Chapter 32 Assisted births

This chapter describes alternative methods of delivery that are used when the mother is unable to give birth without medical or surgical assistance. The role of the midwife will be explored and the importance of providing complete and comprehensive information to the woman will be emphasized.

Assisting birth

Assisted vaginal birth is a frequently and widely practiced intervention in maternity settings. This accounts for 11% of births in the UK (DH 2004). Stephenson (1992) reports that assisted vaginal delivery may be carried out as frequently as 15% in Australia and Canada. The discrepancy between the reported rates may be due to the variation in the management of birth. Johanson & Menon (1999) say that, in general, maternal outcomes would be improved by lowering instrumental birth rates. Women who use epidural as a form of pain relief are at increased risk of having an instrumental assisted birth (Anim-Somuah et al 2007).

Birth by ventouse

The ventouse is used more commonly than forceps in northern Europe and in Africa. The vacuum extractor is an instrument that applies traction. It can be used as an alternative to forceps. The cup cleaves to the baby’s scalp by suction and is used to assist maternal effort.

The use of the ventouse

The ventouse may be used when there is a delay in labour and as with forceps, the ventouse should be applied when the head is engaged and there is no cephalopelvic disproportion. It may be useful in the case of a second twin, when the head remains relatively high. It may be safer and simpler to use the ventouse in this event than forceps.

The ventouse has become more frequently employed by obstetricians due to its apparent increased safety and ease of use, when compared with forceps (Evans & Edelstone 2000). However, evidence shows similar degrees of complications resulting from ventouse births as compared with those where forceps are employed (Johanson et al 1995). Johanson & Menon (1999) conclude that the vacuum extractor is significantly less likely to achieve a successful vaginal delivery than forceps. Nevertheless, it is associated with lower caesarean section rate. Although the ventouse is associated with more cephalohaematoma, other facial and cranial injuries are more common with forceps.

Application of the cup

For successful use of the ventouse, it is essential to determine the whereabouts of the flexion point (Evans & Edelstone 2000). This point lies on the sagittal suture, about 3 cm anterior to the posterior fontanelle and 6 cm posterior to the anterior fontanelle. The cup is positioned over the sagittal suture. If this imperative is not respected, this will not allow flexion of the head and may even cause deflexion of the head, which may impede the birth. The vacuum within the cup will be achieved more readily in this way. It is important that the midwife has an understanding of this principle, as it is frequently the midwife who is called upon to manage the vacuum.

Soft and rigid vacuum extractor cups

The metal cups used are the Bird variety (Johanson & Menon 1999), or the Malstrom type (Evans & Edelstone 2000) and have a central traction chain and a vacuum conduit. These come in 4, 5 and 6 cm diameters. The preferred new silicone rubber cup is shaped to the contour of the baby’s head. This allows the cup to be placed further back on the baby’s head to increase flexion, reduce the diameter of the head and facilitate delivery (Fig. 32.1).

The advantage of the new malleable silicone cup is that it effects much less of a ‘chignon’ on the baby’s scalp (Miller & Hanretty 1997). Soft cups have a poorer success rate than metal cups, but are less likely to be associated with scalp trauma. Most of the research shows that the two main outcomes, the occurrence of trauma and the likelihood of vaginal delivery, have been well investigated. However, many studies have not considered other important maternal consequences such as the pain experienced, satisfaction or the mother’s anxiety about the baby (Johanson & Menon 1999).

Procedure

The woman is usually in the lithotomy position and the same precautions are observed as for a forceps birth. Local anaesthesia may be used or inhalational analgesia may be sufficient. Pudendal nerve block may be employed or epidural, if already in situ, may be topped up. Episiotomy is not routinely carried out.

The procedure is explained and consent obtained; then adequate analgesia is assured and the bladder is emptied. The fetal heart rate is recorded regularly. The cup of the ventouse is placed as near as possible to, or on, the flexing point of the fetal head. The vacuum in the cup is increased gradually so as to achieve a close application of this to the fetal head. Usually a vacuum of 0.8 kg/cm2 is reached, by an increase of 0.2 kg/cm2 in stages, or an increase from 0.2 to 0.8 kg/cm2 is achieved directly. When the vacuum is achieved, traction is applied with a contraction, with maternal effort, in an attempt to involve and include the woman in the birth. This traction is done in a downwards and backwards direction, then in a forwards and upwards manner, thus following the curve of Carus. The vacuum is released and the cup then removed at the crowning of the fetal head. The mother can then push the baby for the final part of the birth, thus involving her in this and giving the mother the opportunity to participate. This will result in a more satisfactory experience for the mother and the father.

Precautions in use

A useful mnemonic (AAFP 2000) is:

Complications

As the vacuum actually works by raising an artificial caput succedaneum, it is not logical to then say that caput is a complication of this intervention, as the aim is to form a chignon. However, prolonged traction will increase the likelihood of scalp abrasions, cephalohaematoma or subaponeurotic bleeding (Miller & Hanretty 1997).

