Chapter 11 Uveitis

Introduction

Anatomical classification

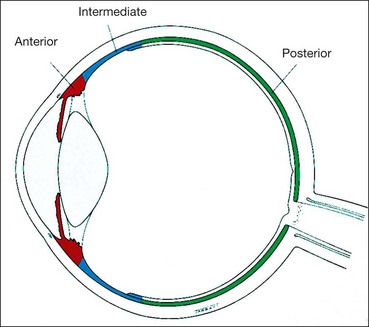

The uvea is the vascular layer of the eye and comprises the iris, ciliary body and choroid (Fig. 11.1).

Anterior uveitis is the most common, followed by posterior, intermediate and panuveitis.

Definitions

Clinical features

Acute anterior uveitis

Anterior uveitis is the most common form of uveitis. Acute anterior uveitis (AAU) is the most common form of anterior uveitis, accounting for three-quarters of cases. It is characterized by sudden onset and duration of 3 months or less. It is easily recognized due to the severity of symptoms which will force the patient to seek medical attention.

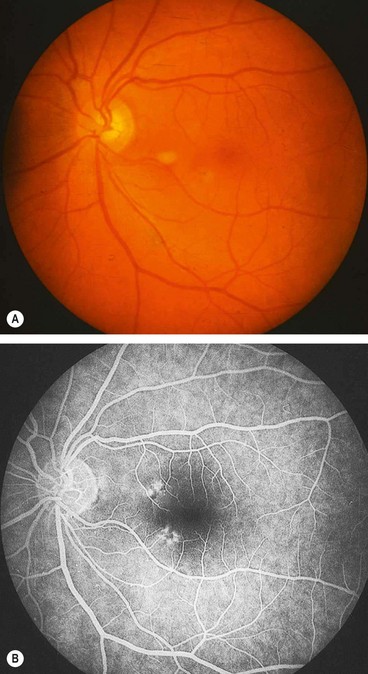

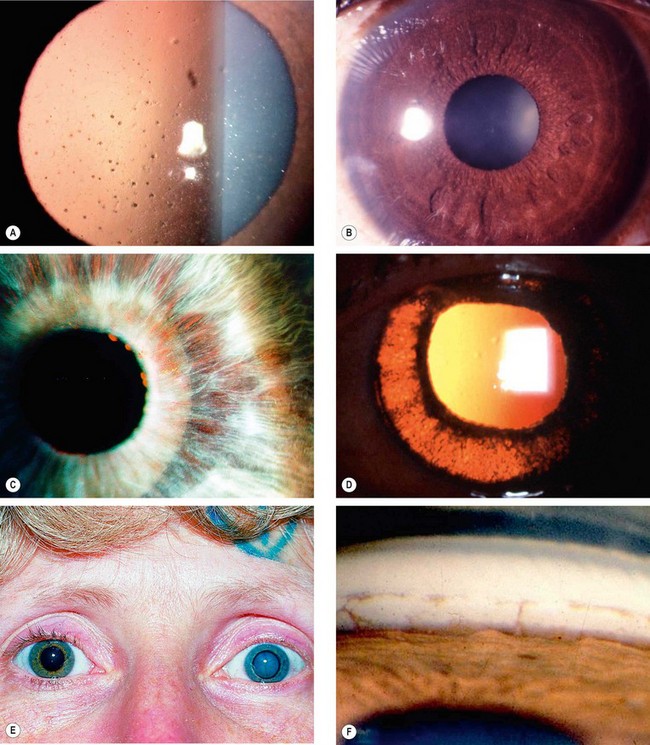

Fig. 11.2 Signs of acute anterior uveitis. (A) Ciliary injection; (B) miosis; (C) endothelial dusting by cells; (D) aqueous flare and cells; (E) fibrinous exudate; (F) hypopyon

(Courtesy of JS Schuman, V Christopoulos, DK Dhaliwal, MY Kahook and RJ Noecker, from Lens and Glaucoma in Rapid Diagnosis in Ophthalmology, Mosby 2008 – fig. D).

Table 11.1 Grading anterior chamber cells

| Cells in field | Grade |

|---|---|

| <1 | 0 |

| 1–5 | ± |

| 6–15 | +1 |

| 16–25 | +2 |

| 26–50 | +3 |

| >50 | +4 |

Table 11.2 Grading of aqueous flare

| Description | Grade |

|---|---|

| Nil | 0 |

| Just detectable | +1 |

| Moderate (iris and lens details clear) | +2 |

| Marked (iris and lens details hazy) | +3 |

| Intense (fibrinous exudate) | +4 |

Chronic anterior uveitis

Chronic anterior uveitis (CAU) is less common than the acute type and is characterized by persistent inflammation that promptly relapses, in less than 3 months, after discontinuation of treatment. The inflammation may be granulomatous or non-granulomatous. Bilateral involvement is more common than in AAU.

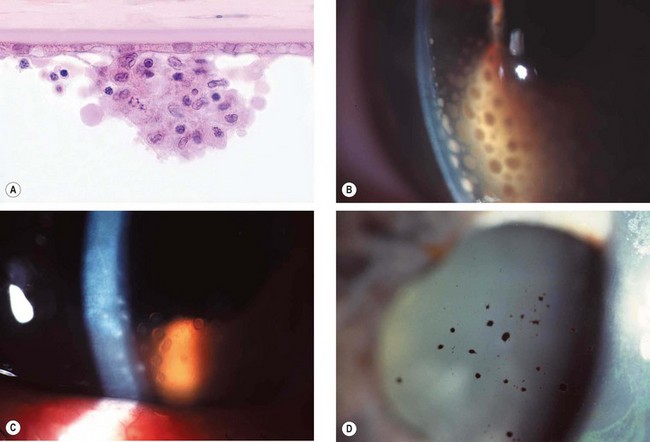

Fig. 11.4 Keratic precipitates. (A) Aggregate of inflammatory cells on the corneal endothelium; (B) large ‘mutton-fat’ keratic precipitates; (C) ‘ghost’ keratic precipitates; (D) old pigmented keratic precipitates

(Courtesy of J Harry and G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology, Butterworth-Heinemann 2001 – fig. A)

Posterior uveitis

Posterior uveitis encompasses retinitis, choroiditis and retinal vasculitis. Some lesions may originate primarily in the retina or choroid but often there is involvement of both (retinochoroiditis and chorioretinitis).

Special investigations

Skin tests

Serology

Syphilis

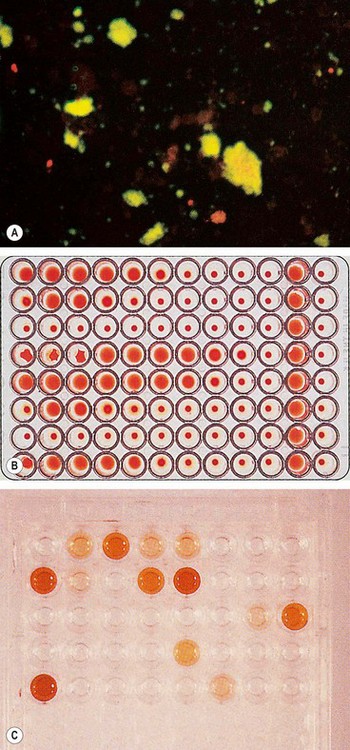

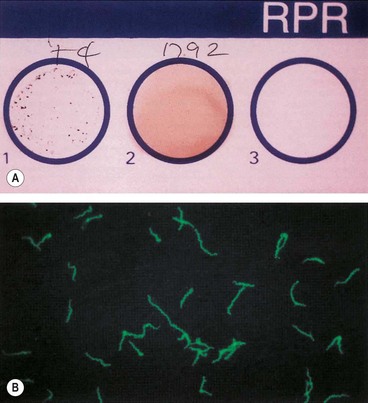

Because of the variable presentation serology should be performed in all patients with uveitis who require investigation. Serological tests rely on detection of nonspecific antibodies (cardiolipin) or specific treponemal antibodies.

Fig. 11.8 Serological tests for syphilis. (A) Rapid plasma regain (RPR) for syphilis showing clumping of the antigenic particles (left) after 4 minutes; (B) positive fluorescent treponema antibody test (FTA-ABS) for syphilis

(Courtesy of Mims, Dockrell, Goering, Roitt, Wakelin and Zuckerman, from Medical Microbiology, Mosby 2004)

Toxoplasmosis

Enzyme assay

HLA tissue typing

Table 11.3 HLA type and systemic disease

| HLA type | Associated disease |

|---|---|

| B27 | Spondyloarthropathies, particularly ankylosing spondylitis |

| A29 | Birdshot chorioretinopathy |

| B51 | Behçet syndrome |

| HLA-B7 and HLA-DR2 | POHS and APMPPE |

Imaging

Radiology

Biopsy

Histopathology still remains the gold standard for definitive diagnosis of many conditions. Biopsies of the skin or other organs may establish the diagnosis of a systemic disorder associated with the ocular manifestations, such as sarcoidosis. However, intraocular structures are relatively inaccessible to this procedure without running the risk of significant morbidity.

Principles of treatment

General principles

Treatment of immune-mediated uveitis involves predominantly the use of anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agents. Antibiotic therapy for infectious diseases will be discussed in the specific sections. It is important to keep in mind that drugs used to treat uveitis have potential side-effects, and this should always be weighed against the decision to treat. Also, it must be emphasized that the use of systemic therapy should be carried out in conjunction with a physician who is competent to deal with complications associated with both the underlying disease and the therapy.

Mydriatics

Indications

Topical steroids

Indications

Complications

Periocular steroid injection

Intraocular steroids

Systemic steroids

Antimetabolites

Indications

Azathioprine

Methotrexate

Calcineurin inhibitors

Ciclosporin

Intermediate uveitis

Overview

Intermediate uveitis (IU) is an insidious, chronic, relapsing disease in which the vitreous is the major site of inflammatory signs. The condition may be idiopathic or associated with a systemic disease (see below). Pars planitis (PP) is a subset of IU in which there is ‘snowbanking’ and/or ‘snowball’ formation. IU accounts for up to 15% of all uveitis cases and about 20% of paediatric uveitis. The diagnosis is essentially clinical, and investigations are carried out to exclude a systemic association, especially in the presence of suggestive findings and in older individuals. The exact age of onset of IU may be difficult to determine, since an extended period may elapse before patients become symptomatic.

