Assessment and Health Promotion

• Identify the structures and functions of the female reproductive system.

• Describe the menstrual cycle in relation to hormonal, ovarian, and endometrial response.

• Review the four phases of the sexual response cycle.

• Analyze barriers that may affect a woman’s decision to seek health care.

• Investigate adaptation of the history and physical examination for women with special needs.

• Examine signs of abuse, screening, and referral to community agencies.

• Describe the history and physical examination.

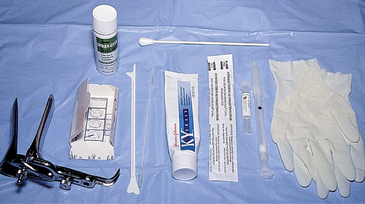

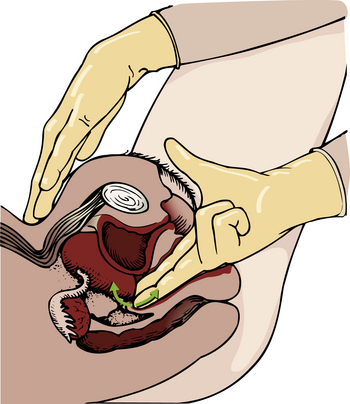

• Identify the steps for assisting with and collecting specimens for Papanicolaou (Pap) testing.

• Review client teaching of breast self-examination.

• Analyze conditions that increase health risks for women across the life span.

• Describe anticipatory guidance that prevents disease, promotes health and self-management.

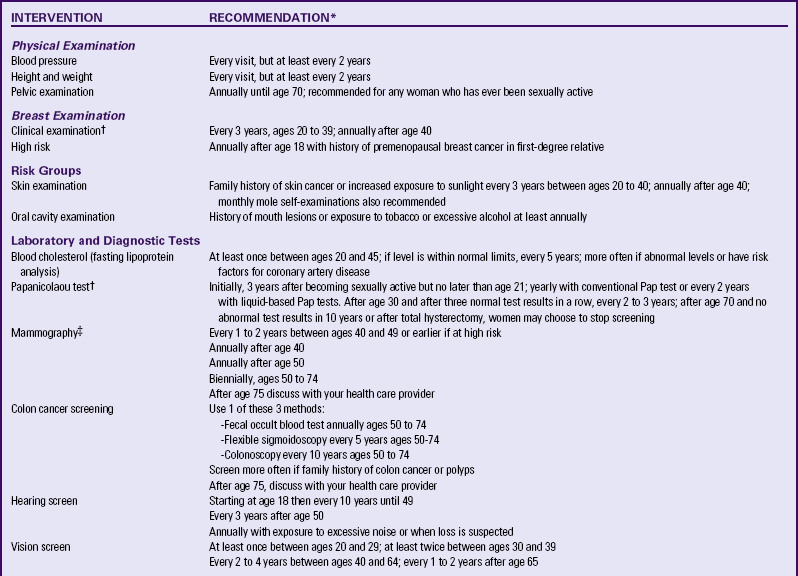

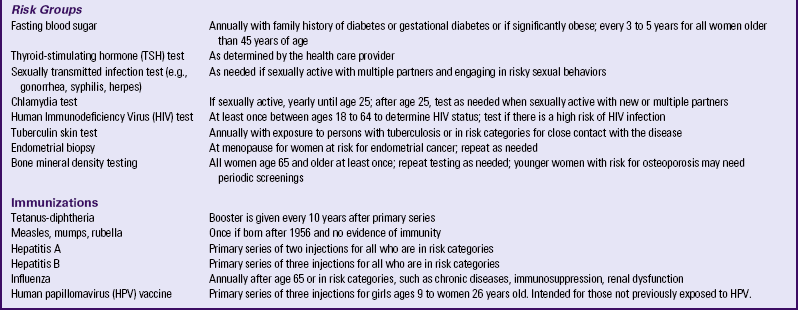

• Outline health-screening and immunization recommendations for women across the life span.

Most females initially enter the health care system because of a woman’s health-related concern such as the need for a Pap test, vaginal infection, irregular menses, contraceptive needs, or pregnancy. It is important for health care providers to recognize the need for health promotion, health maintenance, and disease prevention and to offer these services across the life span of women.

This chapter reviews female anatomy and physiology including the menstrual cycle. Physical assessment and screening for disease prevention for women are presented. Barriers to seeking health care and an overview of conditions that increase health risks across the life span such as cardiovascular disease, obesity, and nutritional deficiencies are described. Anticipatory guidance suggestions including nutrition, exercise, and health screenings for women across the life span are discussed.

Female Reproductive System

The female reproductive system consists of external structures visible from the pubis to the perineum and internal structures located in the pelvic cavity. The external and internal female reproductive structures develop and mature in response to estrogen and progesterone, starting in fetal life and continuing through puberty and the childbearing years. Reproductive structures atrophy with age or in response to a decrease in ovarian hormone production. A complex nerve and blood supply supports the functions of these structures. The appearance of the external genitals varies greatly among women. Heredity, age, race, and the number of children a woman has borne influence the size, shape, and color of her external organs.

External Structures

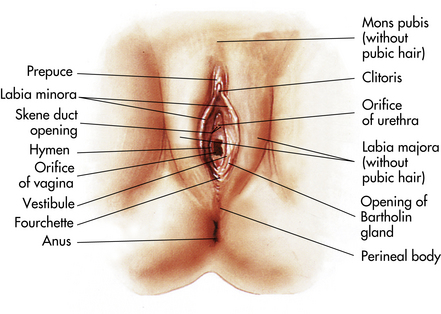

The external genital organs, or vulva, include all structures visible externally from the pubis to the perineum: the mons pubis, the labia majora, the labia minora, the clitoris, the vestibular glands, the vaginal vestibule, the vaginal orifice, and the urethral opening. The external genital organs are illustrated in Figure 4-1. The mons pubis is a fatty pad that lies over the anterior surface of the symphysis pubis. In the postpubertal female, the mons is covered with coarse, curly hair. The labia majora are two rounded folds of fatty tissue covered with skin that extend downward and backward from the mons pubis. The labia are highly vascular structures whose outer surfaces develop hair after puberty. They protect the inner vulvar structures. The labia minora are two flat reddish folds of tissue visible when the labia majora are separated. No hair follicles are in the labia minora, but many sebaceous follicles and a few sweat glands are present. The interior of the labia minora is composed of connective tissue and smooth muscle and supplied with extremely sensitive nerve endings. Anteriorly, the labia minora fuse to form the prepuce (hoodlike covering of the clitoris) and the frenulum (fold of tissue under the clitoris). The labia minora join to form a thin flat tissue called the fourchette underneath the vaginal opening at midline. The clitoris is located underneath the prepuce. It is a small structure composed of erectile tissue with numerous sensory nerve endings. During sexual arousal the clitoris increases in size.

The vaginal vestibule is an almond-shaped area enclosed by the labia minora that contains openings to the urethra, Skene glands, vagina, and Bartholin glands. The urethra is not a reproductive organ but is considered here because of its location. It usually is found about 2.5 cm below the clitoris. Skene glands are located on each side of the urethra and produce mucus, which aids in lubrication of the vagina. The vaginal opening is in the lower portion of the vestibule and varies in shape and size. The hymen, a connective tissue membrane, surrounds the vaginal opening. It can be perforated during strenuous exercise, insertion of tampons, masturbation, and vaginal intercourse. Bartholin glands (see Fig. 4-1) lie under the constrictor muscles of the vagina and are located posteriorly on the sides of the vaginal opening, although the ductal openings are usually not visible. During sexual arousal, the glands secrete a clear mucus to lubricate the vaginal introitus.

The area between the fourchette and the anus is the perineum, a skin-covered muscular area that covers the pelvic structures. The perineum forms the base of the perineal body, a wedge-shaped mass that serves as an anchor for the muscles, fascia, and ligaments of the pelvis. The pelvic organs are supported by muscles and ligaments that form a sling.

Internal Structures

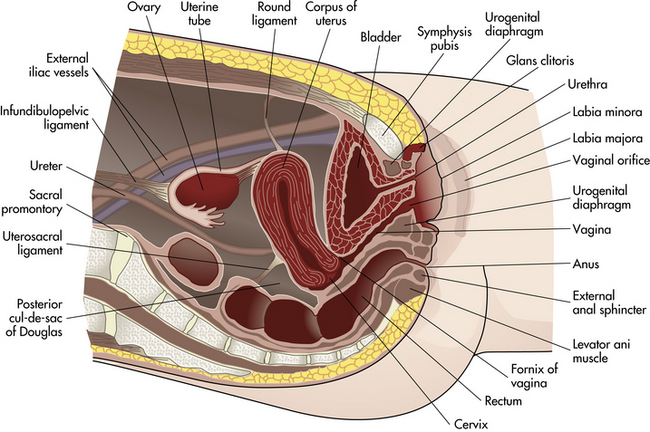

The internal structures include the vagina, the uterus, the uterine tubes, and the ovaries. The vagina is a fibromuscular, collapsible tubular structure that extends from the vulva to the uterus and lies between the bladder and rectum. During the reproductive years the mucosal lining is arranged in transverse folds called rugae. These rugae allow the vagina to expand during childbirth. Estrogen deprivation that occurs after childbirth, during lactation, and at menopause causes dryness and thinning of the vaginal walls and smoothing of the rugae. The vagina, particularly the lower segment, has few sensory nerve endings. Vaginal secretions are slightly acidic (pH 4 to 5) so that vaginal susceptibility to infections is reduced. The vagina serves as a passageway for menstrual flow, as a female organ of copulation, and as a part of the birth canal for vaginal childbirth. The uterine cervix projects into a blind vault at the upper end of the vagina. There are anterior, posterior, and lateral pockets called fornices (singular, fornix) that surround the cervix. The internal pelvic organs can be palpated through the thin walls of these fornices.

