Chapter 4 Basic Pathology

The majority of injuries incurred during participation in sports activities are sprains, strains and contusions involving the musculo-skeletal system. The taping techniques demonstrated in this guide are particularly helpful for these conditions. Although some form of splinting and protection is also necessary for fractures, dislocations, nerve injuries, lacerations, abrasions and blisters, these conditions are beyond the intended scope of this guide.

In order to choose the appropriate tape and technique, you should first have a working knowledge of the repair process as it applies to the soft tissues. There are three recognized phases of healing.

1. The acute phase. This is the phase immediately following an injury which consists of an inflammatory process, to a greater or lesser degree, depending on the extent of the injury. During this phase, which lasts between 3 and 7 days,1,2 taping is aimed at compressing the injury site. This means that a stretch tape such as a cohesive bandage would be the tape of choice, or a Tubigrip. These will compress the site while allowing movement when the tissues swell. Care should be taken not to apply the bandage or Tubigrip too tightly and the patient should be advised to remove any bandaging that is too tight and seek immediate advice.

2. The proliferative phase, so called due to the proliferation of cells during this phase. This is also known as the regeneration or matrix phase, as this is when a loose matrix is laid down to effect a temporary repair to the tissues. This is the phase when tape is applied so that the tissues can be stressed without causing further damage. So we would opt for a stronger taping technique during this phase. The loose matrix is easily damaged but the tissues need to be stressed in order for them to form a strong matrix along the lines of force.

3. The remodelling phase is, as the name suggests, the phase in which the tissues reform to ‘normal’. No one at present knows when this phase is completed, as the cells of tissue repair have been found in and around an injury site up to 12 months after it was deemed that the injury had recovered.3 During this phase we would opt for taping techniques that allow greater movement while still offering support.

Tape is reported to lose 20–40% of its effectiveness by approximately 20 minutes after application.4,5 However, this does depend on the type of tape used.6 This is a very negative way of reporting statistics and if we look at these from another perspective, we could say that tape retains 60–80% of its effectiveness after 20 minutes. However, joint control is increased when muscles are warm and therefore, the stabilizing effect of tape is more important during the initial stages of training or competition,7 so we really only need tape to be maximally effective during this time.

We know that when athletes are fatigued there is a decrease in neuromotor control.8 Tape may offer support that could have a prophylactic role when the athlete is fatigued.

R.I.C.E.S

Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation, Support: this is a well-established protocol for initial first aid,9-13 the evidence for which is largely anecdotal.14,15 Regardless of this, it is one of the few aspects of treatment and rehabilitation that is agreed on by many therapists.16-18 There are some questions you should ask of yourself before recommending R.I.C.E.S. to a patient.

• What does rest mean for this patient? Does it mean complete rest? Does it mean rest from those activities that are likely to exacerbate, maintain or create a new injury? If the answer to the second question is yes, then what activities can they do?

• The use of ice at present is controversial.19-21 What do you expect from icing? Vasoconstriction? Vasodilation? Decreased pain? Does the site of the injury matter? Do superficial injuries need the same amount of icing time as deeper tissues? How long should you ice for and for what period of time?18,19 Should you ice on the injury? Proximal to it? Or distal to it?

• The evidence for compressing an injury is at best ambiguous.15,22,23 Many tapes, Tubigrips and braces will offer different levels of compression. Which one do you choose and why? Why do we compress the injury? How long do you need to compress the injury for? And for what period of time? How much compression is necessary?

• Many authors recommend elevating an injury. However, no evidence was found either for or against the use of such a treatment modality. How are you going to recommend that the patient elevate the injury site? Do they need to elevate a shoulder injury? How long should you elevate for and for what period of time?

• Support can take many guises; what type of support is going to be best for your patient?

STRUCTURES REQUIRING TAPING

The structures most often requiring taping are joints, ligaments, muscles, tendons and associated bony parts. The following brief description of these structures with specific taping considerations will help the beginner and serve as a review for the more advanced taper.

JOINTS

These are structures formed where two or more bones meet and move one on another. The movements of joints are controlled by ligaments, joint capsules, muscles, bone on bone and, of course, pathological factors. Friction is minimized by the smooth (hyaline) cartilage over the articulated surface of the bone and by the synovial fluid within the joint capsule of synovial joints.

Because of the complex interaction of muscles and tendons involved in joint movement, an injury to any link in the functional chain unbalances the entire structure; for example, a severe ankle injury can lead to compensatory misfiring of the hip muscles.24 This imbalance causes pain and varying degrees of further joint dysfunction. Therefore, in taping joints, the primary concern is to support and protect the injured structure. Reestablishing the joint’s delicate balance while optimizing mobility without shifting function and/or reliance to compensatory structures is also very important.

When a joint has been taped, the patient must go through specific functional movements to determine that joint balance has been restored and to evaluate compensatory stress. If the patient is an athlete then they should also perform sport-specific tasks. The patient should be able to perform all required motions without experiencing pain.