Failure of the ventouse may arise in as much as 20% of cases (Drife 1996). This is more likely in the presence of excessive caput, and in the hands of less experienced practitioners. The role of the midwife is to improve the overall efficiency of the manoeuvre, and to support the mother and her partner.

The midwife ventouse practitioner

Some midwives feel that women will be better served by the midwife ventouse practitioner and embrace such innovations, whereas others see it as exceeding the limits of normal midwifery practice (Charles 1999). The fact is that, with the advancement of midwife-led care and the increased demand for less interference in the birth process and also the development of consultant midwives and other resource key persons, midwifery care is changing and developing. There was a similar reaction when midwives commenced suturing, and yet women have been well served by midwives carrying out this activity. The response of women has been positive, with continuity of care being confirmed as the main advantage (Mulholland 1997).

One advantage of the midwife ventouse practitioner role is that women are not traumatized by a change of carer as the midwife is able to provide the panoply of care required by the woman, and this at a very crucial and critical moment. Midwife ventouse practitioners must be well educated and trained before carrying out this procedure. There is more likelihood of the indication being maternal fatigue than for any other reason. Midwives in developing countries and in a few birth centres in the UK are already familiar with this technique.

Birth by forceps

Forceps are most commonly employed to expedite delivery of the fetal head or to protect the fetus or the mother, or both, from trauma and exhaustion. They are also used to assist the delivery of the after-coming head of the breech or to draw the head of the baby up and out of the pelvis at caesarean section birth.

Characteristics of obstetric forceps

Obstetric forceps are composed of two separate blades; a right and a left, and are identified on these as such. The forceps are inserted separately on each side of the head. The forceps are locked together by either an English or a Smellie lock. Rotational forceps have a sliding lock. The blades are spoon shaped (cephalic curve) to accommodate the form of the baby’s head and are fenestrated to minimize trauma to the baby’s head. In most modern obstetric forceps, the blade is attached to the handle at an angle that corresponds to the pelvic curve. When the blades are correctly positioned the handles will be neatly aligned in the hands of the doctor who applies them.

Classification of obstetric forceps

Forceps operations fall into two categories: low and mid-cavity. Low-cavity forceps are used when the head has reached the pelvic floor and is visible at the vulva. Mid-cavity forceps are used when the head is engaged and the leading part is below the level of the ischial spines. High-cavity forceps are now considered unsafe and a caesarean section will be carried out.

Types of obstetric forceps

Forceps are often described as non-rotational or rotational (Fig. 32.2). Adequate analgesia is required prior to their application to the fetal head.

From above: Kielland, Neville-Barnes and Simpson’s. Note the difference in cephalic curve. The rotational forceps (Kielland’s) have a long shaft and little pelvic curve.

Wrigley’s forceps

These are designed for use when the head is on the perineum. This is a short and light type of forceps, with both pelvic and cephalic curves and an English lock. They are also used for the after-coming head of a breech delivery, or at caesarean section.

Neville-Barnes or Simpson’s forceps

These are generally used for a low or mid cavity forceps delivery when the sagittal suture is in the anteroposterior diameter of the cavity/outlet of the pelvis. They have cephalic and pelvic curves and the handles are longer and heavier than those of the Wrigley’s. Anderson’s and Haig-Ferguson’s forceps are also similar in shape and size.

Kielland’s forceps

These were originally designed to deliver the fetal head at or above the pelvic brim. They are generally used for the rotation and extraction of the head that is arrested in the deep transverse or in the occipitoposterior position. The blades have little pelvic curve and are for traction. The shallow curve allows safe rotation of the forceps in the vagina. Downward traction encourages rotation of the head. The claw lock allows sliding and corrects asynclitism of the fetal head. These forceps should be used only by an obstetrician skilled in their application and use.

Indications for the use of obstetric forceps

The three main indications for the use of forceps are delay in the second stage of labour, fetal compromise and maternal distress.

Delay in the second stage of labour may be due to:

Prerequisites for forceps delivery

(see Mnemonic p. 609)

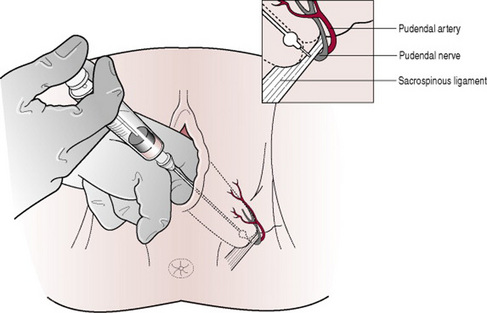

Pudendal block

This is the infiltration of the area around the pudendal nerve by local anaesthetic. The transvaginal route is used to locate the ischial spine, as the pudendal nerve emerges from vertebrae S2–S4 and crosses this. A particular needle that possesses a ring or guard is employed, called a pudendal block needle. About 10 mL of local anaesthetic, usually 1% lidocaine (lignocaine), is injected into the region just below the ischial spine (Fig. 32.3). Both motor and sensory nerves are affected as both lie in this region. The pudendal nerve supplies the levator ani muscles, also the deep and superficial perineal muscles (Stables & Rankin 2005). It may be used to provide analgesia for the lower vagina and perineum, and is therefore used for forceps and ventouse deliveries. The advantage of this technique is that it does not harm the baby.

