Chapter 56 Maternal and perinatal health, mortality and statistics

It is a woman’s basic right to achieve optimal health throughout pregnancy and childbirth for themselves and their newborns. (WRA 2007)

In the UK, the lifetime risk of a mother dying as a result of pregnancy or childbirth is approximately 200 times less than the lifetime risk for women in developing countries; 99% of the world’s maternal deaths occur in developing countries (WHO 2004) and similarly 98% of perinatal deaths, the majority of which could be prevented (WHO 2006a). However, despite the increased maternal and perinatal survival in the industrialized world, many of the deaths that do occur are due to substandard care given by clinicians and midwives and thus may be avoided.

Maternal health in the UK

The changing profile of the national population impacts on the services that are required to provide the maternity population with the most appropriate care. Specific changes both in areas of public health and culture have been widely documented in recent years. It is important that midwives are aware of these changes as they may contribute to the reason why outcomes, both maternal and perinatal have not improved for pregnant women over the past 20 years.

Three of the issues identified as increasing risk of poor pregnancy outcome are the changing age distribution, increasing obesity and changing ethnicity profiles within local populations, including inward migration of women in the childbearing age group. Although these factors do not in themselves cause poor outcomes, maternal and perinatal mortality data show that all three lead to an increased risk for these women.

In 2004, the fertility rate in women aged 30–34 increased by nearly 5% to 99.4/1000 women since the previous year. This meant that for the first time women in this age group had a higher fertility rate than those in the 25–29 age group. It was also the highest fertility rate recorded in any age group since 1998 (ONS 2005). This trend is also mirrored in the 40–44 year age group; in 2004 15.3/1000 women had a pregnancy resulting in childbirth whereas this figure was only 7.6 in 1994. The maternal mortality rate is seen to increase for women over 35 years of age (Lewis 2007, Lewis & Drife 2004). Similarly perinatal mortality was shown to increase for women at both extremes of age groups; <20 and >40, when compared with other age groups (CEMACH 2007b).

Obesity is also observed to increase maternal and perinatal mortality (CEMACH 2007b, Lewis 2007). The increase in body mass index (BMI) in the general population is reflected in the maternal population and will therefore be an increasing issue in the provision of maternal care. Taking a BMI of >30 as a definition used by the Information Centre’s Health Survey, obesity in women has increased from 16.4–24.8% between 1993 and 2005 (The Information Centre 2006). This is most prevalent in women of Black African, Black Caribbean and Pakistani ethnicity. The same survey identified an increase in obesity in female children of 12–18.1% between 1995 and 2005, which has implications for the future childbearing population.

Obese women are also 13 times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes which increases their risk of poor pregnancy outcome, as discussed later in this chapter (CEMACH 2007a).

Ethnicity of the population in the UK is changing over time. More recently, with the opening up of the European Union, there has been an inward migration of women in the childbearing population. Between 1995 and 2005 there has been a two-fold increase in the percentage of live births to women from other European Union countries, from 1.7% to 3.2%. The total percentage of live births to women from outside the UK has increased from 12.6% to 20.8% in the same period (National Statistics 2005).

Maternal mortality in the UK

The tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death (ICD10), defines a maternal death as ‘the death of a woman while pregnant, or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, from any cause related to, or aggravated by the pregnancy, or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes’.

Maternal deaths are routinely classified into a number of categories as defined below.

Direct deaths

Deaths within 42 days of delivery, termination or abortion resulting from obstetric complications of the pregnant state (pregnancy, labour and puerperium), from interventions, omissions, incorrect treatment or from a chain of events resulting from any of the above, e.g. thrombosis. This 42-day limit is an internationally recognized standard.

Indirect

Deaths within 42 days of delivery, termination or abortion resulting from previous existing disease, or disease that developed during pregnancy and which was not due to obstetric causes, but which was aggravated by the physiological effects of pregnancy, e.g. cardiac disease.

