Postpartum Physiology

• Describe the anatomic and physiologic changes that occur during the postpartum period.

• Identify characteristics of uterine involution and lochial flow and describe ways to measure them.

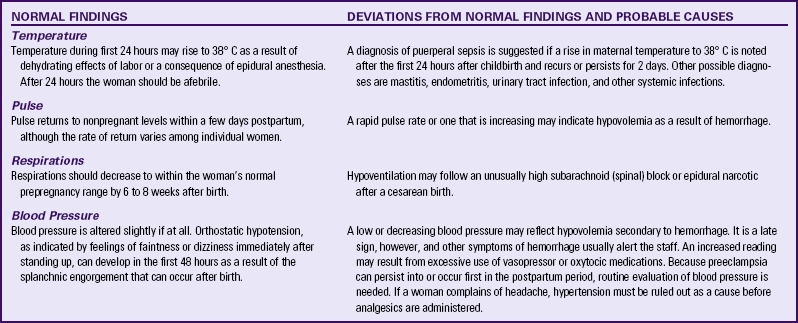

• List expected values for vital signs, deviations from normal findings, and probable causes of the deviations.

The postpartum period is the interval between the birth of the newborn and the return of the reproductive organs to their normal nonpregnant state. This period is sometimes known as the puerperium, or fourth trimester of pregnancy. Although the puerperium has traditionally been considered to last 6 weeks, this time frame varies among women. The distinct physiologic changes that occur as the processes of pregnancy are reversed are normal. To provide care during the recovery period that is beneficial to the mother, her infant, and her family, the nurse must synthesize knowledge of maternal anatomy and physiology, the newborn’s physical and behavioral characteristics, infant care activities, and the family response to the birth of the child. This chapter focuses on anatomic and physiologic changes that occur in the woman during the postpartum period.

Reproductive System and Associated Structures

Involution Process

The return of the uterus to a nonpregnant state after birth is known as involution. This process begins immediately after expulsion of the placenta with contraction of the uterine smooth muscle.

At the end of the third stage of labor, the uterus is in the midline, approximately 2 cm below the level of the umbilicus, with the fundus resting on the sacral promontory. At this time the uterus weighs approximately 1000 g (Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, Hauth, Rouse, & Spong, 2010).

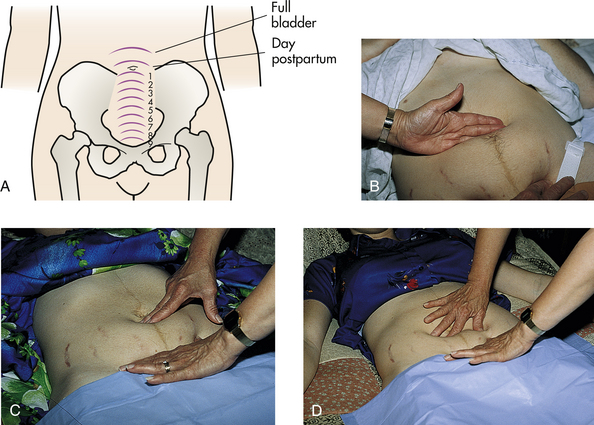

Within 12 hours the fundus rises to approximately the level of the umbilicus (Fig. 20-1). The fundus descends 1 to 2 cm every 24 hours. By 1 week after birth the fundus is normally located halfway between the umbilicus and the symphysis pubis. The uterus should not be palpable abdominally after 2 weeks and should have returned to its nonpregnant location by 6 weeks after birth (Blackburn, 2007).

FIG. 20-1 Assessment of involution of uterus after childbirth. A, Normal progress, days 1 through 9. B, Size and position of uterus 2 hours after childbirth. C, Two days after childbirth. D, Four days after childbirth. (B, C, and D, Courtesy Marjorie Pyle, RNC, Lifecircle, Costa Mesa, CA.)

The uterus, which at full term weighs approximately 11 times its prepregnancy weight, involutes to approximately 500 g by 1 week after birth and to 350 g by 2 weeks after birth. At 6 weeks postpartum, it weighs 60 to 80 g.

