Complementary and Alternative Therapies

• Differentiate between complementary and alternative therapies.

• Describe the clinical applications of relaxation therapies.

• Discuss the relaxation response and its effect on somatic ailments.

• Identify the principles and effectiveness of imagery, meditation, and breathwork.

• Describe the purpose and principles of biofeedback.

• Describe the methods of and the psychophysiological responses to therapeutic touch.

• Explain the scope of practice of chiropractic therapy.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

The general health of North American people has steadily improved over the course of the last century as evidenced by lower mortality rates and increased life expectancies. Changes in science and medicine have provided the knowledge and technology to successfully alter the course of many illnesses. Despite the success of allopathic medicine (conventional western medicine), many conditions such as chronic back and neck pain, arthritis, gastrointestinal problems, allergies, headache, and anxiety are sometimes difficult to treat. As a result, more patients are exploring alternative methods to relieve their symptoms. Researchers estimate that up to 75% of patients seek care from their primary care practitioners for stress, pain, and health conditions for which there are no known causes or cures (Rakel and Faass, 2006). Although allopathic medicine is quite effective in treating numerous physical ailments (e.g., bacterial infections, structural abnormalities, and acute emergencies), it is generally less effective in decreasing stress-induced illnesses, managing chronic disease, caring for the emotional and spiritual needs of individuals, and improving quality of life and general well-being.

The number of patients seeking unconventional treatments has risen considerably over the past decade. The most recent comprehensive national survey estimates that between 38.3% and 62.1% of the U.S. population uses complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) (Barnes et al., 2008). In part this increase is caused by (1) a desire for less invasive, less toxic, “more natural” treatments; (2) lack of satisfaction with allopathic treatments; (3) an increasing desire by patients to take a more active role in their treatment process; (4) beliefs that a combination of treatments (allopathic and complementary) result in better overall results; (5) the increased number of research articles in journals such as Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine and the Journal of Holistic Nursing; and (6) beliefs and values that are consistent with an approach to health that incorporates the mind, body, and spirit or a holistic approach (Koithan, 2009).

Complementary and Alternative Approaches to Health

The National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NIH/NCCAM, 2010b) defines CAM as “a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine.” Complementary therapies are therapies used in addition to conventional treatment recommended by the person’s health care provider. As the name implies, complementary therapies complement conventional treatments. Many of them such as therapeutic touch contain diagnostic and therapeutic methods that require special training. Others such as guided imagery and breathwork are easily learned and applied. Complementary therapies also include relaxation; exercise; massage; reflexology; prayer; biofeedback; hypnotherapy; creative therapies, including art, music, or dance therapy; meditation; chiropractic therapy; and herbs/supplements (Fontaine, 2005). Another term that is used to describe interventions used in this fashion, particularly by licensed health care providers, is integrative therapies (Kreitzer et al., 2009).

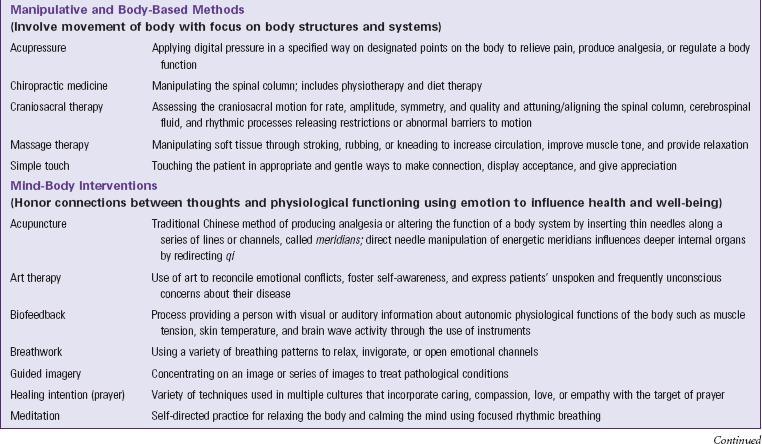

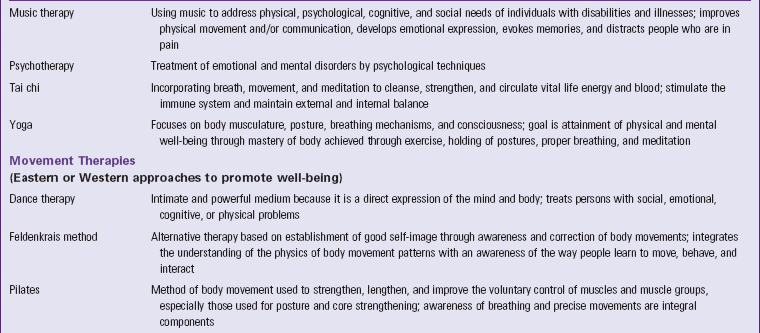

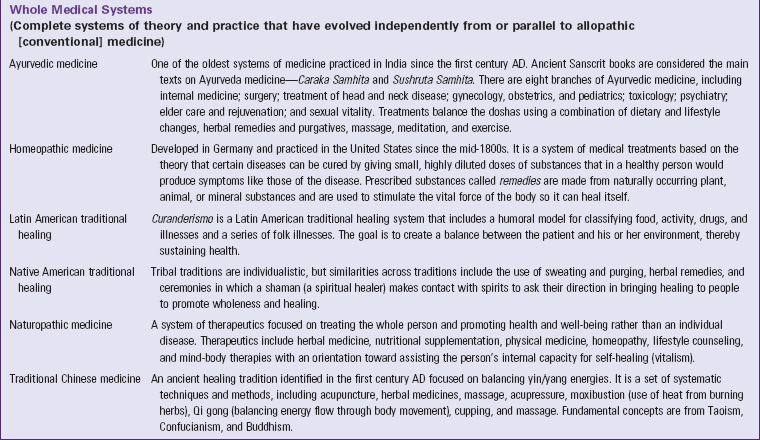

Alternative therapies may include the same interventions as complementary therapies; but they become the primary treatment, replacing allopathic medical care. For example, a person with chronic pain uses yoga to encourage flexibility and relaxation at the same time that nonsteroidal antiinflammatory or opioid medications are prescribed. Both sets of interventions are based on conventional pathophysiology and anatomy while acknowledging the mind-body connection that contributes to the physiological pain response. In this case yoga is used as a complementary intervention. However, another patient decides a meditative practice that includes yoga and other lifestyle changes is more helpful than an allopathic approach to chronic pain. This patient studies these practices more deeply, adhering to one of the many schools or traditions, and decides to use these practices as the primary approach to manage chronic pain. In this case yoga is an alternative treatment. Several therapies are always considered alternative because they are based on completely different philosophies and life systems than those used by allopathic medicine. These are identified by NIH/NCCAM as whole medical systems such as traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), Ayurveda, and various forms of traditional or folk medicine. Table 32-1 presents types of complementary and alternative therapies.

Because of the increased interest in complementary therapies, many institutions, including medical and nursing schools, have training programs that incorporate complementary and alternative therapy content into the curriculum. Some schools have integrative health care programs that allow health care consumers the opportunity to be treated by a team of providers consisting of both allopathic and complementary practitioners. More fully defined, integrative health care emphasizes the importance of the relationship between practitioner and patient; focuses on the whole person; is informed by evidence; and makes use of appropriate therapeutic approaches, health care professionals, and disciplines to achieve optimal health (Kreitzer et al., 2009).

