Mental Health Disorders and Substance Abuse in Pregnancy

• Delineate emotional complications during pregnancy, including management of anxiety disorders and mood disorders.

• Examine substance abuse during pregnancy, including dual diagnosis, prevalence, risk factors, legal considerations, treatment programs, barriers to treatment, and care management.

• Identify postpartum emotional complications, including incidence, risk factors, signs and symptoms, and management.

• Evaluate the role of the nurse in assessing and managing care of women with emotional complications during pregnancy and postpartum.

• Develop a nursing care plan for a woman with an anxiety disorder, such as panic disorder.

Management of mental health disorders takes place primarily in community settings. Compared with births in the general non–mentally ill population, women with mental illness who give birth have a higher risk of obstetric complications (Thornton, Guendelman, & Hosang, 2009). However, mentally ill women who were treated were at lower risk than women not treated. Twelve-month prevalence rates for women with psychiatric disorders range from 22.6 (anxiety disorders) to 14.1% (mood disorders) to 6.6 (substance abuse) (Hendrick, 2006). In a cross-national study of the association between gender and mental disorders, the World Health Organization reported that in all age cohorts and countries, women had more anxiety and mood disorders than men; however, men had more substance disorders (Seedat, Scott, Angermeyer, Berglund, Bromet, Brugha, et al., 2009). The symptoms and treatment can complicate pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period.

Mental Health Disorders During Pregnancy

Women are at the greatest risk for developing a psychiatric disorder between the ages of 18 and 45 years—the childbearing years (Hendrick, 2006). Women who have serious mental disorders may be engaging in sexual activities that can result in pregnancy. The pregnant woman may have a history of disorder in mood, anxiety, substance use, schizophrenia, personality, or development. Assessment throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period is critical to the mother’s and the baby’s health. With a history or current symptoms of mental illness, referral to a mental health specialist for evaluation is recommended. Mental health disorders have implications for the pregnant woman, the fetus, the newborn, and the entire family.

Mood Disorders

Women who are being treated for depression may become pregnant, either intentionally or accidentally. In a review of 21 research articles, the prevalence of depression during pregnancy was cited as being 7.4% during the first trimester, 12.8% during the second trimester, and 12% during the third trimester (Bennett, Einarson, Toddio, Koren, & Einarson, 2004). Of all pregnant women treated for depression, approximately one third have a first occurrence during pregnancy (Pigarelli, Kraus, & Potter, 2005). These findings dispel the myth that pregnancy is a “pleasant and happy event” for all women.

Mood disorders are defined as disorders that have as their dominant feature a disturbance in the prevailing emotional state. To be diagnosed with major depression, at least five of the following signs or symptoms must be present nearly every day: depressed mood, often with spontaneous crying; markedly diminished interest in all activities; insomnia or hypersomnia; weight changes (increases or decreases); psychomotor retardation or agitation; fatigue or loss of energy; feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt; diminished ability to concentrate; and suicidal ideation with or without a suicidal plan (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). The 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale accurately identifies depression in pregnant and postpartum women (Sadock, Sadock, & Ruiz, 2009).

Collaborative Care

Medical management of depression is usually a combination of antidepressants and cognitive-behavioral or interpersonal psychotherapy. Self-help strategies such as exercise, respite from caregiving, self-help groups, and making time for one’s self can be helpful. Nursing strategies include educating the woman about depression as an illness, about treatment success, and about antidepressant medications. For the woman who refuses medications during pregnancy, the nurse should discuss alternative treatments and respect her choice. The nurse also can be effective by maintaining a caring relationship, which includes being hopeful. The nurse can ask about a time when the woman was coping well and how she was able to combat the depression then.

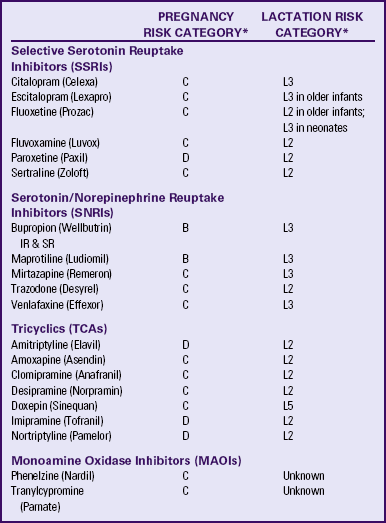

Antidepressant Medications: No consensus exists regarding safety in the use of antidepressant medications with pregnant women. To date, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved any psychotropic medication for use during pregnancy. None of these medications is rated as an FDA Category A drug (controlled studies show no risk to the fetus) (see Table 32-1 for FDA pregnancy risk categories of most common antidepressant medications). The commonly used antidepressant drugs are often divided into four groups: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

TABLE 32-1

B = Animal studies have not shown fetal risk, but no controlled studies in pregnant women or animal studies showed adverse effect that was not confirmed in controlled studies in women in first trimester—no risk in later trimesters.

C = Animal studies show adverse effects on fetus and no controlled studies in pregnant women or no studies available.

D = Positive evidence of human fetal risk.

L2 = Drug studied in limited number of breastfeeding women with no adverse effects in infant or evidence is remote.

L3 = No controlled studies or studies show minimal nonthreatening effects.

L5 = Contraindicated because studies have shown significant and documented risk to infant.

IR, Intermediate release; SR, sustained release.

∗Sources: Hale, T. (2004). Medications and mother’s milk (11th ed.). Amarillo, TX: Pharmasoft; Schatzberg, A., Cole, J., & DeBattista, C. (2007). Manual of clinical psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Amitriptyline, imipramine, and nortriptyline (TCAs), along with paroxetine (an SSRI) and MAOIs are the most risky antidepressant medications (Schatzberg, Cole, & DeBattista, 2007). Because the majority of women are not aware of their pregnancy until at least 6 weeks of gestation, psychotropic medications may not be discontinued until after the period of greatest potential risk to the fetus has passed. Risk-benefit analyses of depression treatment options should consider the potential risks that may accrue if depressive episodes go untreated in the pregnant woman (Sadock et al., 2009). Risks include severe psychologic distress, suicide, financial hardships, and inability to plan for transition to parenthood. Most women who discontinue antidepressant medications relapse during pregnancy. The majority of relapses occur in the first trimester, and relapse is more prevalent in women with histories of more chronic depression (Schatzberg et al.). Because randomized clinical trial data regarding the relative safety of available psychotropic medications are unavailable, clinical decision making is particularly complicated (Sadock et al.).

Concerns regarding the safety of antidepressant medications are common. However, untreated depression may also cause adverse effects on the developing fetus and neonate, such as preterm birth, small head circumference, and low Apgar scores. For women with a diagnosis of major depression, treatment with antidepressants is appropriate. Depression in the first trimester, if it is not moderate to severe, may be treated by supportive measures such as psychotherapy. Several studies have found interpersonal psychotherapy effective in significantly reducing depression during pregnancy (Sadock et al., 2009). Use of antidepressants, including SSRIs, is indicated for vegetative signs accompanying a major depressive episode that do not resolve with supportive intervention. The data show no evidence for a statistically significant association between fetal exposure and high rates of congenital malformations in fetuses exposed to tricyclic or other antidepressant drugs, although isolated cases of abnormalities have been reported. Paroxetine has been associated with ventricular septal defects for first-trimester exposure; venlafaxine has been associated with a poor neonatal adaptation syndrome, and mirtazapine with greater risk of preterm birth (Sadock et al.).

Although less information is known regarding the use of SSRIs during pregnancy compared with the use of TCAs, this class of drugs is emerging as first-line agents in treatment (Sadock et al., 2009). They are relatively safe and carry fewer side effects than the TCAs. However, if an SSRI is taken with dextromethorphan, an agent found in cough syrup, the combination could trigger the serotonin syndrome (e.g., mental status changes, agitation, hyperreflexia, shivering, and diarrhea). The most frequent side effects with the SSRIs are gastrointestinal (GI) disturbances (e.g., nausea and diarrhea), headache, and insomnia. In about one third of clients, the SSRIs reduce libido, arousal, or orgasmic function (Schatzberg et al., 2007). SSRIs also can inhibit specific P-450 isoenzymes, resulting in a marked elevation in drug concentration and a reduction in drug clearance. An epidemiologic study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the causes of birth defects found no association between SSRI use and birth defects. However, the study did find an association between SSRI use and a slightly increased risk for three specific birth defects: a defect of the brain, one type of abnormal skull development, and a GI abnormality. These increases in risk were minimal and have not been found before or since (Sadock et al.).

