Psychosocial Issues Affecting Social Participation

1 Understand the dynamic interaction of emotional, cognitive, neurobehavioral, and environmental factors as they influence aspects of occupational performance through the course of typical development during infancy, childhood, and adolescence.

2 Explain means of promoting the psychosocial wellness of infants, children, and youth within natural contexts.

3 Identify the diagnostic hallmarks and contributing factors of common mental health conditions, and relate these to the occupational performance of children and adolescents.

4 Understand the continuum of services available to children and youth with psychosocial disorders.

5 Explain the variety of service delivery models and frames of reference used by occupational therapists in psychosocial settings.

6 Define the roles of occupational therapists who provide services to children and youth with psychosocial disorders, as well as those of other team members.

7 Understand evaluation and intervention processes related to the special needs of children and youth whose occupational performance has been affected by psychosocial problems.

The promotion of the child’s social participation within the contexts of family, friendships, classmates, caregivers, and teachers is an essential domain of occupational therapy in all practice settings.5,50,56,135,181 Achievement of developmental milestones and occupational goals is the result of continuously evolving interactions between aspects of the individual child and the environmental contexts that envelop him or her. Social relationships constitute a critical chunk of that environment; the mutual influences of the individual and his or her social contexts help determine the child’s quality of life and participation in those social contexts.

This chapter is organized as follows: It (1) describes dynamic aspects of healthy psychosocial development within the child and the family, (2) outlines common causes of psychosocial problems in children and adolescents and their implications for occupational performance, (3) describes the roles of occupational therapy practitioners and other team members within a variety of intervention settings, and (4) introduces selected evaluation and intervention methods, including intervention goals for common psychosocial needs.

The unifying frame of reference for this chapter is the person-environment-occupation (PEO) model.106 The PEO model emphasizes the dynamic interaction between the individual and various aspects of the environment and how these interactions influence occupational performance. “Person” factors include qualities of the individual such as gender, age, developmental levels, skills, preferences, and values. “Environment” factors encompass the social, cultural, economic, political, and physical contexts that the child functions within. Person and environment factors are viewed as reciprocally influential and as directly relevant to the child’s occupational performance. “Occupations” are the everyday tasks and activities that an individual performs, ranging from very basic actions, such as eating and using the toilet, to highly sophisticated activities, such as working a calculus problem, flirting with a classmate, or rollerblading. Appreciating and understanding the elements of the PEO model and their potential for dynamic interaction enable occupational therapists to approach intervention holistically and effectively.

TEMPERAMENT: A “PERSON” FACTOR THAT INFLUENCES AND IS INFLUENCED BY THE ENVIRONMENT

Children vary in their development of interests, habits, talents, and social competence. Standardized pediatric tests reveal variations among children in the rate and sequence of their acquisition of motor, language, and cognitive skills. Curiosity about these differences among children has inspired decades of research. Chess and Thomas were among the first scholars to study children’s styles of responding to various experiences and carrying out activities such as sleeping, eating, and exploring objects.158 Their work developed the concept of temperament. Temperament refers to a collection of inborn, relatively stable traits that influence how individuals process and respond to the environment and that contribute to the development of personality and everyday functioning.154 Chess and Thomas identified nine basic characteristics of temperament, which remain useful today. These are (1) activity level, (2) rhythmicity (i.e., the degree to which the child’s patterns of sleeping, eating, and play are predictable), (3) approach to or withdrawal from novel situations, (4) intensity of emotional responses, (5) sensory threshold, (6) mood (general emotional state), (7) adaptability, (8) distractibility, and (9) attention span and persistence.33 Temperament characteristics are not considered to be inherently good or bad, and they are not under the control of the child or the parents. However, behaviors arising from temperament traits may be more or less adaptive or pleasing, depending on the context. Children whose temperament style approaches extremes on any of the nine parameters may have more difficulty negotiating the social and emotional demands of childhood. The environmental demands and expectations must always be considered, however, when attempting to predict the effects of temperament on occupational performance. Research indicates that the assessment of each child’s temperament is influenced by the observer’s point of view and that the determination of function or dysfunction has much to do with the situational compatibility with the family and other social environments.171

Chess and Thomas were interested in learning about the influence of personality characteristics on the parent-child relationship and the child’s development.35 They applied the concept goodness of fit (from statistics) to interpersonal relationships. When the expectations of persons important to the child are compatible with the child’s temperament, there is a good fit (Case Study 13-1). When the child’s temperament is at odds with parental expectations, mutual distress may result. Although Chess and Thomas focused on parent-child fit, other research has supported the findings in teacher and peer relationships.90,91

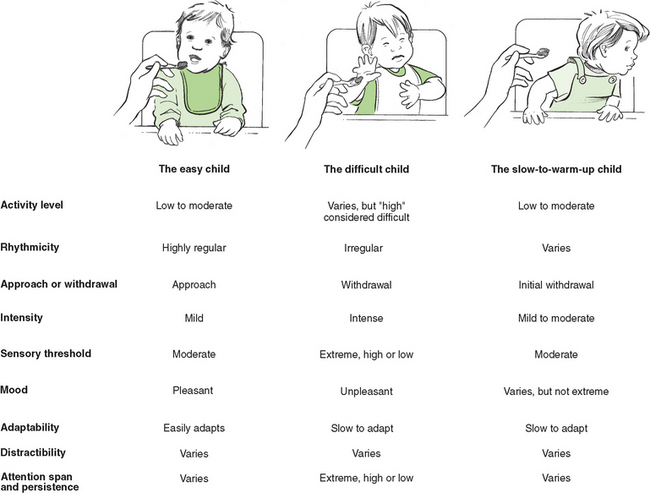

Chess and Thomas (1983) identified three common patterns of temperament from the nine temperament traits described above. They gave these combinations the labels easy child, difficult child, and slow-to-warm-up child (Figure 13-1). The easy child is positive in mood and approach to new stimuli. This child is calm, expressive, malleable, and has a generally low to moderate activity level. Children characterized as easy tend to adapt effectively to changing situations and demands. The difficult child is at the opposite end of the temperament spectrum. Characteristics that characterize this style are a negative mood and approach, slow adaptability, a high activity level, and high emotional intensity. Extremes of sensory threshold often occur among children with a difficult temperament pattern. A slow-to-warm-up child demonstrates mild-intensity negative reactions to new stimuli in combination with slow adaptation. These children require repeated exposures to new environments before they feel comfortable. Once a slow-to-warm-up child has established a routine, he or she usually functions well, but transitions are often problematic for children of this temperament type. Research has linked various temperament characteristics to parental stress in child-rearing,34 certain psychiatric disorders in adulthood,87,129 adolescent substance abuse,179 and disruptive behavioral disorders.68 A growing body of research supports the notion that temperament, although inborn, is not unchanging across a child’s lifespan. Experiences and environmental circumstances such as the interpersonal styles of the primary caregivers have been assessed as having potentially significant influence on the developing child’s temperament style.17 These findings suggest that therapeutic intervention can be helpful in situations lacking goodness of fit between child and caregiver.

Occupational therapists often see children who are in distress and whose behavior is disruptive or upsetting to the family. Practitioners can help parents, caregivers, teachers, and children to explore and understand their temperaments and learn to predict when behavior may not match environmental demands (e.g., a very active child at the theater, a slow-to-warm-up child beginning a new school year). This perspective may decrease frustration and increase the possibility of organizing environments and activity demands to promote goodness of fit and successful occupational engagement.

