Newborn Nutrition and Feeding

• Describe current recommendations for infant feeding.

• Explain the nurse’s role in helping families choose an infant feeding method.

• Discuss benefits of breastfeeding for infants, mothers, families, and society.

• Describe nutritional needs of infants.

• Describe anatomic and physiologic aspects of breastfeeding.

• Recognize newborn feeding-readiness cues.

• Explain maternal and infant indicators of effective breastfeeding.

• Examine nursing interventions to facilitate and promote successful breastfeeding.

• Analyze common problems associated with breastfeeding and interventions to help resolve them.

• Compare powdered, concentrated, and ready-to-use forms of commercial infant formula.

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/MWHC/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/MWHC/

Audio Glossary

Case Study

Critical Thinking Exercises

Nursing Care Plans

Video—Nursing Skills

Good nutrition in infancy fosters optimal growth and development. Infant feeding is more than the provision of nutrition; it is an opportunity for social, psychologic, and even educational interaction between parent and infant. It can also establish a basis for developing good eating habits that last a lifetime.

Through preconception and prenatal education and counseling, nurses play an instrumental role in assisting parents with the selection of an infant feeding method. Scientific evidence is clear that human milk provides the best nutrition for infants, and parents should be strongly encouraged to choose breastfeeding (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] Section on Breastfeeding, 2005; Ip, Chung, Raman, Chew, Magula, DeVine, et al., 2007). Although many health care providers and the general public consider commercial infant formula to be equivalent to breast milk, this belief is erroneous. Human milk is species-specific, uniquely designed to meet the needs of human infants. The composition of human milk changes to meet the nutritional needs of growing infants. It is highly complex, with antiinfective and nutritional components combined with growth factors, enzymes that aid in digestion and absorption of nutrients, and fatty acids that promote brain growth and development. Infant formulas are usually adequate in providing nutrition to maintain infant growth and development within normal limits, but they are not equivalent to human milk.

Breastfeeding is defined as the transfer of human milk from mother to child; the infant receives milk directly from the mother’s breast. Breast milk feeding is the provision of mother’s milk to the infant; the mother expresses her milk and feeds it to the infant. Human milk feeding refers to feeding of breast milk from another individual or from a milk bank. Exclusive breastfeeding means that the infant is fed no other liquid or solid food (Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine [ABM] Board of Directors, 2008).

Whether the parents choose breastfeeding, breast milk feeding, human milk feeding, or feeding with commercial infant formula, nurses provide support and ongoing education. Parent education is necessarily based on current research findings and standards of practice.

This chapter focuses on meeting nutritional needs for normal growth and development from birth to 6 months, with emphasis on the neonatal period, when feeding practices and patterns are established. Breastfeeding and formula feeding are addressed. Information on breastfeeding is focused on the direct transfer of milk from mother to infant.

Recommended Infant Nutrition

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends exclusive breastfeeding or human milk feeding for the first 6 months of life and that breastfeeding or human milk feeding continue as the sole source of milk for the first year. During the second 6 months of life, appropriate complementary foods (solids) are added to the infant diet. If infants are weaned from breast milk before 12 months of age, they should receive iron-fortified infant formula, not cow’s milk (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2005). According to the Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding, endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), infants should be exclusively breastfed for 6 months, and breastfeeding should continue for up to 2 years and beyond (WHO/UNICEF, 2003).

Exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life is also recommended by other professional health care organizations such as the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) (2007), Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine (ABM Board of Directors, 2008), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) (ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women & Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2007), and the American Dietetic Association (ADA) (2009). The Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) (2007) actively supports breastfeeding as the ideal form of infant nutrition and provides guidelines for nurses in promoting breastfeeding and supporting breastfeeding families.

Breastfeeding Rates

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Immunization Survey (2009) indicate that breastfeeding rates in the United States have risen steadily over the past decade. In 2006, the percent of infants ever breastfed was 73.9%, falling short of the Healthy People 2010 goal of 75%. However, 28 states had breastfeeding initiation rates that met or exceeded the Healthy People goal. The 6-month breastfeeding rate was 43.4% and the 12-month rate was 22.7%. The Healthy People 2010 goals of 50% at 6 months and 25% at 12 months were not achieved. Exclusive breastfeeding rates were 33.1% at 3 months and 13.6% at 6 months; the Healthy People goals were 40% and 17%, respectively (CDC, 2009; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2000).

Among a birth cohort group of 434 infants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (McDowell, Wang, & Kennedy-Stephenson, 2008), the percentage who were ever breastfed rose to a record level of 77% for 2005-2006. This was an increase from 60% among infants born from 1993 to 1994. There were no significant changes in breastfeeding rates at 6 months of age—the highest breastfeeding rates were reported among Mexican-Americans (40%) and non-Hispanic white infants (35%). Breastfeeding initiation rates increased significantly to 65% among non-Hispanic black women. Results of the survey showed that certain breastfeeding trends continue: those most likely to breastfeed are Caucasian, older than age 30, with higher incomes.

The proposed objective for Healthy People 2020 is retained from the 2010 objectives: to “increase the proportion of mothers who breastfeed their babies.” The proposed goals related to breastfeeding rates remain the same as for Healthy People 2010 (USDHHS, 2009).

Benefits of Breastfeeding

Numerous research studies have identified the beneficial effects of human milk for infants during the first year of life. Long-term epidemiologic studies have shown that these benefits do not cease when the infant is weaned; instead, they extend into childhood and beyond. Breastfeeding has many advantages for mothers, for families, and for society in general (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2005; Horta, Bahl, Martines, & Victora, 2007; Ip et al., 2007; Stuebe, 2009). To discuss breastfeeding with parents, nurses and other health care professionals must have a thorough understanding of its benefits from both a physiologic and a psychosocial perspective (Table 25-1).

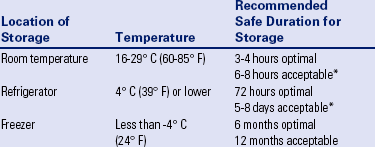

TABLE 25-1

SIDS, Sudden infant death syndrome.

Sources: American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding. (2005). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Policy statement. Pediatrics, 115(23), 496-506; Horta, B., Bahl, R., Martines, J., & Victora, C. (2007). Evidence of the long-term effects of breastfeeding. Geneva: World Health Organization; Ip, S., Chung, M., Raman, G., Chew, P., Magula, N., DeVine, D., et al. (2007). Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evidence report/technology assessment No. 153. (Prepared by Tufts-New England Medical Center Evidence-Based Practice Center under contract No. 290-02-0022). AHRQ publication No. 07-E007. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Stuebe, A. (2009). The risks of not breastfeeding for mothers and infants. Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2(4), 222-231.

Choosing an Infant Feeding Method

Breastfeeding is a natural extension of pregnancy and childbirth; it is much more than simply a means of supplying nutrition for infants. Women most often breastfeed their babies because they are aware of the benefits to the infant. Many women seek the unique bonding experience between mother and infant that is characteristic of breastfeeding. Women tend to select the same method of infant feeding for each of their children. If the first child was breastfed, subsequent children will likely also be breastfed (Taylor, Geller, Risica, Kirtania, & Cabral, 2008).

The support of the partner and family is a major factor in the mother’s decision to breastfeed. Women who perceive their partners to prefer breastfeeding are more likely to choose this method (Scott, Binns, Graham, & Oddy, 2006). Women are more likely to breastfeed successfully when partners and family members are positive about breastfeeding and have the skills to support breastfeeding (Clifford & McIntyre, 2008).

Parents who choose to formula feed often make this decision without complete information and understanding of the benefits of breastfeeding. Even women who are educated about the advantages of breastfeeding may still decide to formula feed. Cultural beliefs, as well as myths and misconceptions about breastfeeding, influence women’s decision making. Many women see bottle feeding as more convenient or less embarrassing than breastfeeding. Some view formula feeding as a way to ensure that the father, other family members, and daycare providers can feed the baby. Some women lack confidence in their ability to produce breast milk of adequate quantity or quality. Women who have had previous unsuccessful breastfeeding experiences may choose to formula feed subsequent infants. Some women see breastfeeding as incompatible with an active social life, or they think that it will prevent them from going back to work. Modesty issues and societal barriers exist against breastfeeding in public. A major barrier for many women is the influence of family and friends.

