CHAPTER 2 Considerations for Managing Partial Tooth Loss

Tooth Replacements From the Patient Perspective

Points of View

Do we treat or do we manage tooth loss? Is the distinction important as we attempt to help our patients decide which type of prosthesis to choose? For patients who want to know what to expect now and in the future, it is helpful to make this distinction, as it helps them realize that the decision has implications for future needs that may be different between prostheses.

Tooth Replacements From the Patient’s Perspective

Tooth loss is a permanent condition in that the natural order has been disrupted, and in this sense it is much like a chronic medical condition. Like hypertension and diabetes, two medical conditions that are not reversible and that require medical management to monitor care to ensure appropriate response over time, tooth replacement prostheses must be managed to ensure appropriate response over time.

The term management suggests a focus on meeting needs that may change over time. These needs may be expected or unexpected. Expected outcomes are those that accompany the common clinical course for a type of prosthesis that is related to the tooth-tissue response. This biological toll response is heavily influenced by the type of prosthesis chosen. In addition, various needs due to prosthesis degradation and related to expected time-to-retreatment concerns of life expectancy are seen. Unexpected needs are those that might involve factors related to our control of manipulations (such as tissue damage or abuse, material design flaws, or prosthesis design) or to those out of our control (such as parafunction or accidental trauma).

With this in mind, it is helpful to consider how we approach educating our patients about management of missing teeth. Most often, a typical sequence is used to discuss tooth replacement options with patients: dental implant–supported prostheses, fixed prostheses, and, finally, removable partial dentures. When removable partial dentures are suggested, they are seldom described in the detail in which fixed or implant prostheses are described, as they generally are considered less like teeth and not as desirable a replacement. The desirability of a prosthesis is important to consider, and because removable partial dentures (RPDs) are less like teeth than other replacements, it is important to recognize what this suggests from the patient’s perspective.

Patients’ experiences have involved natural teeth, and their expectations of replacements would best be described within this context. The order with which we provide replacement prosthesis options for consideration is likely developed on the basis of numerous factors, including the following: we may believe we know what’s best for patients, our practice style may not include removable options, we may not have had good experience with removable prostheses and this lessens our confidence in their use, or RPDs do not match our practice resources.

Although these are important factors, the reason to include RPDs in the discussion is related to identifying whether such a prosthesis is viable, and, if so, whether it is the best option for the patient. We discover this only by interacting with our patients regarding their expectations and understanding their capacity to benefit from options of management that have trade-offs unique to each type of prosthesis.

Shared Decision Making

When patients are given information regarding their oral health status, which includes disease and functional deficits, as well as the means to address both, what do they need to hear? To achieve a state of oral health, they need to recognize behavioral issues related to plaque control, so that once active disease is controlled, they have an understanding that best ensures future health. For tooth replacement decisions, complex trade-offs in care choice are often required. The “shared decision making” approach addresses the need to fully inform patients about risks and benefits of care, and ensures that the patient’s values and preferences play a prominent role in the ultimate decision.

It is recognized that patients vary in their desire to participate in such decisions, thus our active inquiry is required to engage them in discussion. This becomes especially important when elective care, which involves potentially high-burden, costly options with highly variable maintenance requirements, is considered.

When patients wish to participate, it is our responsibility to provide them with specific and sufficient information that they can use to decide between treatment options. Specific information ideally comes from our own practice outcomes, in that such information provides effectiveness information and is provider specific. Sufficient information describes exactly what aspects of care are important to the overall decision. Ultimately, it is our role to help patients consider important differences between different prosthesis types.

What then defines important differences? Multiple outcomes combine to describe the overall impact of prosthetic care for all patients. These include technical outcomes, physical outcomes, esthetic outcomes, various maintenance needs, initial and future costs, and even physiologic outcomes that suggest to what extent prostheses “feel” like teeth.

