Violence Against Women

• Describe the beliefs and practices that historically have perpetuated violence against women.

• Examine the prevalence and effects of intimate partner violence.

• Contrast the theoretic premises underlying the victimization of women.

• Discuss theories of violence and how they can be used in assessment and intervention for women who are abused.

• Develop a plan of care for a woman who is experiencing intimate partner violence.

• Review the dynamics of sexual assault.

• Describe the rape-trauma syndrome.

• Develop a nursing plan of care for a woman in the acute phase of rape-trauma syndrome.

Violence against women (VAW) is a worldwide public health problem. The United Nations defines it as “any act of gender-based violence that results in or is likely to result in physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women including threats of such acts, coercion, or arbitrary deprivation of liberty whether occurring in public or private” (Blanchfield, 2008; United Nations, 1993). Around the globe VAW takes many different forms including but not limited to intimate partner violence, sexual assault, marital-rape, dowry-related violence, sexual trafficking and exploitation, and female genital mutilation. This chapter focuses on intimate partner violence and sexual assault.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is the most common form of VAW, with a reported lifetime incidence of one out of every six women (World Health Organization [WHO], 2010). The National Violence Against Women Survey (NVAWS) defines IPV as “the actual or threatened physical, sexual, psychologic, or emotional abuse by a spouse, ex-spouse, boyfriend, girlfriend, ex-boyfriend, ex-girlfriend, date, or cohabiting partner” (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2006). The term generally implies female victims and male perpetrators, but an estimated 7.4% of IPV is committed against men (Tjaden & Thoennes). IPV can be thought of as “a continuum ranging from one hit that may or may not impact the victim to chronic, severe battering” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2008). Other terms such as partner abuse and domestic or family violence are common. Older terms such as wife battering or spouse battering are generally not used. Battery has been used in the past to refer to physical contact with another with the intent of harm. IPV is the preferred term in that it encompasses not only physical contact but also emotional and other forms of violence previously ignored (Saltzman, Fanslow, McMahon, & Shelley, 2002).

IPV is a complex, stigmatized problem involving issues of emotional distress, personal safety, and social isolation. In many places in the United States and abroad IPV has been socially tolerated or ignored. Lack of reporting and inconsistent definitions have made it difficult to get an accurate count of the number of victims with wide ranges of estimates. Existing data tell us that IPV is pervasive.

The World Health Organization (WHO) found that the incidence of IPV ranged from 15% to 71% in a sample of 24,097 women from 10 countries not including the United States (Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2006). In an IPV study of 3568 female members of a nonprofit health maintenance organization (HMO), 44% of the predominantly Caucasian college-educated women reported abuse of any kind, 34% reported physical forced sex and/or sexual contact; 35% reported nonphysical abuse (threats and anger, controlling behavior) at some time in their adult lives, and 14% experienced abuse within the last 5 years and 8% in the last year (Thompson, Bonomi, Anderson, Reid, Dimer, Carrell, et al., 2006). In a prospective survey of 2737 urban public hospital emergency department (ED) clients, 548 (20%) identified themselves as victims of IPV. Greater victim-perceived danger was associated with lower physical and mental health functioning in the 216 of those who returned for follow-up (Straus, Cerulli, McNutt, Rhodes, Conner, Kemball, et al., 2009). The National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) indicates that 1 in 5 murders in 2005 were IPV related. IPV was involved in 8 out of every 10 homicides, and 90% of the persons who did the killing were men (CDC, 2008). Although overall U.S. violence rates, including IPV rates, declined between 1998 and 2008 the percentage of women killed by an intimate partner rose from 40% to 45% (Catalano, Smith, Snyder, & Rand, 2009).

Abusive relationships happen to couples who are dating, living together, or married. They can continue after the relationship ends. The abuse may be physical, sexual, psychologic, or financial. One partner behaves in a way that injures, intimidates, humiliates, frightens, or terrorizes the other partner. These behaviors can be insidious, slowly happening over time. Emotional abuse may include name calling, acting in a jealous or possessive manner, trying to isolate the woman from her family or friends, putting her down in front of others, threatening her children or alienating her children from her, not wanting her to go out or go to work, or insisting that she account for every minute she is away from home. Physical violence may never be used, or used rarely, but threats can be as effective as actual violence. Once physical violence happens, the threat of recurrence always exists.

IPV may begin in pregnancy. If it already exists, IPV may increase, decrease, or stay the same during the pregnancy (Macy, Martin, Kupper, Casanueva, & Guo, 2007; Taylor & Nabors, 2009). (See later discussion on p. 103.)

The consequences of IPV are profound. In a study comparing abused women with never abused women, abused women had a higher incidence of social and family problems, substance abuse, menstrual and other reproductive disorders, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), musculoskeletal and gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, chest pain, abdominal pain, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and headaches (Bonomi, Anderson, Reid, Rivara, Carrell, & Thompson, 2009). In another study, women who had experienced abuse had a 50% to 70% increase in central nervous system (CNS), gynecologic, and anxiety-related problems (Campbell, J., Jones, Dienemann, Kub, Schollenberger, O’Campo, et al., 2002). In a study of 82 women diagnosed with depression, the researchers found that 61% of them had experienced IPV in their lifetimes and that the severity of violence was significantly correlated with the severity of depression (Dienemann, Boyle, Baker, Resnick, Wiederhorn, & Campbell, 2000).

Medical costs alone for interpersonal violence are estimated to be $2.7 to $7 billion for the first 12 months after victimization, and annual medical costs for any past intimate partner victimization, not just the last year range from $25 to $59 billion (Brown, Finkelstein, & Mercy, 2008). These figures do

not include the cost of police and court costs, shelters, foster care, sick leave, and nonproductivity. Reducing the rate of intimate partner violence was a Healthy People 2010 objective and a modified version is included in Healthy People 2020 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2009).

Historical Perspective

Women have been treated inhumanely throughout history. In ancient Rome, wives were divorced or killed by husbands for adultery, public drunkenness, or attending public games, whereas men could engage in these activities daily. In the 1700s, under English common law, the “rule of thumb” gave men permission to chastise their wives physically as long as the implement they used was no wider than their thumbs. In the late 1600s, Pilgrims and Puritans directed male heads of the family to use force when needed to maintain conduct of their wives. Although American law prohibited beating wives, the Puritans supported physical force by husbands as legitimate. In the 1800s men gradually lost the right to beat their wives. Slow progress was made in the early 20th century. There was little awareness from both health care professionals and the legal and justice systems to the plight of women in intimate relationships. As late as the 1960s, it was believed that violence in the family was rare and committed only by the mentally ill.

The first shelter for women opened in London in 1971, and books and articles on domestic violence began to appear in the 1970s. Battered woman syndrome was described by Lenore Walker in 1979 and battered women programs begin to emerge in the 1980s. In the 1990s the American Nurses Association issued a position statement against VAW, the American Medical Association declared that physicians were liable if they did not recognize IPV, and The Joint Commission issued standards to identify and manage IPV patients. The National Domestic Violence Hotline was established in 1996. The CDC issued guidelines promoting the phrase intimate partner violence over domestic violence (Mitchell & Anglin, 2009). Health care providers, law enforcement, the legal system, and the general public are slowly acknowledging IPV, but power imbalances, persistent beliefs that family problems are private matters, and fear continue to keep women from disclosing abuse.

Conceptual and Theoretic Perspectives

In the late 1970s little was known about IPV. Lenore Walker, a pioneer in the field, interviewed 120 victims. From those interviews with a select group she described the “battered woman syndrome,” which identified victim characteristics such as learned helplessness and abuser characteristics such as mental health problems. At the time Walker proposed a model of how IPV might appear in some families. The model, referred to as the cycle of violence described three phases in an IPV relationship: tension building, acute battering, and the honeymoon phase. In her proposed model, violence was neither random nor constant but occurred in repeated cycles. Her continued research led to modifications in her early interpretations. Ongoing research from different disciplines has expanded today’s understanding of IPV. Current thought does not support the general applicability of the cycle of violence.

