10 Wound care

Introduction

Of all the body’s organs none is more exposed to infection, disease and injury than the skin, and wound healing is a prime example of how the body can maintain homoeostasis. This process often needs assistance to prevent the formation of chronic and sometimes fatal wounds. In this chapter we explore evidence to show how efficient aromatherapy and natural base products can be when used in the process of wound healing. The chapter also covers the stages of wound healing, previous research, the pros and cons of aromatic wound healing, pressure sores, burns and positive case studies.

The stages of wound healing

Wounds can be healed by primary intention, when the edges are brought together by stitches, staples or adhesive tape, e.g. following surgery or repaired lacerations; or by secondary intention, where the wound is left open and allowed to granulate. Very occasionally, owing to infection, wounds that are meant to heal by primary intention can break down and end up healing by secondary intention.

The classic model of wound healing is divided into several overlapping stages which normally progress in a predictable manner. If they do not, healing may not progress well, leading to a chronic wound. A good understanding of these stages is helpful in being able to provide effective aromatic treatment of wounds.

Inflammatory phase

Following injury a plug is formed to prevent further bleeding and becomes the main support for the wound until it is replaced with granulatory tissue and then collagen. Inflammation at the wound site causes an increase in circulation, resulting in tissue swelling and the release of factors involved in the next (proliferative) stage.

Inflammation facilitates the entry of white cells into the wound site, clearing it of debris and bacteria, the damaged tissue being removed after a couple of days. This debridement or cleaning of the wound

Case study 10.1 Penetrating wound with infection risk

Assessment

Marcel (49) had just sustained a penetrating, ragged wound, approximately 3.5 cm deep, 1.5 cm to the left of the anal margin, after accidentally sitting on a blunt-ended rusty metal spike while gardening.

Intervention

First-aid intervention involved bathing and flushing the wound copiously with approximately 5 drops each of Lavandula latifolia [spike lavender] and Melaleuca alternifolia [tea tree] added to cool water. A tetanus booster was administered, but owing to the proximity of the wound to the anus and the consequent high infection risk, a decision was made not to suture. Instead, the wound was treated with essential oils and monitored closely.

The following wound care blend was chosen for anti-inflammatory, wound healing, analgesic and antimicrobial effects, the concentration being deliberately elevated because of the nature of the wound:

25% of the essential oil mix below in Hypericum perforatum macerated oil base:

• 40% Thymus vulgaris ct. thujanol

• 30% Lavandula latifolia [spike lavender]

• 10% Matricaria recutita [German chamomile]

The wound was irrigated daily (using a small syringe) with the above for 1 week, to ensure rapid healing of the deeper tissues and to prevent pockets of infection forming, which might occur if epithelialization took place too swiftly. A gauze pad was soaked in the same mixture to form a compress over the wound, being changed twice daily. The same blend was used also to lubricate the anus prior to a bowel movement (to avoid over-stretching and straining), followed by careful washing of the area afterwards. A high-fibre diet and increased fluids were taken to reduce the risk of constipation.

One week after the injury irrigation was no longer required as the wound was closed and looking healthy. Two formulations were prepared for ongoing treatment until the new skin over the wound was fully stable.

Daytime use: the same blend of oils but at a concentration of 5% in Aloe vera gel. This was easy to apply during the day.

Night-time application: the same blend of essential oils in Hypericum perforatum at a 10% concentration.

Outcome

The immediate and lasting analgesic/local anaesthetic effect permitted Marcel to sit from the first day without discomfort. The speed of healing was equally remarkable, the wound diameter reducing by half in 3 days. There was also very little inflammation. On the first day the area was swollen and had a purplish appearance, and by day 2 it looked pink and healthy. At no point was there evidence of infection.

Two weeks after injury Marcel no longer needed aromatic intervention. All that remains is a small white scar that bears witness to a potentially serious penetrating wound of high infection risk.

(Taken from the International Journal of Clinical Aromatherapy 3 (2b): 14–15)

stimulates the cells that create granulation tissue and inflammation plays an important role during the initial stages; while there is debris in the wound (dirt or other objects) the inflammatory stage can become extended, leading to a chronic wound.

Proliferative (reconstructive) phase

After 2 or 3 days new blood vessels are formed within the wound. Special fibroblast cells grow, forming a new extracellular matrix (ECM) and granulation tissue. This activity requires oxygen and nutrients from the blood vessels, causing a typical red appearance of the tissue which is essential for further stages of healing to occur. The granulation tissue functions as rudimentary tissue, continuing to grow until the wound bed is covered. At the end of granulation, fibroblasts begin converting granulating tissue into collagen – important because it increases the strength of the wound. Too little oxygen will inhibit the growth of fibroblasts and the deposition of ECM, which can lead to excessive, fibrotic scarring. Thus the therapist needs to be aware that smokers and people with poor circulation can have reduced oxygen flow to the wound site, which may slow the healing process.

Epithelialization

Once the wound is filled with granulation tissue, epithelial (skin) cells begin to advance across the wound until they meet in the middle. Epithelial cells only occur at the wound edges and require healthy tissue to migrate across, so if the wound is deep it must first be filled with granulation tissue. If this new membrane becomes damaged, re-epithelialization has to occur again from the wound margins. Therefore care must be taken during dressing changes not to destroy any part of the wound membrane; the more quickly migration of skin cells occurs, the less obvious the scar will be.

