Chapter 5 Conjunctiva

Introduction

Anatomy

The conjunctiva is a transparent mucous membrane lining the inner surface of the eyelids and the surface of the globe as far as the limbus. It is richly vascular, supplied by the anterior ciliary and palpebral arteries. There is a dense lymphatic network, with drainage to the preauricular and submandibular nodes corresponding to that of the eyelids. It has a key protective role, mediating both passive and active immunity. Anatomically, it is subdivided into the following:

Histology

Clinical features of conjunctival inflammation

Symptoms

Non-specific symptoms include lacrimation, grittiness, stinging and burning. Itching is the hallmark of allergic disease, although it may also occur to a lesser extent in blepharitis and dry eye. Significant pain, photophobia or a marked foreign body sensation suggest corneal involvement.

Discharge

Conjunctival reaction

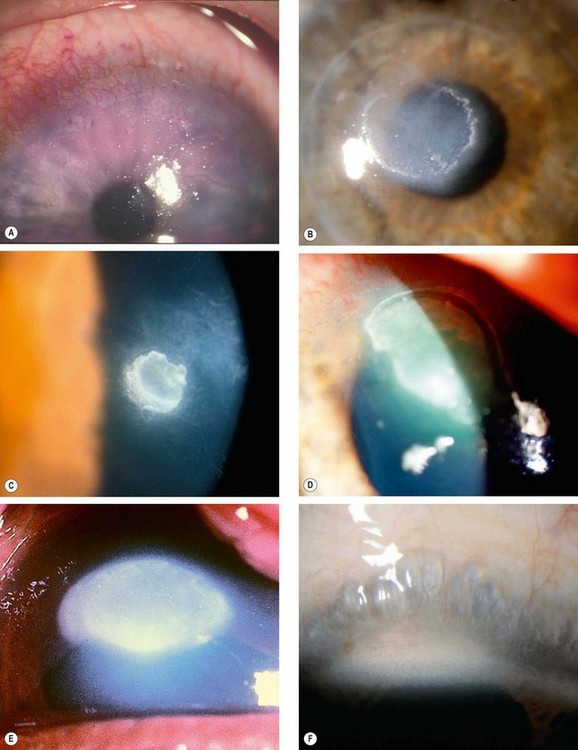

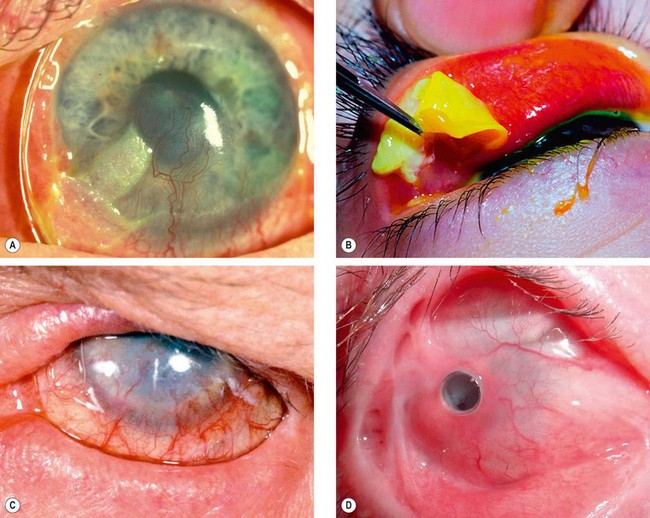

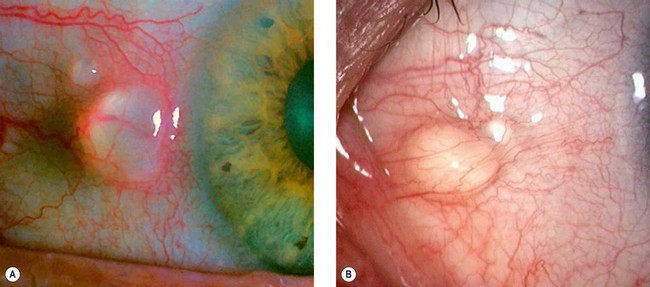

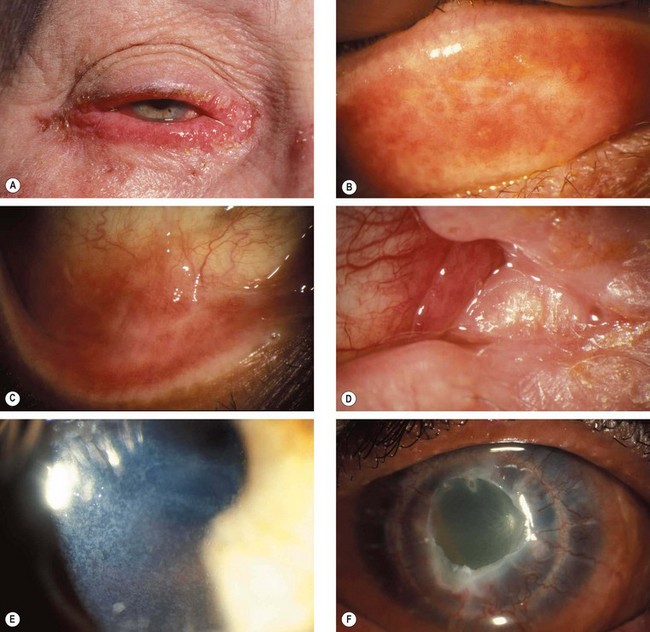

Fig. 5.2 Signs of conjunctival inflammation. (A) Injection; (B) haemorrhages; (C) chemosis; (D) pseudomembrane; (E) infiltration; (F) subconjunctival scarring

(Courtesy of P Saine – fig. A; S Tuft – fig. B; M Jager – fig. F)

The distinction between a true and a pseudomembrane is rarely clinically helpful and both can leave scarring following resolution.

