Chapter 239 Rubella

Rubella (German measles or 3-day measles) is a mild, often exanthematous disease of infants and children that is typically more severe and associated with more complications in adults. Its major clinical significance is transplacental infection and fetal damage as part of the congenital rubella syndrome (CRS).

Etiology

Rubella virus is a member of the family Togaviridae and is the only species of the genus Rubivirus. It is a single-stranded RNA virus with a lipid envelope and 3 structural proteins, including a nucleocapsid protein that is associated with the nucleus and 2 glycoproteins, E1 and E2, that are associated with the envelope. The virus is sensitive to heat, ultraviolet light, and extremes of pH but is relatively stable at cold temperatures. Humans are the only known host.

Epidemiology

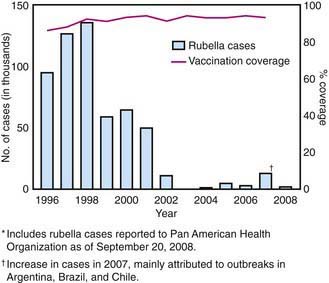

In the prevaccine era, rubella appeared to occur in major epidemics every 6-9 yr, with smaller peaks interspersed every 3-4 yr, and was most common in preschool and school-aged children. Following introduction of the rubella vaccine, the incidence fell by >99%, with a relatively higher percentage of infections reported among persons >19 yr of age. After years of decline, a resurgence of rubella and CRS occurred during 1989-1991 (Fig. 239-1). Subsequently, a 2-dose recommendation for rubella vaccine was implemented and resulted in a decrease in incidence of rubella from 0.45/100,000 in 1990 to 0.1/100,000 in 1999 and a corresponding decrease of CRS, with an average of 6 infants with CRS reported annually from 1992 to 2004. Mothers of these infants tended to be young, Hispanic, or foreign born. The number of reported cases of rubella continued to decline in the early part of this decade.

Figure 239-1 Number of confirmed rubella cases and percentage coverage with first dose of measles-containing vaccine—the Americas, 1996–2008.*

(From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Progress toward elimination of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome—the Americas, 2003–2008, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57:1176–1179, 2008.)

Pathology

Little information is available on the pathologic findings in rubella occurring postnatally. The few reported studies of biopsy or autopsy material from cases of rubella revealed only nonspecific findings of lymphoreticular inflammation and mononuclear perivascular and meningeal infiltration. The pathologic findings for CRS are often severe and may involve nearly every organ system (Table 239-1).

Table 239-1 PATHOLOGIC FINDINGS IN CONGENITAL RUBELLA SYNDROME

| SYSTEM | PATHOLOGIC FINDINGS |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Patent ductus arteriosus |

