School-Based Occupational Therapy

1 Describe major legislation affecting special and general education, including the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, and No Child Left Behind (NCLB), for students with and without disabilities.

2 Discuss the impact of major legislation on the role of occupational therapists in schools.

3 Identify major amendments in IDEA that have been implemented over the past 3 decades.

4 Define the major provisions of Part B of IDEA—free, appropriate education in the least restrictive environment (FAPE).

5 Describe the occupational therapy process under Part B of IDEA including referral, evaluation, individual education program (IEP), and service provision.

6 Describe how integrated service delivery supports inclusion of students with disabilities.

7 Explain how occupational therapy consultation contributes to inclusive models of practice.

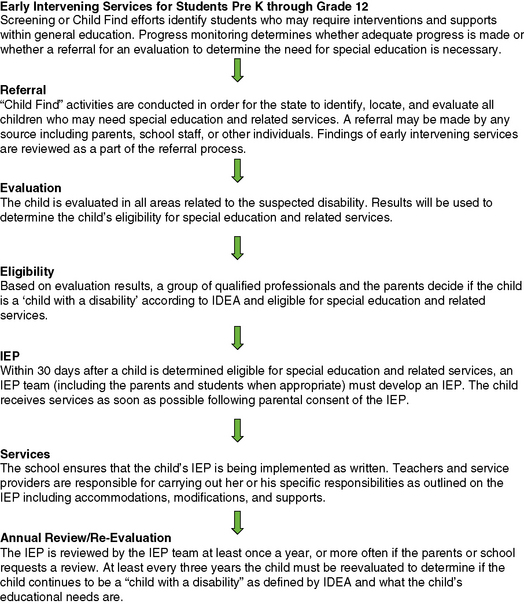

8 Discuss roles for occupational therapists under IDEA 2004 and NCLB to serve students in general and special education through early intervention services (EIS) and response to intervention (RtI).

9 Describe occupational therapy’s role in the promotion of school mental health within a prevention-based multitiered model.

The task of a sound education, Plato argued twenty-five centuries ago, is to teach young people to find pleasure in the right things. If children enjoyed math, they would learn math. If they enjoyed helping friends, they would grow into helpful adults. If they enjoyed Shakespeare, they would not be content watching television programs. If they enjoyed life, they would take greater pains to protect it (p. 39).21

Education systems around the world have the responsibility of preparing children for adulthood and, as such, most professionals agree that schools must provide the intellectual and practical tools needed for successful participation in classrooms, families, future workplaces, and communities.27 Occupational therapy practitioners help people of all ages engage in and enjoy meaningful and purposeful life activities—in schools, this means helping children participate in the academic, social, extracurricular, independent living, and vocational activities needed for student success and transition.2,79 Given occupational therapy’s focus on a broad range of occupational performance areas (education, social participation, play, leisure, work, activities of daily living), it is not surprising that occupational therapists enjoy a long tradition of providing services in schools and early intervention settings, making these the primary work environments for occupational therapists.45

Practice in schools is influenced by an educational versus medical model requiring a set of knowledge and skills unique to both occupational therapy and school settings. School-based therapists must combine a sound understanding of occupational therapy’s domain of practice with a current understanding of the school context, which is guided by federal laws and regulations. In a recent U.S. survey, school-based occupational therapists identified the greatest need for knowledge and skills in the areas of federal/state regulations, role of occupational therapy, evaluation and intervention approaches, writing individualized education program (IEP) goals, collaboration, and evaluation for assistive technology.10 This chapter provides information to prepare occupational therapists for school-based practice.

SPECIAL AND GENERAL EDUCATION LEGISLATION

Federal policy, which is shaped by trends in health and education practice, directly influences services for children. Although occupational therapy’s early work with children occurred primarily in medical rather than educational settings, a rapid shift to practicing in schools took place with the enactment of the Education of All Handicapped Act (EHA) of 1975 (P.L. 94-142). At the time this law was enacted, more than 1 million children with disabilities were excluded from the public school system, and for those who did receive education, more than half did not receive appropriate services. This legislation, now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 2004) (i.e., P.L. 108-446), requires that states provide free appropriate education (FAPE) in the least restrictive environment (LRE) for students with disabilities attending public schools. Further, the law stipulates that individually designed special education and related services must be provided to students 3 to 21 years of age, if the student needs such services to benefit from her or his education (§300.17). As a related service provider, occupational therapy is defined in the law and accompanying federal regulations as “such developmental, corrective, and other supportive services as are required to assist a child with a disability to benefit from special education, and includes… occupational therapy” (IDEA 2004, Final Regulations, §300.34, 2006). IDEA increased the demand for occupational therapy practitioners employed in schools exponentially because of the legal mandate to provide services should a child require occupational therapy to benefit from special education.

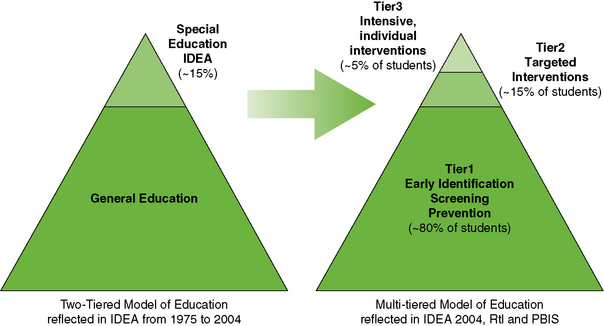

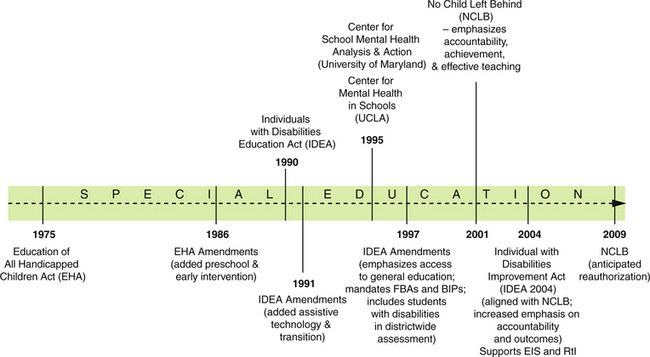

Once legislation such as IDEA becomes law, the agency responsible for the program (e.g., U.S. Department of Education) develops regulations to guide implementation at the national, state, and local levels. In addition, federal laws are reauthorized routinely to allow for review and revisions based on the needs of children and their families. For example, IDEA is reauthorized every 5 to 7 years. Although keeping up with evolving policies can be an overwhelming task, it is critical for occupational therapy practitioners working in educational settings to maintain an understanding of current policies to provide appropriate services and take advantage of new opportunities for practice.45,60 Figure 24-1 depicts a timeline of important legislation, policy changes, and practice developments influencing school practice. This section provides a brief overview of key legislation influencing occupational therapy practice in schools. This is followed by a more detailed discussion of the evolution of IDEA and No Child Left Behind (NCLB) and the major shifts in occupational therapy practice that have resulted.

FIGURE 24-1 Timeline of important legislation and developments influencing occupational therapy’s role in schools.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

Most children with disabilities receiving occupational therapy in schools obtain services under IDEA, with a smaller number served under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. IDEA establishes educational programs that ensure two significant rights for children with disabilities—FAPE in the LRE.67 Four additional principles guiding the education of children with disabilities were adopted with the original law in 1975 and have remained unchanged, but with subsequent amendments (Box 24-1).

Each of these concepts has significant implications for the public education system, children with disabilities and their families, and occupational therapists. A “free appropriate public education” refers to special education and related services that (1) meet the standards of the state education agency (SEA); (2) are provided at public expense; (3) are under public supervision and direction; (4) include an appropriate education at preschool, elementary, and secondary levels; and (5) are provided in accordance with an individualized education program (IEP). “Free” means at no cost to parents, but of course does not preclude the incidental fees that are normally charged to students without disabilities. The word “appropriate” is more difficult to define because it does not necessarily refer to a grade level or the chronologic age of a child. The IEP, as the centerpiece of IDEA, is used by parents to ensure the development of an “appropriate” special education program to meet their child’s unique needs. This program is based on results of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary assessment. As part of the educational team, occupational therapists have essential roles in these processes.

