Chapter 8 Episclera and Sclera

Anatomy

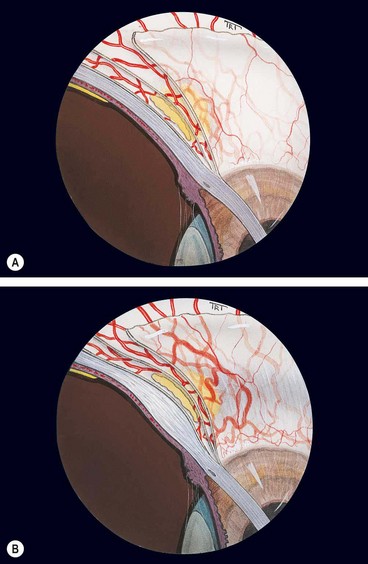

The scleral stroma is composed of collagen bundles of varying size and shape that are not as uniformly orientated as in the cornea. The inner layer of the sclera (lamina fusca) blends with the suprachoroidal and supraciliary lamellae of the uveal tract. Anteriorly the episclera consists of a dense, vascular connective tissue which lies between the superficial scleral stroma and Tenon capsule. The three vascular layers that cover the anterior sclera are as follows:

Episcleritis

Episcleritis is a common, benign, usually idiopathic, recurrent and frequently bilateral condition. It is usually self-limiting and an attack typically lasts a few days.

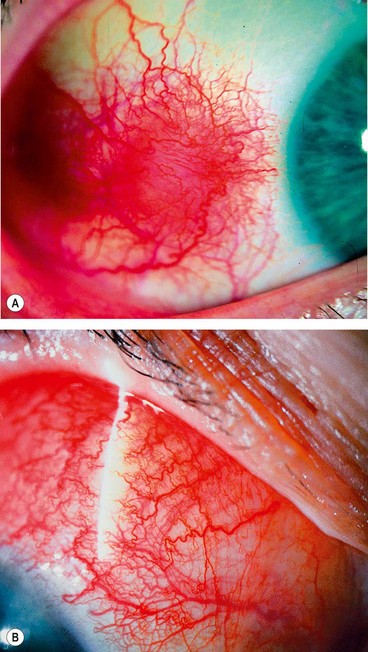

Simple episcleritis

Simple episcleritis accounts for three-quarters of all cases and predominantly affects females. It has a great tendency to recur either in the same eye, or sometimes both together. The attacks become less frequent and after many years disappear completely.

Nodular episcleritis

Nodular episcleritis also tends to affect young females but has a less acute onset and a more prolonged course than the simple variety.

Immune-mediated scleritis

Scleritis is an uncommon condition characterized by oedema and cellular infiltration of the entire thickness of the sclera. It is much less common than episcleritis and covers a spectrum ranging in severity from trivial self-limiting episodes to a necrotizing disease that may involve adjacent tissues and threaten vision.

The classification shown in Table 8.1 not only facilitates communication regarding the clinical presentation, but also has prognostic significance since patients presenting with one form will usually suffer recurrences of the same type of the disease, with less than 10% progressing to more aggressive disease.

Table 8.1 Classification of immune-mediated scleritis

| Anterior |

Anterior non-necrotizing scleritis

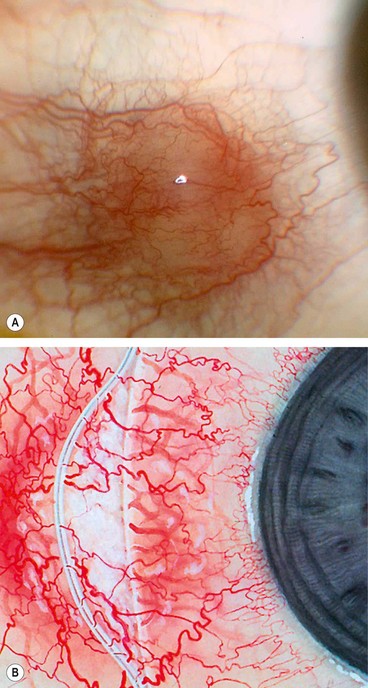

Diffuse

Diffuse disease is slightly more common in females and usually presents in the 5th decade.