Increased estrogen and progesterone levels are responsible for stimulating the massive growth of the uterus during pregnancy. Prenatal uterine growth results from both hyperplasia, an increase in the number of muscle cells, and hypertrophy, enlargement of the existing cells. Postpartally the decrease in the secretion of these hormones causes autolysis, the self-destruction of excess hypertrophied tissue. The additional cells laid down during pregnancy remain, however, and account for the slight increase in uterine size after each pregnancy.

Subinvolution is the failure of the uterus to return to a nonpregnant state. The most common causes of subinvolution are retained placental fragments and infection (see Chapter 34).

Contractions

Postpartum hemostasis is achieved primarily by compression of intramyometrial blood vessels as the uterine muscle contracts, rather than by platelet aggregation and clot formation. The hormone oxytocin, released from the posterior pituitary gland, strengthens and coordinates these uterine contractions, which compress blood vessels and promote hemostasis. During the first 1 to 2 postpartum hours, uterine contractions may decrease in intensity and become uncoordinated. Because the uterus must remain firm and well contracted, exogenous oxytocin (Pitocin) is usually administered intravenously or intramuscularly immediately after expulsion of the placenta. Women who plan to breastfeed can be encouraged to put the baby to her breast immediately after birth because suckling stimulates oxytocin release.

Afterpains

In first-time mothers, uterine tone is good, the fundus generally remains firm, and the woman usually perceives only mild uterine cramping. Periodic relaxation and vigorous contraction are more common in subsequent pregnancies and may cause uncomfortable cramping called afterpains (afterbirth pains) that persist throughout the early puerperium. Afterpains are more noticeable after births in which the uterus was overdistended (e.g., large baby, multifetal gestation, polyhydramnios). Breastfeeding and exogenous oxytocic medication usually intensify these afterpains, because both stimulate uterine contractions.

Placental Site

Immediately after the placenta and membranes are expelled, vascular constriction and thromboses reduce the placental site to an irregular nodular and elevated area. Upward growth of the endometrium causes sloughing of necrotic tissue and prevents the scar formation that is characteristic of normal wound healing. This unique healing process enables the endometrium to resume its usual cycle of changes and to permit implantation and placentation in future pregnancies. Endometrial regeneration is completed by postpartum day 16, except at the placental site. Regeneration at the placental site occurs gradually and is not usually complete until 6 weeks after birth (Blackburn, 2007).

Lochia

Uterine discharge after childbirth, commonly called lochia, is initially bright red (lochia rubra) and may contain small clots. For the first 2 hours after birth the amount of uterine discharge should be approximately that of a heavy menstrual period. After that time the lochial flow should steadily decrease.

Lochia rubra consists mainly of blood and decidual and trophoblastic debris. The flow pales, becoming pink or brown (lochia serosa) after 3 to 4 days. Lochia serosa consists of old blood, serum, leukocytes, and tissue debris. The median duration of lochia serosa discharge is 22 to 27 days (Katz, 2007). In most women, approximately 10 days after childbirth the drainage becomes yellow to white (lochia alba). Lochia alba consists primarily of leukocytes and decidual cells but also contains epithelial cells, mucus, serum, and bacteria. Lochia alba usually continues for 10 to 14 days but may last longer and still be normal. Thus lochia persists up to 4 to 8 weeks after birth (Cunningham et al., 2010).

If the woman receives an oxytocic medication, regardless of the route of administration, the flow of lochia is often scant until the effects of the medication wear off. The amount of lochia typically is less after cesarean births because the surgeon suctions the blood and fluids from the uterus or wipes the uterine lining before closing the incision. Flow of lochia usually increases with ambulation and breastfeeding. Lochia tends to pool in the vagina when the woman is lying in bed; on standing, the woman may experience a gush of blood. This gush should not be confused with hemorrhage.

