Transition to Parenthood

• Identify parental and infant behaviors that facilitate and those that inhibit parental attachment.

• Describe sensual responses that strengthen attachment.

• Examine the process of becoming a mother and becoming a father.

• Compare maternal adjustment and paternal adjustment to parenthood.

• Describe how the nurse can facilitate parent-infant adjustment.

• Examine the effects of the following on parenting responses and behavior: parental age (i.e., adolescence and older than 35 years), social support, culture, socioeconomic conditions, personal aspirations, and sensory impairment.

Becoming a parent creates a period of change and instability for men and women who decide to have children. This period occurs whether parenthood is biologic or adoptive and whether the parents are married husband-wife couples, cohabiting couples, single mothers, single fathers, lesbian couples with one woman as biologic mother, or gay male couples who adopt a child. Parenting is a process of role attainment and role transition. The transition is an ongoing process as the parents and infant develop and change.

Parental Attachment, Bonding, and Acquaintance

The process by which a parent comes to love and accept a child and a child comes to love and accept a parent is known as attachment. Attachment occurs through the process of bonding. In their bonding theory, Klaus and Kennell (1976) proposed that there is a sensitive period during the first few minutes or hours after birth when mothers and fathers must have close contact with their infants to optimize the child’s later development. Klaus and Kennell (1982) later revised their theory of parent-infant bonding, modifying their claim of the critical nature of immediate contact with the infant after birth. They acknowledged the adaptability of human parents, stating that more than minutes or hours were needed for parents to form an emotional relationship with their infants. The terms attachment and bonding continue to be used interchangeably.

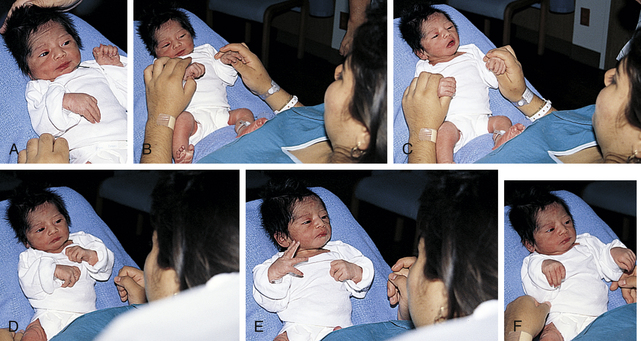

Attachment is developed and maintained by proximity and interaction with the infant, through which the parent becomes acquainted with the infant, identifies the infant as an individual, and claims the infant as a member of the family. Positive feedback between the parent and the infant through social, verbal, and nonverbal responses (whether real or perceived) facilitates the attachment process. Attachment occurs through a mutually satisfying experience. A mother commented on her son’s grasp reflex, “I put my finger in his hand, and he grabbed right on. It is just a reflex, I know, but it felt good anyway” (Fig. 22-1).

The concept of attachment includes mutuality; that is, the infant’s behaviors and characteristics elicit a corresponding set of parental behaviors and characteristics. The infant displays signaling behaviors such as crying, smiling, and cooing that initiate the contact and bring the caregiver to the child. These behaviors are followed by executive behaviors such as rooting, grasping, and postural adjustments that maintain the contact. Most caregivers are attracted to an alert, responsive, cuddly infant and repelled by an irritable, apparently disinterested infant. Attachment occurs more readily with the infant whose temperament, social capabilities, appearance, and sex fit the parent’s expectations. If the infant does not meet these expectations, the parent’s disappointment can delay the attachment process. Table 22-1 presents a comprehensive list of classic infant behaviors affecting parental attachment. Table 22-2 presents a corresponding list of parental behaviors that affect infant attachment.

TABLE 22-1

INFANT BEHAVIORS AFFECTING PARENTAL ATTACHMENT

| FACILITATING BEHAVIORS | INHIBITING BEHAVIORS |

| Visually alert; eye-to-eye contact; tracking or following of parent’s face | Sleepy; eyes closed most of the time; gaze aversion |

| Appealing facial appearance; randomness of body movements reflecting helplessness | Resemblance to person parent dislikes; hyperirritability or jerky body movements when touched |

| Smiles | Bland facial expression; infrequent smiles |

| Vocalization; crying only when hungry or wet | Crying for hours on end; colicky |

| Grasp reflex | Exaggerated motor reflex |

| Anticipatory approach behaviors for feedings; sucks well; feeds easily | Feeds poorly; regurgitates; vomits often |

| Enjoys being cuddled and held | Resists holding and cuddling by crying, stiffening body |

| Easily consolable | Inconsolable; unresponsive to parenting, caretaking tasks |

| Activity and regularity somewhat predictable | Unpredictable feeding and sleeping schedule |

| Attention span sufficient to focus on parents | Inability to attend to parent’s face or offered stimulation |

| Differential crying, smiling, and vocalizing; recognizes and prefers parents | Shows no preference for parents over others |

| Approaches through locomotion | Unresponsive to parent’s approaches |

| Clings to parent; puts arms around parent’s neck | Seeks attention from any adult in room |

| Lifts arms to parents in greeting | Ignores parents |

Source: Gerson, E. (1973). Infant behavior in the first year of life. New York: Raven Press.

TABLE 22-2

PARENTAL BEHAVIORS AFFECTING INFANT ATTACHMENT

| FACILITATING BEHAVIORS | INHIBITING BEHAVIORS |

| Looks; gazes; takes in physical characteristics of infant; assumes en face position; eye contact | Turns away from infant; ignores infant’s presence |

| Hovers; maintains proximity; directs attention to, points to infant | Avoids infant; does not seek proximity; refuses to hold infant when given opportunity |

| Identifies infant as unique individual | Identifies infant with someone parent dislikes; fails to recognize any of infant’s unique features |

| Claims infant as family member; names infant | Fails to place infant in family context or identify infant with family member; has difficulty naming |

| Touches; progresses from fingertip to fingers to palms to encompassing contact | Fails to move from fingertip touch to palmar contact and holding |

| Smiles at infant | Maintains bland countenance or frowns at infant |

| Talks to, coos, or sings to infant | Wakes infant when infant is sleeping; handles roughly; hurries feeding by moving nipple continuously |

| Expresses pride in infant | Expresses disappointment, displeasure in infant |

| Relates infant’s behavior to familiar events | Does not incorporate infant into life |

| Assigns meaning to infant’s actions and sensitively interprets infant’s needs | Makes no effort to interpret infant’s actions or needs |

| Views infant’s behaviors and appearance in positive light | Views infant’s behavior as exploiting, deliberately uncooperative; views appearance as distasteful, ugly |

Source: Mercer, R. (1983). Parent-infant attachment. In L. Sonstegard, K. Kowalski, & B. Jennings (Eds.), Women’s Health (Vol. 2). New York: Grune & Stratton.

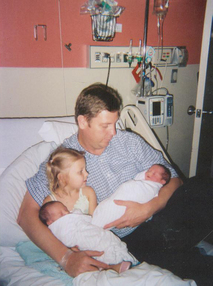

An important part of attachment is acquaintance. Parents use eye contact (Fig. 22-2), touching, talking, and exploring to become acquainted with their infant during the immediate postpartum period. Adoptive parents undergo the same process when they first meet their new child. During this period families engage in the claiming process, which is the identification of the new baby (Fig. 22-3). The child is first identified in terms of “likeness” to other family members, then in terms of “differences,” and finally in terms of “uniqueness.” The unique newcomer is thus incorporated into the family. Mothers and fathers examine their infant carefully and point out characteristics that the child shares with other family members and that are indicative of a relationship between them. Maternal comments such as the following reveal the claiming process: “Everyone says, ‘He’s the image of his father,’ but I found one part like me—his toes are shaped like mine.”

FIG. 22-2 Early acquaintance between parents and newborn as mother holds infant in en face position. (Courtesy Kathryn Alden, Chapel Hill, NC.)

FIG. 22-3 Father looks for resemblance between newborns and older daughter. (Courtesy Cheryl Briggs, RNC, Annapolis, MD.)

