Chapter 28 The transition and the second stage of labour

physiology and the role of the midwife

When labour moves to the phase of active maternal pushing, the whole tempo of activity changes. The change in nature of uterine activity can lead women to express confusion and loss of control. Intense physical effort and exertion is needed as the baby is finally pushed towards its birth. The mother, her supporting companions, and her midwife all require stamina and courage. Excitement and expectation mount as the birth becomes imminent. A positive outcome will depend upon mutual respect and trust between all involved professional groups, and between those groups and the labouring mother and her companions. A mother will never forget a midwife who positively supports her capacity to give birth to her baby. The nature of normality in labour has been subject of debate for a number of years (Anderson 2003, Crawford 1983, Downe 1994, 2004, 2006, 2008, Gould 2000, Montgomery 1958) (See Box 28.1).

The nature of the transition and second stage phases of labour

The second stage of labour has traditionally been regarded as the phase between full dilatation of the cervical os, and the birth of the baby. However, most midwives and labouring women are aware of a transitional period between the period of cervical dilatation, and the time when active maternal pushing efforts begin. This is typically characterized by maternal restlessness, discomfort, desire for pain relief, a sense that the process is never-ending, and demands to attendants to end the whole process. Appropriate midwifery care encompasses both knowledge of the usual physiological processes of this phase and of the mechanism of birth, and insight into the needs and choices of each individual labouring woman.

The physiological changes are a continuation of the same forces which occurred in the earlier hours of labour, but activity is accelerated. This acceleration, however, does not occur abruptly. Some women may experience an urge to push before the cervical os is fully dilated, and others may experience a lull before the onset of strong expulsive second stage contractions. This latter phenomenon has been termed the resting phase of the second stage of labour. The formal onset of the second stage of labour is traditionally confirmed with a vaginal examination to check for full dilatation of the cervical os. However, a finding of full cervical dilatation may occur some time after this stage has in fact been reached.

Uterine action

Contractions become stronger and longer but may be less frequent, allowing both mother and fetus regular recovery periods. The membranes often rupture spontaneously towards the end of the first stage or during transition to the second stage. The consequent drainage of liquor allows the hard, round fetal head to be directly applied to the vaginal tissues. This pressure aids distension. Fetal axis pressure increases flexion of the head, resulting in smaller presenting diameters, more rapid progress and less trauma to both mother and fetus. If the mother is upright during this time, these processes are optimized.

The contractions become expulsive as the fetus descends further into the vagina. Pressure from the presenting part stimulates nerve receptors in the pelvic floor. This phenomenon is termed the ‘Ferguson reflex’. As a consequence, the woman experiences the need to push. This reflex may initially be controlled to a limited extent but becomes increasingly compulsive, overwhelming and involuntary. The mother’s response is to employ her secondary powers of expulsion by contracting her abdominal muscles and diaphragm.

Soft tissue displacement

As the fetal head descends, the soft tissues of the pelvis become displaced. Anteriorly, the bladder is pushed upwards into the abdomen where it is at less risk of injury during fetal descent. This results in the stretching and thinning of the urethra so that its lumen is reduced. Posteriorly, the rectum becomes flattened into the sacral curve and the pressure of the advancing head expels any residual faecal matter. The levator ani muscles dilate, thin out and are displaced laterally, and the perineal body is flattened, stretched and thinned. The fetal head becomes visible at the vulva, advancing with each contraction and receding between contractions until crowning takes place. The head is then born. The shoulders and body follow with the next contraction, accompanied by a gush of amniotic fluid and sometimes of blood. The second stage culminates in the birth of the baby.

Recognition of the commencement of the second stage of labour

Progress from the first to the second stage is not always clinically apparent.

Presumptive evidence

Expulsive uterine contractions

Some women feel a strong desire to push before full dilatation occurs. Traditionally, it has been assumed that an early urge to push will lead to maternal exhaustion and/or cervical oedema or trauma. More recent research indicates that the early pushing urge may in fact be experienced by a significant minority of women, and that, in certain circumstances, early pushing may be physiological (Downe et al 2008, Petersen & Besuner 1997, Roberts & Hanson 2007). It is not clear whether these findings are influenced by factors such as maternal or fetal position, or parity, and there is not enough evidence to date to determine the optimum response to the early pushing urge. The midwife needs to work with each individual woman in the context of each labour to determine the best approach in that specific case.

Dilatation and gaping of the anus

Deep engagement of the presenting part may produce this sign during the latter part of the first stage.

Anal cleft line

Some midwives have reported observing this line (also called ‘the purple line’) as a pigmented mark in the cleft of the buttocks which creeps up the anal cleft as the labour progresses (Hobbs 1998, Wickham 2007). The efficacy of this observation remains to be tested formally.

Appearance of the rhomboid of Michaelis

This is sometimes noted when a woman is in a position where her back is visible. It presents as a dome shaped curve in the lower back, and is held to indicate the posterior displacement of the sacrum and coccyx as the fetal occiput moves into the maternal sacral curve (Sutton & Scott 1996). This seems to lead the labouring woman to arch her back, push her buttocks forward, and throw her arms back to grasp any fixed object she can find. Sutton and Scott (1996) hypothesize that this is a physiological response, since it causes a lengthening and straightening of the Curve of Carus, optimizing the fetal passage through the birth canal.

Upper abdominal pressure and epidural analgesia

It has been observed anecdotally that women who have an epidural in situ often have a sense of discomfort under the ribs towards the end of the first stage of labour. This seems to coincide with full cervical dilatation. The efficacy of these observations in predicting the onset of the anatomical second stage of labour remains to be researched.

Show

This is the loss of bloodstained mucus which often accompanies rapid dilatation of the cervical os towards the end of the first stage of labour. It must be distinguished from frank fresh blood loss caused by partial separation of the placenta or a ruptured vasa praevia.

Appearance of the presenting part

Excessive moulding may result in the formation of a large caput succedaneum which can protrude through the cervix prior to full dilatation of the os. Very occasionally, a baby presenting by the vertex may be visible at the perineum at the same time as remaining cervix. This is more common in women of high parity. Similarly a breech presentation may be visible when the cervical os is only 7–8 cm dilated.

Confirmatory evidence

In many midwifery settings, it is held that a vaginal examination must be undertaken to confirm full dilatation of the cervical os. This is both to ensure that a woman is not pushing too early, and to provide a baseline for timing the length of the second stage of labour. However, some maternity settings and some individual midwives do not insist on this unless there are observable maternal and/or fetal signs that the labour is not progressing as anticipated. Enkin et al (2000, p 284) noted that vaginal assessment of cervical dilatation is largely unevaluated. Despite this, regular vaginal examinations are undertaken by most midwives and obstetricians, and expected by many women. Whether the midwife undertakes an examination or not, she should record all the signs she observes and all the measurements she takes, and she should advise and support the labouring woman on the basis of accurate observation and assessment of progress.

Two distinct phases in second stage progress have been recognized in some women. These are the latent phase during which descent and rotation occur, and the active phase with descent and the urge to push.

