CHAPTER 33 Nutritional Counseling

Identify individuals in need of nutritional counseling to control dental caries, promote postsurgical healing and tissue regeneration, reduce incidence of bone loss due to osteoporosis and osteopenia, or achieve optimal health.

Identify individuals in need of nutritional counseling to control dental caries, promote postsurgical healing and tissue regeneration, reduce incidence of bone loss due to osteoporosis and osteopenia, or achieve optimal health.Diet and nutrition are vital oral health components. Nutritional counseling is a process that can be used in the dental setting to help clients maintain optimum oral health and develop healthful behaviors that promote overall health. When providing nutritional counseling, individual factors such as age, gender, culture, economics, lifestyle, dental health, chronic disease, medications, allergies, and food avoidances need to be considered.

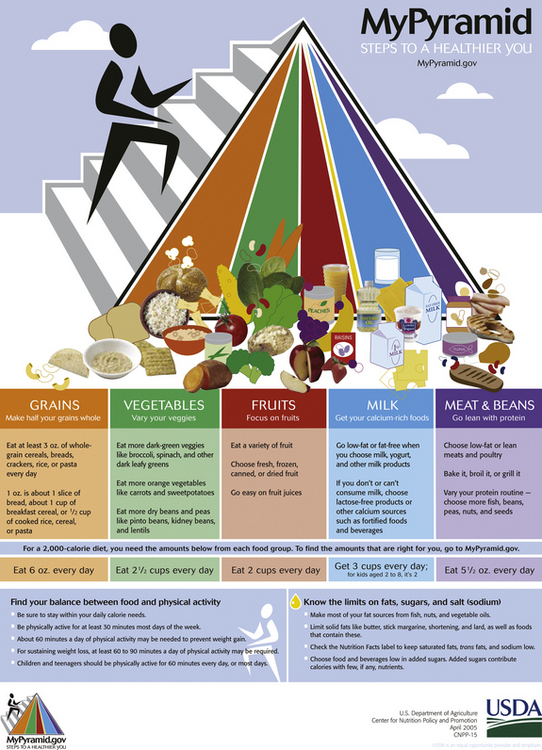

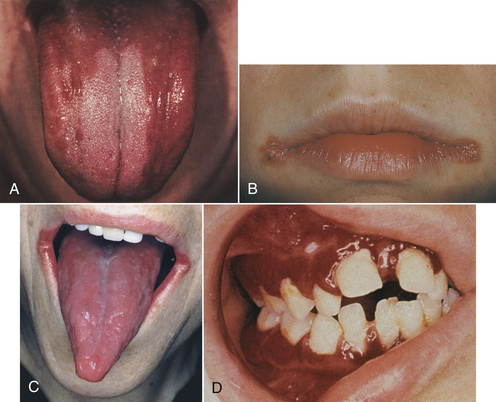

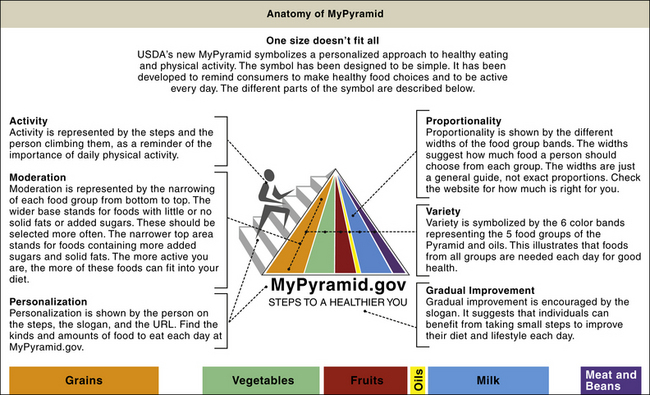

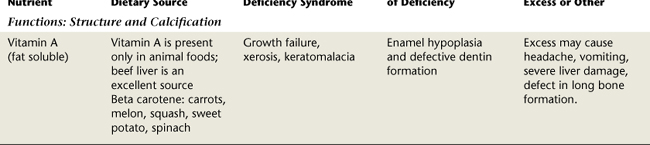

Nutritional deficiency or metabolic disease diagnosis is made by a physician after extensive data collection. Much of this information is outside of the scope of dental hygiene and therefore precludes the dental hygienist from functioning in the role of nutrition professional. As a health professional who sees clients on an ongoing basis, however, the dental hygienist needs to be knowledgeable about nutrition (Figure 33-1), oral manifestations of nutritional deficiencies (Figure 33-2), and oral health.1,2 For nutritional concerns outside the scope of dental hygiene practice, referral to a registered dietitian is indicated.

Figure 33-1 MyPyamid Food Guidance System.

(From USDA, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion 2005 [http://www.mypyramid.gov].)

Figure 33-2 Some oral manifestations of nutritional deficiencies A, Atrophy of the filiform and fungiform papillae on the dorsum of the tongue associated with iron deficiency anemia. B, Riboflavin deficiency characterized by erythema, maceration, and soggy white debris at the commissures of the mouth. C, Painful, beefy red, atrophic tongue, often with ulceration, associated with niacin deficiency. D, Severe gingivitis associated with scurvy.

(A and D, From Eisen D, Lynch DP: The mouth: diagnosis and treatment, St Louis, 1998, Mosby.)

NUTRITION ASSESSMENT

Nutrition assessment is the systematic collection of information to identify the need for nutritional counseling and make the appropriate recommendations and referrals. The client’s personal history can reveal information regarding educational, cultural, financial, and environmental influences on food intake. The health and pharmacologic histories identify health factors and medications that interfere with an individual’s ability to eat or the body’s ability to absorb nutrients. The dental history provides information about caries susceptibility and fluoride use; and the extraoral and intraoral examination may reveal the physical results of any nutritional excesses or deficiencies. These findings, along with a dietary assessment, direct the dental hygienist in the role of dietary counselor. Determining which clients need nutritional counseling involves analyzing information collected during the assessment phase of care.

Every client could benefit from nutritional counseling, but those most often targeted include clients with the following characteristics:

Health and Pharmacologic Histories

Questions normally included in a comprehensive health history provide clues to nutritional status, lifestyle behaviors, and overall health (see Chapter 10Figure 10-32Table 10-3). It is important for the health history to include weight and height measurements and space to note conditions and medications that interfere with food digestion, absorption, and metabolism. It is essential that the dental hygienist ask about dietary supplements, vitamins, and herbal preparations if not specified on the health history, and question clients about recent illnesses, changes in health behaviors, or modifications to their diets.

Height and Weight

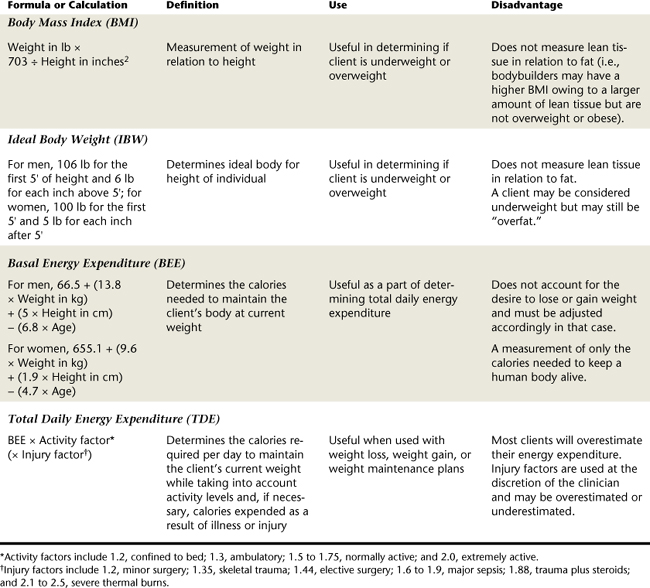

Height and weight can be used to determine the client’s body mass index. Body mass index (BMI) reflects weight in relation to height (Table 33-1); it is not a measure of lean body mass.

Although a BMI measurement does not reflect how much of the weight is fat, it does give a measurement associated with health risks such as heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and cancer. Another useful calculation is ideal body weight (see Table 33-1).

