CHAPTER 20 Initial Placement, Adjustment, and Servicing of the Removable Partial Denture

Initial placement of the completed removable partial denture, the fifth of six essential phases of removable partial denture service mentioned in Chapter 2, should be a routinely scheduled appointment. All too often the prosthesis is quickly placed and the patient dismissed with instructions to return when soreness or discomfort develops. Patients should not be given possession of removable prostheses until denture bases have been initially adjusted as required, occlusal discrepancies have been eliminated, and patient education procedures have been continued.

Although it is true that some accommodation is a necessary part of adjusting to new dentures, many other factors are also pertinent. Among these are how well the patient has been informed of the mechanical and biological problems involved in the fabrication and wearing of a removable prosthetic restoration, and how much confidence the patient has acquired in the excellence of the finished product. Knowing in advance that every step has been carefully planned and executed with skill, and having acquired confidence in both the dentist and the excellence of the prosthesis, the patient is better able to accept the adjustment period as a necessary but transient step in learning to wear the prosthesis. This confidence could be lost if the dentist does not approach the insertion and postinsertion phases as equally important for the success of the treatment.

The term adjustment has two connotations, each of which must be considered separately. The first is adjustment of the denture bearing and occlusal surfaces of the denture made by the dentist at the time of initial placement and thereafter. The second is the adjustment or accommodation by the patient, both psychologically and biologically, to the new prosthesis.

After the resin bases have been processed and before dentures are separated from the casts, the occluding teeth must be altered to perfect the occlusal relationship between opposing artificial dentition or between artificial dentition and an opposing cast or template. Denture bases must be finished to eliminate excess and perfect the contours of polished surfaces for the best functional and esthetic results. This is made necessary by the inadequacies of casting procedures, because both the metal and resin parts of a prosthetic restoration are produced by casting methods. Unfortunately, such procedures in the laboratory rarely eliminate the need for final adjustment in the mouth to perfect the fit of the restoration to the oral tissue.

Included in this final step in a long sequence of finishing procedures necessary to produce a biologically acceptable prosthetic restoration are the following: (1) adjustment of the bearing surfaces of the denture bases to be in harmony with the supporting soft tissue; (2) adjustment of the occlusion to accommodate the occlusal rests and other metal parts of the denture; and (3) final adjustment of the occlusion on the artificial dentition to harmonize with natural occlusion in all mandibular positions.

Adjustments to Bearing Surfaces of Denture Bases

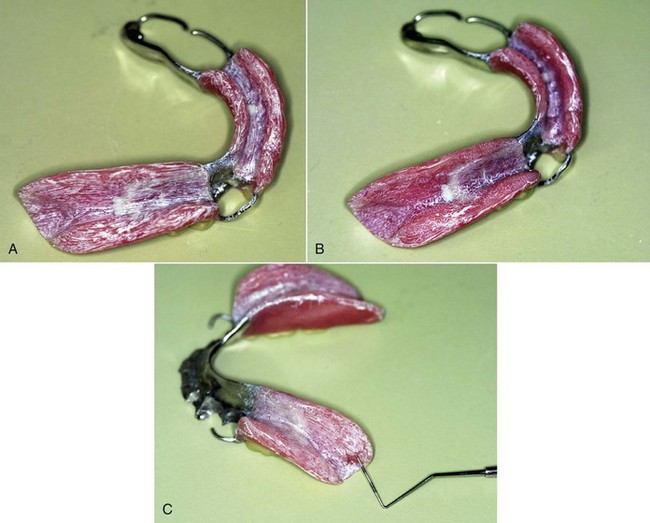

Altering bearing surfaces to perfect the fit of the denture to the supporting tissue should be accomplished with the use of some kind of indicator paste (Figure 20-1). The paste must be one that will be readily displaced by positive tissue contact and that will not adhere to the tissue of the mouth. Several pressure indicator pastes are commercially available. However, equal parts of a vegetable shortening and USP zinc oxide powder can be combined to make an acceptable paste. The components must be thoroughly spatulated to a homogeneous mixture. A quantity sufficient to fill several small ointment jars may be mixed at one time.

