Chapter 7 Midwifery regulation in the United Kingdom

Regulation of healthcare professionals does not stand still and is constantly evolving, albeit in some instances, slowly. The struggles for legislation to control the practice of midwives in the UK prior to the first Midwives Act and since have been well documented (Cowell & Wainwright (1981), Donnison (1988), Heagerty (1996) and Towler & Bramall (1986)), and can be explored in detail in those texts.

The purpose of midwifery regulation

Statutory regulation provides structure and boundaries that can be understood and interpreted by both professionals and the public, and it is the basis of a contract of trust between the public and the profession. Although the primary purpose of regulation is protection of the public, the same mechanism protects midwives and supports them in their practice. The UK was not the first country to establish legislation governing the practice of midwives as governments in Austria, Norway and Sweden had taken such an approach as early as 1801.

Regulation of midwifery can and should play a key part in helping to improve women’s experiences of the maternity services. Women and their families look to regulation to ensure that they are being cared for by competent and skilled midwives who are properly educated and up to date in their practice. It is important therefore, not to think of regulation in terms of abstract concepts or principles, but what it means in ordinary everyday aspects of healthcare, and how it can support the types of care that women need or we would want for ourselves and our families. Midwifery regulation enables the public to be assured that anyone calling themselves a midwife is competent to practise as a midwife.

In the UK, no-one can call themself a midwife or practise as a midwife unless they are on the Nursing and Midwifery Council’s (NMC) Register. This registration must be active, which means that the midwife has met the continuing professional development and practice requirements to stay on the Register and has paid the fee that enables this to happen.

As Frances Blunden stated in 2007, ‘Much of the current approach to regulation is far too reactive, with a tendency to focus on serious misdemeanours. We wait for someone to get it wrong dramatically and then very slowly take action. Women should not have to die or to be seriously harmed by the actions of midwives or other professionals before the protection that regulation is supposed to afford them swings into action. That’s an approach that lets down women, their babies, and professionals, sometimes very badly.’

There has been a change in the ethos and approach to regulation in the UK during the past 5 years and regulation is moving to a more proactive stance that seeks to prevent harm from happening in the first place. This change will hopefully ensure that midwives, wherever they practise, adopt the values and principles of a woman-centred approach to regulation in all that they do.

Self-regulation

In the UK, midwives are members of a self-regulating profession. Self-regulation is a privilege in many ways, as it means that the standards for education and practice expected of any midwife are set by midwives themselves. Self-regulating professions have regulatory bodies that are funded by the professionals themselves. In the case of midwives and nurses, their initial and subsequent periodic registration payment is the sole funding that pays for all of the functions of their regulatory body, the NMC.

In the UK self-regulation is achieved through a statutory midwifery committee of the NMC, which advises the Nursing and Midwifery Council (The Council) about what is needed to ensure safe and competent midwives. The midwifery committee has powers defined under Section 41 of The Nursing and Midwifery Order (2001). The term ‘statutory’ means that the role and scope of the committee is set in law and cannot be reduced or the committee disbanded unless there is a change in legislation to allow that to happen. Any rules or standards for midwifery education or practice set by the midwifery committee are subsequently approved by the Council before they can come into effect.

While midwives practise in a wide range of settings, as a profession they are unified by underlying values and responsibilities. Being a midwife is not merely a job, it is a professional responsibility. Each midwife has a personal responsibility for their own practice by being aware of their own strengths and weaknesses in practice. Each is expected to take steps to ensure they develop their skills and knowledge to ensure that they maintain their own competence.

There has been and remains rising public concern in the UK about healthcare professionals regulating themselves as a result of some high profile media cases where patient care was severely compromised (Kennedy 2001).

Midwives have a responsibility to be aware when a colleague’s practice is not up to the expected standards and to take appropriate action when this is the case. Self-regulation and professional freedom are based on the assumption that professionals can be trusted to work without supervision and, where necessary, to take action against colleagues (Hogg 2000).

Midwives also share a collective responsibility for how women and their families are treated and cared for. This means that they have a responsibility to highlight both individual instances where practices are compromising safe and appropriate care for women, but also where the systems or processes within organizations providing services for women are compromising safe care.

Although most healthcare professions in the UK set their own standards and codes of conduct, this was not always the case for midwives. When the original Midwives Act came into force in 1902, the body it created, the Central Midwives Board (CMB), had no requirement for even one midwife to be included on its Council. Until 1983, it was the case that the midwifery statutory bodies of the UK were dominated by doctors who also held the chairmanships until the last decade prior to their dissolution.

This powerful body was not, as was the case with other professional statutory bodies, to be largely constituted of members of the occupation to be regulated, but to be in the hands of medical practitioners (RCM 1991).

At the present time, self-regulation of midwifery does not exist in some countries. In some instances, regulations for midwifery education or practice are set by the national Government, or by another professional group who may be perceived as ‘senior’.

The midwifery profession, as are other professions in the UK, is affected to varying extents by national regulations that are set by others who are not part of the profession. Examples of this are legislation to protect vulnerable children or adults (DH 2006, 2007a), medicines legislation (see Ch. 49), employment legislation or health and safety regulations in the workplace. All midwives are bound by these national laws in the same way as others.

Protection of the public cannot be achieved through the Regulatory body alone. It is more likely when the combination of statutory regulation, personal self-regulation, employment practices, professional organizations, education and other means of working with a common purpose achieves a strong framework that enhances protection of the public.

However, as the events at Bristol showed, it can be very difficult for individual professionals to act ethically and raise these issues within their organization for fear of reprisal. It is here that the regulator and regulation can play an active role in supporting the individual midwife by offering guidance to her. The regulator can also work actively with other service regulators such as the local supervising authorities or the Healthcare Commission in England or Quality Improvement Scotland, etc. to ensure early action is taken to prevent unnecessary harm to women or their families.

The NMC code

Midwives and midwifery practice in the UK are bound by a set of rules and standards that set the minimum requirements for anyone wishing to practise midwifery within the four countries. In addition to these requirements, which affect only midwives, there is a further set of ethical and behavioural standards to which all midwives and nurses working in the UK must adhere (NMC 2008a).

This is perhaps the most significant of the standards set by the regulatory body for midwives as it contains the ethical and moral codes that all midwives are expected to comply with. The Code applies to anyone who is on the NMC Register; however the relevance and need for codes of practice and conduct go beyond nurses and midwives and their day-to-day contact with women or patients.

Even when off-duty, midwives must still adhere to the principles and values embodied in The Code, particularly as they directly relate to the women and families that have been in their care. An example of this is respecting women’s confidentiality. How easy would it be to breach this should a midwife discuss a difficult day with a woman or her family, to her partner or friend?

