Theoretical Foundations of Nursing Practice

• Explain the influence of nursing theory on a nurse’s approach to practice.

• Describe types of nursing theories.

• Describe the relationship between nursing theory, the nursing process, and patient needs.

• Discuss selected theories from other disciplines.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Providing patient-centered nursing care is an expectation for all nurses. As you progress through your curriculum, you will learn to apply knowledge from nursing science, social sciences, physical sciences, biobehavioral sciences, ethics, and health policy. To address individual and family responses to health problems, theory-based nursing practice is important for designing and implementing nursing interventions. Initially you might find nursing theory difficult to understand or appreciate. However, as you increase your knowledge about theories, you will find that they help to describe, explain, predict, and/or prescribe nursing care measures. For example, a theory about caring gives you a way to communicate with your patients and their families and individualize care to meet their needs (Watson, 2010; Sumner, 2010). The scientific work used in developing theories expands the scientific knowledge of the profession. Theories offer well-grounded rationales for how and why nurses perform specific interventions and for predicting patient behaviors and outcomes.

Expertise in nursing is a result of knowledge and clinical experience. The expertise required to interpret clinical situations and make clinical judgments is the essence of nursing care and the basis for advancing nursing practice and nursing science (Benner et al., 2010). As you progress through your courses, reflect and learn from your experiences to grow professionally and use well-developed theories as a basis for your approach to patient care.

The Domain of Nursing

The domain is the perspective of a profession. It provides the subject, central concepts, values and beliefs, phenomena of interest, and central problems of a discipline. The domain of nursing provides both a practical and theoretical aspect of the discipline. It is the knowledge of nursing practice as well as the knowledge of nursing history, nursing theory, education, and research. The domain of nursing gives nurses a comprehensive perspective that allows you to identify and treat patients’ health care needs at all levels and in all health care settings.

A paradigm is a pattern of thought that is useful in describing the domain of a discipline. A paradigm links the knowledge of science, philosophy, and theories accepted and applied by the discipline. The paradigm of nursing includes four links: the person, health, environment/situation, and nursing. The elements of the nursing paradigm direct the activity of the nursing profession, including knowledge development, philosophy, theory, educational experience, research, and practice (Alligood and Tomey, 2010).

Person is the recipient of nursing care, including individual patients, groups, families, and communities. The person is central to the nursing care you provide. Because each person’s needs are often complex, it is important to provide individualized patient-centered care.

Health has different meanings for each patient, the clinical setting, and the health care profession (see Chapter 6). It is dynamic and continuously changing. Your challenge as a nurse is to provide the best possible care based on the patient’s level of health and health care needs at the time of care delivery.

Environment/situation includes all possible conditions affecting patients and the settings in which their health care needs occur. There is a continuous interaction between a patient and the environment. This interaction has positive and negative effects on the person’s level of health and health care needs. Factors in the home, school, workplace, or community all influence a patient’s level of health and health care needs. For example, an adolescent girl with type 1 diabetes needs to adapt her treatment plan to adjust for physical activities of school, the demands of a part-time job, and the timing of social events such as her prom.

Nursing is the “… diagnosis and treatment of human responses to actual or potential health problems …” (American Nurses Association, 2010). The scope of nursing is broad. For example, a nurse does not medically diagnose a patient’s health condition as heart failure. However, a nurse will assess a patient’s response to the decrease in activity tolerance as a result of the disease and develop nursing diagnoses of fatigue, activity intolerance, and ineffective coping. From these nursing diagnoses the nurse creates a patient-centered plan of care for each of the patient’s health problems (see Unit 3). Use critical thinking skills to integrate knowledge, experience, attitudes, and standards into the individualized plan of care for each of your patients (see Chapter 15).

Theory

Theories are designed to explain a phenomenon such as self-care or caring. For example, the nurse using Orem’s self-care deficit theory helps to explain how patients meet their own therapeutic self-care demands. In this theory, nurses assist patients by acting for them or guiding necessary physical and/or psychological support (Alligood, 2010). Orem’s theory contains a detailed framework of self-care concepts that are linked in such a way as to explain, describe, or predict the type of nursing care that helps patients achieve a better level of health (McEwen and Willis, 2011). A theory is a way of seeing through a “set of relatively concrete and specific concepts and the propositions that describe or link the concepts” (Fawcett, 2005).

A nursing theory is a conceptualization of some aspect of nursing that describes, explains, predicts, or prescribes nursing care (Meleis, 2011). For example, Orem’s self-care deficit theory (2001) explains the factors within a patient’s living situation that support or interfere with his or her self-care ability. As a result, a nurse who practices using this theory can anticipate such factors when designing an education plan for the patient. This theory has value in helping nursing design interventions to promote the patient’s self-care in managing an illness such as asthma, heart failure, diabetes, or arthritis.

Theories constitute much of the knowledge of a discipline. Theory and scientific inquiry are vital links to one another, providing guidelines for decision making, problem solving, and nursing interventions (Selanders, 2010). Theories give us a perspective for assessing our patients’ situations and organizing data and methods for analyzing and interpreting information. For example, if you use Orem’s theory in practice, you assess and interpret data to determine patients’ self-care needs, self-care deficits, and self-care abilities in the management of their disease. The theory then guides the design of patient-centered nursing interventions. Application of nursing theory in practice depends on the knowledge of nursing and other theoretical models, how they relate to one another, and their use in designing nursing interventions.