Contraction

Contraction can last for several weeks and is a key stage of wound healing; if it continues too long, disfigurement and loss of function can occur. Special cells, similar to smooth muscle cells, pull the extracellular matrix within the body of the wound when they contract, reducing the wound size, whilst fibroblasts lay down the collagen to reinforce the wound.

Maturation and remodelling phase

This can last a year or longer, depending on the size of the wound and how it was left to heal. During maturation, type III collagen is replaced by type I collagen and slowly the strength of the wound increases.

Unfortunately, the process of wound healing is complex and fragile and many factors can interrupt its progress, leading to the formation of chronic non-healing wounds (see Box 10.1).

Box 10.1 Factors inhibiting wound healing

• Pre-existing disease, e.g. diabetes, cancer, venous or arterial disease, AIDS

• Certain medications that cause immune suppression, e.g. cortisone

• Location of wound, e.g. areas of pressure, friction, in flexures etc.

(adapted from Harris 2006)

The presence of a slow-healing wound has significant physical, psychological, psychosocial and financial impact. The psychosocial impact is even greater if the wound is malodorous or on a visible part of the body. The longer a wound takes to heal, the greater the microbial load, with further risk of complications and delayed healing (Bowler et al. 2001). Thus the challenge is to find interventions that promote and accelerate normal wound healing without complications, as outlined in Box 10.1.

The role of essential oils

The choice and specification of dressing is very important to achieve the above objectives and wound healing agents should adhere to certain specifications (Leach 2008). Natural bases and essential oils can play numerous roles in promoting wound healing, providing a range of treatment options (Box 10.2).

Box 10.2 The roles of essential oils in wound healing

• Prevent and treat microbial contamination

• Debride the wound of slough and necrotic tissue

• Facilitate granulation and collagen formation

• Facilitate angiogenesis and tissue perfusion

(adapted from Harris 2006)

Few dressings satisfy all the criteria in Box 10.2, but it could be said that many plant extracts come close to being ideal wound-healing agents, e.g. aloe, calendula, hypericum and comfrey (Leach 2004), which leads to the question why are natural remedies, including aromatherapy, not used more widely in hospitals, hospices and the community? In 2002, John Kerr listed the following reasons:

• the current medical system is seen as effective, despite its shortcomings

• limited anecdotal evidence, although there has been more in recent years

• a reluctance by aromatherapists to innovate

• administrative problems (e.g. patient liability issues, insurance, medical codes of ethics etc.)

• lack of education due to intensive use of essential oils not being taught by the majority of aromatherapy schools.

Famous pioneer aromatherapists such as Gattefosse and Valnet were well aware of the healing effects of essential oils, but the first report in the aromatherapy literature of using essential oils for wound healing in hospital was by clinical aromatologist Alan Barker (1994). He explored the aromatic treatment of pressure sores based on his experience of working in the English National Health Service, suggesting the following:

• application of undiluted essential oils in the presence of large amounts of pus and the need for debridement

• use of diluted oils in either honey or macerated vegetable oils

• use of sprays of distilled water with added essential oils.

NB Now that hydrolats are available, these would be preferable to water with essential oils.

Later, Ron Guba (1998/1999) used 10% of CO2 extracts and essential oils in a cream containing a range of fixed oils on a number of wound types (venous ulcers, pressure sores, skin tears and abrasions) in nursing homes in Australia. The essential oils used were Lavandula angustifolia [lavender], Artemisia vulgaris [mugwort] and Salvia officinalis [sage], plus CO2 extracts of Matricaria recutita [German chamomile] and Calendula officinalis [calendula]. The most significant results were obtained with chronic wounds.

Kerr (2002) reported the results of three years’ work using essential oils for a range of wounds in Australian nursing homes. The main finding was that a 9–12% concentration of essential oils yielded better results than much weaker doses, with no side effects. The essential oils used included Lavandula angustifolia, Matricaria recutita [German chamomile], Pogostemon patchouli, Commiphora myrrha [myrrh] and Melaleuca alternifolia [tea tree] in Aloe vera gel.

Two American practitioners (Hartman & Coetzee 2002) conducted a study using Lavandula angustifolia and Matricaria recutita essential oils diluted in grapeseed fixed oil for the treatment of chronic ulcers of several months’ duration and resistant to conventional treatments (the experimental group), comparing them with a control group who continued to receive conventional wound care. The results confirmed improved healing times in the experimental group. An important observation was that all wounds in the experimental group appeared to worsen initially for up to 2 weeks, with increased exudate and erythema, after which they showed signs of healing. A possible reason for this may be the increase in circulation and vascular permeability encouraged by the essential oil application – thereby accelerating angiogenesis. This observation has been confirmed in the author’s own practice.

Primmer (2002) successfully treated a skin tear in an elderly patient using a mix of Lavandula angustifolia, Eucalyptus radiata [narrow-leaved peppermint], Matricaria recutita and Boswellia carteri [frankincense] at 3% dilution in sweet almond oil. When applied to the wound twice daily, a significant improvement was seen within 24 hours and the wound healed totally in 4 weeks with very little scarring, the therapist using this blend successfully several times with other patients.

Diane Ames (a family nurse practitioner and clinical aromatherapist) is endeavouring to integrate the use of essential oils into the healthcare system in Milwaukee. The cases dealt with were numerous – deep-seated infections, boils and abscesses, venous ulcers, several grades of pressure sore and fungating tumours, and all had good results (Ames 2006).