Persistence of lochia rubra early in the postpartum period suggests continued bleeding as a result of retained fragments of the placenta or membranes. Recurrence of bleeding approximately 7 to 14 days after birth is from the healing placental site. Approximately 10% to 15% of women will still be experiencing normal lochia serosa discharge at their 6-week postpartum examination (Katz, 2007). In the majority of women, however, a continued flow of lochia serosa or lochia alba by 3 to 4 weeks after birth may indicate endometritis, particularly if fever, pain, or abdominal tenderness is associated with the discharge. Lochia should smell like normal menstrual flow; an offensive odor usually indicates infection.

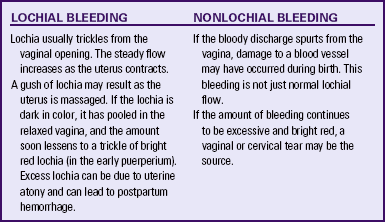

Not all postpartal bleeding is lochia; bleeding after birth may be a result of unrepaired vaginal or cervical lacerations or uterine atony (see Chapter 34). Table 20-1 distinguishes between lochial and nonlochial bleeding.

Cervix

The cervix is soft immediately after birth. The ectocervix (portion of the cervix that protrudes into the vagina) appears bruised and has some small lacerations—optimal conditions for the development of infection. Over the next 12 to 18 hours it shortens and becomes firmer. The cervical os, which dilated to 10 cm during labor, closes gradually. Within 2 to 3 days postpartum it has shortened, become firm, and regained its form. The cervix up to the lower uterine segment remains edematous, thin, and fragile for several days after birth. By the second or third postpartum day the cervix is dilated 2 to 3 cm, and by 1 week after birth it is approximately 1 cm dilated (Blackburn, 2007). The external cervical os never regains its prepregnancy appearance; it no longer has a circular shape but appears as a jagged slit often described as a “fish mouth” (see Fig. 13-2). Lactation delays the production of cervical and other estrogen-influenced mucus and mucosal characteristics.

Vagina and Perineum

Postpartum estrogen deprivation is responsible for the thinness of the vaginal mucosa and the absence of rugae. The greatly distended smooth-walled vagina gradually decreases in size and regains tone, although it never completely returns to

its prepregnancy state (Cunningham et al., 2010). Rugae reappear within 3 to 4 weeks, but they are never as prominent as they are in the nulliparous woman. Most rugae are permanently flattened. The hymen remains as small tags of tissue that scar and form the myrtiform caruncles (Cunningham et al.). The mucosa remains atrophic in the lactating woman, at least until menstruation resumes. Thickening of the vaginal mucosa occurs with the return of ovarian function. Estrogen deficiency is also responsible for a decreased amount of vaginal lubrication. Localized dryness and coital discomfort (dyspareunia) may persist until ovarian function returns and menstruation resumes. The use of a water-soluble lubricant during sexual intercourse is usually recommended.

Immediately after birth the introitus is erythematous and edematous, especially in the area of the episiotomy or laceration repair. It is usually barely distinguishable from that of a nulliparous woman if lacerations and an episiotomy have been carefully repaired, hematomas are prevented or treated early, and the woman observes good hygiene during the first 2 weeks after birth.

Most episiotomies and laceration repairs are visible only if the woman is lying on her side with her upper buttock raised or if she is placed in the lithotomy position. A good light source is essential for visualization of some repairs. Healing of an episiotomy or laceration is the same as that of any surgical incision. Signs of infection (pain, redness, warmth, swelling, or discharge) or the loss of approximation (separation of the incision edges) may occur. Initial healing occurs within 2 to 3 weeks, but 4 to 6 months can be required for the repair to heal completely (Blackburn, 2007).

Hemorrhoids (anal varicosities) are commonly seen (see Fig. 13-10). Internal hemorrhoids can evert while the woman is pushing during birth. Women often experience associated symptoms such as itching, discomfort, and bright red bleeding with defecation. Hemorrhoids usually decrease in size within 6 weeks of childbirth.

