Chapter 434 Diseases of the Pericardium

The heart is enveloped in a bilayer membrane, the pericardium, which normally contains a small amount of serous fluid. The pericardium is not vital to normal function of the heart, and primary diseases of the pericardium are uncommon. However, the pericardium may be affected by a variety of conditions (Table 434-1), often as a manifestation of a systemic illness and can result in serious, even life-threatening, cardiac compromise.

Table 434-1 ETIOLOGY OF PERICARDIAL DISEASE

CONGENITAL

INFECTIOUS

NONINFECTIOUS

434.1 Acute Pericarditis

Robert Spicer and Stephanie Ware

Pathogenesis

Inflammation of the pericardium may have only minor pathophysiologic consequences in the absence of significant fluid accumulation in the pericardial space. When the amount of fluid in the nondistensible pericardial space becomes excessive, pressure within the pericardium increases and is transmitted to the heart resulting in impaired filling. Although small to moderate amounts of pericardial effusion can be well tolerated and clinically silent, once the noncompliant pericardium has been distended maximally, any further fluid accumulation causes abrupt impairment of cardiac filling and is termed cardiac tamponade. When untreated, tamponade can lead to shock and death. Pericardial effusions may be serous/transudative, exudative/purulent, fibrinous, or hemorrhagic.

Clinical Manifestations

The most common symptom of acute pericarditis is chest pain, typically described as sharp/stabbing, positional, radiating, worse with inspiration, and relieved by sitting upright or prone. Cough, fever, dyspnea, abdominal pain, and vomiting are nonspecific symptoms associated with pericarditis. Additionally, signs and symptoms of organ system involvement may occur in the presence of generalized systemic disease.

Muffled or distant heart sounds, tachycardia, narrow pulse pressure, jugular venous distension, and a pericardial friction rub provide clues to the diagnosis of acute pericarditis. Cardiac tamponade is recognized by the excessive fall of systolic blood pressure (>10 mm Hg) with inspiration. This pulsus paradoxus can be assessed by careful auscultatory blood pressure determination (automated blood pressure cuffs are inadequate), arterial pressure line wave form, or pulse oximeter tracing inspection. Conditions other than cardiac tamponade, which may result in pulsus paradoxus include severe dyspnea, obesity, and positive pressure ventilator support.

Diagnosis

The electrocardiogram is often abnormal in acute pericarditis although the findings are nonspecific. Low voltage QRS amplitude may be seen as a result of pericardial fluid accumulation. Tachycardia and abnormalities of the ST segments, PR segments, and T waves may be present as well.

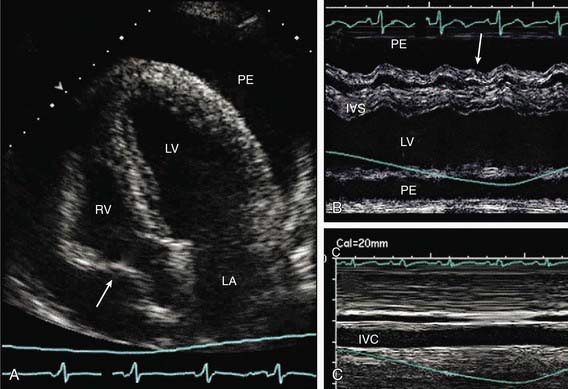

Although the chest x-ray findings in a patient with pericarditis without effusion are usually normal, in the presence of a significant effusion, cardiac enlargement will be seen and cardiac contour may be unusual (Erlenmeyer flask). Echocardiography is the most sensitive technique for identifying the size and location of a pericardial effusion. Compression and collapse of the right atrium and/or right ventricle are present with cardiac tamponade (Fig. 434-1). Abnormal diastolic filling parameters have also been described in cases of tamponade.

Figure 434-1 Echocardiographic images of large pericardial effusion with features of tamponade. A, Apical four-chamber view of LV, LA, and RV that shows large PE with diastolic right-atrial collapse (arrow). B, M-mode image with cursor placed through RV, IVS, and LV in parasternal long axis. The view shows circumferential PE with diastolic collapse of RV free wall (arrow) during expiration. C, M-mode image from subcostal window in same patient that shows IVC plethora without inspiratory collapse. IVC, inferior vena cava; IVS, interventricular septum; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; PE, pericardial effusion; RV, right ventricle.

(From Troughton RW, Asher CR, Klein AL: Pericarditis, Lancet 363:717–727, 2004.)

Differential Diagnosis

Chest pain similar to that present in pericarditis can occur with lung diseases, especially pleuritis, and with gastroesophageal reflux. Pain related to myocardial ischemia is usually more severe, more prolonged, and occurs with exercise, allowing distinction from pericarditis-induced pain. The presence of a pericardial effusion by echocardiography is virtually diagnostic of pericarditis.

Infectious Pericarditis

A number of viral agents are known to cause pericarditis, and the clinical course of the majority of these infections is mild and spontaneously resolving. The term acute benign pericarditis is synonymous for viral pericarditis. Agents identified as causing pericarditis include the enteroviruses, influenza, adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and parvovirus. As the course of this illness is usually benign, symptomatic treatment with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents is often sufficient. Patients with large effusions and tamponade may require pericardiocentesis. If the condition becomes chronic or relapsing, surgical pericardiectomy or creation of a pericardial window may be necessary.