The regulator is clear that midwives working as managers also need to abide by The Code and principles of good practice, and have a duty towards women and their families, as well as the wider community. Although they may have minimal direct contact with women, their conduct, practice and professional decisions can fundamentally affect women’s care. There is a public expectation that their first consideration in all activities must be the interests and safety of women and families.

Increasingly, women come into contact with support workers who are taking on many roles or tasks that in the past have been undertaken by midwives (NHS Employers 2005). There have been concerns expressed about the increasing role maternity support workers are playing in some hospitals and communities in providing care, and that this might be putting women and babies at risk (Sandall et al 2006). This raises another important question for the midwives who are asking support workers to take on roles that are outside their level of competence, and their personal responsibility for this under The Code.

The Code defines what women and their families have the right to expect in any encounter with a midwife. These can be summarized under the following:

Although The Code sets out the principles and values for professional midwifery practice, it cannot guarantee high quality care unless the individual midwife internalizes the values that underpin the Code and takes personal responsibility for complying with its requirements.

Public expectations of professionalism and regulation

Women and their families look to regulation and the regulator for protection from ‘bad’ professionals. They expect effective systems to pick up poor performance and to address the problems effectively, with appropriate sanctions or measures. They also expect effective redress mechanisms if something goes wrong that are timely and easy to access. Unfortunately, many of the public’s assumptions about regulation are misguided as there is no coherent regulatory system that guarantees quality and safety across the whole healthcare system.

Most members of the public do not know how midwives or other healthcare professionals are regulated and may not be concerned to know how this is achieved. This is because they receive good treatment from most professionals when they receive healthcare. The fact that a midwife is a member of a professional Register acts as a symbol of quality and competence that women can have trust in.

The public have high expectations of midwives, that they are compassionate, competent and provide safe care. Women allow midwives and the other healthcare professionals involved in their maternity care to have intimate access to their lives, home and property because they trust them to do what they are supposed to do, and to do it right. Trust is fundamental to the healthcare relationship. It is the responsibility of every midwife to maintain and build that public trust and confidence at all times. To betray that trust may not only cause physical or emotional harm, but also potentially undermines the reputation of the whole profession.

When is a midwife not a midwife?

‘Midwife’ is a title protected in statute in the UK. This means that no-one can call themselves a midwife or indeed imply they are a midwife in a business unless they hold active registration on the midwives part of the NMC register. In practical terms, this means that although a number of individuals may hold a midwifery qualification, they cannot use the title midwife nor provide midwifery care and advice unless they have met all requirements to join and maintain their registration as a midwife.

This has important implications for organizations who may wish to employ someone who holds a midwifery qualification but who does not hold midwifery registration, to offer care or advice to pregnant women. Such an approach increases risk to the public as the person would not be competent to provide midwifery care or advice. It would also mean that the individual concerned would be committing a criminal offence.

This most often applies to those who may have trained as a midwife and as a nurse but who have lapsed or not met requirements to maintain the midwife part of their registration. It would also apply to anyone wishing to work in the UK who may have trained as a midwife outside the UK but who is not registered as such with the NMC.

There are also implications for anyone wishing to set up a business with the term midwife or midwifery in the name of the business. In the UK, most types of businesses have to be registered with Companies House. Permission must be sought from the NMC for the title to be used in this context otherwise Companies House will refuse to register the name of the business. This is one way of reducing the risk of misleading the public, as the business title could imply that it relates to midwifery services or products.

A brief history of UK midwifery regulation

The first Midwives Act in the UK was passed in 1902. This Act of Parliament was not initiated by the Government of the time but was promoted by individual Members of Parliament through Private Members’ Bills and supported in the House of Lords by others who supported midwife registration. The main provisions of the Midwives Act 1902 were as follows:

The Midwives Act 1902 established the Central Midwives Board (CMB) with jurisdiction over midwives in England and Wales. This was followed by The Midwives (Scotland) Act 1915 and The Midwives Act (Ireland) 1918, which established similar bodies in Scotland and Ireland. In Northern Ireland, the Joint Nurses and Midwives Council (Northern Ireland) Act 1922 made provision for a Joint Council to take over responsibility for nurses and midwives, and the Nurses and Midwives (Northern Ireland) Act 1970 established the Northern Ireland Council for Nurses and Midwives (NICNM).

This meant that prior to 1983, four separate bodies were responsible for the regulation of midwifery in the UK. In the intervening years, the legislation was amended and changed to address the need for improved education of midwives and differences in healthcare and in some instances healthcare policy.

On 1 July 1983, the statutory control of the practice, education and supervision of midwives became the responsibility of the United Kingdom Central Council (The UKCC) and four National Boards for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting, one in each of the four countries of the UK. The primary legislation under the regulatory body previous to the NMC, the UKCC, was the two Nurses, Midwives and Health Visitors Acts 1979 and 1992. These two Acts were consolidated in the Nurses, Midwives and Health Visitors Act 1997.

During the 1990s, the government devolved power away from the UK parliament based in Westminster, to the other three countries of the UK so they could establish their own parliaments or assemblies. This devolution has not impacted greatly on the regulation of midwives as they are one of the established professions. The power to regulate established professions remains with the UK parliament at Westminster, advised by the Department of Health England. Only new health-related professions that may be established in the future will be exempt from this approach.

The NMC was established in 2002 by The Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001 and took over most of the functions of the UKCC and the four national boards. This reunited standards for education with standards for practice and supervision of midwives on a UK basis. The creation of this UK-wide regulatory body the Nursing and Midwifery Council was contrary to the trend of devolving powers to national parliaments.

The Nursing and Midwifery Council

The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) is the UK-wide regulator for two professions, nursing and midwifery. The primary purpose of the NMC is protection of the public and it does this through maintaining a register of all nurses, midwives and specialist community public health nurses eligible to practise within the UK and by setting standards for their education, training and conduct. As of March 2006, the number of midwives and nurses registered with the NMC was over 682 000, of whom approximately 43 000 were midwives (NMC 2007a).

The powers of the NMC are set out within the Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001 (The Order), which is the main legislation that lays out the NMC’s role and responsibilities. As was the case with the CMB and UKCC, one of the core functions of the NMC is to establish and improve standards of midwifery and nursing care in order to serve and protect the public.