| Pulmonary artery stenosis | |

| Ventriculoseptal defect | |

| Myocarditis | |

| Central nervous system | Chronic meningitis |

| Parenchymal necrosis | |

| Vasculitis with calcification | |

| Eye | Microphthalmia |

| Cataract | |

| Iridocyclitis | |

| Ciliary body necrosis | |

| Glaucoma | |

| Retinopathy | |

| Ear | Cochlear hemorrhage |

| Endothelial necrosis | |

| Lung | Chronic mononuclear interstitial pneumonitis |

| Liver | Hepatic giant cell transformation |

| Fibrosis | |

| Lobular disarray | |

| Bile stasis | |

| Kidney | Interstitial nephritis |

| Adrenal gland | Cortical cytomegaly |

| Bone | Malformed osteoid |

| Poor mineralization of osteoid | |

| Thinning cartilage | |

| Spleen, lymph node | Extramedullary hematopoiesis |

| Thymus | Histiocytic reaction |

| Absence of germinal centers | |

| Skin | Erythropoiesis in dermis |

Pathogenesis

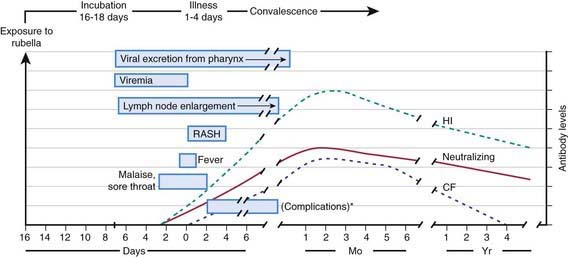

The viral mechanisms for cell injury and death in rubella are not well understood for either postnatal or congenital infection. Following infection, the virus replicates in the respiratory epithelium, then spreads to regional lymph nodes (Fig. 239-2). Viremia ensues and is most intense from 10 to 17 days after infection. Viral shedding from the nasopharynx begins about 10 days after infection and may be detected up to 2 wk following onset of the rash. The period of highest communicability is from 5 days before to 6 days after the appearance of the rash.

Figure 239-2 Pathophysiologic events in postnatally acquired rubella virus infection. *Possible complications include arthralgia and/or arthritis, thrombocytopenic purpura, and encephalitis.

(From Lamprecht CL: Rubella virus. In Beshe RB, editor: Textbook of human virology, ed 2, Littleton, MA, 1990, PSG Publishing, p 685.)

The most important risk factor for severe congenital defects is the stage of gestation at the time of infection. Maternal infection during the 1st 8 wk of gestation results in the most severe and widespread defects. The risk for congenital defects has been estimated at 90% for maternal infection before 11 wk of gestation, 33% at 11-12 wk, 11% at 13-14 wk, and 24% at 15-16 wk. Defects occurring after 16 wk of gestation are uncommon, even if fetal infection occurs.

Causes of cellular and tissue damage in the infected fetus may include tissue necrosis due to vascular insufficiency, reduced cellular multiplication time, chromosomal breaks, and production of a protein inhibitor causing mitotic arrests in certain cell types. The most distinctive feature of congenital rubella is chronicity. Once the fetus is infected early in gestation, the virus persists in fetal tissue until well beyond delivery. Persistence suggests the possibility of ongoing tissue damage and reactivation, most notably in the brain.

Clinical Manifestations

Postnatal infection with rubella is a mild disease not easily discernible from other viral infections, especially in children. Following an incubation period of 14-21 days, a prodrome consisting of low-grade fever, sore throat, red eyes with or without eye pain, headache, malaise, anorexia, and lymphadenopathy begins. Suboccipital, postauricular, and anterior cervical lymph nodes are most prominent. In children, the 1st manifestation of rubella is usually the rash, which is variable and not distinctive. It begins on the face and neck as small, irregular pink macules that coalesce, and it spreads centrifugally to involve the torso and extremities, where it tends to occur as discrete macules (Fig. 239-3). About the time of onset of the rash, examination of the oropharynx may reveal tiny, rose-colored lesions (Forchheimer spots) or petechial hemorrhages on the soft palate. The rash fades from the face as it extends to the rest of the body so that the whole body may not be involved at any 1 time. The duration of the rash is generally 3 days, and it usually resolves without desquamation. Subclinical infections are common, and 25-40% of children may not have a rash.

Laboratory Findings

Leukopenia, neutropenia, and mild thrombocytopenia have been described during postnatal rubella.

Diagnoses

Specific diagnosis of rubella is important for epidemiologic reasons, for diagnosis of infection in pregnant women, and for confirmation of the diagnosis of congenital rubella. The most common diagnostic test is rubella immunoglobulin M (IgM) enzyme immunosorbent assay. As with any serologic test, the positive predictive value of testing decreases in populations with low prevalence of disease. Tests should be performed in the context of a supportive history of exposure or consistent clinical findings. The relative sensitivity and specificity of commercial kits used in most laboratories range from 96% to 99% and 86% to 97%, respectively. A caveat for testing of congenitally infected infants early in infancy is that false-negative results may occur owing to competing immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies circulating in these patients. In such patients, an IgM capture assay, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, or viral culture should be performed for confirmation.