Pelvic Muscular Support

The supporting structure of the uterus and vagina may be injured during childbirth and contributes to later gynecologic problems. Supportive tissues of the pelvic floor that are torn or stretched during childbirth may require up to 6 months to regain tone. Kegel exercises, which help to strengthen perineal muscles and encourage healing, are recommended after childbirth (see the Teaching for Self-Management box, p. 91). Later in life, women can experience pelvic relaxation, the lengthening and weakening of the fascial supports of pelvic structures. These structures include the uterus, the upper posterior vaginal wall, the urethra, the bladder, and the rectum. Although pelvic relaxation can occur in any woman, it is usually a direct but delayed complication of childbirth (see Chapter 11).

Endocrine System

Significant hormonal changes occur during the postpartal period. Expulsion of the placenta results in dramatic decreases of the hormones produced by that organ. Decreases in human chorionic somatomammotropin, estrogens, cortisol, and the placental enzyme insulinase reverse the diabetogenic effects of pregnancy, resulting in significantly lower blood sugar levels in the immediate puerperium. For several days after birth, mothers with type 1 diabetes will likely require much less insulin than they did at the end of pregnancy. Because these normal hormonal changes make the puerperium a transitional period for carbohydrate metabolism, interpreting glucose tolerance tests is difficult at this time.

Estrogen and progesterone levels decrease markedly after expulsion of the placenta and reach their lowest levels 1 week after childbirth. Decreased estrogen levels are associated with breast engorgement and with the diuresis of excess extracellular fluid accumulated during pregnancy. In nonlactating women, estrogen levels begin to rise by 2 weeks after birth and by postpartum day 17 are higher than in women who breastfeed (Katz, 2007).

Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) disappears fairly quickly from maternal circulation. However, because removing hCG from the extravascular and intracellular spaces takes additional time, the hormone can be detected in the maternal system for 3 to 4 weeks after birth (Blackburn, 2007).

Pituitary Hormones and Ovarian Function

Lactating and nonlactating women differ considerably in the time when the first ovulation occurs and when menstruation resumes. The persistence of elevated serum prolactin levels in breastfeeding women appears to be responsible for suppressing ovulation (Katz, 2007). Prolactin levels in blood rise progressively throughout pregnancy and remain elevated in women who breastfeed (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2009). The duration of anovulation is influenced by the frequency of breastfeeding, the duration of each feeding, and the degree to which supplementary feedings are used (Katz). Individual differences in the strength of an infant’s sucking stimulus probably also affect prolactin levels. In women who breastfeed, the mean length of time to initial ovulation is approximately 6 months (Blackburn, 2007; Katz).

In nonlactating women, prolactin levels decline after birth and reach the prepregnant range by the third postpartum week (Katz, 2007). Ovulation occurs as early as 27 days after birth in nonlactating women, with a mean time of approximately 70 to 75 days. Menstruation usually resumes by 4 to 6 weeks postpartum after childbirth. Some women ovulate before their first postpartum menstrual period occurs; therefore, contraceptive options should be discussed early in the puerperium (Blackburn, 2007; Cunningham et al., 2010).

The first menstrual flow after childbirth is usually heavier than usual. Within three or four cycles, the amount of menstrual flow returns to the woman’s prepregnancy volume.

Abdomen

When the woman stands up during the first days after birth, her abdomen protrudes and gives her a still-pregnant appearance. During the first 2 weeks after birth the abdominal wall is relaxed. Approximately 6 weeks are required for the abdominal wall to approximate its prepregnancy state (Fig. 20-2). The skin regains most of its previous elasticity, but some striae may persist. The return of muscle tone depends on previous tone, proper exercise, and the amount of adipose tissue present. Occasionally, with or without overdistention because of a large fetus or multiple fetuses, the abdominal wall muscles separate, a condition termed diastasis recti abdominis (see Fig. 13-13b). Persistence of this defect may be disturbing to the woman, but surgical correction is rarely necessary. With time, the defect becomes less apparent.

Urinary System

The hormonal changes of pregnancy (i.e., high steroid levels) contribute to an increase in renal function; diminishing steroid levels after birth may partly explain the reduced renal function that occurs during the puerperium. Kidney function returns to normal within 1 month after birth. From 2 to 8 weeks are required for the pregnancy-induced hypotonia and dilation of the ureters and renal pelves to return to the nonpregnant state (Cunningham et al., 2010). In a small percentage of women, dilation of the urinary tract can persist for 3 months, which increases the chance of developing a urinary tract infection.