Diagnosis

Table 11.4 Grading of vitreous haze

| Haze severity | Grading |

|---|---|

| Good view of nerve fibre layer (NFL) | 0 |

| Clear disc and vessels but hazy NFL | +1 |

| Disc and vessels hazy | +2 |

| Only disc visible | +3 |

| Disc not visible | +4 |

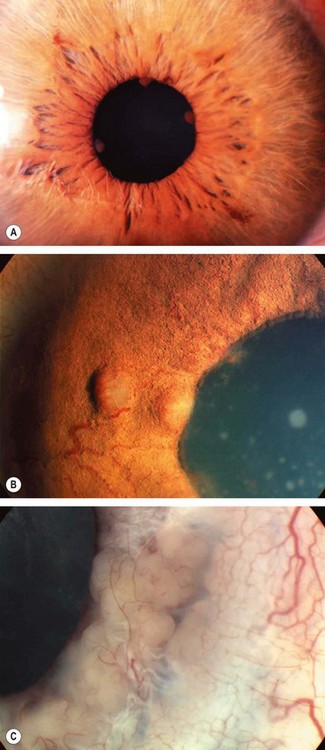

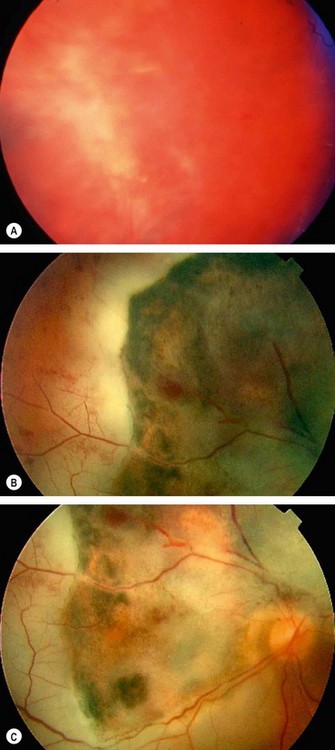

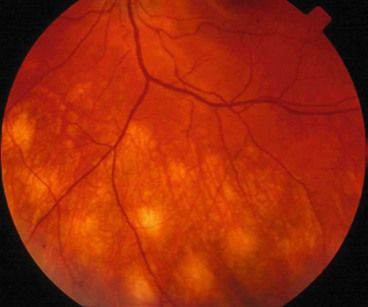

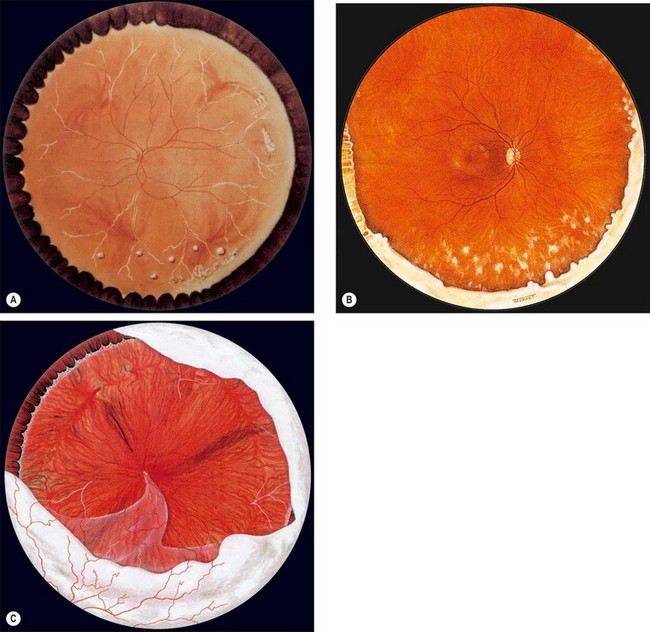

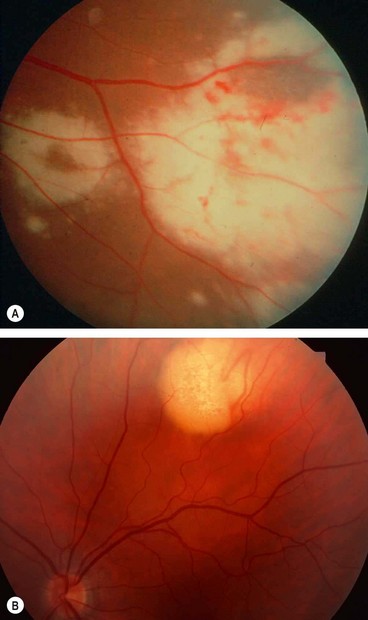

Fig. 11.11 Posterior segment signs in intermediate uveitis. (A) Peripheral periphlebitis and a few snowballs inferiorly; (B) inferior snowbanking and snowballs; (C) severe snowbanking, neovascularization and inferior retinal detachment

(Courtesy of CL Schepens, ME Hartnett and T Hirose, from Schepens’ Retinal Detachment and Allied Diseases, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000 – figs A and C)

Course

Complications

Treatment

Systemic associations

Differential diagnosis

Chronic conditions which produce vitritis, or peripheral retinal changes mimicking IU include the following:

Uveitis in spondyloarthropathies

HLA-B27 and spondyloarthropathies

A strong association exists between HLA-B27 and spondyloarthropathies; the prevalence of HLA B-27 is as follows:

The AAU associated with HLA-B27 is typically unilateral, severe, recurrent and associated with a higher incidence of posterior synechiae. A fibrinous exudate in the anterior chamber is common. Patients who do not carry HLA-B27 tend to have a more benign course with fewer recurrences.

Ankylosing spondylitis

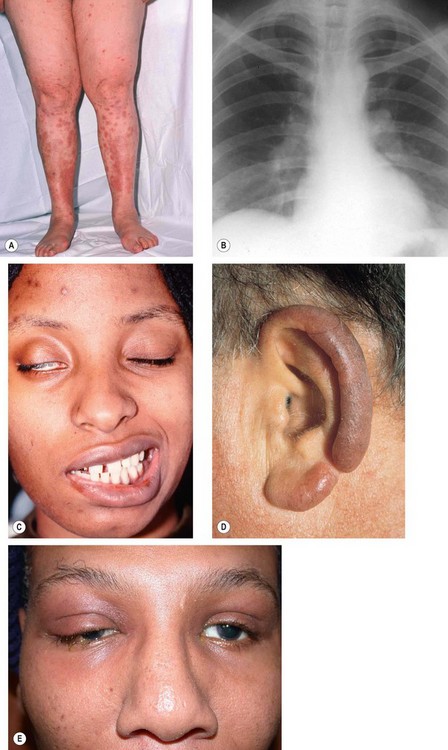

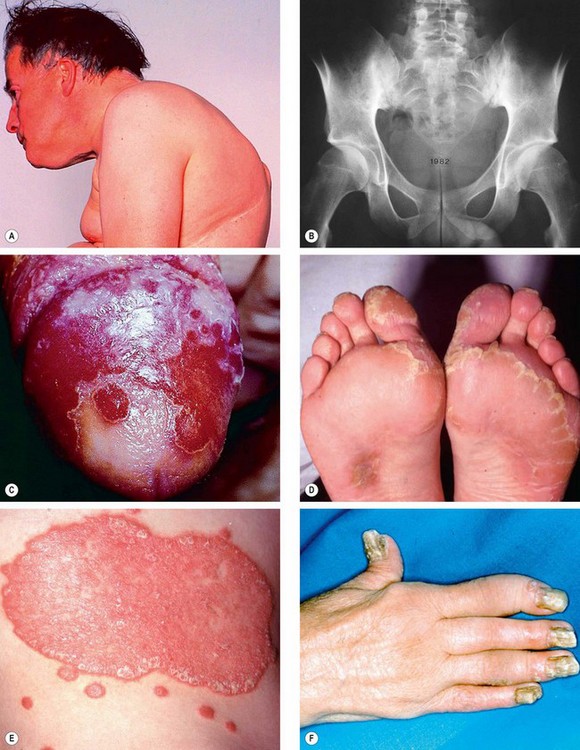

Fig. 11.12 Spondyloarthropathies. (A) Fixed flexion deformity in ankylosing spondylitis; (B) sclerosis and bony obliteration of the sacroiliac joints in ankylosing spondylitis; (C) circinate balanitis in Reiter syndrome; (D) keratoderma blenorrhagica in Reiter syndrome; (E) psoriasis; (F) arthritis of the fingers and severe nail dystrophy in psoriatic arthritis

(Courtesy of MA Mir, from Atlas of Clinical Diagnosis, Saunders 2003 – fig. A; RT Emond, PD Welsby and HA Rowland, from Colour Atlas of Infectious Diseases, Mosby 2003 – fig. C)

Reiter syndrome

Psoriatic arthritis

Uveitis in juvenile arthritis

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Overview

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is an inflammatory arthritis of at least 6 weeks’ duration occurring before the age of 16 years when all other causes, such as infection, metabolic disorders or neoplasms have been excluded. Females are affected more commonly by a ratio of 3 : 2. JIA is by far the most common disease associated with childhood anterior uveitis. It should be emphasized that JIA is not the same as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA); the former is negative for rheumatoid factor whereas the latter is positive; JRA is the same disease as rheumatoid arthritis except that it occurs before the age of 16 years.

Arthritis

Anterior uveitis

Differential diagnosis

Familial juvenile systemic granulomatosis syndrome

Familial juvenile systemic granulomatosis (Blau syndrome), is a rare AD disorder characterized by childhood onset of granulomatous disease of skin, eyes and joints but absence of pulmonary disease.

Uveitis in bowel disease

Ulcerative colitis

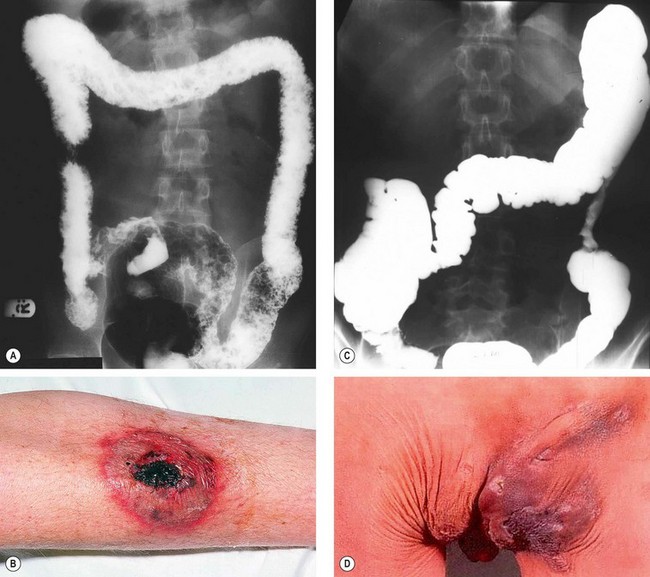

Fig. 11.14 Inflammatory bowel disease. (A) Barium enema in ulcerative colitis shows pseudopolyposis, lack of haustral markings and straightening of the ascending colon; (B) pyoderma gangrenosum in ulcerative colitis; (C) barium enema in Crohn disease shows a stricture in the descending colon; (D) perianal abscess and fistula in Crohn disease

(Courtesy of CD Forbes and WF Jackson, from Color Atlas and Text in Clinical Medicine, Mosby 2003 – fig. D)

Crohn disease

Whipple disease

Uveitis in renal disease

Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU)

IgA glomerulonephritis

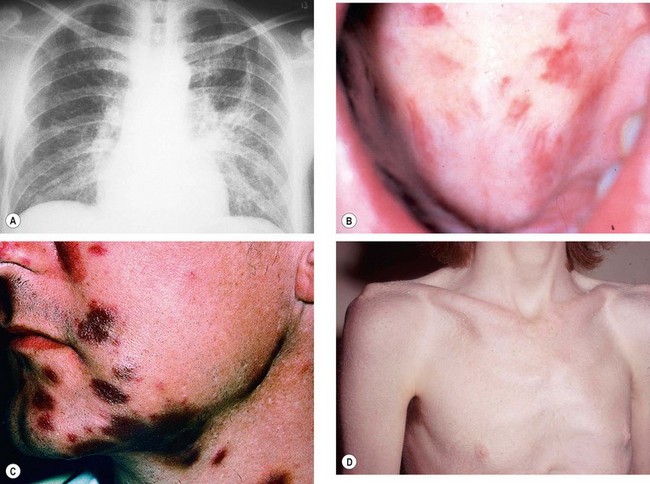

Sarcoidosis

Definition

Sarcoidosis is a T-lymphocyte-mediated non-caseating granulomatous inflammatory disorder of unknown cause. It is most common in colder climates, although it more frequently affects patients of African descent than Caucasians. The clinical spectrum of disease varies from mild single-organ involvement to potentially fatal multisystem disease which can affect almost any tissue. The tissues most commonly involved are the mediastinal and superficial lymph nodes, lungs, liver, spleen, skin, parotid glands, phalangeal bones and the eye.