Breastfeeding is contraindicated in a few situations. Newborns who have galactosemia should not be breastfed. Mothers with active tuberculosis and those who are positive for human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I or type II should not breastfeed.

In the United States, maternal HIV infection is considered a contraindication for breastfeeding (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2005). However, that is not true in other countries. In developing countries where HIV is prevalent, the benefits of breastfeeding for infants outweigh the risk of contracting HIV from infected mothers. In 2010, The World Health Organization (2010) published revised guidelines on HIV and infant feeding. The guidelines indicate that national or sub-national health authorities should decide which feeding practice for HIV-infected mothers will be promoted and supported by Maternal and Child Health services: avoiding all breastfeeding or breastfeeding and receiving antiretroviral (ARV) medications. HIV-infected mothers who are taking ARV therapy should breastfeed until infants are 12 months of age. If ARVs are not available, breastfeeding can improve the chances of HIV-free survival for infants born to HIV-infected mothers. Therefore, for HIV-infected mothers who do not have access to ARVs, exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months is recommended; complementary foods can be introduced thereafter, and breastfeeding should continue until the infant is one year old. Furthermore, breastfeeding should continue until a safe and nutritionally adequate diet without breastmilk can be provided for the infant (WHO, United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF], United Nations Population Fund [UNFPA], & Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS [UNAIDS], 2010).

Breastfeeding is not recommended when mothers are receiving chemotherapy or radioactive isotopes (e.g., with diagnostic procedures). Maternal use of mood-altering drugs (“street drugs”) is incompatible with breastfeeding (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2005). In addition, women who are taking certain medications such as bromocriptine, reserpine, high-dose corticosteroids, or cyclosporine should not breastfeed (WHO, 2009).

Supporting Breastfeeding Mothers

The key to encouraging mothers to breastfeed is education and anticipatory guidance, beginning as early as possible during and even before pregnancy. Each encounter with an expectant mother is an opportunity to educate, dispel myths, clarify misinformation, and address concerns. Prenatal education and preparation for breastfeeding influence feeding decisions, breastfeeding success, and the amount of time that women breastfeed (Rosen, Krueger, Carney, & Graham, 2008). Prenatal preparation ideally includes the father of the baby, partner, or another significant support person, providing information about benefits of breastfeeding and how he or she can participate in infant care and nurturing.

Connecting expectant mothers with women from similar backgrounds who are breastfeeding or have successfully breastfed is often helpful. Nursing mothers’ support groups provide information about breastfeeding along with opportunities for breastfeeding mothers to interact with one another and share concerns (Fig. 25-1). Peer counseling programs, such as those instituted by Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) programs, are beneficial.

FIG. 25-1 Breastfeeding mothers support group with lactation consultant. (Courtesy Shannon Perry, Phoenix, AZ.)

For women with limited access to health care, the postpartum period may provide the first opportunity for education about breastfeeding. Even women who have indicated the desire to formula-feed can benefit from information about the benefits of breastfeeding. Offering these women the chance to try breastfeeding with the assistance of a nurse or lactation consultant may influence a change in infant feeding practices.

Promoting feelings of competence and confidence in the breastfeeding mother and reinforcing the unequaled contribution she is making toward the health and well-being of her infant are the responsibility of the nurse and other health care professionals. Women who are optimistic, with a sense of breastfeeding self-efficacy, and faith in breast milk as the best nutrition for the infant are likely to breastfeed longer (O’Brien, Buikstra, & Hegney, 2008). The most common reasons for breastfeeding cessation are insufficient milk supply, painful nipples, and problems getting the infant to feed (Lewallen, Dick, Flowers, Powell, Zickefoose, Wall, et al., 2006). Early and ongoing assistance and support from health care professionals to prevent and address problems with breastfeeding can help promote a successful and satisfying breastfeeding experience for mothers and infants (Renfrew & Hall, 2008). Many health care agencies have certified lactation consultants on staff. These health care professionals, who are usually nurses, have specialized training and experience in assisting breastfeeding mothers and infants. Evidence-based guidelines for supporting breastfeeding are available for use by health care professionals (AWHONN, 2007; International Lactation Consultant Association [ILCA], 1999; Overfield, Ryan, Spangler, & Tully, 2005).

All parents are entitled to a birthing environment in which breastfeeding is promoted and supported. The Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), sponsored by the WHO and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), was founded in 1991 to encourage institutions to offer optimal levels of care for lactating mothers. When a hospital achieves the “Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding for Hospitals,” it is recognized as a Baby Friendly Hospital (Box 25-1) (BFHI USA, 2010).

Cultural Influences on Infant Feeding

Cultural beliefs and practices are significant influences on infant feeding methods. Although recognized cultural norms exist, one cannot assume that generalized observations about any cultural group hold true for all members of that group. Many regional and ethnic cultures are found within the United States. Dealing effectively with these groups requires that nurses are knowledgeable and sensitive to the cultural factors influencing infant feeding practices.

In general, people who have immigrated to the United States from poorer countries often choose to formula feed their infants because they believe it is a better, more “modern” method or because they want to adapt to U.S. culture and perceive that formula feeding is the custom. However, this notion is not always true. For example, Hispanic women born in the United States are less likely to breastfeed, whereas those women who have recently immigrated tend to choose the social norm of breastfeeding that is characteristic of their homeland (Gill, 2009). Women from Mexico are accustomed to breastfeeding as the expected method of infant feeding. Mexico has federal guidelines that support breastfeeding and include standards to promote and protect exclusive breastfeeding. Federal regulations in Mexico restrict commercial infant formula distribution in hospitals (Castrucci, Piña Carrizales, D’Angelo, McDonald, Foulkes, Ahluwalia, et al., 2008).

Breastfeeding beliefs and practices vary across cultures. For example, among the Muslim culture, breastfeeding for 24 months is customary. Before the first feeding, rubbing a small piece of softened date on the newborn’s palate is a ritual practice. Because of the cultural emphasis on privacy and modesty, Muslim women may choose to bottle-feed formula or expressed breast milk while in the hospital (Shaikh & Ahmed, 2006).

Because of beliefs about the harmful nature or inadequacy of colostrum, some cultures apply restrictions on breastfeeding for a period of days after birth. Such is the case for many cultures in Southern Asia, the Pacific Islands, and parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Before the mother’s milk is deemed to be “in,” babies are fed prelacteal food such as honey or clarified butter, in the belief that these substances will help clear out meconium (Laroia & Sharma, 2006; Shaikh & Ahmed, 2006). Other cultures begin breastfeeding immediately and offer the breast each time the infant cries.

A common practice among Mexican women is los dos. This refers to combining breastfeeding and commercial infant formula. It is based on the belief that by combining the two methods, the mother and infant receive the benefits of breastfeeding, and the infant also receives the additional vitamins from infant formula (Rios, 2009). This practice can result in problems with milk supply and babies refusing to latch on to the breast, which can lead to early termination of breastfeeding (Bunik, Clark, Zimmer, Jimenez, O’Connor, Crane et al., 2006).

Some cultures have specific beliefs and practices related to the mother’s intake of foods that foster milk production. Korean mothers often eat seaweed soup and rice to enhance milk production. Hmong women believe that boiled chicken, rice, and hot water are the only appropriate nourishments during the first postpartum month. The balance between energy forces, hot and cold, or yin and yang is integral to the diet of the lactating mother. Hispanics, Vietnamese, Chinese, East Indians, and Arabs often use this belief in choosing foods. “Hot” foods are considered best for new mothers. This belief does not necessarily relate to the temperature or spiciness of foods. For example, chicken and broccoli are considered “hot,” whereas many fresh fruits and vegetables are considered “cold.” Families often bring desired foods into the health care setting.

Nutrient Needs

During the first 2 days of life the fluid requirement for healthy infants (more than 1500 g) is 60 to 80 ml of water per kilogram of body weight per day. From day 3 to 7 the requirement is 100 to 150 ml/kg/day and from day 8 to day 30, 120 to 180 ml/kg/day (Dell & Davis, 2006). In general, neither breastfed nor formula-fed infants need to be given water, not even those living in very hot climates. Breast milk contains 87% water, which easily meets fluid requirements. Feeding water to infants may only decrease caloric consumption at a time when they are growing rapidly.

Infants have room for little fluctuation in fluid balance and should be monitored closely for fluid intake and water loss. They lose water through excretion of urine and insensibly through respiration. Under normal circumstances, they are born with some fluid reserve, and some of the weight loss during the first few days is related to fluid loss. In some cases, however, they do not have this fluid reserve, possibly because of inadequate maternal hydration during labor or birth.