Nursing is a science and an art. Nurses need a theoretical base to demonstrate knowledge about the science and art of the profession when they promote health and wellness for their patients, whether the patient is an individual, a family, or a community (Porter, 2010). A nursing theory helps to identify the focus, means, and goals of practice. Common theories enhance communication and increase autonomy and accountability for care to our patients (Meleis, 2011).

Components of a Theory

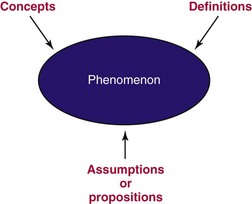

A theory contains a set of concepts, definitions, and assumptions or propositions that explain a phenomenon. The theory explains how these elements are uniquely related in the phenomenon (Fig. 4-1). For example, Kristin Swanson developed her theory about the phenomenon of caring by conducting extensive interviews with patients and their professional caregivers (Swanson, 1991). Swanson’s theory of caring defines five components of caring: knowing, being with, doing for, enabling, and maintaining belief (see Chapter 7). These components provide a foundation of knowledge for nurses to direct and deliver caring nursing practices. Researchers test theories, and as a result they get a clearer perspective of all parts of a phenomenon. Swanson’s theory of caring is one that provides a basis for identifying and testing nurse caring behaviors to determine if caring improves patient health outcomes (Watson, 2010).

Phenomenon

Nursing theories focus on the phenomena of nursing and nursing care. A phenomenon is the term, description, or label given to describe an idea or responses about an event, a situation, a process, a group of events, or a group of situations (Meleis, 2011). This phenomenon may be temporary or permanent. Examples of phenomena of nursing include caring, self-care, and patient responses to stress. For example, in Neuman’s systems model (2011), phenomena focus on stressors perceived by the patient or caregiver. The theoretical model is an open systems model that views nursing as being primarily concerned with nursing actions in stress-related situations. These stressors may include, but are not limited to, patient responses, internal and external environmental factors, and nursing actions.

Concepts

A theory also consists of interrelated concepts. These concepts can be simple or complex and relate to an object or event that comes from individual perceptual experiences (Alligood and Tomey, 2010). Think of concepts as ideas and mental images. They help describe or label phenomena. Again, using Neuman’s systems model (2011) as an example, there are concepts that affect the patient system. The patient system can be an individual, a group, a family, or a community. This system is an open structure that includes internal and external environmental factors. These concepts are physiological, psychological, sociocultural, developmental, and spiritual and may relate to health and wellness, illness prevention, stressors, and defense mechanisms (Meleis, 2011).

Definitions

The definitions within a theory communicate the general meaning of the concepts. These definitions describe the activity necessary to measure the concepts within a theory (Alligood and Tomey, 2010). For example, Neuman’s model uses an open systems approach to describe how patient systems deal with stressors in their environments. A stressor is any stimuli that can produce tension and cause instability within the system. The environment includes internal and external factors that have the potential to affect the patient system. Internal factors exist within the patient system (e.g., the physiological and behavioral responses to illnesses). External factors are outside the patient system (e.g., changes in health care policy or an increase in the crime rate). It is important that nurses using Neuman’s theory in practice focus their care on the system’s responses to the stressors (Meleis, 2011). For example, when patients receive a new diagnosis and perceive the diagnosis to be stressful, they may react by withdrawing or eating an improper diet. In this situation the nurse focuses on both the illness process and the patient’s response to the stressors and designs appropriate interventions.

Assumptions

Assumptions are the “taken-for-granted” statements that explain the nature of the concepts, definitions, purpose, relationships, and structure of a theory (Meleis, 2011). For example, in Neuman’s systems model the assumptions include the following: patients are dynamic; the relationships between the concepts of a theory influence a patient’s protective mechanisms and determine a patient’s response; patients have a normal range of responses; stressors attack flexible lines of defense followed by the normal lines of defense; and the nurse’s actions focus on primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention (Neuman, 2011).

Types of Theory

The general purpose of a theory is important because it specifies the context and situation in which the theory applies (Chinn and Kramer, 2011). For example, theories about pain focus on pain: its cause, effects, and alleviation measures. Theories have different purposes and are sometimes classified by levels of abstraction (grand theories versus middle-range theories) or the goals of the theory (descriptive or prescriptive). For example, a descriptive theory describes a phenomenon such as grief or caring. A predictive theory identifies conditions or factors that predict a phenomenon. A prescriptive theory details nursing interventions for a specific phenomenon and the expected outcome of the care. Box 4-1 summarizes goals of theoretical nursing models.

Grand theories are systematic and broad in scope, complex, and therefore require further specification through research. A grand theory does not provide guidance for specific nursing interventions; but it provides the structural framework for broad, abstract ideas about nursing. For example, Neuman’s systems model is a grand theory that provides a comprehensive foundation for scientific nursing practice, education, and research (Walker and Avant, 2009).

