CHAPTER 2 Human Needs Theory and Dental Hygiene Care

BACKGROUND

Dental hygiene care promotes health and prevents oral disease over the human life span through the provision of educational, preventive, and therapeutic services.1 To this end the dental hygienist is concerned with the whole person, applying specific knowledge about the client's emotions, values, family, culture, and environment, as well as general knowledge about the body systems. The dental hygienist views clients as being actively involved in their care, because ultimately clients must use self-care and seek professional care to obtain and maintain their oral wellness.

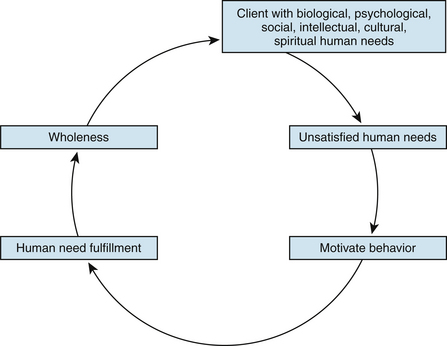

Human needs theory helps dental hygienists understand the relationship between human need fulfillment and human behavior. A human need is a tension within a person. This tension expresses itself in some goal-directed behavior that continues until the goal is reached. Human needs theory explains that need fulfillment dominates human activity, and behavior is organized in relation to unsatisfied needs.2 Moreover, the dental hygienist uses client unsatisfied needs as motivators to guide the client toward optimal oral wellness.

Although many human needs theorists have provided the theoretic substance for understanding human needs and the motivation inherent in meeting these needs, Maslow's work is highlighted here as a foundation for discussing human needs theory in dental hygiene.

MASLOW'S HIERARCHY OF NEEDS

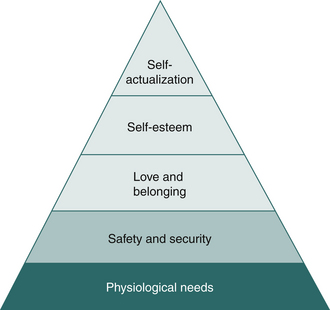

Abraham Maslow identified and assigned priorities to basic human needs. His theory maintains that certain human needs are more basic than others. As a result, some needs must be met before individuals turn their attention to meeting other needs.2 Maslow prioritized human needs in a hierarchy of five categories based on their power and strength to motivate behavior (Figure 2-1). The hierarchy is arranged with the most imperative needs for survival at the bottom and the least imperative at the top. On the most basic, or first, level of human needs are physiologic needs, such as the need for food, fluids, sleep, and exercise. According to Maslow's theory, a person is dominated by physiologic needs; if these needs are not reasonably satisfied, all other categories of needs in the hierarchy may seem irrelevant or be relegated to low priority.

Figure 2-1 Maslow's hierarchy of needs.

(Adapted from Potter PA, Perry AG: Fundamentals of nursing, ed 3, St Louis, 1993, Mosby.)

On the second level are safety needs, including the need for both physical and psychologic security. Safety needs include the need for stability, protection, structure, and freedom from fear and anxiety. In times of danger, the need to ensure safety and protection becomes paramount. Every other need becomes less important. Loss of parental protection, war, and being confronted with new tasks, strangers, or illness all are threats to the need for safety.

On the third level are love and belonging needs. They include the need for affectionate relationships and the need for a place within one's culture, group, or family. Love and belonging needs are expressed in the desire for tenderness, affection, contact, intimacy, togetherness, and face-to-face encounters. Love needs involve both giving and receiving love. Love and belonging needs also are expressed in the need to overcome feelings of alienation, aloneness, or strangeness brought on by the scattering of family, friends, and significant others.

On the fourth level of Maslow's hierarchy are self-esteem needs such as feelings of confidence, usefulness, achievement, and self-worth. Esteem needs include the need for a stable, firmly based, wholesome self-evaluation; the need for respect and esteem of self as well as esteem from others; a desire for strength, mastery, and competitiveness; and a need for feeling confident, independent, and freed. Deprivation of these needs results in feelings of inferiority, helplessness, and discouragement. Fulfillment of esteem needs results in feelings of capability and a willingness to be a contributor to society.

The final level of the hierarchy is the need for what Maslow calls self-actualization, a state in which each person is fully achieving his or her potential and is able to solve problems and cope realistically with life's situations.

Maslow points out that those individuals in whom a certain need has always been met or satisfied are best equipped to withstand deprivation of that need at some future time. Individuals whose needs have not been met in the past respond differently to current need deprivation than do people who have never been deprived.