Figure 20-1 A, Tissue side of finished bases of a Kennedy Class I modification 1 removable partial denture, where pressure indicates that paste has been applied. Paste was applied following careful inspection of the tissue surface for irregularities or sharp projections, which must be eliminated before fitting in the mouth. The entire tissue surface of the bases was dried before it was coated with a thin coat of pressure indicator paste using a stiff-bristle brush. Brush marks are evident, and it is the change in the pattern of brush marks that guides adjustment. It is important to avoid thick application of indicator paste, which can hide the presence of significant pressure. B, The prosthesis can be dipped in cold water or sprayed with a provided release agent before placement in the patient’s mouth, to prevent paste from sticking to oral tissues. After careful seating of the denture, the patient can close firmly on cotton rolls for a few seconds, or the dentist can alternately apply a tissue-ward pressure over the bases to simulate functional movement. The presence of tissue contact is evident in the pattern of the paste, which is different from the brushed pattern. There is no suggestion of excessive pressure in this tissue contact pattern. However, it is not uncommon to relieve the area adjacent to the abutment sparingly. Several placements of the denture with indicator paste are usually necessary for evaluation of the accuracy of the bases. C, A different denture base recovered from the mouth after manipulation simulating function. The tissue contact reveals excessive pressure at the region lingual to the retromolar pad.

Rather than dismissing the patient with instructions to return when soreness develops and then overrelieving the denture for a traumatized area to restore patient comfort, use a pressure indicator paste with any tissue bearing prosthetic restoration. The paste should be applied by the dentist in a thin layer over the bearing surfaces. The material should be rinsed in water so it will not stick to the soft tissue, and then digital pressure should be applied to the denture in a tissue-ward direction. The patient cannot be expected to apply a heavy enough force to the new denture bases to register all of the pressure areas present. The dentist should apply both vertical and horizontal forces with the fingers in excess of what might be expected of the patient. The denture is then removed and inspected. Any areas where pressure has been heavy enough to displace a thin film of indicator paste should be relieved and the procedure repeated with a new film of indicator until excessive pressure areas have been eliminated. This is particularly difficult to interpret when patients exhibit xerostomia. An area of the denture base that shows through the film of indicator paste may be erroneously interpreted as a pressure spot, when actually the paste had adhered to the tissue in that area. Therefore only those areas that show through an intact film of indicator paste should be interpreted as pressure areas and relieved accordingly. The decision to relieve an area of pressure must consider whether the pressure is in a primary, secondary, or nonsupportive denture bearing area. The primary denture bearing areas should be expected to show greater contact than other areas.

Pressure areas most commonly encountered are as follows: in the mandibular arch—(1) the lingual slope of the mandibular ridge in the premolar area, (2) the mylohyoid ridge, (3) the border extension into the retromylohyoid space, and (4) the distobuccal border in the vicinity of the ascending ramus and the external oblique ridge; in the maxillary arch—(1) the inside of the buccal flange of the denture over the tuberosities, (2) the border of the denture lying at the malar prominence, and (3) the point at the pterygomaxillary notch where the denture may impinge on the pterygomandibular raphe or the pterygoid hamulus. In addition, bony spicules or irregularities in the denture base that will require specific relief may be found in either arch.

The amount of relief necessary will depend on the accuracy of the impression, the master cast, and the denture base. Despite the accuracy of modern impression and cast materials, many denture base materials leave much to be desired in this regard, and the element of technical error is always present. It is therefore essential that discrepancies in the denture base are detected and corrected before the tissues of the mouth are subjected to the stress of supporting a prosthetic restoration. One of our major responsibilities to the patient is that trauma should always be held to a minimum. Therefore the appointment time for initial placement of the denture must be adequate to permit such adjustment.