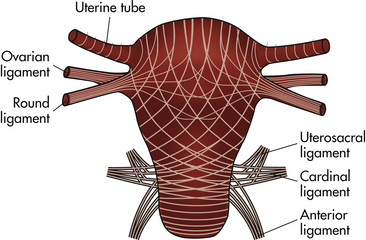

The uterus is a muscular organ shaped like an upside-down pear that sits midline in the pelvic cavity between the bladder and rectum and above the vagina. Four pairs of ligaments support the uterus: the cardinal, the uterosacral, the round, and the broad. Single anterior and posterior ligaments also support the uterus. The cul-de-sac of Douglas is a deep pouch, or recess, posterior to the cervix formed by the posterior ligament.

The uterus is divided into two major parts, an upper triangular portion called the corpus and a lower cylindric portion called the cervix (Fig. 4-2). The fundus is the dome-shaped top of the uterus and is the site at which the uterine tubes enter the uterus. The isthmus (lower uterine segment) is a short, constricted portion that separates the corpus from the cervix.

The uterus serves for reception, implantation, retention, and nutrition of the fertilized ovum and later of the fetus during pregnancy, and for expulsion of the fetus during childbirth. It also is responsible for cyclic menstruation.

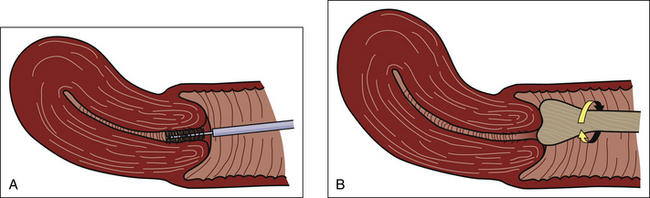

The uterine wall comprises three layers: the endometrium, the myometrium, and part of the peritoneum (membrane that covers the abdominal wall). The endometrium is a highly vascular lining made up of three layers, the outer two of which are shed during menstruation. The myometrium is made up of layers of smooth muscles that extend in three different directions (longitudinal, transverse, and oblique) (Fig. 4-3). Longitudinal fibers of the outer myometrial layer are found mostly in the fundus, and this arrangement assists in expelling the fetus during the birth process. The middle layer contains fibers from all three directions, which form a figure-eight pattern encircling large blood vessels. These fibers assist in ligating blood vessels after childbirth and control blood loss. Most of the circular fibers of the inner myometrial layer are around the site where the uterine tubes enter the uterus and around the internal cervical os (opening). These fibers help keep the cervix closed during pregnancy and prevent menstrual blood from flowing back into the uterine tubes during menstruation.

FIG. 4-3 Schematic arrangement of directions of muscle fibers. Note that uterine muscle fibers are continuous with supportive ligaments of uterus.

The cervix is made up of mostly fibrous connective tissues and elastic tissue, making it possible for the cervix to stretch during vaginal childbirth. The opening between the uterine cavity and the canal that connects the uterine cavity to the vagina (endocervical canal) is the internal os. The narrowed opening between the endocervix and the vagina is the external os, a small circular opening in women who have never been pregnant. The cervix feels firm (like the end of a nose) with a dimple in the center, which marks the external os.

The outer cervix is covered with a layer of squamous epithelium. The mucosa of the cervical canal is covered with columnar epithelium and contains numerous glands that secrete mucus in response to ovarian hormones. The squamocolumnar junction, where the two types of cells meet, is usually located just inside the cervical os. This junction also is called the transformation zone, the most common site for neoplastic changes (see Fig. 11-12); cells from this site are scraped for the Pap test (see later discussion).

The uterine tubes (fallopian tubes) attach to the uterine fundus. The tubes are supported by the broad ligaments and range from 8 to 14 cm in length. The tubes are divided into four sections: the interstitial portion is closest to the uterus; the isthmus and the ampulla are the middle portions; and the infundibulum is closest to the ovary. The uterine tubes form passages between the ovaries and the uterus for the passage of the ovum. The infundibulum has fimbriated ends, which pull the ovum into the tube. The ovum is pushed along the tubes to the uterus by rhythmic contractions of the muscles of the tubes and by the current that is produced by the movement of the cilia that line the tubes. The ovum is usually fertilized by the sperm in the ampulla portion of one of the tubes.

The ovaries are almond-shaped organs located on each side of the uterus below and behind the uterine tubes. During the reproductive years they are approximately 3 cm long, 2 cm wide, and 1 cm thick; they diminish in size after menopause. Before menarche each ovary has a smooth surface; after menarche they become nodular because of repeated ruptures of follicles at ovulation. The two functions of the ovaries are ovulation and hormone production. Ovulation is the release of a mature ovum from the ovary at intervals (usually monthly). Estrogen, progesterone, and androgen are the hormones produced by the ovaries.

The Bony Pelvis

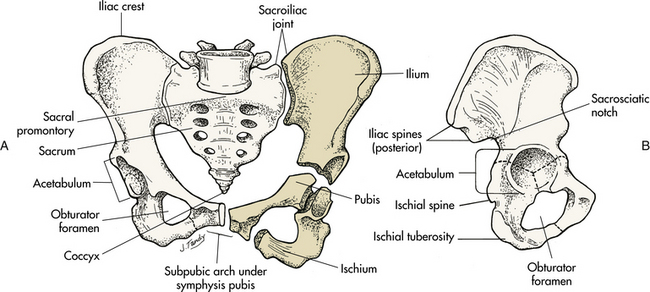

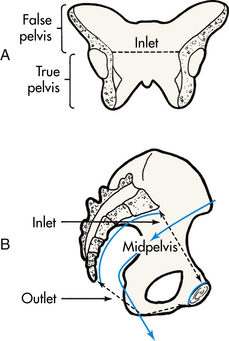

The bony pelvis serves three primary purposes: protection of the pelvic structures, accommodation of the growing fetus during pregnancy, and anchorage of the pelvic support structures. Two innominate (hip) bones (consisting of ilium, ischium, and pubis), the sacrum, and the coccyx make up the four bones of the pelvis (Fig. 4-4). Cartilage and ligaments form the symphysis pubis, the sacrococcygeal joint, and two sacroiliac joints that separate the pelvic bones. The pelvis is divided into two parts: the false pelvis and the true pelvis (Fig. 4-5). The false pelvis is the upper portion above the pelvic brim or inlet. The true pelvis is the lower, curved bony canal, which includes the inlet, the cavity, and the outlet through which the fetus passes during vaginal birth. The upper portion of the outlet is at the level of the ischial spines, and the lower portion is at the level of the ischial tuberosities and the pubic arch (see Fig. 4-4). Variations that occur in the size and shape of the pelvis are usually due to age, race, and sex. Pelvic ossification is complete at about age 20 years.

Breasts

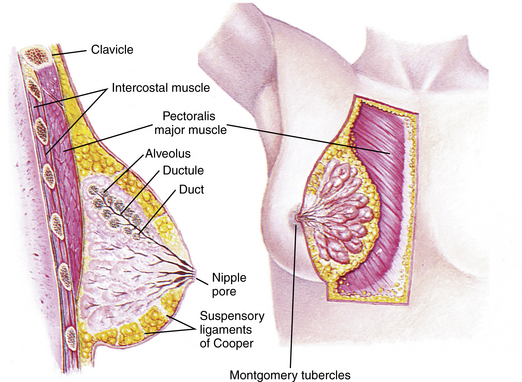

The breasts are paired mammary glands located between the second and sixth ribs (Fig. 4-6). About two thirds of the breast overlie the pectoralis major muscle, between the sternum and midaxillary line, with an extension to the axilla referred to as the tail of Spence. The lower third of the breast overlies the serratus anterior muscle. The breasts are attached to the muscles by connective tissue or fascia.

FIG. 4-6 Anatomy of the breast, showing position and major structures. (Adapted from Seidel, H., et al. [2011]. Mosby’s guide to physical examination [7th ed.]. St. Louis: Mosby.)

The breasts of healthy mature women are approximately equal in size and shape, but often are not absolutely symmetric. The size and shape vary depending on the woman’s age, heredity, and nutrition. However, the contour should be smooth, with no retractions, dimpling, or masses. Estrogen stimulates growth of the breast by inducing fat deposition in the breasts, development of stromal tissue (i.e., increase in its amount and elasticity), and growth of the extensive ductile system. Estrogen also increases the vascularity of breast tissue.

Once ovulation begins in puberty, progesterone levels increase. The increase in progesterone causes maturation of mammary gland tissue, specifically the lobules and acinar structures. During adolescence, fat deposition and growth of fibrous tissue contribute to the increase in the gland’s size. Full development of the breasts is not achieved until after the end of the first pregnancy or in the early period of lactation.