Perineal infiltration

A local anaesthetic is used to infiltrate the perineum prior to episiotomy or suturing (see Ch. 28).

Technique

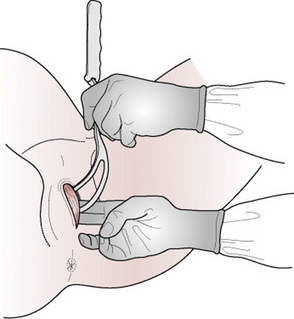

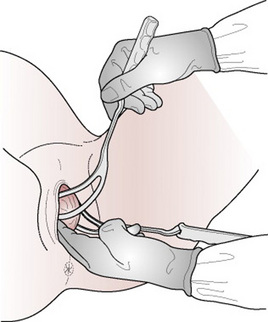

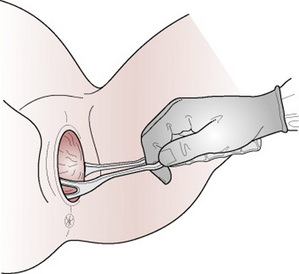

After careful vaginal examination, the presentation and position are identified. There must be no apparent obstruction. The membranes must be ruptured and full dilatation of the cervix must be confirmed. The head must be engaged and there should be no cephalopelvic disproportion. Episiotomy is not routinely carried out but the accoucheur will evaluate whether this accommodates the birth (Figs 32.4–32.7).

Complications

Neonatal

Neonatal complications (see Ch. 45) include:

Symphysiotomy

This is an incision of the fibrocartilage partly through the symphysis pubis and is performed in labour to enlarge the transverse diameter of the pelvis. It is rarely carried out in the UK, but is carried out in countries where the risk of caesarean section is particularly high for the management of cephalopelvic disproportion. A urinary catheter is inserted into the bladder to empty it and to displace the urethra laterally whilst the symphysis is being divided. The fibrocartilage is incised over the centre of the symphysis pubis. A vacuum extractor or forceps may be used to facilitate delivery. Following the operation a bandage is applied around the pelvis to provide support. The catheter may remain in situ for a few days, as oedema is likely.

Caesarean section

Caesarean section is described as being an operative procedure, which is carried out under anaesthesia whereby the fetus, placenta and membranes are delivered through an incision in the abdominal wall and the uterus. This is usually carried out after viability has been reached (i.e. 24 weeks’ gestation onwards).

The operative procedure

There are two layers of pelvic peritoneum and the non-gravid uterus is a pelvic organ closely covered by a layer of pelvic peritoneum. As pregnancy advances, the uterus grows up into the abdomen and this peritoneum rises up with the uterus and comes into contact with the abdominal peritoneum. Each of these layers must be incised. The abdominal peritoneum is situated below the abdominal muscle layer.

The operation most commonly carried out is the lower uterine segment caesarean section (LSCS). A Pfannenstiel or bikini line incision is usually performed. The lower segment incision is in the less muscular and active part of the uterus and heals better. The main reason for preferring the lower uterine segment technique is the reduced incidence of dehiscence of the uterine scar in subsequent pregnancy. A classical or vertical incision of the uterus may be the only choice in such situations as implantation of the placenta on the lower anterior uterine wall, in the presence of dense adhesions from previous surgery, or in the case of a large fetus with the shoulder impacted in the maternal pelvis. The risk and disadvantage of this is that the uterine incision is more likely to rupture during a subsequent birth.

The abdomen is opened and the loose fold of the peritoneum over the anterior aspect of the lower uterine segment and above the bladder is incised. The operator continues to incise this further, to visualize the fundus of the bladder, which is then pushed down and away from the surgeon. The uterus is incised transversely. The surgeon directs the fetal head out while the assistant applies fundal pressure to help the delivery of the baby. Oxytocics may be given by the anaesthetist after delivery of the baby and clamping of the cord. When the baby and placenta have been delivered, the uterus is sutured. This is usually done in two layers. The peritoneum may then be closed over the uterine wound to exclude it from the peritoneal cavity. The rectus sheath is closed, then the layer of fat and finally the skin is sutured with the surgeon’s choice of material; commonly Vicryl, a braided polyglactin preparation, is used for this.

Preparation

Preoperative preparation: an anaesthetic chart/preoperative assessment, weight and observations of blood pressure, pulse and temperature are undertaken. Gowning and removal of make-up and jewellery (or taping of rings) will be carried out. The woman is visited by the anaesthetist preoperatively, and assessed.

Results of any blood tests that have been requested are obtained and a full blood count is carried out. Blood is grouped and saved. In the case of pre-eclampsia, urea and electrolyte levels will be examined and clotting factors assessed. The woman will have fasted and have taken the prescribed antacid therapy. Attitudes and practices vary regarding pubic shaving.