Differential Diagnoses

Rubella may manifest as distinctive features suggesting the diagnosis. It is frequently confused with other infections because it is uncommon, similar to other viral exanthematous diseases, and demonstrates variability in the presence of typical findings. In severe cases it may resemble measles. The absence of Koplik spots and a severe prodrome as well as a shorter course allow for differentiation from measles. Other diseases frequently confused with rubella include infections caused by adenoviruses, parvovirus B19 (erythema infectiosum), Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

Complications

Complications following postnatal infection with rubella are infrequent and generally not life threatening.

Postinfectious thrombocytopenia occurs in about 1/3,000 cases of rubella and occurs more frequently among children and in girls. It manifests about 2 wk following the onset of the rash as petechiae, epistaxis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and hematuria. It is usually self-limited.

Arthritis following rubella occurs more commonly among adults, especially women. It begins within 1 wk of onset of the exanthem and classically involves the small joints of the hands. It also is self-limited and resolves within weeks without sequelae. There are anecdotal reports and some serologic evidence linking rubella with rheumatoid arthritis, but a true causal association remains speculative.

Encephalitis is the most serious complication of postnatal rubella. It occurs in 2 forms: a postinfectious syndrome following acute rubella and a rare progressive panencephalitis manifesting as a neurodegenerative disorder years following rubella.

Postinfectious encephalitis is uncommon, occurring in 1/5,000 cases of rubella. It appears within 7 days after onset of the rash, consisting of headache, seizures, confusion, coma, focal neurologic signs, and ataxia. Fever may recrudesce with the onset of neurologic symptoms. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) may be normal or have a mild mononuclear pleocytosis and/or elevated protein concentration. Virus is rarely, if ever, isolated from CSF or brain, suggesting a noninfectious pathogenesis. Most patients recover completely, but mortality rates of 20% and long-term neurologic sequelae have been reported.

Progressive rubella panencephalitis (PRP) is an extremely rare complication of either acquired rubella or CRS. It has an onset and course similar to those of the subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) associated with measles (Chapter 238). Unlike in the postinfectious form of rubella encephalitis, however, rubella virus may be isolated from brain tissue of the patient with PRP, suggesting an infectious pathogenesis, albeit a “slow” one. The clinical findings and course are undistinguishable from those of SSPE and transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (Chapter 270). Death occurs 2-5 yr after onset.

Other neurologic syndromes rarely reported with rubella include Guillain-Barré syndrome and peripheral neuritis. Myocarditis is a rare complication.

Congenital Rubella Syndrome

In 1941 an ophthalmologist first described a syndrome of cataracts and congenital heart disease that he correctly associated with rubella infections in the mothers during early pregnancy (Table 239-2). Shortly after the first description, hearing loss was recognized as a common finding often associated with microcephaly. In 1964-1965 a pandemic of rubella occurred, with 20,000 cases reported in the USA leading to >11,000 spontaneous or therapeutic abortions and 2,100 neonatal deaths. From this experience emerged the expanded definition of CRS that included numerous other transient or permanent abnormalities.

Table 239-2 CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF CONGENITAL RUBELLA SYNDROME IN 376 CHILDREN FOLLOWING MATERNAL RUBELLA*

| MANIFESTATION | RATE (%) |

|---|---|

| Deafness | 67 |

| Ocular | 71 |

| Cataracts | 29 |

| Retinopathy | 39 |

| Heart disease† | 48 |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 78 |

| Right pulmonary artery stenosis | 70 |

| Left pulmonary artery stenosis | 56 |

| Valvular pulmonic stenosis | 40 |

| Low birthweight | 60 |

| Psychomotor retardation | 45 |

| Neonatal purpura | 23 |

| Death | 35 |

* Other findings: hepatitis, linear streaking of bone, hazy cornea, congenital glaucoma, delayed growth.

† Findings in 87 patients with congenital rubella syndrome and heart disease who underwent cardiac angiography.

From Cooper LZ, Ziring PR, Ockerse AB, et al: Rubella: clinical manifestations and management, Am J Dis Child 118:18–29, 1969.