Energy

Infants require adequate caloric intake to provide energy for growth, digestion, physical activity, and maintenance of organ metabolic function. Energy needs vary according to age, maturity level, thermal environment, growth rate, health status, and activity level. For the first 3 months the infant needs 110 kcal/kg/day. From 3 months to 6 months the requirement is 100 kcal/kg/day. This level decreases slightly to 95 kcal/kg/day from 6 to 9 months and increases to 100 kcal/kg/day from 9 months to 1 year (AAP, 2008).

Human milk provides 67 kcal/100 ml or 20 kcal/oz. The fat portion of the milk provides the greatest amount of energy. Infant formulas simulate the caloric content of human milk. Usually a standard formula contains 20 kcal/oz, though the composition differs among brands.

Carbohydrate

According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2005), the adequate dietary reference intake (DRI) for carbohydrate in the first 6 months of life is 60 g/day and 95 g/day for the second 6 months. Because newborns have only small hepatic glycogen stores, carbohydrates should provide at least 40% to 50% of the total calories in the diet. Moreover, newborns may have a limited ability to carry out gluconeogenesis (the formation of glucose from amino acids and other substrates) and ketogenesis (the formation of ketone bodies from fat), the mechanisms that provide alternative sources of energy.

As the primary carbohydrate in human milk and commercially prepared infant formula, lactose is the most abundant carbohydrate in the diet of infants up to age 6 months. Lactose provides calories in an easily available form. Its slow breakdown and absorption also increase calcium absorption. Corn syrup solids or glucose polymers are added to infant formulas to supplement the lactose in the cow’s milk and thereby provide sufficient carbohydrates.

Oligosaccharides, another form of carbohydrate found in breast milk, are critical in the development of microflora in the intestinal tract of the newborn. These prebiotics promote an acidic environment in the intestines, preventing the growth of gram-negative and other pathogenic bacteria, thus increasing the infant’s resistance to gastrointestinal (GI) illness.

Fat

The average recommended DRI of fat for infants younger than 6 months is 31 g/day (IOM, 2005). For infants to acquire adequate calories from human milk or formula, at least 15% of the calories provided must come from fat (triglycerides).

The fat content of human milk is composed of lipids, triglycerides, and cholesterol; cholesterol is an essential element for brain growth. Human milk contains the essential fatty acids (EFAs), linoleic acid, and linolenic acid, as well as the long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, arachidonic acid (ARA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Fatty acids are important for growth, neurologic development, and visual function. Cow’s milk contains fewer of the EFAs and no polyunsaturated fatty acids. Most formula companies add DHA and ARA to their products. Studies of infants receiving supplements of DHA and ARA have shown inconclusive results in terms of visual acuity and cognitive function (Heird, 2007; Simmer, Patole, & Rao, 2008).

Modified cow’s milk is used in most infant formulas, but the milk fat is removed, and another fat source such as corn oil, which the infant can digest and absorb, is added in its place. If whole milk or evaporated milk without added carbohydrate is fed to infants, the resulting fecal loss of fat (and therefore loss of energy) can be excessive because the milk moves through the infant’s intestines too quickly for adequate absorption to take place. This can lead to poor weight gain.

Protein

High-quality protein from breast milk, infant formula, or other complementary foods is necessary for infant growth. The protein requirement per unit of body weight is greater in the newborn than at any other time of life. For infants younger than 6 months the average DRI for protein is 9.1 g/day (IOM, 2005).

Human milk contains the two proteins, whey (lactalbumin) and casein (curd), in a ratio of approximately 60:40, as compared with the ratio of 80:20 in most cow’s milk–based formula. This whey/casein ratio in human milk makes it more easily digested and produces the soft stools seen in breastfed infants. The whey protein lactoferrin in human milk has iron-binding capabilities and bacteriostatic properties, particularly against gram-positive and gram-negative aerobes, anaerobes, and yeasts. The casein in human milk enhances the absorption of iron, thus preventing iron-dependent bacteria from proliferating in the GI tract (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2005).

The amino acid components of human milk are uniquely suited to the newborn’s metabolic capabilities. For example, cystine and taurine levels are high, whereas phenylalanine and methionine levels are low.

Vitamins

Human milk contains all of the vitamins required for infant nutrition, with individual variations based on maternal diet and genetic differences. Vitamins are added to cow’s-milk formulas to resemble levels found in breast milk. Although cow’s milk contains adequate amounts of vitamin A and vitamin B complex, vitamin C (ascorbic acid), vitamin E, and vitamin D must be added.

Vitamin D facilitates intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorus, bone mineralization, and calcium resorption from bone. According to the AAP, all infants who are breastfed or partially breastfed should receive 400 International Units of vitamin D daily, beginning the first few days of life. Nonbreastfeeding infants and older children who consume less than 1 quart per day of vitamin D–fortified milk should also receive 400 International Units of vitamin D each day (Wagner, Grier, & AAP Section on Breastfeeding, & Committee on Nutrition, 2008).

Vitamin K, required for blood coagulation, is produced by intestinal bacteria. However, the gut is sterile at birth, and a few days are required for intestinal flora to become established and produce vitamin K. To prevent hemorrhagic problems in the newborn an injection of vitamin K is given at birth to all newborns, regardless of feeding method (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2005).

The breastfed infant’s vitamin B12 intake is dependent on the mother’s dietary intake and stores. Mothers who are on strict vegetarian (vegan) diets and those who consume few dairy products, eggs, or meat are at risk of vitamin B12 deficiency. Breastfed infants of vegan mothers should be supplemented with vitamin B12 from birth.

Minerals

The mineral content of commercial infant formula is designed to reflect that of breast milk. Unmodified cow’s milk is much higher in mineral content than human milk, which also makes it unsuitable for infants during the first year of life. Minerals are typically highest in human milk during the first few days after birth and decrease slightly throughout lactation.

The ratio of calcium to phosphorus in human milk is 2:1, an optimal proportion for bone mineralization. Although cow’s milk is high in calcium, the calcium/phosphorus ratio is low, resulting in decreased calcium absorption. Consequently, young infants fed unmodified cow’s milk are at risk for hypocalcemia, seizures, and tetany. The calcium/phosphorus ratio in commercial infant formula is between that of human milk and cow’s milk. The average DRI for calcium is 210 mg/day for infants younger than 6 months and 270 mg/day for infants between 7 months and 1 year (IOM, 2005).

Iron levels are low in all types of milk; however, iron from human milk is better absorbed than iron from cow’s milk, iron-fortified formula, or infant cereals. Breastfed infants draw on iron reserves deposited in utero and benefit from the high lactose and vitamin C levels in human milk that facilitate iron absorption. The infant who is entirely breastfed usually maintains adequate hemoglobin levels for the first 6 months. After that time, iron-fortified cereals and other iron-rich foods are added to the diet. Infants who are weaned from the breast before 6 months of age and all formula-fed infants should receive an iron-fortified commercial infant formula until 12 months of age. Infants should not be fed low-iron formula (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2005).

Fluoride levels in human milk and commercial formulas are low. This mineral, which is important in preventing dental caries, can cause spotting of the permanent teeth (fluorosis) in excess amounts. Experts recommend that no fluoride supplements be given to infants younger than 6 months. From 6 months to 3 years, fluoride supplements are based on the concentration of fluoride in the water supply (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2005).

Anatomy and Physiology of Lactation

Anatomy of the Lactating Breast

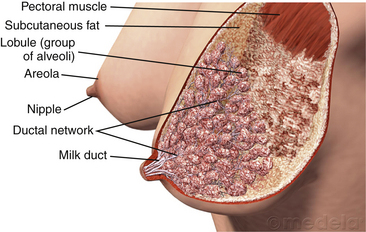

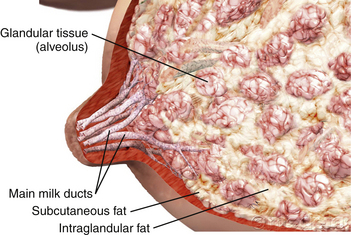

Each female breast is composed of approximately 15 to 20 segments (lobes) embedded in fat and connective tissues and well supplied with blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves (Fig. 25-2). Within each lobe is glandular tissue consisting of alveoli, the milk-producing cells, surrounded by myoepithelial cells that contract to send the milk forward to the nipple during milk ejection. Each nipple has multiple pores that transfer milk to the suckling infant. The ratio of glandular tissue to adipose tissue in the lactating breast is approximately 2:1 compared with a 1:1 ratio in the nonlactating breast. Within each breast is a complex, intertwining network of milk ducts that transport milk from the alveoli to the nipple. The milk ducts dilate and expand at milk ejection. Previous thinking held that the milk ducts converged behind the nipple in lactiferous sinuses, which acted as reservoirs for milk. However, research based on ultrasonography of lactating breasts has shown that these sinuses do not exist, and in fact glandular tissue can be found directly beneath the nipple (Geddes, 2007; Ramsay, Kent, Hartmann, & Hartmann, 2005) (Fig. 25-3).