The TCAs cause many central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system side effects. Although some are simply annoying, others are significant or even dangerous (Schatzberg et al., 2007). In overdose, these medications can cause death. A common CNS effect is sedation. Other side effects include weight gain, tremors, grand mal seizures, nightmares, agitation or mania, and extrapyramidal side effects. Anticholinergic side effects include dry mouth, blurred vision (usually temporary), difficulty voiding, constipation, sweating, and difficulty with orgasm (Schatzberg et al.). The use of MAOIs during pregnancy is contraindicated because of risk for fetal growth restriction. In animals, hypertension with subsequent placental hypoperfusion and complications with anesthesia during labor have been reported (Sadock et al., 2009).

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders are the most common mental disorder. They include phobias (irrational fears that lead a person to avoid common objects, events, or situations), panic disorder (repeated, unprovoked episodes of intense fear that develop without warning and are not related to any specific event), generalized anxiety disorder (constant worry unrelated to any event), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (APA, 2000).

OCD symptoms include recurrent, persistent, and intrusive thoughts that cause anxiety, which a person tries to control by performing repetitive behaviors or “compulsions” (APA, 2000). The pregnant woman may have persistent thoughts that something is wrong with the fetus. Treatment usually includes antidepressant medication (SSRIs), cognitive-behavioral therapy, and education about how to manage the symptoms of the illness (Sadock et al., 2009).

PTSD can occur as a result of rape (see Chapter 5). Symptoms include reexperiencing the traumatic event, persistent avoidance of stimuli, and numbing, as well as difficulty sleeping, irritability or angry outbursts, difficulty concentrating, hypervigilance, and exaggerated startle response (APA, 2000). Nurses can support the healing process of individuals with PTSD by being alert to what the woman is experiencing during pregnancy and labor.

If the current pregnancy is a result of rape, the woman may be extremely ambivalent about the baby. If the rape occurred some time ago, the whole experience of pregnancy with prenatal examinations can trigger memories of the original trauma. She may avoid prenatal examinations because of the anxiety triggered by bodily touch and vaginal examinations. Some pregnant women with PTSD may feel more comfortable with a female nurse-midwife or a female physician. Giving birth can trigger memories of being out of control, and she may lose contact with reality. The nurse can verbalize understanding of the anxiety and orient to current reality by saying, “You’re having an examination to make sure the baby is okay,” or, “You’re in labor preparing to give birth to your baby. I am your nurse. You’re in the hospital. I will check on you frequently. You are safe here.” Treatment usually includes psychotherapy and referral to support groups.

Collaborative Care

Benzodiazepines and antidepressants are the most commonly used drugs for the treatment of anxiety disorders (see Table 32-1 and Table 32-2 for FDA categories for these medications). Although benzodiazepines are the most widely prescribed, antidepressant medications are the treatments of choice. Some pregnant women who have been using benzodiazepines for “anxiety,” “nervousness,” or insomnia may not realize that these medications may be teratogenic (with consequences including cleft lip and palate), and that their use during pregnancy is not advised, particularly during the first trimester (Schatzberg et al., 2007). Note that most of the antianxiety medications are FDA Category D (evidence of human fetal risk) or Category X (demonstrated fetal abnormalities and use is contraindicated). However, benzodiazepines should not be abruptly discontinued during pregnancy, and they should be tapered sufficiently before the birth to limit neonatal withdrawal syndrome. Nurses should educate women about the dangers of benzodiazepines during pregnancy, assess for use during pregnancy, and help pregnant women find other ways to handle their anxiety and insomnia, or refer them to a psychiatrist who specializes in psychiatric disorders in pregnancy. Nursing strategies to reduce anxiety include empowerment through education; sensory interventions such as music therapy and aromatherapy; behavioral interventions such as breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, and medication (see Table 32-2); and cognitive strategies such as encouraging positive self-talk and questioning negative thinking.

TABLE 32-2

| ANTIANXIETY MEDICATIONS | PREGNANCY RISK CATEGORY∗ | LACTATION RISK CATEGORY∗ |

| Alprazolam (Xanax) | D | L3 |

| Buspirone (BuSpar) | C | L3 |

| Chlordiazepoxide (Librium) | D | L3 |

| Clonazepam (Klonopin) | C | L3 |

| Clorazepate (Tranxene) | D | L3 |

| Diazepam (Valium) | D | L3; L4 if used chronically |

| Flurazepam (Dalmane) | X | L3 |

| Lorazepam (Ativan) | D | L3 |

| Midazolam (Versed) | D | L3 |

| Temazepam (Restoril) | X | L3 |

| Triazolam (Halcion) | X | L3 |

C = Animal studies show adverse effects on fetus but no controlled studies in pregnant women or no studies available.

D = Positive evidence of human fetal risk.

X = Contraindicated because studies have shown significant and documented risk to fetus.

L3 = No controlled studies or studies show minimal nonthreatening effects.

∗Sources: Hale, T. (2004). Medications and mother’s milk (11th ed.). Amarillo, TX: Pharmasoft; Schatzberg, A., Cole, J., & DeBattista, C. (2007). Manual of clinical psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Special Considerations for Medications During Pregnancy: Even though the basic rule is to avoid administering any medication to a woman who is pregnant, particularly during the first trimester, decisions about the use of medications during pregnancy should be made jointly by the woman, her partner, and her health care providers. If the woman is stable and appears likely to remain well while not taking medication, then discontinuation before pregnancy is a viable option. For those women with a history of relapse after medication discontinuation, remaining on the drug during pregnancy is advised. Although a pregnant woman should be receiving the lowest therapeutic dose, psychotropic medications may have to be increased over the course of pregnancy to maintain adequate therapeutic serum concentrations and response (Sadock et al., 2009). The administration of psychotherapeutic medications at or near birth may cause a baby to be overly sedated at birth and require ventilatory support, or to be physically dependent on the drug and to require detoxification and treatment of a withdrawal syndrome.

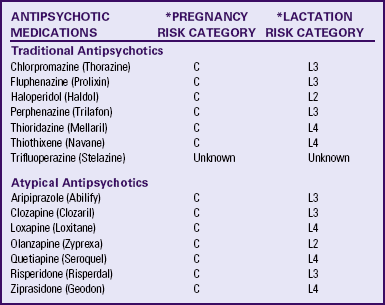

If a woman becomes psychotic during pregnancy, it is usually either because she has stopped taking mood stabilizers or antipsychotics, or because she has a history of schizophrenia. Psychosis is a medical emergency. To treat a psychotic state, antipsychotic medication or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) can be used (Bozkurt, Karlidere, Isintas, Ozmenier, Ozsahin, & Yanarates, 2007; Sadock et al., 2009). Lithium is currently considered the first-line medication for the treatment of psychosis during pregnancy (Roy & Payne, 2009).

Most of the mood-stabilizing medications such as lithium carbonate, carbamazepine (Tegretol), gabapentin (Neurontin), lamotrigine (Lamictal), and divalproex sodium (Depakote) are Category D (see Table 32-3 for FDA categories of mood stabilizers). In women with preexisting illness, there is a high recurrence of mania during pregnancy that may present as psychosis, thus maintenance on lithium is important to deter the development of adverse effects in the mother and infant. In reviews of epidemiologic data, the risk of Epstein’s anomaly (congenital cardiac defect involving the tricuspid valve) is lower than was previously thought (Sadock et al., 2009). Other side effects in the newborn include muscular hypotonia with impaired breathing and cyanosis (“floppy baby syndrome”), neonatal hypothyroidism, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, atrial flutter, tricuspid regurgitation, and congestive heart failure (Schatzberg et al., 2007). A 2008 study reported that discontinuing mood stabilizer treatment presents high risks of illness recurrence among pregnant women diagnosed with bipolar disorder. The researchers also reported that lamotrigine may afford protective effects with comparable fetal safety to other agents used to manage bipolar disorder (Newport, Stowe, Viguera, Calamaras, Juric, Knight, et al., 2008). Mood stabilizers are often taken over the life span by women with bipolar disorder. Women with this disorder should receive prepregnancy counseling. Those who have experienced a single manic episode may elect to have the medication tapered gradually and make an attempt to have a lithium-free pregnancy, or, if indicated, reinstitution of lithium after the first trimester.