Echocardiography is useful in differentiating pericarditis from myocarditis, the latter of which will show evidence of diminished myocardial contractility or valvular dysfunction. Pericarditis and myocarditis may occur together in some cases of viral infection.

Purulent pericarditis, often caused by bacterial infections, has become much less common with the advent of new immunizations for haemophilus and pneumococcal disease. Historically, purulent pericarditis was seen in association with severe pneumonias, epiglottitis, meningitis, or osteomyelitis. Patients with purulent pericarditis are acutely ill. Unless the infection is recognized and treated expeditiously, the course can be fulminant, leading to tamponade and death. Tuberculous pericarditis is rare in developed countries, but can be seen as a relatively common complication of HIV infection in regions where tuberculosis is endemic and access to anti-retroviral therapy is limited. Immune-complex mediated pericarditis is a rare complication that may result in a nonpurulent (sterile) effusion following systemic bacterial infections such as meningococcus or haemophilus.

Noninfectious Pericarditis

Systemic inflammatory diseases including autoimmune, rheumatologic, and connective tissue disorders may involve the pericardium and result in serous pericardial effusions. Pericardial inflammation may be a component of the type II hypersensitivity reaction seen in patients with acute rheumatic fever. It is often associated with rheumatic valvulitis and responds quickly to antiinflammatory agents including steroids. Tamponade is very uncommon (Chapters 176.1 and 432).

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, usually systemic onset disease, can manifest with pericarditis. Differentiating rheumatoid pericardial inflammation from that seen with systemic lupus erythematosus is difficult and requires careful rheumatologic evaluation. Aspirin and/or corticosteroids can result in rapid resolution of a pericardial effusion but may be needed on a chronic basis to prevent relapse.

Patients with chronic renal failure or hypothyroidism may have pericardial effusions and should be carefully screened with physical exam, and, if indicated, imaging studies, during the course of their illness should clinical suspicion arise.

Especially common in referral centers with hematology/oncology units is the presence of pericardial effusion related to neoplastic disease. Conditions resulting in effusion include Hodgkin disease, lymphomas, and leukemia. Radiation therapy directed to the mediastinum of patients with malignancy can result in pericarditis and later constrictive pericardial disease.

The postpericardiotomy syndrome occurs in patients having undergone cardiac surgery and is characterized by fever, lethargy, anorexia, irritability, and chest/abdominal discomfort beginning 7-14 days postoperatively. There can be associated pleural effusions and serologic evidence of elevated antiheart antibodies. Postpericardiotomy syndrome is effectively treated with aspirin, nonsteroidal inflammatory agents, and in severe cases, corticosteroids. Pericardial drainage is necessary in those patients with cardiac tamponade.

434.2 Constrictive Pericarditis

Robert Spicer and Stephanie Ware

Rarely, chronic pericardial inflammation can result in fibrosis, calcification, and thickening of the pericardium. Pericardial scarring may lead to impaired cardiac distensibility and filling and is termed constrictive pericarditis. Constrictive pericarditis can occur following recurrent or chronic pericarditis, cardiac surgery, or radiation to the mediastinum as a treatment for malignancies, most commonly Hodgkin disease or lymphoma.

Clinical manifestations of systemic venous hypertension predominate in cases of restrictive pericarditis. Jugular venous distension, peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, and ascites may precede signs of more significant cardiac compromise such as tachycardia, hypotension, and pulsus paradoxus. A pericardial knock, rub, and distant heart sounds might be present on auscultation. Abnormalities of liver function tests, hypoalbuminemia, hypoproteinemia, and lymphopenia may be present. On occasion, x-rays of the chest demonstrate calcifications of the pericardium.

Constrictive pericarditis may be difficult to distinguish clinically from restrictive cardiomyopathy as both conditions result in impaired myocardial filling (Chapter 433.3). Echocardiography may be helpful in distinguishing constrictive pericardial disease from restrictive cardiomyopathy, but magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomographic imaging are more sensitive in detecting abnormalities of the pericardium. In rare instances, exploratory thoracotomy with direct examination of the pericardium may be required to confirm the diagnosis.

Although acute pericardial constriction is reported to respond to antiinflammatory agents, the more typical chronic constrictive pericarditis will respond only to surgical pericardiectomy with extensive resection of the pericardium.

Dal-Bianco JP, Sengupta PP, Mookadam F, et al. Role of echocardiography in the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:24-33. quiz 103–104

Demmler GJ. Infectious pericarditis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:165-166.

Karlberg N, Jalanko H, Perheentupa J, et al. Mulibrey nanism: clinical features and diagnostic criteria. J Med Genet. 2004;41:92-98.

Kuhn B, Peters J, Marks GR, et al. Etiology, management, and outcome of pediatric pericardial effusions. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;29:90-94.

Little WC, Freeman GL. Pericardial disease. Circulation. 2006;113:1622-1632.

Parikh SV, Memon N, Echols M, et al. Purulent pericarditis. Medicine. 2009;88:52-65.

Roy CL, Minor MA, Brookhart MA, et al. Does this patient with a pericardial effusion have cardiac tamponade? JAMA. 297, 2007. 1810–1181

Yeh T-T, Yang Y-H, Lin Y-T, et al. Cardiopulmonary involvement in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus: a 20-year retrospective analysis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2007;40:525-531.