Nerve deafness is the single most common finding among infants with CRS. Most infants have some degree of intrauterine growth restriction. Retinal findings described as salt-and-pepper retinopathy are the most common ocular abnormality but have little early effect on vision. Unilateral or bilateral cataracts are the most serious eye finding, occurring in about a third of infants (Fig. 239-4). Cardiac abnormalities occur in half of the children infected during the 1st 8 wk of gestation. Patent ductus arteriosus is the most frequently reported cardiac defect, followed by lesions of the pulmonary arteries and valvular disease. Interstitial pneumonitis leading to death in some cases has been reported. Neurologic abnormalities are common and may progress following birth. Meningoencephalitis is present in 10-20% of infants with CRS and may persist for up to 12 mo. Longitudinal follow-up through 9-12 yr of infants without initial retardation revealed progressive development of additional sensory, motor, and behavioral abnormalities, including hearing loss and autism. PRP has also been recognized rarely after CRS. Subsequent postnatal growth retardation and ultimate short stature have been reported in a minority of cases. Rare reports of immunologic deficiency syndromes have also been described.

A variety of late-onset manifestations of CRS have been recognized. In addition to PRP, they include diabetes mellitus (20%), thyroid dysfunction (5%), and glaucoma and visual abnormalities associated with the retinopathy, which had previously been considered benign.

Supportive Care

Postnatal rubella is generally a mild illness that requires no care beyond antipyretics and analgesics. Intravenous immunoglobulin or corticosteroids can be considered for severe, nonremitting thrombocytopenia.

Management of children with CRS is more complex and requires pediatric, cardiac, audiologic, ophthalmologic, and neurologic evaluation and follow-up because many manifestations may not be readily apparent initially or may worsen with time. Hearing screening is of special importance, because early intervention may improve outcomes in children with hearing problems due to CRS.

Prognosis

Postnatal infection with rubella has an excellent prognosis. Long-term outcomes of CRS are less favorable and somewhat variable. In an Australian cohort evaluated 50 yr after infection, many had chronic conditions but most were married and had made good social adjustments. A cohort from New York from the mid-1960s epidemic had less favorable outcomes, with 30% leading normal lives, 30% in dependent situations but functional, and 30% requiring institutionalization and continuous care.

Re-infection with wild virus occurs postnatally in both individuals who were previously infected with wild-virus rubella and in vaccinated individuals. Re-infection is defined serologically as a significant increase in IgG antibody level and/or an IgM response in an individual who has a documented preexisting rubella-specific IgG above an accepted cutoff. Re-infection may result in an anamnestic IgG response, an IgM and IgG response, or clinical rubella. There have been 29 reports of CRS following maternal re-infection in the literature. Re-infection with serious adverse outcomes to adults or children is rare and of unknown significance.

Prevention

Patients with postnatal infection should be isolated from susceptible individuals for 7 days after onset of the rash. Standard plus droplet precautions are recommended for hospitalized patients. Children with CRS may excrete the virus in respiratory secretions up to 1 yr of age, so contact precautions should be maintained for them until then, unless repeated cultures of urine and pharyngeal secretions have negative results. Similar precautions apply to patients with CRS with regard to attendance in school and out-of-home child care.

Exposure of susceptible pregnant women poses a potential risk to the fetus. For pregnant women exposed to rubella, a blood specimen should be obtained as soon as possible for rubella IgG–specific antibody testing; a frozen aliquot also should be saved for later testing. If the rubella antibody test result is positive, the mother is likely immune. If the rubella antibody test is negative, a 2nd specimen should be obtained 2-3 wk later and tested concurrently with the saved specimen. If both of these test negative, a 3rd specimen should be obtained 6 wk after exposure and tested concurrently with the saved specimen. If both the 2nd and 3rd specimens test negative, infection has not occurred. A negative 1st specimen and a positive test result in either the 2nd or 3rd specimen indicate that seroconversion has occurred in the mother, suggesting recent infection. Counseling should be provided about the risks and benefits of termination of pregnancy. The routine use of immune globulin for susceptible pregnant women exposed to rubella is not recommended and is considered only if termination of pregnancy is not an option because of maternal preferences. In such circumstances, immune globulin 0.55 mL/kg IM may be given with the understanding that prophylaxis may reduce the risk for clinically apparent infection but does not guarantee prevention of fetal infection.

