simple categorization of individuals as heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual. Sexual orientation can be viewed as a continuum between absolute heterosexuality and homosexuality. Homosexuality refers to a persistent pattern of same-sex arousal, accompanied by weak or absent heterosexual arousal; and bisexuality refers to attractions for both genders. Most homosexual people refer to themselves as gay men and lesbian women; and many young people refer to themselves as “queer,” “curious,” and “questioning.” Homosexual refers to both males and females, whereas the term gay applies specifically to men and lesbian to women.

Epidemiology

Homosexuality has existed in all societies and cultures and in all times. Prevalence estimates vary according to the time, place, and definitions. Many youths begin adolescence unsure of their sexual orientation, but uncertainty generally resolves with advancing age and sexual experience. In a large state-wide sample of public high school students in the USA, reported homosexual attractions (4.5%) exceeded fantasies, the latter being more common in girls (3.1%) than in boys (2.2%). Overall, 1.1% of students described themselves as predominantly homosexual or bisexual. The prevalence of reported homosexual experiences remained constant (0.9%) among girls, but increased from 0.4-2.8% in boys between the ages of 12 and 18 yr. Only about 30% of the teens reporting homosexual experiences or fantasies identified themselves as homosexual or bisexual.

Etiology

Males and females develop and experience sexual orientation in very different ways. Biology influences sexual orientation development to some degree and possibly affects males and females differently. Factors yet to be identified might organize and activate key areas of the brain early in life to shape sexual response. Neuroanatomic, neurophysiologic, and functional differences (e.g., left-handedness) related to sexual orientation in men and in women point to centrally mediated biologic effects.

Yet, the underlying activating mechanism puzzles scientists. Having a greater number of older brothers, the “fraternal birth order effect,” is a robust correlate of homosexuality in males (but not females). In females, the apparent association between homosexuality and in utero exposure to androgens implicates hormones. The relative concordance of homosexuality in monozygotic twins, as compared to dizygotic and non-twin sibships, highlights the role of genetic make-up, especially in males. A candidate gene for an X-linked type of male homosexuality is under investigation.

Also uncertain are the ways biology might interact with environment and experience in shaping sexual identity. Hypothetically, environment modulates the expression of one’s fundamental biologic predisposition by influencing social norms and the visibility of homosexual people. There are no differences in the familial and social backgrounds of homosexual and heterosexual men and women, nor is there evidence that homosexuality is related to abnormal parenting, sexual abuse, or other traumatic events.

Development of a Homosexual Identity

The timing and tempo of sexual orientation development varies among individuals based on demographic, cultural, social, historical, and maturational factors. The process typically unfolds with an initial awareness of same-sex attractions as early as the 1st decade in life, followed by sexual orientation identification, sexual debut, and possibly disclosure to others during adolescence and young adulthood. Sexual attractions might be the earliest and best indicator of ultimate sexual identity.

Awareness of attractions is a well-recognized and necessary precursor of disclosure; but self-identification can precede sexual behavior, and vice versa. The developmental process seldom is direct and easy. Misinformation and stigma can lead to significant inner turmoil and anxiety. Volitional disclosure usually starts with telling close friends before parents, and with mothers before fathers; but disclosure can happen unwittingly or prematurely, creating considerable distress. Successful resolution of the developmental process, characterized by personal acceptance and healthy intimate relationships, depends on many factors, such as maturity, access to accurate information, positive role models, and social support. Many adolescents reach adulthood without event, whereas others have a much more challenging transition.

Implications for Health

Homophobia

The psychosocial problems among gay and lesbian youths are best understood in the context of homophobia. Homophobia is an irrational fear, hatred, or otherwise distorted perception of homosexuality that can manifest in personal discomfort, stereotypes, prejudice, and violence. At a time in life when peers play a critical role in healthy personal and social development, isolation and stigma can be highly traumatic. Compared with classmates, homosexual students are more likely to fear for their safety and to be attacked and injured. With repeated exposure, homosexual youths might internalize negative stereotypes and engage in self-defeating behaviors.

Social Issues

Academic underachievement, truancy, and dropping out are common consequences of abuse and violence at school. Some parents are unable to adopt a supportive attitude, and a substantial number of homosexual children run away or are evicted. Homosexual young people are overrepresented in homeless and runaway populations across the USA. Life on the streets exposes them to drugs and sexual abuse and promotes illegal conduct for survival.

Mental Health Issues

Substance abuse, anxiety, depression, suicide attempts, and disordered eating behaviors are prevalent. Compared with heterosexual peers, homosexual youths initiate tobacco use at younger ages and are more likely to smoke regularly. A study of 13-21 yr old gay and bisexual male adolescents found that 24.5% of participants reported frequent (>40 times/yr) use of alcohol; 8.4%, cannabis; and 2.4%, cocaine or crack. More than 4% had used intravenous drugs in the last year alone. Methamphetamine and other “club” drug use may be fueling the spread of HIV infection.

Rates of attempted suicide among homosexual youths, especially males, are consistently higher than expected in the general population of adolescents, ranging from 20-42%. Identified risk factors include gender nonconformity, early awareness of homosexuality, gay-related stress, victimization by violence, lack of social support, school drop-out, family problems, suicide attempts by friends or relatives, and homelessness.

Data on disordered eating behavior are sparse and conflicting. As compared to young heterosexuals of the same sex, lesbians generally have better body image and are more likely to be overweight, while young gay men have worse body image and are more likely to restrict eating and/or engage in compensatory weight loss strategies.