On the other hand, some mothers react negatively. They “claim” the infant in terms of the discomfort or pain the baby causes. The mother interprets the infant’s normal responses as being negative toward her and reacts to her child with dislike or indifference. She does not hold the child close or touch the child to be comforting. For example, “The nurse put the baby into Lydia’s arms. She promptly laid him across her knees and glanced up at the television. ‘Stay still until I finish watching; you’ve been enough trouble already.’”

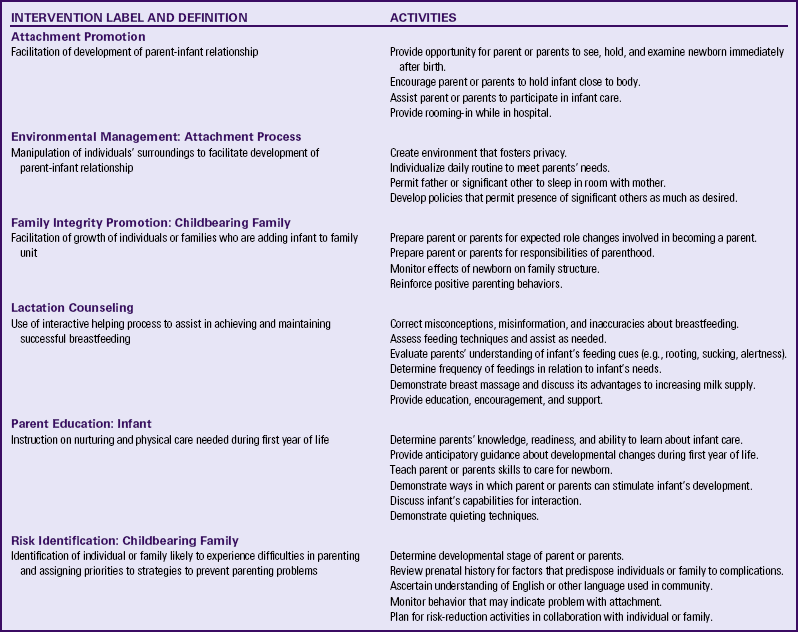

Nursing interventions related to the promotion of parent-infant attachment are numerous and varied (Table 22-3). They can enhance positive parent-infant contacts by heightening

TABLE 22-3

EXAMPLES OF PARENT-INFANT ATTACHMENT INTERVENTIONS

Modified from Bulechek, G., Butcher, H., & Dochterman, J. (2008). Nursing interventions classification (NIC) (5th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

parental awareness of an infant’s responses and ability to communicate. As the parent attempts to become competent and loving in that role, nurses can bolster the parent’s self-confidence and ego. Nurses can identify actual and potential problems and collaborate with other health care professionals who will provide care for the parents after discharge. Nursing considerations for fostering maternal-infant bonding among special populations may vary (see the Cultural Considerations box).

Assessment of Attachment Behaviors

One of the most important areas of assessment is careful observation of specific behaviors thought to indicate the formation of emotional bonds between the newborn and the family, especially the mother. Unlike physical assessment of the neonate, which has concrete guidelines to follow, assessment of parent-infant attachment relies more on skillful observation and interviewing. Rooming-in of mother and infant and liberal visiting privileges for father or partner, siblings, and grandparents provide nurses with excellent opportunities to observe interactions and identify behaviors that demonstrate positive or negative attachment. Attachment behaviors can be easily observed during infant feeding sessions. Box 22-1 presents guidelines for assessment of attachment behaviors.

During pregnancy, and often even before conception occurs, parents develop an image of the “ideal” or “fantasy” infant. At birth the fantasy infant becomes the real infant. How closely the dream child resembles the real child influences the bonding process. Assessing such expectations during pregnancy and at the time of the infant’s birth allows identification of discrepancies in the parents’ view of the fantasy child versus the real child.

The labor process significantly affects the immediate attachment of mothers to their newborn infants. Factors such as a long labor, feeling tired or “drugged” after birth, and problems with breastfeeding can delay the development of initial positive feelings toward the newborn.

Parent-Infant Contact

Early close contact can facilitate the attachment process between parent and child. Although a delay in contact does not necessarily mean that attachment will be inhibited, additional psychologic energy may be necessary to achieve the same effect. To date, no scientific evidence has demonstrated that immediate contact after birth is essential for the human parent-child relationship.

Early skin-to-skin contact between the mother and newborn immediately after birth and during the first hour facilitates maternal affectionate and attachment behaviors (Moore, Anderson, & Bergman, 2009). The newborn is placed in the prone position on the mother’s bare chest; the baby and mother’s chest are covered with a warm, dry blanket and the infant’s head is covered with a cap to prevent heat loss. This practice promotes early and effective breastfeeding and increases breastfeeding duration. It is also associated with less infant crying, improved thermoregulation (especially in low-birth-weight infants), and improved cardiorespiratory stability in late preterm infants (Moore et al.).

Parents who are unable to have early contact with their newborn (e.g., the infant was transferred to the intensive care nursery) can be reassured that such contact is not essential for optimal parent-infant interactions. Otherwise, adopted infants would not form affectionate ties with their parents. Nurses need to stress that the parent-infant relationship is a process that occurs over time.

Extended Contact

Rooming-in is common in family-centered care. With this practice the infant stays in the room with the mother. In some facilities the newborn never leaves the mother’s presence; nursery nurses perform the initial assessment and care in the room with the parents. In other hospitals the infant is transferred to the postpartum or mother-baby unit from the transitional nursery (if the facility uses one) after showing satisfactory extrauterine adjustment. Nurses encourage the father or partner to participate in caring for the infant in as active a role as they desire. They can also encourage siblings and grandparents to visit and become acquainted with the infant. Whether the method of family-centered care is rooming-in, mother-baby or couplet care, or a family birth unit, mothers, their partners, and family members are equal and integral parts of the developing family.

Extended contact with the infant should be available for all parents but especially for those at risk for parenting inadequacies, such as adolescents and low-income women. Postpartum nurses need to consider and encourage activities that optimize family-centered care.

Communication Between Parent and Infant

The parent-infant relationship is strengthened through the use of sensual responses and abilities by both partners in the interaction. The nurse should keep in mind that cultural variations are often seen in these interactive behaviors.

The Senses

Touch, or the tactile sense, is used extensively by parents as a means of becoming acquainted with the newborn. Many mothers reach out for their infants as soon as they are born and the cord is cut. Mothers lift their infants to their breasts, enfold them in their arms, and cradle them. Once the infant is close, the mother begins the exploration process with her fingertips, one of the most touch-sensitive areas of the body. Within a short time she uses her palm to caress the baby’s trunk and eventually enfolds the infant. Similar progression of touching is demonstrated by fathers, partners, and other caregivers. Gentle stroking motions are used to soothe and quiet the infant; patting or gently rubbing the infant’s back is a comfort after feedings. Infants also pat the mother’s breast as they nurse. Both seem to enjoy sharing each other’s body warmth. Parents seem to have an innate desire to touch, pick up, and hold the infant (Fig. 22-4). They comment on the softness of the baby’s skin and note details of the baby’s appearance. As parents become increasingly sensitive to the infant’s like or dislike for different types of touch, they draw closer to the baby.

Touching behaviors by mothers vary in different cultural groups. For example, minimal touching and cuddling is a traditional Southeast Asian practice thought to protect the infant from evil spirits. Because of tradition and spiritual beliefs, women in India and Bali have practiced infant massage since ancient times.

Eye Contact

Parents repeatedly demonstrate interest in having eye contact with the baby. Some mothers remark that once their babies have looked at them, they feel much closer to them. Parents spend much time getting their babies to open their eyes and look at them. In the United States, eye contact appears to reinforce the development of a trusting relationship and is an important factor in human relationships at all ages. In other cultures, eye contact is perceived differently. For example, in Mexican culture, sustained direct eye contact is considered rude, immodest, and dangerous for some. This danger may arise from the mal de ojo (evil eye), resulting from excessive admiration. Women and children are thought to be more susceptible to mal de ojo (D’Avanzo, 2008).

