CHAPTER 13 Preparation of the Mouth for Removable Partial Dentures

The preparation of the mouth is fundamental to a successful removable partial denture service. Mouth preparation, perhaps more than any other single factor, contributes to the philosophy that the prescribed prosthesis not only must replace what is missing but also must preserve the remaining tissues and structures that will enhance the removable partial denture.

Mouth preparation follows the preliminary diagnosis and the development of a tentative treatment plan. Final treatment planning may be deferred until the response to the preparatory procedures can be ascertained. In general, mouth preparation includes procedures in four categories: oral surgical preparation, conditioning of abused and irritated tissues, periodontal preparation, and preparation of abutment teeth. The objectives of the procedures involved in all four areas are to return the mouth to optimum health and to eliminate any condition that would be detrimental to the success of the removable partial denture.

Naturally, mouth preparation must be accomplished before the impression procedures are performed that will produce the master cast on which the removable partial denture will be fabricated. Oral surgical and periodontal procedures should precede abutment tooth preparation and should be completed far enough in advance to allow the necessary healing period. If at all possible, at least 6 weeks, and preferably 3 to 6 months, should be provided between surgical and restorative dentistry procedures. This depends on the extent of the surgery and its impact on the overall support, stability, and retention of the proposed prosthesis.

Oral Surgical Preparation

As a rule, all pre-prosthetic surgical treatment for the removable partial denture patient should be completed as early as possible. When possible, necessary endodontic surgery, periodontal surgery, and oral surgery should be planned, so that they can be completed during the same time frame. The longer the interval between the surgery and the impression procedure, the more complete the healing and consequently the more stable the denture-bearing areas.

A variety of oral surgical techniques can prove beneficial to the clinician in preparing the patient for prosthetic replacements. However, it is not the purpose of this section to present the details of surgical correction. Rather, attention is called to some of the more common oral conditions or changes in which surgical intervention is indicated as an aid to removable partial denture design and fabrication, and as an aid to the successful function of the restoration. Additional information regarding the techniques used is available in oral surgery texts and journal publications. It is important to emphasize, however, that the dentist who is providing the removable partial denture treatment bears the responsibility for ensuring that the necessary surgical procedures are accomplished in accordance with the treatment plan. Measures to control apprehension, including the use of intravenous and inhalation agents, have made the most extensive surgery acceptable to patients. Whether the dentist chooses to perform these procedures or elects to refer the patient to someone more qualified is immaterial. The important consideration is that the patient should not be deprived of any treatment that would enhance the success of the removable partial denture.

Extractions

Planned extractions should occur early in the treatment regimen but not before a careful and thorough evaluation of each remaining tooth in the dental arch is completed (Figure 13-1). Regardless of its condition, each tooth must be evaluated in terms of its strategic importance and its potential contribution to the success of the removable partial denture. With the knowledge and technical capability available in dentistry today, almost any tooth may be salvaged if its retention is sufficiently important to warrant the procedures necessary. On the other hand, heroic attempts to salvage seriously involved teeth or those of doubtful prognosis for which retention would contribute little if anything, even if successfully treated and maintained, are contraindicated. Extraction of nonstrategic teeth that would present complications or those that may be detrimental to the design of the removable partial denture is a necessary part of the overall treatment plan.

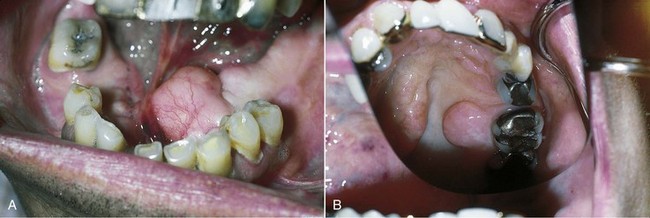

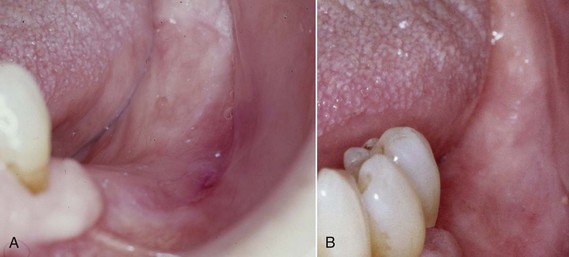

Figure 13-1 Diagnostic mounting allows confirmation of the need for extraction after clinical examination. A, Anterior tooth position and chronic periodontal disease status require extraction to address the patient’s concern of malpositioned and painful teeth. B, Root tips require immediate extraction to allow ridge healing to begin. The status of the molar (#15) requires additional workup to determine pulpal involvement of the carious lesion and the extent of occlusal reduction required to optimize the occlusal plane. The decision to maintain this tooth, although potentially costly, must consider the stabilizing effect it will have on the posterior left functional occlusion.

Removal of Residual Roots

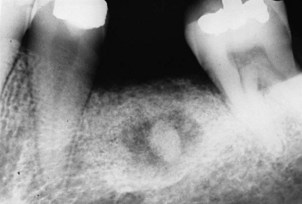

Generally, all retained roots or root fragments should be removed. This is particularly true if they are in close proximity to the tissue surface, or if associated pathologic findings are evident. Residual roots adjacent to the abutment teeth may contribute to the progression of periodontal pockets and compromise the results of subsequent periodontal therapy. Removal of root tips can be accomplished from the facial or palatal surfaces without resulting in a reduction of alveolar ridge height or endangering adjacent teeth (Figure 13-2).

Impacted Teeth

All impacted teeth, including those in edentulous areas, as well as those adjacent to abutment teeth, should be considered for removal. The periodontal implications of impacted teeth adjacent to abutments are similar to those for retained roots. These teeth are often neglected until serious periodontal implications arise.

The skeletal structure of the body changes with age. Asymptomatic impacted teeth in the elderly that are covered with bone, with no evidence of a pathologic condition, should be left to preserve the arch morphology. If an impacted tooth is left, this should be recorded in the patient’s record, and the patient should be informed of its presence. Roentgenograms should be taken at reasonable intervals to ensure that no adverse changes occur.

Alterations that affect the jaws can result in minute exposures of impacted teeth to the oral cavity via sinus tracts. Resultant infections can cause considerable bone destruction and serious illness for persons who are elderly and not physically able to tolerate the debilitation. Early elective removal of impactions prevents later serious acute and chronic infection with extensive bone loss. Any impacted teeth that can be reached with a periodontal probe must be removed to treat the periodontal pocket and prevent more extensive damage (Figure 13-3).

Figure 13-3 Lateral oblique roentgenogram showing unerupted maxillary third molar and impacted mandibular second and third molars. Maxillary third molar and mandibular second molar could be contacted by periodontal probe.

(From Costich ER, White RP Jr: Fundamentals of oral surgery, Philadelphia, 1971, Saunders.)

Malposed Teeth

The loss of individual teeth or groups of teeth may lead to extrusion, drifting, or combinations of malpositioning of remaining teeth (Figure 13-4). In most instances, the alveolar bone supporting extruded teeth will be carried occlusally as the teeth continue to erupt. Orthodontics may be useful in correcting many occlusal discrepancies, but for some patients, such treatment may not be practical because of lack of teeth for anchorage of the orthodontic appliances or for other reasons. In such situations, individual teeth or groups of teeth and their supporting alveolar bone can be surgically repositioned. This type of surgery can be accomplished in an outpatient setting and should be given serious consideration before additional teeth are condemned or the design of removable partial dentures is compromised.

Figure 13-4 A, Malpositioned maxillary dentition due to loss of posterior occlusion and excessive wear of opposing mandibular anterior teeth. B, Restored dentition made possible by a combination of endodontics, periodontics, and fixed and removable partial prosthodontics.

