15 Palliative and supportive care

Introduction

The approaches to palliative and supportive care are holistic; they differ in philosophy from curative strategies in that they focus primarily on the consequences of a disease rather than on its cause or specific cure – they are pragmatic and multidisciplinary, with very little distinction between palliation and support (National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services [NCHSPCS] 2000). This chapter gives an insight into palliative and supportive care, together with the use of essential oils. With the help of aromatherapy, people have enjoyed a quality of life better than they might otherwise have experienced.

Defining palliative and supportive care

Although originally written for those with cancer, the definitions of palliative and supportive care ‘…can be used for people with any life-threatening illness.’ (National Council for Palliative Care [NCPC] 2002)

Supportive care helps patients and their families to cope with cancer and its treatment – through the process of diagnosis and treatment, to continuing illness, possible cure or death and into bereavement. (NICE 2004). Where cure is not an option, care is focused on helping them through the difficult times ahead and maintaining optimum independence with the best quality of life possible. Supportive care is an integral part of palliative care.

Palliative care involves the total care of patients with advanced progressive illness which no longer responds to curative treatment. It is needed when the best quality of life for them and their families becomes the most important issue, and where the management of pain and other symptoms, and the provision of psychological, social and spiritual support, are paramount. Palliative care neither hastens nor postpones death: it merely recognizes a patient’s right to spend as much time as possible at home, and pays equal attention to physical, psychological, social and spiritual aspects of care wherever the patient is (World Health Organization [WHO] 1990).

Palliative and supportive care does not see the patient in isolation but as part of a family unit – whatever that family unit might be. Many patients die in residential care where members of staff and other residents are part of the ‘family’: indeed, they may be the only ‘family’, and therefore experience the loss themselves. Those providing day-to-day care and support to patients and carers are facing the reality of death – it is often forgotten that they too need support.

Aromatherapists could teach a simple massage technique to these people – even the patient – to give them the opportunity to give and receive caring touch. It can be a transforming experience, as so often the loved ones feel helpless in not knowing how to show they care, or are frightened of ‘doing the wrong thing’. Similarly, the patient often feels s/he is giving nothing in return for the love and care shown, and being able to participate in a simple massage can make a world of difference.

End of life care – the definition suggested by the NCPC states that: ‘….all those with advanced, progressive, incurable illness….’ should be given such care. When this final stage begins is difficult to determine as it depends on many factors, not least on individual personal and professional points of view and the nature of the condition.

Decline at the end of life (see also, below, under Common characteristics) falls broadly into three main categories, those who will:

• remain in reasonable good health until shortly before death, with a steep decline in the last few weeks or months

• decline more gradually, with episodes of acute ill health

• be very frail for months or years before death with a steady, progressive decline

(Department of Health [DOH] 2008 End of Life Care Strategy).

Palliative and supportive care requires the expertise of a multidisciplinary team whose members include doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social workers, clergy, counsellors, complementary therapists etc., but to be effective it must be tailored to the needs of patients and their families. Often both palliative and supportive care are provided by the patient’s family and other carers, and not exclusively by professionals (NICE 2004). The aromatherapist, even if treating a patient independently, is still part of the team and should recognize the importance of keeping the team informed of his/her part in the patient’s care.

The disorders involved

Until now, palliative and supportive care has been largely confined to those with cancer – at least 50% of all patients in the UK with this condition will have had such care at some time in the course of their illness (Addington-Hall 1998). However, in developed countries more people die of chronic circulatory and respiratory conditions such as chronic heart disease (CHD), stroke and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Few palliative care services have focused on their needs or those of others with non-cancerous life-limiting conditions when they near the end of their life (NICE 2003; Ahmedzai 2006; Gore et al. 2000).

The ageing population is increasing rapidly – it is estimated that by 2033 in the UK, 23% of the population will be over the age of 65 (Office of National Statistics 2009). Many, if not most, will have two or more coexisting chronic conditions that will significantly impair their quality of life. Palliative and supportive care has now broadened to include all those with life-limiting conditions, notably:

• infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

• degenerative neurological disorders such as motor neuron disease (MND), multiple sclerosis (MS) and Parkinson’s disease (PD)

• chronic circulatory conditions, including CHD and stroke

• chronic respiratory conditions, e.g. COPD

• chronic organ failure such as kidney and liver

• disorders that occur only in childhood, e.g. cystic fibrosis

• various genetic and congenital disorders, e.g. Huntington’s disease

Common characteristics

These disorders have some or all of the following characteristics in common:

• an increased likelihood of fear, psychological, social and spiritual distresses

• unpredictable symptoms, which are always changing and can be very distressing. There will be good days and bad days, which can add to the frustrations and stress of the patient, family and carers

• a lack of understanding of these disorders by some healthcare workers and by society in general, can unwittingly contribute to the person’s distress

• life-threatening, with shortened life expectancy – often quite significant, and the last phase of the illness probably being relatively short

• a ‘life’ pattern which can fluctuate quite markedly both in the individual and from person to person, e.g. there may be periods of remission, exacerbation or stability, or there may be a slow progressive decline; nevertheless, people may also appear fit and well with little or no change to their way of life

• the rate and manner of decline can fluctuate and varies considerably from person to person. The point comes when death is likely to occur in a matter of hours or days rather than weeks.

Symptoms

Below are some examples of distressing symptoms caused directly or indirectly by the disease or its treatment and commonly encountered in palliative care. Most, except possibly those marked with * can be helped or alleviated in some way by the essential oils listed alongside the individual symptoms in Appendix A II on the CD-ROM. More detailed information on the emotional aspects can be found in Aromatherapy and Your Emotions (Price 2000).

Physical examples

• Fatigue – no energy – always feeling tired/weak

• Poor appetite – loss of interest in food – nothing tastes or smells the same

• Feeling sick most/all of the time – smells, especially food/or sight/thought of food

• Vomiting* with or without nausea/with or without effort

• Sleep problems – can’t get to sleep/keep waking up

• Feeling out of breath all the time – and at rest/can’t breathe – panic attacks

• Mouth problems – dry – sore /ulcerated/infected – nasty taste

• Skin problems – dry/papery/marks or tears easily/lesions/bruising/rashes/sore/red

• Wound/stoma smells/‘I smell’

• Muscle spasms/rigidity/weakness/loss of control* – difficulty in swallowing*/dribbling of saliva*/attacks of choking*

• Loss of bladder control/constipation/diarrhoea

• reduced mobility – reduced dexterity

• Impaired sensation* – reduced/increased/altered – numbness/pins and needles

Psychosocial examples

• Shock and disbelief at the diagnosis, unable to make sense of what is happening – often described as ‘a whirlpool of emotions’

• Anger and frustration with delays in diagnosis, etc.