IPV is heterogeneous. Not all batterers are alike, not all victims are alike, and not all relationships and patterns of abuse are alike. In some relationships physical and psychologic abuse happen on a regular basis. In other relationships, physical abuse or the threat of abuse may happen rarely, but emotional abuse is more persistent. In some relationships abuse happens after stressful events or pregnancy. Walker’s work was an important first step and helped raise awareness and interest. Because the cycle of violence was the only available explanation for IPV, the model became a core part of IPV training for health professionals, social workers, law enforcement officers, and judges. Despite limited evidence of its usefulness many professionals still believe that the cycle of violence explains IPV (Dutton, 2009).

The past 30 to 40 years have seen a growing body of literature about the characteristics and dynamics of IPV. Along with feminist ideologies that play a critical role in gender-based violence, theories from biology, psychology, and sociology all help to partially explain various aspects of violence against women. No single theory can completely explain this complex problem. Following is a brief discussion of some of these theoretic perspectives.

Biologic Factors

A complete explanation of the biologic perspective is beyond the scope of this chapter, but evidence indicates that neurobiologic and hormonal factors influence aggression in men. Areas in the brain believed to play a role in aggressive behavior are the limbic system, the frontal lobes, and the hypothalamus. Changes in structural functioning of the limbic system, such as occur with brain lesions, substance use, epilepsy, and head injuries, affect the emotional experience and behavior of the individual and thus can increase or decrease the potential for aggressive behavior (Stuart & Hamolia, 2009).

Neurochemical factors also can play a role in aggressive behavior so that dysfunction or disregulation of certain neurotransmitters can result in aggression. Increased levels of norepinephrine and L-dopa foster aggressive behavior. Reducing the levels of serotonin in animals causes aggressive behavior. The amino acid gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) inhibits aggressive behavior. The occurrence of violence in neurologic disorders also is reported, especially when violent reactions are out of proportion to the provoking events (Stuart & Hamolia, 2009).

In studies of animals, aggression is associated with abnormally high levels of testosterone. Soler, Vinayak, and Quadagno (2000) reported higher testosterone levels in abusive male subjects and suggested that heritability is an issue that warrants the inclusion of this variable in future studies of violent behavior. There is no conclusive evidence in biologic theory, except perhaps in instances of neurologic damage, that it is impossible to control aggressive behavior.

Psychologic Perspective

Psychology, the study of emotion and behavior, places responsibility for behaviors such as aggression on the individual. Early psychoanalytic theory suggested that aggression is a basic instinctual drive leading to mastery and accomplishment. In men aggression was seen as a positive force that connoted boldness, forcefulness, energy, and enterprise. Thus early psychologic theory saw aggression in men as normal. Early psychoanalytic theory promoted gender-stereotypic expectations for women to be caring and nurturing; aggression in women was and still is viewed negatively and aggressive women are often labeled as hostile and belligerent.

The myth that abuse is committed by people who have some type of mental illness perpetuates the notion that violence occurs among people who are not “normal.” Mental illness accounts for a very small percentage of IPV. Men who batter range from having modest personality dysfunction to significant personality pathology such as borderline and antisocial personality disorders (Capaldi & Kim, 2007). Although a mental health diagnosis of alcohol abuse is frequently found in abusers, it should not be misconstrued as the cause of violence. There is some evidence that alcohol may increase the risk of violent behavior because survivors of violence often report abuser substance abuse (Torres & Han, 2003). There is no diagnostic profile of an abuser, but Box 5-1 provides some characteristics of men who batter that nurses may consider when assessing clients’ relationships.

Women with severe and persistent mental illness are likely to be more vulnerable to being involved in controlling and violent relationships. However, numerous mental health problems (such as depression, psychophysiologic illnesses, substance abuse, eating disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], and anxiety reactions) experienced by women with abusive partners are more likely to be consequences of long-term abuse rather than causes (Moracco, Brown, Martin, Chang, Dulli, Loucks-Sorrell, et al., 2004). Relationship violence differs by the severity and frequency of violence, if the violence is confined to the family or occurs outside the family and by the individual’s characteristics. Not all victims see their violence experiences in the same way; different women experience violence differently. Women with dependent personality traits as well as independent women have been victims of IPV. Although there may be shared characteristics, each person’s experience and response is individual (Nurius & Macy, 2008).

Newer studies in psychology are exploring the unique differences among individuals who are in violent relationships. We know that men who are involved in relationship violence are not all alike. Heterogeneity is seen in the characteristics of the men, in their partners, and in the relationship dynamics. When trying to understand some types of violence, there is growing interest in considering both members of a relationship. In one conceptual model Capaldi and Kim (2007) explore the typologies of couples experiencing violence. They offer a dynamic systems model that considers what each person brings to a relationship. For example, personal characteristics such as depression or antisocial behavior might be combined with a person’s emotional development to create a unique individual. Individuals come together to create a pattern of interactions and these interactions occur in the context of various social stresses such as substance use, financial stress, or separation. The dynamics can lead to some type of incident. Viewed this way, this dynamic model provides many potential areas for intervention. Research is needed to further explore the possibilities of this approach.

Sociologic Perspective

The social structure and conditions in Western society provide the basis for many of the prevailing attitudes toward violent behavior. U.S. history is filled with examples of violence, such as war as a means of social control. Social acceptance and promotion of violence in men are double standards because women are expected to be nonviolent. Thus psychologic theories of gender-based behaviors can influence social beliefs and responses to particular behaviors. Because men are socially expected to be aggressive, their violence is sometimes treated with more leniency and less stigma than women who are violent, particularly in the justice system. The more a culture uses physical force for socially approved ends, the more the violence becomes generalized to other areas of social life (Fishwick, Parker, & Campbell, 2005).

The structure and dynamics of the family—ascribed roles of family members, the amount of time spent together, the private nature of the family, the intensity of emotional involvement, and stress and conflict inherent in families—often set the stage for violent behaviors (Fishwick et al., 2005). Power and violence, or even the threat of physical force, serve to maintain the patriarchal view of woman’s place in the home and in the rest of society. Gender inequality, in both economic opportunities and physical strength, serves to perpetuate the power imbalance in relationships.

Another family issue is the multigenerational transmission of violence; some perpetrators of violence and some victims learn about violence in families of origin by either witnessing or experiencing violence while growing up (Cannon, Bonomi, Anderson, & Rivara, 2009; Fishwick et al., 2005). In families in which violence occurs, both the lack of emotional support experienced by children and the awareness that people who love each other can be violent are important factors. Children in these environments do not have role models to help them develop mental models of healthy family dynamics. Abuse as a child does not consistently determine later violent behavior because many children who were abused grow up to avoid violent behavior.

Feminist Perspective

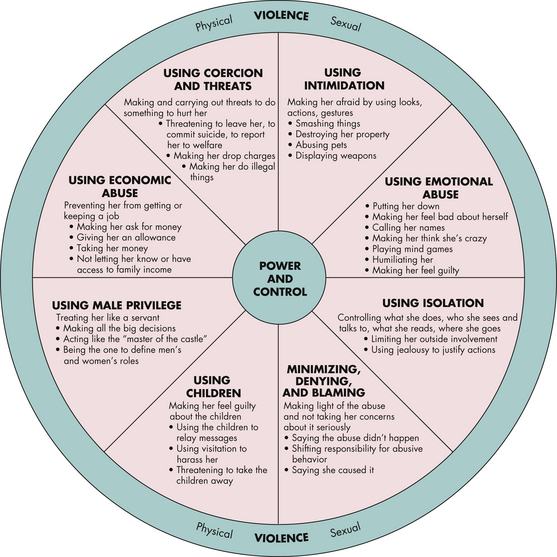

One contemporary view of violence is derived from feminist theory. This view, with the primary theme of male dominance and coercive control, enhances our understanding of all forms of violence against women, including IPV, stranger and acquaintance rape, incest, and sexual harassment in the workplace. This gender and power perspective evolved from women’s descriptions of their abusive experiences and from activists attempting to understand the victimization that occurred. In numerous cases, power and control tactics were central events leading to the violence (Renzetti, Edleson, & Bergen, 2001). The power and control wheel developed by the Duluth, Minnesota, Domestic Abuse Intervention Project identified ways that men may exercise the power and control that underlie many types of IPV and has been used to help women, men, and care providers understand violence (Fig. 5-1).

FIG. 5-1 Model of how power and control issues perpetuate battering. (Developed by the Duluth Domestic Abuse Intervention Project, Duluth, MN.)