Nurses have historically practiced in an integrative fashion; a review of nursing theory (see Chapter 4) reveals the values of holism, relational care, and informed practice. However, nursing has identified its practice as holistic rather than integrated. Holistic nursing regards and treats the mind-body-spirit of the patient. Nurses use holistic nursing interventions such as relaxation therapy, music therapy, touch therapies, and guided imagery. Such interventions affect the whole person (mind-body-spirit) and are effective, economical, noninvasive, nonpharmacological complements to medical care. Nurses use holistic interventions to augment standard treatments, replace interventions that are ineffective or debilitating, and promote or maintain health (Dossey and Keegan, 2009). The American Holistic Nurses Association maintains Standards of Holistic Nursing Practice, which defines and establishes the scope of holistic practice and describes the level of care expected from a holistic nurse (AHNA/ANA, 2007).

Increasing interest in CAM is evident in the increased number of publications on CAM topics in respected health care journals and the development of new journals that specifically focus on complementary and alternative therapies (e.g., Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine and Integrative Cancer Therapies). The ongoing mission of the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) supports the investigation of the benefits and safety of CAM interventions. Although the body of evidence about CAM is growing, limited data make it difficult to establish the specific benefits of complementary therapies. Reasons are varied but reflect the growing and developing nature of the science. Therefore nurses should weigh the risk and benefits of each intervention and consider the following when recommending complementary therapies: (1) the history of each therapy (many have been used by cultures for thousands of years to support health and ameliorate suffering); (2) nursing’s history and experience with a particular therapy; (3) other forms of evidence reporting outcomes and safety data, including case study and qualitative research; and (4) the cultural influences and context for certain patient populations.

This chapter discusses several types of complementary and alternative therapies, including a description, the clinical applications, and the limitations of each therapy. The therapies are organized into two categories. The first are nursing-accessible therapies that you can begin to learn and apply in patient care. The second category includes training-specific therapies such as chiropractic therapy or acupressure that a nurse cannot perform without additional training and/or certification.

Nursing-Accessible Therapies

Some complementary therapies and techniques are general in nature and use natural processes (e.g., breathing, thinking and concentration, presence, movement) to help people feel better and cope with both acute and chronic conditions (Box 32-1). You need to learn about these techniques and incorporate them as a part of your independent nursing practice with patients (AHNA/ANA, 2007). Assess your patients and obtain their permission before using complementary therapies. In addition, conduct ongoing outcomes assessment and evaluation of your patients’ responses to the interventions. Sometimes changes to physician-prescribed therapies, such as medication doses, are needed when complementary therapies alter physiological responses and lead to therapeutic responses.

Complementary therapies teach individuals ways in which to change their behavior to alter physical responses to stress and improve symptoms such as muscle tension, gastrointestinal discomfort, pain, or sleep disturbances. Active involvement is a primary principle for these therapies; individuals achieve better responses if they commit to practice the techniques or exercises daily. Therefore to achieve effective outcomes, therapeutic strategies need to be matched with an individual’s lifestyle, his or her beliefs and values, and his or her treatment preferences.

Relaxation Therapy

People face stressful situations in everyday life that evoke the stress response (see Chapter 37). The mind varies the biochemical functions of the major organ systems in response to feedback. Thoughts and feelings influence the production of chemicals (i.e., neurotransmitters, neurohormones, and peptides) that circulate throughout the body and convey messages via cells to various systems within the body. The stress response is a good example of the way in which systems cooperate to protect an individual from harm. Physiologically the cascade of changes associated with the stress response causes increased heart and respiratory rates; tightened muscles; increased metabolic rate; and a general sense of foreboding, fear, nervousness, irritability, and negative mood. Other physiological responses include elevated blood pressure; dilated pupils; stronger cardiac contractions; and increased levels of blood glucose, serum cholesterol, circulating free fatty acids, and triglycerides. Although these responses prepare a person for short-term stress, the effects on the body of long-term stress sometimes include structural damage and chronic illness such as angina, tension headaches, cardiac arrhythmias, pain, ulcers, and atrophy of the immune system organs (Dossey and Keegan, 2009).

The relaxation response is the state of generalized decreased cognitive, physiological, and/or behavioral arousal. Relaxation also involves arousal reduction. The process of relaxation elongates the muscle fibers, reduces the neural impulses sent to the brain, and thus decreases the activity of the brain and other body systems. Decreased heart and respiratory rates, blood pressure, and oxygen consumption and increased alpha brain activity and peripheral skin temperature characterize the relaxation response. The relaxation response occurs through a variety of techniques that incorporate a repetitive mental focus and the adoption of a calm, peaceful attitude (Snyder and Lindquist, 2010).

Relaxation helps individuals develop cognitive skills to reduce the negative ways in which they respond to situations within their environment. Cognitive skills include the following:

• Focusing (the ability to identify, differentiate, maintain attention on, and return attention to simple stimuli for an extended period)

• Passivity (the ability to stop unnecessary goal-directed and analytic activity)

• Receptivity (the ability to tolerate and accept experiences that are uncertain, unfamiliar, or paradoxical).

The long-term goal of relaxation therapy is for people to continually monitor themselves for indicators of tension and consciously let go and release the tension contained in various body parts.

Progressive relaxation training teaches the individual how to effectively rest and reduces tension in the body. The person learns to detect subtle localized muscle tension sequentially, one muscle group at a time (e.g., the upper arm muscles, the forearm muscles). In doing so the individual learns to differentiate between high-intensity tension (strong fist clenching), very subtle tension, and relaxation (Dossey and Keegan, 2009). He or she practices this activity using different muscle groups. One active progressive relaxation technique involves the use of slow, deep abdominal breathing while tightening and relaxing an ordered succession of muscle groups, focusing on the associated bodily sensations while letting go of extraneous thoughts. When guiding a patient, you may decide to begin with the muscles in the face, followed by those in the arms, hands, abdomen, legs, and feet. Conversely you may also guide a patient to tense and relax muscles, beginning with the feet and working up the body.

The goal of passive relaxation is to still the mind and body intentionally without the need to tighten and relax any particular body part. One effective passive relaxation technique incorporates slow, abdominal breathing exercises while imagining warmth and relaxation flowing through specific body parts such as the lungs or hands. Passive relaxation is useful for persons for whom the effort and energy expenditure of active muscle contracting leads to discomfort or exhaustion.

Clinical Applications of Relaxation Therapy

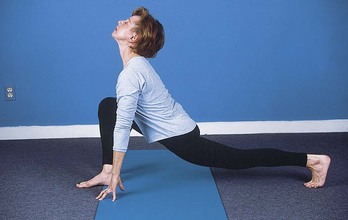

Research shows relaxation techniques effectively lower blood pressure and heart rate, decrease muscle tension, improve well-being, and reduce symptom distress in persons experiencing a variety of situations (e.g., complications from medical treatments, chronic illness, or loss of a significant other) (Bloch et al., 2010; Kwekkeboom et al., 2008). Research also indicates that relaxation, alone or in combination with imagery, yoga (Fig. 32-1), and music, reduces pain and anxiety while improving well-being (Schmidt et al., 2008; Weeks and Nilsson, 2010). Other benefits of relaxation include the reduction of hypertension (Dickinson et al., 2008), depression (Jorm et al., 2008), and menopausal symptoms, including vasomotor responses, insomnia, mood, and musculoskeletal pain (Innes et al., 2010).

Relaxation enables individuals to exert control over their lives. Some experience a decreased feeling of helplessness and a more positive psychological state overall. Relaxation also reduces workplace stress on nursing units. For example, deep-breathing exercises, centering, and focusing attention often lead to improved staff satisfaction, staff relationships and communication, and workload perceptions (Clarke et al., 2009). Nursing units that incorporate relaxation activities into daily routines experience reduced turnover and improved patient satisfaction scores (Zborowsky and Kreitzer, 2009).

Limitations of Relaxation Therapy

During relaxation training individuals learn to differentiate between low and high levels of muscle tension. During the first months of training sessions, when the person is learning how to focus on body sensations and tensions, there are reports of increased sensitivity in detecting muscle tension. Usually these feelings are minor and resolve as the person continues with the training. However, be aware that on occasion some relaxation techniques result in continued intensification of symptoms or the development of altogether new symptoms (Dossey and Keegan, 2009).

