CHAPTER 5 Cross-Cultural Practice

The world is my country, all mankind are my brethren, and to do good is my religion.

A dental hygienist related an experience that occurred in Liberia, a country in western Africa.1 A Liberian girl was brought to a clinic by her family for oral care. The child’s oral and systemic health were poor. Surprisingly, the dental hygienist’s oral hygiene recommendations (i.e., cleaning the teeth, gums, and tongue with a toothbrush, sponge, or gauze) were met with refusal. The young girl’s family believed that she was cursed and that any items placed in her mouth would become a danger to family members who might touch them. Even the dental hygienist’s suggestion to bury the used gauze was unacceptable because the ground would also become cursed. The family wanted the dental hygienist to cure the girl—that is, to eliminate the curse. Within the cultural context, the only acceptable dental hygiene intervention was for the girl to use her own finger to clean her mouth. The family graciously accepted several bottles of a commercial antimicrobial mouth rinse, as if these bottles contained a magical potion.

This story highlights the importance of cross-cultural dental hygiene practice. As the nations of the world become more racially and ethnically diverse and as peoples from different cultures come into closer and more frequent contact, dental hygienists must be equipped with cross-cultural competence, the ability to integrate current knowledge of oral healthcare with the customs of multiple cultures.

CROSS-CULTURAL DENTAL HYGIENE

Culture, or the characteristics and beliefs of a particular social, ethnic, or age group, plays an integral role in dental hygiene care because an individual’s opinion of oral health, wellness, and disease are culturally determined. This means that one’s perception of what is healthy or unhealthy is dependent on the conceptions of health in one’s culture. Conceptual differences often exist between the client and the healthcare provider from different cultures. For example, using a poultice on an abscessed tooth, although acceptable in some cultures, is viewed as being ineffective by oral care professionals in Western countries.

Cross-cultural dental hygiene is the effective integration of diverse cultural backgrounds of clients into the process of care. Cross-cultural dental hygiene recognizes and encompasses the social, political, ethnic, religious, and economic realities that shape the experiences and environments of clients. Cultural diversity is evident in different societal rules, languages, foods, dress, daily cultural practices, motivational factors, beliefs, values, and health behaviors. These factors influence human need fulfillment of the client and must be recognized and integrated into professional care if preventive and therapeutic goals are to be achieved.

Concepts in Cross-Cultural Dental Hygiene

Consideration of individual value systems and lifestyles should be an integral part of delivering high-quality dental hygiene care. A firm understanding of the conceptual frameworks that underlie modern dental hygiene practice and the vocabulary of cross-cultural dental hygiene is essential for the delivery of high-quality care in any setting.

Human Needs and Humanism

Humans have basic needs that transcend all cultures. These include the need for subsistence, safety, identity, love, and freedom. Many human needs have been codified as “rights” in documents such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The human needs theory is a framework of human needs adapted to the dental hygiene process. Whether physiologic or psychologic, human needs are universally shared, so the human needs model can be used to address the unmet needs of clients from different cultural backgrounds. See Chapter 2 for a more complete discussion of the human needs model.

Evidence-based dental hygiene care is predicated on the philosophies of humanism and holism. Humanism recognizes the right of all humans to have their needs satisfied and “attests to the dignity and worth of all individuals through concern for and understanding of their network of attitudes, values, behavior patterns, and way of life.”2 Humanism is not a universally embraced principle. Many governments and cultures value country, religion, dictators, pride, political power, or family over individual human rights.

Holism

Holism refers to the idea that an individual is more than the sum of parts. Holistic practitioners show concern for and interest in all dimensions of the individual.2 Holism asserts that a person is composed of emotional, physical, mental, and spiritual elements that cannot be explained by reducing that individual down to component parts (Box 5-1). Holism also emphasizes that individuals bring uniqueness in race, culture, ethnicity, attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, and experience, and that all of these factors interact to constitute the “whole” individual. Cultural background can determine the extent to which a practitioner or client subscribes to the philosophy of holism. Applied to healthcare, the holistic philosophy has particular relevance. If applied, its tenets make the care setting a welcome place for individuals who might otherwise feel disconnected or disenfranchised. A comparison of Western and non-Western views of the individual (Table 5-1) provides some insight into how culture can influence attitudes and behaviors.

BOX 5-1 Characteristics and Beliefs Inherent to Holistic Healthcare

Adapted from Ferguson M: The Aquarian conspiracy: personal and social transformation in the 1980s, Los Angeles, 1980, Putnam.

TABLE 5-1 Comparison of Western and Non-Western Views of the Individual, Society, Health, and Disease

| Western Values | Non-Western Values |

|---|---|

| Freedom of choice | Group decision making |

| Uniqueness of the individual | Group commonality |

| Independence | Compliance |

| Interdependence | Harmony |

| Competition | Cooperation |

| Nonconformity | Conformity |

| Expression of feelings | Control of one’s feelings |

| Fulfillment of individual needs | Fulfillment of the needs of the group |

| Body is divided into organ systems with identifiable functions; dichotomous body and mind | Body is viewed as a union of flesh and soul |

| Body is viewed objectively and is relatively immune to nonsomatic influences | Disease occurs as a result of disharmony or an imbalance of life forces |

From Ho D: Psychological implications of collectivism: with special references to the Chinese case and Maoist dialects. In Eckensberber L, Lonner W, Poortinga Y, eds: Cross-cultural contributions to psychology, Amsterdam, 1979, Swets and Zeitlinger.