Middle-range theories are more limited in scope and less abstract. They address a specific phenomenon and reflect practice (administration, clinical, or teaching). A middle-range theory tends to focus on a specific field of nursing, such as uncertainty, incontinence, social support, quality of life, and caring, rather than reflect on a wide variety of nursing care situations (Meleis, 2011). For example, Mishel’s theory of uncertainty in illness (1990; 1997) focuses on patients’ experiences with cancer while living with continual uncertainty. The theory provides a basis to help nurses understand how patients cope with uncertainty and the illness response.

Descriptive theories are the first level of theory development. They describe phenomena, speculate on why they occur, and describe their consequences. These theories explain, relate, and in some situations predict nursing phenomena (Meleis, 2011). For example, theories of growth and development describe the maturation processes of an individual at various ages (see Chapter 11). Descriptive theories do not direct specific nursing activities but help to explain patient assessments.

Prescriptive theories address nursing interventions for a phenomenon, describe the conditions under which the prescription (i.e., nursing interventions) occurs, and predict the consequences (Meleis, 2011). Prescriptive theories are action oriented and test the validity and predictability of a nursing intervention. These theories guide nursing research to develop and test specific nursing interventions (George, 2011). For example, Mishel’s theory of uncertainty predicts that increasing the coping skills of patients with gynecological cancer assists their ability to deal with the uncertainty of the cancer diagnosis and treatment (Mishel, 1997). Thus the theory provides a framework to design interventions that support and strengthen patients’ coping resources.

Theory-Based Nursing Practice

Nursing is a practice-oriented discipline. Nursing knowledge is derived from basic and nursing sciences, experience, aesthetics, nurses’ attitudes, and standards of practice. As nursing continues to grow as a profession, knowledge is needed to prescribe specific interventions to improve patient outcomes. Nursing theories and related concepts continue to evolve. Florence Nightingale spoke with firm conviction about the “nature of nursing as a profession that requires knowledge distinct from medical knowledge” (Nightingale, 1860; Selanders, 2010). The overall goal of nursing knowledge is to explain the practice of nursing as different and distinct from the practice of medicine, psychology, and other health care disciplines. Theory generates nursing knowledge for use in practice, thus supporting evidence-based practice. The integration of theory into practice is the basis for professional nursing (McEwen and Wills, 2011).

The nursing process is used in clinical settings to determine individual patient needs (see Unit 3). Although the nursing process is central to nursing, it is not a theory. It provides a systematic process for the delivery of nursing care, not the knowledge component of the discipline. However, a theory can direct how a nurse uses the nursing process. For example, the theory of caring influences what to assess, how to determine patient needs, how to plan care, how to select individualized nursing interventions, and how to evaluate patient outcomes.

Interdisciplinary Theories

To practice in today’s health care systems, nurses need a strong scientific knowledge base from nursing and other disciplines such as the physical, social, and behavioral sciences. Knowledge from these other disciplines includes relevant theories that explain phenomena. An interdisciplinary theory explains a systematic view of a phenomenon specific to the discipline of inquiry. For example, Piaget’s theory of cognitive development helps to explain how children think, reason, and perceive the world (see Chapter 11). Knowledge and use of this theory helps pediatric nurses design appropriate therapeutic play interventions for ill toddlers or school-age children.

Systems Theory

A system is composed of separate components. The components are interrelated and share a common purpose to form a whole. There are two types of systems, open and closed. An open system such as a human organism or a process such as the nursing process interacts with the environment, exchanging information between the system and the environment. Factors that change the environment also affect an open system. Neuman’s systems theory (2011) defines a total-person model of wholism and an open-systems approach. A closed system such as a chemical reaction within a test tube does not interact with the environment.

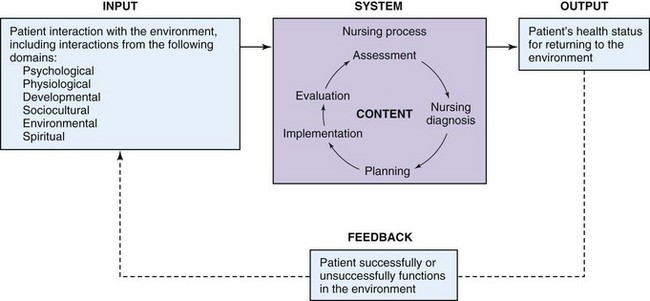

Like all systems, the nursing process has a specific purpose or goal (see Unit 3). The goal of the nursing process is to organize and deliver patient-centered care. As a system the nursing process has the following components: input, output, feedback, and content (Fig. 4-2). Input for the nursing process is the data or information that comes from a patient’s assessment (e.g., how the patient interacts with the environment and the patient’s physiological function). Output is the end product of a system; and in the case of the nursing process it is whether the patient’s health status improves, declines, or remains stable as a result of nursing care.

Feedback serves to inform a system about how it functions. For example, in the nursing process the outcomes reflect the patient’s responses to nursing interventions. The outcomes are part of the feedback system to refine the plan of care. Other forms of feedback in the nursing process include responses from family members and consultation from other health care professionals.

The content is the product and information obtained from the system. Again, using the nursing process as an example, the content is the information about the nursing interventions for patients with specific health care problems. For example, patients with impaired bed mobility have common skin care needs and interventions (e.g., hygiene and scheduled positioning changes) that are very successful in reducing the risk for pressure ulcers.