Exercise Patterns

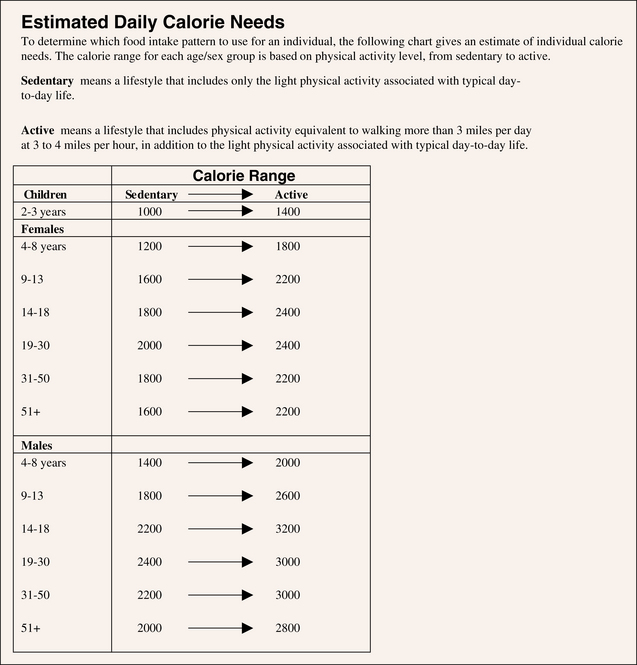

Activity levels ascertained during the health history interview may be used to calculate energy expenditure. An approximate daily caloric expenditure can be useful in planning for weight loss or weight gain. To accurately assess total daily energy expenditure (TDE), the basal energy expenditure must first be calculated.

Basal energy expenditure (BEE), the total energy output of a body at rest after a 12-hour fast in a room of comfortable temperature, is a measure of the amount of calories required to maintain body weight. To determine total daily energy expenditure, the BEE is multiplied by an activity factor (AF) (see Table 33-1). Again, the calculation used in these formulas provides a calorie count required for maintenance of the body at its current weight. For an individual to lose or gain weight, the calorie count must be adjusted accordingly. Calculation of total daily caloric intake for periodontal and oral surgery clients can also be calculated by multiplying the TDE by an injury factor (IF) (Box 33-1).

BOX 33-1 Calculation of Total Daily Calorie Intake for an Oral Surgery Client

BEE, Basal energy expenditure; TDE, total daily energy expenditure. The activity factor or injury factor may be adjusted to better describe the amount of activity or injury.

A 35-year-old woman weighs 118 pounds and is 5 feet 6 inches tall. Her exercise includes walking 4 miles every evening. She has undergone oral and maxillofacial reconstructive surgery to correct her malocclusion.

A registered dietitian should be the individual who adjusts specific nutrient values in the client’s diet.

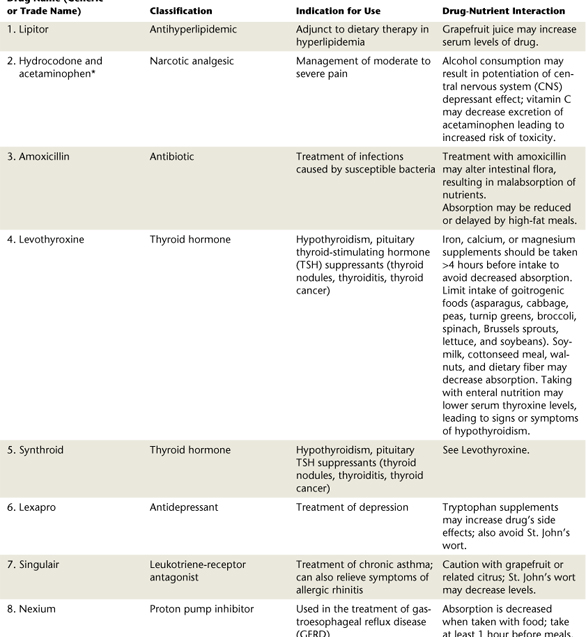

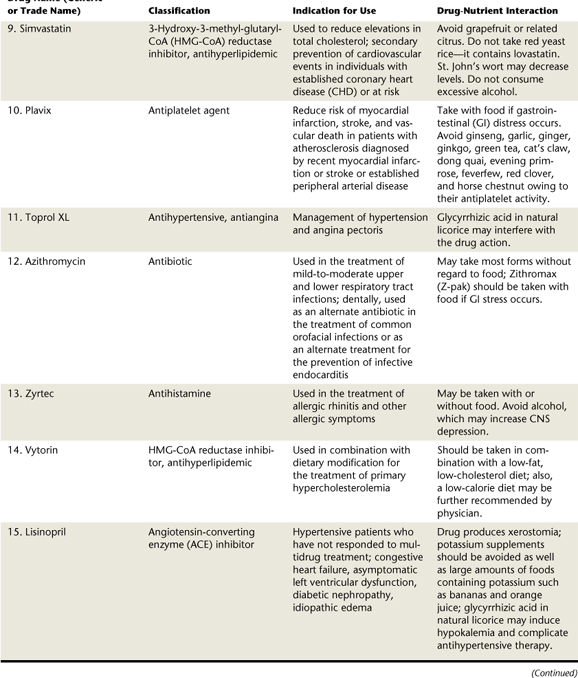

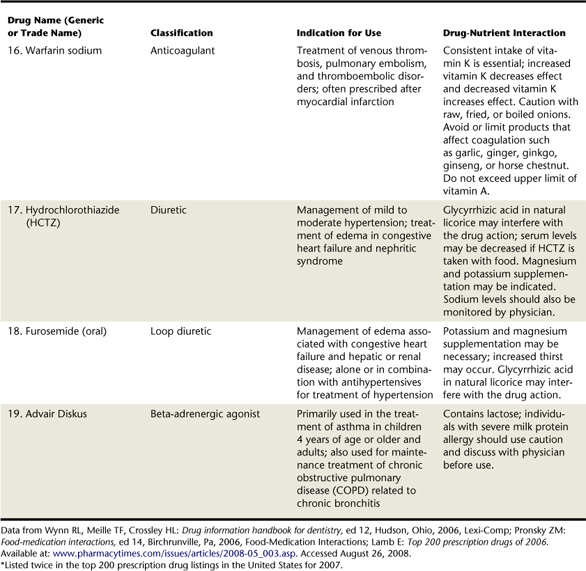

Assessment of the ingestion of prescription medications as well as vitamin and mineral supplements provides insight about such oral manifestations as xerostomia, lichenoid reactions, candidiasis, cheilitis, and glossitis. Dietary supplements and herbal products are routinely used by dental clients. Many of these products have effects on the oral tissues that may interfere with dental care, so it is essential that the dental hygienist update and review these nonprescription medications before treatment. Increased bleeding, elevated blood pressure, and delayed wound healing are potential effects that may occur.3 Table 33-2 lists drug and nutrient interactions of the 20 most commonly prescribed drugs in the United States. Table 33-3 lists side effects of herbal preparations commonly used by dental patients.

TABLE 33-3 Side Effects of Commonly Used Herbal Preparations

| Herb | Adverse Effect |

|---|---|

| Ephedra | Elevated blood pressure, tachycardia, risk of cerebrovascular accident, anxiety |

| Garlic | Increased bleeding |

| Gingko biloba | Immune suppression, delayed wound healing, liver toxicity |

| Ginseng | Increased bleeding, elevated blood pressure; may interact with epinephrine |

| Green tea | May cause increased bleeding |

| Kava | Synergistic effects of sedatives |

| St. John’s wort | Increased metabolism of other drugs, photosensitivity |

| Valerian root | Synergistic effects of sedatives |

Data from Wynn RL, Meiller TF, Crossley HL: Drug information handbook for dentistry, ed 12, Hudson, Ohio, 2006, Lexi-Comp.

DIETARY ASSESSMENT

Dietary assessment is the identification of current dietary practices and dietary requirements of the client. Dietary assessment includes frequency of food intake, methods of food preparation, cultural or religious dietary considerations, and exercise or activity levels; it reflects the Dietary Guidelines for Americans based on the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) new food guidance system titled “MyPyramid.”2 Types of dietary assessments include the dietary history, a food frequency questionnaire, and a computer dietary analysis.