As newborns become functionally able to sustain eye contact with their parents, they spend time in mutual gazing, often in the en face position, a position in which the parent’s and infant’s faces are approximately 20 cm apart and on the same plane (see Fig. 22-2). Nurses and physicians or midwives can facilitate eye contact immediately after birth by positioning the infant on the mother’s abdomen or breasts with the mother’s and the infant’s faces on the same plane. Dimming the lights encourages the infant’s eyes to open. To promote eye contact, instillation of prophylactic antibiotic ointment in the infant’s eyes can be delayed until the infant and parents have had some time together in the first hour after birth.

Voice

The shared response of parents and infants to each other’s voices is remarkable. Parents wait tensely for the first cry. Once that cry has reassured them of the baby’s health, they begin comforting behaviors. As the parents speak, the infant is alerted and turns toward them. Infants respond to higher-pitched voices and can distinguish their mother’s voice from others soon after birth.

Entrainment

Newborns move in time with the structure of adult speech, which is termed entrainment. They wave their arms, lift their heads, and kick their legs, seemingly “dancing in tune” to a parent’s voice. Culturally determined rhythms of speech are ingrained in the infant long before he or she uses spoken language to communicate. This shared rhythm also gives the parent positive feedback and establishes a positive setting for effective communication.

Biorhythmicity

Biorhythmicity refers to the infant being in tune with the mother’s natural rhythms. The mother’s heartbeat or a recording of a heartbeat can soothe a crying infant. One of the newborn’s tasks is to establish a personal biorhythm. Parents can help in this process by giving consistent loving care and using their infant’s alert state to develop responsive behavior and increase social interactions and opportunities for learning (Fig. 22-5). The more quickly parents become competent in child care activities, the more quickly they can direct their psychologic energy toward observing and responding to the communication cues the infant gives them.

Reciprocity and Synchrony

Reciprocity is a type of body movement or behavior that provides the observer with cues. The observer or receiver interprets those cues and responds to them. Reciprocity often takes several weeks to develop with a new baby. For example, when the newborn fusses and cries, the mother responds by picking up and cradling the infant; the baby becomes quiet and alert and establishes eye contact; the mother verbalizes, sings, and coos while the baby maintains eye contact. The baby then averts the eyes and yawns; the mother decreases her active response. If the parent continues to stimulate the infant, the baby may become fussy.

The term synchrony refers to the “fit” between the infant’s cues and the parent’s response. When parent and infant experience a synchronous interaction, it is mutually rewarding (Fig. 22-6). Parents need time to interpret the infant’s cues correctly. For example, the infant develops a specific cry in response to different situations such as boredom, loneliness, hunger, and discomfort. The parent may need assistance in interpreting these cries, along with trial and error interventions, before synchrony develops.

Parental Role After Birth

Adaptation involves a stabilizing of tasks, a coming to terms with commitments. Parents demonstrate growing competence in child care activities and become increasingly more attuned to their infant’s behavior. Typically, the period from the decision to conceive through the first months of having a child is termed the transition to parenthood.

Transition to Parenthood

Historically, the transition to parenthood was viewed as a crisis. The current perspective is that parenthood is a developmental transition rather than a major life crisis. The transition to parenthood is a time of disorder and disequilibrium, as well as satisfaction, for mothers and their partners. Usual methods of coping often seem ineffective during this time. Some parents are so distressed that they are unable to be supportive of each other. Because men typically identify their spouses as their primary or only source of support, the transition can be comparatively harder for the fathers. They often feel deprived when the mothers, who are also experiencing stress, cannot provide their usual level of support. Many parents are unprepared for the strong emotions such as helplessness, inadequacy, and anger that arise when dealing with a crying infant. However, parenthood allows adults to develop and display a selfless, warm, and caring side of themselves that may not be expressed in other adult roles.

For the majority of mothers and their partners the transition to parenthood is an opportunity rather than a time of danger. Parents try new coping strategies as they work to master their new roles and reach new developmental levels. As they work through the transition, they often find personal strength and resourcefulness.

Parental Tasks and Responsibilities

Parents need to reconcile the actual child with the fantasy and dream child. This process means coming to terms with the infant’s physical appearance, sex, innate temperament, and physical status. If the real child differs greatly from the fantasy child, some parents delay acceptance of the child. In some instances, they never accept the child.

Many parents know the sex of the infant before birth because of the use of ultrasound assessments. For those who do not have this information, disappointment over the baby’s sex can take time to resolve. The parents may provide adequate physical care but have difficulty in being sincerely involved with the infant until this internal conflict has been resolved. As one mother remarked, “I really wanted a boy. I know it is silly and irrational, but when they said, ‘She’s a lovely little girl,’ I was so disappointed and angry—yes, angry—I could hardly look at her. Oh, I looked after her okay, her feedings and baths and things, but I couldn’t feel excited. To tell the truth, I felt like a monster not liking my child. Then one day, she was lying there and she turned her head and looked right at me. I felt a flooding of love for her come over me, and we looked at each other a long time. It’s okay now. I wouldn’t change her for all the boys in the world.”

The normal appearance of the neonate—size, color, molding of the head, or bowed appearance of the legs—is startling for some parents. Nurses can encourage parents to examine their babies and to ask questions about newborn characteristics.

Parents need to become adept in the care of the infant, including caregiving activities, noting the communication cues given by the infant to indicate needs, and responding appropriately to the infant’s needs. Self-esteem grows with competence. Breastfeeding helps mothers believe that they are contributing in a unique way to the welfare of the infant. The parent may interpret the infant’s response to the parental care and attention as a comment on the quality of that care. Infant behaviors that parents interpret as positive responses to their care include being consoled easily, enjoying being cuddled, and making eye contact. Spitting up frequently after feedings, crying, and being unpredictable are often perceived as negative responses to parental care. Continuation of these infant responses that parents view as negative can result in alienation of parent and infant.

Some people view assistance, including advice by husbands, partners, wives, mothers, mothers-in-law, and health care professionals, as supportive. Others view advice as criticism or an indication of how inept these people judge the new parents to be. Criticism, real or imagined, of the new parents’ ability to provide adequate physical care, nutrition, or social stimulation for the infant can be devastating. By providing encouragement and praise for parenting efforts, nurses can bolster the new parents’ confidence.

Parents must establish a place for the newborn within the family group. Whether the infant is the firstborn or the last born, all family members must adjust their roles to accommodate the newcomer.

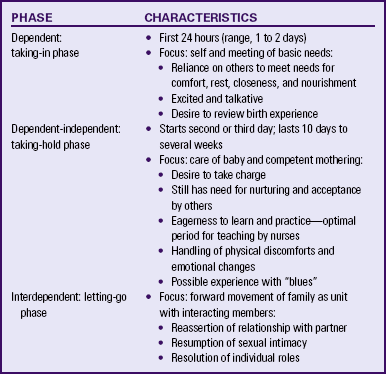

Becoming a Mother

Rubin (1961) identified three phases of maternal role attainment in which the mother adjusts to her parental role. These phases extend over the first several weeks and are characterized by dependent behavior, dependent-independent behavior, and interdependent behavior (Table 22-4). Rubin’s research was conducted when the length of stay in the hospital was for a longer period (3 to 5 or more days). With today’s early discharge, women seem to move through the phases faster.

TABLE 22-4

PHASES OF MATERNAL POSTPARTUM ADJUSTMENT

Source: Rubin, R. (1961). Basic maternal behavior. Nursing Outlook, 9(11), 683-686.

Mercer (2004) suggested that the concept of maternal role attainment, be replaced with becoming a mother to signify the transformation and growth of the mother’s identity. Becoming a mother implies more than attaining a role. It includes learning new skills and increasing her confidence in herself as she meets new challenges in caring for her child or children.

Mercer (2004) identified four stages in the process of becoming a mother: “[a] commitment, attachment to the unborn baby, and preparation for delivery and motherhood during pregnancy; [b] acquaintance/attachment to the infant, learning to care for the infant, and physical restoration during the first 2 to 6 weeks following birth; [c] moving toward a new normal; and [d] achievement of a maternal identity through redefining self to incorporate motherhood (around 4 months)” (Mercer & Walker, 2006, pp. 568-569). The time of achievement of the stages is variable and the stages may overlap. Achievement is influenced by mother and infant variables and the social environment.