Basic Human Needs

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is an interdisciplinary theory that is useful for designating priorities of nursing care (see Fig. 6-3, p. 69.) The hierarchy of basic human needs includes five levels of priority. The most basic, or first level, includes physiological needs such as air, water, and food. The second level includes safety and security needs, which involve physical and psychological security. The third level contains love and belonging needs, including friendship, social relationships, and sexual love. The fourth level encompasses esteem and self-esteem needs, which involve self-confidence, usefulness, achievement, and self-worth. The final level is the need for self-actualization, the state of fully achieving potential and having the ability to solve problems and cope realistically with situations of life. When using this hierarchy, basic physiological and safety needs are usually the first priority, especially when a patient is severely dependent physically. However, you will encounter situations in which a patient has no emergent physical or safety needs. Instead, you will give high priority to the psychological, sociocultural, developmental, or spiritual needs of the patient.

Patients entering the health care system generally have unmet needs. For example, a person brought to an emergency department experiencing acute pneumonia has an unmet need for oxygen, the most basic physiological need. An older woman in a high-crime area is concerned about physical safety. A widowed homemaker whose children have moved away feels that she does not belong or is not loved. The hierarchy of needs is a way to plan for individualized patient care.

Developmental Theories

Human growth and development are orderly predictive processes that begin with conception and continue through death. A variety of well-tested theoretical models describe and predict behavior and development at various phases of the life continuum. Chapter 11 details these developmental theories, and Chapters 12 through 14 demonstrate changes in growth and development in various age-groups.

Psychosocial Theories

Nursing is a diverse discipline that strives to meet the physiological, psychological, sociocultural, developmental, and spiritual needs of patients. Theoretical models to explain and/or predict patient responses exist in each of these domains. For example, Chapter 9 discusses models for understanding cultural diversity and implementing care to meet the diverse needs of the patient. Chapter 10 describes family theory and how to meet the needs of the family when the family is the patient or when the family is the caregiver. Chapter 36 discusses several models of grieving and demonstrates how to assist patients through loss, death, and grief.

Selected Nursing Theories

Definitions and theories of nursing can help you understand the practice of nursing. The following sections describe, in chronological order of theory development, selected theories and their concepts (Table 4-1).

TABLE 4-1

| THEORIST | GOAL OF NURSING | FRAMEWORK FOR PRACTICE |

| Nightingale—1860 | Facilitate the reparative processes of the body by manipulating patient’s environment | Nurse manipulates patient’s environment to include appropriate noise, nutrition, hygiene, light, comfort, socialization, and hope. |

| Peplau—1952 | Develop interaction between nurse and patient | Nursing is a significant, therapeutic, interpersonal process. Nurses participate in structuring health care systems to facilitate interpersonal relationships. |

| Henderson—1955 | Work interdependently with other health care workers, assisting patient in gaining independence as quickly as possible; help patient gain lacking strength | Nurses help patient perform Henderson’s 14 basic needs. |

| Orem—1971 | Care for and help patient attain total self-care | Nursing care is necessary when the patient is unable to fulfill biological, psychological, developmental, or social needs. |

| King—1971 | Use communication to help patient reestablish positive adaptation to environment | Nursing is a dynamic interpersonal process among nurse, patient, and health care system. |

| Neuman—1974 | Help individuals, families, and groups attain and maintain maximal level of total wellness by purposeful interventions | Stress reduction is goal of systems model of nursing practice. Nursing actions are in primary, secondary, or tertiary level of prevention. |

| Leininger—1978 | Provide care consistent with nursing’s emerging science and knowledge with caring as central focus | With this transcultural care theory, caring is the central and unifying domain for nursing knowledge and practice. |

| Roy—1970 | Identify types of demands placed on patient, assess adaptation to demands, and help patient adapt | This adaptation model is based on the physiological, psychological, sociological, and dependence-independence adaptive modes. |

| Watson—1979 | Promote health, restore patient to health, and prevent illness | Involves the philosophy and science of caring. Caring is an interpersonal process comprising interventions to meet human needs. |

| Benner and Wrubel—1989 | Focus on patient’s need for caring as a means of coping with stressors of illness | Caring is central to the essence of nursing. It creates the possibilities for coping and enables possibilities for connecting with and concern for others. |

Modified from Chinn PL, Kramer ML: Integrated knowledge development in nursing, ed 8, St. Louis, 2011, Mosby.

Nightingale’s Theory

Florence Nightingale’s work was an initial model for nursing. Meleis (2011) notes that Nightingale’s concept of the environment was the focus of nursing care and her suggestion that nurses need not know all about the disease process differentiated nursing from medicine. The focus of nursing is caring through the environment and helping the patient deal with the symptoms and changes in function related to an illness (Selanders, 2010).

Nightingale did not view nursing as limited to the administration of medications and treatments but oriented toward providing fresh air, light, warmth, cleanliness, quiet, and adequate nutrition (Nightingale, 1860). Through observation and data collection, she linked the patient’s health status with environmental factors and initiated improved hygiene and sanitary conditions during the Crimean War.