Dietary History

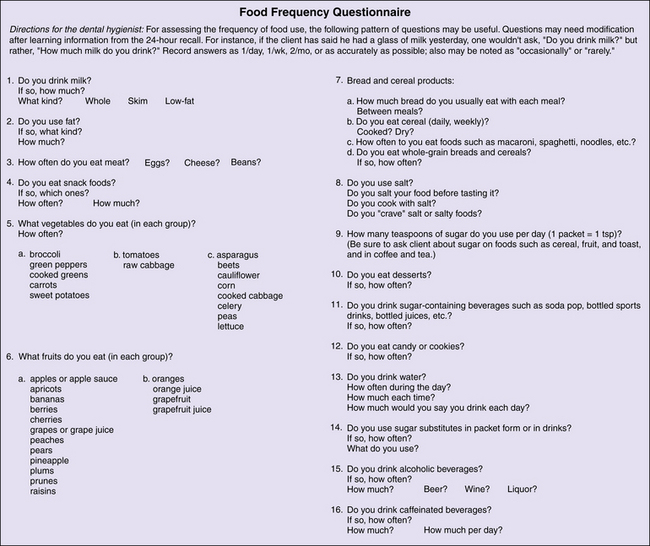

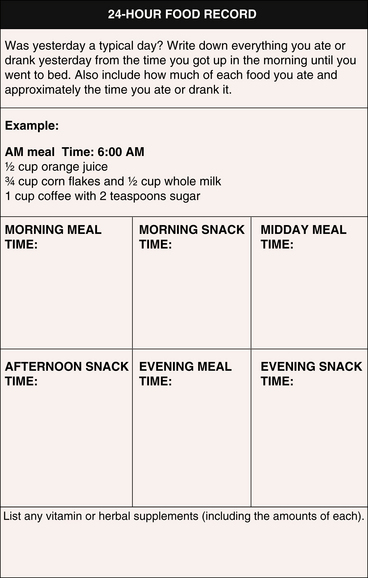

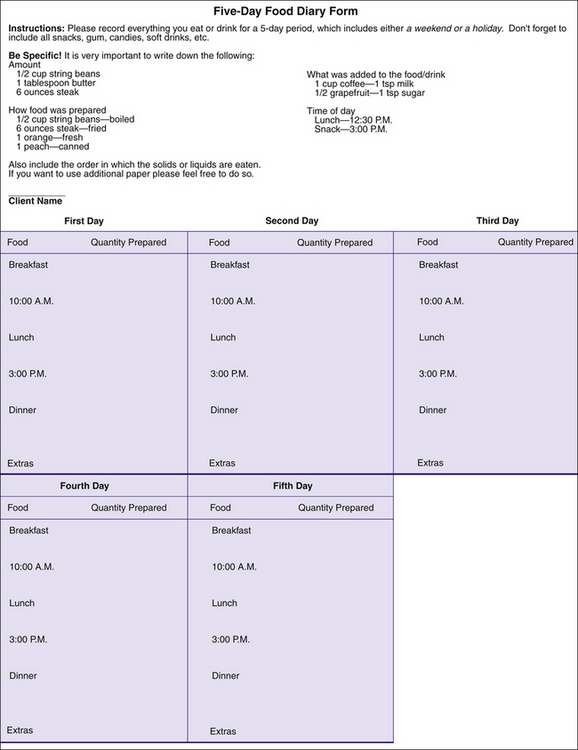

A dietary history may consist of a 24-hour food record (Figure 33-3), a food frequency questionnaire (Figure 33-4), or a 3-, 5-, or 7-day dietary history (Figure 33-5) in which the client records all foods and drinks consumed within the defined period. The dietary history determines a client’s usual intake over a period of time and is a screening tool to identify persons in need of nutritional counseling. A dietary history is obtained by interview or self-administered questionnaire.

Figure 33-3 Twenty-four–hour food record.

(Courtesy Dr. L. Boyd. Adapted from C. Palmer, Tufts University School of Dental Medicine, 1998; and from Nutrition Screening Initiative, Washington, DC, 1991.)

Figure 33-5 Five-day food diary form.

(Prepared by Lynn Tolle Watts, Gene W. Hirschfield School of Dental Hygiene, Old Dominion University. Adapted from Nizel AE, Papas AS: Nutrition in clinical dentistry, ed 3, St Louis, 1989, Saunders.)

Food models such as measuring cups and spoons help the client recall the amount of food consumed and should be used when possible. A 24-hour dietary history usually requires 15 to 20 minutes to complete and does not require the client to possess a long memory. This requires asking the client about all foods eaten in the previous 24 hours. If taken unannounced or with no prior indication, it minimizes the likelihood that the client will alter his or her diet. The 24-hour dietary recall, however, may not be representative of the person’s usual food intake. For most people, workdays, weekends, and holidays influence food intake considerably.

An advantage of the 24-hour dietary recall is that it serves as a teaching session. Accuracy as well as content can be discussed during the session, and the technique can be applied to a 3-, 5-, or 7-day dietary recall. The client and the dental hygienist determine the length of time the diet will be documented. The shorter the period, the less likely it is that the record will reveal usual eating patterns. A 24-hour dietary recall in combination with a food frequency questionnaire or a 3-, 5-, or 7-day dietary recall provides a more accurate account of the client’s regular intake.

Food Frequency Questionnaire

A food frequency questionnaire (see Figure 33-4) is similar to a 24-hour dietary recall but specifically asks the client to record foods most frequently eaten within a stated timeframe (e.g., as short as a day or as long as a month). The 24-hour dietary recall or food frequency questionnaire can be useful in assessing the cariogenic potential of the diet.

Computer Dietary Analysis

All dietary records have the potential for computer analysis. There are various programs available, and often the choice depends on the information obtained, its purpose, and the type of computer hardware available. Some programs are designed for research and provide everything from bar graphs to merging data for community-based programs. Most computer programs provide information on caloric intake as well as deficient or excess nutrient amounts. Some programs analyze sugar intake, including percentage of sugars in the diet (e.g., simple versus complex carbohydrates). MyPyramid Tracker is a simple, inexpensive option that can be used to assess the general nutrition of a client (see http://www.mypyramid.gov).

Evaluation of the Cariogenic Potential of the Diet

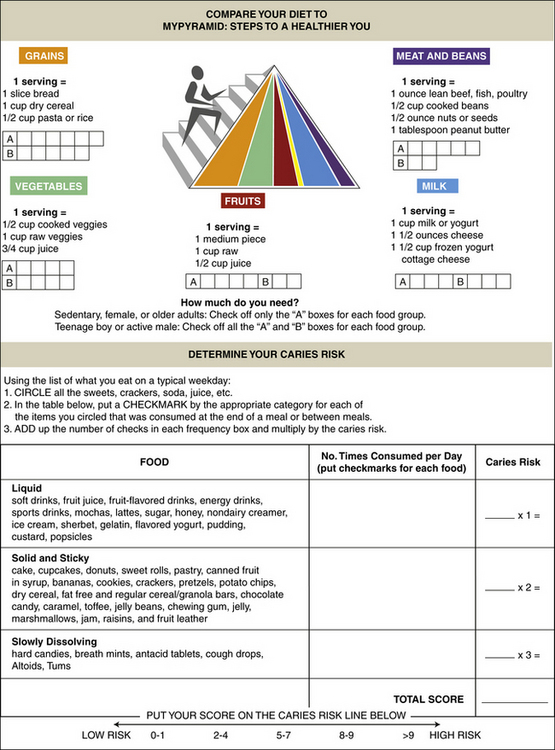

To assess the cariogenic potential of the diet, a 24-hour dietary recall (see Figure 33-3) is best used in the dental setting. However, this may not represent the client’s typical eating patterns so a 3-, 5-, or 7-day food record (see Figure 33-5) may be indicated for a more accurate account of the client’s diet. Type and amount of each food eaten, food preparation, and time of day the food was eaten are reported. The 24-hour dietary recall is then used to calculate the cariogenic potential of the diet. The sugar ingested reported on the 24-hour dietary form is categorized according to liquid sugars, solid and sticky sugars, and slowly dissolving sugars. The frequency with which each sugar is ingested is tallied and multiplied by 1, 2, or 3, depending on the sugar source (Figure 33-6). A dietary caries risk score of 9 or more indicates that the individual is in need of nutritional counseling to reduce the cariogenic potential of his or her diet.