An important consideration when choosing any type of relaxation technique is the physiological and psychological status of the individual. Some patients with advanced disease such as cancer or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) seek relaxation training to reduce their stress response. However, techniques such as active progressive relaxation training require a moderate expenditure of energy, which often increases fatigue and limits an individual’s ability to complete relaxation sessions and practice. Therefore active progressive relaxation is not appropriate for patients with advanced disease or those who have decreased energy reserves. Passive relaxation or guided imagery is more appropriate for these individuals.

Meditation and Breathing

Meditation is any activity that limits stimulus input by directing attention to a single unchanging or repetitive stimulus so the person is able to become more aware of self (Snyder and Lindquist, 2010). It is a general term for a wide range of practices that involve relaxing the body and stilling the mind. The root word, meditari, means to consider or pay attention to something. Although the meditation has its roots in eastern religious practices (Hindu, Buddhism, and Taoism), conventional health care practitioners began to recognize its healing potential in the early 1970s (Snyder and Lindquist, 2010). According to Benson (1975), the four components of meditation are (1) a quiet space, (2) a comfortable position, (3) a receptive attitude, and (4) a focus of attention. He described meditation as a process that anyone can use to calm down; cope with stress; and, for those with spiritual inclinations, feel one with God or the universe.

Meditation is different from relaxation; the purpose of meditation is to become “mindful,” increasing our ability to live freely and escape destructive patterns of negativity. Meditation is self-directed; it does not necessarily require a teacher and can be learned from books or audiotapes (Kabat-Zinn, 2005). Most meditation techniques involve slow, relaxed, deep, abdominal breathing that evokes a restful state, lowers oxygen consumption, reduces respiratory and heart rates, and reduces anxiety (Chiesa and Serretti, 2010).

Clinical Applications of Meditation

Several recent studies support the clinical benefits of meditation. For example, meditation reduces overall systolic and diastolic blood pressures and significantly reduces hypertensive risk (Nidich et al., 2009). It also successfully reduces relapses in alcohol treatment programs (Garland et al., 2010). Patients with cancer who use mindfulness-based cognitive therapies often experience less depression, anxiety, and distress and report an improved quality of life (Foley et al., 2010). Patients suffering from posttraumatic stress disorders and chronic pain also benefit from mindfulness meditation (Kimbrough et al., 2010). In addition, meditation increases productivity, improves mood, increases sense of identity, and lowers irritability (Dossey and Keegan, 2009).

Considerations for the appropriateness of meditation include the person’s degree of self-discipline; it requires ongoing practice to achieve lasting results. Most meditation activities are easy to learn and do not require memorization or particular procedures. Patients typically find mindfulness and meditation self-reinforcing. The peaceful, positive mental state is usually pleasurable and provides an incentive for individuals to continue meditating.

Limitations of Meditation

Although meditation contributes to improvement in a variety of physiological and psychological ailments, it is contraindicated for some people. For example, a person who has a strong fear of losing control will possibly perceive it as a form of mind control and thus will be resistant to learning the technique. Some individuals also become hypertensive during meditation and require a much shorter session than the average 15- to 20-minute session.

Meditation may also increase the effects of certain drugs. Therefore monitor individuals learning meditation closely for physiological changes with respect to their medications. Prolonged practice of meditation techniques sometimes reduces the need for antihypertensive, thyroid-regulating, and psychotropic medications (e.g., antidepressants and anti-anxiety agents). In these cases, adjustment of the medication is necessary.

Imagery

Imagery or visualization is a mind-body therapy that uses the conscious mind to create mental images to stimulate physical changes in the body, improve perceived well-being, and/or enhance self-awareness. Frequently imagery, combined with some form of relaxation training, facilitates the effect of the relaxation technique. Imagery is self-directed, in which individuals create their mental images, or guided, during which a practitioner leads an individual through a particular scenario (Dossey and Keegan, 2009). When guiding an imagery exercise, direct the patient to begin slow abdominal breathing while focusing on the rhythm of breathing. Then direct the patient to visualize a specific image such as ocean waves coming to shore with each inspiration and receding with each exhalation. Next instruct the patient to take notice of the smells, sounds, and temperatures that he or she is experiencing. As the imagery session progresses, instruct the patient to visualize warmth entering the body during inspiration and tension leaving the body during exhalation. Individualize imagery scenarios for each patient to ensure that the image does not evoke negative memories or feelings.

Imagery often evokes powerful psychophysiological responses such as alterations in gastric secretions, body chemistry, internal and superficial blood flow, wound healing, and heart rate/heart rate variability (Pincus and Sheikh, 2009). Although most imagery techniques involve visual images, they also include the auditory, proprioceptive, gustatory, and olfactory senses. An example of this involves visualizing a lemon being sliced in half and squeezing the lemon juice on the tongue. This visualization produces increased salivation as effectively as the actual event. People typically respond to their environment according to the way they perceive it and by their own visualizations and expectancies. Therefore you need to individualize imagery for each patient (Snyder and Lindquist, 2010).

Creative visualization is one form of self-directed imagery that is based on the principle of mind-body connectivity (i.e., every mental image leads to physical or emotional changes) (Gawain, 2008). Box 32-2 lists patient teaching strategies for creative visualization.

Clinical Applications of Imagery

Imagery has applications in a number of pediatric and adult patient populations. For example, it helps control or relieve pain, decrease nightmares, and improve sleep (Pincus and Sheikh, 2009). It also aids in the treatment of chronic conditions such as asthma, cancer, sickle cell anemia, migraines, autoimmune disorders, atrial fibrillation, functional urinary disorders, menstrual and premenstrual syndromes, gastrointestinal disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome and ulcerative colitis, and rheumatoid arthritis (Snyder and Lindquist, 2010).

Limitations of Imagery

Imagery is a behavioral intervention that has relatively few side effects (Roffe, Schmidt, and Ernst, 2005). Yet increased anxiety and fear sometimes occur when imagery is used to treat posttraumatic stress disorders and social anxiety disorders (Cook et al., 2010). Some patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma experience increased airway constriction when using guided imagery (Reed, 2007). Thus you need to closely monitor patients when beginning this therapy.

Training-Specific Therapies

Training-specific therapies are CAM treatments that nurses administer only after completing a specific course of study and training. These therapies require postgraduate certificates or degrees indicating completion of additional education and training, national certification, or additional licensure beyond the registered nurse (RN) to practice and administer them. Several training-specific therapies (e.g., biofeedback and acupuncture) are very effective and often recommended by western health care practitioners (Trigkilidas, 2010; Wheat and Larkin, 2010). However, others (e.g., homeopathy and naturopathy) have not been adequately studied, and their effectiveness in many conditions has been questioned (Borelli and Ernst, 2010). Although many of these complementary therapies elicit positive effects, all therapies carry some risk, particularly when used in conjunction with conventional medical therapies. Therefore you need advanced knowledge to effectively talk about them with patients and provide education about their safe use.

Biofeedback

Biofeedback is a mind-body technique that uses instruments to teach self-regulation and voluntary self-control over specific physiological responses. Electronic or electromechanical instruments measure, process, and provide information to patients about their muscle tension, cardiac activity, respiratory rates, brain-wave patterns, and autonomic nervous system activity. This information, or feedback, is given in physical, physiological, auditory, and/or visual feedback signals that increase a person’s awareness of internal processes that are linked to illness and distress. Biofeedback therapies are used to change thinking, emotions, and behaviors, which in turn support beneficial physiological changes, resulting in improved health and well-being. For example, patients connected to a biofeedback device sometimes hear a sound if their pulse rate or blood pressure increases out of their therapeutic zone. Practitioners then help patients interpret these sounds and use a variety of breathing, relaxation, and imaging exercises to gain voluntary control over their racing heart or their increasing systolic blood pressure (Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback Association, 2008).