The author has found the following oils to be successful:

• Melaleuca alternifolia [tea tree] both neat and diluted for infected wounds, including those with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

• Matricaria recutita and Lavandula angustifolia 50/50 at 10% dilution in macerated calendula oil for deep pressure sores.

In 2004, a team from Manchester Metropolitan University developed a dressing model for wounds to decolonize them from MRSA by vapour contact. This led to a phase 1 clinical trial on the effects of diffusion of essential oils to reduce infection risks. The study was carried out in the Burns Unit of Wythenshawe Hospital (Edwards-Jones et al. 2004) (see also Case 9.2 MRSA).

Commonly used essential oils in wound healing

Concentrations of essential oil for wound healing formulas range from 1.5% to 25%, depending on each individual case and the expertise of the therapist. Always take an in-depth history and do a patch test. For direct application essential oils should be diluted in a suitable base or used on a dressing pad rather than straight on the wound.

With regard to the use of essential oils in wound healing, several are constantly mentioned in the research literature. What has not been properly researched is whether particular constituents are responsible for specific healing results – hence the use of the word ‘may’ when discussing this in the text.

Commiphora myrrha [myrrh]

Many aromatherapy texts cite myrrh as an effective wound healer from ancient times to the present (Price & Price 1999, Battaglia 1997, Kerr 2002), being specifically healing to bedsores, as it is highly antibacterial. It has an ability to increase the number of leukocytes in the blood (Bartram 1995) and is especially bacteriostatic against Staphylococcus aureus (one of the biggest bacterial wound invaders) and other Gram-positive bacteria (Price & Price 1999). The main constituents are sesquiterpenes, which may help decongest the wound and reduce inflammation (Price 1995). Myrrh can be bought as a resin but this should not be used for wounds – only distilled essential oil is safe for this purpose.

Abies balsamea [Canadian balsam/ balsam fir]

Canadian balsam is antiseptic against staphylococcus spp. and E. coli (Price & Price 2007), anti-inflammatory and cicatrizant, and is used by Native Americans for the treatment of burns, sores and cuts. It is high in monoterpenes (75–90%, mostly β-pinene), which may be why it is good for healing skin lesions and ulcerations. It is helpful for depression, nervous tension and stress-related conditions, all of which add healing properties on a different level. Non-toxic and non-irritating, it may be chosen instead of myrrh for its ease of use, being a much thinner solution (Fact sheet, Penny Price Aromatherapy (2010).

Citrus limon [lemon]

Lemon has been found to be the most effective oil for debriding and desloughing wounds (Penny Price 2003 personal communication). This may be due to the high monoterpene content (90–95%), which can be aggressive to skin and mucous surfaces (Price L 2003 personal communication). It has exceptional antibacterial qualities, having the ability to stimulate the body’s own white blood cells (Battaglia 1997). Lemon is useful in reducing wound odours and is both mentally and spiritually uplifting.

Lavandula angustifolia [lavender]

Lavender is highly cicatrizant, being an effective cell regenerator, which may be due to its high ester content (40–55%). It is especially good for all types of burn as well as skin problems and wounds (Price & Price 2007), providing also strong bactericidal and decongestant properties.

Melaleuca alternifolia [tea tree]

Tea tree is a proven antibacterial agent, active against a wide range of bacteria and fungi, including Staphylococcus aureus (Price & Price 2007), which makes it invaluable when treating infected wounds. Its high alcohol content (28–57%) may be responsible for its first-class desloughing and cleansing properties. Interestingly, Kerr (2002) mentions the possibility of Backhousia citriodora [lemon myrtle] being more antibacterial than tea tree.

Matricaria recutita [German chamomile]

German chamomile is invaluable in wound healing because of its excellent anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and cicatrizant properties; the content of the sesquiterpene chamazulene is sometimes as high as 35%. The high oxide content (20–55%) may make it a good bactericide – also active against MRSA; oxides are also believed to have the ability to reduce inflammation and pain (ACS 2004, Price & Price 2007). German chamomile has been used successfully by Ames (2006) on leg ulcers and pressure sores.

Helichrysum angustifolium, H. italicum [everlasting, immortelle]

Helichrysum may be hailed as liquid stitching because of its remarkable healing properties on the skin’s surface. The main constituent of helichrysum is the ester neryl acetate, which is reputed to be rejuvenating to the skin, as it is a cell regenerator with antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties (Price & Price 2007, Price L 2003 personal communication). Helichrysum has exceptional cicatrizant properties, speeding cellular growth and assisting in wound healing of all types (Guba 1997). Guba suggests that the ketones (italidiones) are responsible for this, owing to their power to regenerate and heal cutaneous tissue. Eileen Cristina (2006) successfully used helichrysum in reducing a scar following a burn and topical infection. Further, the author used helichrysum for three pressure sores to encourage final epithelial growth over the wounds, which proved positive.

Melaleuca viridiflora [niaouli]

Niaouli complements lemon in the action of initial cleansing and debridement of a wound (Price P 2003, personal communication). The synergy of its constituents helps deslough the wound, reduce bacteria, pain and inflammation and encourage cell regeneration.

Because of its antibacterial and antiseptic properties, niaouli is suitable for washing infected wounds. The high oxide content may cause worries about skin irritation.

Boswellia carteri [frankincense]

Esters are a predominant feature of this oil, including octyl acetate, which is cell regenerating (Price & Price 2007). Frankincense was used successfully on a skin tear as part of a 3% mix with lavender and German chamomile by Primmer (2002), and on a fungating tumour by Ames (2006). It is a good choice for people with wounds in a hospice setting because of its spiritual and uplifting properties (Price S 1995).