Race and Ethnicity

Race is the classification of human beings based on physical characteristics such as skin color, stature, eye color, hair color and texture, facial characteristics, and general body characteristics, all of which are hereditary. The standard classifications of race—such as white (Caucasian), Hispanic, black (African origin), or Pacific Islander—are limiting, as many individuals might self-identify as belonging to multiple, overlapping categories. The categoric groupings of race are useful but are ultimately socially constructed and arbitrary. Modern genetics reveals that there are actually more similarities than differences among the racial groups.

Ethnicity refers to the unique cultural and social heritage and traditions of minority groups within the primary racial divisions that reflect distinct customs, language, diet, work habits, religious beliefs, and methods of dealing with illness and death. People who share similarities in heritage and tradition, passed on from generation to generation, are said to be members of the same ethnic group. Ethnic groups share common factors, which may include language, dialect, nationality, music, folklore, food preferences, geographic location, religion, and a sense of uniqueness. Examples of ethnic groups include Japanese, Italian, Polish, Haitian, Kuwaiti, Pakistani, and Hispanic, just to name a few.

Religious beliefs constitute an important component of ethnicity. Religion is one’s belief in a supernatural power and what one must do to have a positive relationship with that power. Religious beliefs shape values, ethics, morals, and behaviors. Some religious beliefs influence health beliefs and practices. For example, some religions, such as orthodox Judaism or Islam, teach practices related to personal hygiene and cleanliness, eating habits, dressing habits, and food preparation requirements (Table 5-2).

TABLE 5-2 Guide to Working with People of Various Religious Groups∗

| Religious Group | Basic Beliefs and Concepts | Healthcare Practices and Beliefs |

|---|---|---|

| Christian Scientists | ||

| Eastern Orthodox | ||

| Evangelists | Healing occurs by God in only some situations; God heals all through different people, modalities, and techniques | |

| Jews | ||

| Mormons (similar to conservative Protestants) | ||

| Native American Church or Peyotists (Native Americans) | ||

| Pentecostalism (composed of Evangelists and Fundamentalists) | Concerned with holiness (state of mind and spiritual purity), literal interpretation of the Bible, and renewal of Pentecostal experiences, e.g., speaking in tongues | Divine healing, prophecy, and working miracles |

| Spiritualism (Hispanics, Africans, African Americans, Native Americans) | ||

| Protestantism | Four principles of Protestantism lend themselves to faith healing as well as modern Western medicine | |

| Islam (some people from Middle East, Northern Africa, Pakistan, India, Bosnia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Micronesia) |

∗ Religion affects healthcare practices, beliefs, and interactions with healthcare providers. It is important to remember that not all people from a given religious group will act in a standard manner. Great variability exists within cultural groups based on socioeconomic status, level of education, and overall life experiences. This chart is not meant to be generalized to all people within a specific religion, but rather to serve as a beginning guide.

Culture and Subculture

Culture is “the sum total of human behavior or social characteristics peculiar to a specific group and passed from generation to generation or from one to another within the group.”2 Culture includes the rules of behavior each person learns to adapt successfully to life within a particular group. Culture includes beliefs, values, traditions, experiences, customs, rituals, and language.

People may be from the same culture but be members of different subcultures. Although individuals within the same culture may share commonalities in lifestyles and basic beliefs, vast differences may exist between individuals from different subcultures, especially in attitudes, interests, goals, and dialects. “A subculture is formed by a group of persons who have developed interests or goals different from the primary culture, based on such things as occupation (Hollywood culture), sexual orientation (gay culture), age (youth culture), social class (middle class), or religion (fundamentalism).”2 Dental hygienists can be viewed as members of a subculture (dental hygiene) with unique philosophical attitudes, practices, beliefs, and values. Within American society we are familiar with the culture of poverty, the drug culture, Yuppie culture, Generation X, and street people (culture of homelessness). Members of subcultures have lifestyles, behaviors, and manners of speaking that make them different from the general population. Some would consider these traits to be unusual, different, or deviant from the predominant culture.

Many overlapping subcultures may be used to classify various diverse individuals within one predominant culture. For example, there may be people from the Polish ethnic group who are Catholic or Jewish, with subcultures that span several socioeconomic levels to gay culture, the drug culture, or the culture of poverty. There are people of African descent who are fundamentalist Christians or fundamentalist Muslims from Mogadishu, Somalia, or Detroit, Michigan, who represent various socioeconomic groups.

Stereotyping and Ethnocentrism

Stereotyping is the erroneous behavior of assuming that a person possesses certain characteristics or traits simply because he or she is a member of a particular group. Stereotyping fails to recognize the uniqueness of the individual and prevents accurate and unbiased perception of those who are different. Stereotyping clouds perceptions and makes dental hygienists less effective as professionals and human beings. Although stereotyping can provide a comfortable foundation for an individual in a strange environment with new people, an accurate assessment should always be made of another human being without the bias inherent to stereotyping.