HUMAN NEEDS CONCEPTUAL MODEL OF DENTAL HYGIENE

Dental hygiene's Human Needs Conceptual Model is a theoretic framework for dental hygiene care.3-6 This conceptual model, or school of thought, defines an approach to dental hygiene care based on human needs theory. Human needs theory was selected for the following reasons:

It is recognized by the World Health Organization's definition of health as “the extent to which an individual or group is able, on the one hand, to realize aspirations and satisfy needs and, on the other hand, to change and cope with the environment.”7

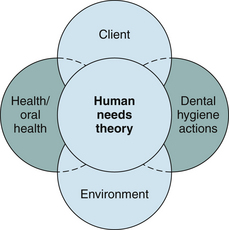

It is recognized by the World Health Organization's definition of health as “the extent to which an individual or group is able, on the one hand, to realize aspirations and satisfy needs and, on the other hand, to change and cope with the environment.”7The Human Needs Conceptual Model further defines the four major concepts of the dental hygiene paradigm (client, environment, health and oral health, and dental hygiene actions) in terms of human needs theory (Figure 2-2) and provides a comprehensive and client-centered approach to the dental hygiene process. The manner in which human needs theory defines the paradigm concepts and the steps of the dental hygiene process is described in the following sections and compared with Global Paradigm definitions in Tables 2-1 and 2-2.

Figure 2-2 Dental hygiene's paradigm concepts are explained in terms of human needs theory in the Human Needs Conceptual Model.

(Adapted from Yura H, Walsh M: The nursing process, ed 5, Norwalk, Conn, 1988, Appleton and Lange.)

TABLE 2-1 Comparison of the Major Four Paradigm Concepts∗

| Paradigm Concepts | Global Definitions8 | Human Needs Conceptual Model Definitions3,4 |

|---|---|---|

| Client | The recipient of dental hygiene care; includes persons, families, and members of groups and communities of all ages, genders, and sociocultural and economic states. | A biologic, psychologic, spiritual, social, cultural, and intellectual human being who is an integrated, organized whole and whose behavior is motivated by human need fulfillment; may be an individual, a family, or a group. |

| Environment | Factors other than dental hygiene actions that affect the client's attainment of optimal oral health. These include economic, psychologic, cultural, physical, legal, educational, ethical, and geographic factors. | The milieu in which the client and dental hygienist find themselves, which includes many dimensions (e.g., society, climate, geography, politics, economics) that influence the manner, mode, and level of human need fulfillment for the person, family, and community. |

| Health and oral health | The client's state of well-being, which exists on a continuum from optimal wellness to illness and fluctuates over time as the result of biologic, psychologic, spiritual, and developmental factors. Oral health and overall health are interrelated because each influences the other. | A state of well-being that exists on a continuum from maximum wellness to maximum illness. The higher the level of human need fulfillment, the higher the state of wellness for the client. |

| Dental hygiene actions | Interventions that a dental hygienist can initiate to promote oral wellness and to prevent or control oral disease. These actions involve cognitive, affective, and psychomotor performances and may be provided in independent, interdependent, and collaborative relationships with the client and the healthcare team. | Interventions that assist clients in meeting their human needs related to optimal oral wellness and quality of life throughout the life cycle. |

∗ Defined globally by dental hygiene's paradigm and further defined by the Human Needs Conceptual Model.

TABLE 2-2 Dental Hygiene Process∗

| Steps | Generic Definitions | Human Needs Conceptual Model |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment | Systematic collection and analysis of the following data to identify client needs and oral health problems: medical and dental histories; vital signs; extraoral and intraoral examination; periodontal and dental examination; radiographs; indices; and risk assessments (e.g., tobacco, systemic conditions, caries)9 | Systematic data collection and evaluation of eight human needs as being met or unmet based on all available assessment data |

| Dental hygiene diagnosis | Use of critical decision-making skills to reach conclusions about the patient or client's dental hygiene needs based on all available assessment data10 | Identification of unmet human needs among the eight related to dental hygiene care (i.e., human need deficit) and of the cause as evidenced by signs and symptoms |

| Planning | The establishment of realistic goals and treatment strategies to facilitate optimal oral health9 | Establishment of goals for client behavior with time deadlines to meet identified unmet human needs |

| Implementation | Provision of treatment as identified in the assessment and planning phase9 | The process of carrying out planned interventions targeting causes of unmet needs |

| Evaluation | Measurement of the extent to which goals identified in the treatment plan were achieved9 | The outcome measurement of whether client goals have been met, partially met, or unmet |

∗ Defined globally by the ADA Commission on Dental Hygiene Accreditation and/or by the American Dental Education Association and then further defined by the Human Needs Conceptual Model.

Concept 1: Client

In the Human Needs Conceptual Model, the client is a biologic, psychologic, spiritual, social, cultural, and intellectual human being who is an integrated, organized whole and whose behavior is motivated by human need fulfillment. Figure 2-3 illustrates this concept. Human need fulfillment restores a sense of wholeness as a human being. The client can be an individual, a family, or a group and is viewed as having eight human needs that are especially related to dental hygiene care.2,3

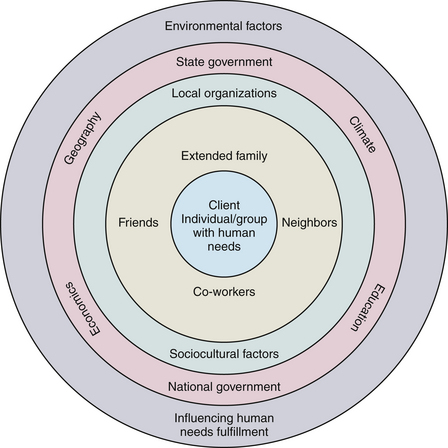

Concept 2: Environment

In the Human Needs Conceptual Model, the environment influences the manner, mode, and level of human need fulfillment for the person, family, and community. The concept of environment in the Human Needs Conceptual Model is the milieu in which the client and dental hygienist find themselves. The environment affects the client and the dental hygienist, and the client and the dental hygienist also influence the environment. The concept of the environment is shown in Figure 2-4 and includes dimensions such as society, climate, geography, politics, economics, education, socioethnocultural factors, significant others, the family, the community, the state, the nation, and the world.