Coincidental (fortuitous)

Deaths from unrelated causes which happen to occur in pregnancy or the puerperium. The term ‘coincidental’ is now preferred to ‘fortuitous’ as being more appropriate and sensitive, e.g. road traffic accidents.

Late

Deaths occurring between 42 days and 1 year after delivery, termination or abortion, that are due to Direct or Indirect causes.

There are two routinely used measures of maternal mortality; maternal mortality rate and maternal mortality ratio. There are important differences in their definitions. The international definition of maternal mortality ratio is Direct and Indirect deaths per 100 000 live births.

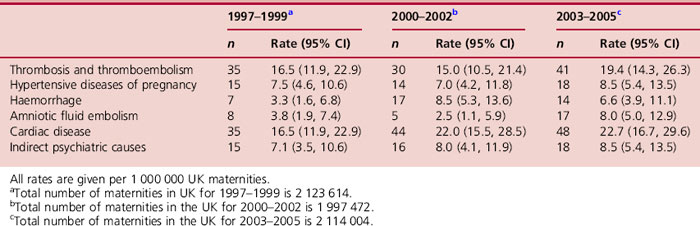

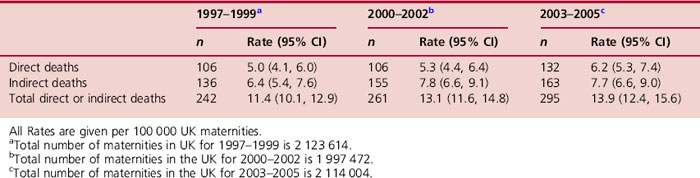

In the UK, when discussing rates of maternal death, they are defined as Direct and Indirect deaths per 100 000 maternities. Maternities encompass the number of pregnancies that result in a live birth, at any gestation, and stillbirths occurring at or after 24 weeks of completed gestation (required to be notified by law). The latest published maternal mortality ratio in the UK is 13.8 (n = 295) per 100 000 live births, while the UK maternal mortality rate is 13.9 (n = 295) per total births (Table 56.1) (Lewis 2007).

Table 56.1Direct and Indirect maternal mortality rates/100 000 maternities as reported to the Registrars General (ONS) and to the Enquiry: UK 1997 2005

The UK maternal mortality rate dropped considerably in the mid-1990s before reaching a plateau towards the end of the decade. However, there has been a small increase in the number of deaths since 1999 (Lewis 2007). These changes in trend have been attributed to a number of factors:

The main causes of Direct death have remained very much unchanged over the past 50 years. These deaths were predominantly due to thrombosis and thromboembolism, hypertensive disease of pregnancy, haemorrhage and amniotic fluid embolism (Table 56.2). The main causes of Indirect death are those related to cardiac conditions and deaths associated with psychiatric illness (see Ch. 36B).

Avoidable factors identified through the confidential enquiries into UK maternal deaths during 2003–2005 (Lewis 2007) were in many cases assessed to have been due to healthcare professionals failing to recognize and manage common medical conditions or potential emergencies outside their immediate area of expertise. In addition, resuscitation skills were considered to be unacceptably poor in some cases.

It is the responsibility of the midwife to maintain and update her skills and knowledge to ensure she can appropriately recognize deviations from normal and act and refer appropriately (NMC 2004, 2008).

A satisfactory healthcare system should include maternity and peripartum services such as to ensure that every pregnant woman emerges from the birth as a healthy mother with an equally healthy term baby. Indeed, such an outcome is vital since mother–child bonding is more likely to occur successfully when both are physically and mentally healthy. An inability to bond is not only a personal tragedy for the family, but could precipitate later problems which may result in health-related complications. Furthermore, where a pregnancy results in death of the mother, child or both, this has repercussions not only for the family and friends, but also healthcare professionals involved in the care. Moreover, it is almost impossible to estimate the effect of losing a mother on any older children. Thus, despite the perceived small number of maternal deaths, their impact should not be underestimated, and it is imperative that efforts to reduce this number further are not diminished.