TABLE 32-3

| MOOD STABILIZERS | PREGNANCY RISK CATEGORY∗ | LACTATION RISK CATEGORY∗ |

| Carbamazepine (Tegretol XR) | C | L2 |

| Clonazepam (Klonopin) | C | L3 |

| Gabapentin (Neurontin) | C | L3 |

| Lamotrigene (Lamictal) | C | L3 |

| Lithium carbonate (Eskalith) | C | L4 |

| Topiramate (Topamax) | C | L3 |

| Valproic acid (Depakene, Depakote, Depakote ER) | D | L2 |

C = Animal studies show adverse effects on fetus but no controlled studies in pregnant women or no studies available.

D = Positive evidence of human fetal risk.

L2 = Drug studied in limited number of breastfeeding women with no adverse effects in infant or evidence is remote.

L3 = No controlled studies or studies show minimal nonthreatening effects.

∗Sources: Hale, T. (2004). Medications and mother’s milk (11th ed.). Amarillo, TX: Pharmasoft; Schatzberg, A., Cole, J., & DeBattista, C. (2007). Manual of clinical psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

No conclusive evidence indicates that antipsychotic medications (either typical or atypical) are teratogenic (Sadock et al., 2009). Atypical antipsychotics (except clozapine) are currently classed as Category C agents simply because data do not exist to define a risk (Schatzberg et al., 2007). Some health care providers are more comfortable with the older typical antipsychotics because so many women have been treated with them with no clear evidence of a teratogenic effect. “At this time, it probably [is] preferable to employ high potency typical agents during pregnancy rather than either atypical agents, whose risks are unknown, or low-potency agents with significant anticholinergic properties” (Schatzberg et al., p. 555).

If the pregnant woman is receiving pharmacologic treatment, the nurse must make sure that she is being treated by a psychiatrist or an advanced practice psychiatric nurse. No woman should withdraw abruptly from any psychotropic medication because of the risk of withdrawal symptoms.

Substance Abuse During Pregnancy

Substance abuse refers to the continued use of substances despite related problems in physical, social, or interpersonal areas (APA, 2000). Recurrent abuse results in failure to fulfill major role obligations, and there may be substance-related legal problems. Any use of alcohol or illicit drugs during pregnancy is considered abuse (APA). Dual diagnosis is the coexistence of substance abuse and another disorder. Major depression and anxiety disorders are the psychiatric disorders that commonly occur with substance abuse.

The damaging effects of alcohol and illicit drugs on pregnant women and their fetuses are well documented (Gilbert, 2011; Wisner, Sit, Reynolds, Altemus, Bogen, Sunder, et al., 2007). Alcohol and other drugs easily pass from a mother to her fetus through the placenta. Smoking during pregnancy may have serious health risks, including bleeding complications, miscarriage, stillbirth, prematurity, low birth weight, and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Prenatal exposure to nicotine may lead to dysregulation in the neurodevelopment of the child and higher risk for behavioral problems (Gilbert; Wisner et al.). Congenital abnormalities have occurred in infants of mothers who have taken drugs. The safest pregnancy is one in which the mother is totally drug and alcohol-free, with one exception. For pregnant women addicted to opiates, methadone maintenance is safer for the fetus than acute opiate detoxification (Wisner et al.).

Prevalence

Because many pregnant women are reluctant to reveal their use of substances or the extent of their use, data on prevalence are highly variable. Approximately 15% of all mothers have a substance abuse problem (Gilbert, 2011). Among pregnant women responding to a national survey, 10% reported alcohol use, 4% reported binge alcohol use, and almost 1% reported heavy alcohol use in the month before the survey. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) estimated that the prevalence of alcohol use during pregnancy ranged from 3% to 10% (Brady & Ashley, 2005). Blinded urine drug screens conducted at hospitals across the United States revealed that similar rates of substance use during pregnancy occurred in women of different ages, races, and social classes, although the specific substances used differed by race and social class. African-American and poor women were more likely to use illicit substances, particularly cocaine, whereas Caucasian women were more likely to use alcohol (Wisner et al., 2007). The National Pregnancy and Health Survey found that 19% of females used alcohol during pregnancy, and 5% used an illicit drug at least once during pregnancy, including marijuana (3%), and cocaine (1%) (Brady & Ashley).

Risk Factors

Many factors contribute to substance abuse. Women have a clearer pattern of self-medication and are more likely than men to use a combination of alcohol and prescription drugs. Women begin to use drugs during periods of depression, to relax, to feel more adequate, to lose weight, to decrease stress, or to help them sleep at night. Many pregnant abusers encounter multiple socioenvironmental risk factors including unstable home environments (Miotto, Suti, Hernandez, & Pham, 2006). Major risk factors for substance abuse in women include a history of childhood sexual or physical abuse and a spouse or partner who abuses substances. In a national sample, substance use in pregnant women was significantly lower than in nonpregnant women. The pregnant women who were more vulnerable to substance use were unemployed, unmarried, and experiencing psychiatric disorders (Havens, Simmons, Shannon, & Hansen, 2009). Another important risk factor for substance abuse is intimate partner violence; victims are significantly more likely to abuse substances during pregnancy (Miotto et al.).

Barriers to Treatment

Less than 10% of pregnant women who are substance abusers receive treatment for their addictions. Social stigma, labeling, and guilt are significant barriers to treatment (Brady & Ashley, 2005). Women often do not seek help because they fear losing custody of their child or children or criminal prosecution. Pregnant women who abuse substances commonly have little understanding of the ways in which these substances affect them, their pregnancies, or their babies. Pregnant women who are substance abusers may not seek prenatal care until labor begins. Often pregnant women who use psychoactive substances receive negative feedback from society, as well as from health care providers, who not only may condemn them for endangering the life of their fetuses, but also may even withhold support as a result. Barriers within the drug treatment system can deter these women as well. Traditionally, substance-abuse treatment programs have not addressed issues that affect pregnant women, such as the concurrent need for obstetric care and child care for other children. Long waiting lists and lack of health insurance present further barriers to treatment. Pregnant women with coexisting substance abuse and psychiatric disorders face unique barriers because of the social stigma attached to both conditions along with providers’ insufficient knowledge and training to manage coexisting disorders (Brady & Ashley).

Legal Considerations

Because of the risks to the unborn children and financial concerns, pregnant women who abuse substances may face criminal charges in several states under expanded interpretations of child abuse and drug trafficking statutes. South Carolina is the only state that has passed specific legislation criminalizing pregnant women who abuse substances. However, many states have modified their civil child protection laws by mandating reports to child welfare authorities or defining child neglect to include cases in which a newborn is physically dependent, tests positive for, or has been harmed by substances of abuse. In 25 states, cases of maternal drug or alcohol use are referred to a hospital social worker, who evaluates and determines whether it is safe for the child to be taken home (Miotto et al., 2006). Nurses who screen for substance abuse in pregnancy and encourage prenatal care, counseling, and treatment will be of greater benefit to the mother and child than will prosecution.

Commonly Abused Drugs

Nicotine and caffeine are two examples of legal substances that can be addicting or harmful to the pregnant woman, fetus, and newborn. Effects of nicotine and caffeine on the fetus and newborn are discussed in Chapter 35. Tobacco contains nicotine, which is an addictive substance that creates both a physical and a psychologic dependence. Cigarette smoking is a major preventable cause of death and illness. Smoking is linked to cardiovascular disease, various types of cancers (especially lung and cervical), and chronic lung disease.