Urine Components

The renal glycosuria induced by pregnancy disappears by 1 week postpartum (Blackburn, 2007), but lactosuria can occur in lactating women. The blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level increases during the puerperium as autolysis of the involuting uterus occurs. This breakdown of excess protein in the uterine muscle cells also contributes to pregnancy-associated proteinuria, which resolves by 6 weeks after birth. The BUN returns to a nonpregnant level by 2 to 3 months after childbirth (Blackburn). Ketonuria can occur in women with an uncomplicated birth or after a prolonged labor with dehydration.

Postpartal Diuresis

Within 12 hours of birth, women begin to lose the excess tissue fluid accumulated during pregnancy. Profuse diaphoresis often occurs, especially at night, for the first 2 or 3 days after childbirth. Postpartal diuresis, caused by decreased estrogen levels, removal of increased venous pressure in the lower extremities, and loss of the remaining pregnancy-induced increase in blood volume, also aids the body in ridding itself of excess fluid. Fluid loss through perspiration and increased urinary output accounts for a weight loss of approximately 2.25 kg during the early puerperium.

Urethra and Bladder

Birth-induced trauma, increased bladder capacity after childbirth, and the effects of conduction anesthesia combine to cause a decreased urge to void. In addition, pelvic soreness caused by the forces of labor, vaginal lacerations, or an episiotomy reduces or alters the voiding reflex. Decreased voiding, combined with postpartal diuresis, can result in bladder distention.

Immediately after birth excessive bleeding can occur if the bladder becomes distended because it pushes the uterus up and to the side and prevents it from contracting firmly. Later in the puerperium overdistention can make the bladder increasingly susceptible to infection and impede the resumption of normal voiding (Cunningham et al., 2010). With adequate emptying of the bladder, bladder tone is usually restored 5 to 7 days after childbirth.

Gastrointestinal System

The mother is usually hungry shortly after giving birth and can tolerate a light diet. Most new mothers are very hungry after full recovery from analgesia, anesthesia, and fatigue. Requests for extra portions of food and frequent snacks are common.

Bowel Evacuation

A spontaneous bowel evacuation may not occur for 2 to 3 days after childbirth. This delay can be explained by decreased muscle tone in the intestines during labor and the immediate puerperium, prelabor diarrhea, lack of food, or dehydration. The mother often anticipates discomfort during the bowel movement because of perineal tenderness as a result of an episiotomy, lacerations, or hemorrhoids and resists the urge to defecate. Regular bowel habits should be reestablished when bowel tone returns.

Operative vaginal birth (forceps use) and anal sphincter lacerations are associated with an increased risk of postpartum anal incontinence. Women with this problem are more often incontinent of flatus than of stool. If anal incontinence lasts more than 6 months, studies should be conducted to determine the specific cause and appropriate treatment (Katz, 2007).

Breasts

Promptly after birth a decrease occurs in the concentrations of hormones (i.e., estrogen, progesterone, hCG, prolactin, cortisol, and insulin) that stimulated breast development during pregnancy. The time required for these hormones to return to prepregnancy levels is determined in part by whether the mother breastfeeds her infant.

Breastfeeding Mothers

During the first 24 hours after birth, little if any change occurs in the breast tissue. Colostrum or early milk, a clear yellow fluid, may be expressed from the breasts. The breasts gradually become fuller and heavier as the colostrum transitions to mature milk by approximately 72 to 96 hours after birth; this breast change is often referred to as the “milk coming in.” The breasts may feel warm, firm, and somewhat tender. Bluish-white milk with a skim-milk appearance (mature milk) can be expressed from the nipples. As milk glands and milk ducts fill with milk, breast tissue may feel somewhat nodular or lumpy. Unlike the lumps associated with fibrocystic breast disease or cancer (which may be palpated consistently in the same location), the nodularity associated with milk production tends to shift in position. Some women experience engorgement, but with frequent breastfeeding and proper care, this condition is temporary and typically lasts only 24 to 48 hours (see Chapter 25).