Phases and duration

The latent phase

In some women, full dilatation of the cervical os is recorded, but the presenting part may not yet have reached the pelvic outlet. She may not experience a strong expulsive urge until the head has descended sufficiently to exert pressure on the rectum and perineal tissues. There is evidence from a study undertaken half a century ago that active pushing during the latent phase does not achieve much, apart from exhausting and discouraging the mother (Benyon 1990). More recent concerns over the impact of epidural analgesia on spontaneous birth have led to an increasing interest in the passive second stage of labour (Simpson & James 2005, NICE 2007). Due to the effect of epidural analgesia on the pelvic floor muscles, there is little benefit in encouraging active pushing until the head has descended and rotated as far as possible if a woman has an effective epidural in situ. Passive descent of the fetus can continue with good midwifery support for the woman until the head is visible at the vulva, or until the mother feels a spontaneous desire to push.

Active phase

Once the fetal head is visible, the woman will usually experience a compulsive urge to push.

Duration of the second stage

There is no good evidence about the absolute time limits of physiological labour (Downe 2004). Mothers and babies who labour for at least twice as long as the traditional limits can do well (Albers 1999). In the presence of regular contractions, maternal and fetal well-being, and progressive descent, considerable variation between women is to be expected. While many maternity units do currently impose limits on the second stage beyond which medical help should be called, these are not based on good evidence (Enkin et al 2000, p 293).

Maternal response to transition and the second stage

Pushing

Traditionally, if the maternal urge to push occurs before confirmation of full dilatation of the cervical os, or the appearance of a visible vertex, the mother is encouraged to avoid active pushing at this stage. This is done to conserve maternal effort and allow the vaginal tissues to stretch passively. Techniques include position change, often to the left lateral, using controlled breathing, inhalation analgesia, or even narcotic or epidural pain relief (Downe et al 2008). However, when mother and baby are well and labour has progressed spontaneously, some midwives have adopted the practice of supporting the overwhelming urge to bear down without confirming full dilatation of the cervical os, while paying close attention to the maternal and fetal condition. As stated above, the optimum response in this situation has not yet been established.

There has been convincing evidence for over a decade that managed active pushing in the second stage of labour accompanied by breath holding (the Valsalva manoeuvre) has adverse consequences (Aldrich et al 1995, Enkin et al 2000 p 290-1, Thomson 1993). Whenever active pushing commences, the woman should be encouraged to follow her own inclinations in relation to expulsive effort. Few women need instruction on how to push unless they are using epidural analgesia (Box 28.2).

Box 28.2 Epidural analgesia and spontaneous vaginal birth

Epidural analgesia provides optimal pain relief for women, but its use is associated with an increase in instrumental births (Anim-Somuah et al 2005).

Techniques for reducing the risk of instrumental births in this group have included:

Spontaneous pushing efforts usually result in maximum pressure being exerted at the height of a contraction. In turn, this allows the vaginal muscles to become taut and prevents bladder supports and the transverse cervical ligaments from being pushed down in front of the baby’s head. It is believed that this may help to prevent prolapse and urinary incontinence in later life, although this belief has still not been formally tested (Benyon 1990).

Some mothers vocalize loudly as they push. This may aid in coping with the contractions, so women should feel free to express themselves in this way. Reassurance and praise will help to boost confidence, enabling the mother to assert her own control over events. The atmosphere should be calm and the pace unhurried.

Position

If the mother lies flat on her back, vena caval compression is increased, resulting in hypotension. This can lead to reduced placental perfusion and diminished fetal oxygenation (Humphrey et al 1974, Kurz et al 1982). The efficiency of uterine contractions may also be reduced. The semi-recumbent or supported sitting position, with the thighs abducted, is the posture most commonly used in western cultures. While this may afford the midwife good access and a clear view of the perineum, the mother’s weight is on her sacrum, which directs the coccyx forwards and reduces the pelvic outlet. In addition, the midwife needs to bend forward and laterally to support the birth, which may lead to injury.

Left lateral position

This position was widely used in the UK in the last century, although it is less common in current practice. The perineum can be clearly viewed and uterine action is effective, but an assistant may be required to support the right thigh, which may not be ergonomic. It provides an alternative for women who find it difficult to abduct their hips. It may also aid fetal rotation, especially in the context of epidural analgesia (Downe et al 2004).

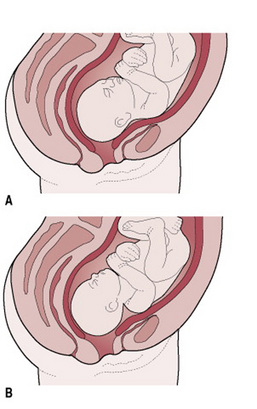

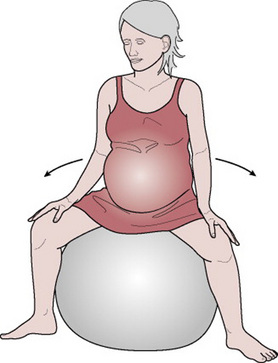

Upright positions; squatting, kneeling, all fours, standing, using a birthing ball. (Figs. 28.1, 28.2)

A review of studies examining upright versus recumbent positions during the second stage of labour showed there were clear advantages for women in adopting an upright position (Gupta et al 2004). These included reduced duration of second stage labour, less assisted deliveries, less episiotomies, reduced severe pain in second stage labour, and fewer abnormal heart rate patterns. However, increased rates of second degree tears and of estimated blood loss >500 mL also occurred. The experimental group included women who used birthing chairs, a technique known to be associated with increased blood loss (Stewart & Spiby 1989, Turner et al 1986). It is not clear if this risk accrues to all upright positions. The ‘upright position’ group in this review included women who were in supported sitting positions on a bed, and in the lateral position. Data relating to off the bed positions is less easy to locate.

Figure 28.1 Supported sitting position.

(After Simkin & Ancheta 2006, with permission from Blackwell Science.)

Figure 28.2 Using a birthing ball.

(After Simkin & Ancheta 2006, with permission from Blackwell Science.)

Radiological evidence demonstrates an average increase of 1 cm in the transverse diameter and 2 cm in the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic outlet when the squatting position is adopted. This produces an average 28% increase in the overall area of the outlet compare with the supine position (Russell 1969). Some women find the all fours position to be the optimum approach for all or part of their labours, especially in the case of an occipitoposterior position, due to relief of backache (Stremler et al 2005). It can, however, be tiring to maintain for a long period of time. A wide range of other standing and leaning positions can be experimented with to help the mother cope with her labour (Simkin & Ancheta 2006). It is important not to insist on any position as the ‘right’ one. Positive and dramatic effects on labour progress can be achieved by encouraging the mother to change and adapt her position in response to the way her body feels.

The position the mother may choose to adopt is dictated by several factors:

Maternal and fetal condition

If the mother has had analgesia, or if there is any concern about the well-being of either the woman or her baby then more frequent or continuous monitoring may limit the choices available to her. However, there are often creative solutions to these situations, and good midwifery care involves finding these solutions where possible.