The size and shape of the breast are not accurate indicators of its ability to produce milk. Although nearly every woman can lactate, a small number have insufficient mammary gland development to breastfeed their infants exclusively. Typically these women experience few breast changes during puberty or early pregnancy. In some cases they are still able to produce some breast milk, although the quantity is not likely to be sufficient to meet the nutritional needs of the infant. These mothers can offer supplemental nutrition to support optimal infant growth. Devices are available to allow mothers to offer supplements while the baby is nursing at the breast.

Because of the effects of estrogen, progesterone, human placental lactogen, and other hormones of pregnancy, changes occur in the breasts in preparation for lactation. Breasts increase in size corresponding to growth of glandular and adipose tissue. Blood flow to the breasts nearly doubles during pregnancy. Sensitivity of the breasts increases, and veins become more prominent. The nipples become more erect, and the areola darken. Nipples and areola may enlarge. Around week 16 of gestation the alveoli begin producing colostrum (early milk). Montgomery glands on the areola enlarge. The oily substance secreted by these sebaceous glands helps provide protection against the mechanical stress of sucking and invasion by pathogens. The odor of the secretions can be a means of communication with the infant (Geddes, 2007).

Lactogenesis

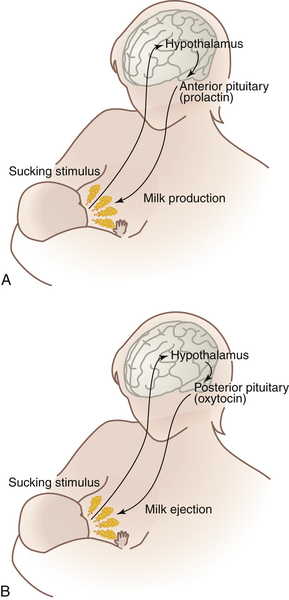

After the mother gives birth a precipitous fall in estrogen and progesterone levels triggers the release of prolactin from the anterior pituitary gland. During pregnancy, prolactin prepares the breasts to secrete milk and, during lactation, to synthesize and secrete milk. Prolactin levels are highest during the first 10 days after birth, gradually declining over time but remaining above baseline levels for the duration of lactation. Prolactin is produced in response to infant suckling and emptying of the breasts (Fig. 25-4, A). Milk production is a supply-meets-demand system; that is, as milk is removed from the breast, more is produced. Incomplete removal of milk from the breasts can lead to decreased milk supply.

Oxytocin is the other hormone essential to lactation. As the nipple is stimulated by the suckling infant, the posterior pituitary is prompted by the hypothalamus to produce oxytocin. This hormone is responsible for the milk ejection reflex (MER), or let-down reflex (see Fig. 25-4, B). The myoepithelial cells surrounding the alveoli respond to oxytocin by contracting and sending the milk forward through the ducts to the nipple. Many let-downs can occur with each feeding session. Thoughts, sights, sounds, or odors that the mother associates with her baby (or other babies), such as hearing the baby cry, can trigger the MER. Many women report a tingling “pins and needles” sensation in the breasts as milk ejection occurs, although some mothers can detect milk ejection only by observing the sucking and swallowing of the infant. The milk ejection reflex also can occur during sexual activity because oxytocin is released during orgasm. The reflex can be inhibited by fear, stress, and alcohol consumption.

Oxytocin is the same hormone that stimulates uterine contractions during labor. Consequently, the MER can be triggered during labor, as evidenced by leakage of colostrum. This reflex readies the breast for immediate feeding by the infant after birth. Oxytocin has the important function of contracting the mother’s uterus after birth to control postpartum bleeding and promote uterine involution. Thus mothers who breastfeed are at decreased risk for postpartum hemorrhage. These uterine contractions, or “afterpains,” that occur with breastfeeding are often painful during and after feeding for the first 3 to 5 days, particularly in multiparas, although they resolve within 1 week after birth.

Prolactin and oxytocin have been called the “mothering hormones” because they affect the postpartum woman’s emotions, as well as her physical state. Many women report feeling thirsty or very relaxed during breastfeeding, probably as a result of these hormones.

The nipple-erection reflex is an important part of lactation. When the infant cries, suckles, or rubs against the breast, the nipple becomes erect, which assists in the propulsion of milk through the ducts to the nipple pores. Nipple sizes, shapes, and ability to become erect vary with individuals. Some women have flat or inverted nipples that do not become erect with stimulation; these women will likely need assistance with effective latch. These infants should not be offered bottles or pacifiers until breastfeeding is well established.

Uniqueness of Human Milk

Human milk is the ideal food for human infants. It is a dynamic substance with a composition that changes to meet the changing nutritional and immunologic needs of the infant’s growth and development. Breast milk is specific to the needs of each newborn; for example, the milk produced by mothers of preterm infants differs in composition from that of mothers who give birth at term.

Human milk contains immunologically active components that provide some protection against a broad spectrum of bacterial, viral, and protozoal infections. Secretory IgA is the major immunoglobulin in human milk; IgG, IgM, IgD, and IgE are also present. Human milk also contains T and B lymphocytes, epidermal growth factor, cytokines, interleukins, bifidus factor, complement (C3 and C4), and lactoferrin, all of which have a specific role in preventing localized and systemic bacterial and viral infections (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2005).

Human milk composition and volumes vary according to the stage of lactation. In lactogenesis stage I, beginning at approximately 16 to 18 weeks of pregnancy, the breasts are preparing for milk production by producing colostrum. Colostrum, a clear yellowish fluid, is more concentrated than mature milk and is extremely rich in immunoglobulins. It has higher concentrations of protein and minerals but less fat than mature milk. The high protein level of colostrum facilitates binding of bilirubin, and the laxative action of colostrum promotes early passage of meconium. Colostrum gradually changes to mature milk which quickly increases in volume; this transition is called “the milk coming in” or lactogenesis stage II. By day 3 to 5 after birth, most women have had this onset of copious milk secretion. Breast milk continues to change in composition for approximately 10 days, when the mature milk is established in stage III of lactogenesis (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2005).

Composition of mature milk changes during each feeding. As the infant nurses the fat content of breast milk increases. Initially, a bluish white foremilk is released that is part skim milk (approximately 60% of the volume) and part whole milk (approximately 35% of the volume). It provides primarily lactose, protein, and water-soluble vitamins. The hindmilk, or cream (approximately 5%), is usually released 10 to 20 minutes into the feeding, although it can occur sooner. It contains the denser calories from fat necessary for ensuring optimal growth and contentment between feedings. Because of this changing composition of human milk during each feeding, breastfeeding the infant long enough to supply a balanced feeding is important.

Milk production gradually increases as the baby grows. Infants have fairly predictable growth spurts (at approximately 10 days, 3 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months), when more frequent feedings stimulate increased milk production. These growth spurts usually last 24 to 48 hours, and then the infants resume their usual feeding pattern.

Care Management: the Breastfeeding Mother and Infant

Effective management of the breastfeeding mother and infant requires that caregivers are knowledgeable about the benefits, as well as the basic anatomic and physiologic aspects, of breastfeeding. Caregivers also need to know how to assist the mother with feedings and interventions for common problems. Ongoing support of the mother enhances her self-confidence and promotes a satisfying and successful breastfeeding experience. During the time in the hospital the mother is encouraged to view each breastfeeding session as a “feeding lesson” or “practice session” that will foster her self-confidence and promote a satisfying experience for herself and her infant.