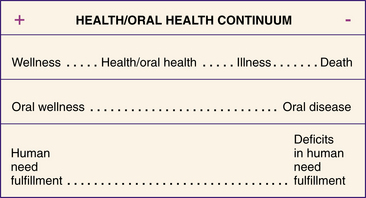

Concept 3: Health and Oral Health

The concept of health and oral health is a state of well-being that exists on a continuum from maximal wellness to maximal illness (Figure 2-5). The higher the level of human need fulfillment, the higher the state of wellness for the individual. Maximal wellness is achieved with maximal fulfillment of human needs; maximal illness occurs with minimal or absent human need fulfillment. Along the health and oral health continuum, there are degrees of wellness and illness that are associated with varying levels of human need fulfillment.

Concept 4: Dental Hygiene Actions

Dental hygiene actions are behaviors of the dental hygienist aimed at assisting clients in meeting their eight human needs related to optimal oral wellness and quality of life throughout the life cycle. Dental hygiene actions take into account such client and environmental factors as the individual's age, gender, roles, lifestyle, culture, attitudes, health beliefs, climate, and level of knowledge.

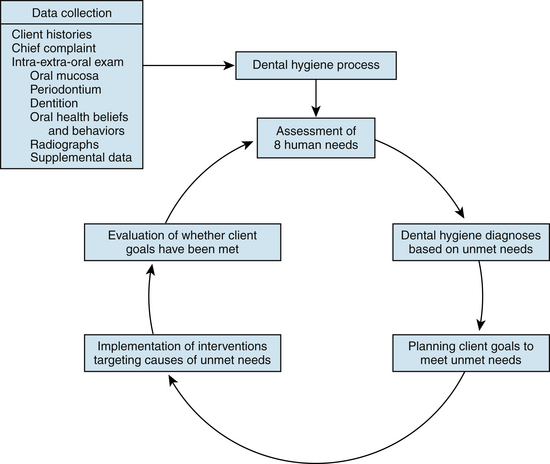

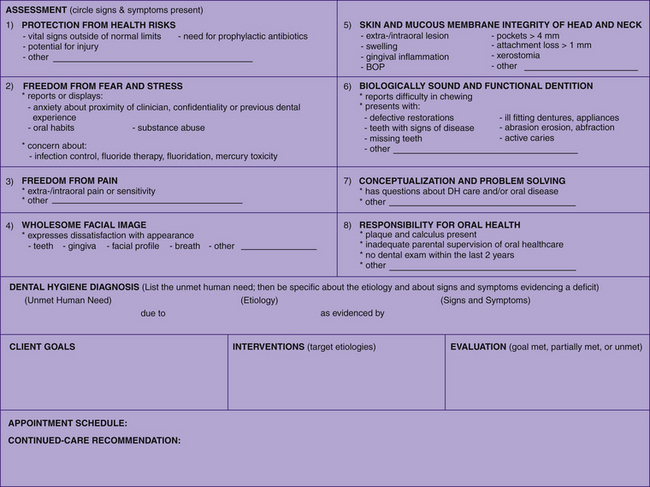

Inherent in the concept of dental hygiene actions is the dental hygiene process as shown in Figure 2-6. After initial collection of client histories, vital signs, and environmental, clinical, radiographic, and risk assessments, findings are evaluated to determine whether or not eight human needs are met (Box 2-1). These eight human needs relate to physical, emotional, intellectual, social, and cultural dimensions of the client and the environment that are relevant to dental hygiene care. Findings from the assessment of these human needs ensures a comprehensive and humanistic approach to care. Dental hygienists use these findings to make dental hygiene diagnoses based on unmet human needs (i.e., human need deficits) and then to plan (i.e., set goals, sequence appointments, select interventions), implement, and evaluate outcomes of dental hygiene care (i.e., goals met, partially met, or unmet). Figure 2-7 provides a sample clinical tool for use in assessing the eight human needs; making dental hygiene diagnoses; and planning, implementing, and evaluating dental hygiene interventions designed to meet the identified unmet human needs related to dental hygiene care. (Chapters 19 and 20 provide detailed explanations of how to apply the dental hygiene process in the context of the dental hygiene Human Needs Conceptual Model.)

Figure 2-6 The concept of dental hygiene actions in the Human Needs Conceptual Model of dental hygiene as it relates to the dental hygiene process.