Taking the time to learn about people rather than relying on popular generalizations is an important step toward eliminating stereotypic thinking. Learning about other cultures, languages, customs, foods, religions, and practices also enables the dental hygienist to interact successfully with culturally diverse people as individuals with unique human needs. Getting in touch with one’s own cultural base and realizing one’s own cultural biases are important if improvement is to occur in intercultural communication and interaction. Periodically, it is good to participate in self-assessment to monitor stereotypic thinking. One can observe strangers and develop personal assumptions about the way they look, dress, behave, or speak. Once strangers become acquaintances and acquaintances become friends, initial assumptions can then be compared with the realities of who these people are and what they are truly like.

Believing that one’s culture is superior to that of others is ethnocentrism. People who are ethnocentric use their own cultures as the “gold standard” against which people from other cultures are judged. Ethnocentric behavior is characterized as judgmental, condescending, insulting, and narrow-minded. Dental hygienists who are ethnocentric may belittle clients whose oral health practices may be rooted in culture rather than research evidence. These dental hygienists may convey the feeling that their way is the right way and that the client is ignorant or uneducated.

It is easy to fall prey to ethnocentrism if we are blind to the prejudices, conscious or subconscious, in our own thinking and behavior. Ethnocentrism makes it difficult for healthcare providers to care for clients who are different from them. It contributes to discrimination, poor-quality healthcare delivery, dentally underserved populations, and loss of clients.

Melting Pot and Salad Bowl Social Concepts

In the past many sociologists advanced the proposition that people of different cultures in the United States assimilated into the mainstream white Anglo-Saxon Protestant culture. The idea of the “melting pot” suggests that people relinquish their previous cultural identity in favor of the predominant culture of the society in which they find themselves. Such intermingling of cultural diversity was thought to result in a blended culture with liberty, equality, and justice for everyone.

The melting pot theory has given way to the “salad bowl” approach to explaining cultural assimilation. Modern sociologists prefer to use the salad bowl metaphor because it recognizes cultural diversity as a separate and unique component that remains heterogeneous within society. As it relates to health, the salad bowl model recognizes that culture influences the health status, beliefs, and behaviors of individuals and that healthcare providers and managers must be prepared to accommodate these differences. Treatment, educational programs, and client-provider interactions must be culturally appropriate. Some work settings proactively encourage cultural awareness through employee-training programs that identify cultural biases and facilitate positive attitudes and behaviors such as valuing diversity and team building.

CULTURAL BARRIERS TO ORAL HEALTHCARE

Culture influences how each individual conceptualizes and manifests human need, motivation, health promotion, and oral disease and healthcare. The dental hygienist may be at a disadvantage when the client is from a different racial, religious, or ethnic group, speaks a different language, or is of a different socioeconomic status. Cultural differences may create barriers to communication, decrease trust, and raise anxiety levels for both dental hygienist and client. Dental hygienists who incorporate cultural perspectives into practice heighten their effectiveness by breaking down barriers to excellent oral health and healthcare.

Race and Ethnicity as Barriers to Healthcare

Currently, over 25% of the population in the United States belongs to a racial minority or is of mixed race (Table 5-3).3 According to recent demographic trends, about 50% of the U.S. population is expected to be Asian, Black, Hispanic, Native American or Pacific Islander, or a combination of two or more races by 2050.4 Non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans, and Alaskan Natives have the poorest oral and general health of any of the racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Strategies for improving the health status of racial and ethnic minorities are prominent features of Healthy People 2010, the goal-setting health agenda developed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.5 Because of changing demographics, dental hygienists must understand local cultures and culturally influenced healthcare practices to communicate with, educate, and motivate people from diverse racial and ethnic groups so that they can achieve optimal health.

TABLE 5-3 Diversity of the Population of the United States, 20064

| Population | Percent | Total Number |

|---|---|---|

| Total population | 100.0 | 299,398,485 |

| White | 73.9 | 221,331,507 |

| Black or African American | 12.4 | 37,051,483 |

| Asian | 4.4 | 13,100,095 |

| Native American∗ | 0.8 | 2,369,431 |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander | 0.1 | 426,194 |

| Other race | 6.4 | 19,007,129 |

| Two or more races | 2.0 | 6,112,646 |

∗ Defined as “American Indian and Alaskan Native” by the 2006 American Community Survey.

Non-Western Medical Philosophy

Although most Western therapies are based on research evidence, the vast majority of the world populations are non-Western. Depending on his or her cultural values, the client may feel good, bad, or indifferent to the products and procedures used in Western-based dental hygiene practice. Likewise, a dental hygienist may fail to recognize the client’s cultural frame of reference and erroneously label the client as difficult, unmotivated, uncooperative, noncommunicative, or noncompliant. Healthcare practices from Western medicine may be viewed as functional or dysfunctional depending on the cultural system of origin. For example, the practice of putting a loved one in a nursing home may be viewed by some cultures as ensuring the best possible care on a 24-hour basis, but other cultures might perceive this practice as irresponsible, insensitive, or inhumane.

A dental hygienist’s lack of familiarity with non-Western medical philosophies and traditions can create a barrier to effective care and communication. Dental hygienists may know how to assess clients clinically but may not know how to interpret the client’s behaviors or concerns because of cultural differences. For example, a Muslim client’s refusal to have his teeth polished and treated with topical fluoride on a day of fasting may be erroneously interpreted as a lack of interest in professional care. A client’s food preferences may result in an erroneous dental hygiene diagnosis of a need for a biologically sound and functional dentition. Multicultural clients may have different cultural definitions of human attractiveness, some of which may be misdiagnosed as a need for a more wholesome facial image. Dental hygienists who do not recognize the reason or purpose behind a client’s home remedy or product preference may incorrectly assume that the remedy or product causes harm and should unequivocally be discontinued. Oral health therapy and promotion strategies, including the planning of interventions and the implementation of the care plan, must be delivered in relation to the cultural environment of the client. Although not a comprehensive list, Table 5-4 provides some basic guidelines for working with people from various cultural groups, including many with non-Western medical philosophies.

TABLE 5-4 Guide to Working with People of Various Cultural Groups∗

∗ It is important to remember that not all people from a given culture will act in a standard manner. Great variability exists within cultural groups based on socioeconomic status, level of education, and overall life experiences. This chart is not meant to be generalized to all people within a specific culture, but rather to serve as a beginning guide.

Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic status is defined by a person’s income, occupation, and level of education. Socioeconomic status permeates every aspect of a person’s life. It affects where one lives, how one spends money, what one chooses to eat, how one uses free time, where one receives healthcare, how one pays for that healthcare, and, ultimately, one’s general and oral health status.

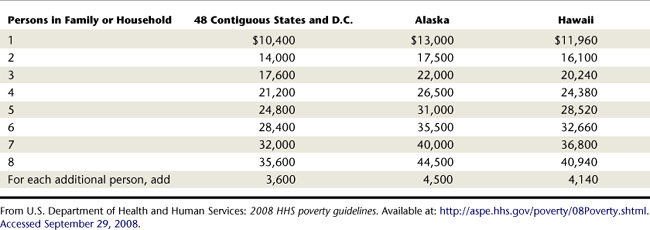

Poverty is universal, but its definition is culturally determined. Poverty is relative based on the standards prevailing in the community (Figure 5-1). Poverty in one community might be regarded as wealth in another. The U.S. Bureau of the Census reported that in 2006 36.5 million persons, or 12.3% of the U.S. population, were living below the official government poverty level as defined by financial income and household size.6 This poverty definition is from the U.S. Office of Management and Budget and consists of a set of income thresholds that vary by family size and composition. Families or individuals with income below the predefined poverty threshold are classified as living below the poverty line (Table 5-5).

The burden of poverty in the United States is disproportionately distributed among racial minorities, women, and children under 18 years of age. Blacks and Hispanics are overrepresented in the segment of the population classified as poor. In 2006, 24.3% of all blacks and 20.6% of all Hispanics were living in poverty, compared with 8.2% of non-Hispanic whites. In addition, the average woman earned only 77% of the average man’s earnings. The unequal burden of poverty that falls on women is often referred to as the “feminization of poverty.” Factors contributing to the feminization of poverty include lower real median income than men, teenage pregnancy, pregnancy out of marriage, divorce, abandonment, and female longevity. Children under 18 had the highest rate of poverty (17.6%) out of any age group.6

Poverty is a key predictor of poor oral health. Children with the most advanced oral disease are found within minority, poor, homeless, and migrant populations and populations with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.7 Poverty is a culture, and as a culture it is often passed on from generation to generation. This can be observed in people on welfare rolls, the urban and rural poor, and migrant workers who may become trapped in an ongoing cycle of poverty. Persons living in poverty are at high risk for or are more likely to manifest the following:

Because these characteristics tend to cluster in the population living in poverty, a scenario is created in which those who can least “afford” to be sick and who have the worst access to healthcare are in fact the sickest. In other words, the unemployed and poor, who have the highest burden of oral disease and may need the most care, cannot access it. According to Healthy People 2010, poor people get sick more often, experience greater complications with their illnesses, take longer to recover, and are less likely to regain their previous level of functioning, as compared with people from higher-income groups. Individuals in poverty do not readily take advantage of preventive health services, nor do they perceive the long-term benefits of these services.5

One barrier to taking advantage of preventive healthcare services such as routine dental hygiene care may include insufficient or nonexistent medical insurance. In the United States, low socioeconomic status is correlated with the likelihood of having inadequate health insurance coverage. In households earning $75,000 per year or more, the uninsured rate is 8.5%, whereas the rate is nearly 25% in households earning less than $25,000.6 Those eligible for government-funded healthcare (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid, SCHIPS) may find that oral care is not covered or that healthcare providers are unwilling to accept them as clients.

Although access to medical care is important, poverty itself may be a more powerful determinant of health status. Canada’s experience with making healthcare accessible to all people presents an interesting model of the effects of poverty on health. In 1968 Canada initiated a national health insurance program to provide healthcare to people without regard to financial resources, age, ethnic origin, or creed. More than three decades later, health remains directly related to people’s economic status.

Poverty continues to be a major barrier to healthcare that prevents individuals from meeting their basic human need for general and oral health. Low health expectations within the culture of poverty may result in a fatalistic attitude (e.g., “No matter what I do, I’ll lose my teeth anyway”; “My mother and father have false teeth and so will I”). Those living in poverty are also more likely to have low healthcare literacy. Healthcare literacy is the ability to understand the healthcare system and how it works. Other barriers to healthcare are disenfranchisement, lack of transportation, homelessness, seasonal work, prejudice, low literacy, daily dress that clearly distinguishes a person from the mainstream culture, inadequate levels of education, and a lack of healthcare personnel from the individual’s own culture. Given these barriers, it is easier to understand why some people resort to self-therapy, home or herbal remedies, or the services of a folk or faith healer, all of which are more accessible, less expensive, and more familiar than the modern healthcare system.

Impoverished environments directly influence the health status of residents. Low-income communities are more likely to be in close proximity to dump sites and hazardous waste facilities compared with high-income communities. Low-income housing is usually associated with poor maintenance, inadequate light and ventilation, insufficient access to utilities such as heat, water, and electricity, crowded living conditions, infestation, and lead poisoning. People who experience inadequate, high-density housing are also at higher risk to experience crime, physical and emotional abuse, stress, psychologic problems, alienation, and transmission of infectious diseases.

Wealth and Its Relationship to Health

Wealth is usually associated with high levels of education, prestige, self-esteem, power, and internal locus of control. Because the wealthy are more likely to be currently or to ever have been employed, they benefit from healthcare insurance, which in the United States is primarily a third-party payment system, to finance large portions of their healthcare needs. Because the wealthy are more likely to be earning income, they are also more likely to able to afford clean, comfortable housing, recreational activities, healthy diets, and, of course, access to healthcare. Because of their higher levels of education, financially secure individuals are less intimidated by the healthcare system than poorer individuals. On average, they verbalize their concerns, assert their needs, determine their level of participation in care, seek second opinions, and are more often critical healthcare consumers than their less-wealthy counterparts. On average, people in the upper socioeconomic levels of society live longer and experience less disability than do those from low-income groups.5

Development Status and Access to Care

Access to high-quality care is often, but not always, related to the development status of a country. Nations of the world are grouped according to economic development as follows:

Developed countries are economically and industrially developed states that are characterized by relatively high standards of living, literacy rates, life expectancy rates, and income per person. Examples of developed countries include Australia, Canada, Great Britain, Germany, South Korea, Switzerland, and the United States.

Developed countries are economically and industrially developed states that are characterized by relatively high standards of living, literacy rates, life expectancy rates, and income per person. Examples of developed countries include Australia, Canada, Great Britain, Germany, South Korea, Switzerland, and the United States. Developing countries are the poorer nations of the world, compared with the developed countries, that lack well-developed economies and have lower standards of living, lower literacy rates, and score lower on the Human Development Index. Some developing countries include Afghanistan, Guatemala, Haiti, Lesotho, Somalia, and Yemen. The United Nation’s Millennium Development Goals were adopted to improve the standard of living in developing countries.

Developing countries are the poorer nations of the world, compared with the developed countries, that lack well-developed economies and have lower standards of living, lower literacy rates, and score lower on the Human Development Index. Some developing countries include Afghanistan, Guatemala, Haiti, Lesotho, Somalia, and Yemen. The United Nation’s Millennium Development Goals were adopted to improve the standard of living in developing countries.Ensuring access to high-quality healthcare is a major challenge for all countries, but it is especially difficult in developing countries because of weak health infrastructure (Figure 5-2). Health infrastructure refers to the supporting framework of a health system, which includes everything from the physical hospitals and clinic buildings to healthcare administration and financing systems. Because a health infrastructure is expensive to create and maintain, many developing countries have limited formal healthcare systems and must rely substantially on home remedies and traditional healers.

COMMUNICATING IN A CROSS-CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT

For a dental hygienist to provide high-quality care to clients of different cultural backgrounds, effective intercultural communication must take place. Effective intercultural communication means that each person involved in the transaction is able to understand the other from his or her unique cultural perspective. Ineffective communication can convey a lack of sensitivity on the part of the dental hygienist to a client’s cultural needs, preferences, and beliefs. Such miscommunication often creates barriers that can weaken the client-provider relationship.

Communication between people from different cultures is a complex task. A dental hygienist initiates communication by exhibiting a positive and empathetic attitude while attempting to establish some initial areas of commonality (e.g., parenthood, children, marriage, food and travel experiences). Customs, beliefs, and practices indigenous to various cultural groups can be found under Website Information and Resources. Knowledge from these and similar sites can enhance competence in cross-cultural communication.

Verbal Communication

People who speak different languages perceive the world differently. A healthcare provider’s ability to effectively communicate with culturally diverse people facilitates care. Language can portray an individual’s identity, mindset, and values. European languages, including English, denote the individual as a private, singular entity who has importance. This is exemplified by the pronoun “I.” In some Asian and African cultures, the group identity takes priority over the self (Figure 5-3). In Japanese the first-person pronoun is expressed differently, depending on the situation (e.g., gender of speaker and person being addressed, private or public) and whether the language is written or oral.

Language systems that are different should not be viewed as deficient. In fact, dental hygienists who are native English-speakers should know that individuals with a native language other than English may have difficulty comprehending and communicating with them because of the following characteristics of standard English:

Variations also exist in the ways members of diverse cultures typically think, prioritize, and communicate. One manifestation of this difference in thinking is how various cultures may place different values on time.

Polychronic is a term to describe individuals who do many things at the same time, who are repetitive in their speech, and who place a low value on time. Some African, Arab, and Asian cultures are polychronic. Individuals from polychronic traditions may not orient themselves to Western time standards (clock time) but instead abide by time standards in nature. Other clients may be consistently late for appointments because they are less time-oriented. A dental hygienist insensitive to the time orientation of such cultures may erroneously attribute this action to a low value placed on oral health or to anxiety about obtaining dental hygiene care. Dental hygiene interventions that require action on the part of the client at specific time intervals may be difficult for individuals from polychronic cultures.

Polychronic is a term to describe individuals who do many things at the same time, who are repetitive in their speech, and who place a low value on time. Some African, Arab, and Asian cultures are polychronic. Individuals from polychronic traditions may not orient themselves to Western time standards (clock time) but instead abide by time standards in nature. Other clients may be consistently late for appointments because they are less time-oriented. A dental hygienist insensitive to the time orientation of such cultures may erroneously attribute this action to a low value placed on oral health or to anxiety about obtaining dental hygiene care. Dental hygiene interventions that require action on the part of the client at specific time intervals may be difficult for individuals from polychronic cultures.Manner of Speaking

Intensity of style and expression varies among different groups. According to Western culture, an emotional speaker is viewed as persuasive, self-assured, and tough-minded. A calm, objective speaker is seen as trustworthy and honest. In contrast, many Asian cultures respect silence and are hesitant toward spontaneity. In many non-Western cultures, a younger speaker must show respect when speaking to elders. Older clients from these non-Western traditions may feel disrespected if a younger dental hygienist speaks brusquely or dominantly. Culturally sensitive dental hygienists intentionally modify their manner of speaking to facilitate positive interactions.

Nonverbal Communication

Culture is important in determining the meaning and interpretation of nonverbal communication. Various ethnic groups possess culturally acceptable gestures, etiquette, eye contact, physical contact, and methods of effective listening.

Gesticulation

Gesticulations are nonverbal signals such as facial expressions and head, hand, or body movements that communicate emotions. Facial expressions are universal and can be used to communicate with or deceive other people, depending on the context. Culturally, a smile can mean very different things. For example, a smile may indicate cordiality, embarrassment, or happiness.

There is cultural variability, however, in the rules for displaying gestures. In most parts of the world, shaking the head from left to right means “no”; but tossing the head to the side means “no” to some Arabs and in parts of Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, and Bosnia-Herzegovina. South Asians may point with their chins and employ a side-to-side head bobble to signify “yes.” A slap on the back might denote friendliness among Anglo-Saxon whites but is considered insulting to Asians. The sign for hitchhiking in America is vulgar when used in Australia. In Botswana, a quick side-to-side motion of the hand as if waving, with the palm toward the signaler means “I don’t have or want anything.”

Zones of Territory

Each culture defines appropriate distances, or personal spaces, that are maintained between people in various situations. In other words, custom determines intimate, personal, social, and public distances or space kept between people. Depending on the culture, the appropriate zone of territory may be based on the degree of respect, authority, and friendship between the individuals communicating. Because human territoriality is culturally influenced, a dental hygienist interested in making clients comfortable during healthcare encounters must do so with cultural sensitivity in mind.

Religious beliefs may also affect a person’s zone of comfort. Muslims may refuse healthcare from a provider who is not of the same gender because being alone with a member of the opposite sex is considered to be improper for both cultural and religious reasons. Some followers of Islam cannot shake hands, study, or work in close proximity with persons from the opposite gender. When persons invade the prescribed territory, clients may communicate their discomfort through their hesitant behavior and actively attempt to readjust to more comfortable territory.

In the role of educator and clinician, dental hygienists invade the spatial zones of clients. This spatial closeness can be uncomfortable for people of any culture. In general, people from less densely populated areas require larger zones of territory than those from urban areas. Americans tend to readjust their zones during interactions with people from countries that accept closer contact. A dental hygienist must consider the client’s culturally determined need for territoriality, explain procedures, and alert the client to necessary close encounters.

Eye Contact

Culture dictates the appropriate amount of eye contact. In many countries, staring or continuously looking at another person is considered rude. Lack of eye contact may be interpreted as disinterest in Western cultures but as polite behavior in some East Asian countries. Indirect eye contact is acceptable and preferable within Muslim and Native American cultures. When working with clients of diverse cultural backgrounds, the dental hygienist should be cognizant of eye contact because it may be interpreted as disrespect (Figure 5-4).

Physical Contact

Dental hygiene care requires physical contact with the client. In the clinical setting, touch can be divided into necessary touch, such as intraoral examination, and nonnecessary touch, such as touching a client’s arm when explaining an intervention. Nonnecessary touch can convey feelings such as empathy, closeness, and comfort.8 When done appropriately, this type of touch can relieve tension and anxiety while instilling confidence and courage.

However, cultural background, age, and gender affect how touch is interpreted. Physical contact is acceptable when greeting members of the same gender in Asian, Arab, Latin American, and Mediterranean countries. In East Asian cultures, touching an older person is a sign of disrespect unless the older person initiates the physical contact. Other notable examples of culturally influenced physical contact include the custom of Iranian, Pakistani, and Jordanian men kissing both sides of each other’s faces as a gesture of friendship and greeting or the common sight of two women or two men walking along the street arm-in-arm in African countries. When working with clients of diverse cultural backgrounds, the dental hygienist should do the following:

DENTAL HYGIENE PROCESS IN A CROSS-CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT

Whether a client is from a different country or from just down the street, his or her health status and experiences with healthcare delivery are largely dependent on cultural background. It is unlikely that a dental hygienist of one culture will be able to perceive, understand, and evaluate the factors influencing clients from another culture unless cultural sensitivity is developed. Development of cultural sensitivity is crucial for high-quality dental hygiene care because in a global society, dental hygienists cannot afford to function ethnocentrically.

The dental hygiene practitioner recognizes that the care of clients from different cultures or ethnic groups takes more time than does caring for clients from similar cultures. Longer time should be scheduled to accommodate the need for translation, repetition, clarification, and socialization to dental hygiene care. Sometimes, careful scheduling may be necessary to accommodate for clients from different cultural groups. Recall that a Muslim may cancel or not arrive for appointments scheduled during Ramadan because he or she is not permitted to put anything with flavorings into the mouth while fasting. Therefore, exposure to dentifrices, mouth rinses, prophylaxis paste, dental sealants, or professionally applied fluorides would break or jeopardize the quality of the fast. Additional guidelines for cross-cultural dental hygiene are listed in Box 5-2, Guidelines for Cross-Cultural Dental Hygiene.

BOX 5-2 Guidelines for Cross-Cultural Dental Hygiene

Assessment, Diagnosis, and Care Planning

The culturally competent dental hygienist understands that values and experiences shape everyone’s perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes. Most dental hygiene data collection tools direct the hygienist to gather information about the client’s health; however, a complete evaluation of the client’s condition can only be obtained from assessment of the client’s values and beliefs of the culture, ethnic group, or subculture. Therefore, assessing clients to identify culture-specific information is essential.

An ethnic and cultural assessment guide is presented in Table 5-6. This guide need not be a separate form but may be incorporated into existing data collection documents, interactions, and procedures. The dental hygiene diagnosis should identify the client’s unmet human needs that can be fulfilled through dental hygiene care, the cause of disease, the client’s perception of the cause of disease, the evidence for the diagnosis, and related cultural factors. With this detailed focus, an individualized care plan can be developed and appropriate interventions selected. Using a nonjudgmental, nonethnocentric approach, the dental hygienist assesses the client’s level of acculturation, English language skills, cultural health practices, and home remedies. Factors such as language comprehension, dietary preferences, and attitudes about the predominant culture can provide important cues for assessing the influence of the client’s cultural background. By synthesizing this information, the dental hygienist can conduct more positive, culturally informed interactions with the patient (see Tables 5-2 and 5-4). The dental hygienist who is able to demonstrate acceptance of diversity can establish trust with the client and achieve improved outcomes.

TABLE 5-6 Dental Hygiene Cultural Assessment

Adapted from Bloch B: Bloch’s ethnic/cultural assessment guide. In Orgue MS, Bloch B, Monroy LA, eds: Ethnic nursing care: a multicultural approach, St Louis, 1983, Mosby; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General, Rockville, Md, 2000, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health.

Implementation

Dental hygiene interventions, whether educational, technical, or interpersonal, must be congruent with cultural values. Client values and needs guide the selection of interventions. As demonstrated by the anecdote about the Liberian girl at the beginning of this chapter, oral hygiene interventions must be culturally acceptable if they are to result in successful uptake by the host culture. Successful dental hygiene programs are often given legitimacy by coupling them with culturally accepted values or respected figures. In Sri Lanka, “[o]ral hygiene exercises are performed in Sunday schools run by the monks to propagate the teachings of Buddha. The religious leadership provided in the village gives the needed credibility to the program, and the villagers adhere strictly to the oral hygiene practices taught by the monks because of the respect they command in the villages.”9 In predominantly Muslim countries, people are taught that prayers from a clean mouth are received more favorably by Allah; therefore oral hygiene self-care compliments prayer rituals.10

These vignettes underscore the need to understand different cultures if client oral health is to be achieved. As long as cultural beliefs or practices cause no harm, the dental hygienist can determine their importance to the client and recognize that their continued practice might assist in maintaining an effective client-provider relationship (Figure 5-5). Even if the behavior is ineffective, the client’s comfort with and belief in its effectiveness can support a situation in which the person might otherwise feel alienated. Go to the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene to view resources for understanding people within various cultures. Obviously, not all people within a culture will subscribe to these beliefs; however, this guide can serve as a starting point for understanding people of diverse cultures.

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene to view resources for understanding people within various cultures. Obviously, not all people within a culture will subscribe to these beliefs; however, this guide can serve as a starting point for understanding people of diverse cultures.

Evaluation

In cross-cultural interactions, the evaluation phase of care calls for an awareness of the client’s cultural perspective of success. Frequent solicitation of the client’s perspectives, level of understanding, psychomotor skill development, and self-care practices is particularly important. Evaluation should determine whether dental hygiene services are meeting the client’s needs. Urging clients to talk about their oral health practices and status helps with cross-cultural communication. In addition to clinical indicators of health, validation occurs via feedback from the client and client’s family that the client’s needs are being met.