Maternal sensitivity or maternal responsiveness is an important determinant of the maternal-infant relationship. It can be defined as the quality of a mother’s sensitive behaviors that are based on her awareness, perception, and responsiveness to infant cues and behaviors. Maternal sensitivity significantly influences the infant’s physical, psychologic, and cognitive development. Maternal qualities inherent to this sensitivity include awareness and responsiveness to infant cues, affect, timing, flexibility, acceptance, and conflict negotiation. Maternal sensitivity is dynamic and develops over time in a reciprocal give-and-take with the infant (Shin, Park, Ryu, & Seomun, 2008).

The transition to motherhood requires adjustment for the mother and her family. Disruption is inherent in that adjustment. Circumstances such as problems in postpartum recovery or giving birth to a high risk infant add to the disruption (Lutz & May, 2007).

Nelson (2003) identified two social processes in maternal transition. The primary process is engagement, which is making a commitment to being a mother, actively caring for her child, and experiencing his or her presence. The secondary process is experiencing herself as a mother, which leads to growth and transformation. During this process she must learn how to mother and adapt to a changed relationship with her partner, family, and friends. The woman must examine herself in relation to the past and her present and come to view herself as a mother. She must make important decisions such as whether to return to work and, if so, when.

Not all mothers experience the transition to motherhood in the same way. For some women becoming a mother entails multiple losses. For example, for a single woman a loss of the family of origin may occur when the family does not accept her decision to have the child. There may be loss of a relationship with the father of the baby, with friends, and with her own sense of self. Some women describe a loss of dreams that includes loss of job, financial security, and a future profession. Accompanying these losses is a loss of support.

Reality-based perinatal education programs are necessary to prepare mothers better and decrease their anxiety. Live classes allow time for questions to be answered and for mothers to lend support to one another. Mothers need to know that during the first months of parenthood it is common to feel overwhelmed and insecure and to experience physical and mental fatigue. They need to be assured that this situation is temporary and that 3 to 6 months may be needed to become comfortable in caregiving and in being a mother. Maternal support by professionals should not end with hospital discharge but extend over the next 4 to 6 months; long-term interventions tend to be more successful than one-time encounters. Nurses can advocate for the extension of such support services well into the postpartum period (Mercer & Walker, 2006).

During pregnancy and after birth nurses can discuss the usual postpartum concerns that mothers experience. They can provide anticipatory guidance on coping strategies, such as resting when the infant sleeps and planning with an extended family member or friend to do the housework for the first week or two after the baby is born. Once a mother is home, periodic telephone calls from a nurse who cared for her in the birth setting can provide the mother with an opportunity to vent her concerns and get support and advice from “her” nurse. Nurses should plan additional supportive counseling for first-time mothers inexperienced in child care, women whose careers had provided outside stimulation, women who lack friends or family members with whom to share delights and concerns, and adolescent mothers. When possible, postpartum home visits are included in the plan of care.

Postpartum “Blues”

The “pink” period surrounding the first day or two after birth, characterized by heightened joy and feelings of well-being, is often followed by a “blue” period. Approximately 50% to 80% of women of all ethnic and racial groups experience the postpartum blues or “baby blues.” During the blues, women are emotionally labile and often cry easily for no apparent reason. This lability seems to peak around the fifth day and subside by the tenth day. Other symptoms of postpartum blues include depression, a let-down feeling, restlessness, fatigue, insomnia, headache, anxiety, sadness, and anger. Biochemical, psychologic, social, and cultural factors have been explored as possible causes of postpartum blues; however, the cause remains unknown.

Whatever the cause, the early postpartum period appears to be one of emotional and physical vulnerability for new mothers, who are often psychologically overwhelmed by the reality of parental responsibilities. Mothers feel deprived of the supportive care they received from family members and friends during pregnancy. Some mothers regret the loss of the mother–unborn child relationship and mourn its passing. Still others experience a let-down feeling when labor and birth are complete. The majority of women experience fatigue after childbirth, which is compounded by the around-the-clock demands of the new baby. Postpartum fatigue increases the risk of postpartum depressive symptoms and can have a negative effect on maternal role attainment (Corwin & Arbour, 2007). To help mothers cope with postpartum blues, nurses can suggest various strategies (see the Teaching for Self-Management box).

A few questions on a discharge checklist can help mothers assess their level of “blues” and decide when to seek advice

from their nurse, nurse-midwife, or physician. Home visits and telephone follow-up calls by a nurse are important to assess the mother’s pattern of “blue” feelings and behavior over time.

Although the postpartum blues are usually mild and short lived, approximately 10% to 15% of women experience a more severe syndrome termed postpartum depression (PPD). Symptoms of PPD can range from mild to severe, with women having good days and bad days. Fathers can also experience PPD. Screening for PPD should be performed with both mothers and fathers. PPD can go undetected because new parents generally do not voluntarily admit to this kind of emotional distress out of embarrassment, guilt, or fear. Nurses need to include teaching about how to differentiate symptoms of the “blues” and PPD and urge parents to report depressive symptoms promptly if they occur (see Chapter 32).

Becoming a Father

Research on paternal adjustment to parenthood indicates that men go through predictable phases during their transition to parenthood as they seek to become involved fathers (Goodman, 2005). In the first phase, men enter parenthood with intentions of being an emotionally involved father with deep connections to the infant. Many desire to parent differently than their own fathers. The second phase is a time of confronting reality, when men realize that their expectations were inconsistent with the realities of life with a newborn during the first few weeks. During this period fathers experience intense emotions. Many acknowledge that their expectations were of limited value once they were immersed in the reality of parenthood. Feelings that often accompany this reality are sadness, ambivalence, jealousy, frustration at not being able to participate in breastfeeding, and an overwhelming desire to be more involved. Some men are surprised that establishing a relationship with the infant is more gradual than expected. Fathers often feel alone, having no one with whom to discuss their feelings during this time. Mothers are preoccupied with infant care and their own transition to parenting. However, some fathers are pleasantly surprised at the ease and fun of parenting and take an active role. Many fathers of breastfeeding infants find ways to be involved in infant care other than feeding. The third phase is working to create the role of involved father. The realities of the first few weeks at home with a newborn cause fathers to change their expectations, set new priorities, and redefine their role. They develop strategies for balancing work, their own needs, and the needs of their partner and infant. Men become increasingly more comfortable with infant care. During this time they may struggle for recognition and positive feedback from their partner, the infant, and others. They may feel excluded from support and attention by health care providers. The final phase of becoming an involved father is one of reaping rewards, the most significant being reciprocity from the infant, such as a smile. This phase typically occurs around 6 weeks to 2 months. Increased sociability of the infant enhances the father-infant relationship (Goodman) (Table 22-5).

TABLE 22-5

EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF THE INVOLVED FATHER ROLE

| PHASES | CHARACTERISTICS |

| Expectations and intentions | Desire for emotional involvement and deep connection with infant |

| Confronting reality | Dealing with unrealistic expectations, frustration, disappointment, feelings of guilt, helplessness, and inadequacy |

| Creating the role of involved father | Altering expectations, establishing new priorities, redefining role, negotiating changes with partner, learning to care for infant, increasing interaction with infant, struggling for recognition |

| Reaping rewards | Infant smile, sense of meaning, completeness and immortality |

Source: Goodman, J. (2005). Becoming an involved father of an infant. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing, 34(2), 190-200.

First-time fathers perceive the first 4 to 10 weeks of parenthood in much the same way that mothers do. It is a period characterized by uncertainty, increased responsibility, disruption of sleep, and inability to control time needed to care for the infant and reestablish the couple’s relationship. Fathers express concerns about decreased attention from their partners relative to their personal relationship, the mother’s lack of recognition of the father’s desire to participate in decision making for the infant, and limited time available to establish a relationship with the infant. These concerns can precipitate feelings of jealousy of the infant. The father should discuss his individual concerns and needs with the mother and become more involved with the infant. This effort can help alleviate feelings of jealousy.