The woman may prefer to be catheterized in the theatre under epidural, spinal or general anaesthetic, but it may be more private to do this in her room, before entering the operating theatre where others are present.

Caesarean section – some statistics

Internationally, the caesarean section rate is on the increase, with the exception of Norway and Sweden (Chaffer & Royle 2000). The northern European countries have not only the lowest caesarean section rates, but also the lowest perinatal mortality rates.

The results of the National Sentinel Caesarean Section Audit (RCOG 2001) show that caesarean section rates in 2000 were highest in Wales, at 24.2% in 2000 and in Northern Ireland, at 23.9% in 2000–2001. Fear of litigation is thought to be a major contributing factor, but in Canada, where litigation is not widespread, the rates are still rising.

The drive to lower caesarean section rates is economic, but other vital perspectives must be appraised. Chaffer & Royle (2000) state that, by reducing the caesarean section rate by 5%, two to seven maternal deaths could be prevented annually in Britain. The seventh report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the UK (Lewis 2007) states that routine use of thromboprophylaxis and antibiotics has reduced deaths from pulmonary embolism and sepsis. However, the report also states that caesarean section is not a risk-free procedure especially in women who are obese.

Women’s request for caesarean section

The reasons behind the ‘demand’ for caesarean section are complex and involved. Accounts of women who have had difficult experiences of childbirth describe knowing something was wrong, and believing they were not listened to. They then go on to request caesarean section for a subsequent birth. Demands therefore stem from previous bad experiences, expressed even as ‘nightmare’ by some women. There is much evidence to support the fact that very few women actually request caesarean section in the absence of medical indications (Chaffer & Royle 2000, Weaver et al 2001).

Maternal age and caesarean section

There is literature to show that more research is required on obstetrical practices and complications that occur in older women who have had caesarean section, to understand the relationship between these two. It is true that interventions are a consequence of complications (Bell et al 2001), but complications may also result from intervention. The variation in rates of caesarean section between obstetricians and how maternal age affects these requires more consideration.

Other reports show that caesarean section rates rise from teenage years onwards (Marwick & Lynn 2001). These writers state that as findings were particularly uniform, and this from very diverse countries, clinical practice and societal pressures were unlikely to be the cause of the increase in intervention with the increase in maternal age. One paper states that ‘concern about complications might be as much of a problem as the complications themselves’ (Weaver et al 2001, p 285). The midwife should understand the fears of the childbearing woman, and provide information and support appropriately to disperse these.

Psychological support and the role of the midwife

Choice is an important element in this sequence. One writer makes recommendations following a study on the rise of caesarean section rates, in the attempt to decipher the various reasons why there is such a variation in practice (Chaffer & Royle 2000). Five of the 11 propositions for practice relate to information giving, involvement of the woman in the decision-making process and the provision of consistent advice.

Women expect to be actively involved in their care and the midwife must ensure that recent, valid and relevant information is provided in a straightforward manner for women. This will help women to decide what is best for them, in their circumstances. An informed, confident and competent practitioner will relieve the stress of the situation and help the woman make a decision, supporting her in the midst of her misgivings. The midwife has a pivotal role in giving women clear and unbiased information concerning the choices available (McAleese 2000).

One-to-one care from a support person during labour can influence caesarean section rates (Walker & Golois 2001). It is important that midwives recognize that this is a positive tactic and should value their role and skills. A continual, supportive presence in labour is widely reported as being of considerable benefit. Churchill (1997) states that a friend or partner is appreciated because they are able to act as a mediator on behalf of the woman. They are also able to describe the occurrences and happenings during the operation (Box 32.1, Wendy and Martin’s story).

Box 32.1 Wendy and Martin’s story

When we came in to have our first baby, we didn’t know what to expect (although we had been given lots of information). When you do it for real it’s just so different. Things went very quickly. I was quite worried having my epidural. The doctor seemed to take a long time and it was a bit uncomfortable. We got the impression that people thought he was struggling a bit, which doesn’t fill you with confidence. Then when they first cut me, I could feel it a bit and got really anxious. Having my husband there all the time helped, and he said a senior doctor was there by then, and he gave me some extra medicine and massaged my head and that was it, I felt much better! We had brought a CD as they said, but we were a bit disappointed that the player was tiny and right down the other end of the room away from my head so that we couldn’t hear it. We’d made a special CD, and I had been playing it every night to my baby, so we were used to the sound. Oh well. During the operation we were stuck under a sort of tent, so we couldn’t see what was going on. My husband had to really strain to see our baby coming out of me, and no-one asked us if he wanted to cut the cord or anything. But we did feel that everyone was kind to us and looked after us very well. We knew the operation wasn’t easy and had taken longer than they thought. We were just so glad that everything went alright in the end, and we have a beautiful healthy son to look after (Fig. 32.8).

