Problems of the Breast

• Discuss the pathophysiology of selected benign and malignant breast disorders found in women.

• Explain the emotional effects of benign and malignant neoplasms.

• Design a nursing care plan for the woman with a breast disorder.

• Evaluate treatment alternatives for women with breast cancer.

• Integrate critical elements for teaching women who have undergone medical-surgical management of benign or malignant neoplasms of the breast.

Approximately 50% of women have a breast problem at some point in their adult lives. The most common sign of a breast problem is a palpable mass. Most of these lumps are benign, although finding them may produce anxiety for the woman, who may fear she has cancer. The development of breast cancer can have a far-reaching effect on the woman and her family. Beyond the obvious physiologic alterations, she also may experience threats to her self-image and ability to cope. The condition and its treatments can affect a woman’s concept of herself as a sexual being. Cancer also presents a challenge for a woman’s family. When breast cancer occurs during or after pregnancy, it adds to the complexity of both physical and emotional responses to childbearing.

Nurses have important roles in teaching women about early detection and treatment and in providing supportive care to clients and their families. This chapter presents information that will assist nurses in providing care for women with benign breast conditions or breast cancer. The ongoing investigations of new drug therapies to prevent breast cancer are also introduced.

Benign Conditions of the Breast

A benign breast condition often causes a lump or thickened area noted on breast self-examination (BSE) or clinical breast examination. It may or may not feel tender. The most common causes of a single lump are fibroadenoma, fibrocystic changes, cysts, or atypical hyperplasia. The younger a woman is the more likely a single lump will be found to be benign.

Fibrocystic Changes

The most common benign breast problem is fibrocystic change found in varying degrees in healthy women’s breasts. Fibrocystic changes are characterized by lumpiness, with or without tenderness, in both breasts (Valea & Katz, 2007). Fibrocystic breast condition involves the glandular breast tissue.

Etiology

Fibrocystic changes tend to appear most commonly in women in their second and third decades of life. The most significant contributing factor to fibrocystic breast condition is a woman’s normal hormonal variation during her monthly cycle. Many hormonal changes occur as a woman’s body prepares each month for a possible pregnancy. The most important of these hormones are estrogen and progesterone. These two hormones directly affect the breast tissues by causing cells to proliferate. Other hormones also play an important role, however, causing fibrocystic changes. Prolactin, growth factor, insulin, and thyroid hormones are some of the other major hormones that can also affect cell growth within the breast tissue. Except for proliferative change known as hyperplasia, which is associated with a slightly elevated risk of breast cancer, or atypical hyperplasia, which is associated with a moderately increased risk of breast cancer, the histologic findings associated with fibrocystic changes are part of the spectrum of normal involutional patterns of the breast (Valea & Katz).

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

The usual clinical presentation of fibrocystic change is lumpiness in both breasts; however, single simple cysts also can occur. Women in their 20s report the most severe pain. Women in their 30s have premenstrual pain and tenderness; small multiple nodules are usually present. Women in their 40s usually do not report severe pain, but cysts will be tender and often regress in size. Symptoms usually develop about a week before menstruation begins and subside about a week after menstruation ends. They include dull, heavy pain and a sense of fullness and tenderness often in the upper outer quadrant of the breasts that increases in the premenstrual period. The woman with fibrocystic change may form cysts that manifest as painful enlarging lumps in her breasts. Cysts are common in premenopausal women who are not receiving estrogen therapy. Physical examination may reveal excessive nodularity. The cysts are soft on palpation, well differentiated, and movable. Deeper cysts, especially aggregations of cysts, are indistinguishable by palpation from carcinomas, which are malignant growths that infiltrate surrounding tissue.

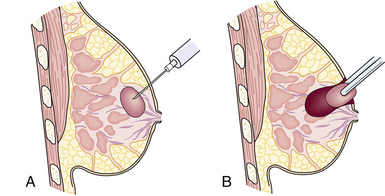

A first assessment of a breast lump is ultrasonography to determine if it is fluid filled or solid. Fluid-filled cysts are aspirated, and the woman is monitored on a routine basis for development of other cysts. If the lump is solid and the woman is older than 35 years, mammography is obtained. A fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is performed, regardless of the woman’s age, to determine the nature of the lump (see Fig 10-4). In some cases, a core biopsy may be necessary after FNA to harvest adequate amounts of tissue for pathologic examination (Lin, Hsu, Yu, Yu, Lee, Hsu, et al., 2009; Valea & Katz, 2007).

Therapeutic Management

Treatment for fibrocystic changes is usually conservative. Management can depend on the severity of the symptoms. Dietary changes and vitamin supplements are one management approach. Although research findings are contradictory, some practitioners advocate reducing consumption or eliminating methylxanthines (i.e., colas, coffee, tea, chocolate) and tobacco (Valea & Katz, 2007). Some symptom relief may be achieved by avoiding smoking and the consumption of alcohol. Recommended pain-relief measures include taking analgesics or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, wearing a supportive bra, and applying heat to the breasts.

Vitamin E supplements and decreasing sodium intake or taking mild diuretics before menses have also been reported to reduce some women’s symptoms. Some women report relief while taking oral contraceptives, but others report worsening of symptoms. Danazol, bromocriptine, and tamoxifen also have been used with varying degrees of success (Valea & Katz, 2007). Evening primrose oil may be effective for some women, although evidence is lacking.![]() It is important to stress that women may need to try several approaches for a number of months before improvement is noted (Valea & Katz).

It is important to stress that women may need to try several approaches for a number of months before improvement is noted (Valea & Katz).

Surgical removal of nodules is attempted only in rare cases. In the presence of multiple nodules, the surgical approach involves multiple incisions and tissue manipulation and may not prevent the development of more nodules.

Fibroadenomas

The next most common benign condition of the breast is a fibroadenoma. It is the single most common type of tumor seen in the adolescent population, although it can also occur in women in their 20s and 30s. Fibroadenomas are discrete, usually solitary lumps less than 3 cm in diameter (Valea & Katz, 2007). Occasionally the woman with a fibroadenoma will experience tenderness in the tumor during the menstrual cycle. Fibroadenomas do not increase in size in response to the menstrual cycle (in contrast to fibrocystic cysts). The mass tends to remain the same size or increase in size slowly over time. Fibroadenomas increase in size during pregnancy and decrease in size as the woman ages. Diagnosis is made by a review of the client history and physical examination. Mammography, ultrasonography, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to determine the type of lesion, and FNA may be used to determine the underlying disorder. Surgical excision may be necessary if the lump is suspicious or if the symptoms are severe. Fibroadenomas do not respond to either dietary changes or hormonal therapy. Periodic observation of masses by professional physical examination or mammography may be all that is necessary for those masses not requiring surgical intervention (Shockney & Tsangaris, 2007).

Nipple Discharge

Nipple discharge is a common occurrence that concerns many women. Though most nipple discharge is physiologic, each woman who presents with this problem must be evaluated carefully because in a small percentage, nipple discharge may be related to a serious endocrine disorder or malignancy. Bilateral serous discharge expressed during nipple stimulation can be considered a normal finding (Shockney & Tsangaris, 2007).

Another form of nipple discharge not related to malignancy is galactorrhea—a bilaterally spontaneous, milky, sticky discharge. It is a normal finding in pregnancy. Galactorrhea can also occur as the result of elevated prolactin levels. Increased prolactin levels may be a result of a thyroid disorder, pituitary tumor, coitus, eating, stress, trauma, or chest wall surgery. Obtaining a complete medical history on each woman is essential. Certain medications may precipitate galactorrhea. Tricyclic antidepressants, phenothiazines, narcotics, antiemetics, and antihypertensive medications, as well as oral contraceptives, can precipitate galactorrhea in some women (Lobo, 2007). Diagnostic tests that may be indicated include a prolactin level, a microscopic analysis of the discharge from each breast, a thyroid profile, a pregnancy test, and a mammogram. The optimal time to draw blood to assess a prolactin level is between 8 am and 10 am. Ideally, prolactin levels should not be drawn directly after a breast examination, sexual activity, or exercise session (Lobo, 2007).

Mammary Duct Ectasia

Mammary duct ectasia is an inflammation of the ducts behind the nipple. The cause of mammary duct ectasia is unknown, although chronic inflammation and dilation of the lactiferous ducts has been suggested. This condition occurs most often in perimenopausal women and is characterized by a thick, sticky nipple discharge that is white, brown, green, or purple. Frequently the woman will experience a burning pain, itching, or a palpable mass behind the nipple.

The diagnostic workup consists of a mammogram, aspiration of fluid, and culture of fluid. Duct ectasia is usually self-limiting, requiring only reassurance of the woman. An infection in the inflamed area can occur and requires antibiotic therapy. If an abscess develops, an incision and drainage may be necessary along with a prescription for oral antibiotics. Treatment may also include a local excision of the affected duct or ducts if the woman has no future plans to breastfeed (Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 2008).