Presentation

Pulmonary disease

Skin lesions

The skin is involved in about 25% of patients by one of the following:

Other manifestations

Investigations

Ocular features

Uveitis is the most common and may be in the form of anterior, posterior or intermediate. Other manifestations include KCS, conjunctival nodules, and rarely, orbital and scleral lesions.

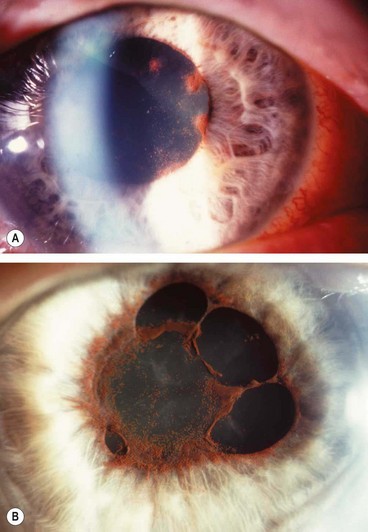

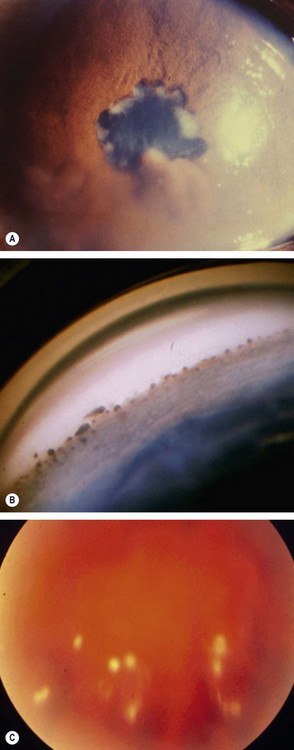

Fig. 11.16 Ocular sarcoidosis (A) Large iris nodules; (B) nodular involvement of the trabecular meshwork; (C) snowballs

(Courtesy of J Salmon – fig. A)

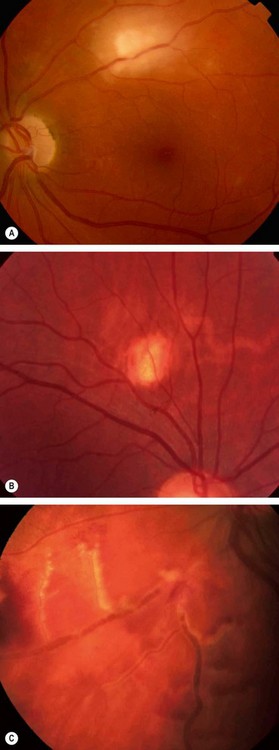

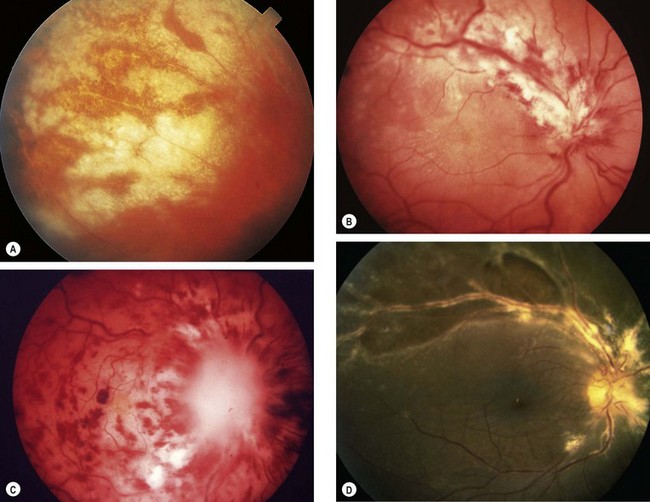

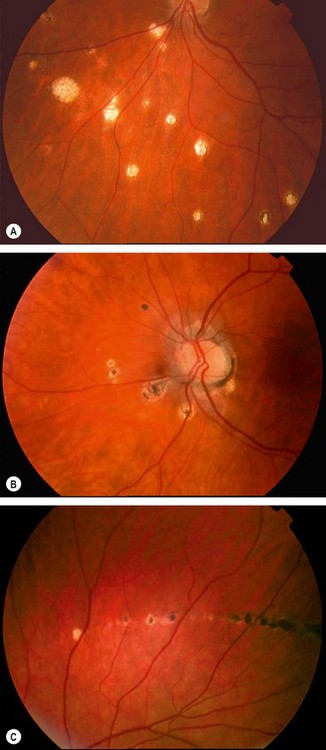

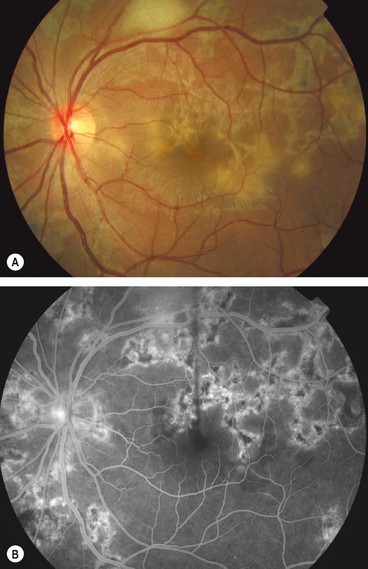

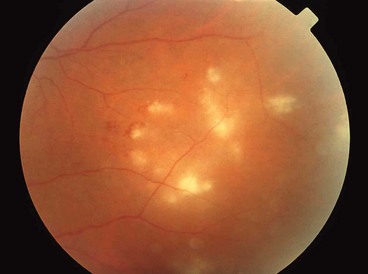

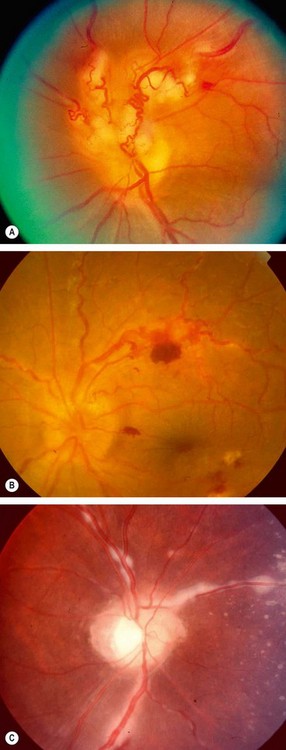

Fig. 11.17 Periphlebitis in sarcoidosis. (A) Periphlebitis with involvement of the optic nerve head; (B) occlusive periphlebitis and disc oedema; (C) ‘candlewax’ drippings

(Courtesy of J Donald M Gass, from Stereoscopic Atlas of Macular Diseases, Mosby 1997 – fig. A; C Pavésio – fig. B; P Morse – fig. C)

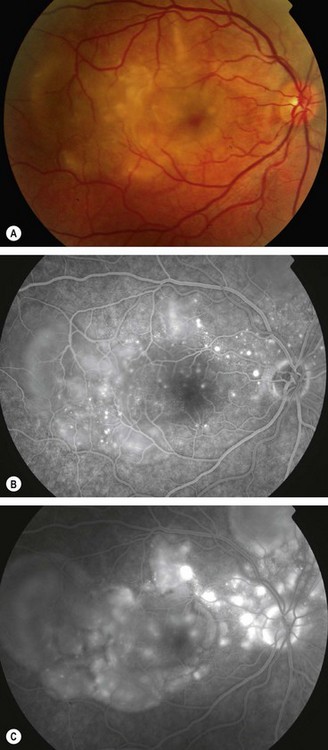

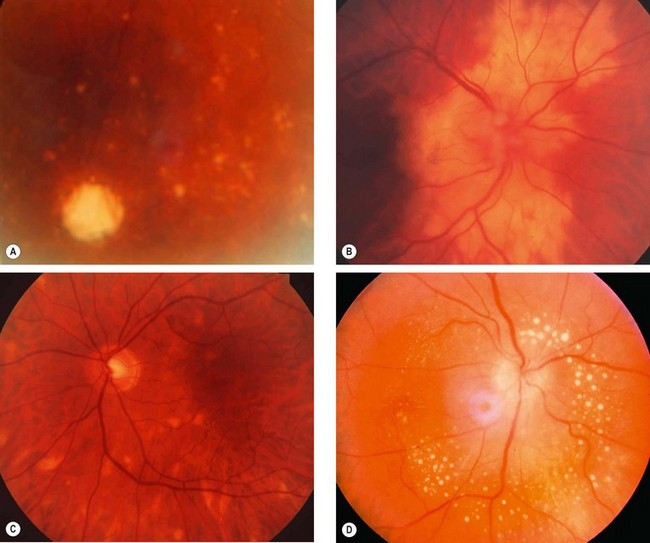

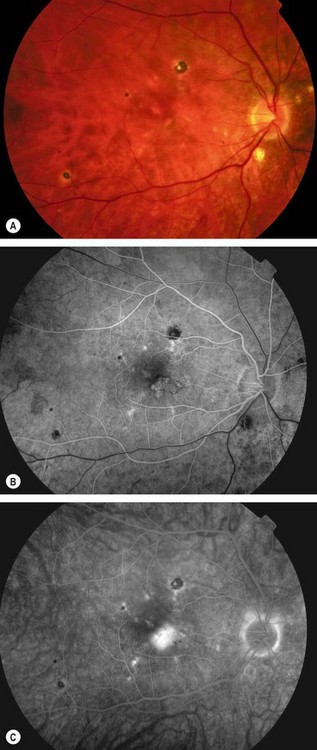

Fig. 11.18 Choroidal and retinal involvement in sarcoidosis. (A) Small peripheral choroidal granulomas; (B) confluent choroidal infiltrates; (C) multifocal choroiditis; (D) multiple small retinal granulomas

Table 11.5 Differential diagnosis of posterior segment sarcoid

Behçet syndrome

Overview

Behçet syndrome (BS) is an idiopathic, multisystem disease characterized by recurrent episodes of orogenital ulceration and vasculitis which may involve small, medium and large veins and arteries. The disease typically affects patients from the eastern Mediterranean region and Japan and is strongly associated with human leucocyte antigen (HLA) B51 in different ethnic groups; it is not clear whether the HLA-B51 itself is the pathogenic gene related to BS or some other gene is in linkage disequilibrium. The peak age of onset of BS is in the 3rd decade, although rarely it presents in childhood or old age; males are affected more frequently than females.

Diagnostic criteria

Additional features

Ocular features

Ocular complications occur in up to 95% of men and 70% of women. Eye disease typically occurs within 2 years of oral ulceration, but rarely the delay may be as long as 14 years. Conversely, ocular inflammation is the presenting manifestation in about 10% of cases. Ocular disease is usually bilateral and typically presents during the 3rd–4th decades.