Nightingale’s “descriptive theory” provides nurses with a way to think about patients and their environment. Her letters and writings direct the nurse to act on behalf of the patient. Her visionary principles included the areas of practice, research, and education. Most important, her concepts and principles shaped and defined nursing practice (Alligood and Tomey, 2010). Nightingale taught and used the nursing process, noting that “vital observation [assessment] … is not for the sake of piling up miscellaneous information or curious facts, but for the sake of saving life and increasing health and comfort (Nightingale, 1860).”

Peplau’s Theory

Hildegard Peplau’s theory (1952) focuses on interpersonal relations between the nurse, the patient, and the patient’s family and developing the nurse-patient relationship. The patient is an individual with a need, and nursing is an interpersonal and therapeutic process. This nurse-patient relationship is influenced by both the nurse’s and the patient’s perceptions and preconceived ideas (George, 2011).

In developing a nurse-patient relationship, the nurse can serve as a resource person, counselor, and surrogate. For example, when the patient seeks help, the nurse and patient first discuss the nature of any problems, and the nurse explains the services available. As the nurse-patient relationship develops, the nurse and patient mutually define the problems and potential solutions. The patient gains from this relationship by using available services to meet needs, and the nurse helps the patient reduce anxiety related to the health care problems.

Peplau’s theory is unique: the collaborative nurse-patient relationship creates a “maturing force” through which interpersonal effectiveness meets the patient’s needs. This theory is useful in establishing effective nurse-patient communication when obtaining a nursing history, providing patient education, or counseling patients and their families (see Chapter 24). When the patient’s original needs are resolved, new needs sometimes emerge. According to Peplau, the following phases characterize the nurse-patient interpersonal relationship: orientation, working phase, and termination (George, 2011).

Henderson’s Theory

Virginia Henderson defines nursing as “assisting the individual, sick or well, in the performance of those activities that will contribute to health, recovery, or a peaceful death and that the individual would perform unaided if he or she had the necessary strength, will, or knowledge” (Harmer and Henderson, 1955; Henderson, 1966). Henderson organized the theory into 14 basic needs of the whole person and includes phenomena from the following domains of the patient: physiological, psychological, sociocultural, spiritual, and developmental. The interpersonal relationship between the nurse and the patient creates a caring environment to identify the patient’s needs, plan the goals of care, and provide patient-centered nursing care (George, 2011). Framing nursing care around the needs of the individual allows you to use Henderson’s theory for a variety of patients across the life span and in multiple settings along the health care continuum.

Orem’s Theory

Dorothea Orem’s self-care deficit theory (2001) focuses on the patient’s self-care needs. Orem defines self-care as a learned, goal-oriented activity directed toward the self in the interest of maintaining life, health, development, and well-being. The goal of Orem’s theory is to help the patient perform self-care and manage his or her health problems. Nursing care is necessary when the patient is unable to fulfill biological, psychological, developmental, or social needs. This theory works well in all steps of the nursing process (George, 2011). The nurse assesses and determines why a patient is unable to meet these needs, identifies goals to assist the patient, intervenes to help the patient perform self-care, and evaluates how much self-care the patient is able to perform. According to Orem’s theory, the goal of nursing is to increase the patient’s ability to independently meet these needs (George, 2011; Orem, 2001).

Leininger’s Theory

Leininger used her background in anthropology to form her theory of cultural care diversity and universality (Alligood, 2010). Human caring varies among cultures in its expressions, processes, and patterns. Social structure factors such as the patient’s religion, politics, culture, and traditions are significant forces affecting care and influencing the patient’s health and illness patterns. While reading the chapter on culture, think about the diversity of the patients and their nursing care needs (see Chapter 9). The major concept of Leininger’s theory is cultural diversity, and the goal of nursing care is to provide the patient with culturally specific nursing care (Alligood, 2010; Leininger, 1991). To provide care to patients of unique cultures, the nurse safely integrates the patient’s cultural traditions, values, and beliefs into the plan of care. Leininger’s theory recognizes the importance of culture and its influence on everything that involves the patient and the providers of nursing care (George, 2011). For example, some cultures believe that the leader in the community needs to be present during health care decisions. As a result, the health care team may need to reschedule when rounds occur to include the community leader. In addition, symptom expression also differs among cultures. A person with an Irish background might be stoic and not complain about pain, whereas a person from a Middle Eastern culture might be very vocal about pain. In both cases the nurse needs to skillfully incorporate the patient’s cultural practices in assessing the patient’s level of pain (e.g., is the pain getting worse or remaining the same?).

Betty Neuman’s Theory

The Neuman systems model is based on stress and the client’s reaction to the stressor (George, 2011). In this model the client is the individual, group, family, or community. The system is composed of five concepts that interact with one another: physiological, psychological, sociocultural, developmental, and spiritual (Neuman, 2011). These concepts interact with both internal and external environmental factors and all levels of prevention (primary, secondary, and tertiary) to achieve optimal wellness (Neuman and Reed, 2007). Neuman considers any internal and external factors as stressors (Alligood, 2010) that affect the patient’s stability and any or all of the five system concepts. The role of nursing is to stabilize the patient or situation. When you apply the Neuman systems model, you assess the stressor and the patient’s response to the stressor, identify nursing diagnoses, plan patient-centered care, implement interventions, evaluate the patient’s response, and determine if the stressor is resolved.