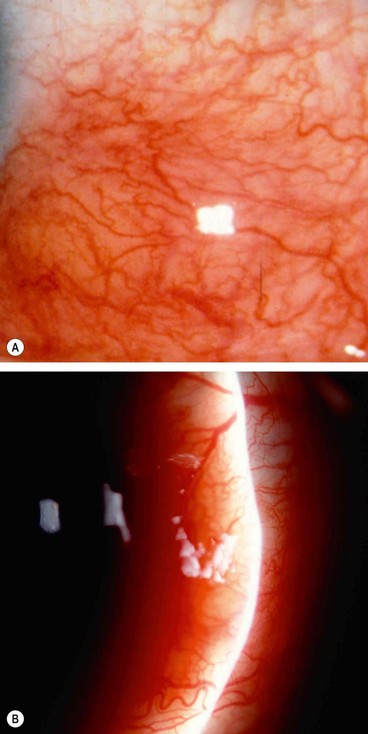

The redness may be generalized (Fig. 8.4A) or localized to one quadrant. If confined to the areas under the upper eyelid the diagnosis may be missed if the eyelid is not elevated.

Nodular

The incidence of nodular and diffuse anterior scleritis is the same but a disproportionately large number of those with nodular disease have had a previous attack of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. The age of onset is similar to that of diffuse scleritis.

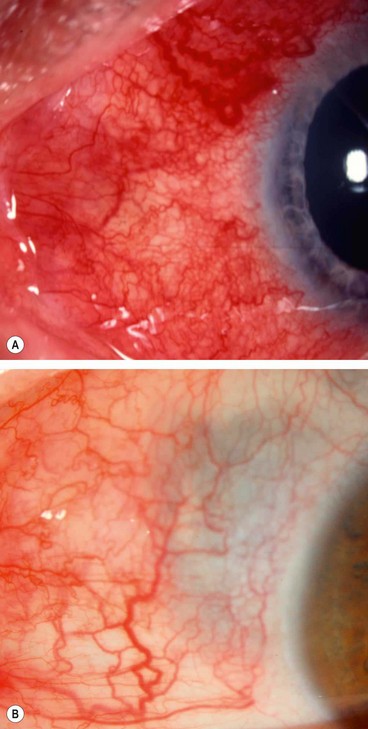

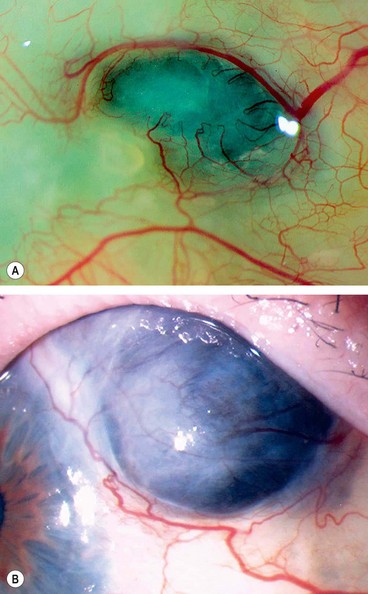

Anterior necrotizing scleritis with inflammation

Necrotizing disease is the aggressive form of scleritis. The age at onset is later than that of non-necrotizing scleritis, averaging 60 years. The condition is bilateral in 60% of patients and unless appropriately treated, especially in its early stages, it may result in severe visual morbidity and sometimes loss of the eye.

Clinical features

Investigations

Complications

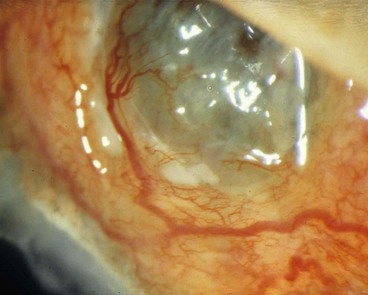

Scleromalacia perforans

Scleromalacia perforans is a specific type of necrotizing scleritis without inflammation that typically affects elderly women with longstanding rheumatoid arthritis. The use of the word ‘perforans’ is unfortunate because perforation of the globe is extremely rare as the integrity of the globe is maintained by a thin, but complete, layer of fibrous tissue.