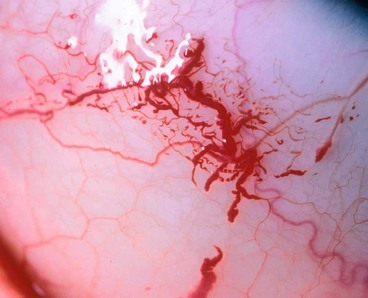

Fig. 5.3 (A) Conjunctival follicles; (B) histology of a follicle shows two subepithelial germinal centres with immature lymphocytes centrally and mature cells peripherally; (C) conjunctival macropapillae; (D) histology of a papilla shows folds of hyperplastic conjunctival epithelium with a fibrovascular core and subepithelial stromal infiltration with inflammatory cells

(Courtesy of S Tuft – figs A and C; J Harry – figs B and D)

Bacterial conjunctivitis

Acute bacterial conjunctivitis

Acute bacterial conjunctivitis is a common and usually self-limiting condition caused by direct eye contact with infected secretions. The most common isolates are S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, H. influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis. A minority of cases, usually severe, are caused by the sexually transmitted organism Neisseria gonorrhoeae, which can readily invade the intact corneal epithelium. Meningococcal (Neisseria meningitidis) conjunctivitis is rare, and usually affects children.

Diagnosis

Fig. 5.4 Bacterial conjunctivitis. (A) Eyelid oedema and erythema in severe infection; (B) diffuse conjunctival injection involving the tarsal and forniceal conjunctiva; (C) mucopurulent discharge; (D) profuse purulent discharge; (E) superior corneal ulceration; (F) Gram stain shows kidney-shaped diplococcic

(Courtesy of S Tuft – fig. E; S Lewellen – fig. F)

Treatment

About 60% of cases resolve within 5 days without treatment.

Adult chlamydial conjunctivitis

Pathogenesis

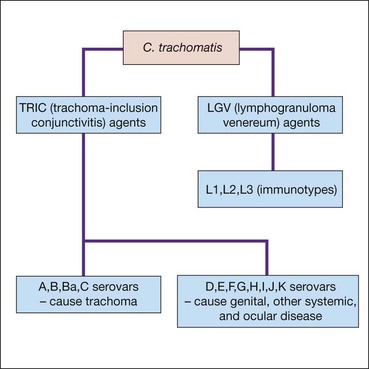

Chlamydia trachomatis (Fig. 5.5) is a species of Chlamydiae, a phylum of bacteria that cannot replicate extracellularly and hence depend on host cells. They exist in two principal forms: (a) a robust infective extracellular ‘elementary body’ and (b) a fragile intracellular replicating ‘reticular body’. Adult chlamydial (inclusion) conjunctivitis is an oculogenital infection usually caused by serovars (serological variants) D-K of C. trachomatis, and affects 5–20% of sexually active young adults in western countries. Transmission is by autoinoculation from genital secretions although eye-to-eye spread probably accounts for about 10% of cases. The incubation period is about 1 week.