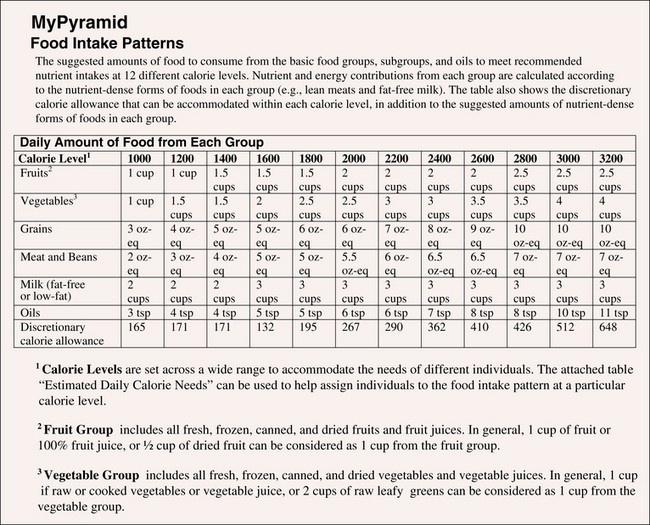

Evaluation of the Adequacy of the Diet Using MyPyramid

The same 24-hour dietary form used to calculate the cariogenic potential can be used to calculate the adequacy of the diet using the USDA MyPyramid (Figure 33-7). Individual caloric needs are determined based on age, gender, and activity level (Figure 33-8). Once energy needs are established, the dental hygienist can compare an individual’s intake to the specified amount recommended by MyPyramid (Figure 33-9) to assess the client’s dietary adequacy. Foods reported on the 24-hour dietary survey are placed into one of the pyramid food groups on the form. This information is useful in identifying individuals in need of general nutritional counseling. Nutritional requirements vary depending on the age, gender, and activity level of the individual.

Figure 33-7 U.S. Department of Agriculture MyPyramid.

(From U.S. Department of Agriculture 2005; www.mypyramid.gov.)

Evaluation of the 3-, 5-, or 7-Day Food Diary

Once an individual is identified for nutritional counseling, a more comprehensive dietary assessment must be completed. This assessment is accomplished by instructing the client to keep a 3-, 5-, or 7-day food diary and then evaluating the diary.

A food diary that includes a weekend is more likely to represent the individual’s normal eating habits. All foods consumed in a 24-hour period are recorded, including type of food eaten, manner in which it was prepared, exact amount of each food eaten, and time of day in which it was eaten (see Figure 33-3). The client is encouraged to adhere to his or her normal dietary regimen during the assessment period.

If the client’s 24-hour sugar-related caries risk score indicates the need for nutritional counseling, the dental hygienist may ask the client to complete a 3-, 5-, or 7-day food diary. On completion, the dental hygienist and client evaluate the diet for intake adequacy from the five food groups (see Figure 33-9). With the USDA MyPyramid, foods consumed are categorized into each of the five food groups. The average number of servings for a client’s diet based on a 3-, 5-, or 7-day period is compared with the recommended servings on MyPyramid (see Figure 33-6).

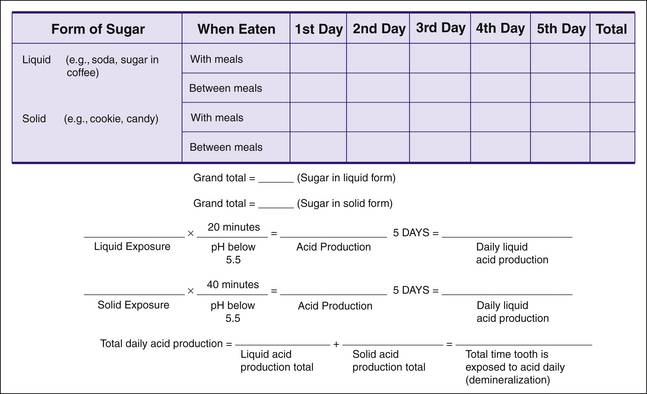

In addition, the cariogenic potential of the diet also may be further analyzed by calculating the amount of acid produced in the diet (Figure 33-10). Each sugar exposure, defined as any sweet or sugar-sweetened food or liquid, is circled in red. The total number of liquid and solid sugar exposures ingested over a 3-, 5-, or 7-day period is tallied and multiplied by the appropriate time interval. The number of liquid sugar exposures ingested over the period is multiplied by 20 minutes, and the number of solid sugar exposures ingested over the period is multiplied by 40 minutes. This resulting figure is divided by the number of days assessed to determine the amount of time daily that the teeth are subjected to an acid exposure. The total daily acid production is calculated by adding the daily acid production from both liquid and solid sugars. Sugars consumed at the same time are considered one acid exposure (e.g., ice cream and cake eaten for dessert equals one acid exposure). Sweet foods or liquids eaten 20 minutes apart are recorded as two acid exposures. Calculating the number of acid exposures further illustrates the cariogenic potential of the client’s diet.

NUTRITIONAL COUNSELING

Using the information obtained from the health history and dietary assessment, the dental hygiene clinician and client formulate a plan. Box 33-2 contains suggestions for nutritional counseling in the oral care setting.

BOX 33-2 Suggestions for Nutritional Counseling in the Oral Care Setting

Cultural Sensitivity

Culture should be a part of every assessment and counseling session (see Chapter 5). Different beliefs and lifestyles exist in society, and each should be accorded respect. The challenge for healthcare providers is to be culturally adaptable, to display cross-cultural communication skills, and to remain aware of nonverbal cues that are culturally based in order to establish a trusting relationship. There are many different population subgroups. These groups often have specific cultural, ethnic, or religious beliefs and practices to consider. Hindus and Buddhists advance a vegetarian lifestyle, and other religions adhere to different dietary restrictions. The Jewish religion includes dietary laws (the Kashrut) about the source, fitness, and preparation of foods and describes what types of foods may or may not be consumed together. Similarly, Muslims may follow Halal. Vegetarianism is a component of many cultural and religious philosophies but it is also a personal choice for many based on a desire for a healthier lifestyle.

Different ethnic groups also have dietary preferences and aversions. Although many internationals become acculturated, some still follow traditional dietary customs (Box 33-3). The culturally competent dental hygienist maintains knowledge of different cultures and remains sensitive to their beliefs and practices.

BOX 33-3 Examples of Dietary Preferences According to Some Cultural and Religious Beliefs

From Escott-Stump S, Earl R: Guidelines for dietary planning. In Mahan LK, Escott-Stump S, eds: Krause’s food and nutrition therapy, ed 12, St Louis, 2008, Saunders.

