Disorders of hair

Hair loss (alopecia)

The division of alopecia into diffuse, localized and scarring or non-scarring helps in diagnosis (Table 1).

| Type of hair loss | Causes |

|---|---|

| Diffuse non-scarring | Male pattern/female pattern, hypothyroid, hypopituitary, hypoadrenal, drug induced, iron deficiency, telogen and anagen effluvium, diffuse alopecia areata |

| Localized/non-scarring | Alopecia areata, ringworm, traumatic, hair pulling, traction, secondary syphilis |

| Localized/diffuse scarring | Burns, radiation, shingles, kerion, tertiary syphilis, lupus erythematosus, morphoea, pseudopelade, lichen planus |

Diffuse non-scarring

With diffuse non-scarring alopecia, patients usually notice excessive numbers of hairs on the pillow, brush or comb, and after washing their hair. The scalp shows a diffuse reduction in hair density. The causes are described below.

Male and female patterns (androgenetic alopecia)

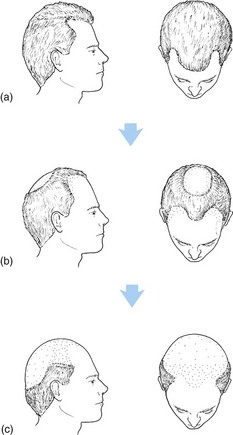

Male pattern baldness is inherited (the exact mode is unclear) and androgen dependent. Over several cycles, the androgen-sensitive follicles miniaturize from terminal to vellus hairs. Males are affected from the second decade and, by the seventh decade, 80% have involvement. Patterned balding also occurs in females, the majority of whom are hormonally normal. It becomes more pronounced after the menopause and is present in 70% of 80-year-old women. In men, bitemporal recession followed by a bald crown is the usual pattern (Fig. 1); women may show this but more commonly exhibit a diffuse thinning. Mostly, no treatment is required but, if indicated, topical minoxidil (Regaine) produces some response in a third of cases, and finasteride can help.

Endocrine and nutrition related

Endocrine disorders often present with hair loss. Underactivity of the thyroid, pituitary or adrenals can cause diffuse alopecia, as may hyperthyroidism. Androgen-secreting tumours in women produce male pattern baldness with virilization. Malnutrition induces dry brittle hair that becomes pale or red in kwashiorkor (protein deficiency). Diffuse hair loss is also seen with iron or zinc deficiency.

Localized non-scarring

Patchy hair loss results from a variety of causes, as described below.

Alopecia areata

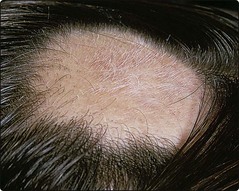

Alopecia areata is a common condition, associated with autoimmune disorders, in which anagen is prematurely arrested. It generally starts in the second or third decade and presents with sharply defined non-inflamed bald patches on the scalp. Pathognomonic exclamation mark hairs, which taper as they approach the scalp, are seen. The eyebrows and beard can also be affected, and nails may show pitting.

The course is unpredictable: bald patches may enlarge progressively but, for a first attack, regrowth (often initially with white hairs) is usual (Fig. 2). Prepubertal onset, extensive involvement (especially of the posterior scalp) and atopy signal a poor prognosis. Complete scalp alopecia (totalis) or loss of all bodily hair (universalis) is seen occasionally. Rarely, diffuse scalp alopecia occurs.

Treatment depends on the extent: if localized, spontaneous regrowth is probable, and intralesional steroid (e.g. triamcinolone acetonide) may accelerate this. If extensive, therapy is less successful. Contact immunotherapy by the application of the sensitizer diphencyprone is effective but not widely available. Wigs are often necessary.

Localized/diffuse scarring alopecia

In scarring (cicatricial) alopecia, hair follicles are destroyed. This condition can result from the following:

Burns or irradiation. Chemical or thermal burns will scar the scalp, as may X-irradiation, which was used in the past to induce epilation in the treatment of scalp ringworm.

Burns or irradiation. Chemical or thermal burns will scar the scalp, as may X-irradiation, which was used in the past to induce epilation in the treatment of scalp ringworm.

Infection. Shingles of the first trigeminal dermatome (p. 54), kerion (see below) and tertiary syphilis may leave a scarred scalp.

Infection. Shingles of the first trigeminal dermatome (p. 54), kerion (see below) and tertiary syphilis may leave a scarred scalp.

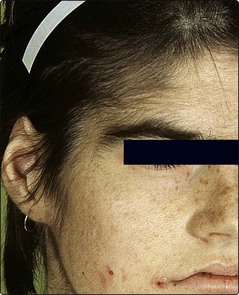

Lichen planus/lupus erythematosus. Scarring alopecia of the scalp is seen, with erythema, scaling and follicular changes (Fig. 3). Lesions may exist elsewhere. Topical or intralesional steroids or systemic therapies are prescribed. Female frontal fibrosing alopecia may be a lichen planus variant.

Lichen planus/lupus erythematosus. Scarring alopecia of the scalp is seen, with erythema, scaling and follicular changes (Fig. 3). Lesions may exist elsewhere. Topical or intralesional steroids or systemic therapies are prescribed. Female frontal fibrosing alopecia may be a lichen planus variant.

Pseudopelade. Pseudopelade describes a scarring alopecia, the end stage of an idiopathic or unidentified destructive inflammatory process in the scalp.

Pseudopelade. Pseudopelade describes a scarring alopecia, the end stage of an idiopathic or unidentified destructive inflammatory process in the scalp.

Excess hair (hirsutism and hypertrichosis)

Hirsutism is the growth of terminal hair in a male pattern in a female. It is is quite common and presents with hair growth in the beard area, around the nipples and in the male pubic pattern. It frequently causes a lot of anxiety, even if mild. Hirsutism in many women is racial or idiopathic (Table 2) but some will have the polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in which there may be associated acne, raised blood androgens, irregular periods and ovarian cysts on ultrasound. Few cases are due to an androgen-secreting tumour, although it is important to identify virilizing features such as cliteromegaly, male pattern baldness and a deep voice that might indicate this. In hirsutism, endocrine investigations are usually indicated. Hypertrichosis is less common and is defined as excessive terminal hair growth in a non-androgenic distribution, in which fine terminal hair appears on the face, limbs and trunk (Fig. 4). It is mostly drug induced (Table 3).

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Pituitary | Acromegaly |

| Adrenal | Cushing syndrome, virilizing tumours, congenital adrenal hyperplasia |

| Ovarian | Polycystic ovaries, virilizing tumours |

| Iatrogenic | Androgens, progestogens |

| Idiopathic | End-organ hypersensitivity to androgens |

Table 3 Causes of hypertrichosis

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Localized | Melanocytic naevi, faun tail (associated with spina bifida occulta), chronic scarring or inflammation |

| Generalized | Malnutrition in children, anorexia nervosa, porphyria cutanea tarda, underlying malignancy, drugs, e.g. minoxidil, phenytoin, ciclosporin |

Treatment of hirsutism is often unsatisfactory. Electrolysis is time consuming for large areas. Waxing, shaving and bleaching are other approaches. Laser hair removal is widely available. Treatment with an antiandrogen (cyproterone acetate), usually with ethinylestradiol, is occasionally effective. Eflornithine cream helps facial hair. PCOS can be treated with metformin and spironolactone. Hypertrichosis requires investigation to find the underlying cause.

Other disorders

Hair shaft defects are rare, usually inherited, conditions of the hair shaft (e.g. monilethrix) that result in broken hairs that are brittle, beaded and look abnormal.

Dandruff is an exaggerated physiological exfoliation of fine scales from an otherwise normal scalp. More severe forms merge with seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp (p. 38). Psoriasis (p. 31) produces scaling and may give localized alopecia.

Tinea capitis usually affects children. Common causative organisms and recommended treatments are shown on page 58. Anthropophilic species cause defined scaly areas with slight inflammation and alopecia with broken hair shafts. Zoophilic infection with Trichophyton verrucosum produces an inflamed boggy, pustular swelling known as a kerion (p. 114). Scarring may result. Infection with T. schoenleinii causes favus – a chronic crusted scarring alopecia.

Common hair disorders

Male pattern baldness: the commonest cause of hair loss; if treatment is required, topical minoxidil or oral finasteride may help.

Male pattern baldness: the commonest cause of hair loss; if treatment is required, topical minoxidil or oral finasteride may help.

Alopecia areata: common; discrete bald patches may show exclamation mark (!) hairs. Early cases recover spontaneously.

Alopecia areata: common; discrete bald patches may show exclamation mark (!) hairs. Early cases recover spontaneously.

Scarring alopecia: needs investigation to establish the underlying cause.

Scarring alopecia: needs investigation to establish the underlying cause.

Hirsutism: may be due to polycystic ovary disease. Endocrine investigations are indicated. Androgen-secreting virilizing tumors are uncommon.

Hirsutism: may be due to polycystic ovary disease. Endocrine investigations are indicated. Androgen-secreting virilizing tumors are uncommon.