• Anxiety and fear of pain, the unknown, death itself, how, when and where they will die, fear of being alone when that time comes

• Tense, depressed, anxious, frightened and panicky – not able to say why

• Feeling helpless and no longer in control

• Worry about the future, how will their loved ones cope, how will it affect them

• Loss, grief, appearance, independence, different future

• Confusion, including disorientation (usually associated with brain tumours or dementia, can be due to medication)

• Withdrawing from people, not talking about their illness, keeping loved ones at a distance

• Low morale and self-esteem – ‘can’t be bothered’, ‘what’s the point’ etc.

Anxiety and panic

There is some evidence to show that aromatherapy massage can help relieve anxiety and aid relaxation (Hadfield 2001, Imanishi et al. 2007, Wilkinson et al. 2007). When patients are experiencing severe anxiety and panic there are many calming and sedative essential oils to choose from, such as Chamaemelum nobile [Roman chamomile], Canarium luzonicum (elemi) Cananga odorata [ylang ylang], Citrus aurantium var amara per. [orange bigarade] and

Assessment

Jane is married with school-aged children and worked as a cleaner. At 47 years of age a small lump was growing on her right hip. She was diagnosed with neurofibrosarcoma and received radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy.

Jane has now developed bone metastases in the hips, ribs and sternum, and is aware that her disease is incurable. She attends NHS day hospice one day per week for supportive and palliative care; she has increasing pain and tenderness over her sternum and shoulder. Sleep was poor because of the pain despite medication of fentanyl patch 25 mg, diclofenac 50 mg and morphine liquid 10 mg for breakthrough pain.

The worst pain was in her shoulder and she could not relax or sleep because of it; her mood was very low. Jane had several swellings and many small lumps in her tissues.

Intervention

Massage was out of the question, so it was decided to use an essential oil compress on the shoulder, blending essential oils of:

• Origanum majorana [sweet marjoram] – calming to the nervous system, analgesic for aching muscles

• Juniperus communis (fruct) [juniper berry] – helpful for painful joints and insomnia

• Chamaemelum nobile [Roman chamomile] – sedative, anti-inflammatory.

After 10 minutes she looked comfortable and relaxed, with no response when spoken to softly.

Outcome

Jane slept for a half hour, and on waking she felt relaxed and had less pain, telling the day hospice manager and her husband (with a smile) how much better she felt. Jane has a compress applied weekly at the day hospice and has a blended lotion containing the above oils plus Lavandula angustifolia to apply daily at home on areas of pain and to aid sleep. This intervention was simple and gave effective symptom relief.

Citrus reticulata (mandarin] (also see Appendix B.9 on the CD-ROM). The patient can be asked to choose the aroma they find the most pleasing from a small selection of single oils, and/or a blend of two or three.

Patients can be given a 10 mL bottle of the chosen oil/s blended in a carrier to use themselves on pulse points during periods of anxiety. If they feel a panic attack pending they can inhale the oils from an inhaler stick or a tissue – many patients have experienced a reduction in anxiety simply by inhaling their chosen oil. Elaine Cooper has worked closely with a clinical psychologist in oncology and palliative care where she works in an NHS palliative care team, with referrals requesting to aid relaxation and reduce anxiety with aromatherapy, and there have been some outstanding results with some patients.

Essential oils chosen most frequently are Rosa damascena [rose otto] Citrus aurantium var. amara flos [neroli], Boswellia carteri [frankincense], Lavandula angustifolia and Chamaemelum nobile [Roman chamomile].

Spirituality

Being confronted with their own mortality often makes a person turn inwards and question their innermost thoughts, beliefs and values in an attempt to make sense of what is happening. The less a person is able to do physically, the more time they have for thinking, which can lead to much anguish and torment. Aromatherapy treatment may afford help in spiritual care, bringing comfort and peace in the form of deep relaxation. Patients may then be able to focus on their own spirituality. Essential oils that would help here are those which are both uplifting and soothing, analgesic and/or tonic to the heart, relieving any fears, e.g. Boswellia carteri [frankincense], Chamaemelum nobile [Roman chamomile], Citrus bergamia [bergamot], Lavandula angustifolia [lavender], Ocimum basilicum [sweet European basil] and Origanum majorana [sweet marjoram] (Price 2000; Tisserand 1992).

For the patient and their family, social problems and issues arise from the changes and adjustments that have to be faced in their relationships and daily life, whether they are temporary or permanent.

Pain – an example of the complex nature of a symptom

According to Twycross and Lack (1984) the perception of pain is modulated by the patient’s mood and morale, the meaning of pain to the patient and the

Assessment

This patient, who took pride in her appearance, had cancer of the vulva, with local spread causing a fungating lesion in her left groin. She was very distressed by this, due to its appearance and the malodour, of which she was very conscious and tried to disguise it with perfume.

Intervention

The aromatherapist discussed the use of essential oils to disguise odour and the patient was happy for any help she could get. Oils were chosen together, selecting the aromas she liked. The aromatherapist advised the use of more than one oil to increase the efficacy through synergy. The essential oils chosen were:

• Lavandula x intermedia [lavandin] – antiseptic, deodorant, calming, cicatrizant

• Citrus aurantium var. sinensis [sweet orange] – antiseptic, calming

• Myristica fragrans [nutmeg] – deodorant, analgesic, antibacterial

• Cupressus sempervirens [cypress] – deodorant, antiseptic, antibacterial

The patient was provided with a 5 mL bottle of each and instructed to use two drops on a tissue to inhale as needed, or tuck it into her clothes near to the wound. Written instructions were also provided.

To help aid relaxation, shoulder massage was carried out in a 1% dilution in sweet almond oil with:

Outcome

The following week the patient reported that she had coped much better with the odour from her wound, had enjoyed using the oils and felt more confident when in company.