When tooth replacement prostheses are considered from a patient’s perspective, it can be seen that the desire is to replace teeth that serve functional and social roles in everyday life. In considering how well various types of prostheses may meet patients’ specific needs, it is helpful to note what features of the original dentition—the gold standard, in this instance—we strive to duplicate in the replacement. Although it is common to find that existing oral conditions do not easily allow complete restoration to the state of a fully dentate patient, considering the respective strengths and weaknesses of the prosthodontic options (compared with this “gold standard”) helps in identification of realistic expectations.

In this text, the focus will be on a type of replacement prosthesis for patients with some, but not all, missing teeth. The replacement prosthesis ideally should provide function and a level of comfort as equivalent as possible to normal dentition. In achieving this, stability while chewing is a primary focus of attention, and we should strive to determine what is required to ensure it. If the prosthesis will be visible during casual speaking, smiling, and/or laughing, it is obvious that the replacement should look as natural as the surrounding environment. In summary, tooth replacement prostheses should provide a combination of several features of natural teeth: socially acceptable in appearance, comfortable and stable in function, and maintainable throughout their serviceable lifetime at a reasonable cost.

Tooth-Supported Prostheses

For partially edentulous patients, available prosthetic options include natural tooth–supported fixed partial dentures, removable partial dentures, and implant-supported fixed partial dentures. How well these options restore and maintain the features of natural teeth mentioned previously depends to a large extent on the numbers and locations of the missing teeth. The major categories of partial tooth loss (see Chapter 3) are those (1) with teeth both anterior and posterior to the space (a tooth-supported space), and (2) with teeth either anterior or posterior to the space (a tooth- and tissue-supported space). All prosthetic options listed are available for the tooth-bound space (although they are not necessarily indicated for every clinical situation), but only removable partial dentures and implant-supported prostheses are available for the distal extension (recognizing limited application of cantilevers).

Removable partial dentures can be designed in various ways to allow use of abutment teeth and supporting tissue for stability, support, and retention of the prosthesis. In terms of tooth-bound spaces, the removable partial denture is like a fixed partial denture because natural teeth alone provide direct resistance to functional forces. Because natural teeth support the prosthesis, it should not move under these functional forces. In this condition, the interface between, or relationship of, the removable partial denture framework and the abutment teeth should be designed to take advantage of tooth support—similar to the relationship between a fixed partial denture retainer and a prepared tooth. This means that it should provide positive vertical support (rest preparations) and a restrictive angle of dislodgment (opposing guide planes). Put another way, when the removable partial denture is selected for a tooth-bound situation, stability under functional load should be as well controlled as a fixed partial denture when appropriate tooth preparation is provided. Because removable partial denture clasps do not completely encircle the tooth, as a fixed partial denture retainer does, they must be designed to engage more than half the circumference to allow the prosthesis to maintain position under the influence of horizontal chewing loads. It should be obvious that careful planning and execution of the necessary natural tooth contour modifications are required to ensure movement control and functional stability for removable partial dentures supported by teeth. Similarities between the prosthesis-tooth interface for fixed partial dentures and for removable partial dentures are highlighted to emphasize the modification principles required to ensure stability for movement control in removable partial dentures. Over time, natural tooth support can be maintained as with the fixed partial denture. Chapter 14 helps to explain how this is accomplished when natural tooth modifications or surveyed crowns are produced.

Tooth and Tissue–Supported Prostheses

For removable partial dentures that do not have the benefit of natural tooth support at each end of the replacement teeth (extension base removable partial dentures), it is necessary that the residual ridge be used to assist in the functional stability of the prosthesis. When a removable partial denture is selected for a tooth-tissue–supported arch, the prosthesis must be designed to allow functional movement of the base to the extent expected by the residual ridge mucosa. This mucosa movement is variable, but for healthy residual ridge (masticatory) mucosa, movement from 1 to 3 mm can be expected. Consequently, unlike with the tooth-bound space, tooth modification for the tooth-tissue–supported prosthesis must be designed with the dual goal of framework tooth contact to allow appropriate functional stability from the tooth, but with allowance for the anticipated vertical and/or horizontal movement of the extension base. This introduces the concept of anticipated movement with a prosthesis and the requirement that we have a role in designing prostheses to appropriately control movement. Additionally, because tissue support in the tooth-tissue removable partial denture predictably changes over time, to adequately manage partial tooth loss with a removable prosthesis, we must carefully monitor our patients to maintain support and ensure maximum prosthetic function.

