Nursing Care of the Newborn and Family

• Explain the purpose and components of the Apgar score.

• Describe how to perform a physical assessment of a newborn.

• Describe how to perform a gestational age assessment of a newborn.

• Compare the characteristics of the preterm, late preterm, term, and postterm neonate.

• Explain the elements of a safe environment.

• Discuss phototherapy and the guidelines for teaching parents about this treatment.

• Explain the purposes and methods for circumcision, the postoperative care of the circumcised infant, and parent teaching regarding circumcision.

• Review the procedures for performing a heelstick, collecting urine specimens, and assisting with venipuncture.

• Evaluate pain in the newborn based on physiologic changes and behavioral observations.

• Review anticipatory guidance nurses provide to parents before discharge.

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/MWHC/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/MWHC/

Audio Glossary

Case Study

Critical Thinking Exercises

Nursing Care Plans

Spanish Guidelines

Video—Assessment

Although most infants make the necessary biopsychosocial adjustments to extrauterine existence without undue difficulty, their well-being depends on the care they receive from others. This chapter describes the assessment and care of the infant immediately after birth until discharge, as well as important anticipatory guidance related to ongoing infant care. A discussion of pain in the neonate and its management is included.

Care Management: Birth Through the First 2 Hours

Care begins immediately after birth and focuses on assessing and stabilizing the newborn’s condition. The nurse has the primary responsibility for the infant during this period because the physician or midwife is involved with care of the mother. The nurse must be alert for any signs of distress and initiate appropriate interventions.

With the possibility of transmission of viruses such as hepatitis B virus (HBV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) through maternal blood and blood-stained amniotic fluid, the newborn must be considered a potential contamination source until proved otherwise. As part of Standard Precautions, nurses wear gloves when handling the newborn until blood and amniotic fluid are removed by bathing.

The foundation for providing comprehensive, family-centered newborn care is awareness of the mother’s preconception and prenatal history as well as intrapartal events. Recognition of risk factors (Box 24-1) enables the nurse to be more astute in observations and assessments and more likely to identify early signs of complications. This allows for earlier intervention and promotes positive outcomes.

It is important for the nurse to have as much information as possible related to the prenatal and intrapartum history before starting to assess and provide nursing care for the newborn. Essential information is most often communicated from nurse to nurse through oral reports (see Table 21-1). The newborn’s medical record is a primary source of information. Data from the mother’s medical record provide insights into potential risk factors that can affect the newborn’s health. Through interaction with the mother and family, the nurse gains a greater understanding of neonatal and family needs. Assessment is ongoing throughout the hospital stay and extends into follow-up care.