Intraductal Papilloma

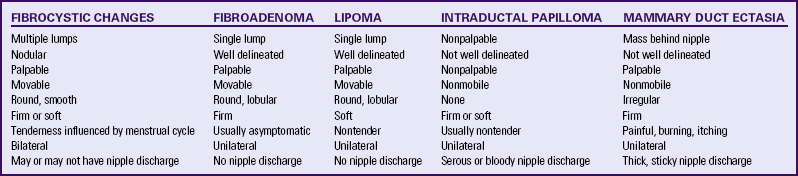

Intraductal papilloma is a relatively rare, benign condition that develops in the terminal nipple ducts. The cause is unknown. It usually occurs in women between ages 30 and 50 years. Papillomas are usually too small to be palpated (less than 0.5 cm), and present with the characteristic sign of serous, serosanguineous, or bloody nipple discharge. The discharge is unilateral and spontaneous. A ductogram is a common way of making the diagnosis, along with mammography and core biopsy. After the possibility of malignancy is eliminated, treatment for papillomas includes excision of the affected segments of the ducts and breasts (Shockney & Tsangaris, 2007; Valea & Katz, 2007). Table 10-1 compares common manifestations of benign breast masses.

Macromastia and Micromastia

Macromastia or breast hyperplasia, is a condition in which the woman has very large breasts. The size and weight of the breasts can cause chronic pain in the breast, back, neck, and shoulders, as well as significant disruption in psychosocial functioning and body image. Macromastia also can cause thoracic kyphosis, headache, paresthesia of the upper extremities, and shoulder grooving from brassiere straps. Macromastia is treated by reduction mammoplasty, in which the plastic surgeon removes breast tissue to reduce the size and weight of the breasts. Women who have had breast reduction surgery have significant improvement of preoperative signs and symptoms and their quality of life (Brown, Holton, Chung, & Slezak, 2008). However, risks associated with the surgery include the potential to affect the woman’s ability to breastfeed in the future, infection, decreased nipple sensation, and scarring (Rahman, Adigunt, Yusif, & Bamigbade, 2007). Breast reduction surgery is considered reconstructive surgery when done to relieve symptoms of macromastia and may be covered by health insurance policies. Women considering reduction mammoplasty should review their policies to determine exact coverage.

Although it is not a breast disorder, micromastia, or having very small breasts, may negatively influence a woman’s body image. Augmentation mammoplasty may be done to increase breast size. The plastic surgeon inserts implants filled with normal saline between the breast tissue and the chest wall. Silicone gel–filled implants are not available for breast augmentation done for cosmetic reasons (Rahman et al., 2007) (see later discussion on breast reconstruction). Breast augmentation surgery is considered cosmetic surgery and is usually not covered by health insurance policies. Saline breast implants do not last indefinitely; most must be replaced in 10 to 15 years or sooner (Shockney & Tsangaris, 2007).

Collaborative Care

Assessment should include a thorough client history and physical examination. The history should focus on risk factors for breast diseases, events related to the breast mass, and health maintenance practices. Risk factors for breast cancer are discussed later in this chapter. Information related to the breast mass should include how, when, and by whom the mass was discovered. The interval between discovery and seeking care is crucial. The following client information is documented: presence of pain, whether symptoms increase with menses, dietary habits, smoking habits, use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy, personal history of breast cancer, family history of breast cancer, use of BSE, and the examination technique if used. The woman’s emotional status, including her stress level, fears, and concerns, and her ability to cope also should be assessed.

Physical examination may include assessment of the breasts for symmetry, masses (size, number, consistency, mobility), and nipple discharge.

Nursing actions might include the following:

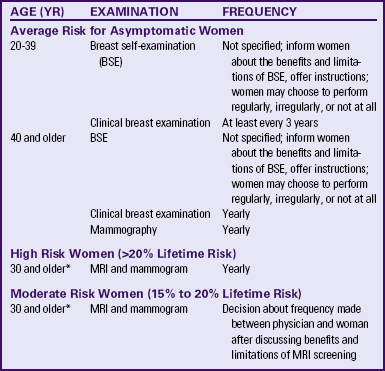

• Discuss the intervals for and facets of breast screening, including professional examination and mammography (see Table 10-3). Women with breast implants may need special views (called push-backs) of the breast, and precautions might have to be taken not to rupture the implant during mammography.

• Provide written educational materials.

• Encourage the verbalization of fears and concerns about treatment and prognosis.

• Provide specific information regarding the woman’s condition and treatment, including dietary changes, drug therapy, comfort measures, stress management, and surgery.

• Demonstrate correct BSE technique if woman desires to practice it (see p. 91).

• Describe pain-relieving strategies in detail, and collaborate with the primary health care provider to ensure effective pain control.

• Encourage discussion of feelings about body image.

• Refer to a stress management resource if needed to cope with long-term consequences of benign breast conditions.

Malignant Conditions of the Breast

The United States has one of the highest rates of breast carcinoma in the world. One in eight American women will develop invasive breast cancer in her lifetime. The American Cancer Society’s (ACS) most recent estimates for breast cancer in the United States are for 2010 (ACS, 2010):

• 207,090 new female cases of invasive breast cancer

• 54,010 new female cases of cancer in situ; about 85% will be ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

Statistics reported by the ACS indicated that breast cancer incidence increased during the 1990s. This increase may be related to better detection of early-stage breast cancer, increasing rates of obesity, improvements in the quality of mammography (digital), and use of postmenopausal hormonal therapy (ACS, 2010). There has been a decrease in incidence from 1999 to 2006, as many women discontinued hormonal therapy for menopausal symptoms.

It is also important to note that in the United States, the number of women over the age of 55 is larger than ever, which will increase the number of women diagnosed. Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women in the United States, other than skin cancer. It is the second leading cause of cancer death in women, after lung cancer. The chance of dying from breast cancer is about 1 in 35—death rates have declined since 1990. This decline is probably the result of finding the cancer earlier and improved treatment (ACS).

Etiologic Factors

Although the exact cause of breast cancer continues to elude investigators, there are certain factors that increase a woman’s risk for developing a malignancy.

Some risk factors are unchangeable; others, associated with lifestyle choices, are changeable. Therefore, being familiar with the entire list is important when a nurse is assessing and counseling a woman about ways to reduce her risk.

Unchangeable risk factors include (ACS, 2009, 2010, Valea & Katz, 2007):

• Gender: Simply being a woman is the main risk for breast cancer. Although men also have the disease, it is about 100 times more common in women than in men.

• Age: The chance of having breast cancer goes up as a woman gets older. About two out of three women with invasive breast cancer are age 55 or older when the cancer is found.

• Genetic risk factors: About 5% to 10% of breast cancers are thought to be linked to inherited changes (mutations) in certain genes. The most common gene changes are those of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Women with these gene changes have up to an 80% chance of having breast cancer during their lifetimes. Other gene changes, such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome, Cowden syndrome, or Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, will raise breast cancer risk as well.

• Family history: Breast cancer risk is higher among women whose close blood relatives have this disease. The relatives can be from either the mother’s or father’s side of the family. Having a mother, sister, or daughter with breast cancer about doubles a woman’s risk. (It’s important to note that 70% to 80% of women who have breast cancer do not have a family history of this disease.) For a family member who carries a breast cancer gene, however, the risk for other family members is higher than for those whose history does not include a genetic link.

• Personal history of breast cancer: A woman with cancer in one breast has a greater chance of having a new cancer in the opposite breast or in another part of the same breast.

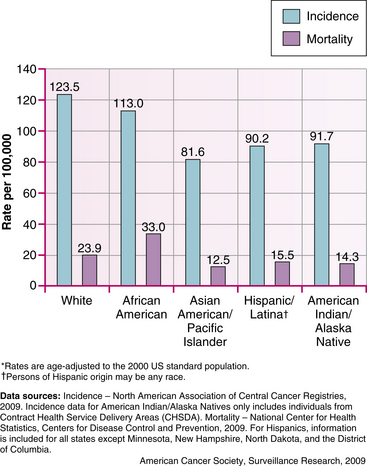

• Race: Caucasian women are slightly more likely to get breast cancer than are African-American women. But African-American women are more likely to die of this cancer. At least part of the reason seems to be because African-American women have faster-growing tumors. Asian, Hispanic, and Native American women have a lower risk of getting breast cancer (Fig. 10-1).

FIG. 10-1 Female breast cancer incidence and mortality rates by race and ethnicity, U.S. 2002-2006 (From American Cancer Society. [2009]. Breast cancer facts and figures, 2009-2010. Atlanta, GA: Author.)