ATTACHMENT: A DYNAMIC INTERACTION OF BIOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT

A child’s neuromaturational progress greatly influences social participation. The healthy, full-term infant is biologically prepared to participate in interactions with a nurturing and consistent caregiver, resulting in a loving attachment that is essential for healthy development.11 As the infant nurses, cuddles, gazes with fascination at her mother’s face, and responds to comforting, emotions result that will become the foundation of the baby’s self-concept and a safe base from which to explore the world.159 Simultaneously, the mother experiences hormonal and neurochemical effects from interacting with her infant that promote feelings of well-being, protectiveness, and love for her baby.77 Healthy attachment occurs when the caregiver and infant consistently interrelate in such a way that the infant develops confidence that the needs will be met and that he is safe and cared for.16,116 Many experts contend that the quality of early attachment influences the capacity to form relationships later in life.55,73,178 Some researchers are studying the influence of early attachment experience on neurodevelopment itself at the biochemical and cellular levels.58,101,115 Thompson asserts that the quality of early relationships is “far more significant on early learning than are educational toys, preschool curricula, or Mozart CDs” (p. 11).159

Traits and behaviors of the parent and the child interact dynamically within environmental contexts to determine the quality of attachment that develops; each party is simultaneously influencing and influenced by the other and by other features of the environment.60 Researchers have identified four patterns of attachment behavior between parents and infants: secure, avoidant, resistant or ambivalent, and disorganized/disoriented.2,117 These are illustrated in Table 13-1.

TABLE 13-1

Patterns of Attachment in Infants and Parents

| Attachment Style | Characteristic Caregiver Behavior | Characteristic Infant Behavior |

| Secure | Emotionally available, responsive to infant’s emotional and physical needs in a timely, consistent, and effective manner | Seeks proximity to parent, but as mobility develops explores the immediate environment; demonstrates mastery motivation and self-confidence; misses parent on separation, but easily comforted on parent’s return |

| Avoidant | Emotionally unavailable, typically not adequately responsive to infant’s communications of need | Avoids parent; emotionally blunted; interacts with objects in the environment rather than with the parent |

| Resistant or ambivalent | Inconsistently available and responsive to infant’s communications of need; caregiving style is determined by parent’s moods and is an unpredictable combination of adequate and inadequate responses | Is clingy and preoccupied with the parent; does not actively explore the environment; is difficult to comfort after separation; mood may be angry or passive |

| Disorganized/disoriented | Highly anxious or threatening toward the child; does not respond effectively or appropriately to infant’s communications; may be abusive or psychotic | Is disorganized or disoriented when interacting with the parent; displays approach-avoidance behaviors including staring and “freezing,” clinging, or huddling on the floor |

Parent-child attachment relationships continuously change in relation to the child’s and the parent’s stages of development and changing environmental circumstances.144 As the infant becomes mobile and then develops language and self-care skills, the caregiving style of the parent adjusts accordingly, and the attachment relationship is altered. Attachment patterns may also be influenced by environmental factors such as the loss or addition of family members. Adjustments in attachment continue throughout the child’s developmental course, and in the best circumstances the positive reciprocity initiated early in infancy will be maintained throughout.

Understanding that patterns of attachment between children and their parents can change implies that attachment is a process that can be influenced.11 This notion is supported by research with high-risk infants and mothers who received intervention to promote healthy attachment through three home visits focused on teaching mothers how to observe and respond effectively to their infants’ behaviors.168 The group of 50 receiving the training developed significantly more secure attachments than did those in the control group. These effects from interventions to promote attachment have been found in other studies as well.40,169

Many infants, children, and adolescents served by occupational therapists have neurodevelopmental problems. Children who have intrinsic difficulty with receptive and/or expressive communication, sensory processing, or motor performance have a different social experience than do those who are developing typically.142 Difficulty with feeding, an inability to establish regular patterns of activity and sleep throughout the day and night, resistance to cuddling, and other behaviors common to infants with neurologic dysfunction are incompatible with easy attachment, and may place the process at risk. Environmental factors such as a parent’s long hours of work can limit the time available for child-focused interaction, potentially interfering with the attachment process. Likewise, a parent whose behavior is anxious, irritable, emotionally disengaged, or who has difficulty interpreting and responding to the child’s communications cannot fully participate in reciprocal interaction. When such behaviors are frequent, attachment is at risk. Occupational therapists can support healthy interaction between caregivers and children by understanding this essential process, educating parents about their child’s development and communication style, and helping them to generate solutions for problems that inhibit strong attachment formation. They can help families identify causes of stress in their daily and weekly routines and structure solutions to address them. These could involve prioritizing goals, working together to get tasks completed more efficiently, and making mindful choices about how to use time to improve quality of life and family relationships.

CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT: PROBLEMS WITH THE PARENT-CHILD RELATIONSHIP AND ENVIRONMENT

At its most extreme, inadequate attachment formation between a parent and a child can be a factor in the abuse or neglect of the child. This is a common problem for children and families, affecting at least 905,000 American children in 2006.166 Nearly 8% of the victims of child abuse or neglect had diagnosed disabilities. The Federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), (42 U.S.C.A. §5106g), as amended by the Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003, defines child abuse and neglect as follows:

• Any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation; or

• An act or failure to act which presents an imminent risk of serious harm.

Child abuse has been categorized as neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, medical neglect, or “other” maltreatment; the various forms of child abuse may occur in combination.

• Neglect is defined as the withholding of nutrition, shelter, clothing, medical care, such that the child’s health is endangered. Undersupervision and abandonment are included in this category. This is the most common form of child abuse, accounting for about 64% of reported cases.

• Physical abuse affects about 16% of victims. This type of abuse includes punching, shaking, kicking, biting, throwing, burning, and other forms of injurious punishment.

• Sexual abuse is estimated to occur at a rate of about 9% and includes any seduction, coercion, or forcing of a child to observe or participate in sexual activity for the sexual gratification of a more powerful individual.

• Medical neglect is a failure by the caregiver to provide for the appropriate health care of the child although financially able to do so, or offered financial or other means to do so. This kind of maltreatment affects 2% of the reported cases.

• “Other” types of maltreatment constitute 15% of the reported cases. These include emotional abuse, such as the withholding of affection, chronic humiliation, threatening harm to the child or those he or she cares about, and criticism. Abandonment and congenital drug addiction also fall under this reporting category.166

Developmental and psychological outcomes that have been associated with childhood abuse include traumatic brain injury, depression, substance abuse, posttraumatic stress disorder, learning disorders, conduct disorders, and personality disorders.9,22,53,78,83,85,103 These problems can have long-term occupational consequences, including the increased risk of involvement in violent and nonviolent crime and of not completing high school.104 Most tragically, approximately 1530 children died from the effects of abuse or neglect in 2006.166 Clearly, such pathology is incompatible with healthy family functioning.

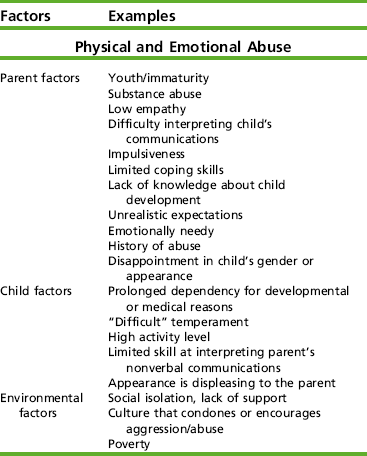

Attachment patterns between parents and children are the result of a dynamic interaction of factors related to the child, the parent, and the environment. Risk factors for child abuse and neglect have been identified in these three arenas (Table 13-2). No single factor is consistently associated with child abuse. The more risk factors present and the more severe each of these is, the higher the risk of abuse and neglect within a family.