Assessment

Initial Assessment and Apgar Scoring

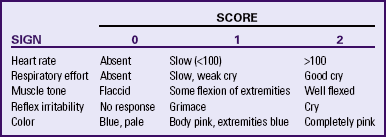

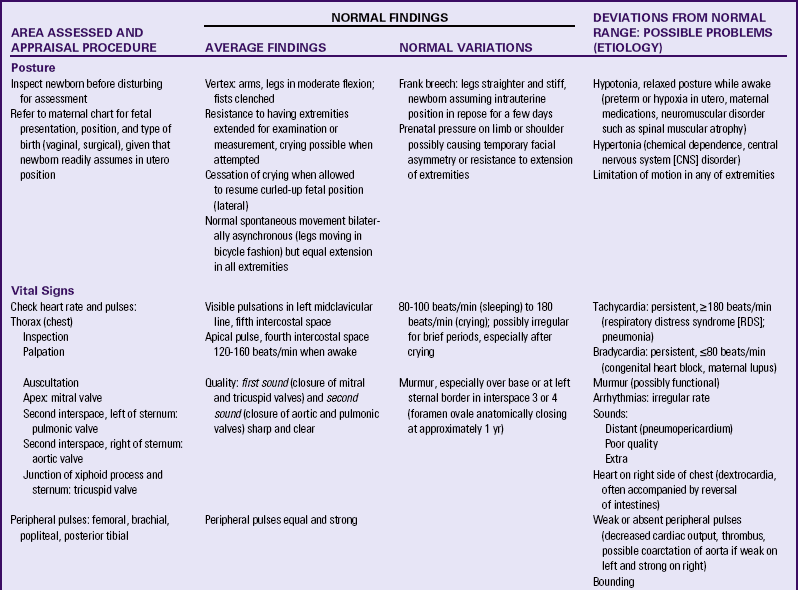

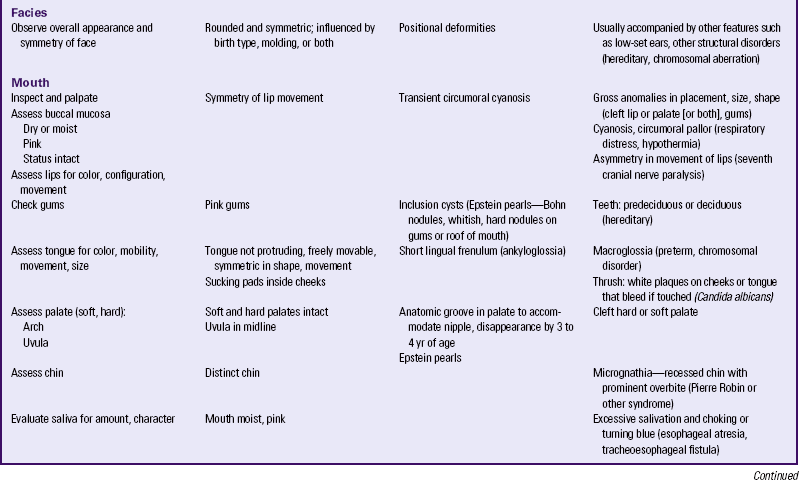

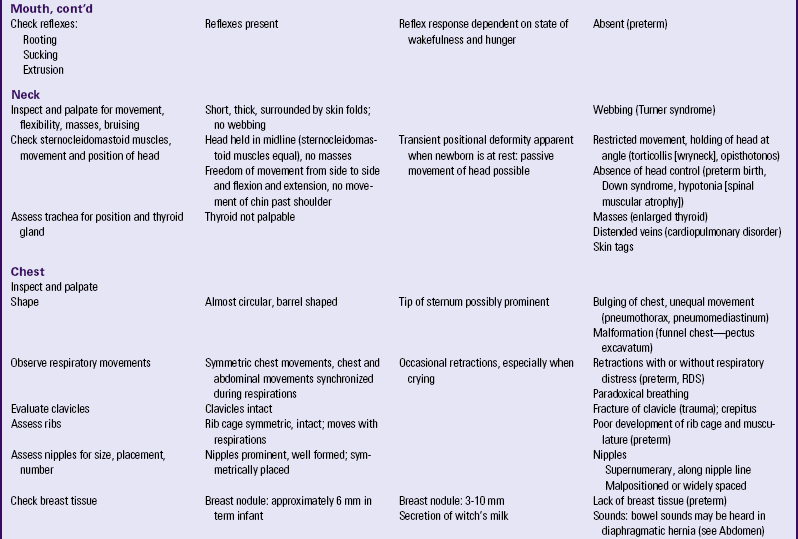

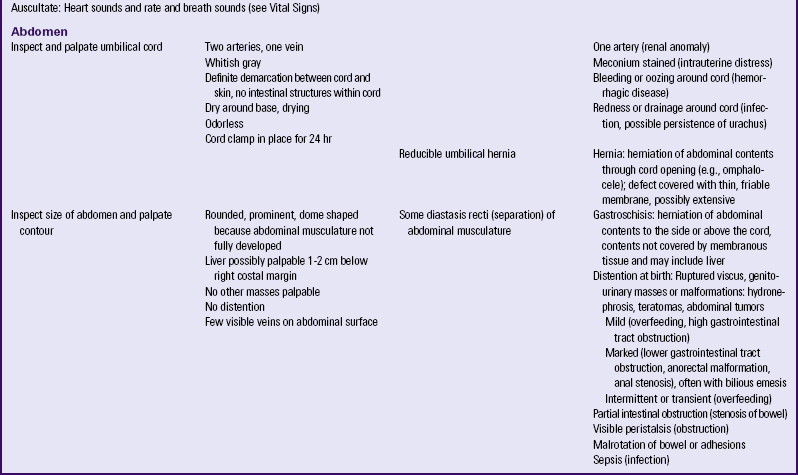

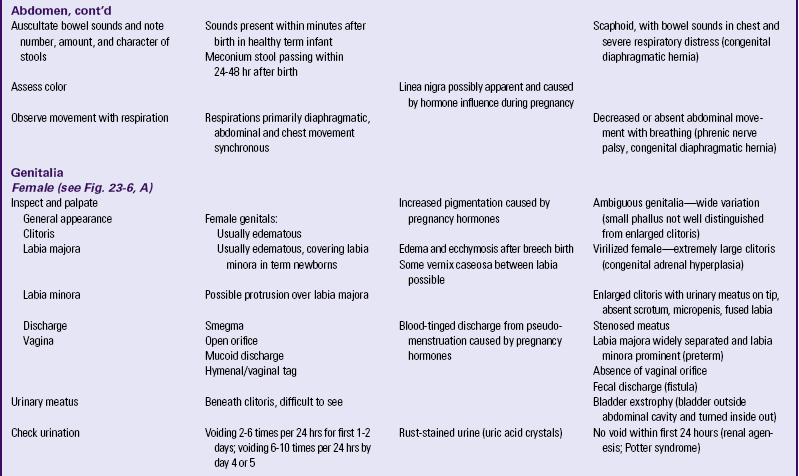

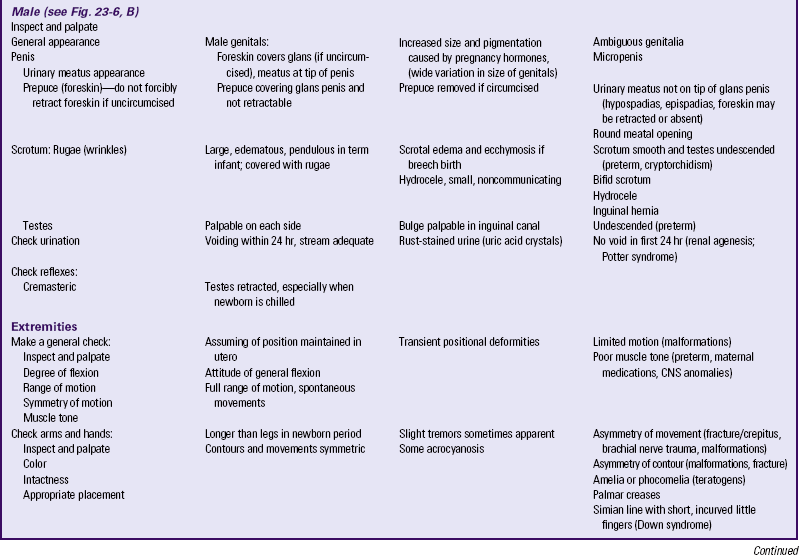

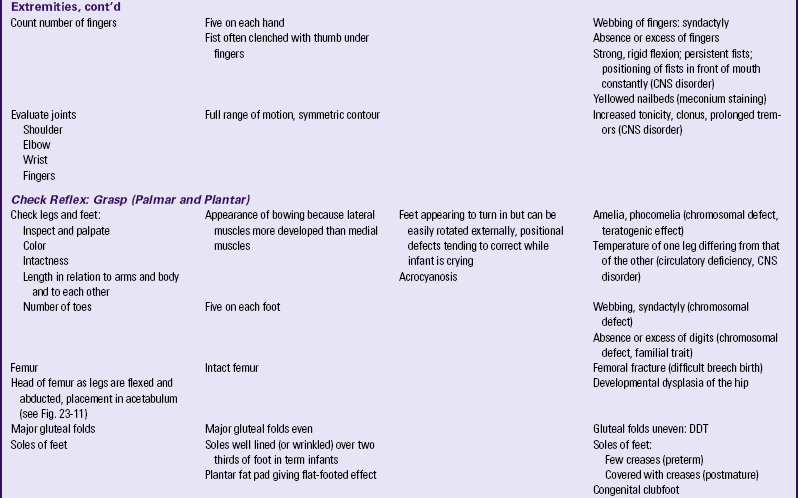

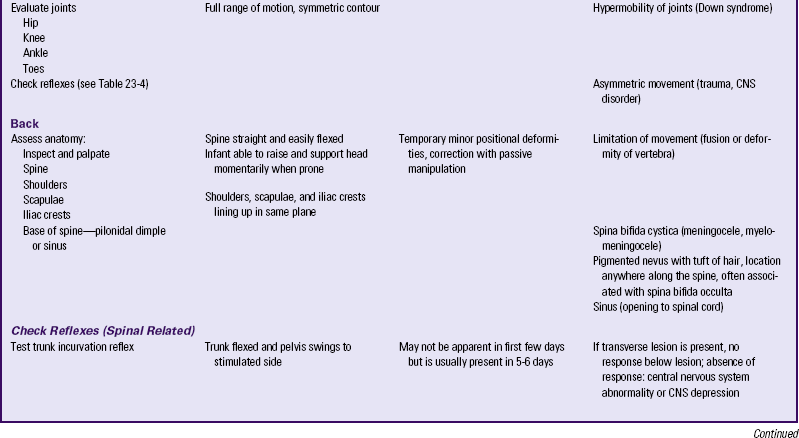

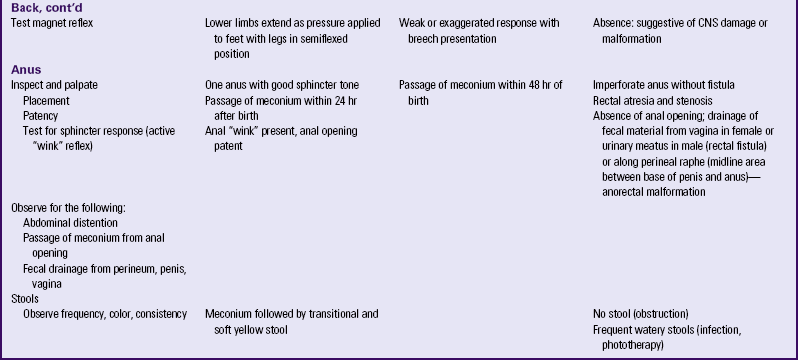

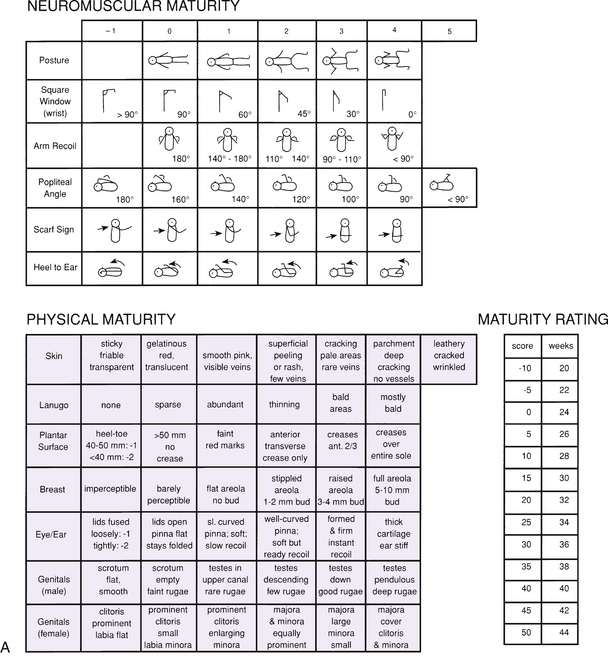

The initial assessment of the neonate is performed immediately after birth using the Apgar score (Table 24-1) and a brief physical examination (Box 24-2). A gestational age assessment is completed within the first hours of birth in a stable newborn (Fig. 24-1). A more comprehensive physical assessment is completed within 24 hours of birth (see Table 24-2).

FIG. 24-1 Estimation of gestational age. A, New Ballard Score for newborn maturity rating. Expanded scale includes extremely premature infants and has been refined to improve accuracy in more mature infants. (From Ballard, J., Khoury, J., Wang, L., Eilers-Walsman, B., & Lipp, R. [1991]. New Ballard score, expanded to include extremely premature infants, Journal of Pediatrics, 119[3], 424.) B, Intrauterine growth: birth weight percentiles based on live single births at gestational ages 20 to 44 weeks. (Data from Alexander, G., Himes, J., Kaufman, R., Mor, J., & Kogan, M. [1996]. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 87[2], 163-168.)

Apgar Score

The Apgar score permits a rapid assessment of the newborn’s transition to extrauterine existence based on five signs that indicate the physiologic state of the neonate: (1) heart rate, based on auscultation with a stethoscope or palpation of the umbilical cord; (2) respiratory effort, based on observed movement of the chest wall; (3) muscle tone, based on degree of flexion and movement of the extremities; (4) reflex irritability, based on response to suctioning of the nares or nasopharynx; and (5) generalized skin color, described as pallid, cyanotic, or pink (see Table 24-1). Evaluations are made at 1 and 5 minutes after birth and can be completed by the nurse or birth attendant. Scores of 0 to 3 indicate severe distress, scores of 4 to 6 indicate moderate difficulty, and scores of 7 to 10 indicate that the infant is having minimal or no difficulty adjusting to extrauterine life. Apgar scores do not predict future neurologic outcome but are useful for describing the newborn’s transition to the extrauterine environment (Box 24-3). If resuscitation is required it should be initiated before the 1-minute Apgar score (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2007).

Initial Physical Assessment