• Dense breast tissue: Women with denser breast tissue have a higher risk of breast cancer. Dense breast tissue can also make it more difficult for a radiologist to see an abnormality on mammograms (Martin, Minkin, & Boyd, 2009).

• Menstrual periods: Women who began having periods early (before age 12) or who went through menopause after the age of 55 have a slightly increased risk of breast cancer. They have had more menstrual periods and as a result have been exposed to more of the hormones estrogen and progesterone.

• Earlier breast radiation: Women who have had radiation treatment to the chest area (as treatment for another cancer) earlier in life have a greatly increased risk of breast cancer.

• Treatment with diethylstilbestrol (DES): In the past, some pregnant women were given DES because it was thought to lower their chances of losing the baby (miscarriage). Studies have shown that these women (and their daughters who were exposed to DES while in the womb), have a slightly increased risk of having breast cancer.

Lifestyle choices increase the risk of breast cancer. These include: (ACS, 2009, 2010)

• Not having children or having them later in life: Women who have not had children, or who have their first child after age 30, have a slightly higher risk of breast cancer. Being pregnant more than once and at an early age reduces breast cancer risk. Pregnancy reduces a woman’s total number of lifetime menstrual cycles, which may be the reason for this effect.

• Recent use of birth control pills: Studies have found that women who are using birth control pills have a slightly greater risk of breast cancer than women who have never used them. Women who stopped using the pill more than 10 years ago do not seem to have any increased risk.

• Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT): Either as estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) or hormonal replacement therapy (HRT), MHT has been used for many years to help relieve symptoms of menopause and to help prevent thinning of the bones (osteoporosis).

• Combined MHT: It has become clear that long-term use (several years or more) of combined MHT (estrogen and progestin) (usually prescribed for women who have a uterus) increases the risk of breast cancer. Five years after stopping combined MHT, the risk seems to drop back to normal.

• ERT: The use of estrogen alone (usually prescribed for women without a uterus), does not seem to increase the risk of developing breast cancer. When used long-term (for more than 10 years), some studies have found that ERT increases the risk of ovarian and breast cancer.

• Not breastfeeding: Some studies have shown that breastfeeding slightly lowers breast cancer risk, especially if the breastfeeding lasts 1½ to 2 years. This could be because breastfeeding lowers a woman’s total number of menstrual periods, as does pregnancy.

• Alcohol: Use of alcohol is clearly linked to an increased risk of having breast cancer. Women who have one drink a day have a very small increased risk. Those who have two to five drinks daily have about 1½ times the risk of women who drink no alcohol. The ACS (2010) suggests limiting the amount to one drink per day.

• Being overweight or obese: Being overweight or obese is linked to a higher risk of breast cancer, especially for postmenopausal women and if the weight gain took place during adulthood. Central obesity appears to increase this risk even further especially in the post-menopausal woman. The link between weight and breast cancer risk is complex, and studies of fat in the diet as it relates to breast cancer risk have often given conflicting results (ACS, 2009, 2010).

• Lack of exercise: Studies show that exercise reduces breast cancer risk. The only question is how much exercise is needed. One study found that as little as 1 hour and 15 minutes to 2½ hours of brisk walking per week reduced the risk by 18%. Walking 10 hours a week reduced the risk a little more (ACS, 2009, 2010).

In addition uncertain risk factors may increase the risk of breast cancer but more research is needed. These factors include:

• High-fat diets: Studies of fat in the diet have not clearly shown that this is a breast cancer risk factor. Most studies found that breast cancer is less common in countries where the typical diet is low in fat. On the other hand, many studies of women in the United States have not found the cancer risk to be linked to how much fat they ate. Researchers are still not sure how to explain this difference. More research is needed to better understand the effect of the types of fat eaten and body weight on breast cancer risk.

• Antiperspirants and bras: Internet e-mail rumors have suggested that underarm antiperspirants can cause breast cancer. There is very little evidence to support this idea. Also there is no evidence to support the idea that underwire bras cause breast cancer.

• Abortions: There is a myth that abortions cause breast cancer. Several studies show that induced abortions do not increase the risk of breast cancer. There is no evidence to show a direct link between miscarriages and breast cancer.

• Breast implants: Silicone breast implants can cause scar tissue to form in the breast. But several studies have found that this does not increase breast cancer risk. If a woman has breast implants, she might need special x-ray views during mammograms.

• Pollution: Research has been undertaken to learn how the environment might affect breast cancer risk. At this time research does not show a clear link between breast cancer risk and environmental pollutants such as pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).

• Tobacco smoke: Most studies have found no link between active cigarette smoking and breast cancer. An issue that continues to be a focus of research is whether secondhand smoke (smoke from another person’s cigarette) may increase the risk of breast cancer. The evidence about secondhand smoke and breast cancer risk in human studies is not entirely clear but is thought to contribute to breast cancer occurrences. A possible link to breast cancer is yet another reason to avoid being around secondhand smoke (Fentiman, Allen, & Hamed, 2005).

• Night work: A few studies have suggested that women who work at night (nurses on the night shift, for example) have a higher risk of breast cancer. This is a fairly recent finding, and more studies are being done to look at this issue (Breast Cancer on the night shift, 2007; Stevens, 2009).

Determining a Woman’s Risk of Genetically Related Breast Cancer

Although knowing whether one is hereditarily predisposed to breast cancer may have benefits, the extent to which an individual can benefit remains unclear. Confirming one’s mutation status may provide a sense of control in life plans, yet may alternatively create high levels of anxiety and distress. Genetic testing can alter decisions regarding family and intimate relationships, childbearing, body image, and quality of life. Regardless of whether results are positive or negative in testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, they can have a highly negative effect on women’s lives.

Genetic counseling may not be an adequate measure for relieving the ensuing psychologic distress. Women at increased risk for breast cancer need comprehensive information about the benefits and limitations of genetic testing, in addition to alternatives, to ensure that informed decisions can be made about genetic testing. Nurses and other health care professionals should tailor care to women who have undergone genetic testing for hereditary breast cancer or those who plan to undergo testing, and they should impart current information related to these women’s specific emotional and medical needs. Because decisions regarding genetic testing, genetic counseling, and breast cancer risk assessment are highly individualized, health care professionals should be careful regarding any generalizations about women at risk for breast cancer. Women who carry a gene mutation have as high as an 80% risk of developing breast cancer. Men who carry the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene have a 6% risk (Shockney & Tsangaris, 2007).

In the past women and their family members risked having their health insurance coverage canceled because of being labeled with a preexisting condition when testing positive for a gene mutation. A federal law has been passed to prevent this in the future. The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) protects clients from having that information shared with health insurers or employers. Before enactment of the law, women who tested positive for one of the breast cancer genes could be denied insurance coverage or employment based on a predisposition to developing breast cancer years later. This law (a) prohibits the use of genetic information to deny employment or insurance coverage; (b) ensures that genetic test results are kept private; and (c) prevents an insurer from basing eligibility or premiums on genetic information (Kotz, 2008).

Information about breast cancer risks can be confusing, and women can overestimate or underestimate their risks. Women and health professionals can use the Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool to calculate risk. This tool was developed and verified by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to predict the risk of breast cancer in 5 years and over the lifetime (to age 90 years) of a woman. (The risk factors used are in Box 10-1; the tool is available at www.nci.nih.gov/bcrisktool/.)

An accurate estimation of risk for breast cancer is needed in order that women may be given rational management recommendations. During breast cancer risk counseling, facts should be presented to women in a supportive, nondirective way, without personal opinions or preferences. Discussion should also include treatment options and prognosis of breast cancer, as well as risks and benefits of alternative methods of prevention and early diagnosis. A woman’s recognition of having increased breast cancer risk can carry psychologic consequences such as anxiety, guilt, depression, and reduced self-esteem. High risk women who pass specific genetic mutations on to their children can experience enormous guilt. Psychologic intervention should be considered to assist these individuals in coping with these significant adverse sequelae (Shockney & Tsangaris, 2007).

Chemoprevention

Ongoing studies by the NCI and other groups are investigating the role of tamoxifen, raloxifene, and anastrozole in the prevention of breast cancer (NCI, 2009). Raloxifene, in postmenopausal women, prevents osteoporosis without the possible increased cancer risks of estrogen therapy. This medication may be an ideal choice for the woman at high risk for both osteoporosis and breast cancer. Tamoxifen has already reduced the recurrence of breast cancer in women with prior breast malignancies. Prevention studies are attempting to identify which women would most benefit from administration of these chemopreventive drugs. Although many women may want to start chemopreventive drugs for breast cancer prevention, the risk of occasional serious side effects demands careful consideration before prescribing these drugs (see later discussion) (Shockney & Tsangaris, 2007).

Pathophysiology

Breast cancer occurs when there are genetic alterations in the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of breast epithelial cells. Many types of breast cancer exist. Genetic alterations, either inherited or spontaneous, are found in the epithelial cells, compromising ductal or lobular tissue. Researchers are investigating which oncogenes (potentially cancer-inducing genes) may cause breast cancer or change its growth pattern and how the process can be stopped.

Breast cancer begins in the epithelial cells lining the mammary ducts of the breast. The rate of breast cancer growth depends on the effect of estrogen and progesterone and other prognostic factors such as its grade, Ki67 score, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)/neu receptor status, and other variables. These cancers can be either invasive (infiltrating) or noninvasive (in situ). Invasive or infiltrating breast cancers can grow into the wall of the mammary duct and into the surrounding tissues.

By far the most frequently occurring cancer of the breast is invasive ductal carcinoma. Ductal carcinoma originates in the lactiferous ducts and invades surrounding breast structures. The tumor is usually unilateral, not well delineated, solid, nonmobile, and nontender.

Lobular carcinoma originates in the lobules of the breasts. This type of breast cancer can be nonpalpable and appear smaller on imaging studies than it actually is.

Nipple carcinoma (Paget’s disease) originates in the nipple. It usually occurs with invasive ductal carcinoma and can cause bleeding, oozing, and crusting of the nipple.

A more rare form of breast cancer is known as inflammatory breast cancer. This type of cancer is diagnosed by the appearance of a rash or reddish skin of the breast. It can be misdiagnosed as mastitis. A skin punch biopsy is performed to diagnose it, and the pathology report will state that there are breast cancer cells in the dermal lymphatic channels. It is usually aggressive and is classified as stage II breast cancer from its onset. There are also other types of less common forms of breast cancer such as mucinous and malignant phyllodes tumors.

Breast cancer can invade surrounding tissues in such a way that the primary tumor can have tentacle-like projections (referred to as being a “spiculated mass”). This invasive growth pattern can result in the irregular tumor border felt on palpation. As the tumor grows, fibrosis develops around it and can shorten Cooper’s ligaments, which result in the characteristic peau d’orange (orange peel–like skin) changes and edema associated with some breast cancers. If the breast cancer invades the lymphatic channels, tumors can develop in the regional lymph nodes, often occupying the axillary lymph nodes. The tumor may invade the outer layers of skin, creating ulcerations.

Metastasis results from seeding of the breast cancer cells into the blood and lymph systems, leading to tumor development in the bones, the lungs, the brain, and the liver (Table 10-2).

TABLE 10-2

STAGING FOR BREAST CANCER∗

| STAGE | DEFINITION |

| Stage 0 | Carcinoma in situ (intraductal carcinoma, lobular carcinoma, Paget disease) (Tis-N0-M0) |

| Stage I | Tumor <2 cm with negative nodes (T1-N0-M0) (includes microinvasive T1, <0.1 cm) |

| Stage IIA | Tumor 0 to 2 cm with positive nodes (including micrometastasis N1, or <0.2 cm), or 2 to 5 cm with negative nodes (T0-N1, T1-N1, T2-N0, all M0) |

| Stage IIB | Tumor 2 to 5 cm with positive nodes or >5 cm with negative nodes (T2-N1, T3-N0, all M0) |

| Stage IIIA | No evidence of primary tumor or tumor <2 cm with involved fixed lymph nodes, or tumor >5 cm with involved movable or nonmovable nodes (T0-N2, T1-N2, T2-N2, T3-N1, T3-N2, all M0) |

| Stage IIIB | Tumor of any size with direct extension to chest wall or skin, with or without involved lymph nodes, or any size tumor with involved internal mammary lymph nodes (T4–any N, any T–N3, all M0) |

| Stage IV | Any distant metastasis (includes ipsilateral supraclavicular nodes) (any T, any N) (all M1) |

∗Breast cancer is most frequently staged according to the TNM classification system, which evaluates the tumor size (T), involvement of regional lymph nodes (N), and distant spread of the disease or metastases (M).

Source: From National Cancer Institute. (2010). Staging information for breast cancer. Available at www.cancer/gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/breast/healthprofessional/pge4#section_30. www.nccn.org. Accessed June 9, 2010.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

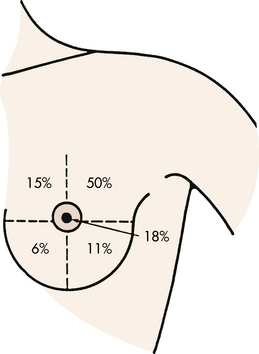

Breast cancer in its earliest form can be detected on a mammogram before it can be felt by the woman or her health care provider. It is estimated, however, that women detect 90% of all breast lumps. Of this 90%, only 20% to 25% are malignant. More than half of all lumps are discovered in the upper, outer quadrant of the breast (Fig. 10-2). The most common initial symptom is a lump or thickening of the breast. The lump may feel hard and fixed or soft and spongy. It may have well-defined or irregular borders. It may be fixed to the skin, causing dimpling to occur. A bloody or clear nipple discharge also may be present. Pain may be present in approximately 10% of women.

FIG. 10-2 Relative location of malignant lesions of the breast. (Modified from DiSaia, P., & Creasman, W. [2007]. Clinical gynecologic oncology [8th ed.]. St. Louis: Mosby.)

Unilateral and spontaneous discharge (without nipple manipulation) is associated with mastitis, intraductal papilloma, and cancer. The discharge is usually intermittent and persistent and may be clear, serous, green-gray, purulent, serosanguineous, or sanguineous. Women with these findings need a complete diagnostic workup to determine the actual cause of their symptoms.

As a general principle, any unilateral breast symptom (i.e., mass, discharge, pain, or itching) is a more ominous finding than a bilateral symptom. However, all findings must be carefully followed up to avoid missing a serious diagnosis such as cancer. A delay in treatment may adversely affect the woman’s subsequent prognosis and treatment options.

Early detection and diagnosis reduce the mortality rate because the cancer is found when it is smaller, lesions are more localized, and there tends to be a lower percentage of positive nodes. Therefore it is imperative that protocols for assessment and diagnosis be established. The use of clinical examination by a qualified health care provider and screening mammography (x-ray filming of the breast) (Fig. 10-3) may aid in the early detection of breast cancers. BSE may be beneficial and can lead to a woman reporting new breast symptoms promptly to her health care provider (see Chapter 4). Table 10-3 lists the recommendations of the ACS for breast cancer screening (ACS, 2010). These recommendations stand despite a 2009 recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF, 2009) to make changes. Box 10-2 provides the USPSTF recommendations and selected responses from professional organizations.

TABLE 10-3

SCREENING GUIDELINES FOR EARLY BREAST CANCER DETECTION

∗The best age to start should be decided between physician and woman after looking at her individual status.

Source: American Cancer Society. (2010). Cancer facts and figures, 2010. Atlanta: Author.

Research has suggested that the major obstacles to breast cancer screening include older age; fiscal barriers (e.g., expense, lack of health insurance); knowledge, attitudinal and behavioral barriers (e.g., fear, ignorance, lack of motivation); and organizational barriers (e.g., scheduling problems, lack of availability of mammography services, lack of physician referral) (Shockney & Tsangaris, 2007). Strategies that may be helpful to health care providers in improving screening for breast cancer include education and encouragement of older women, continuing education of providers, provision of information about new and affordable screening options, use of reminder systems in office practice, use of client-directed literature, and interventions that will reward, support, and prompt desired screening behaviors (Shockney & Tsangaris). In addition, it is important for a practitioner to assess the technique of a woman who is practicing BSE.

Cultural factors may influence a woman’s decision to participate in breast cancer screening. Knowledge of these factors and use of culturally sensitive, tailored messages and materials that appeal to the unique concerns, beliefs, and reading abilities of target groups of underutilizers may assist the nurse in helping women overcome barriers to seeking care (see Cultural Considerations box).

Mammography today remains the gold standard for breast cancer screening and early detection. New technologies that are considered for breast cancer screening must equal or exceed the performance of screen-film mammography to be accepted as screening tools for breast cancer. In other words, these technologies must demonstrate identification of more breast cancers that are missed by mammography, such as a higher fraction of early stage cancers (stages 0 and I), and be cost-effective, noninvasive, and available and acceptable to clients. Full field digital mammography (FFDM) is much like standard film mammography in that x-rays are used to produce an image of the breast. Film mammography is captured on x-ray film, however, and digital mammography is recorded using a computer. Digital mammography has proven to be more accurate in identifying subtle abnormalities within the breast architecture and as a result of research studies has proven to be 28% more accurate in identifying cancer than traditional film mammography (Pisano, Acharyya, Cole, Marques, Yaffe, Blevins, et al., 2009). These images enable the radiologist to enlarge the image as well as lighten and darken the background contrast, finding abnormalities that may go undetected with film mammography. It is also critically important that the radiologist reading the mammograms be expert in doing so. Studies have verified that general radiologists reviewing mammograms can miss the presence of breast cancer on imaging 41% of the time compared to dedicated breast imaging radiologists who specialize in breast imaging and read a large volume of mammograms weekly (Ciatto, Ambroghetti, Morrone, & Del Turco, 2006). An additional method to assist radiologists with reading mammograms, which can be important for facilities who do not have dedicated breast imaging radiologists, is computer-aided detection and diagnosis (CAD). For nearly two decades this device has been in use to help radiologists find suspicious changes on mammography studies. This can be especially important for film mammography evaluation. CAD electronically scans the mammogram first. It can detect tumors or other breast abnormalities and flag them for the radiologist to further investigate (ACS, 2010).