Smoking during pregnancy is known to cause a decrease in placental perfusion and is a cause of low birth weight (Bandestra & Accornero, 2006; Pichler, Heinzinger, Klaritsch, Zotter, Wilheim, & Uriesberger, 2008). The oxygen-carrying capacity of hemoglobin is decreased when carbon monoxide passes through the placenta. Furthermore, nicotine causes vasoconstriction, and smokers generally have a nutrient-poor diet. A 2009 study reported that the maternal use of tobacco while pregnant is associated with an increased risk for psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions in their children (Zammit, Thomas, Thompson, Horwood, Menezes, Gunnell, et al. 2009).

Caffeine is found in society’s most popular drinks: coffee, tea, chocolate, energy drinks, and soft drinks. It is a stimulant that can affect mood and interrupt bodily functions by producing anxiety and sleep disruptions. Although maternal caffeine consumption during pregnancy may have adverse effects on fetal, neonatal and maternal outcomes, a rigorous review of literature reported that there is insufficient evidence to confirm or refute the effectiveness of caffeine avoidance on birth weight or other pregnancy outcomes (Jahanfar & Sharifah, 2009). The March of Dimes, however, recommends a daily intake of no more than 200 mg (March of Dimes, 2008).

Alcohol

Despite warnings, prenatal exposure to alcohol far exceeds exposure to illicit drugs. Women give birth each year to more than 2.6 million infants who have been exposed to alcohol (Miotto et al., 2006). Disorders associated with prenatal alcohol exposure include fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), alcohol-related birth defects (ARBDs), and alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder. FAS is the most severe condition that affects the fetus. In fact FAS is the most common cause of preventable mental retardation and birth defects. It affects between 1.3 and 2.2 children per 1000 live births annually in North America (Miotto et al.). See Chapter 35 for information on newborn consequences of prenatal alcohol exposure.

Accurate data about alcohol abuse are difficult to obtain. Because alcohol is rapidly absorbed in the small intestine and metabolized in the liver, testing for its presence in blood is difficult. Underdiagnosing and underreporting alcohol use in pregnancy are major concerns of health care providers. Alcohol-dependent women who suddenly cease drinking may experience withdrawal symptoms that could be threatening to the mother and cause fetal distress (Miotto et al., 2006). Alcohol withdrawal in pregnant women is usually treated with benzodiazepines. Brief fetal exposure to benzodiazepines does not seem to increase the risk of major malformations or oral cleft. However, they can cause neonatal hypotonia, hypothermia, and mild neonatal respiratory distress when taken in late pregnancy (Miotto et al.).

Disulfiram (Antabuse), a medication that acts as a deterrent to alcohol ingestion because it produces a dramatic, unpleasant reaction when small amounts of alcohol are consumed, is contraindicated during pregnancy because it is teratogenic (Doering, 2005). Two other medications, naltrexone and acamprosate, have proven effective for decreasing alcohol intake. However, because they have not been tested in pregnant women, their use should be avoided (Doering).

Marijuana

Marijuana, a substance derived from the cannabis plant, is the most frequently used illicit drug in the United States (Miotto et al., 2006). It is usually rolled into a cigarette and smoked, but it also may be mixed into food and eaten. Marijuana produces a “high,” relaxation, increased appetite, and reduced inhibition. Prolonged use may lead to apathy, lack of energy, loss of desire to work or be productive, diminished concentration, poor personal hygiene, and preoccupation with marijuana—the amotivational syndrome (Gold, Roytberg, Frost-Pineda, Jacobs, & Teitelbaum, 2007). Marijuana causes increased carbon monoxide levels in the mother’s blood, which readily cross the placenta and reduce the oxygen supply to the fetus. Marijuana use during pregnancy can significantly affect the size of the neonate at birth, but research findings regarding the effects of maternal marijuana use on later child development are inconsistent (Miotto et al.).

Cocaine and Methamphetamine

Cocaine and methamphetamine are powerful CNS stimulants that block the reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamine at the nerve endings. Because more neurotransmitter is present at the synapse, the receptors are continuously activated. It is believed that this causes the euphoric effect for which both drugs are well known. At the same time, presynaptic supplies of dopamine and norepinephrine are depleted. This causes the “crash” that happens when the effect of the drug wears off (Andreasen & Black, 2007). The euphoria is short-lived, starting with a 10- to 20-second rush and followed by 15 to 20 minutes of less intense euphoria. A person who is high on cocaine feels euphoric, energetic, self-confident, and sociable. Stimulant intoxication can induce aggression, agitation, and impaired judgment. Unlike other stimulants, cocaine intoxication can cause tactile hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms including delusions, bizarre behavior, and paranoia (Andreasen & Black). The relapse rate for clients who try to discontinue cocaine use is very high.

Cocaine may be smoked, inhaled, or injected. The smokable form of cocaine is produced by a process called freebasing. Crack is cocaine mixed with baking soda and heated until it reaches its purest form. It is sold in the form of “rocks,” which are smoked in pipes (Miotto et al., 2006). Crack is used by people from all cultures. Its low cost and easy availability make it the drug of choice among the economically disadvantaged. In one study, cocaine was the primary substance of abuse for 17% of admissions to treatment among pregnant women (Miotto et al.). Because crack is highly psychologically addictive, it poses management problems for health care providers who care for pregnant addicts.

Medical complications of cocaine use in pregnancy range from mild to severe. Some of the less serious medical problems are lack of energy, insomnia, sinusitis, nosebleeds, sore throat, and decreased libido. More serious problems develop as the person’s general health deteriorates. These include perforation of the nasal septum, increased cardiovascular stress, tachycardia, systemic hypertension, ventricular arrhythmias, sudden coronary artery spasm, and myocardial infarction (Miotto et al., 2006). Needle-borne diseases such as hepatitis B and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are common among cocaine users. The tachycardia and subsequent increase in blood pressure are caused by the increasing levels of catecholamines produced by the cocaine (Sadock et al., 2009). During pregnancy uterine blood vessels are normally maximally dilated, but they vasoconstrict in the presence of catecholamines. The placental separation (abruption) or the acute onset of preterm labor with long, hard contractions and precipitate birth sometimes seen in pregnant women after they have used cocaine is probably secondary to acute spasm of uterine blood vessels.

At birth some infants show signs of cocaine exposure, including tremulousness, irritability, hyperactivity to environmental stimuli, and poor feeding (Sadock et al., 2009). Although infants with histories of prenatal cocaine exposure have higher rates of SIDS, it is unknown whether this is related to cocaine exposure itself or to co-occurring risk factors. Developmental problems in a range of physical and behavioral areas have been attributed to prenatal cocaine exposure, although the evidence for most remains inconclusive (Sadock et al.).

One of the promising treatments for cocaine abuse in pregnancy is acupuncture. A component of traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture is used to redirect energy flow (chi) within the body, reduce cravings, and enhance well-being. The pace and location of the flow of chi can be influenced by the insertion of needles at certain points along the meridians to facilitate harmony (Otto, 2003). Evidence from controlled studies of the effectiveness of acupuncture alone or in combination with other therapies, however, has been inconsistent. ![]()

Methamphetamine use is a major problem in the United States. Approximately 12 million Americans have tried “meth,” and 1.5 million are regular users (Schatzberg et al., 2007). Relatively cheap, the highly addictive stimulant is hooking more and more people across the socioeconomic spectrum. Meth makes many users feel hypersexual and uninhibited, thus leading to more sexual activity with less protection from pregnancy.

The active metabolite of methamphetamine is amphetamine. Agents used as appetite suppressants or diet pills are closely related substances. The crystalline form of methamphetamine is known as “ice.” When smoked it produces a potent, long-lasting high. Ice enables a person to go without rest or food for 24 hours, only to “crash” for the next 24 hours. Clinical manifestations of methamphetamine use are euphoria, abrupt awakening, increased energy, talkativeness, elation, agitation, hyperactivity, irritability, grandiosity, diaphoresis, weight loss, insomnia, hypertension, increased temperature, ectopic heartbeat, urinary retention, constipation, dry mouth, paranoid delusions, and violent behavior. Seizures, heart attacks, strokes, and death may occur as a result of overdose (Miotto et al., 2006).

Although fewer maternal and neonatal complications have been attributed to this class of substances than to cocaine (APA, 2000), the rates of preterm birth and of intrauterine growth restriction with smaller head circumference are higher in methamphetamine-exposed pregnant women than in pregnant women who abuse other substances (see Chapter 35). Another complication of methamphetamine use is an increased incidence of placental abruption. As with cocaine, methamphetamine dependence is best managed in an inpatient treatment setting, with follow-up substance abuse treatment (Miotto et al., 2006).

Opiates

Opiates include opium, heroin, morphine, codeine, and methadone. Methadone is used to treat addiction to other opiates. It can be used either to aid withdrawal or to provide maintenance at a stable dose. Women taking methadone may work and live normally, although they are still addicted to narcotics. Heroin is one of the most commonly abused drugs of this class. It is usually taken by intravenous injection but can be smoked or “snorted” (Miotto et al., 2006). The signs and symptoms of heroin use are euphoria, relaxation, relief from pain, “nodding out” (apathy, detachment from reality, impaired judgment, and drowsiness), constricted pupils, nausea, constipation, slurred speech, and respiratory depression (APA, 2000).

The incidence of heroin use among pregnant women is unknown; however, those women with a dependency on heroin may use multiple drugs. Possible effects on pregnancy include preeclampsia, IUGR, miscarriage, premature rupture of membranes, infections, breech presentation, and preterm labor. Adverse outcomes for the neonate include low birth weight, prematurity, neonatal abstinence syndrome, stillbirth, and SIDS (Miotto et al., 2006).

The recommended treatment for opiate dependence during pregnancy is methadone maintenance combined with psychotherapy. This well-documented approach improves outcomes for both woman and fetus (Miotto et al., 2006). Another treatment method is slow medical withdrawal with methadone, but the safety of this second approach is questionable. During pregnancy methadone is metabolized more rapidly, leading to withdrawal symptoms in less than 24 hours in many women. These symptoms can include fetal hyperactivity and, if severe, preterm labor or fetal death. Women may resort to heroin use to alleviate the uncomfortable symptoms. If higher doses of methadone are required during the course of pregnancy, twice-daily medication administration (morning and evening) is the most effective way to prevent withdrawal and subsequent heroin use (Miotto et al.).

Care Management

The care of the substance-dependent pregnant woman is based on historical data, symptoms, physical findings, and laboratory results. All pregnant women should be asked screening questions for alcohol and drug abuse in the overall assessment at the first prenatal visit. Any judgmental attitude on the part of the health care provider will be evident to the woman and will interfere with the development of trust and with an accurate report of consumption. Information about drug use should be obtained by first asking about the woman’s intake of over-the-counter and prescribed medications. Next, her use of legal drugs such as caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol should be determined. Finally, she should be questioned about her use of illicit drugs, such as cocaine, heroin, and marijuana. The approximate frequency and amount should be documented for each drug used (Seidel, Ball, Dains, Flynn, Solomon, & Stewart, 2011).

A variety of screening tests are available to screen for alcohol abuse. The CAGE questionnaire (Ewing, 1984) (Box 32-1) and the Brief Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) (Pokorny, Miller, & Kaplan, 1972) are two well-known screens for alcohol use that are often administered by the nurse or included in the written previsit questionnaire. The CAGE is the most popular test used in primary care. Both the CAGE and MAST questionnaires, however, focus on alcohol dependency and may not be sensitive enough to detect the levels of drinking that are considered harmful in pregnancy. The 4P’s Plus (Box 32-2) is a screening tool designed specifically to identify pregnant women who need in-depth assessment. It consists of five questions and takes less than a minute to complete (Chasnoff, McGourty, Bailey, Hutchins, Lightfoot, Pawson, et al., 2005). Because pregnant women frequently deny or greatly underreport usage, asking about substance use prior to pregnancy is often a more effective screening method (Wisner et al., 2007).

Urine toxicology testing is often performed to screen for illicit drug use. Drugs may be found in urine days to weeks after ingestion, depending on how quickly they are metabolized and excreted from the body. Meconium (from the neonate) and hair can also be analyzed to determine past drug use over a longer period (Gilbert, 2011).

In addition to screening for alcohol and drug abuse, the nurse should also screen for physical and sexual abuse and history of psychiatric illness because these are risk factors in women who abuse substances. Substance-abusing women feel much stigma, shame, and guilt, which leads to denial of the abuse. If the nurse can help reduce those feelings, the woman will be more apt to confide in the nurse—the first step in receiving help. Asking about how a spouse or partner feels about using substances can reveal whether there are family supports or barriers (see Box 32-2).

Assessment

After screening results indicate that substance abuse is a problem for an individual woman, the nursing process is used to deal with that problem (see the Nursing Process box). Because of the lifestyle often associated with drug use, substance-abusing women are at risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV. Laboratory assessments will likely include screening for syphilis, hepatitis B and C, and HIV. A skin test to screen for tuberculosis may also be ordered. Initial and serial ultrasound studies are usually performed to determine gestational age because the woman may have had amenorrhea as a result of her drug use or may have no idea when her last menstrual period occurred.

Collaborative Care

Intervention with women who have substance abuse problems begins with education about specific effects on pregnancy, the fetus, and the newborn for each drug used. Consequences of

perinatal drug use should be clearly communicated and abstinence recommended as the safest course of action, unless the woman is abusing opioids. Women are frequently more receptive to making lifestyle changes during pregnancy than at any other time in their lives. The casual, experimental or recreational drug user is frequently able to achieve and maintain abstirence when she receives education, support, and continued monitoring throughout the remainder of the pregnancy.

Treatment for substance abuse will be individualized for each woman, depending on the type of drug used and the frequency and amount of use. Women are more likely to attempt to stop smoking during pregnancy than at any other time in their lives. Quitting before conception is ideal but even quitting before 16 weeks of gestation significantly decreases the risks. Smoking cessation programs during pregnancy are effective and should be offered to all pregnant smokers (see Box 4-11). These programs should continue throughout the postpartum period as well, because many women resume smoking after the birth. Many smoking cessation resources are available, both in print and online (Gilbert, 2011; Wisner et al., 2007). For more information on smoking cessation, visit the American Lung Association’s website at www.lungusa.org.

National concern regarding the problem of alcohol and drug use during pregnancy has brought attention to not only the lack of treatment programs specifically targeted to pregnant women, but also the need for high quality randomized controlled trials to determine the effectiveness of interventions (Lui, Terplan, & Smith, 2008). Any discussion of treatment programs must start with the understanding that substance abuse in women is a complex problem surrounded by multiple individual, familial, and social issues that require many levels of intervention and treatment (Worley, Conners, Crone, Williams, & Bokony, 2005). The powerlessness of the alcoholic condition and the powerlessness of the female condition act on each other, reinforcing the impotence and hopelessness of both and leaving the woman with few resources to regain control of her life. In comparing women-only with mixed-gender substance abuse treatment programs, pregnant women treated in a women-only program demonstrated greater severity in drug use, legal problems, and psychiatric problems than those treated in the mixed-gender group (Hser & Niv, 2006). The women in the women-only group were less likely to be employed and more likely to be homeless, more likely to need child care, children’s psychologic services, and HIV testing. The greater problem severity of pregnant women treated in women-only programs suggests that these specialized services are filling an important gap in addiction services, although further expansion is warranted (Hser & Niv).

Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) is currently considered the standard of care for pregnant women dependent on heroin or other narcotics. Birth weight and head circumference are increased in infants born to women receiving MMT. However, 30% to 80% of infants exposed to opioids, including methadone, in utero require treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome (see Chapter 35) (Wisner et al., 2007). Higher doses of maternal methadone are associated with an increase in diagnosis and longer duration of neonatal abstinence syndrome (Lim, Prasad, Samuels, Gardner, & Cordero, 2009). Pregnant women who use stimulants should be advised to stop using immediately, but they will need a great deal of assistance to do so and the rate of relapse is very high (Miotto et al., 2006).