The initial examination of the newborn (see Box 24-2) can occur while the nurse is drying and wrapping the infant, or observations can be made while the infant is lying on the mother’s abdomen or in her arms immediately after birth. Efforts should be directed toward minimizing interference in the initial parent-infant acquaintance process. If the infant is breathing effectively, is pink, and has no apparent life-threatening anomalies or risk factors requiring immediate attention (e.g., infant of a mother with diabetes), further examination can be delayed until after the parents have had an opportunity to interact with the infant. Routine procedures and the admission process can be carried out in the mother’s room or in a separate nursery.

Physical Assessment

Although the initial assessment following birth can reveal significant anomalies, birth injuries, and cardiopulmonary problems that have immediate implications, a more detailed, thorough physical examination should follow within 12 to 18 hours after birth (Box 24-4; see Table 24-2). The parents’ presence during this and other examinations encourages discussion of their concerns and actively involves them in the health care of their infant from birth. It also affords the nurse an opportunity to observe parental interactions with the infant. The findings provide a database for implementing the nursing process with newborns and providing anticipatory guidance for the parents. Ongoing assessments are made throughout the hospital stay; another detailed physical examination is performed before discharge.

General Appearance

The neonate’s maturity level can be gauged by assessment of general appearance. Features to assess in the general survey include posture, activity, any overt signs of anomalies that can cause initial distress, presence of bruising or other consequences of birth, and state of alertness. The normal resting position of the neonate is one of general flexion.

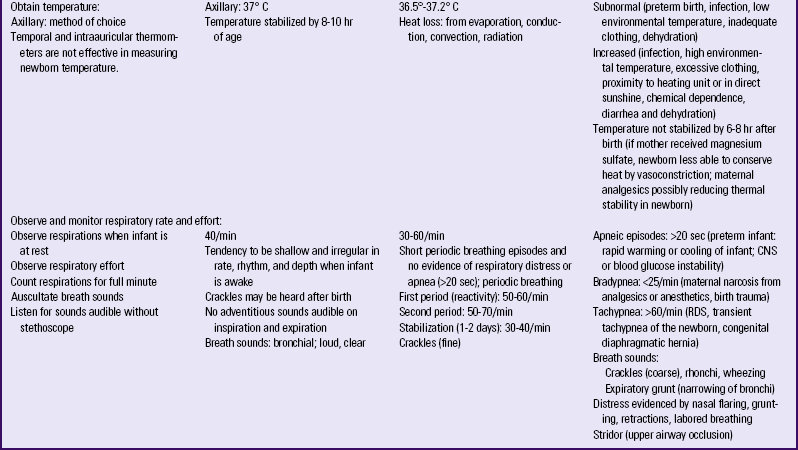

Vital Signs

The temperature, heart rate, and respiratory rate are always obtained. BP is not assessed unless cardiac problems are suspected. An irregular, very slow, or very fast heart rate can indicate a need for further evaluation of circulatory status including BP measurement.

The axillary temperature is a safe, accurate measurement of temperature. Electronic thermometers have expedited this task and provide a reading within 1 minute. Temporal artery, tympanic, and oral routes for measuring temperature in the newborn are not considered accurate (Asher & Northington, 2008). Taking an infant’s temperature can cause the infant to cry and struggle against the placement of the thermometer in the axilla. Before taking the temperature the examiner can determine the apical heart rate and respiratory rate while the infant is quiet and at rest. The normal axillary temperature averages 37° C with a range from 36.5° to 37.2° C.