The main purpose of The Order was to provide a stronger framework for public protection and to implement important reforms to the system of professional regulation. This was partially in response to increasing public concern in the UK with regard to health professions self-regulating, as there were fears in some quarters that professions were protecting themselves rather than protecting the public. The intent behind The Order was to make regulation simple, streamlined and more effective in dealing with the many complex issues affecting the modern day health services, users of the service and the key professions of nursing and midwifery so vital to it. The Order is not perfect however, and there remain anomalies that will need further legislative changes to improve systems. An example of this is the need to consolidate the processes involved in dealing with fitness to practise. At present, this is dealt with through three separate committees, but as a result of policy change that separates the regulators’ function of investigation and prosecution from that of hearing evidence and making judgements, there is a need to consolidate processes through one committee in the future.

Although most of the key functions that are needed for regulation of midwives and nurses remain unchanged, some important additions were included in the NMC’s remit. These include:

For midwifery, one of the key changes resulting from the Order concerned setting standards and providing advice and guidance for local supervising authorities (LSA) as this had been the responsibility of the four national boards.

The Order does give the NMC the power to delegate some functions should it wish. New standards for the monitoring of quality of education programmes came into effect across the UK in 2006 and responsibility for monitoring and reporting on these has been delegated to an independent monitoring agency. There are however, no provisions under The Order for the delegation of setting standards for the LSAs, a function which is seen by many as an effective mechanism for public protection.

The Register

The Register is the tool that enables the NMC to deliver protection of the public. It acts as a guarantee for the public that only those who are safe and competent to provide care can do so. Any midwife who wishes to practise in the UK must be a member of the NMC register otherwise she would be practising illegally.

At the present time, the Register is made up of three parts covering two professions. These are the Midwives part of the Register, the Nurses part of the Register and the Specialist Community Public Health Nurses part of the Register.

To gain entry to either the midwives’ or the nurses’ part of the register, an applicant must have completed successfully the relevant pre-registration education programme. They must have demonstrated that they have reached competence by the end of the programme and that they are of good health and good character. Entry to the specialist community public health part of the register cannot be made directly. This can only be achieved by midwives and nurses who hold registration and who have gone on to complete a specialist level qualification related to public health.

Every person holding registration has an individual personal identification number (PIN). This can be used by employers or members of the public to check with the NMC that the person holding the PIN is indeed on the NMC register and as such is fit for practice. The NMC is bound by law to make the register available for inspection by members of the public; however it is up to the Council to maintain and publish the register in a manner it considers appropriate.

Midwives who trained in the UK or in the European Union must apply to join the NMC Register before they can work as a midwife in the UK. Their pre-registration midwifery education programmes must have met the European requirements and as such can be recognized anywhere in the EU (EU 1980, amended 1989).

If a midwife trained outside the UK or European Union, then they must also apply to join the NMC Register before they can work as a midwife in the UK. As part of the application process, they must be able to demonstrate that their original midwifery programme has met the same standards that are required in the UK and that they hold competence in the English language to a high level. They must also have held registration and practised as a midwife in their original training country for a minimum of one year after gaining their original qualification as a midwife.

Once they have demonstrated to the regulator that they have met these requirements, then they will gain approval to complete an adaptation programme. Adaptation programmes are designed to help the midwife to practise in the context, culture and expectations of UK society and give the midwife an opportunity to demonstrate she is competent to provide midwifery care in the UK. When this has been completed successfully the midwife can then be signed off by a supervisor of midwives and a lead midwife for education as fit to join the NMC register.

All midwives wishing to practise in the UK have an additional legal requirement to give notice of their intention to practise (ITP) each year. This is done via statutory organizations called local supervising authorities (LSAs) who are obliged to inform the NMC when they have received notifications from midwives. The ITP notification is linked to the midwife’s registration at the NMC and it is illegal for any midwife to practise without having submitted her notification before she practises in any local supervising authority. The only exception to this would be if she had to provide unexpected emergency care to a woman somewhere in the UK, in which circumstance the ITP can be submitted retrospectively to the local supervising authority where the emergency took place. The link between ITP notification and registration means that this is one way of monitoring whether a midwife has met the practice requirements for maintaining her registration. If a midwife has not submitted her notification of intention to practise, anyone checking her registration status will be informed that the legal requirement has not been met.

Statutory instruments

The next section describes the process involved in creating regulatory documents and standards. To aid understanding, specific legislation affecting midwives in the UK has been used as an illustration.

One of the first principles to understand is that there is a hierarchy in both the type of statutory legislation and the language used within legislation. This hierarchy imposes different levels of compulsion on the organizations and individuals affected by the legislation. All legislation is divided into primary and secondary legislation, with differences between the two.

The Nursing and Midwifery Order

This is the main legislation that established the NMC. It is a Statutory Instrument (SI) made under Section 60 of the Health Act 1999 and, within the NMC, is generally referred to as ‘The Order’.

The Order sets out what the Council is required to do (shall) and provides permissive powers for things that it can choose to do if it so wishes (may). The numbered paragraphs within The Order are referred to as Articles (Newton 2006).

Primary legislation is enshrined in Acts of Parliament, which have been debated in the House of Commons and the House of Lords before receiving the Royal Assent. Such legislation is expected to last at least one or two decades before being revised. With the pressure that exists on parliamentary time, Acts of Parliament are frequently designed as ‘enabling legislation’ in that they provide a framework from which statutory rules may be derived, otherwise known as secondary or subordinate legislation. All secondary legislation is published in statutory instruments (Newton 2006).

Statutory Rules (secondary legislation) do not generally require parliamentary time as they were in the past, when agreed, endorsed by the Secretary of State. This function was transferred to the Privy Council, who lay the Rules before the House of Commons for formal and generally, automatic approval (Box 7.1). Statutory rules can in theory be implemented or amended much more quickly than is the case for primary legislation, though at best this will take several weeks or months.

Box 7.1 Statutory Instruments implementing the Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001

The Statutory Instruments implementing the Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001 are all made by order of the Privy Council and fall into two categories:

To make matters more complex however, the Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001 is neither of the above. It came into being under what is known as the affirmative Order procedure. The affirmative Order procedure is an ancient and infrequently used law-making process with its roots going as far back as to Henry VIII. Because of this association, it is sometimes known as the Henry VIII rule. It differs from primary legislation in that although it also receives Royal assent, unlike primary legislation, it is not debated in either the House of Commons or the House of Lords. This procedure is more amenable for rule amendments without the need for a major discussion and passage through the Parliamentary process. Statutory rules can emanate from an Order and this is an important difference between an Order and secondary rules.