Roy’s Theory

The Roy adaptation model (Roy, 1989; Roy et al., 2009) views the patient as an adaptive system. According to Roy’s model, the goal of nursing is to help the person adapt to changes in physiological needs, self-concept, role function, and interdependent relations during health and illness (Alligood and Tomey, 2010). The need for nursing care occurs when the patient cannot adapt to internal and external environmental demands. All individuals must adapt to the following demands: meeting basic physiological needs, developing a positive self-concept, performing social roles, and achieving a balance between dependence and independence.

The nurse determines which demands are causing problems for a patient and assesses how well the patient is adapting to them. Nurses direct care at helping the patient adapt to the changes (George, 2011; Alligood, 2010). For example, a patient recovering from a worsening of heart failure needs nursing interventions to assist in adapting to the resultant activity in tolerance (Box 4-2).

Watson’s Theory

Jean Watson’s theory of transpersonal caring (2005, 2008) defines the outcome of nursing activity in regard to the humanistic aspects of life (Alligood and Tomey, 2010). The purpose of nursing action is to understand the interrelationship among health, illness, and human behavior. Thus nursing is concerned with promoting and restoring health and preventing illness.

Watson designed the model around the caring process, assisting patients in attaining or maintaining health or dying peacefully (Watson, 2005). This caring process requires the nurse to be knowledgeable about human behavior and human responses to actual or potential health problems (see Chapter 7). The nurse also needs to know individual patient needs, how to respond to others, and strengths and limitations of the patient and family and those of the nurse. In addition, the nurse comforts and offers compassion and empathy to patients and their families. Caring represents all factors the nurse uses to deliver care to the patient (Watson, 1996).

Benner and Wrubel’s Theory

The primacy of caring is a model proposed by Patricia Benner and Judith Wrubel (1989). Caring is central to nursing and creates possibilities for coping, enables possibilities for connecting with and concern for others, and allows for giving and receiving help (Chinn and Kramer, 2011). Caring means that persons, events, projects, and things matter to people. It presents a connection and represents a wide range of involvement (e.g., caring about one’s family, one’s friendships, and one’s patients). Benner and Wrubel see the personal concern as an inherent feature of nursing practice. In caring for one’s patients, nurses help patients recover by noticing interventions that are successful and that guide future caregiving.

Application of nursing theory in practice depends on nurses having knowledge of the theories and an understanding of how they relate to one another. Theories are the organizing frameworks for the science of nursing and the substantive approaches for nursing care. They provide critical thinking structures to guide clinical reasoning and problem solving.

Link between Theory and Knowledge Development in Nursing

Nursing has its own body of knowledge that is both theoretical and experiential. Theoretical knowledge includes and “reflects on the basic values, guiding principles, elements, and phases of a conception of nursing” (Meleis, 2011). The goals of theoretical knowledge stimulate thinking and create a broad understanding of the “science” and practices of the nursing discipline.

Experiential knowledge is not organized in the same manner as theoretical knowledge. This type of knowledge or the “art” of nursing is based on nurses’ experience in providing care to patients. You achieve this through personal knowledge gained through reflection on care experiences, synthesis, and integration of the art and science of nursing.

Nursing theories help direct nursing practice. When using theory-based nursing practice, you apply the principles of the theory in delivering nursing interventions in your practice. Theory-based nursing practice improves nurse satisfaction and patient outcomes because the basic values, guiding principles, and elements from the foundation of a particular nursing theory give meaning to the practice and influence how patient care is provided (Veo, 2010).

Relationship Between Nursing Theory and Nursing Research

The relationship between nursing theory and nursing research builds the scientific knowledge base of nursing, which is then applied to practice. As more research is conducted, the discipline learns to what extent a given theory is useful in providing information to improve patient care. The relationships of components in a theory often help drive the research questions. For example, the components within Orem’s self-care deficit theory have led nurse researchers to test interventions for improving self-care. In one study, older hospitalized adults were able to learn their medication schedules and improve their activities of daily living before discharge, were discharged earlier, and had fewer complications (Glasson et al., 2006).

Sometimes research is used to identify new theories. Theory-generating research tries to discover and describe relationships of phenomena without imposing preconceived notions (e.g., hypotheses) of what the phenomena under study mean (George, 2011). In theory-generating research the investigator makes observations to view a phenomenon in a new way. For example, a researcher wants to understand end-of-life decision making. In this example, the researcher interviews surrogate decision makers. From these interviews he or she makes objective observations about the surrogate’s decision-making process, resulting in an initial theory of surrogate decision making (Loomis, 2009).

Theory-testing research determines how accurately a theory describes a nursing phenomenon. Testing helps to develop the evidence for describing or predicting patient outcomes. The researcher has some preconceived idea as to how patients describe or respond to a phenomenon and generates research questions or hypotheses to test the assumptions of the theory. No one study tests all components of a theory; researchers test the theory through a variety of research activities. Referring to the previous example of surrogate decision making, the researcher tests elements of the theory. For example, interviews of decision makers indicated that there was a need for more knowledge about end-of-life care expectations (Loomis, 2009). The researcher then designs and tests an educational program that incorporates end-of-life expectation with one that does not to determine which is most effective for groups of surrogate caregivers. Theory-generating or theory-testing research refines the knowledge base of nursing. As a result, nurses incorporate research-based interventions into theory-based practice. As research activities continue, not only does the knowledge and science of nursing increase, but patients are the recipients of the best evidence-based nursing practice (see Chapter 5).