The mechanism of normal labour

As the fetus descends, soft tissue and bony structures exert pressures which lead to descent through the birth canal by a series of movements. Collectively, these movements are called the mechanism of labour. There is a mechanism for every fetal presentation and position which can lead to a vaginal birth. Knowledge and recognition of the normal mechanism enables the midwife to anticipate the next step in the process of descent. Understanding and constant monitoring of these movements can help to ensure that normal progress is recognized, that the woman gives birth safely and positively, or that early assistance can be sought should any unresolvable problems occur. The fetal presentation, position, and size relative to that of the woman will govern the exact mechanism as the fetus responds to external pressures. Principles common to all mechanisms are:

It should be noted that, while the mechanism set out below is the most common, it is not an invariant blueprint, but a guide: each labour is unique.

During the mechanism of normal labour, the fetus turns slightly to take advantage of the widest available space in each plane of the pelvis. The widest diameter of the pelvic brim is the transverse: at the pelvic outlet the greatest space lies in the anteroposterior diameter.

At the onset of labour, the most common presentation is the vertex and the most common position either left or right occipitoanterior; therefore it is this mechanism which will be described. In this instance:

Main movements of the fetus

Descent

Descent of the fetal head into the pelvis often begins before the onset of labour. For a primigravid woman this usually occurs during the latter weeks of pregnancy. In multigravid women muscle tone is often more lax and therefore descent and engagement of the fetal head may not occur until labour actually begins. Throughout the first stage of labour the contraction and retraction of the uterine muscles allow less room in the uterus, exerting pressure on the fetus to descend further. Following rupture of the forewaters and the exertion of maternal effort, progress speeds up.

Flexion

This increases throughout labour. The fetal spine is attached nearer the posterior part of the skull; pressure exerted down the fetal axis will be more forcibly transmitted to the occiput than the sinciput. The effect is to increase flexion which results in smaller presenting diameters which will negotiate the pelvis more easily. At the onset of labour the suboccipitofrontal diameter, which is on average approximately 10 cm, is presenting; with greater flexion the suboccipitobregmatic diameter, on average approximately 9.5 cm, presents. The occiput becomes the leading part.

Internal rotation of the head

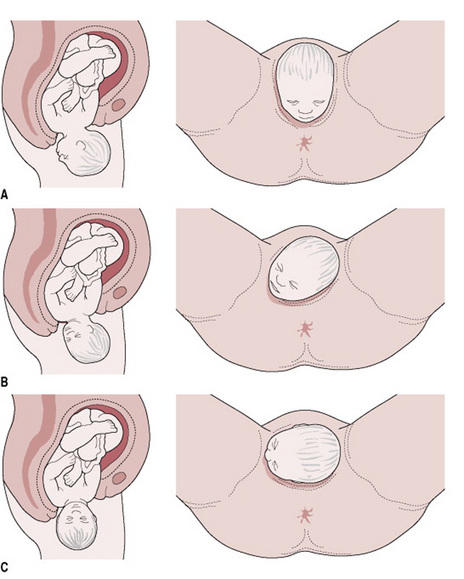

During a contraction, the leading part is pushed downwards onto the pelvic floor. The resistance of this muscular diaphragm brings about rotation. As the contraction fades, the pelvic floor rebounds, causing the occiput to glide forwards. Resistance is therefore an important determinant of rotation (Fig. 28.3). This explains why rotation is often delayed following epidural analgesia which causes relaxation of pelvic floor muscles. The slope of the pelvic floor determines the direction of rotation. The muscles are hammock-shaped and slope down anteriorly, so whichever part of the fetus first meets the lateral half of this slope will be directed forwards and towards the centre. In a well-flexed vertex presentation the occiput leads, and rotates anteriorly through ⅛ of a circle when it meets the pelvic floor. This causes a slight twist in the neck as the head is no longer in direct alignment with the shoulders. The anteroposterior diameter of the head now lies in the widest (anteroposterior) diameter of the pelvic outlet. The occiput slips beneath the sub-pubic arch and crowning occurs when the head no longer recedes between contractions and the widest transverse diameter (biparietal) is born. If flexion is maintained, the sub-occipitobregmatic diameter, usually approximately 9.5 cm, distends the vaginal orifice.

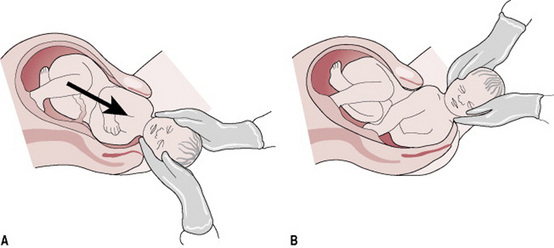

Extension of the head

Once crowning has occurred the fetal head can extend, pivoting on the suboccipital region around the pubic bone. This releases the sinciput, face, and chin, which sweep the perineum, and then are born by a movement of extension (Fig. 28.4).

Restitution

The twist in the neck of the fetus which resulted from internal rotation is now corrected by a slight untwisting movement. The occiput moves ⅛ of a circle towards the side from which it started.

Internal rotation of the shoulders

The shoulders undergo a similar rotation to that of the head to lie in the widest diameter of the pelvic outlet, namely anteroposterior. The anterior shoulder is the first to reach the levator ani muscle and it therefore rotates anteriorly to lie under the symphysis pubis. This movement can be clearly seen as the head turns at the same time (external rotation of the head). It occurs in the same direction as restitution, and the occiput of the fetal head now lies laterally.

Lateral flexion

The shoulders are usually born sequentially. When the mother is in a supported sitting position, the anterior shoulder is usually born first, although it has been noted by midwives who commonly use upright or kneeling positions that the posterior shoulder is commonly seen first. In the former case, the anterior shoulder slips beneath the sub-pubic arch and the posterior shoulder passes over the perineum. In the latter the mechanism is reversed. This enables a smaller diameter to distend the vaginal orifice than if both shoulders were born simultaneously. The remainder of the body is born by lateral flexion as the spine bends sideways through the curved birth canal.

Midwifery care

Care of the parents

The woman and her companions will now realize that the birth of the baby is imminent. They may feel excited and elated but at the same time anxious and frightened by the dramatic change in pace. They will need frequent explanations of events. The midwife’scalm approach and information about what is happening can ensure the woman stays in control, and is confident. This is critical at the time of transition, when events can result in a sensation of panic. The midwife should praise and congratulate the mother on her hard work, recognizing that she is probably undertaking the most extreme physical activity she will ever encounter. Birth is an intimate act which often takes place in a public setting. The midwife should work hard to ensure that privacy and dignity are maintained (Box 28.3).