African American

Asian

Islam

Latino

Orthodox Judaism

Identifying Nutritional Deficiencies

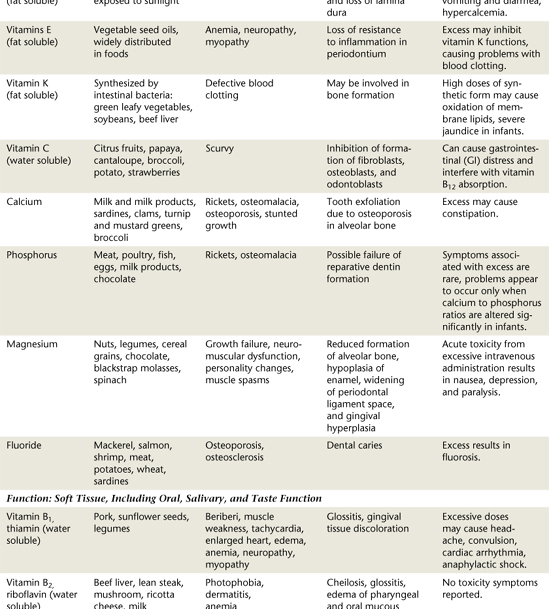

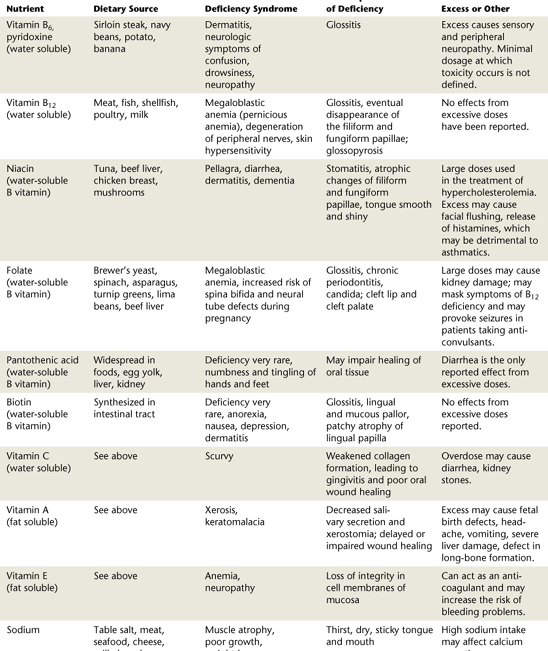

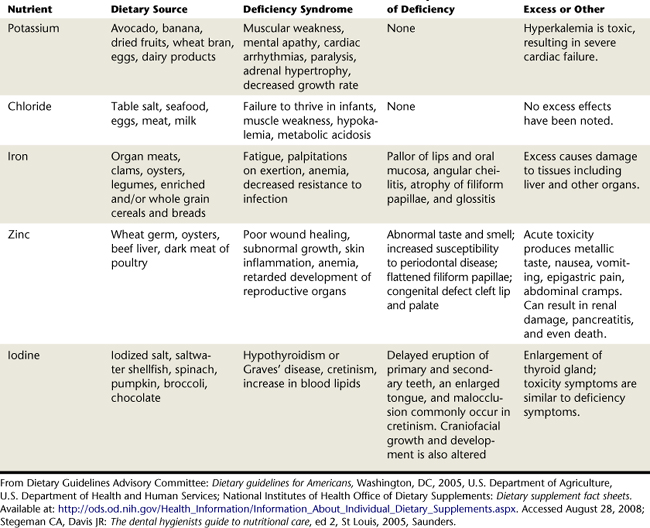

Nutritional problems manifest themselves both orally and systemically. A primary nutritional deficiency is caused by inadequate dietary intake of a nutrient (Table 33-4).

TABLE 33-4 Vitamins and Minerals Grouped According to Function, Including Sources, Human Deficiency and Excess Syndromes, and Oral Implications

Once identified, this type of deficiency can be corrected after dietary assessment followed by nutritional counseling that promotes proper selection and intake of nutrients. A secondary nutritional deficiency is caused by a systemic disorder that interferes with the ingestion, absorption, digestion, transport, and use of nutrients. This type of deficiency is more complex, and referrals to a physician and a nutritionist are necessary for treatment.

After potential dietary deficiencies and excesses are identified, the dental hygienist and client develop a dietary program. When dietary modifications are made, the following should be kept in mind:

Maintain overall nutritional adequacy by conforming to the USDA MyPyramid for at least the recommended number of servings from each of the food groups.

Maintain overall nutritional adequacy by conforming to the USDA MyPyramid for at least the recommended number of servings from each of the food groups. The diet should meet the body’s requirements for essential nutrients as generously as the diseased condition can tolerate.

The diet should meet the body’s requirements for essential nutrients as generously as the diseased condition can tolerate. The diet should accommodate the individual’s cultural and religious beliefs and practices, likes and dislikes, food habits, and other environmental factors, as long as they do not interfere with the objectives.

The diet should accommodate the individual’s cultural and religious beliefs and practices, likes and dislikes, food habits, and other environmental factors, as long as they do not interfere with the objectives.The use of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans in conjunction with the USDA MyPyramid guides the necessary dietary modifications. The USDA MyPyramid stresses balance among all the food groups (see Figures 33-6, 33-7, and 33-9). Serving sizes shown in Box 33-4 can assist the client in recording a detailed food diary.

BOX 33-4 Food Groups and Servings Sizes∗

∗ Serving sizes vary for individuals based on age, height, weight, pregnancy and nursing status, and activity level. One cup is approximately the size of one baseball; ½ cup is approximately ½ a baseball; ¼ cup is approximately one golfball; 3 oz of protein is approximately a deck of cards; 1 oz of cheese is approximately 4 dice. Refer to http://www.mypyramid.gov for further information.

The dental hygienist also tailors recommendations to the client’s lifestyle. Although most healthy clients have similar nutrient needs, stages within the life cycle may require special consideration, including pregnancy, infancy, childhood, and old age. Moreover, the dental hygienist considers clients’ special nutritional needs related to caries risk, periodontal and oral surgery, and osteoporosis risk.

NUTRITIONAL NEEDS DURING PREGNANCY

All stages of pregnancy require an increase in nutrients and energy intake, but the most relevant to fetal oral health may be the first and second trimesters when the development and calcification of teeth occur. Bone growth, which is equally important, occurs mainly in the second and third trimesters when most of the calcium essential for this process is transferred from mother to child. In most cases, the exception being an underweight or teenage pregnancy, the woman’s energy requirement increases by approximately 350 to 450 kilocalories a day. However, unlike energy needs, vitamin and mineral requirements nearly double. During pregnancy the woman may experience changes in taste and smell, food cravings, and food aversions that do not necessarily reflect real physiologic needs. These pregnancy-related experiences, along with varying levels of nausea, create a potential for nutrient imbalance. Fortunately, the developing fetus is usually not at risk during these short episodes because a healthy mother provides the essential nutrients from her own nutrient stores. However, a prolonged nutrient deficiency poses a problem.

The dental hygienist treating a pregnant woman reinforces the recommendations of the obstetrician. Reinforcement of the importance of eating nutrient-dense foods along with meticulous oral hygiene minimizes the occurrence of pregnancy-associated gingivitis, pregnancy granulomas, and giving birth to premature, low-birthweight infants. Prenatal nutrient supplements recommended by the client’s obstetrician ensure that the developing fetus receives adequate vitamins and minerals to promote healthy bone and tooth development.

NUTRITIONAL NEEDS DURING INFANCY AND CHILDHOOD

Nutrient intake and food choices during infancy and childhood influence growth patterns. Undernutrition, overnutrition, and improper nutrient amounts can set the pattern for a lifelong struggle with weight, developmental delays, or social discrimination.

Children often grow in spurts. Children are born with an innate sense of how much food they require. Parents who advocate completely finishing an entire meal may be causing the child to override his or her internal sense of satiety. The simplest advice is the provision of nutrient-dense foods, regular meal times, and the achievement of a balanced diet by offering a variety of foods from all of the food groups.

Unless a child has extenuating medical circumstances, children should not ingest significant amounts of alternative sweeteners. Children need calories for growth and development. Artificial sweeteners should not be part of the diet of infants or children under 2 years of age. Although the anticariogenicity of alternative sweeteners may offer a desirable choice to most parents, good oral hygiene care, fluoridation, and healthy snack choices can reduce dental caries risk. Examples of appropriate snacks for children are listed in Box 33-5.

BOX 33-5 Healthy Snack Ideas for Children and Adults

Adapted from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research: Snack smart for healthy teeth. Available at: www.nidcr.nih.gov/HealthInformation/DiseasesAndConditions/ChildrensOralHealth/SnackSmart. Accessed October 22, 2007.