Findings from several studies using ultrasound imaging to investigate the anatomy of the breast found differences from previous descriptions (Geddes, 2007; Love & Barsky, 2004; Ramsay, Kent, Hartmann, & Hartmann, 2005). The following description incorporates these findings. Each mammary gland is made of a number of lobes that are divided into lobules. Lobules are clusters of acini. An acinus is a saclike terminal part of a compound gland emptying through a narrow lumen or duct. The acini are lined with epithelial cells that secrete colostrum and milk. Just below the epithelium is the myoepithelium (myo, or muscle), which contracts to expel milk from the acini.

The ducts from the clusters of acini that form the lobules merge to form larger ducts draining the lobes. Ducts from the lobes converge in a single nipple (mammary papilla) surrounded by an areola. The anatomy of the ducts is similar for each breast but varies among women. Protective fatty tissue surrounds the glandular structures and ducts. Cooper’s ligaments, or fibrous suspensory, separate and support the glandular structures and ducts. Cooper’s ligaments provide support to the mammary glands while permitting their mobility on the chest wall (see Fig. 4-6). The round nipple is usually slightly elevated above the breast. On each breast the nipple projects slightly upward and laterally. It contains 4 to 20 openings from the milk ducts. The nipple is surrounded by fibromuscular tissue and covered by wrinkled skin (the areola). Except during pregnancy and lactation, there is usually no discharge from the nipple.

The nipple and surrounding areola are usually more deeply pigmented than the skin of the breast. The rough appearance of the areola is caused by sebaceous glands directly beneath the skin called Montgomery tubercles. These glands secrete a fatty substance, thought to lubricate the nipple. Smooth muscle fibers in the areola contract to stiffen the nipple to make it easier for the breastfeeding infant to grasp.

Besides their function of lactation, breasts function as organs for sexual arousal in the mature adult.

The vascular supply to the mammary gland is abundant. In the nonpregnant state, the skin has no obvious vascular pattern. The normal skin is smooth without tightness or shininess. The skin covering the breasts contains an extensive superficial lymphatic network that serves the entire chest wall and is continuous with the superficial lymphatics of the neck and abdomen. In the deeper portions of the breasts, the lymphatics form a rich network as well. The primary deep lymphatic pathway drains laterally toward the axillae.

The breasts change in size and nodularity in response to cyclic ovarian changes throughout reproductive life. Increasing levels of both estrogen and progesterone in the 3 to 4 days before menstruation increase the vascularity of the breasts, induce growth of the ducts and acini, and promote water retention. The epithelial cells lining the ducts proliferate in number, the ducts dilate, and the lobules distend. The acini become enlarged and secretory, and lipid (fat) is deposited within their epithelial cell lining. As a result, breast swelling, tenderness, and discomfort are common symptoms just before the onset of menstruation. After menstruation, cellular proliferation begins to regress; the acini begin to decrease in size; and retained water is lost. After breasts have undergone changes numerous times in response to the ovarian cycle, the proliferation and involution (regression) are not uniform throughout the breast. In time, after repeated hormonal stimulation, small persistent areas of nodulations may develop. This normal physiologic change must be remembered when breast tissue is examined. Nodules may develop just before and during menstruation, when the breast is most active. The physiologic alterations in breast size and activity reach their minimal level about 5 to 7 days after menstruation stops.

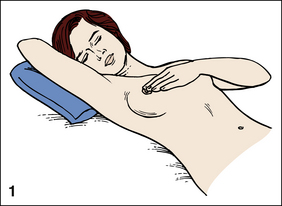

The best time for a woman who wishes to perform a breast self-examination (BSE) (palpation of breasts to detect changes in breast tissue) is during this phase of the menstrual cycle or whenever the breasts are not tender or swollen (see Teaching for Self-Management box: Breast Self-Examination).

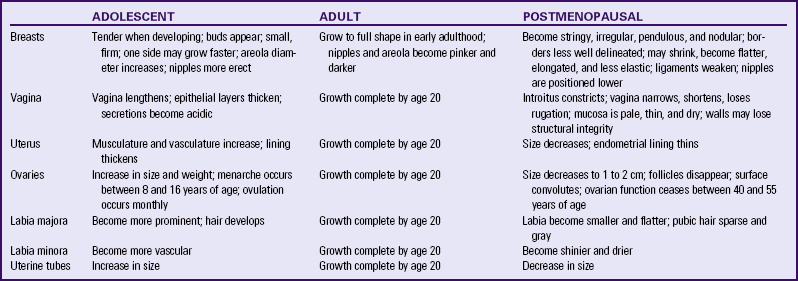

Table 4-1 compares the variations in physical assessment related to age differences in women.

Menstruation And Menopause

Nurses should be knowledgeable about menarche, the hypothalamic-pituitary cycle, the ovarian cycle, the endometrial cycle, other cyclic changes, and the climacteric because they provide care for women across the life span.

Menarche and Puberty

Although young girls secrete small, rather constant amounts of estrogen, a marked increase occurs between ages 8 and 11 years. The term menarche denotes first menstruation. Puberty is a broader term that denotes the entire transitional stage between childhood and sexual maturity. Increasing amounts and variations in gonadotropin and estrogen secretion develop into a cyclic pattern at least a year before menarche. In North America this occurs in most girls at about age 13 years.

Initially, for most women, periods are irregular, unpredictable, painless, and anovulatory (no ovum released from the ovary). After 1 or more years, a hypothalamic-pituitary rhythm develops, and the ovary produces adequate cyclic estrogen to make a mature ovum. Ovulatory (ovum released from ovary) periods tend to be regular, monitored by progesterone.

Although pregnancy can occur in exceptional cases of true precocious puberty, most pregnancies in young girls occur after the normally timed menarche. All young adolescents of both sexes would benefit from knowing that pregnancy can occur at any time after the onset of menses.

Menstrual Cycle

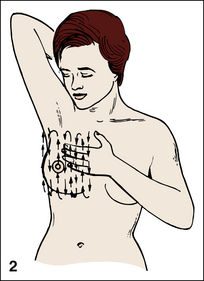

Menstruation is the periodic uterine bleeding that begins approximately 14 days after ovulation. It is controlled by a feedback system of three cycles: hypothalamic-pituitary, ovarian, and endometrial. The average length of a menstrual cycle is 28 days, but variations are normal. The first day of bleeding is designated day 1 of the menstrual cycle, or menses (Fig. 4-7). The average duration of menstrual flow is 5 days (range, 3 to 6 days), and the average blood loss is 50 ml (range, 20 to 80 ml), but these vary greatly.

For about 50% of women, menstrual blood does not appear to clot. The menstrual blood clots within the uterus, but the clot usually liquefies before being discharged from the uterus. Uterine discharge includes mucus and epithelial cells in addition to blood.

The menstrual cycle is a complex interplay of events that occur simultaneously in the endometrium, the hypothalamus, the pituitary glands, and the ovaries. The menstrual cycle prepares the uterus for pregnancy. When pregnancy does not occur, menstruation follows. The woman’s age, physical and emotional status, and environment influence the regularity of her menstrual cycles.

Hypothalamic-Pituitary Cycle

Toward the end of the normal menstrual cycle, blood levels of estrogen and progesterone decrease. Low blood levels of these ovarian hormones stimulate the hypothalamus to secrete gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). In turn, GnRH stimulates anterior pituitary secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). FSH stimulates development of ovarian graafian follicles and their production of estrogen. Estrogen levels begin to decrease, and hypothalamic GnRH triggers the anterior pituitary to release luteinizing hormone (LH). A marked surge of LH and a smaller peak of estrogen (day 12; see Fig. 4-7) precede the expulsion of the ovum from the graafian follicle by about 24 to 36 hours. LH peaks at about day 13 or 14 of a 28-day cycle. If fertilization and implantation of the ovum have not occurred by this time, regression of the corpus luteum follows. Levels of progesterone and estrogen decline, menstruation occurs, and the hypothalamus is once again stimulated to secrete GnRH. This process is called the hypothalamic-pituitary cycle.

Ovarian Cycle

The primitive graafian follicles contain immature oocytes (primordial ova). Before ovulation from 1 to 30 follicles begin to mature in each ovary under the influence of FSH and estrogen. The preovulatory surge of LH affects a selected follicle. The oocyte matures, ovulation occurs, and the empty follicle begins its transformation to the corpus luteum. This follicular phase (preovulatory phase; see Fig. 4-7) of the ovarian cycle varies in length from woman to woman. Almost all variations in ovarian cycle length are the result of variations in the length of the follicular phase (Fehring, Schneider, & Raviele, 2006). On rare occasions (i.e., 1 in 100 menstrual cycles), more than one follicle is selected, and more than one oocyte matures and undergoes ovulation.

After ovulation, estrogen levels decrease. For 90% of women only a small amount of withdrawal bleeding occurs, so it goes unnoticed. In 10% of women there is sufficient bleeding for it to be visible, resulting in what is termed midcycle bleeding.