Clarifying the indications for caesarean section

In an effort to try to clarify the precise motive behind women’s request for caesarean section, the National Sentinel Caesarean Section Audit (RCOG 2001) formulated the following objectives:

The aim of the study was to ascertain the contribution of maternal requests to caesarean section rates and also to interpret the variation of caesarean section rates. There is evidence to support the notion that caesarean section is being used too liberally (Dimond 1999). Many authors state that the number of women who request caesarean section purely for convenience is low (Page 1999, Weaver et al 2001). The same writers observe that, although women are not aware of the morbidity for mother and the baby, they are generally well informed as to the incapacitating consequences of major surgery.

Not all caesarean sections that are non-elective are of an emergency nature. A caesarean section, for example carried out after a few hours of labour when the CTG shows that there may be a degree of fetal compromise present, may be carried out urgently. This will not be an emergency in the strict sense of the word.

Elective caesarean section

This indicates that the decision to carry out the procedure has been taken during the pregnancy, therefore before labour has commenced. If the indication for caesarean section has been a non-recurring one, for example placenta praevia, vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC) may be attempted. Repeat caesarean section may be indicated in, for example, cephalopelvic disproportion, or on a uterus that has been scarred twice.

Within the umbrella of ‘elective’ caesarean, there could be merit in re-classification. For example, there are those operations that are truly ‘elective’ in that they are booked around term at a time convenient for mother and surgeon. The other category includes ‘scheduled’ caesarean sections when it becomes clear that early delivery is required, but there is no immediate compromise to mother or fetus.

Emergency caesarean section

This is carried out when adverse conditions develop during pregnancy or labour. Standards have been suggested for the maximum time that should elapse from the decision to deliver to the actual time the baby is born. However, this is less straightforward, as in some cases there is a real ‘emergency’ and everything needs to be in place for immediate delivery of the baby if it is to survive (e.g. cord prolapse with fetal compromise). Then there are other situations where delivery is ‘urgent’ but more time can be taken to prepare for the operation and proposed actions can be discussed with the parents in a more relaxed manner.

The following are examples of urgent/emergency reasons for caesarean birth:

Vaginal birth after caesarean section

Ziadeh & Sunna (1995) state that widespread adoption of a policy whereby 80% of women with prior caesarean section have a trial of labour could potentially eliminate up to one-third of caesarean sections. Reports state less than a 1% frequency of uterine rupture and no maternal deaths from this cause.

Trial of labour

A trial of labour is carried out whenever there is doubt about the outcome of the labour because of a previous caesarean section. Criteria include:

Coltart et al (1990) claim that women admitted in active labour have higher vaginal birth rates following caesarean section than those admitted in early labour. Birth weight in previous pregnancies should not exert undue influence on management procedures. Peterson & Saunders (1991) suggest that units allowing longer labours had higher vaginal birth rates following caesarean section. Time limits on the duration of these labours are neither helpful nor reassuring for the woman.

Pare et al (2006) point out that recent arguments about the safety of VBAC have ignored potential downstream consequences of a strategy of multiple elective repeat caesarean sections. These are increased hospital stay, greater risk of placenta praevia and placenta accreta in future pregnancies. They confirmed that for a woman who desires two or more additional children, the risks of multiple caesarean section outweigh the immediate risks of a VBAC attempt. Therefore, for a woman who desires two or more additional children, a VBAC attempt decreases the total number of hysterectomies performed. The decision to carry out an elective caesarean section is complex and the whole clinical picture must be taken into account.

General anaesthesia

Despite the increasing use of regional anaesthesia, general anaesthesia is sometimes required. Regional anaesthesia is incompatible with any maternal coagulation disorder. General anaesthesia can be more rapidly administered, and is of value when speed is important, such as when the fetus is in serious jeopardy (Enkin et al 2000). Women are preoxygenated prior to induction of anaesthesia; that is, they are given oxygen-rich gas mixtures to breathe for several minutes. A muscle relaxant (suxamethonium) is given to allow safe orotracheal intubation; a cuffed tube and cricoid pressure are essential to prevent aspiration of stomach contents. Induction agents include thiopental and propofol. Maternal unconsciousness ensues within seconds. There are minimal side-effects and relatively little negative fetal consequences at the time of birth provided meticulous practices are in place. Regional anaesthesia, however, normally remains the safer option for caesarean birth. Anaesthesia is sustained by inhalational anaesthetic means using Fluothane or Ethrane.

A total of 25 ‘anaesthetic incidents’ were reported in 1998 (CESDI 2000). These fell into three categories, involving:

When the midwife recognizes an abnormality she must report it to the appropriate person, giving adequate details, as it is obvious that efficiency and clarity will prevent major incidents from occurring. Speed is essential and the midwife can assist by making sure that optimal care is given and by being an advocate for the mother.