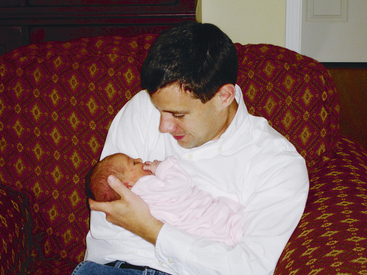

In North American culture neonates have a powerful effect on their fathers who become intensely involved with their babies. The term used for the father’s absorption, preoccupation, and interest in the infant is engrossment. Characteristics of engrossment include some of the sensual responses relating to touch and eye-to-eye contact that were discussed earlier and the father’s keen awareness of features both unique and similar to himself that validate his claim to the infant. An outstanding response is one of strong attraction to the newborn. Fathers spend considerable time “communicating” with the infant and taking delight in the infant’s response to them (Fig. 22-7). Fathers experience increased self-esteem and a sense of being proud, bigger, more mature, and older after seeing their baby for the first time.

FIG. 22-7 Engrossment. Father is absorbed in looking at his newborn. (Courtesy Kathryn Alden, Chapel Hill, NC.)

Fathers spend less time than mothers with infants, and their interactions with infants tend to be characterized by stimulating social play rather than caretaking. The variations in infant stimulation from both parents provide a wider social experience for the infant.

Fathers lack interpersonal and professional support compared with mothers and can feel excluded from antenatal appointments and antenatal classes. They need information and encouragement during pregnancy and in the postnatal period related to infant care, parenting, and relationship changes. During the postpartum hospital stay, nurses can arrange to teach infant care when the father is present and provide anticipatory guidance for fathers about the transition to parenthood. Separate prenatal and parenting classes and parenting support groups for fathers can provide them with an opportunity to discuss their concerns and have some of their needs met. Postpartum telephone calls and home visits by the nurse should include time for assessment of the father’s adjustment and needs (Deave, Johnson, & Ingram, 2008; Fletcher, Vimpani, Russell, & Sibbritt, 2008; Halle, Dowd, Fowler, Rissel, Hennessy, MacNevin, et al., 2008; St. John, Cameron, & McVeigh, 2005).

Adjustment for the Couple

The transition to parenthood brings about changes in the relationship between the mother and her partner. A strong, healthy marriage or couple relationship is the best foundation for parenthood, although even the best relationships are often shaken with the addition of a new baby. During the first few weeks after birth, parents experience a plethora of emotions. Even though they may feel an overwhelming love and a sense of amazement toward their newborn, they also feel a great responsibility. Even if the mother and her partner have been to prenatal classes, read books, or sought advice from family or friends, they are usually surprised by the realities of life with a new baby and the changes in their relationship (Deave et al., 2008). Because men and women experience pregnancy and birth differently, the expectation is that they will also vary in their adjustment to parenthood.

Common issues that couples face as they become parents include changes in their relationship with one another, division of household and infant care responsibilities, financial concerns, balancing work and parental responsibilities, and social activities. To assist new parents in their transition, nurses can encourage them during pregnancy and in the postpartum period to share personal expectations with each other and to assess their relationship periodically. Couples need to schedule time into their busy lives for one-on-one conversation and try to have regular “dates” or time apart from the infant. The mother and her partner need to express appreciation for one another and for their baby. Support from family, friends, and community health professionals should be identified early and used as needed during pregnancy and in the postpartum period and beyond. The couple who is willing to experiment with new approaches to their lifestyle and habits can find the transition to parenthood less difficult (Brotherson, 2007).

Resuming Sexual Intimacy

Nurses can provide opportunities for parents to discuss concerns and ask questions about resuming sexual intimacy. The couple may begin to engage in sexual intercourse during the second to fourth week after the baby is born. Some couples begin earlier, as soon as it can be accomplished without discomfort, depending on factors such as timing, amount of vaginal dryness, and breastfeeding status. Sexual intimacy enhances the adult aspect of the family, and the adult pair shares a closeness denied to other family members. Changes in a woman’s sexuality after childbirth are related to hormonal shifts, increased breast size, uneasiness with a body that has yet to return to a prepregnant size, chronic fatigue related to sleep deprivation, and physical exhaustion. Many new fathers speak of feeling alienated when they observe the intimate mother-infant relationship, and some are frank in expressing feelings of jealousy toward the infant. The resumption of sexual intimacy seems to bring the parents’ relationship back into focus. Before and after birth, nurses should review with new parents their plans for other pregnancies and their preferences for contraception.

Infant-Parent Adjustment

It has long been recognized that newborns participate actively in shaping their parents’ reaction to them. Behavioral characteristics of the infant influence parenting behaviors. The infant and the parent each have unique rhythms, behaviors, and response styles that are brought to every interaction. Infant-parent interactions can be facilitated in any of three ways: (1) modulation of rhythm, (2) modification of behavioral repertoires, and (3) mutual responsivity. Nurses can teach parents about these three aspects of infant-parent interaction through discussions, written materials, and videotapes describing infant capabilities. A creative approach is to videotape the parent-infant pair during an interaction and then use the individualized tape to discuss the pair’s rhythm, behavioral repertoire, and responsivity.

Rhythm: To modulate rhythm, both parent and infant must be able to interact. Therefore the infant must be in the alert state, one of the most difficult of the sleep-wake states to maintain. The alert state (Fig. 22-8) occurs most often during a feeding or in face-to-face play. The parent must work hard to help the infant maintain the alert state long enough and often enough for interactions to take place. The en face position is usually assumed (Fig. 22-8, D). Multiparous mothers in particular are very sensitive and responsive to the infant’s feeding rhythms.

Mothers learn to reserve stimulation for pauses in sucking activity and not to talk or smile excessively while the infant is sucking because the infant will stop feeding to interact with her. With maturity the infant can sustain longer interactions by modulating activity rhythms, that is, limb movement, sucking, gaze alternation, and habituation. Meanwhile, the parent becomes more attuned to the infant’s rhythms and learns to modulate the rhythms, facilitating a rhythmic turn-taking interaction.

Behavioral Repertoires: Both the infant and the parent have a repertoire of behaviors they can use to facilitate interactions. Fathers and mothers engage in these behaviors depending on the extent of contact and caregiving of the infant.

The infant’s behavioral repertoire includes gazing, vocalizing, and facial expressions. The infant is able to focus and follow the human face from birth and also is able to alternate the gaze voluntarily, looking away from the parent’s face when understimulated or overstimulated (Fig. 22-8, F). One of the key responses for the parents to learn is to be sensitive to the infant’s capacity for attention and inattention. Developing this sensitivity is especially important when interacting with preterm infants.

Body gestures form a part of the infant’s “early language.” Babies greet parents with waving hands (Fig. 22-8, E) or a reaching out of hands. They can raise an eyebrow or soften their expression to elicit loving attention. Game playing can stimulate them to smile or laugh. Pouting or crying, arching of the back, and general squirming usually signal the end of an interaction.

The parents’ repertoire includes various types of interactive behaviors such as constantly looking at the infant and noting the infant’s response. New parents often remark that they are exhausted from looking at the baby and smiling. Adults also “infantilize” their speech to help the infant “listen.” They do this by slowing the tempo, speaking loudly and rhythmically, and emphasizing key words. Phrases are repeated frequently. Infantilizing does not mean using “baby talk,” which involves distortion of sounds.

To communicate emotions to the infant, parents often use facial expressions such as slow and exaggerated looks of surprise, happiness, and confusion. Games such as “peek-a-boo” and imitation of the infant’s behaviors are other means of interaction. For example, if the baby smiles, so does the parent; if the baby frowns, the parent responds in kind.

Responsivity: Contingent responses (responsivity) are those that occur within a specific time and are similar in form to a stimulus behavior. The adult has the feeling of having an influence on the interaction. Infant behaviors such as smiling, cooing, and sustained eye contact, usually in the en face position, are viewed as contingent responses. The infant’s responses act as rewards to the initiator and encourage the adult to continue with the game when the infant responds positively. When the adult imitates the infant, the infant appears to enjoy it. A progression occurs in the types of behaviors that parents present for the baby to imitate; for example, in early interactions, the parent will grimace rather than laugh, which is in keeping with the infant’s developmental level. Such “turnabout” behaviors sustain interactions and promote harmony in the relationship.