The luteal phase begins immediately after ovulation and ends with the start of menstruation. This postovulatory phase of the ovarian cycle usually requires 14 days (range, 13 to 15 days). The corpus luteum reaches its peak of functional activity 8 days after ovulation, secreting the steroids estrogen and progesterone. Simultaneously with peak luteal functioning, the fertilized ovum is implanted in the endometrium.

If implantation does not occur, the corpus luteum regresses, steroid levels decrease, and the functional layer of the uterine endometrium is shed through menstruation.

Endometrial Cycle

The four phases of the endometrial cycle are (1) the menstrual phase, (2) the proliferative phase, (3) the secretory phase, and (4) the ischemic phase (see Fig. 4-7). During the menstrual phase shedding of the functional two thirds of the endometrium (the compact and spongy layers) is initiated by periodic vasoconstriction in the upper layers of the endometrium. The basal layer is always retained, and regeneration begins near the end of the cycle from cells derived from the remaining glandular remnants or stromal cells in this layer.

The proliferative phase is a period of rapid growth lasting from about the fifth day to the time of ovulation. The endometrial surface is completely restored in approximately 4 days, or slightly before bleeding ceases. From this point on, an eight- to tenfold thickening occurs, with a leveling off of growth at ovulation. The proliferative phase depends on estrogen stimulation derived from ovarian follicles.

The secretory phase extends from the day of ovulation to about 3 days before the next menstrual period. After ovulation larger amounts of progesterone are produced. An edematous, vascular, functional endometrium becomes apparent. At the end of the secretory phase the fully matured secretory endometrium reaches the thickness of heavy, soft velvet. It becomes luxuriant with blood and glandular secretions, a suitable protective and nutritive bed for a fertilized ovum.

Implantation of the fertilized ovum generally occurs about 7 to 10 days after ovulation. If fertilization and implantation do not occur, the corpus luteum, which secretes estrogen and progesterone, regresses. With the rapid decrease in progesterone and estrogen levels, the spiral arteries go into spasm. During the ischemic phase the blood supply to the functional endometrium is blocked, and necrosis develops. The functional layer separates from the basal layer, and menstrual bleeding begins, marking day 1 of the next cycle (see Fig. 4-7).

Other Cyclic Changes

When the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis functions properly, other tissues undergo predictable responses. Before ovulation, the woman’s basal body temperature (BBT) is often less than 37° C; after ovulation, with increasing progesterone levels, her BBT increases. Changes in the cervix and cervical mucus follow a generally predictable pattern. Preovulatory and postovulatory mucus is viscous (thick), so that sperm penetration is discouraged. At the time of ovulation, cervical mucus is thin and clear. It looks, feels, and stretches like egg white. This stretchable quality is termed spinnbarkeit (see Chapter 8). Some women have localized lower abdominal pain called mittelschmerz that coincides with ovulation. Some spotting may occur.

Prostaglandins

Prostaglandins (PGs) are oxygenated fatty acids classified as hormones. The different kinds of PGs are distinguished by letters (PGE, PGF), numbers (PGE2), and letters of the Greek alphabet (PGF2α).

Prostaglandins are produced in most organs of the body, including the uterus. Menstrual blood is a potent prostaglandin source. PGs are metabolized quickly by most tissues. They are biologically active in minute amounts in the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, respiratory, urogenital, and nervous systems. They also exert a marked effect on metabolism, particularly on glycolysis. Prostaglandins play an important role in many physiologic, pathologic, and pharmacologic reactions. PGF2α, PGE4, and PGE2 are most commonly used in reproductive medicine.

Prostaglandins affect smooth muscle contractility and modulation of hormonal activity. Indirect evidence suggests that PGs have an effect on ovulation, fertility, changes in the cervix, and cervical mucus that affect receptivity to sperm, tubal and uterine motility, sloughing of endometrium (menstruation), onset of abortion (spontaneous and induced), and onset of labor (term and preterm).

After exerting their biologic actions, newly synthesized PGs are rapidly metabolized by tissues in such organs as the lungs, the kidneys, and the liver.

Prostaglandins may play a key role in ovulation. If PG levels do not increase along with the surge of LH, the ovum remains trapped within the graafian follicle. After ovulation, PGs may influence production of estrogen and progesterone by the corpus luteum.

The introduction of PGs into the vagina or into the uterine cavity (from ejaculated semen) increases the motility of uterine musculature, which can assist the transport of sperm through the uterus and into the oviduct.

Prostaglandins produced by the woman cause regression of the corpus luteum, regression of the endometrium, and sloughing of the endometrium, resulting in menstruation. PGs increase myometrial response to oxytocic stimulation, enhance uterine contractions, and cause cervical dilation. They may be a factor in the initiation of labor, the maintenance of labor, or both. They also may be involved in dysmenorrhea (see Chapter 6) and preeclampsia-eclampsia (see Chapter 27).

Climacteric and Menopause

The climacteric is a transitional phase during which ovarian function and hormone production decline. This phase spans the years from the onset of premenopausal ovarian decline to the postmenopausal time when symptoms stop. Menopause (from the Latin mensis, month, and Greek pausis, to cease) refers only to the last menstrual period. Unlike menarche, however, menopause can be dated with certainty only 1 year after menstruation ceases. The average age at natural menopause is 51.4 years, with an age range of 35 to 60 years. Perimenopause is a period preceding menopause that lasts about 4 years. During this time, ovarian function declines. Ova slowly diminish, and menstrual cycles may be anovulatory, resulting in irregular bleeding. The ovary stops producing estrogen, and eventually menses no longer occur.

Sexual Response

The hypothalamus and anterior pituitary gland in females regulate the production of FSH and LH. The target tissue for these hormones is the ovary, which produces ova and secretes estrogen and progesterone. A feedback mechanism between hormone secretion from the ovaries, the hypothalamus, and the anterior pituitary aids in the control of the production of sex cells and steroid sex hormone secretion.

Although the first outward appearance of maturing sexual development occurs at an earlier age in females, both females and males achieve physical maturity at approximately age 17 years; however, individual development varies greatly. Anatomic and reproductive differences notwithstanding, women and men are more alike than different in their physiologic response to sexual excitement and orgasm. For example, the glans clitoris and the glans penis are embryonic homologues. Little difference exists between female and male sexual response; the physical response is essentially the same whether stimulated by coitus, fantasy, or masturbation. Physiologically, according to Masters (1992), sexual response can be analyzed in terms of two processes: vasocongestion and myotonia.

Sexual stimulation results in an increase in circulation to circumvaginal blood vessels (lubrication in the female), causing engorgement and distention of the genitals. Venous congestion is localized primarily in the genitals, but it also occurs to a lesser degree in the breasts and other parts of the body. Arousal is characterized by myotonia (increased muscular tension), resulting in voluntary and involuntary rhythmic contractions. Examples of sexually stimulated myotonia are pelvic thrusting, facial grimacing, and spasms of the hands and feet (carpopedal spasms).

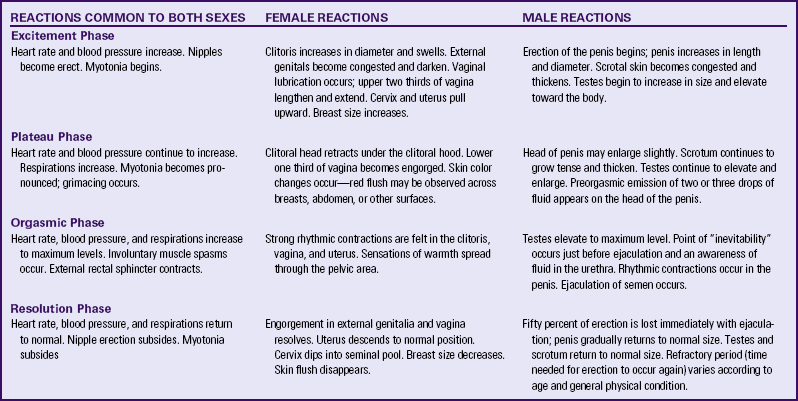

The sexual response cycle is divided into four phases: excitement phase, plateau phase, orgasmic phase, and resolution phase. The four phases occur progressively, with no sharp dividing line between any two phases. Specific body changes take place in sequence. The time, intensity, and duration for cyclic completion also vary for individuals and situations. Table 4-2 compares male and female body changes during each of the four phases of the sexual response cycle.

Reasons for Entering the Health Care System

Women’s health assessment and screening focus on a systems evaluation, beginning with a careful history and physical examination. During the assessment and evaluation, the responsibilities for self-management, health promotion, and enhancement of wellness are emphasized. Nursing care includes assessment, planning, education, counseling, and referral as needed, as well as commendations for good self-care that the woman has practiced. This enables women to make informed decisions about their own health care.

Preconception Counseling and Care

Preconception health promotion provides women and their partners with information that is needed to make decisions about their reproductive future. Preconception counseling guides couples on how to prevent unintended pregnancies and to achieve pregnancy when desired, stresses risk management, and identifies healthy behaviors that promote the well-being of the woman and her potential fetus (Moos, 2006).

All providers who treat women for well-woman care or other routine care should incorporate preconception health screening as part of the routine care for women of reproductive age (Johnson, Posner, Biermann, Cordero, Atrash, Parker, et al., 2006). The initiation of activities that promote healthy mothers and babies must occur before the period of critical fetal organ development, which is between 17 and 56 days after fertilization. By the end of the eighth week after conception and certainly by the end of the first trimester, any major structural anomalies in the fetus are already present. Because many women do not realize that they are pregnant and do not seek prenatal care until well into the first trimester, the rapidly growing fetus may be exposed to many types of intrauterine environmental hazards during this most vulnerable developmental phase.