LIGAMENTS

These are non-elastic connective tissue structures that stabilize joints and reinforce joint capsules. When ligaments are stretched, torn or bruised, the resulting sprain requires careful taping in order to assist in establishing structural support and functional movement to the joint while preventing or reducing the threat of further injury to the ligament. Generally, a non-elastic taping application that appropriately restricts unwanted movement of the joint will allow the ligament to recover without further stress or trauma.

MUSCLE/TENDON UNITS

These are elastic contractile structures that produce movement of the musculo-skeletal system. An elastic taping application provides resilient support while limiting full stretch of the injured structure. Elastic tape also allows normal changes in structure girth while maintaining compression; thus vital circulation to the area involved is not jeopardized.

BONY PROMINENCES

These are superficial bony areas with little overlying soft tissue. These areas require special care when taping as the prominent points easily develop skin blisters and abrasions under tape because they lack significant subcutaneous protection.

If tape strips are applied too tightly over these areas, the compression can result in compromised circulation, neural compression or acute pain leading to impaired performance.

USEFUL MNEMONIC FOR ASSESSMENT

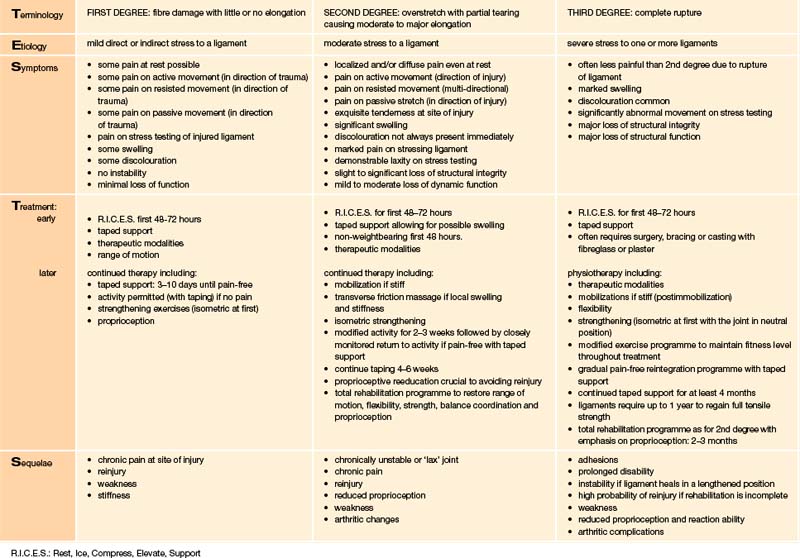

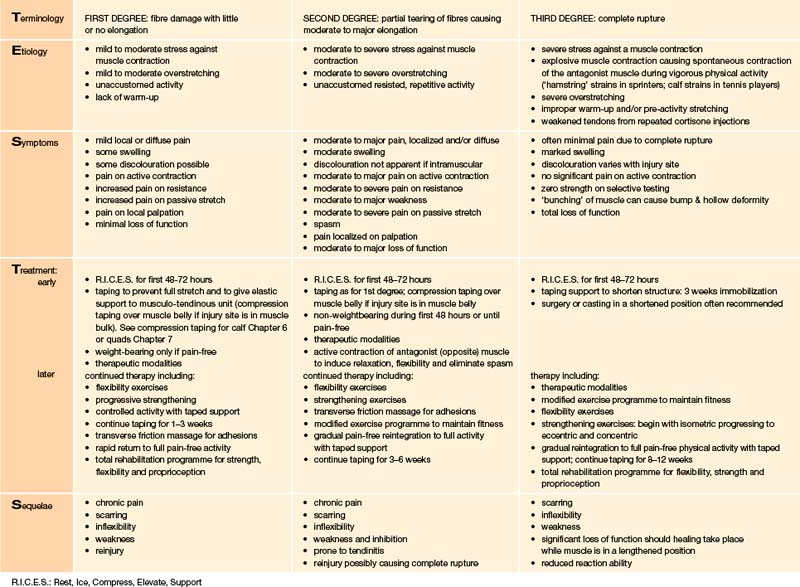

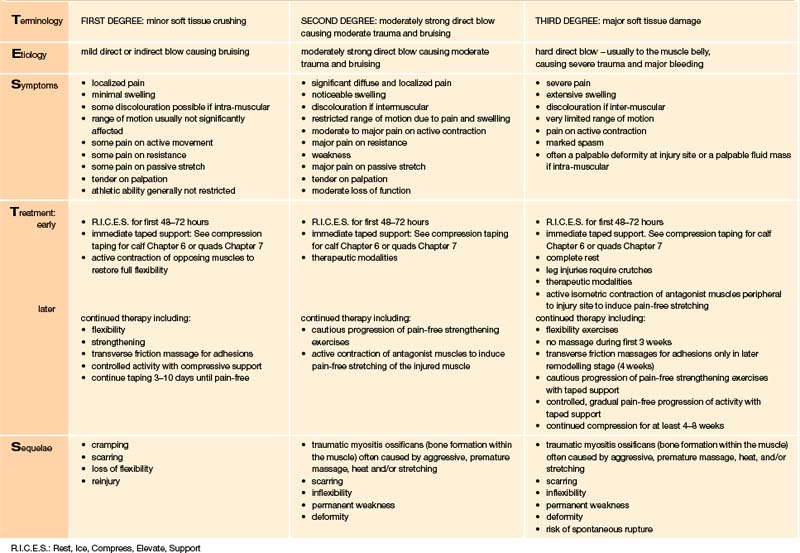

As discussed in Chapter Three, before beginning any taping procedure it is important to assess the injured region in order to determine the most appropriate treatment and taping application. The following material is presented in a format designed to facilitate a simple, quick assessment of the degree of injury in three areas: sprains, strains and contusions (bruising). Similar charts for specific injuries are included in Chapters Six to Nine following each of the taping techniques illustrated. Should there be any uncertainty concerning the severity of any particular condition, further medical evaluation and investigation must be sought. It is the responsibility of the taper to recommend such further medical care.