Although the affirmative Order procedure shares many similarities with secondary legislation, which as has been noted are published in statutory instruments, there is an important difference between the two: The Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001 has written within it secondary law-making powers, which will be made by statutory instruments. For example, the latest Midwives Rules came about via statutory instruments, as did the NMC Rules and procedures governing fitness to practise. There are a number of other Rules all made by Statutory instruments, such as the rules necessary to establish the professional register and those brought in for election to the Council that took over in 2005 (Newton 2006).

Affirmative Orders have, in common with secondary rules, the facility to adapt, amend and implement rule changes more quickly than an Act of Parliament. Their appeal for the government of the UK in a time of rapidly changing health and social scene may well lie in their amenability to be changed quickly and bypass lengthy Parliamentary procedures.

The progress of The Order in all other ways was akin to the way statutory rules are made. The draft order was ‘laid’ before each House of Parliament for a period of one month. Though points for clarification and objections could be raised, there could be no amendments once it was ‘laid’ and had to be accepted in its entirety (Table 7.1).

Table 7.1 Matters determined by the Privy Council

| SI number | Title | Came into effect |

|---|---|---|

| 2004/1762 | The Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001 (Transitional Provisions) Order of Council 2004 | 1 August 2004 |

| 2004/1763 | Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001 (Legal Assessors) Order of Council 2004 | 1 August 2004 |

| 2004/1765 | Nurses and Midwives (Parts of and Entries in the Register) Order of Council 2004 | 1 August 2004 |

| 2004/1766 | European Nursing and Midwifery Qualifications Designation Order of Council 2004 | 1 August 2004 |

| 2004/1771 | The Health Act 1999 (Consequential Amendments) (Nursing and Midwifery) Order 2004 | 1 August 2004 |

Section 60 orders

Amendments to The Order have to be made by means of another order made under Section 60 of the Health Act 1999, known as a Section 60 Order.

A Section 60 Order is drafted by the Department of Health. It is subject to consultation and may be amended before being laid before Parliament. It is then subject to debate in both Houses and, once approved, is presented to Her Majesty in Council for the Order to be made. This is known as the affirmative resolution procedure.

Rules

The Order requires the Council, which is in effect the board of trustees of the NMC, to stipulate various matters. Examples of these are:

These matters must be included in the Rules and the responsibility for approving these Rules cannot be delegated by the Council. This is why, when the statutory midwifery committee of the NMC makes a decision relating to midwifery education, practice or supervision, it has to be approved by the Council before it comes into effect.

Some rules apply to all nurses as well as all midwives on the NMC Register. Examples of these are:

The process for making rules

Any underlying policy that may result in amendments to Rules or Standards is developed by NMC staff and overseen by the relevant committee. For midwifery, this work is normally carried out within the midwifery department of the NMC and is overseen by the midwifery committee.

The NMC has a duty to consult on all its policy and standards and this is a requirement on the NMC enshrined within The Order. Consultation is an interesting concept; it can range from discussions, to inform thinking about potential policy change through to seeking advice from experts to define policy.

The NMC uses a variety of methods to consult and in relation to midwifery policy starts consultation at early stages in development work. This is achieved by involving midwives and women using maternity services at the beginning of a piece of work to help shape the broad content of any standards or guidance. The NMC may then go on to invite individuals with acknowledged expertise to participate in working groups to refine this work before then going out to a more formal public consultation if the outcome of work involves significant change to the existing standards of midwifery practice.

Formal consultations can be paper-based question and answer forms, web-based on line questionnaires or via facilitated focus groups. The NMC uses focus groups to ensure that more in depth views are gained on profession-specific matters such as the standards for the preparation and practice of supervisors of midwives. Midwives, members of the public and others can apply to join focus group consultations to discuss and feedback their views on any proposed standards or policy.

Ultimately, any decisions on new standards or policy are made by the regulatory body. The information gained through consultation helps the NMC to understand any impact that its decisions may have, and is likely to influence the content of any standards that may result. Not everyone will be happy about every standard or change that may be required by the NMC. Midwives can influence the outcome of the work of the NMC by participating in its work and by responding to consultations so that their views become known.

Once a consultation is concluded, the NMC considers the feedback from this and then the Rules are drafted by solicitors instructed by the NMC. This can take several drafts to ensure that the intent is not lost when translated into the obligatory legal language.

The proposed rules are then subject to approval by the Privy Council which acts on the advice of solicitors from the Department of Health. The final version of the rules is then ‘made’ (approved) by the Council. Once that is achieved the rules are signed by the Chief Executive and Registrar of the NMC and the President of the NMC. The official seal of the NMC is then applied to the document, the original copy of which is stored within the NMC vaults (see Table 7.2 for examples of rules).

Table 7.2 Rules made by the NMC

| Number | Title | Came into effect |

|---|---|---|

| 2003/1738 | Nursing and Midwifery Council (Practice Committees) (Interim Constitution) Rules Order of Council 2003 | 4 August 2003 |

| 2004/1654 | Nursing and Midwifery Council (Fees) Rules Order of Council 2004 | 1 August 2004 |

| 2004/1761 | Nursing and Midwifery Council (Fitness to Practise) Rules Order of Council 2004 | 1 August 2004 |

| 2004/1764 | Nursing and Midwifery Council (Midwives) Rules Order of Council 2004 | 1 August 2004 |

| 2004/1767 | Nursing and Midwifery Council (Education, Registration and Registration Appeals) Rules Order of Council 2004 | 1 August 2004 |

| 2005/2250 | Nursing and Midwifery Council (Election Scheme) Rules Order of Council 2005 | 12 September 2005 |

| 2005/3353 | Nursing and Midwifery Council (Fees) (Amendment) Rules Order of Council 2005 | 1 January 2006 |

| 2005/3354 | Nursing and Midwifery Council (Education, Registration and Registration Appeals) (Amendment) Rules Order of Council 2005 | 1 January 2006 |

Amendments to an existing set of rules have to be made by means of another set of Amendment Rules and the process for preparing and making Amendment Rules is the same.

Making rules is a long process which takes many, many months to complete because of the time taken to agree policy, consult and amend policy if needed and draft and lay the rules before parliament. For this reason The Order enabled the NMC to set many of its requirements within standards, and these are developed in a slightly different way to rules in the hierarchy of legislation. Standards are as binding on the education, practice and behaviour of midwives as rules but in theory are easier to amend if change is needed.

Standards

The Order requires the Council to establish standards in relation to various aspects of its functions, for example:

The NMC is required to consult before establishing any standards in the same way as for Rules and before it publishes the standards. The final version of any standards are agreed by the midwifery committee and approved by Council before they come into effect. Standards should be considered as ‘must do’ in terms of midwifery education, practice and supervision.