Preconception care is important for women who have had a problem with a previous pregnancy (e.g., miscarriage, preterm birth). Although causes are not always identifiable, in many cases, problems can be identified and treated and may not recur in subsequent pregnancies. Preconception care is also important to minimize fetal malformations. For example, the woman may be exposed to teratogenic agents such as drugs, viruses, and chemicals, or she may have a genetically inherited disease. Preconception counseling can educate the woman about the effects of these agents and diseases, which can help prevent harm to the fetus or allow the woman to make an informed decision about her willingness to accept potential hazards should a pregnancy occur (Atrash, Johnson, Adams, Cordero, & Howse, 2006).

A model for preconception care of women of reproductive age targets all women from menarche to menopause at every encounter, not just in maternity and women’s health. Providing optimal health care for women whether or not they desire to conceive can result in a high level of preconception wellness (Moos, 2006). Suggested components of preconception care, such as health promotion, risk assessment, and interventions, are outlined in Box 4-1.

Pregnancy

A woman’s entry into health care is often associated with pregnancy, either for diagnosis or for actual care. The possibility of pregnancy is realized most commonly when a woman is late with her menses. If she is pregnant, it is desirable for a woman to enter prenatal care within the first 12 weeks. This allows early pregnancy counseling, especially for the woman who has had no preconception care. Major goals of prenatal care are found in Box 4-2 and should be initiated at the first visit. Extensive discussion of pregnancy is found in Chapter 15.

Well-Woman Care

Current trends in the health care of women have expanded beyond a reproductive focus. A holistic approach to women’s health care includes a woman’s health needs throughout her lifetime. This view goes beyond simply her reproductive needs. This restructuring places women’s health within the primary health care delivery system. Women’s health assessment and screening focus on a multisystem evaluation emphasizing the maintenance and enhancement of wellness.

Many women first enter the health care delivery system for a Pap test or contraception. Visits to the nurse may be their only contact with the system unless they become ill. Some women postpone examination until a specific need arises, such as pregnancy, pain, abnormal bleeding, or vaginal discharge.

Health care needs vary with culture, religion, age, and personal differences. The changing responsibilities and roles of women, their socioeconomic status, and their personal lifestyles also contribute to differences in the health and behavior of women. Employment outside of the home, physical disability, inadequate or no health insurance, divorce, single parenthood, and sexual orientation also can affect women’s ability to seek and receive health care in clinical settings. As women age, many continue to address their primary health care needs within their established gynecologic care setting; therefore, well-women’s health care should include a complete history, physical examination, age-appropriate screening, and health promotion.

Fertility Control and Infertility

As women become more informed about themselves and their health care, they are more willing to seek counseling and contraception appropriate to their varied and specific needs. Some women first enter the health care system to obtain such advice. More than half of the pregnancies in the United States each year are unintended, many even with contraception use (Trussell, 2007). Education is the key to encouraging women to make family planning choices based on preference and actual benefit-to-risk ratios. Providers can influence the user’s motivation and ability to use the method correctly (see Chapter 8 for further discussion of contraception).

The concept of health promotion applies to contraception, as can be seen in Box 4-3. The nurse can influence women positively regarding the need for child spacing, methods of family planning that are consistent with religious and personal preferences, noncontraceptive benefits of certain methods, the appropriate use of methods selected, and the protection of future fertility when so desired.

Women also enter the health care system because of their desire to achieve a pregnancy. Approximately 15% of couples in the United States have some degree of infertility. Many couples have delayed starting their families until they are in their 30s or 40s, which allows more time to be exposed to situations negatively affecting fertility (including age-related infertility for the woman). In addition, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), which can predispose to decreased fertility, are becoming more common, and many women and men are in workplaces and home settings where they may be exposed to reproductive environmental hazards.

Steps toward prevention of infertility should be undertaken as part of ongoing routine health care, and such information is especially appropriate in preconception counseling. Primary care providers can undertake initial evaluation and counseling before couples are referred to specialists. For additional information about infertility, see Chapter 9.

Menstrual Problems

Irregularities or problems with the menstrual period are among the most common concerns of women and often cause them to seek help from the health care system. Common menstrual disorders include amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome, endometriosis, and menorrhagia or metrorrhagia. Simple explanation and counseling may handle the concern; however, history and examination must be completed, as well as laboratory or diagnostic tests, if indicated. Questions should never be considered inconsequential. Age-specific reading materials are recommended, especially for teenagers. Information should also consider cultural relevance and be available in languages appropriate for the population with whom the nurse is working. See Chapter 6 for an in-depth discussion of menstrual problems.

Perimenopause

The body responds to this natural transition in a number of ways, most of which are due to the decrease in estrogen. Most women seeking health care during the perimenopausal period do so because of irregular bleeding. Others are concerned about vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes and flushes). Although fertility is greatly reduced during this period, women are urged to maintain some method of contraception because pregnancies still can occur. All women need to have factual information, the dispelling of myths, a thorough examination, and periodic health screenings thereafter. See Chapter 6 for discussion of perimenopause and menopause.

Barriers to Seeking Health Care

Parts of the health care delivery system remain in a state of flux. Great variation occurs depending on type and size of the system, source of payment for services, private versus public programs, availability of and accessibility to providers, individual preferences, and insurance coverage or ability to pay. The existing system continues to be oriented to treatment of acute or episodic conditions rather than the promotion of health and comprehensive care (see discussion in Chapter 1).

A health care reform bill was signed by President Obama on March 23, 2010. However, the impact of this legislation on the American people will not be known for years because not all benefits will be immediate (Gaulin, 2010).

Cultural Issues

As our nation becomes more racially, ethnically and culturally diverse, the health of minority groups becomes a major issue. A variety of reasons are given to explain some of the differences in accessing care when financial barriers are adjusted. Unfair treatment was described by women who experienced racial discrimination or disrespectful, disillusioning, or discouraging encounters with community service providers such as social services and health care providers. A lack of training in cross-cultural communication may present problems. Desired health outcomes are best achieved when the health care providers have a knowledge and understanding about the culture, language, values, priorities, and health beliefs of minority groups. Conversely, members of the group should understand the health goals to be achieved and the methods proposed to do so. Language differences can produce profound barriers between women and health care providers. Even with an interpreter, information may be skewed in either direction.

Providers must consider culturally based differences that could affect the treatment of diverse groups of women, and the women themselves should share their practices and beliefs that could influence their management, responses, or willingness to comply (see Cultural Considerations box: Female Genital Mutilation). For example, women in some cultures value privacy to such an extent that they are reluctant to disrobe and, as a result, avoid physical examination unless absolutely necessary. Other women rely on their husbands to make major decisions, including those affecting the woman’s health. Religious beliefs may dictate a specified plan of care, such as limiting assisted reproductive technology, contraception measures, blood transfusions, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or assisted ventilation. Some cultural groups prefer folk medicine, homeopathy, or prayer to traditional Western medicine, and others attempt combinations of various practices

Gender Issues

Gender influences provider-client communication and may influence access to health care in general. The most obvious gender consideration is that between men and women. Researchers have reported significant male-female differences in receipt of major diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, especially with cardiac and kidney problems. Women tend to use primary care services more often than men and, some believe, more effectively. The sex of the provider plays a role; studies have shown that female clients have Pap tests and mammograms more consistently if they are seen by female providers.

Sexual orientation may produce another barrier. Lesbian women have primary erotic attractions and relations with other women. Some lesbians may not disclose their orientation to

health care providers because they feel they may be at risk for hostility, inadequate health care, or breach of confidentiality. In many health care settings, heterosexuality is assumed, and the setting may be one in which the woman does not feel welcome (magazines, brochures, and environment reflect heterosexual couples, or the health care provider shows discomfort interacting with the woman). Another problem is that lesbians themselves may hold beliefs that are incorrect, such as that they have immunity to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), STIs, and certain cancers (e.g., cervical). The perceived lack of risk can result in lesbians avoiding medical care as well as in health care providers giving incorrect advice or not doing appropriate cancer screening for these women. Not all gynecologic cancers are related to sexual activity; lesbians who have never had children may be more at risk for breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancer. Their risk for heart disease, cancer of the lung, and colon cancer is the same as that of the heterosexual woman. To offset stereotypes, it is necessary for providers to develop an approach that does not assume that all women are heterosexual. Revising forms to be inclusive of sexual diversity and providing an environment that promotes acceptance and inclusiveness are two strategies suggested by researchers (Goldberg, 2005-2006; Roberts, 2006).

Health Risks in the Childbearing Years

Maintaining optimal health is a goal for all women. Essential components of health maintenance are identification of unrecognized problems and potential risks and the education and the health promotion needed to reduce them. This is especially important for women in their childbearing years, because conditions that increase a woman’s health risks are not only of concern for her well-being but also are potentially associated with negative outcomes for both mother and baby in the event of a pregnancy. Prenatal care is an example of prevention that is practiced after conception; however, prevention and health maintenance are needed before pregnancy because many of the mother’s risks can be identified and then eliminated or at least modified. An overview of conditions and circumstances that increase health risks in the childbearing years follows.