The patient enjoyed and looked forward to her massage, feeling relaxed and calm after a treatment; she felt pampered and more ‘normal’, despite suffering such a disfiguring disease.

fact that pain may remain intractable if mental and social factors are ignored.

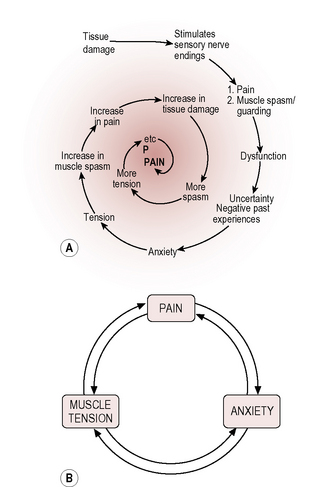

Pain is a warning of actual or potential tissue damage or pathology and creates some muscle tension (guarding) to protect the area. It elicits an arousal and an emotional response, and is modified by mental state and emotions (Marieb 1998). Most people with pain usually become anxious about the possible implications; this leads to more muscle tension, and muscle tension increases the pain that increases the emotional response, and so on, each perpetuating the other into a vicious circle that can become a spiralling process (McCaffery & Beebe 1989).

Localized pain and essential oils

Massage with analgesic essential oils brings its own benefits, but if massage is not advisable the application of essential oils in a lotion – or with a compress or spray – can also bring a reduction in pain.

Factors to be considered that might be contributing to the pain include inflammation, tension, swelling or nerve involvement etc. A significant reduction in pain may possibly be achieved by using the following.

Oils containing esters and sesquiterpenes, which are generally regarded to be anti-inflammatory, antispasmodic and calming, making them very useful for pain, include Chamaemelum nobile [Roman chamomile], Lavandula angustifolia [lavender] and Citrus aurantium var. amara (fol) [neroli].

Box 15.1 Some factors affecting pain threshold

| Threshold lowered by: | Threshold raised by: |

|---|---|

| Discomfort Insomnia Fatigue Anxiety Fear Anger Sadness Depression Boredom Introversion Mental isolation Social abandonment |

Relief of symptoms Sleep Rest Sympathy Understanding Companionship Diversional activity Reduction of anxiety Elevation of mood Analgesics Anxiolytics Antidepressants |

Pogostemon patchouli [patchouli] and Commiphora myrrha [myrrh] are also anti-inflammatory, and Lavandula angustifolia [lavender] and Zingiber officinale [ginger] are useful for their analgesic properties.

Where there is pain combined with anxiety or depression Cooper has found a blend of Boswellia carteri and Commiphora myrrha to be most helpful.

From observing, listening and talking to patients over many years, Sue Whyte believes that the principle of the pain spiral may apply to other physical symptoms the patient may experience. Similarly, their general outlook on life will contribute to their mood and confidence; the coping strategies they use – and their personality – do not usually change because they are ill, although they may subsequently do so. The effects of the close, subtle interplay between the physical, psychological, social and spiritual aspects should never be underestimated. Any negative factors in the person’s life will lower their tolerance level to symptoms, whereas positive ones will raise it. Most people, when in low spirits, find that everything seems to be worse; likewise, when feeling full of the joys of spring, they can cope with anything. Illness is no different. However, even the most cheerful and positive of people can be knocked off balance and succumb to physical symptoms that nothing seems to ease. For example, feeling sick all the time – made worse by the sight, smell and sometimes even just the thought of certain things – can be a major problem for some patients, making them more anxious and distressed.

In Chapter 8, Price discusses the effects that essential oils have on the emotions, which may or may not be a placebo response: according to Tisserand, if a smell is appealing, it soothes the mind (Tisserand 1992 p. 99). Placebo or not, if the experience of aromatherapy is pleasant and relaxing, even for a short time, it will surely have some beneficial effect on the patient’s mood and morale long enough to interrupt the vicious circle, thus helping them relax (Hadfield 2001), enhancing factors that raise a person’s tolerance level to their situation. This has a dual effect:

• it enables the patient to cope more effectively with their illness and day to day problems

• by reducing stress alone, pressure on the immune system is lessened (Alexander 2001, Fujiwara et al. 2002, Kuriyama et al. 2005).

Evidence from various studies discussed and cited by Tavares (2003) is encouraging, as it supports much of the anecdotal evidence given in many books and articles regarding the positive effect aromatherapy and massage can have on symptoms and quality of life (Bowers 2006, Corner et al. 1995; Downer et al. 1994; Gatti & Cajola 1923; Grealish et al. 2000; Lee & Lee 1992; Pan et al. 2000; Wilkinson et al. 1999; Wilkinson S. et al. 2006).

Aromatherapy intervention

Cancer, HIV/AIDS, MND etc. are not in themselves a contraindication to massage or aromatherapy treatment. Irrespective of the disorder, holistic principles still apply – it is the person who is being treated, not the disease. This does not mean that specific problems cannot sometimes be helped by the judicious use of essential oils with or without massage. If in doubt, do not treat the person without discussing the situation with an experienced aromatherapist working in palliative care, nursing or medical staff. In many cases the doctor or nurse will have limited understanding of the use of massage and essential oils, unless the practice of aromatherapy has been established in the service. There is, however, a growing number of specialist aromatherapists who have worked in palliative care for many years who may be contacted through the local hospice or professional aromatherapy organizations such as IFPA or the National Association of Complementary Therapists in Hospice and Palliative Care (NACTHPC).

Nevertheless, when a patient is expecting aromatherapy, it is important that they receive some form of treatment, providing it is safe and likely to give benefit. If it is unsuitable, an explanation should be given as to why, along with possible alternatives or an appropriate referral.

Aromatherapists need to be sensitive to complex situations and be able to adapt their approach and treatments accordingly. Working with patients in palliative care requires some knowledge and understanding of the disease processes, the medical interventions involved, and how these affect patients and their families. This will then enable the therapist to assess a patient fully and determine the most appropriate aromatherapy treatment.

• Referrals to the aromatherapy service may be for either the patient or the carer, and may come from the patient or carer themselves, a family member or a health professional. Where patients are seen will depend on the particular setting in which the therapist is working, and how the service is organized.