Treatment of posterior uveitis

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis in patients with suggestive ocular findings but lack of classical systemic manifestations should include the following:

Toxoplasmosis

Introduction

Pathogenesis

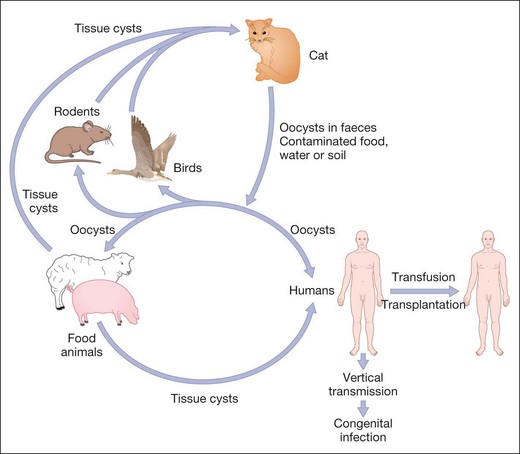

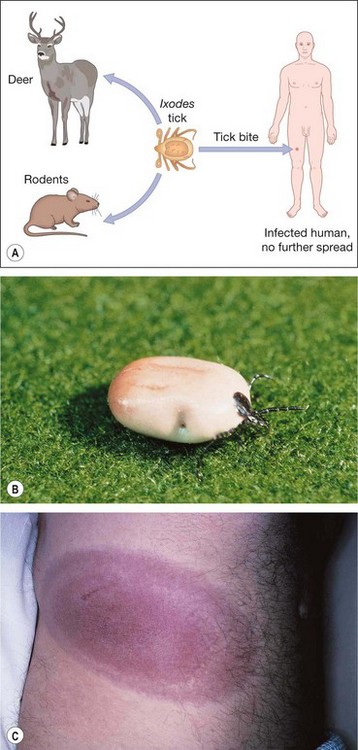

Toxoplasmosis is caused by Toxoplasma gondii, an obligate intracellular protozoan. It is estimated to infest at least 10% of adults in northern temperate countries and more than half of adults in Mediterranean and tropical countries. The cat is the definitive host and intermediate hosts include mice, livestock and humans (Fig. 11.21). The parasite exists in the following forms:

Mode of human infection

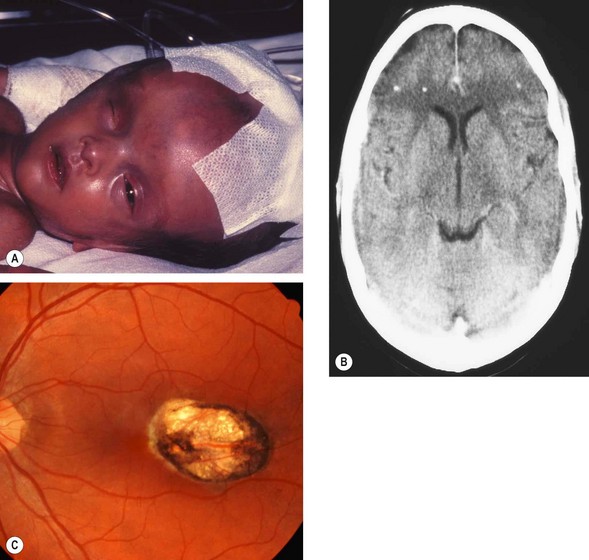

Congenital toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis is transmitted to the fetus through the placenta when a pregnant woman becomes infected. If the mother is infected before pregnancy, the fetus will be unscathed.

Acquired toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasma retinitis

Pathogenesis

Toxoplasmosis is the most frequent cause of infectious retinitis in immunocompetent individuals. Reactivation at previously inactive cyst-containing scars is the rule in the immunocompetent, although a small minority may represent new infection. Most quiescent lesions will have been acquired postnatally. Recurrent episodes of inflammation are common and occur when the cysts rupture and release hundreds of tachyzoites into normal retinal cells. Recurrences usually take place between the ages of 10 and 35 years (average age 25 years).

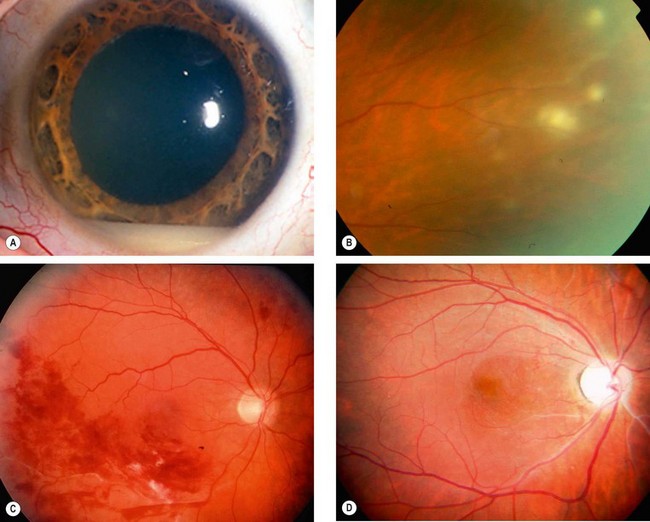

Clinical features

The diagnosis of toxoplasma retinitis is based on a compatible fundus lesion and positive serology for toxoplasma antibodies (see ‘Investigations’). Any antibody titre is significant because in recurrent ocular toxoplasmosis, no correlation exists between the titre and the activity of retinitis.

Complications

Nearly 25% of eyes develop visual loss as a result of the following:

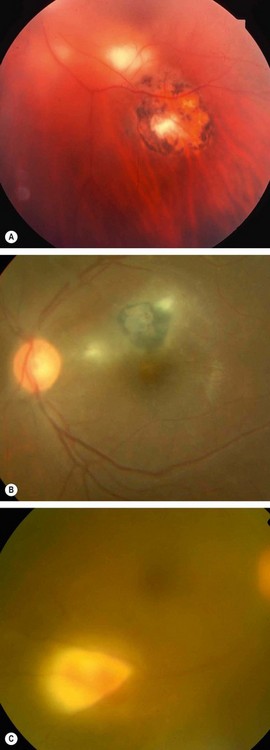

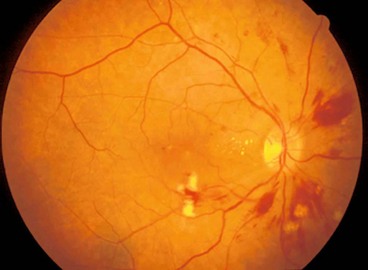

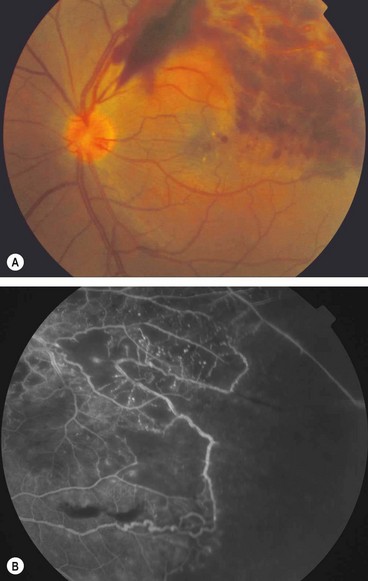

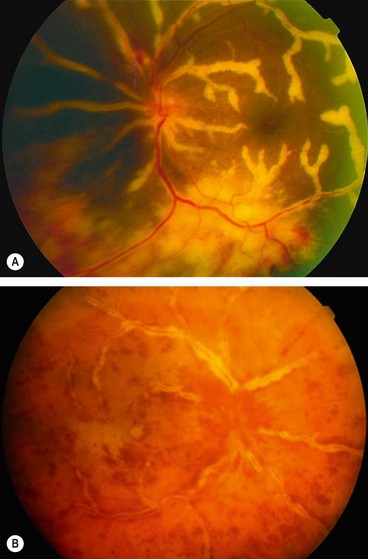

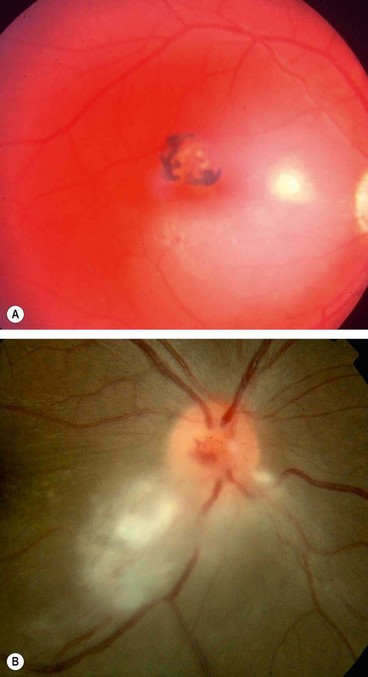

Fig. 11.26 Common complications of toxoplasma retinitis. (A) Scar at the fovea and a fresh lesion involving the papillomacular bundle; (B) juxtapapillary lesion involving the optic nerve head

Fig. 11.27 Uncommon complications of toxoplasma retinitis. (A) Periarteritis resulting in branch retinal artery occlusion; (B) FA shows extensive non-perfusion at the posterior pole; (C) choroidal neovascularization adjacent to an old scar; (D) FA shows corresponding hyperfluorescence; (E) serous macular detachment; (F) FA shows hyperfluorescence due to pooling of dye

(Courtesy of C Pavésio – figs A, B, E and F; P Gili – figs C and D)

Treatment

Toxocariasis

Pathogenesis

Toxocariasis is caused by an infestation with a common intestinal ascarid (roundworm) of dogs called Toxocara canis (Fig. 11.28A). About 80% of puppies between the ages of 2 and 6 months are infested with this worm. Human infestation is by accidental ingestion of soil or food contaminated with ova shed in dogs’ faeces. Very young children who eat dirt (pica) or are in close contact with puppies are at particular risk of acquiring the disease. In the human intestine, the ova develop into larvae which penetrate the intestinal wall and travel to various organs, such as the liver, lungs, skin, brain and eyes (Fig. 11.28B). When the larvae die, they disintegrate and cause an inflammatory reaction followed by granulation. Clinically, human infestation can take one of the following forms:

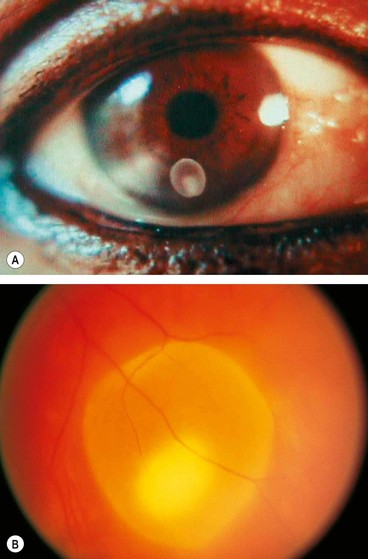

Chronic endophthalmitis

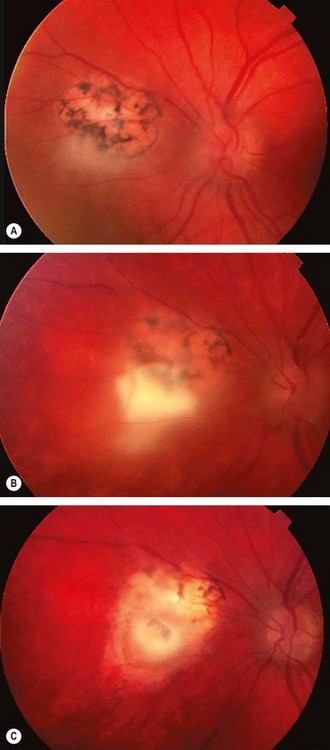

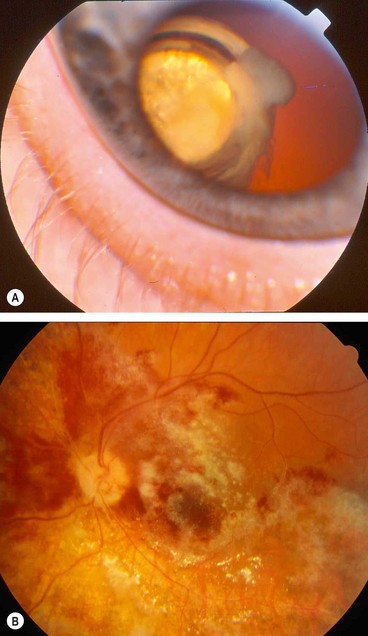

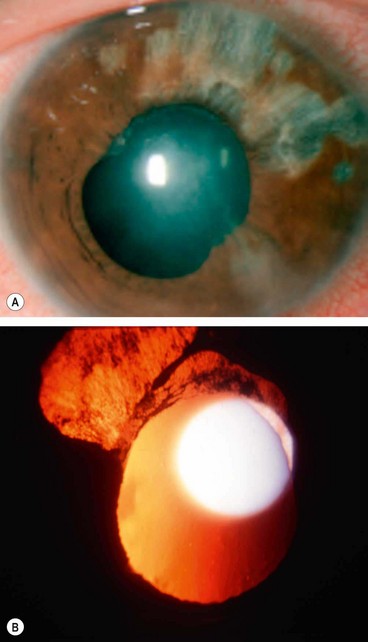

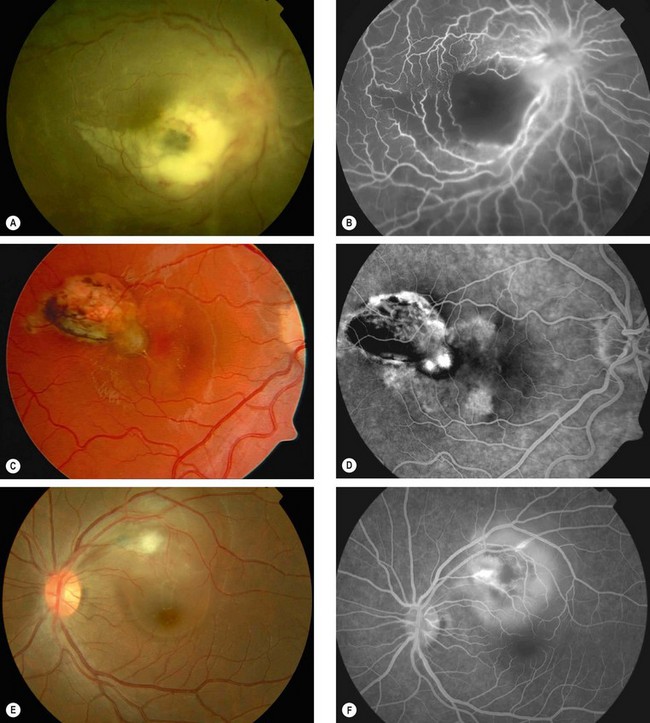

Fig. 11.29 Chronic toxocara endophthalmitis. (A) Leukocoria; (B) peripheral exudation and vitreoretinal traction bands; (C) ultrasonography shows a vitreoretinal traction band; (D) a pathological specimen shows an inflammatory mass and total retinal detachment

(Courtesy of N Rogers – figs A and C; S Lightman – fig. B; J Harry and G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology, Butterworth-Heinemann 2001 – fig. D)

Posterior pole granuloma

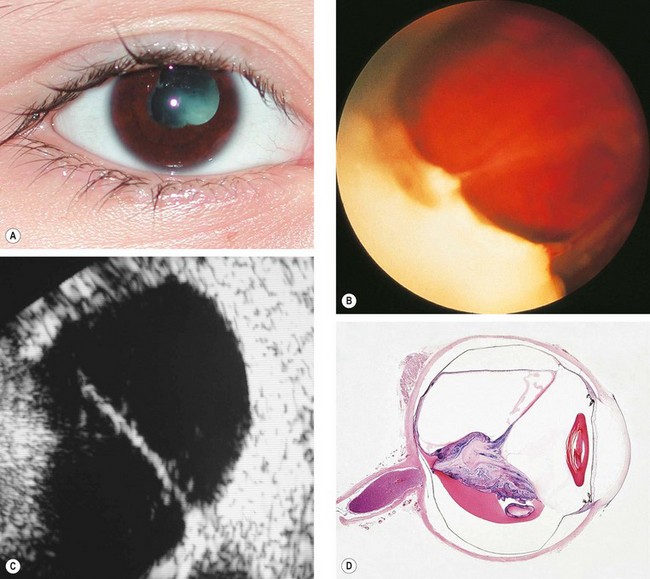

Fig. 11.30 Toxocara granuloma. (A) Juxtapapillary granuloma: (B) posterior pole granuloma associated with a localized tractional retinal detachment; (C) peripheral granuloma with a vitreous band extending to the disc

(Courtesy of J Donald M Gass, from Stereoscopic Atlas of Macular Diseases, Mosby 1997 – fig. A)

Peripheral granuloma

Miscellaneous parasitic uveitis

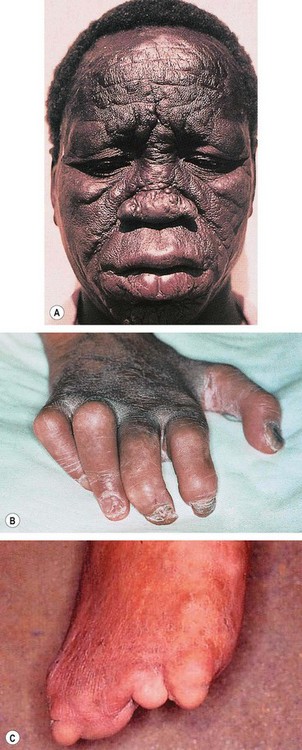

Onchocerciasis

Pathogenesis

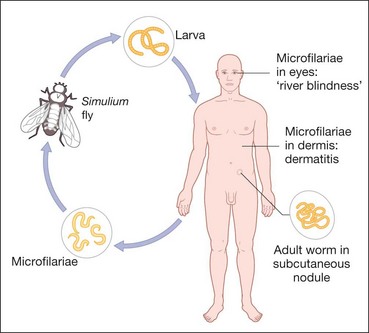

Onchocerciasis or river blindness is caused by infestation with the parasitic helminth Onchocerca volvulus. The normal vector is the black fly Simulium spp., an obligate intermediate host, which breeds in fast flowing water. Larvae are transmitted when the fly bites to obtain blood, which then mature into adult worms that produce millions of microfilariae over years (Fig. 11.31). Wolbachia (a rickettsia) lives symbiotically in the coat of the microfilaria in a fashion similar to mitochondria and are important for fertility of the female filarial worm. Onchocerciasis is endemic in West, Central and East Africa, with small foci in central and South America, Sudan and Yemen. Infecting nearly 18 million people most of whom are asymptomatic but with an estimated 270 000 blind and half a million visually impaired. The disease is especially severe in savannah areas.

Systemic features

Ocular features

Cysticercosis

Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis

Choroidal pneumocystosis

Uveitis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Introduction

Pathogenesis

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). On a worldwide basis, heterosexual intercourse is the predominant mode of transmission; in the western world, however, AIDS is commonly transmitted by male homosexual contact. Transmission may also occur by contaminated blood or needles, transplacentally or via breast milk. HIV targets CD4+ T cells, which are vital to the initiation of the immune response to pathogens. A steady decline in the absolute number of CD4+ T cells therefore occurs, resulting in progressive immune deficiency, particularly of cell mediated immunity. Regular estimation of the CD4+ T cell count is therefore a useful measure of disease progression.

Systemic features

Serology

Treatment

Although there is no cure for AIDS, the progression of disease can be radically slowed by a number of drugs. The aim of treatment is to reduce the plasma viral load. Ideally therapy should be commenced before the development of irreversible damage to the immune system.

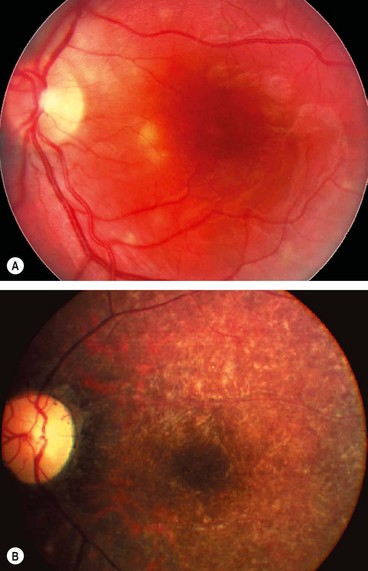

HIV microangiopathy

Retinal microangiopathy is the most frequent retinopathy in patients with AIDS, developing in up to 70% of patients and is associated with a declining CD4+ count. Postulated causes include immune complex deposition, HIV infection of the retinal vascular endothelium, haemorheological abnormalities and abnormal retinal haemodynamics.

Cytomegalovirus retinitis

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis is the most common opportunistic ocular infection among patients with AIDS. Since the advent of HAART its incidence has declined and its rate of progression reduced, even in patients with low CD4+ T cell counts. It also appears that the rates of second eye involvement and retinal detachment are less than in the pre-HAART era.

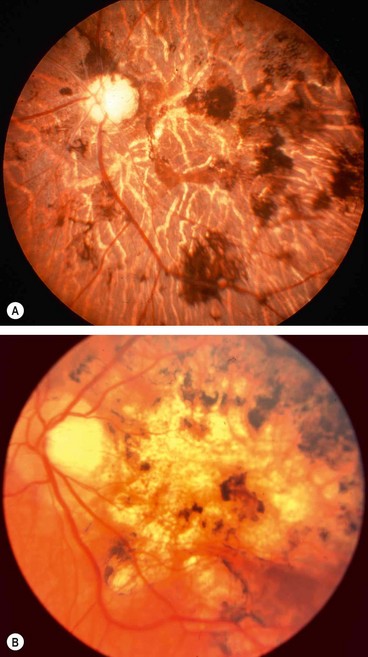

Clinical features

Systemic treatment

Intravitreal treatment

Prognosis

Initially 95% of cases respond to treatment. Regression is characterized by fewer haemorrhages and less opacification, followed by diffuse atrophy and mild pigmentary changes (Fig. 11.41B). Since the introduction of HAART therapy the incidence of CNV retinitis has decreased and many patients have had their treatment of retinitis stopped after immune recovery (CD4 > 100–150). Many patients with HAART-induced immune recovery develop intraocular inflammation which may cause macular oedema and epiretinal membrane formation, requiring aggressive treatment.

Progressive retinal necrosis

Miscellaneous viral uveitis

Acute retinal necrosis

Herpes simplex anterior uveitis

Varicella zoster anterior uveitis

Congenital rubella

Rubella (German measles) is usually a benign febrile exanthema. Congenital rubella results from transplacental transmission of virus to the fetus from an infected mother, usually during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis

Fungal uveitis

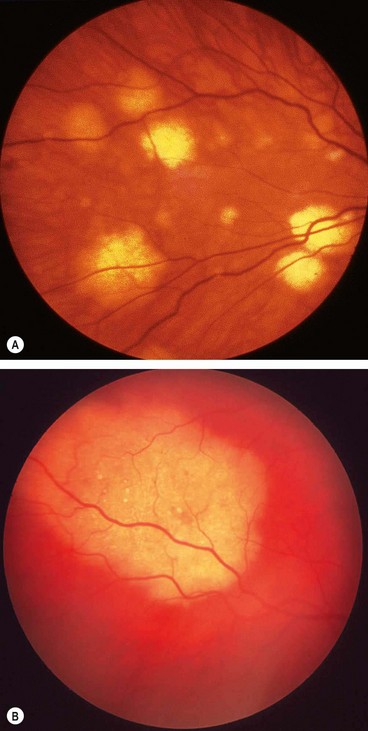

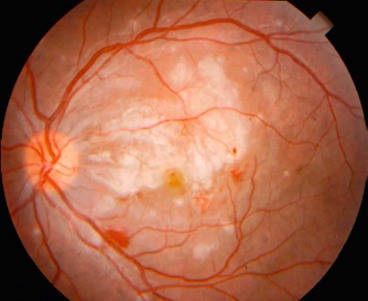

Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome

Pathogenesis

Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum acquired by inhalation of infective mycelia fragments and/or spores with dust particles. The organisms then pass via the bloodstream to the spleen, liver and, on occasion, the choroid, setting up multiple foci of granulomatous inflammation. Although ocular histoplasmosis has never been reported in patients with active systemic histoplasmosis, eye disease has an increased prevalence in areas where histoplasmosis is endemic, such as the Mississippi–Missouri river valley and is speculated that presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (POHS) represents an immune-mediated response in individuals previously exposed to the fungus. Patients with POHS show an increased prevalence of HLA-B7 and HLA-DR2. POHS is asymptomatic unless it causes a maculopathy.