The clasp-retained partial denture, with extracoronal direct retainers, is used significantly more frequently than the precision attachment partial denture (Figure 2-1). It is capable of providing physiologically sound treatment for most patients who need partial denture restorations. Although the clasp-retained partial denture has disadvantages, its advantages of lower cost and shorter fabrication time ensure that it will continue to be widely used. Following are some possible disadvantages of a clasp-retained partial denture:

Figure 2-1 A, Maxillary and mandibular clasp-retained removable partial dentures. All clasps are extracoronal retainers (clasps) on abutments. B, Prostheses from (A) shown intraorally in occlusion. C, Maxillary prosthesis using intracoronal retainers and full palatal coverage. The male portions of the attachments are shown at the mesial position of the artificial teeth and will fit into intracoronal rests. D, Internal attachment prosthesis in the patient’s mouth. Note the precise fit of male and female portions of the attachments.

Despite these disadvantages, the use of removable prostheses may be preferred whenever tooth-bounded edentulous spaces are too large to be restored safely with fixed prostheses, or when cross-arch stabilization and wider distribution of forces to supporting teeth and tissues are desirable. Fixed partial dentures, however, should always be considered and used when indicated.

The removable partial denture retained by internal attachments eliminates some of the disadvantages of clasps, but it has other disadvantages, one of which is higher cost, which makes it more difficult to obtain for a large percentage of patients who need partial dentures. However, when alignment of the abutment teeth is favorable and periodontal health and bone support are adequate, when the clinical crown is of sufficient length and the pulp morphology can accommodate the required tooth preparation, and when the economic status of the patient permits, an internal attachment prosthesis provides an unquestionable advantage for esthetic reasons. When this situation exists, carefully weighing of tooth attachment versus implant attachment options is required (see RPDs and Implants, Chapter 25).

In most instances, if the extracoronal clasp-retained partial denture is designed properly, the only advantage of the internal attachment denture is esthetic, because abutment protection and stabilizing components should be used with both internal and external retainers. However, economics permitting, esthetics alone may justify the use of internal attachment retainers, especially when a crown is indicated for non-RPD reasons.

Injudicious use of internal attachments can lead to excessive torsional load on the abutments supporting distal extension removable partial dentures, especially in the mandible. The use of hinges or other types of stress breakers is discouraged in these situations. It is not that they are ineffective, but that they are frequently misused. As an example, in the mandibular arch, a stress-broken distal extension partial denture does not provide for cross-arch stabilization and frequently subjects the edentulous ridge to excessive trauma from horizontal and torquing forces. Therefore a rigid design is preferred, and some type of extracoronal clasp retainer is still the most logical and the most frequently used. It seems likely that its use will continue until a more widely acceptable retainer is devised.

As was reviewed in Chapter 1, the most commonly cited problem associated with removable partial dentures is instability. Healthy natural teeth should not move when used; therefore we should strive to provide and maintain as stable a prosthesis as possible given the means available. How do we ensure functional stability? By understanding that a removable partial denture can move under function (because it is not cemented to teeth like a fixed partial denture). We should take steps to prescribe the necessary prosthetic fit to teeth (and tissue) to control movement as much as possible. This entails providing appropriate natural tooth mouth preparations, ensuring an accurate frame fit at tooth and tissue, providing a simultaneous contacting relationship between natural and prosthetic opposing teeth, and providing and maintaining optimum support from the soft tissue and teeth.