Use of essential oils

Essential oils may be considered safe, as they are used in low concentrations. However, where a boost is needed, the careful clinical application of a higher concentration has proved safe and effective.

Although there is no conclusive evidence that some oils have oestrogen-like properties, it is preferable to err on the side of caution in their use with patients who have oestrogen-dependent tumours (Tisserand & Balacs 1995, Sheppard-Hanger et al. 1994). If there is doubt about the significance of any symptoms and signs found during consultation or the safety of using essential oils and/or massage, the aromatherapist must discuss this with the other professionals on the team.

A ‘nite-lite’ vaporizer with a naked flame is not permitted in hospitals, but may be encountered in the home. It should always be placed in a safe position and never left unattended.

Cautions and contraindications

As the purpose of aromatherapy is to bring a net gain to patients, weighing up any contraindications to the use of essential oils or massage against the potential benefits is very important, especially at a distressing time for a patient.

• Some diseases and/or their treatments can alter a person’s sense of smell and taste, the fragrance of some essential oils perhaps being intensely disliked; although some patients are able to tolerate oils which may bring relief, others find even pleasant smells abhorrent.

• Nausea may be a contraindication, especially if severe or likely to be recurrent, because:

an essential oil (smell) given to relieve nausea – especially if repeated – may at a later date evoke unpleasant memories and/or precipitate nausea and vomiting, i.e. the Pavlov response. The likelihood of this happening is reduced if a blend of two to four oils is used, e.g. Pimpinella anisum, Foeniculum vulgare var. dulce [sweet fennel], Mentha x piperita [peppermint] and Anthemis nobilis [Roman chamomile] (Gilligan 2005).

an essential oil (smell) given to relieve nausea – especially if repeated – may at a later date evoke unpleasant memories and/or precipitate nausea and vomiting, i.e. the Pavlov response. The likelihood of this happening is reduced if a blend of two to four oils is used, e.g. Pimpinella anisum, Foeniculum vulgare var. dulce [sweet fennel], Mentha x piperita [peppermint] and Anthemis nobilis [Roman chamomile] (Gilligan 2005).• Account should be taken of the possible adverse effect the aroma might have on other patients in the room.

• Seizures and epileptic fits can be precipitated by smells – check with staff or family if this is a possibility.

• Skin allergies or sensitivities: patients undergoing palliative chemotherapy often have increased skin sensitivity – if in doubt do a patch test first.

• Be aware of patients with asthma or other respiratory conditions, as volatile substances can precipitate coughing or aggravate breathing difficulty. However, chosen with care, essential oils can bring fast relief. They can help panic attacks associated with severe breathing difficulties (both Whyte and Cooper have found that Myrtus communis [green myrtle] inhaled from a tissue has a calming effect on breathing, especially when severe anxiety is present.

• Cooper has found the following essential oil blend to be useful for respiratory symptoms that occur frequently in lung cancer – shortness of breath, discomfort, upper body tension, potential infection and coughing:

Pinus sylvestris [pine], Cedrus atlantica [cedarwood], Boswellia carteri [frankincense] and Melaleuca viridiflora [niaouli] (see also Appendix A2 on the CD-ROM).

Pinus sylvestris [pine], Cedrus atlantica [cedarwood], Boswellia carteri [frankincense] and Melaleuca viridiflora [niaouli] (see also Appendix A2 on the CD-ROM). The essential oil blend alone can be used in inhalation; it can also be put into carrier oil for gentle upper body massage or into a lotion as a chest rub. Using these methods, patients have frequently reported less upper body tension and discomfort, easier breathing and a feeling of control. Having something to use themselves which is not a medical intervention and for which they have a choice appears to empower the person.

The essential oil blend alone can be used in inhalation; it can also be put into carrier oil for gentle upper body massage or into a lotion as a chest rub. Using these methods, patients have frequently reported less upper body tension and discomfort, easier breathing and a feeling of control. Having something to use themselves which is not a medical intervention and for which they have a choice appears to empower the person.Massage

There is confusion in many people’s minds concerning the use of massage with those who have cancer. Books and courses often say that it is contraindicated, yet massage and aromatherapy are two of the most popular and frequently used therapies in palliative and supportive care (Lewith et al. 2002, Macmillan 2002). This paradoxical situation has arisen because many believe that massage can spread cancer cells through the body by stimulating the lymphatic and vascular circulation. Breathing and the normal physical activity of daily life also stimulate the flow of blood and lymph, and if patients feel well enough they are encouraged to take exercise within their own tolerance level (Sikora K personal communication). Massage would appear to be safe as long as it is gentle and pressure over tumour sites and lymph glands is avoided (Holey &Cook 2003, McNamara 2004).

Unless people with a chronic illness are fairly robust physically and feeling reasonably well, it is unlikely they would tolerate a whole body massage, and in those who can, it would probably be modified – omitting particular areas such as the abdomen or chest. For others, it is more likely to be a part body massage such as the feet or back and shoulders etc., or, in the case of the very frail, holding hands and perhaps stroking.

Contraindications to massage (see also Chapter 7)

In the situations listed below, unaffected areas can be massaged, e.g. the hands or feet, a careful, light ‘holding touch’ can be comforting if tolerated. Remember too, that compresses, sprays or inhalation can all be used when massage is not appropriate:

• unexplained lumps, bumps, swelling or areas of heat – these may be disease related and need to be discussed with the patient’s doctor

• areas where there is unexplained pain, especially over bones, as this may indicate spread of disease to the bone, especially in cancer

• high fever, infection or sepsis, as there is a risk of spreading infection, making the patient feel worse

• areas of the body receiving radiotherapy (and for up to 5 or 6 weeks afterwards), as the skin is extra sensitive after treatment. However, massage with essential oils such as (Melaleuca viridiflora) [niaouli] is recommended a short time (not immediately) before treatment, to strengthen the area (Franchomme & Pénoel 2001 p. 398), but only after discussing it with the patient’s oncologist and radiotherapist to obtain their permission. (See also Appendix A1 on the CD-ROM, Melaleuca viridiflora, observations.)

• a limb or foot where deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is suspected or recently diagnosed – there may be general swelling of the part, with redness and cramp-like pain. People with advanced progressive disease are more susceptible to DVT, especially when they are frail, ill, and have reduced mobility, and it might be there without symptoms (Johnson et al. 1999)

• skin lesions, rashes, recent scar tissue; a red, painful and inflamed patch could indicate cellulitis

• stoma sites, catheters, medication patches; TENS machine pads, syringe driver cannulae and tubing or any other attached medical device

• certain conditions of the heart, lungs, kidneys and liver, as well as cancers, can cause oedema (swelling) of the limbs or other parts of the body – massage could further compromise the heart and lungs

• muscle spasm, rigidity and pain in neurological conditions such as MND, MS and PD: Tavares (2004 p. 34) suggests that massage may be contraindicated, as it can provoke or increase the spasm. However, if tolerated, light gentle treatment has been found to be beneficial.

Use massage with caution in the following circumstances:

• the presence of petechiae on the skin (pin-prick bruising, which indicates a low platelet count); use gentle stroking, or light holding touch only, unless working in a specialist area and able to discuss this with the medical team (Tavares 2004)

• limbs or areas with lymphoedema, when direction and pressure (lack of) are important. Without previous experience, it may be advisable to work in conjunction with a lymphoedema nurse specialist or physiotherapist (Tavares 2004)

• possible side effects of radiotherapy, which can include sore skin, fatigue and local effects depending on the site of irradiation, e.g. neck area (may result in sore, dry mouth and difficulty in swallowing); stomach area (digestive disturbances)

• avoid radiotherapy entry and exit sites for 3–6 weeks, as the effect on the skin is dose related

• frail patients, or those suffering side effects of treatment (see above); massage should be modified in relation to the duration of treatment, the pressure used and the area of the body to be worked on.

Changes affecting treatment

The aromatherapist needs to be aware of situations – some fortunately very rare – that might arise while treating a patient. They need to know what action to take, and who to inform should there be any change in the patient’s condition. The aromatherapist may be the only person who has an opportunity of seeing changes in parts of the patient’s body normally covered with clothing, such as skin lesions or swellings. Consultation with the professional team will decide what changes need to be referred, whom to notify when necessary, and what advice to give patients who report a change in their condition, which could include:

• breathlessness or other breathing problems, severe panic attacks or choking

• epileptic fit or other form of seizure (usually associated with brain tumours).

• haemorrhage: this can be via the mouth,due to coughing or vomiting; from the stomach, nose, vagina, rectum; or from the site of a stoma or wound

• pathological fracture – usually associated with bony cancer metastases

• spinal cord compression occurs in 5–10% of people with cancer (Doyle et al. 1999) and is a neurological emergency. Symptoms may be present for weeks or may occur suddenly, and include pins and needles, sensory loss and weakness (usually in the lower extremities), starting in the feet and moving upwards. If this remains untreated paralysis will ensue, so urgent medical advice should be sought.

Aromatherapists should be able to support the patient through any distressing emotions that may arise, and also be aware of other available options for support and the means of referral. (Those who work in palliative and supportive care, including aromatherapists, may need support themselves, and some form of supervision may be available in their area.)

Therapists should at all times recognize and acknowledge not only their own limitations but also those of aromatherapy, and should know when to refer a patient.

Preventing cross-infection

As a result of their condition and/or treatments, patients’ immune systems are often highly compromised, making them more vulnerable to infection. This is more likely to occur when they are debilitated. It is incumbent on therapists to make themselves familiar with universal infection control procedures if they are working in an environment such as a hospital or hospice, where they may come into contact with patients’ body fluids. Similarly, if treating people with infections such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), advice should be sought on local infection control procedures.

An aromatherapist in good health with good energy levels, following a high standard of hygiene and infection control practices, will have a minimal risk of cross-infection. To prevent this, aromatherapists should follow basic hygiene practices at all times, the most important being thorough hand washing before and after treating a patient (even if gloves have been used), plus the judicious use of essential oils, many of which have been proved to suppress S. aureus and other microorganisms (Moon, Wilkinson, & Cavanagh 2006, Williams et al. 1998, Caelli et al. 2000).

Essential oil blends

The following information is based on Cooper’s experience over more than 16 years of using essential oils in an NHS integrated supportive and palliative care service:

Mouth ulcers due to chemotherapy or disease in the mouth

5 mL Calendula officinalis macerated [marigold] – promotes healing and reduces inflammation (Fleischner 1985, ESCOP, Price & Price 2008

2 drops Commiphora myrrha [myrrh] – contains a high proportion of anti-inflammatory and slightly analgesic sesquiterpenes and antiseptic alcohols

Apply 1 drop directly to the mouth ulcer using a cotton bud three times a day.

Candida in the mouth

1 drop Aniba rosaeodora [rosewood] (or Melaleuca alternifolia [tea tree]) in honey and water – to be used as a mouth rinse 3–5 times a day.

Tea tree is perfect for treating mucous membrane infections of the mouth and gums, and for Candida-related infections (Schnaubelt 1998).

Rosewood contains up to 90% alcohols, which are antifungal, antiseptic and free from irritation.

Malodour due to discharging or fungating wounds

The following oils appear to be useful in practice although they have not been tested for their odour fighting effects.

Vaporize Thymus vulgaris ct. thymol, ct. linalool [sweet thyme] with Eucalyptus citriodora [lemon scented gum], or Citrus bergamia [bergamot] with Lavandula angustifolia

As an alternative or addition to vaporization, place a few drops of the oils on a pad and place over the top of any wound dressings.

Case 15.3 Dry cracked skin on feet and legs

Assessment

Mrs B (62) was diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She used to be active and finds it difficult to cope with the present loss of independence. She is on portable oxygen, enabling her to get out of the house, but is frustrated by being unable to do things she would like to do and wants to get back to work. Mrs B becomes very breathless on exertion and feels panicky in enclosed spaces; most of her joints ache, she aches particularly in her chest, and gets cramp regularly (a side effect of seretide inhalers).

Mrs B has suffered with painful, cracked and dry skin on her feet and elbows for the last 2½ years, during which time she has tried numerous proprietary lotions and creams, with little or no relief.