Occlusal Interference from Denture Framework

Any occlusal interference from occlusal rests and other parts of the denture framework should have been eliminated before or during the establishment of occlusal relations. The denture framework should have been tried in the mouth before a final jaw relation is established, and any such interference should have been detected and eliminated. Much of this need not occur if mouth preparations and the design of the removable partial denture framework are carried out with a specific treatment plan in mind. In any event, occlusal interference from the framework should not ordinarily require further adjustment at the time the finished denture is initially placed. For the dentist to have sent an impression or casts of the patient’s mouth to the laboratory and to receive a finished removable partial denture prosthesis without having tried the cast framework in the mouth is a dereliction of responsibility to the patient and the profession.

Adjustment of Occlusion in Harmony with Natural and Artificial Dentition

The final step in the adjustment of the removable partial denture at the time of initial placement is adjustment of the occlusion to harmonize with the natural occlusion in all mandibular excursions. When opposing removable partial dentures are placed concurrently, the adjustment of the occlusion will parallel to some extent the adjustment of occlusion on complete dentures. This is particularly true when the few remaining natural teeth are out of occlusion. But where one or more natural teeth may occlude in any mandibular position, those teeth will influence mandibular movement to some extent. It is necessary therefore that the artificial dentition on the removable partial denture be made to harmonize with whatever natural occlusion remains.

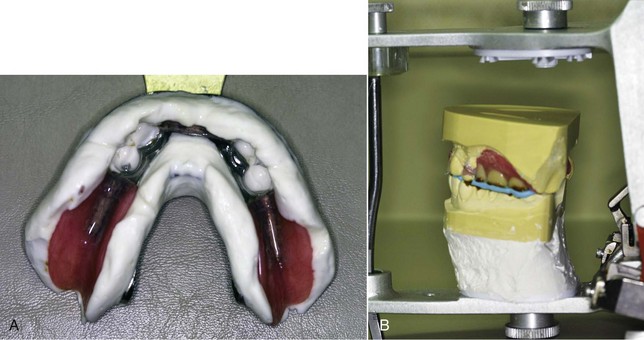

Occlusal adjustment of tooth-supported removable partial dentures may be performed accurately by any of several intraoral methods. Occlusal adjustment of distal extension removable partial dentures is accomplished more accurately with the use of an articulator than by any intraoral method. Because distal extension denture bases will exhibit some movement under a closing force, intraoral indications of occlusal discrepancies, whether produced by articulating paper or disclosing waxes, are difficult to interpret. Distal extension dentures positioned on remounting casts can conveniently be related in the articulator with new, nonpressure interocclusal records, and the occlusion can be adjusted accurately at the appointment for initial placement of the dentures (Figure 20-2).

Figure 20-2 Sequence of laboratory and clinical procedures performed for correction of occlusal discrepancies caused by processing of removable partial dentures. The arch with the prosthesis will require a new cast and record to provide occlusal correction. If it is a maxillary prosthesis, this involves preserving the facebow record by replacing the processed maxillary removable partial denture and cast on the articulator and indexing the occlusal surfaces using a remount jig, or making another facebow record at the try-in appointment. If it is a mandibular prosthesis, the opposing arch can be prepared before insertion. A, In this example, the opposing arch is a complete denture that is not to be altered. To produce a cast for use in correcting the occlusion on the articulator, a pick-up impression of the mandibular prosthesis is made. The prosthesis stays within the irreversible hydrocolloid impression; the clasps, proximal plates, and any undercut or parallel surface are carefully blocked out with wax before the remount cast is formed. B, The remount cast that is formed is then inverted and positioned with the use of an interocclusal record. C, The mounted mandibular cast and the interocclusal record showing that the record was made without tooth contact. This allows the position recorded to not be influenced by the teeth, which could alter the closure path and introduce error. D, This example shows a maxillary complete denture that was mounted before the patient visit with the use of a remount index (preserved facebow by indexing before recovery from the processed cast) and the mandibular remount cast and interocclusal record (as in C). The record is removed and occlusal correction accomplished to control the postprocess occlusion. Use of the completed prostheses provides the best chance to obtain an accurate and reliable interocclusal record, given the fact that the bases are very accurate and stable. E, The goal of the remounting procedure is to provide the occlusal position prescribed by the arrangement of prosthesis teeth. It would be inappropriate to allow the patient to attempt to accommodate to a new prosthesis in which the occlusion is not optimized.