How can aromatherapy be beneficial?

According to Harris (2006), for the aromatherapist who is unable to treat a wound because of procedural protocols or resistance from medical staff, all is not lost. The impact of psychological stress and social isolation on delayed wound healing is well established (Detillon et al. 2004, Vurnek et al. 2006). Any aromatic intervention that reduces stress or provides positive social interaction can potentially speed healing times. Other interventions that improve quality of life, such as pain relief or removal of wound odours, are also extremely important and can be tackled by the aromatherapist without infringing the treatment ‘rules’.

For simple or minor wounds the aromatherapist can usually intervene early and achieve swift and effective results; the implementation of aromatic interventions in more serious and chronic wounds may be dependent on the nurse practitioner or wound care specialist.

Safety/hazards

Hazards when applying essential oil-based products to areas of broken skin are irritation, allergy and wound contamination.

Leg ulcers are particularly susceptible to allergic contact dermatitis (Capriata et al. 2006), as happened to a woman using a leg ulcer cream containing geraniol (Guerra et al. 1987). The aromatherapist needs to be conscious of risks in patients with a perfume or cosmetic allergy, and patch testing before treatment is recommended. Allergy risk also arises when essential oils oxidize, as with Melaleuca alternifolia and Lavandula angustifolia (Hausen et al. 1999, Skold et al. 2002), those most often employed in wound care.

Irritation may be caused by high concentrations of essential oils, especially those rich in phenols and aldehydes. If used inappropriately these are capable of aggravating the wound by causing significant damage and cell death.

Maudsley and Kerr (1999) examined the viability and proliferation of microbes in essential oils and three fixed oils and concluded that using these oils in wound care constitutes safe practice, provided the essential oils are stored correctly and aseptic practices are followed. As indicated previously, even at concentrations of 25% no adverse reactions were noted; this may be partly due to the aromatherapist concerned selecting the appropriate oils.

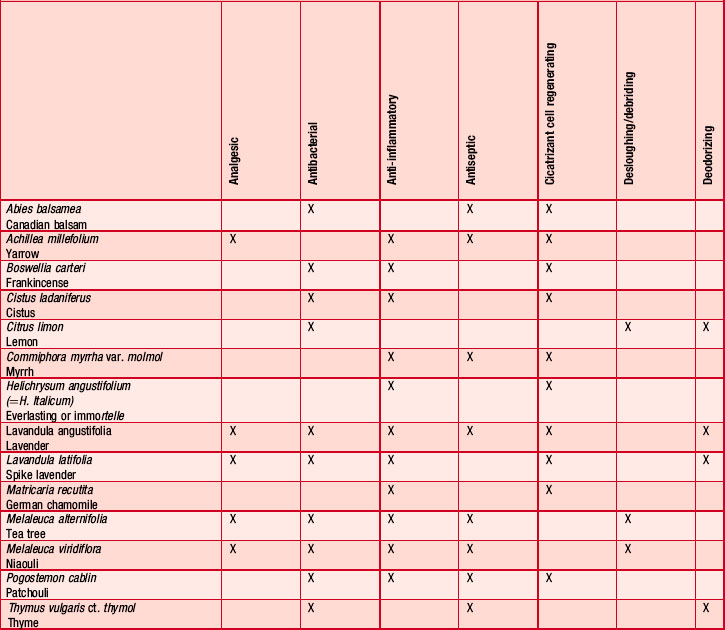

Table 10.1 list those oils most commonly used in wound care based on case reports and the author’s experience.

Natural base products

Essential oils are normally diluted in or administered in association with bases, which can bring additional wound healing. The following bases are commonly employed and have been successfully used for years by the author:

Case study 10.2 Bike accident wound

Assessment

VP, 17 years old, had been knocked off his bike by a hit-and-run driver. He managed to get home and we looked at his wounds to assess treatment. His whole right side was grazed from the ankle to the hip, with two deep cuts in the thigh where the car’s bumper had caught him. There were also abrasions to the right arm, hand and side of the face. When the blood had been cleaned away it was obvious that the amount of trauma caused was going to lead to deep bruising and possible scarring.

Intervention

It was decided that we would treat VP for four reasons:

The following treatment plan was put together:

Application

After all areas had been washed and carefully dried, lavender hydrolat was sprayed onto the body and left to dry naturally. It was reapplied three more times and left to dry in the same manner. A 5% blend was made using 50/50 of each carrier oil and an equal blend of each essential oil. This was applied to all areas and reapplied after 2 hours. After a further 2 hours the whole treatment plan was repeated, starting with the hydrolat spray, before the client went to bed.

Outcome

The following morning there was one small bruise on the right knee. The grazes and cuts had covered over and looked healthy and infection free. The skin surrounding the grazes and cuts was soft and pink. There was a little pain, but it had improved dramatically.

After 6 days of treatment the grazes had healed over and the cuts were just visible. There was no pain and VP was able to resume normal life.

• Hydrolats (although essential oils do not dissolve in hydrolats, they are useful for administering them).

Fixed oils

Fixed oils have a role to play in assisting uncomplicated wounds to heal. Those indicated for wound repair include Oenethera biennis [evening primrose], Borago officinalis [borage], Rosa rubiginosa, [rosehip seed], Calophyllum inophyllum [tamanu] and Azadirachta indica [neem].