Urogenital infection

Diagnosis

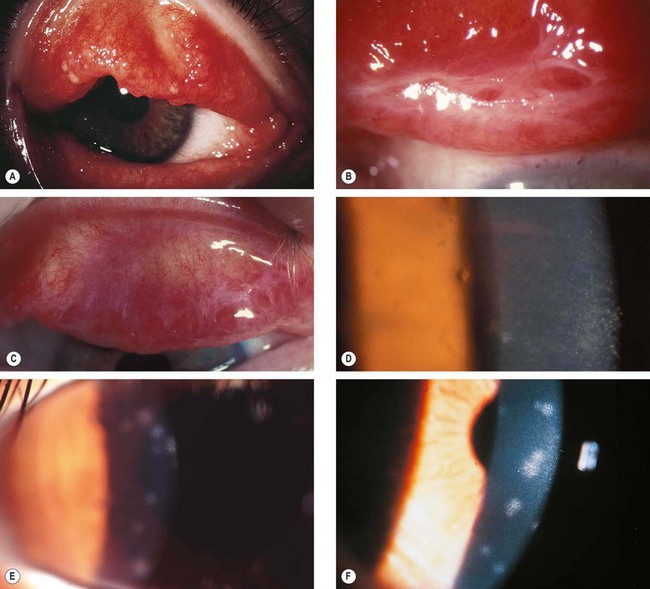

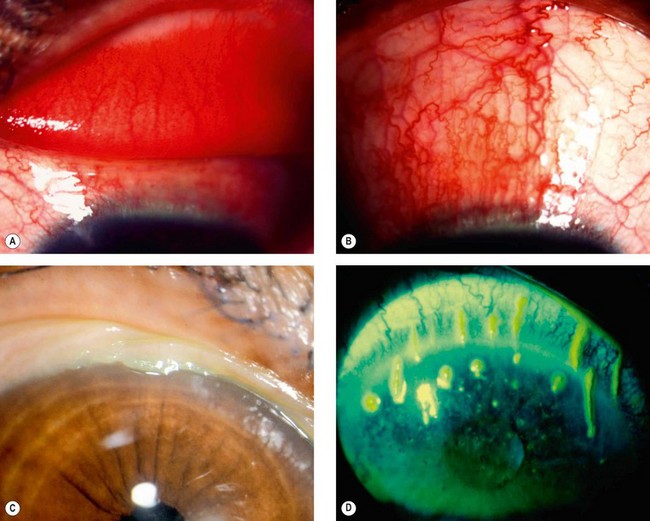

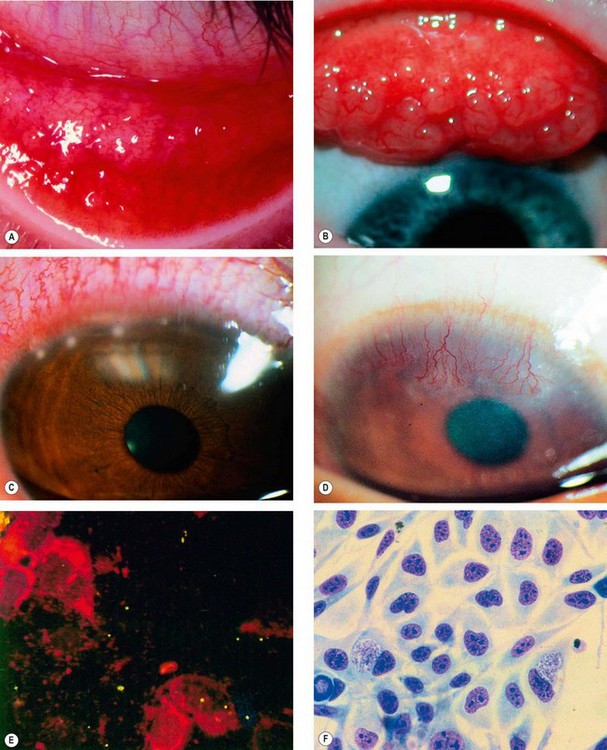

Fig. 5.6 Adult chlamydial conjunctivitis. (A) Large forniceal follicles; (B) superior tarsal follicles; (C) peripheral corneal infiltrates; (D) superior pannus; (E) elementary bodies seen on direct immunofluorescence; (F) McCoy cell culture shows glycogen-positive inclusion bodies

(Courtesy of J Harry and G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology Butterworth-Heinemann 2001 – fig. E)

Treatment

It is important to be aware that symptoms commonly take weeks to settle, and follicles and corneal infiltrates can take months to resolve due to a prolonged hypersensitivity response to chlamydial antigen.

Trachoma

Pathogenesis

Trachoma is the leading cause of preventable irreversible blindness in the world. It is related to poverty, overcrowding, and poor hygiene, the morbidity being a consequence of the establishment of re-infection cycles within communities. Whereas an isolated episode of trachomatous conjunctivitis may be relatively innocuous, recurrent infection elicits a chronic immune response consisting of a cell-mediated delayed hypersensitivity (type IV) reaction to the intermittent presence of chlamydial antigen and can lead to loss of sight. The family childcare group is the most important re-infection reservoir, and consequently young children are particularly vulnerable. The fly is an important vector, but there may be direct transmission from eye or nasal discharge. Trachoma is associated principally with infection by serovars A, B, Ba, and C of Chlamydia trachomatis, but the serovars D-K conventionally associated with adult inclusion conjunctivitis, and other species of the Chlamydiaceae family such as Chlamydophila psittaci and Chlamydophila pneumoniae have also been implicated.

Diagnosis

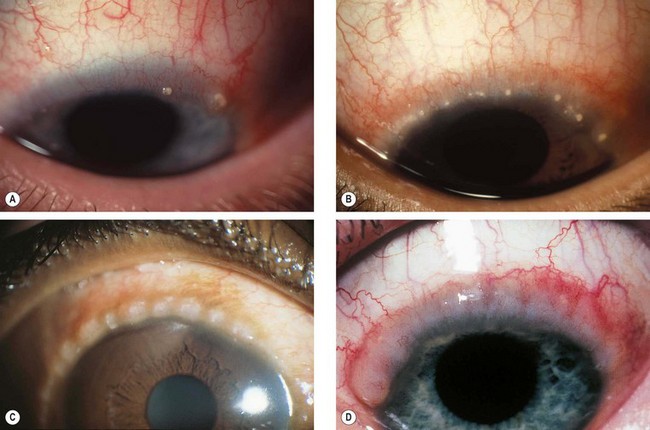

The features of trachoma are divided into the ‘active’ inflammatory stage and the ‘cicatricial’ chronic stage, with considerable overlap.

Fig. 5.7 Trachoma. (A) Mixed follicular-papillary conjunctivitis; (B) severe pannus; (C) linear scars; (D) Arlt line; (E) Herbert pits; (F) corneal scarring and vascularization, and cicatricial entropion

(Courtesy of R Bates – fig. E; C Barry – fig. F)

Table 5.1 WHO grading of trachoma

|

TF = trachomatous inflammation (follicular): five or more follicles (>0.5 mm) on the superior tarsus

|

Management

The SAFE strategy for trachoma management supported by the WHO and other agencies encompasses Surgery for trichiasis, Antibiotics for active disease, Facial hygiene, and Environmental improvement.

Neonatal conjunctivitis

Neonatal conjunctivitis (ophthalmia neonatorum) is defined as conjunctival inflammation developing within the first month of life. It is the most common infection of any kind in neonates, occurring in up to 10%. It is identified as a specific entity distinct from conjunctivitis in older infants because it is often the result of infection transmitted from mother to infant during delivery. Notification of neonatal conjunctivitis to the local public health authority is a statutory requirement in many countries.

Causes

Diagnosis

Treatment

Viral conjunctivitis

Adenoviral conjunctivitis

Pathogenesis

Viral conjunctivitis is most frequently caused by an adenovirus (a non-enveloped double-stranded DNA virus). Infection may be sporadic or it may occur in epidemics in workplaces (including hospitals), schools and swimming pools. The spread of this highly contagious disease is facilitated by the ability of viral particles to survive on dry surfaces for weeks, and by the fact that viral shedding may occur for many days before clinical features are apparent. Transmission is generally by contact with respiratory or ocular secretions, including via fomites such as contaminated towels.