General signs

Exudative maculopathy

Choroidal neovascularization (CNV) is a late manifestation which usually develops between the ages of 20 and 45 years in about 5% of eyes. In most cases, CNV is associated with an old macular ‘histo spot’, although occasionally it develops within a peripapillary lesion.

Cryptococcosis

Pathogenesis

Soil contaminated with pigeon droppings containing encapsulated dimorphic yeast, Cryptococcus neoformans, enters the body through inhalation. Infection primarily affects patients with cell-mediated immune deficiency and occurs in 5–10% of patients with AIDS. Other predisposing factors include lymphoma, active hepatitis, alcoholism, uraemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, organ transplantation with immunosuppression and close exposure to pigeons.

Systemic features

Ocular features

Ocular involvement is present in approximately 6% of patients with cryptococcal meningitis. The most likely route of infection is via direct extension from the optic nerve or by haematogenous spread to the choroid and retina.

Endogenous fungal endophthalmitis

Bacterial uveitis

Tuberculosis

Pathogenesis

Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic granulomatous infection caused by the tubercle bacillus which is of the genus Mycobacterium, which are non-motile, non-sporing, strictly aerobic acid-fast rods. The two species responsible for TB in humans are the human strain M. tuberculosis, which is acquired by inhaling infected airborne droplets, and the bovine strain M. bovis, which is acquired by drinking unpasteurized milk from infected cattle. TB is primarily a pulmonary disease but it may spread by the bloodstream to other sites to form a generalized (miliary) infection. Human immunodeficiency virus increases the risk of developing TB. In addition infection with atypical mycobacteria such as M. avium complex may cause disease in immunocompromised individuals.

Anterior segment involvement

Tuberculous uveitis

Tuberculous uveitis may be difficult to diagnose because it may occur in patients without systemic manifestations of TB. The diagnosis is therefore often presumptive, based on indirect evidence such as intractable uveitis unresponsive to steroid therapy, a positive history of contact, a positive skin test and negative findings for other causes of uveitis.

Fig. 11.51 Tuberculous choroiditis (A) Diffuse involvement in a patient with AIDS; (B) choroidal granuloma

(Courtesy of C de A Garcia – fig. A)

Syphilis

Pathogenesis

Syphilis is caused by the spirochaete bacterium Treponema pallidum. The organism is thin and has a spiral shape resulting in corkscrew movements. It is very fragile, does not live in culture and dies quickly on drying or heat. In adults the disease is usually sexually acquired when the treponemes enter through an abrasion of skin or mucous membrane. Transmission by kissing, blood transfusion and percutaneous injury are rare. Transplacental infection of the fetus can also occur from a mother who has become infected during or shortly before pregnancy. Although the infection is systemic from onset, in some cases clinical manifestations may be minimal or absent. The natural history of untreated syphilis is variable and may remain latent throughout, although overt disease may develop at any time.

Stages

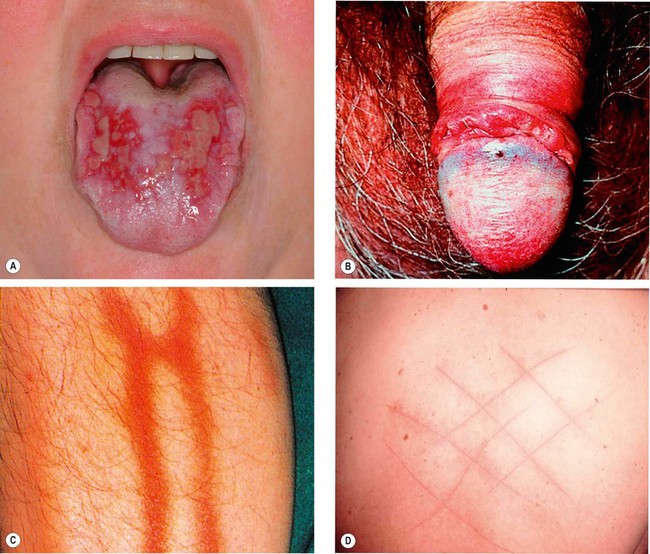

Syphilitic uveitis

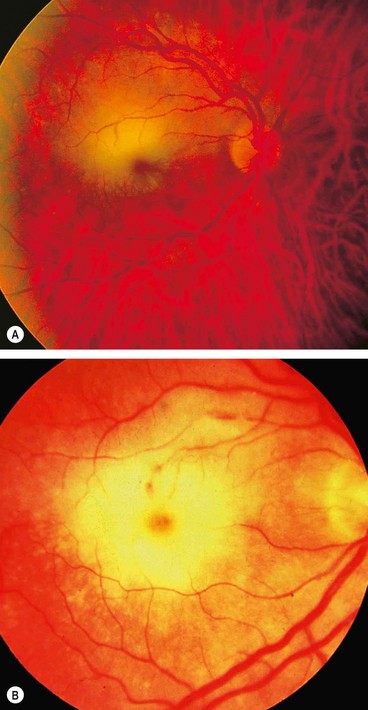

Fig. 11.55 Ocular syphilis. (A) Roseolae; (B) old multifocal chorioretinitis; (C) acute posterior placoid chorioretinitis; (D) end-stage disease

(Courtesy of J Salmon – fig. B; C de A Garcia – fig. C)

Penicillin-allergic patients can be treated with oral tetracycline or erythromycin 500 mg q.i.d. for 30 days.

Lyme disease

Brucellosis

Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis

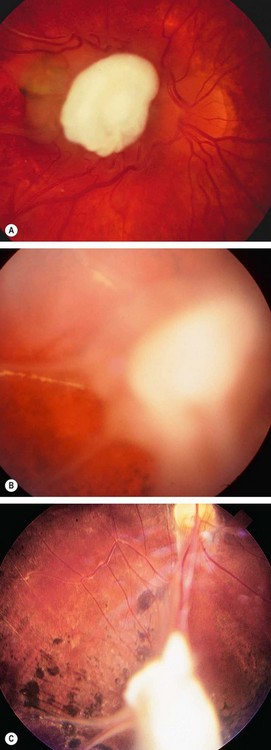

Fig. 11.57 Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis. (A) Fibrinous anterior uveitis; (B) retinal infiltrates

Table 11.6 Comparison of exogenous and endogenous endophthalmitis

| Postoperative | Metastatic | |

|---|---|---|

| Ocular cultures | Yes | Yes |

| Blood culture | No | Yes |

| Systemic investigation | No | Yes |

| Topical antibiotic | Yes | Yes |

| Systemic antibiotic | Oral fluoroquinolone | Intravenous (various) |

| Intravitreal antibiotics | Yes | Yes |

| Corticosteroid | Yes | Uncertain value |

| Visual outcome | 70% > 6/60 | 70% < count fingers |

| Mortality | None | 10% |

Cat-scratch disease

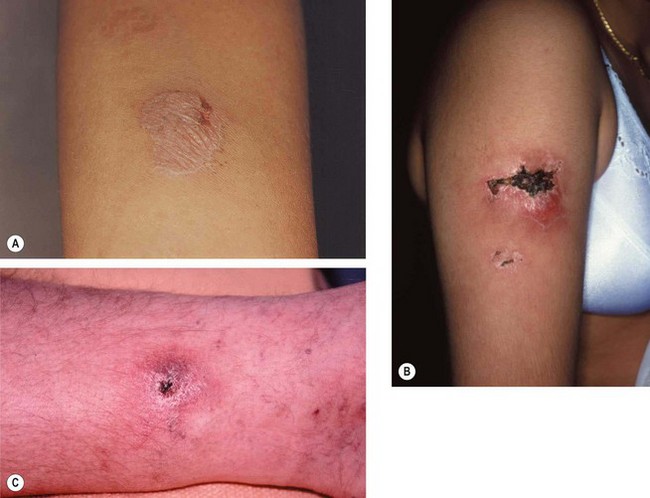

Fig. 11.58 Cat-scratch disease. (A) Ulcerated papule on the cheek caused by a cat scratch 2 weeks previously, and enlargement of submandibular lymph nodes; (B) line of papules on the forearm of another patient at the site of a cat scratch; (C) marked enlargement of the ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes

(Courtesy of BJ Zitelli and HW Davis, from Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis, Mosby 2002)

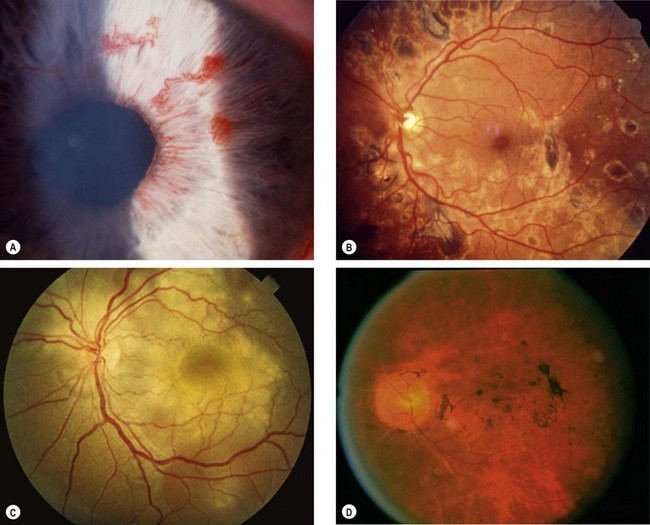

Leprosy

Fig. 11.59 Lepromatous leprosy. (A) Leonine facies; (B) ‘claw hand’ due to motor neuropathy; (C) loss of digits due to sensory neuropathy

(Courtesy of RT Emond, PD Welsby and HA Rowland, from Colour Atlas of Infectious Diseases, Mosby 2003 – figs A and B; CD Forbes and WF Jackson, from Color Atlas and Text of Clinical Medicine, Mosby 2003 – fig. C)

White Dot Syndromes

White dot syndromes are caused by inflammation at the level of the choriocapillaris resulting in non-perfusion and secondary changes involving the choroid and outer retina.

Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome

Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome (MEWDS) is an uncommon, idiopathic, usually unilateral, self-limiting disease with a female preponderance. About one-third of patients have a preceding viral-like illness.

Although uncommon, it is important to be aware of MEWDS because the subtle signs may be overlooked and a misdiagnosis made of a more serious disorder such as retrobulbar neuritis.

Acute idiopathic blind spot enlargement syndrome

Acute idiopathic blind spot enlargement syndrome is a rare, self-limiting, condition which seems to exclusively affect women.

Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy

Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE) is an uncommon, idiopathic, usually bilateral condition. It affects both sexes equally and is associated with HLA-B7 and HLA-DR2. In about one-third of patients it follows a flu-like illness.

Multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis

Multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis is an uncommon, usually bilateral, chronic/recurrent, frequently asymmetrical disease that predominantly affects myopic females.