Mendelson’s syndrome

This condition was described by Mendelson in 1946 (Stables & Rankin 2005). It is caused if acid gastric contents are inhaled and result in a chemical pneumonitis. This regurgitation may occur during the induction of a general anaesthetic and go unheeded. The acidic gastric contents then damage the alveoli, impairing gaseous exchange. It may become impossible to oxygenate the woman and death may result. The predisposing factors are: the pressure from the gravid uterus when the woman is lying down, the effect of the progesterone relaxing smooth muscle, and the cardiac sphincter of the stomach possibly being relaxed by the effect of the anaesthetic. Analgesics such as pethidine cause significant delay in gastric emptying, thereby exacerbating the above.

Prevention of Mendelson’s syndrome

Antacid therapy. Although there are now relatively few cases where general anaesthesia is used for caesarean section, the prevention of Mendelson’s syndrome is essential. Prophylactic treatment is given to all women in whom a caesarean is planned or anticipated. A usual regimen is for women having an elective operation to be given two doses of oral ranitidine 150 mg approximately 8 hrs apart, plus 30 mL sodium citrate immediately before transfer to theatre. Women in labour who are thought to have a high risk of caesarean section should have ranitidine 150 mg every 8 hrs. These drugs inhibit the secretion of hydrochloric acid in the stomach.

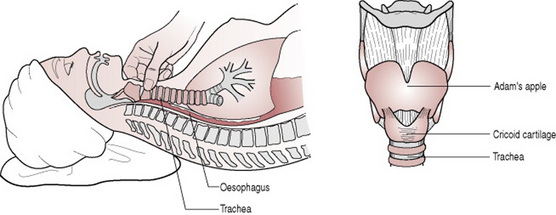

Cricoid pressure. This is the most important measure in preventing pulmonary aspiration (Enkin et al 2000). The oesophagus is occluded by the use of cricoid pressure. Cricoid pressure is a technique whereby the pressure exerted on the one whole ring of tracheal cartilage, the cricoid cartilage, thus occludes the oesophagus and prevents reflux. Cricoid pressure is maintained by an assistant until the tracheal tube is positioned by the anaesthetist, and the seal of the cuff is verified. The correct use of this manoeuvre is essential in preventing major incidents from occurring (Fig. 32.8).

Difficult or failed intubation

This condition is more likely to occur in pregnant women and particularly with those who have pregnancy-induced hypertension. Laryngeal oedema arises more frequently in these women, therefore anticipation of the disorder is key to its management. If laryngeal oedema is anticipated, a very experienced and well-briefed anaesthetist should carry out the intubation. A well-lubricated stylet or bougee may be used to aid endotracheal intubation. Management of failed intubation is: continued cricoid pressure (but not at the expense of oxygenation) and ventilation by face mask until the effects of suxamethonium and thiopental have worn off (and the woman has regained consciousness and her cough reflex).

Complications

It is suggested that, with the increase in caesarean section rates, there is likely to be a subsequent rise in maternal mortality (Chaffer & Royle 2000, Dimond 1999, Hillan 1995). Morbidity reports reveal that only 9.5% of a sample of women delivered by caesarean section (n = 619) had no reported morbidity in the postnatal period (Magill-Cuerden 1996). The evidence suggests that there is also a wide variation in reported morbidity and scanty research on this. Although surgical and anaesthetic techniques have improved, women are still more liable to suffer from complications and to have increased morbidity following caesarean section.

Infection

Maternal morbidity following caesarean section has not been studied methodically, but the problem of postoperative infection is considerable (Enkin et al 2000). In one study that considered wound infection (Chaffer & Royle 2000), this was confirmed as being as high as 34%. In the same study, the wound infection rate was even greater, when data covering the first 6 weeks following caesarean section were included. There is now persuasive evidence to indicate that antibiotic prophylaxis markedly reduces the risk of serious postoperative infection such as pelvic abscess, septic shock and septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis. There is similar evidence to support the fact that women are also safeguarded against endometritis. Protection against wound infection is less sure, but remains considerable (Enkin et al 2000).

Infection is associated with previous rupture of membranes and other factors such as obesity. The prophylactic use of antibiotics was recommended in the 1998 CEMD report (DH 1998) and there is clear evidence showing its benefits, from controlled trials. There is a much greater incidence of infection following emergency caesarean section (Enkin et al 2000, Hillan 1995). The length of stay in hospital prior to operation also influences this incidence. Delaying shaving of the operation site until immediately before operating, ensuring sterilization of all swabs and instruments and a general good sterile and surgical technique would all contribute to a reduction in infection postoperatively.

Urinary tract infection. This was the most consistent of the infectious morbidity described by Hillan’s (1995) comprehensive and informative investigation into postoperative morbidity following caesarean section. Urinary tract infection was present in 10.9% of women who had elective and 10.3% of women who had emergency caesarean section. Wound infection rose from 4.1 to 8.3%, intrauterine infection from 1.4 to 6% and chest infection from 0.9 to 5.3%, respectively in elective and emergency caesarean section. Hence the need for attentive and careful observation and care by the midwife of women who have had an emergency caesarean section.