As our understanding of the complexity of violence against women has evolved over time so has the need for an evolving feminist viewpoint. Using frontline workers’ perspectives of current feminist thought, one study proposes an integrative feminist model. Keeping gender and other forms of oppression as the roots of IPV, an integrative model offers flexibility in exploring multiple other models emerging in violence research (McPhail, Busch, Kulkarni, & Rice, 2007).

Ecological Model

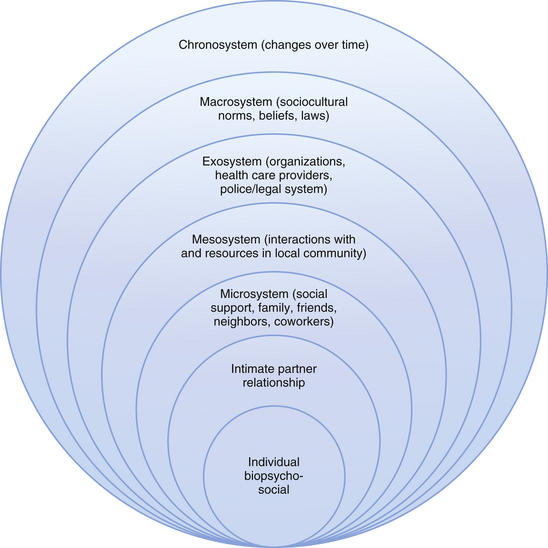

An ecological model is a useful tool when trying to understand a complex social issue like IPV. Ecological models help to make apparent the dynamic relationship between the individual and the environment. Bronfenbrenner (1979, 2005) explained how an ecological model might explain child development. An ecological model is sometimes drawn as nested circles that represent characteristics of the individual and the things in that person’s immediate and larger environment that influence the phenomenon of concern. The model has been adapted and used to understand a variety of health behaviors and social issues. The WHO uses an ecological model to look at communities. Heise (1998) adapted one for IPV and Campbell and colleagues (2009) developed a similar model for sexual assault.

Figure 5-2 is an ecological model of IPV. The individual woman is at the center of the model. Her unique characteristics, such as age, life experience, race/ethnicity, social class, education, personality, emotional well-being, finances, and so on influence who she is and how she is in the world. In her immediate environment is her intimate partner, his characteristics, and the characteristics of their relationship. At the next level (microsystem) are her children, family, friends, and the people and activities in her daily life that are important such as her neighbors, employer, or coworkers. Surrounding the social network are community resources such as women’s groups, violence prevention programs, and local resources (mesosystem). The exosystem refers to organizations and formal agencies, health care systems, and providers such as nurses, the police, and the legal system. All of these are influenced by the larger sociocultural beliefs, myths, and media (macrosystem). Finally, the chronosystem represents the influence of events over time.

FIG. 5-2 Ecological framework for intimate partner violence. (Adapted from Bronfenbrenner, U. [1979]. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; Bronfenbrenner, U. [2005]. Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Heise, L. [1998]. Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women, 4[3], 262-290; Campbell, R., Dworkin, E., & Cabral, G. [2009]. An ecological model of the impact of sexual assault on women’s mental health. Trauma Violence and Abuse, 10[3], 225-246.)

For example, a woman (individual) experiencing IPV over time may develop chronic depression and hopelessness, finding it more difficult to mount the energy needed to change or leave the relationship. Her partner interactions may have pushed away her friends, and her emotional state makes it difficult to rebuild relationships. Perhaps her family or friends are influenced by social or cultural expectations not to interfere in someone else’s marriage. The woman is socially isolated. She may hear about IPV issues from a local women’s group, helping to destigmatize her perception of the issue. If she risks disclosing her experience to a nurse and receives validation and support, she may be more likely to seek help again in the future, perhaps with the health care system, or with another social agency. The nurse who interacted with the woman is also influenced by that experience in providing support to a victim of IPV. All parts of the model are influenced by other parts, and those influences change over time.

Women Experiencing Intimate Partner Violence

Characteristics of Women in Abusive Relationships

Every segment of society is represented among people experiencing abuse. Race, religion, social background, age, and educational level do not differentiate women at risk. Poor and uneducated women tend to be disproportionately represented because they are seen in EDs, they are financially more dependent, they have fewer resources and support systems, and they may have fewer problem-solving skills. Women with educational or financial resources have been hidden from public awareness but can just as easily be victims (Thompson et al., 2006). They may be disadvantaged in other ways in that they do not fit the stereotype of an abused woman and find it difficult to come to terms with the idea that they are in an abusive relationship (Steiner, 2009).

The value women place on their social roles may have some influence in intimate partner violence. Traditional feminine characteristics such as compassion, sympathy, and yielding often result in greater tolerance of male dominance and more acceptance of partner violence. In contrast the traits of assertiveness, independence, and willingness to take a stand have been viewed as more characteristic in women who are in nonviolent relationships (Faramarzi, Esmailzadeh, & Mosavi, 2005.) There is little research that tells us how these characteristics might change if independent, assertive women found themselves in abusive relationships. Although women who are in abusive relationships may appear passive or even helpless to an outside observer, their behaviors may be active efforts to reduce the risk of violence as they survive day to day (Dutton, 2009).

Survivors of IPV may believe they are to blame for their situations because they are “not good enough, not efficient enough, not pretty enough.” The woman may blame herself for bringing on the violent behavior in her relationship because she believes she must try harder to please the abuser. In many cases, a traumatic bonding with the man hinges on loyalty, fear, and terror. Some women have low self-esteem. Some may have histories of domestic violence in their families of origin. Often abused women are socially isolated. This may be the result of stigma, fear, restrictions placed on them by their partners or partner behaviors that discourage others from being involved.

Based on the self-appraisal of 448 victims who filed a police report, Nurius and Macy (2008) identified five subgroups of victims. Each group varied in their feelings of vulnerability, sense of power, symptoms of depression, social relationships with others, type and duration of exposure to violence, and physical health. The largest group was composed of women who felt vulnerable to continued abuse and had high depression scores. The second group included women struggling with depression but with a low sense of vulnerability. A third group felt vulnerable to violence or abuse but were otherwise healthy with low rates of depression and strong social relationships. One group included women with multiple resources including good health, low depression scores, lower sense of being vulnerable, and high social support. The last group included women with high rates of vulnerability, physical injury, depression, and negative social relationships.

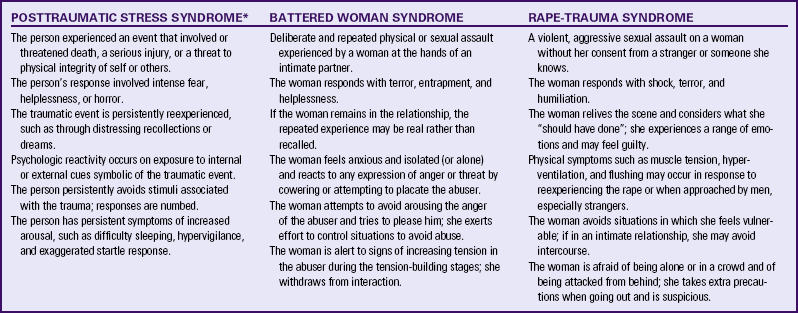

Some survivors of IPV may be formally diagnosed as having PTSD, provided that the symptoms meet the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). Table 5-1 compares the characteristics of PTSD sufferers with characteristics of women survivors of violence and those of rape-trauma victims (discussed later).