The mother needs to understand infant behaviors in relation to breastfeeding. When newborns feel hunger, they usually cry vigorously until their needs are met. Some infants, however, will withdraw into sleep because of discomfort associated with hunger. Babies exhibit feeding-readiness cues that a knowledgeable caregiver can recognize. Instead of waiting to feed until the infant is crying in a distraught manner or withdrawing into sleep, beginning a feeding when the baby exhibits some of these cues (even during light sleep) is preferable:

• Hand-to-mouth or hand-to-hand movements

• Rooting reflex—infant moves toward whatever touches the area around the mouth and attempts to suck

Babies normally consume small amounts of milk during the first 3 days of life. As the baby adjusts to extrauterine life and the digestive tract is cleared of meconium, milk intake increases from 15 to 30 ml per feeding in the first 24 hours to 60 to 90 ml by the end of the first week.

At birth and for several months thereafter, all of the secretions of the infant’s digestive tract contain enzymes especially suited to the digestion of human milk. The ability to digest foods other than milk depends on the physiologic development of the infant. The capacities for salivary, gastric, pancreatic, and intestinal digestion increase with age, indicating that the natural time for introduction of solid foods is around 6 months of age.

Babies are born with a tongue extrusion reflex that causes them to push out of the mouth anything placed on the tongue. This reflex disappears by 6 months—another indication of physiologic readiness for solids.

Early introduction of solids can make the infant more prone to food allergies. It can also lead to decreased intake of breast milk or formula and is associated with earlier cessation of breastfeeding.

In the early postpartum period, interventions focus on helping the mother and the newborn initiate breastfeeding and achieve some degree of success and satisfaction before discharge from the hospital or birthing center. Interventions to promote successful breastfeeding include basics such as latch and positioning, signs of adequate feeding, and self-care measures such as prevention of engorgement. It is important to provide the parents with a list of resources that they may contact after discharge from the hospital.

The ideal time to begin breastfeeding is immediately after birth. Newborns without complications should be allowed to remain in direct skin-to-skin contact with the mother until the baby is able to breastfeed for the first time (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2005). Each mother should receive instruction, assistance, and support in positioning and latching-on until she is able to do so independently (see the Nursing Process box).

Positioning

The four basic positions for breastfeeding are the football or clutch hold (under the arm), cradle, modified cradle or across-the-lap, and side-lying (Fig. 25-5). Initially it is advisable to

FIG. 25-5 Breastfeeding positions. A, Football or clutch (under the arm) hold. B, Across the lap (modified cradle). C, Cradling. D, Lying down. (A and B, Courtesy Kathryn Alden, Chapel Hill, NC; C and D, courtesy Marjorie Pyle, RNC, Lifecircle, Costa Mesa, CA.)

use the position that most easily facilitates latch while allowing maximal comfort for the mother. The football or clutch hold is often recommended for early feedings because the mother can easily see the baby’s mouth as she guides the infant onto the nipple.

Mothers who gave birth by cesarean often prefer the football or clutch hold. The modified cradle or across-the-lap hold also works well for early feedings, especially with smaller babies. The side-lying position allows the mother to rest while breastfeeding. Women with perineal pain and swelling often prefer this position. Cradling is the most common breastfeeding position for infants who have learned to latch easily and feed effectively. Before discharge from the birth institution the nurse can assist the mother to try all of the positions so that she will feel confident in trying these positions at home.

During breastfeeding the mother should be as comfortable as possible. The nurse might suggest that the mother take time to empty her bladder and attend to other needs before starting a feeding session. The mother should place the infant at the level of the breast, supported by firm pillows or folded blankets, turn the infant completely onto his or her side, facing the mother so that the infant is “belly to belly,” with the arms “hugging” the breast. The baby’s mouth is directly in front of the nipple. The mother should support the baby’s neck and shoulders with her hand and not push on the occiput. The baby’s body is held in correct alignment (ears, shoulders, and hips are in a straight line) during latch and feeding.

Latch

Latch is defined as placement of the infant’s mouth over the nipple, areola, and breast, making a seal between the mouth and breast to create adequate suction for milk removal. In preparation for latch during early feedings the mother should manually express a few drops of colostrum or milk and spread it over the nipple. This action lubricates the nipple and entices the baby to open the mouth as the milk is tasted.

To facilitate latch the mother supports her breast in one hand with the thumb on top and four fingers underneath at the back edge of the areola. The breast is compressed slightly, as one might compress a large sandwich in preparing to take a bite, so that an adequate amount of breast tissue is taken into the mouth with latch. Most mothers need to support the breast during feeding for at least the first days until the infant is adept at feeding.

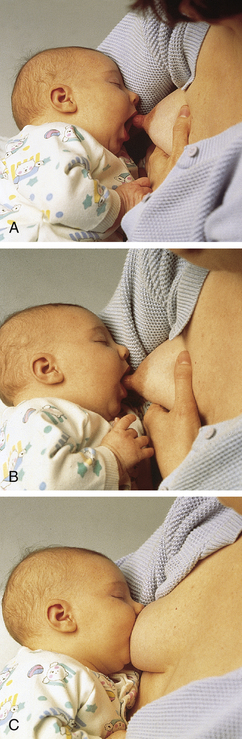

With the baby held close to the breast and the mouth directly in front of the nipple the mother tickles the baby’s lower lip with her nipple, stimulating the mouth to open. When the mouth is open wide and the tongue is down the mother quickly “hugs” the baby to the breast, bringing the baby onto the nipple. She brings the infant to the breast, not the breast to the infant (Fig. 25-6).

FIG. 25-6 Latch. A, The mother tickles baby’s lower lip with the nipple until he or she opens wide. B, Once baby’s mouth is opened wide, she quickly “hugs” the baby to the breast. C, Baby should have as much areola (dark area around nipple) in his or her mouth as possible, not just the nipple. (Courtesy Medela, Inc., McHenry, IL.)

The amount of areola in the baby’s mouth with correct latch depends on the size of the baby’s mouth and the size of the areola and the nipple. In general, the baby’s mouth should cover the nipple and an areolar radius of approximately 2 to 3 cm all around the nipple. If breastfeeding is painful, the baby likely has not taken enough of the breast into the mouth, and the tongue is pinching the nipple.

When latched correctly, the baby’s cheeks and chin are touching the breast. Depressing the breast tissue around the baby’s nose to create breathing space is not necessary. If the mother is worried about the baby’s breathing, she can raise the baby’s hips slightly to change the angle of the baby’s head at the breast. If the baby’s nostrils happen to become occluded by the breast, reflexes will prompt the newborn to move the head and pull back to breathe.

If the baby is nursing appropriately, (1) the mother reports a firm tugging sensation on her nipples but feels no pinching or pain, (2) the baby sucks with cheeks rounded, not dimpled, (3) the baby’s jaw glides smoothly with sucking, and (4) swallowing is usually audible. Sucking creates a vacuum in the intraoral cavity as the breast is compressed between the tongue and the palate. If the mother feels pinching or pain after the initial sucks or does not feel a strong tugging sensation on the nipple, the latch and positioning are evaluated. Any time the signs of adequate latch and sucking are not present the baby should be taken off the breast and latch attempted again. To prevent nipple trauma as the baby is taken off the breast the mother is instructed to break the suction by inserting a finger in the side of the baby’s mouth between the gums and leaving it there until the nipple is completely out of the baby’s mouth (Fig. 25-7). (See Nursing Care Plan.)

Milk Ejection or Let-Down

As the baby begins sucking on the nipple the milk ejection, or let-down, reflex is stimulated (see Fig. 25-4, B). The following signs indicate that milk ejection has occurred:

• The mother may feel a tingling sensation in the nipples and in the breasts, although many women never feel when milk ejection (let down) occurs.

• The baby’s suck changes from quick, shallow sucks to a slower, more drawing, sucking pattern.

• Audible swallowing is present as the baby sucks.

• In the early days the mother feels uterine cramping and can have increased lochia during and after feedings.

Frequency of Feedings

Newborns need to breastfeed at least 8 to 12 times in a 24-hour period. Feeding patterns are variable because every baby is unique. Some infants will breastfeed every 2 to 3 hours throughout a 24-hour period. Others may cluster-feed, breastfeeding every hour or so for three to five feedings and then sleeping for 3 to 4 hours between clusters. During the first 24 to 48 hours after birth, most babies do not awaken this often to feed. Parents need to understand that they should awaken the baby to feed at least every 3 hours during the day and at least every 4 hours at night. (Feeding frequency is determined by counting from the beginning of one feeding to the beginning of the next.) Once the infant is feeding well and gaining weight adequately, going to demand feeding is appropriate, in which case the infant determines the frequency of feedings. (With demand feeding the infant should still receive at least eight feedings in 24 hours.) Caregivers should caution parents against attempting to place newborn infants on strict feeding schedules.