The respiratory rate varies with the state of alertness and activity after birth. Respirations are abdominal in nature and can be counted by observing or lightly feeling the rise and fall of the abdomen. Neonatal respirations are shallow and irregular. The respirations should be counted for a full minute to obtain an accurate count because there are periods when respirations can cease for seconds (≤20) and resume again. The examiner should also observe for symmetry of chest movement. The average respiratory rate is 40 breaths/min but will vary between 30 and 60 breaths/min; respiratory rate can exceed 60 breaths/min if the newborn is very active or crying.

An apical pulse rate should be obtained on all newborns. Auscultation should be for a full minute, preferably when the infant is asleep or in a quiet alert state. The infant may need to be held and comforted during assessment. Heart rate can increase with birth and remain higher during the first hour. When the infant’s condition has stabilized, the normal heart rate ranges from 120 to 160 beats/min (Blackburn, 2007). Brachial and femoral pulses are assessed for equality and strength.

If BP is measured, an oscillometric monitor calibrated for neonatal pressures is preferred. An appropriate sized cuff (width-to-arm or calf ratio of 0.45 to 0.70 or approximately one half to three quarters) is essential for accuracy. Neonatal BP is usually highest immediately after birth and falls to a minimum by 3 hours after birth. It then begins to rise steadily and reaches a plateau between 4 and 6 days after birth. This measurement is usually equal to that of the immediate postbirth BP. The BP varies with the neonate’s activity; accurate measurement is best obtained while the newborn is at rest.

Prior to the infant’s discharge from the birth institution a baseline pulse oximetry measurement may be obtained along with palpation of peripheral pulses (brachial, femoral, pedal), especially if a congenital cardiac defect is suspected.

Baseline Measurements of Physical Growth

Baseline measurements are taken and recorded to help assess the progress and determine the growth patterns of the neonate. These measurements may be recorded on growth charts. The following measurements are made when the neonate is assessed.

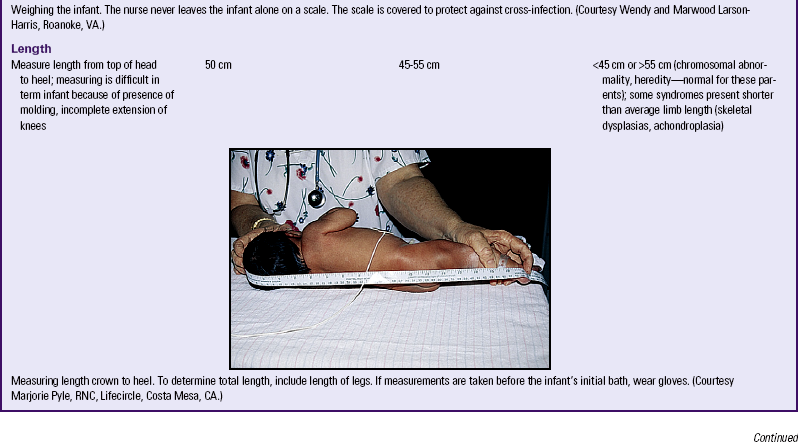

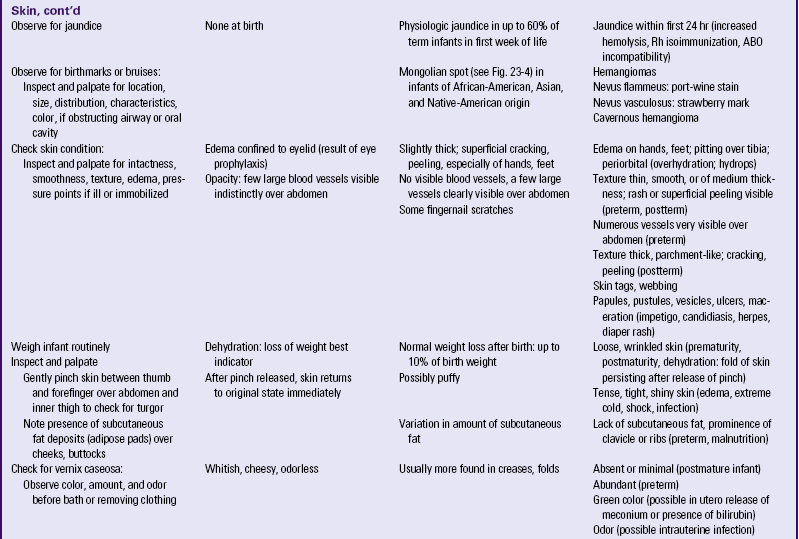

Weight: The newborn is usually weighed shortly after birth. This assessment can be performed in the labor and birthing area, the mother’s room, or on admission to the nursery. Care must be taken to ensure that the scales are balanced. The totally unclothed neonate is placed in the center of the scale, which is usually covered with a disposable pad or cloth to prevent heat loss via conduction and to prevent cross-infection. The nurse should place one hand over (but not touching) the neonate to prevent the infant from falling off the scales. Weighing the infant at the same time every day is common during the hospital stay. Birth weight of a term infant typically ranges from 2500 to 4000 g.

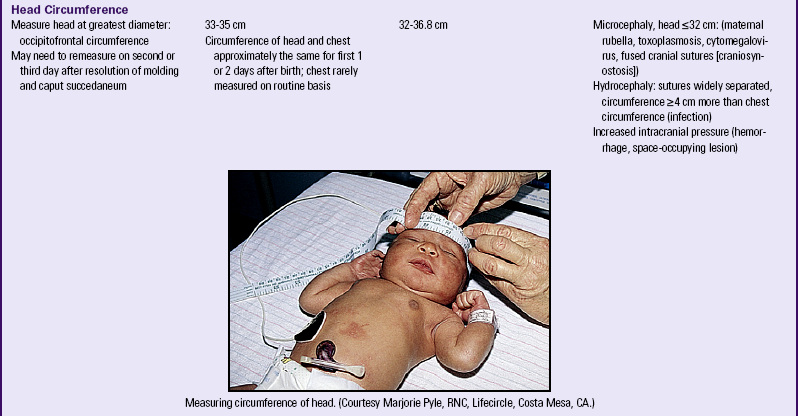

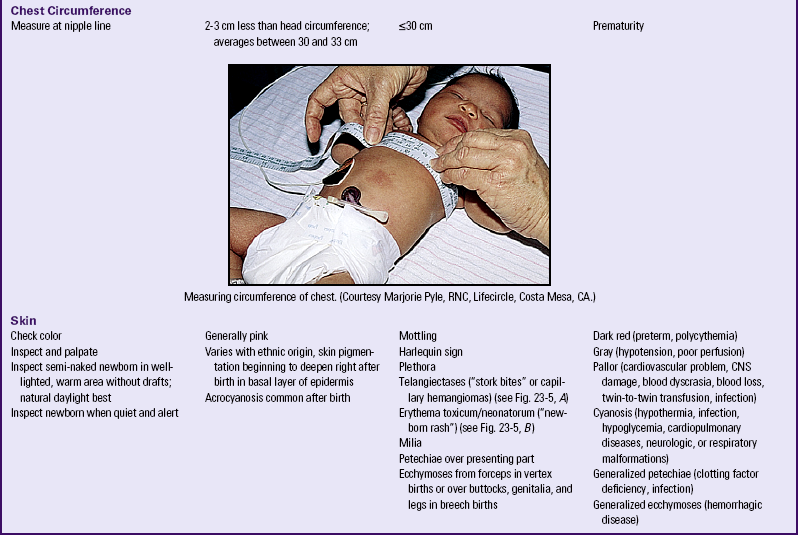

Head Circumference and Body Length: The head is measured at the widest part, which is the occipitofrontal diameter. The tape measure is placed around the head just above the infant’s eyebrows. The term neonate’s head circumference ranges from 32 to 36.8 cm.