There is little empirical evidence as to what treatment program is best for substance-using mothers; however, two studies are notable. Greenfield and associates (2004) found a strong association between length of stay in residential treatment and posttreatment abstinence. Terplan and Lui (2007) reported that “contingency management” was effective in improving the retention of pregnant women in illicit drug treatment programs, but it had only a minimal effect on abstinence and did not affect birth or neonatal outcomes. There is general agreement that programs should include a cognitive-behavioral approach and mostly female staff. Programs also need to address issues of stigmatization, the high probability of sexual and physical abuse, lack of social support, need for social services and child care, need for transportation, family support services, medical (particularly women’s health) and mental health services, child development services, family planning, respite care, life skills management, pharmacologic services, self-help groups and stress management, and need for support and education in the mothering role. Drug-free public housing or residential communities may offer an ideal route to stabilization in a safe environment. Treatment must demonstrate cultural sensitivity and responsiveness to recognize ethnicity and culture as an important part of a woman’s identity. Many women also need relationship counseling and vocational and legal assistance.

Women for Sobriety may be a more helpful organization for women than Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or Narcotics Anonymous (NA), which are based on the 12-step program. The emphasis on powerlessness over addiction and avoidance of codependency found in 12-step programs may further disempower and isolate women, particularly women of color (Saulnier, 1996). The confrontational techniques of the 12-step program, developed to break down denial in men, may be especially threatening to women, who often feel unworthy and full of shame and guilt. In addition, women may be vulnerable to “thirteenth-stepping”—a euphemistic term referring to men who target new, more vulnerable women for dates or sex. In one study, 50% of the women experienced thirteenth-stepping behaviors, and two had been raped by men in AA (Bogart & Pearce, 2003). Especially vulnerable women, such as those with histories of sexual abuse, should be referred to female-only groups.

Whereas the treatment approach of male substance abusers tends to be oriented toward the individual, substance-abusing women should be viewed within the context of their relationships to others. Women tend to find satisfaction, pleasure, and a sense of worth if they experience their life activities as arising from and leading back to a sense of connection with others. Women who use illicit drugs are likely to be introduced to and supplied with these drugs by men as part of an intimate or sexual relationship.

An interdisciplinary, comprehensive model is essential when planning the care for women who abuse substances. Pregnancy presents a window of opportunity for motivating women to stop their abuse of substances, but what specifically can a nurse do?

First, nurses must be knowledgeable about how to screen and identify women who abuse substances while pregnant. They also must maintain a nonjudgmental, nonpunitive attitude. Nurses can advocate for access to woman-centered drug treatment and harm reduction measures to minimize the damage caused by alcohol and drugs (Lester & Twomey, 2008). Collaboration with advanced practice psychiatric nurses will enable nurses to deal with their feelings and provide better care for this challenging group of women. Until the nurse can approach the woman with caring and concern, the therapeutic alliance, which is so important for any change to take place, will not occur. The nurse’s role is aimed not only at promoting abstinence but also providing a caring, nurturing, and empowering environment in which women can rediscover their values and become authentic, independent decision makers. Use of the contingency management model, which includes an abstinence-based incentive program and substance monitoring contract, may be useful with adolescent abusers (Stanger, Budney, Kamon, & Thostensen, 2009).

Second, the nurse should determine the individual’s readiness for change. One model for doing this was developed by Prochaska and DiClemente (1992). The five stages of the model illustrate the readiness of women to change. Precontemplation is the earliest stage, in which individuals are unaware, unwilling, or discouraged about changing substance use behavior. They will be least responsive to interventions focused on change activities. First they need to take ownership of the problem. Contemplation involves an active consideration of the prospects of change. Women engage in information seeking and begin to reevaluate themselves in light of their substance abuse behavior. Preparation indicates a readiness to change. They intend to change in the near future and have learned valuable lessons from past change attempts and failures. Action involves the overt modification of the problem behavior, and individuals must have the skills to carry out the changes. Maintenance is the final stage. Environmental supports are particularly important in this stage, as well as supportive relationships with health care providers.

When working with pregnant adolescents with addictions, the nurse also must consider their developmental stage. A part of normal adolescence often includes experimenting with drugs or alcohol, so how does the nurse know when alcohol or drug use is a problem? Certain patterns, such as drinking to escape reality or drinking to “get wasted,” are more dangerous than others. Drinking alone and being secretive about drugs and alcohol also are unhealthy patterns.

Third, the nurse uses supportive nursing interventions such as mutuality and avoidance of confrontation. In mutuality, the nurse conveys to women drug users that their perspective on their life situation is as valid as that of the nurse. Women should be encouraged to describe their views on the role of drug use in their lives, the degree of impairment they are experiencing, and the feasibility of change at this time. Avoiding confrontation is important because it can be damaging to the nurse-client relationship. The likely consequences of continued drug use can be presented in a warmly concerned, factual manner rather than as threats.

Fourth, the nurse uses principles of motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 1991) to effect change. These principles include the following:

• Developing the discrepancy between individuals’ perceptions of where they are and where they want to be

When problematic drug use is suspected, the nurse might ask in a noncritical way, “Are drugs or alcohol any part of this situation you have been describing?” By asking about the role of drugs in self-medication for stressors, the nurse can help the woman reflect on the degree of the problem and avenues for change. The woman can be helped to express the positive aspects of drug use that lead her to continue using and the harmful consequences that she has observed. She can be asked about times she tried to reduce or quit using her drug of choice. What interfered with her success? What times was she successful? What enabled her to succeed at those times? Praise can be given for being able to be successful at some time and optimism expressed that she can be successful again.

Doggett and colleagues (2005) reviewed six studies that provided home visit services to postpartum women who had drug or alcohol problems. Home visitors in these studies included community health nurses, pediatric nurses, trained counselors, paraprofessional advocates, midwives, and lay African-American women. Although the home visits did increase the women’s involvement in drug treatment services, there was insufficient evidence to show that they improved the health of mothers or babies. Additional research is recommended, particularly with the home visits beginning during pregnancy.

Intrapartum and Postpartum Care Considerations: Although women who abuse substances may be difficult to care for at any time, they are often particularly challenging during the intrapartum and postpartum periods because of manipulative and demanding behavior. Typically, these women display poor control over their behavior and a low threshold for pain. Increased dependency needs and poor parenting skills may also be apparent.

Nurses must understand that substance abuse is an illness and that these women deserve to be treated with patience, kindness, consistency, and firmness when necessary. Even women who are actively abusing drugs will experience pain during labor and after giving birth and may need pain medication, as well as nonpharmacologic interventions. Developing a standardized plan of care so that clients have limited opportunities to play staff members against one another is helpful. Mother-infant attachment should be promoted by identifying the woman’s strengths and reinforcing positive maternal feelings and behaviors. Staffing should be sufficient to ensure strict surveillance of visitors and prevent unsupervised drug use.

Advice regarding breastfeeding must be individualized. Although all abused substances appear in breast milk, some in greater amounts than others (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2005), breastfeeding is definitely contraindicated in women who use amphetamines, alcohol, cocaine, heroin, or marijuana. Methadone use, however, is not a contraindication to breastfeeding. The baby’s nutrition and safety needs are of primary importance in this consideration. For some women a desire to breastfeed may provide strong motivation to achieve and maintain abstinence.

Smoking can interfere with the let-down reflex. Women who smoke in the postpartum period and breastfeed should avoid smoking for 2 hours before a feeding to minimize the nicotine content in the milk and improve the let-down reflex. All smokers should be discouraged from smoking in the same room with the infant because exposure to secondhand smoke can increase the likelihood that the infant will experience behavioral and respiratory health problems (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2005).

Before a woman who is a known substance abuser is discharged with her baby, the home situation must be assessed to determine that the environment is safe and that someone will be available to meet the infant’s needs if the mother proves unable to do so. The hospital’s social services department will usually be involved in interviewing the mother before discharge to ensure that the infant’s needs will be met. Family members or friends will sometimes be asked to become actively involved with the mother and infant after discharge. A home care or public health nurse may be asked to make home visits to assess the mother’s ability to care for the baby and provide guidance and support. If serious questions about the infant’s well-being exist, the case will probably be referred to the state’s child protective services agency for further action.