Diversity in Transitions to Parenthood

Various factors, including age, social networks, socioeconomic conditions, and personal aspirations for the future, influence how parents respond to the birth of a child. Cultural beliefs and practices also affect parenting behaviors. Factors that are recognized to increase the risk of parenting problems include age (adolescent or older than 35 years), lesbian parenting, social support, culture, socioeconomic conditions, and personal aspirations.

Age

Maternal age has a definite effect on the transition to parenting. The mother, fetus, and newborn are at highest risk when the mother is an adolescent or older than 35 years.

The Adolescent Mother

Although becoming a parent is biologically possible for the adolescent female, her egocentricity and concrete thinking often interfere with the ability to parent effectively. Adolescent mothers are more likely to give birth to preterm and/or low-birth-weight infants. Mortality rates are higher among infants of adolescent mothers. This can be related to inherent problems associated with preterm birth or other conditions, but it is also influenced by the mother’s inexperience, lack of knowledge, and immaturity. Nevertheless, in most instances, with adequate support and developmentally appropriate teaching, adolescents can learn effective parenting skills. Strong social and functional support promotes positive outcomes for adolescent mothers.

Contrary to popular beliefs related to the detrimental effects of adolescent pregnancy, research evidence suggests that the life course for adolescent mothers is similar to that of their socioeconomic peers (Beers & Hollo, 2009). In some families or communities, adolescent parenthood is considered a normal or positive life event. Even so, adolescent pregnancy and parenting are important public health concerns.

The transition to parenthood can be difficult for adolescent parents. Because many adolescents have their own unmet developmental needs, coping with the developmental tasks of parenthood is often difficult. Some young parents experience difficulty accepting a changing self-image and adjusting to new roles related to the responsibilities of infant care. Adolescent mothers are at increased risk for postpartum depression; this is often associated with a lack of social support and poor relations with their partner (Beers & Hollo, 2009).

As adolescent parents move through the transition to parenthood, they can feel “different” from their peers, excluded from “fun” activities, and prematurely forced to enter an adult social role. The conflict between their own desires and the infant’s demands, in addition to the low tolerance for frustration that is typical of adolescence, further contribute to the normal psychosocial stress of childbirth and parenting. Maintaining a relationship with the baby’s father is beneficial for the teen mother and her infant, although adolescent pregnancy often heralds the departure of the young father from the relationship (Herrman, 2008).

Adolescent mothers provide warm and attentive physical care; however, they use less verbal interaction than older parents, and adolescents tend to be less responsive and to interact less positively with their infants than older mothers. Interventions emphasizing verbal and nonverbal communication skills between mother and infant are important. Such intervention strategies must be concrete and specific because of the cognitive level of adolescents. Although some observers suggest that some adolescents may use more aggressive behaviors, a higher than normal incidence of child abuse has not been documented. In comparison to older mothers, teenage mothers have a limited knowledge of child development. They tend to expect too much of their infants too soon and often characterize their infants as being fussy. This limited knowledge may cause teenagers to respond to their infants inappropriately.

Many young mothers pattern their maternal role on what they themselves experienced. Therefore, nurses need to determine the type of support that people close to the young mother are able and prepared to give, as well as the kinds of community assistance available to supplement this support. Many teen mothers can identify a source of social support, with the predominant source being their own mothers.

The need for continued assessment of the new mother’s parenting abilities during this postbirth period is essential. Continued support is facilitated by involving the grandparents and other family members, as well as through home visits and group sessions for discussion of infant care and parenting problems. Community-based programs for pregnant adolescents and adolescent parents improve access to health care, education, and other support services. Serious problems can be prevented through outreach programs concerned with self-management, parent-child interactions, infant development, child injuries, and failure to thrive. As the adolescent performs her mothering role within the framework of her family, she may need to address dependency versus independency issues. The adolescent’s family members also need help adapting to their new roles. Some mothers and fathers of adolescents feel they are too young and unprepared to be grandparents.

The Adolescent Father

The adolescent father and mother face immediate developmental crises, which include completing the developmental tasks of adolescence, making a transition to parenthood, and sometimes adapting to marriage. These transitions are often stressful. The nurse can initiate interaction with the adolescent father if he is present during prenatal visits or if he is with his partner during labor and birth. During the hospital stay the nurse can include the adolescent father in teaching sessions about infant care and parenting. The nurse can ask him to be present during postpartum home visits and to accompany the mother and the baby to well-baby checkups at the clinic or pediatrician’s office. With the adolescent mother’s agreement the nurse may contact the father directly. Adolescent fathers need support to discuss their emotional responses to the pregnancy, birth, and fatherhood. The nurse needs to be aware of the father’s feelings of guilt, powerlessness, or bravado because these feelings may have negative consequences for both the parents and the child. Counseling of adolescent fathers needs to be reality oriented and should include topics such as finances, child care, parenting skills, and the father’s role in the parenting experience. Teenage fathers also need to know about reproductive physiology and birth control options, as well as sex practices that lower the risk of pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections.

The adolescent father may continue to be involved in an ongoing relationship with the young mother and his baby. In those instances he plays an important role in the decisions about child care and raising the child. He may need help to develop realistic perceptions of his role as “father to a child” and is encouraged to use coping mechanisms that are not harmful to his own, his partner’s, or his child’s well-being. The nurse enlists support systems, parents, and professional agencies on his behalf.

Maternal Age Older Than 35 Years

Women older than 35 years have always continued their childbearing either by choice or because of a lack of or a failure of contraception during the perimenopausal years. Added to this group are women who have postponed pregnancy because of careers or other reasons, as well as women of infertile couples who finally become pregnant with the aid of technologic advances.

Support from partners aids in the adjustment of older mothers to changes involved in becoming a parent and seeing themselves as competent. Support from other family members and friends is also important for positive self-evaluation of parenting, a sense of well-being and satisfaction, and help in dealing with stress. Women of advanced maternal age can experience social isolation. Older mothers may have less family and social support than younger mothers. They are less likely to live near family, and their own parents, if still living, can be unable to provide assistance or support because of age or health issues. Mothers of advanced maternal age are often caught in the “sandwich generation,” taking on responsibility for care of aging parents while parenting young children. Social support may be lacking because their peers are probably busy with their careers and have limited time to help. Their friends are likely to have older children and have less in common with the new mother (Suplee, Dawley, & Bloch, 2007).

Changes in the sexual aspect of a relationship can create stress for new midlife parents. Mothers report that it is difficult to find time and energy for a romantic rendezvous. They attribute much of this difficulty to the reality of caring for an infant, but the decreasing libido that normally accompanies getting older also contributes.

Work and career issues are sources of conflict for older mothers. Conflicts emerge over being disinterested in work, worrying about giving enough attention to work with the distractions of a new baby, and anticipating what returning to work will entail. Child care is a major factor in causing stress about work.

Another major issue for older mothers with careers is the perception of loss of control. Mothers older than 35 years, when compared with younger mothers, are at a different stage in their careers, having attained high levels of education, career, and income. The loss of control experienced when going from the consistency of a work role to the inconsistency of the parent role comes as a surprise to many older women. Helping the older mother have realistic expectations of herself and of parenthood is essential.

New mothers who are also perimenopausal may have difficulty distinguishing fatigue, loss of sleep, decreased libido, or other physiologic symptoms as the causes of the change in their sex lives. Although many women view menopause as a natural stage of life, for midlife mothers, this cessation of menstruation coincides with the state of parenthood. The changes of midlife and menopause can add more emotional and physical stress to older mothers’ lives because of the time- and energy-consuming aspects of raising a young child.

Paternal Age Older Than 35 Years

Although many older fathers describe their experience of midlife parenting as wonderful, they also recognize drawbacks. Positive aspects of fatherhood in older years include increased love and commitment between the two parents, a reinforcement of why one married in the first place, a feeling of being complete, experiencing of “the child” again in oneself, more financial stability than in younger years, and more freedom to focus on parenting rather than on career. A common drawback of midlife parenting is the change that it brings about in the relationships with their partners.