As an art, nursing relies on knowledge gained from practice and reflection on past experiences. As a science, nursing draws on scientifically tested knowledge applied in the practice setting (Kikuchi, Simmons, and Romyn, 1996). But it is the “expert nurse” who transports the art and science of nursing into the scientific realm of creative caring.

Key Points

• A nursing theory is a conceptualization of some aspect of nursing communicated for the purpose of describing, explaining, predicting, and/or prescribing nursing care.

• Grand theories are the complex structural framework for broad, abstract ideas.

• Middle-range theories are more limited in scope and less abstract. These theories address specific phenomena or concepts and reflect practice.

• The paradigm of nursing identifies four links of interest to the profession: the person, health, environment/situation, and nursing. Nurse theorists agree that these four components are essential to the development of theory.

• Theory is the generation of nursing knowledge used for practice. Nursing process is the method for applying the theory or knowledge. The integration of theory and nursing process is the basis for professional nursing.

• Theories from nursing and other disciplines help explain how the roles and actions of nurses fit together in nursing.

• Theory-generating research tries to discover and describe relationships without imposing preconceived notions (e.g., hypotheses) of what the phenomenon under study means.

• Theory-testing research determines how accurately a theory describes nursing phenomena.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

1. Kathy Jones and Sheri Walker are sophomores in a college program. Next week they will have their first clinical practice. Kathy will be in a community health setting, and Sheri will be in an acute health care agency. They need to prepare general assessment questions applicable to both settings using Orem’s self-care deficit theory. Explain how the theory might apply for patient assessment in different health care settings.

2. In a classroom setting you are given the following examples of questions that lead either to theory-generating or theory-testing research. Identify whether they are theory testing or theory generating and explain.

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. Which of the following are components of the paradigm of nursing?

1. The person, health, environment, and theory

2. Health, theory, concepts, and environment

2. A theory is a set of concepts, definitions, relationships, and assumptions that:

3. A patient with diabetes is controlling the disease with insulin and diet. The nursing health care provider is focusing efforts to teach the patient self-management. Which of the following nursing theories is useful in promoting self management?

4. While working in a community health clinic, it is important to obtain nursing histories and get to know the patients. Part of history taking is to develop the nurse-patient relationship. Which of the following apply to Peplau’s theory when establishing the nurse-patient relationship? (Select all that apply.)

1. An interaction between the nurse and patient must develop.

2. The patient’s needs must be clarified and described.

3. The nurse-patient relationship is influenced by patient and nurse preconceptions.

4. The nurse-patient relationship is influenced only by the nurse’s preconceptions.

5. Theory-based nursing practice uses a theoretical approach for nursing care. This approach moves nursing forward as a science. This suggests that:

1. One theory will guide nursing practice.

2. Scientists will decide nursing decisions.

3. Nursing will only base patient care on the practice of other sciences.

4. Theories will be tested to describe or predict patient outcomes.

6. To practice in today’s health care environment, nurses need a strong scientific knowledge base from nursing and other disciplines such as the physical, social, and behavioral sciences. This statement identifies the need for which of the following?

7. Which of the following theories describe the life processes of an older adult facing chronic illness?

8. Match the following components of systems theory with the definition of that component.

9. A patient is admitted to an acute care area. The patient is an active business man who is worried about getting back to work. He has had severe diarrhea and vomiting for the last week. He is weak, and his breathing is labored. Using Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, identify this patient’s immediate priority.

10. Which of the following is closely aligned with Leininger’s theory?

1. Caring for patients from unique cultures

2. Understanding the humanistic aspects of life

3. Variables affecting a patient’s response to a stressor

4. Caring for patients who cannot adapt to internal and external environmental demands

11. Match the following theories with their definitions.

A Addresses specific phenomena and reflect practice

B First level in theory development and describes a phenomenon

C Provides a structural framework for broad concepts about nursing

D Linked to outcomes (consequences of specific nursing interventions)

12. A nurse is applying Henderson’s theory as a basis for theory based-nursing practice. Which other elements are important for theory-based nursing practice? (Select all that apply.)

1. Knowledge of nursing science

2. Knowledge of related sciences

13. Which of the following statements apply to theory generation? (Select all that apply.)

14. Which of the following statements about theory-based nursing practice is incorrect?

1. Contributes to evidence-based practice

2. Provides a systematic process for designing nursing interventions

15. As an art nursing relies on knowledge gained from practice and reflection on past experiences. As a science nursing relies on (select all that apply):

Answers: 1. 4; 2. 2; 3. 2; 4. 1, 2, 3; 5. 4; 6. 3; 7. 2; 8. 1 C, 2 A, 3 D, 4 B; 9. 2; 10. 1; 11. 1 C, 2 A, 3 B, 4 D; 12. 1, 2, 4; 13. 1, 2, 4; 14. 3; 15. 1, 2, 3.