The methods by which occlusal relations may be established and recorded have been discussed in Chapter 17. In this chapter, the advantages of establishing a functional occlusal relationship with an intact opposing arch have been discussed, along with the limitations that exist to perfecting harmonious occlusion on the finished prosthesis by intraoral adjustment alone. Even when the occlusion on two opposing removable partial dentures is adjusted, it is best that one arch be considered an intact arch and the other one adjusted to it. This is accomplished by first eliminating any occlusal interference with mandibular movement imposed by one denture and adjusting any opposing natural dentition to accommodate the prosthetically supplied teeth. Then the opposing removable partial denture is placed, and occlusal adjustments are made to harmonize with both the natural dentition and the opposing denture, which is now considered part of an intact dental arch. Which removable partial denture is adjusted first, and which is made to occlude with it is somewhat arbitrary, with the following exceptions: If one removable partial denture is entirely tooth supported and the other has a tissue-supported base, the tooth-supported denture is adjusted to final occlusion with any opposing natural teeth. That arch is then treated as an intact arch and the opposing denture adjusted to occlude with it. If both removable partial dentures are entirely tooth supported, the one that occludes with the most natural teeth is adjusted first and the second denture is then adjusted to occlude with an intact arch. Tooth-supported segments of a tooth and tissue–supported removable partial denture are likewise adjusted first to harmonize with any opposing natural dentition. The final adjustment of occlusion on opposing tissue-supported bases is usually done on the mandibular removable partial denture because this is the moving member, and the occlusion is made to harmonize with the maxillary removable partial denture, which is treated as part of an intact arch.

Intraoral occlusal adjustment is accomplished with the use of some kind of indicator and suitable mounted points and burs. Diamond or other abrasive points must be used to reduce enamel, porcelain, and metal contacts. These also may be used to reduce plastic tooth surfaces, but burs may be used for plastic with greater effectiveness. Articulation paper may be used as an indicator if one recognizes that heavy interocclusal contacts may become perforated, leaving only a light mark. Secondary contacts, which are lighter and frequently sliding, may make a heavier mark. Although articulation ribbon does not become perforated, it is not easy to use in the mouth, and differentiation between primary and secondary contacts is difficult, if not impossible, to ascertain.

In general, occlusal adjustment of multiple contacts between natural and artificial dentition when tooth-supported removable partial dentures are involved follows the same principles as those for natural dentition alone. This is because removable partial dentures are retained by devices attached to the abutment teeth, whereas no mechanical retainers are present with complete dentures. The use of more than one color of articulation paper or ribbon to record and differentiate between centric and eccentric contacts is just as helpful in adjusting removable partial denture occlusion as natural occlusion, and this method may be used for the initial adjustment.

For final adjustment, because one denture will be adjusted to occlude with a predetermined arch, the use of an occlusal wax may be necessary to establish points of excessive contact and interference. This cannot be done by articulation paper alone. An occlusal indicating wax (Figure 20-3) that is adhesive on one side, or strips of 28-gauge casting wax or other similar soft wax, may be used. This should always be done bilaterally, with two strips folded together at the midline. Thus the patient is not as likely to deviate to one side as when wax is introduced unilaterally.

For centric contacts, the patient is guided to tap into the wax. Then the wax is removed and inspected for perforations under transillumination. Premature contacts or excessive contacts appear as perforated areas and must be adjusted. One of two methods may be used to locate specific areas to be relieved. Articulation ribbon may be used to mark the occlusion; then those marks that represent areas of excessive contact are identified by referring to the wax record and are relieved accordingly. A second method is to introduce the wax strips a second time, this time adapting them to the buccal and lingual surfaces for retention. After the patient has tapped into the wax, perforated areas are marked with a waterproof pencil. The wax is then stripped off and the penciled areas are relieved.