Presentation

The spectrum of viral conjunctivitis varies from mild subclinical disease to severe inflammation with significant morbidity. There will often be a history of a close contact with acute conjunctivitis.

Signs

Differential diagnosis

Management

Spontaneous resolution usually occurs within 2–3 weeks.

Molluscum contagiosum conjunctivitis

Pathogenesis

Molluscum contagiosum is a skin infection caused by a human specific double-stranded DNA poxvirus which typically affects otherwise healthy children, with a peak incidence between the ages of 2 and 4 years. Transmission is by contact, with subsequent autoinoculation. The eyelash line should be examined carefully in patients with chronic conjunctivitis so as not to overlook a molluscum lesion.

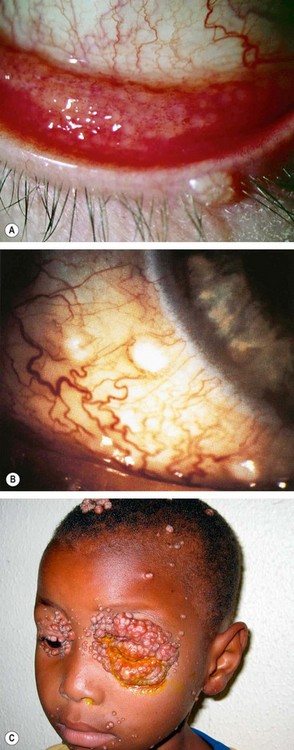

Diagnosis

Fig. 5.10 (A) Follicular conjunctivitis associated with a molluscum eyelid lesion; (B) molluscum lesions on the bulbar conjunctiva; (C) extensive confluent molluscum lesions in an HIV positive patient

(Courtesy of JH Krachmer; MJ Mannis and EJ Holland, from Cornea, Mosby 2005 – fig. B; D Smit – fig. C)

Allergic conjunctivitis

Atopy is a genetically determined predisposition to hypersensitivity reactions upon exposure to specific environmental antigens. Clinical manifestations include the various forms of allergic conjunctivitis, as well as hay fever (seasonal allergic rhinitis), asthma and eczema. Allergic conjunctivitis is a Type I (immediate) hypersensitivity reaction, mediated by degranulation of mast cells in response to the action of IgE; there is evidence of an element of Type IV hypersensitivity in at least some forms.

Acute allergic conjunctivitis

Acute allergic conjunctivitis is a common condition caused by an acute conjunctival reaction to an environmental allergen, usually pollen. It is typically seen in younger children after playing outside in spring or summer.

Seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis

Seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis are subacute conditions that differ from each other by the timing of exacerbations because of different stimulating allergens in each.

Diagnosis

Treatment

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis

Pathogenesis

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) is a recurrent bilateral disorder in which both IgE- and cell-mediated immune mechanisms play important roles. It primarily affects boys and onset is generally from about the age of 5 years onwards (mean age 7 years). Ninety-five per cent of cases remit by the late teens although many of the remainder develop atopic keratoconjunctivitis. VKC is rare in temperate regions but relatively common in warm dry climates such as the Mediterranean, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East. In temperate regions over 90% of patients have other atopic conditions such as asthma and eczema and two-thirds of cases have a family history of atopy. VKC often occurs on a seasonal basis, with a peak incidence over late spring and summer, although there may be mild perennial symptoms.

Classification

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is clinical and investigations are generally not indicated.

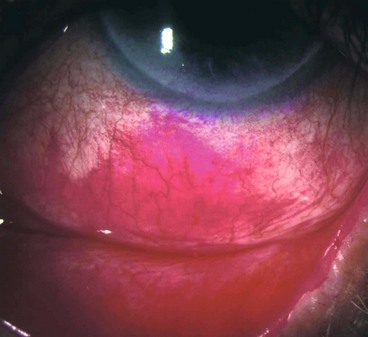

Fig. 5.12 Palpebral vernal disease. (A) Diffuse papillary hypertrophy; (B) macropapillae; (C) giant papillae and mucus; (D) relatively inactive disease

(Courtesy of S Tuft – figs B and D)

Atopic keratoconjunctivitis

Pathogenesis

AKC is a rare bilateral disease that typically develops in adulthood (peak incidence 30–50 years) following a long history of eczema. Asthma is also extremely common in these patients. About 5% have suffered from childhood VKC. There is little or no gender preponderance. AKC tends to be chronic and unremitting with a relatively low expectation of eventual resolution, and is associated with significant visual morbidity. Whereas VKC is more frequently seasonal, AKC tends to be perennial, although it is often worse in the winter. Patients are sensitive to a wide range of airborne environmental allergens.

Diagnosis

The distinction between AKC and VKC is clinical.

Fig. 5.15 Atopic disease. (A) Severe eyelid involvement; (B) infiltration and scarring of the tarsal conjunctiva; (C) forniceal shortening; (D) keratinization of the caruncle; (E) punctate epithelial erosions; (F) persistent epithelial defect and peripheral corneal vascularization

(Courtesy of S Tuft)

Treatment of VKC and AKC

The management of VKC does not differ substantially from that of AKC, although the latter is generally less responsive and requires more intensive and prolonged treatment.