Least Restrictive Environment

IDEA mandates that students with disabilities be offered special education and related services in the LRE. This means that children with disabilities are educated with children who are not disabled, to the maximum extent appropriate (§300.114). Whatever the disability, the first student placement that should be considered according to IDEA is the general education classroom, with appropriate aids and supports.42 This policy is clearly stated in IDEA; the “removal of children with disabilities occurs only when the nature or severity of the disability of a child is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily” (32 C.F.R., §612[5][A]). The overriding rule is that placement decisions must be determined on an individual basis, based on the child’s unique needs and IEP.

The amount of support provided to students integrated in general education varies from a full-time aide to periodic, consultative services by an occupational therapist or special educator. When a child cannot be educated in the regular classroom, an alternative placement is considered. Accordingly, schools are required by law to ensure that a continuum of alternative placements is available to meet the needs of children with disabilities. This continuum includes a range of alternative placements such as instruction in regular classes, special classes, special schools, home instruction, and instruction in hospitals and institutions. Most children with disabilities spend at least a portion of their day in general education classrooms.

Evolution of IDEA

Although the original goal of FAPE in the LRE for children with disabilities has not changed, each reauthorization of IDEA has prompted reflection and a reevaluation of educational services, which, in turn, has brought about important shifts in the delivery of special education and related services.

In 1986, amendments allowed states to provide preschool and early intervention services for children with disabilities from birth to age 5. To reflect current language, the law’s name was changed to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act in 1990. This amendment authorized additional services (i.e., assistive technology services and devices and transition planning). The reauthorization in 1997 was significant in placing greater emphasis on delivering related services to children with disabilities within the context of the student’s general education curriculum.59,65 As a result, there has been a gradual shift in service delivery from traditional “pull-out” approaches to the integration of occupational therapy services into the student’s classroom and other relevant school environments (e.g., lunchroom, playground, restroom).78 This shift has required occupational therapists to become knowledgeable about the curriculum adopted in specific classrooms and within their school district so that they can better specify how a student’s disability affects functioning within the educational environment and develop relevant intervention strategies. The IDEA Amendments of 1997 also focused on student outcomes by requiring students with disabilities to be included in state and districtwide assessments.

IDEA was most recently reauthorized in 2004 as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act. The primary goals of IDEA 2004 are to increase the focus of education on results; prevent problems through early intervening; and improve students’ academic achievement, functional outcomes, and postsecondary success.45 By focusing on accountability and improving educational outcomes, Congress intentionally aligned IDEA 2004 with the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) of 2002. The long-term goal of special education and related services according to IDEA is to prepare students with disabilities for further education, employment, and independent living.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) complement IDEA to ensure nondiscrimination against children with disabilities in public schools.87 Section 504 requires schools receiving federal funds to provide qualified students with disabilities access to public education. The ADA ensures that the educational program is accessible to individuals with disabilities and may include providing specific accommodations. The definition of “disability” under Section 504 and ADA includes any student with “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, who has record of such an impairment, or is regarded as having such an impairment” (34 C.F.R. 104.3(j)(2)(i)). Some examples of impairments that may substantially limit major life activities are mental illness, specific learning disabilities, arthritis, cancer, diabetes, and hearing impairment. Major life activities include caring for oneself, education and learning, performing manual tasks, seeing, hearing, speaking, working, walking, and breathing. Because this definition is broader than IDEA’s definition of disability, students who are not IDEA-eligible may be 504-eligible for accommodations to access to the learning environment. “Under Section 504, occupational therapy can be provided alone or in combination with other educations services and may be provided directly to students or as program supports to teachers working with the student” (p. 1).3 Student eligibility for Section 504 services are documented in guidelines developed by each state and local school agency.

Sometimes students with diagnoses such as attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), for example, are not eligible for special education programs. However, these students may struggle to fully participate in classroom activities and often benefit from occupational therapy services. Occupational therapy in the schools can be provided to these students under Section 504. Because the definition of disability is broader in this civil rights act, a child may be eligible for occupational therapy, even when he or she is not eligible for special education services. Although school personnel are not required to develop IEPs for students served under the Rehabilitation Act, a team should develop a written plan that states goals, services, and accommodations needed to meet those goals.45

Although additional federal and state funds are not provided for these laws, school districts that do not provide accommodations to students who are eligible through Section 504 and ADA can lose federal funding. Occupational therapy practitioners may assist the school team in determining the most effective and efficient solutions for meeting students’ needs under Section 504 and the ADA.

No Child Left Behind

NCLB, signed into law in 2002 (Public Law 107-110), made major changes to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965. The original intent of this law was to ensure that all children have an equal opportunity to participate in and receive a good education in school.66 This law, which is considered a key component in the education reform movement, covers all public schools in all states.

NCLB is mainly understood to be a general education law emphasizing increased accountability for results. Under this law, states are working to close the achievement gap by establishing high achievement standards for all students, especially those who are disadvantaged because of poverty or disability.81 Based on yearly testing, annual state and district report cards indicate whether the state, district, and schools are making adequate yearly progress (AYP) toward proficiency (i.e., achieving grade level). Parents whose children are attending Title I (low-income) schools that do not make AYP for several years are given the option to transfer their child to a better performing school or obtain free tutoring.82 In addition to proficiency testing, NCLB raised the requirements for public school teachers in all states to meet the standards of “highly qualified”—holding at least a bachelor’s degree and having passed a state test of subject knowledge.

This synthesis of legislation provides the foundation for understanding the evolving role of occupational therapy practitioners working in schools. In the following sections, occupational therapy’s traditional role serving children with disabilities is presented, followed by a discussion of emerging roles in general education and school mental health based on current legislation. For example, changes brought about by the reauthorization of IDEA and the enactment of NCLB have been instrumental in providing opportunities for expanding occupational therapy’s role to serving all children attending school.45

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY SERVICES FOR CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES

Occupational Therapy Domain in School-Based Practice

Education is identified as one of the key performance areas in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process, 2nd edition (Framework-II) (2008) and refers to the “activities needed for being a student and participating in the learning environment” (p. 620).1 The occupation of education includes academic (math, reading, writing), nonacademic (recess, lunch, self-help skills), extracurricular (sports, band, cheerleading, clubs), and prevocational and vocational activities.49 Consequently, in addressing a student’s education, attention to a broad range of occupational performance areas is often required to help children succeed in their student role including play, leisure, social participation, activities of daily living, and work.

Occupational therapists working in schools must skillfully combine their professional knowledge and skills with the definition of occupational therapy in federal and state education legislation. School districts are mandated to provide related services, including occupational therapy, when a student who receives special education requires such services to benefit from special education. “Related services” means “transportation, and such developmental, corrective, and other supportive services (including speech-language pathology and audiology services, interpreting services, psychological services, physical and occupational therapy, recreation, including therapeutic recreation, social work services, school nurse services… counseling services, including rehabilitation counseling, orientation and mobility services, and medical services, except that such medical services shall be for diagnostic and evaluation purposes only as may be required to assist a child with a disability to benefit from special education, and includes the early identification and assessment of disabling conditions in children” (§300.320(a)(4)). Special education and related services may be provided in a number of settings including schools, homes, hospitals, juvenile justice centers, and alternative education settings.2

Occupational therapy services must be educationally relevant, by contributing to the development, or improvement, of the child’s academic and functional school performance. The regulations of IDEA define occupational therapy broadly as “(A) improving, developing or restoring functions impaired or lost through illness, injury or deprivation, (B) improving ability to perform tasks for independent functioning when functions are impaired or lost, and (C) preventing, through early intervention, initial or further impairment or loss of function” [§300.34(c)(6)]. Occupational therapy services can promote self-help skills (e.g., eating, dressing); positioning (e.g., sitting appropriately in class); sensory-motor processing; fine motor performance; psychosocial function; and life skills training.64 Services must be provided by a qualified occupational therapist or service provider under the direction or supervision of a qualified occupational therapist. Although regulations focus on what constitutes “highly qualified” teachers, requirements beyond adhering to state licensure laws have not been created for occupational therapy.44

Occupational Therapy Process in School-Based Practice

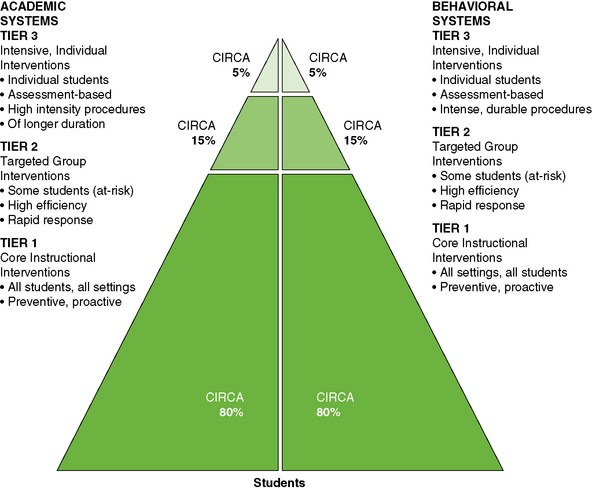

The reauthorization of IDEA (2004) increased the focus of special education and related services on results—including academic achievement, functional outcomes, and postsecondary success. Expected outcomes for students with disabilities leaving high school include higher education, employment, and independent living (§602(d)). In collaboration with other members of the education team, occupational therapists contribute to the referral, evaluation, intervention, and outcome processes. With these important outcomes in mind, a key question guiding the special education process should be: “What does the child need or want to do to be successful as a student now and to prepare for future roles?”79 The special education process is depicted in Figure 24-2. This section describes the occupational therapy processes of referral, evaluation, and intervention.

Referral

Each local education agency (LEA) has a “Child Find” system that locates, identifies, and evaluates all children who have disabilities and need special education.69 A referral of a child suspected as having a disability may be made by any source, including parents, teachers, or other individuals. An occupational therapist evaluation may be requested at the time of initial referral if the team perceives that information provided by an occupational therapist will contribute to the evaluation process. This suggests how critical it is for school administrators and other team members to have an accurate understanding of the domain and scope of occupational therapy practice—that occupational therapists address the education, activities of daily living, play, leisure, work, and social participation areas of function related to the student’s academic and nonacademic expectations. If team members have a narrow understanding of the scope of occupational therapy practice (e.g., occupational therapists address handwriting issues), then it is likely that the role of occupational therapy in that setting will be narrow as well.48 Effort spent in informing principals, teachers, school psychologists, and other personnel about the role of occupational therapy in regular and general education ensures that students who may benefit from occupational therapy services are identified.

Evaluation

“Evaluation means procedures used in accordance with §§300.304–300.311 to determine whether a child has a disability and the nature and extent of the special education and related services that the child needs” (§300.15).

After obtaining parental consent, a full and individual evaluation is completed by a multidisciplinary team to determine whether the child is eligible for special education and, if so, it identifies educational and related service needs (§300.301). This multidisciplinary evaluation is needed even when the child has an obvious disability (e.g., cerebral palsy, Down syndrome) and has received therapeutic services in the past (e.g., in an early intervention program). In addition, this team determines the nature and scope of the full and individual evaluations for each child and decides if related services evaluations, including occupational therapy, are needed. The role of the occupational therapist in the evaluation process depends on how well he or she has explained the role and the team’s understanding of the domain and scope of occupational therapy.

IDEA and the OTPF define evaluation and assessment consistently.1 Evaluation refers to the process of gathering and interpreting information about the student’s strengths and educational needs. Assessments refer to the tests or measures used to obtain data about specific areas of function. IDEA specifies that school personnel evaluate referred or eligible students in all areas of suspected disability. Furthermore, a variety of assessment tools or evaluation strategies must be used to obtain relevant academic, functional, and developmental information about the student (§300.304(b)(1)). The evaluation must be completed within 60 days of initial parent consent, unless the state specifies otherwise.

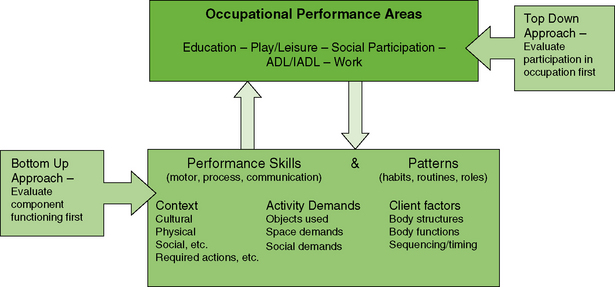

Top-down or occupation-based approach. Although one of the main purposes of evaluation according to IDEA is to determine eligibility, which is based on qualifying as a child with a disability, the law has placed greater emphasis on assessing the child’s participation needs in relevant school contexts. This thinking is in agreement with current social views regarding the evaluation of children and those adopted within the profession of occupational therapy. A top-down approach to evaluation is believed to more accurately reflect the true nature of occupational therapy and has been referred to as occupation-based evaluation.69 A top-down approach to evaluation begins with gathering information about what the person needs and wants to do across a variety of occupational performance areas and settings (Figure 24-3).18,30 Box 24-2 provides a description of the School Function Assessment19 representing a top-down strategy used to initiate the evaluation process. Performance component function is assessed to the extent that it is thought to limit participation in occupation. An occupational therapist’s ability to implement this approach is dependent on using appropriate evaluation strategies and assessment tools, developing the knowledge and skills needed to implement these strategies, and then actually using them in practice.

International social views of children’s health also focus on participation in context. The World Health Organization (WHO), for example, recently published the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY), in 2007.86 This document emphasizes that the health of children is dependent upon their participation in context—both within their stage of development and in relevant environments. Similar to IDEA and OTPF, this model focuses on how multiple factors (i.e., individual abilities, activity, and context) influence the child’s function.69

Evaluation Strategies

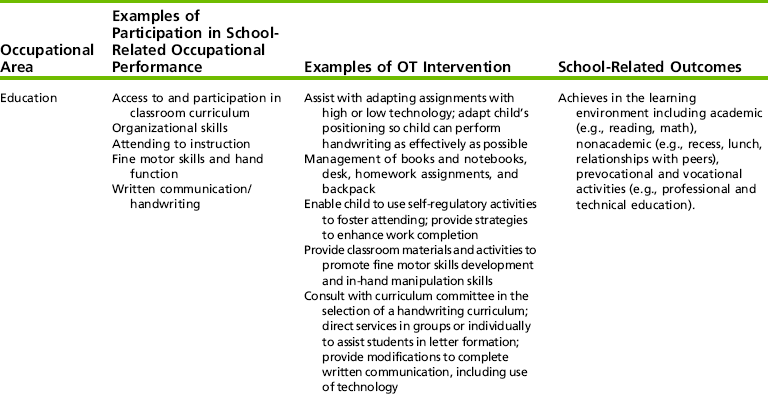

“Occupation-based evaluation approaches help the IEP team make decisions about the student’s ability to participate and perform in the school setting and identify the ways that the disability affects the student’s participation in school activities and routines” (p. 35).69 The occupational therapy evaluation focuses on areas of strength and weakness in educationally relevant occupational performance areas (education, social participation, activities of daily living, play, leisure, and work) related to the student’s suspected disability (Table 24-1). Obtaining an occupational profile initiates the evaluation process by exploring the student’s educational history, interests, values, and needs. The student may be interviewed using questions such as the following:

TABLE 24-1

School-Related Occupational Performance Addressed During Evaluation and Intervention

Adapted from Kentucky Department of Education. (2006). Resource manual for educationally related occupational therapy and physical therapy in Kentucky public schools; and Swinth, Y. (2007). Evaluating evidence to support practice. In L. L. Jackson (Ed.), Occupational therapy services for children and youth under IDEA (3rd ed.) Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association; and Swinth, Y., Chandler, B., Hanft, B., Jackson, L., & Shepherd, J. (2003). Personnel issues in school-based occupational therapy: Supply and demand, preparation, certification and licensure. (COPSSE Document No. IB-1). Gainesville, FL: University of Florida, Center on Personnel Studies in Special Education.

The therapist can also interview the teacher about his or her classroom expectations for the student. The parents are asked to identify their priorities for the child. Information obtained from the occupational profile assists the therapist in developing initial impressions about the student’s difficulties, which may be useful in directing the rest of the evaluation process.

In addition to interviews, other useful evaluation strategies include document or chart review to obtain background information and observations of the student in a variety of school contexts (e.g., classroom, cafeteria, playground, locker room). The evaluation process involves an examination of the dynamic relationship among the student’s participation and performance skills, educational context, and specific educational/activity demands that may be contributing to the problems.79 For example, to fully understand a student’s difficulty with written communication during test-taking, the therapist may want to observe the student while taking a test, compare work with that of peers in the same environment, and explore curricular demands with the teacher.

Evaluation of school environment includes the classrooms, cafeteria, playgrounds, gymnasium, and other spaces (Figure 24-4). For children using wheelchairs or walkers, the focus of this part of the assessment may be accessibility. For children with sensory processing problems, the focus may be the degree and types of sensory stimulation in the environment. Classrooms tend to be highly visually stimulating environments, and they can be disorganizing and overwhelming to students with sensory processing problems (Figure 24-5).

FIGURE 24-4 The playground is one environment to be evaluated, emphasizing accessibility and safety. Although schools are constructing playgrounds with wheelchair accessibility, many remain only partially accessible. Playgrounds should include equipment that requires a range of skills and a range of sensory input.

To analyze educational and/or activity demands, the expected performance (as defined by the teacher and curriculum) must be understood fully. When teachers expect neat, precisely aligned, and well-formed handwriting, a student with poor handwriting will have a significant problem in meeting that teacher’s standard. As another example, some teachers show high tolerance for disruptive behavior and allow students to move freely about the room. A student with a high activity level and sensory-seeking behaviors would have greater success in a classroom where movement was allowed, rather than one in which students were expected to remain in their seats. Often a student’s goals and services are based more on the discrepancy between the student’s performance and classroom-teacher expectations than on performance delays as determined by norms that reference the student’s age. In addition, occupational therapists need to become familiar with their states’ learning and achievement standards—accessible from the state’s department of education website.

Assessment Measures

The occupational therapist may also decide to administer informal or formal assessment measures to obtain a full evaluation of the child’s occupational performance related to curricular and extracurricular needs. However, according to IDEA, the use of assessment tools is not required if observations and interviews have provided the needed information for decision making. Because the number of standardized pediatric assessments available today has grown significantly over the past 2 decades, it is important for occupational therapists practicing in schools to make informed decisions when selecting assessments.

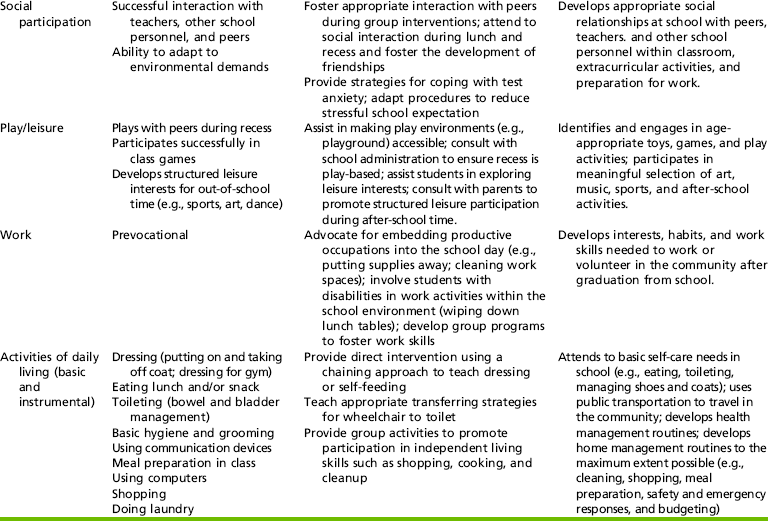

Three basic constructs of pediatric assessments have been identified—developmental, functional, and health-related quality of life (HRQL).38 These are described in Table 24-2. Although developmental assessments may be particularly helpful when working with infants and preschoolers to identify developmental delays, these are less useful with the school-aged population, where the emphasis shifts to functional performance and participation in context. Developmental assessments measure a child’s behavior and skills rather than the ability to function as a student.80 With a developmental approach, intervention emphasizes normalizing the underlying processes to achieve greater function.17 Current intervention approaches, however, suggest that in addition to addressing characteristics of the person, physical and social aspects of the environment, and features of the activity, influence function and need to be addressed.18

TABLE 24-2

Data from Coster, W., Deeney, T., Haltiwanger, J., & Haley, S. (1998). School function assessment. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; Davies, P. L., Soon, P. L., Young, M., & Clausen-Yamaki, A. (2004). Validity and reliability of the school function assessment in elementary school students with disabilities. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 24, 23-43; Haley, S. M. (1994). Our measures reflect our practices and beliefs: A perspective on clinical measurement in pediatric physical therapy. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 6, 142-3; and Schneider, J. W., Gurucharri, L. M., Gutierrez, A. L., & Gaebler-Spira, D. J. (2000) Health-related quality of life and functional outcome measures for children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 43, 601-608.

In contrast to developmental assessments, functional assessments measure abilities and limitations in performance of necessary daily activities.22 The School Function Assessment (SFA)19 and a growing number of functional, top-down assessments are now available. Although a number of occupation-based assessments have been published in the past decade, one survey found that school-based occupational therapy practitioners primarily used developmental assessments of gross and fine motor skills (e.g., Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency, Peabody Developmental Motor Scales, Beery Test of Visual Motor Integration).12 When the findings of this survey were compared with previous research, similar trends in the use of motor and visual perception tests were found.

One of the major obstacles to using functional assessments is the dominance of the developmental model.18 Functional assessments have only been available during the past 10 years, and time is needed for therapists to become educated and skilled in using them. Most functional assessments (e.g., the SFA) are often designed so that multiple team members (parents, teachers, and therapists) knowledgeable about the student’s performance can contribute to the data-gathering process, yielding a comprehensive understanding of the child. In a study of the validity and reliability of the SFA, findings suggest that occupational therapists and teachers view students’ functioning similarly.22

Recent evidence has indicated that in addition to using adult informants, children can also participate more actively in the evaluation process and goal setting if the procedures used are developmentally appropriate.57 The Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System (PEGS)58 is one example of such a measure. The PEGS was designed to help children with disabilities reflect on their ability to perform everyday activities and identify goals for occupational therapy intervention. Another assessment tool developed to gather information directly from the child is the School Setting Interview (SSI).43 The information gathered from these measures on children’s thoughts and feelings about their ability to fulfill childhood roles can complement results obtained from functional assessments by providing a more complete picture of the person.72 In addition, occupational therapists may consider using some type of HRQL measures to obtain a clear sense of the child’s life satisfaction.

Documentation

The final step in the evaluation process involves effectively communicating the findings and recommendations in a written report. Occupational therapy documentation should reflect a top-down presentation of the student’s strengths and limitations regarding participation in academic and nonacademic activities across all student environments. Performance component issues (e.g., body structure and function) that affect participation should be reported using language understandable to all team members, including parents.

Eligibility

After the evaluation process, the team reviews all of the data to determine eligibility for special education and related services. A student is eligible for special education under IDEA if she or he meets two criteria: (1) is a child with a disability under one of the disability categories or under the developmental delay category; and (2) needs special education services. The disability categories include: mental retardation, a hearing impairment (including deafness), a speech or language impairment, a visual impairment (including blindness), a serious emotional disturbance, an orthopedic impairment, autism, traumatic brain injury, another health impairment, a specific learning disability, deaf-blindness, or multiple disabilities (34 C.F.R. §300.8). The phrase child with a disability for children aged 3 through 9 years may, at the discretion of the SEA and LEA and in accordance with §300.111(b), include a child who demonstrates developmental delays, as defined by the state and as measured by appropriate diagnostic instruments and procedures, in one or more of the following areas: physical development, cognitive development, communication development, social or emotional development, or adaptive development; and who, by reason thereof, needs special education and related services.

If the team determines that a child is eligible for special education, the IEP process begins—the IEP team meets to develop a special education plan and determine if related services are necessary. Occupational therapy evaluation data provides the IEP team with “information related to enabling the child to be involved in and progress in the general education curriculum, or for preschool children, to participate in appropriate activities” (§614(b)(2)(A)(ii)). The determination of need for occupational therapy services should not be based on evaluation alone but should be driven by the student’s educational program and annual goals.

A child with a disability who is not eligible for special education under IDEA may be eligible for services under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Using information from multiple sources, a multidisciplinary team determines if the child has a disability (as defined in Section 504) that substantially limits a major life activity.

Individualized Education Program

The IEP represents both the formal planning process and the resulting legal document that establishes the services and programs that will enable the student to participate in school activities and receive an “appropriate education.” According to IDEA (34 C.F.R. §§300.320–300.324), the IEP is a written statement for each child with a disability that outlines the student’s educational and functional needs and the supports and services required to meet those needs. It is developed, reviewed, and revised in a meeting in accordance with the guidelines of the IDEA.

The IEP team is made up at minimum of the child’s parents; one regular education teacher of the child; one special education teacher of the child; one special education provider, when appropriate; a representative of the public agency who had knowledge and qualifications; an individual who can interpret the instructional implications of the evaluation results (may be one of the other members); other individuals who have knowledge or special expertise regarding the child (e.g., related services personnel) as appropriate, and the child with a disability when appropriate (34 C.F.R. §300.321(a) and (b)(1)). Although related services personnel are generally considered “discretionary” team members (§300.321(a)(6)), if an occupational therapist formally identified as a member of a particular IEP team or if occupational therapy is being discussed at the meeting, it is fitting and desirable that the therapist attend the meeting.45

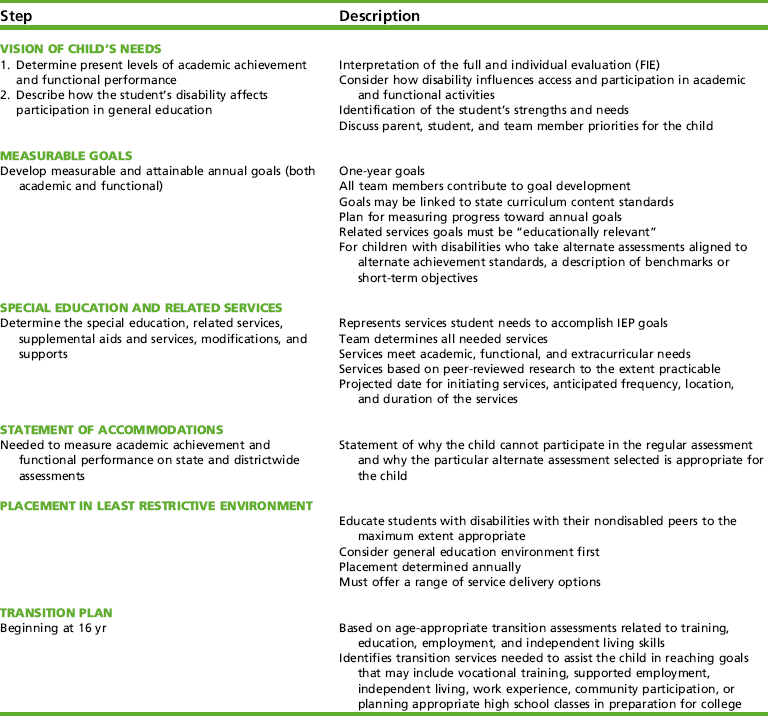

The collaborative planning procedure that guides the process of developing an IEP involves many components. The school-based occupational therapist contributes to many of those components when participating as a member of a student’s IEP team. Although the exact components may vary from state to state, depending on the special education policies and procedures adopted by the state, the following items represent at least the minimum for all states because they are mandated as general requirements by IDEA (34 C.F.R. §300.320(a))(Table 24-3).

The first steps involve interpretation of the most recent evaluation of the child, consideration of the child’s performance on any general state or districtwide assessment programs, and identification of the student’s strengths and needs. It also involves discussion with the parents, educational team, and sometimes the student regarding priorities and goals. During this initial phase, it is important to “create a team ‘vision’ about who the student is and what a student needs to succeed in school” (p. 1).49 This information is documented on the IEP as the present levels of academic achievement and functional performance and the description of how the student’s disability affects participation in general education. For a preschool student, consideration is given to whether the disability affects participation in any activity appropriate for a preschooler. Typically, all team members participate in developing this statement, which includes a summary of all evaluation results, thus giving a total picture of the student’s academic and functional performance. Occupational therapists should be ready to share evaluation results, which are included in the student’s present levels of performance. Therapists should specify how the student’s performance influences participation in the general education curriculum, including functional activities. For example, sharing the student’s time delay before initiating work, percentage of time engaged in off-task behavior, or how writing speed relates to educationally relevant performance in written expression. In the case of a preschool student, the therapist should document whether the performance results suggest problems that will affect the student’s access to typical preschool activities. Table 24-4 provides examples of educationally relevant present levels of performance and statements of need.

TABLE 24-4

Educationally Relevant Levels of Performance and Educational Need

| Present Performance Level | Educational Need |

| Forms all letters correctly in isolation | Increase speed and spacing so written words and sentences are legible |

| Highly sensitive to unexpected touch; will push other children when in line or moving through the hallways | Strategies and supports to tolerate being close to peers; accommodations to leave class early to avoid crowded hallways |

| Eyes remain fixed when reading | Accommodations and instruction to read text without skipping or rereading words |

| Desk and workspace cluttered; unable to locate assignments and homework | Learn to use an organizational system |

| Enjoys recess but tires after 5 minutes on the playground | Frequent rest breaks and strategies to understand and communicate fatigue to teaching staff |

| Has adequate skills for hands-on prevocational work experiences; personal hygiene not sufficient for work settings | Awareness and training for increased independence and carryover in self-care areas |

Data from Knippenberg, C., & Hanft, B. (2004). The key to educational relevance: Occupation throughout the school day. School System Special Interest Section Quarterly, 11(4), 1-4.

The next step involves the development of measurable annual goals (both academic and functional) designed to enable the student to have access to and make progress in the general education curriculum and meet the child’s other educational needs that result from the child’s disability (34 C.F.R. §300.320(a)(2)(i)(B)). The goals are statements of measurable and attainable behaviors a student is expected to demonstrate within 1 year. Many states are linking goals to their state curriculum content standards.44 This ensures that the goals are related directly to the learning objectives mandated by the SEA for all students. IDEA 2004 eliminated the requirement of writing short-term objectives (benchmarks) in the IEP except for children with disabilities who take alternate assessments aligned to alternate achievement standards (§300.320(a)(2)(ii). Congress opted to eliminate short-term objectives as a way to reduce paperwork and also because parents are informed of short-term progress through the use of quarterly and other periodic reports. Although short-term objectives are not required for all students receiving special education, a plan for measuring progress must be documented, specifying how the child is meeting IEP goals and when periodic progress reports will be provided (such as through the use of quarterly reports concurrent with the issuance of report cards) (34 C.F.R. §300.320(a)(2)). It should be noted that the frequency of reporting progress must be at least as often as the progress reports received by the parents of nondisabled students. The actual progress attained toward the goals must be included. Occupational therapists are responsible for measuring progress toward annual goals and objectives when they are one of the services listed to support that student’s goal. Often, several members of the IEP team share data keeping for a student’s progress toward general education goals.

Goal writing is a collaborative process and is completed at the IEP meeting with the input of all team members including the parents, and in some cases the student. Goal writing in most districts is facilitated by an online process that enables the IEP to be developed on a shared website. Student needs are prioritized and academic and functional goals are selected based on identifying skills that are needed to progress in the general educational environment. Team members, including occupational therapists, must relate their activities and recommendations to the general education curriculum and extracurricular activities. Therefore, all team members must be knowledgeable about the classroom curriculum and behavioral expectations and the state educational standards. Target behaviors are those actions and skills that students typically do or need to develop, such as participating in physical education, writing an essay, eating lunch independently, playing with friends during recess, and participating in after-school clubs.49 Although occupational therapists may identify limitations in discrete performance skills that negatively impact school participation, such separate clinical goals should not be suggested to the IEP team. Goals need to address academic achievement and functional performance. Furthermore, the occupational therapist may feel that a particular skill is a priority for a child. However, when viewing the whole child, the team may not concur. If this is the case, some negotiation among IEP team members may be needed to select the priorities for the child so that appropriate goals and objectives can be developed for the student. A description of how to develop goals is provided in Box 24-3.

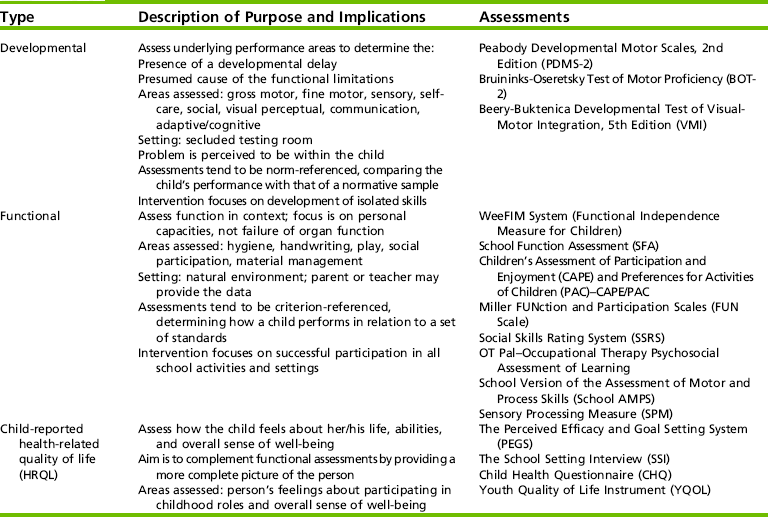

Once the IEP goals have been developed, the team determines the special education, related services, supplemental aids and services, modifications, and supports to be provided by the school. These pertain to the student’s advancement toward the annual goals and access to the general education curriculum, and participation in nonacademic and extracurricular activities. The IEP team determines if related services are “required to assist a child with a disability to benefit from special education” (34 C.F.R. §300.34(a)). “One of the most important clarifications that teams should understand is that students with disabilities do not attend school to receive related services; they receive services so they can attend and participate in school” (p. 6).34 Therefore, the role of the school-based occupational therapist is not to provide a full rehabilitation program but to support the child’s efforts within the academic environment and only if necessary.32 In general, occupational therapy services under IDEA are not provided when a student has a temporary impairment (e.g., a fractured bone) or when an impairment does not interfere with the student’s performance in school. For example, a bright first grader had mild left hemiparesis cerebral palsy. This student participated in all aspects of the educational program, including physical education, with few adaptations. The disability did not interfere with the student’s educational program. Therefore, she was not eligible for occupational therapy in school, despite the fact that she did not have the full use of her left hand (Figure 24-6).

FIGURE 24-6 A child with left hemiparesis uses a touch window on the classroom computer. Despite her left-side motor impairments, she did not qualify for related services under IDEA because she was fully functional and met all standards for kindergarten performance.

It is important, however, for the occupational therapist to effectively communicate the domain and scope of occupational therapy services to the entire IEP team so that an informed decision will be made regarding service provision. On the basis of evaluation findings, the occupational therapist articulates to the IEP team recommendations regarding the need for occupational therapy services to enable the child to benefit from his or her education. The IEP team makes the decision based on the student’s educational program and unique needs. “Occupational therapy services are appropriate when the unique skills and expertise of the occupational therapist are needed to support the priorities identified by the team” (p. 78).40

If the occupational therapist is to provide services to the student, it must be noted specifically in this section of the IEP along with the projected date for initiating services and anticipated frequency, location, and duration of the services. Documentation of the type of occupational therapy service delivery should ensure that a range of service approaches be available to the student—both direct (to the child) and indirect (on behalf of the child) services. Based on the individualized needs of the student, direct intervention may be necessary during one week, whereas indirect consultation provided to the teacher on the student’s behalf may be useful during the next week. In addition, flexibility in documenting time and frequency is also recommended (i.e., 2 hours per month or 1 hour per grading period), rather than specifying set weekly visits. “For example, a high school student may need 3 hours the first month to set up a prevocational program and to train the instructional team. Much smaller periods of time, such as 1 hour per month, may be needed when the OT returns in subsequent weeks to evaluate the effectiveness of the program and revise as needed” (p. 3).68 Recommendations for duration of services, generally written as beginning and ending dates, and location of services (e.g., cafeteria, classroom, playground, hallways) must also be specified.

The occupational therapist may also participate in suggesting appropriate modifications and support based on the assessment results. As an example, the occupational therapist may suggest limiting the amount of information on the student’s worksheets because of a student’s poor visual figure-ground processing. If the team were to agree to the recommendation, it would be documented on the IEP. Similarly, a statement of any individual appropriate accommodations that are necessary to measure the academic achievement and functional performance of the child on state and districtwide assessments consistent with §612(a)(16) of the IDEA, must also be determined by the IEP team.63 In addition, if the IEP team determines that the child must take an alternate assessment instead of the regular state or districtwide assessment of student achievement, a statement of why the child cannot participate in the regular assessment and why the alternate assessment is appropriate for the child must be documented. The occupational therapist may contribute in the team discussion about appropriate testing modification. For example, the occupational therapist may suggest testing a student with sensory sensitivities in a separate room. For a student with motor limitations and difficulty with handwriting, the occupational therapist may suggest using an electronic text format of the test that would allow the student to use a keyboard. Each state determines the allowable modifications.

Once the IEP team has determined what the child needs in terms of special education services, the team can determine where the services should be provided. Placement decisions are made annually based on where the IEP team has determined that the student’s IEP goals can be met.88 In accordance with LRE as defined in the IDEA, children with disabilities are required to be educated with their nondisabled peers to the maximum extent appropriate (34 C.F.R. §300.114(A)(2)(i)). This means instruction must be available in a continuum of placement options ranging from regular education classrooms to specialized classrooms, residential facilities, and home-based programs. Removal to separate classes is permissible only “if the nature or severity of the disability is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily” (34 C.F.R. §300.114(A(2)(ii)). On the basis of student’s IEP goals, the team should consider whether supplementary aids and services provided within a general education classroom would allow the student to receive an appropriate education or whether such a placement would impede her or his learning and/or the learning of other students. If a child will not be participating fully with children without disabilities in a regular classroom, in nonacademic and extracurricular activities, there must be an explanation on the IEP as to the extent the child will not be participating.

Finally, once the child turns 16, or before that if determined appropriate by the IEP team, the IEP must include a written transition plan. Transition is the process of beginning to plan for the student’s completion of education and postgraduation life. This plan is based on age-appropriate transition assessments related to training, education, employment, and, when appropriate, independent living skills. The transition plan should include a statement of the services needed and should clearly connect the student’s goals for after-school life and a planned course of studies in high school. The transition services (including courses of study) needed to assist the child in reaching those goals may include vocational training, supported employment, independent living, work experience, community participation, or planning appropriate high school classes in preparation for college. When the student reaches age 16, a statement of interagency responsibility is also included in the IEP. Occupational therapists may be involved in this process by providing input on the student’s functional capabilities related to vocational planning and community living.

The development of IEPs can be a daunting task because of the changing legal requirements with each reauthorization of IDEA and the changing face of each IEP team. Occupational therapists need to develop the skills to work effectively with a multitude of parents and professionals. Although IEP teams have characteristics that make them like other types of working teams, there are also unique characteristics to IEP teams that need to be considered by the various members. It has been suggested that IEP teams differ from other teams in the following ways20:

1. There is a legal framework of required relationships among partners. Federal, state, and local laws and policies spell out in some detail who must participate and what they must do. This is especially true for the school district, which has many legal responsibilities regarding the education of students with disabilities.

2. The team members share both responsibility and accountability for the success of the student in meeting his or her goals.

3. The process is “results-oriented,” meaning that what matters is not how happy everyone is with the process, but the success of the student’s educational program.

As a result of these differences, development of the IEP involves high levels of collaboration and, at times, negotiation among and consensus building by all team members. The written IEP document is developed in a formal meeting, so the contents reflect the consensus of the team. Parents and other team members, including occupational therapists, contribute equally to the process. The team members discuss the student’s strengths and needs and then develop goals, outcome statements, and plans through a collaborative process. By developing the student’s IEP using a team process that includes the family, the team assures the family that the IEP belongs to the student and is unique to that student’s educational needs.

Occupational Therapy Services

Once the IEP team agrees that occupational therapy services are necessary to support the student’s goal achievement, the occupational therapist can propose how to provide services. IDEA 2004 recognizes that services and supports need to be delivered in different ways for children with disabilities to benefit from education. The nature of occupational therapy practice in schools is complex because of the considerable variability in service provision including the target of services (who), types of services and how these are delivered (what and how), scheduling of services (when), and place of delivery (where).

Although the primary “client” is the child, intervention may also target general and special education teachers, other related service providers (e.g., music therapists), administrators (e.g., principals), and paraprofessionals involved in supporting the child’s IEP.14,41 Intervention with a variety of “clients” occurs as a direct result of employing a range of service delivery options. Traditionally, services in schools were provided directly to the child in an isolated therapy setting similar to clinical practice. This type of service delivery involves primarily one “client” —the child. However, IDEA does not mandate any one service model and allows for a range of services including those provided directly to the child (direct), on behalf of the child (indirect), and as program supports or modifications for teachers and other staff working with the child (indirect) (§614(d)(IV). Services provided on behalf of the child or to provide program supports, require the therapist to work directly with a range of other “clients” including regular and special educators, parents, or paraprofessionals. For instance, a therapist may consult with the classroom teacher to help modify instructional materials and methods for a student with physical or organizational needs requiring close interaction with the teacher. Decisions about how occupational therapy services are made based on the child’s needs, the educational program, and expected outcomes.14,67 Examples of the range of services provided by an occupational therapy practitioner are working individually with children, consulting with the teacher about a student, co-leading a small group in the classroom, providing an in-service training program for educational personnel, and/or working on a curriculum or other school-level committee.77 For example, an occupational therapist may co-lead groups with a special education teacher as discussed in Box 24-4 (Figure 24-7).

In addition to determining the most effective range of services for a child, therapists are also encouraged to provide services in a flexible manner depending on the student’s stage in the therapy process and particular needs. For example, the occupational therapist may choose to work directly with a student for several weeks to teach the student how to implement the ALERT Program of Self-Regulation,85 followed by consultation with the teacher or paraprofessional to ensure generalization of the strategies in the classroom.

Another factor influencing occupational therapy service provision is a consideration of the different approaches to intervention—to promote health, prevent disability, restore function, adapt/modify task, or maintain function. Traditionally, occupational therapy’s role in the schools has focused on restoring function and adapting the task or environment to promote participation for children with disabilities. However, the reauthorization of IDEA and NCLB has created new opportunities for occupational therapy to contribute to health promotion and prevention in all children. The shift to preventive models of service delivery will likely broaden the definition of “client” for occupational therapists to include all children in general education.

Given the variability, provision based on the unique needs of each child given the who, what, when, where, and why determining needed services, occupational therapists must enter school practice aware of this complexity and the personal and interpersonal skills required to succeed in such an environment. For example, therapists need good organization and time management to develop and maintain their work schedules given the variability of school settings and types of service needs of their particular caseload. Therapists must be as effective and efficient as possible in meeting the complex demands of their job. Providing group interventions to children with and without disabilities, for example, offers an opportunity to serve several children at once and allows the therapist to assess and promote social participation among the group members at the same time.

In addition to the required documentation for the IEP and follow-up progress reports, routine documentation of service provision is not mandated by IDEA. The occupational therapist should develop a method of documentation of services to record the student’s progress toward goals, response to interventions, other changes in performance, and strategies that were promising or ineffective.14

Scientifically Based Instructional Practices

School-based occupational therapists apply a wide array of intervention methodologies based on a variety of theoretical frames of reference (e.g., sensory integration, motor learning, behavioral, biomechanical). According to IDEA 2004, and consistent with NCLB, schools are required to use “qualified personnel” and “ensure that such personnel have the skills and knowledge necessary to improve the academic achievement and functional performance of children with disabilities, including the use of scientifically based instructional practices, to the maximum extent possible” (§601(c)(5)(E)). Scientifically based practices refer to those that have a strong research base, indicating that the interventions will most likely produce the targeted outcomes for students with disabilities. In a recent evidence-based review of occupational therapy school-based practice, Swinth et al. reviewed a number of one group cohort and single-subject design studies; however, a limited number of reports of controlled trials were found.79

Integrated Service Delivery

Although IDEA does not specify service delivery types, it does indicate that all related services be provided in the least restrictive environment to foster participation in the general education curriculum. Because occupational therapy services support both academic goals (e.g., handwriting and literacy) and functional goals (e.g., organizing materials, self-feeding during lunch), the service context can include a wide range of natural settings including classroom, playground, cafeteria, restroom, and hallways. In addition to promoting the integration of students with disabilities with their nondisabled peers, interventions provided in natural settings during daily routines are more likely to be applied consistently.2 Because therapists must work closely with teachers to identify intervention opportunities that have the greatest contextual application and generalizability, consultation should be a part of each therapy visit. “Although therapists may pull students out of the classroom for brief periods to explore strategies or to introduce a new skill, time away from instruction is minimized” (p. 3).68

Full inclusion refers to a child’s access to and participation in all activities of the school setting. Supports and adaptations are provided as needed to enable the child with disabilities to participate in activities with his or her peers. These services are typically provided in the child’s neighborhood school. For example, Josh, a child with spina bifida and mild learning disabilities, attends his local, home elementary school in a rural community. Josh is in the regular classroom for the entire day, with a classroom aide assisting him with self-care tasks as needed. The school’s special education teacher helps the classroom teacher in adapting Josh’s assignments when needed.

Inclusion can consist of a variety of learning options. A student may spend a portion of the day in a resource room and a portion in regular education classes. For instance, Brian, who is in the sixth grade, participates in the regular-education classroom for all of his classes except math and reading. For these subjects, he receives instruction from the resource room teacher because his performance in these classes is significantly lower than that of his peers, and he requires a special curriculum to progress in these areas.

Modifications and accommodations are made to support Brian’s learning needs so that he can participate in learning activities. Often, the regular classroom teacher groups students for science and social studies projects so that each of the students is given a task that he or she can manage. Because Brian has difficulty with manipulation, the teacher gives manipulation tasks to the other students in the group and often selects Brian to search the Internet or oversee final-project assembly. Tests are read to Brian, and he is allowed to dictate his answers. Greg attends full-day, inclusive kindergarten with occupational therapy, physical therapy, and special education supporting his participation in the regular education curriculum (Figure 24-11).

FIGURE 24-11 Academic and behavioral tiered levels of intervention. Data from National Association of State Directors of Special Education & Council of Administrators of Special Education [CASE]. [2006]. Retrieved from http://www.nasdse.org/Portals/0/Documents/Download%20Publications/RtIAnAdministratorsPerspective1-06.pdf.

Of note, effectively integrating therapy into the general or special education classroom using both direct and indirect services requires an important set of knowledge and skills. Integrated therapy models imply high levels of collaboration, therapy sessions embedded within the classroom, and working directly with the teacher (e.g., co-teaching). When providing indirect services, occupational therapists use consultation and training of others to implement intervention strategies.

In an integrated therapy model, the practitioner provides intervention in the child’s natural environment (e.g., within the classroom, on the playground, in the cafeteria, on and off the school bus) emphasizing nonintrusive methods. The therapist’s presence in the classroom benefits the instructional staff members, who observe the occupational therapy intervention. Working within the classroom benefits the therapist in gaining a thorough understanding of the classroom environment and the behavioral and achievement expectations of its students. This integrated model of therapy also allows the student to participate in the classroom activities, with therapy support. Integrated therapy ensures that the therapist’s focus has high relevance to the performance expected within the student’s classroom. It also promotes the likelihood that adaptations and therapeutic techniques will be carried over into classroom activities.89 Giangreco described an integrated therapy model as one in which teams that include related services (1) establish a shared set of goals and objectives based on family priorities and participation in the general curriculum; (2) support the teachers’ goals; and (3) provide a just-right level of related service support with guidance from the team.33 Occupational therapists are responsible for ensuring that their services are integral to the education program.70

Educational proponents of inclusion who support integrated models of therapy suggest that pull-out services are appropriate only when students need to work on a skill that is far below the tasks presented to other students in the classroom or when the intervention activities cannot appropriately occur in a typical classroom (e.g., therapeutic use of equipment such as a swing). When intervention activities create a distraction that prevents other students from learning or the teacher from teaching, they should be performed outside the classroom.29 McWilliam cautions that pull-out therapy is less effective than integrated services.56

One method to promote integrated services is block scheduling, in which therapy sessions are scheduled in longer blocks of time than usual, so that the therapist has time to work within the classroom setting during the times when meaningful activities occur.71 The overall total therapy time in a given month may remain the same, but the students are seen every other week rather than weekly. If several students are seen in the same classroom, the therapist may continue weekly services for each by combining the students’ time. The therapist remains in the classroom for the entire morning or afternoon and moves between students during each of the activities presented. Block scheduling gives the therapist opportunities for co-teaching or team teaching. In this method, a therapist and a classroom teacher jointly design and implement learning experiences within the classroom setting. The therapist’s time is scheduled for the co-planned activities, rather than for individual sessions.

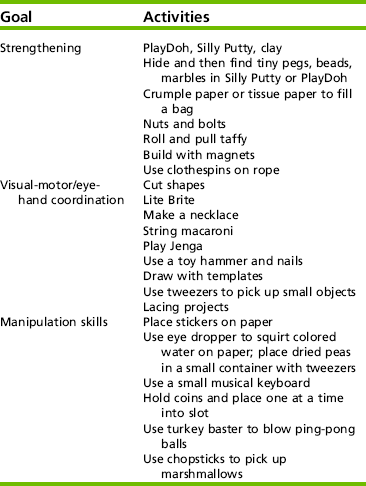

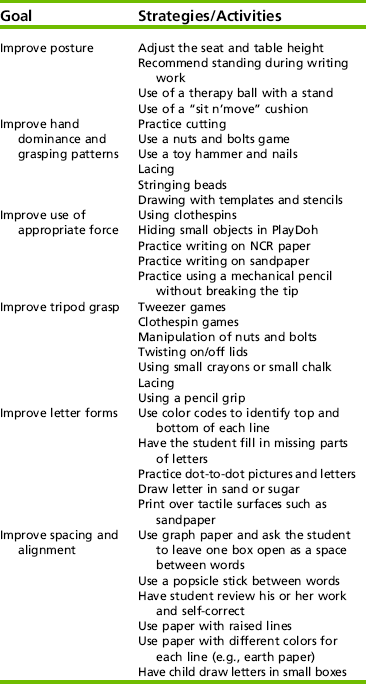

Not only do the targeted students benefit from the interventions, but the other students in the class also benefit from the multidisciplinary input. For example, the classroom teacher and occupational therapist may co-plan a handwriting session. The session may include both the third-grade curriculum and practice of the mechanics of handwriting. Other examples of activities to promote fine motor skills related to school functions are listed in Table 24-5. Activities to improve handwriting skills are listed in Table 24-6.

TABLE 24-5

Recommended Fine Motor Activities to Improve School Functions

Adapted from Fine/Visual Motor Activities and Developed by School Therapists, compiled by Deanna Iris Sava, 2004. Retrieved on April 28, 2004, at http://www.otexchange.org. Fine Motor List.

TABLE 24-6

Activities to Prepare Children for Writing

From Amundson, S. (1999). Tricks for written communication. Homer, Alaska: OTKids, Inc; and Ginsberg-Brown, C., & Schotzer, T. (2004). Pre-referral form: Intervention strategies. Retrieved on April 28, 2004, from http://www.otexchange.org.

In integrated services, the occupational therapist may plan a program that involves specific activities for a student, to be carried out with the help of other personnel (e.g., teaching assistant, aide). To enable the person who is chosen to implement the program, the therapist uses modeling and coaching as the child attempts the activities in his or her natural routine. The therapist may give the teacher materials helpful for implementing the intervention (e.g., tongs to practice dynamic grasp, sensory bag, tweezers, clothespins) or help to adapt the environment so that the child can participate (e.g., establish a sensory corner, set up a tent, obtain bean bag chairs, therapy balls, prone standers). Regular contact is necessary to update programs and supervise the manner in which the activities are implemented. Examples of activities that the occupational therapist may initiate and then help staff to implement are positioning a student for written activities and implementation of assistive technology (e.g., adapted keyboard).

When working with students in a classroom, the therapist needs to have a clear understanding of the classroom expectations. This includes knowledge of classroom rules, routines, and dynamics, and knowledge of the general education curriculum and special education adaptations. Each classroom teacher has unique teaching and classroom management styles. Intervention techniques conducted in the classroom that may be acceptable to one teacher may not be acceptable to another teacher; they may even be considered intrusive.

Griswold recommended that therapists offer interventions that fit the existing classroom structure and culture.37 For example, a teacher who values child-directed learning and hands-on learning centers may respond well to a therapist’s suggestions for activities to be included in the learning centers (Figures 24-8 and 24-9). Another teacher who uses a strong teacher-directed classroom may prefer to engage in team-teaching activities with the therapist.

FIGURE 24-8 The occupational therapist may help the teacher establish learning centers for sensory exploration.

FIGURE 24-9 A fine-motor learning center may include hanging up T-shirts and pictures using clothespins.

Therapists also need to be sensitive to the regular education schedule and not disrupt the child’s and the classroom schedule, if possible. Teachers may prefer to have the therapist in the classroom at certain times or on certain days. These preferences should be negotiated with the teacher before intervention, and attempts should be made to schedule times for providing services to the child that coincide with targeted goal areas. For example, handwriting interventions can be integrated into the student’s language arts time and keyboarding skills can be addressed during the student’s computer or language arts class.

The support that an occupational therapist provides within the school should make both the child and the teacher’s jobs easier, without placing unreasonable burdens on either the student or the teacher. Although the teacher’s and the therapist’s jobs are to support the child’s role as a student, at times there is a mismatch between what teachers (and parents) want and what occupational therapists want. Conflicts in point of view can be minimized or avoided if consistent communication is maintained between teachers and support personnel. The responsibility for maintaining open pathways of communication rests equally on all members of the team.

Consultation

“The key to effective collaboration in educational settings is learning to use one’s professional knowledge and interpersonal skills to blend hands-on services for students with team and system supports for families, educators, and the school system at large.”41 School-based collaboration involves an interactive team process among students, families, teachers, and related service providers to enhance the academic achievement and functional performance of all students.41 Occupational therapists are challenged to skillfully blend their role in providing direct hands-on services for students with team and system supports. In consultation, the therapist and the teacher (or other professional) form a cooperative partnership and engage in a reciprocal problem-solving process. One of the goals of consultation is to enhance the skills of the consultee and to improve the targeted performance area of the student. At times, the focus of consultation is on implementation of a specific program for the student. At other times, the focus is more directly on enhancing the teacher’s knowledge and skills. Although occupational therapists practicing in schools must learn how to function within an educational model, it is also important to acknowledge therapists’ medical background and knowledge base. The occupational therapist’s translation of medical information can be used by the multidisciplinary team to make meaningful decisions and provide appropriate services.14

To provide effective consultation, the occupational therapist needs (1) in-depth knowledge and understanding of the problem, (2) knowledge of appropriate interventions, and (3) effective communication and interaction skills. The occupational therapist also must thoroughly understand the educational system so that the intervention strategies that he or she recommends are feasible within the system. Understanding the educational system also helps the therapist to ensure that appropriate classroom and student supports are identified. An understanding of the system and school policies is particularly important when the therapist identifies curricular or environmental modifications that would benefit the student’s educational program.

Collaborative consultation emphasizes that the consultant and the consultee have equally important roles. The parties agree on and work toward common goals to make decisions. Although the consultant and the consultee work jointly on an equal basis, they have different roles.90 The consultant structures and guides the overall process, whereas the consultee provides information about the problem and the expectations. The consultee generally (1) retains responsibility for the student, (2) judges treatment acceptability, and (3) implements the intervention. Because the consultee implements the intervention, it is important that he or she can accurately apply it, recognize the expected or desired response, and judge when modifications to the strategy are needed. It is the responsibility of the consultant to ensure that the consultee is well informed and sensitive to the issues. Therefore, the consultant’s responsibilities include (1) presenting a new or more in-depth understanding of the student’s problem, (2) identifying and presenting interventions for possible implementation, (3) assisting in selecting the most appropriate and realistic solutions, and (4) developing an evaluation plan. These differing responsibilities suggest that a complementary, interdependent working relationship is needed.90

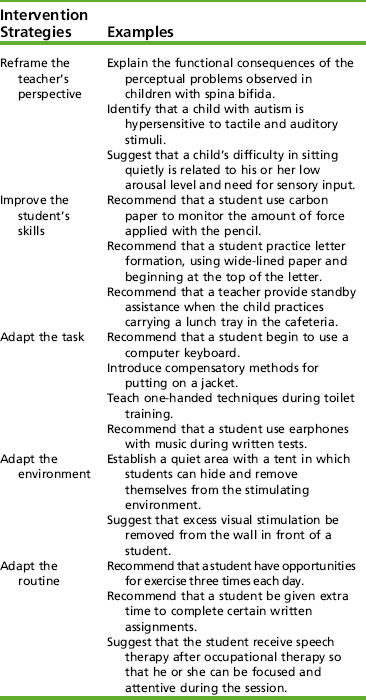

Hanft and Place described types of decision making required in the consultation role.41 The most appropriate intervention strategies are selected first. These decisions are based on (1) the student’s and teacher’s goals, (2) the student’s problems, (3) the consultee’s skills and interaction style, and (4) the flexibility and constraints of the environment. Examples of typical strategies recommended by occupational therapists are listed in Table 24-7.