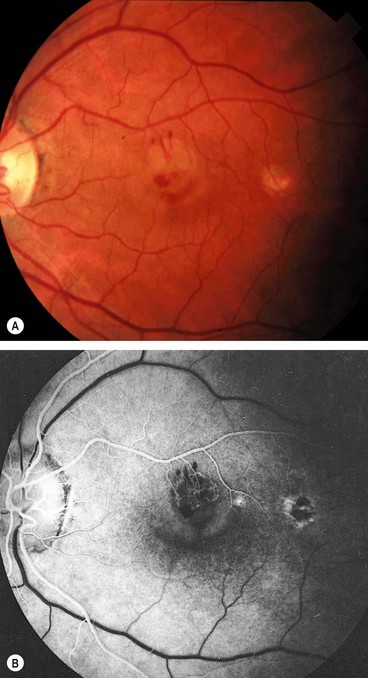

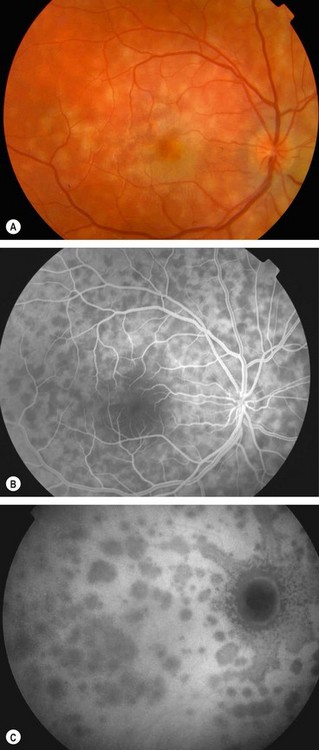

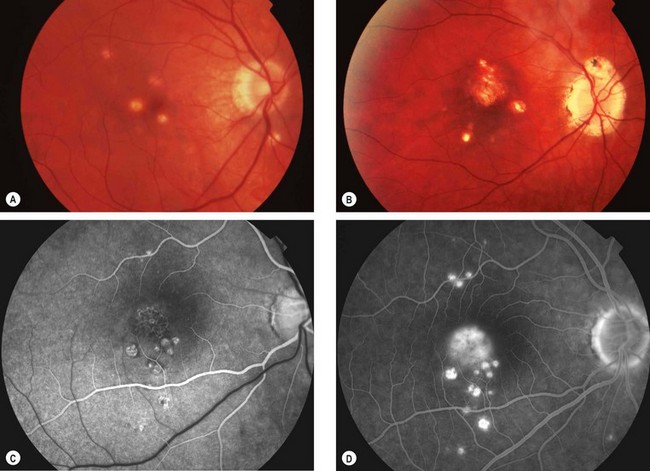

Fig. 11.63 Choroidal neovascularization in multifocal choroiditis with uveitis. (A) Inactive lesions; (B) early venous phase fluorescein angiogram shows variable hypo- and hyperfluorescence of the lesions and lacy hyperfluorescence at the fovea associated with choroidal neovascularization; (C) late phase shows hyperfluorescence at the fovea due to leakage from choroidal neovascularization

(Courtesy of Moorfields Eye Hospital)

Punctate inner choroidopathy

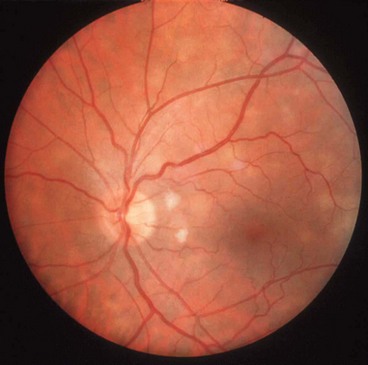

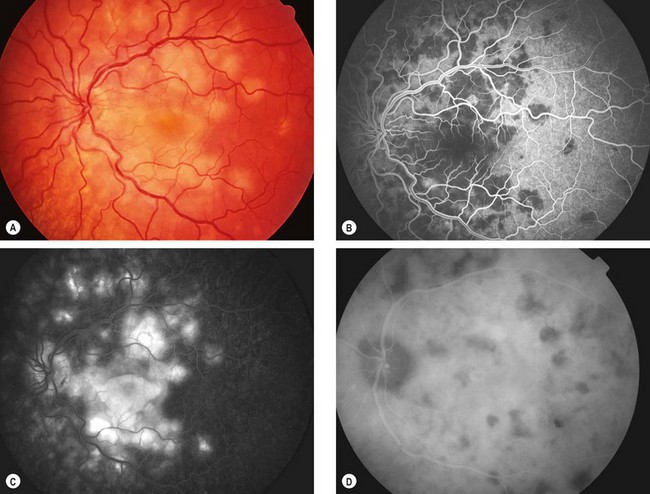

Fig. 11.64 Punctate inner choroidopathy. (A) Active stage; (B) inactive disease; (C) FA arterial phase shows several hyperfluorescent spots with hypofluorescent edges inferior to the fovea and mild lacy hyperfluorescence at the fovea due to choroidal neovascularization; (D) late phase shows more hyperfluorescent spots and intense hyperfluorescence at the fovea due to leakage from choroidal neovascularization

(Courtesy of M Westcott – figs C and D)

Serpiginous choroidopathy

Serpiginous choroidopathy is an uncommon chronic/recurrent disease which is usually bilateral, although the extent of involvement is frequently asymmetrical. It is associated with HLA-B7 and affects men more frequently than women.

Progressive subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome

Progressive subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome is a rare, idiopathic, chronic bilateral condition which typically affects healthy women who are frequently myopic.

Acute macular neuroretinopathy

Acute macular neuroretinopathy is a rare, self-limiting condition that typically affects healthy females. The disease may affect one or both eyes and may be preceded by a flu-like illness.

Acute zonal occult outer retinopathy

The acute zonal outer retinopathies (AZOR) are a group of very rare, idiopathic syndromes characterized by acute onset of loss of one or more zones of visual field. Acute zonal occult outer retinopathy (AZOOR) is the most common of the AZOR syndromes. The entity shares clinical similarities with other conditions in this group in that it typically affects young myopic females, some of whom have an antecedent viral-like illness.

Primary stromal choroiditis

In primary stromal choroiditis the inflammatory focus, which is usually granulomatous, develops at the level of the stroma and is associated with inflammation of the larger non-fenestrated stromal vessels.

Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome

Pathogenesis

Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada (VKH) syndrome is an idiopathic multisystem autoimmune disease featuring inflammation of melanocyte-containing tissues such as the uvea, ear and meninges.

VKH predominantly affects Hispanics, Japanese and pigmented individuals. In different racial groups the disease is associated with HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4, suggesting a common immunogenic predisposition.

In practice, VKH can be subdivided into Vogt–Koyanagi disease, characterized mainly by skin changes and anterior uveitis, and Harada disease, in which neurological features and exudative retinal detachments predominate. Possible trigger factors include cutaneous injury or a viral infection which may lead to sensitization of melanocytes. CSF analysis shows pleocytosis with predominant small lymphocytes in about 80% of patients within 1 week and 97% within 3 weeks of disease onset.

Phases

Table 11.7 Modified diagnostic criteria for VKH syndrome

In complete VKH, criteria 1–5 must be present.

In incomplete VKH, criteria 1–3 and either 4 or 5 must be present.

In probable VKH (isolated ocular disease), criteria 1–3 must be present.

Uveitis

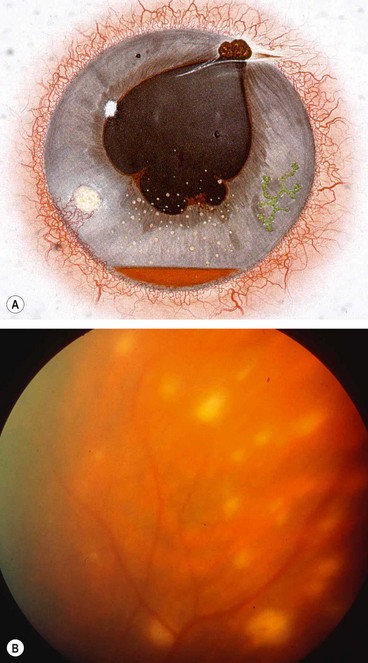

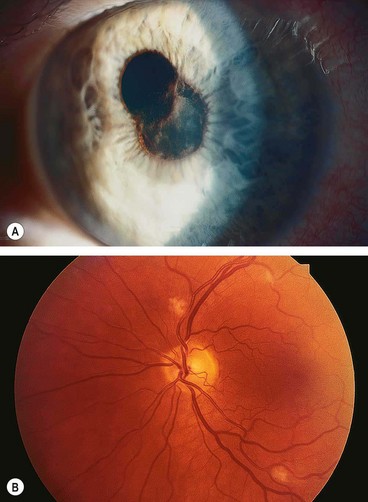

Sympathetic ophthalmitis

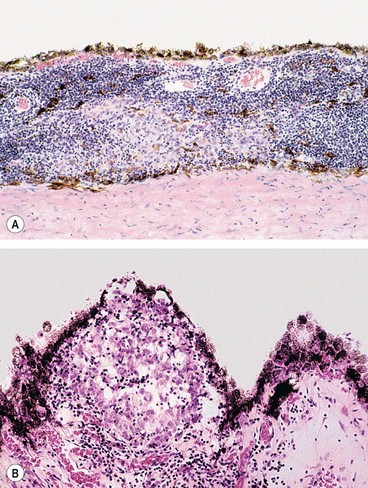

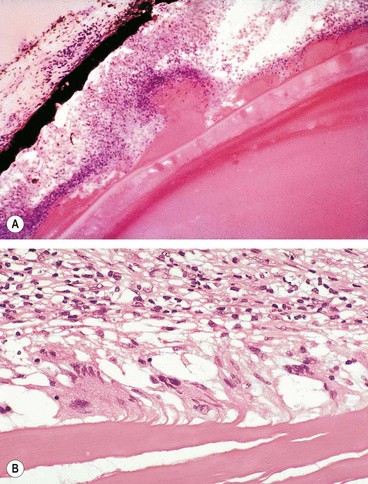

Fig. 11.72 Histology of sympathetic ophthalmitis. (A) Infiltration of the choroid by lymphocytes and scattered aggregations of epithelioid cells, many of which contain fine granules of melanin; (B) Dalen–Fuchs nodule – a granuloma situated between Bruch membrane and the retinal pigment epithelium

(Courtesy of J Harry)