Intervention

An aromatherapy blend was prescribed for her to apply morning and night:

70 mL white carrier lotion, 20 mL shea butter and 10 mL Calendula officinalis (to aid healing) were blended to create an emollient base to retain moisture. Essential oils added were:

• 5 drops Lavandula angustifolia – antibacterial, anti-inflammatory

• 5 drops Boswellia carteri [frankincense] – calming, anti-inflammatory, cicatrizant 2 drops Melaleuca alternifolia [tea tree] – antifungal, anti-inflammatory, phlebotonic

• 2 drops of Santalum album [sandalwood] – skin healing (anecdotal evidence).

Outcome

Mrs B used the cream twice daily for 3 months, the improvement being noticeable after 2 weeks, and the texture of her skin gradually improved. She now uses the blend less often: the skin on her legs, feet and elbows is visibly better. She is pleased with the result and was able to enjoy Christmas free from the usual discomfort and pain.

Pruritus (skin itching)

A specific blend of essential oils may be combined with a lotion base for symptoms that may not be responding to medical treatment, for example itchy skin complaints, or to help with pain relief (Clark, 2010).

In 15 years Cooper has not found anything better than the (Shirley Price’s recipe of Santalum album, Lavandula angustifolia and Mentha x piperita in white lotion; she uses it extensively for pruritus associated with liver disease and jaundice. It often gives more relief than any prescribed medication, and patients frequently say it is the best relief they have had. The excellent effect is well known in the Walsall area, with Macmillan nurses, hospice nurses and palliative care consultants all requesting it for their patients.

For patients with a sensitivity to menthol, Anthemis nobilis [Roman chamomile] has been used to good effect in place of Mentha piperita.

The following blends have been used by the specialist complementary therapy team in NHS Walsall working with Cooper after receiving positive evaluation and feedback from users.

Bone/joint pain or discomfort

A blend of 50 mL carrier lotion with the following essential oils has consistently proved effective in relieving this type of pain.

Commiphora myrrha [myrrha] – anti-inflammatory

Boswellia carteri [frankincense] – analgesic, anti-inflammatory

Melaleuca viridiflora [niaouli] – analgesic, anti-inflammatory

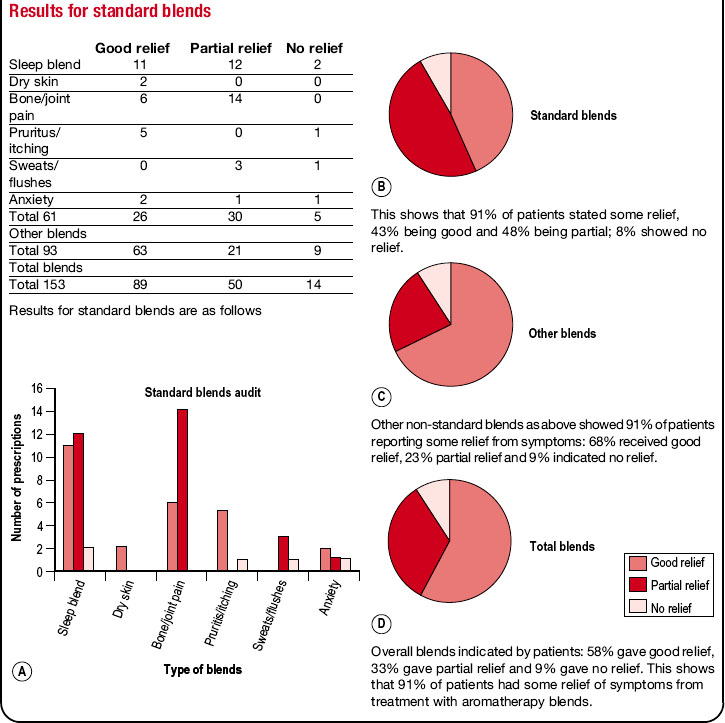

In an audit carried out in NHS Walsall during 2009 it gave partial or good relief to 100% of patients who used it, being the only one in the audit to give relief to all users (see Box 15.2).

Box 15.2 NHS Community Health – Complementary Therapy Audit Aromatherapy Prescription Blends audit – April 2009 – December 2009

Aromatherapy blends are given to patients as a support to symptom control in cancer care, palliative and end of life care.

Standard blends developed by the team have previously shown effectiveness to help relieve the following common problems: anxiety, insomnia, bone/joint pain, dry skin, pruritus (itching) and hot flushes.

Other blends are provided for other symptoms or for the above problems as an alternative if needed.

Each blend is based on the chemical components present in essential oils and these are blended to give the best synergy and chemical combination for optimum therapeutic effect.

Reasons for the audit

a) To discover to what degree patients felt the blend had relieved their problem or symptom, i.e. good relief, partial relief, no relief or made symptoms worse

b) To discover if the patients experienced any negative side effects from the prescription blend

c) To obtain patients’ comments of the effectiveness of aromatherapy blends supplied by the complementary therapy team

A simple audit questionnaire was developed and given to each patient who received a blend (see Box 15.3).

Sample of comments made by patients on audit questionnaires

• Excellent service and I would like to thank the NHS for making it available.

• The blends helped with relaxation – I did not feel so tense after using blends.

• Inhaling the oil gives me a uplifting experience and relives the nausea.

• Eases pain – no analgesic pain killers taken now due to this cream.

• Feels much more comfortable, skin less dry, less itching and feet no longer feel like the skin is cracking – appear better visually.

• Just to say thank you for this cream – it really works. Thank you for the therapy and such fantastic service and staff.

• Very effective to help with nausea after chemotherapy.

• Very pleasant smell and very easy to use, easily absorbed – helps peripheral neuropathy.

Findings and recommendations

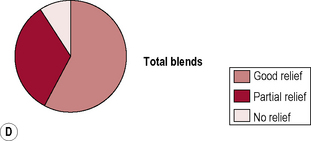

The outcome of the audit is extremely positive, indicating that patients welcome these complementary approaches as a beneficial supportive treatment option in their care. Figures from the audit indicate that 91% of patients had relief from symptoms by using these blends, 58% had good relief and 33% had some relief. Only two patients out of 139 answered yes to negative effects as a result of using blends.

It appears that individual blending for patients on a one to one basis is slightly more effective than standard blending. The team recommends, however, that all but one standard blend should continue to be used as the success rate is good.