The length may be difficult to obtain because of the flexed posture of the newborn. The examiner places the newborn on a flat surface and extends the leg until the knee is flat against the surface. Placing the head against a perpendicular surface and extending the leg may assist with obtaining this measurement. In the term neonate, head-to-heel length ranges from 45 to 55 cm.

Neurologic Assessment

The physical examination includes a neurologic assessment of newborn reflexes (see Table 23-3). This assessment provides useful information about the infant’s nervous system and state of neurologic maturation. Many reflex behaviors (e.g., sucking, rooting) are important for proper development. Other reflexes such as gagging and sneezing act as primitive safety mechanisms. The assessment needs to be carried out as early as possible because abnormal signs present in the early neonatal period may require further investigation before the newborn is discharged home.

Gestational Age Assessment

Assessment of gestational age is important because perinatal morbidity and mortality rates are related to gestational age and birth weight. A frequently used method of determining gestational age is the simplified Assessment of Gestational Age scale (Ballard, Novak, & Driver, 1979) (see Fig. 24-1, A). This scale, an abbreviated version of the Dubowitz scale, can be used to measure gestational ages of infants between 35 and 42 weeks. It assesses six external physical and six neuromuscular signs. Each sign has a numerical score, and the cumulative score correlates with a maturity rating of 26 to 44 weeks of gestation.

The New Ballard Score, a revision of the original scale, can be used with newborns as young as 20 weeks of gestation. The tool has the same physical and neuromuscular sections but includes −1 to −2 scores that reflect signs of extremely premature infants, such as fused eyelids; imperceptible breast tissue; sticky, friable, transparent skin; no lanugo; and square-window (flexion of wrist) angle greater than 90 degrees (see Fig. 24-1, A). The examination of infants with a gestational age of 26 weeks or less should be performed at a postnatal age of less than 12 hours. For infants with a gestational age of at least 26 weeks the examination can be performed up to 96 hours after birth. To ensure accuracy, experts recommend that the initial examination be performed within the first 48 hours of life. Neuromuscular adjustments after birth in extremely immature neonates require that a follow-up examination be performed to further validate neuromuscular criteria (Ballard, Khoury, Wedig, Wang, Eilers-Walsman, & Lipp, 1991). Box 24-5 highlights specific maneuvers used in gestational age assessment.

Classification of Newborns by Gestational Age and Birth Weight

Classification of infants at birth by both birth weight and gestational age provides a more satisfactory method for predicting mortality risks and providing guidelines for management of the neonate than estimating gestational age or birth weight alone. The infant’s birth weight, length, and head circumference are plotted on standardized graphs that identify normal values for gestational age. A normal range of birth weights exists for each gestational week (see Fig. 24-1, B).

Intrauterine growth curves developed by Battaglia and Lubchenco (1967) have been used to classify infants according to birth weight and gestational age. Other intrauterine growth charts have been developed to reflect a more heterogeneous sample population than previously described. The primary intrauterine growth charts that provide national reference data include the work of Alexander and associates (1996), which is representative of more than 3.1 million live births in the United States; the work of Thomas and colleagues (2000); Arbuckle and coworkers (1993); and Kramer and colleagues (2001), which are representative of intrauterine growth among the Canadian population. Thomas and colleagues concluded that intrauterine growth measured by head circumference, birth weight, and length varies according to race and sex. These researchers also found that altitude did not seem to affect birth weight significantly, as has been suggested by other authors. In one study, Asian and Hispanic newborns had lower mean birth weights, shorter mean lengths, and smaller mean head circumferences than Caucasian newborns (Madan, Holland, Humbert, & Benitz, 2002). The reader should access and use the most current intrauterine growth chart specific to the referent population being evaluated, especially when considering multiples such as twins.

The infant whose weight is appropriate for gestational age (AGA) (between the 10th and 90th percentiles) can be presumed to have grown at a normal rate regardless of the length of gestation—preterm, term, or postterm. The infant who is large for gestational age (LGA) (more than the 90th percentile) can be presumed to have grown at an accelerated rate during fetal life; the small-for-gestational-age (SGA) infant (less than the 10th percentile) can be presumed to have grown at a restricted rate during intrauterine life. When gestational age is determined according to the New Ballard Score, the newborn will fall into one of the following nine possible categories for birth weight and gestational age: AGA—term, preterm, postterm; SGA—term, preterm, postterm; or LGA—term, preterm, postterm. Birth weight influences mortality: the lower the birth weight, the higher the mortality. The same is true for gestational age: the lower the gestational age, the higher the mortality (Stoll, 2007).

Infants may also be classified in the following ways according to gestation:

• Preterm or premature—born before completion of 37 weeks of gestation, regardless of birth weight

• Late preterm—born between 34 0/7 and 36 6/7 weeks

• Term—born between the end of week 37 and the end of week 42 of gestation

• Postterm (postdate)—born after completion of week 42 of gestation

• Postmature—born after completion of week 42 of gestation and showing the effects of progressive placental insufficiency

Late Preterm Infant

Attention has been focused on infants who are considered “late preterm.” These infants are often the size and weight of term infants and may be admitted to the healthy newborn nursery and treated as healthy newborns. Late preterm infants, born at 34 0/7 to 36 6/7 weeks of gestation, have risk factors resulting from their physiologic immaturity that require close attention by nurses working with such infants (Bakewell-Sachs, 2007). These risk factors include the tendency to develop respiratory distress, temperature instability, hypoglycemia, apnea,

feeding difficulties, jaundice, and hyperbilirubinemia. Nurses working with healthy term infants must be cognizant of the risk factors for late preterm infants and be continually vigilant for the development of problems related to the infant’s immaturity. The late preterm infant’s care is further addressed in Chapter 37.

Interventions

Changes can occur quickly in newborns immediately after birth. Assessment must be followed by the implementation of appropriate care. The nursing process in the immediate care of the newborn and family is outlined in the Nursing Process box.

Airway Maintenance

Generally the healthy term infant born vaginally has little difficulty clearing the airway. Most secretions are moved by gravity and brought by the cough reflex to the oropharynx to be drained or swallowed. The infant is often maintained in a side-lying position (head stabilized, not in the Trendelenburg position) with a rolled blanket at the back to facilitate drainage.

If the infant has excess mucus in the respiratory tract, the mouth and nasal passages can be gently suctioned with a bulb syringe (see the Procedure box: Suctioning with a Bulb Syringe; Fig. 24-2). Routine chest percussion and suctioning of healthy term or late preterm infants is avoided; evidence is insufficient to support anything other than gentle nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal suctioning to clear secretions (Hagedorn, 2006). The nurse should listen to the infant’s respirations and lung sounds with a stethoscope to determine if crackles or inspiratory stridor is present. Fine crackles may be auscultated for several hours after birth. If the bulb syringe does not clear mucus interfering with respiratory effort, mechanical suction can be used.