Postpartum Psychologic Complications

The weeks following the birth are a time of vulnerability to psychiatric disorders for many women, causing significant distress for the mother, disrupting family life, and, if prolonged, negatively affecting the child’s emotional and social development (Hendrick, 2006). Mood and anxiety disorders are particularly likely to recur or worsen during these weeks. Such conditions can interfere with attachment to the newborn and family integration, and some may threaten the safety and well-being of the mother, the newborn, and other children. Because birth is usually thought to be a happy event, a new mother’s emotional distress may puzzle and immobilize family and friends. When she most needs the caring attention of loved ones, they may either criticize or withdraw because of their anxiety. Nurses can offer anticipatory guidance, assess the mental health of new mothers, offer therapeutic interventions, and make referrals when necessary. Failure to do so may result in tragic consequences. In the rarest of cases, a disturbed mother may kill her infant, other family members, or herself.

Mood Disorders

Mood disorders are the predominant mental health disorder in the postpartum period (APA, 2000). Up to 60% of women experience a mild depression or “baby blues” after the birth of a child; however, functioning of the woman is usually not impaired. Serious depression, experienced by 10% to 15% of postpartum women, can eventually incapacitate them to the point of being unable to care for themselves or their babies (Sadock et al., 2009). Postpartum depression occurs in a variety of countries, though the manifestations may vary by culture (Goldbort, 2006). In a community sample of postpartum Spanish mothers, 18% were found to have postpartum psychiatric disorders (Navarro, Garcia-Esteve, Ascasco, Aguardo, Gelabert, & Martin-Santos, 2008).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) contains the official guidelines for the assessment and diagnosis of psychiatric illness (APA, 2000). However, specific criteria for postpartum depression (PPD) Bold for key term.are not listed. Instead, postpartum onset can be specified for any mood disorder either without psychotic features (i.e., PPD) or with psychotic features (i.e., postpartum psychosis) if the onset occurs within 4 weeks of childbirth (APA).

Etiology and Risk Factors

The cause of PPD may be biologic, psychologic, situational, or multifactorial. Several studies suggest that estrogen fluctuations and postpartum hypogonadism (the change from the high levels of estrogen and progesterone at the end of pregnancy to the much lower levels of both hormones that are present after birth) are important etiologic factors. Of women who present with PPD, 20% to 30% have a previous episode of major depressive disorder (MDD) (Epperson & Ballew, 2006). Other risk factors include a personal history of severe premenstrual dysphoria, family history of mood disorder, marital discord, lack of a confiding relationship, and stressful life events in the previous year (Epperson & Ballew; Milgrom, Gemmill, Bilszta, Hayes, Barnett, Brooks, et al., 2008). Mood and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy and postpartum blues increase the risk for PPD (APA, 2000). Neurotransmitter deficiencies and psychosocial and marital adjustments in the postpartum period have been related to PPD (APA). Although personal and family history of psychiatric disorders are the major risk factors for PPD, the potential role of psychosocial variables as risk factors for depression onset during the postpartum period should not be underestimated (Sadock et al., 2009). In a comprehensive review of the literature, Bina (2008) found that cultural practices could positively or negatively affect the development of PPD. Women facing multiple or severe psychosocial problems or chronic interpersonal difficulties are at increased risk of experiencing a major depressive episode.

The occurrence of PPD is higher among younger women, those with lower educational attainment, and those receiving Medicaid (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2008). African-American mothers were twice as likely as Caucasian mothers to experience PPD. Mothers who had no one to talk to about their problems after giving birth had a high rate of PPD and a low rate of seeking help (Sword, Busser, Ganann, McMillan, & Swinton, 2008).

Beck (2008a, 2008b) published an integrative review of 141 studies of what nurse researchers internationally have contributed to the state of the science on postpartum depression. One aspect was in identifying risk factors. Beck described at least five instruments that have been developed since 1990 to assess risk factors or symptoms of PPD. The most common risk factors are listed in Box 32-3.

Postpartum Depression Without Psychotic Features

PPD is an intense and pervasive sadness with severe and labile mood swings and is more serious and persistent than postpartum blues. Intense fears, anger, anxiety, and despondency that persist past the baby’s first few weeks of life are not a normal part of postpartum blues. Occurring in approximately 10% to 15% of new mothers, these symptoms rarely disappear without outside help (CDC, 2008; Sadock et al., 2009). Approximately 50% of these mothers, however, do not seek help from any source (Dennis & Chung-Lee, 2006). The occurrence of PPD among teenage mothers is approximately 50% more than that for older mothers (Driscoll, 2006). Young mothers (younger than 20 years) and those with a high school education or less are less likely to seek help and have higher rates of PPD than other women (Mayberry, Horowitz, & Declercq, 2007).

The symptoms of postpartum major depression do not differ from the symptoms of nonpostpartum mood disorders, except that the mother’s feelings of guilt and inadequacy feed her worries about being an incompetent and inadequate parent. In PPD, the woman may have odd food cravings (often, sweet desserts) and binges with abnormal appetite and weight gain. New mothers report an increased yearning for sleep, sleeping heavily but awakening instantly with any infant noise, and an inability to go back to sleep after infant feedings. Determining difficulty falling asleep is a relevant screening question to ascertain risk for PPD (Goyal, Gay, & Lee, 2007).

A distinguishing feature of PPD is irritability. These episodes of irritability may flare up with little provocation, and they may sometimes escalate to violent outbursts or dissolve into uncontrollable sobbing. Many of these outbursts are directed against significant others (“He never helps me”) or the baby (“She cries all the time, and I feel like hitting her”). Women with postpartum major depressive episodes often have severe anxiety, panic attacks, and spontaneous crying long after the usual duration of baby blues.

Many women feel especially guilty about having depressive feelings at a time when they believe they should be happy. They may be reluctant to discuss their symptoms or their negative feelings toward the infant. A prominent feature of PPD is rejection of the infant, often caused by abnormal jealousy (APA, 2000). The mother may be obsessed by the notion that the offspring may take her place in her partner’s affections. Attitudes toward the infant may include disinterest, annoyance with care demands, and blaming because of her lack of maternal feeling. When observed, she may appear awkward in her responses to the baby. Obsessive thoughts about harming the child are very frightening to her. Often she does not share these thoughts because of embarrassment, but when she does, other family members may be frightened.

Medical Management: The natural course of PPD is one of gradual improvement over the 6 months after birth. However, supportive treatment alone is not efficacious for major PPD. Pharmacologic intervention is needed in most instances. Treatment options include antidepressants, antianxiety agents (shorter acting), mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, and ECT (Epperson & Ballew, 2006). A number of nonpharmacologic options have shown some success in investigations. Alternative therapies such as herbs, dietary supplements, massage, aromatherapy, bright light therapy, and acupuncture may be helpful.![]() Women should be encouraged to take time for themselves, to rest and relax, and to ask friends and family for help as needed. Exercise, proper nutrition, and adequate sleep also contribute to symptom alleviation. Psychotherapy focuses on the woman’s fears and concerns regarding her new responsibilities and roles, as well as monitoring for suicidal or homicidal thoughts. Support groups and marital counseling may be helpful (Epperson & Ballew). For some women, hospitalization is necessary.

Women should be encouraged to take time for themselves, to rest and relax, and to ask friends and family for help as needed. Exercise, proper nutrition, and adequate sleep also contribute to symptom alleviation. Psychotherapy focuses on the woman’s fears and concerns regarding her new responsibilities and roles, as well as monitoring for suicidal or homicidal thoughts. Support groups and marital counseling may be helpful (Epperson & Ballew). For some women, hospitalization is necessary.

Postpartum Depression with Psychotic Features

The most severe of the perinatal mood disorders, postpartum psychosis is rare, affecting approximately 0.1% to 0.2% of postpartum women (Sadock et al., 2009). Once a woman has had one episode of postpartum psychosis, she has a 30% to 50% likelihood of recurrence with each subsequent birth (APA, 2000). This disorder tends to show onset within 2 weeks postpartum; however, it may present later in the course of the illness as a depression (Sadock et al.).