The focus of nutritional counseling for children in the oral care setting is primarily caries control. In addition, the importance of vitamins and minerals responsible for bone growth should be included in a discussion with the child and caregiver. As children age, their preference for beverages often changes from milk and juices to carbonated beverages. Dairy products, some of the best sources of calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium, are essential for adequate bone and tooth formation. Replacing dairy products with carbonated beverages eliminates the main source of these nutrients. This change may adversely affect the bone growth and tooth development of children and teenagers.4

NUTRITIONAL NEEDS OF ELDERLY CLIENTS

Significant nutritional issues in the elderly include a reduced energy requirement, an increased protein requirement, and an increased need for vitamins and minerals including the antioxidant vitamins A, C, and E and minerals such as selenium and zinc (see Chapter 54). Most elderly people are not as active as younger people and therefore do not require the same amount of energy intake. The decrease in energy and increase in nutrient needs mean that the elderly client may need guidance in choosing nutrient-dense foods such as whole grains, breads, and pastas. Along with complex carbohydrates, fruits and vegetables are a natural source of the vitamins and minerals that promote tissue growth and regeneration. Because of a decrease in lean body per kilogram of body weight, elderly adults have a higher protein requirement. The current recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for protein for adults is 0.8 g/kg of body weight.5 A person who weighs 160 lb weighs approximately 73 kg and should have an intake of about 58 g of protein per day (58 g is equivalent to about 2 oz of protein). Protein intake in older adults should consist of approximately 12% to 14% of the total energy intake.6 As an example, approximately 150 to 225 calories of an average 1500-calorie intake is about 10% to 15% of the total energy intake and is the amount of calories that should come from protein sources in elderly adults.

A factor that affects nutrient intake is lack of dental insurance. Many elderly people may be unable to afford dental care. Periodontal disease and carious teeth can be painful and restrict the elderly individual’s ability to chew and swallow food. Hot or cold foods can aggravate oral disease conditions. In addition, crisp or fibrous foods that require significant force when biting or chewing also can cause pain. The aging process results in increased vulnerability to oral injury because of thinning of the oral tissues. For convenience, older adults may choose cakes, cookies, and breakfast cereals, which contribute to dental decay. Xerostomia also contributes to root caries and an inability to chew and swallow food adequately.

The consumption of nutrient-dense foods is essential to the elderly diet. Sources of high-quality protein such as eggs, dairy products, and well-cooked meats, chicken, and fish should be promoted as an important part of the diet. Protein also provides a good source of vitamin B12, often deficient in the elderly. The decrease of intrinsic factor, a protein that aids in the absorption of vitamin B12 in the stomach, makes intramuscular injections of the vitamin necessary.6 Vitamins A, C, and B6 can be obtained from a diet rich in cooked green vegetables and potatoes. Fresh fruit is also a good source of vitamins and minerals and can be tolerated if the fruit is ripe or peeled. Table 33-5 lists oral signs and symptoms of nutrient deficiencies in the elderly.

TABLE 33-5 Signs of Nutritional Deficiencies in the Elderly

| Clinical Signs | Possible Deficiency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Skin | ||

| Edema | Protein, thiamin | Common in protein calorie malnutrition as a result of aging |

| Poor tissue turgor | Water | Pellagra or hemochromatosis |

| Dermatitis | Protein | None |

| Keratosis | Vitamin A, essential fatty acids | None |

| Pigmentation | Niacin | Loss of lubrication or dryness of skin |

| Petechiae | Vitamin A, vitamin C | None |

| Xerosis | Essential fatty acids | None |

| Eyes | ||

| Dull, dry conjunctiva | Vitamin A | Can lead to other eye problems including blindness |

| Keratomalacia | Vitamin A | Usually results in blindness |

| Bitot’s spot | Vitamin A | Associated with night blindness |

| Corneal vascularization | Vitamin A | None |

| Photophobia | Riboflavin Zinc | Extreme sensitivity to light; individuals who suffer with migraines may experience this condition. Other eye problems such as night blindness may be present |

| Tongue | ||

| Magenta tongue | Riboflavin | None |

| Fissuring, raw | Niacin | May also be caused by food irritants, antibiotic administration, uremia |

| Glossitis | Pyridoxine, folacin, iron, vitamin B12 | Seen if anemia is not pronounced |

| Fiery red tongue | Folacin, vitamin B12 | None |

| Pale tongue | Iron, vitamin B12 | Seen in severe cases |

| Atrophic papillae | Riboflavin, niacin, iron | Also seen with ill-fitting dentures, food irritants, aging |

| Lips and Oral Structures | ||

| Angular fissures, scars, or stomatitis | B-complex, iron, protein, riboflavin | Also seen with ill-fitting dentures |

| Cheilosis | B6, iron, niacin, riboflavin, protein | Could also be a result of fungal infections |

| Ageusia dysgeusia | Zinc | Certain conditions and medications can contribute; also seen with ill-fitting dentures |

| Swollen, spongy, bleeding gums | Vitamin C | Also associated with altered sense of smell, if not edentulous |

Finally, guidance should be given to the elderly to achieve optimum nutrition. Referral to a registered dietitian may be indicated. Community-based services such as Meals on Wheels, congregate meal sites, and shopping assistance provide an opportunity for socialization and assistance for those who are disabled or who lack transportation. Also, modifications applied to oral hygiene aids for people with manual dexterity problems can be applied to eating utensils to increase the likelihood of adequate nutritional intake.

NUTRITIONAL NEEDS OF CLIENTS WITH DENTAL CARIES RISK

Nutritional counseling for dental caries prevention must emphasize decreasing the frequency with which sugar is consumed and replacing cariogenic foods with nutritionally sound foods. Although sugar consumption is an important factor in caries risk assessment7,8 (see Chapter 16), the following three factors must be present for dental caries to occur:

Nutritional counseling for dental caries prevention targets the elimination or reduction of fermentable carbohydrates from the diet. Frequent consumption of fermentable carbohydrates subjects the tooth enamel to repeated acid exposures. The demineralization process weakens the tooth and leads to the formation of dental caries. (See Chapter 14 for types of caries and Chapter 16 for a review of the caries process.) Table 33-6 illustrates the relative cariogenicity of certain foods. Foods with a cariogenic potential index in the 0.0 to 0.4 range are considered to have a low cariogenic potential or are noncariogenic. This information can be useful for suggesting foods and strategies for reducing the cariogenic potential of an individual’s diet (Box 33-6).

TABLE 33-6 Current Estimates of Cariogenicities and Cariogenic Potential Index

| Food | Cariogenic Potential Index (CPI) |

|---|---|

| Low Cariogenic Potential | |

| Gelatin dessert | 0.4 |

| Corn chips | 0.4 |

| Peanuts | 0.4 |

| Bologna | 0.4 |

| Yogurt | 0.4 |

| Moderate to High Cariogenic Potential | |

| Pretzels | 0.5 |

| Potato chips | 0.6 |

| Saltines | 0.6 |

| Natural snack (trail mix) | 0.6 |

| Rye crackers | 0.7 |

| Doughnut | 0.7 |

| Milk chocolate | 0.8 |

| Graham crackers | 0.8 |

| Sponge cake with filling | 0.8 |

| Bread | 0.9 |

| Sucrose | 1.0 |

| Granola cereal | 1.0 |

| French fries | 1.1 |

| Bananas | 1.1 |

| Cupcakes | 1.2 |

| Raisins | 1.2 |

Adapted from Mundorff SA, Featherstone JBD, Bibby BG: Cariogenic potential of foods. I. Caries in the rat model, Caries Res 24:344, 1990.

BOX 33-6 Dietary Recommendations for the Reduction of Dental Caries

NUTRITIONAL NEEDS OF CLIENTS UNDERGOING SURGERY

In a healthy adult, creation of new proteins and breakdown of existing proteins closely balance one another. Any change in health status can cause a metabolic change in protein status. Many metabolic changes occur during the postsurgical period, including increased breakdown of stored body nutrients (e.g., protein and minerals from the body stores are used to remodel and repair oral structures). Protein breakdown most often exceeds synthesis. Other metabolic factors combine to cause a further increase in the breakdown of lean body tissues with a resultant weight loss. Depletion of protein mass is important because the body has no expendable protein reserves; therefore any loss of protein adversely affects body function, leading to increased loss of lean body mass and the subsequent weight loss through metabolic processes. Periodontal and oral and maxillofacial surgical clients are often unable to consume an adequate amount of recommended nutrients owing to loss of function. To minimize loss of lean body mass and to promote healing and overall health, clients should be instructed in proper postsurgical nutritional rehabilitation. Presurgical nutrition education includes the following:

Discussion of the client’s present status and recommended ranges for prevention of loss of lean body mass

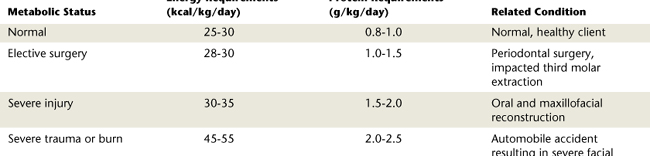

Discussion of the client’s present status and recommended ranges for prevention of loss of lean body massCalculations using the formula for BEE multiplied by an AF provide an estimation of nutritional requirements. Postsurgically the number will be multiplied by an IF to determine the increase in caloric needs. At this time the RDA for daily protein needs for adults is set at 0.8 g/kg of body weight. Postsurgically the increase in protein requirement can be as much as 1.2 to 1.5 g/kg of body weight for mild to moderate stress. Protein needs may increase up to 2.5 g/kg of body weight in conditions such as burns, severe trauma, or presence of a fistula.6 Table 33-7 illustrates the average energy and protein requirements based on metabolic status.