Age

As a girl progresses through development, she may be at risk for conditions that are age related. All teens undergo progressive growth of sexual characteristics and undertake developmental tasks of adolescence, such as establishing identity, developing sexual preference, emancipating from family, and establishing career goals. Some of these situations can produce great stress for the adolescent, and the health care provider should treat her carefully. Female teenagers who enter the health care system usually do so for screening (Pap tests start at age 21 or 3 years after the girl becomes sexually active) or because of a problem such as episodic illness or accidents. Gynecologic problems are often associated with menses (either bleeding irregularities or dysmenorrhea), vaginitis or leukorrhea, STIs, contraception, or pregnancy. The adolescent also is at risk for depression (Huff, Abuzz, & Omar, 2007).

Teenage Pregnancy: Pregnancy in the teenager who is 16 years old or younger often introduces additional stress into an already stressful developmental period. The emotional level of such teens is commonly characterized by impulsiveness and self-centered behavior, and they often place primary importance on the beliefs and actions of their peers. In attempts to establish a personal and independent identity, many teens do not realize the consequences of their behavior, and planning for the future is not part of their thinking processes.

Teenagers usually lack the financial resources to support a pregnancy and may not have the maturity to avoid teratogens or to have prenatal care and instruction or follow-up care. Children of teen mothers can be at risk for abuse or neglect because of the teen’s inadequate knowledge of growth, development, and parenting. Implementation of specialized adolescent programs in schools, communities, and health care systems is demonstrating continued success in reducing the birth rate in teens.

Young and Middle Adulthood

Because women ages 20 to 40 years have need for contraception, pelvic and breast screening, and pregnancy care, they can prefer to use their gynecologic or obstetric provider as their primary care provider also. During these years the woman may be “juggling” family, home, and career responsibilities, with resulting increases in stress-related conditions. Health maintenance includes not only pelvic and breast screening but also promotion of a healthy lifestyle, that is, good nutrition, regular exercise, no smoking, little or no alcohol consumption, sufficient rest, stress reduction, and referral for medical conditions and other specific problems. Common conditions requiring well-woman care include vaginitis, urinary tract infections, menstrual variations, obesity, sexual and relationship issues, and pregnancy.

Parenthood After Age 35: A woman older than 35 years does not have a different physical response to a pregnancy, per se, but rather has had health status changes as a result of time and the aging process. These changes may be responsible for age-related pregnancy conditions. For example, a woman with type 2 diabetes may not have had expression of her diabetes at age 22, but may have full-blown disease at age 38. Other chronic or debilitating diseases or conditions increase in severity with time, and these in turn may predispose to increased risks during pregnancy (National Women’s Health Resource Center [NWHRC], 2008). Of significance to women in this age-group is the risk of giving birth to a child with certain genetic anomalies (e.g., Down syndrome), and the opportunity for genetic counseling should be available to all (March of Dimes, 2010).

Late Reproductive Age

Women of later reproductive age are often experiencing change and reordering of their personal priorities. Generally the goals of education, career, marriage, and family have been achieved, and now the woman has increased time and opportunity for new interests and activities. Conversely, divorce rates are high at this age, and children leaving home may produce an “empty nest syndrome,” resulting in increased levels of depression. Chronic diseases also become more apparent. Most problems for the well woman are associated with perimenopause (e.g., bleeding irregularities and vasomotor symptoms). Health maintenance screening continues to be of importance because some conditions such as breast disease or ovarian cancer occur more often during this stage.

Socioeconomic Status

Differences exist among people from different socioeconomic levels and ethnic groups with respect to risk for illness and distribution of disease and death. Some diseases are more common among people of selected ethnicity, for example, sickle cell anemia in African-Americans, Tay-Sachs disease in Ashkenazi Jews, adult lactase deficiency in Chinese, beta thalassemia in Mediterranean peoples, and cystic fibrosis in northern Europeans. Cultural and religious influences also increase health risks because the woman and her family may have life and societal values and a view of health and illness that dictate practices different from those expected in the Judeo-Christian Western model. These practices may include food taboos or frequencies, methods of hygiene, effects of climate, care-seeking behaviors, willingness to undergo screening and diagnostic procedures, and value conflicts.

Socioeconomic status affects birth outcomes. Social consequences for poor women as single parents are great because many mothers with few skills are caught in the bind of having income that is insufficient to afford child care. These families generate fewer and fewer resources and increase their risks for health problems. Multiple roles for women in general produce overload, conflict, and stress, resulting in higher risks for psychologic illness.

Substance Use and Abuse

Use of illicit drugs and inappropriate use of prescription drugs continue to increase and are found in all ages, races, ethnic groups, and socioeconomic strata. Addiction to substances is seen as a biopsychosocial disease, with several factors contributing to risk. These include biogenetic predisposition, lack of resilience to stressful life experiences, and poor social support. Women are less likely than men to abuse drugs, but the rate in women is increasing significantly. Substance-abusing pregnant women create severe problems for themselves and their offspring, including interference with optimal growth and development and addiction. In many instances, the use of substances is identified through screening programs in prenatal clinics and obstetric units (see Chapter 32).

Smoking

Cigarette smoking is a major preventable cause of death and illness. Smoking is linked to cardiovascular heart disease, various types of cancers (especially lung and cervical), chronic lung disease, and negative pregnancy outcomes. Tobacco contains nicotine, which is an addictive substance that creates a physical and a psychologic dependence. There is little difference in the rate of smoking between men and women, although rates for women are slightly less (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2010a). Cigarette smoking impairs fertility in women and men, may reduce the age for menopause, and increases the risk for osteoporosis after menopause. Smoking during pregnancy is known to cause a decrease in placental perfusion and is a cause of low birth weight (Kliegman, 2006).

Alcohol

Women ages 35 to 49 years have the highest rates of chronic alcoholism, but women ages 21 to 34 have the highest rates of specific alcohol-related problems. About one third of alcoholics are women, and many relate onset of their drinking problem to stressful events. Women who are problem drinkers are often depressed, have more motor vehicle injuries, and have a higher incidence of attempted suicide than women in the general population. They also are at risk for alcohol-related liver damage. Early case finding and treatment are important in alcoholism for both the ill individual and for family members. See Chapter 32 for further discussion about alcohol use in women.

Prescription Drugs

Psychotherapeutic medications such as stimulants, sleeping pills, tranquilizers, and pain relievers are used by an estimated 2% of American women. Such medications can bring relief from undesirable conditions such as insomnia, anxiety, and pain, but because the medications have mind-altering capacity, misuse can produce psychologic and physical dependency in the same manner as illicit drugs. Risk-to-benefit ratios should be considered when such medications are used for more than short periods.

Depression is the most common mental health problem in women. Many kinds of medications are used to treat depression. All of these psychotherapeutic drugs can have some effect on the fetus when taken during pregnancy and must be very carefully monitored (see Chapter 32).

Illicit Drugs

Illicit drugs are taken for unlawful purposes. When they are unprescribed, they are usually obtained on the street for the purpose of getting high or for their body-mind–altering characteristics. Almost any drug can be abused or even illegal if taken in excess, including alcohol and prescription medication (see Chapter 32 for further discussion of substance abuse).

Nutrition

Good nutrition is essential for optimal health. A well-balanced diet helps prevent illness and treat certain health problems. Conversely, poor eating habits, eating disorders, and obesity are linked to disease and debility.

Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010 provides evidenced-based recommendations to promote health and reduce risks for chronic diseases through diet (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] & U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA], 2010) (www.cnpp.usda.gov/Dietaryguidelines/htm).

Nutritional Deficiencies

Overt disease caused by lack of certain nutrients is rarely seen in the United States; however, insufficient amounts or imbalances of nutrients do pose problems for individuals and families. Overweight or underweight status, malabsorption, listlessness, fatigue, frequent colds and other minor infections, constipation, dull hair and thin nails, and dental caries are examples of problems that can be related to nutrition and indicate the need for further nutritional assessment. Poor nutrition, especially related to obesity and high fat and cholesterol intake, may lead to more serious conditions and is said to contribute to four of the six leading causes of death in the United States: heart disease, malignant neoplasms, cerebrovascular disease, and diabetes (Kung, Hoyert, Xu, & Murphy, 2008).

Obesity

During the last 20 years, obesity in the United States has increased dramatically. Estimates indicate that one third of women older than 20 years are obese (body mass index [BMI] 30 or higher) (NWHRC, 2006). In the United States the prevalence of obesity is highest among non-Hispanic black women, followed by Hispanic women and non-Hispanic white women (CDC, 2009). The BMI is defined as a measure of an adult’s weight in relation to his or her height, specifically the adult’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of his or her height in meters (see Table 14-2).

Overweight and obesity are known risk factors for premature death, diabetes, heart disease, dyslipidemia, stroke, hypertension, gallbladder disease, diverticular disease, some anemias, oral disease, constipation, osteoarthritis, gout, osteoporosis, respiratory dysfunction and sleep apnea, and some types of cancer (uterine, breast, colorectal, kidney, and gallbladder) (ACS, 2010b). In addition, obesity is associated with high cholesterol, menstrual irregularities, hirsutism (excess body/facial hair), stress incontinence, depression, complications of pregnancy, increased surgical risk, and shortened life span (USDHHS & USDA, 2010). Obesity-related pregnancy complications include macrosomia, gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders, preterm birth, and cesarean birth. Pregnant women who are morbidly obese are at increased risk for intrauterine growth restriction and intrauterine fetal demise (Smith, Hulsey, & Goodnight, 2008).