Infants should be fed whenever they exhibit feeding cues. Keeping the baby close is the best way to observe and respond to infant feeding cues. Newborns should remain with mothers during the recovery period after birth and room-in during the hospital stay. At home, babies should be kept nearby so that parents can observe signs that the baby is ready to feed. One recommendation is that mother and breastfeeding infant sleep in proximity to promote breastfeeding (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2005). The issue of bed-sharing (co-bedding) has raised concerns because of the association between a higher incidence of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and bed-sharing with an adult. Experts recommend that the breastfeeding infant be placed in a bassinet near the mother, which would then allow for more convenient breastfeeding and at the same time prevent continuous bed-sharing (AAP Task Force on SIDS, 2005).

Duration of Feedings

The duration of breastfeeding sessions is highly variable because the timing of milk transfer differs for each mother-baby pair. The average time for early feedings is 30 to 40 minutes or approximately 15 to 20 minutes per breast. As infants grow, they become more efficient at breastfeeding, and consequently the length of feedings decreases.

Some mothers prefer one-sided nursing, in which case the baby nurses only one breast at each feeding. The first breast offered should be alternated at each feeding to ensure that each breast receives equal stimulation and emptying. In reality, instructing mothers to feed for a set number of minutes is inappropriate. Mothers can determine when a baby has finished a feeding. The baby’s sucking and swallowing pattern has slowed, the breast is softened, and the baby appears content and may fall asleep or release the nipple.

If a baby seems to be feeding effectively and the urine output is adequate but the weight gain is not satisfactory, the mother may be switching to the second breast too soon. The high-lactose, low-fat foremilk can cause the baby to have explosive stools, gas pains, and inconsolable crying. Feeding on the first breast until it softens ensures that the baby receives the higher fat hindmilk, which usually results in increased weight gain.

Indicators of Effective Breastfeeding

In the newborn period, when breastfeeding is becoming established, parents should be taught about the signs that breastfeeding is going well. Awareness of these signs will help them recognize when problems arise so that they can seek appropriate assistance (Box 25-2).

During the early days of breastfeeding, keeping a feeding diary can be helpful, recording the time and length of feedings, as well as infant urine output and bowel movements. The data from the diary provide evidence of the effectiveness of breastfeeding and are useful to health care providers in assessing adequacy of feeding. Parents are instructed to take this feeding diary to the follow-up visit with the pediatric care provider.

Although the number of wet diapers and bowel movements is highly indicative of feeding adequacy, it is also important that parents are aware of the expected changes in the characteristics of urine output and bowel movements during the early newborn period. As the volume of breast milk increases, urine becomes more dilute and should be light yellow; dark, concentrated urine can be associated with inadequate intake and possible dehydration. (Note: Infants with jaundice often have darker urine as bilirubin is excreted.) The first 1 to 2 days after birth, newborns pass meconium stools, which are greenish black, thick, and sticky. By day 2 or 3, the stools become greener, thinner, and less sticky. If the mother’s milk has come in by day 3 or 4, the stools will start to appear greenish yellow and are looser. By the end of the first week, breast milk stools are yellow, soft, and seedy (they resemble a mixture of mustard and cottage cheese). If an infant is still passing meconium stool by day 3 or 4, breastfeeding effectiveness and milk transfer should be assessed.

For approximately the first month, breastfed infants typically have 5 to 10 bowel movements per day, often associated with feedings. The stooling pattern gradually changes; breastfed infants can continue to stool more than once per day or they may stool only every 2 to 3 days. As long as the baby continues to gain weight and appears healthy, this decrease in the number of bowel movements is normal.

Supplements, Bottles, and Pacifiers

Unless a medical indication exists, no supplements should be given to breastfeeding infants (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2005; ABM Protocol Committee, 2009). With sound breastfeeding knowledge and practice, supplements are rarely needed. If a supplement is deemed necessary, giving the baby expressed breast milk is best. Prior to supplementation, it is important to perform a careful evaluation of the mother-infant dyad.

Possible indications for supplementary feeding include infant factors such as hypoglycemia, dehydration, weight loss of 8% to 10% associated with delayed lactogenesis, delayed passage of bowel movements or meconium stool continued to day 5, poor milk transfer, or hyperbilirubinemia. Maternal

indications for possible supplementation include delayed lactogenesis, and intolerable pain during feedings. Women who have had previous breast surgery such as augmentation or reduction may need to provide supplementary feedings for their infants (ABM Protocol Committee, 2009).

Offering formula to a baby after breastfeeding just to “make sure the baby is getting enough” is normally unnecessary and should be avoided. This action can contribute to low milk supply because the baby becomes overly full and does not breastfeed often enough. Supplementation interferes with the supply-meets-demand system of milk production. The parents can interpret the baby’s willingness to take a bottle to mean that the mother’s milk supply is inadequate. They need to know that a baby will automatically suck from a bottle, as the easy flow of milk from the nipple triggers the suck-swallow reflex.

Newborns can become confused going from breast to bottle or bottle to breast when breastfeeding is first being established. Breastfeeding and bottle feeding require different oral motor skills. The way newborns use their tongues, cheeks, and lips, as well as the swallowing patterns, are very different. Even though some newborns can transition easily between breast and bottle, others experience considerable difficulty. Because predicting which infants will adapt well and which ones will not is impossible, it is best to avoid bottles until breastfeeding is well established, usually after 3 to 4 weeks.

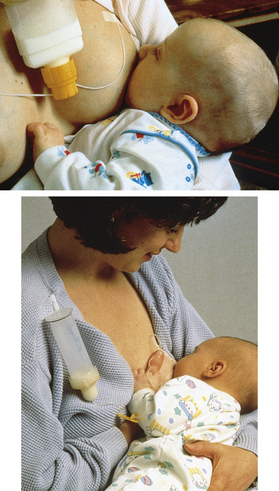

If the baby needs additional breast milk or formula, parents can use supplemental nursing devices, in which case the baby can be supplemented while breastfeeding (see Fig. 25-8). Infants can also be fed using a spoon, dropper, cup, or syringe. If parents choose to use bottles, a slow-flow nipple is recommended. Although some parents combine breastfeeding and bottle feeding, many babies never take a bottle and go directly from the breast to a cup.

Pacifier use with breastfeeding infants is usually discouraged until breastfeeding is well established. However, evidence does not support an adverse relationship between pacifier use and the exclusivity or duration of breastfeeding (Jenik, Vain, Gorestein, Jacobi, & Pacifier and Breastfeeding Trial Group, 2009; O’Connor, Tanabe, Siadaty, & Hauck, 2009). Because a correlation has been identified between pacifier use at bedtime and a decreased risk of SIDS, experts recommend that the caregiver consider offering the infant a pacifier at naptime or

regular bedtime. In the breastfeeding infant the pacifier is not offered until after 1 month, at which time breastfeeding should be well established (AAP Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, 2005; AWHONN, 2007).

Special Considerations

During the first few days of life, some babies need to be awakened for feedings. Parents are instructed to be alert for behavioral signs or feeding cues. If the infant is awakened from a sound sleep, attempts at feeding are more likely to be unsuccessful. Unwrapping the baby, changing the diaper, sitting the baby upright, talking to the baby with variable pitch, gently massaging the baby’s chest or back, and stroking the palms or soles may bring the baby to an alert state. It is helpful to place the sleepy baby skin-to-skin with the mother; she can move the infant to the breast when feeding readiness cues are apparent (Box 25-3).

Fussy Baby

Babies sometimes awaken from sleep crying frantically. Although they are hungry, they cannot focus on feeding until they are calmed. Parents can swaddle the baby, hold the baby close, talk soothingly, and allow the baby to suck on a clean finger until calm enough to latch on to the breast. Placing the baby skin-to-skin with the mother can be very effective in calming a fussy infant (Box 25-4).

Infant fussiness during feeding can be the result of birth injury such as bruising of the head or fractured clavicle. Changing the feeding position can help alleviate this problem.

Infants who were suctioned extensively or intubated at birth can demonstrate an aversion to oral stimulation. The baby may scream and stiffen if anything approaches the mouth. Parents need to spend time holding and cuddling the baby before attempting to breastfeed.