FIG. 24-2 Bulb syringe. Bulb must be compressed before insertion. (Courtesy Cheryl Briggs, RNC, Annapolis, MD.)

If the newborn has an obstruction that is not cleared with suctioning, the health care provider should be notified. Further investigation must occur to determine if a mechanical defect (e.g., tracheoesophageal fistula, choanal atresia [see Chapter 36]) is causing the obstruction.

Deeper suctioning may be needed to remove mucus from the newborn’s nasopharynx or posterior oropharynx. However, this type of suctioning should be performed only after an assessment of the risks involved. This procedure can be repeated until the infant has a clear airway (see the Procedure box: Suctioning with a Nasopharyngeal Catheter with Mechanical Suction Apparatus).

Maintaining an Adequate Oxygen Supply

Four conditions are essential for maintaining an adequate oxygen supply:

• Effective establishment of respirations

• Adequate circulation, adequate perfusion, and effective cardiac function

• Adequate thermoregulation (exposure to cold stress increases oxygen and glucose needs.)

Newborns who encounter respiratory problems are likely to exhibit signs and symptoms that indicate some degree of distress. Preterm infants are at greatest risk for respiratory distress (see the Signs of Potential Complications box; see also Chapter 37).

Maintaining Body Temperature

Effective neonatal care includes maintenance of a neutral thermal environment (see Chapter 23). Cold stress increases the need for oxygen and can deplete glucose stores. The infant may react to exposure to cold by increasing the respiratory rate and may become cyanotic. Ways to stabilize the newborn’s body temperature include placing the infant directly on the mother’s chest and covering with a warm blanket (skin-to-skin contact), drying and wrapping the newborn in warmed blankets immediately after birth, keeping the head well covered, and keeping the ambient temperature of the nursery or mother’s room at 22° to 26° C (AAP & ACOG, 2007).

If the infant does not remain with the mother during the first 1 to 2 hours after birth, the nurse places the thoroughly dried infant under a radiant warmer or in a warm incubator until the body temperature stabilizes. The infant’s skin temperature is used as the point of control in a warmer with a servo-controlled mechanism. The control panel is usually maintained between 36° and 37° C. This setting should maintain the healthy term newborn’s skin temperature at approximately 36.5° to 37° C. A thermistor probe (automatic sensor) is usually placed on the upper quadrant of the abdomen immediately below the right or left costal margin (never over a bone). A reflector adhesive

patch can be used over the probe to provide adequate warming. This probe will ensure detection of minor temperature changes resulting from external environmental factors or neonatal factors (peripheral vasoconstriction, vasodilation, or increased metabolism) before a dramatic change in core body temperature develops. The servo-controller adjusts the temperature of the warmer to maintain the infant’s skin temperature within the preset range. The sensor needs to be checked periodically to make sure it is securely attached to the infant’s skin. The axillary temperature of the newborn is checked every hour (or more often as needed) until the newborn’s temperature stabilizes. The length of time to stabilize and maintain body temperature varies; each newborn should therefore be allowed to achieve thermal regulation as necessary, and care should be individualized.

During all procedures, heat loss must be avoided or minimized for the newborn; therefore, examinations and activities are performed with the newborn under a heat panel. The initial bath is postponed until the newborn’s skin temperature is stable and can adjust to heat loss from a bath. The exact and optimal timing of the bath for each newborn remains unknown.

Even a healthy term infant can become hypothermic. Inadequate drying and wrapping immediately after birth, a cold birthing room, or birth in a car on the way to the hospital can cause the newborn’s temperature to fall below the normal range (hypothermia). The hypothermic infant should be warmed gradually because rapid warming can cause apneic spells and acidosis. Therefore, the warming process is monitored to progress slowly over 2 to 4 hours.

Immediate Interventions

One of the nurse’s responsibilities is to perform certain interventions soon after birth to provide for the safety and well-being of the newborn.

Eye Prophylaxis

The instillation of a prophylactic agent in the eyes of all neonates (Fig. 24-3) is mandatory in the United States. This is a precautionary measure against ophthalmia neonatorum, which is an inflammation of the eyes resulting from gonorrheal or chlamydial infection contracted by the newborn during passage through the mother’s birth canal. In the United States, if parents object to this treatment, they can be asked to sign an informed refusal form, and their refusal is documented in the neonate’s record. The agent used for prophylaxis varies according to hospital protocols, but usually includes forms of erythromycin, tetracycline, or silver nitrate (see the Medication Guide: Eye Prophylaxis). Canadian hospitals have not recommended the use of silver nitrate since 1986. Its use in the United States is minimal because silver nitrate does not protect against chlamydial infection and can cause chemical conjunctivitis. Instillation of eye prophylaxis can be delayed until an hour or so (up to 2 hours in Canada) after birth so that eye contact and parent-infant attachment and bonding are facilitated.

FIG. 24-3 Instillation of medication into eye of newborn. Thumb and forefinger are used to open the eye; medication is placed in the lower conjunctiva from the inner to the outer canthus. (Courtesy Marjorie Pyle, RNC, Lifecircle, Costa Mesa, CA.)

Topical antibiotics such as tetracycline and erythromycin, silver nitrate, and a 2.5% povidone-iodine solution are not effective in the treatment of chlamydial conjunctivitis. A 14-day course of oral erythromycin or an oral sulfonamide can be given for chlamydial conjunctivitis (AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases, 2009).

Vitamin K Prophylaxis

Administering vitamin K intramuscularly is routine in the newborn period in the United States. A single intramuscular injection of 0.5 to 1 mg of vitamin K is given soon after birth to prevent hemorrhagic disease of the newborn. Administration

can be delayed until after the first breastfeeding in the birthing room (AAP & ACOG, 2007). Vitamin K is synthesized by intestinal flora, which are not present at birth. The introduction of bacteria begins with the first feedings and by the age of seven days, healthy newborns are able to produce their own vitamin K (see the Medication Guide: Vitamin K).

Umbilical Cord Care

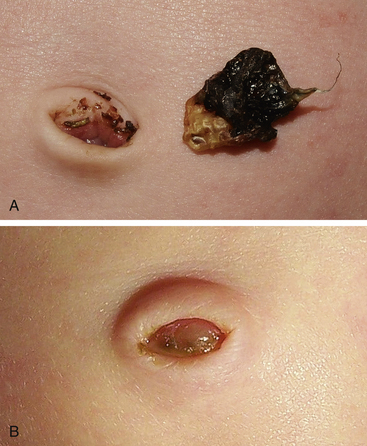

The cord is clamped immediately after birth. The cord clamp is removed once the stump has started drying and is no longer bleeding (Fig. 24-4), typically in 24 hours.

FIG. 24-4 With special tool, remove clamp after cord dries (approximately 24 hours). (Courtesy Cheryl Briggs, RNC, Annapolis, MD.)