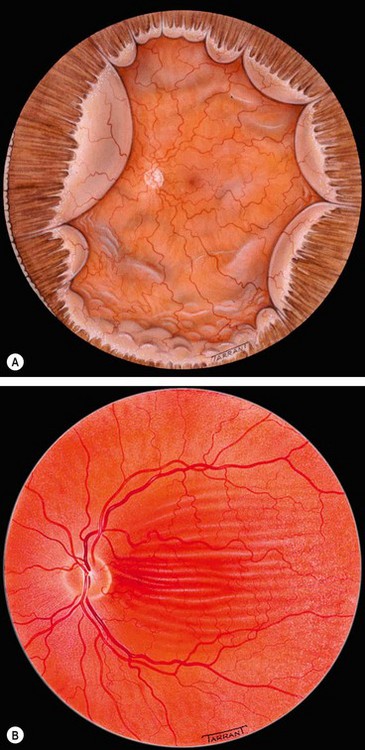

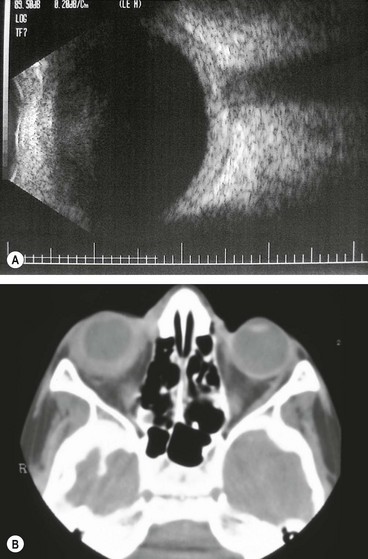

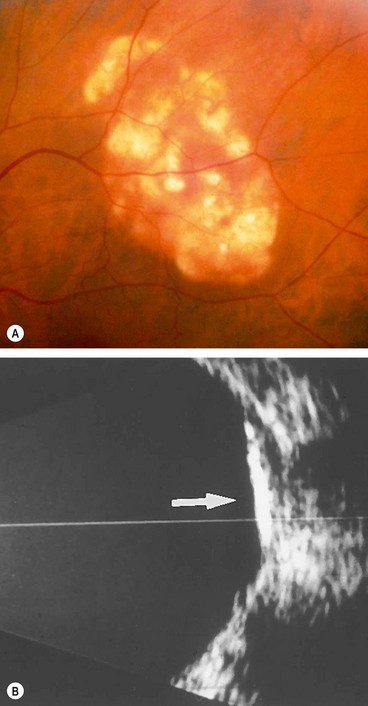

Posterior scleritis

Posterior scleritis is a serious, potentially blinding condition, which is often misdiagnosed and treated very late. The age at onset is often under the age of 40 years. The disease is bilateral in 35% of cases. It is important to remember that the inflammatory changes seen in posterior and anterior scleral disease are identical and can arise in both segments simultaneously or separately. The presence of anterior scleritis is a great help if posterior scleritis is suspected but it only occurs in a minority of cases. Patients with posterior scleritis can go blind extremely rapidly, so correct, early diagnosis is crucial. Young patients are usually healthy but about a third of those over the age of 55 years have associated systemic disease.

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

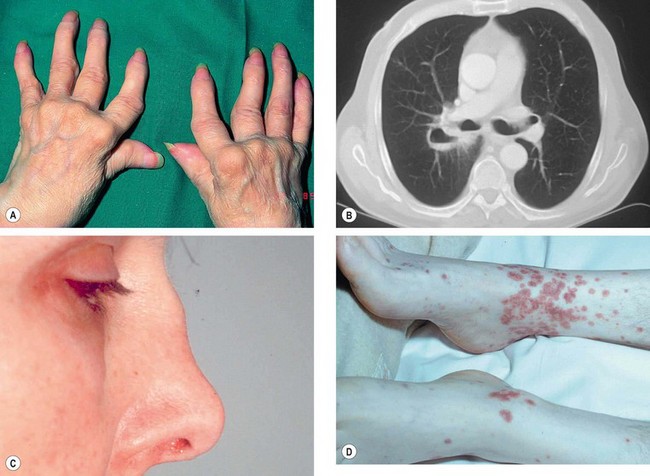

Important systemic associations of scleritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune systemic disease characterized by a symmetrical, destructive, deforming, inflammatory polyarthropathy, in association with a spectrum of extra-articular manifestations and circulating antiglobulin antibodies, termed rheumatoid factor. It is much more common in females than males.

Fig. 8.13 Important systemic associations of scleritis. (A) Severe deformities of the hands in rheumatoid arthritis; (B) CT shows lung cavitation in Wegener granulomatosis; (C) saddle-shaped nasal deformity in relapsing polychondritis; (D) purpura in polyarteritis nodosa

(Courtesy of M Zatouroff, from Physical Signs in General Medicine, Mosby 1996 – fig. A; JA Nerad, KD Carter and MA Alford, from Oculoplastic and Reconstructive Surgery, in Rapid Diagnosis in Ophthalmology, Mosby 2008 – fig. B; C Pavésio – fig. C)

Wegener granulomatosis

Wegener granulomatosis is an idiopathic, multisystem granulomatous disorder characterized by generalized small vessel vasculitis affecting predominantly the respiratory tract and the kidneys. It affects males more commonly than females.