Other Considerations

Other dietary extremes also can produce risk. For example, insufficient amounts of calcium can lead to osteoporosis, too much sodium can aggravate hypertension, and megadoses of vitamins can cause adverse effects in several body systems. Fad weight-loss programs and yo-yo dieting (repeated weight gain and weight loss) result in nutritional imbalances and, in some instances, medical problems. Such diets and programs are not appropriate for weight maintenance. Adolescent pregnancy produces special nutritional requirements because the metabolic needs of pregnancy are superimposed on the teen’s own needs for growth and maturation at a time when eating habits are less than ideal.

Anorexia Nervosa: Some women have a distorted view of their bodies and, no matter what their weight, perceive themselves to be much too heavy. As a result, they undertake strict and severe diets and rigorous extreme exercise. This chronic eating disorder is known as anorexia nervosa. Women can carry this condition to the point of starvation, with resulting endocrine and metabolic abnormalities. If not corrected, significant complications of arrhythmias, amenorrhea, cardiomyopathy, and congestive heart failure occur and, in the extreme, can lead to death. The condition commonly begins during adolescence in young women who have some degree of personality disorder. They gradually lose weight over several months, have amenorrhea, and are abnormally concerned with body image. Diagnosis can be difficult, especially if the person tries to hide the problem. Denial of a problem and secrecy around eating are common features of anorexia. Depression usually accompanies anorexia. There are no specific tests to diagnose anorexia nervosa. A medical history, physical examination, and screening tests help identify women at risk for eating disorders. Several tools are available to use in primary care settings. The SCOFF questionnaire is easy to administer and can help the nurse decide whether an eating disorder is likely and if the woman needs further assessment and possibly psychiatric and medical intervention (Parker, Lyons, & Bonner, 2005; Wolfe, 2005) (Box 4-4).

Bulimia Nervosa: Bulimia refers to secret, uncontrolled binge eating alternating with methods to prevent weight gain: self-induced vomiting, use of laxatives or diuretics, strict diets, fasting, and rigorous exercise. During a binge episode, large numbers of calories are consumed, usually consisting of sweets and “junk foods.” Binges occur at least twice per week. Bulimia usually begins in early adulthood (ages 18 to 25 years) and is found primarily in women. Complications can include dehydration and electrolyte imbalance, gastrointestinal abnormalities, and cardiac arrhythmias (Wolfe, 2005). Bulimia is somewhat similar to anorexia in that it is an eating disorder and usually involves some degree of depression. Unlike those with anorexia, individuals with bulimia may feel shame or disgust about their disorder and tend to seek help earlier. The SCOFF assessment also can be used to screen for bulimia (see Box 4-4).

Binge Eating Disorder: The hallmark of binge eating disorder is eating large amounts of food in a short period (a couple of hours) and not being able to stop eating. The woman may eat when she’s not hungry or until uncomfortably full. She may choose to eat alone because she is embarrassed about how much she eats. Binge eating disorder involves bingeing that alternates with a restricted dietary intake. An associated syndrome called night eating syndrome is when limited food is eaten early in the day and most of the day’s food intake is consumed after the evening meal. Over time, obesity and related complications of being overweight can develop. Common personality traits found in those with binge eating disorder include excessive concern about body size and shape and low self-esteem. Depression and anxiety commonly occur along with binge eating, which makes treatment and recovery more difficult. Binge eating is not associated with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa.

Physical Fitness and Exercise

Physical activity promotes health, psychological well-being, and ideal body weight for height. It enhances independence, and improves quality of living across the life span. Women should engage in 2½ hours per week of moderate intensity or 1¼ hours per week of vigorous intensity aerobic physical activity or a combination of both according to the current Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (USDHHS, 2008).

Exercise can reduce risks for a variety of conditions that are influenced by obesity and a sedentary lifestyle such as cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, and diabetes. Exercise plays an important role in the management of chronic conditions such as hypertension, arthritis, respiratory disorders, and osteoporosis. Exercise contributes to stress reduction and improving the quality of sleep. Women report that engaging in regular exercise improves their body image and self-esteem and acts as a mood enhancer.

Aerobic exercise contributes to cardiovascular fitness while increasing oxygen levels to working muscles. Anaerobic exercise, such as weight training, improves individual muscle mass without stress on the cardiovascular system. Because women are concerned about both cardiovascular and bone health, weight-bearing aerobic exercises such as walking, running, racket sports, and dancing may be preferred. Sustained excessive exercise can lead to hormonal imbalances, such as amenorrhea, which can usually be reversed when the body returns to normal levels of activity.

Stress

The modern woman faces increasing levels of stress and as a result is prone to a variety of stress-induced complaints and illnesses. Stress often occurs because of multiple roles, such as when coping with job and financial responsibilities conflicts with parenting and duties at home. To add to this burden, women are socialized to be caretakers, which is an emotionally draining role in itself. They also may find themselves in positions of minimal power that do not allow them to have control over their everyday environments. Some stress is normal and contributes to positive outcomes. Many women thrive in busy surroundings. However, excessive or high levels of ongoing stress trigger physical reactions in the body, such as rapid heart rate, elevated blood pressure, slowed digestion, release of additional neurotransmitters and hormones, muscle tenseness, and a weakened immune system. Consequently, constant stress can contribute to clinical illnesses such as flare-ups of arthritis or asthma, frequent colds or infections, gastrointestinal upsets, cardiovascular problems, and infertility. Box 4-5 lists symptoms that may be related to chronic or extreme stress. Psychologic signs such as anxiety, irritability, eating disorders, depression, insomnia, and substance abuse are associated with stress.

Sexual Practices

Potential risks related to sexual activity are undesired pregnancy and STIs. The risks are particularly high for adolescents and young adults who engage in sexual intercourse at earlier and earlier ages. Adolescents report many reasons for wanting to be sexually active, among which are peer pressure, desire to love and be loved, experimentation, enhancing self-esteem, and having fun. However, many teens do not have the decision-making or values-clarification skills needed to take this important step at a young age, and they lack the knowledge base regarding contraception and STIs. They also do not believe that becoming pregnant or getting an STI will happen to them.

Although some STIs can be cured with antibiotics, many can cause significant problems. Possible sequelae include infertility, ectopic pregnancy, neonatal morbidity and mortality, genital cancers, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and even death (CDC, Workowski, & Berman, 2006). The incidence of STIs is increasing rapidly and reaching epidemic proportions. Choice of contraception has an effect on the risk of contracting an STI; however, no method of contraception offers complete protection. (See Chapter 7 for discussion of STIs and Chapter 8 for contraception.)

Medical Conditions

Most women of reproductive age are relatively healthy. Heart disease; lung, breast, colon, and gynecologic cancers; stroke; chronic lung disease; and diabetes are among the leading causes of death in adult women (Heron & Tejada-Vera, 2008) (Box 4-6). Certain medical conditions present during pregnancy can have deleterious effects on both the woman and the fetus. Of particular concern are risks from all forms of diabetes, urinary tract disorders, thyroid disease, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, cardiac disease, and seizure disorders. Effects on the fetus vary and include intrauterine growth restriction, macrosomia, anemia, prematurity, immaturity, and stillbirth. Effects on the woman also can be severe. These conditions are discussed in later chapters.

Gynecologic Conditions

Women are at risk throughout their reproductive years for pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, STIs and other vaginal infections, uterine fibroids, uterine deformities such as bicornuate uterus, ovarian cysts, interstitial cystitis, and urinary incontinence related to pelvic relaxation. These gynecologic conditions may contribute negatively to pregnancy by causing infertility, miscarriage, preterm labor, and fetal and neonatal problems. Gynecologic cancers also affect women’s health, although the risk for most cancers is low in pregnancy. Risk factors depend on the type of cancer. The effect of developing a gynecologic problem or cancer in women and their families is shaped by a number of factors including the specific type of problem or cancer, the implications of the diagnosis for the woman and her family, and the timing of the occurrence in the woman’s and family’s lives. These conditions are discussed in Chapters 6, 7, and 11.

Environmental and Workplace Hazards

Environmental hazards in the home, the workplace, and the community can contribute to poor health at all ages. Categories and examples of health-damaging hazards include the following: (1) pathogenic agents (viruses, bacteria, fungi, parasites); (2) natural and synthetic chemicals (natural toxins from animals, insects, and plants; consumer and industrial products such as pesticides and hydrocarbon gases; medical and diagnostic devices; tobacco; fuels; and drug and alcohol abuse); (3) radiation (radon, heat waves, sound waves); (4) food substances (added components that are not necessary for nutrition); and (5) physical objects (moving vehicles, machinery, weapons, water, and building materials).

Environmental hazards can affect fertility, fetal development, live birth, and the child’s future mental and physical development. Environmental hazards are discussed throughout other chapters as they are identified as specific risks to women’s and infants’ health.

