CHAPTER 7 Infection Control

STANDARD PRECAUTIONS AND BASIC INFECTION-CONTROL CONCEPTS

Infection control refers to a comprehensive, systematic program that, when applied, prevents the transmission of infectious agents among persons who are in direct or indirect contact with the healthcare environment. The goal of infection control is to create and maintain a safe clinical environment to eliminate the potential for disease transmission from clinician to client, client to clinician, or client to client. Infection control relies on the premise that transmission occurs when an infectious agent has a portal of entry to a susceptible host.

Although the challenge remains to meet the comprehensive needs of diverse clients, the premise of standard precautions goes beyond the individual to eliminate the potential for transfer of disease-causing microorganisms during the delivery of oral health services. Standard precautions are a set of infection-control precautions that when used consistently ensure the safe delivery of oral healthcare. Human needs theory relates directly to universal precautions in the following ways:

Universality of human needs transcends all ages, cultures, nationalities, genders, sexual orientation, behaviors, and the like. Standard precautions, the practice of infection control, rely on the universal application of precautions in the treatment of all clients regardless of the individual or the client’s infectious disease status.

Universality of human needs transcends all ages, cultures, nationalities, genders, sexual orientation, behaviors, and the like. Standard precautions, the practice of infection control, rely on the universal application of precautions in the treatment of all clients regardless of the individual or the client’s infectious disease status. A link exists between human needs and health as defined by the World Health Organization. The World Health Organization defines health as “the extent to which an individual or group is able, on the one hand, to realize aspirations and satisfy needs and, on the other hand, to change and cope with the environment.” Infection control is truly the ability to change and cope with the environment.

A link exists between human needs and health as defined by the World Health Organization. The World Health Organization defines health as “the extent to which an individual or group is able, on the one hand, to realize aspirations and satisfy needs and, on the other hand, to change and cope with the environment.” Infection control is truly the ability to change and cope with the environment. Of all the human needs, infection control is most applicable to protection from health risks. Although infection-control practices cannot reduce unintended harm from the care itself, it can prevent unintended harm to the dental hygienist, client, and other staff. Protection from health risks begins with the client (client assessment), but standard precautions do not depend on the health, dental, and pharmacologic histories, because clients may not always be aware of their health risks, conditions, or emerging concerns. Standard precautions treat all clients as potentially harboring disease-producing organisms and apply evidence-based protocols to reduce the potential harm associated with these organisms. Standard precautions apply to all body fluids, excretions, and secretions with the exception of sweat. The hygienist uses client assessment findings to make decisions about appropriate interventions. With infection control the hygienist considers procedures and behaviors indicated to reduce risk of disease transmission.

Of all the human needs, infection control is most applicable to protection from health risks. Although infection-control practices cannot reduce unintended harm from the care itself, it can prevent unintended harm to the dental hygienist, client, and other staff. Protection from health risks begins with the client (client assessment), but standard precautions do not depend on the health, dental, and pharmacologic histories, because clients may not always be aware of their health risks, conditions, or emerging concerns. Standard precautions treat all clients as potentially harboring disease-producing organisms and apply evidence-based protocols to reduce the potential harm associated with these organisms. Standard precautions apply to all body fluids, excretions, and secretions with the exception of sweat. The hygienist uses client assessment findings to make decisions about appropriate interventions. With infection control the hygienist considers procedures and behaviors indicated to reduce risk of disease transmission. Freedom from fear and stress is another human need related to standard precautions. People need to feel safe in the healthcare environment. Part of this safety comes from the immediate recognition of applied infection-control principles.

Freedom from fear and stress is another human need related to standard precautions. People need to feel safe in the healthcare environment. Part of this safety comes from the immediate recognition of applied infection-control principles. Many human needs are fulfilled by a variety of client services and policies, but the need for conceptualization and problem solving underlies every behavior relative to client care. There must be evidence of the use of sound and appropriate infection-control practices, and there must be an explanation of rationales before care is delivered. Clients need to realize that their safety is paramount; this instills the belief that subsequent care is most appropriate, as well.

Many human needs are fulfilled by a variety of client services and policies, but the need for conceptualization and problem solving underlies every behavior relative to client care. There must be evidence of the use of sound and appropriate infection-control practices, and there must be an explanation of rationales before care is delivered. Clients need to realize that their safety is paramount; this instills the belief that subsequent care is most appropriate, as well.Infection control begins with assessment of the healthcare delivery environment, ensuring it is free from infectious hazards. Dental hygienists conduct infection-control assessment based on the care plan as follows:

INFECTION-CONTROL MODEL

A model of infection control parallels the model of dental hygiene care. For example, clients must understand the selection and use of infection-control procedures and the protective outcomes. However, the infection-control model differs from the traditional client care model in that it focuses on tasks and procedures rather than on the client.

Scrutinizing each individual health history will not determine the degree of risk for disease transmission. Dental procedures generate widely variant amounts of body fluids, and the dental instruments used vary in their tendency to release body fluids. Therefore infection control is procedurally based, not client based. Cognitive goals in the infection-control model relate to the explanation of infection control, the protective intent of infection control, and its benchmark status as a standard of care. Effective goals in the infection-control model are designed to change a client’s attitude in a positive manner and reduce fear or anxiety associated with dental hygiene care. The client must see infection control as protective, not punitive.

GOVERNMENT AGENCIES AND INFECTION CONTROL

Two agencies of the U.S. government play key roles in infection control. Guidelines and regulations developed by both of these agencies have established national standards for infection control.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is one of eight federal public health agencies within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Its mission is to promote health and quality of life by preventing and controlling disease, injury, and disability. The CDC develops guidelines and recommendations; among these are infection-control recommendations for healthcare settings. The CDC is not a regulatory agency and does not enforce the guidelines it develops.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), within the U.S. Department of Labor, serves to protect persons by ensuring a safe and healthy workplace. OSHA enforces workplace safety regulations, including those for infection control in healthcare settings.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also provide regulatory oversight in the area of products used in the application of infection-control procedures. The FDA regulatory mission is to do the following:

Promote and protect the public health by helping safe and effective products reach the market in a timely way

Promote and protect the public health by helping safe and effective products reach the market in a timely wayThe FDA’s regulatory approaches are as varied as the products it regulates. Some products, such as new drugs and complex medical devices, must be proven safe and effective before companies can put them on the market. Other products, such as x-ray machines and medical sterilizers, must measure up to performance standards.

The FDA regulates all medical devices, from very simple items like tongue depressors and thermometers to very complex technologies such as heart pacemakers and dialysis machines. Different levels of approval are required based on the complexity and use of products or devices. These differences are dictated by the laws we enforce and the relative risks that the products pose to consumers.

The EPA’s regulatory mission is to protect human health and the environment. Since 1970, the EPA has been working for a cleaner, healthier environment for the American people. Areas of the EPA’s regulatory authority that affect infection control include the following:

STANDARD OF CARE

Standard of care is the level of care that a reasonably prudent practitioner would exercise. It is not a maximum standard; rather it is the minimum level acceptable in all aspects of client care. Infection-control regulations, evidence-based guidelines, government agencies, licensing boards, other dental practitioners, and expert opinion all determine the standard of care for appropriate infection-control practices in dentistry. The standard of care provides a basis from which to promote excellence and encourage performance improvement to develop and implement best practices.

The goal of infection control is to prevent healthcare-associated infections among clients and injuries and illnesses in dental healthcare personnel (DHCP). Dental clients and DHCP can be exposed to pathogenic (disease-producing) microorganisms. Human pathogens include cytomegalovirus (CMV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB), staphylococci, streptococci, and other viruses and bacteria that colonize or infect the oral cavity and respiratory tract. These organisms can be transmitted in dental healthcare settings by the following means:

Indirect contact with contaminated objects (e.g., instruments, equipment, or environmental surfaces)

Indirect contact with contaminated objects (e.g., instruments, equipment, or environmental surfaces) Contact of conjunctiva, nasal membranes, or oral mucosa with droplets (e.g., spatter) that contain microorganisms generated from an infected person and propelled a short distance (e.g., by coughing, sneezing, or talking)

Contact of conjunctiva, nasal membranes, or oral mucosa with droplets (e.g., spatter) that contain microorganisms generated from an infected person and propelled a short distance (e.g., by coughing, sneezing, or talking)Infection through any of these routes requires that all of the following conditions be present:

Occurrence of these events provides the chain of infection. Effective infection-control strategies prevent disease transmission by interrupting one or more links in the chain.

FOUR PRINCIPLES OF INFECTION CONTROL

The CDC identifies four principles of infection control that help protect the health of all individuals in the dental environment.

Principle 1: Take Action to Stay Healthy

All persons must take positive steps to maintain their own health. This is especially true for persons working in any healthcare setting, including DHCP.

Principle 2: Avoid Contact with Blood and Other Infectious Body Substances

Avoid contact with blood and other potentially infectious body fluids by using a combination of safe work practices and behaviors and engineering controls. Infection-prevention and infection-control measures include:

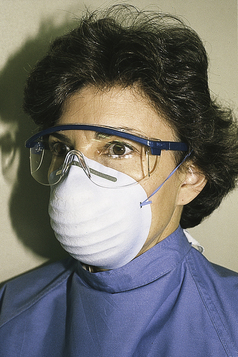

Effective use of personal protective equipment (PPE) (e.g., gloves, face masks, protective eyewear, protective gowns) (Figure 7-1)

Effective use of personal protective equipment (PPE) (e.g., gloves, face masks, protective eyewear, protective gowns) (Figure 7-1)Principle 3: Make Client Care Items (Dental Instruments, Devices, and Equipment) Safe for Use

Instruments, devices, and equipment used to provide direct client care become contaminated. Appropriate infection-control measures must be taken to prevent transmission of infectious agents from client to client through these contaminated items. Methods of appropriate infection-control measures include the following:

Principle 4: Limit the Spread of Blood and Other Infectious Body Substances

Although environmental surfaces and waste products are less likely to provide an efficient mechanism for transmission of infectious agents, they are subject to contamination in oral healthcare settings. Examples of infection-control measures to limit the spread of contamination include:

STRATEGIES TO PREVENT DISEASE TRANSMISSION: TAKE ACTION TO STAY HEALTHY

A basic strategy for healthcare personnel (HCP) to take action to stay healthy is to develop a personnel health program based on the CDC 2003 dental infection-control guidelines, including medical evaluation, health and safety education and training, management of work-related illness and postexposure management, counseling, work restrictions, and immunization.

Immunizations for Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

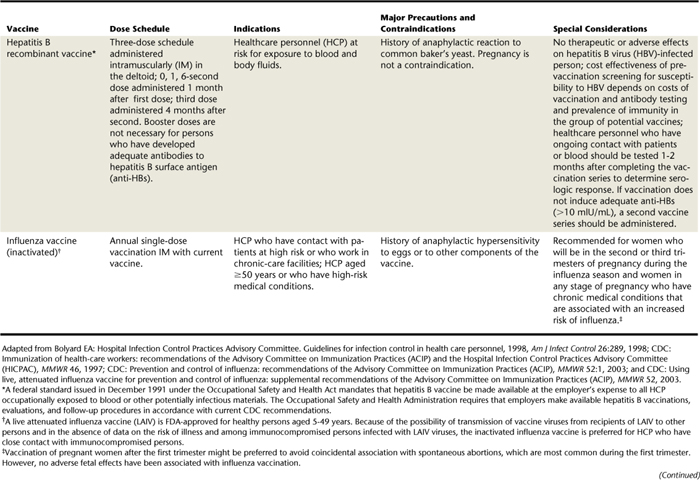

Immunization is one of the most effective means of preventing disease transmission. Once a person has acquired immunity through vaccination, the disease no longer poses a threat. In addition to standard childhood immunizations, hygienists should obtain immunizations specifically recommended for HCP. The CDC Advisory Council on Immunization Practices (ACIP) routinely reviews, updates, and revises immunization recommendations. It is therefore important to use the most current ACIP recommendations when making immunization decisions (Table 7-1).

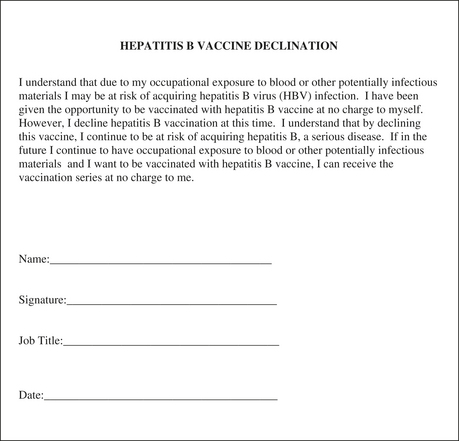

HCP in specific geographic locations or with underlying medical conditions may need immunizations in addition to those currently recommended by the CDC. It is important for each individual to consult with his or her physician to determine which immunizations are appropriate based on disease risk in the specific location. All children in the United States and most other countries receive immunization for diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus (DPT) as a combined vaccine. Of these, tetanus and pertussis require boosters later in life. Additional vaccines recommended for all HCP include hepatitis B, influenza, measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella unless the healthcare worker has naturally acquired immunity stemming from a past infection. In addition, the CDC recommends pneumococcal vaccine for all adults age 65 or older. CDC also recommends annual influenza vaccine for all healthcare personnel. OSHA requires employers to offer all personnel at risk of exposure to blood and other potentially infectious materials HBV vaccination unless they have verification of previous hepatitis B immunization or are infected with HBV. If the employee declines immunization, he or she must sign a specific OSHA-designated declination waiver (Figure 7-3). The vaccination is in a three-part series with a recommendation for post-titer testing 1 to 2 months after the third dose of vaccine. Persons who fail to respond should be offered a second three-dose series; when completed, the titer is retested for antibody response. Those who fail to develop detectable antibodies to hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs) after six doses should be considered nonresponders and tested for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), which indicates active infection or carrier status. If the result of this test is negative, the individual is considered as susceptible to HBV infection and counseled on precautions to avoid exposure and appropriate postexposure management.

Work Restrictions

DHCP should be aware of their personal health and take action to stay healthy. Within a written infection-control plan it is necessary to discuss those conditions that require a restriction or exclusion from direct patient care. The U.S. Public Health Service recommends work restrictions for HCP with specific infections and following exposure to some diseases (Table 7-2). Many of these infections are preventable with vaccines. The following precautions help protect HCP and clients:

HCP with mumps or measles should refrain from working during the acute illness phase, as well as after exposure and during the incubation phase if not immunized.

HCP with mumps or measles should refrain from working during the acute illness phase, as well as after exposure and during the incubation phase if not immunized. HCP diagnosed with hepatitis A should refrain from direct client contact and avoid handling food others will eat.

HCP diagnosed with hepatitis A should refrain from direct client contact and avoid handling food others will eat. HCP with an upper respiratory infection should avoid contact with medically compromised persons as defined by the ACIP for complications from influenza.

HCP with an upper respiratory infection should avoid contact with medically compromised persons as defined by the ACIP for complications from influenza. HCP with active herpes zoster (shingles) may continue to work unrestricted but should cover lesions to protect against exposure of nonintact skin to blood and body fluids.

HCP with active herpes zoster (shingles) may continue to work unrestricted but should cover lesions to protect against exposure of nonintact skin to blood and body fluids. For HCP identified as HBV e-antigen carriers, the CDC recommends that an expert review panel determine restrictions necessary for certain types of invasive procedures. The e-antigen is associated with a higher risk of transmission from HCP to client in spite of standard precautions. Any healthcare worker who is a hepatitis B e-antigen carrier should consult with a physician to determine status and explore options for treatment and concerns for client safety.

For HCP identified as HBV e-antigen carriers, the CDC recommends that an expert review panel determine restrictions necessary for certain types of invasive procedures. The e-antigen is associated with a higher risk of transmission from HCP to client in spite of standard precautions. Any healthcare worker who is a hepatitis B e-antigen carrier should consult with a physician to determine status and explore options for treatment and concerns for client safety. HCP with HIV are not specifically restricted, but it is possible that some modifications would be necessary for certain procedures. An expert review panel and physician should be consulted.

HCP with HIV are not specifically restricted, but it is possible that some modifications would be necessary for certain procedures. An expert review panel and physician should be consulted.TABLE 7-2 Work Restriction Guidelines for Healthcare Personnel with Infectious Diseases

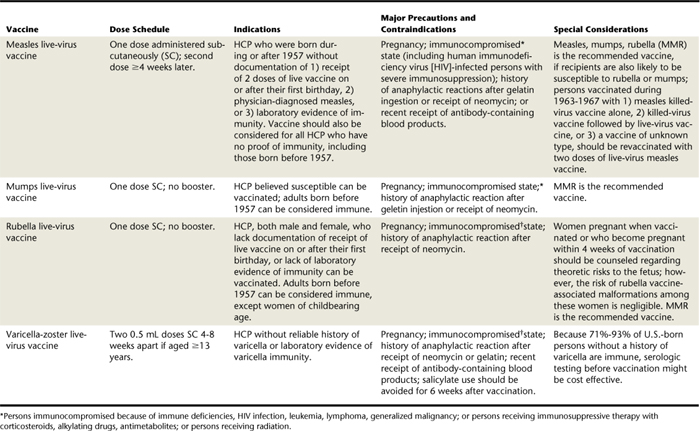

| Disease or Problem | Work Restriction | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Conjunctivitis | Restrict from client contact and contact with client environment. | Until no discharge |

| Cytomegalovirus infection | No restriction. | |

| Diarrheal disease | Restrict from client contact, contact with client’s environment, and food handling. | Until symptoms resolve |

| Enteroviral infection | Restrict from care of infants, neonates, and immunocompromised people and their environments. | Until symptoms resolve |

| Hepatitis A | Restrict from client contact, contact with client environment, and food-handling. | Until 7 days after onset of jaundice |

| Hepatitis B | ||

| Personnel with acute or chronic hepatitis B surface antigenemia who do not perform exposure-prone procedures | No restriction∗; refer to local regulations. Standard precautions should always be followed. | |

| Personnel with acute or chronic hepatitis B e-antigenemia who perform exposure-prone procedures | Do not perform exposure-prone invasive procedures until counsel from a review panel has been sought; panel should review and recommend procedures that personnel can perform, taking into account specific procedures as well as skill and technique. Standard precautions should always be observed. Refer to local regulations or recommendations. | Until hepatitis B e-antigen status is negative |

| Hepatitis C | No restrictions on professional activity.∗ HCV-positive healthcare personnel should follow aseptic technique and standard precautions. | |

| Herpes simplex (hands) | Restrict from client contact and contact with client’s environment. | Until lesions heal |

| Herpes simplex (orofacial) | Evaluate need to restrict from care of clients who are at high risk. | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus infection; personnel who perform exposure-prone procedures | Do not perform exposure-prone invasive procedures until counsel from an expert review panel has been sought; panel should review and recommend procedures that personnel can perform, taking into account specific procedures as well as skill and technique. Standard precautions should always be observed. Refer to local regulations or recommendations. | |

| Measles (active) | Exclude from duty. | Until 7 days after the rash appears |

| Measles (postexposure of susceptible personnel) | Exclude from duty. | From fifth day after first exposure through twenty-first day after last exposure or 4 days after rash appears |

| Meningococcal infection | Exclude from duty. | Until 24 hours after start of effective therapy |

| Mumps (active) | Exclude from duty. | Until 9 days after onset of parotitis |

| Mumps (postexposure of susceptible personnel) | Exclude from duty. | From twelfth day after first exposure through twenty-sixth day after last exposure, or until 9 days after onset of parotitis |

| Pediculosis | Restrict from client contact. | Until treated and observed to be free of adult and immature lice |

| Pertussis (active) | Exclude from duty. | From beginning of catarrhal stage through third week after onset of paroxysms, or until 5 days after start of effective antibiotic therapy |

| Pertussis (postexposure-asymptomatic personnel) | No restriction; prophylaxis recommended. | |

| Pertussis (postexposure-symptomatic personnel) | Exclude from duty. | Until 5 days after start of effective antibiotic therapy |

| Rubella (active) | Exclude from duty. | Until 5 days after rash appears |

| Rubella (postexposure-susceptible personnel) | Exclude from duty. | From seventh day after first exposure through twenty-first day after last exposure |

| Staphylococcus aureus infection (active, draining skin lesions) | Restrict from contact with clients and client’s environment or food handling. | Until lesions have resolved |

| Staphylococcus aureus infection (carrier state) | No restriction unless personnel are epidemiologically linked to transmission of the organism. | |

| Streptococcal group A infection | Restrict from client care, contact with patient’s environment, and food handling. | Until 24 hours after adequate treatment started |

| Tuberculosis (active) | Exclude from duty. | Until proven noninfectious |

| Tuberculosis (PPD converter) | No restriction. | |

| Varicella (active) | Exclude from duty. | Until all lesions dry and crust |

| Varicella (postexposure-susceptible personnel) | Exclude from duty. | From tenth day after first exposure through twenty-first day (twenty-eighth day if varicella-zoster immune globulin [VZIG] administered) after last exposure |

| Zoster (localized, in healthy person) | Cover lesions, restrict from care of clients† at high risk. | Until all lesions dry and crust |

| Zoster (generalized or localized in immunosuppressed person) | Restrict from client contact. | Until all lesions dry and crust |

| Zoster (postexposure-susceptible personnel) | Restrict from client contact. | From tenth day after first exposure through twenty-first day (twenty-eighth day if VZIG administered) after last exposure; or, if varicella occurs, when lesions crust and dry |

| Viral respiratory illness, acute febrile | Consider excluding from the care of clients at high risk‡ or contact with such clients’ environments during community outbreak of respiratory syncytial virus and influenza. | Until symptoms resolve |

∗ Unless epidemiologically linked to transmission of disease.

† Those susceptible to varicella and who are at increased risk of complications of varicella (e.g., neonates and immunocompromised persons of any age).

‡ Patients at high risk as defined by ACIP for complications of influenza.

Adapted from Bolyard EA: Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guidelines for infection control in health care personnel, 1998, Am J Infect Control 26:289, 1998. Adapted from recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

It is important to consult current CDC recommendations for HCP and specific state laws or recommendations.

Standard Precautions

Standard precautions are the practices by which healthcare personnel follow the same infection-control protocols for all clients regardless of infectious status or health history. Health history alone will not reliably identify all persons with HIV infection, HBV infection, or other blood-borne diseases. Some infected individuals are unaware of their status, and others may choose not to disclose their disease status on the health history. Certain precautions will prevent the transmission of these viruses when applied during client care. These precautions protect both the HCP and the patient from disease transmission.

Standard precautions are a synthesis of the major features of universal precautions and body substance isolation precautions and apply to the following:

Other bodily fluids, secretions, and excretions except sweat regardless of whether or not they contain visible blood

Other bodily fluids, secretions, and excretions except sweat regardless of whether or not they contain visible bloodTherefore standard precautions apply to blood and all moist body substances.

Transmission-Based Precautions

Certain diseases require measures in addition to universal precautions, based on the route of transmission. Expanded or transmission-based precautions might be necessary to prevent potential spread of certain diseases (e.g., TB, influenza, and varicella) that are airborne or transmitted by droplet or contact (e.g., sneezing, coughing, and contact with skin). Persons acutely ill with these diseases do not usually seek routine dental care. Nonetheless, a general understanding of precautions for diseases transmitted by all routes is critical for the following reasons:

DHCP might become infected with these diseases. Necessary transmission-based precautions might include client placement (isolation), adequate room ventilation, respiratory protection (N-95 masks) for DHCP, or postponement of nonemergency dental procedures.

DHCP might become infected with these diseases. Necessary transmission-based precautions might include client placement (isolation), adequate room ventilation, respiratory protection (N-95 masks) for DHCP, or postponement of nonemergency dental procedures.The CDC has identified three categories of transmission-based precautions, as follows:

Transmission-based precautions are used when the route of transmission are not completely interrupted using standard precautions alone. For some diseases that have multiple routes of transmission (e.g., severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS]), more than one transmission-based precaution category may be used. Whether transmission-based precautions are used singly or in combination, universal precautions always apply as well.

In the case of clinically active TB, the level of protection afforded by standard precautions is not sufficient to prevent transmission. TB transmission is affected by a hierarchy of measures that include administrative controls, environmental controls, and personal respiratory protection. For clients known or suspected to have active TB, the CDC recommends the following:

Health History (see Chapters 10 and 11)

The health history is an important tool for:

Identifying persons infected with diseases for which there may be a need for additional infection precautions (e.g., transmission-based precautions)

Identifying persons infected with diseases for which there may be a need for additional infection precautions (e.g., transmission-based precautions)DHCP should be aware of signs and symptoms of infectious diseases and cognizant of the steps required to minimize risk of transmission. This is particularly important if a client has active TB, signs and symptoms of which may include coughing, chest pain, sweating, weight loss, and fever. Coughing, especially if persistent and if blood is present, is a key indicator of infection. A client with active TB or suspected of having active TB should be isolated from other clients, asked to wear a face mask, and educated to contact his or her physician of record for definitive medical diagnosis (e.g., presence or absence of TB).

The Mantoux test is the most common and accurate test for TB. The CDC recommends this test, which involves an intradermal injection of purified protein derivative (PPD) into the skin of the forearm. The area is observed for 48 to 72 hours after the injection for development of a wheal that is red, is raised, and measures at least 10 mm across. If it has been several years since the last time a person had a TB skin test, the physician may recommend repeating the test to rule out the potential for a false-negative result. For HIV-infected individuals, a 5-mm wheal is an indication of infection owing to the tendency of immunocompromised individuals to develop a lesser reaction. A positive skin test result is an indication of infection with the bacterium but is not an indication of active disease. In fact, the majority of individuals with a positive skin test result do not have active TB. About 10% of infected individuals will develop active TB in their lifetime. About 5% develop the active disease shortly after exposure, and 5% develop active disease later in life, usually owing to a compromised immune system.

Most people who experience a positive skin test result receive preventive chemotherapy for 6 months. The standard drug for prevention of active infection is isoniazid (INH). To treat an active infection (i.e., in a symptomatic person), physicians use INH in combination with other medications (e.g., rifampin, pyrazinamide). Rare cases of TB do not respond to traditional therapy. These cases, referred to as drug-resistant TB, are more likely to result in death of the infected individual.

Engineering Controls

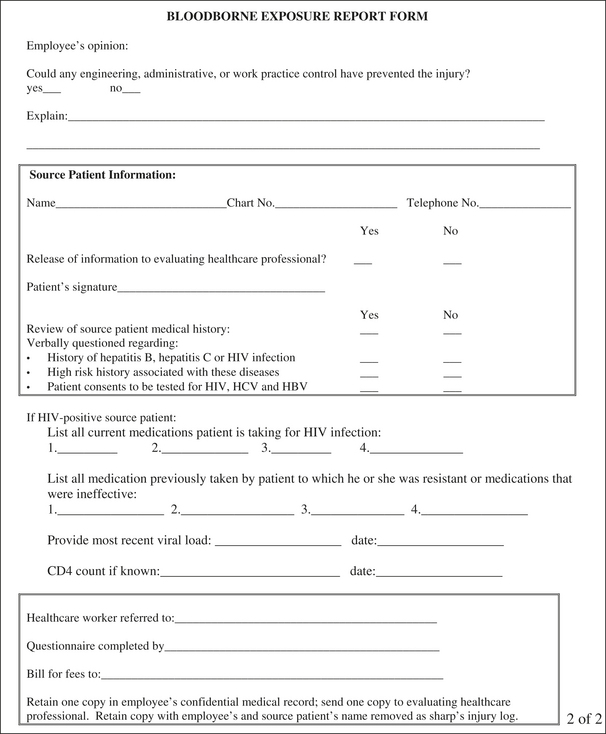

Engineering controls are devices or equipment that reduce or eliminate a hazard (Figure 7-4). In the context of oral healthcare, these include the following:

Figure 7-4 Examples of engineering controls. A, Sharps container with biohazard warning label. B, Dental safety syringe. C, Safety scalpel with retractable blade D, Disposable scalpel.

Consider the use of engineering controls when it is reasonable to believe that the control measure will reduce the potential for exposure to a client’s blood or body fluids. OSHA requires the use of sharps with engineered sharps injury protection when available and when found to provide superior protection compared with the standard devices. Examples include syringes with retractable needles or needle guards, scalpels with retractable blades or blade guards, and other devices that render the sharp safer through blunting, encapsulation, guarding, or destruction.

Work Practice Controls

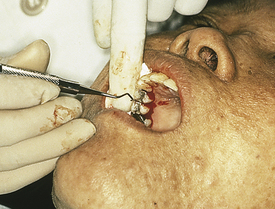

Work practice controls reduce or eliminate a hazard by changing the way in which workers perform a task. Figure 7-5 shows improper positioning of fingers, placing the dental hygienist at risk. Proper client positioning that allows a 14- to 18-inch focal distance may reduce the hygienist’s exposure to contaminated droplets generated during certain procedures. Proper client positioning also increases visibility and access to the mouth, further decreasing the risk for accidental injury. Use of a high-speed evacuator while spraying a client’s mouth with air and water reduces the amount of droplet splash compared with the use of low-speed suction or no suction. Using an ultrasonic cleaner, washer, or disinfector to decontaminate used dental instruments before sterilization is another example of work practice controls. Use of automated instrument cleaning reduces the need for the DHCP to handle contaminated instruments.

Personal Protective Equipment

The term personal protective equipment (PPE) refers to garments, eye protection, airway protection, and other attire worn with the intent to protect the worker from blood and body fluid exposure. Work practice controls and engineering controls are the preferred method of protection. PPE is indicated when those controls will not prevent exposure to blood and body fluids. The PPE selected should protect the worker from exposure to the skin, clothing, eyes, mouth, and other mucous membranes during the normal course of his or her duties (see Figure 7-1).

Always base the selection of protective attire on the nature of the procedure and anticipated exposure risks. Procedures that generate spray or droplets of blood or saliva (e.g., scaling and root planing, air polishing) require a higher level of protection than procedures that do not produce body fluids (e.g., x-ray examinations). Do not base the selection of PPE on the infectious disease status of the client. The infection-control precautions for any given procedure should be the same for each client.

Eye and Face Protection

Appropriate eye protection includes goggles, glasses with solid side shields, or a face shield that protect the eyes from exposure to infectious, chemical, and physical hazards (Figure 7-6). The CDC recommends and OSHA regulates that protective eyewear meet the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) standards for spatter protection and impact protection. Healthcare workers who wear prescription eyeglasses should consult an eyecare professional to ensure that the style and materials of the eyewear meet ANSI standards for protective eyewear or should purchase ANSI-certified goggles or face shields that fit over the prescription eyewear.

When laser technologies are used, additional eye protection may be required. Every pair of safety goggles or safety glasses intended for use with laser beams must bear a label with the following information:

Masks

A surgical mask protects the mucous membranes of the nose and mouth from exposure to spatter generated under a variety of dental procedures. Wear masks under the same circumstances that warrant the use of eye protection (Figure 7-7). Base the selection of masks on comfort, how well the periphery of the mask conforms to the contours of the face, and the level of filtration the mask provides. In general, a mask rated as surgical will have a filtration rating superior to that of masks rated as procedure masks.

Protective Clothing

Protective clothing should shield both intact and nonintact skin from spray or splash of body fluids during the course of treatment. In addition, the protective clothing must provide a barrier to protect work clothes or street clothes from exposure. In most dental settings a long-sleeved lab coat that falls below the knees is adequate. However, during exposure-prone procedures, such as surgical procedures, the hygienist may need a more fluid-resistant material. Protective clothing is removed before the hygienist leaves the work area, such as during lunch and other breaks. OSHA restricts HCP from taking their own protective attire home for laundering. It is the employer’s responsibility to arrange for laundering or use of disposable garments, in addition to providing adequate protective attire.

Gloves

Gloves used for dental and dental hygiene procedures fall into three categories, as follows:

Medical examination gloves—nonsterile gloves that are available in a variety of sizes and materials, powdered and unpowdered, and either ambidextrous or right- or left-hand specific (Figure 7-8).

Medical examination gloves—nonsterile gloves that are available in a variety of sizes and materials, powdered and unpowdered, and either ambidextrous or right- or left-hand specific (Figure 7-8). Sterile surgeon’s gloves (indicated for oral surgical procedures)—sterilize gloves individually packaged in sized pairs. To maintain sterility of gloves, do not open package until ready to use for surgical procedures.

Sterile surgeon’s gloves (indicated for oral surgical procedures)—sterilize gloves individually packaged in sized pairs. To maintain sterility of gloves, do not open package until ready to use for surgical procedures. Heavy-duty utility gloves—puncture-resistant gloves (Figure 7-9), used during cleaning and disinfection procedures to reduce risk of accidental puncture injury.

Heavy-duty utility gloves—puncture-resistant gloves (Figure 7-9), used during cleaning and disinfection procedures to reduce risk of accidental puncture injury.Hand Protection and Hand Hygiene

HCP are increasingly reporting allergic and nonallergic dermatitis of the hands. Many of these reactions are the result of contact with chemicals used in the manufacture of latex. However, a small percentage involve a potentially serious allergic reaction to the proteins found in natural rubber latex. It is important to seek the advice of a qualified healthcare professional (e.g., physician with specialty in dermatitis and allergies) when experiencing dermal problems related to the use of medical gloves.

Hand hygiene is the most important behavior in the prevention of disease transmission.

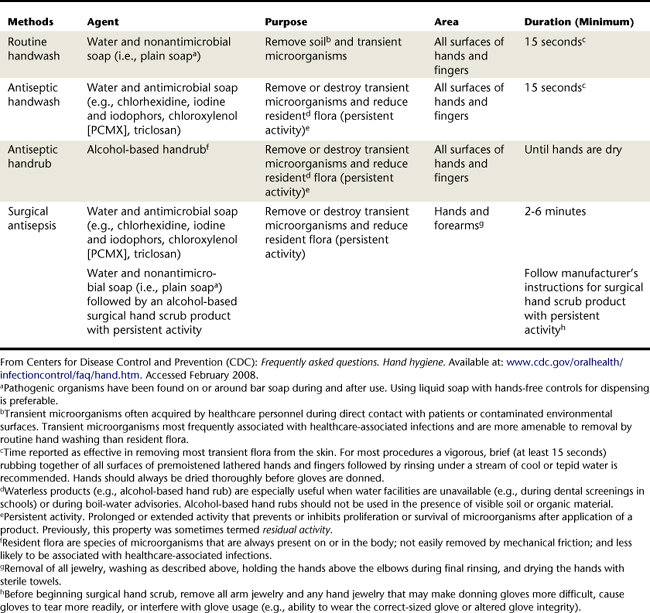

The preferred method for hand hygiene depends on the type of procedure, the degree of contamination, and the desired persistence of antimicrobial action on the skin (Table 7-3). Remove transient microbial flora and debris by cleaning the hands with detergent and water. The presence of colonized or resident flora on the hands requires the use of antiseptic agents. For routine dental procedures (e.g., screening, examination, and nonsurgical procedures), wash hands with either plain or antimicrobial soap and water. If the hands are not visibly soiled, an alcohol-based hand rub is adequate. Hand hygiene for surgical procedures (e.g., periodontal surgery, surgical extraction of teeth, biopsy) requires surgical hand antisepsis to eliminate transient flora and reduce resident flora.

Antiseptic agents for surgical procedures should have a lasting antimicrobial effect on the hands for the duration of a procedure, to do the following:

However, frequent hand washing and the use of gloves may contribute to the development of nonallergic dermatitis, and it is important for dental healthcare workers to practice protective hand care as follows:

Limit the Spread of Blood and Other Infectious Bodies

Environmental Surface Disinfection

Environmental surfaces are less likely to provide an efficient mechanism for transmission of infectious agents than contaminated instruments; however, they can become contaminated in oral healthcare settings.

Cross-Contamination

Cross-contamination is the transfer of oral fluids and debris from a client to surfaces, equipment, materials, workers’ hands, or another person. Because saliva is invisible yet capable of containing high bacterial and viral particle loads, cross-contamination is particularly problematic in oral healthcare. Pathogenic organisms, potentially present in oral fluids, may survive on environmental surfaces for days, weeks, and even months if left untreated with a germicidal product.

Cross-contamination may be by direct or indirect means:

Direct cross-contamination occurs when a worker fails to change gloves between patients or fails to properly clean and sterilize instruments between uses. An example of direct cross-contamination is the use of a disposable dental product such as a saliva ejector on multiple clients.

Direct cross-contamination occurs when a worker fails to change gloves between patients or fails to properly clean and sterilize instruments between uses. An example of direct cross-contamination is the use of a disposable dental product such as a saliva ejector on multiple clients. Indirect cross-contamination occurs when handling a container, armamentaria, or equipment with contaminated gloves and failing to disinfect the items between clients.

Indirect cross-contamination occurs when handling a container, armamentaria, or equipment with contaminated gloves and failing to disinfect the items between clients.Numerous strategies exist to prevent contamination. It is difficult or impossible to sterilize most items and surface areas in the oral care environment. Therefore the best way to manage environmental surfaces in the clinical environment is to clean and disinfect with an EPA-registered disinfectant or protect surfaces with fluid-impervious barriers (e.g., plastic covers). To be effective the disinfectant must come into direct contact with a precleaned surface.

The CDC designates environmental surfaces in the oral healthcare setting into two categories:

Housekeeping surfaces—areas that may be difficult or impossible to clean include switches, knobs, hoses, brackets, and many other items used in the delivery of care. Protect these surfaces by covering them with fluid-impervious barriers (see Figure 7-2). Always change barriers between clients.

Housekeeping surfaces—areas that may be difficult or impossible to clean include switches, knobs, hoses, brackets, and many other items used in the delivery of care. Protect these surfaces by covering them with fluid-impervious barriers (see Figure 7-2). Always change barriers between clients. Clinical contact surfaces—surfaces that become contaminated from spray or droplets of oral fluids or by touching with gloved hands during the procedure. These surfaces may be difficult to clean and can subsequently contaminate other instruments, devices, hands, or gloves. Disinfect or barrier-protect clinical contact surfaces including:

Clinical contact surfaces—surfaces that become contaminated from spray or droplets of oral fluids or by touching with gloved hands during the procedure. These surfaces may be difficult to clean and can subsequently contaminate other instruments, devices, hands, or gloves. Disinfect or barrier-protect clinical contact surfaces including:

In the absence of barriers, clean and disinfect surfaces and equipment between clients with an EPA-registered hospital disinfectant (low-level disinfectant) or an EPA-registered hospital disinfectant with a tuberculocidal claim (intermediate-level disinfectant). Use intermediate-level disinfectant for surfaces with visible blood or other potentially infectious materials (OPIM) (Figures 7-10 and 7-11).

General cleaning and disinfection are recommended for clinical contact surfaces, dental unit surfaces, and countertops at the end of daily work activities and are required if surfaces have become contaminated since their last cleaning. Keeping treatment areas free of unnecessary equipment and supplies facilitates daily cleaning.

Follow manufacturer directions for the handling, use, and storage of all disinfectant and cleaning products. Manufacturers of dental devices and equipment should provide information regarding material compatibility with liquid chemical germicides, precautions regarding immersion of devices for cleaning, and how to decontaminate the item if servicing is required. DHCP who perform environmental cleaning and disinfection should wear gloves and other PPE to prevent occupational exposure to infectious agents and hazardous chemicals. Chemical- and puncture-resistant utility gloves offer more protection than patient examination gloves when hazardous chemicals are used (Figure 7-12).

Sterilization and Sterility Assurance—Make Client Care Items Safe for Use

Client care items are either single-use disposable items or reusable items that require sterilization between uses. Sterilization is the destruction of all living organisms, including highly resistant bacterial spores. Properly performed cleaning and sterilization procedures offer the highest level of assurance that no pathogenic organisms remain on instruments and devices. The intent of instrument and equipment sterilization is not to establish a sterile care environment. Indeed, such an environment would be impossible to establish. Rather, the sterilization process ensures the destruction of all organisms transferred to an item during use on one client before reuse of the item on a subsequent client.

Instrument Classification

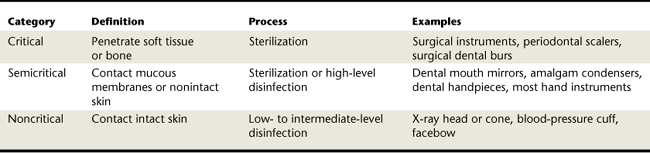

Dental instruments fall into three broad categories for determining the minimum level of management between clients (Table 7-4):

Critical instruments are instruments that penetrate soft tissue or bone. Critical instruments must be heat sterilized between each use or discarded if disposable. Examples of critical instruments and devices include periodontal probes, explorers, scaling and root planing instruments, and tip insert of an ultrasonic scaling unit.

Critical instruments are instruments that penetrate soft tissue or bone. Critical instruments must be heat sterilized between each use or discarded if disposable. Examples of critical instruments and devices include periodontal probes, explorers, scaling and root planing instruments, and tip insert of an ultrasonic scaling unit. Semicritical instruments are not intended to penetrate soft tissue or bone but contact oral fluids. Examples include mouth mirrors, ultrasonic scaling handpieces, impression trays, and oral photography retractors. These instruments should also be heat sterilized between each use. The use of high-level disinfectants is indicated for semicritical instruments that cannot be heat sterilized. These germicides are chemical disinfectants that provide sterilization under certain conditions. Chemical germicides are not as reliable as heat sterilization methods and raise worker safety concerns; therefore heat-stable or disposable alternatives are preferred.

Semicritical instruments are not intended to penetrate soft tissue or bone but contact oral fluids. Examples include mouth mirrors, ultrasonic scaling handpieces, impression trays, and oral photography retractors. These instruments should also be heat sterilized between each use. The use of high-level disinfectants is indicated for semicritical instruments that cannot be heat sterilized. These germicides are chemical disinfectants that provide sterilization under certain conditions. Chemical germicides are not as reliable as heat sterilization methods and raise worker safety concerns; therefore heat-stable or disposable alternatives are preferred. Noncritical instruments and devices are those items that come into contact only with intact skin. Examples include an x-ray head, light handles, high- and low-volume evacuators, tubing for handpieces, instrument trays, countertops, and chair surfaces. Disinfect these items with an EPA-registered low- to intermediate-level disinfectant.

Noncritical instruments and devices are those items that come into contact only with intact skin. Examples include an x-ray head, light handles, high- and low-volume evacuators, tubing for handpieces, instrument trays, countertops, and chair surfaces. Disinfect these items with an EPA-registered low- to intermediate-level disinfectant.Heat Methods of Sterilization

Heat-based sterilization methods are more time efficient and reliable than chemical germicides. It is important to determine the method of sterilization that provides a safe and effective outcome for the type of devices.

DHCP must use an FDA-approved sterilization device and follow the manufacturer’s instructions for cycle time, temperature, and other parameters involved in achieving sterilization. For satisfactory results, thoroughly clean instruments before placing into appropriate packaging and sterilizing. Three major types of heat sterilization are available:

Autoclave, the most common method of heat sterilization in the dental office, uses steam in a pressurized chamber to sterilize heat-stable instruments and devices. The user places distilled water into a chamber that dispenses the amount needed to provide steam for the process. Most autoclaves require several minutes to achieve the temperature necessary to begin the sterilization process. Additional time at the end of the sterilization cycle allows depressurization of the chamber. Two methods of air evacuation are available in autoclaves: prevacuum and gravity displacement.

Autoclave, the most common method of heat sterilization in the dental office, uses steam in a pressurized chamber to sterilize heat-stable instruments and devices. The user places distilled water into a chamber that dispenses the amount needed to provide steam for the process. Most autoclaves require several minutes to achieve the temperature necessary to begin the sterilization process. Additional time at the end of the sterilization cycle allows depressurization of the chamber. Two methods of air evacuation are available in autoclaves: prevacuum and gravity displacement.

An unsaturated chemical vapor sterilizer uses a process similar to that of the autoclave; however, in place of steam, a chemical vapor enters the pressurized sterilization chamber. The use of chemical vapor instead of steam reduces the humidity of the sterilization process, reducing the risk of instrument rust and corrosion (primarily carbon steel instruments).

An unsaturated chemical vapor sterilizer uses a process similar to that of the autoclave; however, in place of steam, a chemical vapor enters the pressurized sterilization chamber. The use of chemical vapor instead of steam reduces the humidity of the sterilization process, reducing the risk of instrument rust and corrosion (primarily carbon steel instruments).Chemical Disinfectants and Sterilants

Several classes of chemical agents are available that provide high-level disinfection and sterilization under given conditions. Varying degrees of corrosion and damage to certain materials occur if instruments or devices are in prolonged contact with the chemical agent. In addition, the CDC discourages the use of these chemicals because of their toxic properties.

Sterility Assurance

To ensure effectiveness of sterilization, several levels of sterility assurance are available, and a combination approach is best.

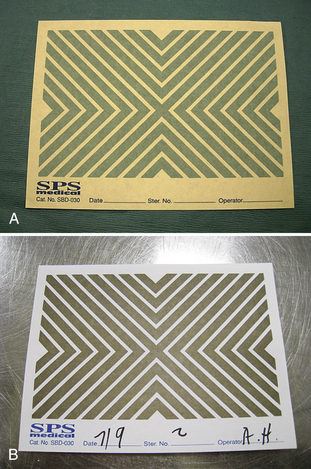

Chemical indicators allows the operator to determine the presence of certain necessary parameters such as heat or steam. These indicators often appear as arrows or color-change indicators on pouches used to package instruments during sterilization (Figure 7-14). They are also available as tape imbedded with stripes that change color or indicator strips. One should use chemical indicators with every packet of instruments as a signal to the user that the particular packet completed a heat sterilization process. The indicator is not an indication of effectiveness of the sterilization process itself because many factors may interfere with adequate sterilization.

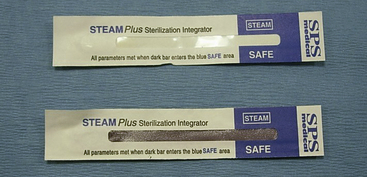

Chemical indicators allows the operator to determine the presence of certain necessary parameters such as heat or steam. These indicators often appear as arrows or color-change indicators on pouches used to package instruments during sterilization (Figure 7-14). They are also available as tape imbedded with stripes that change color or indicator strips. One should use chemical indicators with every packet of instruments as a signal to the user that the particular packet completed a heat sterilization process. The indicator is not an indication of effectiveness of the sterilization process itself because many factors may interfere with adequate sterilization. Multiparameter indicators, also called integrators, are a higher level of sterilization assurance and indicate that more than one parameter required for sterilization was present (Figure 7-15). Different levels of integrators provide different levels of sterility assurance. Class V indicators are equivalent to a biologic indicator. The product manufacturer must establish the efficacy of the class V indicator with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

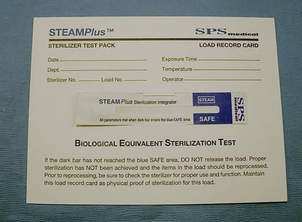

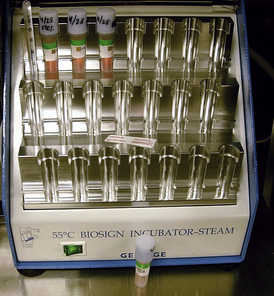

Multiparameter indicators, also called integrators, are a higher level of sterilization assurance and indicate that more than one parameter required for sterilization was present (Figure 7-15). Different levels of integrators provide different levels of sterility assurance. Class V indicators are equivalent to a biologic indicator. The product manufacturer must establish the efficacy of the class V indicator with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Biologic indicators (BIs), also called spore tests, are the highest level of verification (Figure 7-16). BIs use nonpathogenic spores that are especially resistant to the sterilization process embedded on a strip or in a solution that is placed in the sterilizer with a load of instruments. Incubation of the spore test confirms the destruction of the spores by the sterilization process, which indicates a successful sterilization process.

Biologic indicators (BIs), also called spore tests, are the highest level of verification (Figure 7-16). BIs use nonpathogenic spores that are especially resistant to the sterilization process embedded on a strip or in a solution that is placed in the sterilizer with a load of instruments. Incubation of the spore test confirms the destruction of the spores by the sterilization process, which indicates a successful sterilization process.

Destruction of spores resistant to the specific sterilization methods indicates the elimination of all of the organisms of concern. Spore test at least weekly and with each implantable device to verify the proper functioning and operation of the sterilizer. Maintain records of spore testing and their results in the dental office. Many states require biologic monitoring (spore testing) and specify the length of time to maintain the test result records.

Exposure Prevention and Management

The risk of infection with a blood-borne disease after an occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens in dental settings is low. However, every exposure to blood and body fluids carries some risk for transmission of blood-borne pathogens. Risk reduction strategies include the use of safer work practices, safer devices, PPE, proper policies and procedures, awareness of personal health status, attention to standard precautions, and a program of ongoing education. The majority of exposures are preventable. The CDC defines an occupational exposure as a percutaneous injury or contact of mucous membrane or nonintact skin with blood, saliva, tissue, or other body fluids that are potentially infectious. Exposure incidents may pose a risk of HBV, HCV, or HIV infection and are a matter of medical urgency.

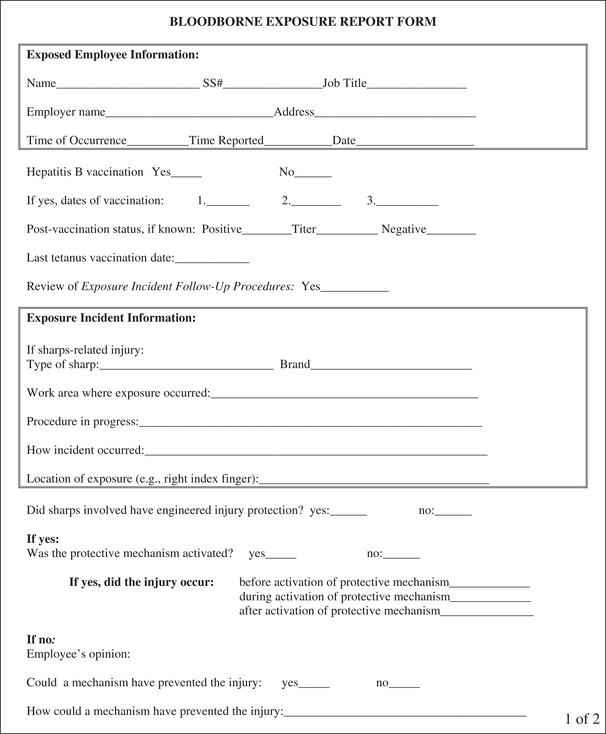

Every dental facility must have a postexposure management program for occupational exposures. There should be a written program that identifies the specific steps to follow after an exposure incident and includes training and education as to the types of exposure that put dental healthcare practitioners at risk and procedures for prompt reporting and evaluation (including counseling, testing, and follow-up) according to the most current U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) guidelines. These policies should be in compliance with the OSHA blood-borne pathogen standard and with any state or local laws or regulations.

Prevention and management of injury programs follow the public health doctrine of prevention:

Tertiary prevention strives to return to a functional state of no exposure and prevent similar injuries from occurring again.

Tertiary prevention strives to return to a functional state of no exposure and prevent similar injuries from occurring again.Steps for Risk Reduction

Primary prevention involves all efforts to avoid injury during each facet of delivering oral healthcare services, including setting up a treatment room, providing care, and performing posttreatment cleanup. This includes being familiar with the written infection-control plan and all policies, procedures, and best practices to avoid injury. Prevention of injuries may include the use of engineering controls, including safer devices, work practice controls, PPE, and other methods of hazard abatement and risk reduction such as standard precautions. Therefore the first step for risk reduction is to assess risks as environmental, administrative or procedural, and personal. After the risk is assessed, it is important to determine if actions can be taken to remove or at least reduce risk by modifying policies, procedures, or practices or choosing alternative devices.

Risk assessment involves determining what is done, by whom, how it is done, and with what products and devices. Risk reduction then involves the selection of engineering or work practice controls appropriate to the anticipated procedures. The ultimate lesson is that it is far better to prevent the exposure in the first place than to deal with the consequences of an exposure such as counseling, testing, and medical follow-up. The underlying theme of risk reduction is standard precautions.

Risk Reduction Protocols

Several risk reduction protocols center on the need to prevent percutaneous injuries:

Use of medical devices with engineered safety features designed to prevent injuries and/or use of safer techniques

Use of medical devices with engineered safety features designed to prevent injuries and/or use of safer techniques

Avoidance of hand contact with sharps

Avoidance of hand contact with sharps

Work practice controls have some of the greatest impact on preventing blood-borne disease transmission. Given the types of exposures found in dental settings, over 90% are associated with needles or other sharp devices. The CDC determined that most occur outside the mouth and on the hands and fingers of the worker. Many of these are preventable with proper caution and the use of safer devices.

Postexposure Management

When an injury occurs, the goal is to contain the injury as soon as possible to reduce risk of transmission (secondary prevention). If an exposure occurs, offer the exposed worker immediate postexposure management in accordance with the most recent USPHS guidelines. It is critical to select a qualified healthcare provider (QHCP) trained to evaluate and treat infectious diseases, including HIV infection. In order for the QHCP to provide appropriate treatment and assess the need for follow-up, he or she must receive specific information regarding the exposure incident. This information includes the circumstances, devices, degree, and severity of exposure. If the source client consents, the QHCP will determine the source client’s infectious disease status through testing. Basic steps of postexposure management are as follows:

Exposure Follow-Up Guidelines

HBV: Follow-up of occupational exposure to HBV depends on the HBsAg status of the source client and the vaccination and anti-HBs response of the exposed worker. If the exposed worker is unvaccinated for HBV, it is likely that the vaccination series will be initiated. A prevaccination titer test is not necessary. If the source individual has a history of HBV infection, administration of hepatitis B immune globulin will likely be part of the management protocol. Treatment should begin as soon as possible, preferably within 24 hours and in less than 1 week. If the exposed DHCP has been vaccinated and is a known responder, no action is necessary as the HBV vaccine has strong immunologic memory. However, if the immune status is unknown or the individual is a known nonresponder to the vaccine, other considerations must be taken.

HBV: Follow-up of occupational exposure to HBV depends on the HBsAg status of the source client and the vaccination and anti-HBs response of the exposed worker. If the exposed worker is unvaccinated for HBV, it is likely that the vaccination series will be initiated. A prevaccination titer test is not necessary. If the source individual has a history of HBV infection, administration of hepatitis B immune globulin will likely be part of the management protocol. Treatment should begin as soon as possible, preferably within 24 hours and in less than 1 week. If the exposed DHCP has been vaccinated and is a known responder, no action is necessary as the HBV vaccine has strong immunologic memory. However, if the immune status is unknown or the individual is a known nonresponder to the vaccine, other considerations must be taken. HCV: There is neither preexposure vaccination nor postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) for occupational exposure to HCV. The most current recommendation for follow-up of occupational exposure to HCV is to test the source client for antibodies to hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) and to test the exposed worker for anti-HCV and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity. Recommendations include repeated testing at 4 to 6 months. It is important to identify HCV infection early should transmission have occurred and to refer the exposed individual to a specialist. There are limited data to suggest that antiviral treatment initiated early in the course of infection may be beneficial.

HCV: There is neither preexposure vaccination nor postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) for occupational exposure to HCV. The most current recommendation for follow-up of occupational exposure to HCV is to test the source client for antibodies to hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) and to test the exposed worker for anti-HCV and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity. Recommendations include repeated testing at 4 to 6 months. It is important to identify HCV infection early should transmission have occurred and to refer the exposed individual to a specialist. There are limited data to suggest that antiviral treatment initiated early in the course of infection may be beneficial. HIV: Recommendations for HIV PEP are based on situations where there has been an occupational exposure to a source patient who either has or is considered likely to have HIV infection. If indicated, the worker should begin postexposure treatment as soon as possible (within 2 hours). The course of treatment usually involves a 4-week regimen of two or more antiretroviral drugs, depending on the nature of the exposure.

HIV: Recommendations for HIV PEP are based on situations where there has been an occupational exposure to a source patient who either has or is considered likely to have HIV infection. If indicated, the worker should begin postexposure treatment as soon as possible (within 2 hours). The course of treatment usually involves a 4-week regimen of two or more antiretroviral drugs, depending on the nature of the exposure.Postexposure management is an area of rapidly changing recommendations. As new antiretroviral agents become available, some are replacing drugs previously used. Therefore it is important to seek the advice and care of an appropriate provider who is familiar with the most current USPHS recommendations for testing and PEP. Counseling as to the potential side effects and reporting of illness are essential to the appropriate medical management of an occupational exposure to HIV.

The CDC recommends counseling as to the risks and benefits for the pregnant worker and extensive follow-up. Pregnancy may affect the selection of antiretrovirals because some of these drugs are contraindicated in a pregnant woman.

Risk of Exposure

Exposure risk varies with the amount of blood, the titer of virus in the patient, and the depth of the injury with the contaminate device or instrument. Immediate initiation of treatment is important, preferably within 2 hours. The goal is to prevent viral replication in the exposed worker, and there is biologic evidence that this is possible. Postexposure management with antiretroviral drugs may reduce risk of infection by about 80% but will not prevent all cases of infection. Postexposure management may fail owing to a resistant virus, an increased titer of virus, an increased dose of blood, or host factors.

Follow-up also involves counseling regarding signs and symptoms of infection, the importance of measures to not infect others, and the importance of seeking advice if illness occurs:

For HCV, it may be necessary to monitor liver function and have tests for HCV antibody. Often tests are repeated at 4 to 6 weeks.

For HCV, it may be necessary to monitor liver function and have tests for HCV antibody. Often tests are repeated at 4 to 6 weeks. For HIV, baseline testing is part of the standard protocol and repeat testing may be indicated at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months, or even up to 1 year if co-infection with, for example, HCV is an issue. If the worker is taking antiretroviral drugs, the exposed person may need to have drug toxicity tests.

For HIV, baseline testing is part of the standard protocol and repeat testing may be indicated at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months, or even up to 1 year if co-infection with, for example, HCV is an issue. If the worker is taking antiretroviral drugs, the exposed person may need to have drug toxicity tests.Risk of Infection

Most exposures do not lead to infection, and the risk of seroconversion may vary depending on the agent, the type of exposure, the amount of blood involved, and the amount of circulating virus in the source client. When assessing an occupational exposure and determining the management and follow-up, a QHCP will review the following:

Infectious status of the source such as presence of HBsAg, presence of HCV antibody, and/or presence of HIV antibody

Infectious status of the source such as presence of HBsAg, presence of HCV antibody, and/or presence of HIV antibody Susceptibility of exposed person with consideration to the HBV vaccine response status and the HBV, HCV, and/or HIV status

Susceptibility of exposed person with consideration to the HBV vaccine response status and the HBV, HCV, and/or HIV statusFor HBV the risk of infection ranges from 6% to 30% in persons not protected by vaccination or previous infection. Source individuals who are hepatitis e-antigen positive are potentially more infectious and more likely to transmit diseases. The best protection is vaccination against HBV.

For HCV the risk is about 1.8% on average for percutaneous exposures. There are no exact estimates of the number of healthcare workers occupationally infected with HCV, but the risk to a healthcare worker is no higher than the average community risk.

For HIV, average risk after a percutaneous exposure is about 0.3%. The risk after exposure to eyes, nose, or mouth is about 0.1%, and the risk to skin is estimated to be less than that unless the skin is damaged or compromised, in which case the risk would be higher.

In tertiary prevention the healthcare professional learns from the exposure incident, restores those exposed to a state of no infection, and takes all steps to reduce future exposure risk by:

Reviewing policies, procedures, products, devices, and practices; perhaps modifying policies or procedures and/or selecting safer devices

Reviewing policies, procedures, products, devices, and practices; perhaps modifying policies or procedures and/or selecting safer devicesMaximum effort should be aimed at injury prevention because preventing an exposure in the first place is far better than dealing with the consequences of an exposure. These include medical management and follow-up as prescribed. Preventive strategies include the routine use of barriers when anticipating contact with blood or OPIM, adherence to hand washing, and the careful handling and disposal of sharps during and after use. Therefore avoiding occupational exposure involves the use of engineering controls, work practice controls, and PPE.

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Explain infection-control protocols used in the delivery of dental hygiene care and their underlying rationale.

Explain infection-control protocols used in the delivery of dental hygiene care and their underlying rationale.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Using evidence-based infection-control protocols is both an ethical and a legal requirement for dental hygienists.

Using evidence-based infection-control protocols is both an ethical and a legal requirement for dental hygienists. Evidence-based standard precautions are a standard of care. Healthcare personnel who fail to render services using current standards of care place themselves at risk for both civil and criminal violations.

Evidence-based standard precautions are a standard of care. Healthcare personnel who fail to render services using current standards of care place themselves at risk for both civil and criminal violations. The reasonably prudent dental hygiene practitioner must stay current with regard to changing infection-control concepts, protocols, and governmental guidelines; this is a matter of state law or regulation in some jurisdictions.

The reasonably prudent dental hygiene practitioner must stay current with regard to changing infection-control concepts, protocols, and governmental guidelines; this is a matter of state law or regulation in some jurisdictions.KEY CONCEPTS

Sterilization and surface disinfection can be achieved by physical or chemical means based on the equipment, type of procedure, and level of exposure risk.

Sterilization and surface disinfection can be achieved by physical or chemical means based on the equipment, type of procedure, and level of exposure risk. Hand washing is the most effective strategy in the prevention of infection and disease transmission.

Hand washing is the most effective strategy in the prevention of infection and disease transmission. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for standard precautions indicate that healthcare personnel use personal protective equipment when exposure to body fluids is likely.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for standard precautions indicate that healthcare personnel use personal protective equipment when exposure to body fluids is likely.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

You have been hired by one of the most reputable dental practices in the community. On the second day of employment, while treating your client, you accidentally insert a used hypodermic needle percutaneously into your thumb after administering a local anesthetic agent. Because your client is a high-profile state legislator and you do not want to appear incompetent to your new employer or the client, you say nothing about the exposure incident. After 3 days of thinking about the situation, you report the incident to the office manager. Use the principles of postexposure management to determine the following:

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge Barbara L. Heckman for her past contributions to this chapter.

Bolyard E.A., Tablan O.C., Williams W.W., et al. Guidelines for infection control in health care personnel, 1998. Am J Infect Control. 1998;26:289.

Carlton J.E., Dodson T.B., Cleveland J.L., Lockwood S.A. The risk of percutaneous injury in oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:553.

Cleveland J.L., Barker L.K., Cuny E.J., Panlilio A.L. National Surveillance System for Health Care Workers Group. Preventing percutaneous injuries among dental health care personnel. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:169.

Cleveland J.L., Barker L., Gooch B.F., et al. Use of HIV postexposure prophylaxis by dental health care personnel: an overview and updated recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:1619.

Cleveland J.L., Cardo D.M. Occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus: risk, prevention, and management. Dent Clin North Am. 2003;47:681.

Cleveland J.L., Cardo D.M. Occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus: risk, prevention, and management. Dent Clin North Am. 2004;47:681.

Cleveland J.L., Gooch B.F., Shearer B.G., Lyerla R.L. Risk and prevention of hepatitis C virus infection: implications for dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130:641-647.

Cleveland J.L., Griffin S.O., Romaguera R.A. Benefits of using rapid oral HIV-tests in dental offices. J Dent Res. 2005;84:3196. (Special Issue A)

Kohn W.G., Harte J.A., Malvitz D.M., et al. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings, 2003. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:33.

Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, et al: 2007 Guidelines for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings, June 2007. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/isolation2007.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2008.

Summers C: Practical infection control for dental sealant programs in a portable dental care environment. Presented at the National Public Health Dental Sealant Program Conference, Columbus, Ohio, August 26, 1994.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..