Episodes of postpartum psychosis are typified by auditory or visual hallucinations, paranoid or grandiose delusions, elements of delirium or disorientation, and extreme deficits in judgment accompanied by high levels of impulsivity that may contribute to increased risks of suicide or infanticide (in 5% of psychotic women) (Sadock et al., 2009). Characteristically the woman begins to complain of fatigue, insomnia, and restlessness and may have episodes of tearfulness and emotional lability. Complaints regarding the inability to move, stand, or work also are common. Later, suspiciousness, confusion, incoherence, irrational statements, and obsessive concerns about the baby’s health and welfare may be present. Delusions may be present in 50% of women with postpartum psychosis, and hallucinations in approximately 25% of women with this disorder. Auditory hallucinations that command the mother to kill the infant can occur in severe cases. When delusions are present, they are often related to the infant. The mother may think the infant is possessed by the devil, has special powers, or is destined for a terrible fate (APA, 2000). Grossly disorganized behavior may be manifested as a disinterest in the infant or an inability to provide care. Some women will insist that something is wrong with the baby or accuse nurses or family members of hurting or poisoning their child.

Postpartum psychosis is most commonly associated with the diagnosis of bipolar (or manic-depressive) disorder (Sadock et al.; Sharma, Burt, & Ritchie, 2009). This mood disorder is defined by the presence of one or more episodes of abnormally elevated energy levels, cognition, and mood and one or more depressive episodes. The elevated moods are clinically referred to as mania. Clinical manifestations of a manic episode include at least three of the following: grandiosity, decreased need for sleep, pressured speech, flight of ideas, distractibility, psychomotor agitation, and excessive involvement in pleasurable activities without regard for negative consequences (APA, 2000). While in a manic state, mothers need constant supervision when caring for their infant. Usually, however, they are too preoccupied to provide child care. Individuals who experience manic episodes also commonly experience depressive episodes or symptoms, or mixed episodes, in which features of both mania and depression are present at the same time. These episodes are usually separated by periods of “normal” mood, but in some individuals, depression and mania may rapidly alternate. These rapid changes in mood are known as rapid cycling.

Medical Management: Postpartum psychosis carries a relatively good prognosis with early detection and aggressive treatment, but if left untreated it may progress to the second postpartum year and become more refractory to treatment (Sadock et al., 2009). Postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency, and the mother will probably need psychiatric hospitalization. Antipsychotics and mood stabilizers such as lithium are the treatments of choice (see Table 32-3 and Table 32-4 for FDA categories of risk). Antidepressants should be used very cautiously in treating postpartum psychosis, even when depressive symptoms are present, because of the risk of precipitating rapid cycling. Given that 43.4% of women breastfeed for at least the first 6 weeks after birth, informed consent regarding the risks and benefits of exposing the newborn to a psychotropic agent and maternal mental illness must be discussed and documented (see additional discussion of lactation and psychotropic medications later in this chapter). ECT, especially when bilaterally administered, has also been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of postpartum psychosis (Epperson & Ballew, 2006). It is usually advantageous for the mother to have contact with her baby if she so desires, but visits must be closely supervised. Psychotherapy is indicated after the period of acute psychosis has passed.

TABLE 32-4

C = Animal studies show adverse effects on fetus but no controlled studies in pregnant women or no studies available.

L2 = Drug studied in limited number of breastfeeding women with no adverse effects in infant or evidence is remote.

L3 = No controlled studies or studies show minimal nonthreatening effects.

∗Source: Hale, T. (2004). Medications and mother’s milk (11th ed.). Amarillo, TX: Pharmasoft.

Care Management

Even though the prevalence of PPD is fairly well established, it often remains undetected because women are hesitant to report symptoms of depression to their own health care providers or to seek help from a mental health provider (McQueen, Montgomery, Lappan-Gracon, Evans, & Hunter, 2008). Primary health care providers can usually recognize severe PPD or postpartum psychosis but may miss milder forms; even if it is recognized, the woman may be treated inappropriately or subtherapeutically. Identification and treatment of maternal depression must be continued beyond the immediate post-birth period to prevent negative effects of maternal depression on the children of these mothers (McCue Horwitz, Briggs-Gowan, Storfer-Isser, & Carter, 2007). The following discussion identifies ways to assess for symptoms of PPD and describes the treatment options (see the Nursing Care Plan: Postpartum Depression and the Process box: Postpartum Depression).

To recognize symptoms of PPD as early as possible, the nurse should be an active listener and demonstrate a caring attitude. Nurses cannot depend on women volunteering unsolicited information about their depression or asking for help. The nurse should observe for signs of depression and ask appropriate questions to determine moods, appetite, sleep, energy, and fatigue levels, and ability to concentrate. Examples of ways to initiate conversation include the following: “Now that you have had your baby, how are things going for you?” “Have you had to change many things in your life since having the baby?” and “How much time do you spend crying?” If the nurse assesses that the new mother is depressed, she or he must ask if the mother has thought about hurting herself or the baby. The woman may be more willing to answer honestly if the nurse says, “Lots of women feel depressed after having a baby, and some feel so bad that they think about hurting themselves or the baby. Have you had these thoughts?”

Postpartum Depression Screening Tools

Nurses can use screening tools in assessing whether the depressive symptoms have progressed from postpartum blues to PPD. Examples of screening tools are the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory (PDPI), and the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (PDSS). The EPDS is a self-report assessment designed specifically to identify women experiencing PPD. It has been used and validated in studies in numerous cultures and is viewed as a valid screening tool for PPD (Lintner & Gray, 2006). ![]() The assessment tool asks the woman to respond to 10 statements about the common symptoms of depression. The woman is asked to choose the response that is closest to describing how she has felt for the past week (Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987) .

The assessment tool asks the woman to respond to 10 statements about the common symptoms of depression. The woman is asked to choose the response that is closest to describing how she has felt for the past week (Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987) .

Through focused research over at least a decade, Beck has developed and continues to refine the PDPI (PDPI-R [Revised]) (Beck, 2001, 2002) and the PDSS (Beck & Gable, 2002). The PDPI-R consists of 13 risk factors related to PPD. The PDSS is a 35-item Likert response scale that assesses for seven dimensions of depression: sleeping or eating disturbances, anxiety or insecurity, emotional lability, mental confusion, loss of self, guilt or shame, and suicidal thoughts (Beck, 2008a). Both published tools are designed to be used by nurses and other health care providers to elicit information from the woman during an interview to assess risk. Areas assessed include the predictors of depression as listed in Box 32-3.

In addition, a simple two-item tool has been shown to be effective in identifying women at risk for PPD. Ask, “Are you sad and depressed?” and “Have you had a loss of pleasurable activities?” An affirmative answer to both questions suggests that depression is likely (Jesse & Graham, 2005).

If the initial interaction with the woman or analysis of her self-report reveals some question that she might be depressed,

a formal screening is helpful in determining the urgency of the referral and the type of provider. Also important is the need to assess the woman’s family because they may be able to offer valuable information, as well as need to express how they have been affected by the woman’s emotional disorder.

Nursing Care on the Postpartum Unit

The postpartum nurse must observe the new mother carefully for any signs of tearfulness and conduct further assessments as necessary. Nurses must discuss PPD to prepare new parents for potential problems in the postpartum period (see the Teaching for Self-Management box and Chapter 21). The family must be able to recognize the symptoms and know where to go for help. Written materials that explain what the woman can do to prevent depression could be used as part of discharge planning.

Mothers are often discharged from the hospital before the blues or depression occurs. If the postpartum nurse is concerned about the mother, a mental health consult should be requested before the mother leaves the hospital. Routine

instructions regarding PPD should be given to the person who comes to take the woman home; for example, “If you notice that your wife [or daughter] is upset or crying a lot, please call the postpartum care provider immediately—don’t wait for the routine postpartum appointment.”

Nursing Care in the Home and Community