Relapsing polychondritis

Relapsing polychondritis is a rare idiopathic condition characterized by small vessel vasculitis involving cartilage resulting in recurrent, often progressive, inflammatory episodes involving multiple organ systems.

Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is an idiopathic, potentially lethal, collagen vascular disease affecting medium-sized or small arteries. It is three times more common in males than in females. Ocular involvement may precede the systemic manifestations by several years.

Treatment of immune-mediated scleritis

Infectious scleritis

Infectious scleritis is rare but may be difficult to diagnose because the initial clinical features may be similar to those of immune-mediated disease. In some cases infection may follow surgical or accidental trauma, severe endophthalmitis, or may occur as an extension of primary corneal infection.

Causes

Treatment

Once the infective agent has been identified, specific antimicrobial therapy should be initiated. Topical and systemic steroids may also be used to reduce the inflammatory reaction. If appropriate, surgical debridement not only facilitates the penetration of antibiotics but also debulks the infected scleral tissue.

Scleral discoloration

Alkaptonuria

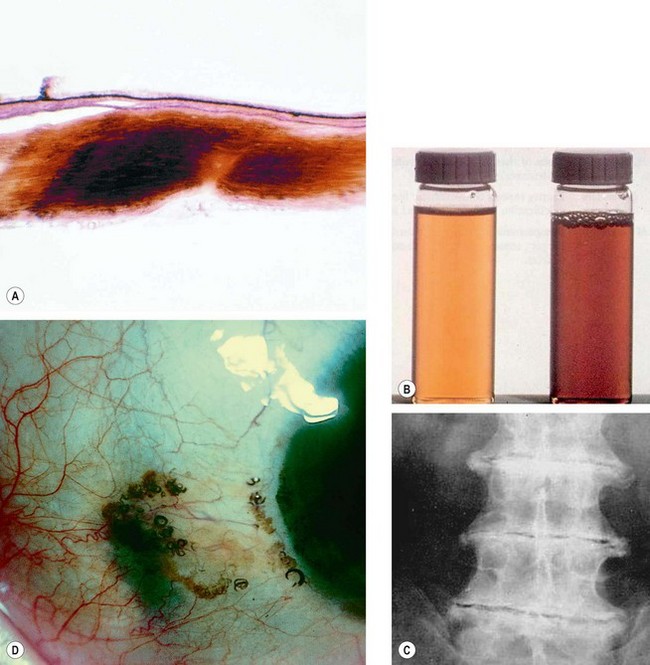

Fig. 8.15 Alkaptonuria. (A) Histology of scleral ochronosis; (B) dark urine with normal for comparison; (C) spinal disc degeneration; (D) pigmentation of the sclera and horizontal rectus tendons associated with pigment globules

(Courtesy of J Harry and G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2001 – fig. A)

Haemochromatosis

Blue sclera

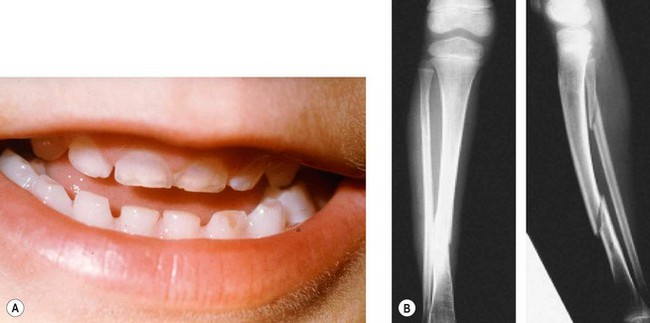

Blue discoloration is caused by thinning or transparency of scleral collagen with visualization of the underlying uvea (Fig. 8.16). Important causes include the following:

Osteogenesis imperfecta

Osteogenesis imperfecta is an inherited disease of connective tissue, usually caused by defects in the synthesis and structure of Type 1 collagen. There are multiple types, at least two of which have ocular features.

Type I

Type IIA

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome type VI

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome VI (ocular sclerotic) is a rare, usually AR disorder of collagen caused by deficiency of procollagen lysyl hydroxylase. There are nine distinct subtypes but type 6 and, rarely, type 4, are associated with ocular features.