A screening mammogram is performed on women who do not have any signs or symptoms of a breast abnormality. Diagnostic mammograms are performed when a screening mammogram identifies something warranting further inspection or if the woman or her physician or nurse finds a symptom such as a lump, nipple discharge, or other breast symptom that is new.

One of the most valuable uses of mammography is the identification of calcifications within the breast. Though most are benign, some can be an early sign of breast cancer. There are two types of calcifications:

• Macrocalcifications are mineral deposits that are most likely changes in the breast caused by aging of the breast arteries, old injuries, or inflammation. They appear as large white dots or dashes. These deposits are related to noncancerous conditions and do not require a biopsy. These types of calcifications are found in about half of women older than age 50 and in 1 in 10 women younger than 50.

• Microcalcifications are fine white specks of calcium in the breast. They may be alone or in clusters and resemble grains of sand or salt. These can be more concerning depending on their pattern and shape. Those that are tightly clustered together and have irregular edges can be a sign of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or early stage I breast cancer, and warrant biopsy.

Mammography does have its limitations. It has not proven helpful in screening younger women due to the high breast density associated with youth. Roughly 80% of breast cancer can be identified through the application of mammography when combined with clinical breast examination; however, 20% may be missed (Shockney & Tsangaris, 2007). Ultrasound has become a valuable screening adjunct to mammography, especially for women with significant breast density. It is cost-effective, noninvasive, and widely available. Ultrasound has been helpful in distinguishing between fluid-filled masses (cysts) and solid masses (benign and malignant). It uses high-frequency sound waves to assess the breast tissue and axillae. The test is painless and noninvasive and requires no exposure to radiation. It has also been useful in performing image-guided biopsies (ACS, 2010).

MRI has also become a valuable screening adjunct to mammography and ultrasound. MRI of the breast has shown an overall sensitivity to breast cancer of 96%. However, factors such as cost, lack of standardized examination technique and interpretation criteria, insensitivity to microcalcifications, and higher rate of false-positive results than mammography have caused concern regarding the potential of breast MRI as a screening method (Shockney & Tsangaris, 2007). There is growing popularity to use it for women diagnosed with breast cancer to rule out the presence of multicentric disease and determine the size of tumors (such as invasive lobular carcinomas), and it has been used increasingly for women who are identified as high risk (such as those who carry a BRCA gene mutution).

When a suspicious finding on a mammogram is noted or a lump is detected, diagnosis is confirmed by core needle biopsy (stereotactically or ultrasound-guided core), or by needle localization biopsy (Fig. 10-4). The latter procedure requires the collaborative efforts of both the radiologist and the surgeon. This often requires that the procedure take place in two different environments (radiology and surgery), so women need specific information regarding procedures, duration, and outcomes. In most facilities, core biopsies can be performed and the pathology results known the following day, providing the woman with rapid results. Recognizing the woman’s high anxiety level is important, and the sooner the outcome of the biopsy can be provided the sooner she can have her fears allayed or confirmed.

Prognosis

Major advances have been made in the understanding of the biology of cancer. Breast cancer is thought to be a systemic disease, which means that micrometastasis could be present at the initial presentation with or without nodal involvement. The area in which affected lymph nodes are located also is prognostic. The involvement of axillary lymph nodes worsens the prognosis of breast cancer. Nodal involvement and tumor size remain the most significant prognostic criteria for long-term survival (Fig. 10-5).

Other biologic factors have been shown to be helpful in predicting response to therapy or survival. These factors include estrogen receptor assay, progesterone receptor assay, tumor ploidy (the amount of DNA in a tumor cell compared with that in a normal cell), S-phase index or growth rate (the percentage of cells in the S phase of cellular division done by flow cytometric determinations of the S-phase fraction), Ki67 (another proliferation marker), and histologic or nuclear grade (Shockney & Tsangaris, 2007). Estrogen and progesterone receptors are proteins in the cell cytoplasm and surface of some breast cancer cells. When these receptors are present, they bind to estrogen or progesterone, and binding promotes growth of the cancer cell. A breast cancer can have estrogen or progesterone receptors (ERs, PRs) or both types. It is valuable to know the ER status of the cancer to predict which women will respond to hormone therapy (Nelson, Fu, Griffin, Nygren, Smith, & Humphrey, 2009). Molecular and biologic factors are valuable indicators for prognosis and treatment of breast cancer. HER2, which is associated with cell growth, is overexpressed in 30% of all breast cancers and is associated with loss of cell regulation and uncontrolled cell proliferation. Thus a positive HER2 status is associated with aggressive tumors, poor prognosis, and resistance to certain chemotherapeutic drugs (ACS, 2010).

Care Management

Controversy continues regarding the best treatment of breast cancer. Nodal involvement, tumor size, receptor status, and aggressiveness are important variables for treatment selection. Medical management of breast cancer includes surgery, breast reconstruction, radiation therapy, adjuvant hormone therapy, biologic targeted therapy, and chemotherapy. Many women face difficult decisions about the various treatment options. Box 10-3 lists questions that must be addressed in decision making.

Surgery

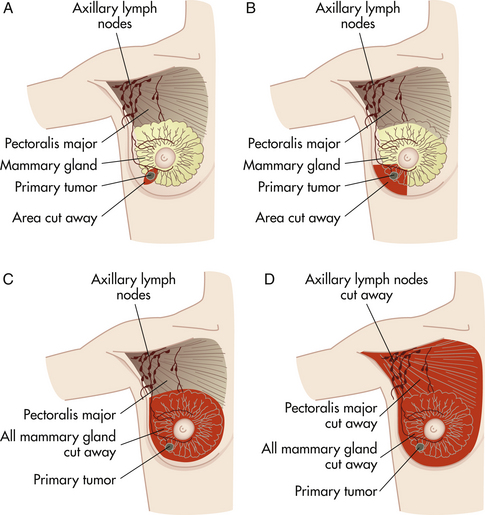

After a diagnosis of breast cancer is made, surgical treatment options are offered to the woman. The most frequently recommended surgical approaches for the treatment of breast cancer are lumpectomy and total simple mastectomy. A lumpectomy (Fig. 10-6) involves the removal of the breast tumor and a small amount of surrounding healthy tissue to ensure there are clean margins. Partial mastectomy (see Fig 10-6, B) includes tylectomy, wide excision, and quadrantectomy or segmental mastectomy and involves removal of the tumor, which may be larger, along with a rim of healthy tissue around it, again to ensure clear margins. For women whose breast cancer is invasive, a sentinel node biopsy will be performed. The sentinel node is the first node that receives lymphatic drainage from the tumor, and is identified by injecting vital blue dye or radioactive dye in the area surrounding the tumor. A small incision in the axilla allows for identification of the blue-stained lymphatic channel leading to the blue sentinel node, either visually or by gamma probe. This node then can be removed and examined for the presence of tumor cells, as opposed to an entire axillary dissection.

FIG. 10-6 Surgical alternatives for breast cancer. A, Lumpectomy. B, Partial mastectomy. C, Total (simple) mastectomy. D, Radical mastectomy.

It is helpful in determining the need for adjunctive systemic treatment by indicating whether nodes are positive for metastatic cells. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy are minimally invasive techniques that identify women with axillary node involvement.

Clinical trials have reported identification of the sentinel node in more than 95% of cases, with false-negative rates for predicting axillary nodal metastases of less than 5% (Krag, Ashikaga, Harlow, Skelly, Julian, Brown, et al., 2009; Quan, Wells, McCready, Wright, Fraser, & Gagliardi, 2010).

Identification of the sentinel node is usually done through a separate incision at the time of these procedures, and surgery is usually followed by radiation therapy to the remaining breast tissue (DiSaia & Creasman, 2007). These procedures are used for the primary treatment of women with early stage (I or II) breast cancer. Lumpectomy offers survival equivalent to that of having a total simple mastectomy (DiSaia & Creasman). Additional criteria for recommending lumpectomy/partial mastectomy are as follows: a tumor that is relatively small compared to breast volume; no previous breast radiation; no previous mantle field radiation (area includes neck, chest, and underarm lymph nodes) as a youth; and no evidence of multicentric disease.