Crucially, it is at the time of transition that a maternal request for analgesia may occur, even if she had stated antenatally that she did not want pain relief in labour. Such a request will need to be carefully assessed by the attending midwife. This is especially true when a supportive companion is not present. On the basis of her knowledge of the woman, the midwife may be able to help her over this transient phase with good midwifery support, and without utilizing pharmacological analgesia. The decision for or against pain relief at this stage must be made in partnership with the woman. In order to achieve this, it is eminently preferable that the same midwife should support the couple throughout labour (Hodnett et al 2003). Alternatives to pharmacological analgesia include changes in position and scenery, massage and appropriate nutrition. Complementary therapies and optimal fetal positioning may also be offered if the midwife is competent to undertake them. Leg cramp is a common occurrence whichever posture is adopted. It can be relieved by massaging the calf muscle, extending the leg and dorsiflexing the foot. These measures may be crucial in re-energizing a labour which is beginning to flag in the second stage.

The midwife should also have regard to the well-being of the woman’s partner and other companions as far as possible. Witnessing labour and birth is not easy, especially for the woman’s partner. Indeed, recent qualitative research has indicated that birth companions can be profoundly affected by witnessing traumatic birth, and can even exhibit symptoms that appear to be similar to those of post-traumatic stress for years after the birth (White 2007). The midwive’s attitude to the labour, to the woman, and to the partner will have a profound effect on the labour, and is likely to have an effect on the family after the birth (El-Nemer et al 2006, Halldorsdottir & Karlsdottir 1996). It is crucial to respect them, and to respect the meaning that this birth will have for them, both on the day, and in the future.

Observations during the second stage of labour

Four factors determine whether the second stage is continuing safely, and these must be carefully monitored:

Uterine contractions

The strength, length and frequency of contractions should be assessed continuously by observation of maternal responses, and regularly by uterine palpation. They are usually stronger and longer than during the first stage of labour, with a longer resting phase. The posture and position adopted by the mother may influence the contractions.

Descent, rotation and flexion

Initially, descent may occur slowly, especially in primigravid women, but it usually accelerates during the active phase. It may occur very rapidly in multigravid women. If there is a delay in descent on abdominal palpation, despite regular strong contractions and active maternal pushing, a vaginal examination may be performed with maternal permission. The purpose is to confirm whether or not internal rotation of the head has taken place, to assess the station of the presenting part, and to determine whether a caput succedaneum has formed. If the occiput has rotated anteriorly, the head is well flexed and caput succedaneum is not excessive it is likely that progress will continue. In the absence of good rotation and flexion, and/or a weakening of uterine contractions, change of position, nutrition and hydration, or use of optimal fetal positioning techniques may be helpful (Simkin & Ancheta 2006). Consultation with a more experienced midwife may provide more suggestions to re-orientate the labour. However, if there is evidence that either fetal or maternal condition are compromised, an experienced obstetrician should be consulted.

Fetal condition

If the membranes are ruptured, the liquor amnii is observed to ensure that it is clear. While thin old meconium staining is not always regarded as a sign of fetal compromise, thick fresh meconium is always ominous, and experienced obstetric advice must be sought if this sign appears (Enkin et al 2000, p 268-9, Liu & Harrington 2002).

As the fetus descends, fetal oxygenation may be less efficient owing to either cord or head compression or to reduced perfusion at the placental site. A well-grown healthy baby will not be compromised by this transitory hypoxia. This will tend to produce early decelerations of the fetal heart, with a swift return to the normal baseline after a contraction, and good beat-to-beat variation throughout. While early decelerations are always deemed ‘suspicious’ in the current National Institute for Health and Clinical Effectiveness (NICE) guidelines (NICE 2001), in practice their occurrence in the active second stage is not usually regarded as pathological in the absence of any other signs of compromise (see Ch 26). The midwife should learn to recognize the normal changes in fetal heart rate patterns during the second stage, so that unwarranted interference is avoided. If the woman is labouring normally, the guideline recommends that a Pinard’s stethoscope or other hand held system such as a Sonicaid should be used to monitor the fetal heart. During the second stage, this is usually undertaken immediately after a contraction, with some readings being taken through a contraction if the woman can tolerate this.

Suspicious/pathological changes in the fetal heart

Late decelerations, a lack of return to the normal baseline, a rising baseline, or diminishing beat-to-beat variation are signs of concern. If these are heard for the first time in second stage, they may be due to cord or head compression, which may be helped by a change in position. However, if they persist, experienced obstetric aid must be sought. If the labour is taking place in a unit which is distant from an obstetric unit, an episiotomy may be considered if the birth is imminent, or midwives who are trained and experienced in ventouse birth may consider expediting the birth. Otherwise, with maternal consent, transfer to an obstetric unit should be expedited.

Maternal condition

The midwife’s observation includes an appraisal of the mother’s ability to cope emotionally as well as an assessment of her physical well-being. Maternal pulse rate is usually recorded half-hourly and blood pressure every few hours, provided that these remain within normal limits. If the woman has an epidural in situ, blood pressure will be monitored more frequently, and continuous electronic fetal monitoring will probably be in use.

Maternal comfort

As a result of her exertions the woman usually feels very hot and sticky and she will find it soothing to have her face and neck sponged with a cool flannel. Her mouth and lips may become very dry. Sips of iced water or other fluids are refreshing and a moisturizing cream can be applied to her lips. Her partner may help with these tasks as a positive contribution to ease her discomfort.

The bladder is vulnerable to damage, due to compression of the bladder base between the pelvic brim and the fetal head. The risk is increased if the bladder is distended. The woman should be encouraged to pass urine at the beginning of the second stage unless she has recently done so.

Preparation for the birth

Once active pushing commences, the midwife should prepare for the birth. There is usually little urgency if the woman is primigravid, but multigravid women may progress very rapidly.

The room in which the birth is to take place should be warm with a spotlight available so that the perineum can be easily observed if necessary. A clean area should be prepared to receive the baby, and waterproof covers provided to protect the bed and floor. Sterile cord clamps, a clean apron, and sterile gloves are placed to hand. In some settings, sterile gowns are also used. An oxytocic agent may be prepared, either for the active management of the third stage if this is acceptable to the woman, or for use during an emergency. A warm cot and clothes should be prepared for the baby. In hospital a heated mattress may be used; at home, a warm (not hot) water bottle can be placed in the cot.

Neonatal resuscitation equipment must be thoroughly checked and readily accessible.

The birth of the baby

The midwife’s skill and judgement are crucial factors in minimizing maternal trauma and ensuring an optimal birth for both mother and baby. These qualities are refined by experience but certain basic principles should be applied. They are:

During the birth, both mother and baby are particularly vulnerable to infection. While there is now evidence that strict antisepsis is unnecessary if the birth is straightforward (Keane & Thornton 1998), meticulous aseptic technique must be observed when preparing sterile equipment such as episiotomy scissors. Surgical gloves should be worn during the birth for the protection of both mother and midwife. Goggles or plain glasses should be available to avoid the risk of ocular contamination with blood or amniotic fluid.