General measures

Local treatment

Systemic treatment

Surgery

Giant (mechanically-induced) papillary conjunctivitis

Pathogenesis

Mechanically-induced papillary conjunctivitis, the severe form of which is known as giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC), can occur secondary to a variety of mechanical stimuli of the tarsal conjunctiva. It is most frequently seen with contact lens (CL) wear, when it is termed contact lens-associated papillary conjunctivitis (CLPC). The risk is increased by the build-up of proteinaceous deposits and cellular debris on the contact lens surface (Fig. 5.16). Ocular prostheses (Fig. 5.17), exposed sutures and scleral buckles, corneal surface irregularity and filtering blebs can all be responsible. A related phenomenon is the so-called ‘mucus fishing syndrome’, when, in a variety of underlying anterior segment disorders, patients develop or exacerbate a chronic papillary reaction due to repetitive manual removal of mucus.

Diagnosis

Treatment

Other causes of conjunctival papillae should be excluded, as well as CL intolerance due to other causes such as solutions and dry eyes.

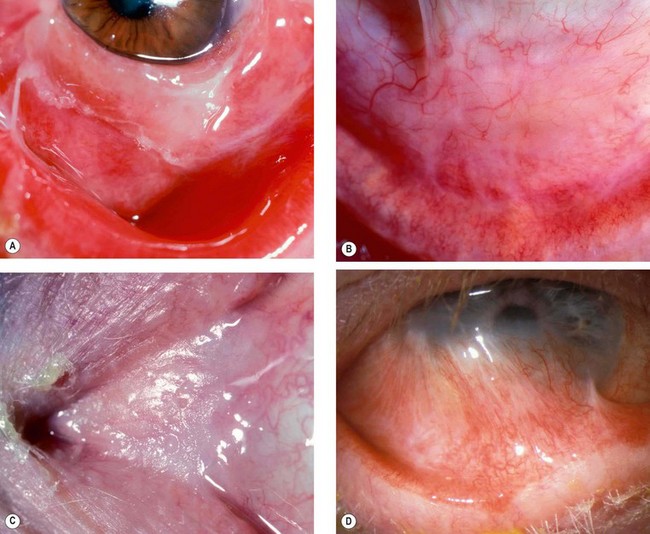

Conjunctivitis in blistering mucocutaneous disease

Mucous membrane pemphigoid

Definition

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP), also known as cicatricial pemphigoid (CP), comprises a group of chronic autoimmune mucocutaneous blistering diseases characterized by linear antibody and complement deposition at epithelial basement membranes. A wide range of epithelial tissues can be involved including the skin and mucous membranes of the mouth, nasopharynx, upper airways, genitalia, and upper and lower gastrointestinal tract, as well as the conjunctiva. Particular clinical forms of MMP tend preferentially to involve specific target tissues or body regions such as bullous pemphigoid (BP) that shows a predilection for skin, although frequently also affects the mouth and other tissues. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP) involves the conjunctiva in the majority of cases and causes progressive scarring (cicatrization). The disease typically presents in old age and affects females more commonly than males by a 2 : 1 ratio. Other causes of cicatrizing conjunctivitis are set out in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2 Causes of conjunctival cicatrization

Pathogenesis

An unknown trigger (possibly contact with a particular micro-organism) in genetically predisposed individuals leads to a Type II hypersensitivity response with antibodies binding at the basement membrane zone (BMZ), the activation of complement and recruitment of inflammatory cells. A characteristic of the acute phase of the inflammatory process is localized separation of the epidermis from the dermis at the BMZ. The release of cytokines causes fibroblast activation with consequent progression to scarring. Different clinical forms of MMP tend to be associated with differing target antigens. In bullous pemphigoid, it is one or more hemidesmosomal glycoproteins, and in many cases of OCP, a component of an integrin (a protein mediating cell–cell and cell–matrix interaction) is responsible.

Ocular features

Systemic features

Systemic treatment

Local treatment

Reconstructive surgery

Reconstructive surgery, preferably under systemic steroid cover, should be considered when active disease is controlled.

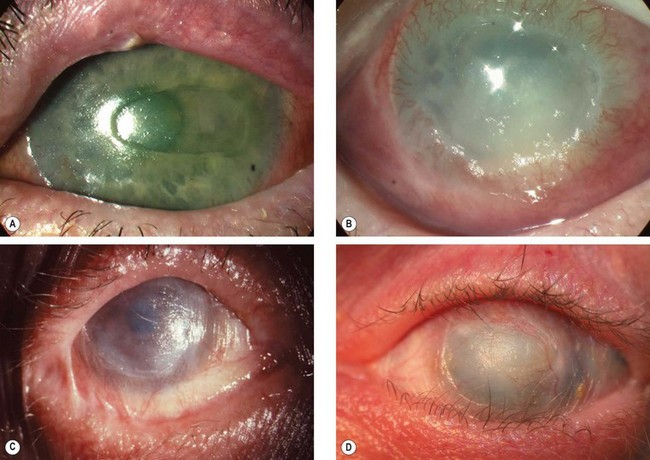

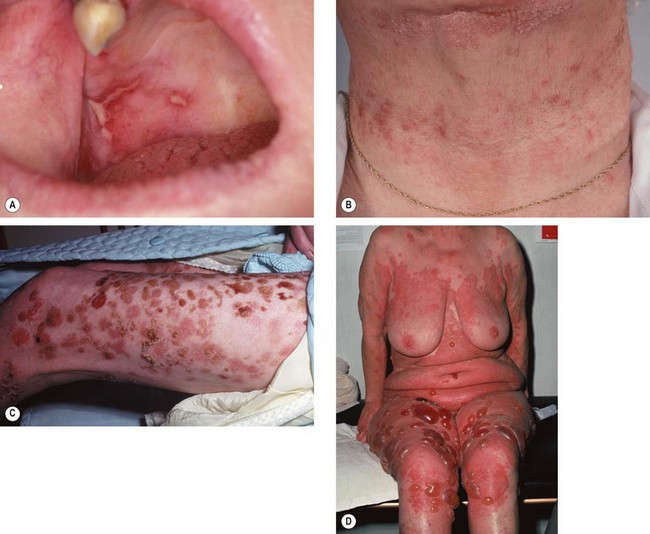

Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell syndrome)

Definition

Previously, the terms ‘Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS)’ and ‘erythema multiforme major’ were often used synonymously. However, it is now believed that erythema multiforme (without the ‘major’) is a distinct disease, milder and recurrent, with somewhat dissimilar clinical features and a tendency for different precipitating factors (erythema multiforme predominantly infections, Stevens–Johnson predominantly drugs). ‘Toxic epidermal necrolysis’ (TEN – Lyell syndrome) is a severe variant of SJS. Classically, SJS/TEN patients tend to be young adults, though other age groups, including children and the elderly, may be affected. An SJS-type presentation is more common in males than females, with the reverse probably true for TEN.