These fixed oils can produce an anti-inflammatory effect when applied topically, as they are rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). These are crucial to cellular repair mechanisms, and so oral doses are also indicated.

Evening primrose and borage are high in PUFAs and borage has been studied for its beneficial wound healing effects (Marchini et al. 1998).

Neem oil has both traditional and research evidence (Biswas et al. 2002). It is antimicrobial, although its powerful odour may be offputting to some.

Rosehip seed’s properties for skin regeneration are due to the presence of small amounts of trans-retinoic acid (Price & Price 2008).

Tamanu is traditionally used for promoting cellular regeneration (Guba 1997) because of its confirmed cicatrizant, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, analgesic and antimicrobial properties (Kilham 2004). In the experience of Harris (2006), its analgesic activity is particularly useful for painful wounds and other lesions, such as blistering in shingles/zoster.

Macerated oils

The most popular macerated oils used in skin and wound care are Calendula officinalis [calendula] and Hypericum perforatum [St John’s wort].

Calendula has been well documented for its anti-inflammatory and wound healing activity (Zitterl-Eglseer et al. 1997), with evidence indicating it as being the most favourable wound healing extract (Leach 2008). Calendula flowers demonstrate strong anti-inflammatory and antioedematous properties, research proving it to be as effective in reducing dermal inflammation as indomethacin (a potent non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug) (Guba 1997). Used alone, calendula may facilitate wound healing by improving both local circulation and granulation tissue formation (Leach 2008), as proved by the author, who has used it alone to protect and strengthen the skin during the initial stages after healing. Its properties are enhanced when mixed with wound-healing essential oils (Price & Price 2008). Topical applications of calendula are safe, and it has been approved by the German Health Commission for topical administration in oral and pharyngeal mucosal inflammation, poorly healing wounds and leg ulceration (Leach 2008). It is advised that individuals with a known sensitivity to other species of the Asteraceae family, e.g. chrysanthemum, daisy etc., avoid calendula because of the potential risk of allergic reaction.

Hypericum perforatum is beneficial on wounds where there is nerve tissue damage and inflammation, including sunburn (Price & Price 2008), thought to be mainly due to the hypericin (a flavonoid) content, and has been approved for the treatment of first-degree burns (Blumenthal et al. 2000). The leaf extract has also been used for its wound healing potential (Mukherjee et al. 2000), partly due owing to the flavonoid content. Price and Price (2008) point out that the properties of St John’s wort may vary according to harvest and that the flavonoids and proanthocyanidins useful in wound healing are highest when the flowers are in bud.

NB Homemade macerated oils carry the risk of contamination with fungal and bacterial spores. Both fixed and macerated oils should always be obtained from a reliable source, as they are normally microfiltered and often sterilized.

Hydrolats

According to Harris (2006) hydrolats and aqueous plant extracts are useful for wound care and may be applied:

• directly to the wound during cleaning

• in irrigation if the wound is deep

Hydrolats are cooling to the skin and help maintain wound moisture. They have a range of possible activities, e.g. pain relief and anti-inflammatory, depending on the species (see Box 10.3). They are active agents used alone or in combination with essential oils (up to 10%): it may be advisable to use an emulsifying/surfactant agent such as Tweens to permit even distribution of the essential oil, although this may perhaps reduce their antimicrobial activity (Lund 1994).

Box 10.3 Benefits of hydrolats in wound care (Harris 2006)

NB Depending on the hydrolat, regular handling and the passage of time may present a risk of microbial contamination, especially with microbes such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa. If hydrolats are to be used in wound care they should first be tested to ensure they contain no more than the permissible microbial load. Sterile preparations of hydrolats in unidose packaging are now becoming available in Europe.

Honey

A variety of wound types have been studied using honey; it has been demonstrated (Molan 2006) to be beneficial in dressing models and would be enhanced by the addition of essential oils. The beneficial effects of honey include:

• reduction of inflammation and hence swelling, exudate and pain

• induction of sloughing of necrotic tissue

• easy removal of sloughs without trauma

Essential oils can be added to honey to further enhance healing, the amount added being judged according to the particular situation.

According to Molan (2006) and Winter (1962), wounds heal 50% faster if kept moist, although fear of increased bacterial growth sometimes causes clinicians to try keeping wounds dry. Honey prevents the growth of bacteria in a moist healing environment, which allows rapid removal of pus, dead tissue and debris, thereby speeding up tissue growth to repair the wound (Molan 2006). Honey also reduces inflammation, preventing blood vessels opening up and thereby reducing exudate and swelling.

The anti-inflammatory action reduces pain, with the added benefit of a reduction in the amount of blisters and scarring due to the mopping-up of free radicals at the time of occurrence (Subrahmanyam 1991, Subrahmanyam et al. 2003). Honey has a nutrient effect and draws out lymph from the cells by osmosis; this creates a honey solution in contact with the wound surface which prevents the dressing from sticking (Molan 1998).

The antibacterial property of honey helps avoid infection, which prevents wound healing, and the debriding action is important as it removes substances that harbour bacteria, stopping the healing and causing malodour.

NB When too much exudate is present the action of honey may be diluted.

Clay

The most commonly used clay is bentonite. Although there is little scientific evidence for its healing benefits (absorptive and adsorptive qualities), it is particularly suited for deep wounds with exudate and necrotic tissue, is extremely soothing and accelerates healing times. It also has deodorizing ability.