Once she has scrubbed up the midwife prepares her equipment. This includes the following items:

Birth of the head

Once the birth is imminent, the perineum is usually swabbed, and a clean pad is placed under the woman to absorb any faeces or fluids. If she is not in an upright position a pad is placed over the rectum on the perineum (but not covering the fourchette) and a clean towel is placed on or near the mother for receipt of the baby. Throughout these preparations the midwife observes the progress of the fetus. With each contraction the head descends. As it does so the superficial muscles of the pelvic floor can be seen to stretch, especially the transverse perineal muscles. The head recedes between contractions, which allows these muscles to thin gradually. The skill of the midwife in ensuring that the active phase is unhurried helps to safeguard the perineum from trauma. She must either watch the advance of the fetal head or control it with light support from her hand, or both. One large study, the HOOP trial, indicted that, compared with guarding the perineum, a hands off technique was associated with slightly more maternal discomfort at 10 days postnatally (McCandlish et al 1998). The hands off technique was also associated with a lower risk of episiotomy, but a higher risk of manual removal of placenta. There is some debate about the generalizability of this trial to all settings and positions in labour. However, account should be taken of these findings in working with individual women. Most midwives place their fingers lightly on the advancing head to monitor descent and prevent very rapid crowning and extension, which are believed to result in perineal laceration. However, firm pressure on the head may be associated with vaginal lacerations. Whatever technique the midwife adopts, it should be based on the assumption that it is the woman who is giving birth to her baby, and the midwife is there to add the minimum physical help necessary at any given time.

Once the head has crowned, the mother can achieve control by gently blowing or ‘sighing’ out each breath in order to minimize active pushing. Birth of the head in this way may take two or three contractions but may avoid unnecessary maternal trauma (Fig. 28.5).

Figure 28.5 Supporting the head. (A) Preventing rapid extension. (B) Controlling the crowning. (C) Easing the perineum to release the face.

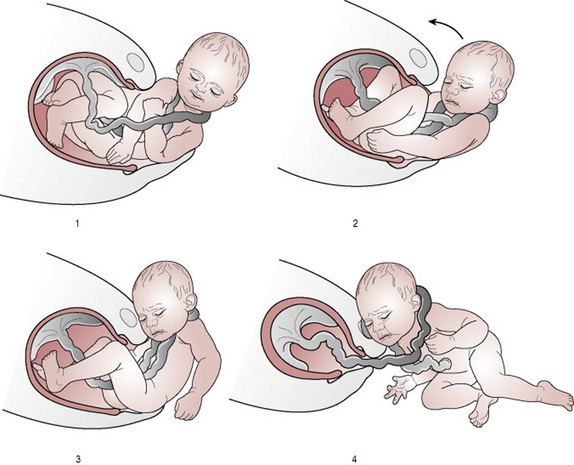

Once crowned, the head is born by extension as the face appears at the perineum. During the resting phase before the next contraction the midwife may check that the cord is not around the baby’s neck. If found, it is usual to slacken it to form a loop through which the shoulders may pass. If the cord is very tightly wound around the neck, it is common practice in the UK to apply two artery forceps approximately 3 cm apart and to sever the cord between the two clamps (Jackson et al 2007). In the USA, the so-called ‘somersault manoeuvre’ is often performed (Fig. 28.6) (Mercer et al 2005, 2007). There has been controversy over early cord cutting for the normal term infant, on the basis that, even if tightly around the neck, the cord is still supplying oxygen. Additionally, the blood volume model proposed by Mercer & Skovgaard (2004) suggests that the loss of blood volume occasioned by clamping and cutting the cord before it stops pulsating may be detrimental to the baby. This hypothesis has been supported by a recent systematic review (Hutton & Hassan 2007). However, these studies have not controlled for the possible adverse effects of a tight nuchal cord.

If the cord is clamped, great care must be taken that maternal tissues are not damaged. Holding a swab over the cord as it is incised will reduce the risk of the attendants being sprayed with blood during the procedure. Once severed, the cord may be unwound from around the neck.

Birth of the shoulders

Restitution and external rotation of the head maximizes the smooth birth of the shoulders and minimizes the risk of perineal laceration. However, it is not uncommon for small babies, or for babies of multiparous women, to be born with the shoulders in the transverse, or even to have a twist in the neck opposite to that expected. While the hands on technique in the HOOP trial included both perineal support and active birth of the trunk and shoulders (McCandlish et al 1998) it is not clear which component of this technique was beneficial for women and babies. If the position is upright, it is more common for the shoulders to be left to birth spontaneously with the help of gravity. During a water birth, it is important not to touch the emerging fetus to avoid stimulating it to gasp underwater. If there is a problem with the birth in this circumstance, the mother should be asked to stand up out of the water before any manoeuvres are attempted.

If the midwife does physically aid the birth of the shoulders and trunk, she should be absolutely sure that restitution has occurred prior to trying to flex the trunk laterally. One shoulder is released at a time to avoid overstretching the perineum. A hand is placed on each side of the baby’s head, over the ears, and gentle downward traction is applied (Fig. 28.7). This allows the anterior shoulder to slip beneath the symphysis pubis while the posterior shoulder remains in the vagina. If the third stage is to be actively managed, the assistant will now give an intramuscular oxytocic drug. When the axillary crease is seen, the head and trunk are guided in an upward curve to allow the posterior shoulder to escape over the perineum. These manoeuvres are reversed if the mother is in a forward facing position such as all fours. The midwife or mother may now grasp the baby around the chest to aid the birth of the trunk and lift the baby towards the mother’s abdomen. This allows the mother immediate sighting of her baby and close skin contact, and removes the baby from the gush of liquor which accompanies release of the body. If the midwife does not actively assist, she should be ready to support the head and trunk as the baby emerges. The time of birth is noted.

Figure 28.7 (A) Downward traction releases the anterior shoulder. (B) An upward curve allows the posterior shoulder to escape.

If this has not already been done, the cord is severed between two cord clamps placed close to the umbilicus at whatever time is considered appropriate, with due attention to the theories around the blood volume model set out above (and see Chs 29 and 39). The cord clamp is applied. The baby is dried and placed in the skin-to-skin position with the mother if she is happy with this (Anderson et al 2003). A warm cover is placed over the baby. Swabbing of the eyes and aspiration of mucus during and immediately following birth are not considered necessary providing the baby’s condition is satisfactory. Oral mucus extractors should not be used because of the risks of mucus which is contaminated with a virus such as hepatitis or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) entering the operator’s mouth.

The moment of birth is both joyous and beautiful. The midwife is privileged to share this unique and intimate experience with the parents.

Episiotomy

As the perineum distends, an episiotomy may very occasionally be necessary. This is an incision through the perineal tissues which is designed to enlarge the vulval outlet during birth. As this is a surgical incision it cannot be undertaken unless the mother gives consent. A detailed discussion should take place during pregnancy so that each woman is aware of the indications for and implications of the intervention. She should be assured that its use is selective and discretional. The mother’s wishes should be clearly documented and respected.

The risks and benefits of episiotomy have been reviewed (Carroli & Belizan 1999). The rationale for its use is the need to minimize the risk of severe trauma to the vagina and perineum, and to expedite the birth when there is evidence of fetal distress. However, the risks of its use should always be borne in mind. During a normal birth the indications are few and the midwife should adopt a restrictive policy.