Pathogenesis

It is thought that a cell-mediated delayed hypersensitivity immune reaction is involved, either directly to drugs or to epithelial cell antigens modified by drug exposure. A wide range of drugs have been incriminated including antibiotics (especially sulfonamides and trimethoprim), analgesics, cough and cold remedies, cocaine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, anticonvulsants and allopurinol.

Micro-organisms include Mycoplasma pneumoniae and herpes simplex virus (HSV). Because symptoms often take 3 weeks to develop after exposure, in over 50% of cases the precipitating cause cannot be identified with certainty. Particular HLA alleles have been linked to a greater likelihood of developing SJS/TEN on exposure to particular drug groups.

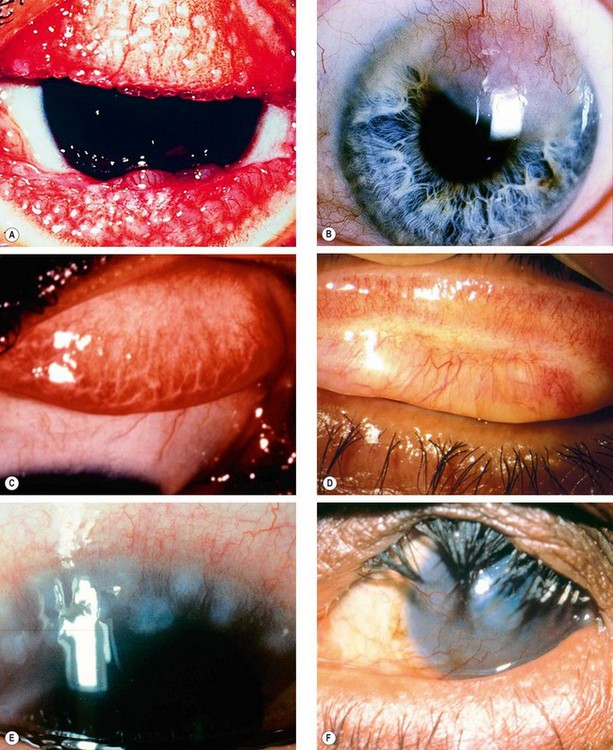

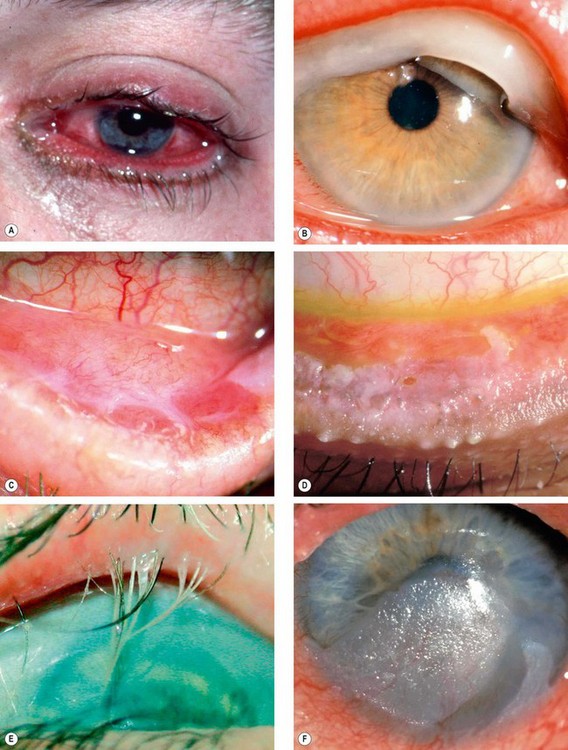

Ocular features

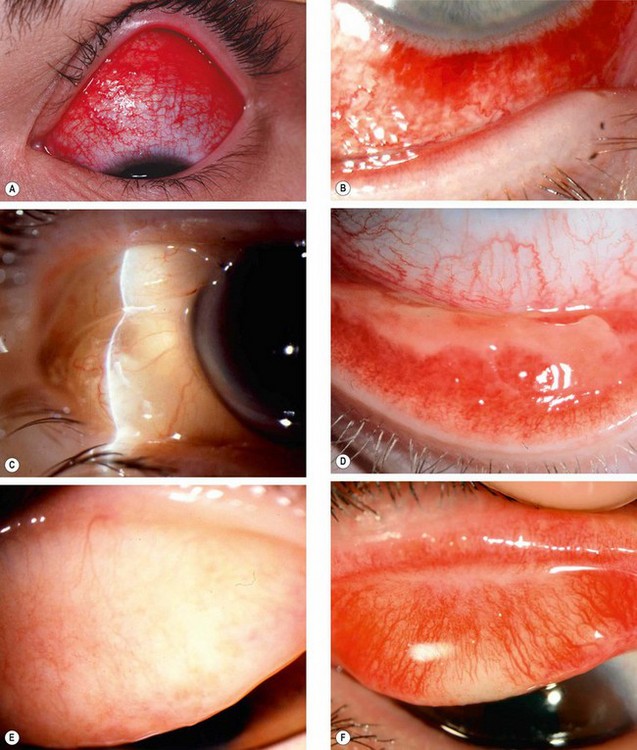

Fig. 5.21 Ocular features in Stevens–Johnson syndrome. (A) Acute conjunctivitis and haemorrhagic lid crusting; (B) pseudomembrane formation; (C) conjunctival keratinization; (D) keratinization and severe posterior lid margin disease; (E) metaplastic lashes; (F) corneal keratinization