DENTAL HYGIENE'S EIGHT HUMAN NEEDS

The eight human needs related to dental hygiene care are described in the following sections.

Protection from Health Risks

Protection from health risks is the need to avoid medical contraindications related to dental hygiene care and to be free from harm or danger involving the integrity of the body structure and environment around the person. This human need includes clients' need to be in a state of good general health through efficient functioning of body organs and systems, or under the active care of a physician in a controlled state of general health that provides for adequate function of body organs and systems.

Assessment

The dental hygienist obtains information related to the client's general health by careful evaluation of the client's verbal and nonverbal behavior during history taking, as well as by clinical, radiographic, and laboratory (if applicable) assessment. Indications that the client's need for protection from health risks is unmet include but are not limited to the following:

Evidence from the client's health history of the need for immediate referral to, or consultation with, a physician regarding uncontrolled disease (e.g., blood pressure reading or blood glucose level outside of normal limits)

Evidence from the client's health history of the need for immediate referral to, or consultation with, a physician regarding uncontrolled disease (e.g., blood pressure reading or blood glucose level outside of normal limits)Implications for Dental Hygiene Care

Dental hygienists with questions about a client's general health and its influence on dental hygiene care consult the client's physician before providing dental hygiene care. In general, clients with no physician of record are referred to one for examination. Obtaining initial information related to a client's general and oral health and updating it at each dental hygiene care appointment are essential to ensure that the client's need for protection from health risks is met.

Freedom from Fear and Stress

Freedom from fear and stress is the need to feel safe and to be free from emotional discomfort in the oral healthcare environment and to receive appreciation, attention, and respect from others.

Assessment

Fulfillment of this need can be assessed by evaluating the client's verbal and nonverbal behavior, as well as by careful examination of the face and oral cavity for signs of stress. Nonverbal behavior is evaluated by careful observation of the client on reception, during history taking, and throughout the provision of dental hygiene care. Indications that the client's need for freedom from fear and stress is unmet include but are not limited to the client's self-report or display of at least one of the following:

Implications for Dental Hygiene Care

To some clients, the dental hygiene appointment itself may signal threat or danger and may trigger fear and stress. Being confronted with strangers, uncontrollable objects (e.g., dental hygiene instruments), loss of parental protection (for children), and the risk (however minute) of contracting an infectious or life-threatening disease such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) all are threats to the need for freedom from fear and stress.

If fear and stress are apparent at the beginning of, or during, the dental hygiene appointment, the dental hygienist initiates fear- or stress-control interventions immediately. Such interventions include reassuring the client that every effort will be made to provide care in as comfortable and safe a manner as possible; communicating with empathy; providing positive reinforcement of desired behavior; and answering all questions as completely as possible. For instance, clients may ask about safety factors associated with radiation, infection control, mercury-containing dental restorations (amalgam), water fluoridation, and fluoride therapy. The dental hygienist reassures about the safety of these procedures and provides evidence-based information about the rationales for their use. At all times the dental hygienist demonstrates, through behavior, the unique worth of each client as a human being and ensures that the client's dignity is supported. It is particularly critical for the dental hygienist to be aware of and to exhibit respect for diversity in cultural and ethnic groups and the health beliefs, values, and behaviors associated with them. (Also, see Chapter 5 on cultural competence, Chapter 37 on behavioral management of pain and anxiety, and Chapter 40 on the use of nitrous oxide–oxygen analgesia for the apprehensive client.)

Freedom from Pain

Freedom from pain is the need to be exempt from physical discomfort in the head and neck area. This human need is a strong motivator for clients to perform behavior that will lead to its fulfillment.

Assessment

Fulfillment of this need can be assessed by evaluating the client's verbal and nonverbal behavior, as well as by careful examination of the face and oral cavity for signs of physical discomfort. Verbal behavior is evaluated by inquiring about the client's reason for seeking dental hygiene care and by collecting data during history taking and during the intraoral and extraoral examinations. Nonverbal behavior is evaluated by careful observation of the client on reception, during history taking, and throughout the provision of dental hygiene care. Indications that the client's need for freedom from pain is unmet include but are not limited to client self-report or display of at least one of the following

Implications for Dental Hygiene Care

If pain is apparent at the beginning of or during the dental hygiene appointment, the dental hygienist initiates pain control interventions immediately, including client referral to the dentist for care. Ways in which the dental hygienist provides pain control for clients are discussed in Chapters 39 and 40. Because the mouth is very sensitive, dental hygienists perform instrumentation techniques as carefully and as gently as possible, especially when treating a client who is not anesthetized.

Wholesome Facial Image

Wholesome facial image is the need to feel satisfied with one's own oral-facial features and breath. Facial image is determined by individuals' perception of their physical characteristics and their interpretation of how that image is perceived by others. Facial image is influenced by normal and abnormal physical changes and by cultural and societal attitudes and values. For example, normal developmental changes such as growth and aging affect a person's facial image. Cultural values lead Surma women in Ethiopia to wear lip plates as a sign of physical beauty or Maori people to covet face tattoos that tell a story of a person's accomplishments and ancestry. In the United States, society emphasizes youth, beauty, and wholeness, a fact that is apparent in television programs, movies, and advertisements. These cultural attitudes and values affect how people perceive their physical bodies, because body image is a combination of the ideal and the real.11

People generally do not adapt quickly to changes in the physical body. For example, people who experience normal aging often report that they do not feel different, but when they look in the mirror they are surprised by their aged facial characteristics. Facial disfigurement due to disease, trauma, or surgery is an obvious stressor affecting body image. For example, tooth loss is a stressor that affects facial image through a change in personal appearance.

The importance of a change in appearance is determined partly by individual perceptions of the alteration and by personal estimations of how others perceive that alteration. For example, if someone associates possession of natural teeth with femininity or masculinity, loss of teeth may be a very significant alteration, one that may threaten the person's sexuality or sense of self. Similarly, clients with dentures, a cleft lip, or facial disfigurement after surgical treatment of oral cancer may reduce social contacts out of fear of people's reactions to them. Such clients may feel isolated, excluded, stigmatized, or helpless. Their feeling of social isolation may be based in reality, because people may avoid contact with them for fear of causing embarrassment or offense. Thus, body image stressors can negatively alter the client's body image, which in turn may negatively alter the client's self-concept and behavior.11

Indications that the client's need for a wholesome facial image is fulfilled include such evidence as the client's statement of satisfaction with his or her appearance, being neatly groomed, and making an effort to bring out the best of facial assets with careful makeup and attention to hairstyle.

Assessment

The dental hygienist assesses the client's need for a wholesome facial image based on information obtained from history taking, direct observation, and casual conversation with the client. For example, the client's satisfaction with the general appearance of the teeth, mouth, and facial profile can be determined by asking questions such as, “Is anything about your teeth that bothers you?” or “Is there anything about your mouth that concerns you?” Such questions may elicit responses indicating dissatisfaction with tooth stain, calculus, receding gums, bleeding gums, a discolored restoration, or malaligned teeth. Indications that the client's need for a wholesome facial image is unmet include but are not limited to clients' self-report of dissatisfaction with the following:

Such unmet needs have implications for dental hygiene care, including referral to other health professionals (e.g., general dentist, periodontist, orthodontist) for additional care.

Implications for Dental Hygiene Care

Tooth loss, malaligned teeth, oral cancer, and facial disfigurement are examples of facial image stressors related to the oral cavity that dental hygiene clients may experience. The dental hygienist listens to client doubts about treatment outcomes related to these stressors and provides information, reassurance, and referrals as needed. Complimenting such clients on some aspect of their appearance assists them to focus on positive attributes and features. For some clients, encouragement to seek other support systems to share feelings about body changes may be helpful in assisting them to reinforce accomplishments, strengths, and positive attributes.11

Facial image stressors affect self-concept and motivate behavior, including oral health behavior. The dental hygienist's acceptance of a client with an altered self-concept due to facial image stressors may be the factor that stimulates positive rehabilitative results. For example, for clients whose physical appearance has changed drastically from head and neck cancer surgery and who must adapt to a new facial image, being accepted by the dental hygienist as a human being who has ideas, feelings, and values and who is worthy and whole despite illness or physical alterations is important and can provide an example for the client and family members that affirms the client's self-worth.11 The client's feelings of insecurity, fears of rejection, or loss of self-worth can be lessened through sensitive, knowledgeable dental hygiene care.

It is important for dental hygienists to be in touch with their own feelings and expectations about clients undergoing such facial image stressors because the dental hygienist's reaction to a client's illness or physical alteration can have a significant impact on the client's self-concept and the outcome of care. Clients with low self-esteem because of altered facial image may be particularly sensitive to the way the dental hygienist involves them in their own care. A dental hygienist with mixed feelings about clients' physical alteration may be hesitant in making suggestions, thus inadvertently implying that they might be unable to follow suggestions. Alternatively, the hygienist may insist that such clients assume too much responsibility for their own care, thus causing anxiety and frustration. In either case, clients' self-esteem and facial image may be additionally threatened rather than strengthened. If, however, the dental hygienist demonstrates confidence in a client's abilities and is confident in personal feelings about and expectations of the client, then the client's sense of wholesome facial image, as well as self-worth, will be reinforced. 11

Skin and Mucous Membrane Integrity of the Head and Neck

Skin and mucous membrane integrity of the head and neck is the need for an intact and functioning covering of the person's head and neck area, including the oral mucous membranes and periodontium. These intact tissues defend against harmful microbes, provide sensory information, resist injurious substances and trauma, and reflect adequate nutrition.

Assessment

Assessment of this human need occurs initially by careful observation of the client's face, head, and neck area as part of an overall client appraisal on reception and seating; and by careful examination of the oral cavity and adjacent structures and the periodontium before planning and implementing dental hygiene care (see Chapters 13, 14, and 17).

Indications that this human need is unmet include but are not limited to the presence of any of the following conditions:

Evidence of an eating disorder (e.g., trauma around the mouth from implements used to induce vomiting or enamel erosion) (Chapter 52)

Evidence of an eating disorder (e.g., trauma around the mouth from implements used to induce vomiting or enamel erosion) (Chapter 52)Implications for Dental Hygiene Care

The dental hygienist examines all skin and mucous membranes in and about the oral cavity, including the periodontium, documents findings, and informs the dentist and the client about evidence of abnormal tissue changes and/or disease. A variety of skin and oral mucosal lesions may be observed that may or may not be symptomatic. Recognition, treatment, and follow-up of specific lesions may be of great significance to the general and oral health of the client. Routine extraoral and intraoral examination of clients at the initial appointment and at each continued care appointment provides an excellent opportunity to control oral disease by early recognition and treatment. At least annually, clients are screened to detect potentially cancerous lesions. Moreover, it may be necessary to postpone a current appointment because of a client's need for urgent medical consultation or because of evidence of infectious lesions, such as herpes labialis.

Because periodontal disease is epidemic in the United States and elsewhere, the human need for skin and mucous membrane integrity of the head and neck is usually unmet in clients seeking dental hygiene care. In periodontal disease the sulcular, or pocket, epithelium becomes inflamed and ulcerated and bleeds readily on periodontal probing. Because the epithelium is not intact, harmful microbes enter the periodontal tissues and the bloodstream. Under these circumstances, dental hygiene strategies to meet the human need for skin and mucous membrane integrity of the head and neck include the following:

Moreover, dental hygienists use their extraoral and intraoral examination and interviewing skills to identify nutritional problems and provide counseling or appropriate referral. Dental hygienists are in an excellent position to recognize signs of poor nutrition and to take steps to initiate change. Regular contact with continued-care clients at 3-, 4-, or 6-month intervals enables dental hygienists to make observations of clients' physical status, food intake, and response to dental hygiene care. The dental hygienist informs the dentist of observations that indicate a nutritional problem and incorporates approaches to solving the problem into the dental hygiene care plan. When malnutrition or a serious eating disorder such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa is suspected, client referral for medical evaluation is a priority (see Chapter 52).

Biologically Sound and Functional Dentition

Biologically sound and functional dentition refers to the need for intact teeth and restorations that defend against harmful microbes, provide for adequate functioning and esthetics, and reflect appropriate nutrition and diet.

Assessment

Assessment of this need is ongoing throughout the dental hygiene care appointment but initially occurs while the hygienist is taking a careful dental history and carefully observing the client's dentition as part of a thorough examination of the oral cavity and adjacent structures preliminary to dental hygiene care. Indications that the client's need for a biologically sound dentition is unmet include but are not limited to client self-report or display of at least one of the following conditions:

Implications for Dental Hygiene Care

The dental hygienist documents existing conditions of the teeth, including restorations, deviations from normal, signs of caries, and missing teeth.

A bitewing radiographic survey may assist with evaluation and charting, especially between posterior teeth. All teeth with signs of disease and/or functional problems should be called to the immediate attention of the dentist. Performing caries-risk assessment, exposing radiographs based on assessment data, providing fluoride therapy and sealants, recommending home fluoride therapy or xylitol use, and referring to the dentist for periodic oral examination are dental hygiene interventions most frequently used to meet the client's need for a biologically sound dentition.

Nutritional assessment also is particularly important for clients who may be at risk for nutritional problems related to tooth loss, ill-fitting dentures, dental caries, and periodontal diseases. A complete nutritional assessment includes collecting data from observation and a dietary history (see Chapter 33).

Conceptualization and Problem Solving

Conceptualization and problem solving involve the need to understand ideas and abstractions to make sound judgments about one's oral health. This need is considered to be met if the client understands the rationale for recommended oral healthcare interventions; participates in setting goals for dental hygiene care; has no questions about professional dental hygiene care or dental treatment; and has no questions about the cause of the oral problem, its relationship to overall health, and the importance of the solution suggested to solve the problem.

Assessment

The dental hygienist assesses this need by listening to clients' questions and responses to the hygienist's answers. Indications that this need is unmet include but are not limited to evidence that the client has questions, misconceptions, or a lack of knowledge about at least one of the following:

Implications for Dental Hygiene Care

During client education, dental hygienists present the rationale and details of methods recommended for the prevention and control of oral diseases. In addition, they question clients to ensure understanding of concepts relevant to clients' oral health and recommended care and ask clients to demonstrate use of any explained home self-care device to clarify client understanding and evaluate ability to use the device. To ensure client understanding, the dental hygienist often augments verbal presentation with graphics and other types of visual aids. For example, to help a client conceptualize what biofilm is, where it is located, and its relationship to periodontal disease, the dental hygienist may do the following:

Provide a mirror for clients to view the inflammatory response of gingival tissues to biofilm in their mouths

Provide a mirror for clients to view the inflammatory response of gingival tissues to biofilm in their mouths Demonstrate use of an oral self-care tool for biofilm removal in the client's own mouth (e.g., floss) while the client observes in a mirror; observe the client's use, and provide feedback

Demonstrate use of an oral self-care tool for biofilm removal in the client's own mouth (e.g., floss) while the client observes in a mirror; observe the client's use, and provide feedbackResponsibility for Oral Health

Responsibility for oral health refers to the need for accountability for one's oral health as a result of interaction among one's motivation, physical and cognitive capability, and social environment.