(Courtesy Dr. M. Alfaro, Columbus, OH.)

Cysts and Odontogenic Tumors

Panoramic roentgenograms of the jaws are recommended to survey the jaws for unsuspected pathologic conditions. When a suspicious area appears on the survey film, a periapical roentgenogram should be taken to confirm or deny the presence of a lesion. All radiolucencies or radiopacities observed in the jaws should be investigated. Although the diagnosis may appear obvious from clinical and roentgenographic examinations, the dentist should confirm the diagnosis through appropriate consultation and, if necessary, perform a biopsy of the area and submit the specimens to a pathologist for microscopic study. The patient should be informed of the diagnosis and provided with various options for resolution of the abnormality as confirmed by the pathologist’s report.

Exostoses and Tori

The existence of abnormal bony enlargements should not be allowed to compromise the design of the removable partial denture (Figure 13-5). Although modification of denture design can, at times, accommodate for exostoses, more frequently this results in additional stress to the supporting elements and compromised function. The removal of exostoses and tori is not a complex procedure, and the advantages to be realized from such removal are great in contrast to the deleterious effects that their continued presence can create. Ordinarily the mucosa covering bony protuberances is extremely thin and friable. Removable partial denture components in proximity to this type of tissue may cause irritation and chronic ulceration. Also, exostoses approximating gingival margins may complicate the maintenance of periodontal health and lead to the eventual loss of strategic abutment teeth.

Hyperplastic Tissue

Hyperplastic tissues are seen in the form of fibrous tuberosities, soft flabby ridges, folds of redundant tissue in the vestibule or floor of the mouth, and palatal papillomatosis (Figure 13-6). All these forms of excess tissue should be removed to provide a firm base for the denture. This removal will produce a more stable denture, will reduce stress and strain on the supporting teeth and tissues, and in many instances will provide a more favorable orientation of the occlusal plane and arch form for the arrangement of the artificial teeth. Appropriate surgical approaches should not reduce vestibular depth. Hyperplastic tissue can be removed with any preferred combination of scalpel, curette, electrosurgery, or laser. Some form of surgical stent should always be considered for these patients, so that the period of healing is more comfortable. An old removable partial denture properly modified can serve as a surgical stent. Although hyperplastic tissue has no great malignant propensity, all such excised tissue should be sent to an oral pathologist for microscopic study.

Muscle Attachments and Frena

As a result of the loss of bone height, muscle attachments may insert on or near the residual ridge crest. The mylohyoid, buccinator, mentalis, and genioglossus muscles are most likely to introduce problems of this nature. In addition to the problem of the attachments of the muscles themselves, the mentalis and genioglossus muscles occasionally produce bony protuberances at their attachments that may also interfere with removable partial denture design. Appropriate ridge extension procedures can reposition attachments and remove bony spines, which will enhance the comfort and function of the removable partial denture.

Repositioning of the mylohyoid muscle is successfully achieved by several methods. The genioglossus muscle is more difficult to reposition, but careful surgery can reduce the prominence of the genial tubercles, as well as provide some sulcus depth in the anterior lingual area.

Surgical procedures that use skin or mucosal grafts have largely replaced secondary epithelialization procedures for the facial aspect of the mandible. Mucosal grafts that use the palate as a donor site offer the best possibility for success; transplanted skin can be used when large areas must be grafted.

The maxillary labial and mandibular lingual frena are the most common sources of frenum interference with denture design. These can be modified easily through any of several surgical procedures. Under no circumstances should a frenum be allowed to compromise the design or comfort of a removable partial denture.

Bony Spines and Knife-Edge Ridges

Sharp bony spicules should be removed and knifelike crests gently rounded. These procedures should be carried out with minimum bone loss. If, however, correction of a knife-edge residual crest results in insufficient ridge support for the denture base, the dentist should resort to vestibular deepening for correction of the deficiency or insertion of the various bone grafting materials that have demonstrated successful clinical trials.

Polyps, Papillomas, and Traumatic Hemangiomas

All abnormal soft tissue lesions should be excised and submitted for pathologic examination before a removable partial denture is fabricated. Even though the patient may relate a history of the condition’s having been present for an indefinite period, its removal is indicated. New or additional stimulation to the area introduced by the prosthesis may produce discomfort or even malignant changes in the tumor.

Hyperkeratoses, Erythroplasia, and Ulcerations

All abnormal white, red, or ulcerative lesions should be investigated, regardless of their relationship to the proposed denture base or framework. A biopsy of areas larger than 5 mm should be completed, and if the lesions are large (over 2 cm in diameter), multiple biopsies should be taken. The biopsy report will determine whether the margins of the tissue to be excised can be wide or narrow. The lesions should be removed and healing accomplished before the removable partial denture is fabricated. On occasion, such as after irradiation treatment or the excoriation of erosive lichen planus, the removable partial denture design will have to be radically modified to avoid areas of possible sensitivity.

Dentofacial Deformity

Patients with a dentofacial deformity often have multiple missing teeth as part of their problem. Correction of the jaw deformity can simplify the dental rehabilitation. Before specific problems with the dentition can be corrected, the patient’s overall problem must be evaluated thoroughly. Several dental professionals (prosthodontist, oral surgeon, periodontist, orthodontist, general dentist) may play a role in the patient’s treatment. These individuals must be involved in producing the diagnostic database and in planning treatment for the patient. Information obtained from a general patient evaluation done to determine the patient’s health status, a clinical evaluation directed toward facial esthetics and the status of the teeth and oral soft tissues, and analysis of appropriate diagnostic records can be used to produce a database. From this database, the patient’s problems can be enumerated, with the most severe problem being placed at the top of the list. Other identified problems would follow in order of their severity. It is only after this step that input from several dentists can provide a correctly sequenced final treatment plan for the patient.

Surgical correction of a jaw deformity can be made in horizontal, sagittal, or frontal planes. The mandible and maxillae may be positioned anteriorly or posteriorly, and their relationship to the facial planes may be surgically altered to achieve improved appearance. Replacement of missing teeth and development of a harmonious occlusion are almost always major problems in treating these patients.

Osseointegrated Devices

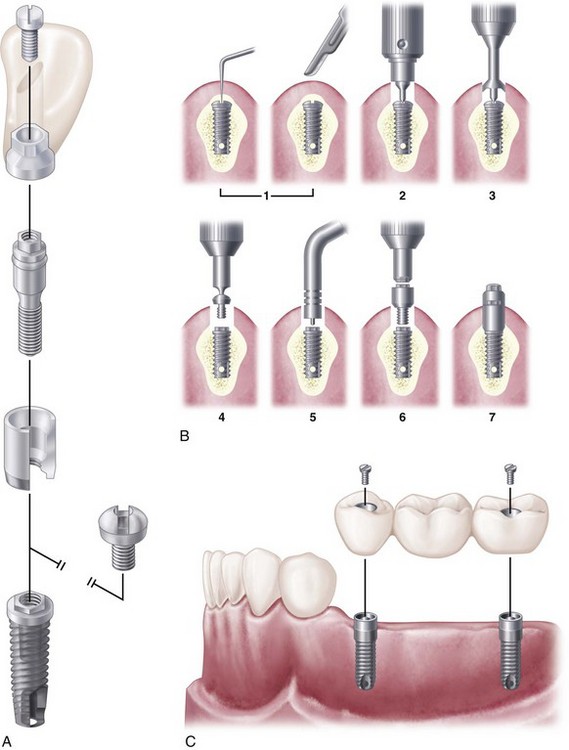

A number of implant devices to support the replacement of teeth have been introduced to the dental profession. These devices offer a significant stabilizing effect on dental prostheses through a rigid connection to living bone. The system that pioneered clinical prosthodontic applications with the use of commercially pure (CP) titanium endosseous implants is that of Brånemark and coworkers (Figure 13-7). This titanium implant was designed to provide a direct titanium-to-bone interface (osseointegrated), with basic laboratory and clinical results supporting the value of this procedure.

Figure 13-7 A, Brånemark system components. From lower to upper: implant, cover screws, abutment, abutment screw, gold cylinder, and gold screw. B, Basic procedures in second-stage surgery: (1) exploration to locate cover screw; (2) removal of soft tissue; (3) removal of bony tissue; (4) removal of cover screw; (5) use of depth gauge to measure the amount of soft tissue; (6) abutment connection; and (7) placement of healing cap. C, Diagram of freestanding three-unit fixed partial denture supported by two osseointegrated implants that restore the extension base area, which would have been restored with a Class II removable partial denture if implants had not been used.

(A and C redrawn from Hobo S, Ichida E, Garcia LT: Osseointegration and occlusal rehabilitation, Tokyo, Japan Quintessence, 1989.)

Implants are carefully placed using controlled surgical procedures and, in general, bone healing to the device is allowed to occur before a dental prosthesis is fabricated. Long-term clinical research has demonstrated good results for the treatment of complete and partially edentulous dental patients using dental implants. Although research on implant applications with removable partial dentures has been very limited, the inclusion of strategically placed implants can significantly control prosthesis movement (See Chapter 25, Figures 13-8 through 13-10).

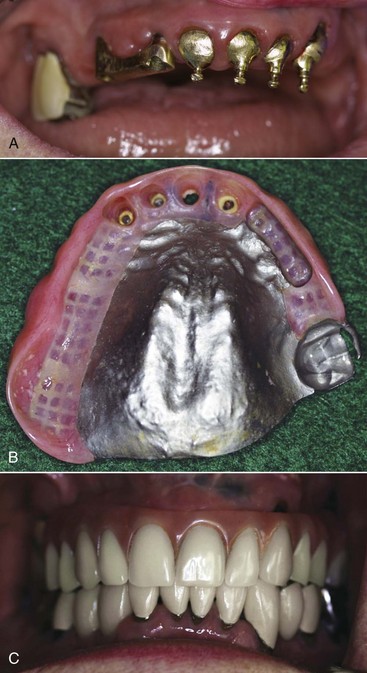

Figure 13-8 A, Implant bar and natural tooth copings used to support and retain this maxillary prosthesis. B, Tissue side of prosthesis showing the implant bar space, which when fitted will derive both support and stability from the implants while retention is gained through resilient O-rings on the natural tooth copings. C, Maxillary prosthesis seated and in occlusion.

(Courtesy Dr. N. Van Roekel, Monterey, CA.)

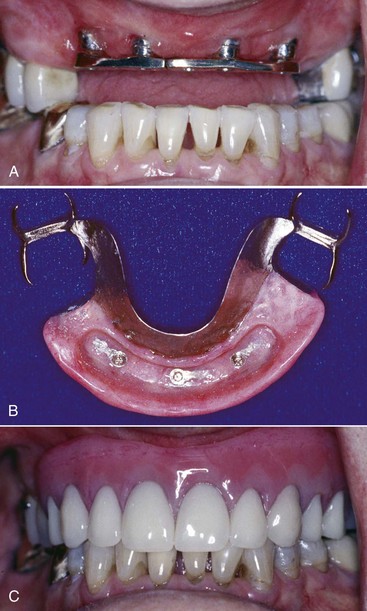

Figure 13-9 A, An anterior implant-supported bar demonstrating excellent access for hygiene and a parallel relationship to opposing occlusion. B, Prosthesis with implant bar space (housing three retentive male components for retention and a flat surface for bar contact and support) and bilateral posterior embrasure clasps. C, Prosthesis seated and in occlusion.

(Courtesy Dr. N. Van Roekel, Monterey, CA.)

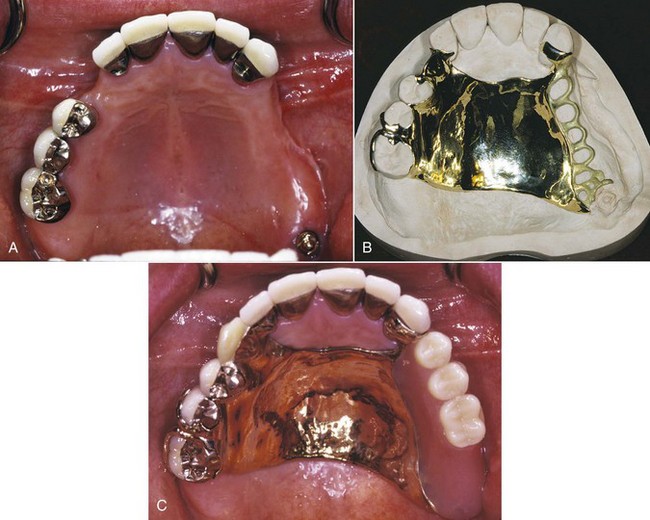

Figure 13-10 A, A Class II, modification 1 maxillary arch with a posterior implant at the distal location of the extension base. B, Maxillary gold framework with broad palatal coverage, maximum stabilization through palatal contacts of multiple maxillary teeth, and implant position at the distal extension base. A single implant should be protected from excessive occlusal forces; consequently the broad palatal coverage and maximum bracing are important features of the overall design. The ball attachment abutment was used for retentive purposes. C, Occlusal view of the prosthesis with implant (see A), which provides improved retention to the distal extension base.

(Courtesy Dr. James Taylor, Ottawa, Ontario.)

Augmentation of Alveolar Bone

Considerable attention has been devoted to ridge augmentation with the use of autogenous and alloplastic materials, especially in preparation for implant placement. Larger ridge volume gains necessitate consideration of autogenous grafts; however, these procedures are accompanied by concerns for surgical morbidity. Alloplastic materials have displayed short-term success; however, no randomized controlled trials have been conducted to provide evidence of long-term increases in ridge width and height for removable prostheses.

Clinical results depend on careful evaluation of the need for augmentation, the projected volume of required material, and the site and method of placement. Considerable emphasis must be placed on a sound clinical understanding that some of the alloplastic materials can migrate or be displaced under occlusal loads if not appropriately supported by underlying bone and contained by buttressing soft tissues. Careful clinical judgment with sound surgical and prosthetic principles must be exercised.

Conditioning of Abused and Irritated Tissues

Many removable partial denture patients require some conditioning of supporting tissues in edentulous areas before the final impression phase of treatment begins. Patients who require conditioning treatment often demonstrate the following symptoms:

Figure 13-11 A, Inflamed and distorted denture bearing mucosa due to an ill-fitting prosthesis that is worn 24 hours a day. B, After the tissue abuse is treated via modification of the denture base with a tissue conditioning resilient liner material, the prosthesis is removed for portions of the day, and the abused tissue is massaged, the denture bearing foundation is healthy again.

These conditions are usually associated with ill-fitting or poorly occluding removable partial dentures. However, nutritional deficiencies, endocrine imbalances, severe health problems (diabetes or blood dyscrasias), and bruxism must be considered in a differential diagnosis.

If the use of a new removable partial denture or the relining of a present denture is attempted without first correcting these conditions, the chances for successful treatment will be compromised because the same old problems will be perpetuated. The patient must be made to realize that fabrication of a new prosthesis should be delayed until the oral tissues can be returned to a healthy state. If there are unresolved systemic problems, removable partial denture treatment will usually result in failure or limited success.