(Courtesy of S Tuft – figs D and F)

Systemic features

Systemic treatment

Ocular treatment

Miscellaneous conjunctivitis

Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis

Definition

Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis (SLK) is an uncommon chronic disease of the superior limbus and the superior bulbar and tarsal conjunctiva. It typically affects both eyes of middle-aged women, approximately 50% of whom have abnormal thyroid function (usually hyperthyroidism); approximately 3% of patients with thyroid eye disease have SLK. The condition is probably under-diagnosed because symptoms are typically more severe than signs. The course can be prolonged over years although remission eventually occurs spontaneously. There are similarities to mechanically-induced papillary conjunctivitis, and a comparable clinical picture has been described with contact lens wear and following upper lid surgery or trauma.

Pathogenesis

SLK is believed to be the result of blink-related trauma between the upper lid and the superior bulbar conjunctiva, precipitated in many cases by tear film insufficiency and an excess of lax conjunctival tissue. With increased conjunctival movement there is mechanical damage to the tarsal and bulbar conjunctival surfaces, the resultant inflammatory response leading to increasing conjunctival oedema and redundancy, with the creation of a self-perpetuating cycle.

Diagnosis

Treatment

Conservative measures should be tried initially.

Ligneous conjunctivitis

Definition

Ligneous conjunctivitis is a very rare disorder characterized by recurrent, often bilateral fibrin-rich pseudomembranous lesions of wood-like consistency that develop mainly on the tarsal conjunctiva. It is generally a systemic condition which may involve the periodontal tissue, the upper and lower respiratory tract, kidneys, middle ear and female genitalia. It can be sight-threatening, and death can occasionally occur from pulmonary involvement.

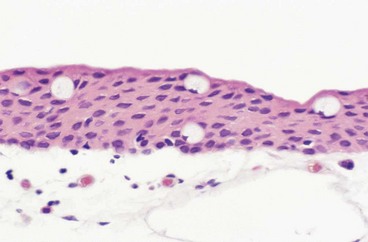

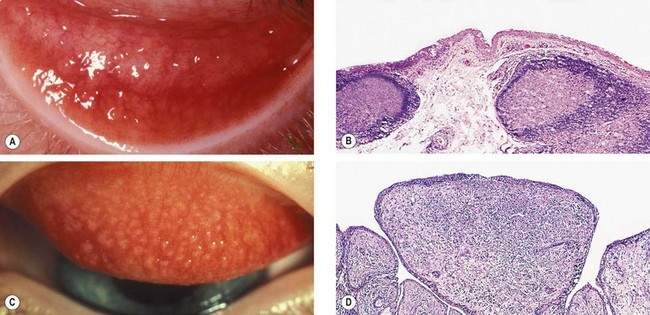

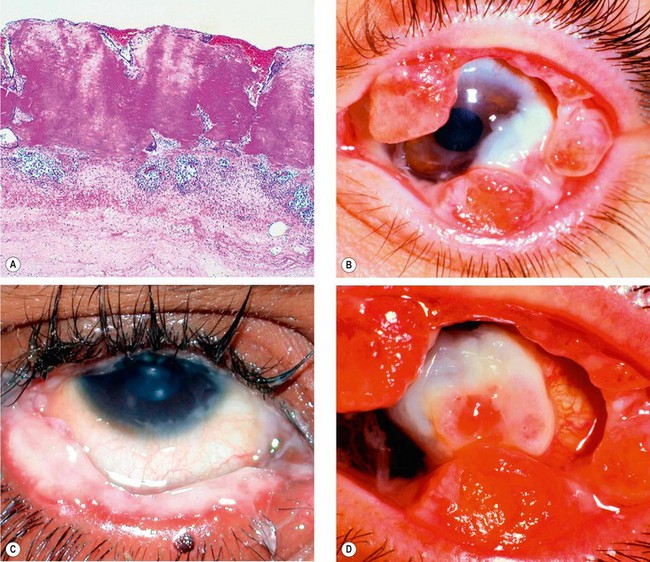

Pathogenesis

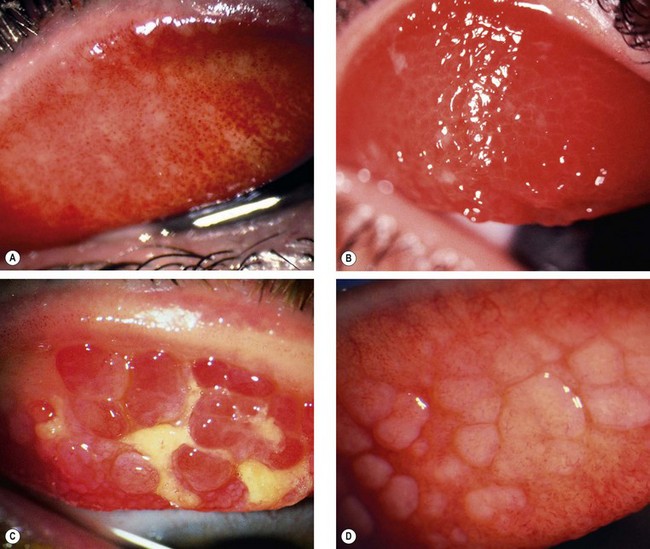

It is thought that in susceptible patients patterns of damage repair are abnormal, notably a failure of normal clearance of products of the acute stages of the healing process. A deficiency in plasmin-mediated fibrinolysis may be a key common factor in many patients. Episodes may be triggered by relatively minor trauma, or by systemic events such as fever and antifibrinolytic therapy. Histology shows amorphous subepithelial deposits of eosinophilic material consisting predominantly of fibrin (Fig. 5.25A).