References

Alligood, MR. Nursing theory utilization & application, ed 4. St Louis: Mosby; 2010.

Alligood, MR, Tomey, AM. Nursing theorists and their work, ed 7. St Louis: Mosby; 2010.

American Nurses Association. Nursing’s social policy statement: the essence of the profession. Silver Spring, Md: American Nurses Publishing; 2010.

Benner, P, Wrubel, J. The primacy of caring: stress and coping in health and illness. Menlo Park, Calif: Addison-Wesley; 1989.

Benner, P, et al. Educating nurses: a call for radical transformation. Stanford, Calif: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 2010.

Chinn, PL, Kramer, MK. Integrated knowledge development in nursing, ed 8. St Louis: Mosby; 2011.

DeSanto-Madeya, S, Fawcett, J. Toward understanding and measuring adaptation level in the context of the Roy adaptation model. Nurs Sci Q. 2009;22(4):355.

Fawcett, J. Contemporary nursing knowledge: analysis and evaluation of conceptual models of nursing, ed 2. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 2005.

George, J. Nursing theories: a base for professional nursing practice, ed 6. Saddle River, NJ: Pearson; 2011.

Harmer, D, Henderson, V. Textbook of the principles and practice of nursing, ed 5. Riverside, NJ: Macmillan; 1955.

Henderson, V. The nature of nursing. New York: Macmillan; 1966.

Kikuchi, JF, Simmons, H, Romyn, D. Truth in nursing inquiry. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1996.

King, IM. Toward a theory for nursing. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1971.

Leininger, M. Transcultural nursing: concepts, theories, and practice. John Wiley & Sons; 1978.

Leininger, MM. Culture care diversity and universality: a theory of nursing, Pub No 15-2402. New York: National League for Nursing Press; 1991.

McEwen, M, Wills, EM. Theoretical basis for nursing, ed 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Meleis, AI. Theoretical nursing: development and progress, ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Neuman, B, The Betty Neuman health-care systems model: A total person aproach to patient problems. (1974). JP Riehl, C Roy, eds. Conceptual models for nursing practice, ed 2, Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1974.

Neuman, BM. The Neuman systems model, ed 5. Norwalk, Conn: Pearson, Prentice Hall.; 2011.

Neuman, BM, Reed, KS. A Neuman systems model perspective on nursing in 2050. Nurs Sci Q. 2007;20:111.

Nightingale, F. Notes on nursing: what it is and what it is not. London: Harrison & Sons; 1860.

Orem, DE. Nursing: concepts of practice. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1971.

Orem, DE. Nursing: concepts of practice, ed 6. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001.

Peplau, HE. Interpersonal relations in nursing. New York: GP Putnam’s Sons; 1952.

Porter, S. Fundamentals patterns of knowing in nursing: the challenge of evidenced-based practice. Adv Nurs Sci. 2010;33(1):3.

Roy, C. Adaptation: A conceptual framework for nursing. Nurs Outlook. 1970;18:42.

Roy, C. Relating nursing theory to nursing education: A new era. Nurse Educator. 1979;4:16.

Roy, C. The Roy adaptation model. In Riehl JP, Roy C, eds.: Conceptual models for nursing practice, ed 3, New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1989.

Roy, R, et al. The Roy adaptation model and research. Nurs Sci Q. 2009;21:209.

Selanders, LC. The power of environmental adaptation: Florence Nightingale’s original theory for nursing practice. J Holistic Nurs. 2010;28(1):81.

Walker, LO, Avant, KC. Strategies for theory construction in nursing, ed 5. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2009.

Watson, J. Nursing: the philosophy and science of caring. Boston: Little, Brown; 1979.

Watson, J. Watson’s theory of transpersonal care, In Walker PH, Neuman B: Blueprint for use of nursing models: education, research, practice, and administration, Pub NO 14-2696. New York: National League of Nursing Press; 1996.

Watson, J. Caring science as sacred science. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 2005.

Watson, J. The philosophy and science of caring. Boulder: University Press of Colorado; 2008.

Watson, J. Caring science and the next decade of holistic healing: transforming self and system from the inside out. Am Holistic Nurses Assoc. 2010;30(2):14.

Research References

Bakan, G, Akyol, AD. Theory-guided interventions for adaptation to heart failure. J Adv Nurs. 2008;61(6):596.

Glasson, J, et al. Evaluation of a model of nursing care for older patients using participatory action research in an acute medical ward. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15(5):588.

Loomis, B. End-of-life issues: difficult decisions and dealing with grief. Nurs Clin North Am. 2009;44:223.

Mishel, MH. Reconceptualization of the uncertainty in illness theory. Image J Nurs Sch. 1990;22(4):256.

Mishel, MH. Uncertainty in acute care. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 1997;15:57.

Sumner, J. A critical lens on the instrumentation of caring in nursing research. Adv Nurs Sci. 2010;33(1):E17.

Swanson, KM. Empirical development of a middle-range theory of caring. Nurs Res. 1991;40(3):161.

Veo, P. Concept mapping for applying theory to nursing practice. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2010;26(1):22.