Associations with malignancy

Internal malignancy causes a variety of skin changes (Table 1). Apart from direct infiltration, the mechanisms of these effects are often poorly understood. Some genetic conditions associated with malignancy include characteristic skin lesions that may arise before or after the cancer (e.g. mucosal lentigines in Peutz–Jeghers syndrome associated with bowel malignancy).

Table 1 Cutaneous manifestations of malignancy

| Condition associated | Commonest malignancies |

|---|---|

| Almost always | |

| Acanthosis nigricans | Gastrointestinal tract |

| Erythema gyratum repens | Lung, breast |

| Extramammary Paget’s disease | Apocrine glands |

| Necrolytic migratory erythema | Pancreas (alpha cells) |

| Paget’s disease of the nipple | Breast |

| Skin secondaries | Breast, gastrointestinal, ovary, lung, kidney |

| Occasionally | |

| Acquired ichthyosis | Lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) |

| Dermatomyositis | Lung, breast, stomach |

| Erythroderma | T cell lymphoma |

| Flushing | Carcinoid syndrome |

| Generalized pruritus | Hodgkin’s disease, polycythaemia rubra vera |

| Hyperpigmentation | Cachectic malignancy |

| Hypertrichosis | Various tumours |

| Migratory thrombophlebitis | Pancreas, lung, stomach |

| Paraneoplastic pemphigus | B cell lymphoma, thymoma |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | Leukaemia, myeloma |

| Tylosis | Oesophagus |

Conditions associated with malignancy

The following rare skin eruptions are characteristic and strongly indicate an underlying malignancy:

Acanthosis nigricans

True acanthosis nigricans is uncommon. The flexures and neck typically show epidermal thickening and pigmentation (Fig. 1), and the skin is velvety or papillomatous. Warty lesions are seen around the mouth and on the palms and soles. Benign acquired acanthosis nigricans is more frequent and describes similar milder changes, seen with obesity or endocrine disorders such as insulin-resistant diabetes or acromegaly. Very rarely, acanthosis nigricans is inherited and appears in childhood or at puberty. In the malignancy-associated type, usually found in a middle-aged or elderly patient, the cancer is most commonly of the gastrointestinal tract. Growth factors, released from the tumour or associated with the endocrine disorder, cause the skin changes. The underlying disease must be identified and treated.

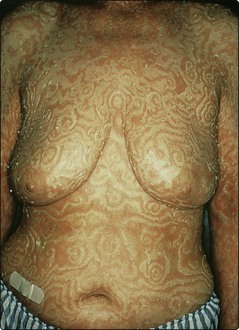

Erythema gyratum repens

Erythema gyratum repens is an exceptionally rare pattern of concentric scaly rings of erythema that shift visibly from day to day (Fig. 2). The appearance resembles wood grain. An underlying neoplasm, frequently a carcinoma of the lung, is almost invariably detected.

Necrolytic migratory erythema

Necrolytic migratory erythema is a rare paraneoplastic eruption of serpiginous erythematous plaques, with a migratory eroded edge. It typically starts in the perineum. The eruption indicates a tumour, or occasionally a hyperplasia, of the glucagon-secreting alpha cells of the pancreas (a glucagonoma). Weight loss, anaemia, mild diabetes, diarrhoea and glossitis are associated. Liver metastases are often present at diagnosis.

Paget’s disease and extramammary Paget’s disease

Paget’s disease presents as a unilateral eczema-like plaque of the nipple areola and represents the intraepidermal spread of an intraductal breast carcinoma. Extramammary Paget’s disease is seen as an eczema-like eruption around the perineum or axilla. It usually results from intraepidermal spread of a ductal apocrine carcinoma. A skin biopsy confirms the diagnosis prior to surgical excision.

Secondary deposits

Cutaneous metastases are not uncommon. They occur late, indicate a poor prognosis and may be the presenting sign of an internal tumour. Skin secondaries are multiple or solitary and appear as firm asymptomatic pink nodules (Fig. 3). The scalp, umbilicus and upper trunk are favoured sites. They occur most commonly with tumours of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, ovary and lung, and with malignant melanoma (p. 102). Leukaemias and lymphomas often show skin involvement (p. 104). Direct infiltration of the skin causing sclerosis – carcinoma en cuirasse – is sometimes found with carcinoma of the breast (Fig. 4). Peau d’orange appearance and carcinoma erysipeloides (well demarcated red patch) and telangiectatic cutaneous metastases patterns are also recognized.

Conditions occasionally associated with malignancy

Conditions occasionally associated with underlying neoplasia but also seen with benign disease include:

dermatomyositis (p. 81)

dermatomyositis (p. 81)

erythroderma (p. 44)

erythroderma (p. 44)

flushing (p. 70)

flushing (p. 70)

hypertrichosis (p. 67)

hypertrichosis (p. 67)

tylosis (keratoderma; p. 90).

tylosis (keratoderma; p. 90).

Acquired ichthyosis

Ichthyosis is usually inherited and starts in infancy (p. 90), but it may be acquired in adult life due to an underlying malignancy (e.g. Hodgkin’s disease), essential fatty acid deficiency (e.g. caused by intestinal bypass malabsorption) or drug therapy with nicotinic acid, allopurinol and clofazimine.

Generalized pruritus

Generalized pruritus not associated with an eruption has several causes:

idiopathic (‘senile’): see page 118

idiopathic (‘senile’): see page 118

Patients with generalized pruritus need careful examination and investigation to exclude liver disease (e.g. biliary obstruction), iron deficiency, polycythaemia, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism and renal failure. Pruritus may occur with multiple sclerosis and neurofibromatosis. Sometimes, especially in the elderly, no cause is found, and the itching is labelled idiopathic. The commonest malignant causes of pruritus are Hodgkin’s disease (one-third of patients with this disease itch) and polycythaemia rubra vera. The aetiology of the itching is poorly understood. Treatment, once any underlying disorder has been dealt with, is symptomatic. Sedative antihistamines, calamine lotion and topical antipruritics (e.g. 0.5% menthol in aqueous cream) are used.

Hyperpigmentation

Malignancy-associated pigmentation may result from ectopic adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) or melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH)-like hormone production by the tumour. It is also seen in patients with malignant cachexia. The axillae, groins and nipples are involved.

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum starts as a pustule or inflamed nodule, which breaks down to produce an ulcer with an undermined purplish margin and a surrounding erythema (Fig. 5). The ulcer may extend rapidly. Lesions may be multiple. A bacterial gangrene (e.g. necrotizing fasciitis, p. 48) is sometimes misdiagnosed. Pyoderma gangrenosum often occurs on the trunk or lower limbs. An immune-mediated process is suggested. The following diseases are associated:

ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease

ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease

chronic autoimmune liver disease

chronic autoimmune liver disease

Behçet’s syndrome (p. 121)

Behçet’s syndrome (p. 121)

Treatment is with systemic steroids, ciclosporin or anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) monoclonal antibodies. Minocycline helps mild disease. Cases associated with bowel disease can improve as this is controlled.

Superficial thrombophlebitis

Migratory superficial thrombophlebitis, mainly associated with carcinoma of the pancreas or lung, also occurs with Behçet’s syndrome.

Associations with malignancy

Acanthosis nigricans, characterized by pigmentation and epidermal thickening of the flexures, neck, palms and soles, is seen with gastrointestinal cancers.

Acanthosis nigricans, characterized by pigmentation and epidermal thickening of the flexures, neck, palms and soles, is seen with gastrointestinal cancers.

Benign acanthosis nigricans is more common and occurs with obesity or endocrine disorders.

Benign acanthosis nigricans is more common and occurs with obesity or endocrine disorders.

Erythema gyratum repens is a migratory erythema almost invariably associated with a neoplasm.

Erythema gyratum repens is a migratory erythema almost invariably associated with a neoplasm.

Paget’s disease, an eczema-like plaque at the nipple, is due to epidermal spread of an intraductal carcinoma. The extramammary form comes from an apocrine carcinoma.

Paget’s disease, an eczema-like plaque at the nipple, is due to epidermal spread of an intraductal carcinoma. The extramammary form comes from an apocrine carcinoma.

Secondary deposits are not uncommon and may present as single or multiple pink firm nodules, often on the scalp or upper trunk. They occur with tumours of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, ovary and lung and with malignant melanoma.

Secondary deposits are not uncommon and may present as single or multiple pink firm nodules, often on the scalp or upper trunk. They occur with tumours of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, ovary and lung and with malignant melanoma.

Acquired ichthyosis is associated with Hodgkin’s disease, fatty acid deficiency (e.g. intestinal bypass malabsorption) and as a side-effect of some drugs.

Acquired ichthyosis is associated with Hodgkin’s disease, fatty acid deficiency (e.g. intestinal bypass malabsorption) and as a side-effect of some drugs.

Generalized pruritus may occur with malignancy (e.g. Hodgkin’s disease), liver disease, renal failure, iron deficiency and thyroid dysfunction.

Generalized pruritus may occur with malignancy (e.g. Hodgkin’s disease), liver disease, renal failure, iron deficiency and thyroid dysfunction.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a necrotic ulceration seen with ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple myeloma or leukaemia.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a necrotic ulceration seen with ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple myeloma or leukaemia.