CHAPTER 10 Personal, Dental, and Health Histories

Systematically collect, analyze, investigate, and record information from a client’s personal, dental, and health histories.

Systematically collect, analyze, investigate, and record information from a client’s personal, dental, and health histories. Assess health status and determine risks, disease control level, and likelihood of a medical emergency via the health history interview.

Assess health status and determine risks, disease control level, and likelihood of a medical emergency via the health history interview. Manage client and practitioner risks, minimizing potential litigation via documentation in the client record.

Manage client and practitioner risks, minimizing potential litigation via documentation in the client record.PURPOSE OF THE HEALTH HISTORY

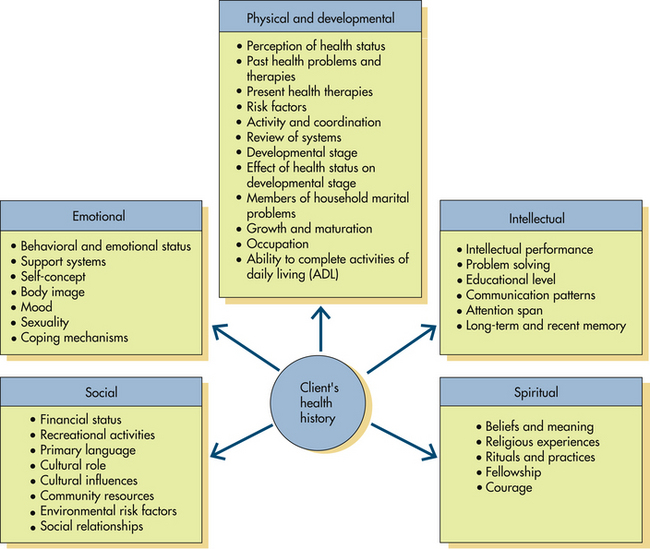

A complete health history identifies level of wellness (past and present) by collecting data about the client’s physical, intellectual, emotional, and social dimensions related to oral health and human needs (Figure 10-1). The health history provides the foundation for clinical decisions. Before dental hygiene procedures are implemented, medical information is used to determine the client’s health status, contraindications to care, and necessity for medical consultation. For example, nonsurgical periodontal therapy should not be implemented until the need for prophylactic antibiotic premedication is determined. In some situations dental hygiene care may complicate existing health conditions. Also, existing health conditions influence clinical outcomes, such as healing, predisposition to infection, or oral disease progression. Because a client’s health status is dynamic, the health history is monitored for changes at the beginning of each appointment to learn about changes in the client’s health since the last dental visit. If questioning reveals a treatment risk regarding the client’s health status that cannot be resolved, then a medical consultation may be necessary before care is initiated.

Health history assessment enables the dental hygienist to do the following:

Document baseline information about the client’s personal, social, dental, and medical health status, including vital sign values and qualities

Document baseline information about the client’s personal, social, dental, and medical health status, including vital sign values and qualities Assess overall physical and emotional health and nutritional status, including risk factors to be considered before the provision of dental hygiene care1

Assess overall physical and emotional health and nutritional status, including risk factors to be considered before the provision of dental hygiene care1 Identify risk factors that necessitate precautions to ensure safe oral care and prevent medical emergencies

Identify risk factors that necessitate precautions to ensure safe oral care and prevent medical emergencies

HEALTH HISTORY ASSESSMENT

Obtaining a complete health history includes direct observation of client features, completion of a written health history questionnaire, and implementation of an interview of the client based on the information provided.

Direct Observation

Assessment begins when the client enters the healthcare setting. Using direct observation, the dental hygienist mentally evaluates the following:

Could the client be under the effects of a medication? Alcohol? Illegal drug? Is the client sleepy, incoherent, distracted, depressed, moody, uninterested? Is speech slurred?

Could the client be under the effects of a medication? Alcohol? Illegal drug? Is the client sleepy, incoherent, distracted, depressed, moody, uninterested? Is speech slurred? Does the client seem emotionally stable? Is the client eager to talk and share, or disoriented, depressed, irritable, angry, anxious?

Does the client seem emotionally stable? Is the client eager to talk and share, or disoriented, depressed, irritable, angry, anxious?Written Health History Questionnaire

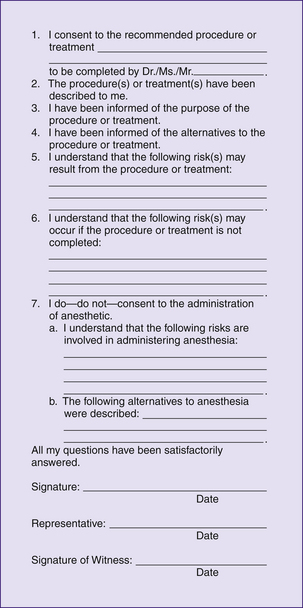

The client completes a health history questionnaire either in writing or electronically at each visit before receiving professional services. The questionnaire may be completed by the client in the reception area, or the clinician interviews the client in the privacy of the treatment area and marks the answers on the history form. Either strategy is acceptable. Most practitioners have the client complete the information and follow this with the interview to clarify and validate the information. Regardless of the approach used, the dental hygienist must, together with the client, review the responses, assess the significance of the responses, and determine their implications for professional care and referral to the dentist or physician of record. The health history questionnaire constitutes a legal document that provides past and present information about the client’s personal, social, dental, and health status. Therefore the health history form is completed in permanent ink (pencil or erasable ink is unacceptable). Recording errors should be neatly lined out, initialed, and dated. Accuracy of the health information is ascertained by having the client answer all items and sign and date the health history form. Written comments concerning the health history interview are initialed by the client to indicate accuracy. If the client is a minor (<18 years of age), a parent or legal guardian must sign and date the health history form to verify accuracy. A separate consent form (Figure 10-2) with an appropriate client (or parent or legal guardian) signature also could be used to verify permission for services to be rendered during the appointment

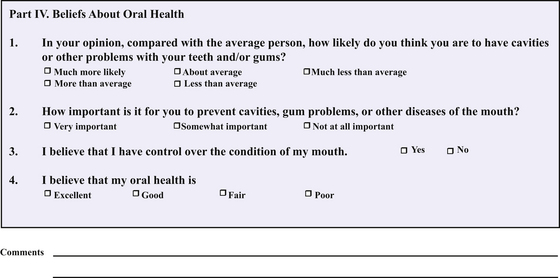

The client’s health history is confidential and is required by law to be protected from others unless the client’s permission is obtained. Office policies to ensure client privacy are required by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). HIPAA protects personal health information from being provided to others without the written approval of those involved, except in the case of an emergency situation. Although many formats for the written health history questionnaire are available, a current design of information includes an area at the top of the form to identify medical alert information. This section includes high-risk conditions, such as allergies, hypertension, or antibiotic prophylaxis orders, to be considered before oral care is initiated. Comprehensive health history formats contain the following information:

Personal and social history. Personal and social history information describes factual demographic and lifestyle information about the client: the client’s name, address, phone number (both home and business), date of birth, gender, marital status, occupation, cultural practices related to health and disease, referral source, types of insurance coverage, emergency contact information, and names of the dentist and physician of record with addresses and phone numbers. Such information is necessary for conducting the business aspects of the dental practice, establishing a familiarity with new clients, and facilitating high-quality care. Table 10-1 explains items included in a personal and social history and identifies implications for professional oral care.

Personal and social history. Personal and social history information describes factual demographic and lifestyle information about the client: the client’s name, address, phone number (both home and business), date of birth, gender, marital status, occupation, cultural practices related to health and disease, referral source, types of insurance coverage, emergency contact information, and names of the dentist and physician of record with addresses and phone numbers. Such information is necessary for conducting the business aspects of the dental practice, establishing a familiarity with new clients, and facilitating high-quality care. Table 10-1 explains items included in a personal and social history and identifies implications for professional oral care. Chief complaint. The chief complaint is the client’s primary reason for seeking the oral healthcare appointment and is recorded in the client’s own words. The client’s primary concern is addressed early in the care plan, no matter how minor, to facilitate client satisfaction, trust, and cooperation.

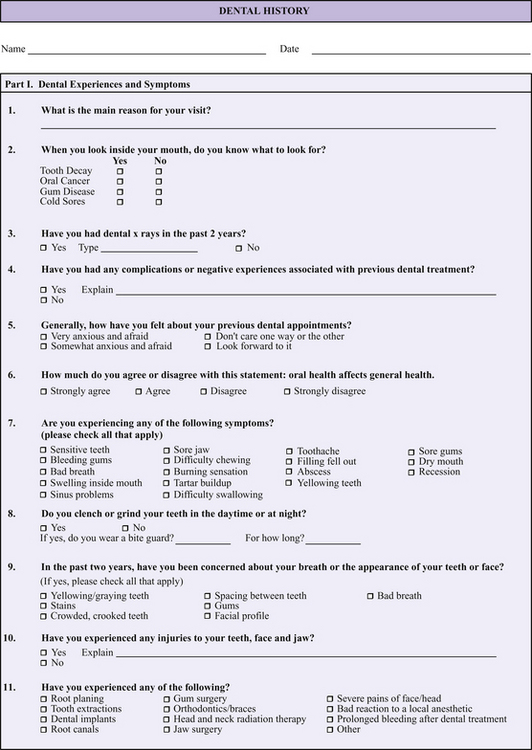

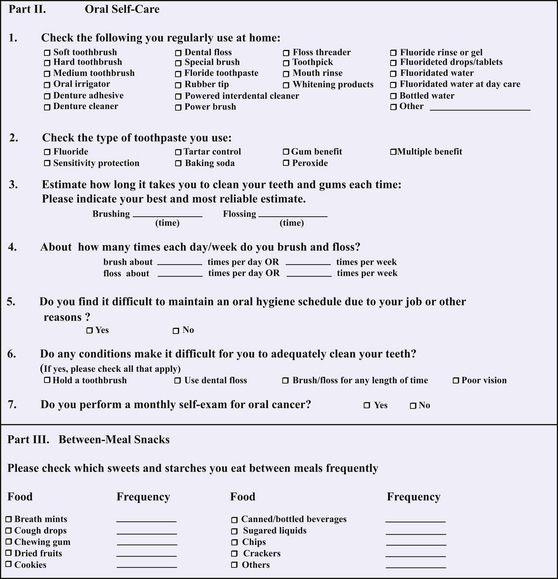

Chief complaint. The chief complaint is the client’s primary reason for seeking the oral healthcare appointment and is recorded in the client’s own words. The client’s primary concern is addressed early in the care plan, no matter how minor, to facilitate client satisfaction, trust, and cooperation. Dental history. Information collected about the client’s experiences with dentistry includes the following:

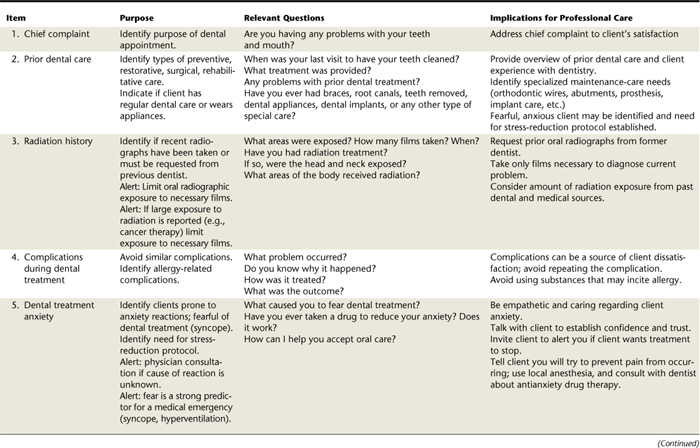

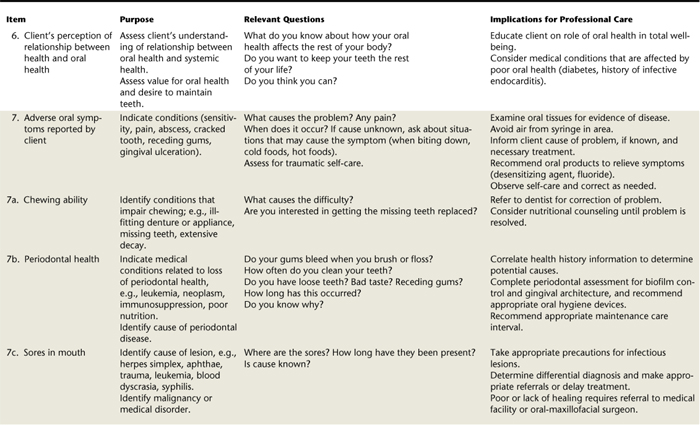

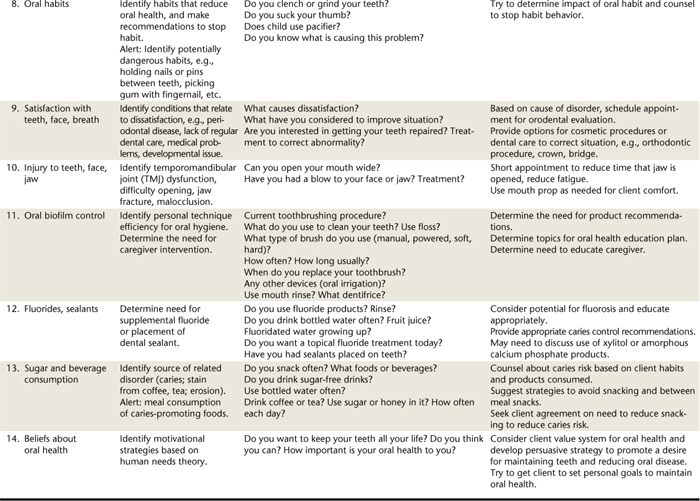

Dental history. Information collected about the client’s experiences with dentistry includes the following:

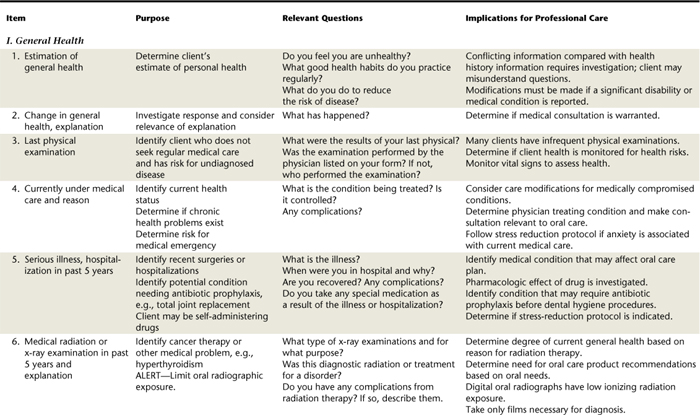

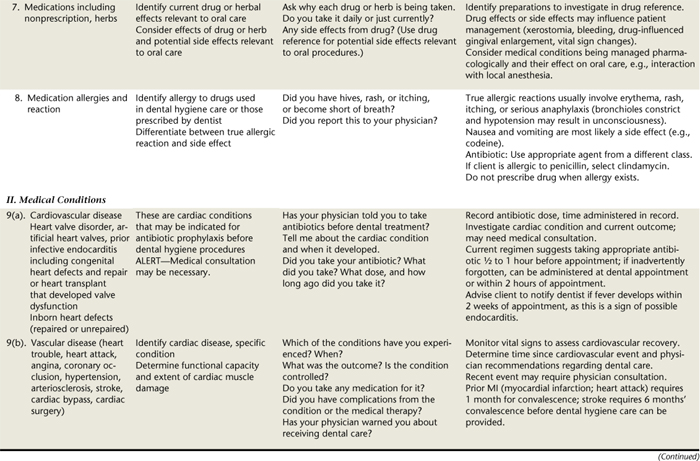

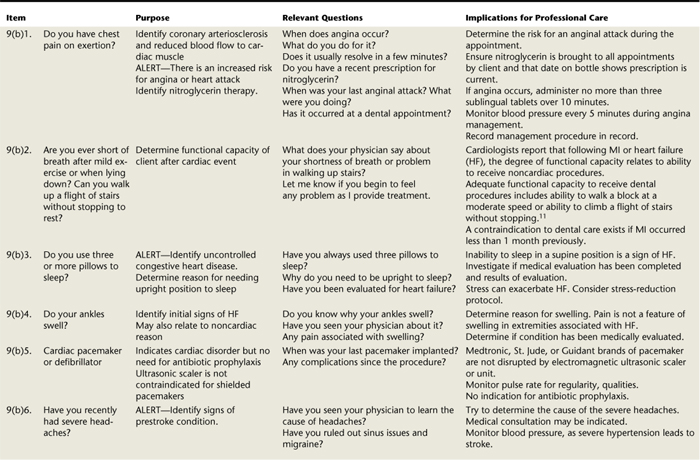

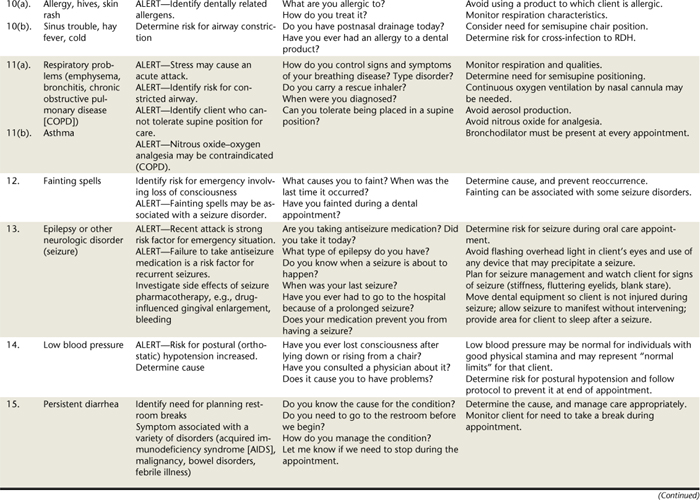

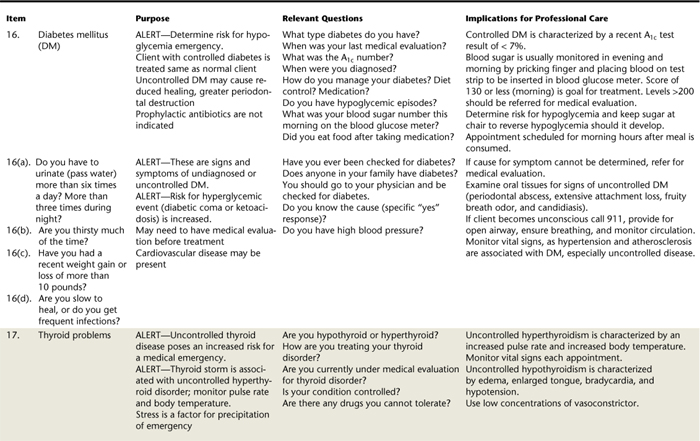

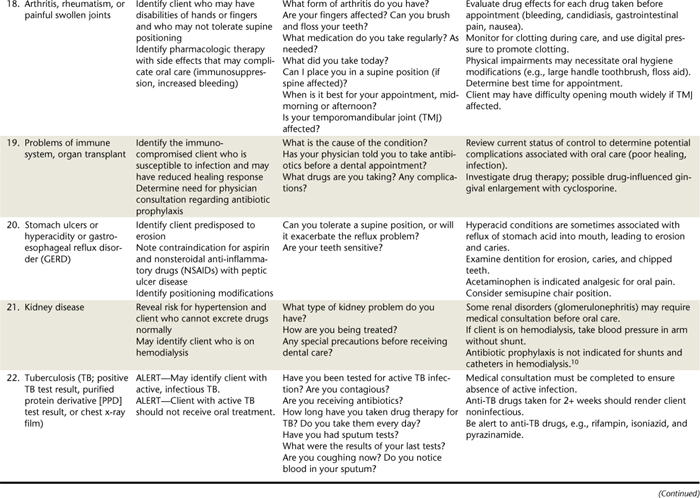

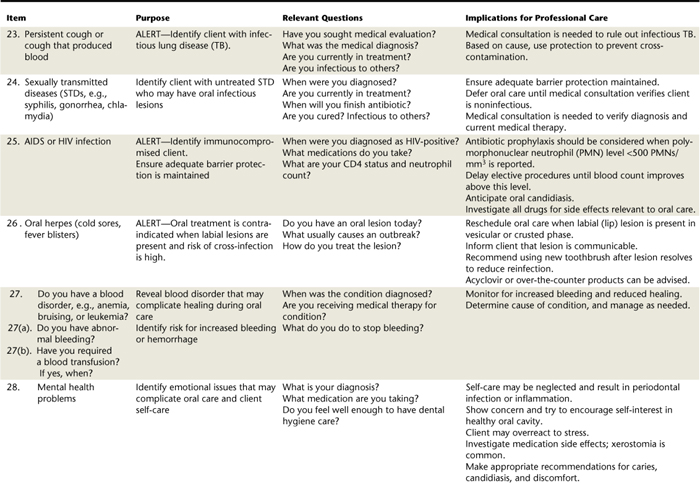

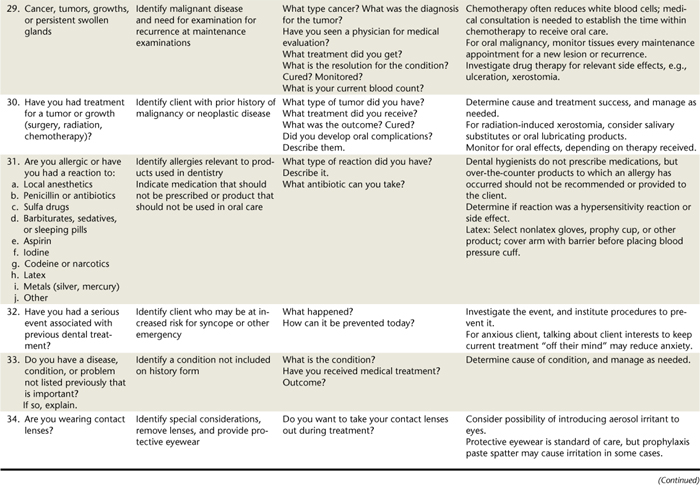

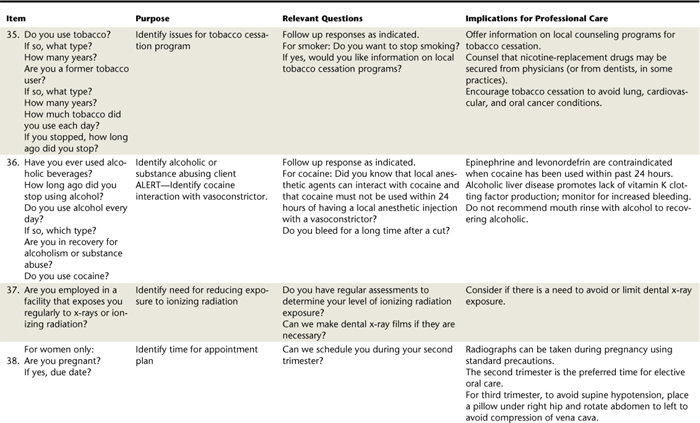

Health history. Health history information documents the client’s overall health, medications taken, risk factors for disease, allergies or unusual reactions, contraindications to care, signs suggestive for undiagnosed conditions, and the need for physician consultation. See Chapter 12 for the pharmacologic history. A comprehensive explanation of health history items is provided in Table 10-3.

Health history. Health history information documents the client’s overall health, medications taken, risk factors for disease, allergies or unusual reactions, contraindications to care, signs suggestive for undiagnosed conditions, and the need for physician consultation. See Chapter 12 for the pharmacologic history. A comprehensive explanation of health history items is provided in Table 10-3.TABLE 10-1 Personal History Items Explained

| Items | Rationale | Implications for Professional Care |

|---|---|---|

| Name, address (home, business, email) telephone and fax numbers, gender, marital status, date of form completion | ||

| Occupation or employment status of client, spouse; insurance information | ||

| Date of birth | ||

| Height, weight | ||

| Previous dentist, address, and phone number | ||

| Physician’s name and phone number | ||

| Referral source | Identify who should receive acknowledgment |

Health History Oral Interview

Although health history information is obtained initially using a structured written questionnaire, the dental hygienist uses the client’s responses as starting points for the health history interview. During the interview, events related to a response (such as a negative dental experience or fainting from an oral injection of a local anesthetic agent) or to the control of a systemic condition such as high blood pressure, hemophilia, or type 2 diabetes are discussed so that client health status is correctly assessed and safe care can be planned. Table 10-3 provides sample questions for the health history oral interview.

Interview Setting

A private setting (e.g., the treatment or consultation room) allows for security of personal client information. To ensure confidentiality and communicate respect, the health history interview should never be conducted in hearing range of others. The client is seated upright in the dental chair, and the dental hygienist is adjacent at eye level with the client. During the interview, the dental hygienist is alone with the client unless the client is a minor, in which case the parent or legal guardian is present. Clients respond more completely to a friendly, caring, nonjudgmental interviewer. Therefore the hygienist must demonstrate verbally and nonverbally acceptance of the client’s values.

Objectives of the Health History Interview

The objectives of the health history interview are as follows:

Form a positive dental hygienist–client relationship. The dental hygienist–client relationship is a partnership with a mutual concern—the client’s well-being. The health history interview is the first step toward establishing rapport and trust to promote evidence-based interventions that follow. If language is a barrier, determine if the client wants to have an interpreter.

Form a positive dental hygienist–client relationship. The dental hygienist–client relationship is a partnership with a mutual concern—the client’s well-being. The health history interview is the first step toward establishing rapport and trust to promote evidence-based interventions that follow. If language is a barrier, determine if the client wants to have an interpreter. Validate observations with data obtained by written and verbal communication. For example, if the client reports no fear of dental care but grasps the arms of the dental chair and appears anxious, the data conflict. This identifies the need to gather more information to resolve the apparent conflict of information, with the goal of preventing a likely medical emergency, vasovagal syncope (fainting).

Validate observations with data obtained by written and verbal communication. For example, if the client reports no fear of dental care but grasps the arms of the dental chair and appears anxious, the data conflict. This identifies the need to gather more information to resolve the apparent conflict of information, with the goal of preventing a likely medical emergency, vasovagal syncope (fainting).Three-Phase Interview Process

Orientation Phase

The dental hygienist opens the interview with introductions and becomes acquainted with the client. Inquiring about the reason for the appointment clarifies the client’s needs and identifies potential topics for education or community resources required to meet the client’s chief complaint and expectations. This is followed by an explanation of the need to gain additional information about the client’s health to assist in planning optimal care. Before asking clients to share personal information, the dental hygienist assures that all information will be held in strictest confidence. The rapport established allows the dental hygienist to gather valuable information of a personal nature.

Working Phase

The dental hygienist uses open-ended questions to clarify questionnaire responses and to obtain details of necessary information, rather than simply a “yes” or “no” response. For example, the dental hygienist may begin by saying, “Tell me about the chest pain you reported on the questionnaire—what causes it, and what do you do about it? Has it occurred during a dental appointment?” This technique leads to a discussion in which clients describe the issue in question. Using open-ended questions provides details to determine the risks of providing oral care and if a physician or dentist consultation is indicated. The use of eye contact and listening skills enhances communication. A listening technique called “back channeling” includes responses of “I see” or “uh-huh,” which indicates the dental hygienist has understood the client. In addition, the dental hygienist may use other communication strategies to facilitate communication (Box 10-1).

BOX 10-1 Strategies to Enhance Communication

Adapted from Potter PA, Perry AG: Fundamentals of nursing, ed 7, St Louis, 2009, Mosby.

Termination Phase

The client is given a clue that the interview is coming to an end. For example, the dental hygienist may say, “I believe I have all the information needed” or “I have just one more question.” Suggestions for managing client records are included in Box 10-2.

BOX 10-2 Suggestions for Managing Client Records

Adapted from Pollack BR: Dentist’s risk management guide, Fort Lauderdale, Fla, 1990, National Society of Dental Practitioners.

DECISION MAKING AFTER THE HEALTH HISTORY IS OBTAINED

Tools to Interpret Client Data and Degree of Medical Risk

American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Physical Status Classification System

A physical status classification system developed by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) rates the medical risk of a client who is to receive local or general anesthesia for a surgical procedure. This system, called the ASA classification system, considers client anxiety and classifies medical risk from I to V (ASA I-V) based on the disease or disorder (Box 10-3).3

BOX 10-3 American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System to Determine Medical Risk

Adapted from Malamed SF: Medical emergencies in the dental offi ce, ed 6, St Louis, 2007, Mosby; Stefanac SJ, Nesbit SP: Treatment planning in dentistry, ed 2, St Louis, 2007, Mosby; and Little JW, Falace DA, Miller CS, et al: Dental mangement of the medically compromised patient, ed 7, St Louis, 2008, Mosby.

Oral health professionals use the ASA classification system to determine whether treatment is safe for clients with various medical conditions. A client who falls within ASA IV status or greater should not receive elective treatment. Treatment can resume when the condition improves and the status is upgraded to the ASA III or ASA II status. For example, clients with a history of complications from uncontrolled diabetes should be referred for a medical evaluation (and possibly treatment to gain control of blood glucose levels) before dental hygiene care. If a client with an ASA IV status is in need of emergency oral care, then a hospital environment should be used in case a life-threatening emergency occurs. Only palliative care is recommended for a client with an ASA V status.

Stress, fear, and anxiety can lead to medical emergencies such as vasovagal syncope and hyperventilation and can exacerbate certain medical conditions, leading to an emergency situation. Stress reduction protocols should be part of the dental hygiene care plan as a strategy to avoid an emergency. Chapter 37 provides information on stress reduction protocols.

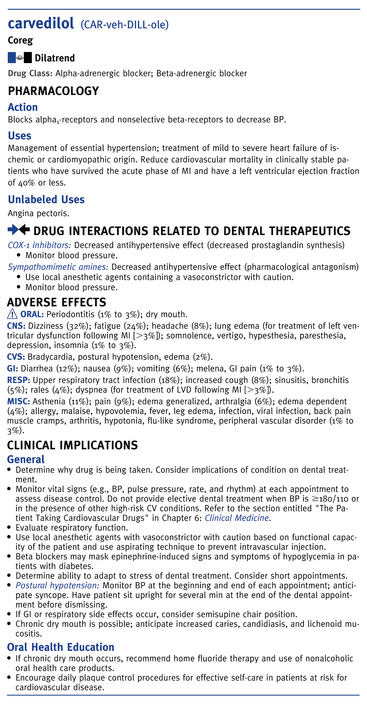

Use of Dental Drug References and Merck Manual

Before professional care is provided, the dental hygienist investigates and documents medications currently taken by the client (see Chapter 12). Medications taken by the client can alter treatment outcomes, contraindicate medications for dental and dental hygiene care, or indicate that a consultation with a physician should be completed before care is initiated. Several drug information sources published annually include the Physician’s Desk Reference (PDR), Facts and Comparisons, and GenRx. Drug information sources specific to oral healthcare are Mosby’s Dental Drug Reference, Drug Information Handbook for Dentistry, and LWW’s Dental Drug Reference with Clinical Implications.4-6 These focus on drug effects relevant to oral procedures, interactions between the object drug and drugs used in dentistry, clinical considerations related to drug effects, and the medical condition managed by the drug. These references cover topics that should be included in the oral health education plan, oral products of interest, a listing of medical conditions, and commonly prescribed drugs to manage those conditions. This information can be used when the client cannot recall a drug name but can identify it by looking at the drug names. Herbal information and the relationship to oral care often are included in these references. Although the PDR does not always include specific dental information, it has colored pictures of the dispensed forms of medication, so a visual identification can be made when the client cannot recall a medication name.7 Figure 10-4 illustrates drug information including the generic and brand names of a drug, the drug’s action, indication or approved use, interactions with drugs used in dentistry, adverse drug effects, clinical considerations, and oral health information.

Figure 10-4 Illustration of information in Dental Drug Reference with Clinical Implications.

(From Pickett FA, Terezhalmy GT: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins’ dental drug reference with clinical implications, ed 2, Baltimore, 2009, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.)

The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy is a standard reference book on diseases, including their causes, signs and symptoms, diagnostic indicators, and treatment.8 Dental hygienists confronted with unfamiliar medical conditions find readily available, concise descriptions of most diseases in this reference book. The reference book by Pickett and Gurenlian is helpful to investigate medical conditions and includes a description of the medical condition and appropriate follow-up questions to determine risks associated with providing dental hygiene care.1

Prophylactic Antibiotic Premedication9

There are two regimens for antibiotic premedication, also known as antibiotic prophylaxis. The regimen that is intended to prevent infective endocarditis is developed by the American Heart Association. The regimen that is intended to prevent infection in a total joint replacement (TJR) is developed by the American Dental Association in collaboration with the American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons. These infections are theorized to develop following the formation of bacteria within the circulation, a condition referred to as bacteremia. Manipulation of gingival tissues or the periapical region of teeth or perforation of the oral mucosa during dental or dental hygiene procedures may cause a transient bacteremia; it is recommended that clients undergoing these procedures and who have high-risk for complications if endocarditis develops receive antibiotic prophylaxis (Table 10-4). Bacteremia is the introduction of microorganisms into the circulation, which is normally free of microorganisms. Although the host immune response generally removes the bacteremia within 15 minutes, infectious microorganisms in the bloodstream may cause distant site infections in individuals with selected conditions, such as cardiac valve replacement or TJR. Specifically, microbes may become lodged on damaged or abnormal areas of the heart valves, lining of the heart, and underlying connective tissue and cause infective endocarditis (a life-threatening infection of the tissue lining the heart and also the underlying connective tissue, sometimes referred to as bacterial endocarditis).9 A small number of clients with prosthetic TJRs are susceptible to an infection of the area of the prosthetic replacement, which can lead to subsequent removal of the joint prosthesis (see Table 10-4).2

TABLE 10-4 Antibiotic Premedication Guidelines for Professional Oral Healthcare

| Conditions | Prophylaxis Recommended | Prophylaxis Not Recommended |

|---|---|---|

| Dental procedures | Manipulation of gingival tissues or the periapical region of teeth or perforation of the oral mucosa during oral procedures. | |

| Cardiac conditions | ||

| Orthopedic conditions | Not routinely indicated for most clients with joint replacements or with plates, pins, or screws or for TJR after 2 years | |

| Other conditions | There are no official recommendations to guide the oral professional. |

Adapted from American Dental Association, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: Advisory statement: antibiotic prophylaxis for dental patients with total hip joint replacements, J Am Dent Assoc 134:895, 2003; Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al: 2007 American Heart Association Guidelines, J Am Dent Assoc 138:739, 2007.

Prophylactic antibiotic premedication is the administration of specific antibiotics ½ to 1 hour before the dental procedure that could cause bacteremia, in individuals whose medical condition (certain cardiac conditions or some prosthetic joint replacements) places them at a high risk for infection or if serious morbidity or mortality could result if infection developed. The goal of taking the antibiotic for cardiac conditions listed in Box 10-4 is to prevent infective endocarditis, although the American Heart Association (AHA) states that there is no scientific proof that antibiotics used in this manner would prevent infective endocarditis.9 Before initiating dental hygiene procedures, the dental hygienist questions the client indicated for antibiotic prophylaxis to determine if the prescribed antibiotic was taken, if the correct dose was taken, and when the antibiotic was taken. This information is recorded in the client record (see Table 10-4 and Box 10-5). For the client at high risk for infective endocarditis, the current AHA recommendation advises that when the antibiotic was not consumed (client forgot to take the antibiotic), the recommended dose can be administered within 2 hours of the dental appointment.9 The administration of an antibiotic is associated with the development of antibiotic-resistant microorganisms. For this reason, individuals who are currently taking an antibiotic in the regimen should receive an antibiotic from a different class. For example, in a client with a history of infective endocarditis who usually would take amoxicillin for antibiotic prophylaxis but who is taking amoxicillin presently for another medical reason, either clindamycin or one of the macrolides (e.g., azithro-mycin, clarithromycin) can be used. It is also suggested to delay the dental procedure until at least 10 days after completion of the antibiotic therapy. This may allow time for the usual oral flora to reestablish.

BOX 10-4 Cardiac Conditions∗ Associated with Highest Risk of Adverse Outcome from Endocarditis for Which Prophylaxis with Dental Procedures Is Recommended

From Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M Prevention of infective endocarditis, J Am Dent Assoc 139 Suppl:3S, 2008.

The client’s periodontal health status may promote development of bacteremias. For this reason the AHA recommends that oral health should be maintained, as this may be the most effective strategy to prevent infective endocarditis. Transient bacteremias can occur from day-to-day activities such as chewing, toothbrushing, flossing, and use of other oral devices. Oral devices used inappropriately or in clients with periodontal inflammation have produced bacteremias. Whether the bacteremia plays a role in the loss of overall health is unknown; however, a healthy oral environment is thought to reduce the risk. Although good oral hygiene habits should be encouraged for all individuals, they are especially important for persons with conditions such as cardiovascular disease or recent joint replacements and possibly some clients with immunosuppression, as these medical conditions are associated with increased risk for more serious health complications.

Infective Endocarditis

For all dental procedures that involve manipulation of gingival tissue or the periapical region of teeth or perforation of the oral mucosa, it is recommended that individuals identified in Box 10-4 receive antibiotic prophylaxis before the appointment. This would include most dental hygiene care procedures.

Individuals who took fenfluramine/phentermine (fen-phen) for weight reduction might have developed a cardiac valve disorder. It was thought that these individuals with a cardiac valve anomaly verified via echocardiogram should receive antibiotic prophylaxis before certain oral procedures. With the 2007 AHA guidelines’ elimination of cardiac conditions formerly recommended for prophylaxis, except for those at the highest risk for mortality or morbidity or mortality, these individuals are no longer required to have antibiotic prophylaxis before oral procedures. The 2007 AHA guidelines identify oral procedures that do not necessitate antibiotic prophylaxis: routine anesthetic injections through noninfected tissue, taking dental radiographs, placement of removable prosthodontic or orthodontic appliances, adjustment of orthodontic appliances, placement of orthodontic brackets, shedding of primary teeth or bleeding from trauma to the lips or oral mucosa.

Use of antibiotic prophylaxis has changed dramatically since the publication of the 2007 AHA guidelines. This is partly a result of the adverse effects of antibiotic misuse and overuse, risk of allergic reactions, and increase in antibiotic-resistant microorganisms worldwide. Increasing percentages of microorganisms are found to be resistant to agents used for prophylaxis. The past practice of “when in doubt, premedicate” is no longer warranted.

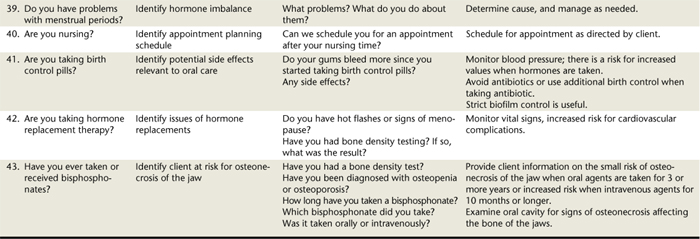

Antibiotic Premedication Dosage Regimen Guidelines

The standard prophylactic regimen recommended by the AHA is shown in Table 10-5.9 One dose of the appropriate antibiotic ½ to 1 hour before the procedure is recommended (see Table 10-5). Some facilities keep antibiotics available to assure that oral procedures can be provided with no delay when indicated. The 2007 guidelines, however, provide for taking the antibiotic within 2 hours of the appointment when the dose is inadvertently not taken by the client. Cardiac conditions recommended for prophylaxis are in Box 10-4. See Table 10-6, which summarizes dental management considerations for all indications for antibiotic prophylaxis.

TABLE 10-6 Dental Management Considerations When Using Prophylactic Antibiotics

| Management of at-risk individuals | Management rationale |

|---|---|

| This may prevent infective endocarditis. | |

| This may prevent infective endocarditis.Educate the client. | |

| This reduces emergence of resistant microorganisms and allows repopulation of the usual antibiotic-susceptible flora. | |

| This reduces emergence of resistant microorganisms. | |

| This reduces the number of times a client is premedicated, which lowers cost and decreases the likelihood of resistant microorganisms emerging. | |

| Ill-fitting removable oral prostheses can cause tissue ulceration with concomitant bacteremia of oral origin. | |

| This may provide effective prophylaxis. There is no prophylactic benefit if one administers antibiotic 3 or more hours after an indicated procedure. |

Adapted from Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group, J Am Dent Assoc 138:739, 2007.

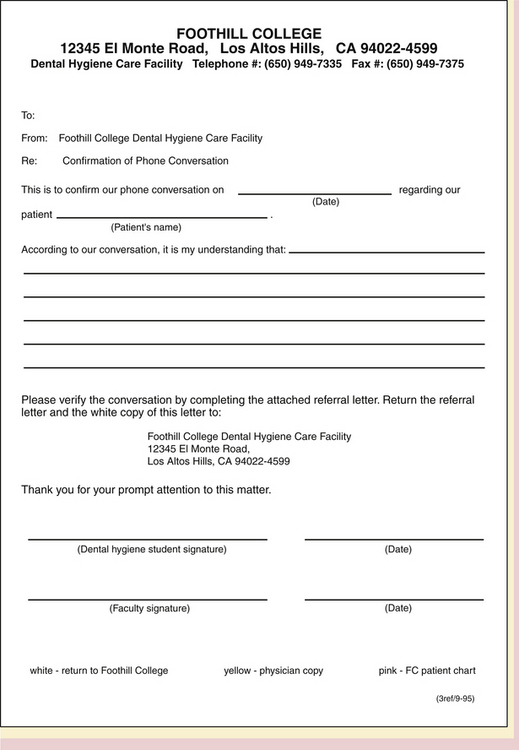

Total Joint Replacement

Antibiotic premedication is not routinely recommended for all clients with a TJR, nor is it indicated for persons with surgically implanted pins, plates, or screws.2 Because some dental procedures are more invasive than others, the type of procedure being performed and client risk for hematogenous total joint infection must be evaluated to determine whether the client is a candidate for prophylactic antibiotic premedication (see Table 10-4). For example, a client scheduled for scaling and root planing who has had a TJR within the last 2 years will need antibiotic premedication. A client scheduled for scaling and root planing who had a joint replaced over 2 years ago with no complications will not need antibiotic premedication. If there is uncertainty concerning the client’s risk, the recommendation of the client’s orthopedic physician is generally followed. Current recommendations for individuals with a TJR are listed in Table 10-7. The prophylactic regimen for prophylaxis for TJR is different than for prevention of endocarditis.

TABLE 10-7 Recommended Antibiotic Prophylaxis Regimens with Total Joint Replacements∗

| Situation | Agent | Regimen |

|---|---|---|

| Patients not allergic to penicillin | Cephalexin, cephradine, or amoxicillin (oral) | 2 g orally 1 hour before the dental procedure |

| Patients not allergic to penicillin and unable to take oral medications | Cefazolin or ampicillin (intramuscularly or intravenously) | Cefazolin 1 g or ampicillin 2 g intramuscularly or intravenously 1 hour before the procedure |

| Patients allergic to penicillin | Clindamycin (oral) | 600 mg orally 1 hour before the dental procedure |

| Patients allergic to penicillin and unable to take oral medications | Clindamycin (intravenously) | 600 mg intravenously 1 hour before the procedure |

∗ No second doses are recommended for any of these dosing regimens.

Adapted from the American Dental Association, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: Antibiotic prophylaxis for dental patients with total joint replacements, J Am Dent Assoc 134:895, 2003.

Other Medical Conditions

Antibiotic prophylaxis is determined by the client’s physician and may include persons undergoing anticancer chemotherapy, including treatment for acute leukemia; renal transplantation or kidney dialysis; or persons taking immunosuppressive medications. For immunosuppressed clients, the client’s physician should be consulted about the need for antibiotic premedication before dental procedures. A review of the literature found a lack of evidence to support the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in eight medical conditions: cardiac pacemakers, prosthetic joint replacements, renal dialysis shunts, cerebrospinal fluid shunts, vascular grafts, immune suppression secondary to cancer and cancer chemotherapy, systemic lupus erythematosus, and type 1 diabetes mellitus.10 Of the eight conditions, Lockhart et al.10 found official recommendations in favor of antibiotic prophylaxis for only selected situations involving prosthetic joint replacement and cardiac conditions. They found no prospective randomized clinical trials and only one clinical study of antibiotic prophylaxis in these conditions. One systematic review and two case series provided weak support for antibiotic prophylaxis in clients with cardiac conditions.11 Little to no evidence supports that antibiotic prophylaxis prevents distant site infections for any of the eight conditions. No scientific basis exists for the use of prophylactic antibiotics before dental procedures in persons with six of these eight conditions.

Physician Consultation

The physician of record is consulted if the client reveals a condition that may jeopardize safety during care. Medical consultations are initiated for the following:

Precautionary treatment modifications, e.g., local anesthetics with reduced levels of vasoconstrictor (see Chapter 39)

Precautionary treatment modifications, e.g., local anesthetics with reduced levels of vasoconstrictor (see Chapter 39)Telephone Contact

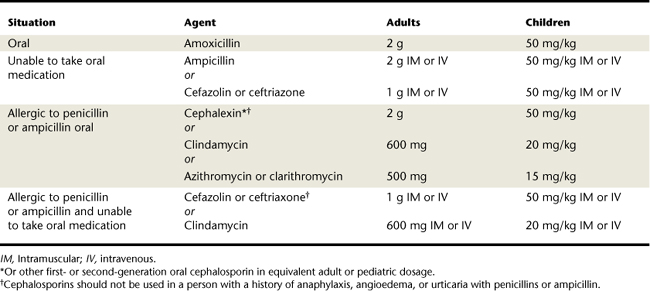

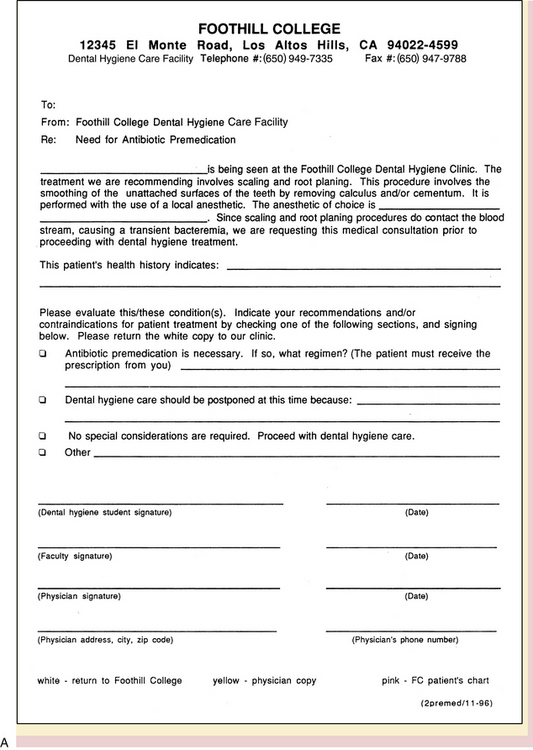

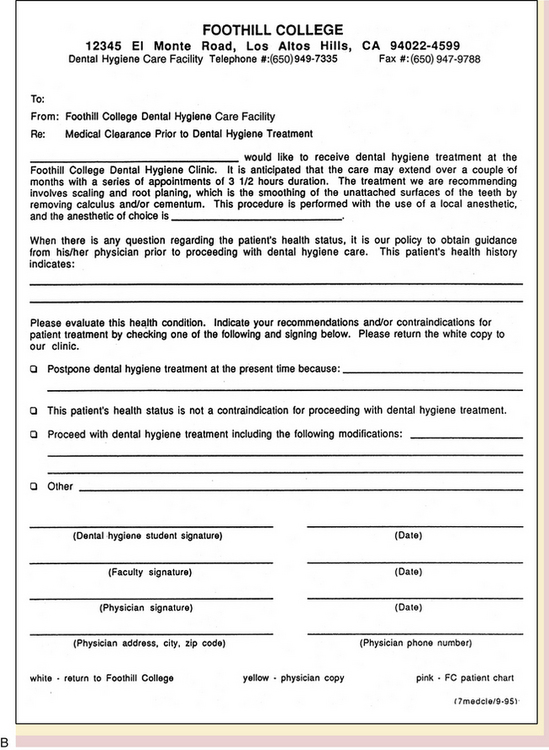

Immediate telephone consultation with the physician of record and referral are indicated if the client reveals a condition that precludes dental hygiene care or needs urgent dental or medical attention. Telephone consultations should be documented in the client’s dental record and followed up with a written consultation form (Figure 10-5). To expedite the receipt of information, a request for the physician to fax information is acceptable.

Written Request

When information is obtained in writing from the client’s physician, the request should be duplicated and a copy placed in the client’s dental record. An entry in the treatment record should document to whom the medical request was sent and the reason for the request. Sample medical consultation forms are shown in Figure 10-6. A formal written request for medical consultation is the preferred procedure for medicolegal reasons. When the request is returned from the physician, it is kept in the client’s treatment record.

Referral

Clients are referred for medical evaluation when an undiagnosed condition is suspected (e.g., presence of signs and symptoms of diabetes mellitus) or when needed laboratory test results are not available (e.g., blood test to determine risk for excessive bleeding when warfarin is taken).

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Counsel clients predisposed to an emergency situation in the dental setting by using the information in the clients’ health history. For example, a client with diabetes mellitus should be counseled to eat after taking his or her indicated dose of insulin (or sulfonylurea) the day of an appointment.

Counsel clients predisposed to an emergency situation in the dental setting by using the information in the clients’ health history. For example, a client with diabetes mellitus should be counseled to eat after taking his or her indicated dose of insulin (or sulfonylurea) the day of an appointment. When a medical consultation is indicated, educate the client about the concerns of the condition and the risks of proceeding with oral care without proper medical advice.

When a medical consultation is indicated, educate the client about the concerns of the condition and the risks of proceeding with oral care without proper medical advice. Educate clients about the rationale for prophylactic antibiotic premedication before dental hygiene procedures involving gingival or apical manipulation when indicated.

Educate clients about the rationale for prophylactic antibiotic premedication before dental hygiene procedures involving gingival or apical manipulation when indicated. Educate clients about the importance of regular oral examination to reduce the severity of oral disease and decrease costs associated with oral care.

Educate clients about the importance of regular oral examination to reduce the severity of oral disease and decrease costs associated with oral care.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Before making a legal or ethical decision, the dental hygienist seeks resources that guide the process, e.g., American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) or Canadian Dental Hygienists Association (CDHA) code of ethics, rules and regulations governing the practice of dental hygiene in the legal jurisdiction, and public health statutes. Public health statutes may identify responsibilities such as manditory reporting of abuse and domestic violence, infectious disease reporting, and record keeping.

Before making a legal or ethical decision, the dental hygienist seeks resources that guide the process, e.g., American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) or Canadian Dental Hygienists Association (CDHA) code of ethics, rules and regulations governing the practice of dental hygiene in the legal jurisdiction, and public health statutes. Public health statutes may identify responsibilities such as manditory reporting of abuse and domestic violence, infectious disease reporting, and record keeping. Written office protocols that reflect evidence-based practices protect the healthcare team from litigation if the protocols are used and practiced.

Written office protocols that reflect evidence-based practices protect the healthcare team from litigation if the protocols are used and practiced. The history form is completed by the client. Information can be added by the client and the dental hygienist while jointly reviewing the health history information. Emergency phone numbers and physician phone numbers should always be present on the form in the event that a medical emergency occurs, so that appropriate personnel can be notified.

The history form is completed by the client. Information can be added by the client and the dental hygienist while jointly reviewing the health history information. Emergency phone numbers and physician phone numbers should always be present on the form in the event that a medical emergency occurs, so that appropriate personnel can be notified. A medical alert box, a space at the top of the health history form, can be used to alert the practitioner to medical conditions that require dental hygiene care modifications and to prevent health risks. Conditions should be written in the box in red.

A medical alert box, a space at the top of the health history form, can be used to alert the practitioner to medical conditions that require dental hygiene care modifications and to prevent health risks. Conditions should be written in the box in red. Errors are carefully lined out with one line, dated, and initialed. Explanations may be necessary to avoid confusion. For example, if at a later date the client remembers an allergy to penicillin, the correction should be made at the appropriate location on the form and an explanation added, such as “client remembers an allergy to penicillin” (date and initial).