Parenting in the Lesbian Couple

The transition to parenting for lesbian couples is unique in that there are two women with maternal status, one who gave birth and the other who may be referred to as “the other mother,” “nonbiologic mother,” “co-parent,” or other term preferred by the couple. It is important for health care providers to determine the couple’s preference about how they wish to be identified (McManus, Hunter, & Renn, 2006).

Among lesbian couples the decision to conceive is intentional. There are several methods to achieve a pregnancy. One woman can be artificially inseminated and conceive a child who is genetically related to her. The fertilized egg of one partner can be implanted into the uterus of the other who carries the pregnancy. Alternatively, one woman can be implanted with the fertilized egg from a donor so that the child is not biologically related to either partner. Research evidence suggests that the birth mother has chosen to be the one to carry the baby because of a greater desire to experience the pregnancy and birth and to be genetically related to the child. Other factors that influence the decision are age, health, infertility, and career considerations (Goldberg, 2006).

Health care providers demonstrate a variety of reactions to lesbian couples ranging from rejection and exclusion to complete acceptance and inclusion. Judgmental attitudes, confusion, or lack of understanding can affect the quality of care provided to these families. Although the traditional roles of the mother and father in heterosexual relationships are well recognized, the role of the lesbian co-parent can be questioned, misunderstood, and ignored by society and by health care providers. Intentionally or accidentally, health care providers can exclude partners or fail to acknowledge their roles in pregnancy, birth, and parenting (McManus et al., 2006; Renaud, 2007).

Integration of the nonchildbearing partner into care includes offering opportunities afforded male partners of heterosexual women such as “cutting the cord” and rooming in with the mother and baby during hospitalization. An option not available to male partners is to actually breastfeed the infant. The nonchildbearing female partner can stimulate milk production through induced lactation using medications and regular pumping. A supplemental feeding device containing expressed breast milk or formula can be used to provide additional milk to the breastfeeding infant. Women who choose not to induce lactation yet desire to have the breastfeeding experience can put the baby to breast using a supplemental feeding device (McManus et al., 2006; Riordan & Wambach, 2010).

Similar to heterosexual parents, lesbian couples face challenges in adjusting to life with a new baby. After birth the birth mother tends to be the one most responsible for child care as she is likely to be working fewer hours than her partner. Couples who are intentional about creating opportunities for bonding between the baby and the mother who did not give birth report success in minimizing the effects of biologic motherhood (Goldberg & Perry-Jenkins, 2007). Tensions can arise between the partners in relation to their roles. For example, the birth mother can feel that she has a greater role in parenting because she considers herself more primary. This can be compounded by the lack of a formal, recognized relationship of the co-parent to the infant and the issues surrounding her legal rights in relation to her partner and the infant (McManus et al., 2006).

Lesbian couples face strong social sanctions regarding pregnancy and parenting. Their families may not have resolved the initial dismay and guilt over learning of their daughters’ homosexuality, or they may disagree with the lesbian couple’s decision to conceive and be parents. Lesbian parents deal with public ignorance, social and legal invisibility, and the lack of biologic connection to the child by using various techniques. These techniques include carefully planning and accomplishing their transition to parenthood, displaying public acts of equal mothering, sharing parenting at home, establishing a distinct parenting role within the family, and supporting each partner’s sense of identity as a mother. In situations in which family support is limited or absent the nurse can help lesbian couples locate supportive social groups, lesbian or heterosexual.

Social Support

Social support is strongly related to positive adaptation by new parents, including adolescent parents, during the transition to parenthood. Social support is multidimensional and includes the number of members in a person’s social network, types of support, perceived general support, actual support received, and satisfaction with support available and received. The type and satisfaction of support seems to be more important than the total number of support network members.

Across cultural groups, families and friends of new parents form an important dimension of the parent’s social network. Through seeking help within the social network, new mothers learn culturally valued practices and develop role competency.

Social networks provide a support system on which parents can rely for assistance, but they also can be a source of conflict. Sometimes a large network can cause problems because it results in conflicting advice that comes from numerous people. Grandparents or in-laws are most appreciated when they assist with household responsibilities and do not intrude into the parents’ privacy or judge them critically.

Because of the extent of restructuring and reorganization that occurs in a family with the birth of another child, the mothers’ moods and fatigue in the postpartum period can be helped more by situation-specific support from family and friends than by general support. General support addresses feeling loved, respected, and valued. Situation-specific support relates to practical concerns such as physical needs and child care. For example, the practical support of a grandparent bathing the infant can help lessen a second-time mother’s feelings of loss by providing her time to be with her firstborn child.

Culture

Cultural beliefs and practices are important determinants of parenting behaviors. Culture influences the interactions with the baby, as well as the parents’ or the family’s caregiving style. For example, the provision for a period of rest and recuperation for the mother after birth is prominent in several cultures. Asian mothers must remain at home with the baby up to 30 days after birth and are not supposed to engage in household chores, including care of the baby. Many times the grandmother takes over the baby’s care immediately, even before discharge from the hospital. Jordanian mothers have a 40-day lying-in after birth during which their mothers or sisters care for the baby. Japanese mothers rest for the first 2 months after childbirth. Hispanics practice an intergenerational family ritual, la cuarentena. For 40 days after birth the mother is expected to recuperate and get acquainted with her infant. Traditionally this process involves many restrictions concerning food (spicy or cold foods, fish, pork, and citrus are avoided; tortillas and chicken soup are encouraged), exercise, and activities, including sexual intercourse. Many women avoid bathing and washing their hair. Traditional Hispanic husbands do not expect to see their wives or infants until both have been cleaned and dressed after birth. La cuarentena incorporates individuals into the family, instills parental responsibility, and integrates the family during a critical life event (D’Avanzo, 2008).

All cultures place importance on desiring and valuing children. In Asian families, children are a source of family strength and stability, are perceived as wealth, and are objects of parental love and affection. Infants are almost always given an affectionate “cradle” name that is used during the first years of life; for example, a Filipino girl might be called “Ling-Ling” and a boy “Bong-Bong.”

Differing cultural values can influence parents’ interactions with health care professionals. For example, Asians are taught to be humble and obedient; to be outspoken is frowned upon. They are brought up to refrain from questioning authority figures (e.g., a nurse), to avoid confrontation, and to respect the yin/yang balance in nature. Because of these learned values, an Asian mother might not confront the nurse about the length of time taken to receive the medication requested for her episiotomy pain. A mother may nod and say, “Yes,” in response to the nurse’s directions for using an iced sitz bath but then will not use the sitz bath. The “yes,” in this case, is a gesture of courtesy, meaning, “I’m listening”; it is not an indication of agreement to comply. The mother does not use the iced sitz bath because of her traditional avoidance of bathing and cold after birth. Because not all members of a cultural group adhere to traditional practices, it is necessary to validate which cultural practices are important to individual parents.

Knowledge of cultural beliefs can help the nurse make more accurate assessments and diagnoses of observed parenting behaviors. For example, nurses may become concerned when they observe cultural practices that appear to reflect poor maternal-infant bonding. Algerian mothers may not unwrap and explore their infants as part of the acquaintance process because in Algeria, babies are wrapped tightly in swaddling clothes to protect them physically and psychologically (D’Avanzo, 2008). The nurse may observe a Vietnamese woman who gives minimal care to her infant but refuses to cuddle or further interact with her baby. This apparent lack of interest in the newborn is this cultural group’s attempt to ward off “evil spirits” and actually reflects an intense love and concern for the infant. An Asian mother might be criticized for almost immediately relinquishing the care of the infant to the grandmother and not even attempting to hold her baby when it is brought to her room. However, in Asian extended families, members show their support for a new mother’s rest and recuperation by assisting with the care of the baby. Contrary to the guidance that is sometimes given to mothers in the United States about “nipple confusion,” a mix of breastfeeding and bottle-feeding is standard practice for Japanese mothers. This tradition is related to concern for the mother’s rest during the first 2 to 3 months and does not usually lead to problems with lactation; breastfeeding is widespread and successful among Japanese women.