Thromboembolic disorders

These remain the leading direct cause of maternal death, accounting for 41 of the total 132 direct maternal deaths (Lewis 2007). Although there was a small reduction in deaths after caesarean section, further improvements are necessary. Pregnancy and surgery carry increased risks of thromboembolus and the timing of and dose according to body weight of thromboembolic prophylaxis are crucial.

Postoperative care

Immediate care

Observations

The blood pressure, respirations and pulse should be recorded every 15 min in the immediate recovery period. The temperature should be recorded every 2 hrs. The wound must be inspected every 30 min to detect any blood loss. The lochia should also be inspected and drainage should be small initially. Following general anaesthesia the woman is nursed in the left lateral or ‘recovery’ position until she is fully conscious, since the risks of airway obstruction or regurgitation and silent aspiration of stomach contents are still present.

Analgesia

This is prescribed and is given as required. If the mother intends to breastfeed, the baby should be put to the breast as soon as possible. This can usually be achieved with minimal disturbance to the mother. Postoperative analgesia may be given in a variety of ways:

Antiemetics (e.g. cyclizine; prochlorperazine) are usually prescribed by the anaesthetist.

Care following regional block

Following epidural or spinal anaesthesia, the woman may sit up as soon as she wishes, provided her blood pressure is not low. All observations are recorded as described above. Fluids are introduced gradually, followed by a light diet. The intravenous infusion remains in progress for about 12 hrs. Care must be taken to avoid any damage to the legs, which will gradually regain sensation and movement.

As it is possible that an opiate administered via the epidural route may cause some respiratory depression, the woman’s respiratory rate must be recorded. This means of pain relief offers the advantage of excellent analgesia without motor block and also seems to give a feeling of well-being. Women are usually able to become mobile very quickly, which reduces the risk of deep venous thrombosis. It is also more conducive to the woman’s psychological health.

Ideally, the baby should remain with his mother and they should be transferred to the postnatal ward together once the recovery team says it is safe to do so.

Care in the postnatal ward

On the ward, the blood pressure, temperature respirations and pulse are usually checked every 4 hrs. The intravenous infusion will continue, and the urinary catheter may remain in the bladder until the woman is able to get up to the toilet. The wound and lochia must initially be observed at least hourly. The baby should remain with his mother, and the midwife should offer extra help to ensure that the mother has adequate rest. The mother is encouraged to move her legs and to perform leg and breathing exercises. The physiotherapist will usually teach these and may give chest physiotherapy. Prophylactic low dose heparin and TED antiembolism stockings are often prescribed. The woman is helped to get out of bed as soon as possible following caesarean section, and is encouraged to become fully mobile.

Urinary output must be monitored carefully both before and after removal of the urinary catheter; women may have some difficulty with micturition initially and the bladder may be incompletely emptied. Any haematuria must be reported to the doctor.

Women who have had a general anaesthetic for caesarean section may feel very tired and drowsy for some hours. A woman may complain of a feeling of detachment and unreality and may feel that she does not relate well to the baby. The woman who is concerned should be reassured and be given the opportunity to talk freely.

The mother must be encouraged to rest as much as possible and tactful advice may need to be given to her visitors. If the mother becomes too tired, help is needed with care for the baby. This should preferably take place at the mother’s bedside and should include support with breastfeeding. The clip-on cots, which may be attached to the mother’s bed can facilitate the handling of baby for the mother (Fig. 32.9).

Some women may have a lingering feeling of failure or disappointment at having had a caesarean section and may value the opportunity to talk this over with the midwife.

Research and the incidence of caesarean section: tackling high and rising caesarean section rates

Low caesarean section rates are associated with low levels of intervention and high levels of psychological support. It is difficult to decipher whether caesarean section rates have been affected by interventions, such as proactive management of labour – that is, artificial rupture of membranes and use of oxytocin – or whether other factors have influenced these. As the protocol of O’Driscoll et al (1993) requires a continuous and supportive presence during labour, this may also have influenced the outcome of the labour and birth; this trial shows an impressive 5% caesarean section rate in Dublin. Other researchers have attempted to interpret these results. Lopez-Zeno et al (1992) did find a significant difference in caesarean section rates between women who were actively managed and those who were not; the actively managed group had much lower caesarean section rates.

The NICE Guidelines (2004) say that the clinical interventions to reduce caesarean section include:

While there is no accepted optimal rate for caesarean section in the UK, some tertiary units keep their caesarean section rate below 20%. If reductions in the rate are to be achieved, efforts should focus on where there is most potential for reduction: reducing primary caesarean section, particularly in first-time mothers, and increasing rates of VBAC. ECV should be offered to all women with an uncomplicated breech pregnancy at term and vaginal breech birth should be an option for women (MCWP 2006, p 10).

AAFP (American Academy of Family Physicians). Advanced life support in obstetrics (ALSO), 4th edn. Leawood: AAFP, 2000.

Anim-Somuah M, Smyth R, Howell C. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labour. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007;Issue 2:CD00031.