The blend provided for bone and joint pain gave relief to 100% of patients, which may indicate a case for further research, as some patients felt that it was better than non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

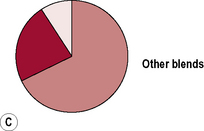

Box 15.3 Results for standard blends

Results for standard blends are as follows

This shows that 91% of patients stated some relief, 43% being good and 48% being partial; 8% showed no relief.

Other non-standard blends as above showed 91% of patients reporting some relief from symptoms: 68% received good relief, 23% partial relief and 9% indicated no relief.

Overall blends indicated by patients: 58% gave good relief, 33% gave partial relief and 9% gave no relief. This shows that 91% of patients had some relief of symptoms from treatment with aromatherapy blends.

Assessment

Sarah (52) was diagnosed with myeloma. She was low in mood, tearful, suffering from anxiety, and had considerable pain in her shoulders. In 2002 she received radiotherapy and spinal surgery with rods and plates, and also had a spinal fusion of T4–T7.

Intervention

A course of reflexology did not help the pain. Aromatherapy was tried to help reduce the discomfort between the shoulders and the pain to the right shoulder and side of neck.

A blend of essential oils in sunflower oil was used.

• Zingiber officinalis [ginger] – analgesic, general tonic

Gentle effleurage was given to the upper back and trapezius muscle, which was very hard and tense. After a few minutes Sarah commented that she could feel the heat penetrating the muscle and she began to relax.

For 5 weeks Sarah had a weekly 20-minute massage treatment and was given a lotion incorporating the same oils for use every morning and evening.

Dry, cracked, fingertips (often seen as a side effect of cancer drug treatments)

Excellent results were achieved from a blend of:

100 mL carrier lotion, 25 mL shea butter and 15 mL calendula oil with 5 drops each of the following analgesic, anti-inflammatory and cicatrizant oils:

Boswellia carteri [frankincense] and Lavandula angustifolia

2 drops of Melaleuca alternifolia [Tea tree] – also anti-infectious

2 drops Santalum album [sandalwood] – anti-infectious, decongestant and moisturizing to the skin.

Evaluation stated relief of symptoms in 48 hours.

Further use of this blend has proved helpful for very dry skin and also on patients prone to cellulites; definite improvements were noted.

Client assessment

T was a 75-year-old man diagnosed with cancer of the larynx; he had had surgery for tumour removal 6 months ago and had completed a course of radiotherapy to the neck and right side of his face. He was now 7 days post radiotherapy.

T’s main complaint was a soreness and burning sensation to his face and neck, which meant he was unable to shave. This upset him greatly, as he took pride in his appearance: wearing a shirt and tie was difficult as this rubbed on the skin on his neck. Use of an aqueous cream had not helped.

Intervention

An aromatherapy blend was mixed to alleviate T’s discomfort and was applied twice daily to his cheeks, chin and neck for 1 week.

Outcome

A week later T was clean shaven and wearing his tie. The gel had provided relief from the burning and soreness (he said ‘the scent wasn’t too bad either’!). T continued to use the gel for 1 month, reducing the application to once daily, after which he discontinued it. No further soreness of burning sensation was experienced.

Inflamed sore, cracked, fingers and toes (Possible side effect of chemotherapy tablets)

90 mL carrier lotion, 10 mL evening primrose oil with 5 drops each of:

Rosa damascena [rose otto] – anti-infectious, anti-inflammatory, cicatrizant

Santalum album – properties as above

Pelargonium graveolens [geranium] – analgesic, anti-infectious, anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, cicatrizant

Good results have been achieved after 7 days use of this blend – hands softened and healed and feet able to be walked on again.

Summary

With its popularity continuing to grow, aromatherapy is one of the three most frequently used complementary therapies provided by hospices and palliative care units in the UK – the other two being massage and reflexology (Wilkes 1992; Macmillan Cancer Relief 2002).

The effects of caring touch should never be underestimated, the shared experience between the giver and the recipient being to their mutual benefit. Aromatherapy massage and therapeutic touch are pleasant, non-clinical experiences, and the use of essential oils provides another clinical tool in healthcare practice, giving both professionals and patients a further choice along the healing or therapeutic pathway.

Addington-Hall J. Reaching out: specialist palliative care services for older adults with non-malignant diseases. London: NCHPCS; 1998.

Ahmedzai S.H. COPD and Palliative and Supportive care. NHS Evidence–respiratory. Respiratory Specialist Library; 2006.

Alexander M. Aromatherapy and immunity: how the use of essential oils aids immune potentiality. Int. J. Aromather.. 2001;11(4):220-224.

Bowers L.J. To what extent does aromatherapy use in palliative care improve quality of life and reduce levels of psychological distress? A literature review. Int. J. Aromather.. 2006;16(1):27-35.

Caelli M., Porteous J., Carson C.F., Heller R., Riley T.V. Tea tree oil as an alternative topical decolonisation agent for methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus. J. Hosp. Infect.. 2000;46(2000):236-237.

Clark R. Care of the dying and deceased patient. In: Jevon P., editor. A practical guide for nurses. UK: Wiley Blackwell, 2001.

Corner J., Cawley N., Hildebrand S. An evaluation of the use of massage and essential oils on the well-being of cancer patients. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs.. 1995;1(2):67-73.

DoH. End of Life Care Strategy – promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. London: Department of Health; 2008.

Downer S.M., Cody M.M., McCluskey P., Wilson P.D., Arnott S.J., Lister T.A., et al. Pursuit and practice of complementary therapies by cancer patients receiving conventional treatment. Br. Med. J.. 1994;309(6947):86-89.

Doyle D., Hanks W.C., MacDonald N., editors, Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. second ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:729.

Escop, vol. 3. Proposals for European monographs on Calendulae flos / Flos cum herba

Fleischner A.M. Plant extracts: to accelerate healing and reduce inflammation. Cosmetics ad Toiletries. 1985;100:45.

Franchomme P., Pénoël D. l’Aromathérapie exactement. Limoges: Jallois; 2001.

Fujiwara R., Komori T., Yokoyama M.M. Psychoneuroimmunological benefits of aromatherapy. Int. J. Aromather.. 2002;12(2):77-82.