Mastectomy is the removal of the breast, including the nipple and areola. Women who are advised to have mastectomy instead of lumpectomy are women who have:

• Multiple tumors in the breast occupying several quadrants of the breast

• Extensive DCIS that occupies a large area of the breast tissue

Deciding which mastectomy to have will be guided by the breast surgeon, but as always the woman should have an active part in any decisions that directly affect her treatment. There are several different types of mastectomies. These include:

• Total simple mastectomy: This is removal of the breast, nipple and areola. No lymph nodes from the axillae are taken. Recovery from this procedure, if no reconstruction is done at the same time, is usually 1 to 2 weeks. Hospitalization varies; for some it may be an outpatient procedure, whereas other women may require an overnight stay (see Fig 10-6, C).

• Modified radical mastectomy: This procedure is removal of the breast, nipple and areola as well as axillary node dissection. Recovery, when surgery is done without reconstruction, is usually 2 to 3 weeks.

• Skin-sparing mastectomy: This is the removal of the breast, nipple and areola, keeping the outer skin of the breast intact. It is a special method of performing a mastectomy that allows for a good cosmetic outcome when combined with a reconstruction done at the same time. A tissue expander may also be placed as a space holder for later reconstruction.

• Nipple-sparing mastectomy: This kind of mastectomy is reserved for a smaller number of women with tumors that are not near the nipple areola area. The surgeon makes an incision on the outer side of the breast or around the edge of the areola and hollows out the breast, removing the areola and keeping the nipple intact. Sometimes the completed reconstruction is performed at the same time and in other cases, a tissue expander is inserted as a space holder for later reconstruction.

• Nipple- and areola-sparing mastectomy: In this procedure, the surgeon makes an incision on the side of the breast or in some cases, around the edge of the areola. The breast is hollowed out and reconstruction is performed at the same time. In some cases, a tissue expander may be placed as a space holder for later reconstruction.

• Scar-sparing mastectomy: In this procedure, the affected breast is hollowed out. Whether done as skin sparing, nipple sparing, areola sparing or a combination, one goal of this surgery is to minimize visible surgical incisions. It is not uncommon for an entire mastectomy procedure to be performed through an opening that is less than 2 inches in length.

•Preventive/prophylactic mastectomy: Prophylactic mastectomy is designed to remove one or both breasts in order to dramatically reduce the risk of developing breast cancer. Women who test positive for certain genetic mutations like BRCA1 and BRCA2, or who have a strong family history of breast cancer, may elect this kind of surgery. They may also elect to have their ovaries removed at the same time. Genetic counseling may help to confirm or eliminate any nagging suspicion about family history. When this type of mastectomy is performed, no lymph nodes need to be removed because there is no evidence of cancer present. It is necessary to have a mammogram performed within 90 days of the procedure to ensure that it is healthy breast tissue being removed for preventive purposes.

Breast Reconstruction

The goals of surgical breast reconstruction are achievement of symmetry and preservation of body image. Surgical reconstruction can be done immediately or at a later date. Immediate reconstruction at the time of mastectomy does not change survival rates or interfere with therapy or the treatment of recurrent disease. It is important that women be aware of this. Women choosing surgical reconstruction offer the following rationale for reconstructive surgery: the need to feel complete again, to avoid using an external prosthesis, to achieve symmetry, to decrease self-consciousness about appearance, and to enhance femininity.

In the past 10 years major achievements have been made in breast reconstruction following mastectomy surgery. No longer do women need to face long, jagged scars that affect their self-image. Instead, advanced techniques have given plastic surgeons the tools to rebuild a woman’s breast in such a way that her silhouette is once again whole.

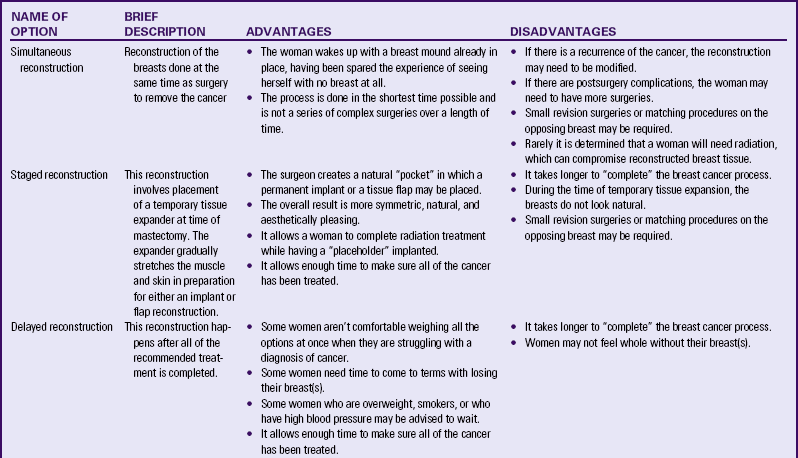

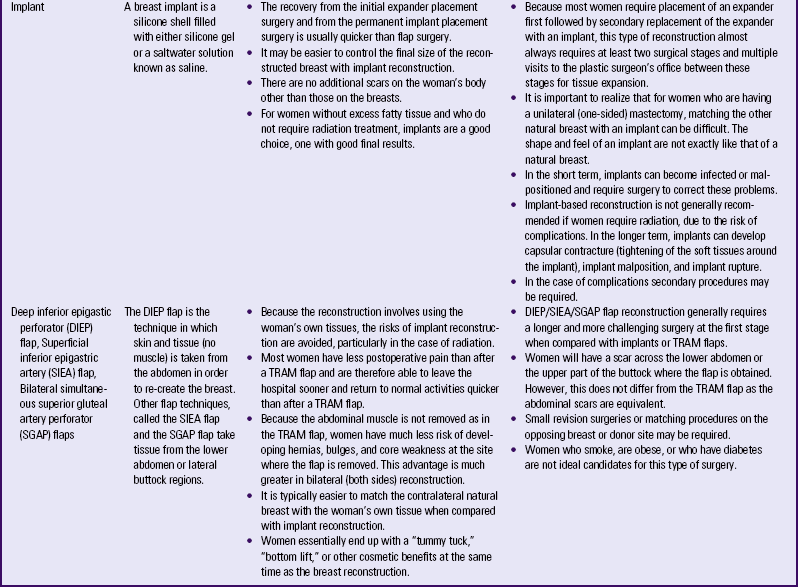

Women with breast cancer have two main considerations when considering reconstructive surgery—when to have surgery and what type of surgery to have. The options for when to have reconstruction are:

• Simultaneous reconstruction: Women have the option to have immediate reconstruction of their breast(s) at the same time as their mastectomy. This is a reasonable option for women who do not need breast irradiation.

• “Staged” reconstruction: Many women who require radiation therapy are advised to have staged reconstruction. If radiation is done on a newly reconstructed breast, over time it can alter its cosmetic appearance, making an implant hard, painful, deformed, contracted, or even exposed. It may also cause severe fibrosis or shrinkage of the fatty tissue that may have been used in rebuilding the breast.

• Delayed reconstruction: A woman may opt for delayed reconstruction if, after her mastectomy, a plastic surgeon was not involved. Many women who did not know their options at the time of mastectomy fall into this category. More and more these women are discovering that surgically re-creating their breasts is possible and is required to be covered by insurance as a result of a federal law passed in 1998.

The types of surgical option for breast reconstruction include implants and flap procedures. Implants are made out of silicone or saline or a combination of both, and can be inserted at the same time as a mastectomy or later. They are placed underneath the chest muscle versus on top of it, as in the case of breast augmentation. Silicone implants have been deemed safe and are an option for women having breast reconstruction following mastectomy.

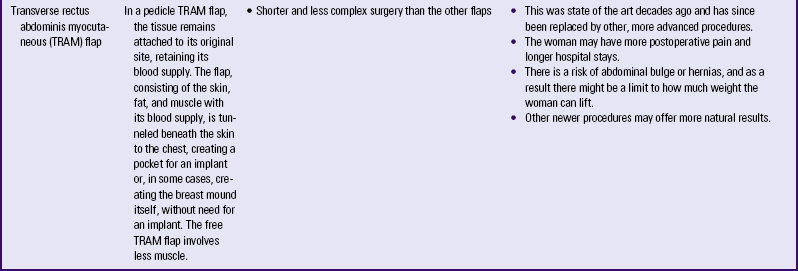

Flap procedures are done by plastic and reconstructive surgeons who specialize in microsurgery. During flap reconstruction, a breast is created using tissue taken from other parts of the body, such as the abdomen, back, buttocks, or thighs, which is then transplanted to the chest by reconnecting the blood vessels to new ones in the chest region. Due to the high level of skill required for microsurgery, as well as the equipment and staff needed, these techniques are available only at specialized centers. Most breast centers are still performing flap surgery the “old fashioned” way if they do not have surgeons with these skills. These older procedures (transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous [TRAM] flaps and latissimus dorsi flaps) result in the woman sacrificing either her abdominal muscles or her upper back muscles. Although these procedures were the best options decades ago, there is a higher risk of hernia, weakness, abdominal bulging, and limits on physical activity when these older procedures are performed. There are no physical limitations when today’s more sophisticated procedures are performed (Hedén, Bronz, Elberg, Deraemaecker, Murphy, Slicton, et al., 2009). Table 10-4 compares the advantages and disadvantages of the various reconstruction options.