Cultural beliefs and values give perspective to the meaning of childbirth for a new mother. Nurses can provide an opportunity for a new mother to talk about her perception of the meaning of childbearing. In helping new families adjust to parenthood, nurses must provide culturally sensitive care by following principles that facilitate nursing practice within transcultural situations.

Socioeconomic Conditions

Socioeconomic conditions often determine access to available resources. Parents whose economic condition is made worse with the birth of each child and who are unable to use an effective method of fertility management can find childbirth complicated by concern for their own health and a sense of helplessness. Mothers who are single, separated, or divorced from their husbands or without a partner, family, and friends can view the birth of a child with dread. Serious financial problems may negatively affect mothering behaviors. Similarly, fathers who are overwhelmed with financial stresses may lack effective parenting skills and behaviors.

Personal Aspirations

For some women, parenthood interferes with or blocks plans for personal freedom or career advancement. Unresolved resentment will affect caregiving activities and adjustment to parenting. This situation may result in indifference and neglect of the infant or in excessive concerns; the mother may set impossibly high standards for her own behavior or the child’s performance.

Nursing interventions include providing opportunities for mothers to express their feelings freely to an objective listener, to discuss measures to permit personal growth, and to learn about the care of their infant. Referring the woman to a support group of other mothers “in the same situation” may also be helpful.

Nurses can be proactive in influencing changes in work policies related to maternity and paternity leaves, varying models of work sharing and family-friendly work environments. Some corporations already structure their worksites to support new mothers (e.g., by providing on-site daycare facilities and lactation rooms).

Parental Sensory Impairment

In early interactions between the parent and child, each one uses all senses—sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell—to initiate and sustain the attachment process. A parent who has an impairment of one or more of the senses needs to maximize use of the remaining senses. Mothers with disabilities tend to value the importance of performing parenting tasks in the perceived culturally usual way.

Visually Impaired Parent

Visual impairment alone does not seem to have a negative effect on parents’ early parenting experiences. These parents, just as sighted parents, express the wonders of parenthood and encourage other visually impaired persons to become parents.

Although visually impaired parents initially feel a pressure to conform to traditional, sighted ways of parenting, they soon adapt these ways and develop methods better suited to themselves. Examples of activities that visually impaired parents perform differently include preparation of the infant’s nursery, clothes, and supplies. Some parents put an entire clothing outfit together and hang it in the closet rather than keeping items separate in drawers. Some develop a labeling system for the infant’s clothing and put diapering, bathing, and other care supplies where they will be easy to locate. A strength that visually impaired parents have is a heightened sensitivity to other sensory outputs. Visually impaired parents can tell when their infant is facing them because they notice the baby’s breath on their faces.

One of the major difficulties that visually impaired parents experience is the skepticism, open or hidden, of health care professionals. Visually impaired people sense reluctance on the part of others to acknowledge that they have a right to be parents. All too often, nurses and physicians lack the experience to deal with the childbearing and childrearing needs of visually impaired parents, as well as parents with other disabilities, such as the hearing impaired, physically impaired, and mentally challenged. The nurse’s best approach is to assess the parents’ capabilities and to use that information as a basis for making plans to assist the parent, often in much the same way as for a parent without impairments. Visually impaired mothers have made suggestions for providing care for women such as themselves during childbearing (Box 22-2). Such approaches can help avoid a sense of increased vulnerability on the parent’s part.

Eye contact is important in U.S. culture. With a parent who is visually impaired, this critical factor in the parent-child attachment process is obviously missing. However, the blind parent, who may never have experienced this method of strengthening relationships, does not miss it. The infant will need other sensory input from that parent. An infant looking into the eyes of a parent who is blind may be unaware that the eyes are unseeing. Other people in the newborn’s environment can also participate in active eye-to-eye contact to supply this need. A problem may arise, however, if the visually impaired parent has little facial expression. The infant, after making repeated unsuccessful attempts to engage in face play with the mother, will abandon the behavior with her and intensify it with the father or other people in the household. Nurses can provide anticipatory guidance regarding this situation and help the mother learn to nod and smile while talking and cooing to the infant.

Hearing-Impaired Parent

A parent who has a hearing impairment faces challenges in caregiving and parenting, particularly if the deafness dates from birth or early childhood. Whether one or both parents are hearing impaired, they are likely to have established an independent household. Devices that transform sound into light flashes can be fitted into the infant’s room to permit immediate detection of crying. Even if the parent is not speech trained, vocalizing can serve as both a stimulus and a response to the infant’s early vocalizing. Deaf parents can provide additional vocal training by use of recordings and television so that from birth the child is aware of the full range of the human voice. Young children acquire sign language readily, and the first sign used is as varied as the first word.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 requires that hospitals and other institutions receiving funds from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services use various communication techniques and resources with the deaf, including having staff members or certified interpreters who are proficient in sign language. For example, provision of written materials with demonstrations and having nurses stand where the parent can read their lips (if the parent practices lip reading) are two techniques that can be used. A creative approach is for the nursing unit to develop videos in which information on postpartum care, infant care, and parenting issues is signed by an interpreter and spoken by a nurse. A videotape in which a nurse signs while speaking would be ideal. With the advent of the Internet, many resources are available to deaf parents. Box 22-3 lists suggestions for working with hearing-impaired parents.

Sibling Adaptation

Because the family is an interactive, open unit, the addition of a new family member affects everyone in the family. Siblings have to assume new positions within the family hierarchy. Parents often face the task of caring for a new child while not neglecting the others and need to distribute their attention equitably. When the newborn was born prematurely or has special needs, this task can be difficult.

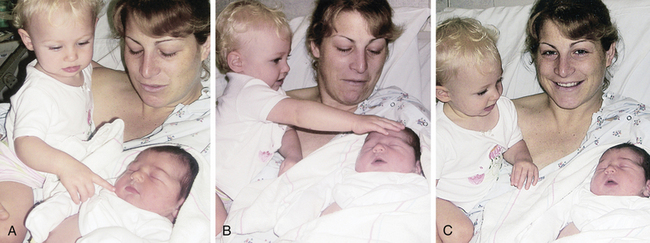

Reactions of siblings result from temporary separation from the mother, changes in the mother’s or father’s behavior, or the infant coming home. Positive behavioral changes of siblings include interest in and concern for the baby (Fig. 22-9) and increased independence. Regression in toileting and sleep habits, aggression toward the baby, and increased seeking of attention and whining are examples of negative behaviors.

FIG. 22-9 First meeting. Sister with mother during first meeting with new sibling. A, First tentative touch with fingertip. B, Relationship is more secure; touching with whole hand is now okay. C, Smiles indicate acceptance. (Courtesy Sara Kossuth, Los Angeles, CA.)

The parents’ attitudes toward the arrival of the baby can set the stage for the other children’s reactions. Because the baby absorbs the time and attention of the important people in the other children’s lives, jealousy (sibling rivalry) is common once the initial excitement of having a new baby in the home is over.

Parents, especially mothers, spend much time and energy promoting sibling acceptance of a new baby. Participating in sibling preparation classes makes a difference in the ability of mothers to cope with sibling behavior. Older children are actively involved in preparing for the infant, and this involvement intensifies after the birth of the child. Parents have to manage the feeling of guilt that the older children are being deprived of parental time and attention and monitor the behavior of older children toward the more vulnerable infant and divert aggressive behavior. Box 22-4 presents strategies that parents have used to facilitate acceptance of a new baby by siblings.

Siblings demonstrate acquaintance behaviors with the newborn. The acquaintance process depends on the information given to the child before the baby is born and on the child’s cognitive development level. The initial behaviors of siblings with the newborn include looking at the infant and touching the head (see Fig. 22-9). The initial adjustment of older children to a newborn takes time, and parents should allow children to interact at their own pace rather than forcing them to interact. To expect a young child to accept and love a rival for the parents’ affection assumes an unrealistic level of maturity. Sibling love grows as does other love, that is, by being with another person and sharing experiences. The bond between siblings involves a secure base in which one child provides support for the other, is missed when absent, and is looked to for comfort and security.

Grandparent Adaptation