Gatti G., Cajola R. L’azione della essenze sul sysema nervosa. Rivista Italiana delle Essenze e Profumi. 1923;5(12):133-135.

Gilligan N.P. The palliation of nausea in hospice and palliative care patients with essential oils of Pimpinella anisum [aniseed], Foeniculum vulgare var. dulce [sweet fennel], Anthemis nobilis [Roman chamomile] and Mentha x piperita [peppermint]. Int. J. Aromather.. 2005;15:163-167.

Gore J.W., Brophy C.J., Greenstone M.A. How well do we care for patients with end stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)? A comparison of palliative care and quality of life in COPD and lung cancer. Thorax. 2000;55:1000-1006.

Grealish L., Lomansney A., Whiteman B. Foot massage. Cancer Nurs.. 2000;23(3):237-243.

Hadfield N. The role of aromatherapy massage in reducing anxiety in patients with malignant brain tumours. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs.. 2001;7(6):279-285.

Holey E., Cook E. Evidence-Based Therapeutic Massage a practical guide for therapists. Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

Imanishi J., et al. Anxiolytic Effect of Aromatherapy Massage in Patients with Breast Cancer. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine eCAM 2009. 2007;6(1):123-128.

Kuriyama H., Watanabe S., Nakaya T., Shigemori I., Kita M., Yoshida N., et al. Immunological and psychological benefits of aromatherapy massage. Advance Access Publication eCAM. 2005;2(2):179-184. Oxford University Press

Lee W.H., Lee L. The book of practical aromatherapy. New Canaan, CT: Keats; 1992:125.

Lewith, et al. Complementary Cancer Care in Southampton: a survey of staff and patients. Complement. Ther. Med.. 2002;10:100-106.

Macmillan Cancer Relief. Directory of Complementary Therapy Services in UK Cancer Care. London: Macmillan Cancer Relief; 2002.

Marieb E. Human Anatomy and Physiology, fourth ed. Addison Wesley World Student Series; 1998.

McCaffery M., Beeb A. Pain, Clinical Manual for Nursing Practice. The CV Mosby Company; 1989.

McNamara P. Massage for people with cancer, third ed. Wandsworth, London: The Cancer Resource Centre; 2004.

Moon T., Wilkinson J.M., Cavanagh H.M.A. Antibacterial activity of essential oils, hydrosols and plant extracts from Australian grown Lavandula spp. Int. J. Aromather.. 2006;16:9-11.

National Council for Palliative Care. Palliative and Supportive Care Explained. London: National Council for Palliative Care; 2010.

National Statistics Online. Ageing – fastest increase in the oldest yet. Office of National Statistics; August 2009.

NHS Evidence – supportive and palliative care. Introduction to end-stage renal disease in palliative and supportive care. London: National Institute of Clinical Excellence; 2007.

NICE. Guidelines for heart failure. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2003.

NICE. Guidance on Cancer Services: Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2004.

Pan C.X., Morrison R., Ness J., Fugh-Berman A., Leipzig R.M. Complementary and alternative medicine in the management of pain, dyspnoea, and nausea and vomiting near the end of life. A systematic review. J. Pain Symptom Manage.. 2000;20(5):374-387.

Price L., Price S. Carrier oils for aromatherapy and massage. 2008. Riverhead, Stratford-upon-Avon

Price S. Aromatherapy and your emotions. London: Thorsons; 2000.

Schnaubelt K. Advanced Aromatherapy. Vermont: Healing Arts press; 1998.

Sheppard-Hanger S. The Aromatherapy Practitioner Manual. Tampa, Florida, USA: Atlantic Institute of Aromatherapy; 1994.

Tavares M. National Guidelines for the Use of Complementary Therapies in Supportive and Palliative Care. The Prince of Wales Foundation for Integrated Health and The National Council for Hospice and Supportive Care Services May; 2003.

Tisserand R. The Art of Aromatherapy. Saffron Walden, UK: The C.W. Daniel Ltd; 1992.

Tisserand R., Balacs T. Essential Oil Safety Guide, A guide for Health Care Professionals. Churchill Livingstone; 1995.

Twycross R.G., Lack S. Therapeutics in Terminal Cancer. Churchill Livingstone; 1984.

WHO. Cancer pain relief and palliative care. WHO; 1990. A report of the WHO Expert Committee. WHO Technical report series 804, WHO

Wilkes E. Complementary therapy in hospice and palliative care. Sheffield Trent Paliative Care Centre and Help the Hospices; 1992.

Wilkinson S., Aldridge J., Salmon I., Cain E., Wilson B. An evaluation of aromatherapy massage in palliative care. Palliat. Med.. 1999;13(5):409-417.

Wilkinson S., Love S.B., Westcombe A.M., Gambles M.A., Burgess C., Cargill A., et al. Effectiveness of Aromatherapy Massage in the Management of Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Cancer: A Multicentre Randomised Control Trial. J. Clin. Oncol.. 2007;25(5):532-539.

Williams L.R., Stockley J.K., Yan W., Home V.N. Essential oils with high antimicrobial activity for therapeutic use. Int. J. Aromather.. 1998;8(4):30-40.

CancerBacup. www.cancerbacup.org. 3 Bath Place, Rivington Street, London EC2A 3DR

Help the Hospices. www.helpthehospices.org.uk.

Macmillan Cancer Support Learn Zone. www.learnzone.macmillan.org.uk.

Marie Curie Cancer Care. www.mariecurie.org.uk.

Penny Brohn (previously Bristol Cancer Help Centre). www.pennybrohncancercare.org. Helpline: 0845 123 2310

Sue Ryder Care. (originally Sue Ryder Foundation) a registered charity providing specialist palliative and neurological care services. 114–118 Southampton Row, London WC1B 5AA; Tel: 020 7400 0441 E-mail: info@suerydercare.org Website: www.suerydercare.org.

Association of Complementary Therapists in Hospice and Palliative Care (NACTHPC), E-mail nacthpc@hotmail.com.

International Federation of Professional Aromatherapists. 82 Ashby Road, Hinckley, Leicestershire LE10 1SN; Tel: 01455 637987; e-mail: admin@ifparoma.org Website: www.ifparoma.org.