In addition to caloric and protein requirement increases, there may also be an increase in select nutrient needs. It makes sense that B vitamin requirements would increase in conjunction with the increase in caloric intake. The primary function of the B vitamins is as a cofactor in energy metabolism. Catabolism and loss of lean body mass increase the loss of potassium, magnesium, phosphorus, and zinc. Fluid and electrolytes should be provided to maintain adequate urine output and normal serum electrolytes. The tendency is to prescribe a nutritional supplement in the form of a tablet, but it is always preferable to obtain nutrients through a food source. In cases in which the client is unable to adequately ingest the required nutrients, however, a liquid form of supplemental nutrition such as Ensure or Boost may be acceptable. If supplemental liquid nutrition is indicated, clients are educated on the high sugar content and the need for meticulous oral hygiene.

A practical education program for clients is accomplished using the USDA MyPyramid and Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Quick calculations and charts are used as visual aids to client education. Individualized meal plans that incorporate caloric, protein, and other suggested nutrient needs postsurgically are an excellent resource in the private practice setting. Often it is easier to obtain compliance when clients are presented with an actual list of foods or meal plans to follow. The dental hygiene clinician can provide only basic recommendations. Referral to a registered dietitian is indicated to develop a comprehensive meal plan that meets individual needs. The American Dietetic Association is an exceptional resource for examples of full liquid and mechanical soft diets designed to provide optimum calories and nutrients for surgical patients. It is also a great source for locating a dietitian in the local area for referrals (see http://www.eatright.org).

NUTRITIONAL NEEDS OF CLIENTS WITH OSTEOPOROSIS4,6,9

Many factors affect mineralization of bone in the human body, including metabolic and dietary interactions and certain disease states. Improper bone mineralization can affect the dentition. Although several vitamins and minerals ultimately contribute to bone and tooth formation and preservation, calcium, phosphorus, and vitamin D directly support these processes. Calcium can be found throughout the body in bone, serum, and tissues. Approximately 98% of the calcium present in the human body is contained in bone and teeth. The balance of serum calcium is important in that it often causes the release or deposit of calcium from hard body tissues.

Phosphorus is equally important to bone growth and preservation. Approximately 85% of the phosphorus in the human body is found in combination with calcium in hydroxyapatite crystals of bones and teeth. Calcium and phosphorus are important components of bones and teeth, but vitamin D directs the use of these minerals in the body. The interaction of calcium, phosphorus, and vitamin D is required for adequate maintenance of bone growth and mineralization.

Osteopenia, a loss of mineralized bone tissue, regardless of its cause, is considered a precursor to osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by low bone mass, microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue leading to enhanced bone fragility, and consequent increase in fracture risk. Osteoporosis has become significant as a disease owing to its relationship to mortality, morbidity, quality of life, and medical expense worldwide. Osteoporosis causes more than 1.5 million fractures annually in the United States alone. Vertebral, wrist, and hip fractures are responsible for much of the mortality and morbidity of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is a leading cause of disability in the elderly. Box 33-7 identifies risk factors associated with osteoporosis. Osteoporosis may be a risk factor or risk indicator for periodontal disease, for tooth loss preceding dental implants, and in the prognosis of periodontal therapy (see Chapter 53).

When discussing the control of osteoporosis, the nutrient mentioned most often is calcium. Although important throughout the life cycle, this nutrient is especially crucial during the peak bone-forming years. The RDA for calcium is 1000 mg for young adults 19 to 30 years of age. It increases to 1200 mg for individuals 50 and older. It has been found that a calcium intake of at least the RDA can slow or prevent age-related bone loss and reduce the risk of fractures in postmenopausal women and the elderly.

A thorough health history, oral screening (intraoral exam, periodontal charting, radiographs), and dietary analysis will help to identify clients at risk for osteoporosis (see Chapter 53). These individuals need to be encouraged to consume at least 2 cups of calcium food sources daily. The preferred calcium source is dairy products and foods fortified with calcium. Calcium bioavailability from dairy foods is excellent, especially when consumed with a meal (Box 33-8). Emphasis also needs to be on vitamin D to promote optimal calcium absorption. Table 33-8 provides a listing of the minerals and vitamins essential for calcified structures. For individuals who have inadequate intake of dairy, a calcium supplement may be indicated. Dose should be taken in halves to ensure proper absorption (e.g., 500 to 600 mg taken twice daily). For an individual diagnosed with osteoporosis or at risk, referral to a physician or a dietitian may be recommended to make sure calcium needs are being met.

TABLE 33-8 Vitamins and Minerals Required for Calcified Structures

| Vitamin or Mineral | Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) (for Adults) | Food Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A (fat soluble) | 900 μg (men); 700 μg (women) | |

| Vitamin D (fat soluble) | Adequate intake (AI) is 5 μg in the absence of sunlight; no set RDA | Sunshine, fortified milk |

| Vitamin E (fat soluble) | 15 μg | Sweet potato, shrimp, sunflower seeds, canola oil, corn oil |

| Vitamin K (fat soluble) | AI is 120 μg (men); 90 μg (women) | Produced in the large intestine; cabbage, spinach, cauliflower, milk, eggs, garbanzo beans, beef liver |

| Vitamin C (water soluble) | 90 mg (men)/75 mg (women) | Citrus fruits such as oranges, grapefruit; vegetables such as potatoes, green pepper, broccoli, and Brussels sprouts |

| Calcium | AI is 1000 mg; no set RDA | Dairy products such as milk, cheese, fortified soy milk; tofu, sardines, almonds. Vegetables such as broccoli, turnip greens, cauliflower, kale, bok choy |

| Phosphorus | 700 mg | Dairy products such as milk, cottage cheese; meat and fish products such as salmon, sirloin steak |

| Magnesium | 420 mg (men); 320 mg (women) | Vegetables such as black-eyed peas, spinach, baked potato. Other sources include oysters, dried figs, sunflower seeds |

| Fluoride | 4 mg (men); 3 mg (women) | Fluoridated water, fluoridated dental products, teas, marine fish |

| Copper | 900 μg | Shellfish, liver, nuts, seeds, legumes, whole-grain products |

| Manganese | Nuts, legumes, whole-grain cereals, leafy vegetables | |

| Molybdenum | 45 μg | Legumes, whole-grain products, nuts |

| Selenium | 70 μg (men)/55 μg (women) | Animal products such as meats and shellfish. Vegetables and grains grown in selenium-rich soil (common in the United States) |

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Explain that a diet rich in nutrient-dense foods promotes oral health and overall health and prevents osteopenia and osteoporosis in later life.

Explain that a diet rich in nutrient-dense foods promotes oral health and overall health and prevents osteopenia and osteoporosis in later life. Emphasize that decreasing the amount and frequency of simple sugars consumed promotes oral health, weight management, and systemic health.

Emphasize that decreasing the amount and frequency of simple sugars consumed promotes oral health, weight management, and systemic health. Explain that nutrient needs change during the life cycle and at times of stress such as periodontal and oral surgery.

Explain that nutrient needs change during the life cycle and at times of stress such as periodontal and oral surgery. Explain recommended dietary allowances (RDAs), nutrition labels on foods purchased, Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture MyPyramid as the basis for appropriate food choices.