Bell J S, Campbell D M, Graham W J, et al. Do obstetric complications explain high caesarean section among women over 30? British Medical Journal. 2001;322:894-895.

CESDI (Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy). Seventh annual report, 1 January31 December 1998. London: Maternal and Child Health Research Consortium, 2000;p 1-113.

Chaffer D, Royle L. The use of audit to explain the rise in caesarean section. British Journal of Midwifery. 2000;8(11):677-684.

Charles C. How it feels to be a midwife practitioner. British Journal of Midwifery. 1999;7(6):380-382.

Churchill H. Caesarean birth experience, practice and history. Hale: Books for Midwives Press, 1997.

Coltart T, Davies J, Katesmark M. Outcome of second pregnancy after a previous caesarean section. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1990;97:1140-1143.

DH (Department of Health). Statistical Bulletin. Maternity Statistics England 2002–2003. London: HMSO, 2004.

DH (Department of Health), Welsh Office, Scottish Office Department of Health, Department of Health and Social Services Northern Ireland. Why Mothers Die. Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom1994–1996. London: Stationery Office, 1998.

Dimond B. Is there a legal right to choose a caesarean. British Journal of Midwifery. 1999;7(8):515-518.

Drife J. Choice and instrumental delivery. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1996;103:608-611.

Enkin M, Keirse M, Neilson J, et al. A guide to effective care in pregnancy and childbirth, 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Evans W, Edelstone D I. Kean L, Baker P, Edelstone D I, editors. 2000 Best practice in labour ward management. London: W B Saunders, 2000.

Hillan E M. Postoperative morbidity following caesarean delivery. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1995;22:1035-1042.

Johanson R B, Menon V J. Vacuum extraction versus forceps for assisted vaginal delivery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1999;Issue 2:CD000224.

Johanson R B, Rice C, Doyle M, et al. A randomised prospective study comparing vacuum extractor policy with forceps delivery. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1995;100:524-530.

Lewis G, editor. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer 2003–2005. The seventh report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. CEMACH, London, 2007.

Lopez-Zeno J A, Peaceman A M, Adashek J A, et al. A controlled trial of a program for the active management of labour. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326(17):450-454.

McAleese S. Caesarean section for maternal choice? Midwifery Matters. 2000;84:1-7.

Magill-Cuerden J. Intervention in a natural process. Modern Midwife May. 4, 1996.

Marwick J C, Lynn R. High caesarean rates among women over 30. British Medical Journal. 2001;323:284.

MCWP (Maternity Care Working Party). Modernising maternity care A Commissioning Toolkit for England, 2nd edn. London: The National Childbirth Trust, The Royal College of Midwives, The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2006.

Miller A W F, Hanretty K P. Obstetrics illustrated, 5th edn. London: Churchill Livingstone, 1997.

Mulholland L. Midwife ventouse practitioners. British Journal of Midwifery. 1997;5(5):255.

NICE (National Centre for Clinical Excellence) National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Caesarean section: clinical guideline. London: RCOG Press, 2004.

O’Driscoll K, Meagher D, Boylan P. Active management of labour, 3rd edn. London: Mosby, 1993.

Page L. Caesarean birth: the kindest cut? British Journal of Midwifery. 1999;7(5):296.

Pare E, Quinones J, Macones G. Vaginal birth after caesarean section versus elective repeat caesarean section: assessment of maternal downstream health outcomes. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;113:75-85.

Peterson C M, Saunders N J. Mode of delivery after one caesarean section: audit of current practice in a health region. British Medical Journal. 1991;303(6806):818-821.

RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists). Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit. The national sentinel caesarean section audit report. London: RCOG, 2001.

Stables D, Rankin J. Physiology in childbearing with anatomy and related biosciences, 2nd edn. London: Elsevier, 2005.

Stephenson P A. International differences in the use of obstetrical inventions. Copenhagen: WHO, 1992;112.

Walker R, Golois E. Why choose caesarean section? Lancet. 2001;357:636-637.

Weaver J, Stratham H, Richards M. High rates may be due to perceived potential for complications. British Medical Journal. 2001;323:284-285.

Ziadeh S M, Sunna E I. Decreased cesarean birth rates and improved perinatal outcome: a seven year study. Birth. 1995;22(3):144-147.

Francome C, Savage W, Churchill H, et al. Caesarean birth in Britain. London: Middlesex University Press, 1993.

A book for health professionals and parents, this presents an international and an historical narration of issues such as causes of, coping with, and policies of British consultants in relation to, caesarean section. Vaginal birth after caesarean section is reviewed.

Kean L, Baker P, Edelstone D. Best practice in labour ward management, 1st ed. London: W B Saunders, 2000.

This book, written by three obstetricians, is a very useful handbook for students of midwifery and midwives alike. The perspective is research-based and very woman-centred. It contains useful references at the end of each chapter. The whole is focused on care of women on the labour ward, therefore the chapter on Instrumental Delivery and Caesarean Section provides interesting backgrounds on these areas of practice.