Nonbreastfeeding Mothers

The breasts generally feel nodular in contrast to the granular feel of breasts in nonpregnant women. The nodularity is bilateral and diffuse. Prolactin levels drop rapidly. Colostrum is present for the first few days after childbirth. Palpation of the breasts on the second or third day, as milk production begins, may reveal tissue tenderness in some women. On the third or fourth postpartum day, engorgement may occur. The breasts are distended (swollen), firm, tender, and warm to the touch (because of vasocongestion). Breast distention is caused primarily by the temporary congestion of veins and lymphatics rather than by an accumulation of milk. Milk is present but should not be expressed. Axillary breast tissue (the tail of Spence) and any accessory breast or nipple tissue along the milk line may be involved. Engorgement resolves spontaneously, and discomfort usually decreases within 24 to 36 hours. A breast binder or well-fitted, supportive bra, ice packs, fresh cabbage leaves (see Fig. 25-15), and mild analgesics may be used to relieve discomfort. Nipple stimulation is avoided. If suckling or expression of milk (pumping) is never begun (or is discontinued), lactation ceases within a few days to a week.

Cardiovascular System

Changes in blood volume after birth depend on several factors, such as blood loss during childbirth and the amount of extravascular water (physiologic edema) mobilized and excreted. Pregnancy-induced hypervolemia (an increase in blood volume of at least 35% more than prepregnancy values near term) allows most women to tolerate considerable blood loss during childbirth. The average blood loss for a vaginal birth of a single fetus ranges from 300 ml to 500 ml (10% of blood volume). The typical blood loss for women who give birth by cesarean is 500 ml to 1000 ml (15% to 30% of blood volume). During the first few days after birth the plasma volume decreases further as a result of diuresis (Blackburn, 2007).

The woman’s response to blood loss during the early puerperium differs from that in a nonpregnant woman. Three postpartum physiologic changes protect the woman by increasing the circulating blood volume: (1) elimination of uteroplacental circulation reduces the size of the maternal vascular bed by 10% to 15%, (2) loss of placental endocrine function removes the stimulus for vasodilation, and (3) mobilization of extravascular water stored during pregnancy occurs. By the third postpartum day the plasma volume has been replenished as extravascular fluid returns to the intravascular space (Katz, 2007).

Cardiac Output

Pulse rate, stroke volume, and cardiac output increase throughout pregnancy. Cardiac output remains increased for at least the first 48 hours postpartum because of an increase in stroke volume. This increased stroke volume is caused by the return of blood to the maternal systemic venous circulation, a result of a rapid decrease in uterine blood flow and mobilization of extravascular fluid (Blackburn, 2007). Cardiac output decreases by 30% by 2 weeks after childbirth and then gradually decreases to nonpregnant values by 6 to 12 weeks in most women. Stroke volume, end diastolic volume, cardiac output, and systemic vascular resistance remain elevated in some women over nonpregnant values for up to 12 weeks or longer (Blackburn).

Vital Signs

Few alterations in vital signs are seen under normal circumstances. Heart rate and blood pressure return to nonpregnant levels within a few days (Katz, 2007) (Table 20-2). Respiratory function rapidly returns to nonpregnant levels after birth (Blackburn, 2007). After the uterus is emptied, the diaphragm descends, the normal cardiac axis is restored, and the point of maximal impulse and the electrocardiogram are normalized.

Blood Components

After childbirth the total blood volume decreases by approximately 16% from its prebirth value, resulting in a transient anemia. After 8 weeks, however, the number of red blood cells has increased and the majority of women have a normal hematocrit (Katz, 2007).

White Blood Cell Count

Normal leukocytosis of pregnancy averages approximately 12,000/mm3. During the first 10 to 12 days after childbirth, values between 20,000 and 25,000/mm3 are common. Neutrophils are the most numerous white blood cells. Leukocytosis, coupled with the normal increase in erythrocyte sedimentation rate, can obscure the diagnosis of acute infection at this time.