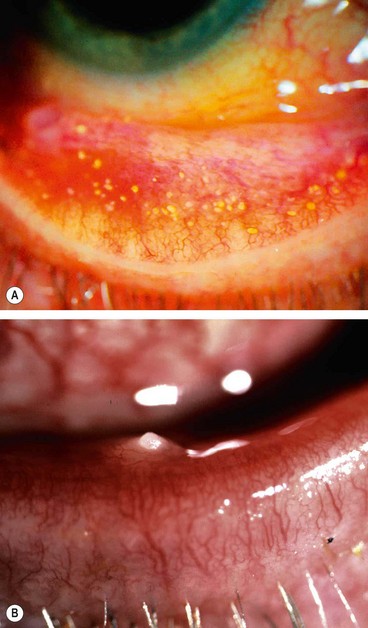

Fig. 5.25 Ligneous conjunctivitis. (A) Histology shows eosinophilic fibrinous coagulum on the conjunctival surface; (B) multiple ligneous lesions; (C) thick overlying mucus; (D) end-stage disease with corneal destruction

(Courtesy of J Harry and G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2001 – fig. A; JH Krachmer, MJ Mannis and EJ Holland, from Cornea, Mosby 2005 – figs B and D; R Fogla – fig. C)

Diagnosis

Treatment

Treatment tends to be unsatisfactory and spontaneous resolution is rare. It is important to discontinue any antifibrinolytic drugs.

Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome

Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome or conjunctivitis is a rare condition consisting of chronic low-grade fever, unilateral granulomatous conjunctivitis with surrounding follicles (Fig. 5.26) and ipsilateral regional (preauricular) lymphadenopathy. It is virtually synonymous with cat-scratch disease (caused by Bartonella henselae), although several other causes have been implicated, including tularaemia, insect hairs (ophthalmia nodosum), T. pallidum, sporotrichosis, tuberculosis, and acute Chlamydia trachomatis infection.

Factitious conjunctivitis

Self-injury (factitious keratoconjunctivitis) is most often intentional although can also occur inadvertently, as in mucous fishing syndrome and removal of contact lenses. Damage may be the result of either mechanical abrasion or perforation, or of the instillation of irritant but readily accessible household substances, such as soap. Occasionally over-instillation of prescribed ocular medication is responsible.

Diagnosis

Degenerations

Pingueculum

A pingueculum is an extremely common, innocuous, usually bilateral and asymptomatic ‘elastotic’ degeneration of the collagen fibres of conjunctival stroma. The cause is believed to be actinic damage, similar to the aetiology of pterygium (see below).

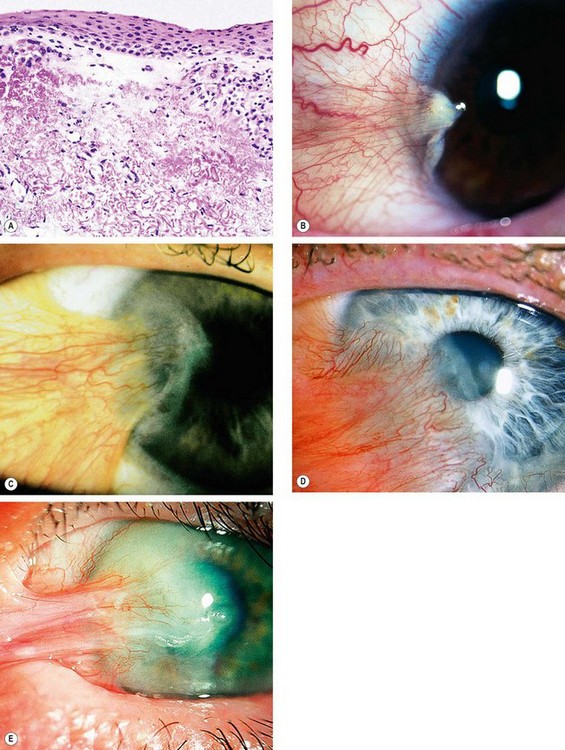

Pterygium

A pterygium is a triangular fibrovascular subepithelial ingrowth of degenerative bulbar conjunctival tissue over the limbus onto the cornea. It typically develops in patients who have been living in hot climates and, as with pinguecula, may represent a response to ultraviolet exposure and possibly to other factors such as chronic surface dryness. A pterygium is histologically similar to a pingueculum and shows elastotic degenerative changes in vascularized subepithelial stromal collagen (Fig. 5.29A).

Fig. 5.29 Pterygium. (A) Histology shows collagenous degenerative changes in vascularized subepithelial stroma; (B) type 1; (C) type 2; (D) type 3; (E) pseudopterygium caused by a chemical burn

(Courtesy of J Harry – fig. A)

Clinical features

Treatment

Concretions

Concretions are extremely common and are usually associated with aging, although they can also form in patients with chronic conjunctival inflammation such as trachoma.

Conjunctivochalasis

Conjunctivochalasis is probably a normal ageing change that may be exacerbated by posterior lid margin disease. Mechanical stress on the conjunctiva precipitated by dry eye is a potential initiating mechanism.