Errors are carefully lined out with one line, dated, and initialed. Explanations may be necessary to avoid confusion. For example, if at a later date the client remembers an allergy to penicillin, the correction should be made at the appropriate location on the form and an explanation added, such as “client remembers an allergy to penicillin” (date and initial). Document relevant information learned during questioning on the health history form; review written comments with the client; client should sign or initial.

Document relevant information learned during questioning on the health history form; review written comments with the client; client should sign or initial. The health history form contains confidential information to be shared only with those involved directly with the client’s treatment. Follow state and local regulations concerning protection of medical history information.

The health history form contains confidential information to be shared only with those involved directly with the client’s treatment. Follow state and local regulations concerning protection of medical history information. Medical consultation or referrals should outline the medical issue requiring consultation or referral. One copy of the form is sent, faxed, or given to the client to take to the physician. One copy of the form is kept in the client’s chart to document the request for consultation or referral. When necessary, telephone consultations should be documented in the client’s chart and followed with a faxed verification from the physician, including details of the conversation and the name of the person providing information at the physician’s office.

Medical consultation or referrals should outline the medical issue requiring consultation or referral. One copy of the form is sent, faxed, or given to the client to take to the physician. One copy of the form is kept in the client’s chart to document the request for consultation or referral. When necessary, telephone consultations should be documented in the client’s chart and followed with a faxed verification from the physician, including details of the conversation and the name of the person providing information at the physician’s office. Signing the health history form indicates accuracy of information provided by the client. Client approval for treatment is indicated by a signed informed consent form which should always be used.

Signing the health history form indicates accuracy of information provided by the client. Client approval for treatment is indicated by a signed informed consent form which should always be used.KEY CONCEPTS

The personal, dental, and health history form is a legal document that contains information about the client’s state of health.

The personal, dental, and health history form is a legal document that contains information about the client’s state of health. The dental hygienist–client relationship is a partnership based on trust and has the client’s well-being as a mutual focus.

The dental hygienist–client relationship is a partnership based on trust and has the client’s well-being as a mutual focus. The client completes the written health history questionnaire at the first visit. The dental hygienist reviews, discusses, and verifies the information on the health history questionnaire via an oral interview. At subsequent appointments the health history is updated; changes are investigated and documented in writing.

The client completes the written health history questionnaire at the first visit. The dental hygienist reviews, discusses, and verifies the information on the health history questionnaire via an oral interview. At subsequent appointments the health history is updated; changes are investigated and documented in writing. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System can be used to identify the medical risk of the client and reduce the probability that medical emergencies will occur. Only clients in the ASA I to III classifications should receive elective oral care.

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System can be used to identify the medical risk of the client and reduce the probability that medical emergencies will occur. Only clients in the ASA I to III classifications should receive elective oral care. Stress reduction protocols minimize risk of a medical emergency and create a satisfactory experience for the anxious client.

Stress reduction protocols minimize risk of a medical emergency and create a satisfactory experience for the anxious client. A dental drug reference is a key reference for identifying and determining drug actions, interactions, contraindications, potential adverse reactions, precautions, clinical considerations, and oral health education topics. The Merck Manual is a useful reference for information concerning diseases or medical conditions.

A dental drug reference is a key reference for identifying and determining drug actions, interactions, contraindications, potential adverse reactions, precautions, clinical considerations, and oral health education topics. The Merck Manual is a useful reference for information concerning diseases or medical conditions. Infective endocarditis (IE) can be a life-threatening condition. Dental procedures including gingival manipulation or perforation of oral mucosa may be a risk factor for IE. Clients at the highest risk for complications from IE should receive prophylactic antibiotic premedication before dental hygiene procedures.

Infective endocarditis (IE) can be a life-threatening condition. Dental procedures including gingival manipulation or perforation of oral mucosa may be a risk factor for IE. Clients at the highest risk for complications from IE should receive prophylactic antibiotic premedication before dental hygiene procedures. Clients with total joint replacements are susceptible to infections following certain dental procedures. Clients susceptible to joint infection should receive medical evaluation by the orthopedist to determine the need for prophylactic antibiotic premedication.

Clients with total joint replacements are susceptible to infections following certain dental procedures. Clients susceptible to joint infection should receive medical evaluation by the orthopedist to determine the need for prophylactic antibiotic premedication. Immunosuppressed individuals may be susceptible to infections from certain dental procedures. Clients susceptible to life-threatening infections are carefully evaluated and referred to their physicians to determine need for prophylactic antibiotic premedication.

Immunosuppressed individuals may be susceptible to infections from certain dental procedures. Clients susceptible to life-threatening infections are carefully evaluated and referred to their physicians to determine need for prophylactic antibiotic premedication.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

Client Profile: Mr. Smith is a 35-year-old male client who currently is not married and is self-employed as a contractor and home builder.

Chief Complaint: “To get my teeth taken care of.”

Dental History: Mr. Smith has avoided dentists for over 10 years until he developed severe oral pain. A local endodontist referred him to the general dentist. The referral letter noted that Mr. Smith has an apical abscess associated with decayed tooth No. 30. The endodontist noted that Mr. Smith placed aspirin directly on the gingival tissues near No. 30, resulting in a chemical burn on the adjacent mucosa and gingiva. Mr. Smith needs extensive restorative and nonsurgical periodontal care. Unfortunately, Mr. Smith has rescheduled his first appointment with the general dentist three times. The appointment scheduled for a periodontal assessment with the dental hygienist was also rescheduled several times by Mr. Smith, delaying treatment for months.

Health History: Mr. Smith has a history of asthma, hypertension and diabetes. His asthma is managed with a bronchodilator (albuterol); type 1 diabetes is controlled by daily insulin and diet. His last asthma attack occurred recently at the endodontist’s office and was managed with his bronchodilator. Mr. Smith reports his diabetes as controlled, although he can’t recall his A1c test values, and says that he is seeing a physician on a regular basis for the diabetes and the asthma. He brought his bronchodilator (albuterol) to the appointment; it is in his pocket. He is also taking medication (Procardia) to control high blood pressure, and he took it last evening. All vital signs recorded at the first office visit were within normal limits (WNL), and today’s readings are also WNL. He marks negatively the question concerning unpleasant experiences in a dental office or nervousness about treatment.

Extraoral Examination: All within normal limits.

Supplemental Notes: Client arrived late for the 4:30 pm appointment. At 5:15 pm the dental hygienist escorted him to the treatment room to review the health and dental history. The hygienist noticed that Mr. Smith was anxious with perspiration beads on his upper lip, trembling hands; he was grasping the arms of the dental chair. The health history was reviewed, vital signs were measured, and no health history changes have occurred other than the recent asthma attack.

1. Pickett F., Gurenlian J. The medical history: clinical implications and emergency prevention in dental settings, ed 2. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009.

2. American Dental Association. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: Advisory statement: antibiotic prophylaxis for dental patients with total joint replacements. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:895.

3. Wilson W., Taubert K.A., Gewitz M., et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis. Guidelines from the American Heart Association. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:739.

4. Malamed S.F. Medical emergencies in the dental office, ed 6. St Louis: Mosby; 2007.

5. Pickett F.A., Terezhalmy G.T. Dental drug reference with clinical implications, ed 2. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007.

6. Wynn R.L., Meiller T.F., Crossley H.L. Drug information handbook for dentistry, ed 13. Hudson, Ohio: LexiComp; 2007.

7. Mosby’s dental drug reference, ed 8. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

8. Physicians’ desk reference, ed 63. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics; 2009.

9. Beers M.H., Porter R.S., Jones T.V. The Merck manual of diagnosis and therapy, ed 18, Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck, 2006.

10. Lockhart P.B., Loven B., Brennan M.T., Fox P.C. The evidence base for the efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:458.

11. Eagle K.A., Berger B.P., Calkins H., et al. ACC/AHA guideline update for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:542.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..