Erythroderma

Definition

Erythroderma or generalized exfoliative dermatitis defines any inflammatory dermatosis that involves all or nearly all the skin surface (sometimes stated as more than 90%). It is a secondary process and represents the generalized spread of a dermatosis or systemic disease throughout the skin.

Pathology

The duration and severity of the inflammatory process play a greater part in determining the histology than the underlying cause. In the acute eruption, oedema of the epidermis and dermis is prominent, and there is an inflammatory infiltrate. More chronic lesions show lengthened rete ridges and thickening of the epidermis. Abnormal lymphocytes may eventually be apparent in those cases resulting from lymphoma, and specific changes identified on biopsy of a typical lesion when psoriasis, ichthyosiform erythroderma or pityriasis rubra pilaris is the cause.

Clinical presentation

Erythroderma is an uncommon but important dermatological emergency, as the systemic effects are potentially fatal.

General symptoms and signs

Some features are common to all patients with erythroderma, no matter what the cause. It is twice as common in men and mainly affects the middle-aged and elderly. The condition often develops suddenly, particularly when associated with leukaemia or an eczema. A patchy erythema may rapidly spread to be universal within 12–48 h and be accompanied by pyrexia, malaise and shivering. Scaling appears 2–6 days later and, at this stage, the skin is hot, red, dry and obviously thickened. The patient experiences irritation and tightness of the skin and feels cold. The exfoliation of scales may be copious and continuous. Scalp and body hair is lost when erythroderma has been present for some weeks. The nails become thickened and may be shed. Pigmentary changes occur and, in those with a dark skin, hypopigmentation is seen. The picture is influenced by the patient’s general condition and the underlying cause. The commonest causes of erythroderma are eczema, psoriasis and lymphoma (Table 1). Other dermatoses, including drug eruptions and pityriasis rubra pilaris, may also be implicated. Multiple skin biopsies may help in diagnosis.

Table 1 Causes of erythroderma and their relative frequencies

| Cause | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Eczema (contact/atopic/seborrhoeic/unclassified) | 40 |

| Psoriasis | 25 |

| Lymphoma/leukaemia/Sézary syndrome | 15 |

| Drug eruption | 10 |

| Pityriasis rubra pilaris/ichthyosiform erythroderma | 1 |

| Other skin disease | 1 |

| Unknown | 8 |

Eczema

Atopic eczema may become erythrodermic at any age. Erythroderma from eczema is most common in the elderly, in whom the eczema may be unclassified. Itch is often intense.

Psoriasis

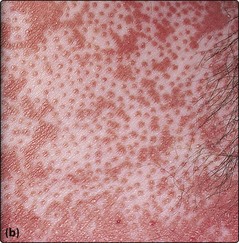

At first, the eruption resembles conventional psoriasis but, when the exfoliative stage is reached, these specific features are lost (Fig. 1). The withdrawal of potent topical steroids or of systemic steroids, or an intercurrent drug eruption, can precipitate erythrodermic psoriasis. Sterile pinhead-sized pustules sometimes develop, and the condition may progress to generalized pustular psoriasis (p. 29).

Lymphoma/Sézary syndrome

Early biopsies may not be specific, and this may delay diagnosis, although universal erythroderma, infiltration of the skin and severe pruritus are helpful pointers (p. 89). Lymphadenopathy is often prominent, but the nodes are not always involved by lymphoma. Sézary syndrome (Fig. 2) typically occurs in elderly males and is characterized by the presence of abnormal T lymphocytes with large convoluted nuclei (Sézary cells) in the blood and skin. Patients may be stable for a number of years, then deteriorate rapidly.

Drug eruption

An acute drug eruption (p. 86), often of the drug hypersensitivity syndrome type, may become erythrodermic (Fig. 3). Carbamazepine, phenytoin, diltiazem, cimetidine, gold, allopurinol and sulphonamides are the commonest culprits.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a disorder of unknown aetiology that begins in adults with redness and scaling of the scalp and progresses to cover the limbs and trunk (Fig. 4). It is a follicle-based eruption and characteristically shows islands of sparing and a yellow keratotic thickening of the palms (Fig. 5). Treatment with acitretin may be considered. Clearance occurs spontaneously in 1–3 years. A relapsing childhood type is reported.

Other dermatoses

Ichthyosiform erythroderma is a type of inherited ichthyosis (p. 90) that is present from birth or early infancy. Acute graft-versus-host disease and, very occasionally, severe scabies or extensive pemphigus can cause erythroderma.

In about 10% of cases of erythroderma, no cause is found. The possibility of a latent lymphoma must be considered.

Complications

Erythroderma is associated with profound physiological and metabolic changes (Table 2). Cardiac failure and hypothermia are risks, especially in the elderly, and cutaneous or respiratory infection may also occur. Oedema is almost invariable and cannot be regarded as a sign of heart failure. The pulse rate is always increased. Cardiac failure and infection are difficult to diagnose. Blood cultures are easily contaminated with skin microflora. Lymphadenopathy is common and does not necessarily signify lymphoma. In the pre-steroid era, erythroderma was fatal in one-third of cases, largely due to cardiac failure or infection.

Table 2 Pathophysiology of erythroderma

| Clinical complication | Pathophysiology |

|---|---|

| Cardiac failure | Increased skin blood flowIncreased plasma volume |

| Cutaneous oedema | Increased capillary permeabilityIncreased plasma volumeHypoalbuminaemia |

| Hypoalbuminaemia | Increased plasma volumeReduced albumin synthesis, increased metabolismProtein loss in scaling |

| Dehydration | Increased transepidermal water lossIncreased capillary permeability |

| Impaired temperature regulation | Excess heat lossFailure to sweat |

| Dermatopathic lymphadenopathy | Cutaneous inflammation and infection |

Management

Inpatient treatment and skilled nursing care are mandatory. The patient is nursed in a comfortably warm room at a steady temperature (preferably 30–32°C), and the pulse, blood pressure, temperature and fluid balance are regularly monitored. A pressure-relieving mattress is sometimes used. Soothing emollient creams and mild to moderate topical steroids are a mainstay of local treatment and are often adequate. Systemic steroids are life-saving in severe cases. The maintenance of normal haemodynamics, attention to electrolyte equilibrium and adequate nutritional support (particularly with regard to minimizing protein losses) are vital for severely ill patients. Cardiac failure and intercurrent infections are treated as necessary.

Erythroderma

A rare but potentially fatal eruption, often of sudden onset, showing near-universal skin involvement.

A rare but potentially fatal eruption, often of sudden onset, showing near-universal skin involvement.

Commonest causes: eczema, psoriasis, lymphoma and drug eruption.

Commonest causes: eczema, psoriasis, lymphoma and drug eruption.

Characterized by hot, red, oedematous, dry and exfoliating skin.

Characterized by hot, red, oedematous, dry and exfoliating skin.

Complications include cardiac failure, hypothermia, infection and lymphadenopathy.

Complications include cardiac failure, hypothermia, infection and lymphadenopathy.

Inpatient management and close supervision are required.

Inpatient management and close supervision are required.

Treatment consists initially of bland emollients and topical steroids. Systemic steroids and full supportive therapy may be needed in life-threatening cases.

Treatment consists initially of bland emollients and topical steroids. Systemic steroids and full supportive therapy may be needed in life-threatening cases.