The first treatment procedure should consist of immediate institution of a good home care program. A suggested home care program includes rinsing the mouth three times a day with a prescribed saline solution; massaging the residual ridge areas, palate, and tongue with a soft toothbrush; removing the prosthesis at night; and using a prescribed therapeutic multiple vitamin along with a prescribed high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet. Some inflammatory oral conditions caused by ill-fitting dentures can be resolved by removing the dentures for extended periods. However, few patients are willing to undergo such inconveniences.

Use of Tissue Conditioning Materials

The tissue conditioning materials are elastopolymers that continue to flow for an extended period, permitting distorted tissues to rebound and assume their normal form. These soft materials apparently have a massaging effect on irritated mucosa, and because they are soft, occlusal forces are probably more evenly distributed.

Maximum benefit from using tissue conditioning materials may be obtained by (1) eliminating deflective or interfering occlusal contacts of old dentures (by remounting in an articulator if necessary); (2) extending denture bases to proper form to enhance support, retention, and stability (Figure 13-12); (3) relieving the tissue side of denture bases sufficiently (2 mm) to provide space for even thickness and distribution of conditioning material; (4) applying the material in amounts sufficient to provide support and a cushioning effect (Figure 13-13); and (5) following the manufacturer’s directions for manipulation and placement of the conditioning material.

Figure 13-12 A, Mandibular removable partial denture with underextended bases, which contributed to tissue irritation. B, Denture bases properly extended to enhance support, stability, and retention.

Figure 13-13 Tissue conditioning should be of sufficient thickness to be resilient and not place undue stress on the soft tissue.

The conditioning procedure should be repeated until the supporting tissues display an undistorted and healthy appearance. Many dentists find that intervals of 4 to 7 days between changes of the conditioning material are clinically acceptable. Improvement in irritated and distorted tissues is usually noted within a few visits, and in some patients a dramatic improvement will be seen. Usually three or four changes of the conditioning material are adequate, but in some instances additional changes are required. If positive results are not seen within 3 to 4 weeks, one should suspect more serious health problems and request a consultation from a physician.

Periodontal Preparation*

Periodontal preparation of the mouth usually follows any oral surgical procedure and is performed simultaneously with tissue conditioning procedures. Ordinarily, tooth extraction and removal of impacted teeth and retained roots or fragments are accomplished before definitive periodontal therapy is provided. However, it is strongly recommended that a gross debridement be performed before tooth extraction when patients present with significant calculus accumulation. This helps limit the possibility of accidentally dislodging a piece of calculus into the extraction socket, which could lead to an infection. Elimination of exostoses, tori, hyperplastic tissue, muscle attachments, and frena, on the other hand, can be incorporated with periodontal surgical techniques. In any situation, periodontal therapy should be completed before restorative dentistry procedures are begun for any dental patient. This is particularly true when a removable partial denture is contemplated because the ultimate success of this restoration depends directly on the health and integrity of the supporting structures of the remaining teeth. The periodontal health of the remaining teeth, especially those to be used as abutments, must be evaluated carefully by the dentist and corrective measures instituted before a removable partial denture is fabricated. It has been demonstrated that following periodontal therapy and with a good recall and oral hygiene program, properly designed removable partial dentures will not adversely affect the progression of periodontal disease or carious lesions.

This discussion attempts to demonstrate how periodontal procedures affect diagnosis and treatment planning in a removable partial denture service rather than how the procedures are actually accomplished. For technical details, the reader is referred to any of several excellent textbooks on periodontics.

Objectives of Periodontal Therapy

The objective of periodontal therapy is the return to health of supporting structures of the teeth, creating an environment in which the periodontium may be maintained. The specific criteria for satisfying this objective are as follows:

Complete periodontal charting that includes the recording of pocket depths, assessment of attachment levels, and recording of furcation involvements, mucogingival problems, and tooth mobility should be performed. Determining the severity of periodontal disease should also include the use of appropriate radiographs. The dentist who is considering removable partial denture fabrication must be certain that these criteria have been satisfied before continuing with impression procedures for the master cast.

Periodontal Diagnosis and Treatment Planning

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of periodontal diseases is based on a systematic and carefully accomplished examination of the periodontium. It follows the procurement of the health history of the patient and is performed with direct vision, palpation, a periodontal probe, a mouth mirror, and other auxiliary aids, such as curved explorers, furcation probes, diagnostic casts, and appropriate radiographs.

In the examination procedure, nothing is as important as careful exploration of the gingival sulcus and recording of the probing pocket depth and sites that bleed on probing with a suitably designed periodontal probe. Under no circumstances should removable partial denture fabrication begin without an accurate appraisal of sulcus/pocket depth and health. The probe is positioned as close to parallel to the long axis of the tooth as possible and is inserted gently between the gingival margin and the tooth surface, and the depth of the sulcus/pocket is determined circumferentially around each tooth. At least six probing depth readings are recorded on the patient’s chart for each tooth. Usually depths are recorded for the distobuccal, buccal, mesiobuccal, distolingual, lingual, and mesiolingual aspects of each tooth. Sulcular health can also be assessed by the presence or absence of bleeding upon probing.

Dental radiographs can be used to supplement the clinical examination but should not be used as a substitute for it. A critical evaluation of the following factors should be made: (1) type, location, and severity of bone loss; (2) location, severity, and distribution of furcation involvements; (3) alterations of the periodontal ligament space; (4) alterations of the lamina dura; (5) the presence of calcified deposits; (6) the location and conformity of restorative margins; (7) evaluation of crown and root morphologies; (8) root proximity; (9) caries; and (10) evaluation of other associated anatomic features, such as the mandibular canal or sinus proximity. This information serves to substantiate the impression gained from the clinical examination.

Each tooth should be evaluated carefully for mobility. Unfortunately, there is no universally accepted standard for mobility. In general, mobility is graded according to the ease and extent of tooth movement. Normal mobility is in the order of 0.05 to 0.10 mm. Grade I mobility is present when less than 1 mm of movement occurs in a bucco-lingual direction; grade II is present when mobility in the bucco-lingual direction is between 1 and 2 mm; grade III is present when greater than 2 mm of mobility occurs in the bucco-lingual direction and/or the tooth is vertically depressible.

Tooth mobility is an indication of the condition of the supporting structures, namely, the periodontium, and usually is caused by inflammatory changes in the periodontal ligament, traumatic occlusion, loss of attachment, or a combination of the three factors. The degree of mobility present, coupled with a determination of the causative factors responsible, provides additional information that is invaluable in planning for the removable partial denture. If the causative factor can be removed, many grade I and grade II mobile teeth can become stable and may be used successfully to help support, stabilize, and retain the removable partial denture. Mobility in itself is not an indication for extraction unless the mobile tooth cannot aid in support or stability of the removable partial denture, or mobility cannot be reduced. (Grade III usually cannot be reversed and will not provide support or stability.)

Treatment Planning

Depending on the extent and severity of the periodontal changes present, a variety of therapeutic procedures ranging from simple to relatively complex may be indicated. As was the situation with the previously discussed oral surgical procedures, it is the responsibility of the dentist rendering the removable partial denture treatment to see that the required periodontal care is accomplished for the patient. Periodontal treatment planning can usually be divided into three phases. The first phase is considered disease control or initial therapy because the objective is to essentially eliminate or reduce local causative factors before any periodontal surgical procedures are accomplished. The procedures that are accomplished as part of the initial preparation phase include oral hygiene instruction, scaling, and root planing and polishing, as well as endodontics, occlusal adjustment, and temporary splinting, if indicated. In many instances, carefully performed scaling and root planing combined with excellent patient compliance may negate the need for periodontal surgery.

During the second, or periodontal, surgical phase, any needed periodontal surgery, such as free gingival grafts, osseous grafts, or pocket reduction, is accomplished. It is advisable to discuss the possible need for these treatment procedures with the patient at the initial examination appointment or during the initial phase of therapy, as this will likely involve referral of the patient to a periodontist. The maintenance of periodontal health is accomplished in phase 3 and is always ongoing. A definitive recall schedule should be established with the patient and is usually kept at 3- to 4-month intervals.

Initial Disease Control Therapy (Phase 1)

Oral Hygiene Instruction

Ordinarily, dental treatment should be introduced to the patient through instruction provided in a carefully devised oral hygiene regimen. The cooperation witnessed by the patient’s acceptance and compliance with the prescribed procedure, as evidenced by improved oral hygiene, will provide the dentist with a valuable means of evaluating that patient’s interest and the long-term prognosis of treatment.

For the oral hygiene routine to be successful, the patient must be convinced to follow the prescribed procedure regularly and conscientiously. The most effective motivation techniques require a good understanding by the patient of his/her periodontal condition. Only then can the benefits of routine treatment become evident. Hence, an explanation of dental/periodontal disease, including its causes, initiation, and progression, is an important component of oral hygiene instruction. After this discussion, the patient should be instructed on the use of disclosing wafers/tablets, a soft/medium-bristle toothbrush, and unwaxed/waxed dental floss. At subsequent appointments, oral hygiene can be evaluated carefully, and other oral hygiene aids such as an interdental and or sulcular brushes can be incorporated as needed. Further treatment should be withheld until a satisfactory level of plaque control has been achieved. This is a particularly critical point for the patient who requires extensive restorative dentistry or a removable partial denture. Without good oral hygiene, any dental procedure, regardless of how well it is performed, is ultimately doomed to failure. The informed dentist insists that acceptable oral hygiene is demonstrated and maintained before embarking on an extensive restorative dentistry treatment plan.

Scaling and Root Planing

One of the most important services rendered to the patient is the removal of calculus and plaque deposits from the coronal and root surfaces of the teeth. Careful scaling and root planing are fundamental to the reestablishment of periodontal health. Without meticulous removal of calculus, plaque, and toxic material in the cementum, other forms of periodontal therapy cannot be successful.

The use of ultrasonic instrumentation for calculus removal followed by root planing with sharp periodontal curettes is recommended. The curette is designed specifically for root planing and, when used correctly in combination with ultrasonic instrumentation, results in calculus removal and root surface decontamination. Thorough scaling and root planing should precede definitive surgical periodontal procedures that may be indicated before removable partial denture fabrication.

Elimination of Local Irritating Factors Other Than Calculus

Overhanging restoration margins and open contacts that allow food impaction should be corrected before definitive prosthetic treatment is begun. Although periodontal health predisposes to a much better environment for restorative procedures, it is not always possible or prudent to delay all restorative procedures until complete periodontal therapy and healing have occurred. This is especially true for patients with severe carious lesions in which pulpal involvement is likely. Excavation of these areas and placement of adequate restorations must be incorporated early in treatment. The placement of temporary or treatment fillings must not, in itself, become a local causative factor.

Elimination of Gross Occlusal Interferences

Bacterial plaque accumulations and calculus deposits are the primary factors involved in the initiation and progression of inflammatory periodontal disease. However, poor restorative dentistry can contribute to damage of the periodontium, and poor occlusal relationships may act as another factor that contributes to more rapid loss of periodontal attachment. Although occlusal interferences may be eliminated through a variety of techniques, at this stage of treatment, selective grinding is the procedure generally applied. Particular attention is directed to the occlusal relationships of mobile teeth. Traumatic cuspal interferences are removed by a selective grinding procedure. An attempt is made to establish a positive planned intercuspal position that coincides with centric relation. Deflective contacts in the centric path of closure are removed, eliminating mandibular displacement from the closing pattern. After this, the relationship of the teeth in various excursive movements of the mandible is observed, with special attention to cuspal contact, wear, mobility, and roentgenographic changes in the periodontium. The presence of working and nonworking interferences should be evaluated; if present, they should be removed.

The mere presence of occlusal abnormalities, in the absence of demonstrable pathologic change associated with the occlusion, does not necessarily constitute an indication for selective grinding. The indication for occlusal adjustment is based on the presence of a pathologic condition rather than on a preconceived articulation pattern. In the natural dentition, attempts to create bilateral balance, in the prosthetic sense, have no place in the occlusal adjustment procedure. Bilateral balanced occlusion not only is difficult to obtain in a natural dentition but also is apparently unnecessary in view of its absence in most normal healthy mouths. Occlusion on natural teeth needs to be perfected only to the point at which cuspal interference within the patient’s functional range of contact is eliminated and normal physiologic function can occur.

Guide to Occlusal Adjustment

Schuyler has provided the following guide to occlusal adjustment by selective grinding*:

In the study or evaluation of occlusal disharmony of the natural dentition, accurately mounted diagnostic casts are extremely helpful, if not essential, in determining static cusp-to-fossa contacts of opposing teeth and as a guide in the correction of occlusal anomalies in both centric and eccentric functional relations. Occlusion can be coordinated only by selective spot grinding. Ground tooth surfaces should be subsequently smoothed and polished.

Temporary Splinting

Teeth that are mobile at the time of the initial examination frequently present a diagnostic problem for the dentist. The cause of the mobility must be determined and then a decision made for elimination of the causative factors. The response of these teeth to temporary immobilization followed by appropriate treatment may be helpful in establishing a prognosis for them and may lead to a rational decision as to whether they should be retained or sacrificed. Secondary mobility resulting from the presence of an inflammatory lesion may be reversible if the disease process has not destroyed too much of the attachment apparatus. Primary mobility caused by occlusal interference also may disappear after selective grinding. In instances of angular types of osseous defects, one should consider guided tissue regeneration as a means of increasing attachment levels. In some situations, however, the teeth must be stabilized because of loss of supporting structure from the periodontal process.

Teeth may be immobilized during periodontal treatment by acid etching teeth with composite resin, with fiber-reinforced resins, with cast removable splints, or with intracoronal attachments. The latter, an example of which is the A-splint, necessitates cutting tooth surfaces and embedding a ridge connector between adjacent teeth.

After periodontal treatment is performed, splinting may be accomplished with cast removable restorations or cast cemented restorations. The preferred form of permanent splinting uses two or more cast restorations soldered or cast together. They may be cemented with permanent (zinc oxyphosphate or resin) cements or temporary (zinc oxide–eugenol) cements. A properly designed removable partial denture can also stabilize mobile teeth if provision for such immobilization is planned as the denture is designed.

Use of a Nightguard

The removable acrylic-resin splint, originally designed as an aid in eliminating the deleterious effects of nocturnal clenching and grinding, has been used to advantage for the removable partial denture patient. The nightguard may prove helpful as a form of temporary splinting if worn at night when the removable partial denture has been removed. The flat occlusal surface prevents intercuspation of the teeth, which eliminates lateral occlusal forces (Figure 13-14).

Figure 13-14 The removable acrylic-resin splint with a flat occlusal plane can be used effectively as a form of temporary stabilization and as a means of eliminating excessive lateral forces created by clenching and grinding habits.

The nightguard is particularly useful before fabrication of a removable partial denture when one of the abutment teeth has been unopposed for an extended period. The periodontal ligament of a tooth without an antagonist undergoes changes characterized by loss of orientation of periodontal ligament fibers, loss of supporting bone, and narrowing of the periodontal ligament space. If such a tooth is suddenly returned to full function when it is carrying an increased burden, pain and prolonged sensitivity may result. However if a nightguard is used to return some functional stimulation to the tooth, the periodontal ligament changes are reversed and an uneventful course can be experienced when the tooth is returned to full function.

Minor Tooth Movement

The increased use of orthodontic procedures in conjunction with restorative and prosthetic dentistry has contributed to the success of many restorations by altering the periodontal environment in which they are placed. Malposed teeth that were once doomed to extraction should be considered now for repositioning and retention. The additional stability provided for a removable partial denture by uprighting a tilted or drifted tooth may mean much in terms of comfort to the patient. The techniques employed are not difficult to master, and the rewards in terms of a better restorative dentistry service are great.

Definitive Periodontal Surgery (Phase 2)

Periodontal Surgery

After initial therapy is completed, the patient is reevaluated for the surgical phase. If oral hygiene is at an optimum level, yet pockets with inflammation and osseous defects are still present, a variety of periodontal surgical techniques should be considered to improve periodontal health. The procedures selected should have the potential to enhance the results obtained during Phase 1 therapy.

Pocket reduction or elimination may be achieved by root planing when the cause of pocket depth is edema caused by gingival inflammation. Apically positioned flap surgery or occasionally a gingivectomy may be considered for reduction of suprabony pockets. Osseous resection or regeneration using a flap approach is a form of surgical therapy that is commonly employed to help with treatment of the diseased periodontium. It must be noted that elimination of the inflammatory disease process and restoration of the periodontal attachment apparatus are the major objectives of periodontal therapy.

Periodontal Flaps

Today, use of one of the various flap procedures is the surgical approach that offers the greatest versatility. Periodontal flap surgery involves the elevation of either mucosa alone or both the mucosa and the periosteum. Although there are several indications for flap elevation, the most important goal of flap elevation is to allow access to the bone and the root surfaces for complete instrumentation. Other goals of the flap approach include access for pocket elimination, caries control, crown lengthening to allow for optimum restorative dental treatment, root amputation or hemisection, as required and access to the furcation of the tooth.

A decision is made before surgery is performed if the aim is resection of osseous tissue to allow for a more physiologic osseous anatomy and subsequently gingival contour, or to regenerate some of the lost periodontal attachment apparatus. However, sometimes changes have to be made during surgery based on the anatomy of defects following the removal of diseased granulation tissue. Osseous resection involves the use of both osteoplasty and ostectomy procedures. Osteoplasty refers to reshaping the bone without removing tooth-supporting bone; ostectomy includes the removal of tooth-supporting bone. Consequently, the flap is widely applied in the treatment of periodontal disease.

Guided Tissue Regeneration

Guided tissue regeneration (GTR) has been defined as those procedures that attempt regeneration of lost periodontal structures through differing tissue responses. The rationale for GTR is based on the physiologic healing response of the tissues after periodontal surgery. After periodontal surgery, a race to repopulate the root surface begins among the four tissue types of the periodontium, namely, epithelium, connective tissue, periodontal ligament (PDL), and bone. Epithelium, which migrates at a rate of 0.5 mm per day, typically migrates first along the root surface, preventing new attachment. Therefore to allow the undifferentiated mesenchymal cells from the PDL and the endosteum of bone to repopulate the root against surfaces, the epithelial cells and the gingival connective tissue cells should be isolated. This isolation during initial healing enables periodontal structures to become reestablished and may lead to better long-term health of the tooth. The GTR procedure commonly involves the use of an osseous graft along with a resorbable membrane (Figure 13-15). This technique has the potential to lead to substantial improvement of the periodontal condition when used around carefully selected two- and three-walled osseous defects and mandibular furcation involvements.

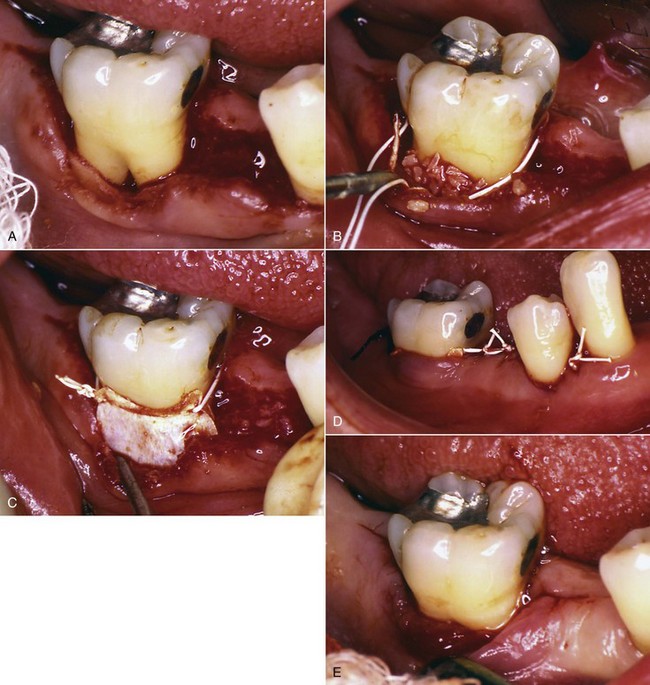

Figure 13-15 Guided tissue regeneration (GTR) procedure performed to address a furcation involvement. A, Tooth #30 presented with a grade 2 furcation involvement with the probe entering 3 mm in a horizontal direction. A GTR procedure using a combination of a bone graft and a nonresorbable membrane was planned. B, Following hand and ultrasonic instrumentation, decalcified freeze-dried bone allograft was grafted around the furcation. C, A nonresorbable membrane was placed over the bone graft. D, The flap was then sutured with a nonresorbable expanded polytetraethylene suture. E, Two months following surgery, the membrane was removed. Note the presence of red rubbery tissue filling the previously exposed furcation site. This tissue has the potential to form osseous tissue and close the access to the furcation entrance.

Periodontal Plastic Surgery

Periodontal plastic surgery, which was previously referred to as “mucogingival surgery,” is applied to those procedures used to resolve problems involving the interrelationship between the gingiva and the alveolar mucosa. Mucogingival surgery consists of plastic surgical procedures that are used for correction of gingiva–mucous membrane relationships that complicate periodontal disease and may interfere with the success of periodontal treatment. The objectives of periodontal plastic surgery are several and include elimination of pockets that transverse the mucogingival junction, creation of an adequate zone of attached gingiva, correction of gingival recession by root coverage techniques, relief of the pull of frena and muscle attachments on the gingival margin, and correction of deformities of edentulous ridges, done to permit access to the underlying alveolar process and correction of osseous deformities when there is sufficient or insufficient attached gingiva, to deepen a shallow vestibule, and to assist in orthodontic therapy. Commonly used periodontal plastic surgical procedures include lateral sliding flaps, free gingival grafts, pedicle grafts, coronally positioned grafts, double papilla flaps, semilunar coronally positioned flaps, subepithelial connective tissue grafts, and edentulous ridge augmentation using one of the above techniques. In addition, GTR has been used for periodontal plastic surgical procedures. Recently, use of the commercially available acellular dermal graft has gained popularity. However, the most commonly used procedure is the subepithelial connective tissue graft (Figure 13-16).

Figure 13-16 Gingival recession addressed with subepithelial connective tissue graft procedure. A, The patient presents with evidence of severe gingival recession associated with teeth #6, 7, and 8. This was an esthetic problem. The patient also complained of hypersensitivity associated with these teeth. A subepithelial connective tissue graft was planned to help correct the gingival recession. B, Clinical appearance 6 months following treatment with a subepithelial connective tissue graft on teeth #6, 7, and 8. The patient was very satisfied with the postoperative appearance, and clinically the symptom of hypersensitivity was no longer significant.