Coagulation Factors

Clotting factors and fibrinogen are normally increased during pregnancy and remain elevated in the immediate puerperium. When combined with vessel damage and immobility, this hypercoagulable state causes an increased risk of thromboembolism, especially after a cesarean birth. Fibrinolytic activity also increases during the first few days after childbirth (Katz, 2007). Factors I, II, VII, VIII, IX, and X decrease to nonpregnant levels within a few days. Fibrin split products, probably released from the placental site, also can be found in maternal blood.

Varicosities

Varicosities (varices) of the legs (Fig. 20-3) and around the anus (hemorrhoids) are common during pregnancy. Varices, even the less common vulvar varices, regress (empty) rapidly immediately after childbirth. Surgical repair of varicosities is not considered during pregnancy. Total or nearly total regression of varicosities is expected after childbirth.

Neurologic System

Neurologic changes during the puerperium are those that result from a reversal of maternal adaptations to pregnancy and those resulting from trauma during labor and childbirth.

Pregnancy-induced neurologic discomforts disappear after birth. Elimination of physiologic edema through the diuresis that follows childbirth relieves carpal tunnel syndrome by easing the compression of the median nerve. The periodic numbness and tingling of fingers that afflict 5% of pregnant women usually disappear after childbirth unless lifting and carrying the baby aggravate the condition. Headache requires careful assessment. Postpartum headaches can be caused by various conditions, including postpartum-onset preeclampsia, stress, and leakage of cerebrospinal fluid into the extradural space during placement of the needle for epidural or spinal anesthesia. Depending on the cause and effectiveness of the treatment, the duration of the headaches can vary from 1 to 3 days to several weeks.

Musculoskeletal System

Adaptations of the mother’s musculoskeletal system that occur during pregnancy are reversed in the puerperium. These adaptations include the relaxation and subsequent hypermobility of the joints and the change in the mother’s center of gravity in response to the enlarging uterus. The joints are completely stabilized by 6 to 8 weeks after birth. Although all other joints return to their normal prepregnancy state, those in the parous woman’s feet do not. The new mother may notice a permanent increase in her shoe size.

Integumentary System

Chloasma (mask) of pregnancy usually disappears at the end of pregnancy. Hyperpigmentation of the areolae and linea nigra may not regress completely after childbirth. Some women will have permanent darker pigmentation of those areas (see Fig. 13-11). Striae gravidarum (stretch marks) on the breasts, the abdomen, the hips, and the thighs may fade but usually do not disappear.

Vascular abnormalities such as spider angiomas (nevi), palmar erythema, and an epulis generally regress in response to the rapid decline in estrogen levels after pregnancy. Spider nevi persist indefinitely in some women.

Hair growth slows during the postpartum period. Some women may actually experience hair loss because the amount of hair lost is temporarily more than the amount regrown. The abundance of fine hair seen during pregnancy usually disappears after birth; however, any coarse or bristly hair that appears during pregnancy usually remains. Fingernails return to their nonpregnant consistency and strength.

Immune System

No significant changes in the maternal immune system occur during the postpartum period. The mother’s need for a rubella, varicella, or tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccination or for prevention of Rh isoimmunization is determined (see Chapter 21).

KEY POINTS

• Uterine involution begins immediately after birth and is complete in approximately 6 weeks.

• The rapid drop in estrogen and progesterone levels after expulsion of the placenta is responsible for triggering many of the anatomic and physiologic changes in the puerperium.

• The return of ovulation and menses is determined in part by whether the woman breastfeeds her infant.

• Assessment of lochia and fundal height is essential to monitor the progress of normal involution and to identify potential problems.

• Under normal circumstances, few alterations in vital signs are seen after childbirth.

• Hypercoagulability, vessel damage, and immobility predispose the woman to thromboembolism.

• Marked diuresis, decreased bladder sensitivity, and overdistention of the bladder can lead to problems with urinary elimination.

• Pregnancy-induced hypervolemia and several postpartum physiologic changes allow the woman to tolerate considerable blood loss at birth.

![]() Audio Chapter Summaries Access an audio summary of the Key Points on

Audio Chapter Summaries Access an audio summary of the Key Points on ![]()