Other systemic associations

Miscellaneous conditions

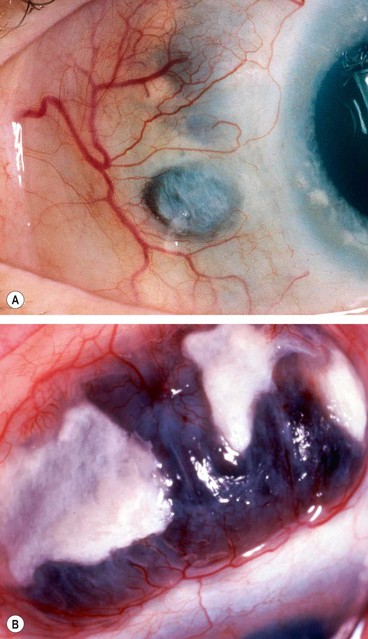

Congenital ocular melanocytosis

Classification

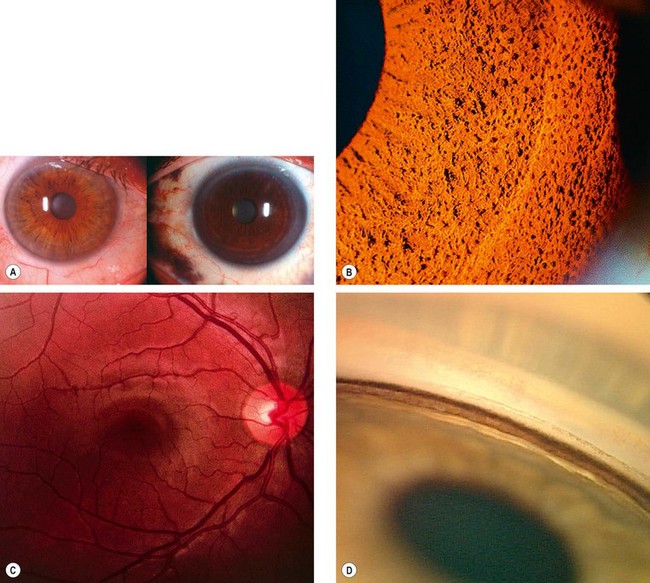

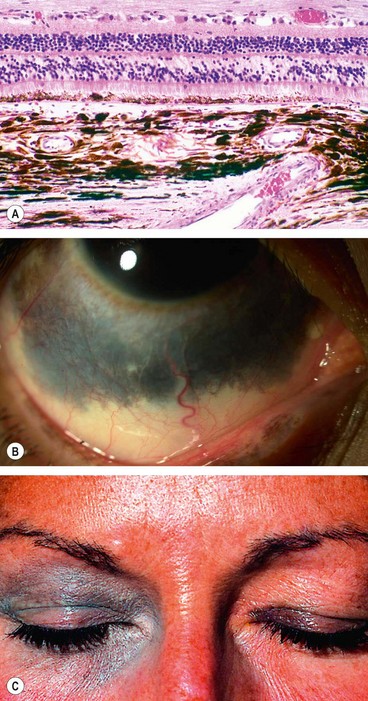

Congenital ocular melanocytosis is an uncommon condition characterized by an increase in number, size and pigmentation of melanocytes (Fig. 8.19A) in the sclera and uvea and may also involve the periocular skin, orbit, meninges and soft palate. It occurs in the following three clinical settings.

Fig. 8.19 Congenital melanocytosis. (A) Histology shows an increase in the number, size and pigmentation of melonocytes in the inner sclera and choroid; (B) episcleral melanocytosis; (C) cutaneous melanocytosis

(Courtesy of J Harry and G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2001 – fig. A)

Clinical features

Ipsilateral associations

Idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification

Idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification is an innocuous, age-related condition that is usually bilateral.

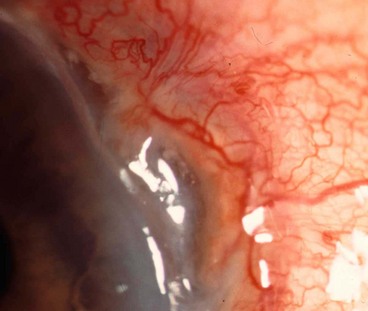

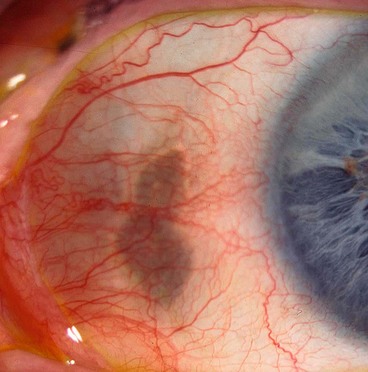

Scleral hyaline plaque

Scleral hyaline plaques are bilateral oval, dark-greyish areas located close to the insertion of the horizontal rectus muscles (Fig. 8.22) that should not be confused with scleromalacia perforans. They typically affect elderly patients and are entirely innocuous.