There are three main methods of using clay in wound care:

NB Clay should be obtained from reputable sources – contaminated clay risks wound infection. Powdered clay should be prepared with the addition of hydrolat or distilled water just before each use; if ‘ready to use’ clay is to be employed, this needs to be in a sterilized form.

Aloe vera

Aloe vera is anti-inflammatory (Vazquez et al. 1996, Gallagher & Gray 2003) and is traditionally used on wounds and burns and other skin disorders, e.g. psoriasis (Akhtar & Hatwar 1996, Syed et al. 1997, Reynolds & Dweck 1999) and appears to work best in superficial and uncomplicated wound care. Its advantage when used with essential oils is linked to its hydrophilic qualities, allowing the transfer of essential oil onto the tissues. It is rarely possible to incorporate more than 5% essential oil into aloe gel without separation unless a surfactant is used.

NB Delayed healing may be experienced in infected wounds or those healing by secondary intention (Schmidt & Greenspoon 1991). Few sterile Aloe vera preparations exist, which poses a risk of microbial contamination, those available showing a degree of inconsistency (Reynolds & Dweck 1999), with some containing ingredients that could cause contact dermatitis (Reider et al. 2005).

Pressure sores (decubitus ulcers)

Traditional medicine has limited success here, but nurses have found essential oils to effect healing (Price & Price 2007). Pressure sores occur mainly over bony prominences and are areas of inflamed or even necrotic (dead) tissue. They develop as a result of sustained localized pressure which compresses blood vessels in the area, causing ischaemia to the skin and underlying tissues. Pressure sores generally happen in people with reduced neurological integrity and mobility, other contributing factors including reduced padding of fat and muscle, anaemia, poor nutritional status, incontinence and infection. Extrinsic factors include pressure, shearing forces, trauma, moisture and friction. Possible complications include infection in the blood, heart and bone, amputations and prolonged bed rest – which brings its own complications, including death.

The severity of a pressure sore is graded according to the depth of ulceration and involvement of underlying tissues, which also helps determine the required treatment (see Table 10.2).

Table 10.2 The pressure sore grading system (based on EPUAP 2010)

| Grade 1 Non-blanchable erythema |

Discoloration of intact skin not affected by light finger pressure (non-blanching erythema). This may be difficult to identify in darkly pigmented skin, where it is likely to appear red, blue or purple |

| Grade 2 Partial-thickness skin loss |

Partial-thickness skin loss or damage involving epidermis and/or dermis. The pressure ulcer is superficial and presents clinically as an abrasion, blisteror shallow crater |

| Grade 3 Full-thickness skin loss |

Full-thickness skin loss involving damage to subcutaneous tissue but not extending to underlying fascia. The pressure ulcer presents clinically as a deep crater with or without undermining of adjacent tissue |

| Grade 4 Full-thickness tissue loss |

Full-thickness tissue loss with extensive destruction and necrosis extending to underlying tissue or supporting structures (muscle, bone and/or tendon) |

First, dead or sloughy tissue needs to be removed before healing can take place, which sometimes requires surgery. If infection is present antibiotics may be required, therefore collaboration with the patient’s healthcare team may be necessary, depending on the severity of the situation.

Burns

Essential oils were used with success on severe burns in University College Hospital in 1988; a consultant tried the effectiveness of essential oils, saying ‘what I have been offered has been researched – but does nothing; what you have given me has not been researched – yet it works. This is what interests me’ (Parkhouse 1988 personal communication). Most critical care units would not allow this use without research evidence, of which there is still not much. The cicatrizant properties of certain essential oils are very powerful, especially when used with macerated oil of Hypericum perforatum [St John’s wort], which is used for treatment of injuries and first-degree burns (Blumenthal et al 2000):

Case study 10.3 Two clients with pressure sores

Assessment

Lucy (48) is paraplegic from C5 and presented with a pressure sore 4 cm in diameter over her left shoulder blade, due to friction from her wheelchair. The sore contained sloughy tissue and the intact skin around it was red and inflamed from constant dressing changes. There was no evidence of infection in the wound.

Bill (52) has multiple sclerosis and had developed a large pressure sore over his sacrum due to a recent relapse. This measured 6.5 cm across by 3.5 cm and was 2 cm deep, with the presence of a substantial layer of infected necrotic tissue within the wound. Initially this pressure sore was ungradable. The skin around the sore was very red and purple, with several abrasions over the buttocks.

Intervention

All pressure was removed from the sores, Bill having to stay on bed rest on a special air mattress for the duration of healing. It was more difficult to remove the pressure from Lucy’s sore at the back of her wheelchair.

Bill’s large pressure sore was initially debrided using manuka honey inserted into the wound, which was then packed with sterile gauze soaked in the honey. The wound was then covered with gauze pads to absorb any excess moisture and changed twice daily to maintain efficacy of the honey, and he started taking antibiotics to combat the infection. After 13 days the sore was fully debrided but was now 4 cm deep. Luckily this was still only a grade 3 pressure sore because no underlying bone, muscle or tendons were involved. The wound was now oozing an excessive amount of exudate, which rendered the honey ineffective despite more frequent dressing changes. Therefore, the treatment regimen was changed to the same as used for Lucy:

Stage 1 wound healing formula, 10% dilution

To debride and clean the sores of slough, encourage perfusion, prevent infection and commence granulation. All the wounds were cleaned with sterile sodium chloride 0.9% (normal saline solution), packed with gauze soaked in this formula and covered with a secondary gauze dressing. The dressings were changed twice daily.