Biofeedback is an effective addition to more traditional relaxation programs because it immediately demonstrates to patients their ability to control some physiological responses and the relationship among thoughts, feelings, and physiological responses. It helps individuals focus on and monitor specific body parts. Biofeedback helps patients control the physiological functions that are most difficult to control by providing immediate feedback about which stress relaxation behaviors work most effectively. Eventually patients notice positive physiological changes without the need for instrument feedback.

Clinical Applications of Biofeedback

Biofeedback in a variety of forms has application in numerous situations, with evidence supporting its effectiveness dating back to the 1980s. Recent systematic literature reviews suggest that it is helpful in stroke recovery, smoking cessation, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), epilepsy, headache disorders, and a variety of gastrointestinal and urinary tract disorders (Arns et al., 2009; Hollands et al., 2010). One of the most critical components of any behavioral program is adherence to the treatment regimen. Patients who are compliant have more positive results.

Limitations of Biofeedback

Although biofeedback produces effective outcomes in many patients, there are several precautions, particularly in those with psychological or neurological conditions. During biofeedback sessions repressed emotions or feelings for which coping is difficult sometimes surface. For this reason practitioners who offer biofeedback need to be trained in more traditional psychological methods or have qualified professionals available for referral. In addition, long-term use of biofeedback sometimes lowers blood pressure, heart rates, and other physiological parameters. As with other biobehavioral interventions, monitor patients closely to determine the need for medication adjustments.

Acupuncture

As a key component of TCM, acupuncture is one of the oldest practices in the world. In TCM, acupuncture is only one intervention used. When applied outside the whole system practice of TCM, acupuncture is viewed as a mind-body therapy and is called medical acupuncture. In the United States medical acupuncture is often provided as an individual treatment by conventionally trained physicians, nurses, chiropractors, dentists, and acupuncturists for many chronic conditions. Many states now have regulations and licensure requirements to practice as an acupuncturist.

Acupuncture regulates or realigns the vital energy (qi), which flows like a river through the body in channels that form a system of pathways called meridians. Twelve primary and eight secondary meridians are used by medical acupuncturists. An obstruction in these channels blocks energy flow in other parts of the body. Acupuncturists insert needles in specific areas along the channels called acupoints, through which the qi can be influenced and flow reestablished (Fig. 32-2). Application of heat or weak electrical currents enhances the effects of the needles (Fontaine, 2005).

FIG. 32-2 Acupuncture accesses the qi through specific points along the energy meridians of the body.

Clinical Applications of Acupuncture

Current evidence shows that acupuncture modifies the body’s response to pain and how pain is processed by central neural pathways and cerebral function (NIH/NCCAM, 2010a). Acupuncture is effective for low back pain, myofascial pain (e.g., temporomandibular joint disorder and trigeminal neuralgia), simple and migraine headaches, osteoarthritis, plantar heel pain, and chronic shoulder pain (Lee et al., 2010; Molsberger et al., 2010). It is also used to treat other problems such as sinusitis, gastrointestinal disorders, chronic pruritus, perimenstrual symptoms, menopausal symptoms, clinical depression, smoking, and other addictions with varying effectiveness (Scheid et al., 2010).

Limitations of Acupuncture

Acupuncture is a safe therapy when the practitioner has the appropriate training and uses sterilized needles. Although needle complications occur, they are rare if the practitioner takes appropriate steps to ensure the safety of the equipment and the patient. Reported complications include infections resulting from inadequately sterilized needles or those that are left in place for an extended length of time, broken needles, puncture of an internal organ, bleeding, fainting, seizures, and posttreatment drowsiness.

Caution is necessary when using acupuncture with pregnant patients and those who have a history of seizures, are carriers of hepatitis, or are infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Treatment is contraindicated in persons who have bleeding disorders and skin infections. Further, semipermanent needles should not be used with patients who have valvular heart disease because of the increased risk of infection. Electroacupuncture is not recommended for persons with a pacemaker and those who have cardiac arrhythmias or epilepsy or are pregnant (Fontaine, 2005).

Therapeutic Touch

Therapeutic touch (TT), developed in the 1970s, is one of the “touch therapies” identified by NCCAM. It affects the energy fields that surround and penetrate the human body with the conscious intent to help or heal (Dossey and Keegan, 2009). Other touch therapies include acupressure, healing touch (HT), reiki, and the M technique. Blending ancient eastern traditions with modern nursing theory, TT uses the energy of the provider to positively influence the patient’s energy field.

TT consists of placing the practitioner’s open palms either on or close to the body of a person (Fig. 32-3). It occurs in five phases: centering, assessing, unruffling, treating, and evaluating. To begin the practitioner centers physically and psychologically, becoming fully present in the moment and quieting outside distractions. Then the practitioner scans the body of the patient with the palms (roughly 2 to 6 inches [5 to 15 cm] from the body) from head to toe. While assessing the energetic biofield of the patient, the practitioner focuses on the quality of the qi, identifying areas of accumulated energetic tensions, uneasiness, sluggishness, or congestion that manifest as sensations of congestion, pressure, warmth, coolness, blockage, pulling or drawing, or static or tingling. The practitioner then redirects these energetic patterns to harmonize distressed areas or to stimulate movement of qi in areas that are stuck and congested. Using long downward strokes over the energy fields of the body, the practitioner touches the body or maintains the hands in a position a few inches away from the body. The final phase consists of evaluating the patient, reassessing the energy field to ensure that energy is flowing freely, and determining additional outcomes and responses to the treatment (Krieger, 1975, 1979).

FIG. 32-3 The practitioner intentionally directs interpersonal energy to facilitate the patient’s healing process during a therapeutic touch session.

Clinical Applications of Therapeutic Touch

The evidence supporting the effectiveness of TT is inconclusive, although it may be effective in treating pain in adults and children, dementia, trauma, and anxiety during acute and chronic illnesses (Jain and Mills, 2010). Box 32-3 summarizes the importance of touch in older adults.

Limitations of Therapeutic Touch

Although the use of TT causes very few complications or side effects, it is contraindicated in certain patient populations. For example, people who are sensitive to human interaction and touch (e.g., those who have been physically abused or have psychiatric disorders) often misinterpret the intent of the treatment and feel threatened and anxious by it. Other patients, including pregnant women, neonates, patients with cardiovascular and neurological instabilities, or patients who are dying, sometimes are sensitive to energy repatterning. Sessions with these populations need to be time limited and particularly gentle (Snyder and Lindquist, 2010).

Chiropractic Therapy

Chiropractic therapy, a manipulative or body-based therapy, was developed in 1895 in Iowa. Chiropractors graduate from well-established postbaccalaureate educational programs similar to medical schools. The central belief of the chiropractic profession is that body structure (primarily that of the spine and spinal cord) and the ability of the body to function normally are closely related. When the spine is misaligned, energy flow is impeded, and the innate healing abilities of the body are impaired. Chiropractic therapy aims to normalize the relationship between structure and function by a series of manipulations. Practitioners use their hands or a device to provide manipulation, which is the application of a controlled, sudden forceful movement to a joint, moving it beyond its passive range of motion. Often manipulations are combined with additional therapeutic modalities, including ice and heat, electrical stimulation, deep tissue massage, joint immobilization, lifestyle counseling, and medications.

Chiropractic care is a popular form of complementary therapy in the United States; 8.6% of the adult and 3% of the pediatric population visit chiropractors each year, representing almost 20 million health care visits (Barnes et al., 2008). Compared to other forms of complementary therapies, chiropractic care is often covered by insurance plans, including Medicare, Medicaid, state workers’ compensation plans, health maintenance organizations (HMOs), and private insurance plans. Licensure is regulated by individual state governments, and scopes of practice and prescriptive authority vary from state to state.

Clinical Applications of Chiropractic Therapy

The basic goals of chiropractic therapy focus on restoring structural and functional imbalances. Chiropractors believe that structure and function coexist with one another and that alterations or distortions in structure ultimately lead to abnormalities in function. A major structural problem that chiropractors treat is vertebral (neck/back) subluxation with its accompanying symptom of pain.

Chiropractic therapy improves acute pain and disability in some patients. This therapy is also sometimes effective over longer periods to reduce pain caused by acute and subacute low back pain and joint pain caused by osteoarthritis (Walker et al., 2010). Chiropractic care may also enhance the effects of conventional treatments in pediatric asthma (Kaminskyj et al., 2010). Chiropractic interventions are also used to treat headaches, dysmenorrhea, vertigo, tinnitus, and visual disorders (Hawk et al., 2010).

Limitations of Chiropractic Therapy

Although chiropractic therapies are safe for a variety of conditions, chiropractors do not treat several diseases or conditions with manipulation. Bone and joint infections require pharmaceutical or surgical intervention because the structural integrity of the bone is compromised if excessive force is used. Other contraindications include acute myelopathy, fractures, dislocations, rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoporosis.

Some risks are associated with chiropractic therapy. A variety of injuries, ranging in severity from mild adverse responses (e.g., mild transient headache, increased pain and stiffness) to more serious injuries (e.g., vertebral artery dissection), sometimes happen (Ernst, 2007). Degree and risk of injury depend on the type of manipulation performed, location of the manipulation (cervical spine is more susceptible to serious injury), overall health of the patient, and expertise of the provider. When educating patients about chiropractic care, you need to include educational and licensure credentials of qualified chiropractors, typical treatments, and possible complications.

Traditional Chinese Medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is a whole system of medicine that began as a primitive ethnic healing system approximately 3600 years ago. Chinese medicine views health as “life in balance,” which manifests as lustrous hair, a radiant complexion, engaged interactions, a body that functions without limitations, and emotional balance. Health promotion encourages healthy diet, moderate regular exercise, regular meditation/introspection, healthy family and social relationships, and avoidance of environmental toxins such as cigarette smoke.

Several concepts and principles guide the TCM system of assessment, diagnosis, and intervention. The most important of these is the concept of yin and yang, which represent opposing yet complementary phenomena that exist in a state of dynamic equilibrium. Examples are night/day, hot/cold, and shady/sunny. Yin represents shade, cold, and inhibition; whereas yang represents fire, light, and excitement. Yin also represents the inner part of the body, specifically the viscera, liver, heart, spleen, lung, and kidney; whereas yang represents the outer part, specifically the bowels, stomach, and bladder. Harmony and balance in every aspect of life are the keys to health, including yin/yang balance. Practitioners believe that disease occurs when there is an imbalance in these two paired opposites (Maciocia, 1989). Imbalance occurs as excess or deficiencies in three areas: external, internal, or neither internal nor external (Table 32-2). It ultimately leads to disruption of vital energy, qi, which then compromises the body-mind-spirit of the person, causing “disease.” Disruptions in qi along the meridians can be systematically evaluated and treated by TCM practitioners.

TABLE 32-2

Three Causes of Disease According to Traditional Chinese Medicine

| CAUSE OF DISEASE | INFLUENCES |

| Internal causes | Internal causes originate in emotions and affect different organs: anger (liver), joy (heart), fear (kidney), grief/sadness (lung), pensiveness/worry (spleen), and shock (heart/kidney). |

| External causes | Six “evils” primarily linked to weather and climate (wind, cold, fire, damp, summer heat, and dryness) are manifested as linked patterns such as wind-cold, wind-heat, fire-toxin. |

| Nonexternal, noninternal causes | Additional causes of disharmony include congenital weak constitutions (birth defects), trauma, overexertion, excessive sexual activity, poor quality diet, and parasites and poisons. |

TCM is an individualized treatment system based on a very specific assessment process. Practitioners use four methods to evaluate a patient’s condition: observing, hearing/smelling, asking/interviewing, and touching/palpating. In Chinese medicine outward manifestations reflect the internal environment. For example, the color, shape, and coating of the tongue reflect the general condition of the internal organs. The pulses provide information about the condition and balance of qi, blood, ying and yang, and internal organs. Therapeutic modalities include acupuncture, Chinese herbs, tui na massage, moxibustion (burning moxa, a cone or stick of dried herbs that have healing properties on or near the skin) cupping (placing a heated cup on the skin to create a slight suction), tai chi (originally a martial art that is now viewed as a moving meditation in which patients move their bodies slowly, gently, and with awareness while breathing deeply), qi gong (originally a martial art, now viewed as a series of carefully choreographed movements or gestures that are designed to promote and manipulate the flow of qi within the body), lifestyle modifications, and dietary changes.

Clinical Applications of Traditional Chinese Medicine

In spite of widespread use of TCM in Asia, evidence about its effectiveness is limited. Most research in this field focuses on the study of individual treatment components of TCM such as acupuncture and herbal therapies. However, some evidence shows that TCM is helpful in treating fibromyalgia (Cao et al., 2010) and in reducing pain and spasticity in children with cerebral palsy (Zhang et al., 2010).

Limitations of Traditional Chinese Medicine

TCM is not currently regulated in most states, although acupuncture is. The federal government recognizes the Accreditation Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (ACAOM) as responsible for accrediting schools that teach acupuncture and TCM, and approximately one third of the states that license acupuncture require graduation from an ACAOM-accredited school. The National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (NCCAOM) offers a certification examination for acupuncture and Chinese herbal and manipulative therapies. Refer patients requesting TCM to a qualified practitioner found at http://www.nccaom.org/find/index.html.

There is some concern about the safety of Chinese herbal treatments that are used in teas, remedies, and supplements. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not regulate, inspect, or ensure that the ingredients of these herbs are safe and without toxins. Recent reports about these products suggest that many Chinese herbs are contaminated with drugs, toxins, or heavy metals or that many ingredients may not be clearly listed or labeled. Further, these herbs can be very powerful, interacting with drugs and causing serious complications. When assessing a person using TCM, you always need to ask about the full complement of therapies, including the types of herbs that the patient is using. Some patients consider these as teas or dietary additives, powders, or supplements and not as over-the-counter medications.

Natural Products and Herbal Therapies

Researchers estimate that approximately 25,000 plant species are used medicinally throughout the world. It is the oldest form of medicine known to man, and archeological evidence suggests that herbal remedies have been used for over 60,000 years. Herbal medicines are a prominent part of health care among indigenous populations worldwide. In addition, interest in countries in which health care is primarily conventional allopathic medicine is also increasing (Snyder and Lindquist, 2010).

Nonvitamin, nonmineral natural products are used by almost 20% of the U.S. population to prevent disease and illness and to promote health and well-being (Barnes et al., 2008). A natural product is a chemical compound or substance produced by a living organism and includes herbal medicines (also known as botanicals), dietary supplements, vitamins, minerals, mycotherapies (fungi-based products), essential oils (aromatherapy), and probiotics. Many are sold over the counter as dietary supplements. The most frequently used products are garlic, Echinacea, saw palmetto, ginkgo biloba, cranberry, soy, ginseng, black cohosh, St. John’s wort, glucosamine, peppermint, fish oil/omega 3, soy, and milk thistle (Blumenthal et al., 2006).

Herbal medicines are not approved for use as drugs and are not regulated by the FDA. For this reason many are sold as foods or food supplements. The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (1994) allows companies to sell herbs as dietary supplements as long as there are no health claims written on their labels. Natural products in the United States are prepared primarily from plant materials. They are provided as tinctures or extracts, elixirs, syrups, capsules, pills, tablets, lozenges, powders, ointments or creams, drops, and suppositories.

Clinical Applications of Herbal Therapy

A number of herbs are safe and effective for a variety of conditions (Table 32-3). Nurses have used cranberry juice to treat urinary tract infections for decades. Research now supports the use of cranberry supplements to prevent urinary tract infections because cranberry molecules bind with the iron that bacteria need to grow and reproduce and substances in cranberry block adherence of bacteria to the walls of the bladder (Rossi et al., 2010). Chamomile is a plant substance that has been widely used in teas to promote sleep and relaxation and treat mild gastrointestinal disturbances and premenstrual symptoms. Clinical trials have recently found that chamomile may have modest benefits for people with mild-to-moderate generalized anxiety disorder (Amsterdam et al., 2009).

TABLE 32-3

Safe or Effective Herbs Determined by Non-U.S. Regulatory Authorities

| COMMON NAME AND USES | EFFECTS | POTENTIAL DRUG INTERACTIONS |

| Aloe | ||

| Skin disorders, including inflammation and acute injuries (used topically) | Acceleration of wound healing | Furosemide (Lasix) and loop diuretics |

| GI ulcerations, including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (taken orally) | Unknown mechanism, although there is a known laxative effect | May enhance the effects of laxatives when taken orally |

| Chamomile | ||

| Inflammatory diseases of GI and upper respiratory tracts | Antiinflammatory | Drugs that cause drowsiness (alcohol, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, narcotics, antidepressants) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | Calming agent | |

| Echinacea | ||

| Upper respiratory tract infections | Stimulant of immune system | Antirejection and other drugs that weaken immune system May interact with antiretrovirals and other drugs used in the treatment of HIV/AIDS |

| Feverfew | ||

| Wound healing | Antiinflammatory | Warfarin (Coumadin) and blood thinners |

| Arthritis | Inhibition of serotonin and prostaglandins | Aspirin and ibuprofen |

| Garlic | ||

| Elevated cholesterol levels | Inhibition of platelet aggregation | Warfarin and blood thinners |

| Hypertension | Saquinavir (Fortovase) and other anti-HIV drugs | |

| Ginger | ||

| Nausea and vomiting | Antiemetic | Warfarin and blood thinners |

| Aspirin and NSAIDs | ||

| Gingko biloba | ||

| Alzheimer’s disease and dementia | Memory improvement, although these effects are now in question given results in two recent clinical trials | Warfarin and anticoagulants Aspirin and NSAIDs |

| Ginseng | ||

| Age-related diseases | Increased physical endurance, improved immune function | Warfarin and anticoagulants Aspirin and NSAIDs MAO inhibitors |

| Licorice | ||

| GI disorders, including gastric ulcers and hepatitis C | Unknown | Corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive drugs Digoxin Antihypertensive drugs |

| Saw palmetto | ||

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia | Prevention of conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (needed for prostate cell multiplication) | Finasteride (Propecia) and antiandrogen drugs |

| Chronic pelvic pain | Unknown mechanism | None known |

| Valerian | ||

| Sleep disorders, mild anxiety and restlessness | Central nervous system depression | Barbiturates and other sleep medications Alcohol Antihistamines |

AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency disease; GI, gastrointestinal; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MAO, monoamine oxidase; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

Data from National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Herbs at a glance, 2010, accessed September 10, 2010, from http://nccam.nih.gov/health/herbsataglance.htm.

Limitations of Herbal Therapy

Simply because a product is “natural” does not make it “safe.” Although herbal medicines provide beneficial effects for a variety of conditions, a number of problems exist. Because they are not regulated, concentrations of the active ingredients vary considerably. Contamination with other herbs or chemicals, including pesticides and heavy metals, is also problematic. Not all companies follow strict quality control and manufacturing guidelines that set standards for acceptable levels of pesticides, residual solvents, bacterial levels, and heavy metals. For this reason, teach patients to purchase herbal medicines only from reputable manufacturers. Labels on herbal products need to contain the scientific name of the botanical, the name and address of the actual manufacturer, a batch or lot number, the date of manufacture, and the expiration date. Using natural products that have been verified by the U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) is another way to ensure product safety, quality, and purity. Look for the USP Verified Dietary Supplement mark on product labels when buying or recommending natural products.

Some herbs also contain toxic products that have been linked to cancer. Table 32-4 lists several unsafe herbs. Some herbal substances contain powerful chemicals. As with any other medication, examine herbs for interaction and compatibility with other prescribed or over-the-counter substances that are being used simultaneously.

TABLE 32-4

| COMMON NAME | EFFECTS | COMMENTS |

| Calamus (Indian type most toxic) | Fever Digestive aid |

Contains varying amounts of carcinogenic cis-isoasarone Documented cases of kidney damage and seizures with oral preparations |

| Chaparral | Anticancer Used for bronchitis in traditional healing systems (Native American and Hispanic folk medicine) Found in “natural” weight-loss products |

No proven efficacy Induces severe liver toxicity in some cases Severe uterine contractions |

| Coltsfoot | Antitussive | Contains carcinogenic pyrrolizidine alkaloids Hepatotoxic |

| Comfrey | Wound healing and acute injuries Used for antiinflammatory effects in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis |

Contains carcinogenic pyrrolizidine alkaloids May induce venoocclusive disease Hepatotoxic |

| Ephedra (ma huang) | Central nervous system stimulant Bronchodilator Cardiac stimulation Weight loss |

Unsafe for people with hypertension, diabetes, or thyroid disease Avoid consumption with caffeine |

| Life root | Menstrual flow stimulant | Hepatotoxic |

| Pokeweed | Antirheumatic Anticancer |

Do not use with children, but many websites state that it is safe with observation and monitoring and proper dosing; often used with folk remedies and in native American healing |

Data from National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Herbs at a glance, 2010, accessed September 10, 2010, from http://nccam.nih.gov/health/herbsataglance.htm; Natural Standard, 2011, accessed April 2, 2011, from http://naturalstandard.com/; US Pharmacopeia, 2011, accessed March 29, 2011 from http://www.usp.org/.

Nursing Role in Complementary and Alternative Therapies

The interest in complementary and alternative therapies continues to increase. Most people using and seeking information about these therapies are well educated and have a strong desire to actively participate in decision making about their health care. This increased interest comes not only from health care consumers but also from allopathic physicians who have increasing concerns that current conventional medicine is not meeting the needs of their patients. Many allopathic physicians do not refer their patients for complementary therapies because they are not familiar with them and have had little, if any, education and training about integrating these traditions with their practice. Many physicians have reservations about complementary therapies because they have not been tested appropriately in clinical trials in which other factors that influence the outcomes are strictly controlled.

In North America and Europe many professional groups are exploring the use of complementary and alternative therapies and facilitating and monitoring research in this area. Proposals put forth by several of the these groups include assessing the public use of complementary and alternative therapies, integrating CAM educational components in the curriculum for all health care programs, providing appropriate information to the public, and encouraging and facilitating communication between CAM and conventional care providers to improve public health and ensure the quality and safety of health care. For example, if health care providers want to recommend the best treatment option for each health condition, allopathic providers need to be aware of the evidence supporting complementary therapies and how to safely refer patients to complementary therapy providers. Contrastingly, complementary therapy providers need to participate in the research process, working with scientists to demonstrate the effectiveness of these therapies on patient outcomes within the more rigorous framework of western science. All providers, including nurses, need to encourage open, honest dialogue about the use of complementary and alternative therapies by patients and better understand the benefits of therapies that encourage active participation by their patients in preventing or managing illness rather than relying solely on surgery or drugs.