The timing of the incision

An episiotomy involves incision of the fourchette, the superficial muscles and skin of the perineum and the posterior vaginal wall. It can therefore successfully speed the birth only when the presenting part is directly applied to these tissues. If the episiotomy is performed too early it will fail to release the presenting part and haemorrhage from cut vessels may ensue. In addition, the levator ani muscles will not have had time to be displaced laterally and may be incised as well. If performed too late there will not be enough time to infiltrate with a local anaesthetic. There is also little reason for superimposing an episiotomy if a tear has already begun.

Types of incision

There are two main directions of incision.

Mediolateral

This begins at the midpoint of the fourchette and is directed at a 45° angle to the midline towards a point midway between the ischial tuberosity and the anus. This line avoids the danger of damage to both the anal sphincter and Bartholin’s gland but it is more difficult to repair. This is the incision largely used by midwives in the UK.

Median

This is a midline incision which follows the natural line of insertion of the perineal muscles. It is associated with reduced blood loss but a higher incidence of damage to the anal sphincter. It is the easier to repair and results in less pain and dyspareunia. This incision is favoured in the USA.

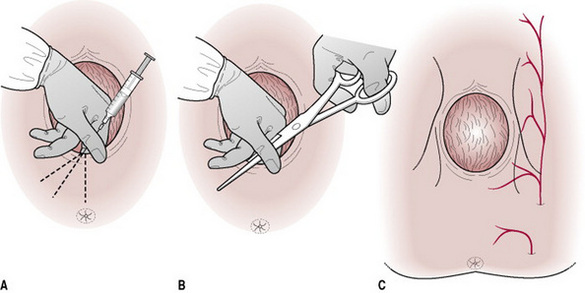

Infiltration of the perineum

The perineum should be adequately anaesthetized prior to the incision. Lidocaine (formerly termed lignocaine) is commonly used, 0.5% 10 mL or 1% 5 mL. The advantage of the more concentrated solution is that a smaller volume is needed. Lidocaine takes 3–4 min to take effect and, if possible, two or three contractions should be allowed to occur between infiltration and incision. The timing is not always easy to calculate but it is better to infiltrate and not perform an episiotomy than to incise the perineum without an effective local anaesthetic.

Method of infiltration

The perineum is cleansed with antiseptic solution. Two fingers are inserted into the vagina along the line of the proposed incision in order to protect the fetal head. The needle is inserted beneath the skin for 4–5 cm following the same line (Fig. 28.8). The piston of the syringe should be withdrawn prior to injection to check whether the needle is in a blood vessel. If blood is aspirated, the needle should be repositioned and the procedure repeated until no blood is withdrawn. Lidocaine is continuously injected as the needle is slowly withdrawn. Some practitioners inject the whole amount in one operation. Anaesthesia is, however, more effective if about one-third of the amount is used at first and two further injections are made, one either side of the incision line. The needle must be redirected just before the tip is withdrawn.

The incision

A straight-bladed, blunt-ended pair of Mayo scissors is usually used. The blades should be sharp. Some practitioners prefer to use a scalpel for this reason. Two fingers are inserted into the vagina as before and the open blades are positioned. The incision is best made during a contraction when the tissues are stretched so that there is a clear view of the area and bleeding is less likely to be severe. A single, deliberate cut 4–5 cm long is made at the correct angle. Birth of the head should follow immediately and its advance must be controlled in order to avoid extension of the episiotomy. If there is any delay before the head emerges, pressure should be applied to the episiotomy site between contractions in order to minimize bleeding. Postpartum haemorrhage can occur from an episiotomy site unless bleeding points are compressed.

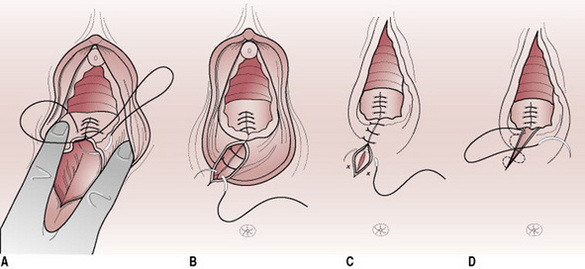

Perineal repair

Trauma is best repaired as soon as possible after the birth in order to secure haemostasis and before oedema forms. It is also much kinder to the mother to complete this aspect of her care without undue delay and while the tissues are still anaesthetized. Prior to commencement the mother must be made as warm and comfortable as possible. The lithotomy position is usually chosen as it affords a clear view. Other positions may be more appropriate in the home setting. A good, directional light is essential and the operator should be seated comfortably during the procedure.

The appropriate instruments, antiseptic solution, suture materials and local anaesthetic, should be prepared before the mother’s legs are placed in the stirrups. This minimizes the time spent in this uncomfortable, undignified position and reduces the risks of complications such as deep vein thrombosis. The midwife scrubs and puts on sterile gown and gloves. The perineum is cleaned with warm antiseptic solution. Blood oozing from the uterus may obscure the field of vision, so a taped vaginal tampon may be inserted into the vault of the vagina. The tape is secured to the drapes by a pair of forceps as a reminder that it is in situ. Both insertion and removal should be recorded. The full extent of the trauma is assessed and explained to the mother. The procedure for repair should also be outlined so that she is aware of what is happening.

Spontaneous trauma may be of the labia anteriorly, the perineum posteriorly or both. A gentle, thorough examination must be carried out to assess the extent of the trauma accurately and to determine whether an experienced obstetrician should carry out the repair, if it is extensive.

Anterior labial tears

It is debatable whether or not these should be sutured. Much depends upon the control of bleeding as the labia are very vascular. A suture may be necessary to secure haemostasis.

Posterior perineal trauma

Spontaneous tears are usually classified in degrees which are related to the anatomical structures which have been traumatized. This classification only serves as a guideline because it is often difficult to identify the structures precisely.

Third- and fourth-degree tears should be repaired by an experienced obstetrician. A general anaesthetic or effective epidural or spinal anaesthetic is necessary.

Prior to the commencement of repair, infiltration of the wound with local anaesthetic will be required. Lidocaine 1% is used and time must be allowed for it to take effect before repair begins. If an epidural block is in progress, a ‘top up’ should be given.

The apex of the vaginal incision is identified and the posterior vaginal wall repaired from the apex downwards (Fig. 28.9). A continuous suture affords better haemostasis (Kettle & Johanson 1998). The thread should not be pulled too tightly as oedema will develop during the first 24–48 hrs. Care must be taken to identify other vaginal lacerations which need to be repaired. Deeper interrupted sutures are then inserted to repair the perineal muscles. Good approximation of tissue is important. The subsequent strength of the pelvic floor will depend largely upon adequate repair of this layer. As long as good approximation is obtained, suturing of the perineal skin is unnecessary, and may lead to increased maternal discomfort (Gordon et al 1998, Oboro et al 2003). If skin closure is carried out, a continuous subcuticular suture (Fig. 28.9) results in fewer short-term problems than interrupted transcutaneous suturing techniques (Kettle & Johanson 1998, RCOG 2004).