Guidance

The Order requires the NMC to give guidance on a number of matters, for example:

Again the NMC is required to consult before giving any guidance and to publish that guidance, and similarly, the power to approve and amend guidance rests with the Council. Such guidance gives direction and is considered as a level of practice or behaviour that is expected of all midwives. In regulatory terms it is not something that can be considered as only advisory or useful information. As such NMC guidance can be considered by a conduct panel when assessing a midwife’s fitness to remain on the Register should any allegations be made against her.

Advice

In addition to the statutory requirements upon the regulator in the UK to provide guidance for practice, the NMC is also required to provide help and advice to midwives that relates to their professional responsibilities in practice. This may be very different in approach to advice gained from a professional representative organization such as the Royal College of Midwives. Advice from the regulator will be based on the rules and standards for midwifery practice and will include where appropriate ethical consideration of the situations midwives may find themselves in. The regulator would not however, offer advice on employment matters or advice on how maternity services could be provided as this is outwith its remit.

The NMC publishes advice from time to time on a range of subjects that affect regulation, education or practice. Examples of these include:

The content of this type of NMC advice is not required to be consulted on, although in practice it may be in a limited way. One way of achieving this is to develop such advice with input from other organizations or representatives such as the UK-wide local supervising authority midwifery officers’ forum, or with representatives of women’s groups such as the National Childbirth Trust.

Such advice is published via NMC circulars as is the information to external organizations that changes in standards are about to come into place. Copies of this type of advice can be obtained from the NMC via its website www.nmc-uk.org. If a professional situation is more complex, a midwife can ask for personal advice by using the NMC’s professional advisory service.

The Midwives Rules and Standards

The Midwives Rules and Standards are specific to the midwifery profession and are developed through the midwifery committee and approved by the Council. The powers that enable the development of these statutory instruments are set by The Order in Articles 41, 42 and 43.

Article 41 defines the role and scope of the midwifery committee and the obligation that the Council has to consult with the committee on any of its work that affects midwifery. This places the midwifery committee in a very powerful position on behalf of the midwifery profession. At present the committee is made up of two practising midwives from each of the four countries of the UK and two lay members of Council. In addition the committee has co-opted three lay members from women’s representative organizations to assist its work and decision-making.

Article 42 relates to midwifery practice and allows the NMC to make rules specifically to regulate midwifery practice beyond those rules that affect all midwives and nurses. The Order empowers the NMC to draw up secondary legislation in the form of rules. Midwives rules are passed under this procedure and the rules referred to in this article were made by Statutory Instrument (NMC 2004).

It was the practice with previous regulatory bodies for the midwives rules to be supplemented by a code of practice. These codes did not have a legal status, although they did provide information intended to assist safe practice. This approach was changed by the NMC, which has included standards and guidance within the statutory instrument known as the Midwives rules and standards.

Article 42 has two parts. Part one empowers Council to regulate the practice of midwifery with rules that may address:

Part two relates to the local supervising authorities and their obligation to inform the Council of any midwives notifying them of their intention to practise.

Article 43 relates to local supervision of midwives and gives the Council the power to set standards in relation to supervision. This is also the section that deals with referral of midwives to the NMC if there are concerns about their fitness to practise and enables the supervising authorities to suspend midwives from practice if there is a significant risk to the public were they to remain able to practise.

The regulator has used the permissive powers it has within The Order to describe rules and more detailed standards on all of these areas that have a significant impact on midwifery. These statutory requirements can be viewed as enabling midwifery practice, so that the scope and input of midwives and midwifery with women can be developed and expanded to meet the changing needs and expectations of society. Conversely, some may choose to use them in a restrictive way to impede practice or healthy change, which was not the intent of the regulatory body.

Offences

There are some interesting inclusions in The Order that mean that anyone breaching the requirements of The Order could be liable for criminal prosecution, and one relates specifically to midwifery.

Article 45 is an important three-part section within The Order and defines who may provide care for a woman during childbirth. Childbirth has a statutory definition within the Midwives rules and standards and therefore includes pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period.

Parts one and two state that only a registered midwife or a registered medical practitioner, or a student midwife or a medical student as part of a statutorily recognized course, may attend a woman in childbirth. There is immunity for anyone acting to help a woman or baby in a sudden emergency. Outside these categories, anyone attending or assuming responsibility for care is committing an offence.

Part three describes the penalty involved if convicted, which is a fine not exceeding level 5 on the standard scale (to a maximum of £5000) to anyone who contravenes this Article. The fine was raised from level 4 in the previous legislation under the UKCC to reflect the seriousness of this issue.

This restriction was retained in spite of representation by women’s groups for a fine for this offence to be dropped altogether. The Association for the Improvement in Maternity Services (AIMS) took the view that, given the debate about midwifery attendance at home births in the late 1990s, a woman may at least have the attendance of a partner, or as a last resort a relative, in cases where a woman wanting to give birth at home has no qualified midwife available to attend her. AIMS argued that having someone unqualified is better than having no one in attendance at all. During the House of Lords debate (Hansard 2001), Lord Hunt stated that the point of the offence is to protect the function of midwifery in the interest of public safety, an offence that has been in force in the UK since the first Midwives Act of 1902.

Employers and protection of the public

As has been discussed previously, protection of the public is best achieved through a joint approach to regulation. This means that employers have a vital role in ensuring that midwives working for them have the appropriate skills and knowledge for the job and hold current registration with the NMC. If an employer does not have robust systems in place for ensuring that their midwives have met the statutory requirements including active midwifery registration then they may be putting the women and babies they are providing care for at risk.

The employer’s role in protection of the public starts when they recruit staff and good employment practices protect the midwife too. The employer should take up references from any previous employer to ensure that there were no concerns about the safety of practice or good character of the applicant in previous roles. Any employer considering a midwife should also ensure that registration is in place by checking the NMC Register and carry out a criminal records check to ensure that the person is not barred from caring for vulnerable children or adults. New legislation has been created in England through the Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act 2006 (DH 2006) and in Scotland through the Protection of Vulnerable Groups (Scotland) Act 2007 (DH 2007a) to strengthen requirements relating to care of vulnerable children and adults.

Finally employment in any area related to midwifery advice or practice should not start until it has been confirmed that the midwife has submitted her notification of intention to practise to the local supervising authority.

Each midwife is personally responsible for keeping herself up-to-date and competent. Although not a statutory requirement upon employers, it is in the employers’ interest to support midwives to achieve this. Safe and competent midwives reduce the risk to the employer that poor practice may occur. It also increases the likelihood that the employer is providing a safe system of care to women and their families. Of course this does not just relate to providing midwives with time and access to ongoing professional and personal development. This includes provision of safe working environments and staffing levels that reduce the risk of things going wrong.