Whichever method is used, it must be repeated until occlusal balance in the planned intercuspal position has been established and uniform contacts without perforations are evident from a final interocclusal wax record. After adjustment has been completed, any remaining areas of interference are reduced, thus ensuring that there is no interference during the chewing stroke. Adjustments to relieve interference during the chewing stroke should be confined to buccal surfaces of mandibular teeth and lingual surfaces of maxillary teeth. This serves to narrow the cusps so that they will go all the way into the opposing sulci without wedging as they travel into the planned intercuspal contact. Skinner proposed giving a small bite of soft banana to chew rather than expecting the patient to chew without food actually being present. The small bolus of banana promotes normal functional activity of the chewing mechanism, yet by its soft consistency does not in itself cause indentations in the soft wax. Any interfering contacts encountered during the chewing stroke are thus detected as perforations in the wax, which are marked with pencil and relieved accordingly.

After adjustment of the occlusion, the anatomy of the artificial teeth should be restored to maximal efficiency by restoring grooves and spillways (food escapeways) and by narrowing the teeth bucco-lingually to increase the sharpness of the cusps and reduce the width of the food table. Mandibular buccal and maxillary lingual surfaces in particular should be narrowed to ensure that these areas will not interfere with closure into the opposing sulci, because artificial teeth used on removable partial dentures that oppose natural or restored dentition should always be considered material out of which a harmonious occlusal surface is created. Final adjustment of the occlusion should always be followed by meticulous restoration of the most functional occlusal anatomy possible. Although this may be done after a subsequent occlusal adjustment is made at a later date, the possibility that the patient may fail to return on schedule is always present; in the meantime, broad and inefficient occlusal surfaces may cause overloading of the supporting structures, which would be traumatogenic. Therefore restoration of an efficient occlusal anatomy is an essential part of the denture adjustment at the time of placement. Again, this necessitates that sufficient time is allotted for initial placement of the removable partial denture to permit accomplishment of all necessary occlusal corrections.

Adjustments to occlusion should be repeated at a reasonable interval after the dentures have reached a point of equilibrium and the musculature has become adjusted to the changes brought about by restoration of occlusal contacts. This second occlusal adjustment usually may be considered sufficient until such time as tissue-supported denture bases no longer support the occlusion, and corrective measures—either reoccluding the teeth or relining the denture—must be used. However, a periodic recheck of occlusion at intervals of 6 months is advisable to prevent traumatic interference resulting from changes in denture support or tooth migration.

Instructions to the Patient

Finally, before the patient is dismissed, he or she should be reminded of the chronic nature of the missing tooth condition and of the fact that treatment solutions, such as a removable partial denture (RPD), require monitoring to ensure that they continue to provide optimum function without harming the mouth.

Patients should be instructed in the proper placement and removal of the removable partial denture. They should demonstrate that they can place and remove the prosthesis themselves. Clasp breakage can be avoided by instructing patients to remove the removable partial denture by the bases and not by repeated lifting of the clasp arms away from the teeth with the fingernails.

Patients should be advised that some discomfort or minor annoyance might be experienced initially. To some extent, this may be caused by the bulk of the prosthesis to which the tongue must become accustomed.

Patients must be advised of the possibility of the development of soreness despite every attempt on the part of the dentist to prevent its occurrence. Because patients vary widely in their ability to tolerate discomfort, it is best to advise every patient that needed adjustments will be made. On the other hand, the dentist should be aware that some patients are unable to accommodate the presence of a removable prosthesis. Fortunately, these are few in any practice. However, the dentist must avoid any statements that might be interpreted or construed by the patient to be positive assurance tantamount to a guarantee that the patient will be able to use the prosthesis with comfort and acceptance. Too much depends on the patient’s ability to accept a foreign object and to tolerate reasonable pressure to make such assurance possible.