Assessment

This need is assessed from data collected in the client's health, pharmacologic, dental, personal, and cultural histories and from direct observation of whether or not the client performs adequate daily oral self-care and seeks adequate professional care to prevent and control oral diseases. Indications that this need is unmet include but are not limited to the presence of any one of the following conditions:

Implications for Dental Hygiene Care

The dental hygienist assesses the client's oral health behaviors and suggests behaviors to the client (or to the parent/ healthcare decision maker when the client is a child) that should be initiated to obtain and maintain oral wellness. In providing oral health education, the dental hygienist appeals to clients' sense of self-determination to evoke the client's need for responsibility for oral health. The dental hygienist encourages the client to participate in setting goals for dental hygiene care, offers choices, and facilitates and reinforces client decision making. In addition, the hygienist addresses deficits in clients' psychomotor skill level and recommends strategies to enhance proper manipulation of the toothbrush, floss, or other oral self-care tools (e.g., use of lightweight power toothbrushes to compensate for psychomotor skill deficits that might be related to degenerative disabilities in arthritic clients).

A primary role of the dental hygienist is to motivate clients to adopt and maintain positive oral health behaviors. In this effort the dental hygienist views the client as being actively involved in the process of care. Using information from the client's history, oral examination, radiographs, and all other data collected during the initial assessment, the dental hygienist in collaboration with the client establishes goals for dental hygiene care. These goals must be related realistically to the client's individual needs, values, and ability level. Because each client has personal requirements for self-care, clients must participate in setting goals and must personally commit themselves to achieving them if oral disease control and prevention are to be successful over the life span.

SIMULTANEOUSLY MEETING NEEDS

Identification of the eight human needs related to dental hygiene care is a useful way for dental hygienists to evaluate and understand the needs of all clients and to achieve a client-centered practice. A client entering the oral care environment may have one or more unmet needs, and dental hygiene care delivered within a human needs conceptual framework addresses all of them simultaneously. The Human Needs Conceptual Model provides a holistic and humanistic perspective for dental hygiene care. The model addresses the client's needs in the physical, psychologic, emotional, intellectual, spiritual, and social dimensions and defines the territory for the practice of client-centered dental hygiene. Applying this model when interacting with clients, whether the client is an individual, a family, or a community, enhances the dental hygienist's relationship with the client and promotes the client's adoption of and adherence to the dental hygienist's professional recommendations.

Oral disease disrupts clients' ability to meet their human needs not simply in the physical dimension, but also in the emotional, intellectual, social, and cultural dimensions. Therefore the dental hygienist plans and provides interventions for clients with diverse needs. Using information from the client's histories, oral examination, radiographs, and all other data collected, the dental hygienist assesses clients for unmet needs and then considers how dental hygiene care can best help them meet those needs. After identifying which of a client's human needs are unmet, the dental hygienist, in collaboration with the client, sets goals and establish priorities for providing care to fulfill these needs. Setting goals and establishing priorities, however, does not mean that the dental hygienist provides care for only one need at a time. In emergency situations, of course, physiologic needs take precedence, but even then the dental hygienist is aware of the client's other psychosocial needs. For example, when providing care for a client with painful gingivitis, whose human needs for skin and mucous membrane integrity of the head and neck and for freedom from pain require immediate attention, the dental hygienist also takes into consideration the client's need for freedom from stress and wholesome facial image. Often, one need may take priority and the dental hygienist must first be concerned with the highest priority need (such as helping the client cope with a fear of having his or her teeth scaled before helping the client restore the integrity of the gingival tissues). But equally often the dental hygienist simultaneously addresses needs such as assisting a client in meeting the need for responsibility for oral health while also helping the client achieve freedom from pain.

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Discuss client's previous negative experiences related to dental or dental hygiene care, and reassure that every effort will be made to provide care as comfortably and safely as possible.

Discuss client's previous negative experiences related to dental or dental hygiene care, and reassure that every effort will be made to provide care as comfortably and safely as possible. Listen to doubts about treatment outcomes expressed by clients undergoing treatment related to facial image stressors, and provides information and reassurance as needed.

Listen to doubts about treatment outcomes expressed by clients undergoing treatment related to facial image stressors, and provides information and reassurance as needed. Present the rationale and details of methods recommended for the prevention and control of oral diseases, and ask questions to determine if the client needs clarification of concepts.

Present the rationale and details of methods recommended for the prevention and control of oral diseases, and ask questions to determine if the client needs clarification of concepts.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Discuss all procedures with clients, obtain informed consent, and encourage their participation in the dental hygiene care plan.

Discuss all procedures with clients, obtain informed consent, and encourage their participation in the dental hygiene care plan.KEY CONCEPTS

Dental hygiene care focuses on the promotion of oral health and the prevention of oral disease over the life span.