Employers who engage with supervision of midwifery in an active and positive way by working collaboratively and supportively with the local supervising authority and supervisors of midwives will reduce risk as this will strengthen their clinical governance systems.

Robust Human Resource systems to ensure regular (at least annual) registration checks will ensure that only those who have met requirements for safe and competent practice are providing care and have continued registration. Human error does occur in relation to maintaining registration and good employment processes will act as ‘belt and braces’ for safety for the employer. Any insurance scheme (see Ch. 53) that may protect the organization financially in the event of litigation against poor practice would be invalidated should an individual midwife have allowed her registration to lapse, regardless of why this may have occurred.

This is perhaps the opportunity to consider the matter of personal indemnity insurance. Indemnity insurance protects the midwife herself, and offers a degree of financial security for the woman and her baby should things go wrong. There may be a need for financial compensation to cover the costs of ongoing care if it is needed. As most midwives are employed by organizations this is rarely a problem as the employer usually holds vicarious liability for the midwife’s practice and therefore provides indemnity through its insurers. It remains a problem for midwives who practise on a self employed basis, as there is no indemnity insurance cover available to them through existing insurance companies.

While recognizing the dilemma for self-employed midwives, the NMC recommends that all midwives hold professional indemnity insurance. If this proves not to be the case the midwife is expected to inform the woman about the lack of insurance and what the implications of that might be. This will enable the woman to choose to continue care with that midwife or to move to alternative midwifery care where insurance is available. The midwife is expected to record that she has given the information on this matter and its implications, within the woman’s maternity records.

Dealing with poor practice

There is a perception among many midwives that the regulator only deals with misconduct. While this is a very important part of the regulator’s role, and one which uses the largest part of its annual budget, it is relevant only to a very small minority of midwives on the NMC Register. This is because the majority of midwives practise safely and within the scope of their skills and knowledge to the required standards, often despite restrictions in resources, or increasingly complex caseloads within their employment.

As at 2008, the NMC receives approximately 1600 complaints against nurses and midwives per year and of those, approximately 100 are about midwives. When this is considered against the 43 000 midwives on the Register, it can be seen that the numbers referred to the NMC are actually very small. Allegations against midwives come from a variety of sources (Box 7.2).

The NMC will not deal with allegations against anyone on its Register unless two criteria are fulfilled. The complaint must be made in writing by a named person or representative of an organization and it must be made ‘in the form required’. This means that the allegation must contain essential information about where and when an incident or pattern of events took place and who was involved. Further information on what is required can be downloaded from the NMC website on www.nmc-uk.org and is in a slightly different form for employers or the LSA than if an allegation is being made by a member of the public who may not have access to some information, such as PINs or the midwife’s name.

Once an allegation is received in the form required, NMC staff carry out further investigation before a case can be brought to a committee who will consider whether there is a case to answer or not. The information from the investigation is collated and will include:

Previous UK regulators could only deal with allegations of misconduct or ill health that were so serious that they might lead to suspension or removal from the Register. For this reason a number of complaints made about individual midwives were not progressed by the UKCC. This situation changed on 1 August 2004 as the NMC powers to deal with fitness to practise were extended to include lack of competence. The range of sanctions available to the NMC were also extended, giving conduct panels much more scope to deal with matters of concern than had previously been the case. This increased the number of cases going forward for consideration by a conduct panel. These sanctions are to:

A significant change that is likely to increase the number of referrals to the NMC relates to the burden of proof that an investigating or conduct panel must consider. Until 2007, this was set at the same level as for criminal cases heard in the UK courts and was that the allegation must have been proved beyond all reasonable doubt.

This is changing and will move in 2008 to what is called a civil standard of proof. This means that the evidence supporting the allegation is judged on a balance of probability that the midwife’s care or behaviour did not meet the required practice standards or Code of conduct set by the regulator. While this change has caused some anxiety among the professional organizations representing midwives, it has enhanced the public’s belief that a regulator will protect them from poor practice as the priority.

Any midwife who has had an allegation made against her will be made aware that this is the case by the NMC so she can provide her evidence to the investigation or to the conduct panel who are considering any allegations made against her. The midwife’s conduct will be measured against the standards of education, practice and conduct required when the incident took place.

Suspension from midwifery practice

It may be appropriate to consider suspension from midwifery practice in the context of dealing with poor practice. There are only two organizations that can suspend a midwife from practice in the UK. These are the NMC or a local supervising authority, and in both cases the suspension means the midwife cannot practise anywhere in the UK whilst the suspension is in place. An employer may suspend a midwife from duty to enable it to conduct an investigation but that would not prevent the midwife from practising elsewhere, however unwise that might be.

Suspension from practice is a very serious matter as it could prevent a midwife from earning a living and is therefore not a step that is taken lightly (NMC 2007b). It would only be used if there was evidence of significant risk to the public were the midwife to continue to practise. This may be for reasons of the midwife’s ill health, chronic lack of competence or gross professional misconduct.

If a local supervising authority decides to suspend a midwife from practice, it must make a formal referral to the NMC and include all the information gained from the supervisory or LSA investigation that led to the decision to suspend from practice. The LSA suspension is immediate in effect and the NMC will make a note on the midwife’s registration to indicate this is the case. The LSA is also obliged to share this information with the midwife concerned so that she is aware what is happening.

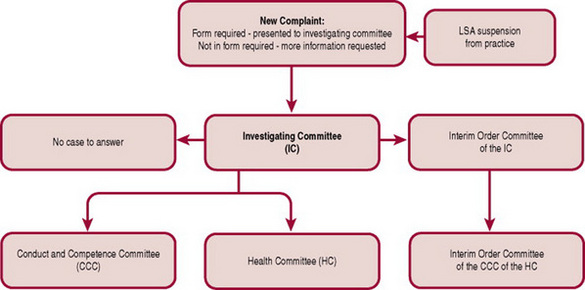

The NMC will set up an interim orders hearing to review the LSA suspension. If it upholds the decision to continue the suspension from practice it will replace the LSA suspension with an interim suspension order. The NMC can also decide on review of the evidence that suspension is not required and may replace it with an interim condition of practice order which will restrict the way the midwife can practice. It can also overturn the suspension from practice if it decides that the risk to the public is not high enough to warrant suspension (Fig. 7.1).

Should new evidence become available to the local supervising authority that imposed the suspension, and it concludes that suspension is no longer warranted, it can lift its suspension and inform the NMC who will take this into account in relation to any interim order for suspension.