Providing healthcare during pregnancy

There have been a number of government initiatives set up to try to identify and address some of the issues for women accessing maternity services with the aim of maternal health and outcomes for pregnant women in the UK. These include: the National Service Framework for Children and Young People (NSF) (DH 2004), Changing Childbirth (DoH 1993), and Maternity Matters (DH 2007).

Some of the risk factors for poor maternal outcomes which have been identified by these initiatives and also the reports on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the UK (Lewis 2007, Lewis & Drife 2004) are listed below:

There has been much investigation into the role of substandard care in maternal morbidity and mortality, since this is the most obvious factor that can be practically addressed in improving services. Substandard care can be divided into two categories: (1) Major substandard care where substandard care contributed significantly to the death of the mother, and thus the death was likely to be avoidable, and (2) Minor substandard care where the standard of care was a relevant contributory factor to the death, but the mother’s survival was unlikely in any case. In their investigation of all maternal deaths occurring in 2003–2005, the confidential enquiry reported that 55% of mothers who died from Direct causes were assessed to have had major substandard care (Lewis 2007). This is not only a disturbing indictment on a small minority of healthcare professionals, but also demonstrates the comparative ease with which significant decreases in maternal deaths could be made.

Perinatal and neonatal mortality

Recent studies suggest over 1 in 200 pregnancies end in stillbirth and around 1 in 300 babies die in the first 4 weeks following birth (CEMACH 2007b). While a number of these deaths may not be preventable, it is imperative that thorough surveillance systems remain in place to allow identification of trends and problem areas.

Perinatal mortality includes all stillbirths and deaths of live born babies in the first week of life.

The rates of neonatal deaths are commonly calculated per 1000 live births, while rates for stillbirth are given per 1000 live births and stillbirths total births.

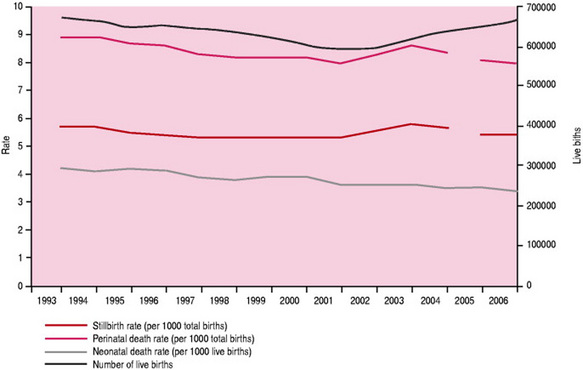

Since 1992 the stillbirth rate has remained largely unchanged. However, the neonatal mortality has declined significantly (Fig. 56.1).

Figure 56.1 Stillbirth and neonatal mortality, England and Wales 1993–2006.

(From ONS and CEMACH.) Note: Stillbirths were defined using the RCOG Guidance from 2005.

While there has been an increase in the neonatal survival rate of very pre-term babies, no progress has been made in reducing the overall stillbirth rate (CEMACH 2007b).

In looking for explanations of long-term trends it is important to take account of a wide range of factors such as the establishment of the NHS in 1948. The passing of the Abortion Act 1967 has resulted in the termination of many pregnancies for congenital abnormalities and thus the removal of deaths from these causes from the perinatal mortality statistics.

The re-definition in 1992 of the age of legal viability of a fetus as being 24 weeks’ instead of 28 weeks’ gestation has brought more babies within the definition of stillbirth. Consequently, there has been an increase in perinatal mortality figures over this time period. However, more recent guidelines for stillbirth have been released in an effort to provide health professionals with advice on how to interpret the current law, particularly around the issue of a fetus that has died in utero before 24 weeks, but delivered after 24 weeks (RCOG 2005). This has led to a slight decrease in the published stillbirth rates from 2005 (CEMACH 2007b).

Causes of mortality which have occurred at a relatively consistent rate over the last 5 years include low birthweight, (pre-term and small-for-gestation babies), intrauterine hypoxia, respiratory depression at birth, intracranial injury and congenital abnormality. However, the cause of death in around 50% of stillbirths is not identified (CEMACH 2007b). The main causes of early neonatal death are congenital anomaly and immaturity, and the causes of late neonatal death are immaturity and infection.

It may be impossible to attribute a perinatal death to any one of the listed causes, but a combination of predisposing factors increases the risk of death. These include:

Thus it can be seen that issues that increase the risk of perinatal mortality, in many cases, unsurprisingly mirror those listed for maternal mortality. Furthermore, suboptimal care has also been found to be an issue in perinatal mortality. In common with many other conditions, social class has been shown to be an important determinant of outcome.

Infant mortality

An infant death is defined as occurring in the first year of life. Thus this includes all neonatal deaths; the remainder are termed post neonatal deaths (28–364 days). The infant mortality rate is calculated per 1000 live births. This rate is taken as an important measure of the health of the population of a nation.

Some of the essential causes that a midwife should be aware of are non-accidental injury, infection and, in older babies, accidents in the home. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) is also significant; these are unexpected deaths in which no cause is identified.

In a study investigating sudden unexpected deaths in infancy (SUDI) between the ages of 1 and 52 weeks (Fleming et al 2000), a total of 418 infant deaths were examined. A total of 93 were explained, and nearly half of these showed signs of illness severe enough to need medical attention in the 24 hrs preceding death, using the criteria of the Cambridge Baby Check (Morley et al 1991).

Investigation into the causes of post-neonatal death has led to a number of key points and recommendations to be made, based on evidence presented in a number of studies. These have been produced as a leaflet by the Foundation for the Study of Infant Death (FSID):

Fleming et al comment that, although sudden infant death has fallen substantially since the ‘back to sleep’ campaign in 1991, SUDI remain the largest single group of deaths in the post-neonatal period (Fleming et al 2000). Robinson (1996) points out the international success of the campaign, but also stresses the continuing adverse influence of poverty.

The key points above should be discussed with the parents by the midwife early in the postnatal period and should be included within the programme for parent care classes.

The role of the midwife

Midwives can contribute towards optimizing the care given to each woman on two levels: ensuring a positive experience for the mother of childbirth as a crucial life-event, and more broadly, by reducing maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. These have been discussed in previous chapters, and opportunities to improve care are given in the key recommendations and those specifically for midwives in the Confidential Enquiry Reports (Lewis 2007, Lewis & Drife 2004).

Caring for the bereaved family, as discussed in Chapter 38, is also part of the midwife’s role. Often, the only link for the family with the deceased, whether it be a mother or the baby, is through the place where the death occurred and with the staff involved at the birth.

The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH)

CEMACH is commissioned by the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) to carry out surveillance and confidential enquiry topic-work with the aim of improving the health of mothers, babies and children. CEMACH operates throughout England, Wales and Northern Ireland. NHS Quality Improvement Scotland (NHS QIS) has participated fully in the maternal health aspects of the enquiry work since 2006.

There are two streams of work: (1) surveillance of maternal, perinatal and child mortality and (2) confidential enquiry work into specific topics in mortality and/or morbidity.

The continuation of reporting of maternal and perinatal surveillance is important for the following reasons:

The enquiry work includes the confidential enquiry into maternal deaths, plus project work on topics which have been identified as impacting negatively on maternal or perinatal mortality and morbidity rates. This enables further exploration of maternal and perinatal health issues as they arise and evolve, allowing for the formulation of appropriate public health initiatives.