TABLE 10-4

RECONSTRUCTIVE BREAST SURGERY OPTIONS

Source: Shockney, L., & Tsangaris, T. (2008). Johns Hopkins breast cancer handbook for health care professionals. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

After a woman has recovered from initial reconstructive surgery, she may choose to have nipple and areolar reconstruction. Nipple reconstruction is achieved by using an autologous skin graft to construct a nipple, either from tissue from the remaining nipple or from a donor site. Tiny flaps from the new breast itself also may be used. This outpatient procedure requires local anesthesia, intravenous sedation, or a combination of both, depending on how much sensation has returned to the breast. The procedure lasts about an hour and, 4 weeks later, tattooing may be used to create an areola and match the color of the natural nipple (Valea & Katz, 2007).

Radiation

As mentioned, the conservative approach to treatment involves lumpectomy followed by radiation therapy as standard therapy for early stage breast cancer. Radiation to the breast destroys tumor cells remaining after manipulation and handling of the tumor during surgery. The total recommended radiation dose is 4500 to 5000 cGy over a 6- to 8-week period. A booster dose of up to 1000 cGy may be prescribed with the use of either implants or external beam irradiation (Shockney & Tsangaris, 2007). The risk of local recurrence depends on several treatment factors such as extent of breast resection, tumor margins, technical details of radiation therapy, and the use of adjuvant systemic therapy. Although radiation after lumpectomy surgery is standard protocol, some large breast tumors (due to the disease being locally advanced) may be irradiated before surgery to facilitate easier surgical removal. Side effects of radiation therapy include swelling and heaviness in the breast, sunburn-like skin changes in the treated area, and fatigue. Changes to the breast tissue and skin usually resolve in 6 to 12 months. The breast may become smaller and firmer after radiation therapy. Radiation therapy in the area of the axilla can cause lymphedema of the ipsilateral arm. Close medical follow-up is important after conservative surgery and radiation. Recommended guidelines include a breast physical examination every 4 to 6 months for 5 years, and then yearly. A mammogram is recommended 6 months after radiation and then annually (National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN], 2009).

A variety of radiation methods are widely used. These include accelerated therapy and brachytherapy.

• Accelerated breast radiation. External beam radiation for 6 weeks, 5 days a week, can be very inconvenient for a woman. Research has been conducted to develop ways to shorten this time frame and still deliver the therapy needed to prevent recurrence of this disease. Accelerated radiation was created with this goal in mind and delivers a slightly larger dose of radiation over a 3-week period. Skin changes (resembling sunburn) can be slightly more prevalent because of the more intense period of time and corresponding dosage.

• Brachytherapy. Initially created for other types of cancer, like prostate, this form of radiation enables the client to complete her radiation in an even shorter time and is not delivered via external beam. Instead a deflated balloon is inserted into the space left by the lumpectomy and is filled with saline. The balloon is left in place until the margins are confirmed as clear. The balloon is removed and replaced with another balloon specifically created to allow radiation to be inserted within it. Radiation rods or seeds are inserted into the balloon device each day for 5 days, and the radiation is completed, at which time the balloon is then removed. This enables partial breast radiation to be delivered, recognizing that most local recurrences happen at or near the location of the original cancer.

Adjuvant Systemic Therapy

Chemotherapy administered soon after surgical removal of the tumor is referred to as adjuvant chemotherapy. The role of adjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of breast cancer (chemotherapy and endocrine therapy) is either to eradicate or impede the growth of micrometastatic (microscopic cell metastasis) disease. Often it is not possible to detect the presence of micrometastasis at the time of initial treatment, and when it is present, mutations can occur in the tumor cells. These mutations make tumor cells resistant to the effects of chemotherapeutic agents despite tumor sensitivity to drug therapy being greatest when the tumor burden is small. Consequently the prediction cannot be made with confidence that all tumors of 1 cm or less can be cured with initial local and regional treatment. The early introduction of systemic adjuvant therapy, as determined by the estimated risk of tumor recurrence in certain subsets of women with node-negative disease, is a prudent course of treatment. Research findings suggest that adjuvant chemotherapy significantly reduces the risks for recurrence and mortality in women with node-positive disease (Valea & Katz, 2007). For women diagnosed with early stage breast cancer and favorable prognostic factors (hormone receptor positive and HER2/neu negative), a special pathology test may be performed to help determine the woman’s risk of recurrence. This test, called Oncotype DX, provides a score that represents the likelihood of her specific cancer recurring. Such information can be useful for women whose known benefit for receiving chemotherapy may be minimal based on her prognostic factors from the tumor itself. For women with a low score, commonly only hormonal therapy is recommended, and for those with a high score usually chemotherapy is strongly considered.

Hormonal therapy: To determine whether a woman is a candidate for hormonal therapy, a receptor assay is done. After the entire tumor or a portion is removed by biopsy or excision, a pathologist examines the cancer cells for ERs and PRs.

The presence of a receptor on the cell wall indicates that the woman is positive for that type of hormone receptor. If these receptors are present, the growth of the woman’s breast cancer can be influenced by estrogen, progesterone, or both. It is unknown exactly how these hormones affect breast cancer growth. Bilateral oophorectomy has been noted to benefit women diagnosed with their first breast cancer before age 50 by reducing exposure to endogenous estrogen. Oophorectomy reduces the risk of breast cancer by approximately 50% in BRCA1 carriers (Shockney & Tsangaris, 2007). Thus oophorectomy may be an option that helps decrease the odds of recurrence and improve length of survival. In addition to or instead of oophorectomy, medications may be given to stop tumor growth that is influenced by hormones. Ovarian suppression may also be recommended by a medical oncologist as part of the hormonal therapy treatment.

There are several hormonal therapy drugs. Tamoxifen, the oldest one and the one used the longest, is an oral antiestrogen medication that mimics progesterone and estrogen. Tamoxifen attaches to the hormone receptors on cancer cells and prevents natural hormones from attaching to the receptors. When tamoxifen fits into the receptors, the cell is unable to grow. Research has demonstrated a clear benefit for use of tamoxifen in all age-groups (Brauch, Mürdter, Eichelbaum, & Schwab, 2009). Adjuvant hormonal therapy with tamoxifen is recommended for most premenopausal women with breast cancer whose tumors are hormone receptor positive. In this age-group, adjuvant tamoxifen therapy improves disease-free survival and, in some cases, length of survival. Use of hormonal therapy for 5 years in premenopausal women with breast cancer significantly reduces recurrence and mortality rates.

The NCCN guidelines (2009) recommend giving adjuvant hormonal therapy to women with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer regardless of menopause status, age, or HER2/neu status, with the exception of women with lymph node–negative cancers less than or equal to 0.5 cm, or 0.6 to 1 cm in diameter with favorable prognostic features. Women treated with hormonal therapy should receive therapy for at least 5 years. Use beyond 5 years in node-positive women results in a reduction

in beneficial effects with an increase in toxicity, although the optimal duration of tamoxifen administration is under investigation (Brauch et al.) (see Medication Guide: Tamoxifen).

Raloxifene is an oral selective ER modulator. It is used to prevent osteoporosis in menopausal women. It works as well as tamoxifen in decreasing invasive breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women with a high risk for breast cancer with fewer thromboembolic events and lower risk of uterine cancer (see Medication Guide: Raloxifene Hydrochloride).

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) is a classification of hormonal therapy in use. It markedly suppresses plasma estrogen levels in postmenopausal women by inhibiting or inactivating aromatase, the enzyme responsible for synthesizing estrogens from androgenic substrates (Brauch et al., 2009). AIs such as anastrozole, letrozole, and exemestane are effective agents in hormonal therapy for breast cancer. Clinical trials indicate that letrozole is convincingly better than tamoxifen in treating advanced disease in postmenopausal women, and anastrozole is at least as good. In early stage breast cancer, adjuvant therapy with anastrozole appears to be superior to adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen in reducing recurrence in postmenopausal women. AIs appear to be well tolerated with lower incidence of adverse effects as compared to tamoxifen. AIs are more commonly given to postmenopausal women whose tumors are hormone receptor positive (Shockney & Tsangaris, 2007) (see Medication Guide: Letrozole).

Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy drugs are most often given in combination regimens, which have been shown to improve or increase the disease-free survival time after therapy. The

most common chemotherapy regimens used for adjuvant treatment of node-positive and node-negative tumors are listed in Box 10-4.

Adjuvant chemotherapy has been most useful in premenopausal women who have breast cancer with positive nodes, regardless of hormone receptor status. It is postulated that younger women often have tumors with a higher S-phase fraction and proliferative rate, which makes the tumors more sensitive to chemotherapy. Although adjuvant chemotherapy effectively decreases the risks for recurrence and mortality in premenopausal women with node-positive disease, postmenopausal women can also be offered chemotherapy, depending on the cancer size, nodal involvement, and morphologic and biologic factors or markers of the particular cancer (Shockney & Tsangaris, 2007).

Chemotherapy with multiple drug combinations is used in the treatment of recurrent and advanced breast cancer with positive results. First-line single agents for women with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer include paclitaxel, docetaxel, epirubicin, doxorubicin, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, capecitabine, vinorelbine, and gemcitabine. Combination regimens and sequential single agents may be used (NCCN, 2009). Because chemotherapy drugs kill rapidly reproducing cells, treatment also affects normal body cells that rapidly reproduce (red and white blood cells, gastric mucosa, and hair). Thus chemotherapy can cause leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, gastrointestinal side effects (nausea, vomiting, anorexia, mucositis), and partial or full hair loss.

Chemotherapy treatments are usually administered in ambulatory care settings once or twice per month. During the informed consent process, before the treatment is selected, the woman and her family members should be educated about the names of the medications, routes of administration, treatment schedule, timing and ordering of medications, length of time of administration, reimbursed and unreimbursed costs of therapy, potential side effects, management of side effects, possible changes in body image (e.g., full or partial hair loss), recovery time after treatment (necessitating lost work time), and need for a caregiver to transport the woman to treatment and care for her afterward. Depending on the medications used, the treatments may include intravenous, subcutaneous, and oral administration. Often a long-term central venous catheter is inserted when the women will be receiving chemotherapy for an extended period or when she will receive medications that may damage the vein. Presence of a central venous catheter, hair loss, loss of part or all of her breast, menopause, and possible infertility all have the potential to cause a change in body image and increase emotional distress for the woman with breast cancer.

Breast cancer treatment with chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, or a combination of the two often causes changes in reproductive function. The premenopausal woman may experience these changes along with symptoms of menopause and possible infertility. It is not known whether hormonal therapy to ease the effects of menopause is safe for women with breast cancer; therefore, it is not recommended. For this reason the nurse must use other measures to help the woman cope with menopause (see Chapter 6). A young woman with breast cancer may become devastated by early and abrupt menopausal symptoms and the possibility of jeopardized reproductive function. A postmenopausal woman must cope with unpleasant side effects from chemotherapy and loss of part or all of her breast, and frequently, with treatment side effects superimposed on the presence of comorbidities that develop with aging.

Women receiving chemotherapy and their partners must understand that chemotherapy can be teratogenic, that is, chemotherapy agents can cause congenital birth defects. Any woman who is of childbearing age and receiving chemotherapy, even though no longer menstruating, must use birth control. Birth control pills are not recommended because they contain hormones that may assist in the growth of cancer. A birth control method must be chosen with the assistance of a gynecologist and a medical oncologist, and it must be used before chemotherapy begins and continue to be used until the medical oncologist and gynecologist believe it is safe to discontinue. Although a woman may not be menstruating, she may still be able to get pregnant.

Care Management

Nursing care of a woman with breast cancer will depend on the treatment option that has been chosen. Data that will guide the care include a client history, a physical examination, laboratory and diagnostic test results, and psychosocial assessment (see Nursing Process box).

Emotional Support After Diagnosis

When a woman is confronted with a diagnosis of cancer, she faces not only possible major changes in appearance but also the possibility of death. The emotional reaction to the diagnosis of cancer is always intense, and the many disruptions caused by the disease challenge the woman’s and family’s ability to cope. Disruptions may be caused by costs of treatment, loss of role function, lack of stress-relieving activities, spouse’s or child’s reaction to the diagnosis, change in body image and sexual function, disability, and pain. The woman may feel despair, fear, and shame. Sexuality issues related to breast cancer include a change in body image, changes in sexual function (such as decreased vaginal lubrication caused by hormonal therapy), and relational distress. Health care providers are responsible for discussing the influence of breast cancer on the woman’s life and in assisting the woman and her family in coping effectively with these changes. Nurses need to be especially aware of the individual quality of life needs of their clients and deliver interventions that improve quality of life outcomes within the context of the breast cancer survivor’s personal history, life cycle concerns, and psychosocial life stage.

Women and their families often undergo a period of distress after the diagnosis of cancer. It is difficult to accept the diagnosis of cancer when the woman may feel and look well. This period is characterized by anguish and shock followed by disbelief and denial. During this time absorbing information and education can be difficult, and the nurse should be sensitive as to how this may affect decision-making abilities. Flexibility is the key to sensitive nursing care. As the woman and family begin to accept the diagnosis of breast cancer, more and more information can be shared, and care planning with full client participation can take place, including the following:

• Validate and reinforce accurate information processing by the woman and her family.

• Assist in client decision making and arrange for the woman to speak with breast cancer survivors who have chosen a variety of treatment options (see Box 10-3).

• Suggest approaches the woman might take to deal with the sexual concerns of her significant other.

• Discuss the application of alternative therapies to alleviate stress and promote healing, such as exercise, guided imagery, meditation, and progressive muscle relaxation.

• Refer the woman to the ACS’s Reach to Recovery program or other resources that provide trained survivor volunteers for one-on-one support.

• Refer the woman to a cancer rehabilitation program, such as ENCORE, an exercise program run by the YWCA.

The NCCN (www.nccn.org) and the ACS (www.cancer.org) provide specific, up-to-date recommendations on breast cancer treatments on the Internet. These are invaluable resources for women to learn about scientifically tested treatment protocols for each stage of breast cancer.

After assisting the woman with accepting the diagnosis and obtaining support, consider nursing care in the preoperative, postoperative, and convalescent periods. The discussion that follows is pertinent to the care required by a woman who is having a modified radical mastectomy (see Nursing Care Plan).

Preoperative Care

General preoperative teaching and care are given, including expectations regarding physical appearance, pain management, equipment to be used (e.g., intravenous therapy, drains), and emotional support. Some emotional support may be obtained by arranging for a visit from a member of an organization such as Reach to Recovery. The woman is reminded that when she awakens after surgery, her arm on the affected side will feel tight.

Immediate Postoperative Care

After recovery from anesthesia, the woman is returned to her room. Special precautions must be observed to prevent or to minimize lymphedema of the affected arm.

The affected arm is elevated with pillows above the level of the right atrium. Blood is not drawn from this arm, and this arm is not used for intravenous therapy or any injections. Early arm movement is encouraged. Any increase in the circumference of that arm is reported immediately.

Nursing care of the wound involves observation for signs of hemorrhage (dressing, drainage tubes, and Hemovac or Jackson-Pratt drainage reservoirs are emptied at least every 8 hours and more frequently as needed), shock, and infection. Dressings are reinforced as necessary. The woman is asked to turn (alternating between unaffected side and back), cough (while the nurse or the woman applies support to the chest), and deep breathe every 2 hours. Breath sounds are auscultated every 4 hours. Active range of motion (ROM) exercise of legs is encouraged. Parenteral fluids are given until adequate oral intake is possible. Emotional support is continued.

Care given during the immediate postoperative period is continued as necessary. Most women who undergo lumpectomy have surgery as ambulatory clients and return home a few hours after surgery. Women are discharged 24 hours or less after mastectomy without reconstruction. Women having a mastectomy with tissue expander placement will be in the hospital for 24 hours. Those having flap reconstruction at the same time will be hospitalized for 3 to 5 days. Because of the generally short time spent in the hospital, thorough teaching is important. It is best to do as much teaching as possible before surgery if the outcome is known. If this is not possible, discharge teaching should be done with the woman’s caregiver present. This is to acknowledge the possibility that emotional stress or recovery from anesthesia may cause the woman to forget some of the discharge instructions. Printed information also should be provided for the woman and family to refer to at home. She will also need information about being fitted for a permanent

breast prosthesis 6 to 7 weeks after surgery; this fitting should be done by a certified prosthesis fitter. A prescription will be needed specifying the anatomic side and to include mastectomy bras as part of the fitting process.