We have devised a simple order of assessment steps with a mnemonic to assist the reader. T.E.S.T.S. stands for:

T TERMINOLOGY: proper names, synonyms and other pertinent information for identifying an injury condition.

E ETIOLOGY: relative mechanisms, causative factors, prevalence.

S SYMPTOMS: subjective complaints of the injured patient including a description of the injury; objective physical findings which can be measured by the taper.

T TREATMENT: includes early and later phases of first aid, manual therapy, taping; medical follow-up when necessary.

S SEQUELAE: possible complications that can result if the original condition is left untreated, is poorly treated or if adequate medical follow-up is not pursued.

The following three charts are intended to clarify the classification and degree of injury. They outline the various aspects of treatment and put taping procedures in perspective relative to the total treatment plan. Taping alone is not a definitive treatment, but rather a protection and means to facilitate a safe, speedy recovery.

1. Watson T. Tissue healing. Electrotherapy on the web. Available online at: www.electrotherapy.org

2. Lederman E. Assisting repair with manual therapy. In: The science and practice of manual therapy. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2005:13-30.

3. Hardy M.A. The biology of scar tissue formation. Phys Ther. 1989;69:1014-1024.

4. Rarick G.L., Bigley G.K., Ralph M.R. The measurable support of the ankle joint by conventional methods of taping. J Bone Joint Surg. 1962;44A:1183-1190.

5. Fumich R.M., Ellison A.E., Guerin G.J., et al. The measured effects of taping on combined foot and ankle motion before and after exercise. Am J Sports Med. 1981;9:165-170.

6. Bunch R.P., Bednarski K., Holland D., et al. Ankle joint support: a comparison of reusable lace on brace with tapping and wrapping. Physician Sports Med. 1985;13:59-62.

7. Leanderson J., Ekstam S., Salomonsson C. Taping of the ankle – the effect on postural sway during perturbation, before and after a training session. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1996;4:53-56.

8. Taimela S., Kankaanpaa M., Luoto S. The effect of lumbar fatigue on the ability to sense a change in lumbar position. A controlled study. Spine. 1999;13:1322-1327.

9. Ivins D. Acute ankle sprain: an update. Am Fam Physician. 2006;10:1714-1720.

10. Popovic N., Gillet P. Ankle sprain. Management of recent lesions and prevention of secondary instability. Rev Med Liege. 2005;60:783-788.

11. Carter A.F., Muller R. A survey of injury knowledge and technical needs of junior Rugby Union coaches in Townsville (North Queensland). J Sci Med Sport. 2008;11:167-173.

12. Palmer T., Toombs J.D. Managing joint pain in primary care. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17(suppl):S32-42.

13. Perryman J.R., Hershman E.B. The acute management of soft tissue injuries of the knee. Orthop Clin North Am. 2002;33:575-585.

14. Bleakley C.M., McDonough S.M., MacAuley D.C., et al. Cryotherapy for acute ankle sprains: a randomized controlled study of two different icing protocols. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:700-705.

15. MacAuley D., Best T. Reducing risk of injury due to exercise. BMJ. 2002;31:451-452.

16. Worell T.W. Factors associated with hamstring injuries. An approach to treatment and preventative measures. Sports Med. 1994;17:338-345.

17. Hubbard T.J., Denegar C.R. Does cryotherapy improve outcomes with soft tissue injuries? J Athl Train. 2004;39:278-279.

18. Petersen J., Holmich P. Evidence based prevention of hamstring injuries in sport. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:319-323.

19. MacAuley D. Do textbooks agree on their advice on ice? Clin J Sports Med. 2001;11:67-72.

20. Bleakley C., McDonough S., Macauley D. The use of ice in the treatment of acute soft tissue injury: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:251-261.

21. MacAuley D.C. Ice therapy: how good is the evidence? Int J Sports Med. 2001;22:379-384.

22. Watts B.L., Armstrong B. A randomised controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of double tubigrip in grade 1 and 2 (mild to moderate) ankle sprains. Emerg Med J. 2001;18:46-50.

23. Kerkhoffs G.M., Struijs P.A., Marti R.K., et al. Different functional treatment strategies for acute lateral ankle ligament injuries in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2002. CD002938

24. Bullock-Saxton J.E., Janda V., Bullock M.I. The influence of ankle sprain injury on muscle activation during hip extension. Int J Sports Med. 1994;15:330-334.

NOTE:

NOTE: