Chapter 7 Self-help strategies

The appendix for this chapter provides material offered within this chapter in a copyright-free form for patient support.

Aims and sources

This chapter covers topics that are as varied as the problems our patients bring to us to solve or assist with, falling as they do under the broad classifications discussed in earlier chapters: biochemical, biomechanical and psychosocial.

Some of the biomechanical self-help approaches in this chapter are derived from a series of copyright-free articles by Craig Liebenson DC (2001) that were written for the Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, entitled ‘Self-help for the clinician’ and ‘Self-help for the patient’. The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr Liebenson’s far-sighted contribution to the field of rehabilitation, with earnest appreciation. Other strategies, designed for patient use, that have been included in this chapter are summarized from the text Multidisciplinary Approaches to Breathing Pattern Disorders (Chaitow et al 2002) of which one of the authors of this text (LC) is a co-author. Grateful thanks are due to the other authors, Dinah Bradley Morrison PT (1998) and Chris Gilbert PhD (2002).

Additional strategies presented derive from diverse sources, some of which will be acknowledged (if the source is known), while others are based on the personal clinical experience of the authors.

Coherence, compliance and concordance

Patients seldom automatically do as they are advised. Unless the required activity is understood and its relevance to the individual’s health status made clear, the chance of regular application of anything, whether it involves exercise, dietary reform, breathing modification or lifestyle change, is small.

Gilbert (2002) provides insights into what is a very real problem for anyone trying to encourage a patient to modify habitual patterns of use, whether this relates to posture, breathing or other activities. Gilbert’s focus is on breathing, which, as he points out, has its own unique dynamics.

When the topic is ‘learning to breathe better’, the teaching/learning situation as usually set up presents a quandary. The patient is informed of an erroneous breathing pattern and is offered help in learning to correct it. This exchange takes place during rational verbal interaction. But the breathing problem emerges from a system that is far from the rational verbal realm. Changing one’s breathing is not the same as improving one’s tennis serve or ski technique; breathing is a continuous process and fully automatic in the sense that it does not require conscious supervision. Also, since breathing is so essential to life, there are multiple controls and safeguards to ensure its operation. Teaching someone to interfere in this process is presumptuous. We can commandeer the breathing mechanism temporarily with full attention, but as soon as the mind wanders elsewhere, automatic mechanisms return. Yet progress is quite possible. The interaction between voluntary and involuntary can be addressed with respect for the deep, protective systems which are trying to ensure adequate air exchange in spite of conflicting messages from various areas of the brain. The problems which create the need for breathing retraining may derive from emotional sources or from injuries, poor posture or habits acquired through compensation for some other factor. Assuming there is no current structural or medical impediment to restoring normal breathing, the challenge is to allow the body to breathe on its own, in line with the metabolic needs of the moment. To change a chronic breathing pattern it is necessary to make the conscious intervention less conscious, more habitual.

This, then, is the challenge we all face: helping someone to understand a/ why change is needed, b/ offering a means whereby the change can be achieved and then, c/encouraging the process of turning a strange new experience into a habit.

In Volume 1, second edition, Chapter 8 (pages 173 and 174 in particular – see also Fig. 8.3 in that chapter) rehabilitation and compliance issues are discussed. An abbreviated summary of some of the key elements of that discussion is included in Box 7.1 of this text.

Box 7.1 Summary of rehabilitation and compliance issues from Volume 1, Chapter 8

Psychosocial factors in pain management: the cognitive dimension

Liebenson (1996) states:

Motivating patients to share responsibility for their recovery from pain or injury is challenging. Skeptics insist that patient compliance with self-treatment protocols is poor and therefore should not even be attempted. However, in chronic pain disorders, where an exact cause of symptoms can only be identified 15% of the time, the patient’s participation in their treatment program is absolutely essential (Waddell 1998). Specific activity modification advice aimed at reducing exposure to repetitive strain is one aspect of patient education (Waddell et al 1996). Another includes training in specific exercises to perform to stabilize a frequently painful area (Liebenson 1996, Richardson & Jull 1995). Patients who feel they have no control over their symptoms are at greater risk of developing chronic pain (Kendall et al 1997). Teaching patients what they can do for themselves is an essential part of caring for the person who is suffering with pain. Converting a pain patient from a passive recipient of care to an active partner in their own rehabilitation involves a paradigm shift from seeing the doctor as healer to seeing him or her as helper (Waddell et al 1996).

Guidelines for pain management (Bradley 1996)

• Assist the person in altering beliefs that the problem is unmanageable and beyond his control.

• Inform the person about the condition.

• Assist the person in moving from a passive to an active role.

• Enable the person to become an active problem solver and to develop effective ways of responding to pain, emotion and the environment.

• Help the person to monitor thoughts, emotions and behaviors and to identify how internal and external events influence these.

• Give the person a feeling of competence in the execution of positive strategies.

• Help the person to develop a positive attitude to exercise and personal health management.

• Help the person to develop a program of paced activity to reduce the effects of physical deconditioning.

• Assist the person in developing coping strategies that can be continued and expanded once contact with the pain management team or health-care provider has ended.

Barriers to progress in pain management (Gil et al 1988, Keefe et al 1996)

• Litigation and compensation issues, which may act as a deterrent to compliance.

• Distorted perceptions about the nature of the problem.

• Beliefs based on previous diagnosis and treatment failure.

• Lack of hope created by practitioners whose prognosis was limiting (‘Learn to live with it’).

• Dysfunctional beliefs about pain and activity.

• Negative expectation about the future.

• Lack of awareness of the potential for (self) control of the condition.

Wellness education (Vlaeyen et al 1996)

Initial education in pain management should give the person information to help them make an informed decision about participating in a program. Such a program should offer a credible rationale for engaging in management of the problem, as well as information regarding:

Goal setting and pacing (Bucklew 1994, Gil et al 1988)

Rehabilitation goals should be set in three separate fields.

• Physical – the number of exercises to be performed, or the duration of the exercise, and the level of difficulty.

• Functional tasks – this relates to the achievement of functional tasks of everyday living.

• Social – where goals are set relating to the performance of activities in the wider social environment. These should be personally relevant, interesting, measurable and, above all, achievable.

Low back pain rehabilitation

In regard to rehabilitation from painful musculoskeletal dysfunction. Liebenson (1996, 2007) maintains:

The basic progressions to facilitate a ‘weak link’, and improve motor control, include the following:

• train awareness of postural (neutral range joint) control during activities

• prescribe beginner (‘no brainer’) exercises

• facilitate automatic activity in ‘intrinsic’ muscles by reflex stimulation

• progress to more challenging exercises (i.e. labile surfaces, whole-body exercises)

Concordance

Compliance, adherence and participation are extremely poor regarding exercise programs (as well as other health enhancement self-help programs), even when the individuals felt that the effort was producing benefits. Research indicates that most rehabilitation programs report a reduction in participation in exercise (Lewthwaite 1990, Prochaska & Marcus 1994). Wigers et al (1996) found that 73% of patients failed to continue an exercise program when followed up, although 83% felt they would have been better if they had done so. Participation in exercise is more likely if the individual finds it interesting and rewarding.

Research into patient participation in their recovery program in fibromyalgia settings has noted that a key element is that whatever is advised (exercise, self-treatment, dietary change, etc.) needs to make sense to the individual, in his own terms, and that this requires consideration of cultural, ethnic and educational factors (Burckhardt 1994, Martin 1996). In general, most experts, including Lewit (1992), Liebenson (2007) and Lederman (1997), highlight the need (in treatment and rehabilitation of dysfunction) to move as rapidly as possible from passive (operator-controlled) to active (patient-controlled) methods. The rate at which this happens depends largely on the degree of progress, pain reduction and functional improvement.

Individuals should be encouraged to listen to their bodies and to never do more than they feel is appropriate in order to avoid what can be severe setbacks in progress when they exceed their current capabilities.

Routines and methods (homework) should be explained in terms that make sense to the person and his caregiver(s). Written or printed notes, ideally illustrated, help greatly to support and encourage compliance with agreed strategies, especially if simply translated examples of successful trials can be included as examples of potential benefit. Information offered, spoken or written, needs to answer in advance questions such as:

• Why is this being suggested?

• What evidence is there of benefit?

• What reactions might be expected?

• What should I do if there is a reaction?

• Can I call or contact you if I feel unwell after exercise (or other self-applied treatment)?

It is useful to explain that all treatment makes a demand for a response (or several responses) on the part of the body and that a ‘reaction’ (something ‘feels different’) is normal and expected and is not necessarily a cause for alarm but that it is OK to make contact for reassurance.

It may be useful to offer a reminder that symptoms are not always bad and that change in a condition toward normal may occur in a fluctuating manner, with minor setbacks along the way.

It can be helpful to explain, in simple terms, that there are many stressors being coped with and that progress is more likely to come when some of the ‘load’ is lightened, especially if particular functions (digestion, respiratory, circulation, etc.) are working better.

A basic understanding of homeostasis is also helpful (‘broken bones mend, cuts heal, colds get better – all examples of how your body always tries to heal itself’) with particular emphasis on explaining processes at work in the patient’s condition.

The patient exercises in this chapter are presented in appropriately headed boxes. Information for the patients to encourage better compliance or to offer background data from which they may derive encouragement to comply with whatever is suggested for self-application is also given. In some instances combinations of these presentations are used.

Background information for the clinician will mainly be found in Chapter 6, although in some instances there are brief introductory notes for the clinician in this chapter as well.

What we can learn from research into compliance

In the 2nd edition of Rehabilitation of the Spine, Liebenson (2007) embraces a remarkable shift to a new patient-centered model of management of spine disorders. ‘Rather than focusing merely on pathology and symptoms, the emphasis is on recovery, reactivation, and self-management. Passive care approaches utilizing medication, modalities, and manipulation are being replaced with an active self-care paradigm.’ He provides overwhelming evidence in support of these concepts along with the ‘reasons why a traditional biomedical way of thinking is far from ideal for a multifactorial problem such as spine pain.’

A number of studies have looked at the basic question: ‘Why do some people not comply with home-exercise or other self-help strategies that are known to be able to help their condition?’

Åsenlöf et al (2009) examined the long-term effects of a Tailored Behavioural Treatment (TBT) protocol, compared with an Exercise Based Physical Therapy (EBPT) protocol. Compliance and outcomes were far better in the TBT group. One interesting outcome, apart from the compliance issue, was that fear of movement/(re)injury increased in the EBPT-group, but not the TBT group.

The key elements of TBT are summarized as follows:

• Identify goals for daily activity – create a priority list of goals

• Select a first goal to target based on an activity in everyday-life - this could be almost anything that is relevant to the patient, for example, a particular distance to be able to walk pain free.

• Identify physical activity of the person’s own choice, as well as intermediate objectives.

• There should be discussion of hypothesized physical, cognitive, behavioral, and psychosocial features that relate to the pain or dysfunction

• The skills required to achieve the goals that have been chosen should be identified and basic exercises practiced, particularly as these relate to everyday-life situations.

• As initial gains are made, additional goals on the priority list should be identified and prioritized to extend the application of acquired skills to new activities and situations

• Maintenance and relapse prevention, involving strategies for maintenance of new skills, should be incorporated.

Obviously a great deal of effort and collaboration is required in such planning – but it makes sense that outcomes are likely to be better (and they are) than by simple ‘homework’ prescription.

Howard & Gosling (2008) found that patients who have a positive attitude, more education and more previous positive experiences in relation to health, sport and exercise are more likely to be compliant to practitioner prescribed exercise rehabilitation programs. They also found that personal characteristics – such as attitude, education and past experience relating to health, sport and exercise – need to be assessed prior to exercise prescription. Gaining an early insight into whether a patient is likely to be ‘compliant’ or ‘non-compliant’ can provide practitioners a basis upon which to design their rehabilitation processes.

Biomechanical self-help methods

Positional release self-help methods (for tight, painful muscles and trigger points) (Chaitow 2006)

When a person feels pain, the area that is troubled will usually have some degree of local muscle tension, even spasm, and there is probably a degree of local circulatory deficiency, with not enough oxygen getting to the troubled area and not enough of the normal waste products being removed. Massage and stretching methods can often help these situations, even if only temporarily, but massage is not always available or may be impractical if the region is out of reach and you are on your own.

If the pain problem is severe, stretching may help but at times this may be too uncomfortable. There is another way of easing tense, tight muscles and improving local circulation, called ‘positional release technique’ (PRT). In order to understand this method a brief explanation is needed.

It has been found in osteopathic medicine that almost all painful conditions relate in some way to areas which have been in some manner strained or stressed, either quickly in a sudden incident or gradually over time because of habits of use, poor breathing habits, posture and other influences. When these ‘strains’ – whether acute or chronic – develop, some tissues (including muscles, fascia, ligaments, tendons, nerve fibers) may be stretched while others are in a contracted or shortened state. It is not surprising that discomfort emerges out of such patterns or that these tissues will be more likely to become painful when asked to do something out of the ordinary, such as lifting or stretching. The shortened as well as the overstretched structures may have lost their normal elasticity, at least partially. It is therefore common for strains to occur in tissues that are already chronically stressed in some way.

What has been found in PRT is that if the tissues that are short are gently eased to a position in which they are temporarily made even shorter, a degree of comfort or ‘ease’ is achieved, which can remove pain from the area. They may also then begin to function more normally and allow movement or use without (or with less) pain.

But how are we to know in which direction to move tissues that are very painful and tense? There are some very simple rules and we can use these on ourselves in an easy-to-apply ‘experiment’. Now, perform the steps in Box 7.2.

Box 7.2 Patient self-help. PRT exercise (Chaitow 2007)

• Sit in a chair and, using a finger, search around in the muscles of the side of your neck, just behind your jaw, directly below your ear lobe about an inch. Most of us have painful muscles here. Find a place that is sensitive to pressure.

• Press just hard enough to hurt a little and grade this pain for yourself as a ‘10’ (where 0 = no pain at all). However, do not make it highly painful; the 10 is simply a score you assign.

• While still pressing the point bend your neck forward, very slowly, so that your chin moves toward your chest.

• Keep deciding what the ‘score’ is in the painful point.

• As soon as you feel it ease a little start turning your head a little toward the side of the pain, until the pain drops some more.

• By ‘fine tuning’ your head position, with a little turning, sidebending or bending forward some more, you should be able to get the score close to ‘0’ or at least to a ‘3’.

• When you find that position you have taken the pain point to its ‘position of ease’ and if you were to stay in that position (you don’t have to keep pressing the point) for up to a minute and a half, when you slowly return to sitting up straight the painful area should be less sensitive and the area will have been flushed with fresh oxygenated blood.

• If this were truly a painful area and not an ‘experimental’ one, the pain would ease over the next day or so and the local tissues would become more relaxed.

• You can do this to any pain point anywhere on the body, including a trigger point, which is a local area that is painful on pressure and that also refers a pain to an area some distance away or that radiates pain while being pressed. It may not cure the problem (sometimes it will) but it usually offers ease.

The rules for self-application of PRT are as follows.

• Locate a painful point and press just hard enough to score ‘10’.

• If the point is on the front of the body, bend forward to ease it and the further it is from the mid-line of your body, the more you should ease yourself toward that side (by slowly sidebending or rotating).

• If the point is on the back of the body ease slightly backward until the ‘score’ drops a little and then turn away from the side of the pain, and then ‘fine tune’ to achieve ease.

• Hold the ‘position of ease’ for not less than 30 seconds (up to 90 seconds) and very slowly return to the neutral starting position.

• Make sure that no pain is being produced elsewhere when you are fine tuning to find the position of ease.

• Do not treat more than five pain points on any one day as your body will need to adapt to these self-treatments.

• Expect improvement in function (ease of movement) fairly soon (minutes) after such self-treatment but reduction in pain may take a day or so and you may actually feel a little stiff or achy in the previously painful area the next day. This will soon pass.

• If intercostal muscle (between the ribs) tender points are being self-treated, in order to ease feelings of tightness or discomfort in the chest, breathing should be felt to be easier and less constricted after PRT self-treatment. Tender points to help release ribs are often found either very close to the sternum (breast bone) or between the ribs, either in line with the nipple (for the upper ribs) or in line with the front of the axilla (armpit) (for ribs lower than the 4th) (Fig. 7.1).

• If you follow these instructions carefully, creating no new pain when finding your positions of ease and not pressing too hard, you cannot harm yourself and might release tense, tight and painful muscles.

Muscle energy self-help methods (for tight, painful muscles and trigger points)

When a muscle is contracted isometrically (which means contraction without any movement being allowed) for around 10 seconds, that muscle as well as the muscle(s) that performs the opposite action to it (called the antagonist) will be far more relaxed and can much more easily be stretched than before the contraction. This is known as ‘muscle energy technique’ (MET).

You can use MET to prepare a muscle for stretching if it feels tighter than it ought to, before gently stretching it. It is also useful for self-treating muscles in which there are trigger points.

In this sort of exercise light contractions only are used, involving no more than a quarter of your available strength. Now, practice the steps in Box 7.3.

Box 7.3 Patient self-help. MET neck relaxation exercise (Chaitow 2004)

Phase 1

• Sit close to a table with your elbows on the table and rest your hands on each side of your face.

• Turn your head as far as you can comfortably turn it in one direction, say to the right, letting your hands move with your face, until you reach your pain-free limit of rotation in that direction.

• Now use your left hand to resist as you try to turn your head back toward the left, using no more than a quarter of your strength and not allowing the head to actually move. Start the turn slowly, building up force which is matched by your resisting left hand, still using 25% or less of your strength.

• Hold this push, with no movement at all taking place, for about 7–10 seconds and then slowly stop trying to turn your head left.

• Now turn your head round to the right as far as is comfortable.

• You should find that you can turn a good deal further than the first time you tried, before the isometric contraction. You have been using MET to achieve what is called postisometric relaxation in tight muscles that were restricting you.

Phase 2

• Your head should be turned as far as is comfortable to the right and both your hands should still be on the sides of your face.

• Now use your right hand to resist your attempt to turn (using only 25% of strength again) even further to the right starting slowly, and maintaining the turn and the resistance for a full 7–10 seconds.

• If you feel any pain you may be using too much strength and should reduce the contraction effort to a level where no pain at all is experienced.

• When your effort slowly stops see if you can now go even further to the right than after your first two efforts. You have been using MET to achieve a different sort of release called reciprocal inhibition.

You have now used MET in two ways, using the muscles that need releasing and then using their antagonists. This improvement in the range of rotation of your neck should be achieved even if there was no obvious stiffness in your neck muscles before the start of the exercise. It should be even greater if there was obvious stiffness.

Both methods work to release tightness for about 20 seconds, which then allows you the chance to stretch tight muscles after the isometric contraction.

MET contractions are working with normal nerve pathways to achieve a release of undesirable excessive tightness in muscles. You can use MET by contracting whatever part of your body is tight or needs stretching and especially any muscle that houses a trigger point. Always contract lightly using either the tight muscle itself or its antagonist, hold for 10 seconds, then stretch painlessly.

Exercises for spinal flexibility

As we age and especially as we adapt to the multiple mechanical stresses and injuries of life, the muscles which support and move the spine, as well as other soft tissues such as the tendons and supporting fascia, and the joints themselves, can lose their ability to efficiently perform all these movements. When it is healthy and supple, the spine can flex (bend forward), extend (bend backward), sidebend to each side, as well as rotate (twist).

The four exercises described below (one flexion – Box 7.4, one extension – Box 7.5 and two rotation – Box 7.6) as well as those in Box 7.7, will help maintain flexibility or help to restore it if the spine is stiff. They should not be done if they cause any pain. Do these in sequence every day to maintain suppleness. The exercises described are designed to safely restore and maintain this flexibility

• If it hurts to perform any of the described exercises or you are in pain after their use, stop doing them. Either they are unsuitable for your particular condition or you are performing them incorrectly, too energetically or excessively.

• Remember that these exercises are prevention exercises, meant to be performed in a sequence so that all the natural movements of the spine can benefit, and are not designed for treatment of existing back problems.

Box 7.4 Patient self-help. Prevention: flexion exercise (Chaitow 2004)

Perform daily but not after a meal.

• Sit on the floor with both legs straight out in front of you, toes pointing toward the ceiling. Bend forward as far as is comfortable and grasp one leg with each hand.

• Hold this position for about 30 seconds – approximately four slow deep breathing cycles. You should be aware of a stretch on the back of the legs and the back. Be sure to let your head hang down and relax into the stretch. You should feel no actual pain and there should be no feeling of strain.

• As you release the fourth breath ease yourself a little further down the legs and grasp again. Stay here for a further half minute or so before slowly returning to an upright position, which may need to be assisted by a light supporting push upward by the hands.

• Bend one leg and place the sole of that foot against the inside of the other knee, with the bent knee lying as close to the floor as possible.

• Stretch forward down the straight leg and grasp it with both hands. Hold for 30 seconds as before (while breathing in a similar manner) and then, on an exhalation, stretch further down the leg and hold for a further 30 seconds (while continuing to breathe).

• Slowly return to an upright position and alter the legs so that the straight one is now bent, and the bent one straight. Perform the same sequence as described above.

• Perform the same sequence with which you started, with both legs out straight.

Box 7.5 Patient self-help. Prevention: extension exercises – whole body (Chaitow 2004)

Excessive backward bending of the spine is not desirable and the ‘prevention’ exercises outlined are meant to be performed very gently, without any force or discomfort at all. For some people, the expression ‘no pain no gain’ is taken literally, but this is absolutely not the case where spinal mobilization exercises such as these are concerned. If any pain at all is felt then stop doing the exercise.

Repeat daily after flexion exercise.

• Lie on your side (either side will do) on a carpeted floor with a small cushion to support your head and neck. Your legs should be together, one on top of the other.

• Bend your knees as far as comfortably possible, bringing your heels toward your backside. Now slowly take your legs (still together and still with knees fully flexed) backward of your body as far as you can, without producing pain, so that your back is slightly arched. Your upper arm should rest along your side.

• Now take your head and shoulders backward to increase the backward bending of your spine. Again, this should be done slowly and without pain, although you should be aware of a stretching sensation along the front of your body and some ‘crowding’ in the middle of the back.

• Hold this position for approximately 4 full slow breaths and then hold your breath for about 15 seconds. As you release this try to ease first your legs and then your upper body into a little more backward bending. Hold this final position for about half a minute, breathing slowly and deeply all the while.

• Bring yourself back to a straight sidelying position before turning onto your back and resting. Then move into a seated position (still on the floor) for the rotation exercise.

Box 7.6 Patient self-help. Prevention: rotation exercises – whole body (Chaitow 2004)

It is most important that when performing these exercises no force is used, just take yourself to what is best described as an ‘easy barrier’ and never as far as you can force yourself. The gains that are achieved by slowly pushing the barrier back, as you become more supple, arise over a period of weeks or even months, not days, and at first you may feel a little stiff and achy in newly stretched muscles, especially the day after first performing them. This will soon pass and does not require treatment of any sort.

Repeat daily following the flexion and extension exercises.

• Sit on a carpeted floor with legs outstretched.

• Cross your left leg over your right leg at the knees.

• Bring your right arm across your body and place your right hand over the uppermost leg and wedge it between your crossed knees, so locking the knees in position.

• Your left hand should be taken behind your trunk and placed on the floor about 12–15 cm behind your buttocks with your fingers pointing backwards. This twists your upper body to the left.

• Now turn your shoulders as far to the left as is comfortable, without pain. Then turn your head to look over your left shoulder, as far as possible, again making sure that no pain is being produced, just stretch.

• Stay in this position for five full, slow breaths after which, as you breathe out, turn your shoulders and your head a little further to the left, to their new ‘restriction barriers’.

• Stay in this final position for a further five full, slow breaths before gently unwinding yourself and repeating the whole exercise to the right, reversing all elements of the instructions (i.e cross right leg over left, place left hand between knees, turn to right, etc.).

Ideally, repeat the next exercise twice daily following the flexion and extension exercises and the previous rotation exercise.

• Lie face upward on a carpeted floor with a small pillow or book under your head.

• Flex your knees so that your feet, which should be together, are flat on the floor.

• Keep your shoulders in contact with the floor during the exercise. This is helped by having your arms out to the side slightly, palms upward.

• Carefully allow your knees to fall to the right as far as possible without pain – keeping your shoulders and your lower back in contact with the floor. You should feel a tolerable twisting sensation, but not a pain, in the muscles of the lower and middle parts of the back.

• Hold this position while you breathe deeply and slowly for about 30 seconds, as the weight of your legs ‘drags’ on the rest of your body, which is stationary, so stretching a number of back muscles.

• On an exhalation slowly bring your knees back to the mid-line and then repeat the process, in exactly the same manner, to the left side.

• Repeat the exercise to both right and left one more time, before straightening out and resting for a few seconds.

Box 7.7 Patient self-help. Chair-based exercises for spinal flexibility (Chaitow 2004)

These chair-based exercises are intended to be used when back pain already exists or has recently been experienced. They should only be used if they produce no pain during their performance or if they offer significant relief from current symptoms.

Chair exercise to improve spinal flexion

• Sit in a straight chair (no wheels) so that your feet are about 20 cm apart.

• The palms of your hands should rest on your knees so that the fingers are facing each other.

• Lean forward so that the weight of your upper body is supported by the arms and allow the elbows to bend outward, as your head and chest come forward. Make sure that your head is hanging freely forward.

• Hold the position where you feel the first signs of a stretch in your lower back and breathe in and out slowly and deeply, two or three times.

• On an exhalation ease yourself further forward until you feel a slightly increased, but not painful, stretch in the back and repeat the breathing.

• After a few breaths, ease further forward. Repeat the breathing and keep repeating the pattern until you cannot go further without feeling discomfort.

• When, and if, you can fully bend in this position you should alter the exercise so that, sitting as described above, you are leaning forward, your head between your legs, with the backs of your hands resting on the floor.

• All other aspects of the exercise are the same, with you easing forward and down, bit by bit, staying in each new position for 3–4 breaths, before allowing a little more flexion to take place.

For spinal mobility

• Sit in an upright chair with your feet about 20 cm apart.

• Twist slightly to the right and bend forward as far as comfortably possible, so that your left arm hangs between your legs.

• Make sure your neck is free so that your head hangs down.

• You should feel stretching between the shoulders and in the low back.

• Stay in this position for about 30 seconds (four slow deep breaths).

• On an exhalation, ease your left hand toward your right foot a little more and stay in this position for a further 30 seconds.

• On an exhalation, stop the left hand stretch and now ease your right hand toward the floor, just to the right of your right foot, and hold this position for another 30 seconds.

• Slowly sit up again and turn a little to your left, bend forward so that this time your right arm hangs between your legs.

• Make sure your neck is free so that your head hangs down.

• Once again you should feel stretching between the shoulders and in the low back.

• Stay in this position for about 30 seconds and on an exhalation ease your right hand toward your left foot and stay in this position for another 30 seconds.

• On another exhalation stop this stretch with your right hand and begin to stretch your left hand to the floor, just to the left of your left foot, and hold this position for another 30 seconds.

• Sit up slowly and rest for a minute or so before resuming normal activities or doing the next exercise.

To encourage spinal mobility in all directions

• Sit in an upright (four-legged) chair (no wheels) and lean sideways so that your right hand grasps the back right leg of the chair.

• On an exhalation slowly slide your hand down the leg as far as is comfortable and hold this position, partly supporting yourself with your hand-hold.

• Stay in this position for two or three breaths before sitting up on an exhalation.

• Now ease yourself forward and grasp the front right chair leg with your right hand and repeat the exercise as described above.

• Follow this by holding on to the left front leg and finally the left back leg with your left hand and repeating all the elements as described.

• Make two or three ‘circuits’ of the chair in this way to slowly increase your range of movement.

Abdominal toning exercises

These exercises in Boxes 7.8 and 7.9 are designed to help normalize the abdominal muscles if they are weak, while stretching the low back at the same time. This helps strengthen the abdominal muscles by taking away weakening (inhibiting) influences on them.

Box 7.8 Patient self-help. For abdominal muscle tone (Chaitow 2004)

For low back tightness and abdominal weakness

• Lie on your back on a carpeted floor, with a pillow under your head.

• Bend one knee and hip and hold the knee with both hands. Inhale deeply and as you exhale, draw that knee to the same side shoulder (not your chest), as far is comfortably possible. Repeat this twice more.

• Rest that leg on the floor and perform the same sequence with the other leg.

• Replace this on the floor and now bend both legs, at both the knee and hip, and clasp one knee with each hand.

• Hold the knees comfortably (shoulder width) apart and draw the knees toward your shoulders – not your chest. When you have reached a point where a slight stretch is felt in the low back, inhale deeply and hold the breath and the position for 10 seconds, before slowly releasing the breath and, as you do so, easing the knees a little closer toward your shoulders.

• Repeat the inhalation and held breath sequence, followed by the easing of the knees closer to the shoulders, a further four times (five times altogether).

• After the fifth stretch to the shoulders stay in the final position for about half a minute while breathing deeply and slowly.

• This exercise effectively stretches many of the lower and middle muscles of the back and this helps to restore tone to the abdominal muscles, which the back muscle tightness may have weakened.

For low back and pelvic muscles

• Lie on the floor on your back with a pillow under your head and with your legs straight.

• Keep your low back flat to the floor throughout the exercise.

• As you exhale, draw your right hip upward toward your shoulder – as though you are ‘shrugging’ it (the hip, not the shoulder) – while at the same time stretch your left foot (push the heel away, not the pointed toe) away from you, trying to make the leg longer while making certain that your back stays flat to the floor throughout.

• Hold this position for a few seconds before inhaling again and relaxing both efforts.

• Repeat in the same way on the other side, drawing the left leg (hip) up and stretching the right leg down.

• Repeat the sequence five times altogether on each side.

• This exercise stretches and tones the muscles just above the pelvis and is very useful following a period of inactivity due to back problems.

For abdominal muscles and pelvis

• Lie on your back on a carpeted floor, no pillow, knees bent, arms folded over abdomen.

• Inhale and hold your breath, while at the same time pulling your abdomen in (‘as though you are trying to staple your navel to your spine’).

• Tilt the pelvis by flattening your back to the floor.

• Squeeze your buttocks tightly together and at the same time, lift your hips toward the ceiling a little.

• Hold this combined contraction for a slow count of five before exhaling and relaxing onto the floor for a further cycle of breathing.

To tone upper abdominal muscles

• Lie on the floor with knees bent and arms folded across your chest.

• Push your low back toward the floor and tighten your buttock muscles and as you inhale, raise your head, neck and, if possible, your shoulders from the floor – even if it is only a small amount.

• Hold this for 5 seconds and, as you exhale, relax all tight muscles and lie on the floor for a full cycle of relaxed breathing before repeating.

• Do this up to 10 times to strengthen the upper abdominal muscles.

• When you can do this easily add a variation in which, as you lift yourself from the floor, you ease your right elbow toward your left knee. Hold as above and then relax.

• The next lift should take the left elbow toward the right knee.

• This strengthens the oblique abdominal muscles. Do up to 10 cycles of this exercise daily.

To tone lower abdominal muscles

• Lie on the floor with knees bent and arms lying alongside the body.

• Tighten the lower abdominal muscle to curl your pubic bone (groin area) toward your navel. Avoid tightening your buttock muscles.

• Keep your shoulders, spine and (at this point) pelvis on the floor by just tightening the lower abdominal muscles but without actually raising the pelvis. Breathe in as you tighten.

• Continue breathing in as you hold the contraction for 5 seconds and, as you exhale, slowly relax all tight muscles.

• Do this up to 10 times to strengthen the lower abdominal muscles.

• When you can do this easily, add a variation in which the pelvis curls toward the navel and the buttocks lift from the floor in a slow curling manner. Be sure to use the lower abdominal muscles to create this movement and do not press up with the legs or contract the buttocks instead.

• When this movement is comfortable and easy to do, the procedure can be altered so that (while inhaling) the pelvis curls up to a slow count of 4–5, then is held in a contraction for a slow count of 4–5 while the inhale is held, then slowly uncurled to a slow count of 4–5 while exhaling. This can be repeated 10 times or more to strengthen lower abdominals and buttocks.

‘Dead-bug’ abdominal stabilizer exercise

• Lie on your back and hollow your abdomen by drawing your navel toward your spine.

• When you can hold this position, abdomen drawn in, spine toward the floor, and can keep breathing at the same time, raise both arms into the air and, if possible, also raise your legs into the air (knees can be bent), so that you resemble a ‘dead bug’ lying on its back.

• Hold this for 10–15 seconds and slowly lower your limbs to the floor and relax.

• This tones and increases stamina in the transverse muscles of the abdomen, which help to stabilize the spine. Repeat daily at the end of other abdominal exercises.

Releasing exercise for the low back muscles (‘cat and camel’)

• Warm up the low back muscles first by getting on to all fours, supported by your knees (directly under hips) and hands (directly under shoulders).

• Slowly arch your back toward the ceiling (like a camel), with your head hanging down, and then slowly let your back arch downward, so that it hollows as your head tilts up and back (like a cat).

‘Superman’ pose to give stamina to back and abdominal muscles

• First do the ‘cat and camel’ exercise and then, still on all fours, make your back as straight as possible, with no arch to your neck.

• Raise one leg behind you, knee straight, until the leg is in line with the rest of your body.

• Try to keep your stomach muscles in and back muscles tight throughout and keep your neck level with the rest of the back, so that you are looking at the floor.

• Hold this pose for a few seconds, then lower the leg again, repeating the raising and lowering a few times more.

• When, after a week or so of doing this daily, you can repeat the leg raise 10 times (either leg at first, but each leg eventually), raise one leg as before and also raise the opposite arm and stretch this out straight ahead of you (‘superman’ pose) and hold this for a few seconds.

• If you feel discomfort, stop the pose and repeat the ‘cat and camel’ a few times to stretch the muscles.

• Eventually, by repetition, you should build up enough stamina to hold the pose, with either left leg/right arm or right leg/left arm, and eventually both combinations, for 10 seconds each without strain and your back and abdominal muscles will be able to more efficiently provide automatic support for the spine.

Box 7.9 Patient self-help. Brügger relief position (Lewit 1992)

Brügger (1960) devised a simple postural exercise known as the ‘relief position’ which achieves a reduction of the slumped, rounded back (kyphotic) posture that often results from poor sitting and so eases the stresses which contribute to neck and back pain (see also Box 4.4, p. 108, where this exercise is illustrated).

• Perch on the edge of a chair.

• Place your feet directly below the knees and then separate them slightly and turn them slightly outward, comfortably.

• Roll the pelvis slightly forward to lightly arch the low back

• Ease the sternum forward and upward slightly.

• With your arms hanging at your sides, rotate the arms outward so that the palms face forward.

• Separate the fingers so that the thumbs face backward slightly.

• Remain in this posture as you breathe slowly and deeply into the abdomen, then exhale fully and slowly.

• Repeat the breathing 3–4 times.

• Repeat the process several times each hour if you are sedentary.

Hydrotherapy self-help methods

Water, in its various forms, offers considerable therapeutic effects. Hot, cold, and contrasting thermal therapies can be self-applied in a home care program. See Boxes 7.10-7.14.

Box 7.10 Patient self-help. Cold (‘warming’) compress (Chaitow L 1999)

This is a simple but effective method involving a piece of cold, wet cotton material well wrung out in cold water and then applied to a painful or inflamed area after which it is immediately covered (usually with something woolen) in a way that insulates it. This allows your body heat to warm the cold material. Plastic can be used to prevent the damp from spreading and to insulate the material. The effect is for a reflex stimulus to take place when the cold material first touches the skin, leading to a flushing away of congested blood followed by a return of fresh blood. As the compress slowly warms there is a relaxing effect and a reduction of pain.

This is an ideal method for self-treatment or first aid for any of the following:

• sore throat (compress on the throat from ear to ear and supported over the top of the head)

• backache (ideally the compress should cover the abdomen and the back)

Materials

• A single or double piece of cotton sheeting large enough to cover the area to be treated (double for people with good circulation and vitality, single thickness for people with only moderate circulation and vitality)

• One thickness of woolen or flannel material (toweling will do but is not as effective) larger than the cotton material so that it can cover it completely with no edges protruding

Method

Wring out the cotton material in cold water so that it is damp but not dripping wet. Place this over the painful area and immediately cover it with the woolen or flannel material, and also the plastic material if used, and pin the covering snugly in place. The compress should be firm enough to ensure that no air can get in to cool it but not so tight as to impede circulation. The cold material should rapidly warm and feel comfortable and after few hours it should be dry.

Wash the material before reusing it as it will absorb acid wastes from the body.

Use a compress up to four times daily for at least an hour each time if it is found to be helpful for any of the conditions listed above. Ideally, leave it on overnight.

Box 7.11 Patient self-help. Neutral (body heat) bath (Chaitow L 1999)

Placing yourself in a neutral bath in which your body temperature is the same as that of the water is a profoundly relaxing experience. A neutral bath is useful in all cases of anxiety, for feelings of being ‘stressed’ and for relief of chronic pain.

Method

• Run a bath as full as possible and with the water close to 97°F (36.1°C). The bath has its effect by being as close to body temperature as you can achieve.

• Get into the bath so that the water covers your shoulders and support the back of your head on a towel or sponge.

• A bath thermometer should be in the bath so that you can ensure that the temperature does not drop below 92°F (33.3°C).

• The water can be topped up periodically, but should not exceed the recommended 97°F (36.1°C).

• The duration of the bath should be anything from 30 minutes to an hour; the longer the better for maximum relaxation.

• After the bath, pat yourself dry quickly and get into bed for at least an hour.

Box 7.12 Patient self-help. Ice pack (Chaitow L 1999)

Because of the large amount of heat it needs to absorb as it turns from solid back to liquid, ice can dramatically reduce inflammation and reduce the pain it causes. Ice packs can be used for all sprains and recent injuries and joint swellings (unless pain is aggravated by it). Avoid using ice on the abdomen if there is an acute bladder infection or over the chest if there is asthma and stop its use if cold aggravates the condition.

Method

• Place crushed ice into a towel to a thickness of at least an inch, fold the towel and safety pin it together. To avoid dripping, the ice can also be placed in a plastic ‘zip-close’ bag before applying the towel.

• Place a wool or flannel material over the area to be treated and put the ice pack onto this.

• Cover the ice pack with plastic to hold in any melting water and bandage, tape or safety pin everything in place.

• Leave this on for about 20 minutes and repeat after an hour if helpful.

• Protect surrounding clothing or bedding from melting water.

Box 7.13 Patient self-help. Constitutional hydrotherapy (CH) (Blake E 2006)

CH has a non-specific ‘balancing’ effect, inducing relaxation, reducing chronic pain and promoting healing when it is used daily for some weeks.

Note: Help is required to apply CH

Materials

• A full-sized sheet folded in half or two single sheets

• Two blankets (wool if possible)

• Three bath towels (when folded in half each should be able to reach side to side and from shoulders to hips)

• One hand towel (each should, as a single layer, be the same size as the large towel folded in half)

Method

• Undress and lie face up between the sheets and under the blanket.

• Place two hot folded bath towels (four layers) to cover the trunk, shoulders to hips (towels should be damp, not wet).

• Cover with a sheet and blanket and leave for 5 minutes.

• Return with a single layer (small) hot towel and a single layer cold towel.

• Place ‘new’ hot towel onto top of four layers ‘old’ hot towels and ‘flip’ so that hot towel is on skin and remove old towels. Immediately place cold towel onto new hot towel and flip again so that cold is on the skin, remove single hot towel.

• Cover with a sheet and leave for 10 minutes or until the cold towel warms up.

• Remove previously cold, now warm, towel and turn onto stomach.

Suggestions and notes

• If using a bed take precautions not to get this wet.

• ‘Hot’ water in this context is a temperature high enough to prevent you leaving your hand in it for more than 5 seconds.

• The coldest water from a running tap is adequate for the ‘cold’ towel. On hot days, adding ice to the water in which this towel is wrung out is acceptable if the temperature contrast is acceptable to the patient.

• If the person being treated feels cold after the cold towel is placed, use back massage, foot or hand massage (through the blanket and towel) to warm up.

• There are no contraindications to constitutional hydrotherapy.

Box 7.14 Patient self-help. Foot and ankle injuries: first aid

If you strain, twist or injure your foot or ankle this should receive immediate attention from a suitably trained podiatrist or other appropriate health-care professional. This is important to avoid complications.

Even if you can still move the joints of your feet it is possible that a break has occurred (possibly only a slightly cracked bone or a chip) and walking on this can create other problems. Don’t neglect foot injuries or poorly aligned healing may occur!

If an ankle is sprained there may be serious tissue damage and simply supporting it with a bandage is often not enough; it may require a cast. Follow the RICE protocol outlined below and seek professional advice.

First aid (for before you are able to get professional advice)

Rest. Reduce activity and get off your feet.

Ice. Apply a plastic bag of ice, or ice wrapped in a towel, over the injured area, following a cycle of 15–20 minutes on, 40 minutes off.

Compression. Wrap an Ace bandage around the area, but be careful not to pull it too tight.

Elevation. Place yourself on a bed, couch or chair so that the foot can be supported in an elevated position, higher than your waist, to reduce swelling and pain.

• When walking, wear a soft shoe or slipper that can accommodate any bulky dressing.

• If there is any bleeding, clean the wound well and apply pressure with gauze or a towel, and cover with a clean dressing.

• Don’t break blisters, and if they break, apply a dressing.

• Carefully remove any superficial foreign objects (splinters, glass fragment, etc.) using sterile tweezers. If deep, get professional help.

• If the skin is broken (abrasion) carefully clean and remove foreign material (sand, etc.), cover with an antibiotic ointment and bandage with a sterile dressing.

Do not neglect your feet – they are your foundations and deserve respect and care.

Psychosocial self-help methods

Breathing strategies and other relaxation techniques can be incorporated in a home care program. (Boxes 7.15-7.19). Referral to a psychosocial therapist may also be indicated.

Box 7.15 Patient self-help. Reducing shoulder movement during breathing (Chaitow, Gilbert & Bradley 2002)

Stand in front of a mirror and breathe normally, and notice whether your shoulders rise. If they do, this means that you are stressing these muscles and breathing inefficiently. There is a simple strategy you can use to reduce this tendency.

• An anti-arousal (calming) breathing exercise is described next. Before performing this exercise, it is important to establish a breathing pattern that does not use the shoulder muscles when inhaling.

• Sit in a chair that has arms and place your elbows and forearms fully supported by the chair arms.

• Slowly exhale through pursed lips (‘kiss position’) and then as you start to inhale through your nose, push gently down onto the chair arms, to ‘lock’ the shoulder muscles, preventing them from rising.

• As you slowly exhale again release the downward pressure.

• Repeat the downward pressure each time you inhale at least 10 more times.

• As a substitute for the strategy described above, if there is no armchair available, sit with your hands interlocked, palms upward, on your lap.

• As you inhale lightly but firmly push the pads of your fingers against the backs of the hands and release this pressure when you slowly exhale.

• This reduces the ability of the muscles above the shoulders to contract and will lessen the tendency for the shoulders to rise.

Box 7.16 Patient self-help. Anti-arousal (‘calming’) breathing exercise (Chaitow, Bradley & Gilbert 2002)

There is strong research evidence showing the efficacy of particular patterns of breathing in reducing arousal and anxiety levels, which is of particular importance in chronic pain conditions. (Cappo & Holmes 1984, Readhead 1984).

• Place yourself in a comfortable (ideally seated/reclining) position and exhale fully but slowly through your partially open mouth, lips just barely separated.

• Imagine that a candle flame is about 6 inches from your mouth and exhale (blowing a thin stream of air) gently enough so as to not blow this out.

• As you exhale, count silently to yourself to establish the length of the outbreath. An effective method for counting one second at a time is to say (silently) ‘one hundred, two hundred, three hundred’, etc. Each count then lasts about one second.

• When you have exhaled fully, without causing any sense of strain to yourself in any way, allow the inhalation that follows to be full, free and uncontrolled.

• The complete exhalation which preceded the inhalation will have emptied the lungs and so creates a ‘coiled spring’ that you do not have to control in order to inhale.

• Once again, count to yourself to establish how long your inbreath lasts, which, due to this ‘springiness’, will probably be shorter than the exhale.

• Without pausing to hold the breath, exhale fully, through the mouth, blowing the air in a thin stream (again you should count to yourself at the same speed).

• Continue to repeat the inhalation and the exhalation for not less than 30 cycles of in and out.

• The objective is that in time (some weeks of practicing this daily) you should achieve an inhalation phase that lasts for 2–3 seconds while the exhalation phase lasts from 6–7 seconds, without any strain at all.

• Most importantly, the exhalation should be slow and continuous and you should strictly avoid breathing the air out quickly and then simply waiting until the count reaches 6, 7 or 8 before inhaling again.

• By the time you have completed 15 or so cycles any sense of anxiety that you previously felt should be much reduced. Also if pain is a problem this should also have lessened.

• Apart from always practicing this once or twice daily, it is useful to repeat the exercise for a few minutes (about five cycles of inhalation/exhalation takes a minute) every hour, especially if you are anxious or whenever stress seems to be increasing.

• At the very least it should be practiced on waking and before bedtime and, if at all possible, before meals.

Box 7.17 Patient self-help. Method for alternate nostril breathing (Chaitow, Bradley & Gilbert 2002)

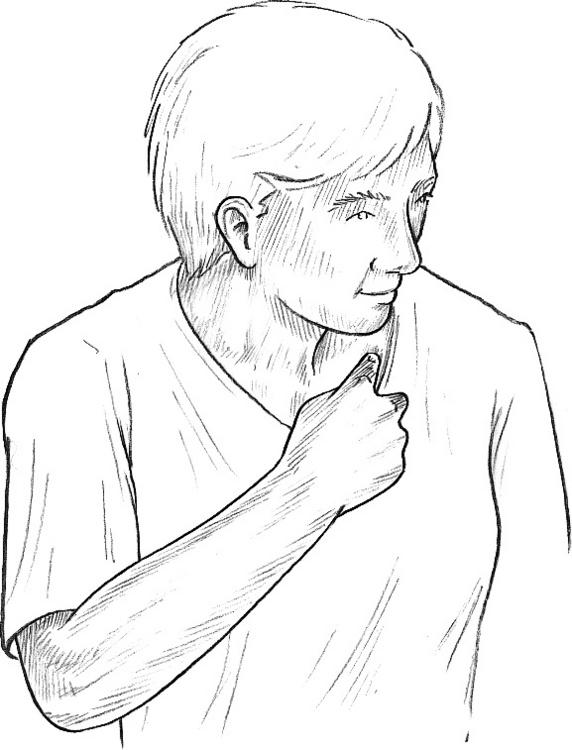

• Place your left ring finger pad onto the side of your right nostril and press just hard enough to close it while at the same time breathing in slowly through your left nostril.

• When you have inhaled fully, use your left thumb to close the left nostril and at the same time remove the pressure of your middle finger and very slowly exhale through the right nostril.

• When fully exhaled, breathe in slowly through the right nostril, keeping the left side closed with your thumb.

• When fully inhaled, release the left side, close down the right side, and breathe out, slowly, through your left nostril.

• Continue to exhale with one side of the nose, inhale again through the same side, then exhale and inhale with the other side, repeatedly, for several minutes.

Box 7.18 Patient self-help. Autogenic training (AT) relaxation (Chaitow 1996)

Every day, ideally twice a day, for 10 minutes at a time, do the following.

• Lie on the floor or bed in a comfortable position, small cushion under the head, knees bent if that makes the back feel easier, eyes closed. Do the yoga breathing exercise described above for five cycles (one cycle equals an inhalation and an exhalation) then let breathing resume its normal rhythm.

• When you feel calm and still, focus attention on your right hand/arm and silently say to yourself ‘my right arm (or hand) feels heavy’. Try to see/sense the arm relaxed and heavy, its weight sinking into the surface it is resting on as you ‘let it go’. Feel its weight. Over a period of about a minute repeat the affirmation as to its heaviness several times and try to stay focused on its weight and heaviness.

• You will almost certainly lose focus as your attention wanders from time to time. This is part of the training in the exercise – to stay focused – so when you realize your mind has wandered, avoid feeling angry or judgmental of yourself and just return your attention to the arm and its heaviness.

• You may or may not be able to sense the heaviness – it doesn’t matter too much at first. If you do, stay with it and enjoy the sense of release, of letting go, that comes with it.

• Next, focus on your left hand/arm and do exactly the same thing for about a minute.

• Move to the left leg and then the right leg, for about a minute each, with the same messages and focused attention.

• Go back to your right hand/arm and this time affirm a message that tells you that you sense a greater degree of warmth there. ‘My hand is feeling warm (or hot).’

• After a minute or so, turn your attention to the left hand/arm, the left leg and then finally the right leg, each time with the ‘warming’ message and focused attention. If warmth is sensed, stay with it for a while and feel it spread. Enjoy it.

• Finally focus on your forehead and affirm that it feels cool and refreshed. Stay with this cool and calm thought for a minute before completing the exercise. By repeating the whole exercise at least once a day (10–15 minutes is all it will take) you will gradually find you can stay focused on each region and sensation. ‘Heaviness’ represents what you feel when muscles relax and ‘warmth’ is what you feel when your circulation to an area is increased, while ‘coolness’ is the opposite, a reduction in circulation for a short while, usually followed by an increase due to the overall relaxation of the muscles. Measurable changes occur in circulation and temperature in the regions being focused on during these training sessions and the benefits of this technique to people with Raynaud’s phenomenon and to anyone with pain problems are proven by years of research. Success requires persistence – daily use for at least 6 weeks – before benefits are noticed, notably a sense of relaxation and better sleep.

Box 7.19 Patient self-help. Progressive muscular relaxation (Chaitow 1996)

• Wearing loose clothing, lie with arms and legs outstretched.

• Clench one fist. Hold for 10 seconds.

• Release your fist, relax for 10–20 seconds and then repeat exactly as before.

• Do the same with the other hand (twice).

• Draw the toes of one foot toward the knee. Hold for 10 seconds and relax.

• Repeat and then do same with the other foot.

• Perform the same sequence in five other sites (one side of your body and then the other, making 10 more muscles) such as:

• After one week combine muscle groups:

• After another week abandon the ‘tightening up’ part of the exercise – simply lie and focus on different regions, noting whether they are tense. Instruct them to relax if they are.

• There are no contraindications to these relaxation exercises.

The following exercise has a relaxing and balancing effect and simultaneously encourages a more efficient circulation to the brain, ideal for anyone with feelings of ‘brain fog’.

How to use AT for health enhancement (Box 7.18)

• If there is pain or discomfort related to muscle tension, AT training can be used to focus on the area and, by getting that area to ‘feel’ heavy, this will reduce tension.

• If there is pain related to poor circulation the ‘warmth’ instruction can be used to improve it.

• If there is inflammation related to pain this can be reduced by ‘thinking’ the area ‘cool’.

• The skills gained by AT can be used to focus on any area and, most importantly, help you to stay focused and to introduce other images – ‘seeing’ in the mind’s eye a stiff joint easing and moving or a congested swollen area melting back to normality or any other helpful change that would ease whatever health problem there might be.

CAUTION: AT trainers strongly urge that you avoid AT focus on vital functions, such as those relating to the heart or the breathing pattern, unless a trained instructor is providing guidance and supervision.

Biochemical self-help methods

Anti-inflammatory nutritional (biochemical) strategies: patient’s guidelines

Inflammation is often a part of the healing process of an area; however, it can at times be excessive and require modifying (rather than completely ‘turning it off’).

Minute chemical substances which your body makes, called prostaglandins and leukotrienes, take part in inflammatory processes and these depend to a great extent upon the presence of arachidonic acid, which we manufacture mainly from animal fats.

This means that reducing animal fat in your diet reduces levels of enzymes that help to produce arachidonic acid and, therefore, cuts down the levels of the inflammatory substances released in tissues that contribute so greatly to pain.

The first priority in an antiinflammatory diet is to cut down or eliminate dairy fat.

• Fat-free or low-fat milk, yogurt and cheese should be eaten in preference to full-fat varieties and butter avoided altogether.

• Meat fat should be completely avoided, and since much fat in meat is invisible, meat itself can be left out of the diet for a time (or permanently). Poultry skin should be avoided.

• Hidden fats in products such as biscuits and other manufactured foods should be looked for on packages and avoided.

Some fish, mainly those that come from cold water areas such as the North Sea and Alaska, contain high levels of eicosapentenoic acid (EPA), which helps reduce inflammation. Fish oil has these antiinflammatory effects without interfering with the useful jobs which some prostaglandins do, such as protection of delicate stomach lining and maintaining the correct level of blood clotting (unlike some antiinflammatory drugs). Research has shown that the use of EPA in rheumatic and arthritic conditions offers relief from swelling, stiffness and pain, although benefits do not usually become evident before 3 months of fish oil supplementation, reaching their most effective level after around 6 months.

If you want to follow this strategy (avoid this if you are allergic to fish):

• eat fish such as herring, sardine, salmon and mackerel (but not fried) at least twice weekly, and more if you wish

• take EPA capsules (10–15 daily) when inflammation is at its worst until relief appears and then a maintenance dose of six capsules daily (Also see page 143, Chapter 6).

Dietary strategies to help food intolerances or allergies

An exclusion diet (Boxes 7.20 and 7.21) may help to uncover suspect foods and reduce muscle and joint pain associated with food intolerances.

Box 7.20 Patient self-help. Exclusion diet (Drisko et al 2006)

In order to identify foods that might be tested to see whether they are aggravating your symptoms, make notes of the answers to the following questions.

1. List any foods or drinks that you know disagree with you or which produce allergic reactions (skin blotches, palpitations, feelings of exhaustion, agitation, or other symptoms).

7. Read the following list of foods and highlight in one color any that you eat at least every day and in another color those that you eat three or more times a week: bread (and other wheat products); milk; potato; tomato; fish; cane sugar or its products; breakfast cereal (grain mix, such as muesli or granola); sausages or preserved meat; cheese; coffee; rice; pork; peanuts; corn or its products; margarine; beetroot or beet sugar; tea; yogurt; soya products; beef; chicken; alcoholic drinks; cake; biscuits; oranges or other citrus fruits; eggs; chocolate; lamb; artificial sweeteners; soft drinks; pasta.

To test by ‘exclusion’, choose the foods that appear most often on your list (in questions 1–6 and the ones highlighted in the first color, as being eaten at least once daily).

• Decide which foods on your list are the ones you eat most often (say, bread) and test wheat, and possibly other grains, by excluding these from your diet for at least 3–4 weeks (wheat, barley, rye, oats and millet).

• You may not feel any benefit from this exclusion (if wheat or other grains have been causing allergic reactions) for at least a week and you may even feel worse for that first week (caused by withdrawal symptoms).

• If after a week your symptoms (muscle or joint ache or pain, fatigue, palpitations, skin reactions, breathing difficulty, feelings of anxiety, etc.) are improving, you should maintain the exclusion for several weeks before reintroducing the excluded foods – to challenge your body – to see whether symptoms return. If the symptoms do return after you have resumed eating the excluded food and you feel as you did before the exclusion period, you will have shown that your body is better, for the time being at least, without the food you have identified.

• Remove this food from your diet (in this case, grains – or wheat if that is the only grain you tested) for at least 6 months before testing it again. By then you may have become desensitized to it and may be able to tolerate it again.

• If nothing was proven by the wheat/grain exclusion, similar elimination periods on a diet free of dairy produce, fish, citrus, soya products, etc. can also be attempted, using your questionnaire results to guide you and always choosing the next most frequently listed food (or food family).

This method is often effective. Wheat products, for example, are among the most common irritants in muscle and joint pain problems. A range of wheat-free foods are now available from health stores, which makes such elimination far easier.

Box 7.21 Patient self-help. Oligoantigenic diet (Heine 2006)

To try a modified oligoantigenic exclusion diet, evaluate the effect of excluding the foods listed below for 3–4 weeks.

Vegetables

None are forbidden but people with bowel problems should avoid beans, lentils, Brussels sprouts and cabbage

Dairy

Allowed: none (substitute with rice milk)

Forbidden: cow’s milk and all its products including yogurt, butter, most margarine, all goat, sheep and soya milk products, eggs

Drinks

Allowed: herbal teas such as camomile and peppermint, spring, bottled or distilled water

Forbidden: tea, coffee, fruit squashes, citrus drinks, apple juice, alcohol, tap water, carbonated drinks

Forbidden: all yeast products, chocolate, preservatives, all food additives, herbs, spices, honey, sugar of any sort

• If benefits are felt after this exclusion, a gradual introduction of one food at a time, leaving at least 4 days between each reintroduction, will allow you to identify those foods which should be left out altogether – if symptoms reappear when they are reintroduced.

• If a reaction occurs (symptoms return, having eased or vanished during the 3–4 week exclusion trial), the offending food is eliminated for at least 6 months and a 5-day period of no new reintroductions is followed (to clear the body of all traces of the offending food), after which testing (challenge) can start again, one food at a time, involving anything you have previously been eating, which was eliminated on the oligoantigenic diet.

Åsenlöf P., Denison E., Lindberg P. Long-term follow-up of tailored behavioural treatment and exercise based physical therapy in persistent musculoskeletal pain: a randomized controlled trial in primary care. Eur J Pain. 2009;13(10):1080-1088.

Blake E. Constitutional Hydrotherapy. Portland Oregon: Holistic Publications; 2006.

Bradley L. Cognitive therapy for chronic pain. In: Gatchel R., Turk D., editors. Psychological approaches to pain management. New York: Guilford Press, 1996.

Bradley D. Hyperventilation syndrome/breathing pattern disorders. London: Kyle Cathie, 1998. Hunter House, San Francisco

Brugger A. Pseudoradikulare syndrome. Acta Rheumatologica. 1960;18:1.

Bucklew S. Self efficacy and pain behaviour among subjects with fibromyalgia. Pain. 1994;59:377-384.

Burckhardt C. Randomized controlled clinical trial of education and physical training for women with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1994;21(4):714-720.

Cappo B., Holmes D. Utility of prolonged respiratory exhalation for reducing physiological and psychological arousal in non-threatening and threatening situations. J Psychosom Res. 1984;28:265-273.

Chaitow L., Bradley D., Gilbert C. Multidisciplinary approaches to breathing pattern disorders. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

Chaitow L. Positional Release Techniques, 2nd Edition. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2007.

Chaitow L. Positional Release Techniques, 3rd Edition. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2007.

Chaitow L. Maintaining Body Balance, Flexibility and Stability. Edinburg: Churchill Livingstone; 2004.

Chaitow L. Hydrotherapy: Water Treatment for Health & Beauty. London: Thorsons/HarperCollins; 1999.

Chaitow L. Stress: Proven Stress-Coping Strategies. London: Thorsons/HarperCollins; 1996.

Drisko J., Bischoff B., Hall M., McCallum R. Treating irritable bowel syndrome with a food elimination diet followed by food challenge and probiotics. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006;25(6):514-522.

Gil K., Ross S., Keefe F. Behavioural treatment of chronic pain: four pain management protocols. In: France R., Krishnan K., editors. Chronic pain. Washington: American Psychiatric Press; 1988:317-413.

Gilbert C. Self-regulation of breathing. In: Chaitow L., editor. Multidisciplinary approaches to breathing pattern disorders. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

Heine R. Gastroesophageal reflux disease, colic and constipation in infants with food allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;6(3):220-225.

Howard D., Gosling C. A short questionnaire to identify patient characteristics indicating improved compliance to exercise rehabilitation programs: A pilot investigation. International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine. 2008;11(1):7-15.

Keefe F., Beaupre P., Gil K. Group therapy for patients with chronic pain. In: Gatchel R., Turk D., editors. Psychological approaches to pain management. New York: Guilford Press, 1996.

Kendall N., Linton S., Main C. Guide to assessing psychosocial yellow flags in acute low back pain: risk factors for long-term disability and work loss. Wellington, NZ: Accident Rehabilitation and Compensation Insurance Corporation of New Zealand and the National Health Committee, 1997. Available from http://www.nhc.govt.nz

Lederman E. Fundamentals of manual therapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1997.

Lewit K. Manipulative therapy in rehabilitation of the locomotor system. London: Butterworths, 1992.

Lewthwaite R. Motivational considerations in physical therapy involvement. Phys Ther. 1990;70(12):808-819.

Liebenson C., editor. Rehabilitation of the spine. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1996.

Liebenson C., editor. Rehabilitation of the spine: a practitioner’s manual, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007.

Liebenson C. Self help series. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2001;5(4):264-270.

Martin A. An exercise program in treatment of fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1996;23(6):1050-1053.

Prochaska J., Marcus B. The transtheoretical model: applications to exercise. In: Dishman R., editor. Advances in exercise adherence. New York: Human Kinetics; 1994:161-180.

Readhead C. Enhanced adaptive behavioural response through breathing retraining. Lancet. 22 September, 1984:665-668.

Richardson C., Jull G. Muscle control-pain control. What exercises would you prescribe? Man Ther. 1995;1(1):2-10.

Vlaeyen J., Teeken-Gruben N., Goossens M., et al. Cognitive-educational treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized clinical trial. I. Clinical effects. J Rheumatol. 1996;23(7):1237-1245.

Waddell G. The back pain revolution. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1998.

Waddell G., Feder G., McIntosh A., et al. Low back pain: evidence review. London: Royal College of General Practitioners, 1996.

Wigers S., Stiles T., Vogel P. Effects of aerobic exercise versus stress management treatment in fibromyalgia: a 4.5 year prospective study. Scand J Rheumatol. 1996;25:77-86.