TABLE 5-1

COMPARISON OF CHARACTERISTICS OF POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS SYNDROME, BATTERED WOMAN SYNDROME, AND RAPE-TRAUMA SYNDROME

∗Modified from American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed. rev.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

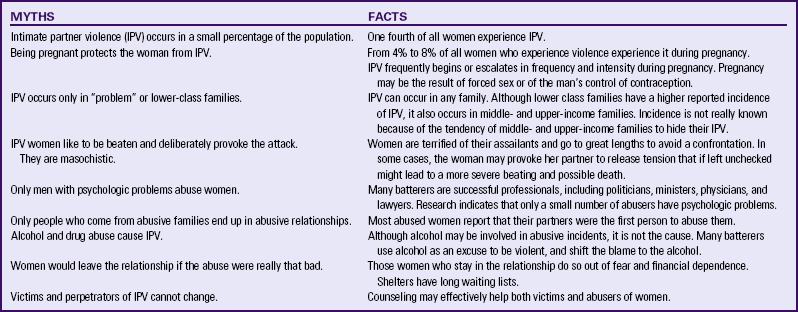

Leaving an abusive relationship is extremely difficult and the most dangerous time because most homicides occur shortly after separation (Campbell, 2004b). Health professionals can become frustrated by women they see repeatedly who have numerous signs of abuse but seem unable to liberate themselves from the battering relationships. As with other human dynamics that are not easily explained, health professionals and others may rationalize the woman’s behaviors to justify their own uninvolvement. A number of misconceptions are used to account for the woman’s perceived self-destructive behavior. If nurses and other professionals believe these misconceptions, they may become judgmental (such as blaming the victim) or respond in unhelpful ways, rather than being empathic and empowering women to take control over their lives (Westbrook, 2009). Empowerment is built on respect for the woman. Providing supportive empathy, validation, and information that can be lifesaving are empowering behaviors. Table 5-2 lists some myths and facts about IPV.

TABLE 5-2

MYTHS AND FACTS ABOUT INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE

Sources: Gelles, R. (1997). Intimate violence in families (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (1997). Alcohol, violence, and aggression. Alcohol Alert, 38, 1-6; National Women’s Health Information Center. (2002). Violence against women. Available at www.4woman.gov/violence/index.cfm. Accessed January 24, 2010.

Cultural Considerations

IPV is seen in all races, ethnicities, religions, and socioeconomic backgrounds (Breiding, Ziembroski, & Black, 2009; Mitchell & Anglin, 2009). In the United States, Caucasian women report less IPV than do non-Caucasians. Native American and Alaska Native women report significantly more instances of IPV than do women of any other racial background; Asian women report significantly less IPV than do other racial groups (Montalvo-Liendo, 2009; Tjaden & Thoennes, 2006). Reporting rates may not reflect the magnitude of the problem because many women do not disclose violence because of fear, embarrassment, or not having been asked by those from whom they seek help.

There is a growing official acknowledgment of IPV across the globe. In 1994 the United States enacted the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) followed by Guatemala and El Salvador in 1996, China in 1997, Colombia in 2000 and Japan in 2001. Mexico passed its first law in 2007 (Montalvo-Liendo, 2009). Women from almost all cultures—Asian women, Mexican immigrants, and Vietnamese—identify fear as a common factor in IPV. An important cultural consideration relates to refugees and immigrants. Immigrant women face unique challenges related to their non-citizen status as well as unfamiliarity with the health care and legal systems. The objectification of women and power inequalities in human social arrangements support the abuse of women. These are especially apparent in any social or cultural system of oppression. The cross-cultural meaning of violence is difficult to ascertain because cultures also differ in their perceptions and definitions of abuse. Accurate data about the incidence and prevalence of violence in ethnic groups are challenging because they are infrequently represented in research studies; violence may be underreported as a result of cultural norms. For example, groups that distrust police or immigration officials may not report abuse because they fear the repercussions.

The nurse must be sensitive to immigrant women and their intimate partners because acculturation is gradual, and cultural expectations from their birth countries may heavily influence beliefs and behaviors (Shiu-Thornton, Senturia, & Sullivan, 2005). Nurses must consider all forces that shape the woman’s identity—ethnicity, race, class, language, citizenship, religion, and culture—while recognizing that abuse is against the law and injurious to the health and well-being of women and children (and men). More than basic awareness of cultural influences on violence toward women is helpful to the nurse who seeks to be more sensitive to the needs of women whose cultural experiences differ from the nurse’s own. Becoming familiar with the client’s cultural influences and increasing the numbers of nurses from various ethnic groups will increase the opportunity to provide culturally appropriate care.

African-American Culture

The African-American culture supports unity among humans, nature, and the spiritual world, and social connectedness and relatedness as important norms. African-American men are more likely to be psychologically, socially, and economically oppressed and discriminated against. Violence may occur more frequently as a result of anger generated by environmental stresses and limited resources (Campbell, D., Sharps, Gary, Campbell, & Lopez, 2002). No valid evidence of greater violence seems to exist in this population although African-American women tend to report violence at a slightly higher rate than do Caucasian women (McFarlane, Groff, O’Brien, & Watson, 2005). The devalued status of the female survivor, racial stereotype and fear of putting another African-American man in jail, may be barriers to African-American women seeking and receiving help (Morrison, Luchok, Richter, & Parra-Medina, 2006).

Hispanic (and Latino) Cultures

Hispanic (or Latino) describes someone whose country of origin is Mexico, the largest group at 65%, followed by Puerto Rico, Cuba, Spanish-speaking Central and South American countries, or other Spanish cultures (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006). When data are collected, Americans who are of Hispanic descent may be grouped with those born in other countries. Thus Hispanics range from newly immigrated and strongly influenced by their native culture to second-generation Americans steeped in U.S. popular culture. It is difficult to generalize on culture among these groups.

Hispanics as a group are described as family oriented with a strong family network in which unity, cooperation, respect, and loyalty are important. Traditional families, as with most immigrant groups, are very hierarchic, with authority often given to older adults, parents, and men. Sex roles are clearly delineated. Hispanics in the United States have been found to have the same rate of IPV as non-Hispanic women; and in one study, researchers found that they had significantly more mental health issues than non-Hispanic women who experienced IPV (Bonomi, Anderson, Cannon, Slesnick, & Rodriguez, 2009). Another difference is in the characteristics of the abusive relationship. In one study the partners of Hispanic women were more likely to have alcohol problems and to force sex but less likely to own a gun, use illegal drugs, or threaten suicide than non-Hispanics in abusive relationships (Glass, Perrin, Hanson, Mankowski, Bloom, & Campbell, 2009).

Native American Culture

Empiric evidence about abuse in the Native American culture is limited (Duran, Oetzel, Parker, Malcoe, Lucero, & Jiang, 2009). Research indicates the IPV occurs within the context of complex racial and unique sociocultural factors. Native American and Alaska-Native women report the highest rates of IPV in the United States; however, research is needed to determine whether the rate is higher in these women, or the rate of reporting is higher (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2006). Oetzel and Duran (2004) proposed an ecological framework to guide health care providers in understanding the causes and possible areas for intervention with Native American and Alaska Natives.

Asian Women

Asian women are often artificially grouped into one homogeneous group despite their vast and varied cultures.

Reasons for not disclosing IPV vary across cultures. Women from South Asia, including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, India, the Maldives, Nepal, and Pakistan, were worried about immigrant laws, were concerned about family honor, and believed that men had the right to abuse. Urban women from Bangladesh were fearful of being killed, felt helpless, and were worried about community retaliation and judgment (Naved, Azim, Bhuiya, & Persson, 2006). Jordanian women expressed fear, shame, religious beliefs, and lack of social support as reasons for not disclosing. The majority of Jordanian men and women deny the problem of wife abuse and oppose discussions of it in society, a reflection of this patriarchal society (Btoush & Haj-Yahia, 2008). Chinese women worried they would be criticized and were fearful of not saving face and disappointing relatives. Japanese women felt shame, were fearful of escalating violence, and victim blaming (Yoshihama, 2002). Vietnamese women put the needs of the family before their individual needs and kept the woman’s role subordinate to men to maintain harmony in the family (Shiu-Thornton et al., 2005).

Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy

IPV has serious consequences for the health of the mother and fetus. The prevalence of IPV during pregnancy is estimated at 4% to 8% (Martin, Mackie, Kupper, Buescher, & Moracco, 2001). It is more common than preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or an abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) test in pregnancy (Chambliss, 2008). Women who are abused before pregnancy may continue to be abused during the pregnancy.

Some clinicians believe that abuse may begin or escalate with pregnancy, but some studies suggest that both lethal and nonlethal abuse may actually decrease during pregnancy in some couples (Taylor & Nabors, 2009). In a small longitudinal study Macy, Martin, Kupper, Casanueva, & Guo (2007) found that rates of physical abuse among women with a history of recent abuse peaked during the first 3 months of pregnancy, then declined while women without a recent history of abuse had low rates of abuse during pregnancy. Thus, pregnancy may be protective for some women. In the same study, rates of psychologic abuse were highest in the first month after the birth, as was sexual abuse.