FUTURE OF CROSS-CULTURAL DENTAL HYGIENE

Undergraduate, graduate, and continuing education programs offer opportunities to develop cross-cultural competence. Many undergraduate programs possess foreign language requirements to enable dental hygienists to communicate outside their native language. Some are adding international and multicultural content to courses and developing student exchange and study abroad internships. Dental hygiene student organizations sponsor and promote activities that raise awareness about population diversity while simultaneously developing competence in cross-cultural environments.

Dental hygienists may work abroad for dentists or multinational companies in global markets. International dental hygiene employment opportunities encompass both the profit and the nonprofit sectors and may span the realms of private practice, the oral health products industry, higher education, the World Health Organization, the Pan-American Health Organization, Operation Smile International, Physicians for Peace, Doctors Without Borders, and other international service agencies.

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Review common healthcare beliefs and practices inherent in the client’s culture as a starting point; verify client’s beliefs and practices.

Review common healthcare beliefs and practices inherent in the client’s culture as a starting point; verify client’s beliefs and practices.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

When language is a barrier, an interpreter can enhance and validate communication. Clients have a right to an interpreter.

When language is a barrier, an interpreter can enhance and validate communication. Clients have a right to an interpreter. Investigate culturally based therapies to ensure safety and efficacy. Document client’s use of culturally based therapies and client’s response to professional care, instructions, and recommendations.

Investigate culturally based therapies to ensure safety and efficacy. Document client’s use of culturally based therapies and client’s response to professional care, instructions, and recommendations.KEY CONCEPTS

Cross-cultural dental hygiene encompasses the social, political, ethnic, religious, and economic realities that people experience in culturally diverse environments.

Cross-cultural dental hygiene encompasses the social, political, ethnic, religious, and economic realities that people experience in culturally diverse environments. Culture is integral in dental hygiene care because an individual’s conception of oral wellness, disease, and illness are culturally determined.

Culture is integral in dental hygiene care because an individual’s conception of oral wellness, disease, and illness are culturally determined. Humanism recognizes the worth of all individuals through concern for and understanding of their attitudes, values, behavior patterns, and way of life.

Humanism recognizes the worth of all individuals through concern for and understanding of their attitudes, values, behavior patterns, and way of life. An individual is a biopsychosocial and spiritual being who brings uniqueness in race, culture, ethnicity, attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, and experience. This uniqueness affects the client’s acceptance of and response to professional care.

An individual is a biopsychosocial and spiritual being who brings uniqueness in race, culture, ethnicity, attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, and experience. This uniqueness affects the client’s acceptance of and response to professional care. One goal of cross-cultural dental hygiene is to make the oral healthcare setting a welcoming place for individuals who might otherwise feel disconnected or disenfranchised.

One goal of cross-cultural dental hygiene is to make the oral healthcare setting a welcoming place for individuals who might otherwise feel disconnected or disenfranchised. Race refers to the classification of human beings based on physical characteristics; ethnicity refers to unique cultural practices that reflect distinct customs, language, and social values. There are more similarities among racial groups than there are differences.

Race refers to the classification of human beings based on physical characteristics; ethnicity refers to unique cultural practices that reflect distinct customs, language, and social values. There are more similarities among racial groups than there are differences. Culture is the set of behaviors learned in order for a person to adapt successfully to life within a particular group; it includes beliefs, traditions, experiences, customs, rituals, and language.

Culture is the set of behaviors learned in order for a person to adapt successfully to life within a particular group; it includes beliefs, traditions, experiences, customs, rituals, and language. Stereotyping is the erroneous behavior of assuming that a person possesses certain characteristics simply because he or she is a member of a particular group.

Stereotyping is the erroneous behavior of assuming that a person possesses certain characteristics simply because he or she is a member of a particular group.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

website (at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene) and other links that you find. What behaviors should you use or avoid when interacting with members of these cultural groups? What are the cultural barriers that may prevent members of the community from accessing dental and dental hygiene services and from achieving optimal oral health? What can be done to reverse these trends?

website (at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene) and other links that you find. What behaviors should you use or avoid when interacting with members of these cultural groups? What are the cultural barriers that may prevent members of the community from accessing dental and dental hygiene services and from achieving optimal oral health? What can be done to reverse these trends?1. McKinney B. Keep it simple and smile: the role of the dental hygienist in international health. Norfolk, Va: Old Dominion University, School of Dental Hygiene (unpublished); 1989.

2. Taylor C., Lillis C., LeMone P., Lynn P. Fundamentals of nursing, ed 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006.

3. U.S. Census Bureau: American community survey, by race, 2006. Available at: www.census.gov. Accessed December 2007.

4. U.S. Census Bureau: U.S. interim projections by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin, 2004. Available at: www.census.gov/ipc/www/usinterimproj. Accessed December 2007.

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010: understanding and improving health. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000.

6. U.S. Census Bureau: Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2006, August 2007, U.S. Dept. of Commerce. Available at: www.census.gov/prod/2007pubs/p60-233.pdf. Accessed December 2007.

7. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institute of Health; 2000.

8. Routasalo P. Physical touch in nursing studies: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 1999;30:843.

9. Saparamadu K.D.G. The provision of dental services in the Third World. Int Dent J. 1986;36:194.

10. Mazhar U: Oral hygiene: Islamic perspective. Available at: www.crescentlife.com/wellness/oral_hygiene.htm. Accessed December 2007.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..