Medical Threats to Health

Homosexual adolescents generally have the same medical concerns as heterosexual youths. Risky sexual behaviors, not sexual orientation, endanger health. The most common and serious sexually-related conditions arise from unprotected anal intercourse. The epithelial surfaces of the fragile rectal mucosa can be easily damaged during sex, facilitating the transmission of pathogens. Rectal intercourse has been shown to be the most efficient route of infection by hepatitis B (Chapter 350), cytomegalovirus (Chapter 247), and HIV (Chapter 268). Oral-anal or digital-anal contact can transmit enteric pathogens, such as the hepatitis A virus. Unprotected oral sex also can lead to oropharyngeal disease in the receptive partner and gonococcal and non-gonococcal urethritis for the insertive partner. Certain STIs, particularly ulcerative diseases, such as syphilis and herpes simplex virus infection, facilitate the spread of HIV.

Among U.S. adolescents and young adults, young men who have sex with men (YMSM) continue to have the greatest toll of HIV/AIDS for various reasons, including misinformation, non-communication with partners about risk reduction, potentially false assumptions about partners’ serostatus, substance use, and impaired reasoning and judgment. Although possible, female-to-female sexual transmission of HIV is inefficient, and women who only engage in same-sex behavior are less likely than other youths to acquire a STI.

Recommendations for Care

The American Academy of Pediatrics recognizes physicians’ responsibility to provide comprehensive, nonjudgmental health care and guidance to gay and lesbian adolescents and to others who are struggling with sexual orientation issues. The goal of care for homosexual adolescents is promoting normal adolescent development, social and emotional well-being, and physical health.

Clinicians who are unable to offer nonjudgmental care and information should refer patients to better resources. Placed in a waiting area, written material about sexual orientation, support groups, and community resources signal that the staff is open to discussing sexuality. Use of well-designed comprehensive health history forms, like the American Medical Association’s Guidelines for Adolescent Prevention Services Questionnaire, can trigger conversation about sexual identity and related issues. Privacy, confidentiality, sensitivity, and patience are the cornerstones of effective communication.

Evaluation

Providers should be aware of potential threats to the medical and psychosocial health of homosexual teenagers and screen for them appropriately. Classifying an adolescent’s sexual orientation seldom is necessary, but a thoughtful assessment of emotional, social, and physical health can uncover risks and direct further evaluation and treatment. Questions in the sexual history should avoid heterosexual assumptions, asking instead about the direction of romantic interests and partners. With some exceptions noted below, the physical examination and laboratory evaluation of homosexual adolescents are the same as for any teenagers.

Prevention, Treatment, and Referrals

Special emphasis should be placed on education and counseling to prevent the spread of HIV and STIs through safer sexual behavior, including limiting the numbers of sexual partners, avoiding anal intercourse, staying sober in sexual situations, and consistently using condoms. Young men who meet sexual partners online, as opposed to face-to-face, may have more partners; but they do not necessarily have riskier sex. The use of dental dams, cut open latex condoms, or plastic wrap during oral sex, and the use of latex condoms for sexual appliances are recommended for lesbians. Given the fact that some homosexual adolescents engage in sex with the opposite sex, pregnancy prevention should be addressed.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), vaccination against hepatitis A and B is recommended for all men who have sex with men (MSM) in whom previous infection or immunization cannot be documented. Preimmunization serologic testing can reduce the cost of vaccinating MSM who are already immune to these infections but should not delay vaccination. The CDC recommends that sexually active MSM, regardless of condom use history, obtain the following tests at least annually:

In addition, though firm recommendations are pending, some specialists routinely obtain type-specific serologic tests for herpes simplex virus-2 and vaccinate gay adolescents and other young MSM with Gardasil preventatively. For treatment of STIs, see Chapter 114. Complicated STIs and HIV infection warrant referral to medical subspecialists.

Many minor psychosocial problems can be handled by referral to social support groups, sometimes known as gay–straight alliances. In some localities, specialized social service agencies can help with social, educational, vocational, housing, and other unmet needs. Adolescents with serious psychiatric symptoms, such as suicidal ideation, depression, and chemical dependency, should be referred to mental health specialists with experience treating homosexual adolescents. Individual or family therapy might be indicated for personal, family, or environmental adjustment difficulties. Not only is it ineffective, so-called reparative therapy aiming to change sexual orientation is contraindicated because of its potential to heighten guilt and anxiety.

Well-informed professionals can help adolescents and their parents to explore their feelings and learn about topics related to homosexuality and its etiology, psychologic normalcy, spiritual and cultural implications, disclosure to a significant other, preventive care, and community resources. With appropriate support from families, school, and communities, homosexual youths have the same potential as others to lead happy, healthy, and productive lives.

Horvath KJ, Rosser BR, Remafedi G. Sexual risk taking among young internet-using men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1059-1067.

Mustanski BS, Chivers ML, Bailey JM. A critical review of recent biological research on human sexual orientation. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2002;13:89-140.

Remafedi G. Sexual orientation and youth suicide. JAMA. 1999;282:1291-1292.

Russell ST, Franz BT, Driscoll AK. Same-sex romantic attraction and experiences of violence in adolescence. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:903-906.

Savin-Williams RC, Diamond LM. Sexual identity trajectories among sexual-minority youths: gender comparisons. Arch Sex Behav. 2000;29:607-627.

Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Karon JM, et al. HIV prevalence and associated risks in young men who have sex with men. JAMA. 2000;84:198-204.