A child’s level of risk decreases with age, with infants suffering the highest rate of abuse.166 Disability increases the risk of child maltreatment. The incidence of abuse and neglect may be as high as 3.4 times greater for children with disabilities than for those without.157 Disabilities that have been associated with an increased risk of maltreatment include behavioral disorders, communication disorders, cognitive disabilities, physical impairments, and craniofacial anomalies.46,84,157,173,176 Any condition that prolongs a child’s dependency or stimulates parental rejection adds to the risk of abuse or neglect. For example, having a “difficult” temperament or being born prematurely increases risk.59,153 Most of the young clients seen by occupational therapy practitioners have delayed development in one or more areas and are, as a group, at increased risk for abuse and neglect.

Environmental factors interact dynamically with features of the child to affect the levels of risk for abuse and neglect. Certain qualities of the parents (particularly the mother, who is usually the primary caretaker) have been identified as risk factors. These include having a personality that is characterized by immaturity, a history of having been abused, egocentrism, impulsivity, and alcohol or drug abuse.131,149,184 Characteristics of the larger community may further contribute to environmental risk factors. Poverty has been shown to correlate positively with increased rates of child abuse and neglect.44,150 Social isolation is a powerful risk factor, placing children in single-parent families at significantly higher risk for abuse than those in two-parent families.82 Communities with high crime rates present a combination of a cultural acceptance of aggressive behavior, high levels of economic distress, and the social isolation that results when residents are fearful to step out onto the street.

Although poverty and a parent’s troubled background may increase the likelihood of child abuse, high levels of social integration and community morale appear to be mediating factors that can reduce its incidence.61 Successful intervention and prevention programs address family and community needs for safe and enjoyable places to gather and engage in meaningful occupation.174 A meta-analysis of abuse prevention and family wellness programs indicated that the most effective programs supported parents by using a strengths-based, empowerment approach. Successful programs continued over 6 months and provided at least two sessions per month.113 Occupational therapists have opportunities to intervene with individuals and families through direct service, program development, consultation, and administrative roles.

Children who are experiencing physical abuse and/or neglect may bear outward signs of this, and therapists should always observe for bruises, cuts, or other injuries, or behaviors that may reflect pain. The appropriateness of the child’s clothing for weather conditions and fit should be noted over time. This is not to assess fashionableness but adequacy. The occupational therapist asks the child about his or her eating and sleeping habits and activities through the day when at home, asks about how the adults at home respond to children’s misbehavior (e.g., “What kinds of things do you do that get you in trouble sometimes?” “What happens then?”) Given gentle encouragement, some children will describe inadequate or unsafe situations. School-based personnel should observe what the child has brought for lunch or how the child responds to food that is offered; a child with too little to eat at home may hoard food or eat more than is typical. Socially, children from abusive homes may behave in a variety of ways that reflect individual temperaments and coping styles. Behaviors may range from being withdrawn and guarded to acting intrusive and demanding. Often children who have been abused are themselves aggressive, but this is not universal.97 Many abused children are socially immature and emotionally needy. The description of resistant/ambivalent and disorganized/disoriented attachment styles also fits many of these children.

Occupational therapy practitioners are mandated by federal law to report suspected cases of abuse and neglect to state child protective services agencies.36 Reports of suspected child abuse or neglect may be made by telephone and should be followed with a letter documenting the child’s demographic information, specific observations leading to the report, and the practitioner’s contact information. Referrals to child protective services are held in confidence, and persons who submit referrals in good faith are protected by law from prosecution. Statutes and information about reporting abuse or neglect for each state are available on the child welfare policy website (http://www.childwelfare.gov/systemwide/laws_policies/state/). Discovery of a practitioner’s failure to report suspected cases of abuse or neglect may result in prosecution and/or disciplinary action by the practitioner’s licensing board or in the civil courts.

Referrals to child protective services are reviewed and classified according to the situational risk. Families who are evaluated often receive a variety of intervention services, including respite care, parenting education, assistance with housing, day care, home visits, individual and family counseling, substance abuse treatment, and transportation. Fewer than 20% of the children whose families are investigated for abuse and neglect are taken into protective foster care.166

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS AND SOCIAL PARTICIPATION

Social participation can only be fully experienced when children and families live within supportive environments that provide opportunities for self-expression and connection with others. When these conditions are unmet, even for a limited time, occupational performance suffers. When conditions are less than adequate for prolonged periods, the child’s very course of development may be altered, with lifelong effects. Assessing the nature of a child’s environment is a critical stage of clinical reasoning when trying to determine the psychosocial contributors to occupational dysfunction.

Environmental factors that relate to psychosocial performance may be roughly divided into those that are relatively brief and those that are more long-term (Box 13-1). Time-limited events include personal and family stressors that are keenly experienced and then resolved over a period of weeks or months. Long-term events or situations are those in which the stressors are pervasive and continue for months or years. These categories are further described in the next sections. Although they are useful for general conceptual purposes, they should be applied with caution. Whether an event or circumstance falls into one category or another is partially dependent on the coping style and circumstances of the individual affected. For example, the death of a grandparent may be an event that a child feels acutely sad about for several weeks and then adjusts to, especially if the relationship was limited by distance or other factors. For a child who is very sensitive, or for whom the grandparent was a primary caregiver, such a loss could result in months of grief. If the child did not know the grandparent at all, the loss may be irrelevant.

Time-Limited Environmental Stress and Its Impact on Occupational Performance

Short-acting environmental conditions such as the death of an extended family member or friend, temporary marital crises, a change of school or day care, or a family relocation, can have significant effects on the child’s social participation. A survey of 56 school-based occupational therapists indicated that many of the students with whom they worked experienced such loss and grief in their lives and that their behavior reflected this.123 Children’s reactions to such events often include decreased performance in play or academic activities. The child may act preoccupied, fatigued, or uninterested in usual pastimes. Sometimes children temporarily “lose” their skills in self-care and revert to more dependent, infantile ways.182 They may become emotionally overreactive and engage in provocative behavior such as fighting or disobeying adults’ directives.125 Occupational therapists can help children and adolescents to cope with times of increased stress through establishing a therapeutic relationship, asking about how the child is feeling and the events that are occurring in their lives, providing opportunities for self-expression through activities, and communicating with the rest of the team to ensure the best possible communication and support throughout the child’s day. Educating the child, family, and others who are in contact with the child regarding typical grief reactions and ways to respond to these can also facilitate the child’s passage through difficult experiences (Case Study 13-2).

Chronic Environmental Stress and Its Impact on Occupational Performance

Long-term sources of social stress are circumstances and events that do not resolve over the course of weeks or months (see Box 13-1). Examples of these are poverty, social discrimination, and severe family dysfunction that may occur when one or both parents suffer from substance abuse or other mental disorders. These kinds of environmental conditions may have long-term effects on children’s development and social participation through the lifespan, especially if combined with other complications such as the child’s own neurodevelopmental problems.

More than 17% of children in the United States live in poverty. Of the children aged 18 and younger living in poverty, approximately 24% are black, 21% are Hispanic, 10% are white, and 10% are Asian.164 Long-term poverty has been associated with a number of serious problems for children and adolescents and for the adults who care for them.32,42 Having a low income and living in a crime-ridden environment have been shown to correlate with increased risk of having newborns born prematurely or with low birth weight, both of which increase the risk for subsequent developmental and health problems.120

The home environments of families with few resources may offer limited access to items that are considered to be “necessities” by a majority of members of the culture, such as books, toys, a telephone, television, or computer. The language opportunities in low-income homes are often different and reduced when compared with those found in middle-class homes (Case Study 13-3).108 Due to a combination of health and environmental factors, children who live in chronic economic deprivation are at increased risk for having lower cognitive abilities and more behavioral problems.18,42 Parents who experience the stress of chronically worrying about meeting basic needs for food, shelter, and safety are more prone to discipline their children harshly, have marital conflicts, experience depression, and have substance abuse problems.15,42,86,121 They may be too overwhelmed, discouraged, or disorganized to become involved in their children’s schooling. These conditions place many low-income students at a disadvantage and diminish their future opportunities. Some children who have experienced lifetimes of severe family and community dysfunction reach adolescence feeling hopeless about their futures. Their occupational performance is clearly affected by this as they struggle with society’s expectations to further their education in order to prepare for a productive adulthood, while from the discouraged adolescent’s perspective this is impossible to achieve.

Case Study 13-3 illustrates how poverty and other chronic stress factors can affect a child’s occupational performance, both in terms of the preparation for and availability of opportunities to achieve social participation. Although environmental factors are clearly influential in determining a child’s occupational performance, the PEO model reflects a balance of emphasis among its three components.106 Each individual has capacities and desires that strongly influence occupational expression. The following section provides information regarding the role that mental functioning plays in the enactment and development of children’s occupational performance.

MENTAL HEALTH FACTORS AFFECTING SOCIAL PARTICIPATION

Children’s developmental progress and occupational performance depend as much on how well their psychosocial needs are being met as they do on the adequacy of the nutrition and shelter they receive. In 1999, Dr. David Satcher, Surgeon General of the United States Public Health Service, supervised the publication of the results of a multiagency effort sharing the expertise of hundreds of service providers, researchers, and consumers. The Surgeon General’s Report on Mental Health states: “From early childhood until death, mental health is the springboard of thinking and communication skills, learning, emotional growth, resilience, and self-esteem. These are the ingredients of each individual’s successful contribution to community and society” (Chapter 1, Introduction & Themes).167

A fixed definition of mental health is difficult to formulate; behaviors and beliefs that are construed as “healthy” by one individual in a particular context may be considered to be inappropriate or unhealthy by someone else or in another context. The Surgeon General’s definition of mental health suggests cultural variables influence what behaviors are expected and, therefore, how mental health is defined: “Mental health is a state of successful performance of mental function, resulting in productive activities, fulfilling relationships with other people, and the ability to adapt to change and to cope with adversity. Mental health is indispensable to personal well-being, family and interpersonal relationships, and contribution to community or society.”167 For example, American parents of Northern European descent often value independence and achievement. Such parents might be concerned about the behavior of their five-year-old son, who wants his mother to help him with dressing and bathing, even though he can do these things for himself. This behavior might cause them to wonder if their child is immature or “spoiled.” Parents from a cultural background that promotes a climate of interdependence, such as that found in Japan, might expect such behavior and find it quite acceptable. It is clear that practitioners must be competent in assuming a multicultural approach in order to effectively evaluate social and emotional behavior.

Children and adolescents’ ability to participate socially and academically may be severely impaired by poor mental health. It is estimated that nearly 13% of children have mental or emotional problems, and 32.8% have mental and emotional problems along with other types of functional disorders.82 It is thought that increasing numbers of children are being diagnosed with mental disorders as a result of combination of increasingly sensitive diagnostics and contributing social pressures and problems.37,71,140,184 Effective interventions for these types of conditions typically require a combination of family education, special services at school, various therapies for the child and family, and, often, medication.

Occupational therapists approach their work with a client-centered, occupational performance—rather than a medical or pathology-focused—perspective.26,106 However, client-centered approaches do not preclude understanding the nature and course of a client’s illness or disability. To develop and implement client-centered, contextually appropriate intervention, the child’s symptoms, medication effects and side effects, and prognosis must be understood. Additionally, practitioners who recognize the diagnostic hallmarks of mental disorders that occur in childhood and adolescence can play an important role in referring children and adolescents in need of a diagnostic evaluation to specialists such as psychologists or psychiatrists. In many settings the occupational therapist may be the only team member who understands the symptoms and various interventions for mental disorders and their implications for occupational performance in school, child care, and at home. The following section presents an overview of selected mental disorders that can affect children and their implications for occupational performance. It is not unusual for individuals to experience multiple disorders simultaneously, such as depression and anxiety, Asperger’s syndrome and depression, or cognitive impairment and attention deficit disorder.6 A common criterion for all diagnoses of mental disorder is that the individual’s daily life and activities are significantly impaired by the symptoms.6

SELECTED MENTAL DISORDERS COMMONLY AFFECTING CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

Mood disorders involve long-term changes in the child’s prevailing emotions. The presence of symptoms may be cyclic, increasing and decreasing periodically, but they may last for months or years if untreated.6,99 The diagnostic criteria for major depression stipulates that symptoms must have reached a level of severity that results in changes in occupational performance or significant distress during daily activities.6 Depression manifests as persistent or repeated episodes of a combination of irritability, loss of interest in and enjoyment of usual activities, increased or decreased activity level, sadness, periods of crying, decreased energy, inability to concentrate and learn, agitation, sleep and/or appetite disturbance, anxiety, guilt, and/or thoughts of death or suicide. Depression is estimated to occur in 3% of children and 8% of teens.124 Children and adolescents who have experienced clinical depression are at increased risk to have repeated episodes into adulthood.6,69,100 The diagnostic evaluation of depression should be made by a psychologist or psychiatrist through structured interviews with the child and parents.124,146 Ascertaining a diagnosis in children may be complicated because the outward symptoms may appear inconsistently; the child may play and seem happy some of the time. Intervention often includes a combination of medications and psychotherapy or counseling parents.124,146 Brief hospitalization may be required if there is risk of suicide.

Occupational performance and satisfaction are adversely affected by the symptoms of depression. Difficulty with thinking and the loss of enjoyment and interest reduce the child’s motivation to play and decrease ability to attend and learn in school. Children with depression may sleep during the day, even in classes, and often experience aches and pains. They often complain of being tired or bored during previously preferred activities. Activity levels may be decreased or increased, so the child may be chastised for being “lazy” or “out of control,” depending on the situation. Unexpected tearfulness or displays of temper place the child in social jeopardy with adults and peers. Changes in appetite may affect social interactions during meals, as the child is scolded for eating too little or too much. There may be resistance to attending family, church, and other social activities. Among the most occupationally debilitating aspects of depression are the child’s feelings of incompetence, hopelessness, and helplessness. These emotions, however irrational, are symptoms of depression that can prevent children and adolescents from participating in activities that involve any risk of failure or humiliation: deciding which answer to choose on a test, raising one’s hand in class, inviting a peer to play, or joining in a game. Adolescents with depression must add the anxiety and self-doubt of depression to the feelings of self-consciousness typically experienced at this phase of life. Depression increases the risk of alcohol and drug use, as sufferers seek relief from emotions that are overwhelmingly painful.6,112

Bipolar disorder, or manic-depressive illness, is increasingly being recognized as a condition that often emerges during childhood or adolescence.25,72 Individuals with bipolar disorder experience “mania,” or periods of extreme overactivity, agitation, irritability, rapid (“pressured”) speech, and reduced periods of sleep.6 Less often, children and adolescents may display elation, giddiness, or grandiosity.19,88 Episodes of mania are juxtaposed by periods of typical or depressed mood. These mood states may fluctuate quite rapidly, sometimes even presenting as mixed states, or can alternate over a period of weeks or months.6,25 Sometimes a child’s changes in mood may be difficult to distinguish from voluntary behaviors aimed at provoking or controlling others.88 Mania in children may be misdiagnosed as attention deficit disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, or temporal lobe epilepsy.72 During manic phases some people have confused and bizarre thinking that may involve feelings of omnipotence, euphoria, and/or hallucinations. Children and adolescents with bipolar disorder are prone to episodes of aggression and despair and may pose a danger to themselves or others.72 Approximately 10% to 12% of adolescents with recurrent episodes of major depression will develop bipolar disorder.6 Individuals with bipolar disorder are at increased risk for suicide, especially during transitions from a manic to depressed mood state. A diagnostic evaluation should be completed by a psychologist or psychiatrist specializing in the care of children and adolescents, using structured interviews with the child and parents and direct behavioral observation. Intervention often includes medication, psychotherapy or counseling, and client/family education.72,88,146

Children and adolescents who have bipolar disorder may have periods of time when their behavior is noticeably “out of character” or socially inappropriate, or they may seem consistently irritable and active.19 Behaviors that are commonly experienced during low levels of mania include continuously talking, attention-seeking, disregard for others’ feelings or social norms, abruptly changing emotions, and impulsiveness. The child may resist adults’ attempts at guidance or correction or correct him and may act “bossy” toward adults. There may be aggressive outbursts toward property, other children, adults, or himself or herself. These behaviors are not compatible with performance as a student and may occur sometimes even if the child is taking medication. It is important that the adults who regularly interact with a child who has recurring symptoms of bipolar disorder know that these behaviors may not always be under the child’s control and have plans in place to respond effectively, avoiding behavioral outbursts that are disruptive or dangerous. Occupational therapy should include helping the child adopt regular sleeping habits, learn about the illness, engage in effective stress management strategies, and learn ways to communicate well with others. All team members should participate in monitoring the child’s behavior as it relates to medication effects. Some of the most effective medications used to treat bipolar disorder can cause life-threatening side effects if the child becomes dehydrated or the timing of dosage is incorrect.25

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders are characterized by pervasive and persistent (longer than 6 months) feelings of uneasiness, fearfulness, or dread that are not founded on realistic concerns.6 Estimated to occur in 4% to 13% of children, anxiety is a relatively common problem that is thought to result from a combination of inborn/genetic traits and environmental factors.25 The diagnosis of an anxiety disorder is made by a psychiatrist or psychologist through observation, interviews with the child and family, and self-report questionnaires.145 Symptoms of anxiety and depression often occur together, and medications and psychotherapy may be combined to address both kinds of problems.25,88 Subclinical levels of anxiety may also have a negative impact on children’s occupational performance and social participation and should receive attention by occupational therapists and others who work with children in schools and other settings.

Social anxiety disorder is estimated to affect up to 11% of all children and adolescents.38 Characteristic symptoms include excessive worrying about others’ evaluations of oneself or about one’s past and future behavior. Those affected exhibit considerable self-consciousness and a high need for reassurance by others.6,70,107 Children and adolescents who have social anxiety may be unable to participate in many of the activities in which they would like, or are expected, to engage.13,151 Any time the child feels he is at risk of criticism or embarrassment, he may become overwhelmed by automatic reactions such as a racing heart, blushing, feeling out of breath, and perspiring. Thinking is derailed by emotions of fear or even panic. The anxious child’s behavioral reactions to these overwhelming emotions (e.g., crying, resisting an activity, having a tantrum) may draw critical attention from others, further increasing social anxiety. Acute anxiety reactions can occur in an array of daily situations, such as being called on to perform in class, taking a piano lesson, walking into church, or learning to drive a car. Such experiences are subjectively unpleasant and may cause embarrassment due to others’ real or imagined reactions. Children and adolescents who have symptoms of social anxiety avoid and miss out on participating in many required and cherished activities.45

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), another subset of the anxiety disorders, is characterized by intrusive thoughts and repetitive behaviors that have little or no functional purpose beyond decreasing tension.6 OCD has been measured as affecting relatively few children and adolescents (fewer than 1%), but is thought by some experts to be underreported, as its expression is often confined to the home.63 Symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder may occur consistently or episodically, but they tend to be durable over many years, and are exacerbated by stress.160 OCD typically emerges between the ages of 6 to 15 years in males and 20 to 29 years in females.6

Children and adolescents with OCD may spend many hours per day engaging in behaviors such as hand washing, counting objects, arranging objects in a particular way, checking on the status of something (such as whether an appliance is unplugged), or cleaning. These behaviors may be visible to the casual observer or performed surreptitiously. In either case, if the repetitive activity is interrupted or prevented, the affected individual experiences anxiety. Intervention typically includes medication, client and family education, and cognitive behavioral therapy.25,63 Children and adolescents with neurologic impairments such as learning disabilities, Tourette’s syndrome, and autistic spectrum disorders are at increased risk of also having OCD.63,145

The daily balance of activity is negatively affected by the amount of time spent on obsessive-compulsive rituals in children and adolescents with this disorder. Tasks that would ordinarily take minutes may require hours as the child restarts the process again and again. Task interruption may occur as he or she stops to readjust unrelated objects or to wash hands repeatedly. Studying, packing a book bag, bathing, using the toilet, and getting dressed are just some examples of activities that could be severely affected by obsessive-compulsive symptoms. The child or adolescent with OCD also suffers socially, because even though he may know that his repetitive actions are irrational and, by others’ standards, “weird,” he feels compelled to continue doing them. It becomes easier to spend time alone and at home, rather than to cope with others’ reactions and misunderstanding. Occupational therapists can support team interventions by helping affected children and adolescents to understand the nature of this neurologically based disorder, teaching stress management skills, and helping them identify and reduce exposure to environmental triggers that stimulate obsessive thoughts.

Attention Deficit Disorder

Attention deficit disorder is characterized by significant difficulty with selective and/or sustained attention to tasks; this central problem may be accompanied by difficulties with overactivity and/or impulsivity. Attention deficit disorders are estimated to affect 8% of children and adolescents, with more boys than girls represented.6 A diagnosis is made through structured observations in a variety of settings and across time. Intervention often includes a combination of medication, behavior management, client education, support, and environmental adaptation.185

Children and adolescents with attention deficit disorder may have difficulty performing tasks in environments that are moderately or highly stimulating, such as the typical classroom or household. When trying to engage in activities, the child may have to work at continuously redirecting her attention from extraneous sounds and sights and back to the targeted task. Reading comprehension and listening skills are often affected. Impulsiveness may result in acting before thinking, leading to errors on schoolwork or inappropriate social behavior. Adolescents with attention deficit disorder may have difficulty following through on commitments due to disorganization and forgetfulness. They are less able to organize their time and materials than most of their peers. They may have difficulty sustaining effort on tasks, quickly become “bored” and leave tasks unfinished.

Occupational therapy for children with attention deficits should address the personal, environmental, and occupational factors. Children and teens can be taught to understand that they have a neurologically based problem. They can then learn ways to manage this through adherence to medication routines and attending and responding to their sensory and emotional states. Framing the child’s difficulty as a set of solvable problems, rather than as deliberate misbehavior, can help all parties feel better and behave more productively. Teachers, parents, and clients can learn ways to create and maintain physical environments that minimize auditory and visual distractions during tasks that require concentration and to modify tasks to allow well-timed breaks and opportunities for feedback. All involved parties can learn to structure and support a well-regulated routine of daily activities, with established and balanced patterns of sleeping, eating, work, and play.

Disruptive Behavior Disorders

Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) is characterized by a well-established pattern of disobedience and hostility toward authority figures that lasts for over 6 months. Children who fit this diagnosis often have excessive displays of temper, are irritable, deliberately refuse to comply with rules and directives, blame others for their actions, and act vindictively.6 They seek to provoke others by verbally threatening or insulting them. ODD is generally diagnosed by 8 years of age, and rarely after early adolescence; rates of its occurrence range from 2% to 16%.6 Conduct disorders are characterized by the many of the same behaviors as those seen in oppositional defiant disorder, but include more intrusive and severe forms of chronic misbehavior such as physical aggression toward property, animals, or people, theft, and/or lying. Environmental factors appear to play a large role in the development of disruptive behavior disorders; there is also evidence of genetic influence and a high rate of co-occurrence with neurologically based problems such as learning disabilities and attention deficit disorder.38 Many children with a conduct disorder are also diagnosed as having depression and/or attention deficit disorder and may receive medication for these problems.

Disruptive behavior disorders affect up to 10% of children and adolescents and seriously impede participation in family, school, and community activities.6,38 Conduct disorders place children at risk of harming others, breaking the law, and being placed in restrictive correctional or mental health facilities. Occupational therapists with clients who have disruptive behavior disorders are positioned to join a team effort to help children learn prosocial, adaptive ways to enjoy school, play, and rejuvenation. This begins with establishing a therapeutic alliance that includes well-understood and maintained expectations for positive behavior and reliable and fair consequences for behavioral infractions.38 Therapy that promotes achievement of recognition and feelings of competence through engaging in valued activities provides children with alternatives to antisocial behavior and motivation to behave in ways that allow participation in the larger community. Teaching the child how to use anger and stress management techniques, social interaction skills, and conflict resolution skills can be part of the occupational therapy plan. Consultation with other team members may include helping teachers and parents identify educational and functional tasks that are motivating, highly structured, and provide the “just right” level of challenge for that particular child or adolescent.

Autism Spectrum Disorders

Autism spectrum disorders, which manifest within the first 3 years of life, are characterized by (1) abnormal ways of relating to people, objects, and events; (2) delayed or missing speech, language, and/or nonverbal communication skills; and (3) restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and/or activities.6 Children with autism spectrum disorder exhibit a wide range of ability and variation in severity of symptoms. At one extreme, children have functional language and cognitive skills at levels that allow their participation in typical classrooms; children at the other end of the spectrum are functionally nonverbal and require continuous assistance and accommodation. Problems that may co-occur with autistic spectrum disorders include sensory processing dysfunction, cognitive impairment, anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, seizure disorder, fragile X syndrome, and tuberous sclerosis.127 The diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder has increased over the past 20 years, spurring debate as to whether this marks an actual increase in the incidence of the disorders or an increased sensitivity in diagnosing new cases.71 The number of special education students classified as having autism spectrum disorder increased by 189,000 between 1994 and 2006.81 Current estimates indicate that approximately 1 in 150 children have an autism spectrum disorder.31 This apparent increase has been attributed variously to a broadening of the diagnostic criteria, the advent of assessments that allow earlier diagnosis, and a possible increase in mistaking other language and cognitive disorders for autism.71,146 Children with autistic spectrum disorders may grow up to achieve full independence and community participation in adulthood or may require assistance throughout their lives. An individual’s long-term outcome is determined by a combination of factors, including the severity of the autistic disorder, cognitive ability, and social factors.39

Intervention for problems associated with autism spectrum disorders often includes behavioral methods, psychoeducational approaches, communication interventions, social skills training, and a variety of medications to address specific symptoms.6,127,136,146 (See Chapter 14 for additional information on this topic.) There is a growing body of evidence linking autistic disorders and sensory processing dysfunction.51,75 Occupational therapy may include sensory integration therapy, life skills training, and social skills training.10,74,114 Clinical trials have demonstrated positive effects for most of these interventions; however, the evidence is limited (see Case-Smith & Arbesman’s review of intervention applied by occupational therapists29). As with all interventions, families should be encouraged and supported in making a critical evaluation of the evidence to date before engaging in a particular intervention.146

The Occupational Therapist’s Role Relative to Psychotropic Medication

All of the mental disorders described above may be treated with medications as a central or adjunctive intervention. Research evidence to date indicates that, just as for adults, a combination of medication and therapy is more effective than either approach alone for anxiety and attention deficit disorders.64,92,98,136 The use of psychotropic medications among children and adolescents has increased significantly over the past 15 years.64,132 Approximately 17% to 22% of all students receiving special education services use psychotropic medications; this includes 42% to 52% of students classified as having emotional disturbance.130

Many children who receive occupational therapy services take psychotropic or seizure medications. The medical management of such drugs is made challenging by the children’s rapid growth and development, as well by as the lack of research to guide decision making.64,88 Although occupational therapists do not administer medications, they should stay apprised of their clients’ medications, and assume responsibility to be informed about the medications’ expected effects, possible side effects, and precautions. As a general guideline, therapists should consistently observe their clients for positive changes and possible unwanted drug effects and report these to the prescribing physician and in the client’s official record. Brown and colleagues have published a useful array of forms that can be used to systematically document behaviors and symptoms that reflect a child’s responses to medication.25 Any time a child displays an abrupt or marked change in his state of arousal (e.g., acts unusually drowsy or agitated), demonstrates signs of neurologic change (such as previously unobserved motor or cognitive difficulties), or complains of discomfort such as nausea or headaches, the possibility of medication side effects should be considered. If the observed symptoms are severe or of sudden onset, the situation should be treated as a medical emergency requiring the immediate notification of the child’s parents and evaluation by a qualified medical practitioner, such as a physician or registered nurse. All such observations and referrals should be documented by the occupational therapy practitioner in a timely manner.

Children and adolescents with psychological and behavioral problems live, work, and play in an array of environments. Their problems and needs may become apparent in a variety of ways, depending on the context. The following section explores the wide range of possible settings in which occupational therapists work with children whose occupational performance is affected by psychosocial dysfunction and how occupational therapy may be practiced in each.

PRACTICE ENVIRONMENTS

This section describes ways in which occupational therapists provide psychosocial intervention in a representative selection of settings and to illustrate how occupational therapists apply holistic, client-centered approaches. A variety of treatment settings are described, representing a continuum from less to more psychiatrically oriented and from less to more intensive and restrictive. The mission, clientele, services, frames of reference, and staffing patterns for each type of facility, as well as traditional or potential roles for occupational therapists in each setting, are outlined. Case studies synthesized from the author’s clinical experiences illustrate psychosocial intervention in a variety of traditional and nontraditional settings.

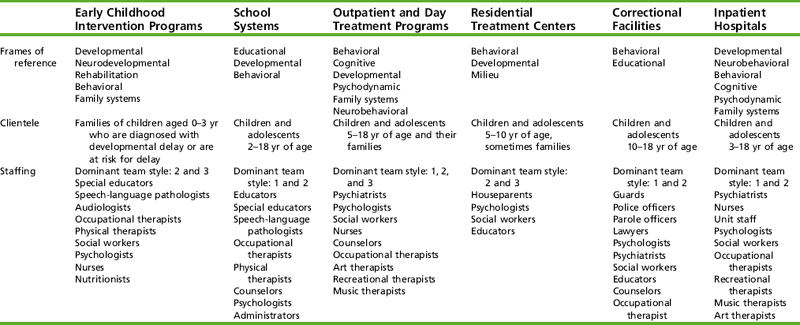

Therapeutic environments may include early childhood intervention programs, public schools, outpatient mental health services, day treatment programs, residential treatment centers, correctional facilities, and inpatient acute care hospitals. Some of these programs are designed specifically to assist children and adolescents who have identified mental health problems; other programs are oriented toward meeting more general developmental, educational, or social needs. Occupational therapists are established practitioners in some of these settings and are pioneers in other settings. In any case, pediatric occupational therapists have the knowledge base, the skills, and the opportunities to provide psychosocial intervention to children and adolescents with mental health and social problems in all service settings.

Early Childhood Intervention Programs

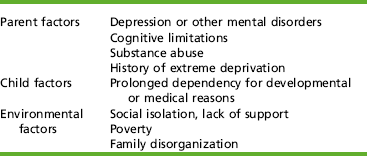

The primary mission of early childhood intervention (ECI) programs is the prevention and amelioration of developmental disabilities in children from birth to 3 years of age. According to the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA), clients include infants and toddlers who are diagnosed as having developmental delay, those who are considered to be at risk for developmental problems, and their families. Although infants and toddlers are referred primarily to early intervention for evaluation and treatment of neurologic and physical conditions, children may be referred when their development is at risk because of parental mental health problems, such as chemical dependency, domestic violence, parental depression, or other psychiatric disorders. Occasionally the identified infant may have a diagnosed mental disorder, such as failure to thrive or pervasive developmental disorder.6

Professionals working in ECI programs are likely to use developmental, neurodevelopmental, rehabilitative, behavioral, interactional, and familial systems as frames of reference (Table 13-3). Occupational therapists, educated to recognize and treat persons with mental illness, contribute significantly to the ECI team’s effectiveness with high-risk families. For example, mothers who are experiencing anxiety or depression are often unable to meet their infant’s needs for responsive interaction.41,80,137 Parents who are addicted to drugs are at increased risk of neglecting or abusing their children.149,184 Occupational therapists can observe clients for signs of problems such as depression and substance abuse and can facilitate clients’ access to evaluation and treatment by a qualified care provider. Environmental stressors such as poverty, social isolation, and community violence also need to be evaluated and addressed, since they play a part in a family’s ability to meet the needs of infants and children.44,64,79,174 If the parent of a child with medical complications reports that the family is having difficulty following through with the child’s care because of unemployment and marital stress, the ECI team is positioned to refer the parents for financial assistance, work placement, and counseling services. Once these concerns are resolved, parents have more energy available for child care. If there appears to be a danger of child abuse or neglect, the occupational therapist is mandated by law to report these concerns to the state child protection agency. Case Study 13-4 presents an example of family-centered early intervention.

Public School Systems

Students whose special needs are primarily psychosocial are classified by the school system as emotionally disturbed (ED). Federal regulations for IDEA define this special education classification as:

a condition exhibiting one or more of the following characteristics over a long period of time and to a marked degree, which adversely affects educational performance: (A) An inability to learn that cannot be explained by intellectual, sensory, or health factors; (B) An inability to build or maintain satisfactory interpersonal relationships with peers or teachers; (C) Inappropriate types of behavior or feelings under normal circumstances; (D) A general pervasive mood of unhappiness or depression; or (E) A tendency to develop physical symptoms or fears associated with personal or school problems. This category does not include children who demonstrate socially maladjusted behavior (e.g., delinquency, school truancy, conduct disorder) in the absence of the problems previously listed. Other categories in which psychosocial problems and behavioral disorders are often present include pervasive developmental disorders, mental retardation, and traumatic brain injuries [Code of Federal Regulations, Title 34, § 300.7(c)(4)(i)].

Emotional disturbance was the primary disability category for about 1 in 12 special education students in the year 2000 to 2001.82 The rate of educational diagnoses of emotional disturbance increases with age and grade level. Most children in need do not receive professional mental health care, so the public schools serve more children with behavioral and emotional disorders than any other agency.76 Students with mental health problems do not qualify for special education services unless their symptoms significantly disrupt their school performance, so their needs are often underserved at school, as well as in the community and health care systems.12 Occupational therapists working in the schools have an important responsibility to observe the students with whom they work for signs of emotional distress, as many children with mental health problems also have the learning and attentional disorders that are typically referred for services at school.

The primary mission of public education is academic and social preparation for future education and work roles. Research shows that this goal has been largely unreached for students who have emotional and behavioral problems.20,27,110,177 Students with moderate to severe behavioral problems are unable to take full advantage of education and experience repeated academic and social failure. More than 50% of students with emotional or behavioral disorders drop out of high school.165 These students have a significantly increased risk for economic dependency and crime.20,175 The public schools represent an arena in which occupational therapists have an unrealized opportunity to have a tremendous effect on the lives of children with psychosocial problems.12,123 See Chapter 24 for further description of school mental health programs.

A variety of school settings serve special education students with ED. Self-contained classroom arrangements allow students whose behavior is frequently disruptive or otherwise inappropriate to receive intensive behavioral intervention while being educated in a small group setting. However, students in such classrooms are segregated from peers and role models and suffer the stigma of being identified as “different.” This segregation contradicts the goal of full inclusion of special education students in regular education settings.172 In a full inclusion model, students attend regular education classrooms with support services that may include a resource room for specific subjects, classroom aides, crisis intervention, and counseling services. Benefits of this approach include regular exposure to a typical school environment, opportunities to interact with typically developing peers, and positive experiences that reinforce learning of social skills. Problems can arise with this approach when the teachers have large numbers of students and little training in preventing or managing disruptive behaviors. Teachers and students then feel inadequate and frustrated.

Many classroom teachers incorporate social skills training programs into their regular curricula. These programs are suitable for all children, and they address areas such as communication and social skills,66 violence prevention,23 and drug abuse prevention.67 Such educational programs can provide an excellent means of developing prosocial thinking and behavior in typically developing children. However, these programs do not provide the intensive guidance required by many children and adolescents who have psychosocial dysfunction affecting performance in these areas.143

School-based therapeutic intervention is directed toward enhancing students’ academic and future vocational performance with an emphasis on both scholastic and social development. Traditionally the school psychologist, counselor, or social worker assumes responsibility for evaluating psychosocial needs and may work with students in individual or small group sessions. These professionals serve the needs of all students, not just those in special education, and may not have an extensive clinical background in psychopathology.110 They apply behavioral, cognitive, and developmental approaches (see Table 13-3).

Many leaders in education and occupational therapy believe that the services provided to students with behavioral disorders are inadequate in quantity and quality.* Teachers express despair as they sacrifice creative educational methods to address behavioral crises. Parents of students with behavioral disorders are frustrated by the paucity of services to address their children’s particular needs. All parents are concerned about their children’s safety and education while they are at school.

Occupational therapy activity groups have been described as effective for elementary students who have social and behavioral difficulties.50,147,148 Motivating activities such as planning and preparing meals, creating craft projects, producing a newspaper, performing skits and plays, and refinishing furniture help students develop competencies in daily living skills while practicing adaptive responses to interpersonal challenges and developing self-confidence. The goal of this type of approach is to support improved occupational functioning in the classroom and other school settings. Students’ behavioral improvements in occupational therapy task groups have been shown to generalize to the classroom and other contexts, thus winning the support of educators and administrators in the school.1,148 Agrin speculated that the students’ future success in less restrictive settings could be predicted by the development of their social skills in the activity groups.1

Students who are referred for occupational therapy services to address fine motor, perceptual, or orthopedic problems may also have social and emotional needs that impair academic performance. Case Study 13-5 exemplifies how one student’s multiple needs were addressed. General education teachers are working with increasing numbers of special needs children, including those who have educational diagnoses of emotional disturbance. Additionally, their classrooms include children who are not enrolled in special education, but who are troubled and preoccupied with acute and/or chronic life stresses such as poverty, community violence, and family turmoil. In some schools the majority of students are trying to learn despite a climate of constant crises in their homes and neighborhoods. Behavioral disruptions are frequent and educators feel endangered and unsupported. Occupational therapists are positioned to provide consultation to teachers who need ideas regarding environmental adaptation and group management and to help determine which students should be referred for occupational therapy or other related services evaluations. By educating and supporting teachers, therapists can have a positive influence on the school experiences of hundreds of children.

The School to Work Opportunities Act (1994) and IDEA (2004) both reflect the high priority placed on preparing students for gainful employment. Middle and high school students who have emotional and behavioral problems are considered by many to be among the most challenging to transition successfully into independent living and satisfying, economically sustaining work.27,111,175 Although no universally successful means have been identified, research to date indicates that the most promising interventions include individualized planning that involves the student and parents. The intervention should also include social skills training and support, classroom education regarding work values and life skills, and actual work experience in positions where the fit between students and jobs is optimal.110 Age- and situation-appropriate occupations should be emphasized over performance components training, and environments should be structured to facilitate students’ success.24,134 Occupational therapists are able to provide any and all of these interventions, and they can serve educational teams, as well as transitional planning specialists.

School-based occupational therapists do not consistently emphasize psychosocially oriented intervention.12,30,123 On the basis of a review of the special education literature, Schultz concluded that teachers would welcome the kind of assistance that occupational therapists can provide in improving students’ social skills.147 School administrators who are concerned about occupational therapists meeting the needs of the traditional referrals may initially be less encouraging. School-based therapists who are committed to providing holistic services need to educate and persuade colleagues regarding the potential effectiveness of occupational therapy approaches to help students meet central academic goals by developing essential skills needed for social participation. This may be approached directly through discussions with key administrators, in-services for teachers and related services professionals, program development, and case-by-case demonstration. Occupational therapists should advocate including psychosocial goals in students’ individual education programs. Trends in inclusionary and transitional education have created an atmosphere in which occupational therapy leadership in comprehensive holistic intervention approaches are needed and often welcomed. Examples of evidence-supported, activity-based interventions used by school-based occupational therapists in their work with students with emotional disturbances are listed in Box 13-2.

Mental Health Services

In the United States, mental health services for children and adolescents have been chronically underfunded, with the result that most young people who have mental disorders do not gain access to expert professional services.109,163,167,183 In 1992, Congress responded to this problem by authorizing the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children and their Families Program.165 This program provides federal funding through demonstration grants to states and communities and is designed to develop and promote effective ways to organize, coordinate, and deliver mental health services and supports for children and adolescents and their families. Private foundations have joined in the effort, resulting in the coordination of multiple agencies within communities working together to provide innovative, client-centered, culturally appropriate services. A universal goal of contemporary community-based mental health services for children is to facilitate successful participation within the family, community, and school. Best-practice standards for children with severe and complex needs involve a “wraparound” planning and management process, in which the family and all involved care providers work closely together to ensure well-coordinated, comprehensive intervention.183 Although few occupational therapists identify mental health settings as their primary site of practice, many practice in settings that participate in the coordinated care of young people with mental health problems.126 These settings include early intervention services, day care programs, preschools, schools, and hospital-based outpatient clinics. Although most mental health centers and private practices do not include occupational therapists as part of their core team, occupational therapists can participate as valuable ad hoc members of the extended, community-based mental health team and as consultants. Understanding the forms and functions of contemporary mental health systems allows occupational therapists to engage effectively with the professionals working within the system and to join in providing coordinated care from a unique perspective.

Outpatient treatment is the mental health intervention most commonly accessed by children and adolescents.167 Outpatient mental health services may be provided through freestanding clinics, hospital-based programs, publicly funded community mental health centers, health maintenance organizations, and private practices. Funding sources may include the clients’ families, private insurance, Medicaid, federal grants, and state monies.102,118 An agency’s sources of funding influence the types of clientele served and the types of services provided.

Children and adolescents who seek outpatient mental health services often have significant behavioral disturbances that have caused moderate to severe levels of disturbance for family, school, or community members.102 The primary goals of outpatient mental health services are the diagnosis and management of mental health problems to improve functioning within the community and prevent crises necessitating hospitalization.

The child’s initial contact with an outpatient mental health practitioner—typically a social worker, psychologist, psychiatrist, or licensed counselor—consists of an intake interview exploring the nature and severity of the child’s and the family’s problems. Responses to the interview form the basis for decisions regarding appropriate evaluation and intervention. Possible dispositions include outpatient evaluation at a later date or crisis evaluation with immediate short-term intervention.

Frames of reference used in outpatient programs and practices vary, but they commonly draw from cognitive behavioral, behavioral, family systems, neurobiologic, and psychodynamic theories (see Table 13-3). Treatment approaches are most commonly goal-focused and time-limited and involve the family and school. Clients generally attend one or two 1-hour sessions per week for a specified period. In publicly funded mental health centers, payment for services is based on the individual’s income. Third-party payers have varied levels of coverage for mental health care. Therapeutic modalities commonly include play therapy (for young children), talking therapy, expressive art, therapeutic board games, group discussions, family discussions, and parenting education sessions. These programs can be staffed by a combination of psychologists, social workers, psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, and licensed counselors.118

Day treatment programs and therapeutic schools are offered in a variety of settings, including psychiatric hospitals, community mental health facilities, and schools for students with special needs.141 Such programs provide a therapeutic level of intensity between outpatient intervention and hospitalization and are popular for clinical and economic reasons.54 Clients typically attend programming from 4 to 6 hours per day, 5 days per week, and are at home during evenings and weekends.21 Interventions often include a variety of therapies, including occupational therapy and specialized academic classes.

Day treatment programs or schools can facilitate a child’s transition from the hospital back to the home and community, provide crisis stabilization, allow comprehensive evaluation, or serve as an intensive therapeutic alternative to outpatient or inpatient treatment.141 Programming often follows a psychoeducational model and may include vocational evaluation and training for adolescents.128 A psychiatrist or psychologist who specializes in child and adolescent mental health or a special educator typically leads intervention teams. Other team members are listed in Table 13-3 and can include occupational therapists.

Occupational therapy activities in day programs can address academic, sensorimotor, daily living, and psychosocial goals. Crafts, role-playing exercises, cooperative action games, board games, cooking, sensorimotor interventions, and field trips are popular modalities in such occupational therapy programs. Hygiene and grooming, telephone and e-mail etiquette, how to order food in a restaurant, and other such daily living needs can be addressed. Working with the client’s parents, child care providers, teachers, job coach, or school-based occupational therapist can facilitate the transition from intensive day treatment programs to the community and public school and enhance the carryover of interventions and goals. The family may also benefit from assistance with locating and securing social and leisure resources. Case Study 13-6 describes how a consultative model of intervention can be used to assist with the transition of a client from day treatment back to full community involvement. The focus in this example is on educating and problem solving with personnel from another agency.

Residential Treatment Centers