Explain recommended dietary allowances (RDAs), nutrition labels on foods purchased, Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture MyPyramid as the basis for appropriate food choices.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Dental hygienists should refrain from practicing nutrition assessment or counseling that is beyond the scope of their practice (e.g., weight management, development of comprehensive dietary plans, metabolic disease control, eating disorders).

Dental hygienists should refrain from practicing nutrition assessment or counseling that is beyond the scope of their practice (e.g., weight management, development of comprehensive dietary plans, metabolic disease control, eating disorders). Refer signs of nutrition-related diseases or deficiencies to a physician or licensed nutrition professional.

Refer signs of nutrition-related diseases or deficiencies to a physician or licensed nutrition professional.KEY CONCEPTS

Dietary assessment is the identification of the client's current dietary practices and dietary requirements. Dietary assessment includes a dietary history that may be gathered through a 1-, 3-, 5-, or 7-day recording of food intake. Dietary assessment may provide clues to overall health through analysis of nutrient content.

Dietary assessment is the identification of the client's current dietary practices and dietary requirements. Dietary assessment includes a dietary history that may be gathered through a 1-, 3-, 5-, or 7-day recording of food intake. Dietary assessment may provide clues to overall health through analysis of nutrient content. Key factors influence an individual's food selection, including age, gender, ethnicity and culture, income, educational level, and lifestyle.

Key factors influence an individual's food selection, including age, gender, ethnicity and culture, income, educational level, and lifestyle. Pregnancy, infancy, childhood, and aging require special consideration when the dental hygienist counsels clients or their caregivers on nutrition.

Pregnancy, infancy, childhood, and aging require special consideration when the dental hygienist counsels clients or their caregivers on nutrition.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

Three scenarios present clients with specific nutritional needs. Read each case and prepare a complete dental hygiene care plan for each (see useful calculations for nutrition assessment at end of scenario). Do you agree or disagree with the nutritional plans presented? Is there anything you would do differently?

SCENARIO 33-1

SCENARIO 33-1

ORAL AND MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY CLIENT

Health History: Family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus. In the past client has had abnormal glucose levels but recently has tested normal. Was considerably overweight and has worked hard to lose about 25 lb; cholesterol level is somewhere around 220.

Pharmacologic History: Allergic to penicillin. Postsurgically, Mr. Rodriguez will be taking Lortab for postoperative pain on a PRN basis and erythromycin for about 1 week postoperatively.

Dental History: Intraoral and extraoral examination findings show probing depths of 4 to 5 mm throughout his mouth. Moderate amounts of plaque biofilm and moderate to heavy bleeding in the molar areas. No carious lesions. Currently undergoing orthodontic treatment and can expect to have limited use of his teeth and jaws for approximately 6 weeks postsurgically. Has had trouble keeping his teeth clean since his orthodontic appliances were placed. Mr. Rodriguez's surgeon has said that he probably won't have to worry about weight loss postsurgically as he could stand to lose a few more pounds. However, the surgeon mentioned that Mr. Rodriguez should try to eat more protein foods to support healing.

Chief Complaint: “I am scheduled to have oral surgery that will move my jaw and relieve my jaw pain. I want my surgery to go well so that I heal quickly.”

Dietary Assessment: After completion of a 24-hour dietary history, the following are noted:

Mr. Rodriguez's 24-Hour Dietary History:

Nutritional Counseling Plan: Recommendations for Mr. Rodriguez are as follows:

SCENARIO 33-2

SCENARIO 33-2

CLIENT WITH OSTEOPOROSIS

Health History: Client underwent early menopause, is lactose intolerant, and is currently being treated for irritable bowel disease.

Pharmacologic History: Medications include steroid treatment for her bowel problems and estrogen replacement

Dental History: Several carious areas. Radiologic examination shows moderate bone loss of the supporting structures and within her jaws. Suspect osteoporosis. Will discuss this with the dentist. After dental treatment Ms. Tsing will be referred to her physician for evaluation and treatment of suspected osteoporosis.

Chief Complaint: “My teeth are hurting me.”

Dietary Assessment: Food frequency questionnaire shows that Ms. Tsing follows a typical Asian dietary pattern with fish and tofu as the main sources of protein. Eats a variety of vegetables including green leafy vegetables such as spinach and green leaf lettuce, bean sprouts, bok choy, broccoli, and carrots. Does not consume any dairy products owing to her lactose intolerance. Drinks tea. Loves sweets and desserts and consumes candy regularly. Diet consists of approximately 20% fat, 10% protein, and 70% carbohydrate.

Social History: Client does not exercise and rarely goes outside during the day in an effort to avoid the sun and its damaging effects. Worked as a seamstress for many years but is now retired. Belongs to an informal social women's group and occasionally has the opportunity to meet for walks at the local mall.

SCENARIO 33-3

SCENARIO 33-3

CLIENT WITH RAMPANT DENTAL CARIES

Health History: Client has experienced several childhood illnesses, including chicken pox, measles, and mumps, and frequent sore throats and common cold symptoms. Client was injured on the school playground at age 6 years and underwent treatment for fractures of the right leg and arm.

Pharmacologic History: Because of frequent cold symptoms and sore throats, client regularly ingests over-the-counter cough drops. Her favorite flavors are cherry and honey lemon. These cough drops are not sugar free.

Dental History: Because of her health history and subsequent treatment for illness and injury, Kathleen's parents have not taken her to the dentist often in an effort to avoid “overtraumatizing” her. Intraoral examination reveals rampant caries of remaining primary teeth with the largest lesions in the molar area. Radiographic examination shows decay throughout the mouth. Permanent tooth development appears to be normal. Erupted molars have incipient lesions with some surfaces requiring Class I restorations at this time.

Chief Complaint: “My friends at school make fun of my teeth because they are black. Sometimes it's hard to chew.” Client does not appear to be experiencing pain at this time.

Dietary History: Food frequency questionnaire indicates that client has a high intake of foods containing added sugars and appearing in the moderate- to high-cariogenic potential category. On MyPyramid, client can point out most foods in her diet. Client indicates that she adds sugar to her breakfast cereals and on top of the fruit she eats with lunch. Client loves raisins and dried fruit as a snack. She keeps a little bag in her desk at school in case she gets hungry during the day. Client's favorite snack is a bowl of chocolate ice cream, which she has every night before bed. Client drinks regular Coca Cola with each meal except breakfast. Friends eat candy bars, but Kathleen prefers gummy bears, Dots, Sour Patch Kids, and other sticky fruit candies.

Social History: Client is the youngest child in a family of six. Parents both work outside the home. Family status is middle class with occasional financial challenges because of large family. Client stays after school until picked up by older siblings. Because of work and social obligations, parents have left most of the childcare responsibilities to older siblings. Previous injuries and chronic illnesses have promoted special reward system at home of sweet desserts and ice cream before bed. Limited parental supervision has caused client to adopt diet and habits of older siblings who enjoy regular Coca Cola with meals instead of milk. Client appears to understand the importance of a healthy diet and appears receptive to adjusting habits “as long as my parents say it's OK.”

1. U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Dietary guidelines for Americans, ed 6, Washington, DC, 2005, U.S. Government Printing Office. Available at: www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/document. Accessed December 12, 2008.

2. U.S. Department of Agriculture: MyPyramid. Available at: http://www.mypyramid.gov Accessed December 8, 2008.

3. DeRossi S.S., Hersh E.V. A review of adverse oral reactions to systemic medications. Gen Dent. 2006;54:131.

4. Kaye E.K. Bone health and oral health. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:616.

5. Mahan L.K., Escott-Stump S., editors. Krause’s food and nutrition therapy, ed 12, St Louis: Saunders, 2008.

6. Committee on Dietary Allowances. Recommended dietary allowances, ed 10. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1989.

7. Gustafsson B.E., Quensel C.E., Lanke L.S., et al. The Vipeholm dental caries study: the effects of different levels of carbohydrate intake on caries activity in 436 individuals observed for five years. Acta Odontol Scand. 1954;11:232.

8. Screenby L.M. Sugar availability, sugar consumption and dental caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1982;10:1.

9. Mulligan R., Sobel S. Osteoporosis: diagnostic testing, interpretation, and correlations with oral health—implications for dentistry. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49:463.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..