An infant can become fussy and appear discontented when sucking if the nipple does not extend far enough into the mouth. The feeding can begin with well-organized sucks and swallows, but the infant soon begins to pull off the breast and cry. The mother should support her breast throughout the feeding so that the nipple stays in the same position as the feeding proceeds and the breast softens.

Fussiness can be related to GI distress (e.g., cramping, gas pains). It can occur in response to an occasional feeding of infant formula, or it can be related to something the mother has ingested, although most women are able to eat a normal diet without causing GI distress to the breastfeeding infant. No standard foods should be avoided by all mothers when breastfeeding because each mother-baby couple responds individually. However, an important point to note is that the flavor of breast milk changes according to the foods and spices ingested by the mother. If a food is suspected to cause GI problems in the infant, the mother should eliminate it from her diet for 2 weeks, reintroduce the food, and see if symptoms reappear. When a strong family history of milk protein intolerance exists, the baby may develop colic-like symptoms. Similarly, if the risk of allergy is high, breastfeeding mothers may be advised to avoid peanuts and other potent allergens (Becker & Scott, 2008).

Persistent crying or refusing to breastfeed can indicate illness, and parents are instructed to notify the health care provider if either circumstance occurs. Ear infections, sore throat, or oral thrush can cause the infant to be fussy and not breastfeed well.

Slow Weight Gain

Newborn infants typically lose 5% to 6% of body weight before they gain weight. Weight loss of 7% or more in a breastfeeding infant during the first 3 days of life needs to be investigated. After the early milk has transitioned to mature milk, infants should gain approximately 110 to 200 g/week or 20 to 28 g/day for the first 3 months. (Breastfed infants usually do not gain weight as quickly as formula-fed infants.) Health care providers should evaluate and monitor infants who continue to lose weight after 5 days, who do not regain birth weight by 14 days, or whose weight is below the 10th percentile by 1 month.

Parents are taught the warning signs of ineffective breastfeeding, including inadequate weight gain, minimal output, and feeding constantly (Box 25-5). If any of these warning signs are present, the parent should notify the health care provider.

At times, slow weight gain is related to inadequate breastfeeding. Feedings can be short or infrequent, or the infant can be latching incorrectly or sucking ineffectively or inefficiently. Other possibilities are illness or infection, malabsorption, or circumstances that increase the baby’s energy needs, such as congenital heart disease, cystic fibrosis, or simply being small for gestational age. Slow weight gain must be differentiated from failure to thrive; this can be a serious problem that warrants medical intervention.

Maternal factors can be the cause of slow weight gain. The mother can have a problem with inadequate emptying of the breasts, pain with feeding, or inappropriate timing of feedings. Inadequate glandular breast tissue or previous breast surgery can affect milk supply. Severe intrapartum or postpartum hemorrhage, illness, or medications can decrease milk supply. Stress and fatigue also negatively affect milk production.

In most instances, the solution to slow weight gain is to improve the feeding technique. Positioning and latch are evaluated and adjustments are made. Adding a feeding or two in a 24-hour period can help. If the problem is a sleepy baby, parents are instructed in waking techniques.

Using alternate breast massage during feedings can help increase the amount of milk going to the infant. With this technique the mother massages her breast from the chest wall to the nipple whenever the baby has sucking pauses. This technique also can increase the fat content of the milk, which aids in weight gain.

When babies are calorie deprived and need supplementation, they can receive expressed breast milk or formula with a nursing supplementer (Fig. 25-8), spoon, cup, syringe, or bottle. In most cases, supplementation is necessary only for a short time until the baby gains weight and is feeding adequately.

Jaundice

Chapter 23 discusses jaundice (hyperbilirubinemia) in the newborn in detail. The type of jaundice most often seen in term newborns is physiologic jaundice. Hyperbilirubinemia is caused by bilirubin levels that rise steadily over the first 3 to 4 days, peak around day 5, and decrease thereafter. This condition has been called early-onset jaundice or breastfeeding-associated jaundice, which in the breastfed infant can be associated with insufficient feeding and infrequent stooling. Colostrum has a natural laxative effect and promotes early passage of meconium. Bilirubin is excreted from the body primarily through the intestines. Infrequent stooling allows bilirubin in the stool to be reabsorbed into the infant’s system, thus promoting hyperbilirubinemia. Infants who receive water or glucose water supplements are more likely to have hyperbilirubinemia because only small amounts of bilirubin are excreted through the kidneys. Decreased caloric intake (less milk) is associated with decreased stooling and increased jaundice.

To prevent early-onset, breastfeeding-associated jaundice, newborns should be breastfed frequently during the first several days of life. Increased frequency of feedings is associated with decreased bilirubin levels.

To treat early-onset jaundice, breastfeeding is evaluated in terms of frequency and length of feedings, positioning, latch, and milk transfer. Factors such as a sleepy or lethargic infant or maternal breast engorgement can interfere with effective breastfeeding and should be corrected. If the infant’s intake of milk needs to be increased, a supplemental feeding device can deliver additional breast milk or formula while the infant is nursing. Hyperbilirubinemia may reach levels that require treatment with phototherapy (see Chapter 24).

Late-onset jaundice or breast milk jaundice affects a few breastfed infants and develops in the second week of life, peaking between 6 and 14 days. Affected infants are typically thriving, gaining weight, and stooling normally; all pathologic causes of jaundice have been ruled out. In the presence of other risk factors, hyperbilirubinemia may be severe enough to require phototherapy. In most cases of breast milk jaundice, no intervention is necessary. Some health care providers recommend temporary interruption of breastfeeding for 12 to 24 hours to allow bilirubin levels to decrease, although this approach is not preferred (Blackburn, 2007; Page-Goertz, 2008).

Any breastfeeding infant who develops jaundice should be carefully evaluated for weight loss greater than 7%, decreased milk intake, infrequent stooling (fewer than three stools per day by day 4), and decreased urine output (fewer than four to six wet diapers per day). Bilirubin levels should be assessed by serum testing or transcutaneous monitoring (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2005).

Preterm Infants

Human milk is the ideal food for preterm infants, with benefits that are unique and in addition to those received by term, healthy infants. Breast milk enhances retinal maturation in the preterm infant and improves neurocognitive outcomes; it also decreases the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis. Greater physiologic stability occurs with breastfeeding as compared with bottle feeding.

Initially, preterm milk contains higher concentrations of energy, fat, protein, sodium, chloride, potassium, iron, and magnesium than term milk. The milk is more similar to term milk by approximately 4 to 6 weeks. Human milk fortifier may be added to expressed breast milk if growth of the preterm infant is inadequate (Lanese & Cross, 2008).

Depending on gestational age and physical condition, many preterm infants are capable of breastfeeding for at least some feedings each day. Mothers of preterm infants who are not able to breastfeed their infants should begin pumping their breasts as soon as possible after birth with a hospital-grade electric pump (Fig. 25-9). To establish optimal milk supply the mother should use a dual collection kit, pumping both breasts simultaneously 8 to 12 times daily for the first 10 to 14 days. These women are taught proper handling and storage of breast milk to minimize bacterial contamination and growth. Kangaroo care (skin-to-skin contact) is advised until the baby is able to breastfeed, and while breastfeeding is established, because it enhances milk production (Lanese & Cross, 2008).

The mothers of preterm infants often receive specific emotional benefits in breastfeeding or providing breast milk for their babies. They find rewards in knowing they can provide the healthiest nutrition for the infant and believe that breastfeeding enhances feelings of closeness to the infant.

Late Preterm Infants

Neonates born at 34 0/7 to 36 6/7 weeks of gestation are categorized as late preterm infants. These newborns are at risk of feeding difficulties because of their low energy stores and high energy demands. They tend to be sleepy, with minimal and short wakeful periods. Late preterm infants often tire easily while feeding, have a weak suck, and low tone; these factors can contribute to inadequate milk intake. Early and extended skin-to-skin contact promotes breastfeeding and helps prevent hypothermia. Because these infants are more prone to positional apnea than term infants, mothers are advised to use the clutch (under the arm or football) hold for feeding, and to avoid flexing the head, which can impede breathing. Supplementation is often needed; expressed breast milk is the optimal supplement, preferably at the breast using a supplementer system (see Fig. 25-8) (Cleveland, 2010; Walker 2008a).