The goal of cord care is to prevent or decrease the risk of hemorrhage and infection. The umbilical cord stump is an excellent medium for bacterial growth and can easily become infected. Hospital protocol determines the technique for routine cord care. Common methods include the use of an antimicrobial agent such as bacitracin or triple dye, although some experts advocate the use of alcohol alone, soap and water, sterile water, povidone-iodine, or no treatment (natural healing). A one-time application of triple dye has been shown to be superior to alcohol, povidone-iodine, or topical antibiotics in reducing colonization or infection; the use of alcohol is associated with prolonged cord drying and separation (McConnell, Lee, Couillard, & Sherrill, 2004; Zupan, Garner, & Omari, 2004). Current recommendations for cord care by the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN, 2007) include cleaning the cord with sterile water initially and subsequently with plain water.

The stump and base of the cord should be assessed for edema, redness, and purulent drainage with each diaper change. The nurse or parent cleanses the cord and skin area around the base of the cord with the prescribed preparation (e.g., sterile water, erythromycin solution, or triple dye). The stump deteriorates through the process of dry gangrene; therefore odor alone is not a positive indicator of omphalitis (infection of the umbilical stump). Cord separation time is influenced by several factors, including type of cord care, type of birth, and other perinatal events. The average cord separation time is 10 to 14 days. Some dried blood may be seen in the umbilicus at separation (Fig. 24-5).

Promoting Parent-Infant Interaction

Today’s childbirth practices promote the family as the focus of care. Parents generally desire to share in the birth process and to have early contact with their infants. The infant can be put to breast soon after birth. Early contact between mother and newborn can be important in developing future relationships; it also has a positive effect on the initiation and duration of breastfeeding. Early mother-infant contact produces physiologic benefits for the mother and neonate. Maternal levels of oxytocin and prolactin rise with early breastfeeding. The process of developing active immunity begins as the infant ingests antibodies from the mother’s colostrum.

Care Management: from 2 Hours After Birth Until Discharge

In an effort to provide more family-centered care, many hospitals have adopted variations of single-room maternity care (SRMC) or mother-baby (couplet) care in which the same nurse provides care for the mother and newborn. SRMC allows the infant to remain with the parents after the birth. Many of the procedures, such as assessment of weight and measurement, of head and circumference length, instillation of eye medication, administration of vitamin K, and physical assessment, are carried out in the labor and birth unit. Nurses who work in an SRMC unit; a labor, delivery, and recovery (LDR) unit; or a labor, delivery, recovery, and postpartum (LDRP) unit must be educated and competent in providing intrapartal, neonatal, and postpartum nursing care. If an infant is transferred to the nursery, the nurse receiving the newborn verifies the infant’s identification, places the baby in a warm environment, and begins the admission process.

Common Newborn Problems

Birth trauma includes any physical injury sustained by a newborn during labor and birth. Although most injuries are minor and resolve during the neonatal period without treatment, some types of trauma require intervention; a few are serious enough to be fatal. (See Chapter 35 for more information on birth injuries.)

Soft Tissue Injuries

Subconjunctival and retinal hemorrhages result from rupture of capillaries caused by increased pressure during birth. These hemorrhages usually clear within 5 days after birth and present no further problems. Parents need explanation and reassurance that these injuries are harmless.

Erythema, ecchymoses, petechiae, abrasions, lacerations, or edema of the buttocks and extremities can be present. Localized discoloration can appear over the presenting part as a result of forceps- or vacuum-assisted birth. Ecchymoses and edema can appear anywhere on the body. Petechiae (pinpoint hemorrhagic areas) acquired during birth can extend over the upper trunk and face. These lesions are benign if they disappear within 2 or 3 days of birth and no new lesions appear. Ecchymoses and petechiae can be signs of a more serious disorder, such as thrombocytopenic purpura. To differentiate hemorrhagic areas from a skin rash or discolorations, try to blanch the skin with two fingers. Petechiae and ecchymoses will not blanch because extravasated blood remains within the tissues, whereas skin rashes and discolorations do blanch.

Trauma can occur during labor and birth to the presenting fetal part. Caput succedaneum and cephalhematoma are discussed in Chapter 23 (see Fig. 23-9). Forceps injury and bruising from the vacuum cup occur at the site of application of the instruments. A forceps injury commonly produces a linear mark across both sides of the face in the shape of the blades of the forceps. The affected areas are kept clean to minimize the risk of infection. These injuries usually resolve spontaneously within several days with no specific therapy. With the increased use of the vacuum extractor and the use of padded forceps blades, the incidence of these lesions can be significantly reduced.

Bruises over the face can be the result of face presentation (Fig. 24-6). In a breech presentation, bruising and swelling may be seen over the buttocks or genitalia (see Fig. 23-7). The skin over the entire head can be ecchymotic and covered with petechiae caused by a tight nuchal cord. If the hemorrhagic areas do not disappear spontaneously in 2 days, or if the infant’s condition changes, the primary health care provider is notified.

FIG. 24-6 Marked bruising on the entire face of an infant born vaginally after face presentation. Less severe ecchymoses were present on the extremities. Phototherapy was required for treatment of jaundice resulting from the breakdown of accumulated blood. (From O’Doherty, N. [1986]. Neonatology: Micro atlas of the newborn. Nutley, NJ: Hoffman-LaRoche.)

Accidental lacerations can be inflicted with a scalpel during a cesarean birth. These cuts may occur on any part of the body but are most often found on the scalp, buttocks, and thighs. They are usually superficial and need only to be kept clean. Butterfly adhesive strips will hold together the edges of more serious lacerations. Rarely are sutures needed.

Physiologic Problems

Physiologic Jaundice: Every newborn is assessed for jaundice. To differentiate cutaneous jaundice from normal skin color, the nurse applies pressure with a finger over a bony area (e.g., the nose, forehead, sternum) for several seconds to empty all the capillaries in that spot. If jaundice is present, the blanched area will appear yellow before the capillaries refill. The conjunctival sacs and buccal mucosa also are assessed, especially in darker-skinned infants. Assessing for jaundice in natural light is recommended because artificial lighting and reflection from nursery walls can distort the actual skin color. Visual assessment of jaundice does not, however, provide an accurate assessment of the level of serum bilirubin.

Noninvasive monitoring of bilirubin using cutaneous reflectance measurements (transcutaneous bilirubinometry [TcB]) allows for repetitive estimations of bilirubin (Fig. 24-7). These devices work well on both dark- and light-skinned infants and demonstrate linear correlation with serum determinations of bilirubin levels in full-term infants. TcB monitors can be used to screen clinically significant jaundice and decrease the need for serum bilirubin measurements. The new TcB monitors provide accurate measurements within 2 to 3 mg/dl in most neonatal populations at serum levels below 15 mg/dl (AAP Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia, 2004). After phototherapy has been initiated, TcB is no longer useful as a screening tool.

FIG. 24-7 Transcutaneous monitoring of bilirubin with a transcutaneous bilirubinometry (TcB) monitor. (Courtesy Cheryl Briggs, RNC, Annapolis, MD.)