Vaccination

Rubella vaccine in the USA consists of the attenuated RA 27/3 strain that is usually administered in combination with measles and mumps (MMR) or also with varicella (MMRV) in a 2-dose regimen at 12-15 mo and 4-6 yr of age. It theoretically may be effective as postexposure prophylaxis if administered within 3 days of exposure. Vaccine should not be administered to severely immunocompromised patients (e.g., transplant recipients). Patients with HIV infection who are not severely immunocompromised may benefit from vaccination. Fever is not a contraindication, but if a more serious illness is suspected, immunization should be delayed. Immune globulin preparations may inhibit the serologic response to the vaccine (Chapter 165). Vaccine should not be administered during pregnancy. If pregnancy occurs within 28 days of immunization, the patient should be counseled on the theoretical risks to the fetus. Studies of >200 women who had been inadvertently immunized with rubella vaccine during pregnancy showed that none of their offspring developed CRS. Therefore, interruption of pregnancy is probably not warranted.

Adverse reactions to rubella vaccination are uncommon in children. MMR administration is associated with fever in 5-15% of vaccines and rash in about 5%. Arthralgia and arthritis are more common following rubella vaccination in adults. Approximately 25% of postpubertal women experience arthralgia, and 10% experience arthritis. Peripheral neuropathies and transient thrombocytopenia may also occur.

As part of the worldwide effort to eliminate endemic rubella virus transmission and occurrence of CRS, maintaining high population immunity through vaccination coverage and high-quality integrated measles-rubella surveillance have been emphasized as being vital to its success.

Banatvala JE, Brown DWG. Rubella. Lancet. 2004;363:1127-1137.

Bloom S, Rguig A, Berraho A, et al. Congenital rubella syndrome burden in Morocco: a rapid retrospective assessment. Lancet. 2005;365:135-140.

Bullens D, Koenraad S, Vanhaesebrouck P. Congenital rubella syndrome after maternal reinfection. Clin Pediatr. 2000;39:113-116.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward control of rubella and prevention of congenital rubella syndrome—worldwide, 2009. MMWR. 2010;59(40):1307-1310.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward elimination of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome—the Americas, 2003–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:1176-1179.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rubella vaccination during pregnancy—United States, 1971–1988. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1989;38:289-292.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health: elimination of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome—United States, 1969–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:279-282.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Brief report: imported case of congenital rubella syndrome—New Hampshire, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:1160-1161.

Cooper LZ, Ziring PR, Ockerse AB, et al. Rubella: clinical manifestations and management. Am J Dis Child. 1969;118:18-29.

Corcoran C, Hardie DR. Serologic diagnosis of congenital rubella: a cautionary tale. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:286-287.

Dwyer DE, Robertson PW, Field PR. Clinical and laboratory features of rubella. Pathology. 2001;33:322-328.

Frey RK. Neurological aspects of rubella virus infection. Intervirology. 1997;40:167-175.

Hahne S, Macey J, van Binnendijk R, et al. Rubella outbreak in the Netherlands, 2004–2005. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:795-800.

McIntosh ED, Menser MA. A fifty-year follow-up of congenital rubella. Lancet. 1992;340:414-415.

Miller E, Cradock-Watson JE, Pollock TM. Consequences of confirmed maternal rubella at successive stages of pregnancy. Lancet. 1982;2:781-784.

Townsend JJ, Stroop WG, Baringer JR, et al. Neuropathology of progressive rubella panencephalitis after childhood rubella. Neurology. 1982;32:185-190.