Integrative health care, a strategy that is gaining popularity, involves a multiple-practitioner group practice in which a patient seeks care simultaneously from more than one type of practitioner. Patients have the option to choose the type of practitioner that they believe is beneficial for their particular health problem. Patients who benefit from these groups are those who have chronic health problems that have historically been difficult to treat using traditional allopathic approaches such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, or chronic pain syndromes. A multiple-practitioner group practice represents a pluralistic and truly complementary health care system in which both alternative and allopathic practitioners work side-by-side to improve the well-being of their patients. The integrative approach is consistent with the holistic approach that nurses learn to practice. Nurses have the potential for becoming essential participants in this type of health care philosophy. Many nurses already practice the use of touch, relaxation techniques, imagery, and breathwork. Familiarize yourself with the evidence in each modality that you incorporate into your practice. Know which patient is most likely to benefit from each therapy, which complications might occur, and which precautions are needed when using these therapies.

In addition, you need enough knowledge to discuss complementary and alternative therapies with patients and help them make health care decisions. Always ask patients directly about their use of complementary therapies, including self-care activities such as yoga, meditation, or dietary supplements. Be knowledgeable about the evidence for different complementary therapies so you can make appropriate recommendations about which therapies are possibly useful for patients. Know about the different credentialing processes and how to refer patients to competent providers. Understand thoroughly the potential benefits and risks so information is clearly and fully disclosed. Be knowledgeable so you can give advice to patients about when to seek conventional care and when it is safe to consider complementary care services. For example, if a patient complains of right lower abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, be suspicious of appendicitis and recommend assessment by an allopathic physician. However, if the patient has a chronic gastrointestinal disorder and has a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome, the patient may benefit from relaxation and herbal therapy. Be aware of the safety precautions for each complementary therapy and incorporate these in your teaching plans. Finally understand your state Nurse Practice Act with regard to complementary therapies and practice only within the scope of these laws.

Nurses work very closely with their patients and are in the unique position of becoming familiar with the patient’s spiritual and cultural viewpoints. They are often able to determine which complementary therapies are more appropriately aligned with these beliefs and offer recommendations accordingly. Being knowledgeable about CAM therapies will help you provide accurate information to patients and other health care professionals.

Key Points

• Integrative health care programs use a multidisciplinary (both allopathic and complementary) treatment approach that provides holistic care to patients.

• The stress response is an adaptive response that allows individuals to respond to stressful situations.

• A chronic stress response is often maladaptive, leading to chronic muscle tension, mood changes, and immune changes.

• Complementary therapies require commitment and regular involvement by the patient to be most effective and have prolonged beneficial outcomes.

• Choose complementary therapies appropriately according to the patient’s functional status, belief or religious perspectives, access to health care, and insurance coverage.

• Medication doses need to be changed when complementary therapies significantly and consistently alter physiological responses.

• Complementary therapies accessible to nursing include relaxation, meditation and mindfulness techniques, and imagery. Evidence supports their use to decrease the effects of stress and improve overall patient well-being.

• Many complementary therapies require additional education and certification, including biofeedback, touch therapies (TT, Reiki, and HT), and acupuncture.

• Although increasing evidence supports the use of complementary therapies, many complementary and alternative therapies still lack a scientific basis but are effective based on observed positive outcomes in a number of patients.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

1. Margaret Thompson is a 76-year-old Catholic woman who has been diagnosed with a slow-growing renal tumor. She is scheduled for surgery. You are responsible for the admission assessment and initial care for this patient. What assessment questions about complementary and alternative therapies are important to include during this preoperative period?

2. During the initial assessment Ms. Thompson asks many questions. “Is it cancer? Will the surgery result in a disability? What can I expect? Will I have to be in intensive care unit (ICU)?” You conclude that she is afraid of both the surgical procedure and the outcome. What types of specific nursing-accessible complementary therapies will you offer her during the preoperative period to reduce her anxiety and help her prepare for surgery?

3. In the days following surgery you are assigned to care for Ms. Thompson. Although physically she is recovering quite well from the procedure, you note that she is becoming more despondent and depressed. Preparing for discharge, what complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies do you recommend to help her deal with her depression and cancer diagnosis?

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. When planning patient education, it is important to remember that patients with which of the following often find relief in complementary therapies?

2. Which complementary therapies are most easily learned and applied by the nurse? (Select all that apply.)

3. Which statement best describes the evidence associated with complementary therapies as a whole?

1. Many clinical trials in complementary therapies support their effectiveness in a wide range of clinical problems.

2. It is difficult to find funding for studies about complementary therapies. Therefore we should not expect to find evidence supporting its use.

3. The science supporting the effectiveness of complementary therapies is early in its development. Systematic reviews of the evidence often indicate beginning support for therapies, but there is a lack of strong evidence supporting their widespread use.

4. Most of the research examining complementary and alternative therapies has found little evidence, suggesting that although people like them, they are not effective.

4. The nurse understands that providing holistic care includes treating which of the following?

1. Disease, spirit, and family interactions

2. Desires and emotions of the patient

5. In addition to an adequate patient assessment, when the nurse uses one of the nursing-accessible complementary therapies, he or she must ensure that which of the following has occurred?

1. The family has provided permission.

2. The patient has provided permission and consent.

3. The health care provider has given approval or provided orders for the therapy.

4. He or she has documented that the patient has a complete understanding of complementary and alternative medicine.

6. Which role do patients have in complementary and alternative medicine therapy?

1. Submissive to the practitioner

2. Actively involved in the treatment

7. The nurse is caring for a patient experiencing a stress response. The nurse plans care with the knowledge that systems respond to stress in what manner?

1. Always fail and cause illness and disease

2. Cause structural damage to the body

3. React the same way for all individuals

4. Protect an individual from harm in the short term but cause negative responses over time

8. When meditation therapy is used, nurses need to monitor patients’ medications carefully because meditation may augment the effects of certain drugs such as:

9. A patient who has been using relaxation wants a better response. The nurse recommends the addition of biofeedback. What is the expected outcome related to using this additional modality?

3. To live longer with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

4. To learn how to control some autonomic nervous system responses

10. A patient asks a nurse about therapeutic touch (TT). Which of the following does the nurse include when providing patient education about TT? Therapeutic touch:

1. Intentionally mobilizes energy to balance, harmonize, and repattern the recipient’s biofield

2. Intentionally heals specific diseases or corrects certain symptoms

3. Is overwhelmingly effective in many conditions

4. Is completely safe and does not warrant any special precautions

11. A nurse provides care for a diverse group of patients, including many immigrants. To better understand various types of health care, the nurse learns the traditional Chinese medicine system:

1. Uses acupuncture as its primary intervention modality

2. Uses many modalities that are based on the individual and include herbal therapies, moxibustion, and acupuncture

3. Uses primarily herbal remedies (that are known to have high levels of lead products) and exercise

12. The nurse is planning care for a group of patients who have requested the use of complementary health modalities. Which patient is not a good candidate for imagery?

13. Several nurses on a busy unit are using relaxation strategies while at work. What is the desired workplace outcome from this intervention? (Select all that apply.)

14. The nurse is caring for a patient who uses several herbal preparations in addition to prescribed medications. What does the nurse need to understand about herbal preparations?

1. They are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA); therefore patients and providers should feel confident that they are completely safe.

2. They are natural products and therefore are safe as long as you use them cautiously and prudently for the conditions that are indicated.

3. They are covered by insurance, including Medicare, Medicaid, and private payers.

4. They should be treated as though they were “drugs” of sorts because many have active ingredients that can interact with other medications and change physiological responses.

15. The nurse manager of a community clinic arranges for staff in-services about various complementary therapies available in the community. What is the purpose of this training? (Select all that apply.)

1. Nurses have a long history of providing some of these therapies and need to be knowledgeable about their positive outcomes.