Reporting responsibilities following a maternal death

There is a statutory requirement for all maternal deaths (occurring up to 42 days postpartum) to be notified to the Strategic Health Authority (SHA) within the area where the death occurred. This action is the responsibility of the designated supervisor of midwives (SoM) within the Trust whose SHA relationship is directly with the local supervising authority midwifery officer (LSAMO). The SoM also informs the CEMACH regional office of the maternal death. Once a death has been notified to CEMACH, the confidential enquiry is initiated. A proforma is sent to the Trust which requests information about the mother and the care provided to her during her pregnancy, the birth of her baby and in the time leading up to her death. The CEMACH team also seek other sources of information from the GP, specialist services and post mortem. If relevant, the coroner’s report is also obtained.

The case then undergoes regional and central assessment. A crucial role of the assessment procedure is to ascertain which, if any, of these deaths were avoidable and identify those factors which directly resulted in the poor outcome. This review also seeks to identify both substandard and good practices. Analysis and aggregation of all maternal and perinatal deaths in the UK provides a means of identifying trends by which recommendations for service provision, clinical practice and other public health initiatives are derived.

There are a number of other department leads who must be notified including the clinical risk manager of the Trust. It is their responsibility to ensure that a serious untoward incident is recorded and an internal review of the circumstances around the death carried out as promptly as possible.

Notification of perinatal death

All deaths of babies from 24 weeks’ gestation to 28 days postpartum should be reported to CEMACH as soon as possible using the perinatal death notification (PDN) form (most units have an allocated midwife responsible for ensuring all perinatal deaths are notified to CEMACH). This surveillance system is also used to inform future topic-specific work due to the significant contribution each makes to the perinatal and neonatal mortality rates.

As data are analysed both nationally and on a local level, it is possible to identify and feedback emerging trends specific to a locality. On-going surveillance and production of trend data are essential for identification of topics for future research.

Recent projects

Outcomes for babies born at 27–28 weeks’ gestation (Macintosh 2003)

The Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy (CESDI) carried out a study looking at outcomes for babies born at 27–28 weeks’ gestation. The main issues identified were substandard care or lack of current guidelines: this was observed more frequently in babies who died. Two key points where midwives could make a difference when caring for women in pre-term labour were:

CEMACH diabetes programme

The purpose of this programme was to audit the provision of services and care for women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes during pregnancy.

The standards used for the audit were those set out in the National Service Framework for Diabetes (DH 2001).

The key findings and recommendations were divided into clinical issues, aimed at improving practice and policy, and social and lifestyle issues recommending how service providers could engage and empower women by educating them to better understand the importance of managing their diabetes prior to, during and after pregnancy.

Maternal and perinatal mortality: an international perspective

Maternal mortality and perinatal mortality rates remain the highest in the developing world; 95% of maternal deaths occur in Africa and Asia with only 1% in developed countries. Indeed, both maternal and perinatal mortality rates are increasing in some less developed countries (Lawn et al 2005, WHO 2004). The perinatal mortality rate in Western Africa is almost 10 times that seen in North America. A total of 30% of global births occur in South-Central Asia and this region accounts for almost 40% of perinatal deaths. This gives a clear indication that the majority of maternal deaths are avoidable or preventable.

Reasons for the inequitably high maternal mortality rates in developing countries are attributed mainly to the lack of skilled healthcare available to these women, particularly teenagers who are less likely to access care if available (Magadi et al 2007). Maternal mortality occurs more frequently around the time of birth due predominantly to the result of haemorrhage, infections and hypertensive disorders and in some countries, unsafe abortion. Thus, both a lack of resource and background social and cultural circumstances can be seen to have a role in the international disparity.

Although overall mortality rates are much lower when investigating developed countries, important differences occur between them. ‘Western’ countries commonly report better outcomes with maternal mortality of between 7 and 13/100 000 live births in Western Europe; the UK rate is 13.9 and France 9–13 in 2001 (Bouvier-Colle et al 2001). Similarly, the USA report a rate of 12.9/100 000 live births 2001 (Berg et al 2003). However, Eastern Europe displays a differing picture with rates ranging from 50/100 000 live births in Georgia to 18 in Azerbaijan in 2003 (WHO 2006b). However, these figures may be an underestimate in some countries. It has been suggested that under-reporting may range from 22% in France to 93% in Massachusetts. This may also be an issue in developing countries as births may take place at home and mortality may not be registered or reported. It is very difficult to identify comparative international maternal and perinatal mortality rates as each country collects and presents its data in differing ways and for different years.