Figure 28.9 Perineal repair. (A) A continuous suture is used to repair the vaginal wall. (B) Three or four interrupted sutures repair the fascia and muscle of the perineum. (C) Interrupted sutures to the skin. (D) Subcuticular skin suture.

Absorbable synthetic polyglycolic acid and rapid-absorption polyglactin 910 sutures are recommended (Kettle & Johanson 1999, RCOG 2004). Repair should begin at the fourchette so that the vaginal opening is properly aligned. When the wound has been closed, any further vulval lacerations should be repaired.

The sutured areas should be inspected in order to confirm haemostasis before the vaginal pack is removed. A vaginal examination is made to ensure that the introitus has not been narrowed. Upon completion, and after warning the mother, a rectal examination is made to ensure that no sutures have penetrated the rectal mucosa. Any such sutures must be removed to prevent fistula formation.

The area is cleaned and a sanitary pad positioned over the vulva and perineum. The mother’s legs are then gently and simultaneously removed from lithotomy support and she is made comfortable. The nature of the trauma and repair should be explained to her and information given on whether or not sutures will need to be removed.

Records

It is the responsibility of the midwife assisting the birth to complete the labour record. This should include details of any drugs administered, of the duration and progress of labour, of the reason for performing an episiotomy, and of perineal repair. This information is recorded on the mother’s notes and may be duplicated on her domiciliary record as well as in the birth register. Details of the baby’s condition including Apgar score are also recorded.

The birth notification must be completed within 36 hrs of the birth (see Ch. 56). This may be undertaken by anyone present at the birth but is usually carried out by the midwife. The notification is sent to the medical officer in the health district in which the baby was born.

New developments such as the All Wales Clinical Pathway for Normal Labour (NHS Wales 2006) provide alternative approaches to record-keeping that may be useful for practitioners in the future. However records are kept, all data in the UK are subject to the Data Protection Act 1998.

Conclusion

The processes of transition and of second stage labour are likely to be very physically and emotionally intense, particularly for the woman, but also for her partner and other birth companions. If maternal behaviour and instinct are respected, in the context of skilled and watchful waiting, the vast majority of labours will progress physiologically. The skill of the midwife is to support the woman effectively, to guide her when her spirits or the labour are flagging, and to enable her to accomplish her birth safely and in triumph. See Box 28.4, Diane’s story. Clear, comprehensive record keeping is essential. While much practice in this area is not based on formal evidence, new observations about normal birth are beginning to be recorded, and these observations will form the basis for future research.

The birth of my first baby should have been one of the happiest days of my life. Instead, I felt I had failed; I was mentally and physically traumatized. Five years on, when I was eventually pregnant again, my fears started creeping back, and I considered having a caesarean section. I was referred to the local caseload midwifery team. When my midwife came to visit, I told her that my first birth had left me traumatized, confused, and scared about everything. This was my big turn around: after talking to her I realized I did not want a caesarean section, and I started to feel confident about giving birth naturally.

The big day arrived. I was over the moon that I had started my labour naturally. After a few hours my midwife came to my house, just to check how everything was going. Eventually, we decided it was time to go to the hospital. When I arrived they organized an epidural for me, which I had discussed, and which was in my birth plan. I was getting excited, knowing I was going to meet my baby soon. My midwife supported me and encouraged me on everything I decided. She was there for me all the time, keeping me focused and positive about my birth. After about 3 hrs, I started pushing hard with contractions. The epidural wore off enough for me turn around on to my knees with my body upright, and I could feel the baby drop down. I gave it my all for two pushes, and out popped the head. I controlled my breathing, pushing slowly, and my beautiful baby girl came out. The midwife brought her through my legs so I could see her and that’s when my husband cut her cord, which was memorable and overwhelming for him. I was the happiest person, I had the biggest smile on my face: to me this was a beautiful birth. Thanks to the wonderful midwives – it goes to show that with the right help and guidance you can overcome your fears and anxieties with positive thinking.

Albers LL. The duration of labor in healthy women. Journal of Perinatology. 1999;19(2):114-119.

Aldrich CJ, D’Antona D, Spencer JA, et al. The effect of maternal pushing on fetal cerebral oxygenation and blood volume during the second stage of labour. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1995;102(6):448-453.

Anderson G. A concept analysis of ‘normal birth’. Evidence Based Midwifery. 2003;1(2):48-54.

Anderson GC, Moore E, Hepworth J, et al. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2003. CD003519

Anim-Somuah M, Smyth R, Howell C. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2005. CD000331

Benyon C. The normal second stage of labor: a plea for reform in its conduct. Kitzinger S, Simkin P, editors. Episiotomy and the second stage of labor, 64. Pennypress, Seattle, 1990:815-820. 1990 2nd edn. (Originally published in 1957 in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Empire

Carroli G, Belizan J. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):1999. CD000081

COMET (Comparative Obstetric Mobile Trial Study Group)UK, 2001. Effect of low-dose mobile versus traditional epidural techniques on mode of delivery: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2001;358:19-23.

Cotzias C, Cox J, Osuagwu F, et al. Does an inflatable obstetric belt assist in the second stage of labour? British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;105(Suppl 17):84.

Crawford JS. The stages and phases of labour: outworn nomenclature that invites hazard. The Lancet July. 1983:271-272.

Downe S. How average is normality? British Journal of Midwifery. 1994;2(7):303-304.

Downe S. Normal birth, evidence and debate, 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier, 2008.

Downe S. The concept of normality in the maternity services: application and consequences. In Frith L, editor: Ethics and midwifery: issues in contemporary practice, 2nd edn, Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann, 2004.

Downe S, Young C, Hall-Moran V, Trent Midwifery Research Group. Multiple midwifery discourses: the case of the early pushing urge. In: Downe S, editor. Normal birth, evidence and debate. Oxford: Elsevier, 2008.

Downe S, Gerrett D, Renfrew MJ. A prospective randomised trial on the effect of position in the passive second stage of labour on birth outcome in nulliparous women using epidural analgesia. Midwifery. 2004;20(2):157-168.

Downe S. Engaging with the concept of unique normality in childbirth. British Journal of Midwifery. 2006;14(6):352-356.

El-Nemer A, Downe S, Small N. ‘She would help me from the heart’: an ethnography of Egyptian women in labour. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62(1):81-92.

Enkin M, Keirse MJNC, Neilson J, et al. A guide to effective care in pregnancy and childbirth, 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Fraser WD, Marcoux S, Krauss I, et al. Multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of delayed pushing for nulliparous women in the second stage of labor with continuous epidural analgesia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;182(5):1165-1172.

Gordon B, Mackrodt C, Fern E. The Ipswich Childbirth Study: 1. A randomised evaluation of two stage postpartum perineal repair leaving the skin unsutured. British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 1998;105(4):435-440.

Gould D. Normal labour: a concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000;31(2):418-427.