Breastfeeding Multiple Infants

Breastfeeding is especially beneficial to twins, triplets, and other higher-order multiples because of the immunologic and nutritional advantages, as well as the opportunity for the mother to interact with each baby frequently. Most mothers are capable of producing an adequate milk supply for multiple infants. Parenting multiples can be overwhelming, and mothers, as well as fathers, need extra support and assistance learning how to manage feedings (Fig. 25-10).

Expressing and Storing Breast Milk

Breast milk expression is a common practice, typically performed to obtain breast milk for someone else to feed to the baby. It is most often associated with maternal employment (Labiner-Wolfe, Fein, Shealy, & Wang, 2008). In some situations, expression of breast milk is necessary or desirable, such as when engorgement occurs, when the mother’s nipples are sore or damaged, when the mother and baby are separated as in the case of a preterm infant who remains in the hospital after the mother is discharged, or when the mother leaves the infant with a caregiver and will not be present for feeding. Some women express milk to have an emergency supply (Labiner-Wolfe et al.). Some women choose to pump exclusively, providing breast milk for their infants, but never allowing the baby to suckle at the breast (Shealy, Scanlon, Labiner-Wolfe, Fein, & Grummer-Strawn, 2008).

Because pumping and hand expression are rarely as efficient as a baby in removing milk from the breast, the milk supply is never judged based solely on the volume expressed. Milk volume can be more accurately assessed using pre- and postfeeding infant weights.

Hand Expression: All mothers should be instructed in hand expression. After thoroughly washing her hands, the mother places one hand on her breast at the edge of the areola. With her thumb above and fingers below, she presses in toward her chest wall and gently compresses the breast while rolling her thumb and fingers forward toward the nipple. She repeats these motions rhythmically until the milk begins to flow. The mother simply maintains steady, light pressure while the milk is flowing easily. The thumb and fingers should not pinch the breast or slip down to the nipple, and the mother should rotate her hand to reach all sections of the breast.

Mechanical Expression (Pumping): For most women, recommendations are to initiate pumping only after the milk supply is well established and the infant is latching and breastfeeding well. However, when breastfeeding is delayed after birth, such as when babies are ill or preterm, mothers should begin pumping with an electric breast pump as soon as possible and continue to pump regularly until the infant is able to breastfeed effectively.

Numerous approaches to pumping can be used. Some women pump on awakening in the morning or after feedings. Others choose to pump one breast while the baby is feeding from the other; this is usually done if the baby typically feeds from only one breast at each feeding. Double pumping (pumping both breasts at the same time) saves time and can stimulate the milk supply more effectively than single pumping (Fig. 25-11).

The amount of milk obtained when pumping depends on the type of pump being used, the time of day, the time since the baby breastfed, the mother’s milk supply, how practiced she is at pumping, and her comfort level (pumping is uncomfortable for some women). Breast milk can vary in color and consistency, depending on the time of day, the age of the baby, and foods the mother has eaten.

Types of Pumps: Many types of breast pumps are available, varying in price and effectiveness. Before purchasing or renting a breast pump the mother will benefit from counseling by a nurse or lactation consultant to determine which pump best suits her needs. The flange (funnel-shaped device that fits over the nipple or areola) should fit the nipple to prevent nipple pain, trauma, and possible reduction in milk supply. Mothers are advised to use the lowest suction setting on electric pumps, increasing gradually if needed. Breast massage before and during pumping can increase the amount of milk obtained (Mannel, 2008).

Manual or hand pumps are the least expensive and can be the most appropriate where portability and quietness of operation are important. These pumps are most often used by mothers who are pumping for an occasional bottle (Fig. 25-12).

Full-service electric pumps, or hospital-grade pumps (see Figs. 25-9 and 25-11), most closely duplicate the sucking action and pressure of the breastfeeding infant. When breastfeeding is delayed after birth (e.g., preterm or ill newborn), or when the mother and baby are separated for lengthy periods, these pumps are most appropriate. Because hospital-grade breast pumps are very heavy and expensive, portable versions of these pumps are available to rent for home use.

Electric self-cycling double pumps are efficient and easy to use. These pumps are designed for working mothers. Some of these pumps come with carry bags containing coolers to store pumped milk.

Smaller electric or battery-operated pumps are typically used when pumping is performed occasionally, but some models are satisfactory for working mothers or others who pump on a regular basis.

Storage of Breast Milk: The preferred containers for long-term storage of breast milk are hard sided, such as hard plastic or glass, with an airtight seal. For short-term storage (less than 72 hours), plastic bags designed for human milk can be safely used.

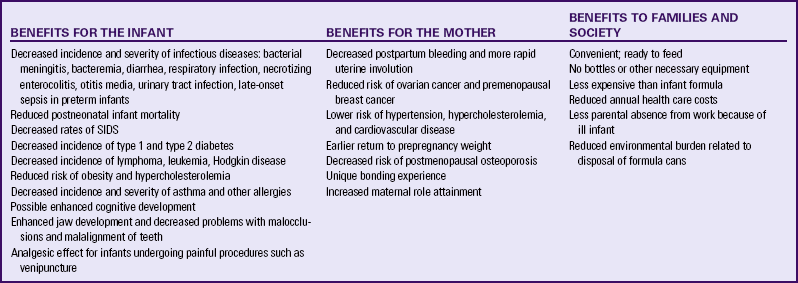

For full-term healthy infants, under very clean conditions, freshly expressed breast milk can be safely stored at room temperature (16-29° C [60-85° F]) for up to 8 hours and can be refrigerated (<4° C, 39° F) safely for up to 8 days. Milk can be frozen for up to 6 months in the freezer compartment of a two door refrigerator (<-5° C [23° F]) and up to 12 months in a freezer (<-4° C [24° F]). When breast milk is stored, the container should be dated, and the oldest milk should be used first (ABM Protocol Committee, 2010; Jones & Tully, 2006).

Frozen milk is thawed by placing the container in the refrigerator for gradual thawing or in warm water for faster thawing. It cannot be refrozen and should be used within 24 hours. After thawing, the container needs to be shaken so as to mix the layers that have separated (ABM Protocol Committee, 2010; Jones & Tully, 2006) (see Teaching Guidelines box: Breast Milk Storage Guidelines for Home Use for Full-Term Infants).

Being Away from the Baby

Although returning to work is a common reason for early weaning, many women are able to combine breastfeeding successfully with employment, attending school, or other commitments. If feedings are missed, the milk supply can be affected. Some women’s bodies adjust the milk supply to the times they are with their infants for feedings, whereas other women find they must pump, otherwise the milk supply diminishes rapidly.

Maternal Employment: Returning to work after birth is associated with a decrease in the duration of breastfeeding. Women who return to work often face workplace challenges in breastfeeding such as lack of flexibility in work schedules, inadequate breaks to allow time for pumping, lack of privacy, lack of space for pumping, and lack of support from supervisors or coworkers. Increasing numbers of women are working from home and are likely to resume their jobs earlier than the traditional 6-week to 3-month maternity leave. Issues that can challenge continued breastfeeding while working include fatigue, child care concerns, competing demands, and household responsibilities (Walker, 2006).

Employed mothers can continue breastfeeding with appropriate guidance and support. They are encouraged to set realistic goals for employment and breastfeeding, with accurate information regarding the costs, risks, and benefits of available feeding options.

Women who are able to breastfeed their infants during the workday tend to breastfeed longer. With increasing numbers of women having the option of working from home, this situation is becoming more common. Many working mothers pump their milk while they are at work and save the milk for later feedings. Working mothers who are unable to pump or breastfeed their infants during the workday have the shortest duration of breastfeeding (Fein, Mandal, & Roe, 2008).

Because women are a significant proportion of the workforce, many companies make provisions for breastfeeding women returning to work. Breastfeeding programs typically include on-site lactation rooms and/or education and consulting services. Lactation rooms that provide space and privacy for pumping are available at many worksites and on college campuses (Fig. 25-13). In some instances, breastfeeding women bring their babies to work. Since 1999, by law, women may breastfeed in federal buildings and on federal property. Some states have enacted legislation to ensure that mothers may breastfeed their babies in public places. These efforts can help mothers breastfeed longer.

FIG. 25-13 Lactation room. Note the breast pump, rocking chair, nursing foot stool, changing table, books, and supplies. (Courtesy Cheryl Briggs, RNC, Annapolis, MD.)