While the mortality rates for developed countries are favourable as a whole when compared with those from the developing world, it must be remembered that there still may be wide disparity within countries with regard to pregnancy outcomes, with key groups more likely to have a poorer outcome. For example, it has been clearly shown that babies born to parents with lower socioeconomic status are more likely to have low birthweight compared to babies born to parents from higher socioeconomic backgrounds. It has also been shown that the indigenous Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women have a maternal mortality rate greater than that of the general Australian population during 2000–2002 (AIHW 2006). Thus many of the resource, training, social, economic and cultural issues must still be addressed within countries. However, these issues can be very different to those previously discussed; e.g. the increased availability of fertility treatment resulting in multiple pregnancy and/or pre-term birth.

Programmes addressing the issues of treatable infectious diseases, such as malaria, have helped to improve the underlying health of women across the world, with particular effects on women from regions where these conditions are endemic. Furthermore, there is a greater understanding of appropriate nutrition, including the availability of vitamin and other supplements. The subsequent increased health of women of childbearing age has resulted in increased positive outcomes in pregnancy.

To attempt to address global maternal mortality 189 countries pledged support to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000 (UN 2000).

However, to be effective in meeting these goals there has to be political commitment (Filippi et al 2006) (see Ch. 55).

Notification of birth

In 1915, it became a statutory requirement for the early notification of a birth. It is the duty of the father or any other person in attendance, or present within 6 hrs of the birth, to notify the appropriate medical officer within 36 hrs. It is usually the midwife who carries out this responsibility as notification of birth in the UK is now electronic. Notification applies to the birth of all live and stillborn babies but not those born before 24 completed weeks of pregnancy. The birth information is made available to the Registrar of Births and Deaths in the district in which the birth took place and also to the primary healthcare services to enable appropriate care to be planned.

Registration of birth

Under the Births and Deaths Registration Act 1953 all births must be registered within 6 weeks (3 weeks in Scotland). If the father or mother fails to do so then the Registrar will request any other person present or at the birth to complete the registration details. If the father and mother are not married then, if attending above, the father must take with him a Statutory Declaration made by the mother that he is the father of the baby.

The choice of surname needs to be carefully considered by the mother as it is only possible to change surnames in particular circumstances, e.g. if she later marries the father and she wants the father’s surname.

Stillbirths

A baby born after the 24th week of pregnancy and ‘which did not at any time after being completely expelled from its mother, breathe or show any other sign of life’ is called a stillbirth under the Births and Deaths Registration Act 1953 (as amended by the Stillbirth [Definition] Act 1992). A medical practitioner, or a midwife present at the birth, may write and sign a stillbirth certificate. If the parents wish to have the baby cremated, rather than buried, then the signature must be that of a medical practitioner.

Registration of stillbirth has to be undertaken by the parents before the Registrar will issue a certificate for burial or cremation (see NMC 2004).

Registration of deaths is the responsibility of the family. If the baby died shortly after birth, both the birth and death have to be registered.

Summary

The role of the midwife is central to the care and successful outcome for mothers accessing maternity care in the UK. It is therefore crucial that all midwives follow the NMC Code (2008) and rules (NMC 2004) and participate in local and national surveillance, audit and research. Midwives should not underestimate their essential role in these processes and must be aware that any recommendations and new initiatives should directly inform their work.

AIHW. Maternal deaths in Australia 2000–2002: Maternal deaths, Series No. 2. Canberra: The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare National Perinatal Statistics Unit, 2006.

Berg CJ, Chang J, Callahan WM, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2003;101(2):289-296.

Bouvier-Colle MH, Pequignot F, Jougla EJ. Maternal mortality in France: Frequency, trends and causes. Journal de gynécologie, obstétrique et biologie de la reproduction. 2001;30(8):768-775.

CEMACH. Maternity Services in 2002 for women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in pregnancy. London: Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health. RCOG Press, 2004.

CEMACH. Pregnancy in women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in 2002–2003, England, Wales and Northern Ireland. London: Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health. CEMACH, 2005.

CEMACH. Diabetes in Pregnancy: Are we providing the best care? Findings of a national confidential enquiry: England Wales and Northern Ireland. London: Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health. CEMACH, 2007.

CEMACH. Confidential enquiry into Maternal and Child Health. Perinatal mortality 2005: England, Wales and Northern Ireland. London: CEMACH, 2007.

DoH (Department of Health). Changing childbirth. London: HMSO, 1993.

DH (Department of Health). National Service Framework for Diabetes: standards. London: DH, 2001.

DH (Department of Health). National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services, Standard 11. London: Maternity Services. DH, 2004.

DH (Department of Health). Maternity Matters: choice, access and continuity of service in a safe service. London: DH, 2007.

Filippi V, Ronsmans C, Campbell OM, et al. Maternal health in poor countries: the broader context and a call for action. Lancet. 2006;368:1535-1541.

Fleming P, Blair P, Bacon C, et al, editors. Sudden unexpected deaths in infancy: the CESDI SUDI studies 1993–1996. London: The Stationery Office, 2000.

Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J, the Lancet Neonatal Steering group team. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet. 2005;365(9462):891-900.

Lewis G, Drife J, editors. Why Mothers Die 2000–2002; sixth report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. London: RCOG, 2004.

Lewis G, editor. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer 2003–2005. The seventh report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. London: CEMACH, 2007.

Macintosh M. Project 27/28: An enquiry into quality of care and its effects on the survival of babies born at 27–28 weeks. London: CESDI. The Stationery Office, 2003.

Magadi MA, Agwanda AO, Obare FO. A comparative analysis of the use of maternal health services between teenagers and older mothers in sub-Saharan Africa; evidence from demographic and health surveys (DHS). Social Science and Medicine. 2007;64(6):1311-1325.

Morley CJ, Thornton AJ, Cole TJ, et al. Baby check: a scoring system to grade the severity of acute illness in babies under six months old. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1991;66:100-106.

National Statistics. Birth statistics: Review of the Register General on Births and patterns of family building in England and Wales. Series FM1, No. 34.. 2005. Online. Available www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_population/FM1_34/FM1_no34_2005.pdf, 18 May 2007

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council). Midwives Rules and Standards. London: NMC, 2004.

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council). The Code: Standards of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives. London: NMC, 2008.

ONS (Office for National Statistics). Online. Available www.statistics.gov.uk/pdfdir/birthstats1205.pdf, 2005. 18 May 2007

RCOG. Registration of stillbirths and certification of pregnancy loss before 24 weeks’ gestation. Good Practice No. 4. London: RCOG, 2005.

Robinson J. The emperor’s new clothes. British Journal of Midwifery. 1996;4(11):609-610.

The Information Centre. Statistics on obesity, physical activity and diet: England. 2006. Online. Available www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications/opan06/OPAN%20bulletin%20finalv2.pdf, 21 May 2007

UN. United Nations Millennium Development Goals. 2000. Online. Available www.un.org/millenniumgoals, 20 May 2007

WHO. Maternal mortality in 2000: Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. 2004. Online. Available www.who.int/reproductive-health/global_monitoring/index, 12 May 2007

WHO. Neonatal and perinatal mortality: country, regional and global estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006.

WHO. Highlights on health: Georgia. 2006. Online. Available www.euro.who.int/eprise/main/WHO/Progs/CHHGEO/cismortality/20060209_1, 18 May 2007

WRA. The White Ribbon Alliance for Safe Motherhood. 2007. Online. Available www.whiteribbonalliance.org/About/default.cfm?a0=mission, 17 May 2007