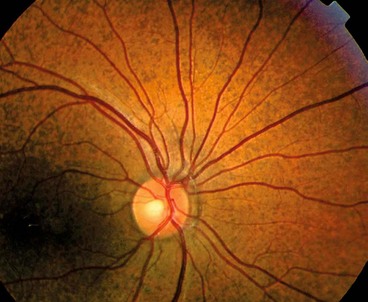

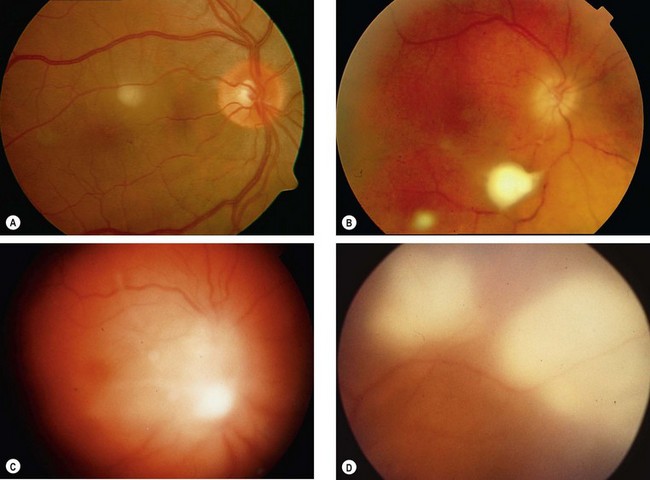

Birdshot retinochoroidopathy

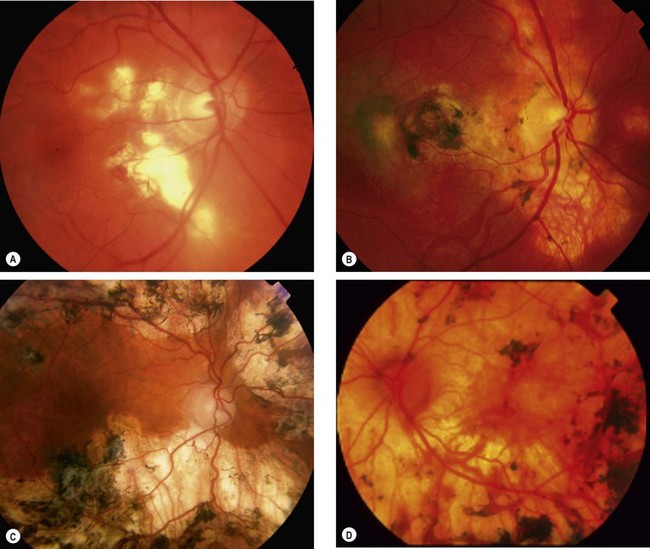

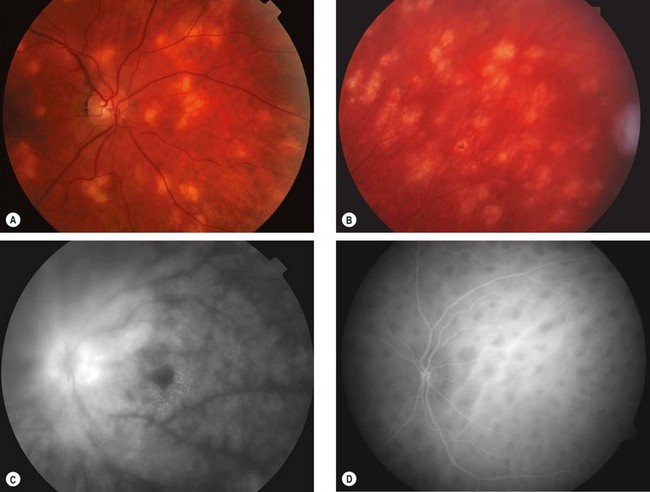

Fig. 11.74 Birdshot chorioretinopathy. (A) Active stage; (B) inactive lesions; (C) late phase fluorescein angiogram shows disc hyperfluorescence and cystoid macular oedema; (D) early phase indocyanine green angiogram shows numerous hypofluorescent lesions

(Courtesy of C Pavésio – fig. B; P Gili – fig. C)

Miscellaneous anterior uveitis

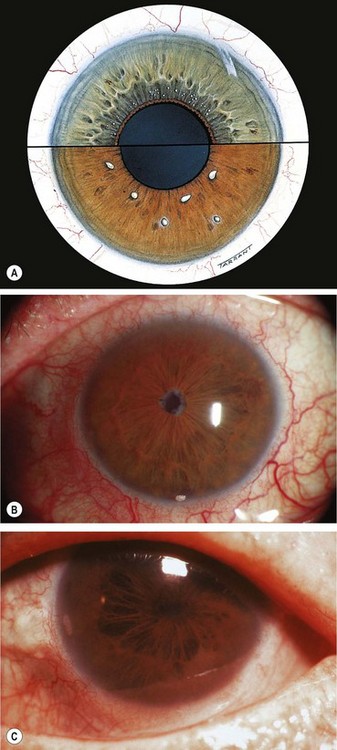

Fuchs uveitis syndrome

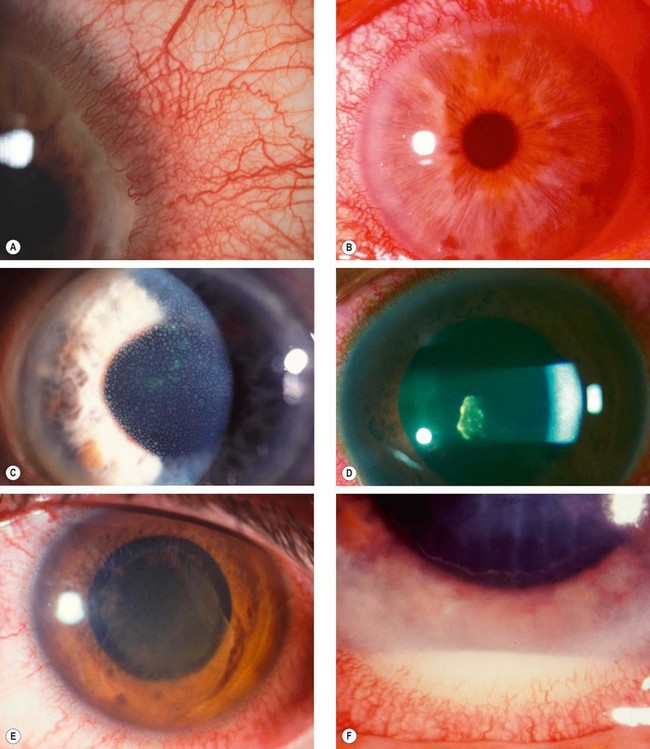

Fig. 11.75 Fuchs uveitis syndrome. (A) Keratic precipitates; (B) small nodules at the pupil border and in the stroma; (C) stromal iris atrophy rendering the sphincter pupillae prominent, and small pupil border nodules; (D) posterior pigment layer atrophy seen on retroillumination; (E) heterochromia and left cataract; (F) angle vessels and small peripheral anterior synechiae

(Courtesy of C Pavésio – fig. A)

Topical steroids are generally ineffective and mydriatics unnecessary because of lack of posterior synechiae.

Table 11.8 Other causes of heterochromia iridis

Lens-induced uveitis

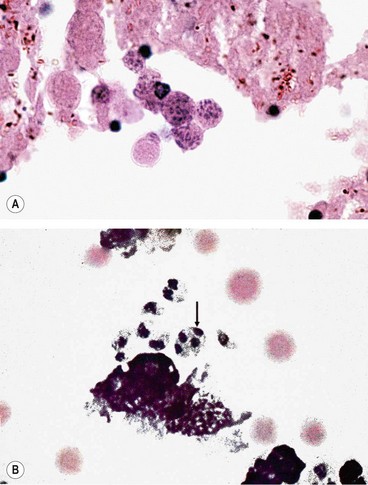

Lens-induced uveitis is triggered by an immune response to lens proteins following rupture of the lens capsule, which may be due to trauma or incomplete cataract extraction (Fig. 11.76).

Fig. 11.76 Lens-induced uveitis. (A) Escaping lens material producing an inflammatory reaction; (B) giant cells in relation to extracapsular material

(Courtesy of J Harry and G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2001)

Phacoanaphylactic endophthalmitis

Phacogenic non-granulomatous uveitis

Miscellaneous posterior uveitis

Acute retinal pigment epitheliitis

Acute retinal pigment epitheliitis (Krill disease) is a rare, idiopathic, self-limiting condition of the RPE that is unilateral in 75% of cases.

Acute idiopathic maculopathy

Acute idiopathic maculopathy is a very rare, self-limiting condition which is most frequently unilateral and may be preceded by a flu-like illness.

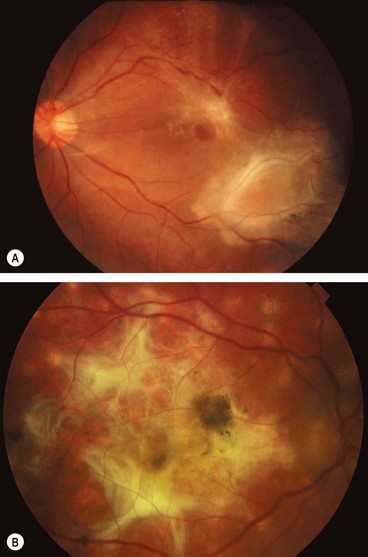

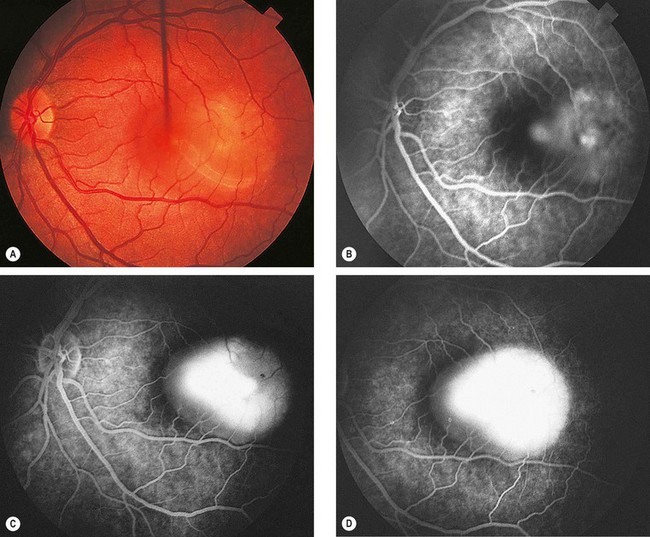

Fig. 11.78 Acute idiopathic maculopathy. (A) Detachment of the sensory retina at the macula with an irregular outline; (B) FA early phase shows mild irregular subretinal hyperfluorescence; (C) mid-venous phase shows extensive hyperfluorescence due to staining of the subretinal fluid; (D) late venous phase shows further staining of subretinal fluid

(Courtesy of S Milewski)

Acute multifocal retinitis

Acute multifocal retinitis is a very rare, frequently bilateral, self-limiting condition that typically affects healthy individuals. It may be preceded by a flu-like illness, usually 1–2 weeks before the onset of the visual symptoms. It has been postulated by some that acute multifocal retinitis may be an unusual presentation of cat-scratch disease.

Solitary idiopathic choroiditis

Solitary idiopathic choroiditis is a distinct clinical entity that may give rise to diagnostic problems as it can simulate other pathology.

Frosted branch angiitis

Frosted branch angiitis (FBA) describes a characteristic fundus picture, usually bilateral, which may represent a specific syndrome (primary form) or a common immune pathway in response to multiple infective agents. Secondary FBA may be associated with infectious retinitis, most notably cytomegalovirus retinitis, but it may also occur in association with other conditions such as glomerulonephritis and central retinal vein occlusion. Primary FBA is rare and typically affects children and young adults.

Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitis syndrome

Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitis syndrome is a rare entity that typically affects one or both eyes of healthy young women.

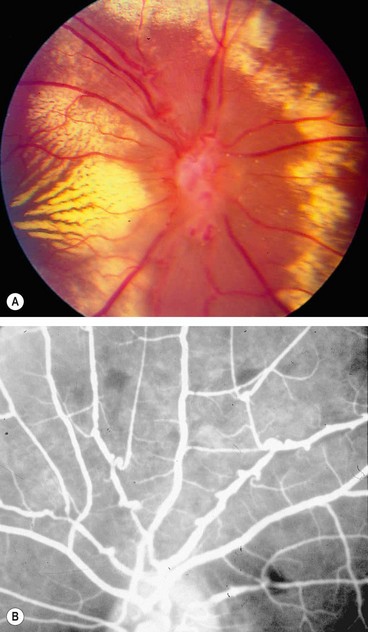

Fig. 11.81 Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitis syndrome. (A) Circinate pattern of hard exudates surrounding the disc. There is also venous irregularity and obscuration of the optic nerve head; (B) FA shows multiple aneurysms at arteriolar bifurcations and marked variation in arteriolar calibre

(Courtesy of J Donald Gass, from Stereoscopic Atlas of Macular Diseases, Mosby 1997 – fig. A; RF Spaide, from Diseases of the Retina and Vitreous, WB Saunders 1999 – fig. B)