Violence Against Women

Violence against women is a major health care problem in the United States, affecting millions of women each year and costing millions of dollars in annual medical costs. Women of all races and of all ethnic, educational, religious, and socioeconomic backgrounds are affected. Pregnancy is often a time when violence begins or escalates. The magnitude of the problem is far greater than the statistics indicate because violent crimes against women are the most underreported data as a result of fear, lack of understanding, and stigma surrounding violent situations. Maternity and women’s health nurses, by the very nature of their practice, are in a unique position to conduct case finding, provide sensitive care to women experiencing abusive situations, engage in prevention activities, and influence health care and public policy toward decreasing the violence. For further discussion of violence against women, see Chapter 5.

Health Assessment

Women’s health trends have expanded beyond a reproductive focus to include a holistic approach to health care across the life span and places women’s health within the scope of primary care. Women’s health assessment and screening focus on a systems evaluation beginning with a careful history and physical examination. During the assessment and evaluation, the responsibility for self-care, health promotion, and wellness enhancement is emphasized.

In a market-driven system such as managed care, specific guidelines may be provided for health screening by the insurer or the managed care organization. A nurse often takes the history, orders diagnostic tests, interprets test results, makes referrals, coordinates care, and directs attention to problems requiring medical intervention. Advanced practice nurses who have specialized in women’s health, such as nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, and nurse-midwives, perform complete physical examinations, including gynecologic examinations.

Interview

The contact with the woman usually begins with an interview. This interview should be conducted in a private, comfortable, and relaxed setting (Fig. 4-8). The woman is addressed by her title and name (e.g., Mrs. Gonzalez), and the nurse introduces herself or himself by using name and title. It is important to phrase questions in a sensitive and nonjudgmental manner. Body language should match verbal communication. The nurse is cognizant of a woman’s vulnerability and assures her of strict confidentiality. For many women, fear, anxiety, and modesty make the examination a dreaded and stressful experience. Many women are uninformed, misguided by myths, or afraid they will appear ignorant by asking questions about sexual or reproductive functioning. The woman is assured that no question is irrelevant. The history begins with an open-ended question such as, “What brings you in to the office/clinic/hospital today? Anything else? Tell me about it.”

FIG. 4-8 Nurse interviews woman as part of history taking prior to physical examination. (Courtesy Ed Lowdermilk, Chapel Hill, NC.)

Additional ways to get women to share information include the following:

• Facilitation: Using a word or posture that communicates interest; leaning forward; making eye contact; or saying “Mm-hmmm” or “Go on”

• Reflection: Repeating a word or phrase that a woman has used

• Clarification: Asking the woman what is meant by a word or phrase

• Empathic responses: Acknowledging the feelings of a woman by statements such as “That must have been frightening”

• Confrontation: Identifying something about the woman’s behavior or feelings not expressed verbally or apparently inconsistent with her history

• Interpretation: Putting into words what you infer about the woman’s feelings or about the meaning of her symptoms, events, or other matters

Direct questions may be necessary to elicit specific details. These should be worded in language that is understandable to the woman and expressed neutrally, so that the woman will not be led into a specific response. The nurse asks about one item at a time and proceeds from the general to the specific (Seidel, Ball, Dains, Flynn, Soloman, & Stewart, 2011).

Cultural Considerations

Recognizing signs and symptoms of disease and deciding when to seek treatment are influenced by cultural perceptions. It is essential that a nurse have respect for the rich and unique qualities that cultural diversity brings to individuals. In recognizing the value of these differences, the nurse can modify the plan of care to meet the needs of each woman.

To understand the woman’s point of view, it is important to ask the right questions. Galanti (2008) suggests the use of the 4 C’s of Cultural Competence. These include:

1. Call—What do you call your problem?

2. Cause—What do you think caused your problem?

3. Cope—How do you cope with your condition?

4. Concerns—What are your concerns regarding your condition?

Using the 4 C’s of Cultural Competence along with cultural proficiency, biomedical values and evidence-based practice allows the nurse to individualize care with a client-focused approach. Trust that the woman is the expert on her life, culture, and experiences. If the nurse asks with respect and a genuine desire to learn, the woman will tell the nurse how to care for her. Modifications may be necessary for the physical examination. In some cultures, it may be considered inappropriate for the woman to disrobe completely for the physical examination. In many cultures, a female examiner is preferred. Communication may be hindered by different beliefs even when the nurse and woman speak the same language (see Box 2-1, p. 25, and Cultural Considerations box above).

Women with Special Needs

Women with emotional or physical disorders have special needs. Women who have vision, hearing, emotional, or physical disabilities should be respected and involved in the assessment and physical examination to the full extent of their abilities. The nurse should communicate openly and directly with sensitivity. It is often helpful to learn about the disability directly from the woman while maintaining eye contact (if eye contact is culturally appropriate). Family and significant others should be relied on only when absolutely necessary. The assessment and physical examination can be adapted to each woman’s individual needs.

Communication with a woman who is hearing impaired can be accomplished without difficulty. Most of these women read lips, write, or both; thus an interviewer who speaks and enunciates each word slowly and in full view may be easily understood. If a woman is not comfortable with lip reading, she may use an interpreter. In this case, it is important to continue to address the woman directly, avoiding the temptation to speak directly with the interpreter.

The visually impaired woman needs to be oriented to the examination room and may have her guide dog with her. As with all women, the visually impaired woman needs a full explanation of what the examination entails before proceeding. Before touching her, the nurse explains, “Now I am going to take your blood pressure. I am going to place the cuff on your right arm.” The woman can be asked if she would like to touch each of the items that will be used in the examination.

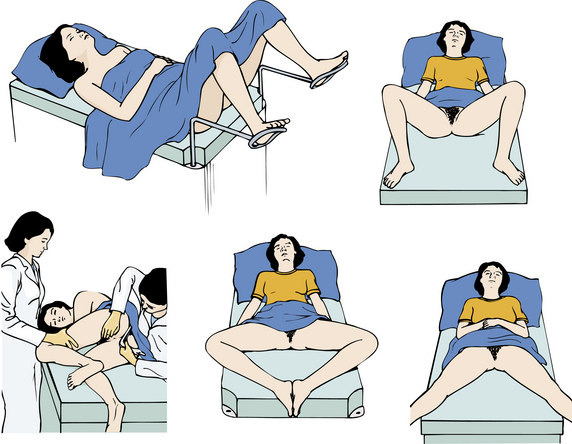

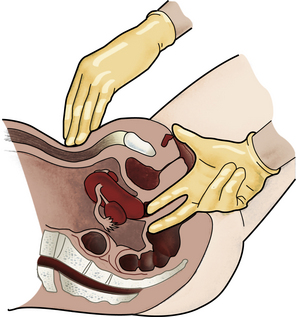

Many women with physical disabilities cannot comfortably lie in the lithotomy position for the pelvic examination. Several alternative positions may be used, including a lateral (side-lying) position, a V-shaped position, a diamond-shaped position, and an M-shaped position (Piotrowski & Snell, 2007) (Fig. 4-9). The woman can be asked what has worked best for her previously. If she has never had a pelvic examination, or has never had a comfortable pelvic examination, the nurse proceeds by showing her a picture of various positions and asking her which one she prefers. The nurse’s support and reassurance can help the woman to relax, which will make the examination go more smoothly.

Abused Women

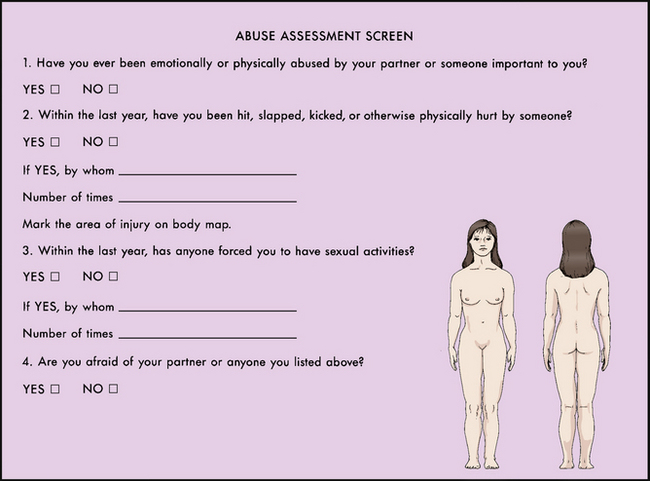

Nurses should screen all women entering the health care system for potential abuse. Help for the woman may depend on the sensitivity with which the nurse screens for abuse, the discovery of abuse, and subsequent intervention. The nurse must be familiar with the laws governing abuse in the state in which she or he practices.

Pocket cards listing emergency numbers (abuse counseling, legal protection, and emergency shelter) may be available from the local police department, a women’s shelter, or an emergency department. It is helpful to have these on hand in the setting where screening is done. An abuse-assessment screen (Fig. 4-10) can be used as part of the interview or written history. If a male partner is present, he should be asked to leave the room because the woman may not disclose experiences of abuse in his presence, or he may try to answer questions for her to protect himself. The same procedure would apply for partners of lesbians, parents of teens, or adult children of older women.

FIG. 4-10 Abuse assessment screen. (Modified from the Nursing Research Consortium on Violence and Abuse. [1991].)