2. Nurses are often asked for recommendations and strategies that promote well-being and quality of life.

3. Nurses play an essential role in patient education to provide information about the safe use of these healing strategies.

4. Nurses appreciate the cultural aspects of care and recognize that many of these complementary strategies are part of a patient’s life.

5. Nurses play an essential role in the safe use of complementary therapies.

6. Nurses learn how to provide all of the complementary modalities during their basic education.

Answers: 1. 4; 2. 3, 4; 3. 3; 4. 3; 5. 2; 6. 2; 7. 4; 8. 4; 9. 4; 10. 1; 11. 2; 12. 3; 13. 3, 4; 14. 4; 15. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

References

American Holistic Nursing Association/American Nurses Association (AHNA/ANA). Holistic nursing: scope and standards of practice. Silver Spring, Md: American Nurses Publishing; 2007.

Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback Association, Biofeedback position statement 2008. http://www.aapb.org/ [accessed September 2, 2010.].

Benson, H. The relaxation response. New York: Avon; 1975.

Dossey, B, Keegan, L. Holistic nursing: a handbook for practice, ed 5. Boston, Mass: Jones & Bartlett; 2009.

Fontaine, K. Healing practices: alternative therapies for nursing, ed 2. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2005.

Gawain, S. Creative visualization: use the power of your imagination to create what you want in your life. Novato, Calif: New World Library; 2008.

Kabat-Zinn, J. Coming to our senses: healing ourselves and the world through mindfulness. New York: Hyperion; 2005.

Koithan, M. Let’s talk about complementary and alternative therapies. J Nurse Pract. 2009;5(3):214.

Kreiger, D. Therapeutic touch: the imprimatur of nursing. Am J Nurs. 1975;25:784.

Kreiger, D. Searching for evidence of physiological change. Am J Nurs. 1979;79:660.

Kreitzer, MJ, et al. Health professions education and integrative healthcare. Explore J Sci Healing. 2009;5(4):2127.

Maciocia, G. The foundations of Chinese medicine: a comprehensive text for acupuncturists and herbalists. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 1989.

National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NIH/NCCAM), Acupuncture and pain: applying modern science to an ancient practice. Complementary and alternative medicine: focus on research and care. online newsletter. February 2010. from http://nccam.nih.gov/news/newsletter/2010_february/2010february.pdf [accessed September 14, 2010.].

National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NIH/NCCAM), What is CAM and CAM basics, 2010. accessed September 1, 2010, from http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/

Pincus, D, Sheikh, AA. Imagery for pain relief: A scientifically grounded guidebook for clinicians. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2009.

Rakel, DP, Faass, N. Complementary medicine in clinical practice. Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett; 2006.

Snyder, M, Lindquist, R. Complementary and alternative therapies in nursing. New York: Springer; 2010.

Research References

Amsterdam, JD, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral Matricaria recutita (chamomile) extract therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(4):378.

Arns, M, et al. Efficacy of neurofeedback treatment in ADHD: the effects on inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity: a meta-analysis. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2009;40(3):180.

Barnes, PM, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. National Health Statistics Rep. 2008;12:1.

Bloch, B, et al. The effects of music relaxation on sleep quality and emotional measures in people living with schizophrenia. J Music Ther. 2010;47(1):27.

Blumenthal, M, et al. Total sales of herbal supplements in US. Herbalgram: Am Botanical Council. 2006;71:64.

Borrelli, F, Ernst, E. Alternative and complementary therapies for the menopause. Maturitas. 2010;66(4):3333.

Cao, H, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine for treatment of fibromyalgia: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(4):397.

Chambers, CT, et al. Psychological interventions for reducing pain and distress during routine childhood immunizations: a systematic review. Clin Ther. 2009;31(suppl 2):S77.

Chiesa, A, Serretti, A. A systematic review of neurobiological and clinical features of mindfulness meditations. Psychol Med. 2010;40(8):1239.

Clarke, PN, et al. From theory to practice: caring science according to Watson and Brewer. Nurs Sci Q. 2009;22(4):339.

Cook, JM, et al. Imagery rehearsal for posttraumatic nightmares: a randomized controlled trial. Trauma stress. September 2010. [[Epub ahead of print]].

Dickinson, HO, et al. Relaxation therapies for the management of primary hypertension in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1(2), 2008. [CD004935, DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004935.pub2].

Ernst, E. Adverse effects of spinal manipulation: a systematic review. J Royal Soc Med. 2007;100(7):330.

Foley, E, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for individuals whose lives have been affected by cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(1):72.

Garland, EL, et al. Mindfulness training modifies cognitive, affective, and physiological mechanisms implicated in alcohol dependence: results of a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42(2):177.

Hawk, C, et al. Best practices recommendations for chiropractic care for older adults: results of a consensus process. J Manipulative Physiological Ther. 2010;33(6):464.

Hollands, GJ, et al. Visual feedback of individuals’ medical imaging results for changing health behavior. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;20:1.

Innes, KE, et al. Mind-body therapies for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2010;66(2):135.

Jain, S, Mills, PJ. Biofield therapies: helpful or full of hype? A best evidence synthesis. Int J Behav Med. 2010;17(1):1.

Jorm, AF, et al. Relaxation for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4(2), 2008. [CD007142, DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD007142.pub2].

Kaminskyj, A, et al. Chiropractic care for patients with asthma: a systematic review of the literature. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2010;54(1):24.

Kimbrough, E, et al. Mindfulness intervention for child abuse survivors. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66(1):17.

Kwekkeboom, K, et al. Patients’ perceptions of the effectiveness of guided imagery and progressive muscle relaxation interventions used in chronic cancer pain. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008;14:185.

Lasseter, JH. The effectiveness of complementary therapies on the pain experience of hospitalized children. J Holistic Nurs. 2006;24:196.

Lee, JH, et al. Acupuncture for chronic low back pain: protocol for a multicenter, randomized, sham-controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;14(11):118.

Molsberger, AF, et al. German Randomized Acupuncture Trial for chronic shoulder pain (GRASP)—a pragmatic, controlled, patient-blinded, multi-centre trial in an outpatient care environment. Pain. 2010;151(1):146.

Nidich, SI, et al. A randomized controlled trial on effects of the transcendental meditation program on blood pressure, psychological distress, and coping in young adults. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22(12):1326.

Reed, T. Imagery in the clinical setting: a tool for healing. Nurs Clin North Am. 2007;42(2):261.

Rheingans, JI. A systematic review of nonpharmacologic adjunctive therapies for symptom management in children with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2007;24(2):81.

Roffe, L, Schmidt, K, Ernst, E. A systematic review of guided imagery as an adjuvant cancer therapy. Psycho-Oncol. 2005;14(8):607.

Rossi, R, et al. Overview on cranberry and urinary tract infections in females. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44(suppl 1):S61.

Scheid, V, et al. The treatment of menopausal symptoms by traditional East Asian medicines: review and perspectives. Maturitas. 2010;66(2):111.

Schmidt, J, et al. Psychological and physiological correlates of a brief intervention to enhance self-regulation in chronic pain. J Pain. 2008;9(4):55.

Trigkilidas, D. Acupuncture therapy for chronic lower back pain: a systematic review. Ann Royal Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92(7):595.

Walker, BF, et al. Combined chiropractic interventions for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:4.

Weeks, BP, Nilsson, U. Music interventions in patients during coronary angiographic procedures: a randomized controlled study of the effect on patients’ anxiety and well-being. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. August 2010. [[Epub ahead of print]].

Wheat, AL, Larkin, KT. Biofeedback of heart rate variability and related physiology: a critical review. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2010;35(3):229.

Zborowsky, T, Kreitzer, MJ. People, place, and process: the role of place in creating optimal healing environments. Creative Nurs. 2009;15(4):1860.

Zhang, Y, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine for treatment of cerebral palsy in children: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(4):375.