• 30 mL Calendula officinalis [calendula]

• 10 drops Commiphora myrhha [myrrh]

For the surrounding inflamed skin of both Lucy and Bill, a formulation of 1.5% dilution of myrrh in calendula was applied regularly throughout the day.

Stage 2 formula, still at.10% dilution

Once the slough was removed and the wounds were clean and pink, the wound formula was changed to:

Stage 3 formula, 7.5% dilution

As the wounds filled with granulating tissue and became more shallow, the dilutions were reduced and the myrrh was further increased in relation to the lemon and niaouli. Helichrysum was added to help the final stages of healing, because of its exceptional efficacy at the skin’s surface. At one stage the shallower sores started to dry out, which caused some minor bleeding of the new tissue on removal of the dressings. Therefore, non-adherent dressings were applied over the packed wounds, which made all the difference. In the final stages the formula was placed on the dressing pad and applied over the wound:

Outcome

Lucy’s sore healed in 40 days (despite some continued pressure from the wheelchair). Bill’s large sore healed in 63 days. The surrounding skin of both Lucy and Bill improved, becoming pink and normal within a short space of time. Apart from Bill’s initial infection, at no other time were there signs of infection in either of the wounds. Bill’s case was a challenge because of the close proximity of his sore to the anal area.

• Boswellia carteri [frankincense] – scars, wounds

• Helichrysum italicum [everlasting] – burns, open wounds, scars, skin regeneration

To keep the air antiseptic in a burns ward the following can be vaporised:

Pinus sylvestris [pine]

Other burns units that incorporate aromatherapy are the children’s burns unit in the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital in South Africa.

Radiation burns

Melaleuca viridiflora [niaouli] can be used to lessen radiation burns in those receiving this treatment for cancer (see Ch. 15).

Summary

This chapter shows that there is much evidence to support the use of aromatic extracts and related bases in wound healing, wound management objectives generally being achieved. Even so, their use in hospices and hospitals, plus feedback from the author’s clients, is usually a final option when orthodox methods have failed, resulting in an extremely poor wound healing prognosis. As a result, some of the research regarding the use of essential oils involves the added difficulty that the wounds have not previously responded to conventional treatment and are usually chronic. Despite this, the majority of results are positive, emphasizing the efficacy of aromatic wound healing.

Depending on the health authority involved, one issue appears to be the cost and availability of manpower: many pharmaceutical dressings only need reapplying once a day or less, as opposed to the possibility of more frequent changes for aromatic dressings – depending on the type of wound. This leads to increased costs in more home visits by nurses to change the dressing. In terms of long-term cost-effectiveness, essential oil interventions prove much cheaper than typical dressing models and generally do not need more frequent application – in fact, because they are effective and cheap, there is every reason why they should be used.

Further support for the use of essential oils, hydrolats and related bases is the issue of infection. MRSA is one of the biggest problems in hospitals today, especially for the weak and elderly. Most essential oils used in wound healing are active against this superbug – and many other bacteria. Research shows that wounds treated with aromatics rarely become infected, resulting in more rapid healing and less need for antibiotics.

With the advent of postgraduate training in aromatherapy and the possibility of taking a diploma in aromatic medicine/aromatology (see Useful addresses), it appears that the necessary change is slowly taking place. More research is being carried out to support the use of plant extracts (including essential oils) in the healing of wounds, although to be accepted by the medical and nursing profession it must be more than anecdotal: rigorous clinical trials are needed to establish confidence and a turnaround in professional opinion.

ACS (American Chemical Society). Molecule of the week. http://www.chemistry.org/portal/a/c/s/1/acsdisplay.html, 2004.

Akhtar A.M., Hatwar S.K. Efficacy of Aloe vera extract cream in management of burn wound. J. Clin. Epidemiol.. 1996;49(1 Suppl. 1):24S.

Ames D. Aromatic wound care in a health care system: a report from the United States. International Journal of Clinical Aromatherapy. 2006;3(2):3-8.

Barker A. Aromatherapy and Pressure Sores. Aromatherapy Quarterly. 1994;41:5-7.

Bartram T. Encyclopedia of herbal medicine. Christchurch: Grace; 1995:304.

Battaglia S. The Complete Guide to Aromatherapy, second print. Australia: The Perfect Potion; 1997.

Biswas K., Chattopadhyay I., Banerjee R.K., Bandyopadhyay U. Biological Activities and Medicinal Properties of Neem (Azadirachta indica). Curr. Sci.. 2002;82(11):1336-1345.

Blumenthal M., et al. Herbal Medicine. Expanded Commission E Monographs. Newton, MA: Integrative Medicine Communications; 2000.

Bowler P.G., Duerden B.I., Armstrong D.G. Wound Microbiology and Associated Approaches to Wound Management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.. 2001;14(2):244-269.

Capriata S., Legori A., Motolese A. Contact sensitivity in patients with leg ulcers. Annali Italiani di Derm. Aller. Clin. Esp.. 2006;60(1):15-21.

Cristina E.D. Scar reduction following burn and tropical infection: a case study. International Journal of Clinical Aromatherapy. 2006;3(2):19-20.

Detillon C.E., Craft T.K.S., Glasper E.R., Prendergast B.J., DeVries A.C. Social facilitation of wound healing. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(8):1004-1011.

Edwards-Jones V., Buck R., Shawcross S.G., Dawson M.M., Dunn K. The effect of essential oils on Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus using a dressing model. Burns. 2004;30:772-777.