Regardless of the outcome from the interim orders hearing, the NMC will continue to investigate the allegations against the midwife until such time as it can make a judgement about whether or not there is a case to answer.

Regulation of midwifery education

The regulatory framework relating to education is enshrined within Articles 15–20 of The Order, and is a key function of the NMC. Monitoring of the quality of education used to sit with the four national boards but is now the remit of the NMC and is known as the quality assurance process. This is one of the areas where The Order allows the Council to delegate its function. The Council has set its rules and standards for the content, length and delivery of pre-registration midwifery education programmes and it contracts with external agencies to monitor that its requirements are being met.

There is no specific requirement under The Order for midwifery education to come under the remit of the midwifery committee. During the consultation phase of the draft Orders, this non-inclusion of midwifery education in the midwifery committee’s remit caused a great deal of concern to organizations representing midwifery, such as the RCM. They argued that one of the basics of autonomy of any profession includes having control of educating and training its members. Although the final Order did not reflect this wish, the first Council of the NMC decided that the Midwifery Committee would have included in its remit, matters relating to midwifery education (Newton 2006).

How is regulation monitored?

In the UK, all healthcare regulatory bodies, including the NMC, are monitored by an overarching body called the Council for Healthcare Regulatory Excellence (CHRE). Each regulator has to report on its progress against performance objectives each year to the CHRE. The CHRE in turn publishes an annual report describing and commenting on its findings, highlighting any good practice it finds and recommending any changes it thinks needs to be made to improve the function of the healthcare regulators (www.chre.org.uk).

The CHRE has the power to review any decisions made by a regulator in relation to its fitness to practise proceedings if it thinks that the decision has been too lenient. Should this be the case, then the CHRE can refer the case for judicial review, which is a very costly process for the regulator involved both in financial and reputation terms. The NMC tries to ensure this does not happen by being rigorous in its selection and training of anyone sitting on its conduct panels as well as by setting clear standards about what is expected of midwives on its Register. It also ensures than any conduct panel considering allegations about midwifery practice includes an experienced practising midwife.

Statutory supervision of midwives

The main purpose of statutory supervision of midwives (see Ch. 52) is protection of the public. In this, supervision of midwives reflects the primary purpose of the UK regulatory body. Supervision of midwives was enshrined within statute to reflect its purpose and value in ensuring safe standards of care to women and their families.

Supervision of midwives is independent of any employment situation and all midwives in the UK, regardless of type or place of work, must comply with statutory supervision.

The local supervising authorities (LSAs) are statutory entities that are required to ensure that supervision of midwifery takes place and that midwifery practice is safe, evidence based and meets NMC standards. They are responsible for appointing and ensuring there are enough supervisors of midwives in the area they are responsible for. They also appoint the local supervising authority midwifery officers. The responsibility for the LSA is different in each of the four countries.

The standards expected of all LSAs are set by the NMC, and this power is enabled by Article 43 of The Order. This Article details how LSAs are to exercise general supervision over all midwives practising within their area according to the Council’s rules. It also requires them to report to the NMC any situation where the LSA is of the opinion that the fitness to practise of a midwife in its area is impaired.

Part two of this Article requires the NMC to stipulate the qualifications of individuals whom the LSA can appoint as supervisors of midwives, and these are set out in rule 11 of the midwives rules and within the NMC standards for supervisors of midwives (NMC 2007c).

Continuous professional development

All midwives are expected to maintain and develop their skills and competence (NMC 2008b). The Order requires the NMC to make rules regarding the standards midwives need to meet with respect to their continuing professional development, and there are implications of failure to comply with the requirements for their registration status if a midwife does not meet these standards. The current standards for maintaining registration inherited by the NMC are too vague to offer real protection to women and the need for development of a new post-registration framework is one of the major issues passed from the UKCC to the NMC.

The NMC has started to review the requirements that midwives will have to meet in order to stay on the register in future. These will focus on maintaining and demonstrating competence with protecting the woman from possible poor practice as the priority. This is a radical change in approach from one that focuses on the personal development wishes of the individual midwife as the priority; however there is a balance to be achieved between both groups.

The development of this programme of regulation is also likely to result in changes to the format and structure of the Register itself so that it becomes more meaningful in terms of the skills and abilities of those with specialist interests who hold registration. Much of this change has been led by the profession itself, however there are significant political policy changes that are considered in the final section of this chapter.

‘Trust, Assurance and Safety – The Regulation of Health Professionals in the 21st Century’

Regulation is not static and for midwives it has evolved continuously since its inception in 1902. Events in the UK during the late 1990s have increased public anxiety about professional self-regulation. Several public enquiries were held and reports published that made recommendations for changes in the regulators and regulation across the UK. This culminated in two government consultations during 2006 that looked at the regulation of medical and non medical health professionals. February 2007 saw the publication of a White Paper, Trust, Assurance and Safety – The Regulation of Health Professionals in the 21st Century (DH 2007b) describing proposed changes to all of the healthcare regulators and regulation in the UK, and two other documents, Safeguarding Patients (DH 2007c) and Learning from Tragedy, Keeping Patients Safe (DH 2007d). Although the impetus for change was primarily focused on medical regulation, the impact will be felt across all healthcare regulators and will mean significant change for the NMC and the regulation of midwives.

The key principles within the White Paper that will underpin statutory professional regulation for the future were described by Patricia Hewitt MP in 2007 when she was Secretary of State for Health. These are:

These principles underpin significant changes to the concept and process of self-regulation of midwives by midwives and will completely redefine how the NMC is structured and governed. Many of the changes will require primary and secondary legislative changes and as described previously, some will take many years to achieve.

There are seven main areas that will require change for most regulatory bodies:

It is proposed that all regulators including the NMC increase their independence and impartiality. For the NMC this means that the current balance between lay and registrant Council members will change to an equal number of each and the overall size of the Council reduce. Some have described this change as the Council becoming more board-like although it has proved difficult to determine what this will mean in reality. It is likely to reduce the level of detailed input by Council members to the operational work of the regulator and increase the level of strategic governance of senior executive staff as a result. In future all members of the Council will be independently appointed, rather than the mix of elected registrant members and appointed lay members that exists at present. This may be the greatest challenge for the profession as it brings the whole concept of self-regulation into question for the future.

Regulatory Councils will become more accountable directly to Parliament and devolved administrations rather than as currently to the Department of Health. This will increase the regulators’ ability to take an impartial view on standards that may be required to improve practice and safety.

Within the White Paper, there is a large emphasis on all healthcare regulators becoming more consistent in their approach. This would make some sense certainly for the public, who may have to interact with several regulatory bodies should they wish to explore the practice standards of all the healthcare professionals involved in their care. This is likely to impact particularly in areas such as entry requirements for pre-registration programmes, requirements for maintaining registration and inter-regulatory approaches to entries on professional registers denoting specialist level qualifications.

The current NMC registration renewal period is 3 years, however this may change to come in line with the majority of other regulators who have 5-year periods for the same matter. These types of issues are being discussed at the present time within a number of inter-regulatory working groups who will advise on the future pattern for all.

The concept of a licence to practise for doctors has emerged, not entirely alien to midwives with their intention to practise notification and PREP requirement systems. This may be based on an objective process for formatively and summatively appraising continued fitness to practise and may well contain differing elements for those healthcare professionals engaged in areas of care that are considered higher risk than others (Hampton 2006). Examples of this might be midwives or doctors who are working in isolation from peer support and overview. It appears inevitable that the requirements for midwives to demonstrate continued competence and updating to enable them to maintain registration will be strengthened and will need to be consistent in approach with other regulators and professions. This is likely to be a large and thorny area of change in regulation terms and is likely to take several years to develop before change is implemented.

Midwives will recognize elements of the supervision framework in the proposals to create ‘medical affiliates’ appointed and accountable to the General Medical Council. The intent behind this is closer monitoring of medical practice on a local level and provision of advice and support to employers in managing concerns about medical practice.

As mentioned previously, the standard of proof will change to that of a civil standard and will apply across all regulators in the UK, as will change to the approach when handling allegations against registrants that they are not fit to practise. The NMC has already moved in this direction and its approach has been validated by the contents of the White Paper proposals. There will be a separation between investigations of allegations against midwives and considering and judging a case against a midwife. This means the NMC will move from handling all aspects of the process to one of investigation and prosecution, a system that will seem more akin to the current UK law court system.

Professional indemnity insurance is likely to become mandatory for all health professionals within the next 5 years. It remains to be seen if this marks the end of self-employment opportunities for midwives or whether creative solutions that retain the expertise of midwifery within independent practice can be developed to enable women to continue to have access to this type of care provision.

The NMC will continue to have responsibility for setting the standards and requirements for midwifery education, however there is a greater emphasis on the role of employers in relation to testing for competence in English language amongst applicants for posts.

There will be changes to the Register in terms of entry requirements and the information held on the Register relating to individual midwives and nurses to enhance inter-regulator consistency. One area where work has commenced relates to a single definition of ‘good character’ that will be applied to all professional registers. This ties into proposals to strengthen links between student midwives and the midwives part of the register and whether there should be a more formal relationship between students and the regulator before qualification.

Regulation of existing healthcare professions is a retained function that sits with the parliament at Westminster and is not devolved to the new administrations in Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland. There are a number of professional groups who are not statutorily regulated at the present time and some of these are potentially as risky to the public as the established professions. Such groups are likely to have statutory regulation introduced to set and monitor standards in the same way as midwifery experienced in 1902. There is also consideration of emerging professions and whether they should be regulated or not. One decision has been made and that is not to create new regulatory bodies but to use one or more of the existing regulators to take on this function. It remains to be seen whether maternity support workers will be included in such regulation and if so whether they share regulation with midwives or elsewhere with other healthcare professionals.

The White Paper is intended to create a ‘lasting settlement’ for professional regulation in the UK. Given the rapid and continuous change in society and the expectations of society this is a high aspiration and one, given the history of midwifery regulation over the past 105 years, is unlikely. Midwives need to understand regulation and how it is achieved so they can continue to influence the policy makers about requirements and standards for their profession as they have always done with the needs of women at the centre.

Blunden F. Extracts from the key speakers address at the NMC Annual Lecture, 2007. Cardiff

Cowell B, Wainwright D. Behind the blue door: the history of the Royal College of Midwives. London: Baillière Tindall, 1981.

Department of Health. Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act. Norwich: The Stationery Office, 2006.

Department of Health. Protection of Vulnerable Groups (Scotland). Norwich: The Stationery Office, 2007.

Department of Health. Trust, Assurance and Safety – The Regulation of Health Professionals in the 21st Century. Norwich: The Stationery Office, 2007.

Department of Health. Safeguarding Patients. Norwich: The Stationery Office, 2007.

Department of Health. Learning from tragedy, keeping patients safe. Norwich: The Stationery Office, 2007.

Donnison J. Midwives and medical men, a history of the struggle for the control of childbirth, 2nd edn. Wakefield: Historical Publications, 1988.

EU (European Union). Midwives Directive 80/155EEC Article 4 amended by the European Union Directive 89/594/EEC. Brussels: EU, 1980.

Hampton P. Reducing administrative burdens: effective inspections and enforcement. London: HM Treasury, 2006.

Health Act. HMSO, London, 1999.

Heagerty BV. Reassuring the guilty: the Midwives Act and control of English midwives in the early 20th century. In: Kirkham M, editor. Supervision of midwives. Hale: Books for midwives Press, 1996.

Hogg C. Professional self-regulation: a patient centred approach. A consultation document. London: Consumers’ Association, 2000.

Kennedy I. Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry 2001. Learning from Bristol. The report of the public inquiry into children’s heart surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary, 1984–1995. TSO, London, 2001.

Newton J. Overview of current NMC legislation. Council Members Handbook. NMC, London, 2006.

NHS Employers. Maternity support workers: Enhancing the work of maternity teams. London: NHS, 2005.

NMC. Midwives rules and standards. London: NMC, 2004.

NMC. The PREP handbook. London: NMC, 2008.

NMC. Statistical analysis of the Register April 2005–March 2006. London: NMC, 2007.

NMC. Fitness to practise annual report 2005–2006. London: NMC, 2007.

NMC. Standards for supervision of midwives. London: NMC, 2007.

NMC. The Code: Standards of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives. London: NMC, 2008.

RCM. Report of the Royal College of Midwives commission on legislation relating to midwives. London: RCM, 1991.

Sandall J, Manthorpe J, Mansfield A, et al. Support workers in maternity services: a national scoping study of NHS Trusts providing care in England. London: Kings College, 2006.

The Midwives Act. HMSO, London, 1902.

The Midwives (Scotland) Act. HMSO, London, 1915.

The Midwives Act (Ireland). HMSO, London, 1918.

The Nurses, Midwives and Health Visitors Act 1979, 1992. HMSO, London, 1997.

The Nursing and Midwifery Order. The Stationery Office, Norwich, 2001.

Towler J, Bramall J. Midwives in history and society. England: Croom Helm, 1986.