These plastic surgical procedures should be considered whenever an abutment tooth lacks adequate attached keratinized gingiva and requires root coverage to facilitate removable partial denture construction and maintenance.

Recall Maintenance (Phase 3)

Several longitudinal studies have now demonstrated the increasing importance of maintenance for all patients who have undergone any periodontal therapy. This includes not only reinforcement of plaque control measures but also thorough debridement of all root surfaces of supragingival and subgingival calculus and plaque by the dentist or an auxiliary.

The frequency of recall appointments should be customized for the patient, depending on the susceptibility and severity of periodontal disease. It is now understood that patients with a history of moderate to severe periodontitis should be placed on a 3- to 4-month recall system to maintain results achieved by nonsurgical and surgical therapy.

Advantages of Periodontal Therapy

Periodontal therapy done before a removable prosthesis is fabricated has several advantages. First, the elimination of periodontal disease removes a primary causative factor in tooth loss. The long-term success of dental treatment depends on the maintenance of the remaining oral structures, and periodontal health is mandatory if further loss is to be avoided. Second, a periodontium free of disease presents a much better environment for restorative correction. Elimination of periodontal pockets with the associated return of a physiologic architectural pattern establishes a normal gingival contour at a stable position on the tooth surface. Thus the optimum position for gingival margins of individual restorations can be established with accuracy. The coronal contours of these restorations can also be developed in correct relationships to the gingival margin, ensuring the proper degree of protection and functional stimulation to gingival tissues. Third, the response of strategic but questionable teeth to periodontal therapy provides an important opportunity for reevaluating their prognosis before the final decision is made to include (or exclude) them in the removable partial denture design. And last, the overall reaction of the patient to periodontal procedures provides the dentist with an excellent indication of the degree of cooperation to be expected in the future.

Even in the absence of periodontal disease, certain periodontal procedures may be an invaluable aid in removable partial denture construction. Through periodontal surgical techniques, the environment of potential abutment teeth may be altered to the point of making an otherwise unacceptable tooth a most satisfactory retainer for a removable partial denture.

Abutment Teeth Preparation

Abutment Restorations

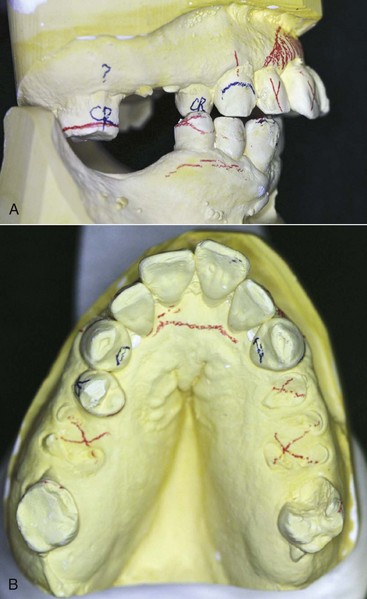

Equipped with the diagnostic casts on which a tentative removable partial denture design has been drawn, the dentist is able to accomplish preparation of abutment teeth with accuracy. The information at hand should include the proposed path of placement, the areas of teeth to be altered and tooth contours to be changed, and the locations of rest seats and guiding planes (see Figure 12-5).

During examination and subsequent treatment planning, in conjunction with a survey of diagnostic casts, each abutment tooth is considered individually as to what type of restoration is indicated. Abutment teeth presenting sound enamel surfaces in a mouth in which good oral hygiene habits are evident may be considered a fair risk for use as removable partial denture abutments. One should not be misled, however, by a patient’s promise to do better as far as oral hygiene habits are concerned. Good or bad oral hygiene is a habit of long standing and is not likely to be changed appreciably because a removable partial denture is being worn. Therefore one must be conservative in evaluating the oral hygiene habits of the patient in the future. Remember that clasps as such do not cause teeth to decay, and if the individual will keep the teeth and the removable partial denture clean, one need not condemn clasps from a cariogenic standpoint. On the other hand, more removable partial dentures have been condemned as cariogenic because the dentist did not provide for the protection of abutment teeth rather than because of inadequate care on the part of the patient.

Esthetic veneer types of crowns should be used when a canine or premolar abutment is to be restored or protected. Less frequently, the molar will have to be treated in such a manner, and except for maxillary first molars, the full cast crown is usually acceptable.

When there is proximal caries on abutment teeth with sound buccal and lingual enamel surfaces, in a mouth exhibiting average oral hygiene and low caries activity, a gold inlay may be indicated. However, silver amalgam or composite for the restoration of those teeth with proximal caries should not be condemned, although one must admit that an inlay cast of a hard type of gold will provide the best possible support for occlusal rests, at the same time giving an esthetically pleasing restoration. However, an amalgam restoration, properly condensed, is capable of supporting an occlusal rest without appreciable flow over a long period.

The most vulnerable area on the abutment tooth is the proximal gingival area, which lies beneath the minor connector of the removable partial denture framework and is therefore subject to accumulation of debris in an area most susceptible to caries. Even when the removable partial denture is removed, these areas are often missed by the toothbrush, which allows bacterial plaque and debris to remain for long periods. Because of this unique removable partial denture concern, special attention should be paid to these areas during patient education and follow-up. Even when a complete crown restoration is placed in this most vulnerable area, recurrent caries can occur. Caries risk is best managed through effective home care and professional follow-up procedures, rather than through the placement of restorations.

All proximal abutment surfaces that are to serve as guiding planes for the removable partial denture should be prepared so that they will be made as nearly parallel as possible to the path of placement. Preparations may include modifying the contour of existing ceramic restorations, if necessary. This may be accomplished with abrasive stones or diamond finishing stones. A polished surface for the altered ceramic restoration may be restored by using any of several polishing kits supplied by manufacturers.

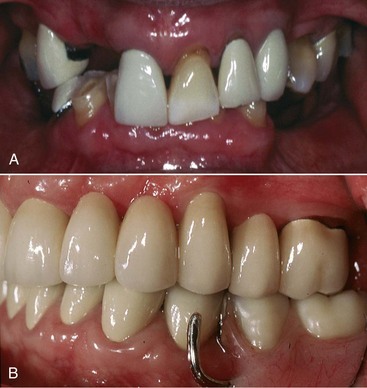

When preparing abutments that will receive surveyed crowns, it is important to plan for the tooth reduction necessary to allow placement of sufficient restorative material for durability, contour, and esthetics, as well as the contours prescribed for the desired clasp assembly (Figure 13-17). This can be accomplished by first modifying the axial contours of the abutments to those required of the completed crown, then starting controlled tooth reduction (preparation) to accommodate the thickness of the materials for durability, contour, and esthetics. This ensures that the wax patterns and resultant crowns can be restored to the desired form.