It is clear that IPV has negative effects on pregnancy. Maternal complications of depression, suicide, low weight gain, infections, and substance abuse have been related to being in an abusive relationship (Campbell, J. et al., 2002; Plichta, 2004). Gastrointestinal symptoms may occur from chronic stress, as may hypertension and chest pain. Other conditions are gynecologic problems such as STIs, bleeding, urinary tract infections, chronic pelvic pain, and genital trauma. A history of abuse prior to the pregnancy is associated with a higher risk of postpartum depression (Records & Rice, 2009).

Homicide is the leading cause of trauma death in pregnancy and postpartum (Chang, Berg, Saltzman, & Herndon, 2005; Horon & Cheng, 2005). Estimates are that 16% to 66% of pregnancy-related murders are by intimate partners (Martin, Macy, Sullivan, & Magee, 2007). IPV may be a risk factor for suicide attempts in pregnancy (Martin et al.).

Not only is physical abuse harmful to the mother, the risk of fetal injury also is very high. Trauma may result in low birth weight, preterm birth, fetal demise, premature separation of placenta, hemorrhage, infections, and other trauma-related injuries (Chambliss, 2008; Morland, Leskin, Block, Campbell, & Friedman, 2008). Pregnant adolescents may be abused at higher rates than are adult women, so they should be considered at high risk. There is a greater likelihood of unintended pregnancy in adolescents who often delay prenatal care (Plichta, 2004). Physical abuse and pregnancy in teenagers constitute a particularly difficult situation. Adolescents may be more trapped in the abusive relationship than adult women because of their inexperience. They may ignore the violence because the jealous and controlling behavior is interpreted as love and devotion. Because pregnancy in adolescent girls is frequently the result of sexual abuse, feelings about the pregnancy should be assessed. Teens report abuse from partners, former partners, and family members (Renker, 2002). Many who had been abused through the pregnancy also were abused afterward, and others who were not abused during pregnancy reported initial abuse after giving birth (Harrykissoon, Rickert, & Wiemann, 2002). Adolescents have been found to be at very high risk for abuse in the postpartum period. Quinlivan and Evans (2005) found that IPV and drug abuse in adolescents affected maternal attachment and infant temperament.

Care Management

Care of the woman experiencing IPV must begin with the nurse’s self-assessment. An exploration of attitudes toward women in abusive situations, awareness of feelings that may result in judgmental communication, and knowledge about the many aspects of IPV are preparations for care. Dienemann, Glass, and Hyman (2005) found that women desired health care providers to take an active role, that is, to provide documentation, protection, immediate response, to give options, and to be there for the survivor later. They also wanted to be treated with respect and concern.

Exactly what drives a woman to seek assistance is not clear. Women who belong to any of the following three groups are more likely to seek assistance: (1) women who are beaten frequently and severely; (2) those who have not experienced or witnessed family violence in their family of origin; and (3) those who see an alternative to life in an abusive relationship, specifically women with jobs. Sometimes women seek help after their children have been hurt or when their children start imitating the abuser’s behavior.

Women experiencing IPV may be reluctant to seek help for various reasons, including the need to avoid the stigma associated with the nature of the family violence; the fear that they will not be believed; the fear of reprisal from their husbands or partners; and in some states in which battering is a reportable crime, the desire to avoid involvement with police (see Legal Tip: Mandatory Reporting of Domestic Violence).

Clients in any women’s health care setting may be at risk for abuse and nurses are encouraged to assess for abuse in all women entering the health care system (McFarlane et al., 2002) (see Nursing Process box). Health care providers may be the first and only contact that a socially isolated woman makes with someone outside the relationship. Failure to identify IPV and to recognize the risk of serious injury or even death further endangers the lives of women and their children.

A woman suspected of being emotionally abused or physically threatened or abused should be examined and interviewed in private, and, if her partner is male, she may feel safer and more comfortable with a female health care provider. Nurses should never ask about abuse with a partner present because this may place the woman in danger. When one is taking a psychosocial history, the following information provides clues to violence or potential for violence: does the woman feel safe at home with her partner, how does the woman and her partner resolve conflict, what happens when the woman’s partner becomes angry, does fighting occur during disagreements, and if fighting occurs, does it ever escalate to restraining or physical means. It may help the woman to disclose information if these events are normalized by the nurse stating, “Many people [families] have difficulty in expressing anger or dealing with conflict. What is that like for you and your partner?” The nurse listens for any evidence of power and control in the relationship. While inquiring about past trauma or injuries, the nurse also should ask directly if the woman has been injured by her husband or intimate partner. At least the following questions should be asked:

• Are you with a spouse or partner who threatens or physically hurts you?

• Within the past year or in this pregnancy has anyone hit, slapped, kicked, or otherwise hurt you?

• Has anyone forced you to have sexual activities that made you uncomfortable? (American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2010). These questions give a woman permission to disclose sensitive information.

Assessment tools can be a part of the interview that give the nurse useful information. Patterns of violence change over time in some relationships, and reports show an increase in the identification of victims of domestic violence when the nurse inquires at each visit whether a woman has been hit or threatened since her last visit (Macy et al., 2007; Walton-Moss & Campbell, 2002). Cues to abuse are delay in seeking medical assistance (hours or days), missed appointments, vague explanation of injuries, nonspecific somatic complaints, social isolation, lack of eye contact, a husband or partner who does not want to leave the woman alone with the primary health care provider, and substance abuse.

In the United States a pregnant woman is often accompanied by her husband to the antepartum appointment. This is especially true if the woman does not speak English and the husband does. The use of an interpreter is preferred; the interpreter needs to be a woman who can communicate the nurse’s sensitivity and concern accurately. All women should be seen for some part of the visit without the partner present.

For some abused women, day-to-day survival is exhausting. They may cope by denying to the nurse the probabilities of impending abuse, severity of injury, future recurrence, and death. Women may be embarrassed about their abusive relationships and believe the abuse is caused by their inadequacies. Other abused women may cope by denying to themselves that their partner’s violent behavior will happen again. By asking a woman directly about abuse, telling her that similar injuries are common in women who have been abused, and pointing out that she is not responsible for another’s violent behavior, the nurse may help her disclose the violence she is experiencing. During pregnancy the nurse should assess for abuse at each prenatal visit and on admission to labor, although it is not appropriate to ask questions during active labor. Assessment for abuse continues after birth because abuse may begin or escalate then; well-baby clinics may be important settings for screening women for abuse (Martin et al., 2001).

Assessment techniques are straightforward but do require the nurse to be comfortable asking about this socially stigmatized issue. Of utmost importance for women who disclose that they experience IPV (or sexual assault, another hidden trauma) is to validate that you have heard her. Assure her that it is not her fault. The nurse might say something like, “What you have just told me is very important, I’m glad you have shared this with me; no one has the right to hurt you this way.” It can be demoralizing when, despite taking the risk to disclose, the health care provider does not acknowledge the import of what has just been said. The next important step is to establish the woman’s safety at the moment and in the future. Psychosocial assessment findings may include anxiety, insomnia, self-directed abuse, depression,

smoking, and drug or alcohol abuse (Downs & Rindels, 2004; Gerber, Gantz, Lichter, Williams, & McCloskey, 2005). During the physical examination, the woman should be observed for injuries to the face, breasts, abdomen, and buttocks. These injuries may be old or new and may range from minor bruising to serious. Other physical signs include fractures that required significant force or that would rarely occur by accident; multiple injuries at various stages of healing; and patterns left by whatever might inflict injury, such as teeth, utensils, fists, or hot objects.

Nursing Interventions

A therapeutic relationship and skillful interviewing help women disclose and describe their abuse. Language is important when talking with women. A major factor in addressing abuse is to identify the woman as a survivor, not a victim. Victim connotes someone who is harmed, is made to suffer, and may have little or no control. Survivor is an empowering term that connotes coping and decision making in relation to taking control of one’s life. The nurse might ask the woman how she sees herself. Women who have identified their abuse may appear passive, hostile, anxious, depressed, or hysterical because they may think they are at the mercy of the man’s temper. In addition, they may be embarrassed, afraid, angry, sad, and shocked. Transitioning to a different self-image takes time, persistence, and support. A tool that provides a framework for sensitive nursing interventions is the ABCDES of caring for the abused woman (Campbell & Furniss, 2002).