EPUAP (European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel). International Pressure Ulcer Guidelines. http: //www.epuap.org/guidelines.html, 2010.

Gallagher J., Gray M. Is Aloe vera effective for healing wounds? J. Wound Ostomy Continence Service. 2003;30:68-71.

Guba R. Aromatic Extracts as Wound Healing Agents (Part 1). Aromatherapy Today. 1997;3:21-25.

Guba R. Wound healing. International Journal of Aromatherapy. 1998;9(2):67-74.

Guerra P., Aguilar A., Urbina F., Cristobal M.C., Garcia-Perez A. Contact dermatitis to geraniol in a leg ulcer. Contact Dermatitis. 1987;16(5):298-299.

Harris R. Aromatic approaches to wound care. International Journal of Clinical Aromatherapy. 2006;3(2b):9-18.

Hartman D., Coetzee J.C. Two US Practitioners experiences of using essential oils in wound care. J. Wound Care. 2002;11(8):317-320.

Hausen B.M., Reichling J., Harkenthal M. Degradation products of monoterpenes are the sensitizing agents in tea tree oil. Am. J. Contact Dermat.. 1999;10(2):68-77.

Kerr J. Research Project – using Essential Oils in Wound Care for the Elderly. Aromatherapy Today. 2002;23:14-17.

Kerr J. Using Essential Oils in Wound Care. In Essence. 2003;1(4):13-17.

Kilham C. Tamanu Oil (Calophyllum inophyllum) A Tropical Treatment Remedy. http//medicinehunter.com/tamanu1.htm, 2004.

Leach M.J. A critical review of natural therapies in wound management. Ostomy Wound Manage.. 2004;50(2):36-46.

Leach M.J. Calendula Officinalis and Wound Healing: A Systematic Review. Wounds. 2008;20;(8). Research.com.

Lund W. Principles and Practice of Pharmaceutics. The pharmaceutical codex. twelvth ed. London: The Pharmaceutical Press; 1994.

Marchini F.B., Martins D.M., de Teves D.C., Simoes M de J. Effect of Rosa Rubiginosa Oil on the Healing of Open Wounds (in Portuguese). Rev. Paul. Med.. 1998;106(6):356.

Maudsley F., Kerr K.G. Microbial safety of essential oils used in complimentary therapies and the activity of these compounds against bacterial and fungal pathogens. Support Care Cancer. 1999;7:100-102.

Molan P.C. A brief review of the use of honey as a clinical dressing. Primary Intention. The Australian Journal of Wound Management. 1998;6(4):148-158.

Molan P.C. Using honey in wound care. International Journal of Clinical Aromatherapy. 2006;3(2b):21-24.

Mukherjee P.K., Verpoorte R., Suresh B. Evaluation of in-vivo wound healing activity of Hypericum patulum (Family: Hypericaceae) leaf extract on different wound model in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2000;70:315-321.

Price P. Abies balsamea [Canadian balsam] Fact sheet. Penny Price Academy of Aromatherapy; 2003.

Price L., Price S. Carrier Oils for Aromatherapy and Massage, fourth ed. Stratford-upon-Avon: Riverhead; 2008.

Price S. Aromatherapy Workbook. London: Thorsons; 1995.

Price S., Price L. Aromatherapy for Health Professionals, second ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1999.

Price S., Price L. Aromatherapy for Health Professionals, third ed. Philladelphia: Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier; 2007.

Primmer J. Case study – healing a skin tear with essential oils. Aromatherapy Today. 2002;23:20-21.

Reider N., Issa A., Hawranek T., Schuster C., Aberer W., Kofler H., et al. Absence of contact sensitization to Aloe vera. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53:332-334.

Reynolds T., Dweck A.C. Aloe vera leaf gel: a review update. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 1999;68:3-37.

Schmidt J.M., Greenspoon J.S. Aloe vera dermal wound gel is associated with a delay in wound healing. J. Obstet. Gynaecol.. 1991;78:115-117.

Skold M., Borje A., Matura M., Karlberg A.T. Studies on the autoxidation and sensitizing capacity of the fragrance chemical linalool, identifying a linalool hydroperoxide. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46(5):267-272.

Subrahmanyam M. Topical application of honey in treatment of burns. Br. J. Surg.. 1991;78:497-498.

Subrahmanyam M., Shahapure A.G., Nagane N.S., Bhagwat V.R., Ganu J.V. Free radical control – the main mechanism of the action of honey in burns. Annals of Burns and Fire Disasters. 2003;16(3):135-138.

Syed T.A., Ali Ahmad S., Ahmadpour O.A. Management of psoriasis with Aloe vera extract in a hydrophilic cream – A placebo-controlled, double blind study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol.. 1997;9(Suppl. 1):S180.

Vazquez B., Avila G., Segura D., Escalante B. Anti-inflammatory activity of extracts from Aloe vera gel. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 1996;55(1):69-75.

Vurnek M., Weinman W., Whiting J.C., Tarlton J. Skin immune markers: Psychosocial determinants and the effect on wound healing. Brain Behav. Immun.. 2006;20(3 Suppl. 1):73-74.

Winter G.D. Formation of the scab and the rate of epithelialization of superficial wounds in the skin of the young domestic pig. Nature (London). 1962;193:293-294.

Zitterl-Eglseer K., et al. Anti-oedematous activities of the main triterpendiol esters of marigold (Calendula officinalis L.). J. Ethnopharmacol.. 1997;57(2):139-144.