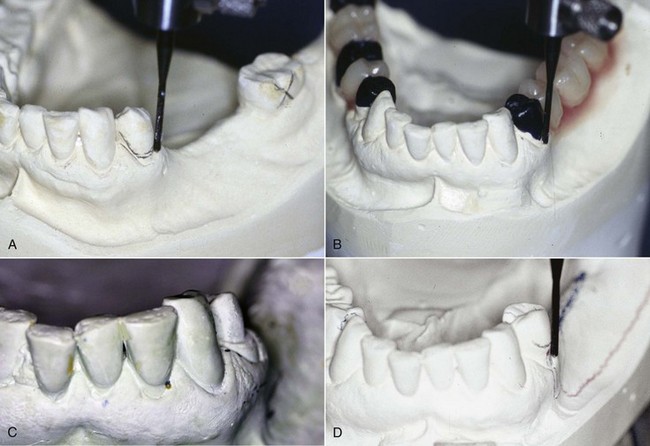

Figure 13-17 A, Diagnostic cast at an orientation best for all abutments considered. The buccal survey line is too close to the marginal gingival and the distal surface does not lend itself to guide-plane preparation. A surveyed crown is indicated. B, Abutment contours appropriate to clasp design (distal guide plane and mid-buccal 0.01 inch undercut) are produced in wax. C, Cast of abutment preparation provides buccal surface reduction adequate to replace with metal ceramic material at the required contour. Without careful consideration of survey line placement needs before and during preparation, it is easy to reproduce incorrect contours in finished crowns. D, Cast of a seated surveyed crown demonstrates desired contours for the clasp design chosen.

Contouring Wax Patterns

Modern indirect techniques permit the contouring of wax patterns on the master cast with the aid of the surveyor blade. All abutment teeth to be restored with castings can be prepared at one time and an impression made that will provide an accurate stone replica of the prepared arch. Wax patterns may then be refined on separated individual dies or removable dies. All abutment surfaces facing edentulous areas should be made parallel to the path of placement by the use of the surveyor blade (Figure 13-18). This technique will provide proximal surfaces that will be parallel without any further alteration in the mouth, will permit the most positive seating of the removable partial denture along the path of placement, and will provide the least amount of undesirable space beneath minor connectors for the lodgement of debris.

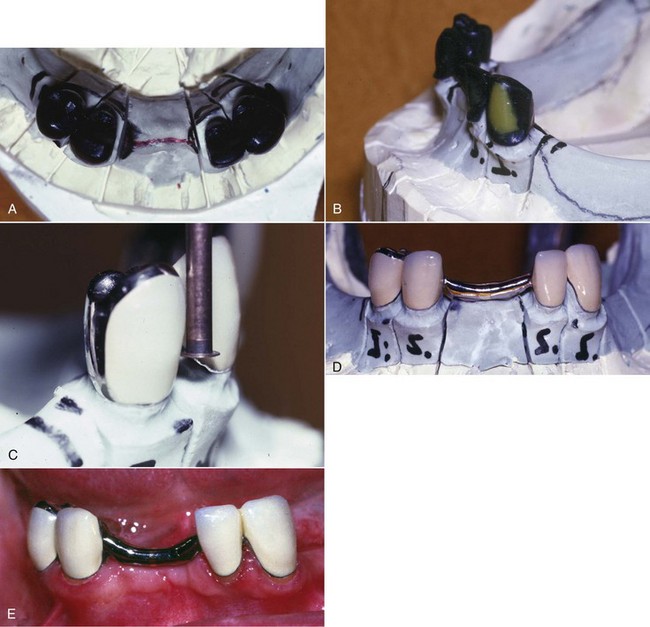

Figure 13-18 A, Occlusal view of full contour wax patterns, which will be splinted between crowns and across the midline with a 13-gauge splint bar. Rests are evident on the lingual surfaces of abutment wax patterns. B, Wax patterns showing labial cut-back for porcelain. Bilateral guide-plane surfaces will be reproduced in metal and are parallel to the path of insertion. C, An abutment veneered crown with an appropriate height of contour and a 0.02-inch undercut for the anticipated wrought-wire retainer. D, Completed prosthesis splinted between retainer crowns and across the midline. Splint bar with added vertical support provides indirect retention. E, Prosthesis inserted intraorally.

Rest Seats

After the proximal surfaces of the wax patterns have been made parallel, and buccal and lingual contours have been established to satisfy the requirements of stability and retention with the best possible esthetic placement of clasp arms, the occlusal rest seats should be prepared in the wax pattern rather than in the finished restoration. The placement of occlusal rests should be considered at the time the teeth are prepared to receive cast restorations, so there will be sufficient clearance beneath the floor of the occlusal rest seat. Too many times, a completed cast restoration is cemented in the mouth for a removable partial denture abutment without any provision for the occlusal rest having been made in the wax pattern. The dentist then proceeds to prepare an occlusal rest seat in the cast restoration, while ever conscious of the fact that he or she may perforate the casting during the process of forming the rest seat. The unfortunate result is usually a poorly formed rest seat that is too shallow.

If tooth structure has been removed to provide placement of the occlusal rest seat, it may be ideally placed in the wax pattern by using a No. 8 round bur to lower the marginal ridge and establish the outline form of the rest and then using a No. 6 round bur to slightly deepen the floor of the rest seat inside this lowered marginal ridge. This approach provides an occlusal rest that best satisfies the requirements that it be placed so that any occlusal force will be directed axially and that there will be the least possible interference to occlusion with the opposing teeth.

Perhaps the most important function of a rest is the division of stress loads from the removable partial denture to provide the greatest efficiency with the least damaging effect to the supporting abutment teeth. For a distal extension removable partial denture, the rest must be able to transmit occlusal forces to the abutment teeth in a vertical direction only, thereby permitting the least possible lateral stresses to be transmitted to the abutment teeth.

For this reason, the floor of the rest seat should incline toward the center of the tooth so that the occlusal forces, insofar as possible, are centered over the root apex. Any other form but that of a spoon shape can permit locking of the occlusal rest and the transmission of tipping forces to the abutment tooth. A ball-and-socket type of relationship between occlusal rest and abutment tooth is the most desirable. At the same time, the marginal ridge must be lowered so that the angle formed by the occlusal rest and the minor connector will stand above the occlusal surface of the abutment tooth as little as possible and avoid interference with the opposing teeth. Simultaneously, sufficient bulk must be provided to prevent weakness in the occlusal rest at the marginal ridge. The marginal ridge must be lowered and yet not be the deepest part of the rest preparation. To permit occlusal stresses to be directed toward the center of the abutment tooth, the angle formed by the floor of the occlusal rest with the minor connector should be less than 90 degrees. In other words, the floor of the occlusal rest should incline slightly from the lowered marginal ridge toward the center of the tooth.

This proper form can be readily accomplished in the wax pattern, if care is taken during crown or inlay preparation to provide the location of the rest. If direct restorations are used, sufficient bulk must be present in this area to allow proper occlusal rest seat form without weakening the restoration. There is insufficient evidence to show that direct restorations used as rest seats perform equally to enamel. When the rest seat is placed in sound enamel, this is best accomplished by the use of round carbide burs (No. 4, 6, and 8 sizes) that leave a smooth enamel surface.

Rest seat preparations in sound enamel (or in existing restorations that are not to be replaced) should always follow the recontouring of proximal tooth surfaces. The preparation of proximal tooth surfaces should be done first because if the occlusal portion of the rest seat is placed first and the proximal tooth surface is altered later, the outline form of the rest seat is sometimes irreparably altered.

Following proximal surface recontouring (guided plane preparation), the larger round bur is used to lower the marginal ridge 1.5 to 2.0 mm while at the same time creating the relative outline form of the rest seat. The result is a rest seat preparation with marginal ridge lowered and gross outline form established but without sufficient deepening of the rest seat preparation toward the center of the tooth. A smaller round bur (a No. 4 or 6) may then be used to deepen the floor of the rest seat to a gradual incline toward the center of the tooth. Enamel rods are then smoothed by the planing action of a round bur revolving with little pressure. Abrasive rubber points are sufficient to complete the polishing of the rest seat preparation.

The success or failure of a removable partial denture depends on how well the mouth preparations were accomplished. It is only through intelligent planning and competent execution of mouth preparations that the denture can satisfactorily restore lost dental functions and contribute to the health of the remaining oral tissues.