Dental hygiene care focuses on the promotion of oral health and the prevention of oral disease over the life span. The dental hygienist is concerned with the whole person, applying specific knowledge about the client's emotions, values, family, culture, and environment as well as general knowledge about the body systems.

The dental hygienist is concerned with the whole person, applying specific knowledge about the client's emotions, values, family, culture, and environment as well as general knowledge about the body systems. Clients are viewed as active participants in the process of dental hygiene care because the ultimate responsibility to use self-care and seek professional care to obtain and maintain oral wellness is theirs.

Clients are viewed as active participants in the process of dental hygiene care because the ultimate responsibility to use self-care and seek professional care to obtain and maintain oral wellness is theirs. Dental hygiene's Human Needs Conceptual Model is a theoretic framework for dental hygiene care. This conceptual model, or school of thought, defines an approach to dental hygiene care based on human needs theory.

Dental hygiene's Human Needs Conceptual Model is a theoretic framework for dental hygiene care. This conceptual model, or school of thought, defines an approach to dental hygiene care based on human needs theory. The Human Needs Conceptual Model defines the four major concepts of dental hygiene's paradigm (client, environment, health and oral health, and dental hygiene actions) in terms of human needs theory.

The Human Needs Conceptual Model defines the four major concepts of dental hygiene's paradigm (client, environment, health and oral health, and dental hygiene actions) in terms of human needs theory. Using information from the client's histories, oral examination, radiographs, and all other data collected, the dental hygienist uses these findings to assess whether or not the eight human needs related to dental hygiene are met.

Using information from the client's histories, oral examination, radiographs, and all other data collected, the dental hygienist uses these findings to assess whether or not the eight human needs related to dental hygiene are met. Assessment of the eight human needs ensures a comprehensive and humanistic approach to care. Dental hygienists use these findings to make dental hygiene diagnoses based on unmet human needs (i.e., human need deficits) and then to plan (i.e., set goals), implement, and evaluate outcomes of dental hygiene care (i.e., determining whether or not goals are met, partially met, or unmet).

Assessment of the eight human needs ensures a comprehensive and humanistic approach to care. Dental hygienists use these findings to make dental hygiene diagnoses based on unmet human needs (i.e., human need deficits) and then to plan (i.e., set goals), implement, and evaluate outcomes of dental hygiene care (i.e., determining whether or not goals are met, partially met, or unmet).CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

Given the following scenario, use the dental hygiene Human Needs Conceptual Model to list the human needs that are in deficit and to plan dental hygiene interventions to meet the identified human need deficits.

Devan Sacks, age 12, is a new client in the dental practice and has been scheduled for dental hygiene care. Devan is in the seventh grade and is one of the star players on the girls soccer team. She is accompanied by her mother, Margaret (age 32), and her sister Bridget (age 10). After completing health, dental, and personal histories, the dental hygienist initiates the assessment phase of the dental hygiene process of care, including a baseline assessment of human needs related to dental hygiene care, a complete dental and periodontal assessment, and self-care and skill level assessment. Significant findings include 6-mm probing depths around teeth 19 and 30, and 4- to 5-mm pockets around teeth 22 to 27. Oral hygiene was generally poor. Client has a knowledge deficit regarding oral biofilm, periodontal disease process, and status of the oral cavity.

1. American Dental Hygienists' Association:Dental hygiene: focus on advancing the profession, 2004-2005(position paper). Available at: www.adha.org/downloads/ADHA_Focus_Report.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2008.

2. Maslow A.H. Motivation and personality, ed 2. New York: Harper and Row; 1970.

3. Darby M., Walsh M. A human needs conceptual model for dental hygiene. Part I. J Dent Hyg. 1993;67:326.

4. Walsh M., Darby J. Application of the human needs conceptual model to the role of the clinician: Part II. J Dent Hyg. 1993;67:335.

5. Sato Y., Saito A., Nakamura-Miura A., et al. Application of the dental hygiene Human Needs Conceptual Model and the Oral Health–related Quality of Life Model to the dental hygiene curriculum in Japan. Int J Dent Hyg. 2007;5:158.

6. Darby M., Walsh M. Application of the Human Needs Conceptual Model to dental hygiene practice. J Dent Hyg. 2000;74:230.

7. World Health Organization: Working for health: an introduction to the World Health Organization. Available at: www.who.int/about/brochure_en.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2008.

8. American Dental Hygienists' Association: Policy 18–96 Glossary, 1996.

9. American Dental Association Commission on Dental Accreditation:. Accreditation standards for dental hygiene education programs. Chicago: American Dental Association., 1998. Available at: www.ada.org/prof/ed/accred/standards/dh.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2008.

10. American Dental Education Association. Exhibit 7: competencies for entry into the profession of dental hygiene. J Dent Educ. 2007;71(7):929. Available at: http://www.jdentaled.org/cgi/reprint/71/7/929.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2008.

11. Potter P.A., Perry A.G. Fundamentals of nursing, ed 7. St Louis: Mosby; 2009.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

SCENARIO 2-1

SCENARIO 2-1