Gupta JK, Hofmeyr GJ, Smyth R. Position in the second stage of labour for women without epidural anaesthesia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2004. CD002006

Halldorsdottir S, Karlsdottir SI. Empowerment or discouragement: women’s experience of caring and uncaring encounters during childbirth. Health Care for Women International. 1996;17(4):361-379.

Hobbs L. Assessing cervical dilatation without VEs; watching the purple line. The Practising Midwife. 1998;1(11):34-35.

Hodnett ED, Gates S, Hofmeyr GJ, et al. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2003. CD003766

Humphrey MD, Chang A, Wood EC, et al. A decrease in fetal pH during the second stage of labour when conducted in the dorsal position. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, British Commonwealth. 1974;81:600-602.

Hutton EK, Hassan ES. Late vs early clamping of the umbilical cord in full-term neonates: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297(11):1241-1252.

Jackson H, Melvin C, Downe S. Midwives and the fetal nuchal cord: a survey of practices and perceptions. Journal of Midwifery and Womens Health. 2007;52:49-55.

Keane HE, Thornton JG. A trial of cetrimide/chlorhexidine or tap water for perineal cleaning. British Journal of Midwifery. 1998;6(1):34-37.

Kettle C, Johanson RB. Continuous versus interrupted sutures for perineal repair. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):1998. CD000947

Kettle C, Johanson RB. Absorbable synthetic versus catgut suture material for perineal repair. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):1999. CD000006

Kurz CS, Schneider H, Hutch R, et al. The influence of maternal position on the fetal transcutaneous oxygen pressure. Journal of Perinatal Medicine. 1982;10(Suppl 2):74-75.

Liu WF, Harrington T. Delivery risk factors for meconium aspiration syndrome American. Journal of Perinatology. 2002;19(7):367-378.

McCandlish R, Bowler U, van Asten H, et al. A randomised controlled trial of care of the perineum during second stage of normal labour. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;105(12):1262-1272.

Mercer J, Skovgaard R. Fetal to neonatal transition: first, do no harm. In: Downe S, editor. Normal birth, evidence and debate. Oxford: Elsevier, 2004.

Mercer J, Skovgaard R, Peareara-Eaves J, et al. Nuchal cord management and nurse midwifery practice. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2005;50(5):373-379.

Mercer JS, Erickson-Owens DA, Graves B, et al. Evidence-based practices for the fetal to newborn transition. Journal of Midwifery Women’s Health. 2007;52(3):262-272.

Montgomery T. Physiologic considerations in labor and the puerperium. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Oct. 706, 1958.

NICE. The use of electronic fetal monitoring. 2001. Online. Available: http://www.nice.org.uk.

NHS Wales. All Wales Clinical Pathway for Normal Labour. 2007. Online. Available: http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sites3/page.cfm?orgid=327&pid=5786, 2006 15 May.

NICE. Intrapartum care: management and delivery of care to women in labour. 2007. Online. Available: http://www.nice.org.uk.

Oboro VO, Tabowei TO, Loto OM, et al. A multicentre evaluation of the two-layered repair of postpartum perineal trauma. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2003;23(1):5-8.

Petersen L, Besuner P. Pushing techniques during labor: issues and controversies. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 1997;26(6):719-726.

RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists). Materials and methods used in perineal repair: Green top guideline. 2004. Online. Available: http://www.rcog.org.uk/resources/Public/pdf/perineal_repair.pdf, 2007 24 May 2004

RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists). The management of third and fourth degree perineal tears. Green-top Guideline No. 29. 2007. Online. Available http://www.rcog.org.uk/index.asp?PageID=532, 2007 15 May 2007

Roberts J, Hanson L. Best practices in second stage labor care: maternal bearing down and positioning. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2007;52(3):238-245.

Russell JGB. Moulding of the pelvic outlet. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1969;76:817-820.

Saunders NJ, Spiby H, Gilbert L, et al. Oxytocin infusion during second stage of labour in primiparous women using epidural analgesia: a randomised double blind, placebo controlled trial. British Medical Journal. 1989;299(6713):1423-1426.

Simkin P, Ancheta R. Labor progress handbook, 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell, 2006.

Simpson KR, James DC. Effects of immediate versus delayed pushing during second-stage labor on fetal well-being: a randomized clinical trial. Nurse Researcher. 2005;54(3):149-157.

Stewart P, Spiby H. A randomized study of the sitting position for delivery using a newly designed obstetric chair. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1989;96(3):327-333.

Stremler R, Hodnett E, Petryshen P, et al. Randomized controlled trial of hands-and-knees positioning for occipitoposterior position in labor. Birth. 2005;32(4):243-251.

Sutton J, Scott P. Understanding and teaching optimal fetal positioning, 2nd edn. Tauranga: Birth Concepts, 1996.

Thomson AM. Pushing techniques in the second stage of labour. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1993;18(2):171-177.

Torvaldsen S, Roberts CL, Bell JC, et al. Discontinuation of epidural analgesia late in labour for reducing the adverse delivery outcomes associated with epidural analgesia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2004. CD004457

Turner MJ, Romney ML, Webb JB, et al. The birthing chair: an obstetric hazard? Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1986;6:232-235.

Turner MJ, Sil JM, Alagesan K, et al. Epidural bupivacaine concentration and forceps birth in primiparae. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1988;9(2):122-125.

White G. You cope by breaking down in private: fathers and PTSD following childbirth. British Journal of Midwifery. 2007;15(1):39-45.

Wickham S. Assessing cervical dilatation without VEs: watching the purple line. Practising Midwife. 2007;10(1):26-27.

Davis E. Heart and hands: a midwife’s guide to pregnancy and birth, 4th edn. Berkeley: Celestial Arts, 2004.

This is a manual of midwifery based on the skills and experiences gained by lay midwives working in America. If offers unique tips and insights.

Floyd-Davis R, Sargent CF. Childbirth and authoritative knowledge: cross-cultural perspectives. California: University of California Press, 1997.

A seminal work, which explores how authority is given to certain kinds of knowledge, and how the knowledge and expertise of women and of less dominant cultures is not privileged, even in the area of childbirth, and even in the face of the evidence.

Leap N, Hunter B. The midwife’s tale: an oral history from handywoman to professional midwife. London: Scarlet Press, 1993.

This is an historical account of trained midwives and laywomen practising in the 1950s. The stories of their experiences and responsibilities while attending women in labour are fascinating. The final chapter offers some accounts of labours from the point of view of women themselves.

Mother friendly campaign. Online. Available: http://www.motherfriendly.org/MFCI/steps.html, 22 May 2007.

This international campaign is modelled on the baby friendly initiative, and is based on 10 key steps which are believed to promote optimal births for mother and baby.

RCM campaign for normal birth. Online. Available: http://www.rcmnormalbirth.org.uk, 22 May 2007.

The campaign was set up by the Royal College of Midwives to inspire and support normal birth practice in the midwifery profession. It is a web-based initiative, using real stories and midwives experiences, underpinned with a sound evidence base.

Walsh D. Evidence based care for normal labour and birth. London: Routledge, 2007.

A clearly written overview of both formal and informal evidence that effectively integrates narrative, evidence, and experiential learning.