As we will review in Chapter 4, control of the anticipated movement of your prosthesis is addressed by assigning the appropriate component part of the prosthesis to contact/engage the tooth or tissue in a manner that allows movement and removal of the prosthesis. Are there movements that we should control that are more important than others? Although we recognize the need to resist movement away from the teeth and tissue to keep prostheses from falling out of mouths, the most damaging forces are those resulting from functional closure during chewing (and in some patients, parafunction). Consequently, control of combined vertical (tissue-ward) and horizontal movement is most critical and places a premium on tooth modifications (rest and stabilizing component preparations) and verification of adequate fit of the frame to the teeth.

Six Phases of Partial Denture Service

Partial denture service may be logically divided into six phases. The first phase is related to patient education. The second phase includes diagnosis, treatment planning, design of the partial denture framework, treatment sequencing, and execution of mouth preparations. The third phase is the provision of adequate support for the distal extension denture base. The fourth phase is establishment and verification of harmonious occlusal relationships and tooth relationships with opposing and remaining natural teeth. The fifth phase involves initial placement procedures, including adjustments to the contours and bearing surfaces of denture bases, adjustments to ensure occlusal harmony, and a review of instructions given the patient to optimally maintain oral structures and provided restorations. The sixth and final phase of partial denture service consists of follow-up services by the dentist through recall appointments for periodic evaluation of the responses of oral tissue to restorations and of the acceptance of restorations by the patient. The following is an overview of these phases. The context of each phase is discussed in greater detail in the respective chapters of this book.

Education of Patient

The term patient education is described in Mosby’s Dental Dictionary as “the process of informing a patient about a health matter to secure informed consent, patient cooperation, and a high level of patient compliance.”

The dentist and the patient share responsibility for the ultimate success of a removable partial denture. It is folly to assume that a patient will have an understanding of the benefits of a removable partial denture unless he or she is so informed. It is also unlikely that the patient will have the knowledge to avoid misuse of the restoration or will be able to provide the required oral care and maintenance procedures to ensure the success of the partial denture unless he or she is adequately advised.

The finest biologically oriented removable partial denture is often doomed to limited success if the patient fails to exercise proper oral hygiene habits or ignores recall appointments. Preservation of the oral structures, one of the primary objectives of prosthodontic treatment, will be compromised without the patient’s cooperation in oral hygiene and regular maintenance visits.

Patient education should begin at the initial contact with the patient and should continue throughout treatment. This educational procedure is especially important when the treatment plan and prognosis are discussed with the patient. Limitations imposed on the success of treatment through failure of the patient to accept responsibility must be explained before definitive treatment is undertaken. A patient usually will not retain all the information presented in the oral educational instructions. For this reason, patients should be given written suggestions to reinforce the oral presentations.

Diagnosis, Treatment Planning, Design, Treatment Sequencing, and Mouth Preparation

Treatment planning and design begin with thorough medical and dental histories. The complete oral examination must include both clinical and radiographic interpretation of (1) caries, (2) the condition of existing restorations, (3) periodontal conditions, (4) responses of teeth (especially abutment teeth) and residual ridges to previous stress, and (5) the vitality of remaining teeth. In addition, evaluation of the occlusal plane, the arch form, and the occlusal relations of the remaining teeth must be meticulously accomplished by clinical visual evaluation and diagnostic mounting. After a complete diagnostic examination has been accomplished and a removable partial denture has been selected as the treatment of choice, a treatment plan is sequenced and a partial denture design is developed in accordance with available support.

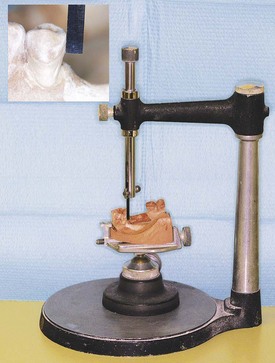

The dental cast surveyor (Figure 2-2) is an absolute necessity in any dental office in which patients are being treated with removable partial dentures. The surveyor is instrumental in diagnosing and guiding the appropriate tooth preparation and verifying that the mouth preparation has been performed correctly. There is no more reason to justify its omission from a dentist’s armamentarium than there is to ignore the need for roentgenographic equipment, the mouth mirror and explorer, or the periodontal probe used for diagnostic purposes.

Figure 2-2 Dental cast surveyor facilitates the design of a removable partial denture. It is an instrument by which parallelism or lack of parallelism of abutment teeth and other oral structures, on a stone cast, can be determined (magnified view shows parallel guide plane surface). Use of the surveyor is discussed in later chapters.

Several moderately priced surveyors that adequately accomplish the diagnostic procedures necessary for designing the partial denture are available. In many dental offices, this most important phase of dental diagnosis is delegated to the commercial dental laboratory because this invaluable diagnostic tool is absent, or because the dentist feels inexperienced or is apathetic. This situation places the technician in the role of diagnostician. Any clinical treatment based on the diagnosis of the technician remains the responsibility of the dentist. This makes no more sense than relying on the technician to interpret radiographs and to render a diagnosis.

After treatment planning, a predetermined sequence of mouth preparations can be performed with a definite goal in mind. It is mandatory that the treatment plan be reviewed to ensure that the mouth preparation necessary to accommodate the removable partial denture design has been properly sequenced. Mouth preparations, in the appropriate sequence, should be oriented toward the goal of providing adequate support, stability, retention, and a harmonious occlusion for the partial denture. Placing a crown or restoring a tooth out of sequence may result in the need to restore teeth that were not planned for restoration, or it may necessitate remaking a restoration or even seriously jeopardizing the success of the removable partial denture. Through the aid of diagnostic casts on which the tentative design of the partial denture has been outlined and the mouth preparations have been indicated in colored pencil, occlusal adjustments, abutment restorations, and abutment modifications can be accomplished.

Support for Distal Extension Denture Bases

The third of the six phases in the treatment of a patient with a partial denture involves obtaining adequate support for distal extension bases. Therefore it does not apply to tooth-supported removable partial dentures. With the latter, support comes entirely from the abutment teeth through the use of rests.

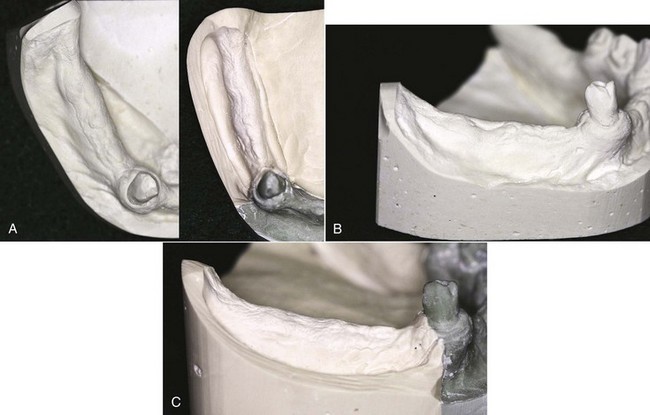

For the distal extension partial denture, however, a base made to fit the anatomic ridge form does not provide adequate support under occlusal loading (Figure 2-3). Neither does it provide for maximum border extension nor accurate border detail. Therefore some type of corrected impression is necessary. This may be accomplished by several means, any of which satisfy the requirements for support of any distal extension partial denture base.

Figure 2-3 A, Occlusal view of a cast from a preliminary impression, which produced an anatomic ridge form (left), and an altered cast of the same ridge showing a functional or supportive form (right). The altered cast impression selectively placed pressure on the buccal shelf region, which is the primary stress-bearing area of the mandibular posterior residual ridge. B, Buccal view of anatomic ridge form. C, Buccal view of functional or supportive ridge form. Note that the supportive form of the ridge clearly delineates the extent of coverage available for a denture base and is most different from the anatomic form when the mucosa is easily displaced.

Foremost is the requirement that certain soft tissue in the primary supporting area should be recorded or related under some loading, so that the base may be made to fit the form of the ridge when under function. This provides support and ensures maintenance of that support for the longest possible time. This requirement makes the distal extension partial denture unique in that support from the tissue underlying the distal extension base must be made as equal to and compatible with the tooth support as possible.

A complete denture is entirely tissue supported, and the entire denture can move toward the tissue under function. In contrast, any movement of a partial denture base is inevitably a rotational movement that, if toward the tissue, may result in undesirable torquing forces to the abutment teeth and loss of planned occlusal contacts. Therefore every effort must be made to provide the best possible support for the distal extension base to minimize these forces.

Usually no single impression technique can adequately record the anatomic form of the teeth and adjacent structures and at the same time record the supporting form of the mandibular edentulous ridge. A method should be used that can record these tissues in their supporting form or in a supporting relationship to the rest of the denture (see Figure 2-3). This may be accomplished by one of several methods that will be discussed in Chapter 16.

Establishment and Verification of Occlusal Relations and Tooth Arrangements

Whether the partial denture is tooth supported or has one or more distal extension bases, the recording and verification of occlusal relationships and tooth arrangement are important steps in the construction of a partial denture. For the tooth-supported partial denture, ridge form is of less significance than it is for the tooth- and tissue-supported prosthesis because the ridge is not called on to support the prosthesis. For the distal extension base, however, jaw relation records should be made only after the best possible support is obtained for the denture base. This necessitates the making of a base or bases that will provide the same support as the finished denture. Therefore the final jaw relations should not be recorded until after the denture framework has been returned to the dentist, the fit of the framework to the abutment teeth and opposing occlusion has been verified and corrected, and a corrected impression has been made. Then a new resin base or a corrected base must be used to record jaw relations.

Occlusal records for a removable partial denture may be made by the various methods described in Chapter 17.

Initial Placement Procedures

The fifth phase of treatment occurs when the patient is given possession of the removable prosthesis. Inevitably it seems that minute changes in the planned occlusal relationships occur during processing of the dentures. Not only must occlusal harmony be ensured before the patient is given possession of the dentures, but the processed bases must be reasonably perfected to fit the basal seats. It must be ascertained that the patient understands the suggestions and recommendations given by the dentist for care of the dentures and oral structures and understands about expectations (based on the “Shared Decision Making” discussion) in the adjustment phases and the use of restorations. These facets of treatment are discussed in detail in Chapter 20.

Periodic Recall

Initial placement and adjustment of the prosthesis certainly is not the end of treatment for the partially edentulous patient. Periodic reevaluation of the patient is critical for early recognition of changes in oral structures to allow steps to be taken to maintain oral health. These examinations must monitor the condition of the oral tissue, the response to tooth restorations, the prosthesis, the patient’s acceptance, and the patient’s commitment to maintain oral hygiene. Although a 6-month recall period is adequate for most patients, more frequent evaluation may be required for some. Chapter 20 contains some suggestions concerning this sixth phase of treatment.

Reasons for Failure of Clasp-Retained Partial Dentures

Experience with the clasp-retained partial denture made by the methods outlined has proved its merit and justifies its continued use. The occasional objection to the visibility of retentive clasps can be minimized through the use of wrought-wire clasp arms. Few contraindications for use of a properly designed clasp-retained partial denture are known. Practically all objections to this type of denture can be eliminated by pointing to deficiencies in mouth preparation, denture design and fabrication, and patient education. These include the following:

A removable partial denture designed and fabricated so that it avoids the errors and deficiencies listed is one that proves the clasp-type partial denture can be made functional, esthetically pleasing, and long lasting without damage to supporting structures. The proof of the merit of this type of restoration lies in the knowledge that (1) it permits treatment for the largest number of patients at a reasonable cost; (2) it provides restorations that are comfortable and efficient over a long period of time, with adequate support and maintenance of occlusal contact relations; (3) it can provide for healthy abutments, free of caries and periodontal disease; (4) it can provide for the continued health of restored, healthy tissue of the basal seats; and (5) it makes possible a partial denture service that is definitive and not merely an interim treatment.

Removable partial dentures thus made will contribute to a concept of prosthetic dentistry that has as its goal the promotion of oral health, the restoration of partially edentulous mouths, and elimination of the ultimate need for complete dentures.