• A is reassuring the woman that she is not alone. The isolation and denigration by the abuser keep her from knowing that others are in the same situation and that health care providers can help.

• B is expressing the belief that violence against the woman is not acceptable in any situation and that it is not her fault; no one deserves to be hurt or mistreated. This may be the first step in empowering her to think about self-protection and acceptable boundaries.

• C is confidentiality of the information being shared, particularly because the woman may believe that if the abuse is reported, the perpetrator will retaliate (and in reality, this may happen). Explain the mandatory reporting laws, where applicable.

• D is for descriptive documentation and includes the following: (1) the woman’s quoted statement, “My husband punched me,” a clear statement by the woman about the abuse. It should not include her subjective opinion, such as “I provoked the abusive behavior”; (2) accurate descriptions of injuries and a history of the first, worst, and most recent incident of violence may be included; and (3) with the woman’s consent, evidence, or photographs (Box 5-2).

• E is for education, especially that violence is likely to recur and escalate. Education about options including community resources such as where a woman can be referred for help and information about local shelters; for example, National Domestic Violence/Abuse Hotline—800-799-SAFE. Ask if she knows how to obtain a restraining order.

• S is for safety, the most significant part of the intervention because one of the most dangerous times for a woman is when she decides to leave. Tell the woman to call 911 if she is in imminent danger, and to consider alerting neighbors to call the police if they hear or see signs of conflict. A safety plan should be developed. The safety plan will be adapted based on whether the woman chooses to stay in the relationship or leave. The woman may be conflicted and need support as she goes through a decision-making process (Glass, Eden, Bloom, & Perrin, 2009). The woman can be offered a telephone to call the shelter if this is an option she chooses. If she chooses to go back to the abuser, a safety plan includes necessities for a quick escape: a bag packed with personal items for an overnight stay (can be hidden or left with a neighbor), money or a checkbook, an extra set of car keys, and any legal documents to use for identification. Legal options, such as those for restraining orders or arrest of the perpetrator, also are important aspects of the safety plan. A restraining order can be obtained 24 hours a day from the county court or police department. Many communities have battered women’s hotlines where they can get counseling. Pennell and Francis (2005) discuss safety conferencing as a means of building the individual and collective strength to assist women to reshape connections, make sound choices, and promote their safety (see Nursing Care Plan).

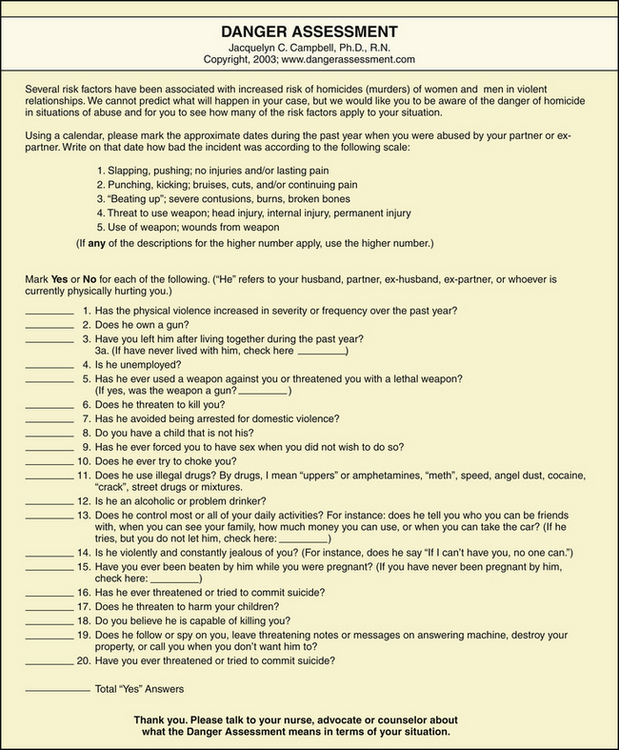

One part of safety planning is trying to sort out the potential danger in a relationship. A validated danger assessment tool (Fig. 5-3) was designed to assess the level of violence in a relationship and to identify abused women who are at risk of

FIG. 5-3 Danger assessment tool. (From Campbell, J. [2004]. Danger assessment. Available at www.dangerassessment.org. Accessed January 5, 2010; Campbell, J., Webster, D., & Glass, N. [2009]. The danger assessment: Validation of a lethality risk assessment instrument for intimate partner femicide. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(4), 653-674.)

being murdered (Campbell, 2004a; Campbell, Webster, & Glass, 2009). The nurse and the abused woman can go through the tool collaboratively. Online training and permission to use the tool are available at www.dangerassessment.org/WebApplication1/pages/product.aspx.

If the woman is pregnant, collaboration with maternity nurses who will be involved in her care during the pregnancy may be helpful. Each nurse can plan care that will point out the woman’s strengths and increase her self-esteem. The husband or partner may attend prenatal visits and classes and is included in other ways if the woman chooses to stay with him. The first days after birth are particularly crucial because the mother is physically and emotionally vulnerable and usually tired, and the baby’s crying may be intolerable to both the father and the mother. The danger of abuse to mother and child is acute during this time. Facilitating the woman’s establishment of a support network of maternity and pediatric staff, community health nurses, and shelter and parental crisis center personnel is important during this crucial period. Referral to resources and provision for follow-up examination by health care providers also should be part of the nursing intervention.

Many nurses become frustrated when a woman returns to a previously abusive situation (Davis, Park, Kaups, Bennink, & Bilello, 2003). It is important to remember that many victims have been abused for a long time, which may make it difficult for them to seek and accept help. Women in repeatedly abusive situations may have lost their ability to perceive the possibility of success and may have become very passive. In addition to understanding the many reasons women stay in abusive relationships, recognizing that the most dangerous period for a woman is when she is in the process of leaving may help nurses to be less judgmental about the woman’s dilemma.

A woman may indicate her readiness to leave the relationship when she believes that she is capable of planning for herself, investing in herself, and recognizing that the abuse is part of a continuing pattern. She also needs to believe that she will have economic and other resources to “make it” on her own. Going to a shelter may be an option; however, shelter stays are typically limited to 30 to 90 days, and therefore a long-term plan must be in place. Also, her being in a shelter may make the husband or partner angrier. Nurses can be helpful in directing women to sources of information, continuing to be expert listeners, and offering encouragement as women struggle in their decision-making process toward freedom and control in their lives.

Prevention

Screening is a common approach to preventing the progression of health problems. Currently there is insufficient evidence to say that universal screening prevents further incidents of IPV in asymptomatic women (MacMillan, Wathen, Jamieson, Boyle, Shannon, Ford-Gilboe, et al., 2009; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2004). Nevertheless, because the research is limited, and because screening studies were not paired with interventions, major health care organizations including ACOG continue to recommend universal screening of all women. Screening alone is not helpful but assessment with adequate intervention may be useful in improving outcomes (Klevens & Saltzman, 2009). Because IPV has been linked to many other health problems such as headaches, GI problems, chronic pain, arthritis, STIs, pelvic pain, substance abuse, depression, PTSD and suicide, women with any of these symptoms should be carefully assessed.

Nurses can make a difference in stopping the violence and preventing further injury. Educating women that abuse is a violation of their rights and facilitating their access to protective and legal services constitute a first step. Other measures that may help women to discourage the risk of abusive relationships are promoting assertiveness and self-defense courses; suggesting support and self-help groups that encourage positive self-regard, confidence, and empowerment; and recommending educational and skills-development classes that will enhance independence or at least the ability to take care of oneself (Pennell & Francis, 2005). Classes for learning English may be particularly helpful to immigrant women. Nurses can offer information on local classes. Preventive education with children encourages and teaches them androgynous gender roles: men and women are equal; both can be nurturing; and neither needs to dominate the other or to engage in violent behavior to have needs met. Helping children to gain problem-solving and conflict management skills may eliminate the need for violent solutions to life stresses. Encouraging schoolchildren to form and participate in Students Against Violence Everywhere (SAVE) groups, which is a nationwide pro-peace effort that promotes justice, respect, and love, gives them an appreciation for these qualities in all facets of life. Adolescents benefit from discussion about sex roles, their relationships, and the consequences of the “macho” concept. School nurses can be instrumental in developing and implementing informational activities for adolescents (Walton-Moss & Campbell, 2002). Other means of prevention are to advocate against violence in all arenas and to participate actively in promoting legislation and policies toward stopping violent acts.

Sexual Violence

Sexual violence is a broad term that encompasses a wide range of sexual victimization including sexual harassment, sexual assault, and rape. Sexual harassment includes unwelcome degrading sexual remarks, contact, or behavior such as exhibitionism that makes the work or other environment uncomfortable or difficult. Sexual assault refers to intentional unwanted completed or attempted touching of the victim’s genitals, anus, groin, or breasts, directly or through clothing as well as by voyeurism (Basile, Chen, Black, & Saltzman, 2007). It also includes exhibitionism, exposing someone to pornography or displays of images taken of the victim in a private context (National Institute of Justice, 2007). Rape is a legal term that is defined differently by each state. It usually refers to forced sexual intercourse or penetration of the mouth, anus, or vagina by a body part or object without consent; it may or may not include the use of a weapon. It involves the use of force, threats, or a victim who is incapable of giving consent. The term is a legal and not a medical one. Molestation consists of noncoital sexual activity between a child and an adolescent or adult. Statutory rape involves penetration as described above by a person who is 18 years or older of a person under the age of consent, and the specifics vary from state to state.

The National Survey on Crime reported 260,940 incidents of sexual assault and attempted or completed rapes (Violence Against Women Online Resources, 2010). Based on another national survey of 5000 women, researchers estimate that more than 1 million women from diverse ethnic and social backgrounds are raped each year in the United States (Kilpatrick, Resnick, Ruggiero, Conoscenti, & McCauley, 2007). Almost one third of all sexual assault victims report that the assault occurred during adolescence (McCauley, Amstadter, Danielson, Ruggiero, Kilpatrick, & Resnick, 2009). Rape may occur within intimate, casual, or work relationships. Rapists may be intimate partners or spouses. They may be family members or acquaintances such as friends, neighbors, or dates. Or they may be strangers, police, prison guards, or soldiers. Rape occurs in the general population, in institutional settings such as colleges, in the military, and in prisons.

Why Do Some Men Rape?

Multiple theories exist on the causes of sexual violence from the perspective of the perpetrator (Stinson, Sales, Becker, & American Psychological Association, 2008). Some risk factors for perpetrators include having themselves been sexually abused in childhood; seeing women as sex objects and viewing them negatively, with hostility, or as dangerous; supporting beliefs that justify rape such as male entitlement to sex or that a woman is asking or deserving to be raped because she dresses provocatively. Some perpetrators are conditioned to become aroused to forced sexual violence. Using violent pornography may normalize preexisting sexually aggressive impulses (Casey & Lindhorst, 2009).

Acquaintance rape involves persons who know one another such as friend, neighbor, family member, classmate, date, or acquaintance. If there is a relationship, then trust is violated. Victims may fear retaliation from the assailant or harassment from family or friends who know the person (Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network [RAINN], 2009).

Stranger rape is the least common type of rape. The assailant may be a total stranger who suddenly attacks the victim in a public place or in the home. Other stranger rapes occur when the assailant has brief contact with the victim prior to the assault, for example engaging the victim in conversation to earn trust at a bar or party. Women are more likely to report stranger rape than acquaintance rape (Jones, Wynn, Kroeze, Dunnuck, & Rossman, 2004).

Sexual assault and rape are considered forcible when there is threat or actual use of force on an unwilling victim. An incapacitated sexual assault or rape occurs when the victim is under the influence of alcohol or drugs, rendering the person unconscious or otherwise unable to give consent. Estimates are that as many as half of rapes are either drug facilitated or the result of self-induced intoxication. Alcohol is the most common drug associated with sexual assault (Hindmarch, ElSohly, Gambles, & Salamone, 2001). Alcohol makes it more difficult for women to identify potentially dangerous situations and to resist unwanted sexual advances. A drug-facilitated sexual assault occurs when alcohol and/or drugs are taken unwillingly or unknowingly. The use of date rape drugs such as flunitrazepam (Rohypnol, or “roofies”), gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), ketamine, and carisoprodol (Soma) incapacitate the victim and may produce amnesia. These drugs are potentiated by alcohol, and the combination can be lethal. The frequency that these drugs are used may be underestimated because they are rapidly excreted, and lab testing has to be done within a few hours of ingestion (Crawford, Wright, & Birchmeier, 2008). Signs indicating that a woman may have been drugged include having no recall after taking a drink laced with the drug, feeling as if sex has occurred but not having any memory of the incident, feeling more intoxicated than what would be a usual response to the amount of alcohol consumed, or feeling fuzzy on awakening.

Kilpatrick and coworkers (2007) found that only 16% of victims reported the assault to police. Many factors deter a woman from reporting the crime, so data regarding sexual assaults may underestimate the magnitude of the problem. Women do not report rape because of the associated stigma; embarrassment; guilt that in some way they provoked the assault; fear of retribution from the rapist or his friends; dread of being humiliated and figuratively “raped” again by the criminal justice system publicity; distrust of law enforcement; involvement in illegal substance use; and discouragement generated by the dismally small number of convictions. Rape survivors often fear the reactions of husbands, lovers, friends, family, and children and prefer to suffer alone.

Mental Health Consequences of Sexual Assault

Rape produces long-term mental health consequences similar to those experienced by combat veterans. Most sexual assaults result in minor physical injuries; genital trauma may or may not be apparent. However, the psychologic effect can be severe. Sexual assault and rape are associated with depression, rape-trauma syndrome (RTS) and PTSD, substance abuse, suicidality, and a host of physical disorders including chronic pelvic pain and sexual dysfunction. One third of women seek counseling as a direct result of their sexual assault (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2006).

Why is rape so traumatic? Victims may have been threatened by a weapon, pushed, shoved, overpowered, or coerced. The assailant may have threatened to return and kill the victim if the incident is reported to anyone. In the aftermath victims may be frightened, angry, embarrassed, or ashamed. They may feel betrayed if there was a preexisting relationship with the assailant. Some may withdraw, feeling socially isolated, unable to tell the people closest to them, fearful of being judged or rejected. Some victims are afraid to return to their homes, workplace, or wherever the assault happened. The emotional suffering can take over women’s lives and whereas some seek support from family, friends, health care professionals, or police, others may carry this experience silently, never telling anyone (Esposito, 2005).

Rape-Trauma

When humans experience fear, horror, or helplessness after a life-threatening traumatic event such as rape or combat there is an intense initial stress response. In the first few hours and days an initial neurobiologic dysregulation in the brain interferes with learning new information, making memories, responding to stress, and regulating the level of arousal. In some survivors this dysregulation and other neurobiologic changes persist (Heim & Nemeroff, 2009). For example, in most trauma survivors cortisol levels in the brain rise in response to stress. It appears from emerging research that in people who then develop PTSD, brain cortisol levels, rather than being elevated during stressful events, are low. Some theories suggest that the brain may become oversensitive to cortisol, and minor stress events may cause the person to overreact and major traumas may produce an underreaction (Wheeler, 2008). Variations in brain function and structure are important in understanding the trauma-related symptoms seen in some but not all rape victims. Why do some victims not recover? Suggested possibilities include genetic differences, neuroanatomic differences, sex differences, personality styles, past exposures to stress, and the characteristics and context of the specific trauma and subsequent experiences. Researchers are working on finding specific neurobiopsychologic strategies such as medications and/or therapies that can prevent and treat trauma sequelae like PTSD.

The neurobiologic changes that occur produce an array of symptoms. In the 1970s RTS was identified as a cluster of characteristic symptoms and related behaviors seen in the weeks and months after a rape (Burgess & Holmstrom, 2000). These researchers described three phases (see following). RTS is consistent with acute and chronic phases of PTSD (APA, 2000). Understanding the pattern of responses that victims may experience is crucial in helping the nurse provide woman-centered supportive and responsive care.

Acute Phase: Disorganization

According to Burgess and Holmstrom (2000) the assault itself marks the beginning of the acute phase of RTS, which can last for several days or up to 3 weeks. Reactions such as shock, denial, and disbelief are common. The rape survivor feels embarrassed, degraded, fearful, angry, and vengeful, and she may blame herself. The victim may feel unclean and want to bathe and douche, although this may destroy evidence. Fear is the primary feeling. Observable reactions may be controlled, expressed, or disoriented. In controlled emotions the survivor hides her emotions; has a subdued, calm demeanor; and seems to act as if nothing happened. She may answer questions and interact in a matter-of-fact way. Her affect seems incongruent with what she has just experienced. The second type of acute phase reaction is expressed emotions. Here the survivor may appear agitated, pacing, hysterical. She may be restless, crying, tense, or anxiously smiling. Her affect may change rapidly from crying to being calm and controlled. She relives the scene over and over in her mind and considers things she “should have done.” Shocked disbelief or disorientation marks the third type of reaction. The victim may feel disoriented, have difficulty concentrating or making decisions, and may have poor recall of the event. Physiologically she may be uncomfortable, experiencing skeletal muscle pain or tension, gastrointestinal irritability, sighing, hyperventilation, and flushing.

Outward Adjustment Phase

During the adjustment phase the survivor may appear to have resolved her crisis. She may return to a job or to maintaining a household, or both, but she is denying and suppressing her thoughts and feelings. She needs this time to regain some control in her life. She may move, change jobs, buy a weapon to protect herself, or install an alarm system in her home. She may not be able to stop talking about the assault, letting it dominate her life or she may minimize or suppress the event, refusing to discuss it, acting as if it did not happen. She may try to analyze the details of how it happened, trying to explain how it happened and what the rapist was thinking. She may seek safety by fleeing her job, her home, or making other radical changes. She may experience fear, anxiety, phobias, mood swings, anger and rage, depression, insomnia, hypervigilance, and continued flashbacks. She may withdraw from support systems and be afraid to leave her home or go to certain places. She may develop sexual problems.

Long-Term Process: Reorganization Phase

The third phase is reorganization. Denial and suppression are difficult to maintain. Disclosing personal thoughts and feelings has a profound effect on improving health and reducing stress. As a rape survivor’s suppression of feelings and emotions starts to deteriorate, she becomes depressed and anxious. Her own healthy spirit pressures her to discuss the rape with someone. Because she is losing her control of denial, her fears start to surface; she may be afraid to be alone or in a crowd or may fear being attacked from behind. Nightmares and eating disorders are common in these last two phases.

The recovery process may take years and can be difficult and painful. The victim has progressed through recovery when the physical distress and the constant memories of the rape have diminished. She no longer blames herself for what happened and can truly call herself a survivor. These phases are not necessarily linear and survivors may move back and forth between the phases. RTS may meet the criteria for PTSD and be formally diagnosed (see Table 5-1).

Collaborative Care

Nurses in women’s health care and EDs are most likely to see rape victims in the acute phase. However, all women who manifest any of the signs of other phases should be assessed for posttraumatic experiences (Esposito, 2006). It is important to remember that sexual assault acute care has a dual purpose. First and foremost is to address the health care needs of the woman. The second purpose is to facilitate the collection of evidence and documentation of findings for use by the justice system. Health care is the nurse’s first priority.

Facilities that provide initial treatment for rape victims vary in protocols and resources. In its 1992 guidelines, The Joint Commission (TJC) required EDs and ambulatory care departments to have protocols on physical assault; rape or sexual assault; and domestic abuse of older adults, spouses, partners, and children. These protocols must address client consent, examination, and treatment guidelines and the health care facility’s responsibility for collecting evidence, photographing injuries, and releasing evidence to law enforcement officials. In addition, the EDs and ambulatory care departments must provide to victims a referral list of community-based and private service agencies dealing with family violence. The nurse interacting with the sexual assault client should be guided by the particular treatment center’s protocol (Box 5-3). The first National Protocol for Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Exams, although failing to adequately address STIs and pregnancy prevention was important in identifying the unique roles of nurses including sexual assault nurse examiners (SANEs), physicians, police, forensic specialists, prosecutors, and counseling advocacy in the aftercare of a sexual trauma victim (Lewis-O’Connor, Franz, & Zuniga, 2005; U.S. Department of Justice & Office of Violence Against Women, 2004). Agency or state recommendations for care are continually evolving as new research and forensic techniques emerge.

Many treatment centers have initiated the use of SANEs as described in the above protocols. A SANE is educated in the specialty of forensic nursing and is prepared to examine clients; recognize, collect, and preserve evidence; counsel the client; link the client with vital community resources; follow up cases; and, if necessary, testify in court. When cared for by a SANE, victims receive better quality care, appropriate prophylaxis for infection and pregnancy and are more satisfied than when cared for in settings without SANEs (Campbell, 2008). Information on becoming a SANE, which currently requires a 40-hour course, is available at www.iafn.org. If a SANE is not available in a particular facility, TJC member organizations must implement a plan for educating an appropriate staff member about identifying, treating, and referring abuse victims. Additional resources may include a social worker who is called when a woman who has been raped is admitted. A local rape crisis center may have volunteers on call who may provide emotional support; provide transportation; help the woman interact with her family, friends, and various authorities; inform her of RTS; and find other resources for her as needed. Male volunteers may counsel male members of the victim’s family and her male friends.

Psychologic First Aid

When victims seek help from people in their social network, from the police or from health care settings, the response they get is critical to their healing process. The goal of supportive care is to help victims feel less threatened, safer and have lower levels of anxiety. We do not know which victims will go on to develop PTSD but we do know that negative experiences in the health care system are associated with an increase in PTSD. Negative feedback has a powerful impact on survivors, and can be experienced as secondary victimization (Campbell, 2008).

The nurse may be one of the first persons to talk with a victim of sexual trauma. Initial distress is not abnormal and most sexual assault victims are able to recover. Even though there is limited evidence for specific treatments to prevent PTSD in sexual assault victims, trauma experts suggest that one promising approach is Psychological First Aid (Litz, 2008). Psychological First Aid has eight core goals that are consistent with and can be easily adapted to nursing practice. They are to (1) respond when a survivor reaches out to you or when you initiate contact with the survivor, in a nonintrusive, compassionate, and helpful manner; (2) enhance the survivor’s safety and provide physical and emotional comfort; (3) stabilize by calming and orienting the survivor if she is emotionally overwhelmed; (4) identify immediate needs and concerns and gather information; (5) offer practical help in addressing needs; (6) offer to help establish contact with personal supports; (7) provide information about stress and coping responses to sexual assault; and (8) link the survivor with community and other services (National Child Traumatic Stress Network and National Center for PTSD, 2005; Ruzek, Brymer, Jacobs, Layne, Vernberg, & Watson, 2007). Nurses who understand postassault experiences can influence the responses of their nursing units, hospital, or institution and community.

The Sexual Assault Examination

Because sexual assault is a crime, the first nurse to see the sexually assaulted client must consider the need to preserve evidence (see Legal Tip: Collector of Evidence). However, the preservation of evidence should not overshadow a survivor’s rights to be treated as a human being with respect, courtesy, and dignity. Client-centered care takes into consideration the psychologic needs of the victim, and the nurse adapts the examination accordingly.

Any health care and/or evidence collection is done only with the permission of the woman. She should be informed of all the steps involved in the sexual assault examination, treatment, and follow-up care. Written, informed consent for medical care and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing must be obtained. In addition, consent must be obtained for collection and storage of sexual offense evidence, including forensic photography. A signed consent for release of evidence must be obtained. The woman may choose to stop her care or the evidence examination at any time. Informed consent includes information on what will happen during the examination, what tests will be done, what treatments can be offered, what risks occur without treatment, and what evidence collection may provide. It is important for the nurse to remember that the examination cannot determine if an assault (nonconsensual sexual encounter) has happened. That is a legal determination that happens in court. The examination provides information that may or may not be consistent with sexual contact. Not all sexual assaults produce trauma, and not all sexual trauma is nonconsensual.

History: History taking is an important step in early care. History includes a statement of the traumatic event whether or not evidence will be collected (Box 5-3). The woman needs privacy but should not be left alone. It is important to tell the woman that she is safe, that the incident is not her fault, and that she is not alone in what she has experienced. She also needs assurance of confidentiality and may need a great deal of support and patience in verbalizing the offender’s acts. For example, giving the woman permission to describe the situation however she chooses and restating what the client has said (without minimizing) tells the woman she has been heard and ensures that what the nurse documents accurately reflects what she said. It also is important to obtain sexual, gynecologic, and obstetric histories (see Chapter 4).