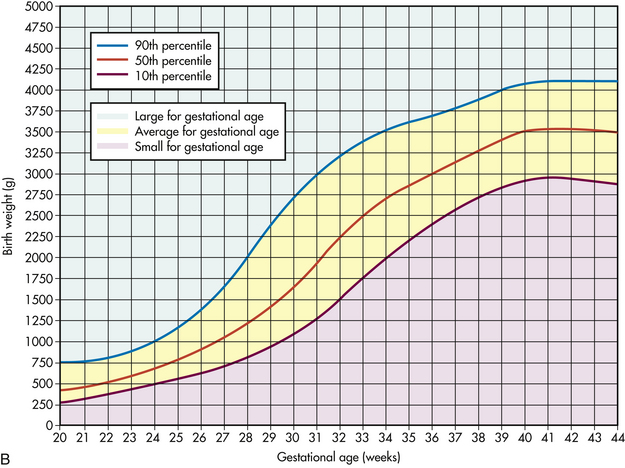

The use of hour-specific serum bilirubin levels to predict term newborns at risk for rapidly rising levels is an official recommendation by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia (2004) for the monitoring of healthy neonates at 35 weeks of gestation or greater before discharge from the hospital. Using a nomogram (Fig. 24-8) with three levels (high, intermediate, or low risk) of rising total serum bilirubin values assists in the determination of which newborns might need further evaluation after discharge. Universal bilirubin screening based on hour-specific total serum bilirubin can be performed at the same time as the routine newborn profile (phenylketonuria [PKU], galactosemia, and others) (AAP Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia). The hour-specific bilirubin risk nomogram is used to determine the infant’s risk for development of hyperbilirubinemia requiring medical treatment or closer screening. Studies have demonstrated the accuracy of the nomogram in predicting rapidly rising bilirubin levels requiring evaluation or treatment (Keren, Luan, Friedman, Saddlemire, Cnaan, & Bhutani, 2008).

FIG. 24-8 Nomogram for designation of risk in 2840 well newborns at 36 or more weeks of gestational age with birth weight of 2000 g or more or 35 or more weeks of gestational age and birth weight of 2500 g or more based on the hour-specific serum bilirubin values. (This nomogram should not be used to represent the natural history of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia.) (From Bhutani, V., Johnson, L., & Sivieri, E. [1999]. Predictive ability of a predischarge hour-specific serum bilirubin for subsequent significant hyperbilirubinemia in healthy term and near-term newborns. Pediatrics, 103[1], 6-14.)

The degree of jaundice is determined by serum bilirubin measurements. Normal values of unconjugated (indirect) bilirubin are 0.2 to 1.4 mg/dl. Normal values for total serum bilirubin range from 1 to 12 mg/dl (Pagana & Pagana, 2009).

An important point to remember is that the evaluation of jaundice is based not only on serum bilirubin and transcutaneous bilirubin levels but also on the timing of the appearance of clinical jaundice, gestational age at birth, age in hours since birth, family history that includes maternal blood type and Rh status and history of hyperbilirubinemia in a sibling, evidence of hemolysis, feeding method, the infant’s physiologic status, and the progression of serial serum bilirubin levels.

Factors recognized to place infants in the high risk category include gestational age less than 38 weeks, breastfeeding, previous sibling with significant jaundice, and jaundice appearing before discharge (AAP Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia, 2004). Experts recommend that healthy infants (35 weeks or greater) receive follow-up care and assessment of bilirubin within 3 days of discharge if discharged at less than 24 hours and a risk assessment with tools such as the hour-specific nomogram. Newborns discharged at 24 to 47.9 hours should receive follow-up evaluation within 4 days (96 hours), and those discharged between 48 and 72 hours should receive follow-up within 5 days (AAP Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia).

Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia in a term infant during the early newborn period is defined as a blood glucose concentration less than adequate to support neurologic, organ, and tissue function; however, the precise level at which this concentration occurs in every neonate is not known. Hypoglycemia that warrants treatment is usually defined as blood glucose levels less than 40 mg/dl, although some experts recommend treatment for levels less than 50 mg/dl(Sperling, 2007).

At birth the maternal source of glucose is cut off with the clamping of the umbilical cord. Most healthy term newborns experience a transient decrease in glucose levels, with a subsequent mobilization of free fatty acids and ketones to help maintain adequate glucose levels (Blackburn, 2007). Infants who are asphyxiated or have other physiologic stress can experience hypoglycemia as a result of a decreased glycogen supply, inadequate gluconeogenesis, or overutilization of glycogen stored during fetal life. There is concern about neurologic injury as a result of severe or prolonged hypoglycemia, especially in combination with ischemia (Volpe, 2008).

For the healthy full-term infant born after an uneventful pregnancy and birth, recommendations are to assess glucose levels only when risk factors are present or when there are clinical manifestations of hypoglycemia. The clinical signs of hypoglycemia can be transient or recurrent and include jitteriness, lethargy, poor feeding, hypotonia, temperature instability (hypothermia), respiratory distress, apnea, and seizures. It is important to remember that hypoglycemia can be present in the absence of clinical manifestations.

For infants who are at risk for hypoglycemia, close monitoring of blood glucose levels is recommended. Glucose levels should be measured within the first hour after birth and frequently thereafter until levels stabilize. Hospital protocols vary in the time intervals recommended for glucose monitoring. Risk factors for hypoglycemia include maternal diabetes, gestational hypertension, and tocolytic therapy. Neonatal risk factors include prematurity, LGA, SGA, perinatal hypoxia, infection, hypothermia, and congenital malformations.

Hypoglycemia in the low risk term infant is usually treated by feeding the infant a source of carbohydrate (i.e., human milk or formula). If the newborn has a blood glucose level less than 40 mg/dl and is asymptomatic, breastfeeding or bottle-feeding should be instituted. If levels remain low despite feeding, intravenous dextrose is warranted. In such infants the treatment should be aimed at maintaining the blood glucose levels above 45 mg/dl (2.5 mmol/L). For the neonate with clinical signs of hypoglycemia, regardless of cause or age, some experts recommend parenteral glucose infusion (Kalhan & Parimi, 2006). Experts further recommend that emphasis be placed less on an absolute glucose value but rather on promoting normoglycemia with interventions for less optimal values (Blackburn, 2007).

Hypocalcemia

Hypocalcemia is defined as serum calcium levels of less than 7.8 to 8 mg/dl in term infants and slightly lower (7 mg/dl) in preterm infants; ideally, ionized fraction levels reflect the biologically active form and levels range from 3 to 4.4 mg/dl depending on the measurement method (Blackburn, 2007). Hypocalcemia can occur in infants of mothers with diabetes or in those who had perinatal asphyxia or trauma, and in low-birth-weight and preterm infants. Early-onset hypocalcemia usually occurs within the first 24 to 48 hours after birth. Signs of hypocalcemia include jitteriness, high-pitched cry, irritability, apnea, intermittent cyanosis, abdominal distention, and laryngospasm, although some hypocalcemic infants are asymptomatic (Blackburn). Jitteriness is a symptom of both hypoglycemia and hypocalcemia; therefore, hypocalcemia must be considered if the therapy for hypoglycemia proves ineffective.

In most instances, early-onset hypocalcemia is self-limiting and resolves within 1 to 3 days. Treatment usually includes early feeding of an appropriate source of calcium such as fortified human milk or a preterm infant formula.