Discussing phonetics with the patient in regard to the new dentures may indicate that this is a unique problem to be overcome because of the influence of the prosthesis on speech. With few exceptions, which usually result from excessive and preventable bulk in the denture design, contour of denture bases, or improper placement of teeth, the average patient will experience little difficulty in wearing the removable partial denture. Most hindrances to normal speech will disappear in a few days.

Similarly, perhaps little or nothing should be said to the patient about the possibility of gagging or the tongue’s reaction to a foreign object. Most patients will experience little or no difficulty in this regard, and the tongue will normally accept smooth, nonbulky contours without objection. Contours that are too thick, too bulky, or improperly placed should be avoided in the construction of the denture, but if present, these should be detected and eliminated at the time of placement of the denture. The dentist should palpate the prosthesis in the mouth and reduce excessive bulk accordingly before the patient has an opportunity to object to it. The area that most often needs thinning is the distolingual flange of the mandibular denture. Here the denture flange should always be thinned during finishing and polishing of the denture base. Sublingually, the denture flange should be reproduced as recorded in the impression, but distal to the second molar the flange should be trimmed somewhat thinner. Then, when the denture is placed, the dentist should palpate this area to ascertain that a minimum of bulk exists that might be encountered by the side and base of the tongue. If this needs further reduction, it should be done and the denture repolished before the patient is dismissed.

The patient should be advised of the need to keep the dentures and the abutment teeth meticulously clean. If cariogenic processes are to be prevented, the accumulation of debris should be avoided as much as possible, particularly around abutment teeth and beneath minor connectors. Furthermore, inflammation of gingival tissue is prevented by removing accumulated debris and substituting toothbrush massage for the normal stimulation of tongue and food contact with areas that will be covered by the denture framework.

The mouth and the removable partial denture should be cleaned after eating and before retiring. Brushing before breakfast also may be effective in reducing the bacterial count, which may help to lessen acid formation after eating in the caries-susceptible individual. A removable partial denture may be effectively cleaned with the use of a small, soft-bristle brush. Debris may be effectively removed through the use of nonabrasive dentifrices, because they contain the essential elements for cleaning. Household cleaners and toothpastes should not be used, because they are too abrasive for use on acrylic-resin surfaces. The patient—the elderly or handicapped patient in particular—should be advised to clean the denture over a basin partially filled with water so that denture impact will be less if the denture is dropped accidentally during cleaning.

Along with brushing with a dentifrice, additional cleaning may be accomplished with the use of a proprietary denture cleaning solution. The patient should be advised to soak the dentures in the solution for 15 minutes once daily, followed by thorough brushing with a dentifrice. Although hypochlorite solutions are effective denture cleansers, they have a tendency to tarnish chromium-cobalt frameworks and should be avoided.

In some mouths, the precipitation of salivary calculus on the removable partial denture necessitates taking extra measures for its removal. Thorough daily brushing of the denture will prevent deposits of calculus for many patients. However, any buildup of calculus noted by the patient between scheduled recall appointments should be removed in the dental office. This can be quickly and readily accomplished with an ultrasonic cleaner.

Because many patients may dine away from home, the informed patient should provide some means of carrying out midday oral hygiene. Simply rinsing the removable partial denture and the mouth with water after eating is beneficial if brushing is not possible.

Opinion is divided on the question of whether or not a removable partial denture should be worn during sleep. Conditions should determine the advice given the patient, although generally the tissue should be allowed to rest by removal of the denture at night. The denture should be placed in a container and covered with water to prevent its dehydration and subsequent dimensional change. About the only situation that possibly justifies wearing removable partial dentures at night is when stresses generated by bruxism would be more destructive because they would be concentrated on fewer teeth. Broader distribution of the stress load, plus the splinting effect of the removable partial denture, may make wearing the denture at night advisable. However, an individual mouth protector should be worn at night until the cause of the bruxism is eliminated.

Often the question arises whether an opposing complete denture should be worn when a removable partial denture in the other arch is out of the mouth. The answer is that if the removable partial denture is to be removed at night, the opposing complete denture should not be left in the mouth. There is no more certain way of destroying the alveolar ridge, which supports a maxillary complete denture, than to have it occlude with a few remaining anterior mandibular teeth.

The patient with a removable partial denture should not be dismissed as completed without at least one subsequent appointment for evaluation of the response of oral structures to the restorations and minor adjustment if needed. This should be made at an interval of 24 hours after initial placement of the denture. It need not be a lengthy appointment but should be made as a definite rather than a drop-in appointment. This not only gives the patient assurance that any necessary adjustments will be made and provides the dentist with an opportunity to check on the patient’s acceptance of the prosthesis but also avoids giving the patient any idea that the dentist’s schedule may be interrupted at will and serves to give notice that an appointment is necessary for future adjustments.

Follow-Up Services

The patient must understand the sixth and final phase of removable partial denture service (periodic recall) and its rationale. Patients need to understand that the support for a prosthesis (Kennedy Class I and II) may change with time. Patients may experience only limited success with the treatment and prostheses so meticulously accomplished by the dentist, unless they return for periodic oral evaluations.

After all necessary adjustments have been made to the removable partial denture and the patient has been instructed on proper care of the denture, the patient must also be advised as to future care of the mouth to ensure health and longevity of the remaining structures. How often the dentist should examine the mouth and the denture depends on the oral and physical condition of the patient. Patients who are caries susceptible or who have tendencies toward periodontal disease or alveolar atrophy should be examined more often. Every 6 months should be the rule if conditions are normal.

The need to increase retention on clasp arms to make the denture more secure will depend on the type of clasp that has been used. Increasing retention should be accomplished by contouring the clasp arm to engage a deeper part of the retentive undercut rather than by forcing the clasp in toward the tooth. The latter creates only frictional retention, which violates the principle of clasp retention. As an active force, such retention contributes to tooth or restoration movement, or both, in a horizontal direction, disappearing only when the tooth has been moved or the clasp arm has returned to a passive relationship with the abutment tooth. Unfortunately, this is almost the only adjustment that can be made to a half-round cast clasp arm. On the other hand, the round wrought-wire clasp arm may be cervically adjusted and brought into a deeper part of the retentive undercut. Thus the passivity of the clasp arm in its terminal position is maintained but retention is increased, because it is forced to flex more to withdraw from the deeper undercut. The patient should be advised that the abutment tooth and the clasp will serve longer if the retention is held minimally, which is only that amount necessary to resist reasonable dislodging forces.

The future development of denture rocking or looseness may be the result of a change in the form of the supporting ridges rather than lack of retention. This should be detected as early as possible after it occurs and corrected by relining or rebasing. The loss of tissue support is usually so gradual that the patient may be unable to detect the need for relining. This usually must be determined by the dentist at subsequent examinations as evidenced by rotation of the distal extension denture about the fulcrum line. If the removable partial denture is opposed by natural dentition, the loss of base support causes loss of occlusal contact, which may be detected by having the patient close on wax or Mylar strips placed bilaterally. If, however, a complete denture or a distal extension removable partial denture opposes the removable partial denture, the interocclusal wax test is not dependable because posterior closure, changes in the temporomandibular joint, or migration of the opposing denture may have maintained occlusal contact. In such cases, evidence of loss of ridge support is determined solely by the indirect retainer leaving its seat as the distal extension denture rotates about the fulcrum.

No assurance can be given to the patient that crowned or uncrowned abutment teeth will not decay at some future time. The patient can be assured, however, that prophylactic measures in the form of meticulous oral hygiene, coupled with routine care by the dentist, will be rewarded by greater health and longevity of the remaining teeth.

The patient should be advised that maximal service may be expected from the removable partial denture if the following rules are observed: